Personalized Physical Activity Programs for the Management of Knee Osteoarthritis in Individuals with Obesity: A Patient-Centered Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

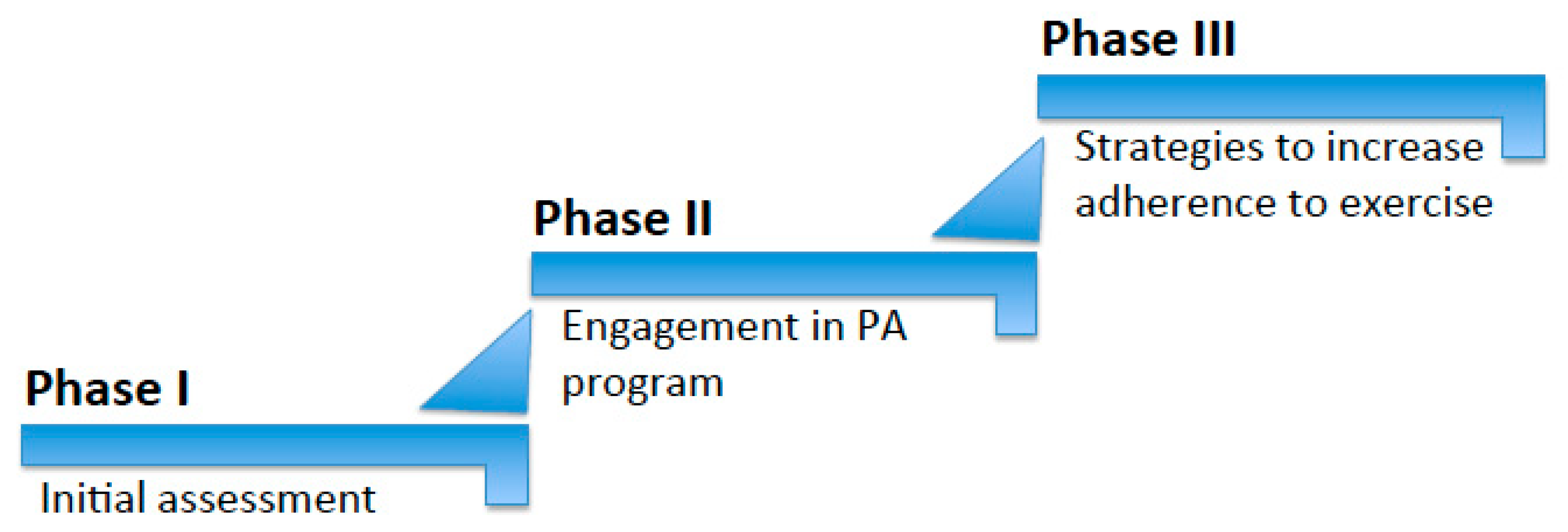

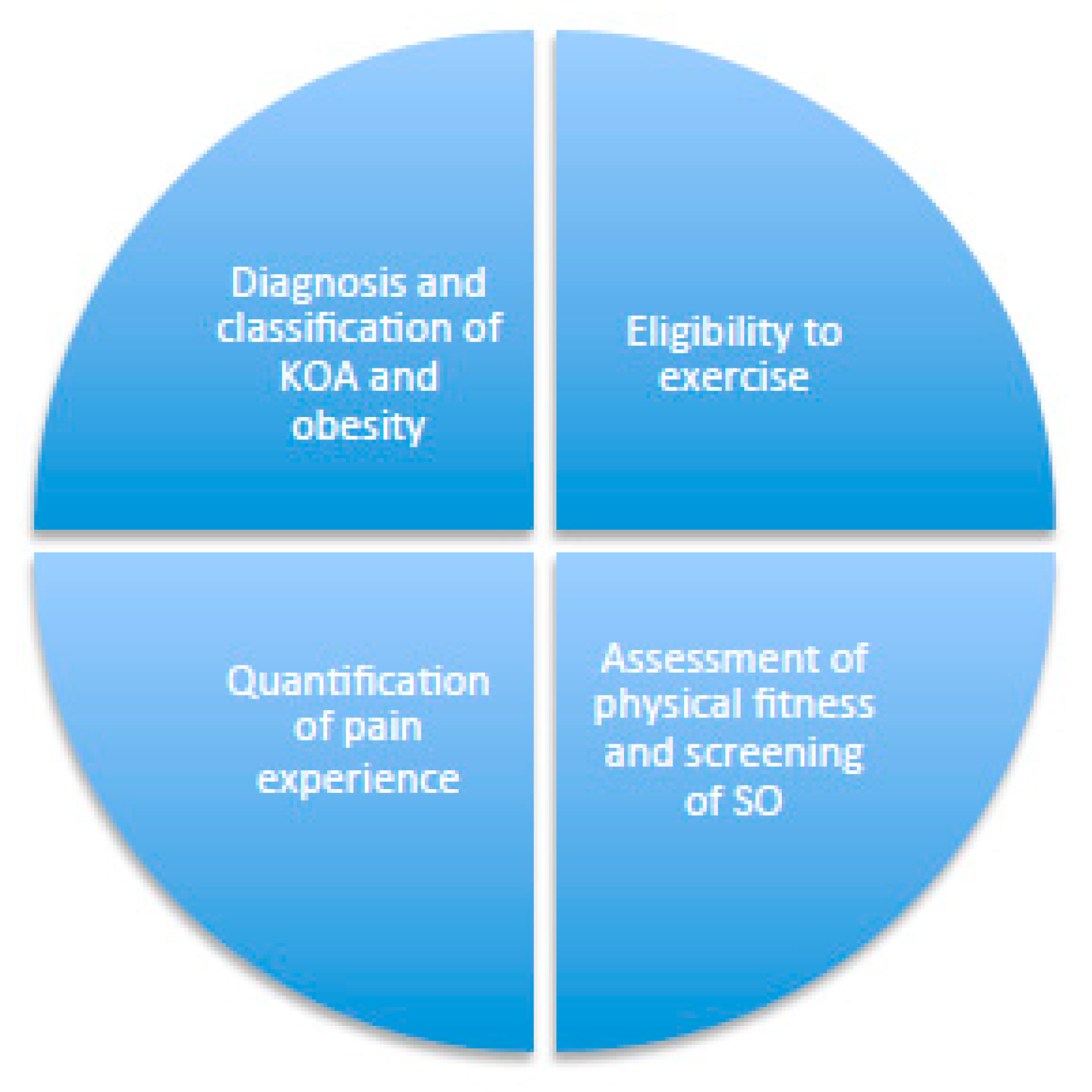

3.1. Phase I: Initial Assessment

- Diagnosis of KOA and Obesity—After considering the patient’s medical history and performing an accurate physical examination, X-ray and ultrasound, a diagnosis of KOA should be confirmed or rejected [16] via the Kellgren and Lawrence classification system, as detailed in Table 1 [17]. Screening for obesity and determining its clinical severity through anthropometric and body composition measures should then occur, as reported below and in Table 1.

- ○

- Body mass index (BMI) is the ratio of body weight in kg to height squared in meters (kg/m2). It is simple to obtain since it does not require sophisticated measurement tools, which means it is widely used in clinical settings to determine weight-related risk factors [18]. It can be determined according to the standard formula of body weight in kg divided by height in meters squared, measured with calibrated scales and a stadiometer, respectively. The patient is usually assessed while wearing lightweight clothing and no shoes. In Caucasians, a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 is normally indicative of obesity, categorized into three different classes: class I: BMI 30–34.9 kg/ m2; class II: BMI 35–39.9 kg/m2; class III: BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2, or specific cut-off points based on age, gender and ethnicity [19,20] (Table 1).

- ○

- Waist circumference (WC) is a measurement of abdominal adiposity in centimeters, obtained via a tape measure at the level of the iliac crest while the individual is breathing normally. In Caucasians, a WC > 88 cm in females or 102 cm in males (in Europids, 80 cm in females, 94 cm in males) usually indicates abdominal obesity [21]. There are also age, ethnicity and gender-specific cut-offs that have been suggested (Table 1).

- ○

