Critical Success Factors of Participatory Community Planning with Geospatial Digital Participatory Platforms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

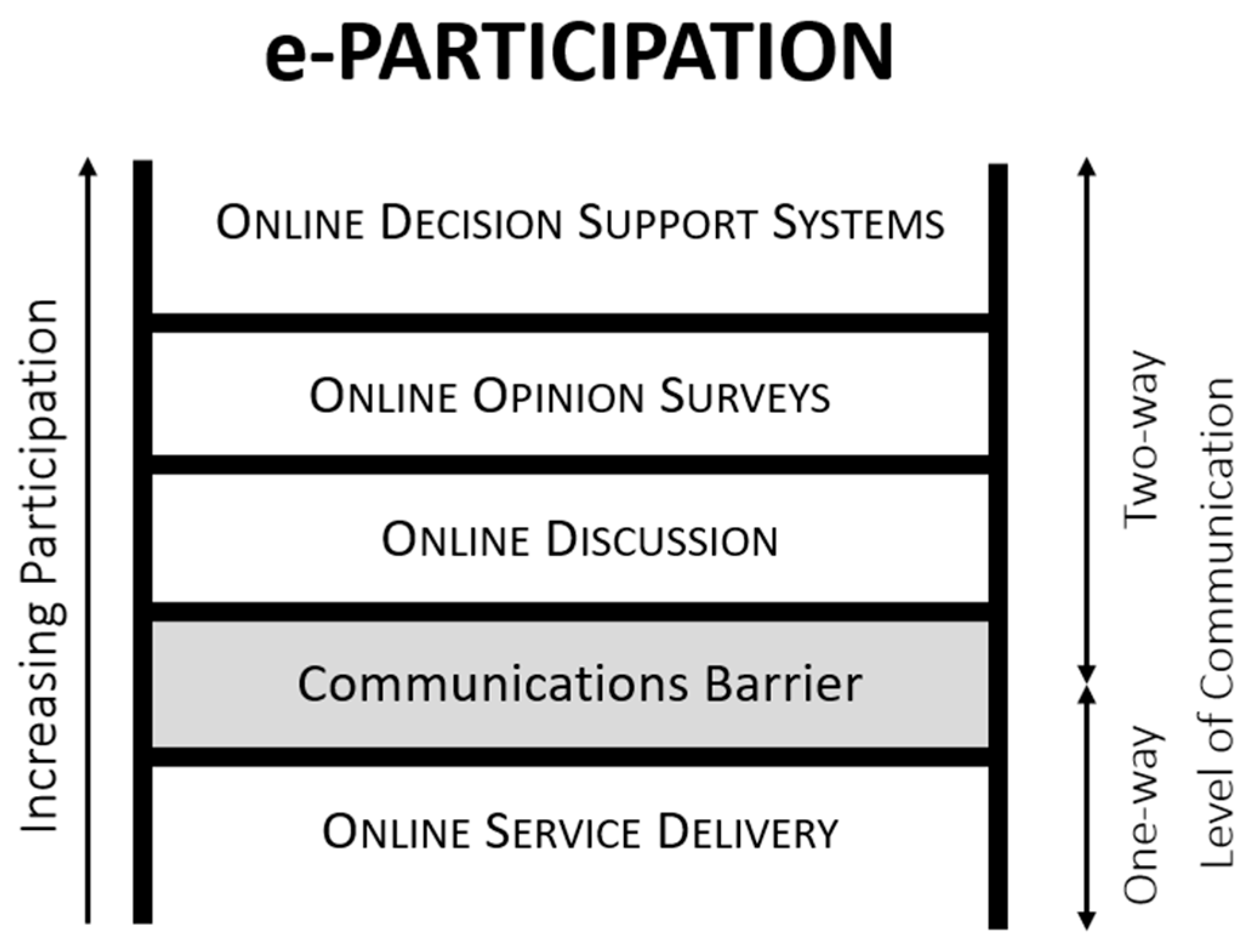

2.1. Digital Participatory Platforms

2.2. Critical Success Factors of Geospatial Digital Participatory Platforms

2.3. An Example DPP: The ‘Bürgercockpit’-Application for Participatory Community Planning

3. Materials and Methods

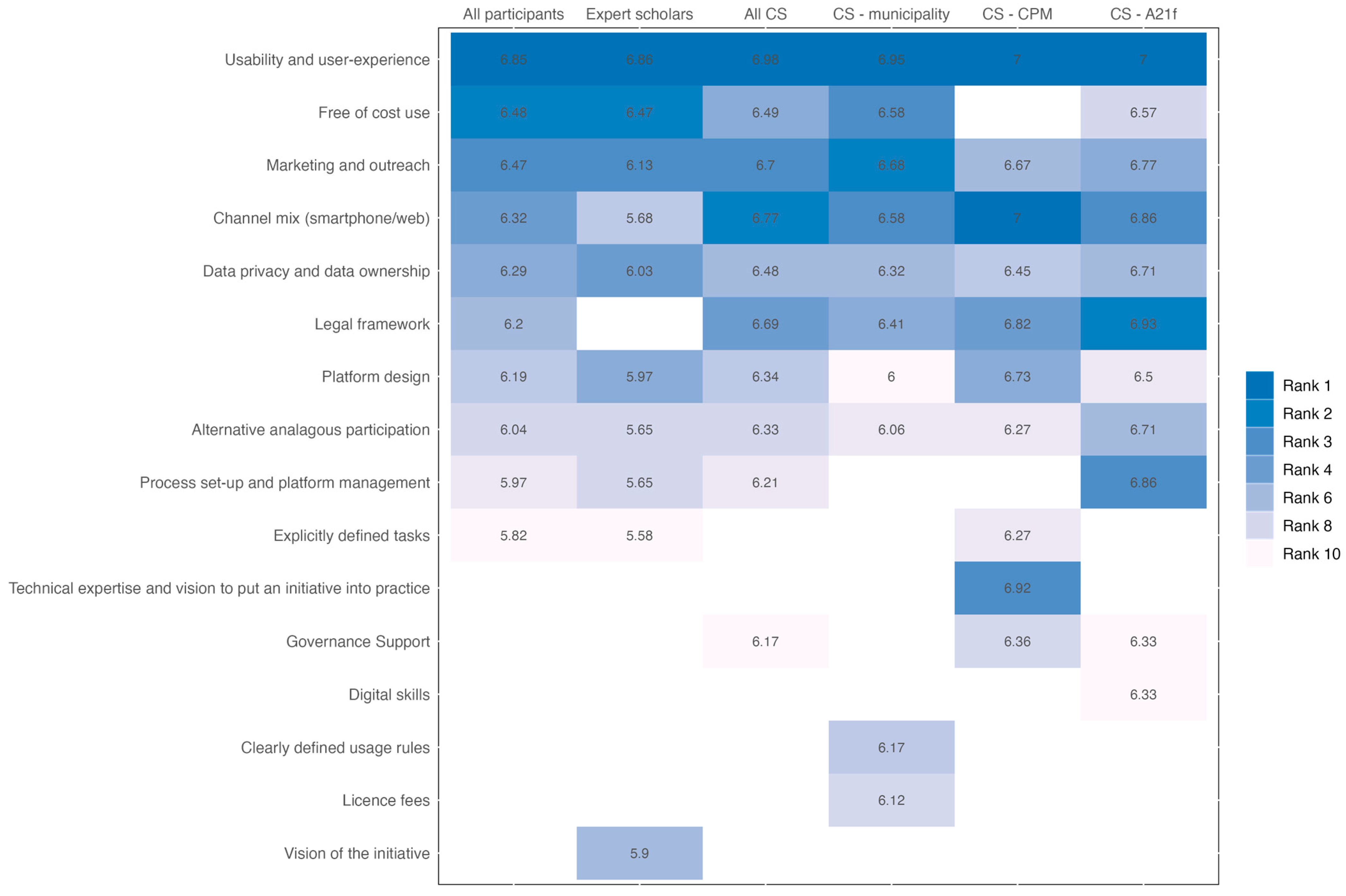

3.1. CSF-Set

3.2. CSF-Questionnaire

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Questionnaire Section 1: Assessment of the Potential, Opportunities, and Challenges of Integrating Geospatial DPPs into Participatory Community Planning

4.2. Questionnaire Section 2: Assessment of the Most Important Critical Success Factors of Participatory Community Planning with Geospatial DPPs

4.3. Experiences of the Piloting Phase and Commercial Roll-Out of the ‘Bürgercockpit’-Application

4.4. Integrating the Spatial Domain into Digital Participatory Platforms

5. Conclusions

- →

- Utilize geospatial DPPs in small-scale projects that are integrated into existing decision-making structures to complement well-established analog participatory community planning processes rather than replacing them!

- →

- Employ simple, intuitive, and multi-device applications, and provide proper training as well as technical support to empower digitally and spatially less literate community members to engage in the participatory community planning process!

