Metabolic Outcomes in Bariatric/Metabolic Surgery Individuals: Impact of Metabolic Health Definition, Type of Surgery, and Follow-Up Duration—An Observational, Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Population

2.2. Metabolic Health Phenotype Characterization

2.3. Statistical Analysis

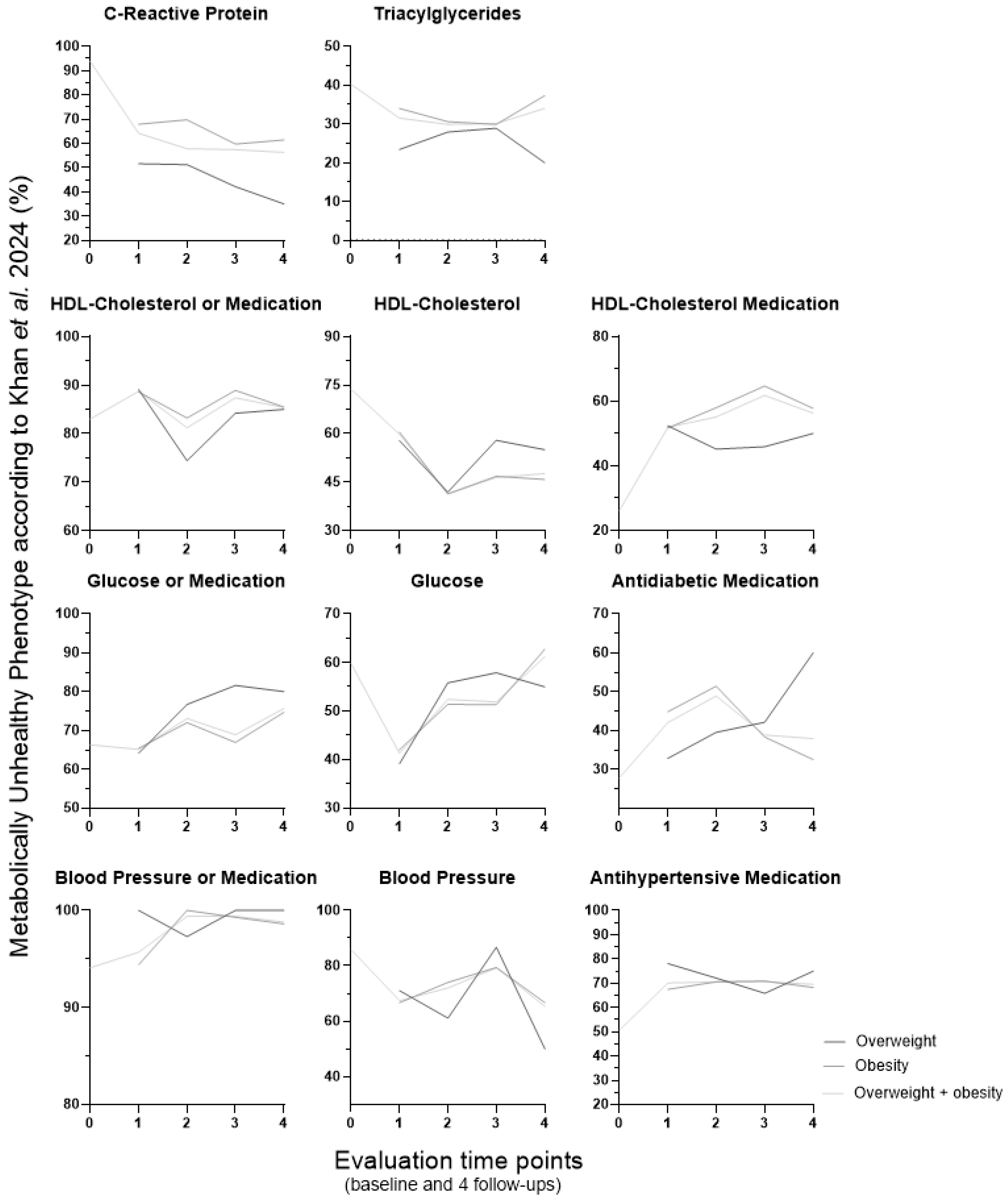

3. Results

3.1. Age of Start of Excess Weight, Body Mass Index and Relative Body Weight Loss

3.2. Metabolically Healthy and Unhealthy Phenotypes

3.3. Distribution of the Type of Surgery According to the Metabolic Health Phenotypes

3.4. Type of Surgery vs. Relative Body Weight Loss and Metabolic Parameters (from the Six Metabolic Health Definitions)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. At Least One in Eight People Now Obese. 2024. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2024/02/1147107 (accessed on 3 February 2024).

