Mapping the Spatiotemporal Urban Footprint of Residents and Tourists: A Data-Driven Approach Based on User-Generated Reviews

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. General Overview

1.2. Literature Review

2. Materials and Methods

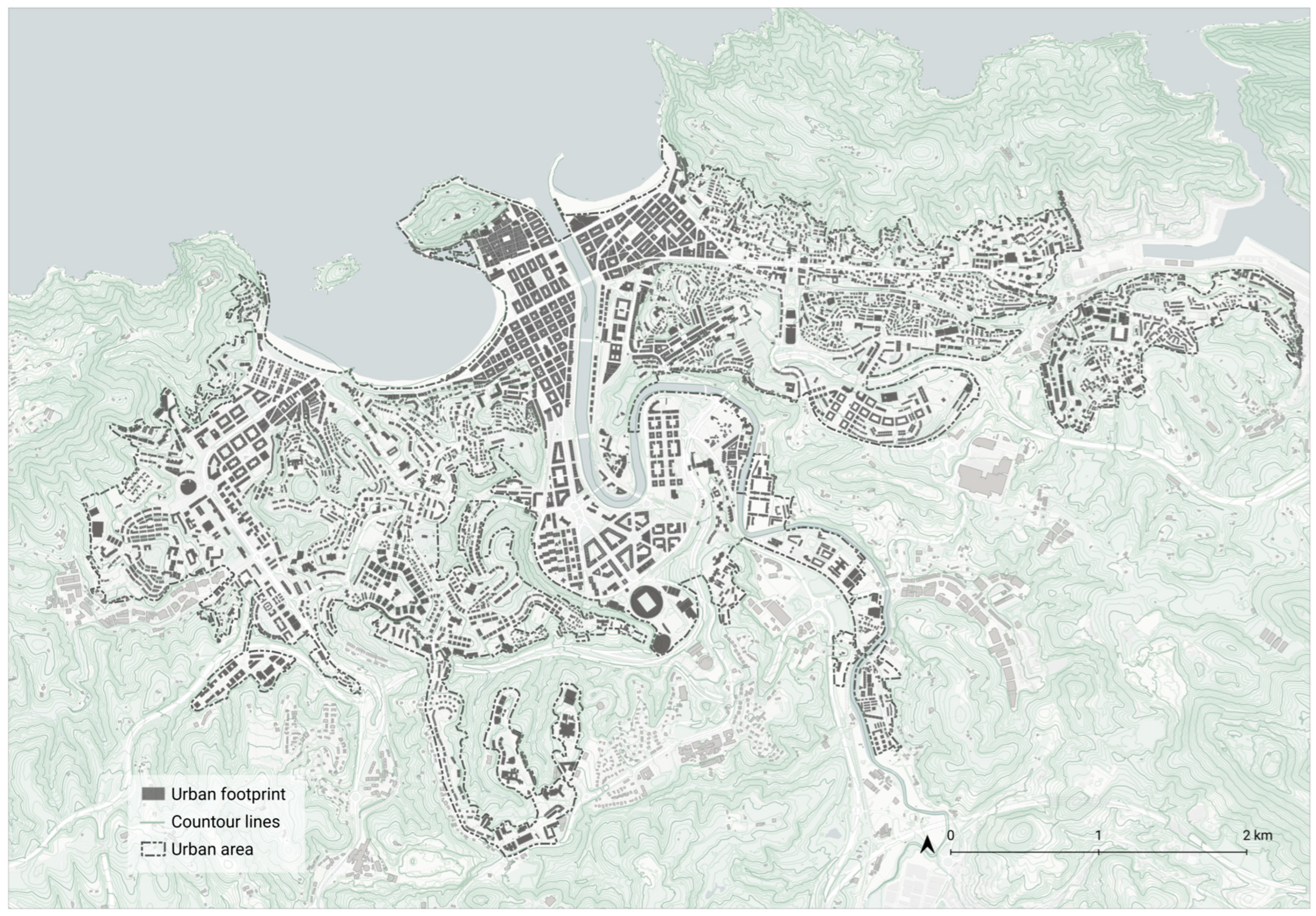

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methodology and Data

- Data CollectionThe use of user-generated reviews from Google Maps allows for high spatial and temporal granularity, enabling the detection of fine-scale behavioral patterns that are often missed in traditional survey-based or administrative datasets.

- -

- POIs:Data were collected in December 2023 using the crawler-google-maps tool [47], which systematically extracted all 7.559 POIs located within the functional urban area of the selected municipality. For each POI, information on coordinates and all associated public user reviews was obtained. Each of the 949.461 reviews included the publication date, the public profile identifier, and the total number of reviews posted by that user.