- →

- Ensure a transparent and efficient process management and communication framework to build trust in the use of geospatial DPPs as part of a participatory process!

- →

- Implement a well-designed and transparent marketing and dissemination strategy for the participatory process in general and the use of geospatial DPPs, in particular, to address a representative share of a community!

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Keenan, P.B.; Jankowski, P. Spatial Decision Support Systems: Three decades on. Decis. Support Syst. 2019, 116, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, M.; Dionisio, R.; Kingham, S. Challenges of Spatial Decision-Support Tools in Urban Planning: Lessons from New Zealand’s Cities. J. Urban Plann. Dev. 2020, 146, 04020012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotzov, V.; Rossignol, N. Regional and National Spatial Planning: New Challenges and New Opportunities: Transnational Observation; ESPON: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Agenda 21: United Nations Conference on Environment & Development 1992: Chapter 30; United Nations: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023: Special Edition; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-92-1-101460-0. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee of the Regions—Commission for Natural Resources. From Local to European: Putting Citizens at the Centre of the EU Agenda; Publications Office of the EU: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cheshmehzangi, A.; Dawodu, A. (Eds.) Sustainable Urban Development in the Age of Climate Change: People: The Cure or Curse; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2019; ISBN 978-981-13-1388-2. [Google Scholar]

- Cinderby, S.; de Bruin, A.; Cambridge, H.; Muhoza, C.; Ngabirano, A. Transforming urban planning processes and outcomes through creative methods. Ambio 2021, 50, 1018–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szetey, K.; Moallemi, E.A.; Ashton, E.; Butcher, M.; Sprunt, B.; Bryan, B.A. Participatory planning for local sustainability guided by the Sustainable Development Goals. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardal, K.G.; Reinar, M.B.; Lundberg, A.K.; Bjørkan, M. Factors Facilitating the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals in Regional and Local Planning—Experiences from Norway. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weymouth, R.; Hartz-Karp, J. Principles for Integrating the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals in Cities. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Eckold, H. An evaluation of public participation information for land use decisions: Public comment, surveys, and participatory mapping. Local Environ. 2020, 25, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, E.; Fredriksson, A.; Syssner, J. Opening the black box of participatory planning: A study of how planners handle citizens’ input. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2022, 30, 994–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbio, L. Designing effective public participation. Policy Soc. 2019, 38, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder Of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amdam, R. Empowerment Planning in Regional Development. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2010, 18, 1805–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeraro, T.; Nicola, Z.; Lara, A.; Sergi Cucinelli, F.; Aretano, R. A Bottom-Up and Top-Down Participatory Approach to Planning and Designing Local Urban Development: Evidence from an Urban University Center. Land 2020, 9, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sève, B.; Redondo Domínguez, E.; Sega, R. A Taxonomy of Bottom-Up, Community Planning and Participatory Tools in the Urban Planning Context. ACE 2022, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koontz, T.M.; Newig, J. From Planning to Implementation: Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches for Collaborative Watershed Management. Policy Stud. J. 2014, 42, 416–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claridge, T. Designing Social Capital Sensitive Participation Methodologies; Social Capital Research: Brisbane, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, P. Empowerment through Participation: How Effective Is This Approach? Econ. Political Wkly. 2003, 38, 2484–2486. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, F. Democracy and Expertise: Reorienting Policy Inquiry; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; ISBN 9780191557804. [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff, P. Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1965, 31, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damer, S.; Hague, C. Public Participation in Planning: A Review. Town Plan. Rev. 1971, 42, 217–232. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, J. Retracking America: A Theory of Transactive Planning; Anchor: Albany, NY, USA, 1973; ISBN 0385006799. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.W. A theoretical basis for participatory planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romariz Peixoto, L.; Rectem, L.; Pouleur, J.-A. Citizen Participation in Architecture and Urban Planning Confronted with Arnstein’s Ladder: Four Experiments into Popular Neighbourhoods of Hainaut Demonstrate Another Hierarchy. Architecture 2022, 2, 114–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M.B. Public Participation in Planning: An intellectual history. Aust. Geogr. 2005, 36, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachapelle, P. A Sense of Ownership in Community Development: Understanding the Potential for Participation in Community Planning Efforts. Community Dev. 2008, 39, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legacy, C. Is there a crisis of participatory planning? Plan. Theory 2017, 16, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyea, W. Place Making Through Participatory Planning. In Handbook of Research on Urban Informatics: The Practice and Promise of the Real-Time City; Foth, M., Ed.; Information Science Reference: Hershey, PA, USA, 2009; pp. 55–67. ISBN 9781605661520. [Google Scholar]

