i-Game: Redefining Cultural Heritage Through Inclusive Game Design and Advanced Technologies

Abstract

1. Introduction

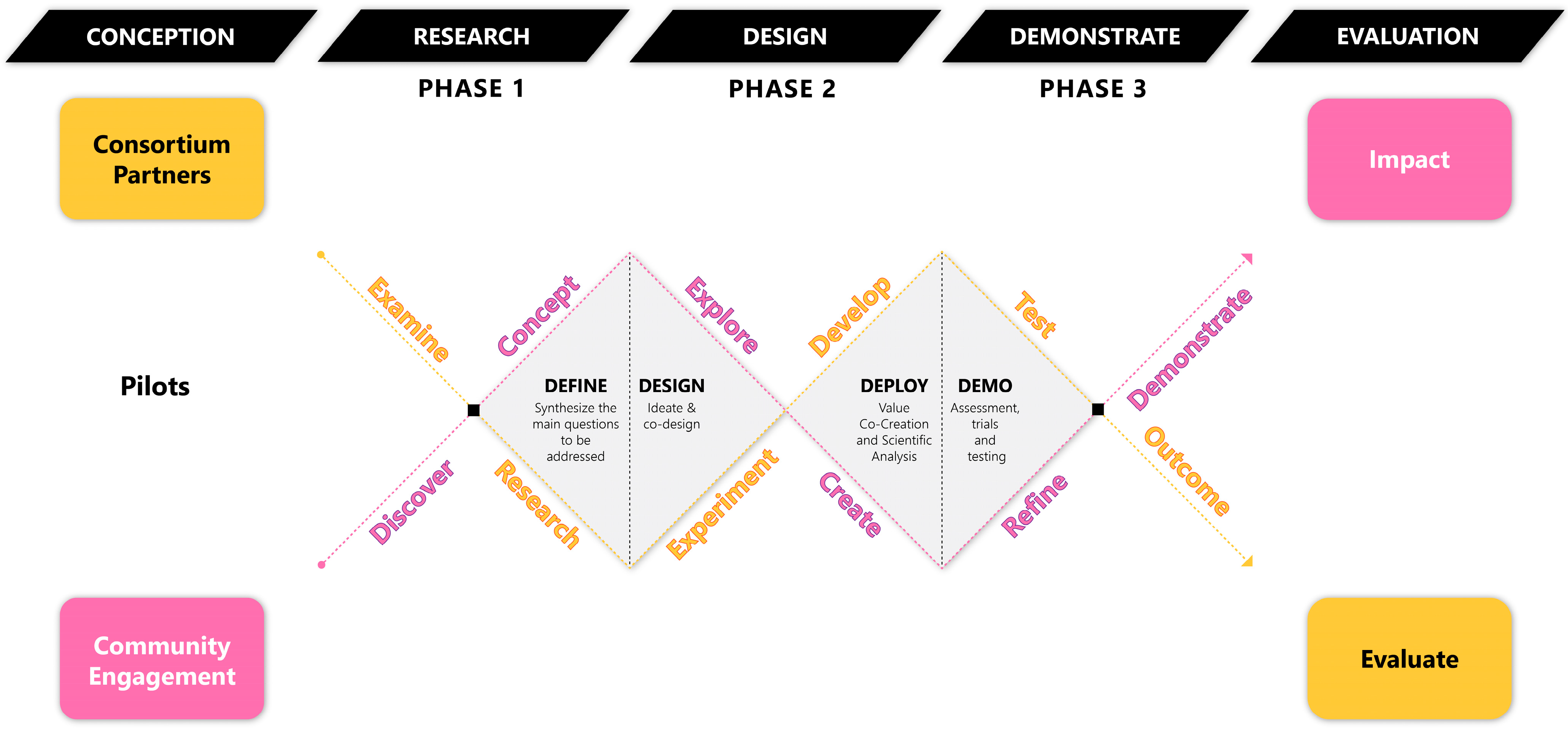

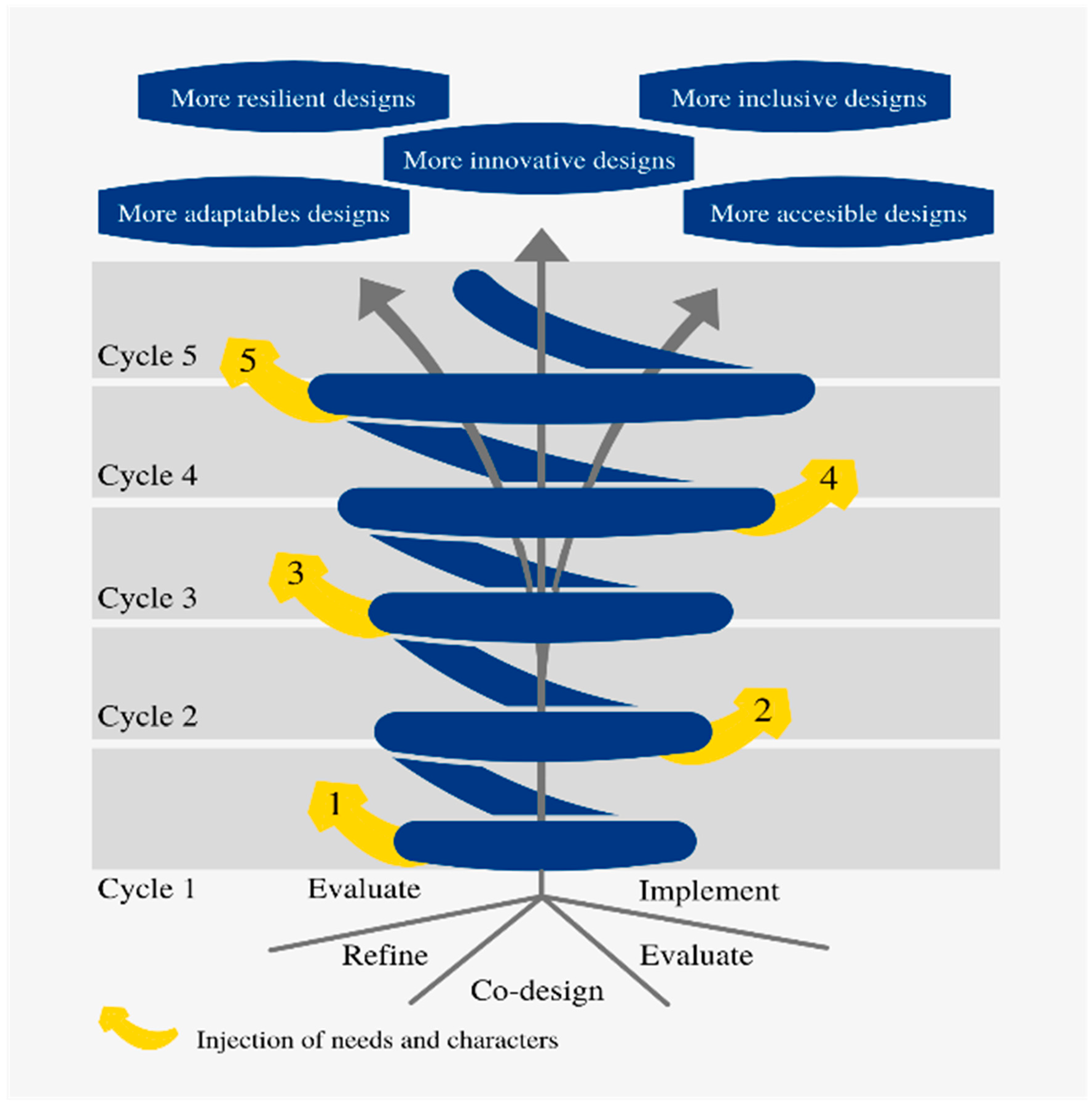

2. Literature Review: Collaborative Platforms for Game Design

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Requirement Analysis and Design

3.2. Development of the Co-Creation Platform, AI, XAI, and VR Plugins

- Pathfinding: Identifying the shortest route between points for character navigation.

- Character design: Creating engaging, lifelike characters.

- Game balance: Optimizing strategies to ensure fair competition among players.

- General patterns in decision-making (e.g., how the NPC adapts its responses based on a player’s interaction style).

