Flowering and Fruiting of Coffea arabica L.: A Comprehensive Perspective from Phenology

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Origin and Distribution

1.2. Climatic Requirements for Cultivation

1.3. Phenology and Its Importance for Flowering and Fruiting

2. Flowering in Coffee

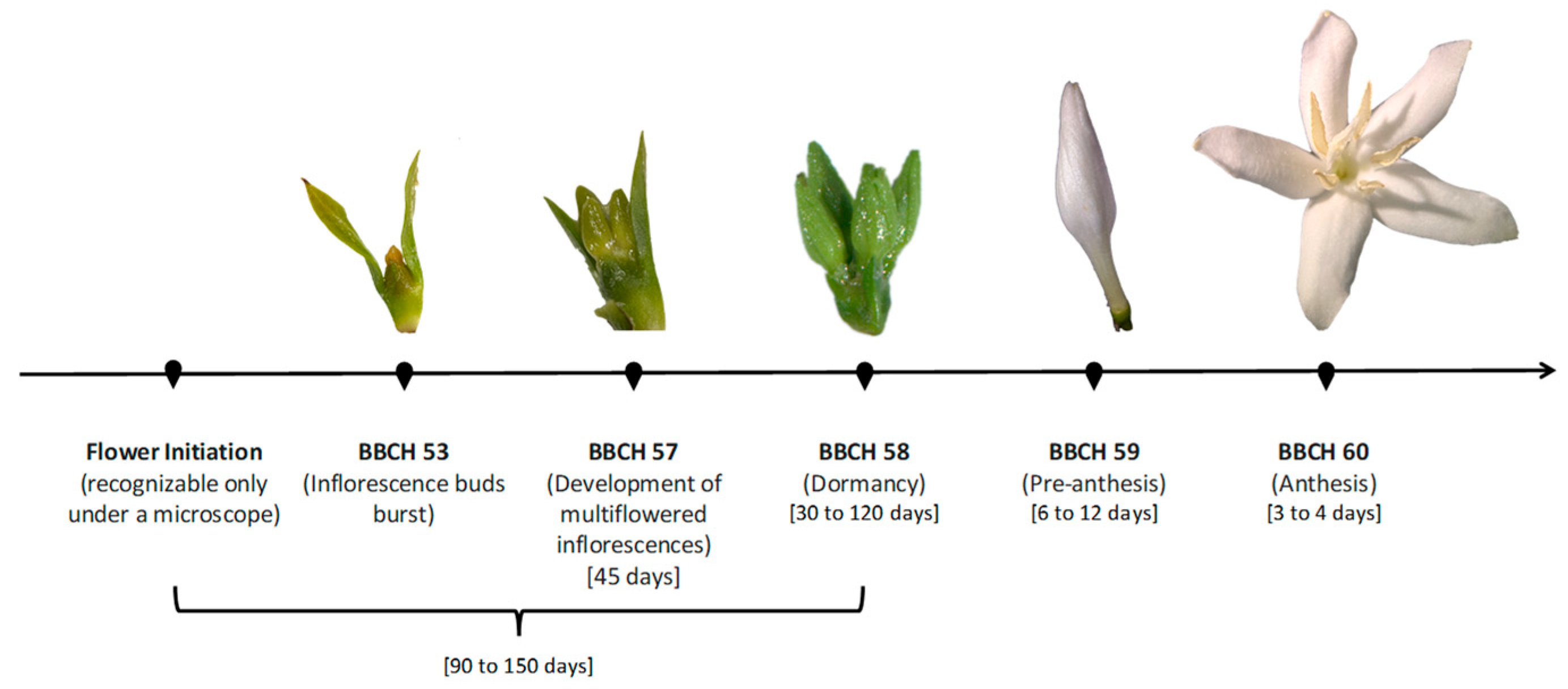

2.1. Development of Flowers

2.1.1. Flower Initiation

2.1.2. Flower Bud Development

Development of Dormancy

Breaking of Dormancy and Stimulus for Growth Resumption Until Anthesis

2.2. Flower Morphology and Characteristics

2.3. Factors Conditioning Flowering

2.3.1. Photoperiod

2.3.2. Plant Water Status and Water Availability

2.3.3. Environmental Temperature

2.3.4. Genotype

3. Fruiting in Coffee

3.1. Fruit Development and Growth

3.1.1. Pinhead Stage (56 DAF)

3.1.2. Rapid Swelling or Filling Stage (57 to 126 DAF)

3.1.3. Suspended and Slow Growth Stage (126 to 140 DAF)

3.1.4. Endosperm Filling Stage (126 to 196 DAF)

3.1.5. Ripe Phase (196 to 224 DAF)

3.2. Fruit Ripening Process

3.3. Fruit Anatomy and Morphology

3.3.1. Pericarp

3.3.2. Seed

3.4. Fruiting and Competition with Vegetative Growth

3.5. Fruit Set and Fruit Drop

3.6. Factors Affecting Fruit Growth and Development

3.6.1. Water Availability

3.6.2. Environmental Temperature

3.6.3. Genotype

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davis, A.P.; Tosh, J.; Ruch, N.; Fay, M.F. Growing Coffee: Psilanthus (Rubiaceae) Subsumed on the Basis of Molecular and Morphological Data; Implications for the Size, Morphology, Distribution and Evolutionary History of Coffea. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2011, 167, 357–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICO Public Market Information. Available online: https://ico.org/resources/public-market-information/ (accessed on 24 August 2021).