- Eun, J. Consensus Building through Participatory Decision-Making. Gest. Manag. Public 2017, 5, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margerum, R.D. Collaborative Planning. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2002, 21, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.L.A. Community Planning. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 1078–1080. ISBN 978-94-007-0752-8. [Google Scholar]

- Boroushaki, S.; Malczewski, J. Measuring consensus for collaborative decision-making: A GIS-based approach. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2010, 34, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzalan, N.; Sanchez, T.W.; Evans-Cowley, J. Creating smarter cities: Considerations for selecting online participatory tools. Cities 2017, 67, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Chin, S.Y.W. Assessing the Effectiveness of Public Participation in Neighbourhood Planning. Plan. Pract. Res. 2013, 28, 563–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.; Meyer, J.; Wright, M.; Zykofsky, P. Participation Tools for Better Community Planning. Available online: https://civicwell.org/civic-resources/participation-tools-for-better-community-planning/ (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Harnecker, M.; Bartolomé, J.; López, N. Planning from Below: A Decentralized Participatory Planning Proposal; Monthly Review Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 9781583677568. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, F. Participatory Governance; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, E.C.; Chen, T.; Lang, W.; Ou, Y. Urban community regeneration and community vitality revitalization through participatory planning in China. Cities 2021, 110, 103072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucotelli Salice, S. Creative Revitalization of the Urban Space: The Residual Areas Project in Turin. In The Urban Gaze: Exploring Urbanity Through Art, Architecture, Music, Fashion, Film and Media; Salice, S.M., Ed.; BRILL: Leiden, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 119–127. ISBN 9781848884533. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, M. Participatory Rural Planning: Exploring Evidence from Ireland; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 9781315599526. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Community-Led Local Development (CLLD). Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/leader-clld_en (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Chambers, R. The origins and practice of participatory rural appraisal. World Dev. 1994, 22, 953–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmis, S.; McTaggart, R.; Nixon, R. Introducing Critical Participatory Action Research. In The Action Research Planner; Springer: Singapore, 2014; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Strydom, W.J.; Puren, K. From space to place in urban planning: Facilitating change through Participatory Action Research. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2014, 191, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzmanstorfer, K.; Resl, R.; Eitzinger, A.; Izurieta, X. The GeoCitizen-approach: Community-based spatial planning—An Ecuadorian case study. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2014, 41, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, M.A.; Hendricks, M.; Newman, G.D.; Masterson, J.H.; Cooper, J.T.; Sansom, G.; Gharaibeh, N.; Horney, J.; Berke, P.; van Zandt, S.; et al. Participatory action research: Tools for disaster resilience education. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2018, 9, 402–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Min, C.; Zhang, W.; Wang, G.; Ma, X.; Evans, R. Unpacking the black box: How to promote citizen engagement through government social media during the COVID-19 crisis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 110, 106380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. Citizen Engagement. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/citizen-engagement (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Ekman, J.; Amnå, E. Political participation and civic engagement: Towards a new typology. Hum. Aff. 2012, 22, 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnhout, E.; Metze, T.; Wyborn, C.; Klenk, N.; Louder, E. The politics of co-production: Participation, power, and transformation. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 42, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieven, C.; Lüders, B.; Kulus, D.; Thoneick, R. Enabling Digital Co-creation in Urban Planning and Development. Hum. Centred Intell. Syst. 2021, 189, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, V. Co-production and collaboration in planning—The difference. Plan. Theory Pract. 2014, 15, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, J.; Painter, G. From Citizen Control to Co-Production. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2019, 85, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babelon, I.; Pánek, J.; Falco, E.; Kleinhans, R.; Charlton, J. Between Consultation and Collaboration: Self-Reported Objectives for 25 Web-Based Geoparticipation Projects in Urban Planning. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haltofová, B. Critical success factors of geocrowdsourcing use in e-government: A case study from the Czech Republic. Urban Res. Pract. 2020, 13, 434–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akers, M.A.A. Digital Placemaking: An Analysis of Citizen Participation in Smart Cities. In Smart Cities and Smart Communities; Patnaik, S., Sen, S., Ghosh, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 171–185. ISBN 978-981-19-1145-3. [Google Scholar]

