Real-Time Robotic Navigation with Smooth Trajectory Using Variable Horizon Model Predictive Control

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Related Work

1.2.1. Model Predictive Control

1.2.2. Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm

1.3. Contribution

- We propose a variable prediction horizon model predictive control scheme based on the change in obstacle distance to improve trajectory smoothness and real-time performance during navigation.

- We combine the multi-objective evolutionary algorithm NSGA-II with model predictive control to obtain optimal parameters and achieve better control performance. Compared with traditional weight parameter adjustment methods, we mainly focus on optimization in the prediction horizon.

- We validate the effectiveness of the proposed method in balancing real-time performance and trajectory smoothness through both simulation experiments and real-world scenario testing.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. System Model

2.2. Multiple Shooting

2.3. Warm Start

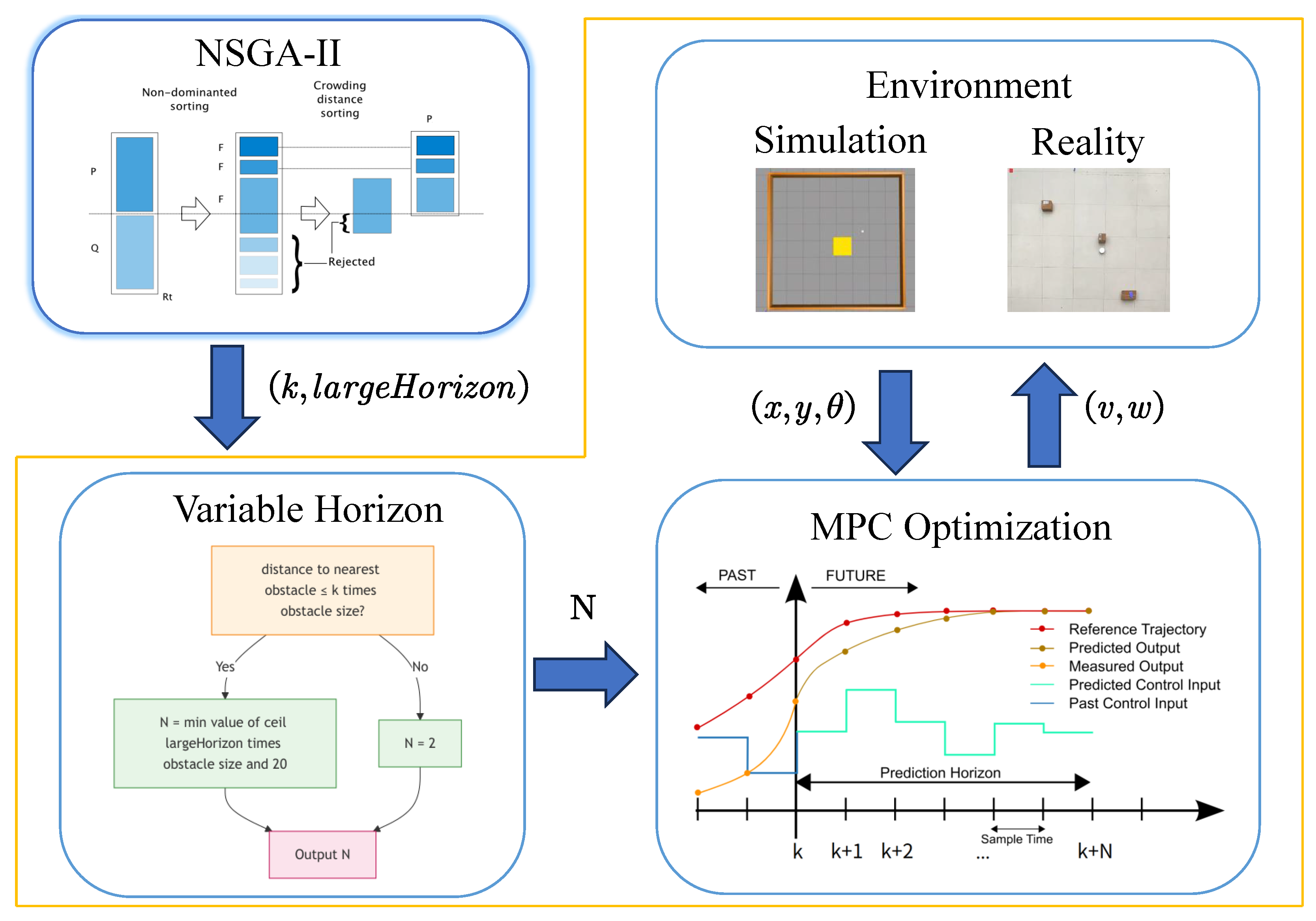

3. Implementation

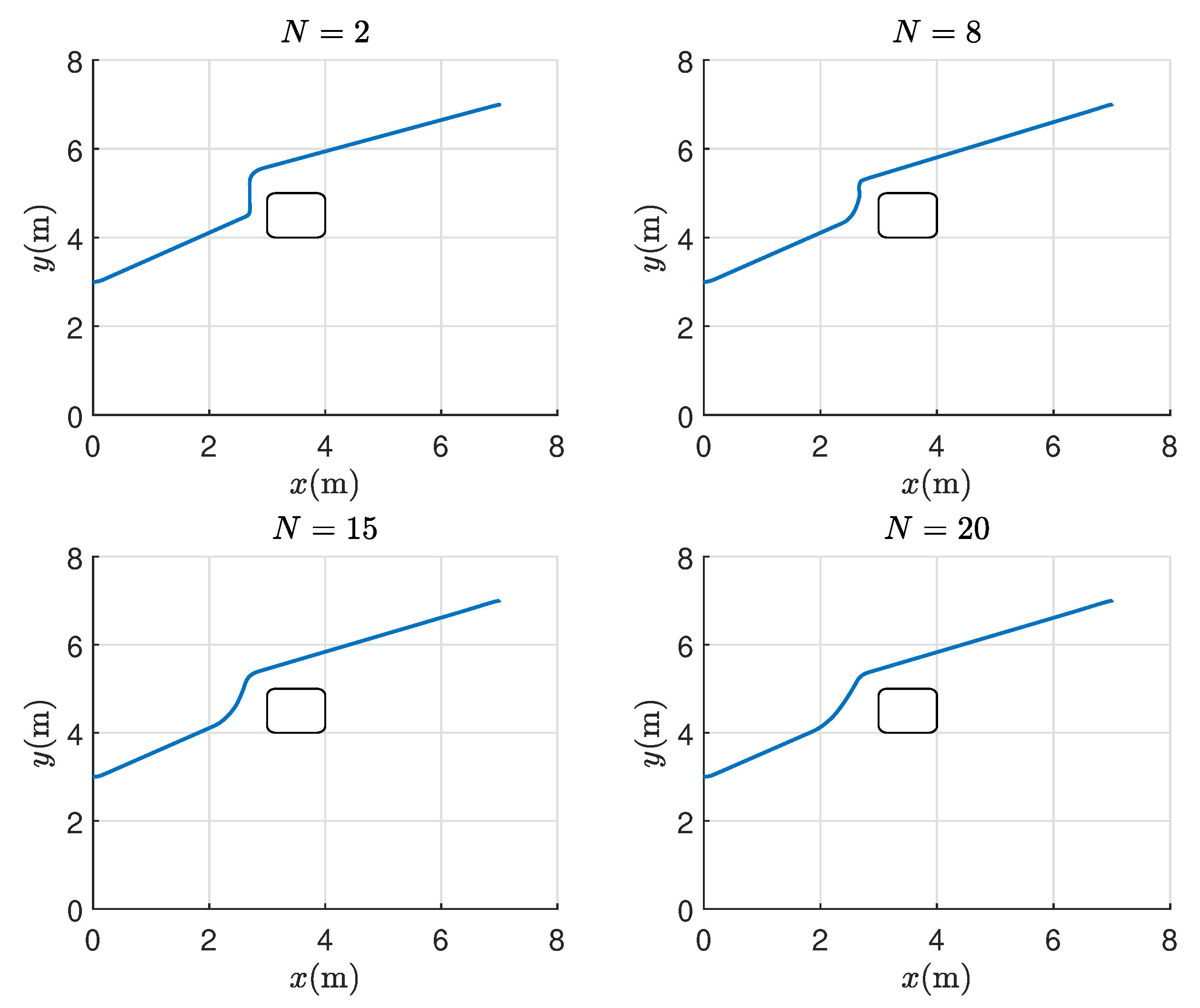

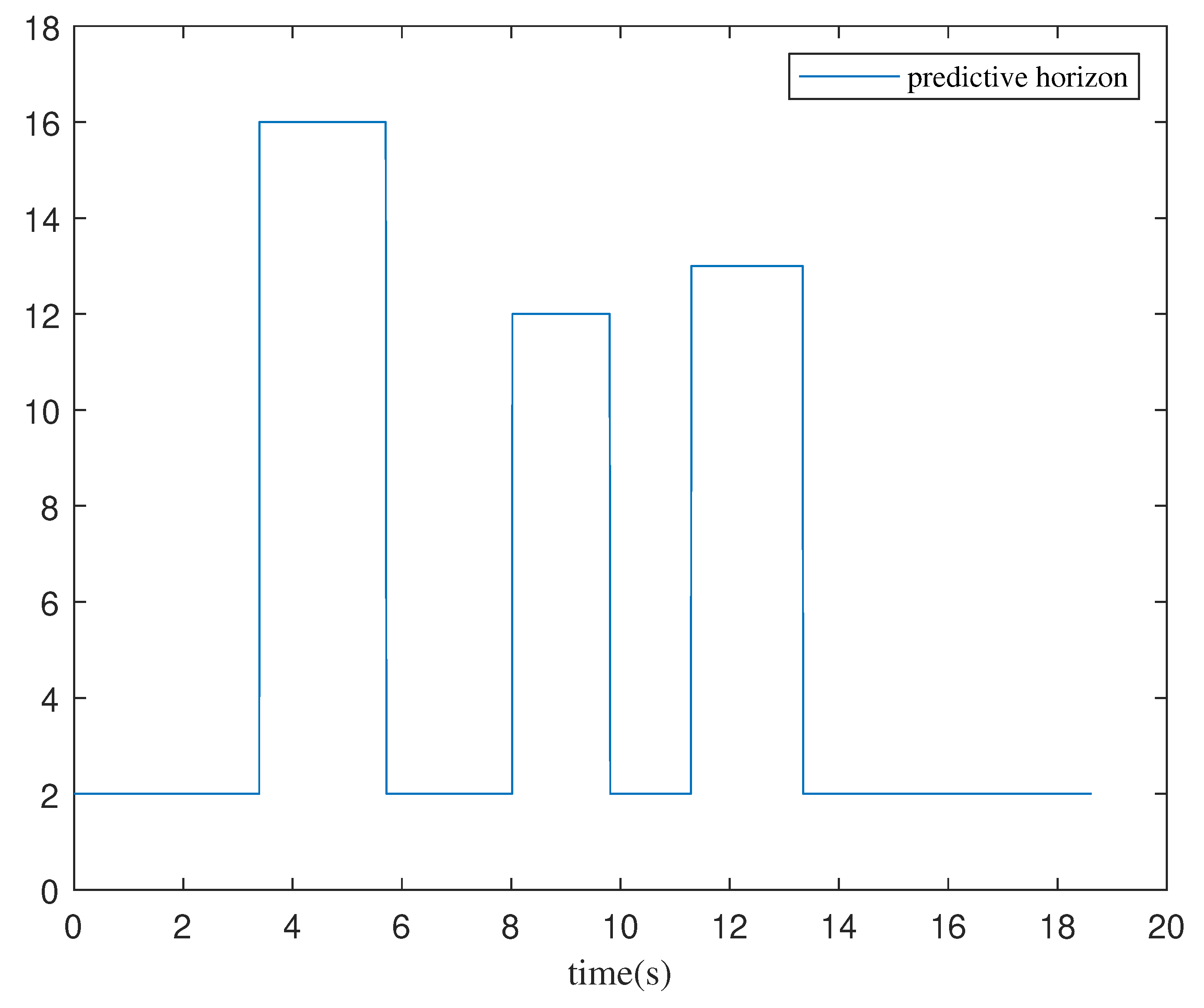

3.1. Variable Prediction Horizon Control Scheme

| Algorithm 1 Variable Prediction Horizon Scheme |

|

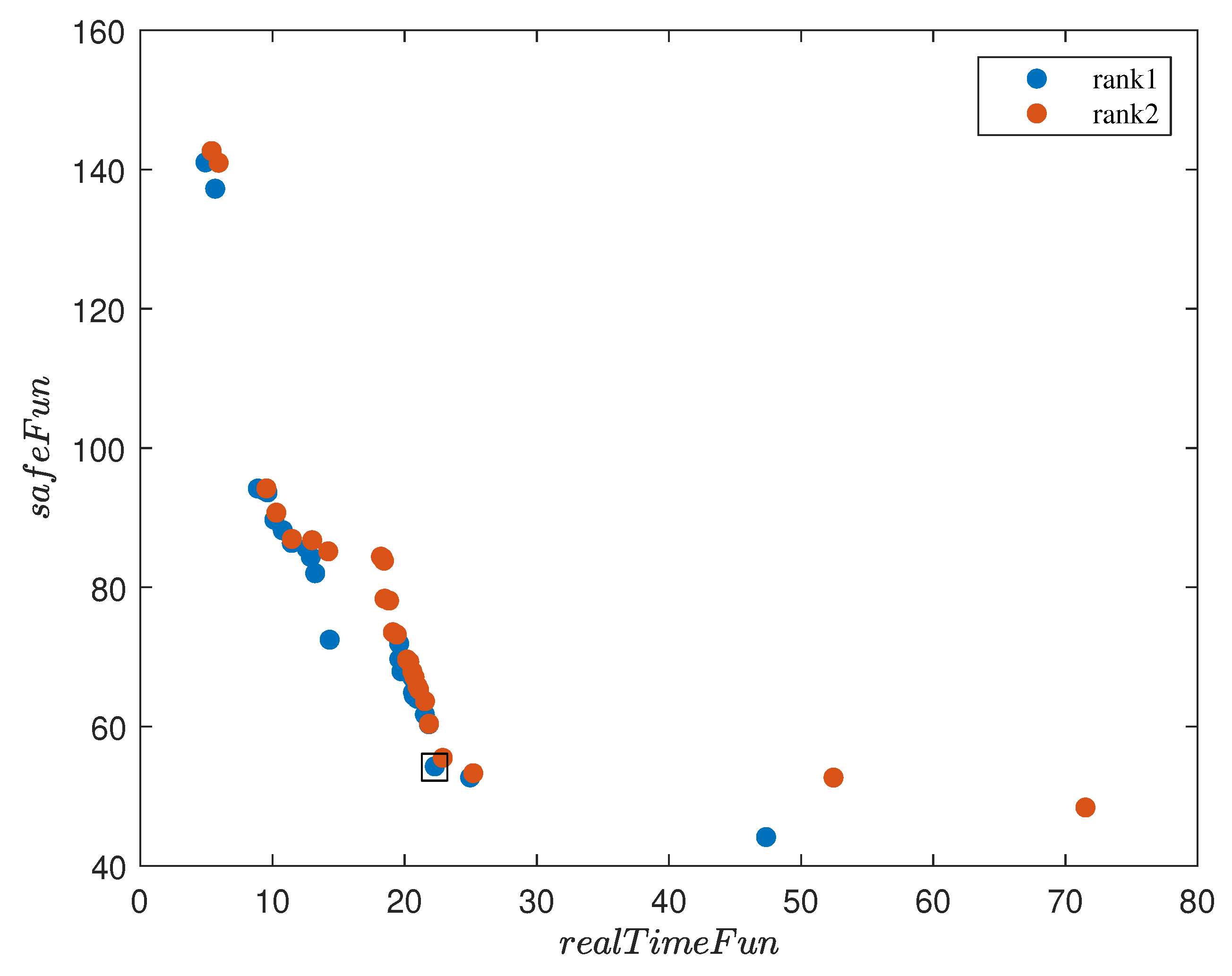

3.2. Optimal Control Parameter Selection

| Algorithm 2 NSGA-II Based Adaptive Horizon MPC Parameter Optimization |

|

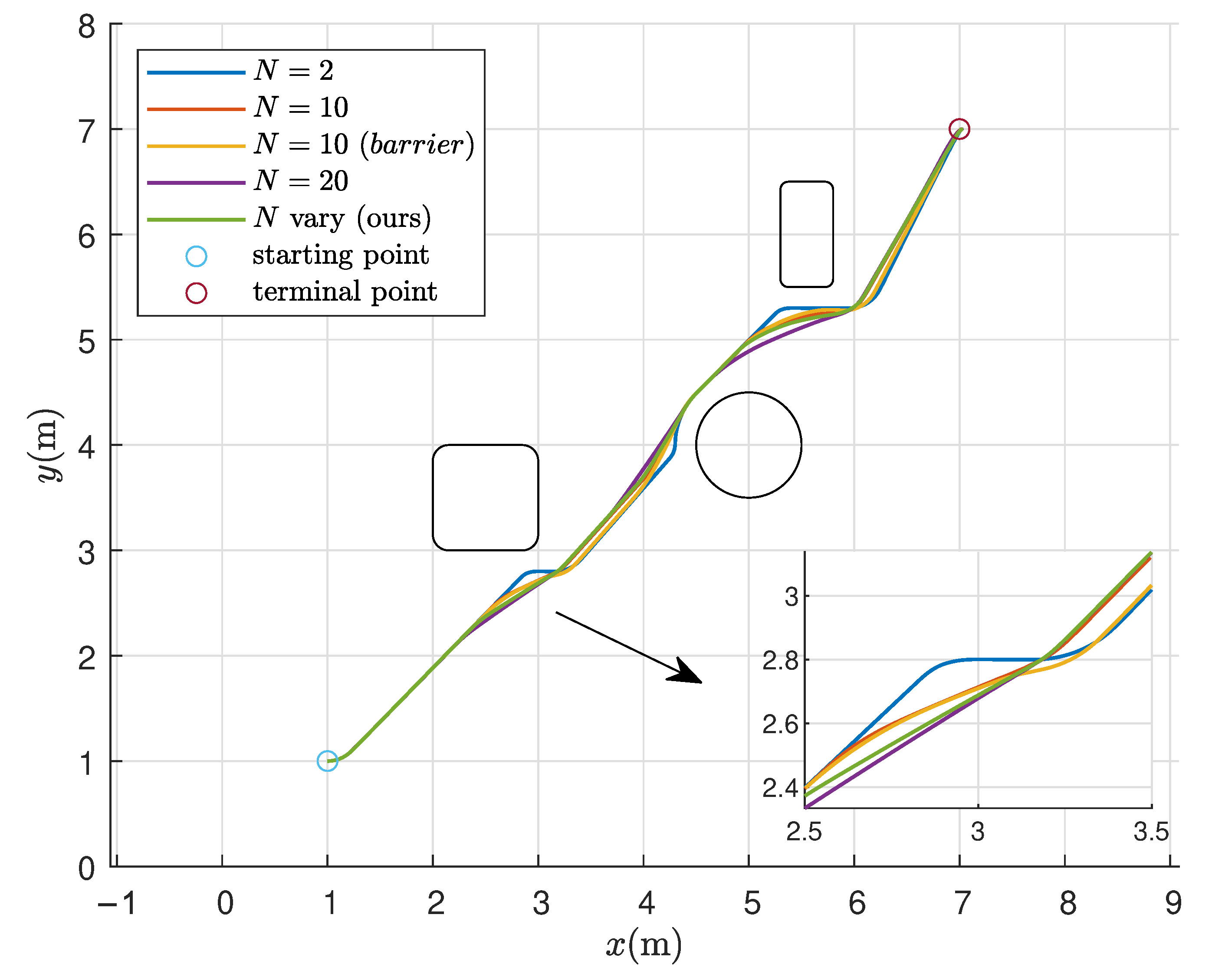

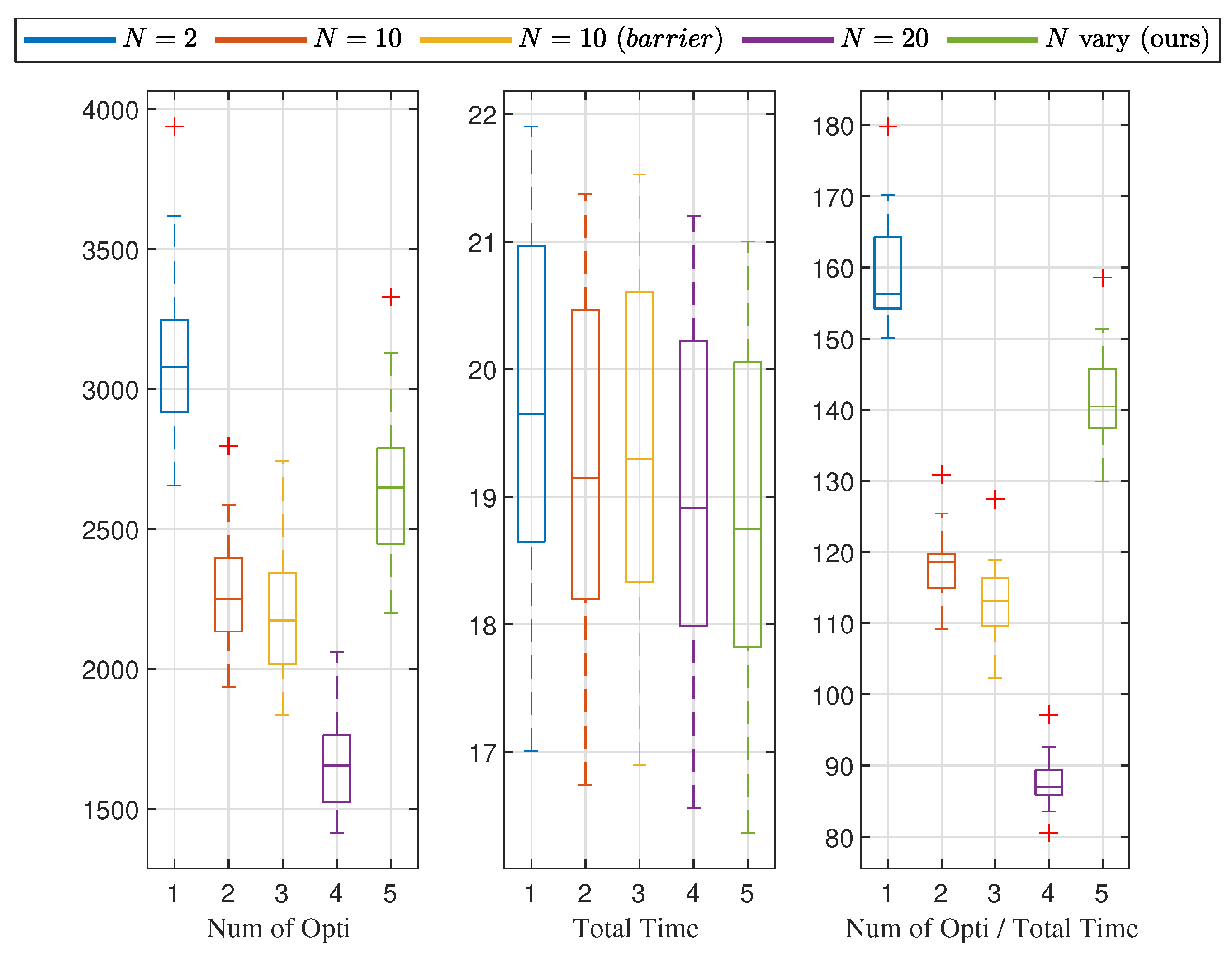

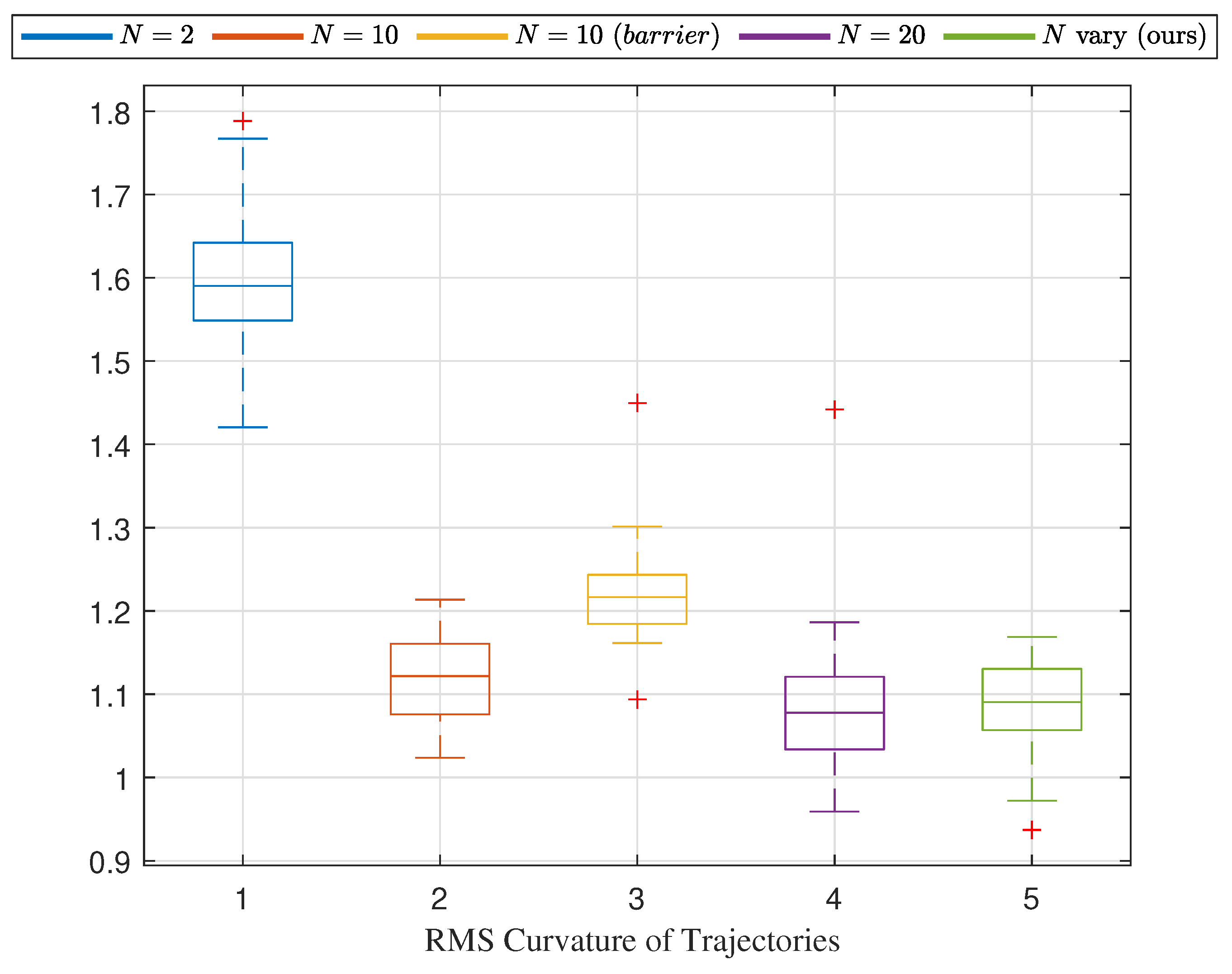

