1. Introduction

In the past decade, there has been a surge of interest in cosmology due to the increasingly precise observational constraints that can help elucidate the physics underlying the Universe. Despite the mounting evidence for cosmological phenomena such as the acceleration of the Universe attributed to Dark Energy (DE) and the presence of non-visible matter known as Dark Matter (DM) [

1,

2,

3], the physics community has yet to provide a comprehensive explanation for their nature.

The standard cosmological model, known as

CDM, describes the composition of the Universe, where 69% of the energy density corresponds to DE, 26% corresponds to DM, and the remaining 5% is composed of ordinary matter and light [

1]. This model has successfully accounted for various observations, including those of Type Ia Supernovae (SNe-Ia) and the cosmic microwave background (CMB), and it has been validated through cosmological simulations that depict the formation of large-scale structures [

4,

5].

However, the

CDM model exhibits inconsistencies between its description of the early and late Universe [

6]. These inconsistencies manifest in different cosmological parameters, such as the Hubble constant [

7,

8], the curvature [

9,

10], and the

tension [

11].

The Planck team measured the local expansion rate through the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation and obtained a value of

km/s/Mpc, which aligns with a flat

CDM model [

1]. However, the SH0ES collaboration independently measured a higher value of

km/s/Mpc for the local Universe [

7], creating a discrepancy with the Planck value exceeding

. Importantly, this tension between the early and late Universe persists even without considering the Planck CMB data or the SH0ES distance ladder [

6].

Furthermore, the H0LiCOW collaboration derived a direct measurement of

km/s/Mpc based on lensing time delays, which exhibits a moderate tension with the Planck value [

12]. Additionally, a constraint obtained from the Big Bang nucleosynthesis (BBN) combined with baryon acoustic oscillation (BAO) data yielded

km/s/Mpc, which is inconsistent with the SH0ES measurement [

6].

Other studies have attempted to explain the discrepancy by suggesting that the Hubble constant determined from nearby SNe-Ia may differ from that measured from the CMB due to cosmic variance, with a potential difference of

percent at

statistical significance. However, this variation does not account for the observed discrepancy between SNe-Ia and CMB measurements [

13]. In an extreme case, observers situated in the centers of vast cosmic voids might measure a Hubble constant biased high by 5 percent from SNe-Ia.

Since the initial publication highlighting the

tension [

2], numerous inquiries have emerged regarding the source of this discrepancy. One suggestion is that errors in the calibration of Cepheids, which contribute to systematic errors, could be responsible. However, this potential error has been thoroughly discussed and dismissed by Riess et al. [

14].

Other publications have explored possible solutions to the observed acceleration of the Universe, including anisotropies at local scales. Wang et al. [

15], using SNe-Ia data, found evidence of anisotropies associated with the direction and amplitude of the bulk flow. Nonetheless, the impact of dipolar distribution of dark energy cannot be ruled out at high redshifts. Similarly, another publication [

16] suggests that the anisotropies in cosmic acceleration may be linked to the nature of Dark Energy, implying that the perceived cosmic acceleration deduced from supernovae could be an artifact of our non-Copernican perspective rather than evidence of a dominant “dark energy” component in the Universe. Sun et al. [

17] conclude that even in the presence of anisotropy, Dark Energy cannot be entirely ruled out. While such proposals could potentially explain variations in local measurements, including different values for the local Hubble constant, they could contradict the analyses conducted by Planck using the

CDM model. The Dark Energy component is crucial for the evolution of CMB photons from the last scattering surface until the present, and altering the sum over

for each component in the Universe would lead to significant changes. Various other suggestions concerning discrepancies have emerged not only related to SNe-Ia measurements but also within the Planck data itself. The presence of anisotropies in these measurements has been a subject of debate due to high uncertainties and inconsistent results. Hypotheses proposing the possibility of a Universe with less Dark Energy [

18] have also been put forward.

Another potential source of error in local measurements could be the inhomogeneity in local density [

19,

20]. However, in this scenario, the presence of local structures does not seem to impede the possibility of measuring the Hubble constant with a precision of 1%, and there is no evidence of a Hubble constant change corresponding to an inhomogeneity.