- Farah, A.; Ferreira, T. The Coffee Plant and Beans: An Introduction. In Coffee in Health and Disease Prevention; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 5–10. ISBN 978-0-12-409517-5. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, F.; Combes, M.; Astorga, C.; Bertrand, B.; Graziosi, G.; Lashermes, P. The Origin of Cultivated Coffea arabica L. Varieties Revealed by AFLP and SSR Markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2002, 104, 894–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashermes, P.; Combes, M.-C.; Robert, J.; Trouslot, P.; D’Hont, A.; Anthony, F.; Charrier, A. Molecular Characterisation and Origin of the Coffea arabica L. Genome. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1999, 261, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noirot, M.; Charrier, A.; Stoffelen, P.; Anthony, F. Reproductive Isolation, Gene Flow and Speciation in the Former Coffea Subgenus: A Review. Trees 2016, 30, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenci, A.; Combes, M.-C.; Lashermes, P. Genome Evolution in Diploid and Tetraploid Coffea Species as Revealed by Comparative Analysis of Orthologous Genome Segments. Plant Mol. Biol. 2012, 78, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, S.G.; Collazo, J.A.; Stevenson, P.C.; Irwin, R.E. A Comparison of Coffee Floral Traits under Two Different Agricultural Practices. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthaud, J.; Charrier, A. Genetic Resources of Coffea. In Coffee: 4. Agronomy; Clarke, R.J., Macrae, R., Eds.; Elsevier Applied Science: London, UK, 1988; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.F. A History of Coffee. In Coffee: Botany, Biochemistry and Production of Beans and Beverage; Clifford, M.N., Willson, K.C., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1985; pp. 1–12. ISBN 978-1-4615-6657-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, T.; Shuler, J.; Guimãraes, R.; Farah, A. Introduction to Coffee Plant and Genetics. In Coffee: Production, Quality and Chemistry; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2019; pp. 3–25. ISBN 978-1-78262-243-7. [Google Scholar]

- Illy, A.; Viani, R. Espresso Coffee: The Science of Quality; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-12-370371-2. [Google Scholar]

- Flórez, C.P.; Arias, J.C.; Orrego, H.D. Guía para la caracterización de las variedades de café: Claves para su identificación. Av. Téc. Cenicafé 2017, 476, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, J.C. La Colección Colombiana de Café: Conservando la Diversidad Genética para una Caficultura Sostenible; Cenicafé: Manizales, Colombia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Haarer, A.E. Modern Coffee Production, 2nd ed.; Leonard Hill: London, UK, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- DaMatta, F.M.; Avila, R.T.; Cardoso, A.A.; Martins, S.C.V.; Ramalho, J.C. Physiological and Agronomic Performance of the Coffee Crop in the Context of Climate Change and Global Warming: A Review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 5264–5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Vossen, H.; Bertrand, B.; Charrier, A. Next Generation Variety Development for Sustainable Production of Arabica Coffee (Coffea arabica L.): A Review. Euphytica 2015, 204, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitán-Bustamante, A.; Arias, J.C.; Flórez, C.P. Advances in Arabica Coffee Breeding: Developing and Selecting the Right Varieties. In Climate-Smart Production of Coffee: Improving Social and Environmental Sustainability; Muschler, R., Ed.; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2022; pp. 127–167. ISBN 978-1-78676-483-6. [Google Scholar]

- FNC Estadísticas Cafeteras. Available online: https://federaciondecafeteros.org/wp/estadisticas-cafeteras/ (accessed on 26 April 2023).

- Davis, A.P.; Govaerts, R.; Bridson, D.M.; Stoffelen, P. An Annotated Taxonomic Conspectus of the Genus Coffea (Rubiaceae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2006, 152, 465–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moat, J.; Williams, J.; Baena, S.; Wilkinson, T.; Gole, T.W.; Challa, Z.K.; Demissew, S.; Davis, A.P. Resilience Potential of the Ethiopian Coffee Sector under Climate Change. Nat. Plants 2017, 3, 17081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FNC Sistemas de Información Cafetera SIC@. Available online: https://sica.federaciondecafeteros.org/login (accessed on 11 October 2023).

- Ramírez, V.H.; Jaramillo, A.; Arcila, J. Factores climáticos que intervienen en la producción de café en Colombia. In Manual del Cafetero Colombiano; FNC-Cenicafé: Manizales, Colombia, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 205–238. [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo, A. El Clima de la Caficultura en Colombia; FNC—Cenicafé: Manizales, Colombia, 2018; ISBN 978-958-8490-21-2. [Google Scholar]

- DaMatta, F.M.; Ramalho, J.D.C. Impacts of Drought and Temperature Stress on Coffee Physiology and Production: A Review. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2006, 18, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaMatta, F.M. Ecophysiological Constraints on the Production of Shaded and Unshaded Coffee: A Review. Field Crops Res. 2004, 86, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaMatta, F.M.; Rahn, E.; Läderach, P.; Ghini, R.; Ramalho, J.C. Why Could the Coffee Crop Endure Climate Change and Global Warming to a Greater Extent than Previously Estimated? Clim. Change 2019, 152, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho, J.C.; DaMatta, F.M.; Rodrigues, A.P.; Scotti-Campos, P.; Pais, I.; Batista-Santos, P.; Partelli, F.L.; Ribeiro, A.; Lidon, F.C.; Leitão, A.E. Cold Impact and Acclimation Response of Coffea spp. Plants. Theor. Exp. Plant Physiol. 2014, 26, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willson, K.C. Climate and Soil. In Coffee: Botany, Biochemistry and Production of Beans and Beverage; Clifford, M.N., Willson, K.C., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1985; pp. 97–107. ISBN 978-1-4615-6657-1. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, D.; Cure, J.R.; Cotes, J.M.; Gutierrez, A.P.; Cantor, F. A Coffee Agroecosystem Model: I. Growth and Development of the Coffee Plant. Ecol. Model. 2011, 222, 3626–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unigarro, C.A.; Bermudez-Florez, L.N.; Medina, R.D.; Jaramillo, A.; Flórez, C.P. Evaluation of Four Degree-Day Estimation Methods in Eight Colombian Coffee-Growing Areas. Agron. Colomb. 2017, 35, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzopane, J.R.M.; Pedro Júnior, M.J.; de Camargo, M.B.P.; Fazuoli, L.C. Exigência térmica do café arábica cv. Mundo Novo no subperíodo florescimento-colheita. Ciênc. Agrotecnol. 2008, 32, 1781–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lima, E.P.; Silva, E.L.D. Temperatura base, coeficientes de cultura e graus-dia para cafeeiro arábica em fase de implantação. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agríc. Ambient. 2008, 12, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, A.; Guzman, O. Relación entre la temperatura y el crecimiento en Coffea arabica L. variedad Caturra. Rev. Cenicafé 1984, 35, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- DaMatta, F.M.; Ronchi, C.P.; Maestri, M.; Barros, R.S. Ecophysiology of Coffee Growth and Production. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2007, 19, 485–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaMatta, F.M.; Ronchi, C.P.; Maestri, M.; Barros, R.S. Coffee: Environment and Crop Physiology. In Ecophysiology of Tropical Tree Crops; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 181–216. ISBN 978-1-60876-392-4. [Google Scholar]