- -

- User Profile Review Web Scraping:A second phase, conducted between February and April 2024, involved scraping a sample of individual Google Maps profiles, identified from the previous dataset. To ensure the inclusion of both locals and visitors, user IDs were selected according to two criteria: (i) high review activity globally (top users by total reviews), and (ii) frequent reviewers within the city of study (IDs most commonly appearing in the POIs dataset). From each accessible profile, the full history of publicly shared reviews was extracted, including the name of the reviewed POI and its address, amounting to 10.955.805 reviews in total.

- User Origin ClassificationThe classification of users by origin based on their review history provides a more nuanced segmentation than conventional stay-duration thresholds, allowing for the identification of proximity-based behavioral gradients. This approach is particularly relevant in tourism-intensive cities, where visitor profiles are highly heterogeneous.

- -

- Geolocation of Reviews and Dominant Location Detection:Each review address was processed using the Python (v3.11.1) package pandas, Power Query and an automatic pattern detection add-in in Excel [48] to extract the corresponding region, either as a country (for international users) or province (for domestic users).A “standard address” in Google Maps usually follows an envelope order format, including street number, street name, postal code, city, and province or country, which enables automated parsing for the majority of entries. While exact formats vary by country, some contexts (e.g., Russia, Japan, China) required additional manual inspection when automated procedures failed. An Excel add-in was employed to detect postal codes in non-standardized addresses and support their classification. Furthermore, unique locations were extracted to harmonize nomenclatures across language variants (e.g., ‘Donostia’ and ‘San Sebastián’).Based on the most frequently reviewed region per profile, the user’s likely place of origin was assigned. Users whose dominant location matched the study municipality were labeled as residents, while those from outside were labeled as visitors. The latter were further characterized with greater precision based on their spatial relationship to the municipality, distinguishing them as:

- ○

- Provincial: users whose dominant activity was located within the same province as the study area.

- ○

- Regional: users primarily active in neighboring provinces that share a border with the study province.

- ○

- Domestic: users from other provinces within the same country, excluding the study province and its immediate neighbors.

- ○

- International: users whose dominant activity occurred in countries outside the national territory.

- -

- Handling Not Sampled and Private Profiles:For users without available review histories, we implemented a temporal proxy approach. The length of stay was defined as the elapsed time between a user’s first and last recorded review within the study area, rather than continuous residence or presence. Thresholds were derived empirically from the distribution of previously classified tourists and residents, showing that stays longer than one year were predominantly associated with residents, whereas stays shorter than one month were characteristic of tourists. These thresholds, consistent with prior literature, were then applied to assign the remaining users to one of three categories—locals, tourists, or unknown—depending on whether the temporal patterns aligned clearly with either group or remained ambiguous.