Today, there are different methods to obtain the Hubble constant, including the use of SNe-II, ref. [

21]. In this research, SNe-II were employed as standard candles to obtain an independent measurement of the Hubble constant. The resulting value was

km /s/Mpc. The local

value is higher than the value derived from the early Universe, with a confidence level of 95%. The researchers concluded that

there is no evidence that SNe-Ia are the source of the tension. In another publication analyzing SNe-Ia as standard candles in the near-infrared, it was concluded that

= 72.8 ± 1.6 (statistical) ±2.7 (systematic) km/s/Mpc. This study also suggested that the tension in the competing

distance ladders is likely not a result of supernova systematics.

Other proposals have tried to reconcile Planck and SNe-Ia data, including modifications to the physics of the DE. In other words, introducing an equation of state of the interacting dark energy component, where

w is allowed to vary freely, could solve the

tension [

22]. Additionally, a decaying dark matter model has been proposed to alleviate the

and

anomalies [

23]; in their work, they reduce the tension for both measurements when only consider Planck CMB data and the local SH0ES prior on

. However, when BAOs and the JLA supernova dataset are included, their model is weakened.

Other disagreements are related to inconsistencies with curvature (and other parameters needed to describe the CMB) [

10], or they are related to the tension between measurements of the amplitude of the power spectrum of density perturbations (inferred using CMB) and directly measured by large-scale structure (LSS) on smaller scales [

11]. Extensions of

CDM models have been considered [

24] in an attempt to solve the tension of

. However, they concluded that none of these extended models can convincingly resolve the

tension. For a full scope of the Hubble tension, please see [

25]. Through the time, the tension between Planck and SNe-Ia persists [

1,

14], where the

is the most significant tension. Furthermore, the Universe is composed principally by DE, but we still do not know what it is.

Over the past decades, various proposals have been made to explain the observed acceleration of the Universe. These proposals involve the inclusion of additional fields in approaches such as Quintessence, Chameleon, Vector Dark Energy or Massive Gravity, the addition of higher-order terms in the Einstein–Hilbert action, such as

theories and Gauss–Bonnet terms, and the introduction of extra dimensions for a modification of gravity on large scales [

26]. Other interesting possibilities include the search for non-trivial ultraviolet fixed points in gravity (asymptotic safety, [

27]) and the notion of induced gravity [

28,

29,

30,

31]. The first possibility uses exact renormalization-group techniques [

32,

33] together with a lattice and numerical techniques, such as Lorentzian triangulation analysis [

34]. Induced gravity proposes that gravitation is a residual force produced by other interactions.

Delta gravity (DG) is an extension of General Relativity (GR) where new fields are added to the Lagrangian through a new symmetry [

35,

36,

37,

38]. The main properties of this model at the classical level follow: (a) It agrees with GR outside the sources and with adequate boundary conditions. In particular, the causal structure of delta gravity in a vacuum is the same as in General Relativity, satisfying all standard tests automatically. (b) When studying the evolution of the Universe, it predicts acceleration without a cosmological constant or additional scalar fields. The Universe ends in a BigRip, which is similar to the scenario considered in [

39]. (c) The scale factor agrees with the standard cosmology at early times and show acceleration only at late times. Therefore, we expect that density perturbations should not have large corrections at the moment of last scattering (denoted by

).

It was noticed in [

40] that the Hamiltonian of delta models is not bounded from below. Phantom cosmological models [

39,

41] also have this property. The present model could provide an arena to study the quantum properties of a phantom field, since the model has a finite quantum effective action. In this respect, the advantage of the present model is that being a gauge model, it could give us the possibility of solving the problem of lack of unitarity using standard techniques of gauge theories such as the BRST method [

36]. However, we are not concerned about this feature in this work, because we are considering DG as a phenomenological model that interpolates the observations of the early with the late Universe.

This theory predicts an accelerating Universe without a cosmological constant

and a Hubble parameter

Km/s/Mpc [

42] when fitting SN-Ia Data, which is in agreement with SH0ES.

On the other hand, temperature correlations provide us with information about the constituents of the Universe, including baryonic and dark matter. Typically, these calculations are performed using software such as CMBFast [

43,

44] or CAMB

1 [

45]. These codes employ Boltzmann equations for the fluids and their interactions, yielding well-established results that are consistent with Planck measurements [

1].