- Body fat percentage (BF%) is defined as the amount of fat in the body, expressed frequently in kg. To determine the BF%, different techniques are used, e.g., bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), hydrostatic underwater weighing, air displacement plethysmography (BOD-POD), computed tomography (CT) scanning or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [22]. Age, ethnicity and gender-specific cut-offs have been suggested [23] (Table 1).

- Eligibility for Exercise—It is recommended that patients with KOA and obesity undergo medical evaluation for exercise eligibility in order to exclude the presence of other chronic diseases or a family history of cardiovascular diseases that may contraindicate exercising. Patients who reply with ‘no’ to any item reported in Table 2 can start a moderate-intensity PA program. Patients who report an affirmative response to at least one item should undergo a specialist second-level evaluation based on the chronic diseases reported in a checklist to determine their eligibility to exercise [24] (Figure 2 and Table 2).

- Assessment of Physical Fitness and Performance—Physical fitness and performance are the ability of an individual to execute daily activities and are based on several components: body composition, cardiorespiratory endurance, flexibility and muscular strength and endurance [25]. It is vital to assess physical fitness and performance in order to understand the capacity and ability of the patient to exercise. Such an assessment also supports the development of a personalized PA program of a suitable nature and duration, based on a set of physical function performance tests for use in people diagnosed with KOA, as recommended by an international, multidisciplinary expert advisory group and endorsed by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI). These include a 30 s chair stand test (30 s-CST), a 40 m fast-paced walk test (40 m FPWT), a stair-climb test, a timed up and go test (TUG) and a six-minute walk test (6 MWT), with normative values as indicated for people diagnosed with KOA [26].