- Schulze, M.B.; Stefan, N. Metabolically healthy obesity: From epidemiology and mechanisms to clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2024, 20, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmaleh-Sachs, A.; Schwartz, J.L.; Bramante, C.T.; Nicklas, J.M.; Gudzune, K.A.; Jay, M. Obesity Management in Adults: A Review. JAMA 2023, 330, 2000–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic: Report of a WHO Consultation; WHO Technical Report Series 894; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999.

- Genua, I.; Tuneu, L.; Ramos, A.; Stantonyonge, N.; Caimari, F.; Balagué, C.; Fernández-Ananin, S.; Sánchez-Quesada, J.L.; Pérez, A.; Miñambres, I. Effectiveness of Bariatric Surgery in Patients with the Metabolically Healthy Obese Phenotype. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanriover, C.; Copur, S.; Gaipov, A.; Ozlusen, B.; Akcan, R.E.; Kuwabara, M.; Hornum, M.; Van Raalte, D.H.; Kanbay, M. Metabolically healthy obesity: Misleading phrase or healthy phenotype? Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 111, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneses, E.; Zagales, I.; Fanfan, D.; Zagales, R.; McKenney, M.; Elkbuli, A. Surgical, metabolic, and prognostic outcomes for Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus sleeve gastrectomy: A systematic review. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2021, 17, 2097–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedaghat, Z.; Khodakarim, S.; Nejadghaderi, S.A.; Sabour, S. Association between metabolic syndrome and myocardial infarction among patients with excess body weight: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckel, N.; Meidtner, K.; Kalle-Uhlmann, T.; Stefan, N.; Schulze, M.B. Metabolically healthy obesity and cardiovascular events: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2016, 23, 956–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preda, A.; Carbone, F.; Tirandi, A.; Montecucco, F.; Liberale, L. Obesity phenotypes and cardiovascular risk: From pathophysiology to clinical management. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2023, 24, 901–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Fan, S.; Liu, J.; He, X.; Zhu, T.; Yan, L.; Ren, M. Association Between Overweight/Obesity Metabolic Phenotypes Defined by Two Criteria of Metabolic Abnormality and Cardiovascular Diseases: A Cross-Sectional Analysis in a Chinese Population. Clin. Cardiol. 2024, 47, e70020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, J.; Wu, H.X.; Nawaz, M.A.; Jiang, H.; Xu, S.; Huang, B.; Li, L.; Cai, J.; Zhou, H. Risk of incident chronic kidney disease in metabolically healthy obesity and metabolically unhealthy normal weight: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2024, 25, e13656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, A.; Türk, Y.; Braunstahl, G.J. Obesity-related asthma: New insights leading to a different approach. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2024, 30, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, L.; Ye, L.; Jin, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Gu, W.; et al. Association of Metabolic Syndrome with Prevalence of Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Remission After Sleeve Gastrectomy. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 650260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, H.; Tian, F.; Chen, Y.; Ma, X. Association between Metabolically Healthy Status and Risk of Gastrointestinal Cancer. Cancer Res. Treat. 2024, 56, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedayati, M.; Valizadeh, M.; Abiri, B. Metabolic obesity phenotypes and thyroid cancer risk: A systematic exploration of the evidence. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2024, 10, e70019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamat-Saleh, Y.; Aune, D.; Freisling, H.; Hardikar, S.; Jaafar, R.; Rinaldi, S.; Gunter, M.J.; Dossus, L. Association of metabolic obesity phenotypes with risk of overall and site-specific cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 131, 1480–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R.; Appelbaum, L.; Schweiger, C.; Matot, I.; Constantini, N.; Idan, A.; Shussman, N.; Sosna, J.; Keidar, A. Short-term dynamics and metabolic impact of abdominal fat depots after bariatric surgery. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 1910–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goday, A.; Benaiges, D.; Parri, A.; Ramón, J.M.; Flores-Le Roux, J.A.; Pedro Botet, J. Can bariatric surgery improve cardiovascular risk factors in the metabolically healthy but morbidly obese patient? Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2014, 10, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelascini, E.; Disse, E.; Pasquer, A.; Poncet, G.; Gouillat, C.; Robert, M. Should we wait for metabolic complications before operating on obese patients? Gastric bypass outcomes in metabolically healthy obese individuals. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2016, 12, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzin, M.; Aryannezhad, S.; Khalaj, A.; Mahdavi, M.; Valizadeh, M.; Ghareh, S.; Azizi, F.; Hosseinpanah, F. Effects of bariatric surgery in different obesity phenotypes: Tehran Obesity Treatment Study (TOTS). Obes. Surg. 2020, 30, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.J.; Song, N.; Chung, E.S.; Heo, E.; Lee, H.; Kim, H.; Jeon, J.S.; Noh, H.; Kim, S.H.; Kwon, S.H. Changes in abdominal fat depots after bariatric surgery are associated with improved metabolic profile. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2023, 33, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engin, A. The Definition and Prevalence of Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome: Correlative Clinical Evaluation Based on Phenotypes. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2024, 1460, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Storms, S.; Oberhoff, G.H.; Schooren, L.; Kroh, A.; Koch, A.; Rheinwalt, K.-P.; Vondran, F.W.; Neumann, U.P.; Alizai, P.H.; Schmitz, S.M.-T. Preoperative nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and resolution of metabolic comorbidities after bariatric surgery. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2024, 20, 1288–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, A.; Perea, V.; Corcelles, R.; Moizé, V.; Lacy, A.; Vidal, J. Metabolic effects of bariatric surgery in insulin-sensitive morbidly obese subjects. Obes. Surg. 2013, 23, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goday, A.; Julià, H.; de Vargas-Machuca, A.; Pedro-Botet, J.; Benavente, S.; Ramon, J.M.; Pera, M.; Casajoana, A.; Villatoro, M.; Fontané, L.; et al. Bariatric surgery improves metabolic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease markers in metabolically healthy patients with morbid obesity at 5 years. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2021, 17, 2047–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luna, M.; Pereira, S.; Saboya, C.; Ramalho, A. Relationship between Body Adiposity Indices and Reversal of Metabolically Unhealthy Obesity 6 Months after Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. Metabolites 2024, 14, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesti, G.; Folli, F.; Perego, L.; Hribal, M.L.; Pontiroli, A.E. Effects of weight loss in metabolically healthy obese subjects after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding and hypocaloric diet. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- By-Band-Sleeve Collaborative Group. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, adjustable gastric banding, or sleeve gastrectomy for severe obesity (By-Band-Sleeve): A multicentre, open label, three-group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 410–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, I.; Martins, M.J.; Monteiro, R. Metabolically Healthy Obesity-Heterogeneity in Definitions and Unconventional Factors. Metabolites 2020, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Wei, P.; Suzauddula, M.; Nime, I.; Feroz, F.; Acharjee, M.; Pan, F. The interplay of factors in metabolic syndrome: Understanding its roots and complexity. Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ion, R.M.; Sibianu, M.; Hutanu, A.; Beresescu, F.G.; Sala, D.T.; Flavius, M.; Rosca, A.; Constantin, C.; Scurtu, A.; Moriczi, R.; et al. A Comprehensive Summary of the Current Understanding of the Relationship between Severe Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, and Inflammatory Status. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 2002, 106, 3143–3421.