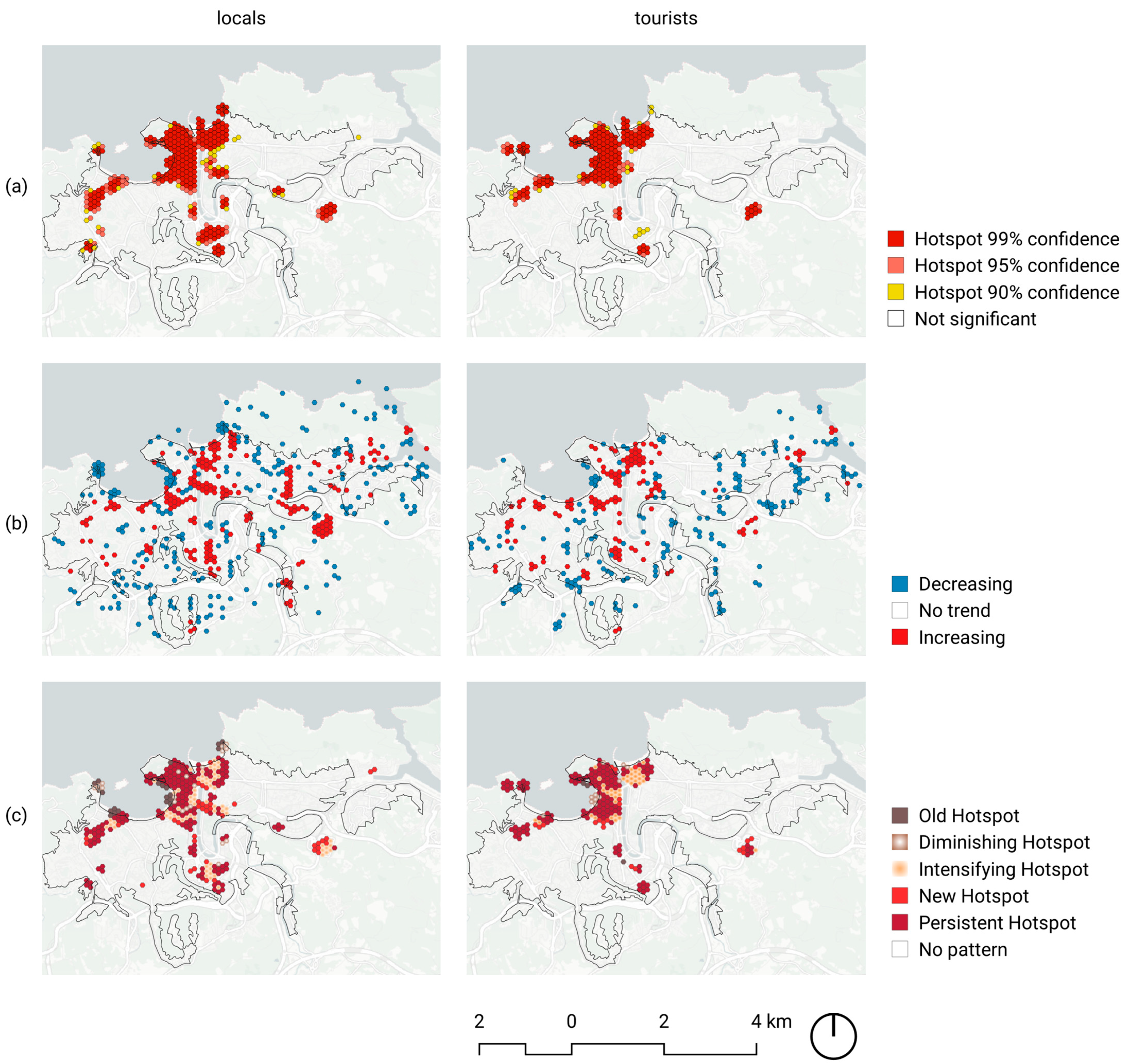

- Spatiotemporal AnalysisThe adoption of hexagonal spatial aggregation enhances spatial comparability and reduces edge effects compared to square grids or administrative boundaries. Furthermore, the combination of Getis-Ord Gi* and Mann-Kendall tests enables the identification of statistically significant spatial clusters and their temporal evolution, offering interpretability, scalability, and compatibility with open-source tools, ensuring both analytical rigor and methodological transparency.

- -

- Aggregation in Hexagonal Grid Cells:All reviews were spatially aggregated using a uniform hexagonal grid overlaying the urban area, with both horizontal and vertical spacing set to 100 m. This resolution is consistent with applications in dense urban environments and reflects the fine-grained structure of POIs relevant to the case study. Each cell contains the count of unique users and reviews classified by user origin.

- -

- Hotspot and Trend Detection:To detect statistically significant spatial concentrations of activity, the Getis-Ord Gi* statistic was applied to the count of reviews aggregated per hexagonal cell using the Hotspot Analysis plugin in QGIS (v3.16.7), using queen contiguity to define spatial relationships among neighboring units. This identified hotspots of tourist and local activity. Additionally, the Mann-Kendall trend test was used on yearly disaggregated cell data using the Python (v3.11.1) package pymannkendall, in order to detect positive or negative trends over time. The combination of both methods allowed for the identification and characterization of the spatiotemporal evolution of hotspots, including old, persistent, new, intensifying and diminishing clusters.