- Alegre, G. Climats et Caféiers d’Arabie. Agron. Trop. 1959, 14, 23–58. [Google Scholar]

- Caramori, P.H.; Ometto, J.C.; Nova, N.A.; Costa, J.D. Efeitos do vento sobre mudas de cafeeiro Mundo Novo e Catuaí Vermelho. Pesqui. Agropecu. Bras. 1986, 21, 1113–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Primack, R.B. Variation in the Phenology of Natural Populations of Montane Shrubs in New Zealand. J. Ecol. 1980, 68, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, S. Phenological Diversity in Tropical Forests. Popul. Ecol. 2001, 43, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenner, M. The Phenology of Growth and Reproduction in Plants. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 1998, 1, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawa, K.S.; Kang, H.; Grayum, M.H. Relationships among Time, Frequency, and Duration of Flowering in Tropical Rain Forest Trees. Am. J. Bot. 2003, 90, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzinga, J.A.; Atlan, A.; Biere, A.; Gigord, L.; Weis, A.E.; Bernasconi, G. Time after Time: Flowering Phenology and Biotic Interactions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcila, J.; Buhr, L.; Bleiholder, H.; Hack, H.; Meier, U.; Wicke, H. Application of the Extended BBCH Scale for the Description of the Growth Stages of Coffee (Coffea spp.). Ann. Appl. Biol. 2002, 141, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, Â.P.; Camargo, M.B. Definição e esquematização das fases fenológicas do cafeeiro arábica nas condições tropicais do Brasil. Bragantia 2001, 60, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, H.; Caramori, P.H.; Koguishi, M.S.; Ribeiro, A.M.d.A. Escala fenológica detalhada da fase reprodutiva de Coffea arabica. Bragantia 2008, 67, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzopane, J.R.M.; Pedro Júnior, M.J.; Thomaziello, R.A.; de Camargo, M.B.P. Escala para avaliação de estádios fenológicos do cafeeiro arábica. Bragantia 2003, 62, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, U. Growth Stages of Mono- and Dicotyledonous Plants: BBCH Monograph; Instituto Julius Kühn: Quedlinburg, Germany, 2018; ISBN 978-3-95547-071-5. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, M.D. Phenology: An Integrative Environmental Science, 2nd ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, Germany, 2013; ISBN 978-94-007-6925-0. [Google Scholar]

- DaMatta, F.M.; Martins, S.C.V.; Ramalho, J.D.C. Ecophysiology of Coffee Growth and Production in a Context of Climate Changes. In Advances in Botanical Research; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Majerowicz, N.; Söndahl, M.R. Induction and Differentiation of Reproductive Buds in Coffea arabica L. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2005, 17, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.E.; Santos, I.S.; de Oliveira, R.R.; Lima, A.A.; Cardon, C.H.; Chalfun-Junior, A. An Overview of the Endogenous and Environmental Factors Related to the Coffea arabica Flowering Process. Beverage Plant Res. 2021, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.A. Ethylene Regulation Under Different Watering Conditions and Its Possible Involvement in Coffee (Coffea arabica L.) Flowering. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Federal de Lavras, Lavras, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Voltan, R.B.Q.; Fahl, J.I.; Carelli, M.L.C. Diferenciação de gemas florais em cultivares de cafeeiro. Coffee Sci. 2011, 6, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zik, M.; Irish, V.F. Flower Development: Initiation, Differentiation, and Diversification. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2003, 19, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannell, M.G.R. Photoperiodic Response of Mature Trees of Arabica Coffee. Turrialba 1972, 22, 198–206. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, C.M. Fotoperiodismo Em Cafeeiro (Coffea arabica L.). Rev. Inst. Café 1940, 27, 1586–1592. [Google Scholar]

- Piringer, A.A.; Borthwick, H.A. Photoperiodic Responses of Coffee. Turrialba 1955, 5, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Schuch, U.K.; Fuchigami, L.H.; Nagzao, M.A. Effect of Photoperiod on Flower Initiation of Coffee. HortScience 1990, 25, 1071a–11071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drinnan, J.E.; Menzel, C.M. Synchronization of Anthesis and Enhancement of Vegetative Growth in Coffee (Coffea arabica L.) Following Water Stress during Floral Initiation. J. Hortic. Sci. 1994, 69, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drinnan, J.E.; Menzel, C.M. Temperature Affects Vegetative Growth and Flowering of Coffee (Coffea arabica L.). J. Hortic. Sci. 1995, 70, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannell, M.G.R. Physiology of the Coffee Crop. In Coffee; Clifford, M.N., Willson, K.C., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1985; pp. 108–134. ISBN 978-1-4615-6659-5. [Google Scholar]

- Rena, A.B.; Barros, R.S.; Maestri, M.; Söndahl, M.R. Coffee. In Handbook of Environmental Physiology of Tropical Fruit Crops: Sub-Tropical and Tropical Crops; Schaffer, B., Andersen, P.C., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1994; Volume 2, pp. 101–122. ISBN 0-8493-0179-3. [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira, R.R.; Cesarino, I.; Mazzafera, P.; Dornelas, M.C. Flower Development in Coffea arabica L.: New Insights into MADS-Box Genes. Plant Reprod. 2014, 27, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flórez, C.P.; Ibarra, L.N.; Gómez, L.F.; Carmona, C.Y.; Castaño, A.; Ortiz, A. Estructura y funcionamiento de la planta de café. In Manual del Cafetero Colombiano; FNC-Cenicafé: Manizales, Colombia, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 123–168. [Google Scholar]

- Alvim, P.T. Factors Affecting Flowering of Coffee. In Genes, Enzymes, and Populations; Srb, A.M., Ed.; Basic Life Sciences; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1973; pp. 193–202. ISBN 978-1-4684-2880-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, A.A.; Santos, I.S.; Torres, M.E.L.; Cardon, C.H.; Caldeira, C.F.; Lima, R.R.; Davies, W.J.; Dodd, I.C.; Chalfun-Junior, A. Drought and Re-Watering Modify Ethylene Production and Sensitivity, and Are Associated with Coffee Anthesis. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2021, 181, 104289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, R.S.; Maestri, M.; Coons, M.P. The Physiology of Flowering in Coffee: A Review. J. Coffee Res. 1978, 8, 29–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mes, M.G. Studies on the Flowering of Coffea arabica L. Various Phenomena Associated with the Dormancy of the Coffee Flower Buds. Port. Acta Biol. 1957, 5, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Moens, P. Investigaciones Morfológicas, Ecológicas y Fisiológicas Sobre Cafetos. Turrialba 1968, 18, 209–233. [Google Scholar]