- See, L.; Mooney, P.; Foody, G.; Bastin, L.; Comber, A.; Estima, J.; Fritz, S.; Kerle, N.; Jiang, B.; Laakso, M.; et al. Crowdsourcing, Citizen Science or Volunteered Geographic Information? The Current State of Crowdsourced Geographic Information. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2016, 5, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falco, E.; Kleinhans, R. Digital Participatory Platforms for Co-Production in Urban Development. Int. J. E-Plan. Res. 2018, 7, 52–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, P.; Forss, K.; Czepkiewicz, M.; Saarikoski, H.; Kahila, M. Assessing impacts of PPGIS on urban land use planning: Evidence from Finland and Poland. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2022, 30, 1529–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzalan, N.; Muller, B. Online Participatory Technologies: Opportunities and Challenges for Enriching Participatory Planning. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2018, 84, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babelon, I.; Ståhle, A.; Balfors, B. Toward Cyborg PPGIS: Exploring socio-technical requirements for the use of web-based PPGIS in two municipal planning cases, Stockholm region, Sweden. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2017, 60, 1366–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Kyttä, M.; Reed, P. Using community surveys with participatory mapping to monitor comprehensive plan implementation. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 218, 104306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geertman, S.; Stillwell, J. Handbook of Planning Support Science; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, UK, 2020; ISBN 9781788971089. [Google Scholar]

- Kahila-Tani, M.; Kytta, M.; Geertman, S. Does mapping improve public participation? Exploring the pros and cons of using public participation GIS in urban planning practices. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 186, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzeszewski, M.; Kotus, J. Usability and usefulness of internet mapping platforms in participatory spatial planning. Appl. Geogr. 2019, 103, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, E. Would the Internet Widen Public Participation? Master’s Thesis, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Atzmanstorfer, K.; Blaschke, T. The Geospatial Web. In Citizen E-Participation in Urban Governance: Crowdsourcing and Collaborative Creativity; Silva, C.N., Ed.; Information Science Reference: Hershey, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 144–171. ISBN 9781466641693. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, S. The Future of Participatory Approaches Using Geographic Information: Developing a research agenda for the 21st Century. In Proceedings of the ESF-NSF Meeting on Access and Participatory Approaches in Using Geographic Information, Spoleto, Italy, 5–9 December 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ertiö, T.-P. Participatory Apps for Urban Planning—Space for Improvement. Plan. Pract. Res. 2015, 30, 303–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, B.; Johns, R.; Fernandez, A. The role of crowdsourced data, participatory decision-making and mapping of flood related events. Appl. Geogr. 2021, 128, 102393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US National Center for State Courts. Options for Engagement. Available online: https://www.ncsc.org/consulting-and-research/areas-of-expertise/communications,-civics-and-disinformation/community-engagement/toolkit/step-2-engage/step-2a-choose-your-engagement-methods/options-for-engagement2 (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Falco, E. Digital Community Planning. In Smart Cities and Smart Spaces: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; Management Association, I.R., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 1490–1514. ISBN 9781522570301. [Google Scholar]

