Plant-Derived Secondary Metabolites Tetrahydropalmatine and Rutaecarpine Alleviate Paclitaxel-Induced Neuropathic Pain via TRPV1 and TRPM8 Modulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Screening of Active Compounds and ADMET Prediction

2.2. Identification of Potential Targets for ER and CY and Construction of the PPI Network

2.3. Animals

2.4. Preparation of Herbal Extracts

2.5. Administration of Paclitaxel, CY, ER, THP, and Rutaecarpine

2.6. Behavioral Test

2.7. Tissue Collection and Perfusion

2.8. Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

2.9. Protein Expression by Western Blot

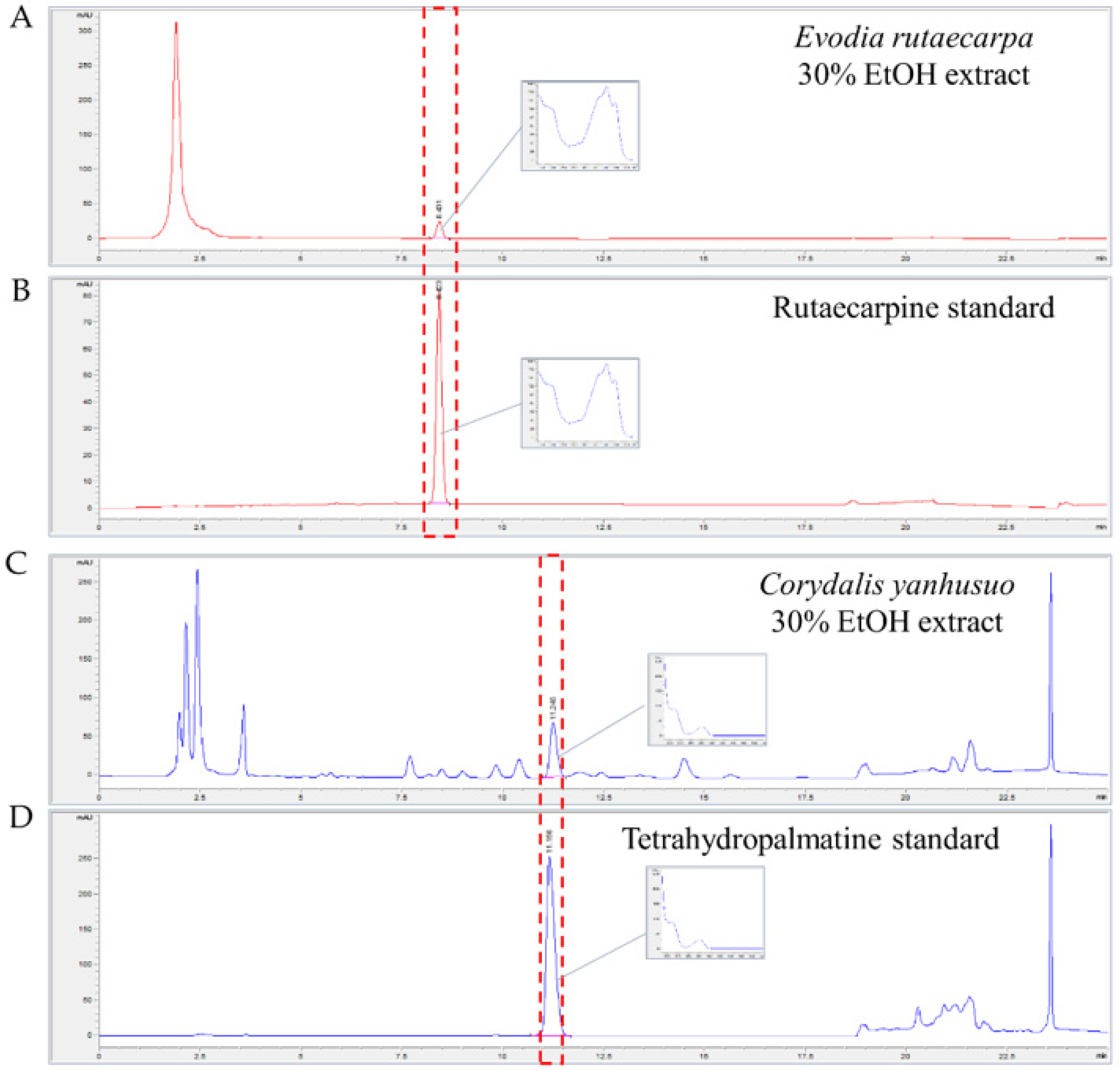

2.10. Assay Identification and Quantification of THP in CY and Rutaecarpine in ER

2.11. Identification of Potential Targets for THP and Rutaecarpine and Construction of the PPI Network

2.12. KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis and Molecular Docking Simulation

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

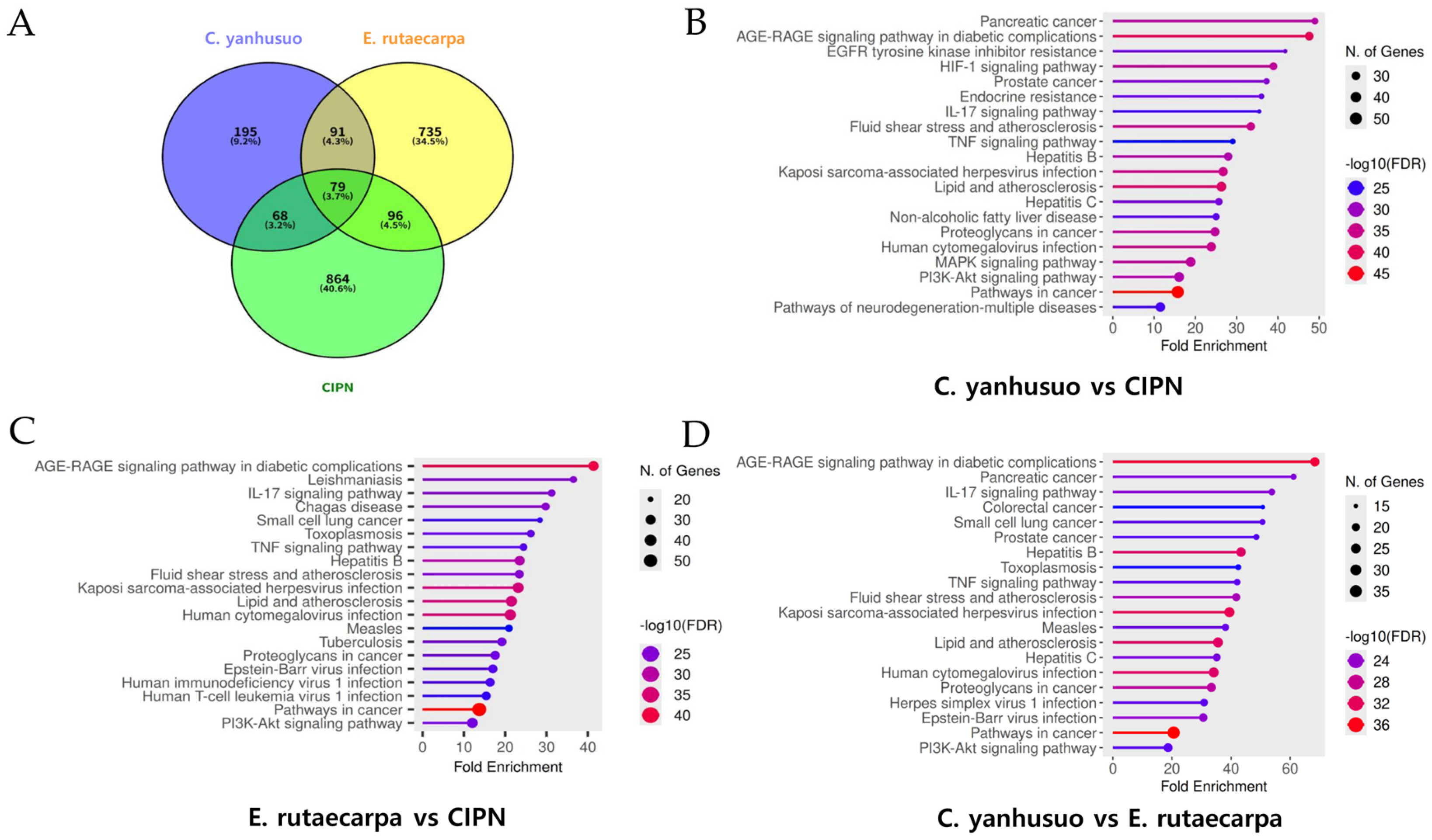

3.1. Shared Targets Selected from Active Components of CY and ER and KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis for CIPN