- Drinnan, J.E. The Control of Floral Development in Coffee (Coffea arabica L.). Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Camayo, G.C.; Chaves, B.; Arcila, J.; Jaramillo, A. Desarrollo floral del cafeto y su relación con las condiciones climáticas de Chinchiná, Caldas. Coffee Tree Flor. Dev. Its Relat. Chinchiná Caldas Clim. Cond. 2003, 54, 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Mes, M.G. Studies on the Flowering of Coffea arabica L.: II. Breaking the Dormancy of Coffee Flower Buds. Port. Acta Biol. 1957, 4, 342–354. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, C.H.S. Cultivares de Café: Origem, Características e Recomendações; Embrapa Café: Brasília, Brazil, 2008; ISBN 978-85-61619-00-1. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães, A.C.; Angelocci, L.R. Sudden Alterations in Water Balance Associated with Flower Bud Opening in Coffee Plants. J. Hortic. Sci. 1976, 51, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.E.; Silva Santos, I.; Marquez Gutiérrez, R.; Jaramillo Mesa, A.; Cardon, C.H.; Espíndola Lima, J.M.; Almeida Lima, A.; Chalfun-Junior, A. Crosstalk Between Ethylene and Abscisic Acid During Changes in Soil Water Content Reveals a New Role for 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-Carboxylate in Coffee Anthesis Regulation. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 824948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcila, J.; Farfan, F.F.; Moreno, A.M.; Salazar, L.F.; Hincapie, E. Sistemas de Producción de Café en Colombia; Cenicafé: Chinchiná, Colombia, 2007; ISBN 978-958-98193-0-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wintgens, J.N. The Coffee Plant. In Coffee: Growing, Processing, Sustainable Production; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 1–24. ISBN 978-3-527-61962-7. [Google Scholar]

- Arcila, J. Anormalidades en la floración del cafeto. Av. Tec. Cenicafé 2004, 320, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, L.O.E.; Rodrigues, M.J.L.; Ferreira, M.F.S.; De Almeida, R.N.; Ramalho, J.C.; Rakocevic, M.; Partelli, F.L. Modifications in Floral Morphology of Coffea spp. Genotypes at Two Distinct Elevations. Flora 2024, 310, 152443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coste, R. Les Caféiers et les Cafés dans le Monde; Les Cafés; Larose: Paris, France, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, S.M.L.; Constantino-Santos, D.M.A.; Cao, E.P. Pollen Morphometrics of Four Coffee (Coffea sp.) Varieties Grown in the Philippines. Philipp. J. Crop Sci. 2014, 39, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Grierson, W. Fruit Development, Maturation, and Ripening. In Handbook of Plant and Crop Physiology; Pessarakli, M., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001; pp. 143–159. ISBN 978-0-429-20809-6. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, J. Tasa de polinización cruzada del café Arábigo en la región de Chinchiná. Cross Pollinat. Rate Arab. Coffee Chinchiná Reg. 1976, 22, 78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, J.H.; Benavides, P.; Maldonado, J.D.; Jaramillo, J.; Acevedo, F.E.; Gil, Z.N. Flower-Visiting Insects Ensure Coffee Yield and Quality. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipólito, J.; Boscolo, D.; Viana, B.F. Landscape and Crop Management Strategies to Conserve Pollination Services and Increase Yields in Tropical Coffee Farms. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 256, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.-M.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Tscharntke, T. Bee Pollination and Fruit Set of Coffea arabica and C. Canephora (Rubiaceae). Am. J. Bot. 2003, 90, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charrier, A.; Berthaud, J. Botanical Classification of Coffee. In Coffee: Botany, Biochemistry and Production of Beans and Beverage; Clifford, M.N., Willson, K.C., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1985; pp. 13–47. ISBN 978-1-4615-6657-1. [Google Scholar]

- Rahn, E.; Läderach, P.; Vaast, P. Is Coffee Flowering the Bottleneck in Climate Change Adaptation? In Proceedings of the 27th Biennial ASIC Conference, Portland, OR, USA, 16–20 September 2019; Volume 27, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Peña, A.J.; Ramírez, V.H.; Jaramillo, A.; Rendón, J.R.; Arcila, J. Effects of Daylength and Soil Humidity on the Flowering of Coffee Coffea arabica L. in Colombia. Rev. Fac. Nac. Agron. Medellín 2011, 64, 5745–5754. [Google Scholar]

- Camayo, G.C.; Arcila, J. Estudio anatómico y morfológico de la diferenciación y desarrollo de las flores del cafeto Coffea arabica L. variedad Colombia. Rev. Cenicafé 1996, 47, 121–139. [Google Scholar]

- Borchert, R.; Calle, Z.; Strahler, A.H.; Baertschi, A.; Magill, R.E.; Broadhead, J.S.; Kamau, J.; Njoroge, J.; Muthuri, C. Insolation and Photoperiodic Control of Tree Development near the Equator. New Phytol. 2015, 205, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unigarro, C.A.; Imbachí, L.C.; Darghan, A.E.; Flórez-Ramos, C.P. Quantification and Qualification of Floral Patterns of Coffea arabica L. in Colombia. Plants 2023, 12, 3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calle, Z.; Schlumpberger, B.O.; Piedrahita, L.; Leftin, A.; Hammer, S.A.; Tye, A.; Borchert, R. Seasonal Variation in Daily Insolation Induces Synchronous Bud Break and Flowering in the Tropics. Trees 2010, 24, 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeang, H. Synchronous Flowering of the Rubber Tree (Hevea brasiliensis) Induced by High Solar Radiation Intensity. New Phytol. 2007, 175, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renner, S.S. Synchronous Flowering Linked to Changes in Solar Radiation Intensity. New Phytol. 2007, 175, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, A.; Valencia, G. Los elementos climáticos y el desarrollo de Coffea arabica L. en Chinchiná Colombia. Rev. Cenicafé 1980, 31, 127–143. [Google Scholar]

