Second Genome: Rhizosphere Microbiome as a Key External Driver of Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Maize

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Transporter-Mediated Mechanisms of Efficient Nitrogen Uptake and Translocation in Maize

2.1. Molecular Regulation of Nitrate (NO3−) Transporters and Nitrogen Assimilation

2.2. Ammonium (NH4+) Uptake and Regulatory Mechanisms in Maize

3. The Rhizosphere Microbiome in Plant Growth and Developmental Regulation

4. Rhizosphere Microbiome-Mediated Promotion of Nitrogen Uptake in Maize

5. Multi-Omics Dissection of Rhizosphere Microbiome–Nitrogen Interactions

6. Microbiome-Based Intervention Strategies to Enhance Nitrogen Acquisition

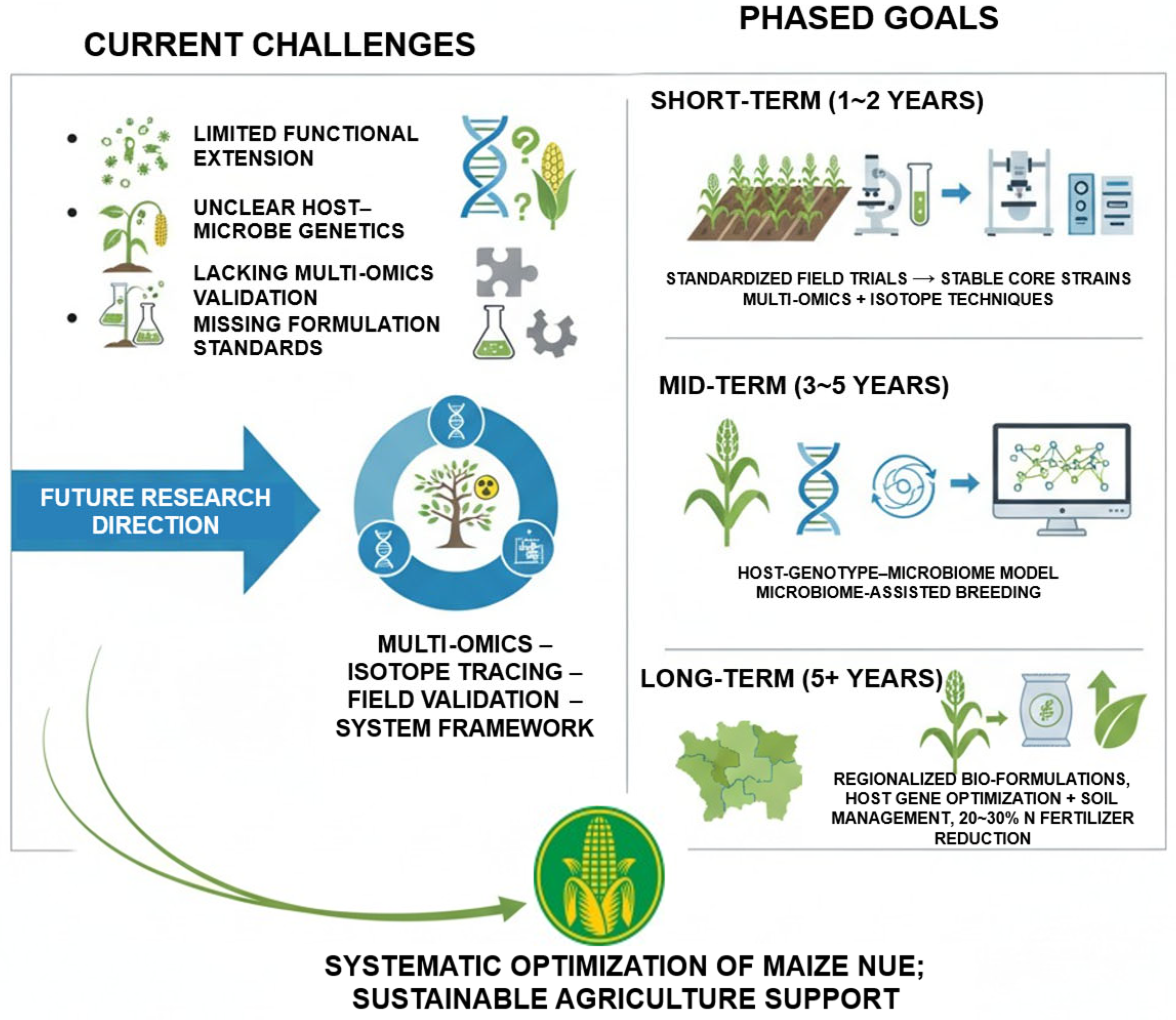

7. Future Directions for Rhizosphere Microbiome-Mediated Regulation of NUE

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cui, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, C.; Ma, W.; Huang, C.; Zhang, W.; Mi, G.; Miao, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Pursuing sustainable productivity with millions of smallholder farmers. Nature 2018, 555, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chu, Y.; Xue, Y.; Ying, H.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, W.; Ma, L.; Zhang, J.; Yin, Y.; et al. Outlook of China’s agriculture transforming from smallholder operation to sustainable production. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 26, 100444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, G.P.; Vitousek, P.M. Nitrogen in agriculture: Balancing the cost of an essential resource. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2009, 34, 97–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Fan, X.; Miller, A.J. Plant nitrogen assimilation and use efficiency. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2012, 63, 153–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheoran, S.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, P.; Meena, R.S.; Rakshit, S. Nitrogen fixation in maize: Breeding opportunities. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 1263–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.; Okamoto, M.; Beatty, P.; Rothstein, S. The genetics of nitrogen use efficiency in crop plants. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2015, 49, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Qi, S.; Wang, Y. Nitrate signaling and use efficiency in crops. Plant Commun. 2022, 3, 100353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.H.; Liu, M.; Lin, Z.; Wang, Z.F.; Chen, B.; Liu, C.; Guo, A.; Konishi, M.; Yanagisawa, S.; Wagner, G.; et al. NIN-like protein 7 transcription factor is a plant nitrate sensor. Science 2022, 377, 1419–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Wang, W.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Chu, C. Genetic improvement toward nitrogen-use efficiency in rice: Lessons and perspectives. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, M.; Huang, S.; Li, L.; Gao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Huang, S.; Yuan, L.; Wen, Y.; et al. A highly conserved core bacterial microbiota with nitrogen-fixation capacity inhabits the xylem sap in maize plants. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, M.A.; Xu, G.; Lopez-Guerrero, M.G.; Li, G.; Smith, C.; Sigmon, B.; Herr, J.R.; Alfano, J.R.; Ge, Y.; Schnable, J.C.; et al. Association analyses of host genetics, root-colonizing microbes, and plant phenotypes under different nitrogen conditions in maize. eLife 2022, 11, e75790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuypers, M.; Marchant, H.; Kartal, B. The microbial nitrogen-cycling network. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Xu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Ning, L.; Shabala, S.; Zhao, H. Transcription factor ZmEREB97 regulates nitrate uptake in maize roots. Plant Physiol. 2024, 196, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Hou, Y.; Yan, J.; Cheng, S.; Wang, Y.; Feng, G.; Cai, H. Comprehensive responses of root system architecture and anatomy to nitrogen stress in maize genotypes with contrasting nitrogen efficiency. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liseron-Monfils, C.; Bi, Y.M.; Downs, G.S.; Wu, W.; Signorelli, T.; Lu, G.; Chen, X.; Bondo, E.; Zhu, T.; Lukens, L.N.; et al. Nitrogen transporter and assimilation genes exhibit developmental stage-selective expression in maize associated with distinct cis-acting promoter motifs. Plant Signal. Behav. 2013, 8, e26056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganugi, P.; Fiorini, A.; Ardenti, F.; Caffi, T.; Bonini, P.; Taskin, E.; Puglisi, E.; Tabaglio, V.; Trevisan, M.; Lucini, L. Nitrogen use efficiency, rhizosphere bacterial community, and root metabolome reprogramming due to maize seed treatment with microbial biostimulants. Physiol. Plant. 2022, 174, e13679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloch, S.E.; Clark, R.; Gottlieb, S.S.; Wood, L.K.; Shah, N.; Mak, S.M.; Lorigan, J.G.; Johnson, J.; Davis-Richardson, A.G.; Williams, L.; et al. Biological nitrogen fixation in maize: Optimizing nitrogenase expression in a root-associated diazotroph. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 4591–4603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bo, H.; Li, Z.; Jin, D.; Xu, M.; Zhang, Q. Fertilizer management methods affect bacterial community structure and diversity in the maize rhizosphere soil of a coal mine reclamation area. Ann. Microbiol. 2023, 73, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Yu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, G.; Tang, C.; Mathesius, U.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; et al. Rhizosphere-induced shift in the composition of bacterial community favors mineralization of crop residue nitrogen. Plant Soil 2023, 491, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cao, H.; Li, S.; Dong, X.; Zhao, Z.; Jia, Z.; Yuan, L. Genetic and molecular mechanisms underlying nitrogen use efficiency in maize. J. Genet. Genom. 2025, 52, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhtar, H.; Hao, J.; Xu, G.; Bergmeyer, E.; Ulutas, M.; Yang, J.; Schachtman, D.P. Nitrogen input differentially shapes the rhizosphere microbiome diversity and composition across diverse maize lines. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2025, 61, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zheng, X.; Yadav, N.; Saha, S.; Salama, E.S.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Jeon, B.H. Rational management of the plant microbiome for the Second Green Revolution. Plant Commun. 2024, 5, 100812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Liu, Z.; Guo, J.; Jia, Z.; Shi, Y.; Kang, K.; Peng, W.; Wang, Z.; Chen, L.; Neuhaeuser, B.; et al. ZmNRT1.1B (ZmNPF6.6) determines nitrogen use efficiency via regulation of nitrate transport and signalling in maize. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Duan, F.; An, X.; Liu, X.; Hao, D.; Gu, R.; Wang, Z.; Chen, F.; Yuan, L. Overexpression of the maize ZmAMT1;1a gene enhances root ammonium uptake efficiency under low ammonium nutrition. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2018, 12, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, N.M.; Glass, A.D.M. Molecular physiological aspects of nitrate uptake in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 1998, 3, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gojon, A.; Krouk, G.; Perrine-Walker, F.; Laugier, E. Nitrate transceptor(s) in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 2299–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, T.; Conn, V.; Plett, D.; Conn, S.; Zanghellini, J.; Mackenzie, N.; Enju, A.; Francis, K.; Holtham, L.; Roessner, U.; et al. The response of the maize nitrate transport system to nitrogen demand and supply across the lifecycle. New Phytol. 2013, 198, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plett, D.; Toubia, J.; Garnett, T.; Tester, M.; Kaiser, B.N.; Baumann, U. Dichotomy in the NRT gene families of dicots and grass species. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e15289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Tyerman, S.D.; Dechorgnat, J.; Ovchinnikova, E.; Dhugga, K.S.; Kaiser, B.N. Maize NPF6 proteins are homologs of Arabidopsis CHL1 that are selective for both nitrate and chloride. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 2581–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevisan, S.; Borsa, P.; Botton, A.; Varotto, S.; Malagoli, M.; Ruperti, B.; Quaggiotti, S. Expression of two maize putative nitrate transporters in response to nitrate and sugar availability. Plant Biol. 2008, 10, 462–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupini, A.; Mercati, F.; Araniti, F.; Miller, A.J.; Sunseri, F.; Abenavoli, M.R. NAR2.1/NRT2.1 functional interaction with NO3− and H+ fluxes in high-affinity nitrate transport in maize root regions. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 102, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Jin, X.L.; Zhang, Y.B.; Cruz, J.; Vichyavichien, P.; Esiobu, N.; Zhang, X.H. Tobacco plants expressing the maize nitrate transporter ZmNrt2.1 exhibit altered responses of growth and gene expression to nitrate and calcium. Bot. Stud. 2017, 58, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, C.; Wang, Y.; Luo, J.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, X.; Li, Z.; et al. Ferredoxin-mediated mechanism for efficient nitrogen utilization in maize. Nat. Plants 2025, 11, 643–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Cao, Q.; Dong, J.; Qiao, M.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, H.; Xie, H.; Ge, M.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Transcription factor ZmNLP8 modulates nitrate utilization by transactivating ZmNiR1.2 in maize. Plant J. 2025, 122, e70263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, C.; Ge, M.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, W.; Qian, Y.; et al. Time-course transcriptomic analysis reveals transcription factors involved in modulating nitrogen sensibility in maize. J. Genet. Genom. 2025, 52, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, R.; Duan, F.; An, X.; Zhang, F.; von Wiren, N.; Yuan, L. Characterization of AMT-mediated high-affinity ammonium uptake in roots of maize. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013, 54, 1515–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, J.; Liu, Z.; Duan, F.Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.L.; An, X.; Wu, X.Y.; Yuan, L.X. Ammonium-dependent regulation of ammonium transporter ZmAMT1s expression conferred by glutamine levels in roots of maize. J. Integr. Agric. 2022, 21, 2413–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tian, Y.; Wu, K.; Ye, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Q.; Hu, M.; Li, H.; Tong, Y.; et al. Modulating plant growth–metabolism coordination for sustainable agriculture. Nature 2018, 560, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wu, Y.; Chen, W.; Jin, R.; Kong, F.; Ke, Y.; Shi, H.; Yuan, J. Cultivar differences in root nitrogen uptake ability of maize hybrids. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, C.H.; Lin, S.H.; Hu, H.C.; Tsay, Y.F. CHL1 functions as a nitrate sensor in plants. Cell 2009, 138, 1184–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Bankston, J.R.; Payandeh, J.; Hinds, T.R.; Zagotta, W.N.; Zheng, N. Crystal structure of the plant dual-affinity nitrate transporter NRT1.1. Nature 2014, 507, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsay, Y.F. Plant science: How to switch affinity. Nature 2014, 507, 44–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Lawit, S.J.; Weers, B.; Sun, J.; Mongar, N.; Van Hemert, J.; Melo, R.; Meng, X.; Rupe, M.; Clapp, J.H.; et al. Overexpression of zmm28 increases maize grain yield in the field. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 23850–23858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, E.; Tremaroli, V.; Lee, Y.S.; Koren, O.; Nookaew, I.; Fricker, A.; Nielsen, J.; Ley, R.E.; Bäckhed, F. Analysis of gut microbial regulation of host gene expression along the length of the gut and regulation of gut microbial ecology through MyD88. Gut 2012, 61, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.W.; Niu, Y.; Jia, Y.; Ordon, J.; Copeland, C.; Emonet, A.; Geldner, N.; Guan, R.; Stolze, S.C.; Nakagami, H.; et al. Coordination of microbe–host homeostasis by crosstalk with plant innate immunity. Nat. Plants 2021, 7, 814–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.J.P.L.; Colaianni, N.R.; Law, T.F.; Conway, J.M.; Gilbert, S.; Li, H.; Salas-González, I.; Panda, D.; Del