Cotranslational Folding of Proteins on the Ribosome

Abstract

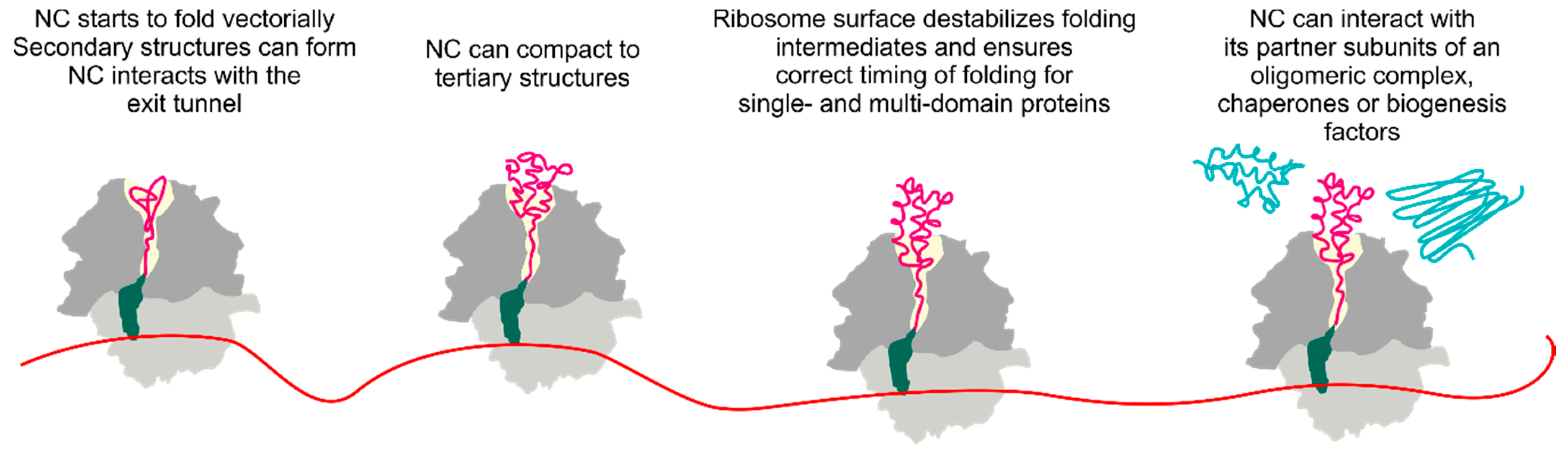

1. Introduction

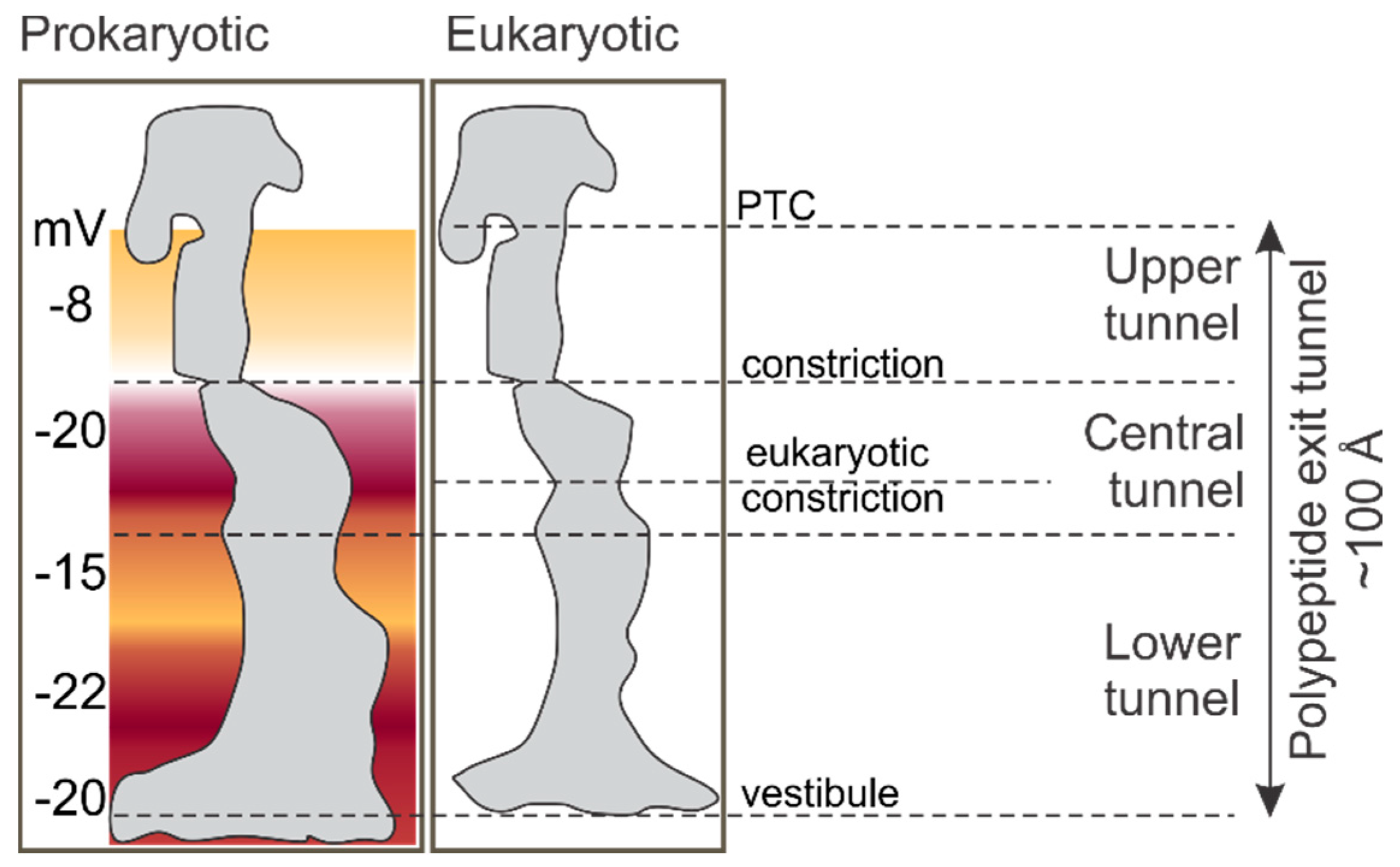

2. The Environment of the Peptide Exit Tunnel

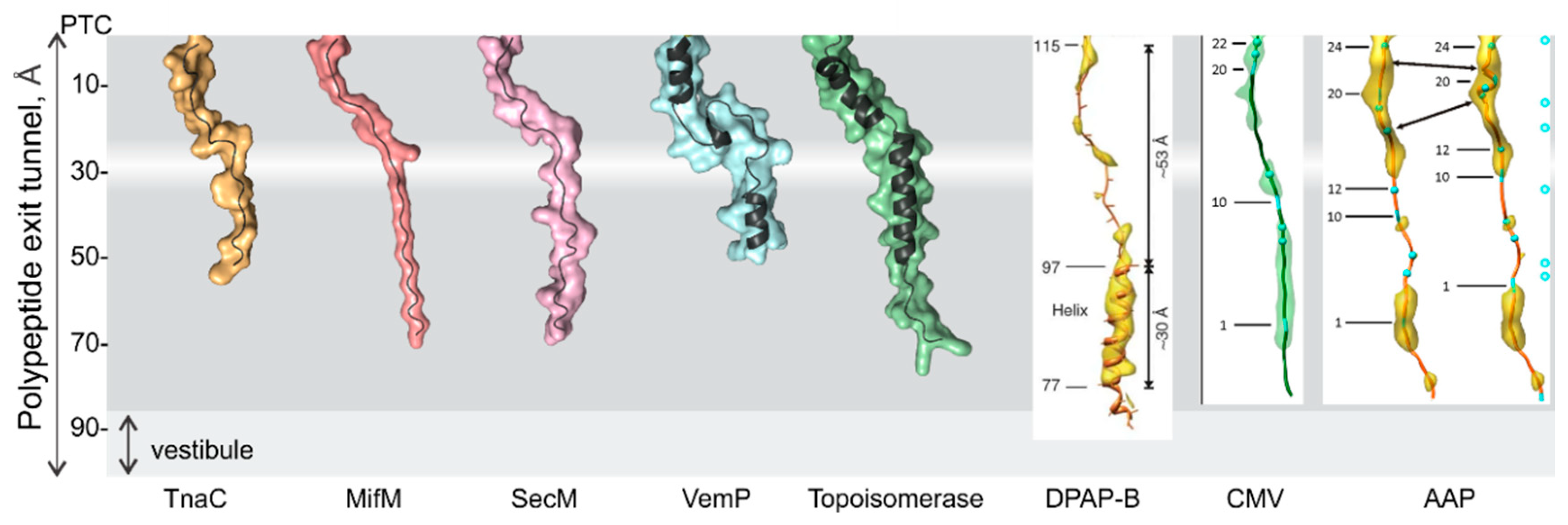

3. Folding inside the Exit Tunnel

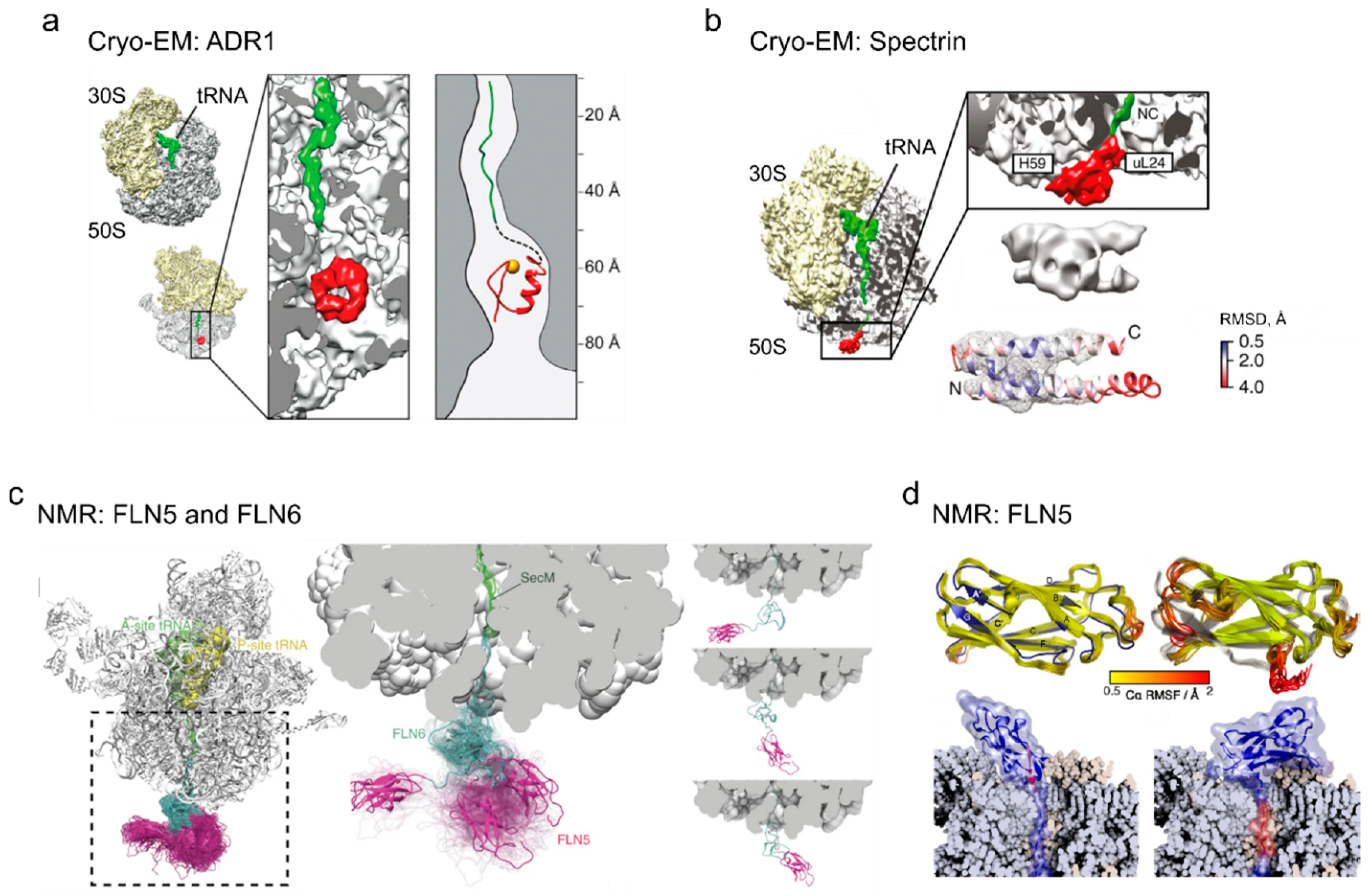

4. Cotranslational Folding of Single Domain Proteins

5. Multidomain Protein Folding

6. The Ribosome Has a Destabilizing Effect on the Nascent Chain

7. Cotranslational Subunits Assembly

8. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hartl, F.U. Protein misfolding diseases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, P.; Park, H.; Baumann, M.; Dunlop, J.; Frydman, J.; Kopito, R.; McCampbell, A.; Leblanc, G.; Venkateswaran, A.; Nurmi, A.; et al. Protein misfolding in neurodegenerative diseases: Implications and strategies. Transl. Neurodegener. 2017, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.B.; Mogk, A.; Bukau, B. Spatially organized aggregation of misfolded proteins as cellular stress defense strategy. J. Mol. Biol. 2015, 427, 1564–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutting, G.R. Cystic fibrosis genetics: From molecular understanding to clinical application. Nat. Rev. Genet 2015, 16, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaton, W.A.; Hofrichter, J. Sickle cell hemoglobin polymerization. Adv. Protein Chem. 1990, 40, 63–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana, A.; Waiswo, M. The genetic and molecular basis of congenital cataract. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2011, 74, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labbadia, J.; Morimoto, R.I. Huntington’s disease: Underlying molecular mechanisms and emerging concepts. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2013, 38, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiou, D.; Aguila, M.; Bellingham, J.; Li, W.; McCulley, C.; Reeves, P.J.; Cheetham, M.E. The molecular and cellular basis of rhodopsin retinitis pigmentosa reveals potential strategies for therapy. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2018, 62, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciryam, P.; Morimoto, R.I.; Vendruscolo, M.; Dobson, C.M.; O’Brien, E.P. In vivo translation rates can substantially delay the cotranslational folding of the Escherichia coli cytosolic proteome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E132–E140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.; Bremer, H. Polypeptide-chain-elongation rate in Escherichia coli B/r as a function of growth rate. Biochem. J. 1976, 160, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostrom, K.; Wettesten, M.; Boren, J.; Bondjers, G.; Wiklund, O.; Olofsson, S.O. Pulse-chase studies of the synthesis and intracellular transport of apolipoprotein B-100 in Hep G2 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1986, 261, 13800–13806. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ingolia, N.T.; Lareau, L.F.; Weissman, J.S. Ribosome profiling of mouse embryonic stem cells reveals the complexity and dynamics of mammalian proteomes. Cell 2011, 147, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbuzynskiy, S.O.; Ivankov, D.N.; Bogatyreva, N.S.; Finkelstein, A.V. Golden triangle for folding rates of globular proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, E.P.; Ciryam, P.; Vendruscolo, M.; Dobson, C.M. Understanding the influence of codon translation rates on cotranslational protein folding. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 1536–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, C.M.; Goldman, D.H.; Chodera, J.D.; Tinoco, I., Jr.; Bustamante, C. The ribosome modulates nascent protein folding. Science 2011, 334, 1723–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, O.B.; Nickson, A.A.; Hollins, J.J.; Wickles, S.; Steward, A.; Beckmann, R.; von Heijne, G.; Clarke, J. Cotranslational folding of spectrin domains via partially structured states. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017, 24, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, P.; Hansen, J.; Ban, N.; Moore, P.B.; Steitz, T.A. The structural basis of ribosome activity in peptide bond synthesis. Science 2000, 289, 920–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, A.; Beck, M. The benefits of cotranslational assembly: A structural perspective. Trends Cell Biol. 2019, 29, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anfinsen, C.B. Principles that govern folding of protein chains. Science 1973, 181, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frydman, J.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Tempst, P.; Hartl, F.U. Co-translational domain folding as the structural basis for the rapid de novo folding of firefly luciferase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1999, 6, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samelson, A.J.; Bolin, E.; Costello, S.M.; Sharma, A.K.; O’Brien, E.P.; Marqusee, S. Kinetic and structural comparison of a protein’s cotranslational folding and refolding pathways. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaas9098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, M.S.; Sander, I.M.; Clark, P.L. Cotranslational folding promotes beta-helix formation and avoids aggregation in vivo. J. Mol. Biol. 2008, 383, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svetlov, M.S.; Kommer, A.; Kolb, V.A.; Spirin, A.S. Effective cotranslational folding of firefly luciferase without chaperones of the Hsp70 family. Protein Sci. 2006, 15, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, V.A.; Makeyev, E.V.; Spirin, A.S. Folding of firefly luciferase during translation in a cell-free System. EMBO J. 1994, 13, 3631–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolb, V.A.; Makeyev, E.V.; Spirin, A.S. Co-translational folding of an eukaryotic multidomain protein in a prokaryotic translation system. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 16597–16601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiber, A.; Doring, K.; Friedrich, U.; Klann, K.; Merker, D.; Zedan, M.; Tippmann, F.; Kramer, G.; Bukau, B. Cotranslational assembly of protein complexes in eukaryotes revealed by ribosome profiling. Nature 2018, 561, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, K.C.; Frydman, J. The stop-and-go traffic regulating protein biogenesis: How translation kinetics controls proteostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 2076–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collart, M.A.; Weiss, B. Ribosome pausing, a dangerous necessity for co-translational events. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, G.; Shiber, A.; Bukau, B. Mechanisms of cotranslational maturation of newly synthesized proteins. Annu Rev. Biochem. 2019, 88, 337–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komar, A.A. A pause for thought along the co-translational folding pathway. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2009, 34, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, N.R.; Gerstein, M.; Steitz, T.A.; Moore, P.B. The geometry of the ribosomal polypeptide exit tunnel. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 360, 893–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmer, M.; Dunham, C.M.; Murphy, F.V.T.; Weixlbaumer, A.; Petry, S.; Kelley, A.C.; Weir, J.R.; Ramakrishnan, V. Structure of the 70S ribosome complexed with mRNA and tRNA. Science 2006, 313, 1935–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuwirth, B.S.; Borovinskaya, M.A.; Hau, C.W.; Zhang, W.; Vila-Sanjurjo, A.; Holton, J.M.; Cate, J.H. Structures of the bacterial ribosome at 3.5 Å resolution. Science 2005, 310, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dao Duc, K.; Batra, S.S.; Bhattacharya, N.; Cate, J.H.D.; Song, Y.S. Differences in the path to exit the ribosome across the three domains of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 4198–4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malkin, L.I.; Rich, A. Partial resistance of nascent polypeptide chains to proteolytic digestion due to ribosomal shielding. J. Mol. Biol. 1967, 26, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blobel, G.; Sabatini, D.D. Controlled proteolysis of nascent polypeptides in rat liver cell fractions. I. Location of the polypeptides within ribosomes. J. Cell Biol. 1970, 45, 130–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtkamp, W.; Kokic, G.; Jager, M.; Mittelstaet, J.; Komar, A.A.; Rodnina, M.V. Cotranslational protein folding on the ribosome monitored in real time. Science 2015, 350, 1104–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Kobertz, W.R.; Deutsch, C. Mapping the electrostatic potential within the ribosomal exit tunnel. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 371, 1378–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucent, D.; Snow, C.D.; Aitken, C.E.; Pande, V.S. Non-bulk-like solvent behavior in the ribosome exit tunnel. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2010, 6, e1000963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolhead, C.A.; McCormick, P.J.; Johnson, A.E. Nascent membrane and secretory proteins differ in FRET-detected folding far inside the ribosome and in their exposure to ribosomal proteins. Cell 2004, 116, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissley, D.A.; O’Brien, E.P. Structural origins of FRET-observed nascent chain compaction on the ribosome. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 9927–9937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farias-Rico, J.A.; Ruud Selin, F.; Myronidi, I.; Fruhauf, M.; von Heijne, G. Effects of protein size, thermodynamic stability, and net charge on cotranslational folding on the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E9280–E9287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudva, R.; Tian, P.; Pardo-Avila, F.; Carroni, M.; Best, R.; Bernstein, H.D.; von Heijne, G. The shape of the ribosome exit tunnel affects cotranslational protein folding. eLife 2018, 7, e36326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charneski, C.A.; Hurst, L.D. Positively charged residues are the major determinants of ribosomal velocity. PLoS Biol. 2013, 11, e1001508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requiao, R.D.; de Souza, H.J.; Rossetto, S.; Domitrovic, T.; Palhano, F.L. Increased ribosome density associated to positively charged residues is evident in ribosome profiling experiments performed in the absence of translation inhibitors. RNA Biol. 2016, 13, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Deutsch, C. Electrostatics in the ribosomal tunnel modulate chain elongation rates. J. Mol. Biol. 2008, 384, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Hubalewska, M.; Ignatova, Z. Transient ribosomal attenuation coordinates protein synthesis and co-translational folding. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009, 16, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhr, F.; Jha, S.; Thommen, M.; Mittelstaet, J.; Kutz, F.; Schwalbe, H.; Rodnina, M.V.; Komar, A.A. Synonymous codons direct cotranslational folding toward different protein conformations. Mol. Cell 2016, 61, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Chiba, S. Arrest peptides: Cis-acting modulators of translation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013, 82, 171–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.N.; Arenz, S.; Beckmann, R. Translation regulation via nascent polypeptide-mediated ribosome stalling. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2016, 37, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, O.B.; Hedman, R.; Marino, J.; Wickles, S.; Bischoff, L.; Johansson, M.; Muller-Lucks, A.; Trovato, F.; Puglisi, J.D.; O’Brien, E.P.; et al. Cotranslational protein folding inside the ribosome exit tunnel. Cell Rep. 2015, 12, 1533–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, D.H.; Kaiser, C.M.; Milin, A.; Righini, M.; Tinoco, I.; Bustamante, C. Mechanical force releases nascent chain-mediated ribosome arrest in vitro and in vivo. Science 2015, 348, 457–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, N.; Hedman, R.; Schiller, N.; von Heijne, G. A biphasic pulling force acts on transmembrane helices during translocon-mediated membrane integration. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012, 19, 1018–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wruck, F.; Katranidis, A.; Nierhaus, K.H.; Buldt, G.; Hegner, M. Translation and folding of single proteins in real time. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E4399–E4407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leininger, S.E.; Trovato, F.; Nissley, D.A.; O’Brien, E.P. Domain topology, stability, and translation speed determine mechanical force generation on the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 5523–5532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Deutsch, C. Folding zones inside the ribosomal exit tunnel. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005, 12, 1123–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Deutsch, C. Secondary structure formation of a transmembrane segment in Kv channels. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 8230–8243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosolapov, A.; Tu, L.; Wang, J.; Deutsch, C. Structure acquisition of the T1 domain of Kv1.3 during biogenesis. Neuron 2004, 44, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, L.; Khanna, P.; Deutsch, C. Transmembrane segments form tertiary hairpins in the folding vestibule of the ribosome. J. Mol. Biol. 2014, 426, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, S.; Gartmann, M.; Halic, M.; Armache, J.P.; Jarasch, A.; Mielke, T.; Berninghausen, O.; Wilson, D.N.; Beckmann, R. alpha-Helical nascent polypeptide chains visualized within distinct regions of the ribosomal exit tunnel. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010, 17, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agirrezabala, X.; Samatova, E.; Klimova, M.; Zamora, M.; Gil-Carton, D.; Rodnina, M.V.; Valle, M. Ribosome rearrangements at the onset of translational bypassing. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, T.; Cheng, J.; Sohmen, D.; Hedman, R.; Berninghausen, O.; von Heijne, G.; Wilson, D.N.; Beckmann, R. The force-sensing peptide VemP employs extreme compaction and secondary structure formation to induce ribosomal stalling. Elife 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bano-Polo, M.; Baeza-Delgado, C.; Tamborero, S.; Hazel, A.; Grau, B.; Nilsson, I.; Whitley, P.; Gumbart, J.C.; von Heijne, G.; Mingarro, I. Transmembrane but not soluble helices fold inside the ribosome tunnel. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, S.; Franks, W.T.; Rajagopalan, N.; Doring, K.; Geiger, M.A.; Linden, A.; van Rossum, B.J.; Kramer, G.; Bukau, B.; Oschkinat, H. Structural analysis of a signal peptide inside the ribosome tunnel by DNP MAS NMR. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1600379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosolapov, A.; Deutsch, C. Tertiary interactions within the ribosomal exit tunnel. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009, 16, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, E.P.; Hsu, S.T.; Christodoulou, J.; Vendruscolo, M.; Dobson, C.M. Transient tertiary structure formation within the ribosome exit port. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 16928–16937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, J.; von Heijne, G.; Beckmann, R. Small protein domains fold inside the ribosome exit tunnel. FEBS Lett. 2016, 590, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, L.; Berninghausen, O.; Beckmann, R. Molecular basis for the ribosome functioning as an L-tryptophan sensor. Cell Rep. 2014, 9, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohmen, D.; Chiba, S.; Shimokawa-Chiba, N.; Innis, C.A.; Berninghausen, O.; Beckmann, R.; Ito, K.; Wilson, D.N. Structure of the Bacillus subtilis 70S ribosome reveals the basis for species-specific stalling. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Pan, X.; Yan, K.; Sun, S.; Gao, N.; Sui, S.F. Mechanisms of ribosome stalling by SecM at multiple elongation steps. Elife 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, S.; Meyer, H.; Starosta, A.L.; Becker, T.; Mielke, T.; Berninghausen, O.; Sattler, M.; Wilson, D.N.; Beckmann, R. Structural basis for translational stalling by human cytomegalovirus and fungal arginine attenuator peptide. Mol. Cell 2010, 40, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercier, E.; Rodnina, M.V. Co-translational folding trajectory of the HemK helical domain. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 3460–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemp, G.; Kudva, R.; de la Rosa, A.; von Heijne, G. Force-profile analysis of the cotranslational folding of HemK and Filamin domains: Comparison of biochemical and biophysical folding assays. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 1308–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, K.A.; Batey, S.; Hooton, K.A.; Clarke, J. The folding of spectrin domains I: Wild-type domains have the same stability but very different kinetic properties. J. Mol. Biol. 2004, 344, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelkar, D.A.; Khushoo, A.; Yang, Z.; Skach, W.R. Kinetic analysis of ribosome-bound fluorescent proteins reveals an early, stable, cotranslational folding intermediate. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 2568–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Yoon, J.S.; Shishido, H.; Yang, Z.Y.; Rooney, L.A.; Barral, J.M.; Skach, W.R. Translational tuning optimizes nascent protein folding in cells. Science 2015, 348, 444–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khushoo, A.; Yang, Z.; Johnson, A.E.; Skach, W.R. Ligand-driven vectorial folding of ribosome-bound human CFTR NBD1. Mol. Cell 2011, 41, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waudby, C.A.; Wlodarski, T.; Karyadi, M.E.; Cassaignau, A.M.E.; Chan, S.H.S.; Wentink, A.S.; Schmidt-Engler, J.M.; Camilloni, C.; Vendruscolo, M.; Cabrita, L.D.; et