- Alvim, P.T. Moisture Stress as a Requirement for Flowering of Coffee. Science 1960, 132, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisosto, C.H.; Grantz, D.A.; Osgood, R.V.; Cid, L.R. Synchronization of Fruit Ripening in Coffee with Low Concentrations of Ethephon. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 1992, 1, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masarirambi, M.T.; Chingwara, V.; Shongwe, V.D. The Effect of Irrigation on Synchronization of Coffee (Coffea arabica L.) Flowering and Berry Ripening at Chipinge, Zimbabwe. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2009, 34, 786–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rena, A.B.; Maestri, M. Fisiologia do cafeeiro. Inf. Agropecú. 1985, 11, 26–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ronchi, C.P.; Araújo, F.C.; Almeida, W.L.; Silva, M.A.A.; Magalhães, C.E.d.O.; Oliveira, L.B.; Drumond, L.C.D. Respostas ecofisiológicas de cafeeiros submetidos ao deficit hídrico para concentração da florada no Cerrado de Minas Gerais. Pesq. Agropec. Bras. 2015, 50, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchi, C.P.; DaMatta, F.M. Managing the Coffee Crop for Flowering Synchronisation and Fruit Maturation: Agronomic and Physiological Issues. In Advances in Botanical Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; p. S006522962400048X. [Google Scholar]

- Ronchi, C.P.; Miranda, F.R. Flowering Percentage in Arabica Coffee Crops Depends on the Water Deficit Level Applied during the Pre-Flowering Stage. Rev. Caatinga 2020, 33, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, E.A.; Brunini, O.; Sakai, E.; Arruda, F.B.; Pires, R.C. de M. Influência de déficits hídricos controlados na uniformização do florescimento e produção do cafeeiro em três diferentes condições edafoclimáticas do Estado de São Paulo. Bragantia 2009, 68, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.R.; Mantovani, E.C.; Rena, A.B.; Soares, A.A. Irrigação e fisiologia da floração em cafeeiros adultos na região da zona da mata de Minas Gerais. Acta Sci. Agron. 2005, 27, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.A.; Prado, F.M.; Antunes, W.C.; Paiva, R.M.C.; Ferrão, M.A.G.; Andrade, A.C.; Di Mascio, P.; Loureiro, M.E.; DaMatta, F.M.; Almeida, A.M. Reciprocal Grafting between Clones with Contrasting Drought Tolerance Suggests a Key Role of Abscisic Acid in Coffee Acclimation to Drought Stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 85, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, I.S.; Ribeiro, T.H.C.; De Oliveira, K.K.P.; Dos Santos, J.O.; Moreira, R.O.; Lima, R.R.; Lima, A.A.; Chalfun-Junior, A. Multigenic Regulation in the Ethylene Biosynthesis Pathway during Coffee Flowering. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2022, 28, 1657–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, F.R.; Drumond, L.C.D.; Ronchi, C.P. Synchronizing Coffee Blossoming and Fruit Ripening in Irrigated Crops of the Brazilian Cerrado Mineiro Region. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2020, 14, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, A.F.; Rocha, O.C.; Rodrigues, G.C.; Sanzonowicz, C.; Sampaio, J.B.R.; Silva, H.C. Comunicado Técnico Embrapa; Embrapa Cerrados: Brasília, Brazil, 2005; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Schuch, U.K.; Fuchigami, L.H.; Nagao, M.A. Flowering, Ethylene Production, and Ion Leakage of Coffee in Response to Water Stress and Gibberellic Acid. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1992, 117, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, M.K.V. The Water Relations and Irrigation Requirements of Coffee. Ex. Agric. 2001, 37, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, A.; Arcila, J. Variabilidad climática en la zona cafetera colombiana asociada al evento de El Niño y su efecto en la caficultura. Av. Tec. Cenicafé 2009, 390, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo, A.; Arcila, J. Variabilidad climática en la zona cafetera colombiana asociada al evento de La Niña y su efecto en la caficultura. Av. Tec. Cenicafé 2009, 389, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez, V.H.; Jaramillo, A.; Peña, A.J. Gestión del riesgo agroclimático: Vulnerabilidad y capacidad de adaptación del sistema de producción de café. In Manual del Cafetero Colombiano: Investigación y Tecnología para la Sostenibilidad de la Caficultura; Cenicafé: Manizales, Colombia, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 91–114. [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe, R.A.; Dash, J.; Rodriguez-Galiano, V.F.; Janous, D.; Pavelka, M.; Marek, M.V. Extreme Warm Temperatures Alter Forest Phenology and Productivity in Europe. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 563–564, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grab, S.; Craparo, A. Advance of Apple and Pear Tree Full Bloom Dates in Response to Climate Change in the Southwestern Cape, South Africa: 1973–2009. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2011, 151, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mes, M.G. Studies on the Flowering of Coffea arabica L.: I. The Influence of Temperature on the Initiation and Growth of Coffee Flower Buds. Port. Acta Biol. 1957, 4, 328–334. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, D. Some Aspects of the Physiology of Coffea arabica L. A Review. Kenya Coffee 1979, 44, 9–47. [Google Scholar]

- Camargo, Â.P. Florescimento e frutificação de café arábica nas diferentes regiões (cafeeiras) do Brasil. Pesqui. Agropecu. Bras. 1985, 20, 831–839. [Google Scholar]

- Browning, G. Flower Bud Dormancy in Coffea arabica L. I. Studies of Gibberellin in Flower Buds and Xylem Sap and of Abscisic Acid in Flower Buds in Relation to Dormancy Release. J. Hortic. Sci. 1973, 48, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, R.S.; Mota, J.W.d.S.; Da Matta, F.M.; Maestri, M. Decline of Vegetative Growth in Coffea arabica L. in Relation to Leaf Temperature, Water Potential and Stomatal Conductance. Field Crops Res. 1997, 54, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myster, J.; Moe, R. Effect of Diurnal Temperature Alternations on Plant Morphology in Some Greenhouse Crops—A Mini Review. Sci. Hortic. 1995, 62, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, A.O.; de Camargo, M.B.P.; Fazuoli, L.C. Modelo agrometeorológico de estimativa do início da florada plena do cafeeiro. Bragantia 2008, 67, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, V.H.; Arcila, J.; Jaramillo, A.; Rendón, J.R.; Cuesta, G.; Menza, H.D.; Mejia, C.G.; Montoya, D.F.; Mejia, J.W.; Torres, J.C.; et al. Floración del café en Colombia y su relación con la disponibilidad hídrica térmica y de brillo solar. Rev. Cenicafé 2010, 61, 132–158. [Google Scholar]