- Specific actions (e.g., why an NPC highlights certain cultural artifacts over others).

- Adjustments based on fairness and inclusivity (e.g., preventing AI biases that could misrepresent historical events).

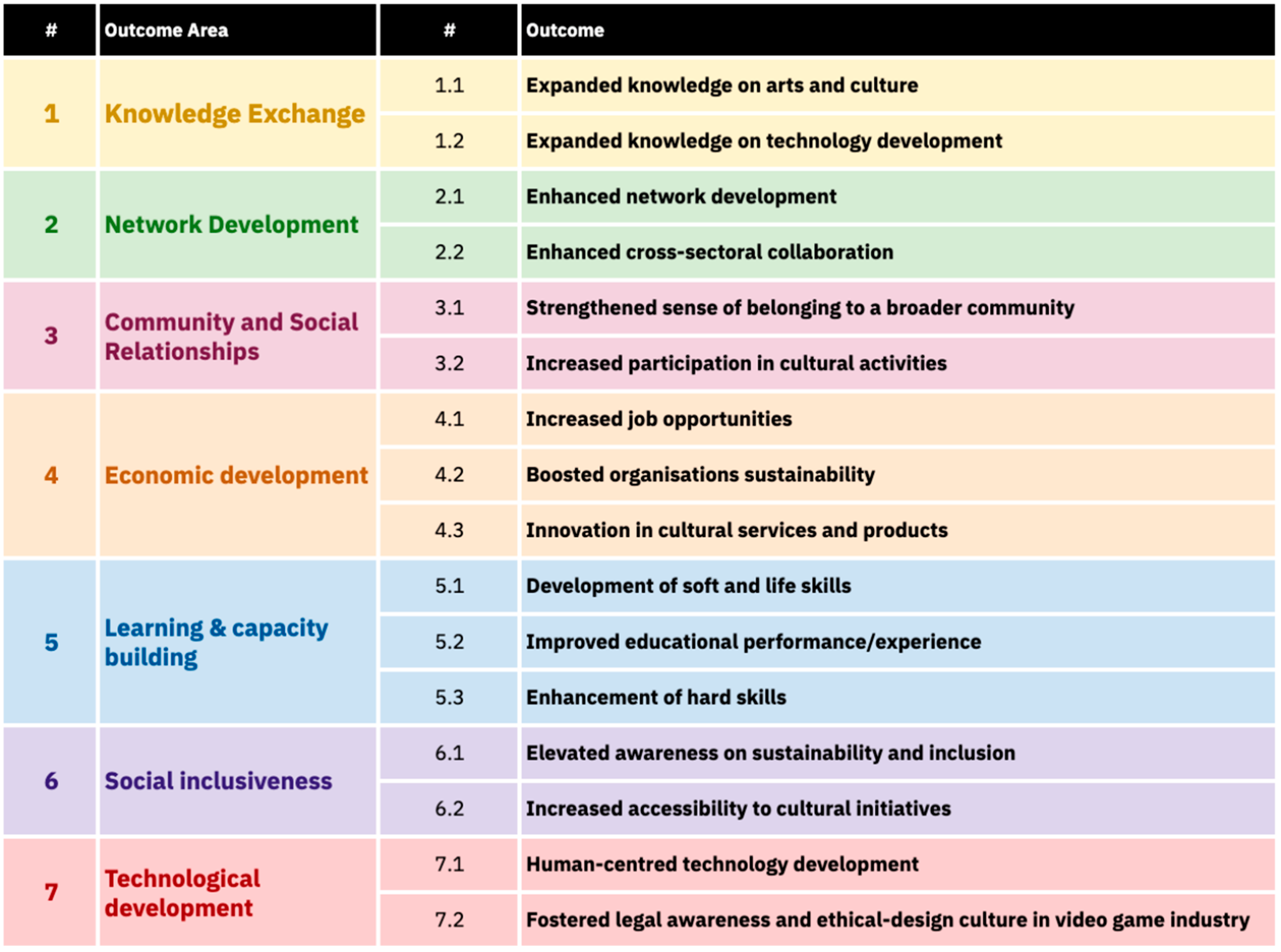

3.3. Evaluation and Impact Assessment

- Museums/CCIs institutions/professionals (TG1): These stakeholders are essential for integrating cultural elements into game development, thereby enhancing cultural preservation and innovation and increasing visitor experience and social innovation. Expected impacts include improved cultural engagement and the adoption of advanced technological solutions in preserving cultural heritage and making it more approachable.