- Grundy, S.M.; Cleeman, J.I.; Daniels, S.R.; Donato, K.A.; Eckel, R.H.; Franklin, B.A.; Gordon, D.J.; Krauss, R.M.; Savage, P.J.; Smith, S.C., Jr.; et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation 2005, 112, 2735–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 2001, 285, 2486–2497.

- Fahed, G.; Aoun, L.; Bou Zerdan, M.; Allam, S.; Bou Zerdan, M.; Bouferraa, Y.; Assi, H.I. Metabolic Syndrome: Updates on Pathophysiology and Management in 2021. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karelis, A.D.; Brochu, M.; Rabasa-Lhoret, R.; Garrel, D.; Poehlman, E.T. Clinical markers for the identification of metabolically healthy but obese individuals. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2004, 6, 456–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karelis, A.D.; Brochu, M.; Rabasa-Lhoret, R. Can we identify metabolically healthy but obese individuals (MHO)? Diabetes Metab. 2004, 30, 569–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meigs, J.B.; Wilson, P.W.; Fox, C.S.; Vasan, R.S.; Nathan, D.M.; Sullivan, L.M.; D’Agostino, R.B. Body mass index, metabolic syndrome, and risk of type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 2906–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, U.I.; Wang, D.; Thurston, R.C.; Sowers, M.; Sutton-Tyrrell, K.; Matthews, K.A.; Barinas-Mitchell, E.; Wildman, R.P. Burden of subclinical cardiovascular disease in “metabolically benign” and “at-risk” overweight and obese women: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Atherosclerosis 2011, 217, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Diabetes Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2023, 402, 203–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Hypertension. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 2. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48, S27–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, D.R.; Hosker, J.P.; Rudenski, A.S.; Naylor, B.A.; Treacher, D.F.; Turner, R.C. Homeostasis model assessment: Insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 1985, 28, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plümacher, A.; Dias, C.C.; Peleteiro, B.; Freitas, P.; Fortuna, I.; Lima, E.; Martins, E.; Martins, M.J. Defining metabolic health in obesity—Comparison of obesity phenotype definitions along with calcium and magnesium levels in obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery. In Proceedings of the Met–Con 24: 2nd Conference of the Doctoral Programme in Metabolism—Clinical and Experimental, Porto, Portugal, 25 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Plümacher, A.; Dias, C.C.; Peleteiro, B.; Freitas, P.; Fortuna, I.; Lima, E.; Martins, E.; Martins, M.J. Metabolic health before and after bariatric surgery: The impact of metabolic health definition (abstract 22621). In Proceedings of the IJUP’25, Porto, Portugal, 7–9 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Plümacher, A.; Martins, M.J. Obesity phenotypes in individuals undergoing bariatric surgery. In Proceedings of the Heart Team 2025: Joint Meeting of the Study Groups on Heart Failure (GEIC), Pulmonary Hypertension (GEHP), and Congenital Heart Diseases (GECC), Porto, Portugal, 9–10 January 2025. [Google Scholar]