- Breitler, J.C.; Etienne, H.; Léran, S.; Marie, L.; Bertrand, B. Description of an Arabica Coffee Ideotype for Agroforestry Cropping Systems: A Guideline for Breeding More Resilient New Varieties. Plants 2022, 11, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.; Krug, C.A. Hereditariedade Dos Característicos Principais de Coffea arabica L. Var. Semperflorens K.M.C. Bragantia 1952, 12, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.L.S.; Carmello-Guerreiro, S.M.; Mazzafera, P. A Functional Role for the Colleters of Coffee Flowers. AoB Plants 2013, 5, plt029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo, D.M.; Riaño, N.M.; López, J.C.; López, Y. Intercambio de dióxido de carbono y cambios bioquímicos del pericarpio durante el desarrollo del fruto del cafeto. Rev. Cenicafé 2010, 61, 327–343. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, M.R.; Cháves, B.; Riaño, N.M.; Arcila, J.; Jaramillo, A. Crecimiento Del Fruto de Café Coffea arabica L. Var Colombia. Cenicafé 1994, 45, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cannell, M.G.R. Crop Physiological Aspects of Coffee Bean Yield: A Review. J. Coffee Res. 1975, 1/2, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- De Castro, R.D.; Marraccini, P. Cytology, Biochemistry and Molecular Changes during Coffee Fruit Development. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2006, 18, 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaMatta, F.M. Coffee Tree Growth and Environmental Acclimation. In Achieving Sustainable Cultivation of Coffee; Lashermes, P., Ed.; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 21–48. ISBN 978-1-78676-152-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cannell, M.G.R. Changes in the Respiration and Growth Rates of Developing Fruits of Coffea arabica L. J. Hortic. Sci. 1971, 46, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, M.R.; Riaño, N.M.; Arcila, J.; Ponce, C.A. Estudio morfológico anatómico y ultraestructural del fruto de café Coffea arabica L. Rev. Cenicafé 1994, 45, 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- Farah, A. Coffee: Production, Quality and Chemistry; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-78262-004-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, L.F.P.; Galvão, R.M.; Kobayashi, A.K.; Cação, S.M.B.; Vieira, L.G.E. Ethylene Production and Acc Oxidase Gene Expression during Fruit Ripening of Coffea arabica L. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2005, 17, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, S.M.; Arcila, J.; Montoya, E.C.; Oliveros, C.E. Cambios físicos y químicos durante la maduración del fruto de café (Coffea arabica L. var. Colombia). Rev. Cenicafé 2003, 54, 208–225. [Google Scholar]

- Lelievre, J.-M.; Latche, A.; Jones, B.; Bouzayen, M.; Pech, J.-C. Ethylene and Fruit Ripening. Physiol. Plant 1997, 101, 727–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanna, V.; Prabha, T.N.; Tharanathan, R.N. Fruit Ripening Phenomena–An Overview. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2007, 47, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio Pérez, V.; Matallana Pérez, L.G.; Fernandez-Alduenda, M.R.; Alvarez Barreto, C.I.; Gallego Agudelo, C.P.; Montoya Restrepo, E.C. Chemical Composition and Sensory Quality of Coffee Fruits at Different Stages of Maturity. Agronomy 2023, 13, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ságio, S.A.; Barreto, H.G.; Lima, A.A.; Moreira, R.O.; Rezende, P.M.; Paiva, L.V.; Chalfun-Junior, A. Identification and Expression Analysis of Ethylene Biosynthesis and Signaling Genes Provides Insights into the Early and Late Coffee Cultivars Ripening Pathway. Planta 2014, 239, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ságio, S.A.; Lima, A.A.; Barreto, H.G.; de Carvalho, C.H.S.; Paiva, L.V.; Chalfun-Junior, A. Physiological and Molecular Analyses of Early and Late Coffea arabica Cultivars at Different Stages of Fruit Ripening. Acta Physiol. Plant 2013, 35, 3091–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, G.R.; Mendes, A.N.G.; Carvalho, L.F.; Bartholo, G.F. Eficiência do Ethephon na uniformização e antecipação da maturação de frutos de cafeeiro (Coffea arabica L.) e na qualidade da bebida. Ciênc. agrotec. 2003, 27, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudeler, F.; Raetano, C.G.; de Araújo, D.; Bauer, F.C. Cobertura da pulverização e maturação de frutos do cafeeiro com ethephon em diferentes condições operacionais. Bragantia 2004, 63, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winston, E.; Hoult, M.; Howitt, C.; Shepherd, R. Ethylene-Induced Fruit Ripening in Arabica Coffee (Coffea arabica L.). Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 1992, 32, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspari-Pezzopane, C.D.; Bonturi, N.; Guerreiro Filho, O.; Favarin, J.L.; Maluf, M.P. Gene Expression Profile during Coffee Fruit Development and Identification of Candidate Markers for Phenological Stages. Pesq. Agropec. Bras. 2012, 47, 972–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geromel, C. Biochemical and Genomic Analysis of Sucrose Metabolism during Coffee (Coffea arabica) Fruit Development. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 3243–3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Privat, I.; Foucrier, S.; Prins, A.; Epalle, T.; Eychenne, M.; Kandalaft, L.; Caillet, V.; Lin, C.; Tanksley, S.; Foyer, C.; et al. Differential Regulation of Grain Sucrose Accumulation and Metabolism in Coffea arabica (Arabica) and Coffea canephora (Robusta) Revealed through Gene Expression and Enzyme Activity Analysis. New Phytol. 2008, 178, 781–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, W.J.; Michaux, S.; Bastin, M.; Bucheli, P. Changes to the Content of Sugars, Sugar Alcohols, Myo-Inositol, Carboxylic Acids and Inorganic Anions in Developing Grains from Different Varieties of Robusta (Coffea canephora) and Arabica (C. arabica) Coffees. Plant Sci. 1999, 149, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joët, T.; Laffargue, A.; Salmona, J.; Doulbeau, S.; Descroix, F.; Bertrand, B.; de Kochko, A.; Dussert, S. Metabolic Pathways in Tropical Dicotyledonous Albuminous Seeds: Coffea arabica as a Case Study. New Phytol. 2009, 182, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzopane, J.R.M.; Salva, T.d.J.G.; de Lima, V.B.; Fazuoli, L.C. Agrometeorological Parameters for Prediction of the Maturation Period of Arabica Coffee Cultivars. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2012, 56, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinoco, H.A.; Buitrago-Osorio, J.; Perdomo-Hurtado, L.; Lopez-Guzman, J.; Ibarra, C.A.; Rincon-Jimenez, A.; Ocampo, O.; Berrio, L.V. Experimental Assessment of the Elastic Properties of Exocarp–Mesocarp and Beans of Coffea arabica L. Var. Castillo Using Indentation Tests. Agriculture 2022, 12, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Melo Pereira, G.V.; De Carvalho Neto, D.P.; Magalhães Júnior, A.I.; Vásquez, Z.S.; Medeiros, A.B.P.; Vandenberghe, L.P.S.; Soccol, C.R. Exploring the Impacts of Postharvest Processing on the Aroma Formation of Coffee Beans—A Review. Food Chem. 2019, 272, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanke, M.M.; Lenz, F. Fruit Photosynthesis. Plant Cell Environ. 1989, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, F.S.; Wolfgramm, R.; Gonçalves, F.V.; Cavatte, P.C.; Ventrella, M.C.; DaMatta, F.M. Phenotypic Plasticity in Response to Light in the Coffee Tree. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2009, 67, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braham, J.E.; Bressani, R. (Eds.) Coffee Pulp: Composition, Technology, and Utilization; IDRC: Ottawa, ON, USA, 1979; ISBN 0-88936-190-8. [Google Scholar]

