A Comprehensive Review on Medium- and Long-Chain Fatty Acid-Derived Metabolites: From Energy Sources to Metabolic Signals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. LMFAs in Gut: Bioconversion of Dietary Fats and Prediction of Metabolism in Gut

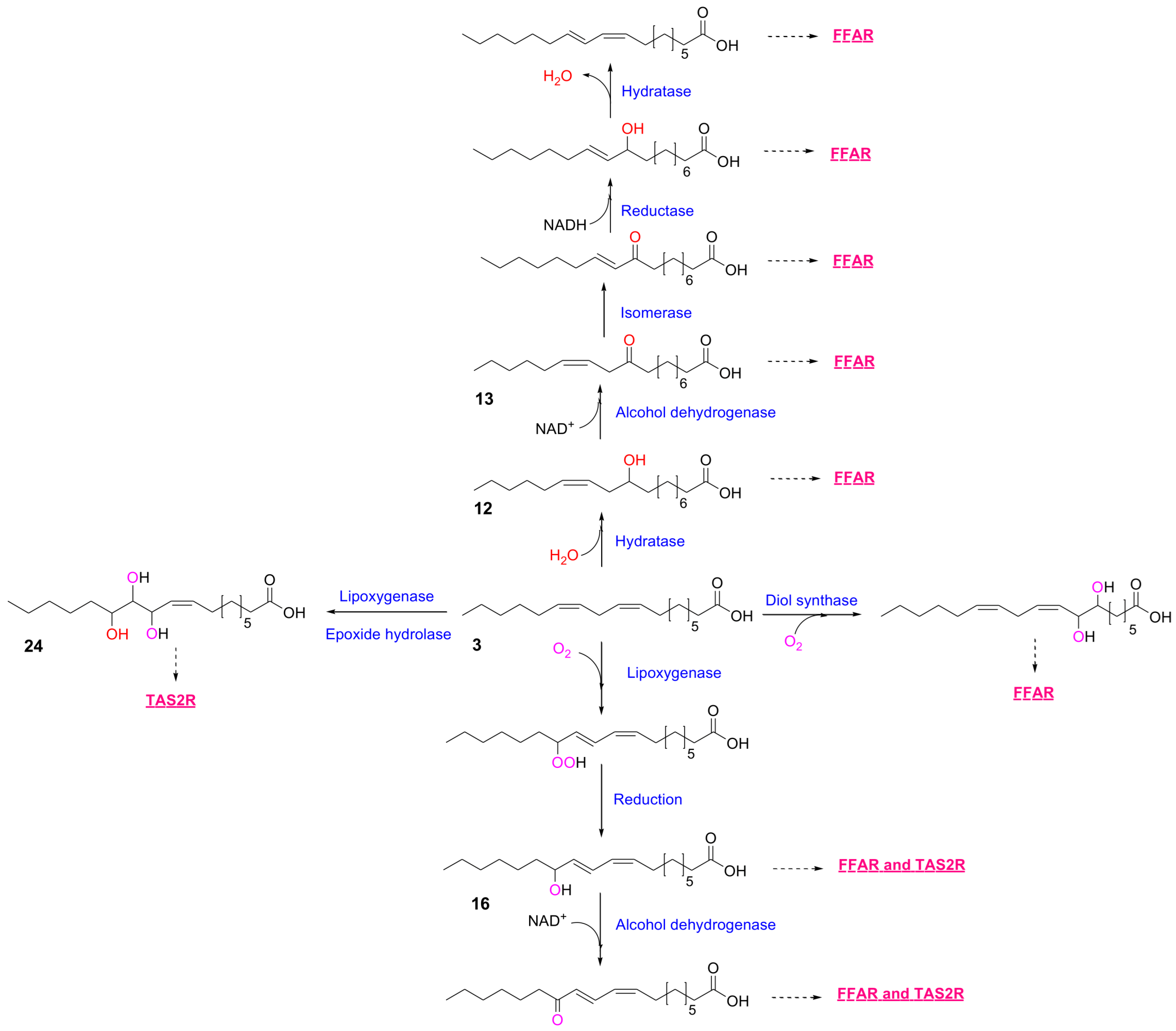

2.1. Digestion and Biotransformation of Dietary Fats

2.2. In Silico Predictions of MLFA Metabolites-Receptor Interactions

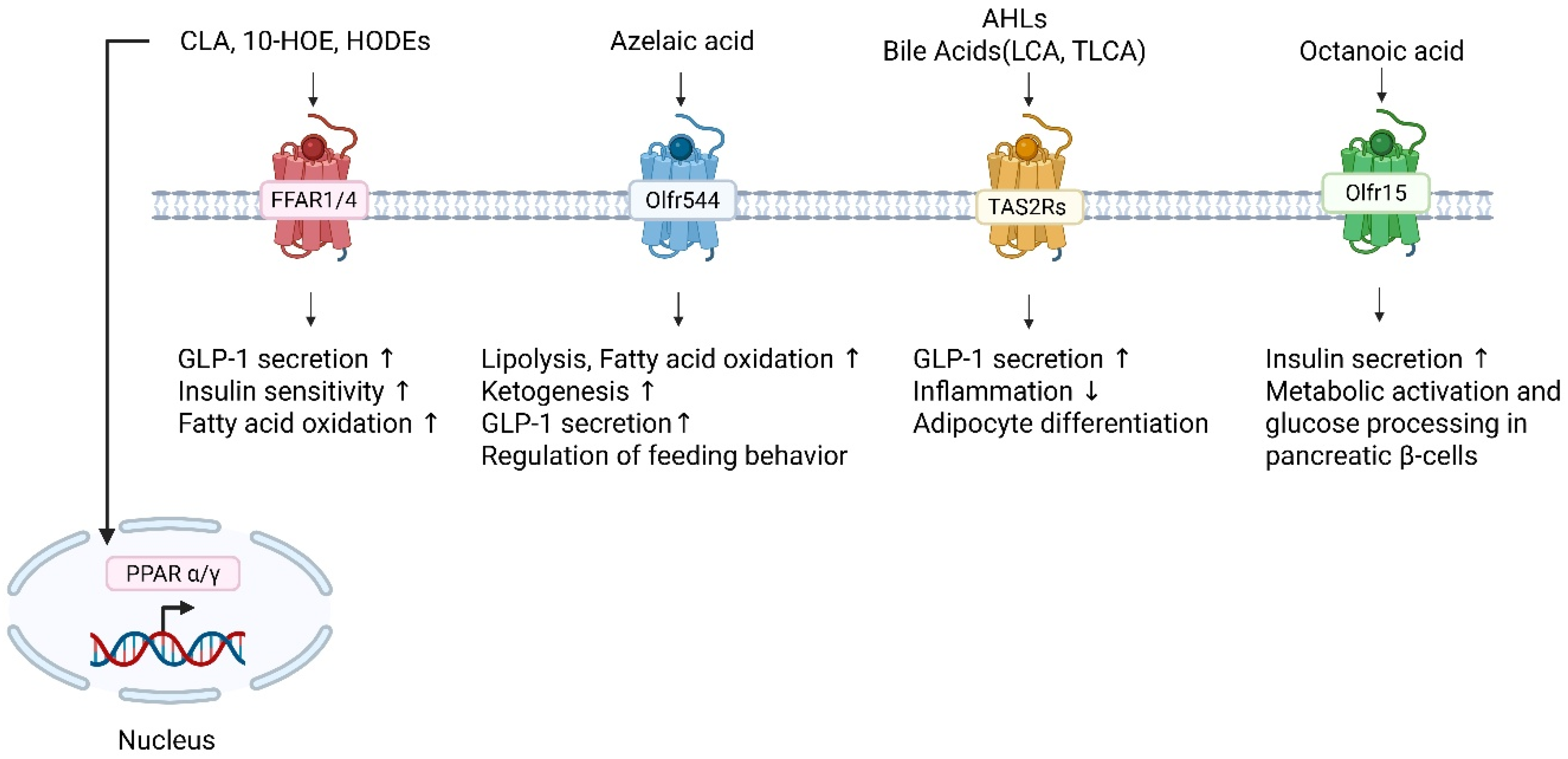

2.3. Chemosensory Receptors as Novel Fatty Acid Targets: Expanding the Landscape of Lipid Signaling

2.3.1. Olfactory Receptors as Metabolic Sensors of Fatty Acids

2.3.2. Bitter Taste Receptors as Peripheral Sentinels for Fatty Acid Metabolites

3. Perspectives and Therapeutic Potential

3.1. Chemosensory-Metabolic Integration of Fatty Acid Metabolites

3.2. Microbiome as a Metabolic Signaling Hub

3.3. Translational Opportunities Methodological Challenges

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghislain, J.; Poitout, V. Targeting Lipid GPCRs to Treat Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus—Progress and Challenges. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2021, 17, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, I.; Ichimura, A.; Ohue-Kitano, R.; Igarashi, M. Free Fatty Acid Receptors in Health and Disease. Physiol. Rev. 2020, 1, 171–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaigne, D.; Butruille, L.; Staels, B. PPAR Control of Metabolism and Cardiovascular Functions. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 809–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancox, J.C. Cardiac Ion Channel Modulation by the Hypoglycaemic Agent Rosiglitazone. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 496–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szentandrassy, N.; Harmati, G.; Barandi, L.; Simko, J.; Horvath, B.; Magyar, J.; Banyasz, T.; Lorincz, I.; Szebeni, A.; Kecskemeti, V.; et al. Effects of Rosiglitazone on the Configuration of Action Potentials and Ion Currents in Canine Ventricular Cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedrington, M.S.; Davis, S.N. Discontinued in 2013: Diabetic Drugs. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2014, 23, 1703–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monicah, A.; Otieno, J.S.; Lam, W.; Ghosh, A.; Player, M.R.; Pocai, A.; Salter, R.; Simic, D.; Skaggs, H.; Singh, B.; et al. Fasiglifam (TAK-875): Mechanistic Investigation and Retrospective Identification of Hazards for Drug Induced Liver Injury. Toxicol. Sci. 2017, 163, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagatake, T.; Kunisawa, J. Emerging Roles of Metabolites of ω3 and ω6 Essential Fatty Acids in the Control of Intestinal Inflammation. Int. Immunol. 2019, 31, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinninella, E.; Costantini, L. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids as Prebiotics: Innovation or Confirmation? Foods 2022, 11, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishino, S.; Takeuchi, M.; Park, S.B.; Hirata, A.; Kitamura, N.; Kunisawa, J.; Kiyono, H.; Iwamoto, R.; Isobe, Y.; Arita, M.; et al. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Saturation by Gut Lactic Acid Bacteria Affecting Host Lipid Composition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 17808–17813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, M.; Shimizu, M.; Lu, P.; Takahashi, Y.; Yamauchi, Y.; Sato, S.; Kiyono, H.; Kishino, S.; Ogawa, J.; Nagata, K. Lactic Acid Bacteria–derived γ-linolenic Acid Metabolites Are PPARδ Ligands That Reduce Lipid Accumulation in Human Intestinal Organoids. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, M.; Nagata, K.; Takeshita, R.; Ito, N.; Noguchi, S.; Minamikawa, N.; Kodama, N.; Yamamoto, A.; Yashiro, T.; Hachisu, M.; et al. The Gut Lactic Acid Bacteria Metabolite, 10-oxo-cis-6,trans-11-octadecadienoic Acid, Suppresses Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Mice by Modulating the NRF2 Pathway and GPCR-signaling. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1374425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, J.; Igarashi, M.; Watanabe, K.; Karaki, S.-I.; Mukouyama, H.; Kishino, S.; Li, X.; Ichimura, A.; Irie, J.; Sugimoto, Y.; et al. Gut Microbiota Confers Host Rresistance to Obesity by Metabolizing Dietary Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Depoortere, I.; Hatt, H. Therapeutic Potential of Ectopic Olfactory and Taste Receptors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 116–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirasawa, A.; Tsumaya, K.; Awaji, T.; Katsuma, S.; Adachi, T.; Yamada, M.; Sugimoto, Y.; Miyazaki, S.; Tsujimoto, G. Free Fatty Acids Regulate Gut Incretin Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Secretion Through GPR120. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gläser, P.; Mittermeier-Kleßinger, V.K.; Spaccasassi, A.; Hofmann, T.; Dawid, C. Quantification and Bitter Taste Contribution of Lipids and Their Oxidation Products in Pea-protein Isolates (Pisum sativum L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 8768–8776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canaan, S.; Roussel, A.; Verger, R.; Cambillau, C. Gastric Lipase: Crystal Structure and Activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1441, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvijanovic, N.; Isaacs, N.J.; Rayner, C.K.; Feinle-Bisset, C.; Young, R.L.; Little, T.J. Duodenal Fatty Acid Sensor and Transporter Expression Following Acute Fat Exposure in Healthy Lean Humans. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, V.B.; Gribble, F.M.; Reimann, F. Free Fatty Acid Receptors in Enteroendocrine Cells. Endocrinol 2018, 159, 2826–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Pedersen, O. Gut Microbiota in Human Metabolic Health and Disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, S.V.; Pedersen, O. The Human Intestinal Microbiome in Health and Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2369–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, J.; Slack, E.; Foster, K.R. Host Control of the Microbiome: Mechanisms, Evolution, and Disease. Science 2024, 385, eadi3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabke, K.; Hendrick, G.; Devkota, S. The Gut Microbiome and Metabolic Syndrome. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 4050–4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, T.; Kim, Y.I.; Furuzono, T.; Takahashi, N.; Yamakuni, K.; Yang, H.E.; Li, Y.; Ohue, R.; Nomura, W.; Sugawara, T.; et al. 10-oxo-12(Z)-octadecenoic Acid, a Linoleic Acid Metabolite Produced by Gut Lactic Acid Bacteria, Potently Activates PPARγ and Stimulates Adipogenesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 459, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salsinha, A.S.; Pimentel, L.L.; Fontes, A.L.; Gomes, A.M.; Rodríguez-Alcalá, L.M. Microbial Production of Conjugated Linoleic Acid and Conjugated Linolenic Acid Relies on a Multienzymatic System. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2018, 82, e00019-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Chen, H.; Gu, Z.; Tian, F.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C.; Chen, Y.Q.; Chen, W.; Zhang, H. Synthesis of Conjugated Linoleic Acid by the Linoleate Isomerase Complex in Food-derived Lactobacilli. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 117, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prem, S.; Helmer, C.P.O.; Dimos, N.; Himpich, S.; Brück, T.; Garbe, D.; Loll, B. Towards an Understanding of Oleate Hydratases and Their Application in Industrial Processes. Microb. Cell Fact. 2022, 21, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, M.; Kishino, S.; Park, S.B.; Hirata, A.; Kitamura, N.; Saika, A.; Ogawa, J. Efficient Enzymatic Production of Hydroxy Fatty Acids by Linoleic Acid Δ9 Hydratase from Lactobacillus plantarum AKU 1009a. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 120, 1282–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Anaya, J.; Hernández-Santoyo, A. Functional Characterization of a Fatty Acid Double-bond Hydratase from Lactobacillus plantarum and Its Interaction with Biosynthetic Membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1848, 3166–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.X.; Xiong, Z.Q.; Wang, G.Q.; Wang, L.F.; Xia, Y.J.; Song, X.; Ai, L.Z. LysR Family Regulator LttR Controls Production of Conjugated Linoleic Acid in Lactobacillus plantarum by Directly Activating the cla Operon. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e02798-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Chung, M.; Kim, J.; Lee, Y.; Lee, S.J.; Park, J.B. Functionalization of Plant Oil-Derived Fatty Acids into Di- and Trihydroxy Fatty Acids by Using a Linoleate Diol Synthase as a Key Enzyme. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 19576–19586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Liang, N.Y.; Curtis, J.M.; Gänzle, M.G. Characterization of Linoleate 10-Hydratase of Lactobacillus plantarum and Novel Antifungal Metabolites. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M.; Takahashi, N.; Matsuda, Y.; Sato, K.; Yokoji, M.; Sulijaya, B.; Maekawa, T.; Ushiki, T.; Mikami, Y.; Hayatsu, M.; et al. A Bacterial Metabolite Ameliorates Periodontal Pathogen-induced Gingival Epithelial Barrier Disruption via GPR40 Signaling. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, J.; Mizukure, T.; Park, S.B.; Kishino, S.; Kimura, I.; Hirano, K.; Bergamo, P.; Rossi, M.; Suzuki, T.; Arita, M.; et al. A Gut Microbial Metabolite of Linoleic Acid, 10-hydroxy-cis-12-octadecenoic Acid, Ameliorates Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Impairment Partially via GPR40-MEK-ERK Pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 2902–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.; Woo, J.-M.; Shin, J.; Chung, M.; Seo, E.-J.; Lee, S.-J.; Park, J.-B. Unveiling the Biological Activities of the Microbial Long Chain Hydroxy Fatty Acids as Dual Agonists of GPR40 and GPR120. Food Chem. 2025, 465, 142010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.-Y.; Lee, M.-J.; Lee, J.-H.; You, J.W.; Oh, D.-K.; Park, J.-B. Exploring the Fatty Acid Double Bond Hydration Activities of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus strains. Food Biosci. 2024, 57, 103571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, S.; De Simeis, D.; Castagna, A.; Valentino, M. The Fatty-acid Hydratase Activity of the Most Common Probiotic Microorganisms. Catalysts 2020, 10, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.-K.; Lee, T.-E.; Lee, J.; Shin, K.-C.; Park, J.-B. Biocatalytic Oxyfunctionalization of Unsaturated Fatty Acids to Oxygenated Chemicals via Hydroxy Fatty Acids. Biotechnol. Adv. 2025, 79, 108510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, S.; De Simeis, D.; Marzorati, S.; Valentino, M. Oleate Hydratase from Lactobacillus rhamnosus ATCC 53103: A FADH2-Dependent Enzyme with Remarkable Industrial Potential. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.J.; Shin, K.C.; Oh, D.K. Production of 10-hydroxy-12,15(Z,Z)-octadecadienoic Acid from α-linolenic Acid by Permeabilized Cells of Recombinant Escherichia coli Expressing the Oleate Hydratase Gene of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Biotechnol. Lett. 2013, 35, 1487–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedoorn, P.L.; Hollmann, F.; Hanefeld, U. Novel Oleate Hydratases and Potential Biotechnological Applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 6159–6172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, A.; Kishino, S.; Park, S.B.; Takeuchi, M.; Kitamura, N.; Ogawa, J. A Novel Unsaturated Fatty Acid Hydratase toward C16 to C22 Fatty Acids from Lactobacillus acidophilus. J. Lipid Res. 2015, 56, 1340–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.T. Production of Hydroxy Fatty Acids from Unsaturated Fatty Acids by Flavobacterium sp. DS5 Hydratase, a C-10 Positional- and cis-Unsaturation-specific Enzyme. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1995, 72, 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolterfoht, H.; Rinnofner, C.; Winkler, M.; Pichler, H. Recombinant Lipoxygenases and Hydroperoxide Lyases for the Synthesis of Green Leaf Volatiles. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 13367–13392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, R.; Hausmann, M.; Spöttl, T.; Gruber, M.; Bull, A.W.; Menzel, K.; Vogl, D.; Herfarth, H.; Schölmerich, J.; Falk, W.; et al. 13-Oxo-ODE is an Endogenous Ligand for PPARgamma in Human Colonic Epithelial Cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2007, 74, 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vangaveti, V.; Baune, B.T.; Kennedy, R.L. Hydroxyoctadecadienoic Acids: Novel Regulators of Macrophage Differentiation and Atherogenesis. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 1, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.R.; Oh, D.K. Production of Hydroxy Fatty Acids by Microbial Fatty Acid-hydroxylation Enzymes. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013, 31, 1473–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moya-Camarena, S.Y.; Vanden Heuvel, J.P.; Blanchard, S.G.; Leesnitzer, L.A.; Belury, M.A. Conjugated Linoleic Acid is a Potent Naturally Occurring Ligand and Activator of PPARalpha. J. Lipid Res. 1999, 40, 1426–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassaganya-Riera, J.; Reynolds, K.; Martino-Catt, S.; Cui, Y.; Hennighausen, L.; Gonzalez, F.; Rohrer, J.; Benninghoff, A.U.; Hontecillas, R. Activation of PPAR gamma and delta by Conjugated Linoleic Acid Mediates Protection from Experimental Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology 2004, 127, 777–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.S.; Koh, I.U.; Jung, M.H.; Song, J. Effects of Three Different Conjugated Linoleic Acid Preparations on Insulin Signalling, Fat Oxidation and Mitochondrial Function in Rats Fed a High-Fat Diet. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 98, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, K.; Inoue, N.; Wang, Y.M.; Yanagita, T. Conjugated Linoleic Acid Enhances Plasma Adiponectin Level and Alleviates Hyperinsulinemia and Hypertension in Zucker Diabetic Fatty (fa/fa) Rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 310, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCloskey, A.G.; Miskelly, M.G.; Flatt, P.R.; McKillop, A.M. Pharmacological Potential of Novel Agonists for FFAR4 on Islet and Enteroendocrine Cell Function and Glucose Homeostasis. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 142, 105104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, R.; Yano, T.; Ogawa, J.; Tanaka, N.; Toda, N.; Yoshida, M.; Takano, R.; Inoue, M.; Honda, T.; Kume, S.; et al. Potentiation of Insulin Secretion and Improvement of Glucose Intolerance by Combining a Novel G Protein-Coupled Receptor 40 Agonist DS-1558 with Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 737, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankoda, A.; Harada, N.; Iwasaki, K.; Yamane, S.; Murata, Y.; Shibue, K.; Thewjitcharoen, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Harada, T.; Kanemaru, Y.; et al. Long-Chain Free Fatty Acid Receptor GPR120 Mediates Oil-Induced GIP Secretion Through CCK in Male Mice. Endocrinology 2017, 158, 1172–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hira, T.; Ogasawara, S.; Yahagi, A.; Kamachi, M.; Li, J.; Nishimura, S.; Sakaino, M.; Yamashita, T.; Kishino, S.; Ogawa, J.; et al. Novel Mechanism of Fatty Acid Sensing in Enteroendocrine Cells: Specific Structures in Oxo-Fatty Acids Produced by Gut Bacteria Are Responsible for CCK Secretion in STC-1 Cells via GPR40. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, e1800146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodaley, R.; Smith, D.M.; Tough, I.R.; Schindler, M.; Cox, H.M. Agonism of Free Fatty Acid Receptors 1 and 4 Generates Peptide YY-mediated Inhibitory Responses in Mouse Colon. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 4508–4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tough, I.R.; Moodaley, R.; Cox, H.M. Enteroendocrine Cell-derived Peptide YY Signalling is Stimulated by Pinolenic Acid or Intralipid and Involves Coactivation of Fatty Acid Receptors FFA1, FFA4 and GPR119. Neuropeptides 2024, 108, 102477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagatake, T.; Kishino, S.; Urano, E.; Murakami, H.; Kitamura, N.; Konishi, K.; Ohno, H.; Tiwari, P.; Morimoto, S.; Node, E.; et al. Intestinal Microbe-dependent ω3 Lipid Metabolite α-KetoA Prevents Inflammatory Diseases in Mice and Cynomolgus macaques. Mucosal Immunol. 2022, 15, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagatake, T.; Shibata, Y.; Morimoto, S.; Node, E.; Sawane, K.; Hirata, S.I.; Adachi, J.; Abe, Y.; Isoyama, J.; Saika, A.; et al. 12-Hydroxyeicosapentaenoic Acid Inhibits Foam Cell Formation and Ameliorates High-fat Diet-induced Pathology of Atherosclerosis in Mice. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, L.; Tontonoz, P.; Alvarez, J.G.; Chen, H.; Evans, R.M. Oxidized LDL Regulates Macrophage Gene Expression Through Ligand Activation of PPARgamma. Cell 1998, 93, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umeno, A.; Sakashita, M.; Sugino, S.; Murotomi, K.; Okuzawa, T.; Morita, N.; Tomii, K.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Yamasaki, K.; Horie, M.; et al. Comprehensive Analysis of PPARγ Agonist Activities of Stereo-, Regio-, and Enantio-isomers of Hydroxyoctadecadienoic Acids. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20193767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.J.; Wiater, M.F.; Wang, Q.; Wank, S.; Ritter, S. Deletion of GPR40 Fatty Acid Receptor Gene in Mice Blocks Mercaptoacetate-induced Feeding. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2016, 310, R968–R974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mietlicki-Baase, E.G.; Ortinski, P.I.; Rupprecht, L.E.; Olivos, D.R.; Alhadeff, A.L.; Pierce, R.C.; Hayes, M.R. The Food Intake-suppressive Effects of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Signaling in the Ventral Tegmental Area Are Mediated by AMPA/Kainate Receptors. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 305, E1367–E1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munakata, Y.; Yamada, T.; Imai, J.; Takahashi, K.; Tsukita, S.; Shirai, Y.; Kodama, S.; Asai, Y.; Sugisawa, T.; Chiba, Y.; et al. Olfactory Receptors Are Expressed in Pancreatic β-cells and Promote Glucose-stimulated Insulin Secretion. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leem, J.; Shim, H.M.; Cho, H.; Park, J.H. Octanoic Acid Potentiates Glucose-stimulated Insulin Secretion and Expression of Glucokinase Through the Olfactory Receptor in Pancreatic β-cells. Biochem. Bioph. Res. Comm. 2018, 503, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenna, E.; Colombo, D.; Di Lecce, G.; Gatti, F.G.; Ghezzi, M.C.; Tentori, F.; Tessaro, D.; Viola, M. Conversion of Oleic Acid into Azelaic and Pelargonic Acid by a Chemo-Enzymatic Route. Molecules 2020, 25, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.