- -

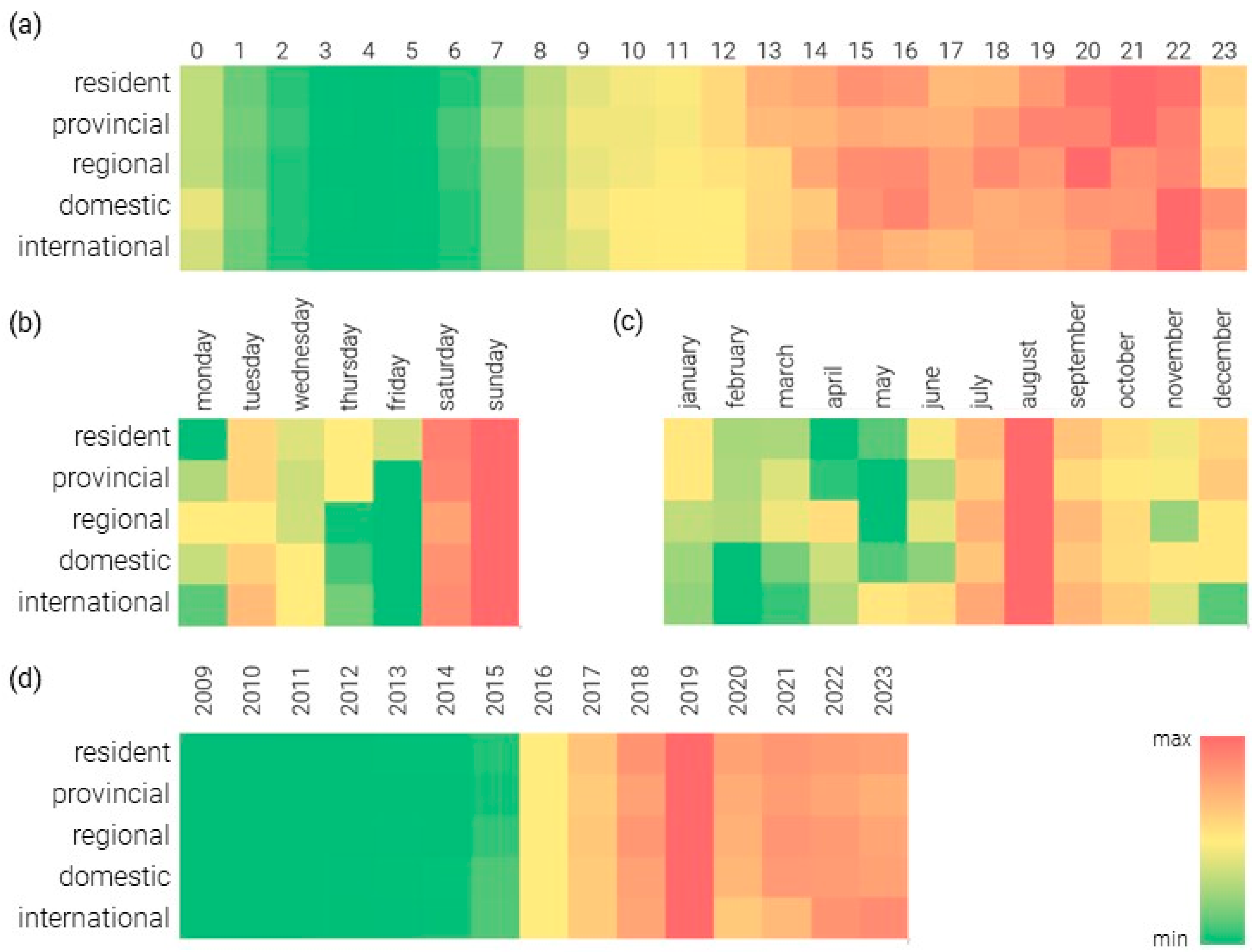

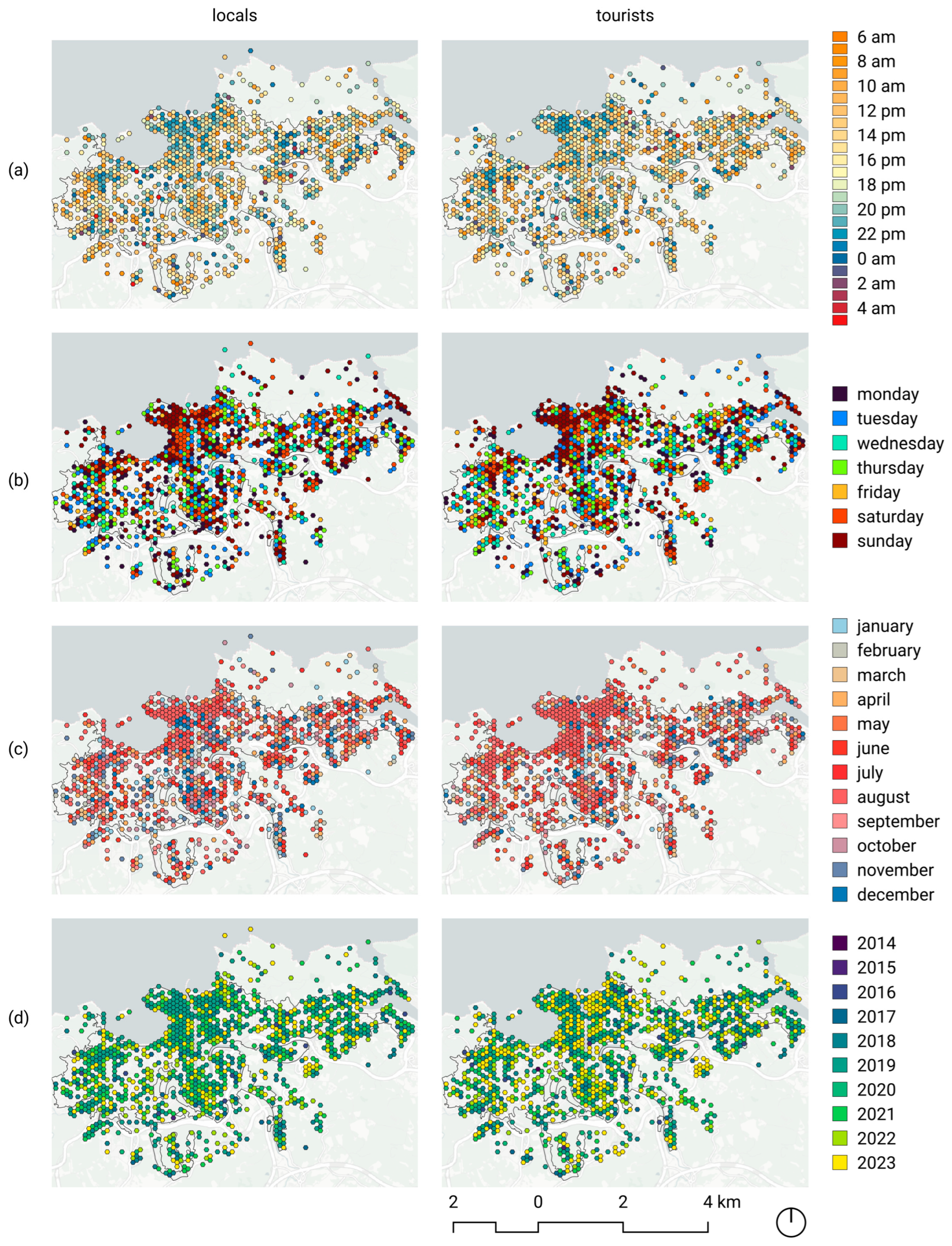

- Temporal Usage Characterization:For each grid cell, additional temporal metrics were computed to capture the nature of activity. These included predominant time of use: the hour, day of week, month and year with the highest review activity, computed separately for tourists and residents.