- Screening for Sarcopenic Obesity (SO)—SO is defined as an increased body fat deposition and decreased muscle mass and strength [27]. Recent reports have demonstrated that SO seems to negatively impact therapeutic and surgical outcomes in patients with KOA [28]; hence, it is vital to screen for SO in this population [29]. However, to the best of our knowledge, very few physical performance tests and tools are available to screen for SO in patients with KOA. Recent work has shown that hand grip strength adjusted by BMI, with cut-offs below 0.65 in females and 1.1 in males, can be indicative of a higher risk of SO in people with KOA [30]. A more accurate assessment should be conducted in order to confirm the diagnosis of SO. Appendicular lean mass (ALM), adjusted by body size (i.e., body weight (kg) or BMI (kg/m2) seem to be clinically reasonable in this population. Specifically, ALM/BMI cut-off points of <0.512 in females and <0.789 in males appear to be suitable for the identification of SO in a clinical population with KOA [30].

- Quantification of the Pain Experience—Pain is a highly unpleasant physical sensation caused by illness or injury [31]. It is affected by physiological, psychological and demographic factors, which cause great variation in individual perception. The experience of pain seems to affect the participation of individuals with KOA in PA [32]; therefore, quantifying the pain experience in this population is an important first step before its management. Several self-report tools are available for this purpose, such as the short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ-SF) [33].

3.2. Phase II: Patient-Centered Approach: Engagement in a Personalized Physical Activity Program

- Patient-Centered Communication

- Patient-Centered Engagement in a Personalized Exercise Program

- ○

- Active Lifestyle (Expressed as Steps/Day)—The primary aim of developing an active lifestyle is to reduce the time spent in sedentary behaviors by working on the PAs that are part of everyday life (e.g., walking, standing, climbing stairs, cleaning the house, gardening, etc.). It is best expressed as the number of steps per day and is easily monitored via simple tools such as pedometers [38]. An early observational longitudinal study conducted in an elderly population with obesity revealed that walking is associated with a lower risk of functional limitations [39]. A cut-off of 6000 steps/day appeared to be protective, and each additional 1000 steps/day was associated with an approximately 20% reduction in the risk of functional limitation [39]. In another, recently published study undertaken with patients with KOA who were overweight/obese, participants who did not report regular knee pain and who regularly walked for exercise were less likely to later develop knee pain (26%) at a follow-up eight years later compared with those who did not (37%) [40] (Table 3). The importance of an active lifestyle (expressed in steps/day) stems from its impact on weight control. Early data derived from the U.S. National Weight Control Registry showed that people with successful long-term weight-loss maintenance share common behaviors, such as adhering to a low-fat diet, engaging in frequent self-monitoring of body weight and food intake, and having high levels of regular exercise, specifically 10,000 steps/day [41]. More recent work has shown that walking 11,000 steps or more prevents overweight individuals from developing obesity after four years of follow-up by nearly 64% [42]. An active lifestyle should be prioritized in this population (i.e., those with KOA who are affected by overweight/obesity) because of its dual impact.

- Formal Exercise

- ○

- Land-Based Exercise—The European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO) [43] and the OA Research Society International (OARSI) [44,45] proposed strong recommendations for land-based exercises for the non-surgical management of KOA. These recommendations were based on high-quality evidence derived from several systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that identified significant clinical benefits in the short term (two to six months), especially in relation to pain reduction and physical function improvement [46,47,48,49,50]. The nature (i.e., duration and type of exercise) of the programs in these guidelines varied widely from strength training to a range of motion exercises and aerobic activity [46,47,48,49,50]. More recent work has specifically recommended activities such as Pilates and aerobic and strengthening exercise programs, which have been shown to have beneficial effects, especially on pain and strength, when performed over eight to twelve weeks for a total of three to five sessions per week. Each session must last at least 1 h to be effective [51] (Table 3).

- ○

- Water-Based Exercise—The hydrostatic pressure and resistance of water, especially in warm temperatures (i.e., heated pools), create a beneficial environment for patients with KOA [52]. Specifically, in water, the knee is less overloaded by body weight, the muscles supporting the knee can be strengthened in a non-traumatic way and the blood flows better [52]. Therefore, water-based exercise is recommended for patients with severe KOA and obesity, or for those with a proprioceptive deficit [52]. An earlier systematic review of RCTs assessing the effectiveness of water-based exercise on KOA found that this approach results in improvements in self-reported pain and disability, but that the effect seems to be of a small magnitude and short duration [53]. Recently, another systematic review and meta-analysis with more specific recommendations was conducted [54] based on RCTs involving administered water-based exercise programs in pools in which the water was between waist and chest height and at a temperature of 28–34 °C, with a duration/session of 50 to 60 min for two to five sessions/week, and over an intervention program period of 12 weeks. These interventions were found to alleviate pain, improve the quality of life and reduce dysfunction [54] (Table 3). However, more research is still needed to clarify the exact type of such water-based exercise.

3.3. Phase III: Strategies to Increase Adherence to Exercise

- Education on the Benefits of PA for Health, and Motivating Patients to Exercise—In general, education is a key factor in OA management [55]. People with greater knowledge about the benefits of PA for health tend to be more active [56]. It is therefore useful to highlight the benefits of regular PA for both KOA and obesity and discuss with patients the available evidence regarding the impact of PA (Figure 3) in (i) decreasing pain, (ii) improving function and (iii) enhancing HRQoL [51]. PA has several positive effects on obesity [12] that are also worth highlighting to patients, such as (i) increased energy expenditure and enhanced adherence to caloric restriction [57]; (ii) preservation of muscle mass during weight loss [10]; (iii) maintaining long-term weight loss [58]; and (iv) enhancing body image and psychological outlook [59] (Figure 3). Moreover, the adoption of an engaging style is vital for motivating patients to exercise. Health professionals should, first of all, show empathy for the patient’s difficulties in exercising because of obesity and KOA, and always propose an achievable PA program for using a collaborative style [60] (Figure 4).