- van Vliet-Ostaptchouk, J.V.; Nuotio, M.L.; Slagter, S.N.; Doiron, D.; Fischer, K.; Foco, L.; Gaye, A.; Gögele, M.; Heier, M.; Hiekkalinna, T.; et al. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolically healthy obesity in Europe: A collaborative analysis of ten large cohort studies. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2014, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Larrad, M.T.; Corbatón Anchuelo, A.; Del Prado, N.; Ibarra Rueda, J.M.; Gabriel, R.; Serrano-Ríos, M. Profile of individuals who are metabolically healthy obese using different definition criteria. A population-based analysis in the Spanish population. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haskins, I.N.; Chang, J.; Nor Hanipah, Z.; Singh, T.; Mehta, N.; McCullough, A.J.; Brethauer, S.A.; Schauer, P.R.; Aminian, A. Patients with clinically metabolically healthy obesity are not necessarily healthy subclinically: Further support for bariatric surgery in patients without metabolic disease? Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2018, 14, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, Y.; Jin, L.; Zeng, N.; Wang, L.; Zhao, K.; Lv, H.; Zhang, M.; Xu, W.; Zhang, P.; et al. Metabolic Features of Individuals with Obesity Referred for Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery: A Cohort Study. Obes. Surg. 2019, 29, 3966–3977, Correction in Obes. Surg. 2020, 30, 3258–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Tian, C.; Xu, G.; Du, D.; Zhang, N.; Wang, J.; Sang, Q.; Wuyun, Q.; Chen, W.; Lian, D.; et al. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Metabolic Characteristics of Metabolically Healthy Obesity in Patients Seeking Bariatric Surgery: A Cohort Study. Am. Surg. 2024, 90, 1456–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.J.; Clark, J.M.; Asamoah, V.; Schweitzer, M.; Magnuson, T.; Lazo, M. Prevalence and characteristics of individuals without diabetes and hypertension who underwent bariatric surgery: Lessons learned about metabolically healthy obese. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2015, 11, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worm, D.; Madsbad, S.; Hansen, D.L. Metabolic Health in Severely Obese Subjects: A Descriptive Study. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2019, 17, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laferrère, B. Bariatric surgery and obesity: Influence on the incretins. Int. J. Obes. Suppl. 2016, 6, S32–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, G.K.; Randeva, M.S.; Miras, A.D. Potential Hormone Mechanisms of Bariatric Surgery. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2017, 6, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Dera, A.; Morais, J.A.; Tsoukas, M.A.; Khor, N.; Sazonova, T.; Almeida, L.G.; Cooke, A.B.; Daskalopoulou, S.S.; Tam, B.T.; et al. Age of obesity onset affects subcutaneous adipose tissue cellularity differently in the abdominal and femoral region. Obesity 2024, 32, 1508–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, L.; Gauthier, M.F.; Lafortune, A.; Tchernof, A.; Santosa, S. Adipocyte size, adipose tissue fibrosis, macrophage infiltration and disease risk are different in younger and older individuals with childhood versus adulthood onset obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2022, 46, 1859–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faria, G.; Pestana, D.; Aral, M.; Preto, J.; Norberto, S.; Calhau, C.; João, T.G.; Taveira-Gomes, A. Metabolic score: Insights on the development and prediction of remission of metabolic syndrome after gastric bypass. Ann. Surg. 2014, 260, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildman, R.P.; Muntner, P.; Reynolds, K.; McGinn, A.P.; Rajpathak, S.; Wylie-Rosett, J.; Sowers, M.R. The obese without cardiometabolic risk factor clustering and the normal weight with cardiometabolic risk factor clustering: Prevalence and correlates of 2 phenotypes among the US population (NHANES 1999–2004). Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 1617–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, K.G.; Eckel, R.H.; Grundy, S.M.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Cleeman, J.I.; Donato, K.A.; Fruchart, J.-C.; James, W.P.T.; Loria, C.M.; Smith, S.C., Jr.; et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: A joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 2009, 120, 1640–1645. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| NCEP ATP III Modified from 2001, 2002, and 2005 [33,34,35] | Karelis et al. 2004 [37,38] | Meigs et al. 2006 [39] | Khan et al. 2011 [40] | Pluemacher et al. 2024 | Schulze et al. 2024 [2] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose and glucose-related parameters | Glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL. | Glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL or use of antidiabetic medication. | Glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL. | No prevalent type 2 diabetes mellitus a. | ||