3. Results

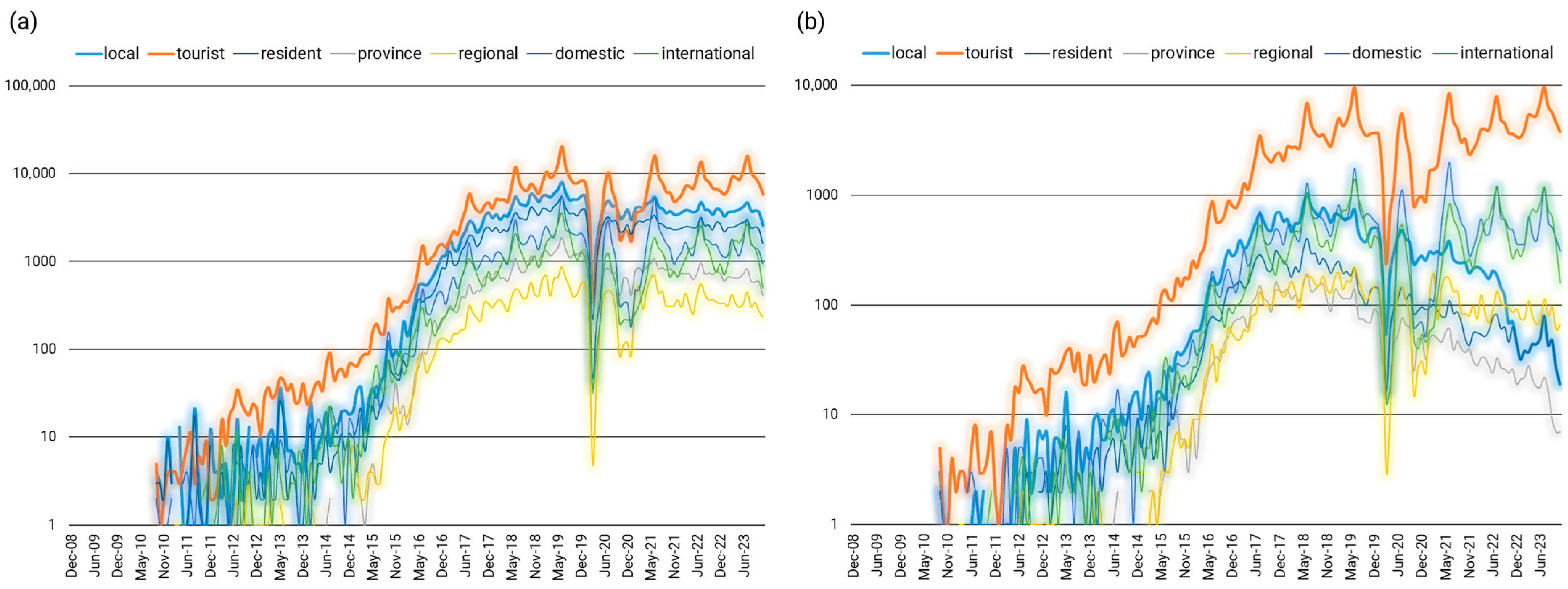

3.1. Spatial Distribution and General Temporal Patterns

3.1.1. Identification and Cross-Validation

3.1.2. Temporal Patterns

3.1.3. Spatial Distribution

3.2. Spatiotemporal Clustering and Trends

3.3. Diversity of Urban Use

- -

- Hourly Patterns

- -

- Weekly Patterns

- -

- Seasonal Patterns

- -

- Annual Trends

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| POI | Point of interest |

| UGC | User-generated content |

| GIS | Geographic information system |

| VGI | Volunteered geographic information |

References

- Pearce, D.G. Towards a geography of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1979, 6, 245–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.P. Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Tourist Behaviour. Reg. Stud. 1981, 15, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Lew, A.A. Tourist Flows and the Spatial Distribution of Tourists. In A Companion to Tourism; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Martín, R.; Simancas-Cruz, M.R.; González-Yanes, J.A.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, Y.; García-Cruz, J.I.; González-Mora, Y.M. Identifying micro-destinations and providing statistical information: A pilot study in the Canary Islands. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 771–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snepenger, D.J.; Murphy, L.; O’Connell, R.; Gregg, E. Tourists and residents use of a shopping space. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.L.; Chu, C.M.; Tsai, C.H.; Chen, C.C.; Chen, C.Y. Geovisualization of tourist activity travel patterns using 3D GIS: An empirical study of Tamsui, Taiwan. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2009, 36, 12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kwan, M.P. GIS methods in time-geographic research: Geocomputation and geovisualization of human activity patterns. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B 2004, 86, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardin, F.; Dal Fiore, F.; Ratti, C.; Blat, J. Leveraging explicitly disclosed location information to understand tourist dynamics: A case study. J. Locat. Based Serv. 2008, 2, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önder, I.; Koerbitz, W.; Hubmann-Haidvogel, A. Tracing Tourists by Their Digital Footprints: The Case of Austria. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirksmeier, P.; Helbrecht, I. Resident Perceptions of New Urban Tourism: A Neglected Geography of Prejudice. Geogr. Compass 2015, 9, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.H.; Yen, C.H.; Teng, H.Y. Tourist–resident conflict: A scale development and empirical study. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 10, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinberger, A.Y.; Shoval, N. Spatiotemporal Contingencies in Tourists’ Intradiurnal Mobility Patterns. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 512–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaire, J.A.; Camprubí, R.; Galí, N. Tourist clusters from Flickr travel photography. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 11, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Chen, Y.; Li, C. Discovering the tourists’ behaviors and perceptions in a tourism destination by analyzing photos’ visual content with a computer deep learning model: The case of Beijing. Tour. Manag. 2019, 75, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höpken, W.; Müller, M.; Fuchs, M.; Lexhagen, M. Flickr data for analysing tourists’ spatial behaviour and movement patterns: A comparison of clustering techniques. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2020, 11, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Li, Z.; Yang, C.; Jiang, Y. A graph-based approach to detecting tourist movement patterns using social media data. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2019, 46, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnat, M.M.; Hasan, S. Identifying tourists and analyzing spatial patterns of their destinations from location-based social media data. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2018, 96, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Spierings, B.; Dijst, M.; Tong, Z. Analysing trends in the spatio-temporal behaviour patterns of mainland Chinese tourists and residents in Hong Kong based on Weibo data. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1542–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiras, A.; Eusébio, C. Perceived image of accessible tourism destinations: A data mining analysis of Google Maps reviews. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 2584–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Wankhede, V.A.; Kumar, A.; Luthra, S.; Huisingh, D. Big data analytics and sustainable tourism: A comprehensive review and network based analysis for potential future research. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2022, 2, 100122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.P.G.; Silva, T.H.; Loureiro, A.A.F. Uncovering spatiotemporal and semantic aspects of tourists mobility using social sensing. Comput. Commun. 