Nevertheless, one can obtain a good approximation of this complex problem [

46,

47]. In this work, we use an analytical method that consists of two steps instead of studying the evolution of the scalar perturbations using Boltzmann equations. First, we use a hydrodynamic approximation, which assumes photons and baryonic plasma as a fluid in thermal equilibrium at recombination time when there is a high rate of collisions between free electrons and photons. Second, we study the propagation of photons [

35] by radial geodesics from the moment when the Universe switches from opaque to transparent at time

until now.

In this research, we develop the theory of scalar perturbations at first order. We discuss the gauge transformations in an extended Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker (FRLW) Universe. Then, we show how to obtain an expression for temperature fluctuations, and we demonstrate that they are gauge invariant, which is crucial from a theoretical point of view. With this result, we derive a formula for the scalar contribution to temperature multipole coefficients. This formula is useful to test the theory, and it could indicate the physical consequence of the “delta matter” introduced in this theory. This work has been incorporated as a part of the Ph.D. thesis [

48], where more details can be found.

The CMB provides cosmological constraints crucial for testing a model. Many cosmological parameters can be obtained directly from the CMB power spectrum, such as

and

[

1], while others can be derived from constraining CMB observation with SNe-Ia or BAOs. By studying the CMB anisotropies, we can address two aspects: the compatibility between the CMB power spectrum and DG fluctuations and the compatibility between CMB and SNe-Ia in the DG theory. In [

49], we already fitted Planck satellite’s data with a DG model using Markov Chain Monte Carlo analysis. We also studied the compatibility between SNe Ia and CMB observation in this framework. We obtained the scalar CMB TT power spectrum and the fitted parameters needed to explain both SNe-Ia data and CMB measurements. The results are in reasonable agreement with both observations considering the analytical approximation. We also discussed whether the Hubble constant and the accelerating Universe are in concordance with the observational evidence in the DG context. With this in mind, the aim of this work is to present the full theoretical scheme for the scalar perturbation theory.

The paper is organized as follows: In

Section 2, we introduce the definition of DG and its equations of motion. We then review some implications of the first law of thermodynamics, which will allow us to interpret the physical quantities of DG. Before finishing this section, we state the ansatz that the moment of equality between matter and radiation was equal in both DG and GR, and we discuss its implications. In

Section 3, we study the gauge transformation for small perturbations of both geometrical and matter fields. We choose a gauge and present the gauge-invariant equations of motion for small perturbations. In

Section 4, we study the evolution of cosmological perturbations, solving the equations partially when the Universe is dominated by radiation and when it is dominated by matter. In

Section 5, we derive the formula for temperature fluctuation. Here, we find that this fluctuation can be expressed in three independent and gauge-invariant terms. In

Section 6, we obtain a formula for temperature multipole coefficients for scalar modes. We also present preliminary numerical results for the power spectrum of the CMB. Finally, we provide conclusions and remarks.

For notation, we will use the Riemann tensor:

where the Ricci Tensor is given by

, the Ricci scalar

and:

is the usual Christoffel symbol. Finally, the covariant derivative is given by:

So, it is defined with the usual metric .

2. Definition of Delta Gravity

In this section, we will present the action as well all the symmetries of the model and derive the equations of motion. These approaches are based on the application of a variation called

, and it has the usual properties of a variation such as:

where

is another variation. The main point of this variation is that when it is applied on a field (function, tensor, etc), it produces new elements that we define as

fields, which we treat as an entirely new independent object from the original,

. We use the convention that a tilde tensor is equal to the

transformation of the original tensor when all its indexes are covariant. (For more detail about

, please see

Appendix A.1.)

Now, we will present the

prescription for a general action. The extension of the new symmetry is given by:

where

is the original action and

S is the extended action in Delta Gauge Theories. When we apply this formalism to the Einstein–Hilbert action of GR, we obtain [

35]

where

(hereafter, we set

),

,

is the matter Lagrangian and:

where

are the

matter fields or “delta matter” fields. The equations of motion are given by the variation of

and

. It is easy to see that we obtain the usual Einstein’s equations varying the action (

6) with respect to

. On the other hand, variations with respect to

give the equations for

:

with:

where

denotes the totally symmetric combination of

and

. It is possible to simplify (

9) (see [

35]) to obtain the following system of equations:

where

. The energy momentum conservation now is given by

Then, we are going to work with Equations (

11)–(

14). However, as the perturbation theory in the standard sector is well known (see [

47]), we will focus on the DG sector.