| Insulin resistance | HOMA-IR ≥ 1.95. | HOMA-IR < 75th percentile (among the individuals without diabetes < 6.4). | HOMA-IR ≥ 75th percentile (among the individuals without diabetes ≥ 6.4). | |||

| Blood pressure | SBP/DBP ≥ 130/85 mmHg. | SBP/DBP ≥ 130/85 mmHg or use of antihypertensive medication. | SBP ≥ 130 mmHg. | SBP < 130 mmHg. No use of blood pressure-lowering medication. | ||

| Lipid profile | HDL–cholesterol < 40 mg/dL for men or 50 mg/dL for women. Triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL. | Triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL. Total cholesterol ≥ 200 mg/dL. LDL–cholesterol ≥ 100 mg/mL. HDL–cholesterol ≤ 50 mg/mL. | HDL–cholesterol ≤ 50 mg/dL or use of lipid-lowering medication. Triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL. | |||

| Inflammatory markers | CRP ≥ 3.0 mg/dL. | CRP ≥ 3.0 mg/dL. | ||||

| Baseline | ||||||

| Metabolically healthy overweight and obesity | ≤1 Metabolic abnormality AND WSC > 102 cm for men or 88 cm for women. | ≤1 Metabolic abnormality AND BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 OR WSC > 102 cm for men or 88 cm for women. | This criterion AND BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 OR WSC > 102 cm for men or 88 cm for women. | ≤2 Metabolic abnormalities AND BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2. | ≤1 Metabolic abnormalities AND BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2. | All these features AND waist-to-hip ratio < 0.95 for women and < 1.03 for men. |

| Follow-up | ||||||

| Metabolically healthy normal weight: BMI < 25 kg/m2 AND WSC ≤ 102 cm for men or 88 cm for women | ≤2 Metabolic abnormalities. | ≤1 Metabolic abnormality. | This criterion (HOMA-IR < 2 for 1st–3rd follow-ups and <2.2 for the 4th follow-up). | ≤2 Metabolic abnormalities. | ≤1 Metabolic abnormalities (HOMA-IR ≥ 2 for 1st–3rd follow-ups and ≥2.2 for the 4th follow-up). | All these features. |

| ** Metabolically healthy overweight: BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2 AND WSC ≤ 102 cm for men or 88 cm for women. ** Metabolically healthy obesity: BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 or WSC > 102 cm for men or 88 cm for women | ≤1 Metabolic abnormality. | ≤1 Metabolic abnormality. | This criterion (HOMA-IR < 2 for 1st–3rd follow-ups and <2.2 for the 4th follow-up). | ≤2 Metabolic abnormalities. | ≤1 Metabolic abnormalities (HOMA-IR ≥ 2 for 1st–3rd follow-ups and <2.2 for the 4th follow-up). | All these features. |

| Metabolic Health Phenotype Definition | Baseline Metabolic Health Phenotype | Start of Overweight or Obesity n (%) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood (<10 y) | Adolescence (10–20 y) | Adult Age (>20 y) | |||

| NCEP ATP III, modified from 2001, 2002, and 2005 [33,34,35] | MH | 249 (38.9) | 114 (41.2) | 285 (34.6) | 0.049 |