2020, 160, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisu, A.A.; Syabri, I.; Andani, I.G.A. How do young people move around in urban spaces?: Exploring trip patterns of generation-Z in urban areas by examining travel histories on Google Maps Timeline. Travel Behav. Soc. 2024, 34, 100686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.; Griffin, T. Understanding tourists’ spatial behaviour: GPS tracking as an aid to sustainable destination management. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 580–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Olmedo, M.H.; Moya-Gómez, B.; García-Palomares, J.C.; Gutiérrez, J. Tourists’ digital footprint in cities: Comparing Big Data sources. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Palomares, J.C.; Gutiérrez, J.; Mínguez, C. Identification of tourist hot spots based on social networks: A comparative analysis of European metropolises using photo-sharing services and GIS. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 63, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.Q.; Li, G.; Law, R.; Ye, B.H. Exploring the travel behaviors of inbound tourists to Hong Kong using geotagged photos. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zheng, W.; Ge, P. Tourism demand forecasting with spatiotemporal features. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 94, 103384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, L.; Tang, L.; Wang, S.; Li, L. Big data in tourism research: A literature review. Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 301–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, S.J.; Vu, H.Q.; Gammack, J.; McGrath, M. A Big Data Analytics Method for Tourist Behaviour Analysis. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Tsou, M.H. Mapping spatiotemporal tourist behaviors and hotspots through location-based photo-sharing service (Flickr) data. In Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Zhang, Y. The effect of distance on tourist behavior: A study based on social media data. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 82, 102916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.Q.; Li, G.; Law, R.; Zhang, Y. Exploring Tourist Dining Preferences Based on Restaurant Reviews. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhring, M.; Keller, B.; Schmidt, R.; Dacko, S. Google Popular Times: Towards a better understanding of tourist customer patronage behavior. Tour. Rev. 2020, 76, 533–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, A.M.; Kastenholz, E. Spatiotemporal tourist behaviour in urban destinations: A framework of analysis. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 22–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrena-Herrán, M.; Modrego-Monforte, I.; Grijalba, O. Revealing Spatiotemporal Urban Activity Patterns: A Machine Learning Study Using Google Popular Times. ISPRS Int. J. Geoinf. 2025, 14, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikjoo, A.; Bakhshi, H. The presence of tourists and residents in shared travel photos. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Silva, E.A. Understanding temporal and spatial patterns of urban activities across demographic groups through geotagged social media data. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2023, 100, 101934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kádár, B.; Gede, M. Where do tourists go? Visualizing and analysing the spatial distribution of geotagged photography. Cartographica 2013, 48, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Spierings, B.; Hooimeijer, P. Different urban settings affect multi-dimensional tourist-resident interactions. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 24, 815–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhani, D.P.; Alamsyah, A.; Febrianta Mochamad Yudha Damayanti, L.Z.A. Exploring Tourists’ Behavioral Patterns in Bali’s Top-Rated Destinations: Perception and Mobility. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 743–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.; Shin, H.H. Tourists’ Experiences with Smart Tourism Technology at Smart Destinations and Their Behavior Intentions. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 1464–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yang, J.; Liu, X.; Guo, Z. Reinterpreting activity space in tourism by mapping tourist-resident interactions in populated cities. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2024, 49, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Yao, Y.; Li, J. Sociocultural impacts of tourism on residents of world cultural heritage sites in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Aportación Del Turismo a La Economía Vasca Por Año. Valor Absoluto (Miles de Euros) y Porcentaje Sobre El PIB p.m. Precios Corrientes. 2010–2023. 2022. Available online: https://www.eustat.eus/elementos/ele0003400/aportacion-del-turismo-a-la-economia-vasca-por-ano-valor-absoluto-miles-de-euros-y-porcentaje-sobre-el-pib-pm-precios-corrientes/tbl0003417_c.html (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Gobierno Vasco Enfokatur Observatorio Turístico de Euskadi, SIT EUSKADI. Sistema de Inteligencia Turística. 2025. Available online: https://www.euskadi.eus/sit-sistema-de-inteligencia-turistica/web01-a2behtur/es/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Gipuzkoa: Población por Municipios y Sexo. 2021. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=2873 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Drobník, J. Google Maps Scraper. 2019. Available online: https://github.com/drobnikj/crawler-google-places (accessed on 4 May 2022).