al. Systematic mapping of free energy landscapes of a growing filamin domain during biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 9744–9749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrita, L.D.; Cassaignau, A.M.E.; Launay, H.M.M.; Waudby, C.A.; Wlodarski, T.; Camilloni, C.; Karyadi, M.E.; Robertson, A.L.; Wang, X.; Wentink, A.S.; et al. A structural ensemble of a ribosome-nascent chain complex during cotranslational protein folding. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016, 23, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notari, L.; Martinez-Carranza, M.; Farias-Rico, J.A.; Stenmark, P.; von Heijne, G. Cotranslational folding of a pentarepeat beta-helix protein. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 430, 5196–5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, A.P.; Hollins, J.J.; O’Neill, C.; Ryzhov, P.; Higson, S.; Mendonca, C.; Kwan, T.O.; Kwa, L.G.; Steward, A.; Clarke, J. Investigating the effect of chain connectivity on the folding of a beta-sheet protein on and off the ribosome. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 430, 5207–5216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckert, A.; Waudby, C.A.; Wlodarski, T.; Wentink, A.S.; Wang, X.; Kirkpatrick, J.P.; Paton, J.F.; Camilloni, C.; Kukic, P.; Dobson, C.M.; et al. Structural characterization of the interaction of alpha-synuclein nascent chains with the ribosomal surface and trigger factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 5012–5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichmann, C.; Preissler, S.; Riek, R.; Deuerling, E. Cotranslational structure acquisition of nascent polypeptides monitored by NMR spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 9111–9116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fersht, A.R.; Sato, S. Phi-value analysis and the nature of protein-folding transition states. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 7976–7981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, P.; Steward, A.; Kudva, R.; Su, T.; Shilling, P.J.; Nickson, A.A.; Hollins, J.J.; Beckmann, R.; von Heijne, G.; Clarke, J.; et al. Folding pathway of an Ig domain is conserved on and off the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E11284–E11293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guinn, E.J.; Tian, P.; Shin, M.; Best, R.B.; Marqusee, S. A small single-domain protein folds through the same pathway on and off the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 12206–12211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karniel, A.; Mrusek, D.; Steinchen, W.; Dym, O.; Bange, G.; Bibi, E. Co-translational folding intermediate dictates membrane targeting of the signal recognition particle receptor. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 430, 1607–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, E.P.; Christodoulou, J.; Vendruscolo, M.; Dobson, C.M. New scenarios of protein folding can occur on the ribosome. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krobath, H.; Shakhnovich, E.I.; Faisca, P.F. Structural and energetic determinants of co-translational folding. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 138, 215101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanazono, Y.; Takeda, K.; Miki, K. Structural studies of the N-terminal fragments of the WW domain: Insights into co-translational folding of a beta-sheet protein. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabrowski-Tumanski, P.; Piejko, M.; Niewieczerzal, S.; Stasiak, A.; Sulkowska, J.I. Protein knotting by active threading of nascent polypeptide chain exiting from the ribosome exit channel. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 11616–11625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baiesi, M.; Orlandini, E.; Seno, F.; Trovato, A. Sequence and structural patterns detected in entangled proteins reveal the importance of co-translational folding. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekman, D.; Bjorklund, A.K.; Frey-Skott, J.; Elofsson, A. Multi-domain proteins in the three kingdoms of life: Orphan domains and other unassigned regions. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 348, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockwell, D.J.; Radford, S.E. Intermediates: Ubiquitous species on folding energy landscapes? Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2007, 17, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ding, F.; Nie, H.; Serohijos, A.W.; Sharma, S.; Wilcox, K.C.; Yin, S.; Dokholyan, N.V. Protein folding: Then and now. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2008, 469, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, M.; Buchner, J.; Hugel, T.; Rief, M. Folding and assembly of the large molecular machine Hsp90 studied in single-molecule experiments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 1232–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balchin, D.; Hayer-Hartl, M.; Hartl, F.U. In vivo aspects of protein folding and quality control. Science 2016, 353, aac4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleizen, B.; van Vlijmen, T.; de Jonge, H.R.; Braakman, I. Folding of CFTR is predominantly cotranslational. Mol. Cell 2005, 20, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; David, A.; Liu, B.; Magadan, J.G.; Bennink, J.R.; Yewdell, J.W.; Qian, S.B. Monitoring cotranslational protein folding in mammalian cells at codon resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 12467–12472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Rehfus, J.E.; Mattson, E.; Kaiser, C.M. The ribosome destabilizes native and non-native structures in a nascent multidomain protein. Protein Sci. 2017, 26, 1439–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Maciuba, K.; Kaiser, C.M. The ribosome cooperates with a chaperone to guide multi-domain protein folding. Mol. Cell 2019, 74, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schopf, F.H.; Huber, E.M.; Dodt, C.; Lopez, A.; Biebl, M.M.; Rutz, D.A.; Muhlhofer, M.; Richter, G.; Madl, T.; Sattler, M.; et al. The co-chaperone Cns1 and the recruiter protein Hgh1 link Hsp90 to translation elongation via chaperoning Elongation Factor 2. Mol. Cell 2019, 74, 73–87.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monkemeyer, L.; Klaips, C.L.; Balchin, D.; Korner, R.; Hartl, F.U.; Bracher, A. Chaperone function of Hgh1 in the biogenesis of eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2. Mol. Cell 2019, 74, 88–100.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Chen, X.; Kaiser, C.M. Energetic dependencies dictate folding mechanism in a complex protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samelson, A.J.; Jensen, M.K.; Soto, R.A.; Cate, J.H.; Marqusee, S. Quantitative determination of ribosome nascent chain stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 13402–13407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, L.M.; Goldman, D.H.; Wee, L.M.; Bustamante, C. Non-equilibrium dynamics of a nascent polypeptide during translation suppress its misfolding. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, A.M.; Culviner, P.H.; Kurt-Yilmaz, N.; Zou, T.; Ozkan, S.B.; Cavagnero, S. Electrostatic effect of the ribosomal surface on nascent polypeptide dynamics. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 1195–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.N.; Bergendahl, L.T.; Marsh, J.A. Operon gene order is optimized for ordered protein complex assembly. Cell Rep. 2016, 14, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, Y.W.; Minguez, P.; Bork, P.; Auburger, J.J.; Guilbride, D.L.; Kramer, G.; Bukau, B. Operon structure and cotranslational subunit association direct protein assembly in bacteria. Science 2015, 350, 678–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benschop, J.J.; Brabers, N.; van Leenen, D.; Bakker, L.V.; van Deutekom, H.W.; van Berkum, N.L.; Apweiler, E.; Lijnzaad, P.; Holstege, F.C.; Kemmeren, P. A consensus of core protein complex compositions for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell 2010, 38, 916–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, N.K.; Dichtl, B. Co-translational control of protein complex formation: A fundamental pathway of cellular organization? Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2018, 46, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unterholzner, S.J.; Poppenberger, B.; Rozhon, W. Toxin-antitoxin systems: Biology, identification, and application. Mob. Genet. Elements 2013, 3, e26219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldfield, C.J.; Dunker, A.K. Intrinsically disordered proteins and intrinsically disordered protein regions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2014, 83, 553–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenova, I.; Mukherjee, P.; Conic, S.; Mueller, F.; El-Saafin, F.; Bardot, P.; Garnier, J.M.; Dembele, D.; Capponi, S.; Timmers, H.T.M.; et al. Co-translational assembly of mammalian nuclear multisubunit complexes. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halbach, A.; Zhang, H.; Wengi, A.; Jablonska, Z.; Gruber, I.M.; Halbeisen, R.E.; Dehe, P.M.; Kemmeren, P.; Holstege, F.; Geli, V.; et al. Cotranslational assembly of the yeast SET1C histone methyltransferase complex. EMBO J. 2009, 28, 2959–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassem, S.; Villanyi, Z.; Collart, M.A. Not5-dependent co-translational assembly of Ada2 and Spt20 is essential for functional integrity of SAGA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 1186–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, C.D.; Mata, J. Widespread cotranslational formation of protein complexes. PLoS Genet 2011, 7, e1002398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, J.; Buholzer, K.J.; Zosel, F.; Nettels, D.; Schuler, B. Charge interactions can dominate coupled folding and binding on the ribosome. Biophys. J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liutkute, M.; Samatova, E.; Rodnina, M.V. Cotranslational Folding of Proteins on the Ribosome. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10010097

Liutkute M, Samatova E, Rodnina MV. Cotranslational Folding of Proteins on the Ribosome. Biomolecules. 2020; 10(1):97. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10010097

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiutkute, Marija, Ekaterina Samatova, and Marina V. Rodnina. 2020. "Cotranslational Folding of Proteins on the Ribosome" Biomolecules 10, no. 1: 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10010097

APA StyleLiutkute, M., Samatova, E., & Rodnina, M. V. (2020). Cotranslational Folding of Proteins on the Ribosome. Biomolecules, 10(1), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10010097