- Del Castillo, M.D.; Fernandez-Gomez, B.; Martinez-Saez, N.; Iriondo-DeHond, A.; Mesa, M.D. Coffee By-Products. In Coffee: Production, Quality and Chemistry; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2019; pp. 309–334. ISBN 978-1-78262-243-7. [Google Scholar]

- Esquivel, P.; Jiménez, V.M. Functional Properties of Coffee and Coffee By-Products. Food Res. Int. 2012, 46, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekalo, S.A.; Reinhardt, H.W. Fibers of Coffee Husk and Hulls for the Production of Particleboard. Mater. Struct. 2010, 43, 1049–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedecca, D.M. Anatomia e desenvolvimento ontogenético de Coffea arabica L. var. typica Cramer. Bragantia 1957, 16, 315–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, A.J.T. Observações citológicas em Coffea vi—Desenvolvimento do embrião e do endosferma em Coffea arabica L. Bragantia 1942, 2, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbachí, L.C.; Medina, R.; Sanz, J.R. Caracterización del tamaño de los granos de café despulpados en nuevas variedades de café. Rev. Cenicafé 2023, 74, e74206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Dussán, E.; Sanz-Uribe, J.R.; Dussán-Lubert, C.; Banout, J. Thermophysical Properties of Parchment Coffee: New Colombian Varieties. J. Food Process Eng. 2023, 46, e14300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, P.S.; Madhava Naidu, M. Sustainable Management of Coffee Industry By-Products and Value Addition—A Review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2012, 66, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentan, E. The Microscopic Structure of the Coffee Bean. In Coffee; Clifford, M.N., Willson, K.C., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1985; pp. 284–304. ISBN 978-1-4615-6659-5. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfrom, M.L.; Patin, D.L. Coffee Constituents, Isolation and Characterization of Cellulose in Coffee Bean. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1964, 12, 376–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcila, M.; Orozco, F. Estudio morfológico del desarrollo del embrión de café. Rev. Cenicafé 1987, 38, 62–78. [Google Scholar]

- Eira, M.T.S.; Silva, E.A.A.D.; De Castro, R.D.; Dussert, S.; Walters, C.; Bewley, J.D.; Hilhorst, H.W.M. Coffee Seed Physiology. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2006, 18, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendón, J.R. Administración de sistemas de producción de café a libre exposición solar. In Manejo Agrónomico de los Sitemas de Producción de Café; 80 Años de Ciencia Para la Caficultura Colombiana; Cenicafé: Manizales, Colombia, 2020; pp. 34–71. ISBN 978-958-8490-44-1. [Google Scholar]