- Museums/CCIs visitors/customers (TG2): Visitors and customers will benefit from enriched cultural experiences through gamified interactions, leading to increased cultural literacy, engagement, and sense of cultural belonging and well-being.

- Textile and fashion industry/professionals (TG3): This group will experience enhanced creativity and innovation in cultural services and products, improving sustainability and integrating cultural and gamified narratives into fashion design.

- Textile and Fashion customers (TG4): Customers will have greater access to innovative, sustainable fashion products enriched by cultural elements, promoting cultural appreciation and sustainable consumption and enhancing their own creativity.

- Game players (TG5): As primary beneficiaries, game players will enjoy enhanced gaming experiences that are culturally enriched and educational, fostering broader cultural awareness and knowledge.

- Game co-creators (TG6): Co-creators will benefit from collaborative opportunities, enhancing their creative and technical skills through participation in game development processes and create a sense of belonging also for underrepresented groups.

- Game industry (TG7): Industry stakeholders will see advancements in technology and innovation, promoting ethical practices and sustainable growth within the industry.

- Citizens (TG8): The broader public will experience increased cultural engagement and participation in community activities, fostering social cohesion and a sense of belonging.

- Policy makers (TG9): Policy makers will be equipped with insights from the project’s outcomes, aiding in the development of policies that support innovation, cultural preservation, and sustainability.

- SMEs (TG10): Small and medium enterprises will benefit from enhanced networking opportunities, resource sharing, and economic growth through participation in innovative projects.

- Higher education and research institutions (TG11): These institutions will gain from enhanced knowledge exchange and collaborative research opportunities, fostering academic and practical advancements.

- Social economy organizations (TG12): SEOs will benefit from increased awareness and integration of sustainability and inclusiveness practices, promoting social equity and innovative solutions.

3.3.1. Exploring Textile Heritage, Sustainability, and Urban Memory Through Gamified Experiences

3.3.2. Gamifying Sustainability and Circular Consumption

3.3.3. Driving Digital Innovation and Sustainability in Central Macedonia’s Textile Industry Through Digital Games

3.4. Ethical Considerations and Open Science

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Parliament. Esports and Video Games Resolution; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2022.

- Mortara, M.; Catalano, C.E.; Bellotti, F.; Fiucci, G.; Houry-Panchetti, M.; Petridis, P. Learning cultural heritage by serious games. J. Cult. Herit. 2014, 15, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siri, A. Emerging Trends and Future Directions in Artificial Intelligence for Museums: A Comprehensive Bibliometric Analysis Based on Scopus (1983–2024). Geopolit. Soc. Secur. Freedom J. 2024, 7, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Debuch, H.; Iovino, S.; Parenti, G.; Strangis, L. The Virtual Museum: How Technology and Virtual Reality May Help Protect and Promote Cultural Heritage. In Heritage in War and Peace: Legal and Political Perspectives for Future Protection; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 149–164. [Google Scholar]