-W.; Seo, J.-H.; Oh, D.-K.; Bornscheuer, U.T.; Park, J.-B. Design and Engineering of Whole-cell Biocatalytic Cascades for the Valorization of Fatty Acids. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, D.L.; Madduri, K.M.; Eshoo, M.; Wilson, C.R. Identification and characterization of the CYP52 family of Candida tropicalis ATCC 20336, important for the conversion of fatty acids and alkanes to α,ω-dicarboxylic acids. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2003, 69, 5983–5991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranea-Robles, P.; Houten, S.M. The Biochemistry and Physiology of Long-chain Dicarboxylic Acid Metabolism. Biochem. J. 2023, 480, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardwick, J.P. Cytochrome P450 omega-Hydroxylase (CYP4) Function in Fatty Acid Metabolism and Metabolic Diseases. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2008, 75, 2263–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gérard, P. The Crosstalk between the Gut Microbiota and Lipids. OCL 2020, 27, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devillard, E.; McIntosh, F.M.; Duncan, S.H.; Wallace, R.J. Metabolism of Linoleic Acid by Human Gut Bacteria: Different Routes for Biosynthesis of Conjugated Linoleic Acid. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 2566–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashbee, H.R. Update on the Genus Malassezia. Med. Mycol. 2007, 45, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Nuland, Y.M.; de Vogel, F.A.; Eggink, G.; Weusthuis, R.A. Expansion of the ω-Oxidation System AlkBGTL of Pseudomonas putida GPo1 with AlkJ and AlkH Results in Exclusive mono-esterified Dicarboxylic Acid Production in E. coli. Microb. Biotechnol. 2017, 10, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnik, B.C.; Schmitz, G. Are Therapeutic Effects of Antiacne Agents Mediated by Activation of FoxO1 and Inhibition of mTORC1? Exp. Dermatol. 2013, 22, 502–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briganti, S.; Flori, E.; Mastrofrancesco, A.; Kovacs, D.; Camera, E.; Ludovici, M.; Cardinali, G.; Picardo, M. Azelaic Acid Reduced Senescence-like Phenotype in Photo-irradiated Human Dermal Fibroblasts: Possible Implication of PPARγ. Exp. Dermatol. 2013, 22, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrofrancesco, A.; Ottaviani, M.; Aspite, N.; Cardinali, G.; Izzo, E.; Graupe, K.; Zouboulis, C.C.; Camera, E.; Picardo, M. Azelaic Acid Modulates the Inflammatory Response in Normal Human Keratinocytes Through PPARgamma Activation. Exp. Dermatol. 2010, 19, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thach, T.T.; Wu, C.; Hwang, K.Y.; Lee, S.J. Azelaic Acid Induces Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Skeletal Muscle by Activation of Olfactory Receptor 544. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Hwang, S.H.; Jia, Y.; Choi, J.; Kim, Y.J.; Choi, D.; Pathiraja, D.; Choi, I.G.; Koo, S.H.; Lee, S.J. Olfactory Receptor 544 Reduces Adiposity by Steering Fuel Preference toward Fats. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 4118–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Jeong, M.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, G.; Kim, J.S.; Cheong, Y.E.; Kang, H.; Cho, C.H.; Kim, J.; Park, M.K.; et al. Activation of Ectopic Olfactory Receptor 544 Induces GLP-1 Secretion and Regulates Gut Inflammation. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1987782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, M.; Wu, C.; Shin, J.; Lee, S.-J. Azelaic Acid Induces Cholecystokinin Secretion and Reduces Fat-rich Food Preference via Activation of Olfr544. J. Funct. Foods 2023, 105, 105577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudel, F.; Stephan, D.; Landel, V.; Sicard, G.; Féron, F.; Guiraudie-Capraz, G.A.