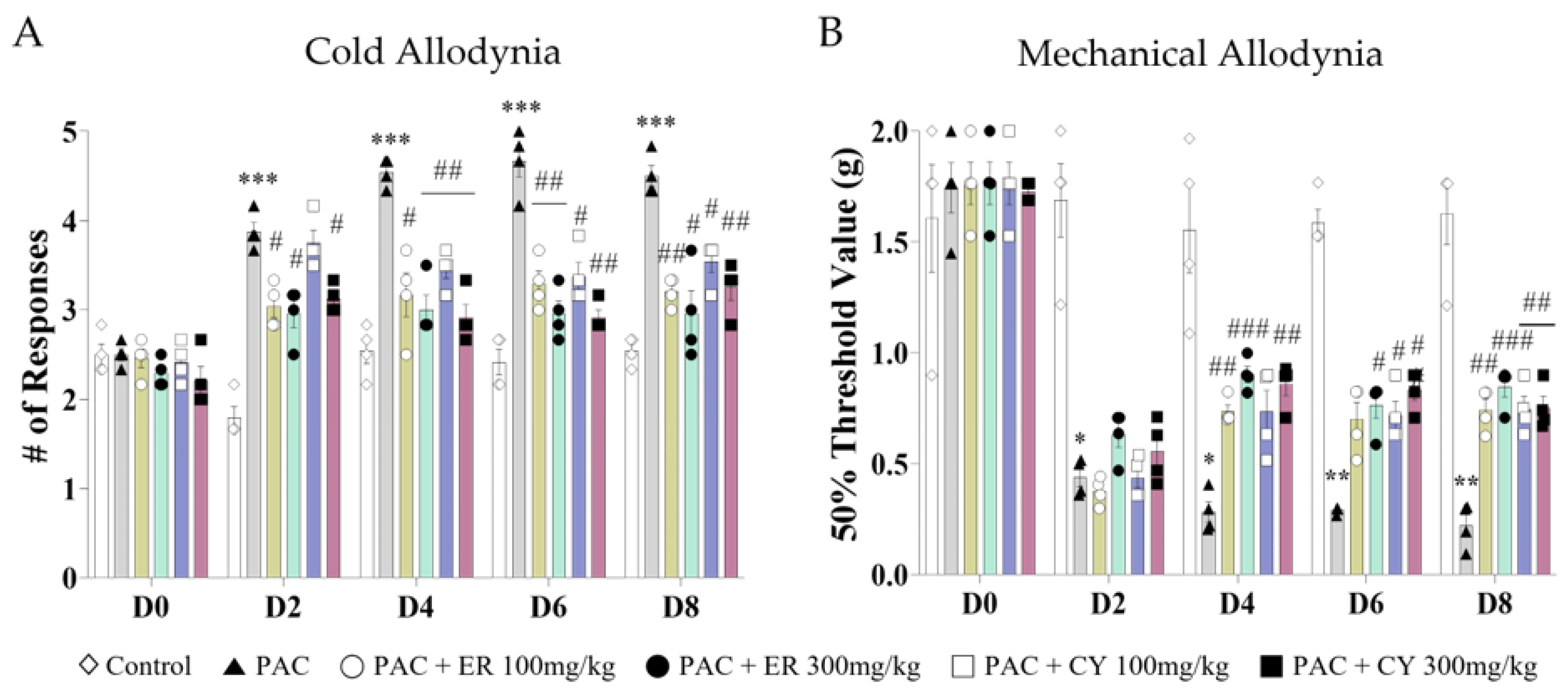

3.2. Analgesic Effect of CY and ER on Cold and Mechanical Allodynia Induced by Paclitaxel

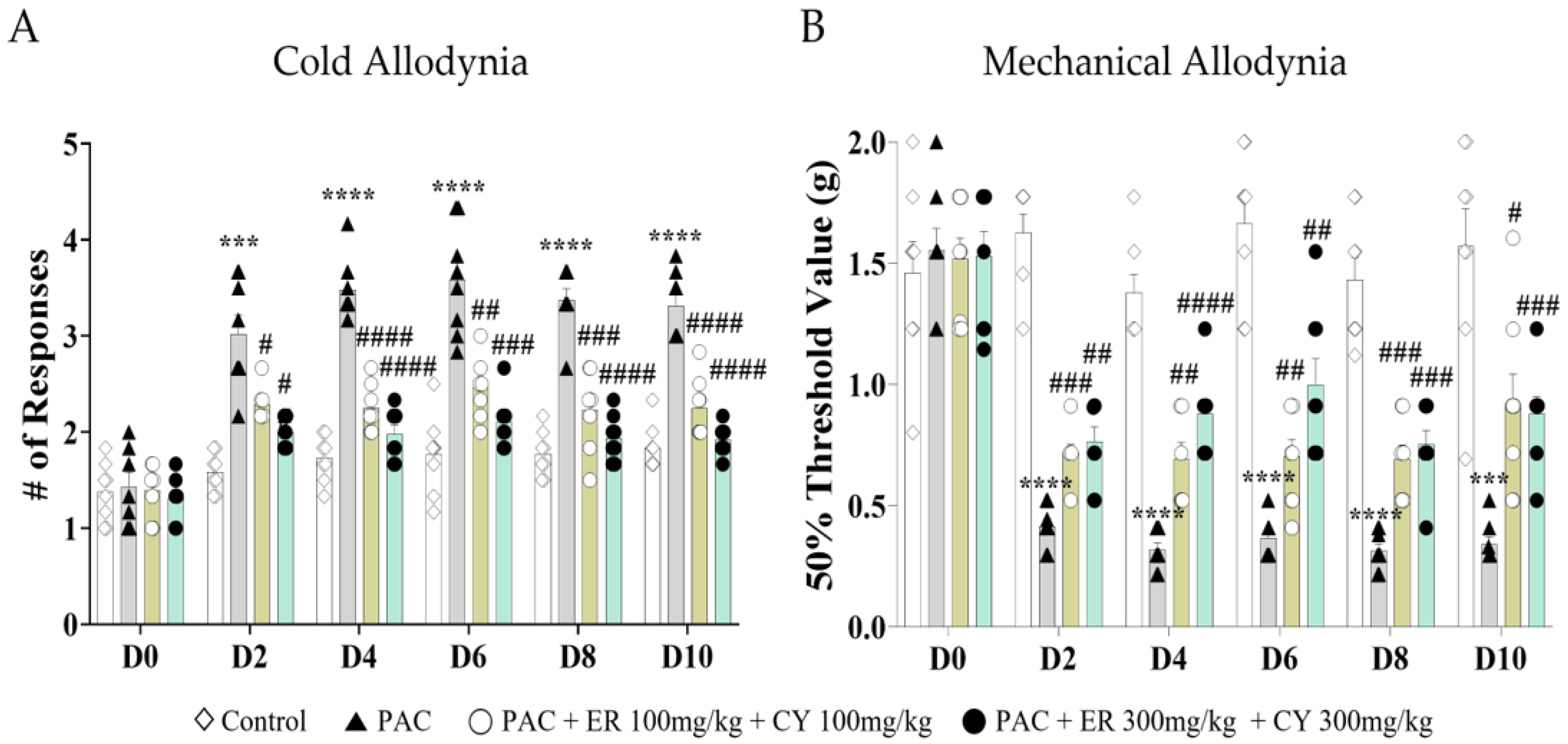

3.3. Analgesic Effect of Combined CY and ER Administration on Cold and Mechanical Allodynia Induced by Paclitaxel

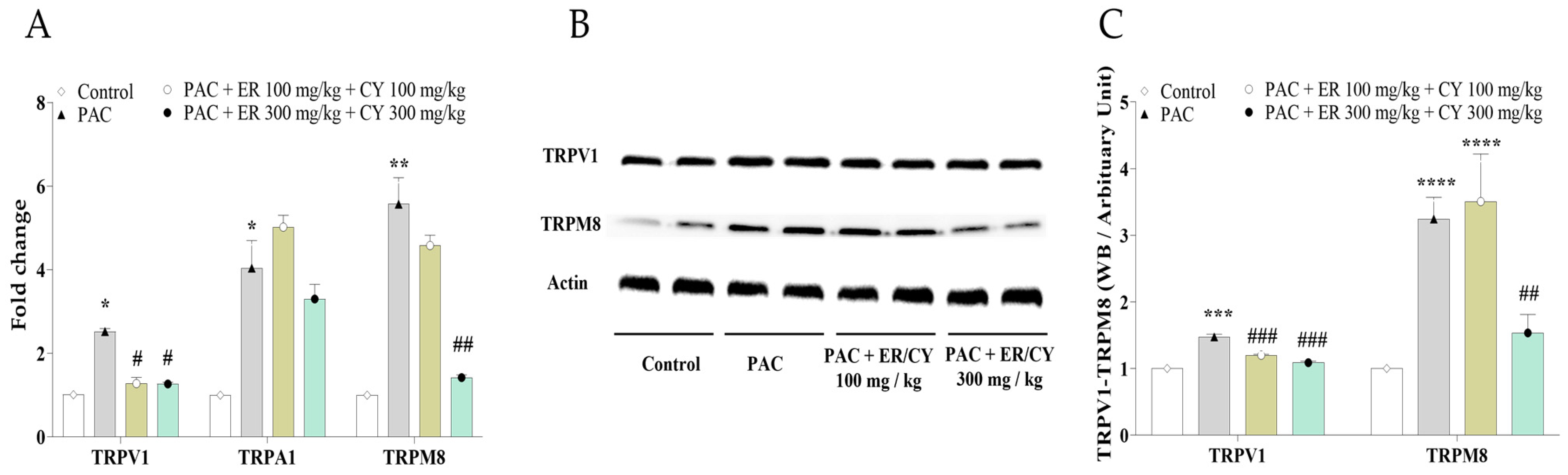