- Increase the Levels of Physical Fitness and Performance—To improve cardiovascular fitness [61], aerobic outdoor (i.e., walking, cycling, swimming, jogging, etc.) and/or indoor (i.e., exercise bike, climbing stairs, aerobic gymnastics, etc.) activities, when undertaken correctly at a certain intensity, duration and frequency, may have numerous benefits, such as enhancing cardiorespiratory fitness [62]. Calisthenic gymnastics [63], which consist of the use of body weight and gravity, can be used to increase muscular tone and strength via continuous repetitions of a certain exercise, which is usually called a ‘set’. The increase in the number of sets of a certain exercise may boost the resistance and strength of a specific group of muscles. Muscular flexibility and elasticity can be developed through stretching exercises that consist of a unique slow stretching movement to a position of mild muscular tension but not pain, holding for 20 s. This process should be repeated two to three times with an increased level of muscular tension (Figure 1 and Figure 4).

- Sarcopenic Obesity Management—The management of SO in patients with KOA and obesity is just as important as the improvement of physical fitness. There are several recent publications relating to this specific population, covering different dietary and nutritional strategies that can potentially ameliorate the severity of KOA and, simultaneously, improve SO indices [64]. Adherence to a low-calorie Mediterranean diet can determine significant weight loss and remains the cornerstone nutritional approach in this population [64]. Supplements such as vitamin D, essential and non-essential amino acids and whey protein also appear to be beneficial to both KOA and SO [64].

- Pain Management—Pain is a barrier to PA that is consistently reported by people with KOA. Its management remains an important target of interventions, especially in its acute phase and involves a range of strategies, including the following: (i) over-the-counter medications (i.e., paracetamol) [65]; (ii) oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAIDs) (i.e., cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors), corticosteroids, opioids (i.e., tramadol) and others (i.e., duloxetine, capsaicin) [65]; (iii) topical and intra-articular drugs (i.e., NSAIDs, corticosteroids, hyaluronic acid) [65]; (iv) acupuncture [66]; (v) physical therapy [67]; (vi) weight loss; and (vii) cognitive behavioral therapy [68].

- Sustainable Environment and Social Support for a More Active Lifestyle—Treatment should aim to modify the environment from a stigmatizing to a stimulating one [69] that supports changes towards instilling habits regarding exercise, free of architectonic barriers [70,71]. Patients are encouraged to reduce triggers for physical inactivity and increase positive cues for healthy PA [72]. Several studies suggest that social support is a key factor in behavioral changes and is considered to be an important aid for weight loss maintenance [73]. Specifically, more social support, especially from relatives, is associated with higher levels of leisure PA [74]. Therefore, it is important to involve patients’ families to create the optimum environment for change, since they can be crucial in encouraging patients to change and increase their level of PA [55]. It is vital that significant others are educated about obesity, KOA and physical exercise, and encouraged to be actively involved in exploring how to help patients develop and maintain an active lifestyle [55]. Although it is important to consider that needs vary from patient to patient, the general advice to give to family and friends includes creating a relaxed environment, reinforcing positive behaviors, adopting a positive attitude, exercising together and accepting patients’ difficulties, as ambivalence can lead to setbacks [55].

- Personalized Goal-Setting and Real-Time Monitoring—Patients are encouraged to set specific and quantifiable weekly PA goals that are challenging but realistically achievable [75]. Reaching goals leads to self-reinforcement and self-efficacy enhancement [76]. Patients should start with gentle exercising and gradually increase to a weekly goal, as per the PA recommendations in primary care [77]. For instance, walking (i.e., an active lifestyle) is the preferred PA for patients with KOA [39,40,78] since it is a form of unstructured PA that can be easily implemented in a daily routine, with a goal to increase daily steps by 500 a day to reach 10,000 daily steps. If patients are willing to initiate a formal form of land- or water-based PA, this is also advisable, and strategies such as encouraging patients to exercise with a family member or friend, enroll in a club or gym or seek help from a personal trainer are all good methods that can help them to increase their adherence to this type of PA. In both cases (daily steps or formal PA), the setting of unrealistic goals should be promptly discouraged when discussing this topic with the patient. Finally, in line with personalized goal setting for PA, the self-monitoring of PA, whether through structured or unstructured forms, is another strategy in which real-time monitoring raises patients’ awareness of their exercise habits and helps them to improve and increase their levels of PA [79]. To achieve this aim, PA can be recorded on a monitoring record in minutes (of programmed activity) and/or number of steps (of lifestyle activity) using a pedometer [79].