One important result of DG is that photons follow geodesic trajectories given by the effective metric

[

35], and for an FRLW Universe, these metrics take the form (with constant curvature parameter

)

and

where

is a time-dependent function which is determined by the solution of the unperturbed equations system, and

is the standard scale factor, which in

Section 4 we will show is no longer the physical scale factor of the Universe. To obtain the form of

and

, first we impose isotropy and homogeneity, and then, we apply the harmonic gauge

and its tilde version (for details, see [

37]). One of the implications of this effective metric is that geometry is now described by a new tridimensional metric given by [

35]

2 (latin indexes run from 1 to 3)

while the proper time is defined by

. In this case,

t is the cosmic time.

2.1. DG and Thermodynamics

Now, we will study some implications of thermodynamics in cosmology for DG. Equation (

17) defines the modified scale factor of this theory:

Then, the volume of a cosmological sphere is now

Any physical fluid has a density given by

where

U is the internal energy and

V is the volume. From the first law of thermodynamics, we have

We will assume that the Universe evolved adiabatically; this means

. Then, we obtain the well-known relation for the energy conservation

with

. In order to know the evolution of

, we need an equation of state

. In [

38], they showed that

replaces the first Friedmann equation. Now, we know that the second Friedmann equation is the thermodynamics statement that the Universe evolves adiabatically, so the physical densities must satisfy Equation (

21). If we assume

, we found

where

is the density at present. A crucial point in this theory is that the GR field Equations (

11) and (

13) are valid; then, we also have a similar relation for the densities of GR but with the standard scale factor

, explicitly

Then, we can relate both densities by the ratio between them

This ratio will be vitally important when we study the perturbations of the system. Because we will study the evolution of fractional perturbations at the last-scattering time defined as

where

runs between

,

,

B and

D (photons, neutrinos, baryons and dark matter, respectively). If we consider the results from [

38], at the moment of last-scattering (

), we obtain

This mean that at that moment, the physical density was proportional to the densities of GR, and without a loss of generality, we can take

as it will be introduced in

Section 4. In fact, Equation (

26) is valid for a wide range of times, from the beginning of the Universe (

) until

, so this approximation is valid in the study of primordial perturbations in DG when using the equations of GR. On the other hand, the number density (number of photons over the volume) at equilibrium with matter at temperature

T is

After decoupling, photons travel freely from the surface of last scattering to us. So, the number of photons is conserved

as frequencies are redshifted by

, and the volume

. We find that in order to keep the form of a black body distribution, temperature in the number density should evolve as

.

2.2. Equality Time

After concluding this section, there is an ansatz that we need to propose in order to be completely consistent when solving the cosmological perturbation theory in the next section. This is about when the radiation was equal to the non-relativistic matter. We state that the moment when radiation and matter were equal at some

is the same in GR as in DG. The implication of this statement is the following: let us consider the ratio of the matter and radiation densities of GR (

23)

We remind that

. Then, the moment of equality in GR corresponds to

. On the other hand, if we consider the same ratio but now between the physical densities using (

22), we obtain

where

. Then, in the equality, we need to impose

, explicitly

if we take the value from [

42] (they used

instead of

L, but these are the same quantity also),

and

implies

and

, then

This means that the total density of matter and radiation today depend explicitly on the geometry measured with

L [

42].

4. Evolution of Cosmological Fluctuations

Until now, we have developed the perturbation theory in DG; now, we are interested in studying the evolution of the cosmological fluctuations to have a physical interpretation of the delta matter fields, which this theory naturally introduces. Even in the standard cosmology, the system of equations that describes these perturbations are complicated to allow analytic solutions, and there are comprehensive computer programs for this task, such as CMBfast [

43,

44] and CAMB [

45]. However, such computer programs cannot give a clear understanding of the physical phenomena involved. Nevertheless, some good approximations allow computing the spectrum of the CMB fluctuations with a rather good agreement with these computer programs [

46,

47]. In particular, we are going to extend the Weinberg approach for this task. This method consists of two main aspects: first, the hydrodynamic limit, which assumes that near recombination time photons were in local thermal equilibrium with the baryonic plasma; then, photons could be treated hydro-dynamically, such as plasma and cold dark matter. Second, a sharp transition from thermal equilibrium to complete transparency at the moment

of the last scattering.