4. Experiments

4.1. Simulation Scenario

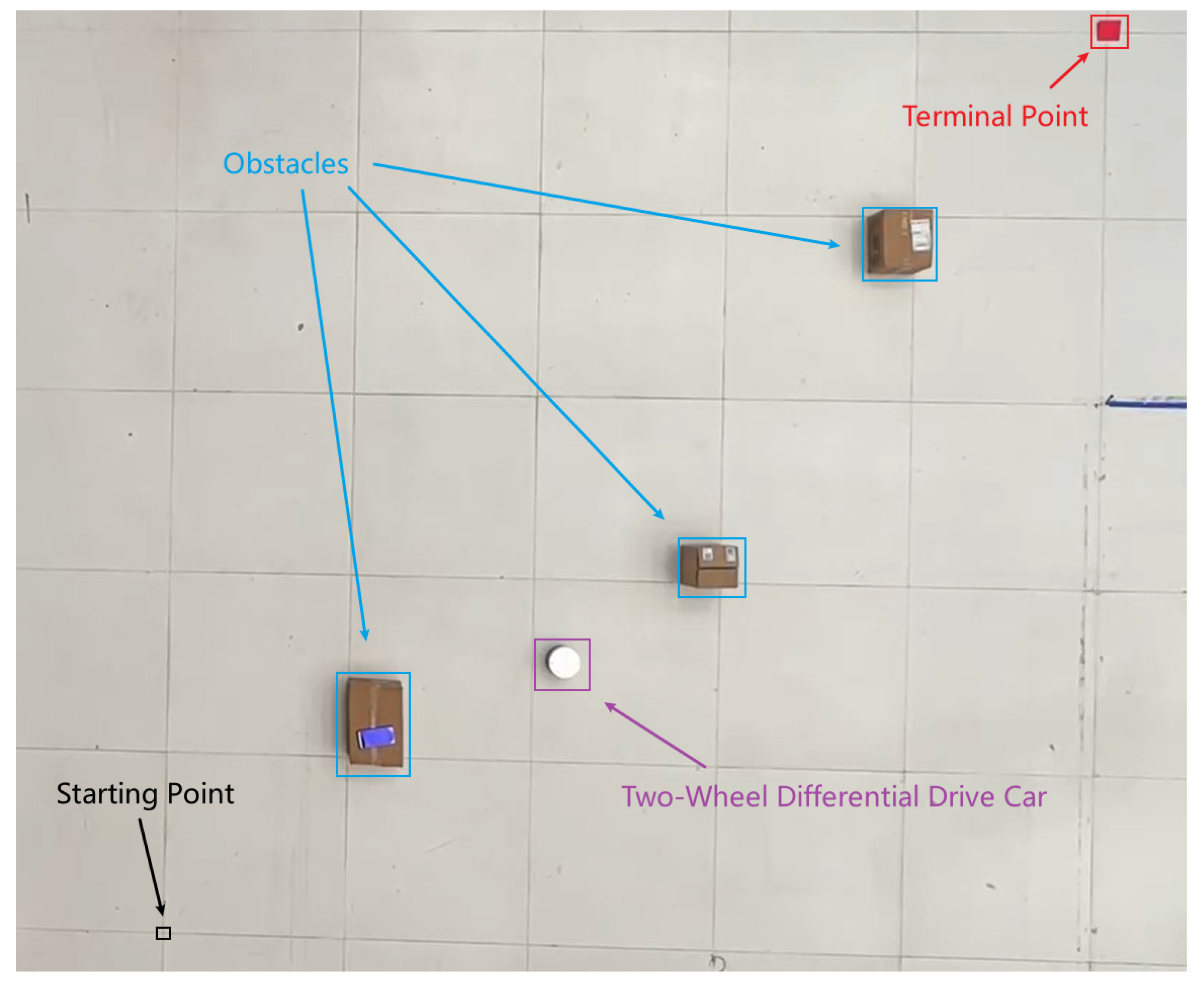

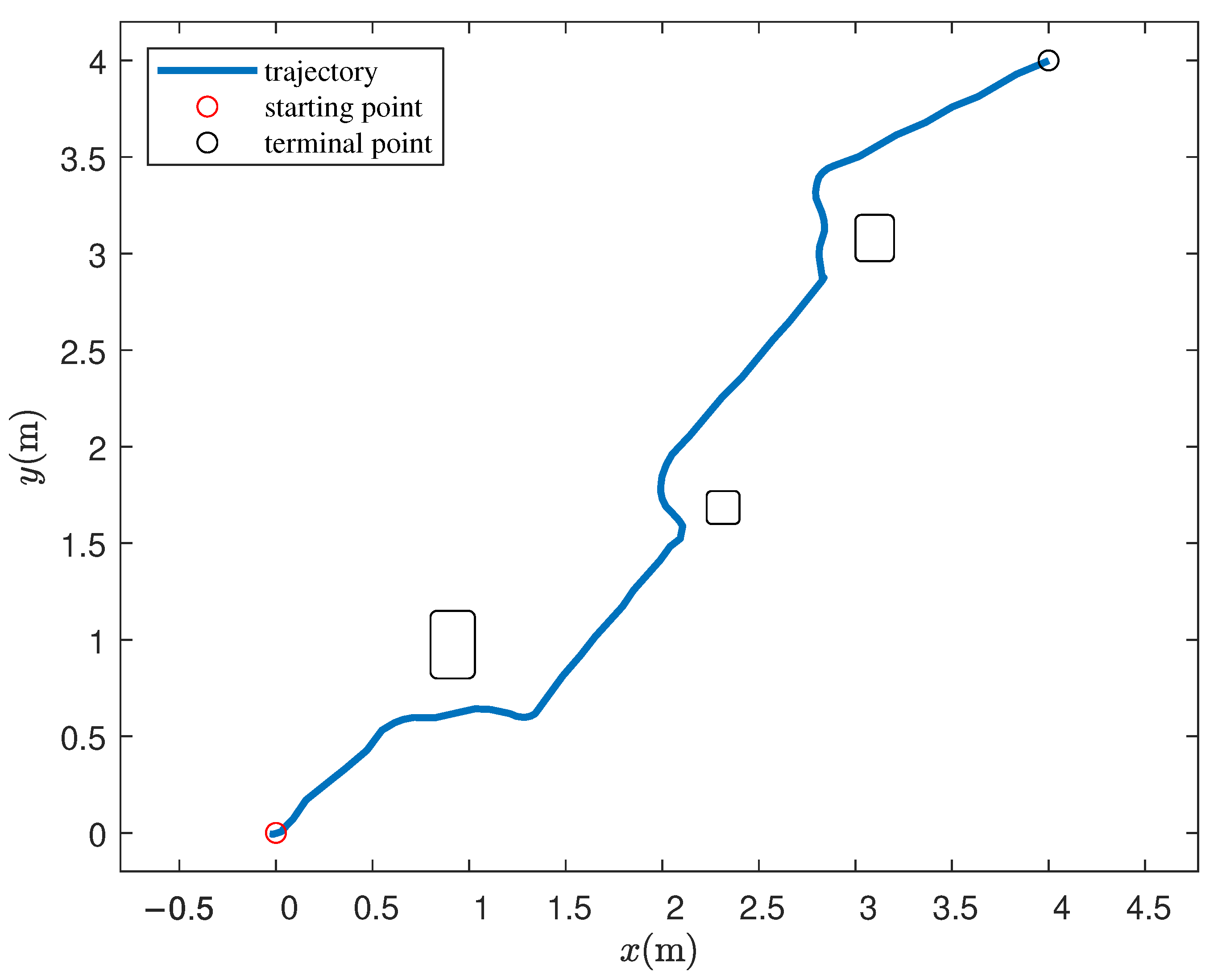

4.2. Real-World Scenario

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hart, P.E.; Nilsson, N.J.; Raphael, B. A formal basis for the heuristic determination of minimum cost paths. IEEE Trans. Syst. Sci. Cybern. 1968, 4, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, T.; Guan, J.; Shi, S. Orchard Robot Navigation via an Improved RTAB-Map Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stentz, A. The focussed d* algorithm for real-time replanning. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–25 August 1995; Volume 95, pp. 1652–1659. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrożkiewicz, M.; Bonar, B.; Buratowski, T.; Małka, P. Advanced probabilistic roadmap path planning with adaptive sampling and smoothing. Electronics 2025, 14, 3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Pang, T.; Zhang, W.; Liao, W.; Du, T. Research on Path Planning Based on Multi-Dimensional Optimized RRT Algorithm. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, D.; Burgard, W.; Thrun, S. The dynamic window approach to collision avoidance. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 1997, 4, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, J.; Koren, Y. The vector field histogram-fast obstacle avoidance for mobile robots. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 1991, 7, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonko, J.; Ruiperez-Campillo, S.; Cabero-Vidal, G.; Rooney, C.; Ehnesh, M.; Millet-Roig, J.; Castells, P.; Lambiase, P. Vector Field Heterogeneity (VFH) as a novel quantitative marker of electrical disarray in Arrhythmogenic CardioMyopathy (ACM) with ventricular tachycardia. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, ehae666.654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, O. Real-time obstacle avoidance for manipulators and mobile robots. Int. J. Robot. Res. 1986, 5, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, M.; Ding, W.; Li, S.; Li, G.; Li, Z.; Knoll, A. Efficient online planning and robust optimal control for nonholonomic mobile robot in unstructured environments. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2024, 8, 3559–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratliff, N.; Zucker, M.; Bagnell, J.A.; Srinivasa, S. CHOMP: Gradient optimization techniques for efficient motion planning. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Kobe, Japan, 12–17 May 2009; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 489–494. [Google Scholar]

- Schulman, J.; Ho, J.; Lee, A.X.; Awwal, I.; Bradlow, H.; Abbeel, P. Finding locally optimal, collision-free trajectories with sequential convex optimization. In Proceedings of the Robotics: Science and Systems, Berlin, Germany, 24–28 June 2013; Volume 9, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Benders, D.; Köhler, J.; Niesten, T.; Babuška, R.; Alonso-Mora, J.; Ferranti, L. Embedded hierarchical MPC for autonomous navigation. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2025, 41, 3556–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Xie, Y.; Xiong, T.; Wang, C. Autonomous Navigation of Mobile Robots: A Hierarchical Planning–Control Framework with Integrated DWA and MPC. Sensors 2025, 25, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Zhang, B.; Sreenath, K. Safety-critical model predictive control with discrete-time control barrier function. In Proceedings of the 2021 American Control Conference (ACC), New Orleans, LA, USA, 25–28 May 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 3882–3889. [Google Scholar]

- Breeden, J.; Panagou, D. Predictive control barrier functions for online safety critical control. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 61st Conference on Decision and Control (CDC), Cancun, Mexico, 6–9 December 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 924–931. [Google Scholar]