4. Discussion

4.1. Findings

4.2. Clinical Implications

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. New Directions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heidari, B. Knee osteoarthritis prevalence, risk factors, pathogenesis and features: Part I. Casp. J. Intern. Med. 2011, 2, 205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, A.; Li, H.; Wang, D.; Zhong, J.; Chen, Y.; Lu, H. Global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in population-based studies. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 29–30, 100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghoch, M.; Fakhoury, R. Challenges and new directions in obesity management: Lifestyle modification programs, pharmacotherapy, and bariatric surgery. J. Popul. Ther. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 26, e1–e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutari, C.; Mantzoros, C.S. A 2022 update on the epidemiology of obesity and a call to action: As its twin COVID-19 pandemic appears to be receding, the obesity and dysmetabolism pandemic continues to rage on. Metabolism 2022, 133, 155217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.; Kean, W.F. Obesity and knee osteoarthritis. Inflammopharmacology 2012, 20, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspersen, C.J.; Powell, K.E.; Christenson, G.M. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985, 100, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kruk, J. Physical activity in the prevention of the most frequent chronic diseases: An analysis of the recent evidence. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2007, 8, 325–338. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, D.G.; Costa, D.; Cruz, E.B.; Mendonça, N.; Henriques, A.R.; Branco, J.; Canhão, H.; Rodrigues, A.M. Association of physical activity with physical function and quality of life in people with hip and knee osteoarthritis: Longitudinal analysis of a population-based cohort. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2023, 25, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippe, J.M.; Hess, S. The role of physical activity in the prevention and management of obesity. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1998, 10, S31–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, E.; Yeat, N.C.; Mittendorfer, B. Preserving Healthy Muscle during Weight Loss. Adv. Nutr. 2017, 8, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, C.E. Role of Physical Activity for Weight Loss and Weight Maintenance. Diabetes Spectr. 2017, 30, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojednic, R.; D’Arpino, E.; Halliday, I.; Bantham, A. The Benefits of Physical Activity for People with Obesity, Independent of Weight Loss: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, P.V.; Alves, A.A.; Aily, J.B.; Selistre, L.A. Challenges To Implementing Physical Activity in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2023, 31, S408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhera, J. Narrative Reviews in Medical Education: Key Steps for Researchers. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2022, 14, 418–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narrative Review Checklist. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/__data/promis_misc/ANDJNarrativeReviewChecklistpdf (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Jang, S.; Lee, K.; Ju, J. Recent Updates of Diagnosis, Pathophysiology, and Treatment on Osteoarthritis of the Knee. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohn, M.D.; Sassoon, A.A.; Fernando, N. Classifications in Brief: Kellgren-Lawrence Classification of Osteoarthritis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2016, 474, 1886–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keys, A.; Menotti, A.; Aravanis, C.; Blackburn, H.; Djordevič, B.S.; Buzina, R.; Dontas, A.S.; Fidanza, F.; Karvonen, M.J.; Kimura, N.; et al. The seven countries study: 2289 deaths in 15 years. Prev. Med. 1984, 13, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itani, L.; Kreidieh, D.; El Masri, D.; Tannir, H.; Chehade, L.; El Ghoch, M. Revising BMI Cut-Off Points for Obesity in a Weight Management Setting in Lebanon. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Renzo, L.; Itani, L.; Gualtieri, P.; Pellegrini, M.; El Ghoch, M.; De Lorenzo, A. New BMI Cut-Off Points for Obesity in Middle-Aged and Older Adults in Clinical Nutrition Settings in Italy: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.Y.; Yang, C.Y.; Shih, S.R.; Hsieh, H.J.; Hung, C.S.; Chiu, F.C.; Lin, M.S.; Liu, P.H.; Hua, C.H.; Hsein, Y.C.; et al. Measurement of Waist Circumference: Midabdominal or Iliac Crest? Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 1660–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duren, D.L.; Sherwood, R.J.; Czerwinski, S.A.; Lee, M.; Choh, A.C.; Siervogel, R.M.; Chumlea, W.C. Body Composition Methods: Comparisons and Interpretation. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2008, 2, 1139–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, D.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Heo, M.; Jebb, S.A.; Murgatroyd, P.R.; Sakamoto, Y. Healthy percentage body fat ranges: An approach for developing guidelines based on body mass index. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilder, R.P.; Greene, J.A.; Winters, K.L.; Long, W.B.; Gubler, K.; Edlich, R.F. Physical fitness assessment: An update. J. Long. Term. Eff. Med. Implant. 2006, 16, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobson, F.; Hinman, R.S.; Roos, E.M.; Abbott, J.H.; Stratford, P.; Davis, A.M.; Buchbinder, R.; Snyder-Mackler, L.; Henrotin, Y.; Thumboo, J.; et al. OARSI recommended performance-based tests to assess physical function in people diagnosed with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2013, 21, 1042–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donini, L.M.; Busetto, L.; Bischoff, S.C.; Cederholm, T.; Ballesteros-Pomar, M.D.; Batsis, J.A.; Bauer, J.M.; Boirie, Y.