| MUH | 376 (60.2) | 163 (58.8) | 539 (65.4) | ||

| OR | Ref | 1.006 [0.752; 1.347] | 1.022 [0.814; 1.284] | ||

| Karelis et al. 2004 [37,38] | MH | 91 (13.9) | 35 (11.2) | 76 (8.7) | 0.006 |

| MUH | 564 (86.1) | 277 (88.8) | 797 (91.3) | ||

| OR | Ref | 1.283 [0.846; 1.946] | 1.668 [1.193; 2.333] | ||

| Meigs et al. 2006 [39] | MH | 498 (72.1) | 241 (73.0) | 653 (69.9) | 0.461 |

| MUH | 193 (27.9) | 89 (27.0) | 281 (30.1) | ||

| OR | Ref | 0.958 [0.714; 1.287] | 1.088 [0.869; 1.363] | ||

| Khan et al. 2011 [40] | MH | 232 (34.9) | 120 (38.3) | 291 (30.6) | 0.024 |

| MUH | 432 (65.1) | 193 (61.7) | 660 (69.4) | ||

| OR | Ref | 0.928 [0.698; 1.234] | 0.934 [0.746; 1.169] | ||

| Pluemacher et al. 2024 | MH | 91 (20.5) | 41 (20.7) | 113 (19.3) | 0.846 |

| MUH | 353 (79.5) | 157 (79.3) | 474 (80.7) | ||

| OR | Ref | 1.030 [0.679; 1.563] | 0.935 [0.676; 1.292] | ||

| Schulze et al. 2024 [2] | MH | 122 (18.9) | 66 (22.1) | 117 (13.1) | <0.001 |

| MUH | 522 (81.1) | 233 (77.9) | 775 (86.9) | ||

| OR | Ref | 0.878 [0.621; 1.241] | 1.001 [0.740; 1.353] | ||

| Metabolic Health Phenotype Definition | Baseline Phenotype Group | Relative Body Weight Loss (%) (Mean ± SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Follow-Up | 2nd Follow-Up | 3rd Follow-Up | 4th Follow-Up | ||

| NCEP ATP III, modified from 2001, 2002, and 2005 [33,34,35] | MH | 31.30 ± 10.48 | 31.09 ± 11.49 | 28.98 ± 11.60 # | 26.89 ± 11.74 ###; &&& |

| MUH | 31.71 ± 9.83 | 31.47 ± 10.41 | 29.52 ± 10.84 ### | 27.45 ± 10.63 ###; &&& | |

| Karelis et al. 2004 [37,38] | MH | 33.85 ± 9.55 | 33.26 ± 10.39 | 31.67 ± 10.40 a | 29.27 ± 12.61 #; c |

| MUH | 32.66 ± 9.79 | 32.53 ± 10.48 | 29.83 ± 11.39 ### | 28.17 ± 10.91 ###; &&& | |

| Meigs et al. 2006 [39] | MH | 32.84 ± 9.83 | 32.83 ± 10.55 | 30.52 ± 11.25 ### | 28.97 ± 11.31 ###; &&& |

| MUH | 32.56 ± 9.52 | 32.29 ± 9.91 | 29.49 ± 10.75 ### | 27.38 ± 10.03 ###; && | |

| Khan et al. 2011 [40] | MH | 34.66 ± 8.83 | 34.91 ± 8.98 | 32.54 ± 9.96 ## | 30.32 ± 10.93 ###; &&& |

| MUH | 33.23 ± 8.66 *** | 33.17 ± 9.35 *** | 31.38 ± 9.70 ###, b | 29.17 ± 9.83 ###; &&& | |

| Pluemacher et al. 2024 | MH | 33.44 ± 9.30 | 33.53 ± 8.86 | 31.11 ± 9.82 | 28.55 ± 12.40 & |

| MUH | 33.86 ± 8.46 | 33.75 ± 9.13 | 31.35 ± 9.81 ### | 29.02 ± 9.80 ###; &&& | |

| Schulze et al. 2024 [2] | MH | 32.33 ± 10.07 | 32.36 ± 10.48 | 29.98 ± 11.16 # | 28.29 ± 10.83 ##; && |

| MUH | 31.76 ± 9.78 | 31.61 ± 10.74 | 29.81 ± 10.82 ### | 27.67 ± 10.99 ###; &&& | |

| Evaluation Time Points | Weight Groups | Number of Metabolic Features in Metabolically Unhealthy Phenotype (Mean ± SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCEP ATP III Modified from 2001, 2002, and 2005 [33,34,35] | Karelis et al. 2004 [37,38] | Khan et al. 2011 [40] | Pluemacher et al. 2024 | Schulze et al. 2024 [2] | ||

| Baseline | OW + OB | 2.56 ± 0.686 | 3.08 ± 0.921 | 3.69 ± 0.720 | 2.71 ± 0.761 | 1.79 ± 0.842 |