- Gulwani, S. Automating string processing in spreadsheets using input-output examples. ACM Sigplan Not. 2011, 46, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encalada-Abarca, L.; Ferreira, C.C.; Rocha, J. Revisiting city tourism in the longer run: An exploratory analysis based on LBSN data. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 584–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, J.; García-Palomares, J.C.; Romanillos, G.; Salas-Olmedo, M.H. The eruption of Airbnb in tourist cities: Comparing spatial patterns of hotels and peer-to-peer accommodation in Barcelona. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, A.M.; Kastenholz, E. Tourists’ spatial behaviour in urban destinations: The effect of prior destination experience. J. Vacat. Mark. 2018, 24, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quattrone, G.; Capra, L.; De Meo, P. There’s no such thing as the perfect map: Quantifying bias in spatial crowd-sourcing datasets. In Proceedings of the CSCW 2015—Proceedings of the 2015 ACM International Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 14–18 March 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raun, J.; Ahas, R.; Tiru, M. Measuring tourism destinations using mobile tracking data. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachyuni, S.S.; Kusumaningrum, D.A. The Effect of COVID-19 Pandemic: How are the Future Tourist Behavior? J. Educ. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2020, 33, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolasco-Cirugeda, A.; García-Mayor, C.; Lupu, C.; Bernabeu-Bautista, A. Scoping out urban areas of tourist interest though geolocated social media data: Bucharest as a case study. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2022, 24, 361–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Cheer, J.M. Overtourism and degrowth: A social movements perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1857–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Feng, C.C.; Huang, W.; Fan, H.; Wang, Y.C.; Zipf, A. Volunteered geographic information research in the first decade: A narrative review of selected journal articles in GIScience. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2020, 34, 1765–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senaratne, H.; Mobasheri, A.; Ali, A.L.; Capineri, C.; Haklay, M. A review of volunteered geographic information quality assessment methods. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2017, 31, 139–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzeszewski, M. Geosocial capta in geographical research–a critical analysis. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2018, 45, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.; De Sabbata, S.; Zook, M.A. Towards a study of information geographies: (im)mutable augmentations and a mapping of the geographies of information. Geo 2015, 2, 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Vega, R.; Waite, K.; O’Gorman, K. Social impact theory: An examination of how immediacy operates as an influence upon social media interaction in Facebook fan pages. Mark. Rev. 2016, 16, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiao, L.; Ye, Y.; Xu, W.; Law, A. Understanding tourist space at a historic site through space syntax analysis: The case of Gulangyu, China. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.Q.; Muskat, B.; Li, G.; Law, R. Improving the resident–tourist relationship in urban hotspots. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 595–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Length of Stay | Residents | Visitors | Unknown |

|---|---|---|---|

| <24 h | 4.7% | 64.8% | 81.3% |

| 1 day–1 week | 1.8% | 7.8% | 2.7% |

| 1 week–1 month | 1.7% | 5.0% | 2.0% |

| 1 month–1 year | 13.4% | 7.3% | 5.7% |

| >1 year | 78.3% | 15.1% | 8.4% |

| Criteria | Type | Users | Reviews |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatially identified users (sample) | resident | 12.255 | 223.872 |

| province | 6.128 | 64.706 | |

| regional | 9.500 | 31.102 | |

| domestic | 45.824 | 129.981 | |

| international | 37.364 | 92.466 | |

| Spatiotemporally identified users * | local | 32.709 | 329.060 |

| tourist | 308.759 | 578.608 | |

| unknown | 13.985 | 42.293 |

| Type | Dominant Area | Peak Hour | Seasonality | Cells Visited (Median) | Post-COVID-19 Evolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resident | Present across most urban areas | 15–16, 20–22 | Persistent | 9 | Stable |

| Provincial | City center, peripheric neighborhoods | 19–22 | Persistent | 6 | Slight decrease |

| Regional | Iconic areas | 14–22 | Easter, Summer, Christmas | 2 | Modest rise |

| Domestic | Old Town, landmarks | 15–16, 20–23 | July–December | 2 | Swift rebound |

| International | Old Town | 21–22 | May–October | 1 | Steady growth |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barrena-Herrán, M.; Modrego-Monforte, I.; Grijalba, O. Mapping the Spatiotemporal Urban Footprint of Residents and Tourists: A Data-Driven Approach Based on User-Generated Reviews. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120456

Barrena-Herrán M, Modrego-Monforte I, Grijalba O. Mapping the Spatiotemporal Urban Footprint of Residents and Tourists: A Data-Driven Approach Based on User-Generated Reviews. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2025; 14(12):456. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120456

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarrena-Herrán, Mikel, Itziar Modrego-Monforte, and Olatz Grijalba. 2025. "Mapping the Spatiotemporal Urban Footprint of Residents and Tourists: A Data-Driven Approach Based on User-Generated Reviews" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 14, no. 12: 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120456

APA StyleBarrena-Herrán, M., Modrego-Monforte, I., & Grijalba, O. (2025). Mapping the Spatiotemporal Urban Footprint of Residents and Tourists: A Data-Driven Approach Based on User-Generated Reviews. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 14(12), 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120456