- Upegui, G.; Valencia, G. Anticipación de la maduración de la cosecha de cafe con aplicaciones de ethrel. Rev. Cenicafé 1972, 23, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bote, A.D.; Jan, V. Branch Growth Dynamics, Photosynthesis, Yield and Bean Size Distribution in Response to Fruit Load Manipulation in Coffee Trees. Trees 2016, 30, 1275–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, V.M.; Aristizábal, I.D.; Moreno, E.L. Evaluation of the Composition Effect of Harvested Coffee in the Organoleptic Properties of Coffee Drink. Vitae 2017, 24, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, Â.M.; Carvalho, S.P.D.; Bartholo, G.F.; Mendes, A.N.G. Avaliação da maturação dos frutos de linhagens das cultivares Catuaí Amarelo e Catuaí Vermelho (Coffea arabica L.) plantadas individualmente e em combinações. Ciênc. Agrotec. 2005, 29, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Burgos, A.F.; Rendón, J.R.; Jaramillo-Jiménez, A.; Imbachi, L.C.; Flórez-Ramos, C.P. Asociación entre crecimiento vegetativo y carga de frutos en formación con progenies de Coffea arabica L. Rev. Cenicafé 2024, 75, e75201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannell, M.G.R. Factors Affecting Arabica Coffee Bean Size in Kenya. J. Hortic. Sci. 1974, 49, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Burgos, A.F.; Rendón, J.R.; Imbachi, L.C.; Toro-Herrera, M.A.; Unigarro, C.A.; Osorio, V.; Balaguera-López, H.E. Increased Fruit Load Influences Vegetative Growth, Dry Mass Partitioning, and Bean Quality Attributes in Full-Sun Coffee Cultivation. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1379207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unigarro, C.A.; Díaz, L.M.; Acuña, J.R. Effect of Fruit Load of the First Coffee Harvests on Leaf Gas Exchange. Pesqui. Agropecu. Trop. 2021, 51, e69865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Burgos, A.F.; Rendón, J.R.; Imbachi, L.C.; Unigarro, C.A.; Osorio, V.; Sadeghian, S.; Balaguera-López, H.E. Varying Fruit Loads Modified Leaf Nutritional Status, Photosynthetic Performance, and Bean Biochemical Composition of Coffee Trees. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 329, 113005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaast, P.; Angrand, J.; Franck, N.; Dauzat, J.; Genard, M. Fruit Load and Branch Ring-Barking Affect Carbon Allocation and Photosynthesis of Leaf and Fruit of Coffea arabica in the Field. Tree Physiol. 2005, 25, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaMatta, F.M.; Cunha, R.L.; Antunes, W.C.; Martins, S.C.V.; Araujo, W.L.; Fernie, A.R.; Moraes, G.A.B.K. In Field-Grown Coffee Trees Source–Sink Manipulation Alters Photosynthetic Rates, Independently of Carbon Metabolism, via Alterations in Stomatal Function. New Phytol. 2008, 178, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannell, M.G.R. Production and Distribution of Dry Matter in Trees of Coffea arabica L. in Kenya as Affected by Seasonal Climatic Differences and the Presence of Fruits. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1971, 67, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreaux, C.; Meireles, D.A.L.; Sonne, J.; Badano, E.I.; Classen, A.; González-Chaves, A.; Hipólito, J.; Klein, A.-M.; Maruyama, P.K.; Metzger, J.P.; et al. The Value of Biotic Pollination and Dense Forest for Fruit Set of Arabica Coffee: A Global Assessment. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 323, 107680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marco, P.; Coelho, F.M. Services Performed by the Ecosystem: Forest Remnants Influence Agricultural Cultures’ Pollination and Production. Biodivers. Conserv. 2004, 13, 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philpott, S.M.; Uno, S.; Maldonado, J. The Importance of Ants and High-Shade Management to Coffee Pollination and Fruit Weight in Chiapas, Mexico. Biodivers. Conserv. 2006, 15, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, C.G.; Kumar, P.; D’souza, G.F. Pre-Mature Fruit Drop and Coffee Production in India: A Review. Ind. J. Plant Physiol. 2014, 19, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unigarro, C.A.; Imbachí, L.C.; Pabón, J.P.; Osorio, V.; Acuña, J.R. Efecto del ácido salicílico sobre la maduración fenológica de frutos de café en pre-cosecha. Rev. Cenicafé 2021, 72, e72205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, G.; Arcila, J. Secamiento y caída de frutos tiernos de café. Av. Téc. Cenicafé 1975, 40, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia, A.G. Factores que inciden en la formación de granos negros y caída de frutos verdes de café. Rev. Cenicafé 1973, 24, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira Aparecido, L.E.; Rolim, G.D.S.; Moraes, J.R.D.S.C.D.; Valeriano, T.T.B.; Lense, G.H.E. Maturation Periods for Coffea arabica Cultivars and Their Implications for Yield and Quality in Brazil. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 3880–3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonimous Skin Cracking of the Fruit or Berry. Available online: https://www.hawaiicoffeeed.com/skin-cracking.html (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Craparo, A.C.W.; Van Asten, P.J.A.; Läderach, P.; Jassogne, L.T.P.; Grab, S.W. Warm Nights Drive Coffea arabica Ripening in Tanzania. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2021, 65, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DaMatta, F.M. Crop Physiology. In Specialty Coffee: Managing Quality; Oberthür, T., Läderach, P., Pohlan, H.A.J., Tan, P.L., Cock, J.H., Eds.; Cropster GmbH: Innsbruck, Austria, 2019; pp. 86–108. [Google Scholar]

- Vaast, P.; Bertrand, B.; Perriot, J.J.; Guyot, B.; Génard, M. Fruit Thinning and Shade Improve Bean Characteristics and Beverage Quality of Coffee (Coffea arabica L.) under Optimal Conditions. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2006, 86, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin-Camparotto, L.; Camargo, M.B.P.D.; Moraes, J.F.L.D. Época provável de maturação para diferentes cultivares de café arábica para o Estado de São Paulo. Cienc. Rural 2012, 42, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosselmann, A.S.; Dons, K.; Oberthur, T.; Olsen, C.S.; Ræbild, A.; Usma, H. The Influence of Shade Trees on Coffee Quality in Small Holder Coffee Agroforestry Systems in Southern Colombia. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2009, 129, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, E.B.; de Souza, C.H.E.; Pereira, N.M.B.; Machado, V.J. Efeito do tempo de formação do grão de café (Coffea sp.) na qualidade da bebida. Biosci. J. 2011, 27, 729–738. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva Angelo, P.C.; Ferreira, I.B.; De Carvalho, C.H.S.; Matiello, J.B.; Sera, G.H. Arabica Coffee Fruits Phenology Assessed through Degree Days, Precipitation, and Solar Radiation Exposure on a Daily Basis. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2019, 63, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Unigarro, C.A.; Cayón Salinas, D.G.; León-Burgos, A.F.; Flórez-Ramos, C.P. Flowering and Fruiting of Coffea arabica L.: A Comprehensive Perspective from Phenology. Plants 2025, 14, 3396. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213396

Unigarro CA, Cayón Salinas DG, León-Burgos AF, Flórez-Ramos CP. Flowering and Fruiting of Coffea arabica L.: A Comprehensive Perspective from Phenology. Plants. 2025; 14(21):3396. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213396

Chicago/Turabian StyleUnigarro, Carlos Andres, Daniel Gerardo Cayón Salinas, Andrés Felipe León-Burgos, and Claudia Patricia Flórez-Ramos. 2025. "Flowering and Fruiting of Coffea arabica L.: A Comprehensive Perspective from Phenology" Plants 14, no. 21: 3396. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213396

APA StyleUnigarro, C. A., Cayón Salinas, D. G., León-Burgos, A. F., & Flórez-Ramos, C. P. (2025). Flowering and Fruiting of Coffea arabica L.: A Comprehensive Perspective from Phenology. Plants, 14(21), 3396. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14213396