| 1st Follow-up | OW + OB | 2.20 ± 0.477 * | 2.54 ± 0.755 * | 3.37 ± 0.585 * | 2.44 ± 0.595 * | 1.31 ± 0.479 * |

| OW | 2.04 ± 0.196 | 2.31 ± 0.550 | 3.17 ± 0.380 | 2.31 ± 0.503 | 1.26 ± 0.441 | |

| OB | 2.26 ± 0.535 | 2.66 ± 0.816 | 3.42 ± 0.623 | 2.47 ± 0.613 | 1.33 ± 0.494 | |

| NW | 3.00 ± 0.000 | 2.13 ± 0.409 | 3.29 ± 0.469 | 2.24 ± 0.436 | 1.07 ± 0.361 | |

| 2nd Follow-up | OW + OB | 2.26 ± 0.549 * | 2.48 ± 0.691 * | 3.32 ± 0.531 * | 2.45 ± 0.600 * | 1.33 ± 0.510 * |

| OB | 2.29 ± 0.588 | 2.57 ± 0.743 | 3.37 ± 0.564 | 2.45 ± 0.597 | 1.38 ± 0.532 | |

| OW | 2.12 ± 0.326 | 2.30 ± 0.539 | 3.14 ± 0.351 | 2.44 ± 0.619 | 1.19 ± 0.420 | |

| NW | 3.00± 0.000 | 2.20 ± 0.467 | 3.13 ± 0.354 | 2.14 ± 0.363 | 1.07 ± 0.264 | |

| 3rd Follow-up | OW + OB | 2.25 ± 0.515 * | 2.51 ± 0.751 * | 3.34 ± 0.579 * | 2.49 ± 0.644 * | 1.37 ± 0.512 * |

| OB | 2.27 ± 0.517 | 2.59 ± 0.790 | 3.36 ± 0.592 | 2.55 ± 0.661 | 1.41 ± 0.531 | |

| OW | 2.19 ± 0.512 | 2.36 ± 0.641 | 3.21 ± 0.528 | 2.28 ± 0.528 | 1.27 ± 0.446 | |

| NW | 3.00 ± 0.000 | 2.20 ± 0.401 | 3.33 ± 0.516 | 2.38 ± 0.518 | 1.17 ± 0.388 | |

| 4th Follow-up | OW + OB | 2.27 ± 0.520 * | 2.54 ± 0.684 * | 3.33 ± 0.531 * | 2.51 ± 0.649 * | 1.35 ± 0.547 * |

| OW | 2.14 ± 0.378 | 2.33 ± 0.492 | 3.00 ± 0.000 | 2.10 ± 0.316 | 1.09 ± 0.292 | |

| OB | 2.29 ± 0.536 | 2.64 ± 0.736 | 3.41 ± 0.564 | 2.57 ± 0.664 | 1.41 ± 0.577 | |

| NW | 3.00 ± 0.000 | 2.32 ± 0.548 | 3.00 ± 0.000 | 2.20 ± 0.447 | 1.33 ± 0.500 | |

| Compared Against | RBWL Mean Difference (%) | 95% Confidence-Interval (%) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Follow-up | RYGB | Sleeve gastrectomy | 2.53 | [1.70; 3.37] | <0.001 |

| Gastric band | 17.89 | [16.47; 19.31] | <0.001 | ||

| Sleeve gastrectomy | Gastric band | 15.35 | [13.86; 16.85] | <0.001 | |

| 2nd Follow-up | RYGB | Sleeve gastrectomy | 4.37 | [3.39; 5.35] | <0.001 |

| Gastric band | 18.76 | [16.51; 20.53] | <0.001 | ||

| Sleeve gastrectomy | Gastric band | 14.39 | [12.70; 16.08] | <0.001 | |

| 3rd Follow-up | RYGB | Sleeve gastrectomy | 4.02 | [2.83; 5.22] | <0.001 |

| Gastric band | 16.87 | [14.83; 18.90] | <0.001 | ||

| Sleeve gastrectomy | Gastric band | 12.84 | [10.89; 14.79] | <0.001 | |

| 4th Follow-up | RYGB | Sleeve gastrectomy | 4.78 | [3.31; 6.25] | <0.001 |

| Gastric band | 15.59 | [13.37; 17.81] | <0.001 | ||

| Sleeve gastrectomy | Gastric band | 10.81 | [8.44; 13.17] | <0.001 |

| Gastric Band, n (%) | RYGB, n (%) | Sleeve Gastrectomy, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes at Baseline | ||||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Diabetes at 1st follow-up | ||||||