Since we will reproduce this approach, we consider the Universe’s standard components, which means photons, neutrinos, baryons, and cold dark matter. Then, the task is to understand the role of their own delta counterpart. We will also neglect both anisotropic inertia tensors and took the usual state equation for pressures and energy densities and perturbations. As we will treat photons and delta photons hydrodynamically, we will use

and

. Finally, as the synchronous scheme does not completely fix the gauge freedom, one can use the remaining freedom to put

, which means that cold dark matter evolves at rest with respect to the Universe expansion. In our theory, the extended synchronous scheme also has extra freedom, which we will use to choose

as its standard part. Now, we will present the equations for both sectors. However, we will provide more detail in the delta sector because Weinberg [

47] already calculates the solution of Einstein’s equations. Einstein’s equations and its energy-momentum conservation in Fourier space are

5

where

. It is useful to rewrite these equations in term of the dimensionless fractional perturbation

where

can be

,

,

B and

D (photons, neutrinos, baryons and dark matter, respectively).

,

,

,

are time-independent quantities; then, (

96)–(

100) are

where

. By the other side, in the delta sector, we will use a dimensionless fractional perturbation. However, this perturbation is defined as the delta transformation of (

101)

6,

We will assume that this quotient holds for every component. In addition, using the result that

,

,

,

are time independent, the equations for the delta sector are

with

. Due to the definition of tilde fractional perturbation (

103), solutions for (

105a)–(

105g) can be obtained easily, putting all solutions of GR equal to zero; then, the system is exactly equal to the system of Equations (

102a)–(

102g) and the solutions of tilde perturbations in the homogeneous system are exactly equal to the GR solutions. Then, we only need to “turn on” the GR source and find the complete solutions just like a forced-system. We will impose initial conditions to find solutions valid up to recombination time. At sufficiently early times, the Universe was dominated by radiation, and as Friedmann equations are valid in our theory (in particular the first equation), we can use a good approximation given by

and

, while

R and

. Here

We are interested in adiabatic solutions in the sense that all the

and

become equal at very early times. So, we make the ansatz:

Finally, we drop the term

because we are considering very early times. Then, Equations (

102a)–(

102g) become

and

An inspection of Equation (

95) shows that at this era, for

, we have

. In addition, in DG, time can be integrated from the first Friedmann equation with only radiation and matter, and one obtains:

We recall that

assuming

,

is the usual Hubble parameter which we recall is no longer the physical Hubble parameter. Thus, radiation era time and

were related by

. This complete system consisting of Equations (

109)–(

111) and Equations (

112)–(

114) has an analytical solution:

where

7

is a gauge-invariant quantity, which take a time-independent value for

. Here,

is the GR definition of the Hubble parameter, which we recall is no longer the physical one. On the other hand, we obtain

We will talk about these initial conditions later. Note that Equations (

102b)–(

102d) give

This implies that if we start from adiabatic solutions,

is true for all the Universe evolution (the same happens for its delta version from Equations (

105b)–(

105d)).

Matter Era

In this era, we use

, then (still using

), we have

For the delta sector,

where (in this era),

It is remarkable that in the GR sector, there are exact solutions given by

where

,

and

are time-independent dimensionless functions of the dimensionless re-scaled wave number

and

are, respectively, the Robertson–Walker scale factor and the expansion rate at matter radiation equally. These are referred to as transfer functions. (These functions can only depend on

because they need to be independent of spatial coordinates’ normalization and are dimensionless. A comprehensive analysis of the behavior of these functions can be found in [

47].) Conversely, delta perturbations do not have an exact solution, and numerical calculations are necessary to determine them. However, in this work, we will not present numerical solutions and instead focus on estimating the initial conditions of the perturbations at the end of this section.

In order to obtain all transfer functions, we have to compare solutions with the full equation system (with

). To do this task, let us make the change of variable

; this means

In addition, we will use the following parametrization for all perturbations

and

Then, Equations (

124a)–(

124d) and Equations (

124e)–(

124h) become

and

In this notation, the initial conditions are

From supernovae fit, we know that

and

[

37,

42]; thus, we can estimate that fluctuations of “delta matter” at the beginning of the Universe were much smaller than fluctuations of standard matter. For example, at

, the ratio between components of the Universe is

.

We do not show numerical solutions here because the aim of this work is to trace a guide for future work, in particular, in the numeric computation of multipole coefficients for temperature fluctuations in the CMB. However, we will derive the equations to calculate that computation.