3.4. Effects of ER and CY on Paclitaxel-Induced TRPV1, TRPM8, and TRPA1 Expression and Cell Viability

3.5. Identification and Quantification of Rutaecarpine in ER and Tetrahydropalmatine in CY

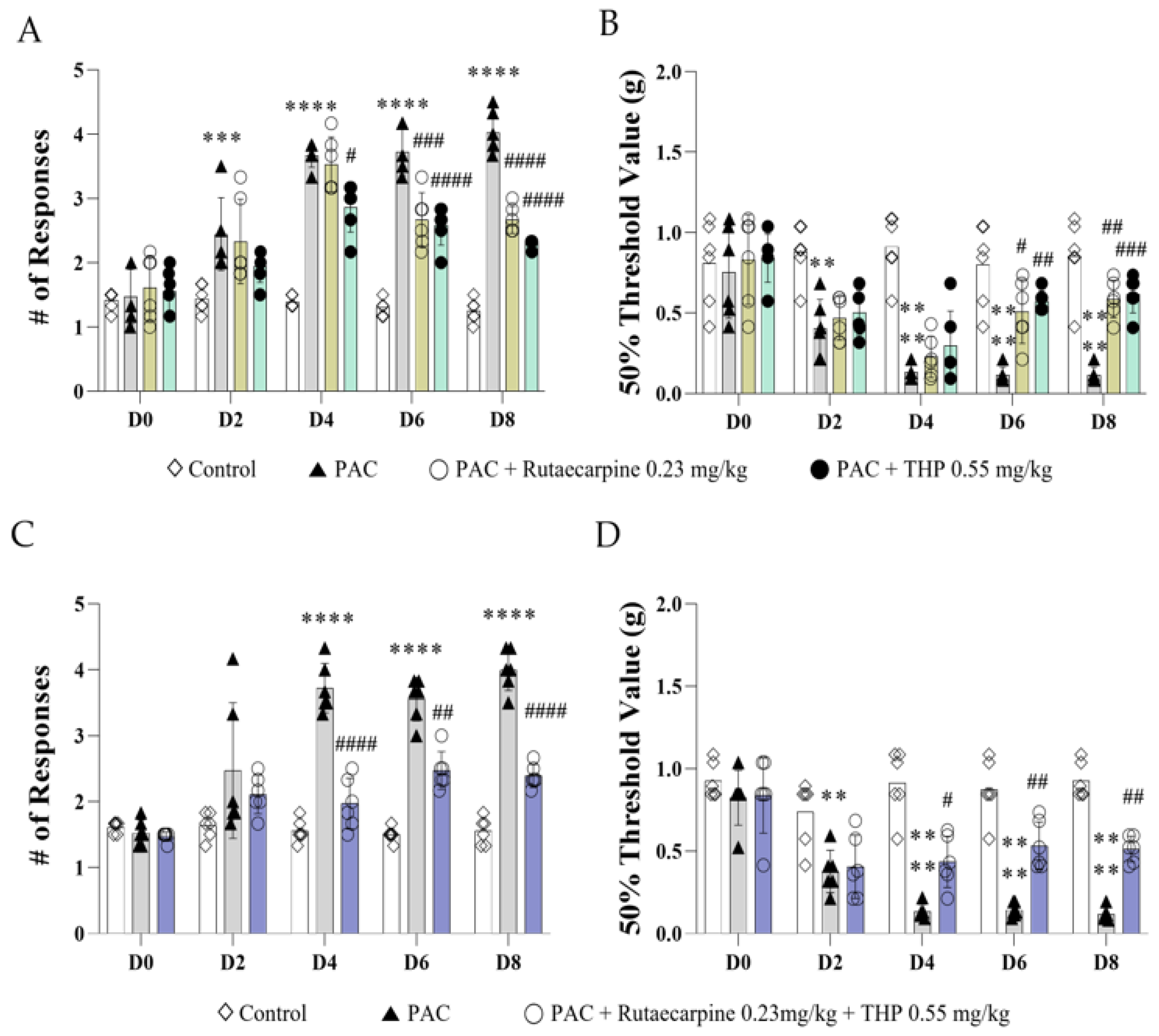

3.6. Analgesic Effects of Rutaecarpine, THP, and Their Combination on Paclitaxel-Induced Cold and Mechanical Allodynia in Mice