- Steiniger, S.; Poorazizi, M.E.; Hunter, A.J.S. Planning with Citizens: Implementation of an e-Planning Platform and Analysis of Research Needs. Urban Plan. 2016, 1, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Filippi, F.; Coscia, C.; Cocina, G.G.; Lazzari, G.; Manzo, S. Digital Participatory Platforms for Civic Engagement: A New Way of Participating in Society? Int. J. Urban Plan. Smart Cities 2020, 1, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinhans, R.; Falco, E.; Babelon, I. Conditions for networked co-production through digital participatory platforms in urban planning. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2022, 30, 769–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minde, J.M.; Gerlak, A.K.; Colella, T.; Murveit, A.M. Re-examining Geospatial Online Participatory Tools for Environmental Planning. Environ. Manag. 2024, 73, 1276–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, T.R.; Pozzebon, M.; Cunha, M.A. Citizens influencing public policy-making: Resourcing as source of relational power in e-participation platforms. Inf. Syst. J. 2022, 32, 344–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, S.-K. A Review of Introducing Game Elements to e-Participation. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference for E-Democracy and Open Government (CeDEM), Krems, Austria, 18–20 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S.; Mossberger, K.; Swindell, D.; Selby, J.D. Experimenting with Public Engagement Platforms in Local Government. Urban Aff. Rev. 2021, 57, 763–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, L. Governments Should Play Games. Simul. Gaming 2017, 48, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluto-Kossakowska, J.; Fijałkowska, A.; Denis, M.; Jaroszewicz, J.; Krzysztofowicz, S. Dashboard as a Platform for Community Engagement in a City Development—A Review of Techniques, Tools and Methods. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, S.; Hanna, J.; Oakley, I.; Vieira, T.; Abreu, F.; Campos, P.; Citizen, X. Proceedings of the 11th Biannual Conference of the Italian SIGCHI Chapter; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Falco, E.; Kleinhans, R. Beyond technology: Identifying local government challenges for using digital platforms for citizen engagement. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 40, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzmanstorfer, K.; Eitzinger, A.; Marin, B.E.; Parra Arteaga, A.; Gonzalez Quintero, B.; Resl, R. HCI-Evaluation of the GeoCitizen-reporting App for citizen participation in spatial planning and community management among members of marginalized communities in Cali, Colombia. GI Forum 2016, 4, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottwald, S.; Laatikainen, T.E.; Kyttä, M. Exploring the usability of PPGIS among older adults: Challenges and opportunities. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2016, 30, 2321–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartling, M.; Resch, B.; Trösterer, S.; Eitzinger, A. Evaluating PPGIS Usability in a Multi-National Field Study Combining Qualitative Surveys and Eye-Tracking. Cartogr. J. 2021, 58, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denwood, T.; Huck, J.J.; Lindley, S. Effective PPGIS in spatial decision-making: Reflecting participant priorities by illustrating the implications of their choices. Trans. Gis 2022, 26, 867–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, K.; Kühnberger, P. 10 Punkte für das Erfolgreiche Durchführen von e-Partizipationsprojekten. Available online: www.neuundkuehn.at (accessed on 11 December 2022).

- Nurminen, V. The Influence of Participatory Mapping on Urban Planning. Master’s Thesis, University of Aalto, Helsinki, Finland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski, P.; Czepkiewicz, M.; Młodkowski, M.; Zwoliński, Z.; Wójcicki, M. Evaluating the scalability of public participation in urban land use planning: A comparison of Geoweb methods with face-to-face meetings. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2019, 46, 511–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Kyttä, M. Key issues and priorities in participatory mapping: Toward integration or increased specialization? Appl. Geogr. 2018, 95, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pánek, J. From Mental Maps to GeoParticipation. Cartogr. J. 2016, 53, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartocci, L.; Grossi, G.; Mauro, S.G.; Ebdon, C. The journey of participatory budgeting: A systematic literature review and future research directions. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2023, 89, 757–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iasulaitis, S.; Nebot, C.P.; Da Silva, E.C.; Sampaio, R.C. Interactivity and policy cycle within Electronic Participatory Budgeting: A comparative analysis. Rev. Adm. Pública 2019, 53, 1091–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gün, A.; Demir, Y.; Pak, B. Urban design empowerment through ICT-based platforms in Europe. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2020, 24, 189–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowmya, J.; Pyarali, H.S. The Effective Use of Crowdsourcing in E-Governance. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287754352_The_effective_use_of_crowdsourcing_in_e-governance (accessed on 5 December 2023).

- Xin, G.; Esembe, E.E.; Chen, J. The mixed effects of e-participation on the dynamic of trust in government: Evidence from Cameroon. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2023, 82, 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, M.; Gigler, B.-S.; Young, G. The Role of Crowdsourcing for Better Governance in Fragile State Contexts. In Closing the Feedback Loop: Can Technology Bridge the Accountability Gap? Gigler, B.-S., Bailur, S., Eds.; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 107–148. ISBN 978-1-4648-0191-4. [Google Scholar]