-O. Expression of the Cerebral Olfactory Receptors Olfr110/111 and Olfr544 Is Altered During Aging and in Alzheimer’s Disease-Like Mice. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 2057–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamila, T.; Agnieszka, K. An Update on Extra-Oral Bitter Taste Rreceptors. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 440. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, F.; Steuer, A.; Di Pizio, A.; Behrens, M. Physiological Activation of Human and Mouse Bitter Taste Receptors by Bile Acids. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, S.; Ziegler, F.; Lang, T.; Steuer, A.; Di Pizio, A.; Behrens, M. Membrane-bound Chemoreception of Bitter Bile Acids and Peptides is Mediated by the Same Subset of Bitter Taste Receptors. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Gumpper, R.H.; Liu, Y.; Kocak, D.D.; Xiong, Y.; Cao, C.; Deng, Z.J.; Krumm, B.E.; Jain, M.K.; Zhang, S.C.; et al. Bitter Taste Receptor Activation by Cholesterol and an Intracellular Tastant. Nature 2024, 630, E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lossow, K.; Hubner, S.; Roudnitzky, N.; Slack, J.P.; Pollastro, F.; Behrens, M.; Meyerhof, W. Comprehensive Analysis of Mouse Bitter Taste Receptors Reveals Different Molecular Receptive Ranges for Orthologous Receptors in Mice and Humans. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 15358–15377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbagallo, M.; Dominguez, L.J.; Licata, G.; Shan, J.; Bing, L.; Karpinski, E.; Pang, P.K.T.; Resnick, L.M. Vascular Effects of Progesterone—Role of Cellular Calcium Regulation. Hypertension 2001, 37, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloxham, C.J.; Foster, S.R.; Thomas, W.G. A Bitter Taste in Your Heart. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.C.; Chi, L.; Tu, P.C.; Lai, Y.J.; Liu, C.W.; Ru, H.Y.; Lu, K. Detection of Gut Microbiota and Pathogen Produced N-acyl Homoserine in Host Circulation and Tissues. Npj Biofilms Microbiol. 2021, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Q.Q.; Guo, K.; Lin, P.; Wang, Z.H.; Qin, S.G.; Gao, P.; Combs, C.; Khan, N.; Xia, Z.W.; Wu, M. Bitter Receptor TAS2R138 Facilitates Lipid Droplet Degradation in Neutrophils during Infection. Signal Transduct. Tar. 2021, 6, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coquant, G.; Grill, J.P.; Seksik, P. Impact of-Acyl-Homoserine Lactones, Quorum Sensing Molecules, on Gut Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, S.; Kato, E. TAS2R Expression Profile in Brown Adipose, White Adipose, Skeletal Muscle, Small Intestine, Liver and Common Cell Lines Derived from Mice. Gene. Rep. 2020, 20, 100763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmon, M.; Pollastro, F.; Fresu, L.G. The Complex Journey of the Calcium Regulation Downstream of TAS2R Activation. Cells 2022, 11, 3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, C.A.; Pilic, L.; McGrigor, E.; Brown, M.; Easton, I.J.; Kean, J.N.; Sarel, V.; Wehliye, Y.; Davis, N.; Hares, N.; et al. The Associations Between Bitter and Fat Taste Sensitivity, and Dietary Fat Intake: Are They Impacted by Genetic Predisposition? Chem. Senses 2021, 46, BJAB029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, W.L. Therapeutic potential of Targeting Intestinal Bitter Taste Receptors in Diabetes Associated with Dyslipidemia. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 170, 105693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Ko, H.M.; Jee, W.; Kim, H.; Chung, W.S.; Jang, H.J. Isosinensetin Stimulates Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Secretion via Activation of hTAS2R50 and the Gβγ-Mediated Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Fatty Acid Ligand | EC50 (µM) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPR40 | GPR120 | ||