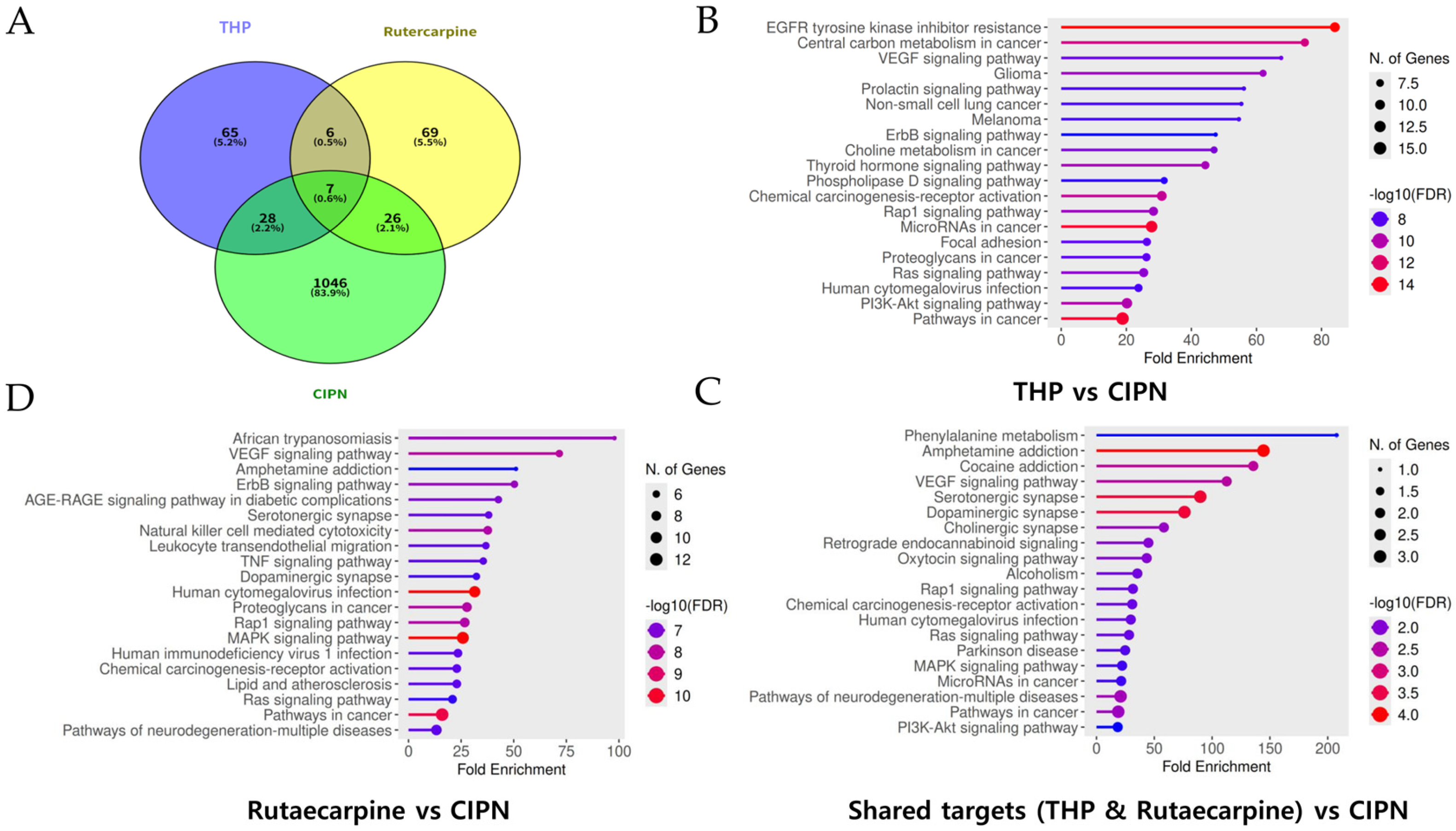

3.7. Integrated Analysis of Overlapping Targets and KEGG Pathway Enrichment for THP and Rutaecarpine in CIPN

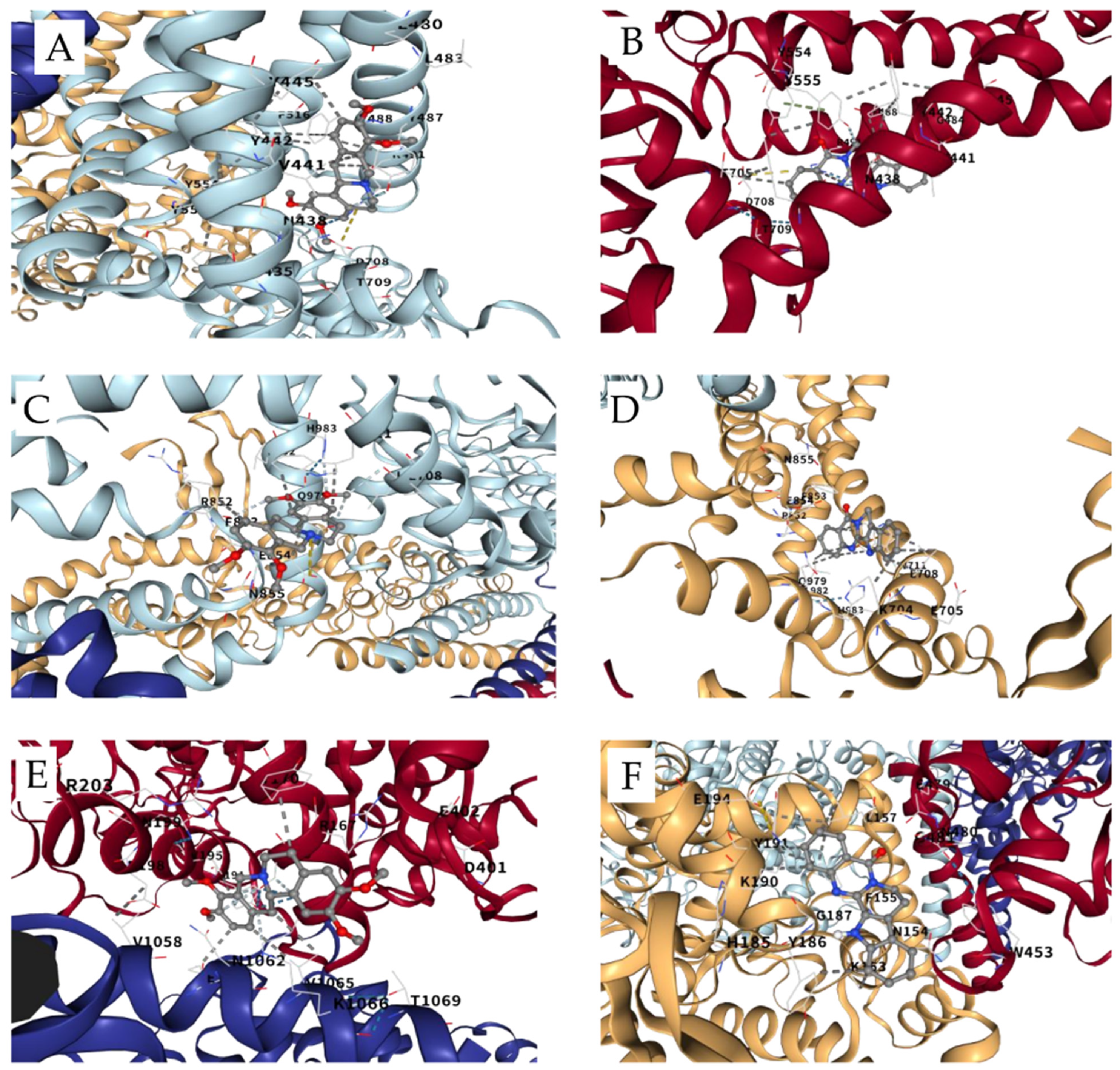

3.8. Docking Analysis of THP and Rutaecarpine on TRP Channels

3.9. In Silico ADMET Analysis of THP and Rutaecarpine

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Uhm, J.H.; Yung, W.K. Neurologic Complications of Cancer Therapy. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 1999, 1, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merskey, H.; Bogduk, N. Classification of chronic pain. Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Prepared by the International Association for the Study of Pain, Subcommittee on Taxonomy. Pain Suppl. 1986, 3, S1–S226. [Google Scholar]

- Woolf, C.J.; Mannion, R.J. Neuropathic pain: Aetiology, symptoms, mechanisms, and management. Lancet 1999, 353, 1959–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Min, D.; Lee, D.; Kim, W. Zingiber officinale Roscoe Rhizomes Attenuate Oxaliplatin-Induced Neuropathic Pain in Mice. Molecules 2021, 26, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Yoo, J.H.; Kim, S.K. Long-Lasting and Additive Analgesic Effects of Combined Treatment of Bee Venom Acupuncture and Venlafaxine on Paclitaxel-Induced Allodynia in Mice. Toxins 2020, 12, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efferth, T.; Koch, E. Complex interactions between phytochemicals. The multi-target therapeutic concept of phytotherapy. Curr. Drug Targets 2011, 12, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, N.; Park, S.; Kim, S.K. Analgesic effects of medicinal plants and phytochemicals on chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain through glial modulation. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2021, 9, e00819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.; Wang, M.; Gralow, J.; Dickler, M.; Cobleigh, M.; Perez, E.A.; Shenkier, T.; Cella, D.; Davidson, N.E. Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 2666–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, A.; Gray, R.; Perry, M.C.; Brahmer, J.; Schiller, J.H.; Dowlati, A.; Lilenbaum, R.; Johnson, D.H. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 2542–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verweij, J.; Clavel, M.; Chevalier, B. Paclitaxel (Taxol) and docetaxel (Taxotere): Not simply two of a kind. Ann. Oncol. 1994, 5, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, P.M.; Cata, J.P.; Cordella, J.V.; Burton, A.; Weng, H.-R. Taxol-induced sensory disturbance is characterized by preferential impairment of myelinated fiber function in cancer patients. Pain 2004, 109, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyriou, A.A.; Koltzenburg, M.; Polychronopoulos, P.; Papapetropoulos, S.; Kalofonos, H.P. Peripheral nerve damage associated with administration of taxanes in patients with cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2008, 66, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carozzi, V.A.; Canta, A.; Chiorazzi, A. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: What do we know about mechanisms? Neurosci. Lett. 2015, 596, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission, C. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China; China Medical Science Press: Beijing, China, 2020; p. 163e166. [Google Scholar]