Risco, N.M.; Finkel, O.M.; et al. Specific modulation of the root immune system by a community of commensal bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2100678118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucy, M.; Reed, E.; Glick, B.R. Applications of free living plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2004, 86, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugtenberg, B.; Kamilova, F. Plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 63, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, B.; Khan, A.; Tariq, M.; Ramzan, M.; Khan, M.S.I.; Shahid, N.; Aaliya, K. Bottlenecks in commercialisation and future prospects of PGPR. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2017, 121, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, C.M.J.; Berendsen, R.L.; de Jonge, R.; Stringlis, I.A.; Van Dijken, A.J.H.; Van Pelt, J.A.; Van Wees, S.C.M.; Yu, K.; Zamioudis, C.; Bakker, P.A.H.M. Pseudomonas simiae WCS417: Star track of a model beneficial rhizobacterium. Plant Soil 2021, 461, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgarelli, D.; Schlaeppi, K.; Spaepen, S.; van Themaat, E.V.L.; Schulze-Lefert, P. Structure and functions of the bacterial microbiota of plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 807–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Mosqueda, M.D.C.; Santoyo, G.; Glick, B.R. Recent advances in the bacterial phytohormone modulation of plant growth. Plants 2023, 12, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, O.M.; Salas-González, I.; Castrillo, G.; Conway, J.M.; Law, T.F.; Teixeira, P.J.P.L.; Wilson, E.D.; Fitzpatrick, C.R.; Jones, C.D.; Dang, J.L. A single bacterial genus maintains root growth in a complex microbiome. Nature 2020, 587, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, R.; Kaur, T.; Kour, D.; Yadav, A.; Yadav, A.N.; Suman, A.; Ahluwalia, A.S.; Saxena, A.K. Minerals solubilizing and mobilizing microbiomes: A sustainable approach for managing minerals’ deficiency in agricultural soil. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 133, 1245–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giller, K.E.; James, E.K.; Ardley, J.; Unkovich, M.J. Science losing its way: Examples from the realm of microbial N2-fixation in cereals and other non-legumes. Plant Soil 2025, 511, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiruma, K.; Gerlach, N.; Sacristán, S.; Nakano, R.T.; Hacquard, S.; Kracher, B.; Neumann, U.; Ramírez, D.; Bucher, M.; O’Connell, R.J.; et al. Root endophyte Colletotrichum tofieldiae confers plant fitness benefits that are phosphate status dependent. Cell 2016, 165, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, M.J.; Kong, H.G.; Choi, K.; Kwon, S.K.; Song, J.Y.; Lee, J.; Lee, P.A.; Choi, S.Y.; Seo, M.; Lee, H.J.; et al. Rhizosphere microbiome structure alters to enable wilt resistance in tomato. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 1100–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, P.; Leach, J.E.; Tringe, S.G.; Sa, T.; Singh, B.K. Plant-microbiome interactions: From community assembly to plant health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, B.; Liu, W.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Bai, Y. The root microbiome: Community assembly and its contributions to plant fitness. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2022, 64, 509–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quadriya, H.; Mir, M.I.; Surekha, K.; Gopalkrishnan, S.; Khan, M.Y.; Sharma, S.K.; Bee, H. Contribution of microbe-mediated processes in nitrogen cycle to attain environmental equilibrium. In Rhizosphere Microbes; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 331–356. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad, S.; Abbas, Z.; Bashir, S.; Qadir, G.; Khan, S. Nitrogen fixation with non-leguminous plants. Spec. J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 5, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Van Deynze, A.; Zamora, P.; Delaux, P.M.; Heitmann, C.; Jayaraman, D.; Rajasekar, S.; Graham, D.; Maeda, J.; Gibson, D.; Schwartz, K.D.; et al. Nitrogen fixation in a landrace of maize is supported by a mucilage-associated diazotrophic microbiota. PLoS Biol. 2018, 16, e2006352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Hou, X.