| 1 | stearic acid (18:0) | ND | ND |

| 2 | oleic acid (18:1, n-9) | 27.5 | 17.3 |

| 3 | linoleic acid (18:2, n-6) | 12.1 | 7.02 |

| 4 | γ-linolenic acid (18:3, n-6) | 3.18 | 2.01 |

| 5 | α-linolenic acid (18:3, n-3) | 2.27 | 2.04 |

| 6 | arachidonic acid (20:4, n-6) | 9.54 | 8.20 |

| 7 | eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5, n-3) | 5.44 | 2.73 |

| 8 | docosahexaenoic acid (22:6, n-3) | 2.42 | 0.91 |

| 9 | 8-hydroxyoctadec-9Z-enoic acid | 12.7 | 7.66 |

| 10 | 9-hydroxyoctadeca-10E,12Z-dienoic acid | 3.04 | 3.04 |

| 11 | 10-hydroxyoctadecanoic acid | ND | ND |

| 12 | 10-hydroxyoctadec-12Z-enoic acid | 2.18 | 2.30 |

| 13 | 10-keto-octadec-12Z-enoic acid | 3.61 | 3.40 |

| 14 | 12-hydroxyoctadec-9Z-enoic acid | 11.7 | 3.58 |

| 15 | 13-hydroxyoctadec-9Z-enoic acid | 9.83 | 2.04 |

| 16 | 13-hydroxyoctadeca-9Z,11E-dienoic acid | 6.90 | 1.07 |

| 17 | 5,8-dihydroxyoctadec-9Z-enoic acid | 9.77 | 2.10 |

| 18 | 6,8-dihydroxyoctadec-9Z-enoic acid | 1.50 | 2.51 |

| 19 | 7,8-dihydroxyoctadec-9Z-enoic acid | 1.28 | 2.69 |

| 20 | 8,11-dihydroxyoctadec-9Z-enoic acid | 0.30 | 0.64 |

| 21 | 8,12-dihydroxyoctadec-9Z-enoic acid | 4.78 | 0.43 |

| 22 | 10,12-dihydroxyoctadecanoic acid | ND | ND |

| 23 | 10,13-dihydroxyoctadecanoic acid | ND | ND |

| 24 | 11,12,13-trihydroxyoctadec-9Z-enoic acid | ND | ND |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Park, J.-B.; Cho, S.; Lee, S.-J. A Comprehensive Review on Medium- and Long-Chain Fatty Acid-Derived Metabolites: From Energy Sources to Metabolic Signals. Metabolites 2026, 16, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010045

Park J-B, Cho S, Lee S-J. A Comprehensive Review on Medium- and Long-Chain Fatty Acid-Derived Metabolites: From Energy Sources to Metabolic Signals. Metabolites. 2026; 16(1):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010045

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Jin-Byung, Sungyun Cho, and Sung-Joon Lee. 2026. "A Comprehensive Review on Medium- and Long-Chain Fatty Acid-Derived Metabolites: From Energy Sources to Metabolic Signals" Metabolites 16, no. 1: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010045

APA StylePark, J.-B., Cho, S., & Lee, S.-J. (2026). A Comprehensive Review on Medium- and Long-Chain Fatty Acid-Derived Metabolites: From Energy Sources to Metabolic Signals. Metabolites, 16(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010045