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Dicker, D.; et al. Definition and Diagnostic Criteria for Sarcopenic Obesity: ESPEN and EASO Consensus Statement. Obes. Facts 2022, 15, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godziuk, K.; Prado, C.M.; Woodhouse, L.J.; Forhan, M. The impact of sarcopenic obesity on knee and hip osteoarthritis: A scoping review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2018, 19, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, M.; Itani, L.; Rossi, A.P.; Kreidieh, D.; El Masri, D.; Tannir, H.; El Ghoch, M. Approaching Sarcopenic Obesity in Young and Middle-Aged Female Adults in Weight Management Settings: A Narrative Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godziuk, K.; Woodhouse, L.J.; Prado, C.M.; Forhan, M. Clinical screening and identification of sarcopenic obesity in adults with advanced knee osteoarthritis. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2020, 40, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, S.N.; Carr, D.B.; Cohen, M.; Finnerup, N.B.; Flor, H.; Gibson, S.; Keefe, F.J.; Mogil, J.S.; Ringkamp, M.; Sluka, K.A.; et al. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: Concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain 2020, 161, 1976–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, P.; McGill, B. The relationship between experience of knee pain and physical activity participation: A scoping review of quantitative studies. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2023, 10, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, R.; Tsvetkov, D.; Dhottar, H.; Davey, J.R.; Mahomed, N.N. Quantifying the pain experience in hip and knee osteoarthritis. Pain Res. Manag. 2010, 15, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uimonen, M.; Repo, J.P.; Grönroos, K.; Häkkinen, A.; Walker, S. Validity and reliability of the motivation for physical activity (RM4-FM) questionnaire. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2021, 17, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurado-Castro, J.M.; Muñoz-López, M.; Ledesma, A.S.; Ranchal-Sanchez, A. Effectiveness of Exercise in Patients with Overweight or Obesity Suffering from Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricke, E.; Dijkstra, A.; Bakker, E.W. Prognostic factors of adherence to home-based exercise therapy in patients with chronic diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Sports Act Living 2023, 5, 1035023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.H.; Lahart, I.; Carlin, A.; Murtagh, E. The Effects of Continuous Compared to Accumulated Exercise on Health: A Meta-Analytic Review. Sports Med. 2019, 49, 1585–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, D.R.; Toth, L.P.; LaMunion, S.R.; Crouter, S.E. Step Counting: A Review of Measurement Considerations and Health-Related Applications. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 1303–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, D.K.; Tudor-Locke, C.; Zhang, Y.; Fielding, R.; LaValley, M.; Felson, D.T.; Gross, K.D.; Nevitt, M.C.; Lewis, C.E.; Torner, J.; et al. Daily walking and the risk of incident functional limitation in knee osteoarthritis: An observational study. Arthritis Care Res. 2014, 66, 1328–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, G.H.; Vinod, S.; Richard, M.J.; Harkey, M.S.; McAlindon, T.E.; Kriska, A.M.; Rockette-Wagner, B.; Eaton, C.B.; Hochberg, M.C.; Jackson, R.D.; et al. Association between Walking for Exercise and Symptomatic and Structural Progression in Individuals with Knee Osteoarthritis: Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative Cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022, 74, 1660–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, R.R.; Hill, J.O. Successful weight loss maintenance. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2001, 21, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Master, H.; Annis, J.; Huang, S.; Beckman, J.A.; Ratsimbazafy, F.; Marginean, K.; Carroll, R.; Natarajan, K.; Harrell, F.E.; Roden, D.M.; et al. Association of step counts over time with the risk of chronic disease in the All of Us Research Program. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2301–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arden, N.K.; Perry, T.A.; Bannuru, R.R.; Bruyère, O.; Cooper, C.; Haugen, I.K.; Hochberg, M.C.; McAlindon, T.E.; Mobasheri, A.; Reginster, J.Y. Non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis: Comparison of ESCEO and OARSI 2019 guidelines. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2021, 17, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannuru, R.R.; Osani, M.C.; Vaysbrot, E.E.; Arden, N.K.; Bennell, K.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A.; Kraus, V.B.; Lohmander, L.S.; Abbott, J.H.; Bhandari, M.; et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2019, 27, 1578–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlindon, T.E.; Bannuru, R.R.; Sullivan, M.C.; Arden, N.K.; Berenbaum, F.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.; Hawker, G.A.; Henrotin, Y.; Hunter, D.J.; Kawaguchi, H.; et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2014, 22, 363–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M.J.; Viechtbauer, W.; Lenssen, A.F.; Hendriks, E.J.; de Bie, R.A. Strength training alone, exercise therapy alone, and exercise therapy with passive manual mobilisation each reduce pain and disability in people with knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review. J. Physiother. 2011, 57, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, M.D. Rehabilitation interventions for pain and disability in osteoarthritis: A review of interventions including exercise, manual techniques, and assistive devices. Orthop. Nurs./Natl. Assoc. Orthop. Nurses 2012, 31, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fransen, M.; McConnell, S.; Hernandez-Molina, G.; Reichenbach, S. Does land-based exercise reduce pain and disability associated with hip osteoarthritis? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2010, 18, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransen, M.; McConnell, S. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, 4, CD004376. [Google Scholar]