5. Derivation of Temperature Fluctuations

It is possible to find expressions analogous to temperature fluctuations usually obtained by Boltzmann equations by studying photons propagation in FRLW-perturbed coordinates, with the condition

8. For DG, the metric which photons follow is given by

A ray of light propagating to the origin of the FRLW coordinate system, from a direction

, will have a comoving radial coordinate

r related with

t by

in other words,

where

is the modified scale factor given by

Now, we will use the approximation of a sharp transition between the opaque and transparent Universe at a moment

of last scattering at red shift

. With this approximation, the relevant term at the first order in Equation (

136) is

where

and

is the zero-order solution for the radial coordinate.

when

:

If a ray of light arrives to

at a time

, then Equation (

138) gives

A time interval

, between the departure of successive rays of light at time

of last scattering, produces an interval of time

between the arrival of the rays of light at

, which are given by the variation of Equation (

141):

The velocity terms of the photon–gas or photon–electron–nucleon arise because of the variation with respect to the time of the radial coordinate

described by Equation (

141). The exchange rate of

is

then,

This result gives the ratio between the time intervals between ray of lights that are emitted and received. However, we are interested in this ratio but for the proper time, which in DG is defined with the original metric

:

At first order, it gives the ratio between a received frequency and an emitted one:

In [

42], we defined the physical scale factor as

. Thus, we recover the standard expression for the redshift. The observed temperature at the present time

from direction

is

In the absence of perturbations, the observed temperature in all directions should be

Therefore, the ratio between the observed temperature shift that comes from direction

and the unperturbed value is

For scalar perturbations in any gauge with

, the metric perturbations are

In addition, for scalar perturbations, the radial velocity of the photon fluid and the delta versions are given in terms of the velocity potentials

and

, respectively,

Then, Equation (

148) gives the scalar contribution to temperature fluctuations

where

In the next step, we will study the gauge transformations of these fluctuations. The following identity for the fields

B and

will be useful:

Then, the temperature fluctuations are described by

where

The “late” term is the sum of independent direction terms and a term proportional to , which was added to represent the local anisotropies of the gravitational field and the local fluid. In GR, these terms only contribute to the multipole expansion for and . Thus, we will ignore their contribution to our derivation of the temperature fluctuations multipoles coefficients.

5.1. Gauge Transformations

We are going to study the gauge transformations for photons propagating in the metric

for a parameter

. Then, the transformations are

and

Now, considering the sum of the perturbations, we obtain

Now, we will study the gauge transformations that preserve the condition

. This means that

. This gives a solution for

given by

When we study how the “ISW” term transforms under this type of transformation, we found that

. While for the “early” term, we should note that temperature perturbations transform as

With this expression and

, we finally obtain

This results implies that the “early” term is invariant under this gauge transformation. Note that this gauge transformation is equivalent to the previously discussed in

Section 1, because we can always take

as a combination of

and

. Then, we remark that temperature fluctuations are gauge invariant under scalar transformations that leave

.

5.2. Single Modes

We will assume that since the last scattering until now, all the scalar contributions are dominated by a unique mode such that any perturbation

could be written as

where

is a stochastic variable, which is normalized such that

Then, Equations (

155) and (

157) become

where

These functions are called form factors. We emphasize that combination given by and , and the expressions inside the integral are gauge invariants under gauge transformations that preserve equal to zero.

6. Coefficients of Multipole Temperature Expansion: Scalar Modes

As an application of the previous results, we will study the contribution of the scalar modes for temperature–temperature correlation, which is given by:

where

is the stochastic variable which gives the deviation of the average of observed temperature in direction

, and

denotes the average over the position of the observer. However, the observed quantity is

Nevertheless, the mean square fractional difference between this equation and Equation (

172) is

, and therefore, it may be neglected for

. In order to calculate these coefficients, we use the following expansion in spherical harmonics

where

represents the spherical Bessel’s functions. Using this expression in Equation (

166), and replacing the factor

for time derivatives of Bessel’s functions, the scalar contribution of the observed T–T fluctuations in direction

is

where

and

is a stochastic parameter for the dominant scalar mode. It is normalized such that

Inserting this expression in Equation (

172), we obtain

Now, we will consider the case

. In this limit, we can use the following approximation for Bessel’s functions

9:

where

, and

, with

. In addition, for

, the phase

is a function of

that grows very fast; then, the derivatives of Bessel’s functions only act in its phase:

Using these approximations in Equation (

178) and changing the variable from

q to

, we obtain

When

, the functions

and

oscillate very rapidly; then, the squared average of its values are

, while the averaged cross-terms are zero. Using

, and changing the integration variable from

b to

, Equation (

181) becomes

Note that

is the angular diameter distance of the last scattering surface. To calculate the CMB power spectrum, we need to know the value of

. We use the off-diagonal equation from the delta sector to obtain it. This gives:

so if we use this equation with the definition of

it allows us to find

. Now, we will use the approximation that perturbations of a gravitation field are dominated by perturbations of dark matter density. In this regime

and in the synchronous gauge, the velocity perturbations for dark matter are zero; then,

and

where

In GR,

, and

implies

. Therefore, the usual form factors are:

where we have used

. Nevertheless, for the “delta” contribution,

and

satisfy the same relation as the standard case. Due to our decomposition, the tilde expresions are

Unfortunately, due to all the approximations we have used, we need to add some corrections to the solutions of the GR sector. After that, we will be able to find the numerical solutions for DG perturbations. The first consideration is that in the set of equations presented in the matter era, we have used

, which is not valid in this era. Corrections to the solutions can be calculated using a WKB approximation for perturbations

10 [

47]. The second consideration that we must include in the solution of photons perturbations is the so-called Silk damping

11 [

52,

53], which takes into account the viscosity and heat conduction of the relativistic medium. Moreover, the transition from opaque to a transparent Universe at the last scattering moment was not instantaneous, but it could be considered a Gaussian. This effect is known as Landau damping

12. We must recall that the physical geometry now is described by

, so the expression for both Silk and Landau effects has to be expressed in this geometry. With these considerations, the solutions of perturbations are given by:

Here, we used an approximation given by

, and the error of this approximation is of the order

.

where

where

is the mean free time for photons and

. In order to evaluate the Silk damping, we have

where

is the number density of electrons and

is the Thomson cross-section.

On the other hand

where

is the speed of sound,

is the sound horizon radial coordinate and

is the horizon distance.

With all this approximation, the transfers functions were simplified to the following expressions:

where

. Then, we replaced the GR solutions, and we obtain

where

(defined in Equation (

131)) and

The final consideration that we must include is that due to the reionization of hydrogen at by ultraviolet light coming from the first generation of massive stars, photons of the CMB have a probability of being scattered . CMB has two contributions. The non-scattered photons provide the first contribution, where we have to correct by a factor given by . The scattered photons provide the second contribution, but the reionization occurs at affecting only low ls. We are not interested in this effect, and therefore, we will not include it. Measurements show that in GR, .

On the other hand, we will use a standard parametrization of

given by

where

could vary with the wave number. It is usual to take

Mpc

.

Note that

is the angular diameter distance of the last scattering surface.

This is consistent with the luminosity distance definition [

38]. Then, when we set

, we obtain

Using similar computations for the other distances, the final form of the form factors is given by

where

To summarize, for reasonably large values of

l (say

), CMB multipoles are given by

The structure of Equation (

213) is remarkable, where the delta sector contributes additively inside the integral. If we set all the delta sector equal to zero, we recover the result directly for scalar temperature–temperature multipole coefficients in GR given by Weinberg. Numerical solutions are needed to compute the solution for the perturbations. In a preliminary numerical solution, we obtained the temperature power spectrum of the CMB following Weinberg’s approach [

47]. We obtain:

where

is the density of non-relativistic matter, and

is the baryon density.