| No | 195 (99%) | 16 (67%) | 1325 (100%) | 137 (95%) | 687 (99%) | 51 (88%) |

| Yes | 1 (1%) | 8 (33%) | 2 (0%) | 8 (5%) | 4 (1%) | 7 (12%) |

| Diabetes at 1st follow-up | ||||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Diabetes at 2nd follow-up | ||||||

| No | 138 (97%) | 3 (50%) | 1057 (100%) | 3 (43%) | 516 (99%) | 4 (40%) |

| Yes | 4 (3%) | 3 (50%) | 3 (0%) | 4 (57%) | 5 (1%) | 6 (60%) |

| Diabetes at 2nd follow-up | ||||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Diabetes at 3rd follow-up | ||||||

| No | 101 (96%) | 2 (50%) | 767 (99%) | 4 (67%) | 372 (99%) | 2 (33%) |

| Yes | 4 (4%) | 2 (50%) | 6 (1%) | 2 (33%) | 5 (1%) | 4 (67%) |

| Diabetes at 3rd follow-up | ||||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Diabetes at 4th follow-up | ||||||

| No | 73 (96%) | 2 (40%) | 548 (99%) | 3 (38%) | 288 (99%) | 2 (25%) |

| Yes | 3 (4%) | 3 (60%) | 4 (1%) | 5 (62%) | 3 (1%) | 6 (75%) |

| Gastric Band, n (%) | RYGB, n (%) | Sleeve Gastrectomy, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Blood Pressure at Baseline | ||||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| High blood pressure at 1st follow-up | ||||||

| No | 16 (52%) | 31 (44%) | 120 (77%) | 242 (61%) | 46 (75%) | 87 (55%) |

| Yes | 15 (48%) | 39 (56%) | 36 (23%) | 154 (39%) | 15 (25%) | 72 (45%) |

| High blood pressure at 1st follow-up | ||||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| High blood pressure at 2nd follow-up | ||||||

| No | 18 (75%) | 10 (29%) | 151 (80%) | 33 (36%) | 51 (81%) | 15 (31%) |

| Yes | 6 (25%) | 24 (71%) | 38 (20%) | 60 (64%) | 12 (19%) | 33 (69%) |

| High blood pressure at 2nd follow-up | ||||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| High blood pressure at 3rd follow-up | ||||||

| No | 15 (83%) | 6 (32%) | 69 (71%) | 22 (35%) | 27 (69%) | 7 (23%) |

| Yes | 3 (17%) | 13 (68%) | 28 (29%) | 40 (65%) | 12 (31%) | 24 (77%) |

| High blood pressure at 3rd follow-up | ||||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| High blood pressure at 4th follow-up | ||||||

| No | 9 (64%) | 4 (40%) | 51 (77%) | 21 (43%) | 8 (73%) | 9 (56%) |

| Yes | 5 (36%) | 6 (60%) | 15 (23%) | 28 (57%) | 3 (27%) | 7 (44%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pluemacher, A.; Dias, C.C.; Peleteiro, B.; Pinheiro, D.; Freitas, P.; Lima, E.; Leitão, A.; Martins, E.; Martins, M.J. Metabolic Outcomes in Bariatric/Metabolic Surgery Individuals: Impact of Metabolic Health Definition, Type of Surgery, and Follow-Up Duration—An Observational, Retrospective Study. Metabolites 2026, 16, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010047

Pluemacher A, Dias CC, Peleteiro B, Pinheiro D, Freitas P, Lima E, Leitão A, Martins E, Martins MJ. Metabolic Outcomes in Bariatric/Metabolic Surgery Individuals: Impact of Metabolic Health Definition, Type of Surgery, and Follow-Up Duration—An Observational, Retrospective Study. Metabolites. 2026; 16(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010047

Chicago/Turabian StylePluemacher, Anna, Cláudia Camila Dias, Bárbara Peleteiro, Denise Pinheiro, Paula Freitas, Eduardo Lima, Alexandra Leitão, Elisabete Martins, and Maria João Martins. 2026. "Metabolic Outcomes in Bariatric/Metabolic Surgery Individuals: Impact of Metabolic Health Definition, Type of Surgery, and Follow-Up Duration—An Observational, Retrospective Study" Metabolites 16, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010047

APA StylePluemacher, A., Dias, C. C., Peleteiro, B., Pinheiro, D., Freitas, P., Lima, E., Leitão, A., Martins, E., & Martins, M. J. (2026). Metabolic Outcomes in Bariatric/Metabolic Surgery Individuals: Impact of Metabolic Health Definition, Type of Surgery, and Follow-Up Duration—An Observational, Retrospective Study. Metabolites, 16(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010047