- Atzmanstorfer, K.; Bartling, M.; Zurita Arthos, L.; Grubinger-Preiner, J.; Feil, C.; Eitzinger, A. Making Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Participatory and Locally Visible—A Prototype Solution. 2023. Available online: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202311.1105/v1 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Kim, E.; Yang, S. Internet literacy and digital natives’ civic engagement: Internet skill literacy or Internet information literacy? J. Youth Stud. 2016, 19, 438–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deitz, M.; Notley, T.; Catanzaro, M.; Third, A.; Sandbach, K. Emotion mapping: Using participatory media to support young people’s participation in urban design. Emot. Space Soc. 2018, 28, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabham, D.C. Crowdsourcing as a Model for Problem Solving. Convergence 2008, 14, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, J.; Kocsis, D.; Tripathi, A.; Tarrell, A.; Weerakoon, A.; Tahmasbi, N.; Xiong, J.; Deng, W.; Oh, O.; de Vreede, G.-J. Conceptual Foundations of Crowdsourcing: A Review of IS Research. In Proceedings of the 2013 46th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Wailea, HI, USA, 7–10 January 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Akmentina, L. E-participation and engagement in urban planning: Experiences from the Baltic cities. Urban Res. Pract. 2023, 16, 624–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P.; Mostafavi, A. Challenges and Opportunities of Crowdsourcing and Participatory Planning in Developing Infrastructure Systems of Smart Cities. Infrastructures 2018, 3, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilola, S.; Käyhkö, N.; Fagerholm, N. Lessons learned from participatory land use planning with high-resolution remote sensing images in Tanzania: Practitioners’ and participants’ perspectives. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pánek, J. Mapping citizens’ emotions: Participatory planning support system in Olomouc, Czech Republic. J. Maps 2019, 15, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartling, M.; Robinson, A.C.; Resch, B.; Eitzinger, A.; Atzmanstorfer, K. The role of user context in the design of mobile map applications. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2021, 48, 432–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, M.A.; Li, S. Usability evaluation of collaborative PPGIS-GeoCWMI for supporting public participation during municipal planning and management services. Appl. Geomat. 2015, 7, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, L. The Evolution and Definition of Geospatial Literacy. In GIScience Teaching and Learning Perspectives; Balram, S., Boxall, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 9–36. ISBN 978-3-030-06057-2. [Google Scholar]

- Haklay, M. Neogeography and the Delusion of Democratisation. Environ. Plan A 2013, 45, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, M.H.; Antoniou, V.; Basiouka, S.; Soden, R.; .Mooney, P. Crowdsourced Geographic Information Use in Government; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Senaratne, H.; Mobasheri, A.; Ali, A.L.; Capineri, C.; Haklay, M. A review of volunteered geographic information quality assessment methods. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2017, 31, 139–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, D.; Dimitrijević, B. Frameworks for citizens participation in planning: From conversational to smart tools. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 48, 101550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, S.; van de Ven, F.H.M.; Blind, M.W.; Slinger, J.H. Planning support tools and their effects in participatory urban adaptation workshops. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 207, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, R. Management information crisis. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1961, 39, 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Bullen, C.; Rockart, J. A Primer on Critical Success Factors; No. 69. 1981. Available online: https://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/1988/SWP-1220-08368993-CISR-069.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Leidecker, J.; Bruno, A. Identifying and using critical success factors. Long Range Plan. 1984, 17, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panopoulou, E.; Tambouris, E.; Tarabanis, K. Success factors in designing eParticipation initiatives. Inf. Organ. 2014, 24, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartling, M.; Resch, B.; Eitzinger, A.; Zurita, L. A Multi-National Human–Computer Interaction Evaluation of the Public Participatory GIS GeoCitizen. GI Forum 2019, 1, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waugaman, A. Implementing the Principles for Digital Development. 2016. Available online: https://bloodwater.org/content/uploads/2023/10/From_Principle_to_Practice_v5-compressed.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Eitzinger, A.; Cock, J.; Atzmanstorfer, K.; Binder, C.; Läderach, P.; Bonilla-Findji, O.; Bartling, M.; Mwongera, C.; Zurita, L.; Jarvis, A. GeoFarmer: A monitoring and feedback system for agricultural development projects. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 158, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eitzinger, A.; Bartling, M.; Bonilla-Findji, O.; Andrieu, N.; Jarvis, A.; Feil, C. GeoFarmer App—A Tool to Complement Extension Services and Foster Active Farmers’ Participation and Knowledge Exchange. 2020. Available online: https://agritrop.cirad.fr/598527/1/Infonote%20Geofarmer.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Bartling, M.; Robinson, A.; Achicanoy Estrella, H.; Eitzinger, A. The impact of user characteristics of smallholder farmers on user experiences with collaborative map applications. PloS ONE 2022, 17, e0264426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlish, C.P.; Pharris, M.D. Community-Based Collaborative Action Research: A Nursing Approach; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Sudbury, MA, USA, 2012; ISBN 9780763771126. [Google Scholar]

- Ledwith, M. (Ed.) Participatory Practice; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2022; ISBN 9781447365495. [Google Scholar]