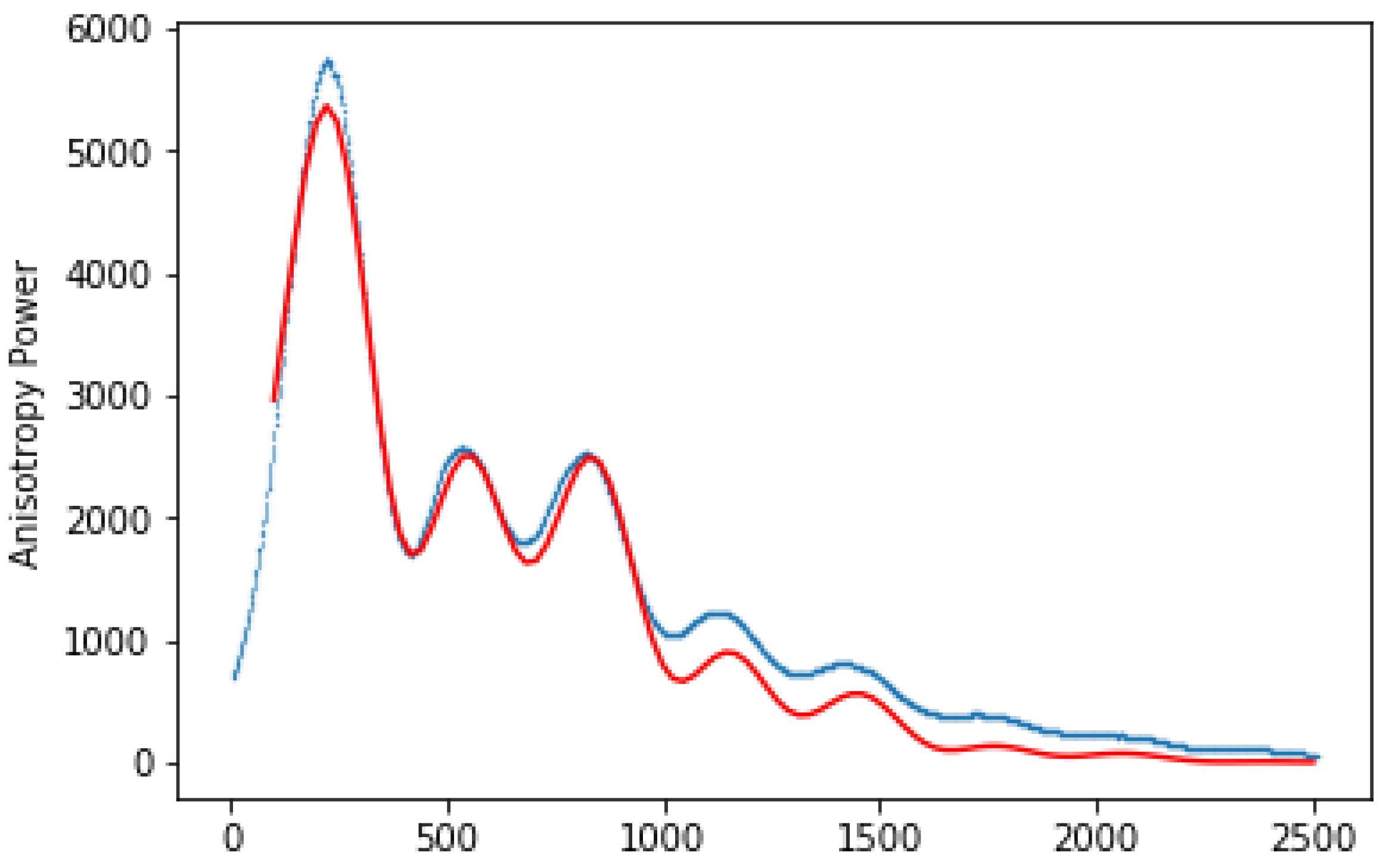

Figure 1 displays the temperature power spectrum for a specific set of cosmological parameters. These cosmological parameters were obtained through exploratory analysis without any statistical examination. In other words, preliminary values were tested to determine if there was any possibility of obtaining reasonable results for the temperature power spectrum using the delta gravity equations. Consequently, the plot does not incorporate error bars.

In the work conducted in ApJ [

49], the shape of the temperature power spectrum is determined by five free parameters. These parameters were explored using a modified adaptive Metropolis MCMC algorithm. The statistical study, which aimed at determining the optimal parameter space to match the observed data of the temperature power spectrum, is complicated. The complexity arises from the involved equations of delta gravity, which encompass integrals that are computationally intensive, particularly when the MCMC algorithm performs numerous calculation cycles. Moreover, additional equations accounting for the Landau damping effect and other physical considerations during the last scattering epoch, specific to the delta gravity model, need to be included.

To overcome the computational challenges, an adaptive step method was employed for each parameter independently. Additionally, pre-generated interpolation tables for each integral involved in the calculation were utilized to reduce the computational time during each execution of the MCMC cycle. The endeavor of obtaining optimal parameters for the power spectrum involves an extensive study that significantly differs from this work in terms of physical considerations, statistical approach and numerical methods required to achieve that goal.