- Alhassen, L.; Dabbous, T.; Ha, A.; Dang, L.H.L.; Civelli, O. The analgesic properties of Corydalis yanhusuo. Molecules 2021, 26, 7498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Lu, L. Chapter Twelve-Chinese Herbal Medicine for the Treatment of Drug Addiction. In International Review of Neurobiology; Zeng, B.-Y., Zhao, K., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; Volume 135, pp. 279–295. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, H.; Wu, L.; Li, L. Corydalis yanhusuo rhizoma extract reduces infarct size and improves heart function during myocardial ischemia/reperfusion by inhibiting apoptosis in rats. Phytother. Res. 2006, 20, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Yang, Y.; Mao, Z.; Wu, J.; Ren, D.; Zhu, B.; Qin, L. Processing and compatibility of Corydalis yanhusuo: Phytochemistry, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, and safety. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 1271953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, F.-J.; Ho, T.-J.; Cheng, C.-F.; Liu, X.; Tsang, H.; Lin, T.-H.; Liao, C.-C.; Huang, S.-M.; Li, J.-P.; Lin, C.-W.; et al. Effect of Chinese herbal medicine on stroke patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 200, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasvand, M.; Assadollahi, V.; Ambra, R.; Hedayati, E.; Kooti, W.; Peluso, I. Antiangiogenic Effect of Alkaloids. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 9475908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Yang, S.; Wang, K.; Bao, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Liu, H.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, T.; Yu, H. Alkaloids from Traditional Chinese Medicine against hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 120, 109543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Lu, D.; Chen, H.; Zhu, Y.; Xie, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Z. Tetrahydropalmatine induces the polarization of M1 macrophages to M2 to relieve limb ischemia-reperfusion-induced lung injury via inhibiting the TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling pathway. Drug Dev. Res. 2022, 83, 1362–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.J.; Cao, G.Y.; Jia, L.Y.; Zheng, G.; Zhang, L.; Sheng, P.; Xie, J.Z.; Zhang, C.F. Cardioprotective Effects of Tetrahydropalmatine on Acute Myocardial Infarction in Rats. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2022, 50, 1887–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Deng, J.; Wang, K.; Wang, A.; Chen, G.; Chen, Q.; Ye, M.; Wu, X.; Wang, X.; Lin, D. Tetrahydropalmatine promotes random skin flap survival in rats via the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 324, 117808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; He, M.; Chen, M.; Xu, Q.; Li, S.; Cui, Y.; Qiu, X.; Tian, W. Amelioration of Neuropathic Pain and Attenuation of Neuroinflammation Responses by Tetrahydropalmatine Through the p38MAPK/NF-κB/iNOS Signaling Pathways in Animal and Cellular Models. Inflammation 2022, 45, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Liu, M.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, Y.L.; Wang, Y. Tetrahydropalmatine Regulates BDNF through TrkB/CAM Interaction to Alleviate the Neurotoxicity Induced by Methamphetamine. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12, 3373–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Xie, L.; Song, J.; Li, X. Evodiamine: A review of its pharmacology, toxicity, pharmacokinetics and preparation researches. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 262, 113164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Huang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yi, J. Simultaneous determination of six bioactive compounds in Evodiae Fructus by high-performance liquid chromatography with diode array detection. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2014, 52, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Han, X.; Zhao, X.; Wang, C.; Li, Q.; Chen, X.; Bi, K. A sensitive liquid chromatographic-mass spectrometric method for simultaneous determination of dehydroevodiamine and limonin from Evodia rutaecarpa in rat plasma. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 401, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Tian, M.; Yuan, L.; Deng, H.; Wang, L.; Li, A.; Hou, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Analysis of E. rutaecarpa Alkaloids Constituents In Vitro and In Vivo by UPLC-Q-TOF-MS Combined with Diagnostic Fragment. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2016, 2016, 4218967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.J. Progress and future developing of the serum pharmacochemistry of traditional Chinese medicine. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2006, 31, 789–792, 835. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sheu, J.; Hung, W.; Wu, C.; Lee, Y.; Yen, M. Antithrombotic effect of rutaecarpine, an alkaloid isolated from Evodia rutaecarpa, on platelet plug formation in in vivo experiments. Br. J. Haematol. 2000, 110, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, J.-R.; Hung, W.-C.; Lee, Y.-M.; Yen, M.-H. Mechanism of inhibition of platelet aggregation by rutaecarpine, an alkaloid isolated from Evodia rutaecarpa. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1996, 318, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, J.-R.; Kan, Y.-C.; Hung, W.-C.; Su, C.-H.; Lin, C.-H.; Lee, Y.-M.; Yen, M.-H. The antiplatelet activity of rutaecarpine, an alkaloid isolated from Evodia rutaecarpa, is mediated through inhibition of phospholipase C. Thromb. Res. 1998, 92, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, J.; Li, P.; Wang, J.; Zhou, W.; Li, B.; Huang, C.; Li, P.; Guo, Z.; Tao, W.; Yang, Y.; et al. TCMSP: A database of systems pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. J. Cheminform 2014, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, D.E.; Blundell, T.L.; Ascher, D.B. pkCSM: Predicting Small-Molecule Pharmacokinetic and Toxicity Properties Using Graph-Based Signatures. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 4066–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelzer, G.; Rosen, N.; Plaschkes, I.; Zimmerman, S.; Twik, M.; Fishilevich, S.; Stein, T.I.; Nudel, R.; Lieder, I.; Mazor, Y.; et al. The GeneCards Suite: From Gene Data Mining to Disease Genome Sequence Analyses. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2016, 54, 1.30.1–1.30.33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Yang, K.; Fang, S.; Bu, D.; Li, H.; Sun, L.; Hu, H.; Gao, K.; Wang, W.; et al. SymMap: An integrative database of traditional Chinese medicine enhanced by symptom mapping. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D1110–D1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Liu, L.; Lei, S.; Li, Z.; Huo, P.; Wang, Z.; Dong, L.; Deng, W.; Bu, D.; Zeng, X.; et al. HERB 2.0: An updated database integrating clinical and experimental evidence for traditional Chinese medicine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D1404–D1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, D.; Zheng, G.; Wang, C.; Chen, Z.; Mao, T.; Gao, J.; Yan, Y.; Chen, X.; Ji, X.; Yu, J.; et al. HIT 2.0: An enhanced platform for Herbal Ingredients’ Targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D1238–D1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.T.; Kim, J.K.; Hwang, D.; Yoo, Y.; Lim, Y.H. Inhibitory effect of mulberroside A and its derivatives on melanogenesis induced by ultraviolet B irradiation. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 3038–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: Protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, d.W.; Sherman, B.T.; Lempicki, R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Gan, J.; Chen, S.; Xiao, Z.X.; Cao, Y. CB-Dock2: Improved protein-ligand blind docking by integrating cavity detection, docking and homologous template fitting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W159–W164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polomano, R.C.; Mannes, A.J.; Clark, U.S.; Bennett, G.J. A painful peripheral neuropathy in the rat produced by the chemotherapeutic drug, paclitaxel. Pain 2001, 94, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Authier, N.; Gillet, J.-P.; Fialip, J.; Eschalier, A.; Coudore, F. Description of a short-term Taxol®-induced nociceptive neuropathy in rats. Brain Res. 2000, 887, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M. Pathobiology of neuropathic pain. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 429, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, S.; Hu, C. Pharmacological Effects of Rutaecarpine as a Cardiovascular Protective Agent. Molecules 2010, 15, 1873–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Sun, J.; Li, W.; Zhang, S.; Yang, L.; Teng, Y.; Lv, K.; Liu, Y.; Su, Y.; Zhang, J. Analgesic effect of the main components of Corydalis yanhusuo (yanhusuo in Chinese) is caused by inhibition of voltage gated sodium channels. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 280, 114457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Luo, M.; Meng, D.; Pan, H.; Shen, H.; Shen, J.; Yao, M.; Xu, L. Tetrahydropalmatine exerts analgesic effects by promoting apoptosis and inhibiting the activation of glial cells in rats with inflammatory pain. Mol. Pain 2021, 17, 17448069211042117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Q.; Meng, X.; Wang, S. A comprehensive review on the chemical properties, plant sources, pharmacological activities, pharmacokinetic and toxicological characteristics of tetrahydropalmatine. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 890078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.W.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H.C.; Liu, J.; Chan, S.O.; Zhong, Y.F.; Zhang, T.Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xia, Y.Q.; et al. Roles of Thermosensitive Transient Receptor Channels TRPV1 and TRPM8 in Paclitaxel-Induced Peripheral Neuropathic Pain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slepicka, J.; Palecek, J. Glial Activation Enhances Spinal TRPV1 Receptor Sensitivity in a Paclitaxel Model of Neuropathic Pain. Physiol. Res. 2025, 74, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yin, C.; Li, X.; Liu, B.; Wang, J.; Zheng, X.; Shao, X.; Liang, Y.; Du, J.; Fang, J.; et al. Electroacupuncture Alleviates Paclitaxel-Induced Peripheral Neuropathic Pain in Rats via Suppressing TLR4 Signaling and TRPV1 Upregulation in Sensory Neurons. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamata, Y.; Kambe, T.; Chiba, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Kawakami, K.; Abe, K.; Taguchi, K. Paclitaxel induces upregulation of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 expression in the rat spinal cord. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, D.B.; Choi, W.; Kim, M.; Go, E.J.; Jeong, D.; Park, C.-K.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, H.; Suh, J.-W. Decursin Alleviates Mechanical Allodynia in a Paclitaxel-Induced Neuropathic Pain Mouse Model. Cells 2021, 10, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.; Binder, A.; Wasner, G. Neuropathic pain: Diagnosis, pathophysiological mechanisms, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2010, 9, 807–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ro, L.S.; Chang, K.H. Neuropathic pain: Mechanisms and treatments. Chang Gung Med. J. 2005, 28, 597–605. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, A.; Bennett, D. Neuroinflammation and the generation of neuropathic pain. Br. J. Anaesth. 2013, 111, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Conditions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Tetrahydropalmatine | Rutaecarpine | ||||