- WBGU. World in Transition: A Social Contract for Sustainability; WBGU: Berlin, Germany, 2011; ISBN 9783936191370. [Google Scholar]

| Levels | Sub-Levels |

|---|---|

| Information sharing | Informing: One-way communication (‘broadcasting’) from government to citizens. Consulting: One-way communication from citizens to governments. |

| Interaction | Two-way communication with dialogue and feedback between citizens and government representatives. |

| Co-production | The public sector and citizens making better use of each other‘s assets and resources to achieve better outcomes and improved efficiency. |

| Self-organization | Public matters: Citizens create solutions independently that are to be recognized, facilitated or adopted by governments and require some government action. Private matters: Citizens share information and self-organize for matters of private interest that may develop into public demands requiring some government action. |

| Critical Success Factors | Critical Success Subfactors |

|---|---|

| Motive Alignment of the crowd | Long-term objectives |

| Kick-starting the crowd | |

| Vision and Strategy | Vision of the initiative |

| Explicitly defined tasks | |

| Human Capital | Digital skills |

| Technical expertise and vision to put an initiative into practice | |

| Positive previous user experience | |

| Platform design | |

| Usability and user experience | |

| Intuitiveness, cognitive platform | |

| Clearly defined usage rules | |

| Predefined topics of contributions | |

| Citizen-Centric Approach | Channel mix (smartphone and web) |

| Linkage and Trust | Marketing and outreach |

| Security and Privacy | User anonymity |

| Data privacy and data ownership | |

| Sharing level of user contributions | |

| Technical Infrastructure | Inter-operability |

| Data Quality | Localization accuracy |

| Management | Process set-up and platform management |

| Alternative methods of analogous participation | |

| Interaction Orientation | Feedback on user activities |

| Implementation of solutions | |

| Improving platform functionality based on citizens’ suggestions | |

| Social Networking | Strengthening social networks |

| Customization/Personalization | Personal customization |

| Institutional and social customization | |

| User-added Value | Integration of social media |

| Reward for Participation | Social recognition |

| Financial Capital | Free of cost use |

| License fees | |

| External Environment | Governance support |

| Legal framework | |

| Political trust |

| Critical Success Factors | Critical Success Subfactors | Additional Indicators 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Human Capital | Usability and user experience Platform design | Low-threshold platform access (e.g., registering new users, user log-in, etc.); technical expertise of platform operators in municipalities; bug-free platforms for smooth user experience |

| Financial Capital | Free of cost use | |

| Linkage and Trust | Marketing and outreach | Personal stakeholder communication engaging key community figures (e.g., mayors, community activists, members of community associations, etc.); integration of platforms into the municipality website; reference to best-practice cases in other communities that use the same platform |

| Citizen-Centric Approach | Channel mix (smartphone/web) | |

| Security and Privacy | Data privacy and data ownership | |

| External Environment | Legal framework | Ensuring stable political support from all representatives in the municipal council (governance support); using a platform within existing decision-making structures to ensure access to the necessary legal and organizational frameworks and financial resources necessary to implement community projects |

| Process Management | Alternative analogous participation Process set-up and platform management | Platforms as complement to well-established analogous participatory processes especially for small and straightforward community projects with a less challenging level of process management; time-constraints of platform operators within municipalities; efficient information flow through balanced use of notifications (avoiding ‘information overkill’); supporting process managers in setting up valid questions for community surveys |

| Vision and Strategy | Explicitly defined tasks | Clearly define aims and limitations of a community process to avoid creating exaggerated expectations among citizens (particularly regarding legal, organizational, and financial constraints) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Atzmanstorfer, K.; Bartling, M.; Haltofová, B.; Zurita-Arthos, L.; Grubinger-Preiner, J.; Eitzinger, A. Critical Success Factors of Participatory Community Planning with Geospatial Digital Participatory Platforms. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14040153

Atzmanstorfer K, Bartling M, Haltofová B, Zurita-Arthos L, Grubinger-Preiner J, Eitzinger A. Critical Success Factors of Participatory Community Planning with Geospatial Digital Participatory Platforms. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2025; 14(4):153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14040153

Chicago/Turabian StyleAtzmanstorfer, Karl, Mona Bartling, Barbora Haltofová, Leo Zurita-Arthos, Judith Grubinger-Preiner, and Anton Eitzinger. 2025. "Critical Success Factors of Participatory Community Planning with Geospatial Digital Participatory Platforms" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 14, no. 4: 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14040153

APA StyleAtzmanstorfer, K., Bartling, M., Haltofová, B., Zurita-Arthos, L., Grubinger-Preiner, J., & Eitzinger, A. (2025). Critical Success Factors of Participatory Community Planning with Geospatial Digital Participatory Platforms. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 14(4), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14040153