- Fransen, M.; McConnell, S.; Harmer, A.R.; Van der Esch, M.; Simic, M.; Bennell, K.L. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: A Cochrane systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 1554–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, F.; Ramos, M.; Cruz, A.L. Effects of exercise on knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Musculoskelet. Care. 2021, 19, 399–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.Y.; Tchai, E. SNJ Effectiveness of aquatic exercise for obese patients with knee osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled trial. PM&R 2010, 2, 723–731. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels, E.M.; Juhl, C.B.; Christensen, R.; Hagen, K.B.; Danneskiold-Samsøe, B.; Dagfinrud, H.; Lund, H. Aquatic exercise for the treatment of knee and hip osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 3, CD005523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.A.; Oh, J.W. Effects of Aquatic Exercises for Patients with Osteoarthritis: Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2022, 10, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.A.; Kokorelias, K.M.; MacDermid, J.C.; Kloseck, M. Education and Social Support as Key Factors in Osteoarthritis Management Programs: A Scoping Review. Arthritis 2018, 2018, 2496190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson, S.V.; Alley, S.J.; Rebar, A.L.; Hayman, M.; Vandelanotte, C.; Schoeppe, S. How are different levels of knowledge about physical activity associated with physical activity behaviour in Australian adults? PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLany, J.P.; Kelley, D.E.; Hames, K.C.; Jakicic, J.M.; Goodpaster, B.H. Effect of physical activity on weight loss, energy expenditure, and energy intake during diet induced weight loss. Obesity 2014, 22, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butryn, M.L.; Crane, N.T.; Lufburrow, E.; Hagerman, C.J.; Forman, E.M.; Zhang, F. The Role of Physical Activity in Long-Term Weight Loss: 36-Month Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Behav. Med. 2023, 57, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraça, E.V.; Encantado, J.; Battista, F.; Beaulieu, K.; Blundell, J.E.; Busetto, L.; van Baak, M.; Dicker, D.; Ermolao, A.; Farpour-Lambert, N.; et al. Effect of exercise training on psychological outcomes in adults with overweight or obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krist, A.H.; Tong, S.T.; Aycock, R.A. DRL Engaging Patients in Decision-Making and Behavior Change to Promote Prevention. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2017, 240, 284–302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Milhorn, H.T. Cardiovascular fitness. Am. Fam. Physician 1982, 26, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mersy, D.J. Health benefits of aerobic exercise. Postgrad. Med. 1991, 90, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mear, E.; Gladwell, V.F.; Pethick, J.T. The Effect of Breaking Up Sedentary Time with Calisthenics on Neuromuscular Function: A Preliminary Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zmerly, H.; El Ghoch, M.; Itani, L.; Kreidieh, D.; Yumuk, V.; Pellegrini, M. Personalized Nutritional Strategies to Reduce Knee Osteoarthritis Severity and Ameliorate Sarcopenic Obesity Indices: A Practical Guide in an Orthopedic Setting. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, M.J.; Driban, J.B.; McAlindon, T.E. Pharmaceutical treatment of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2023, 31, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manyanga, T.; Froese, M.; Zarychanski, R.; Abou-Setta, A.; Friesen, C.; Tennenhouse, M.; Shay, B.L. Pain management with acupuncture in osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement. Altern Med. 2014, 14, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantas, L.O.; Salvini, T.F.; McAlindon, T.E. Knee osteoarthritis: Key treatments and implications for physical therapy. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2021, 25, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.K.T. Cognitive behavioural therapy in pain and psychological disorders: Towards a hybrid future. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 87, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Heuer, C.A. Obesity stigma: Important considerations for public health. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, T. Environments for active lifestyles: Sustainable environments may enhance human health. Environ. Health Insights 2008, 2, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sooknarine-Rajpatty, J.; Auyeung, A.B.; Doyle, F. A Systematic Review Protocol of the Barriers to Both Physical Activity and Obesity Counselling in the Secondary Care Setting as Reported by Healthcare Providers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalle Grave, R.; Calugi, S.; Centis, E.; El Ghoch, M.; Marchesini, G. Cognitive-behavioral strategies to increase the adherence to exercise in the management of obesity. J. Obes. 2011, 2011, 348293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, R.R.; Jeffery, R.W. Benefits of recruiting participants with friends and increasing social support for weight loss and maintenance. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1999, 67, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay Smith, G.; Banting, L.; Eime, R.; O’Sullivan, G.; van Uffelen, J.G.Z. The association between social support and physical activity in older adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilts, M.K.; Horowitz, M.; Townsend, M.S. Goal setting as a strategy for dietary and physical activity behavior change: A review of the literature. Am. J. Health Promot. 2004, 19, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J. JCW Using our understanding of time to increase self-efficacy towards goal achievement. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.J. An Overview of Current Physical Activity Recommendations in Primary Care. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2019, 40, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Master, H.; Thoma, L.M.; Neogi, T.; Dunlop, D.D.; LaValley, M.; Christiansen, M.B.; Voinier, D.; White, D.K. Daily Walking and the Risk of Knee Replacement Over 5 Years Among Adults With Advanced Knee Osteoarthritis in the United States. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 102, 1888–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, E.J.; Massey, A.S.; Prado-Romero, P.N.; Albadawi, S. The Use of Self-Monitoring and Technology to Increase Physical Activity: A Review of the Literature. Perspect. Behav. Sci. 2020, 43, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pae, C.U. Why Systematic Review rather than Narrative Review? Psychiatry Investig. 2015, 12, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukull, W.A.; Ganguli, M. Generalizability: The trees, the forest, and the low-hanging fruit. Neurology 2012, 78, 1886–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, F.; Snyder-Mackler, L.; Zeni, J. Physical exercise after knee arthroplasty: A systematic review of controlled trials. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2013, 49, 877–892. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Veronese, N.; Honvo, G.; Bruyère, O.; Rizzoli, R.; Barbagallo, M.; Maggi, S.; Smith, L.; Sabico, S.; Al-Daghri, N.; Cooper, C.; et al. Knee osteoarthritis and adverse health outcomes: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2023, 35, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Lu, H.; He, L.; Ma, C.; Zhao, Z. Burden of Knee Osteoarthritis in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990-2019: Results From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Arthritis Care Res. 2023, 75, 2489–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidell, J.C.; Halberstadt, C. The global burden of obesity and the challenges of prevention. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 66, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clynes, M.A.; Jameson, K.A.; Edwards, M.H.; Cooper, C.; Dennison, E.M. Impact of osteoarthritis on activities of daily living: Does joint site matter? Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019, 31, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accettura, A.J.; Brenneman, E.C.; Stratford, P.W. MRM Knee Extensor Power Relates to Mobility Performance in People with Knee Osteoarthritis: Cross-Sectional Analysis. Phys. Ther. 2015, 95, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Song, J.; Hootman, J.M.; Semanik, P.A.; Chang, R.W.; Sharma, L.; van Horn, L.; Bathon, J.M.; Eaton, C.B.; Hochberg, M.C.; et al. Obesity and other modifiable factors for physical inactivity measured by accelerometer in adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2013, 65, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Obesity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tool | Cut-Off Points | ||