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, R.; Teng, H.; Yang, Z.; He, J.; Wang, H.; Song, Z.; Zheng, J.; et al. Genetic basis of the mucilage secretion ability associated with nitrogen fixation from aerial roots of maize inbred lines under low nitrogen conditions. Crop J. 2025, 13, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Mi, G.; Chen, F.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, F. Response of root morphology to nitrate supply and its contribution to nitrogen accumulation in maize. J. Plant Nutr. 2007, 30, 2189–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, S.H.; Vijayan, R.; Choudhary, M.; Kumar, A.; Zaid, A.; Singh, V.; Kumar, P.; Yasin, J.K. Nitrogen use efficiency (NUE): Elucidated mechanisms, mapped genes and gene networks in maize (Zea mays L.). Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2021, 27, 2875–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Lin, Z.; Wang, J.; Xu, M.; Lai, J.; Yu, J.; Lin, Z. The genetic architecture of nodal root number in maize. Plant J. 2018, 93, 1032–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, F.; Li, X.; Wei, Z.; Li, J.; Jiang, C.; Jiao, C.; Zhao, S.; Kong, Y.; Yan, M.; Huang, J.; et al. Multi-omics analysis reveals distinct responses to light stress in photosynthesis and primary metabolism between maize and rice. Plant Commun. 2025, 6, 10101488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampitti, I.A.; Lemaire, G. From use efficiency to effective use of nitrogen: A dilemma for maize breeding improvement. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 826, 154125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Ji, M.; Zhu, T.; Wang, Y.; Tang, X.; Zhu, X.; Yang, Z.; Xu, C.; Wang, H.; Li, P. Multi-omics analysis reveals the transcriptional regulatory network of maize roots in response to nitrogen availability. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechorgnat, J.; Francis, K.L.; Dhugga, K.S.; Rafalski, J.A.; Tyerman, S.D.; Kaiser, B.N. Tissue and nitrogen-linked expression profiles of ammonium and nitrate transporters in maize. BMC Plant Soil. 2019, 19, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.B.; Purves, J.V.; Ratcliffe, R.G.; Saker, L.R. Nitrogen assimilation and the control of ammonium and nitrate absorption by maize roots. J. Exp. Bot. 1992, 43, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, S.; Zhang, H.; Chen, S.; Si, J.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Tan, S.; Du, Y.; Jin, Z.; et al. Flavones enrich rhizosphere Pseudomonas to enhance nitrogen utilization and secondary root growth in Populus. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becking, J.H. On the mechanism of ammonium ion uptake by maize roots. Acta Bot. Neerl. 1956, 5, 1–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luo, P.; Yang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, M.; He, Y.; Liu, C.; He, W. Second Genome: Rhizosphere Microbiome as a Key External Driver of Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Maize. Plants 2025, 14, 3680. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233680

Luo P, Yang L, Zhu Y, Liu M, He Y, Liu C, He W. Second Genome: Rhizosphere Microbiome as a Key External Driver of Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Maize. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3680. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233680

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuo, Ping, Lin Yang, Yonghui Zhu, Mao Liu, Yuanyuan He, Chengwei Liu, and Wenzhu He. 2025. "Second Genome: Rhizosphere Microbiome as a Key External Driver of Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Maize" Plants 14, no. 23: 3680. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233680

APA StyleLuo, P., Yang, L., Zhu, Y., Liu, M., He, Y., Liu, C., & He, W. (2025). Second Genome: Rhizosphere Microbiome as a Key External Driver of Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Maize. Plants, 14(23), 3680. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233680