- Bøhn, E.; Gros, S.; Moe, S.; Johansen, T.A. Reinforcement learning of the prediction horizon in model predictive control. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2021, 54, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quartullo, R.; Bianchini, G.; Garulli, A.; Giannitrapani, A. Robust variable-horizon MPC with adaptive terminal constraints. Automatica 2025, 179, 112465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Lai, J.; Li, P.; Awad, O.I.; Zhu, Y. Prediction horizon-varying model predictive control (MPC) for autonomous vehicle control. Electronics 2024, 13, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seder, M.; Klančar, G. Convergent wheeled robot navigation based on an interpolated potential function and gradient. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2024, 177, 104712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Li, D. Model predictive control and its application in agriculture: A review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 151, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, G.; Li, Y.; Li, P.; Ji, Y.; Wang, C.; Shen, Y. Real-time whole-body collision avoidance and path following of a snake robot through MPC-based optimization strategies. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Detroit, MI, USA, 1–5 October 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 2362–2367. [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings, J.B.; Mayne, D.Q.; Diehl, M. Model Predictive Control: Theory, Computation, and Design; Nob Hill Publishing: Madison, WI, USA, 2017; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Brito, B.; Floor, B.; Ferranti, L.; Alonso-Mora, J. Model predictive contouring control for collision avoidance in unstructured dynamic environments. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2019, 4, 4459–4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Wu, W.; Lin, Y.; Shen, S. Online safe trajectory generation for quadrotors using fast marching method and bernstein basis polynomial. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, Australia, 21–25 May 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 344–351. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F.; Lin, Y.; Shen, S. Gradient-based online safe trajectory generation for quadrotor flight in complex environments. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–28 September 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 3681–3688. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, B.T.; How, J.P. Aggressive 3-D collision avoidance for high-speed navigation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017; pp. 5759–5765. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Miao, Z.; Wang, X.; He, W. Dual model predictive control of multiple quadrotors with formation maintenance and collision avoidance. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 16037–16046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayne, D. A second-order gradient method for determining optimal trajectories of non-linear discrete-time systems. Int. J. Control 1966, 3, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.Z.; Shoemaker, C.A. Advantages of Differential Dynamic Programming over Newton’s Method for Discrete-Time Optimal Control Problems; Technical Report; Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, H.G.; Plitt, K.J. A multiple shooting algorithm for direct solution of optimal control problems. IFAC Proc. Vol. 1984, 17, 1603–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, M.; Bock, H.G.; Diedam, H.; Wieber, P.B. Fast direct multiple shooting algorithms for optimal robot control. In Fast Motions in Biomechanics and Robotics: Optimization and Feedback Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 65–93. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Yu, W.; Zhang, T.; Wensing, P.M. A unified perspective on multiple shooting in differential dynamic programming. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Detroit, MI, USA, 1–5 October 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 9978–9985. [Google Scholar]

- Marcucci, T.; Tedrake, R. Warm start of mixed-integer programs for model predictive control of hybrid systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2020, 66, 2433–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Pei, Y.; Li, J. A survey on search strategy of evolutionary multi-objective optimization algorithms. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Zhang, C.; Chen, S.; Dai, Q.; Yu, H.; Yang, G.; Yu, L. Multi-objective optimal trajectory planning for woodworking manipulator and worktable based on the INSGA-II algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2024, 15, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, H. MOEA/D: A multiobjective evolutionary algorithm based on decomposition. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2007, 11, 712–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerich, M.; Beume, N.; Naujoks, B. An EMO algorithm using the hypervolume measure as selection criterion. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Evolutionary Multi-Criterion Optimization, Guanajuato, Mexico, 9–11 March 2005; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 62–76. [Google Scholar]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazani, M.R.C.; Karkoub, M.; Asadi, H.; Lim, C.P.; Liew, A.W.C.; Nahavandi, S. Multi-objective NSGA-II for weight tuning of a nonlinear model predictive controller in autonomous vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Prague, Czech Republic, 9–12 October 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 2820–2826. [Google Scholar]

- Arshad, M.H.; Abido, M.A.; Salem, A.; Elsayed, A.H. Weighting factors optimization of model predictive torque control of induction motor using NSGA-II with TOPSIS decision making. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 177595–177606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, J.A.E.; Gillis, J.; Horn, G.; Rawlings, J.B.; Diehl, M. CasADi—A software framework for nonlinear optimization and optimal control. Math. Program. Comput. 2019, 11, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wächter, A.; Biegler, L.T. On the implementation of an interior-point filter line-search algorithm for large-scale nonlinear programming. Math. Program. 2006, 106, 25–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Z.; Yan, Z.; Lei, X.; Lu, Z.; Lan, B.; Wang, X.; Liang, B. Dynamic Control Barrier Function-based Model Predictive Control to Safety-Critical Obstacle-Avoidance of Mobile Robot. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), London, UK, 29 May–2 June 2023; pp. 3679–3685. [Google Scholar]

- Thrun, S.; Burgard, W.; Fox, D. Probabilistic Robotics; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, C.; Xie, D.; Wu, L.; Tang, X.; Zhang, H. An Improved Adaptive Monte Carlo Localization Algorithm Integrated with a Virtual Motion Model. Sensors 2025, 25, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Num of Opti | Total Time (s) | Num of Opti/Total Time | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3126.5 | 19.654 | 159 | |

| 2272.3 | 19.173 | 118.48 | |

| ) | 2188.9 | 19.318 | 113.16 |

| 1664.2 | 18.963 | 87.694 | |

| N vary | 2663.9 | 18.783 | 141.67 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, G.; Ma, G.; Wang, D.; Bai, K.; Luo, W.; Zhuang, J.; Fan, Z. Real-Time Robotic Navigation with Smooth Trajectory Using Variable Horizon Model Predictive Control. Electronics 2026, 15, 603. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030603

Wang G, Ma G, Wang D, Bai K, Luo W, Zhuang J, Fan Z. Real-Time Robotic Navigation with Smooth Trajectory Using Variable Horizon Model Predictive Control. Electronics. 2026; 15(3):603. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030603

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Guopeng, Guofu Ma, Dongliang Wang, Keqiang Bai, Weicheng Luo, Jiafan Zhuang, and Zhun Fan. 2026. "Real-Time Robotic Navigation with Smooth Trajectory Using Variable Horizon Model Predictive Control" Electronics 15, no. 3: 603. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030603

APA StyleWang, G., Ma, G., Wang, D., Bai, K., Luo, W., Zhuang, J., & Fan, Z. (2026). Real-Time Robotic Navigation with Smooth Trajectory Using Variable Horizon Model Predictive Control. Electronics, 15(3), 603. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15030603