| Females | Males | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) * | ≥25–30 kg/m2 | ≥25–30 kg/m2 | |

| WC (cm) * | >80–88 cm | 90–102 cm | |

| BF (%) * | 38–43% | 26–31% | |

| * Age, ethnicity and gender-specific cut-off points | |||

| Kellgren and Lawrence KOA Classification System | |||

| Grade 0 | No radiological findings of OA | ||

| Grade I | Doubtful joint space narrowing and possible osteophytic lipping | ||

| Grade II | Certain osteophytes and possible joint space narrowing | ||

| Grade III | Moderate multiple osteophytes, certain narrowing of joint space, some sclerosis and possible deformity of bone ends | ||

| Grade IV | Large osteophytes, marked narrowing of joint space, severe sclerosis and certain deformity of bone ends | ||

| Item | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| In the past, the patient suffered from one of the following diseases: heart infarction, angina pectoris, heart arrest, cardiac arrhythmia, cardiac valves disease | ||

| Has blood hypertension | ||

| Has been followed up by a cardiologist | ||

| Had an ictus or any neurological problem | ||

| Has type 1 or 2 diabetes | ||

| Has endocrine metabolic diseases | ||

| Has liver or renal diseases | ||

| Has orthopedic or skeletal problems | ||

| In the past, had any health problem considered a barrier to doing physical activity | ||

| The patient thinks that physical activity may be harmful or risky for him/her |

| PA Program | Effect | Evidence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active lifestyle (steps/day) |

|

| |

| Land-based exercise (Time/session/week) |

|

| |

| Water-based exercise (Time/session/week) |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zmerly, H.; Milanese, C.; El Ghoch, M.; Itani, L.; Tannir, H.; Kreidieh, D.; Yumuk, V.; Pellegrini, M. Personalized Physical Activity Programs for the Management of Knee Osteoarthritis in Individuals with Obesity: A Patient-Centered Approach. Diseases 2023, 11, 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases11040182

Zmerly H, Milanese C, El Ghoch M, Itani L, Tannir H, Kreidieh D, Yumuk V, Pellegrini M. Personalized Physical Activity Programs for the Management of Knee Osteoarthritis in Individuals with Obesity: A Patient-Centered Approach. Diseases. 2023; 11(4):182. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases11040182

Chicago/Turabian StyleZmerly, Hassan, Chiara Milanese, Marwan El Ghoch, Leila Itani, Hana Tannir, Dima Kreidieh, Volkan Yumuk, and Massimo Pellegrini. 2023. "Personalized Physical Activity Programs for the Management of Knee Osteoarthritis in Individuals with Obesity: A Patient-Centered Approach" Diseases 11, no. 4: 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases11040182

APA StyleZmerly, H., Milanese, C., El Ghoch, M., Itani, L., Tannir, H., Kreidieh, D., Yumuk, V., & Pellegrini, M. (2023). Personalized Physical Activity Programs for the Management of Knee Osteoarthritis in Individuals with Obesity: A Patient-Centered Approach. Diseases, 11(4), 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases11040182