| Column | Ymc-Triart C18 | Ymc-Triart C18 | ||||

| Flow rate | 1.0 mL/min | 1.0 mL/min | ||||

| Injection volume | 10 μL | 10 μL | ||||

| UV detection | 254 nm | 240 nm | ||||

| Run time | 25 min | 25 min | ||||

| Tetrahydropalmatine | Rutaecarpine | Flow | ||||

| Time (min) | Aceto -nitrile | 0.1% Phosphoric acid | Time (min) | Aceto -nitrile | Water | mL/min |

| 0 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 65 | 35 | 1.0 |

| 15 | 70 | 30 | 15 | 65 | 35 | 1.0 |

| 17 | 100 | 0 | 17 | 100 | 0 | 1.0 |

| 20 | 100 | 0 | 19 | 100 | 0 | 1.0 |

| 21 | 75 | 25 | 21 | 65 | 35 | 1.0 |

| 25 | 75 | 25 | 25 | 65 | 35 | 1.0 |

| Target Receptor | PDB ID | Ligand | Binding Cavity | Vina Score (kcal/mol) | Affinity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRPV1 | 8GFA | THP | C2 | −9.4 | Strong |

| Rutaecarpine | C1 | −9.7 | Very Strong | ||

| TRPM8 | 8BDC | THP | C2 | −7.9 | Moderate |

| Rutaecarpine | C1 | −9.1 | Strong |

| Category | Model Name | THP | Rutaecarpine | Threshold/Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | Intestinal absorption (human) | 93.10% | 97.29% | High absorption (>30%) |

| Caco-2 permeability | 0.68 | 1.26 | High permeability (>0.90) | |

| Distribution | BBB permeability (logBB) | 0.17 | 0.67 | Crosses BBB (>−1) |

| CNS permeability (logPS) | −1.83 | −1.80 | Penetrates CNS (>−2.0) | |

| Metabolism | CYP3A4 substrate | Yes | Yes | Metabolized by CYP3A4 |

| Toxicity | AMES toxicity | No | Yes | THP is non-mutagenic |

| hERG I inhibitor | No | No | Low cardiotoxicity risk | |

| Hepatotoxicity | Yes | Yes | Liver toxicity risk |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Park, K.-T.; Yun, H.; Kang, J.; Lee, J.-C.; Kim, W. Plant-Derived Secondary Metabolites Tetrahydropalmatine and Rutaecarpine Alleviate Paclitaxel-Induced Neuropathic Pain via TRPV1 and TRPM8 Modulation. Metabolites 2026, 16, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010046

Park K-T, Yun H, Kang J, Lee J-C, Kim W. Plant-Derived Secondary Metabolites Tetrahydropalmatine and Rutaecarpine Alleviate Paclitaxel-Induced Neuropathic Pain via TRPV1 and TRPM8 Modulation. Metabolites. 2026; 16(1):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010046

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Keun-Tae, Hyesang Yun, Juyeol Kang, Jae-Chul Lee, and Woojin Kim. 2026. "Plant-Derived Secondary Metabolites Tetrahydropalmatine and Rutaecarpine Alleviate Paclitaxel-Induced Neuropathic Pain via TRPV1 and TRPM8 Modulation" Metabolites 16, no. 1: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010046

APA StylePark, K.-T., Yun, H., Kang, J., Lee, J.-C., & Kim, W. (2026). Plant-Derived Secondary Metabolites Tetrahydropalmatine and Rutaecarpine Alleviate Paclitaxel-Induced Neuropathic Pain via TRPV1 and TRPM8 Modulation. Metabolites, 16(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010046