- Padaya, A.; Chbaklo, H. Innovation & Integration of Video Games in Education. Bournem. Univ. 2022, 2022, 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Squire, K.D. Video games and education: Designing learning systems for an interactive age. Educ.Technol. 2008, 48, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- McGonigal, J. Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World; Jonathan Cape: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, E. Gendered identities at Play: Case studies of two women playing Morrowind. Games Cult. 2007, 2, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinkuehler, C.; Duncan, S. Scientific habits of mind in virtual worlds. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2008, 17, 530–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, G.T. Video games, gender, diversity, and learning as cultural practice: Implications for equitable learning and computing participation through games. Educ. Technol. 2017, 57, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Westera, W.; Prada, R.; Mascarenhas, S.; Santos, P.A.; Dias, J.; Guimarães, M.; Georgiadis, K.; Nyamsuren, E.; Bahreini, K.; Yumak, Z.; et al. Artificial intelligence moving serious gaming: Presenting reusable game AI components. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 351–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, N.; Bernstein, S. Museum 2.0. Acesso Emerg. J. 2006, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Garreau, D.; Luxburg, U. Explaining the explainer: A first theoretical analysis of LIME. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Online, 26–28 August 2020; PMLR. pp. 1287–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Risi, S.; Togelius, J. Neuroevolution in games: State of the art and open challenges. IEEE Trans. Comput. Intell. AI Games 2015, 9, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolbright, L. Ecofeminism and gaia theory in Horizon Zero Dawn. Trace, 24 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Video Games Europe. Games in Society. Available online: https://www.videogameseurope.eu (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Shaffer, D.W.; Gee, J.P. Before Every Child is Left Behind: How Epistemic Games can Solve the Coming Crisis in Education; Working Paper No. 2005–7; Wisconsin Center for Education Research: Madison, WI, USA, 2005; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Article 30—Participation in Cultural Life, Recreation, Leisure and Sport. Available online: https://social.desa.un.org/issues/disability/crpd/article-30-participation-in-cultural-life-recreation-leisure-and-sport (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Falk, J.H. The Value of Museums: Enhancing Societal Well-Being; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, G.; Donahue, C.; Pease, Z. Inclusive co-design within a three-dimensional game environment. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children, Manchester, UK, 21–24 June 2016; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Barra, V.; Corona, F. Enhancing the learning environment through Serious Games: A Case Study with PlayCanvas. J. Incl. Methodol. Technol. Learn. Teach. 2023, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ligthart, A. An Online Multiplayer Server Architecture for 3D Match-3-Games Using Nakama and Playcanvas. 2022. Available online: https://andersbouwer.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/online-multiplayer-server-architecture-for-3d-match-3-games-v1.0.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Piedade, P.; Neto, I.; Pires, A.C.; Prada, R.; Nicolau, H. Partiplay: A participatory game design kit for neurodiverse classrooms. In Proceedings of the 25th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, New York, NY, USA, 22–25 October 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Piedade, P.; Neto, I.; Pires, A.; Prada, R.; Nicolau, H. “That’s Our Game!”: Reflections on Co-designing a Robotic Game with Neurodiverse Children. In IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Treanor, M.; Zook, A.; Eladhari, M.P.; Togelius, J.; Smith, G.; Cook, M.; Thompson, T.; Magerko, B.; Levine, J.; Smith, A. AI-based game design patterns. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games 2015 (FDG 2015), Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 22–25 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti, R.; Monreale, A.; Ruggieri, S.; Turini, F.; Giannotti, F.; Pedreschi, D. A survey of methods for explaining black box models. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2018, 51, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravchenko, T.; Bogdanova, T.; Shevgunov, T. Ranking requirements using MoSCoW methodology in practice. In Computer Science On-Line Conference; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 188–199. [Google Scholar]

- Inclusive Design Research Centre. Available online: https://idrc.ocadu.ca/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Anderson, E.; Tushman, M. Museums in the Digital Age: Interactive Engagement Through Video Games. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2020, 35, 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, R. Museums in a Digital Age; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Donatiello, G.; Giosa, G.; Panzarino, P. The Role of Gamification in Cultural Heritage: A Case Study of European Museums. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2018, 10, e00089. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, A.; Sharma, S.; Wills, T. Textile Sustainability and Digital Innovation. J. Sustain. Des. 2022, 29, 112–126. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, N. The Participatory Museum; Museum 2.0.: Santa Cruz, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Westera, W.; Nadolski, R.; Hummel, H.G.; Wopereis, I. Serious games for higher education: A framework for reducing design complexity. J. Comput.-Assist. Learn. 2008, 24, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. The Museum Experience Revisited; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Roussou, M. Virtual heritage: From the research lab to the broad public. Virtual Real. 2002, 6, 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Champion, E. Critical Gaming: Interactive History and Virtual Heritage; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R.; Jones, S. Exploring Urban Heritage with Gamified AR: A Case Study of Cold War Sites. Digit. Herit. Int. Congr. 2020, 11, 134–146. [Google Scholar]

- Carrozzino, M.; Bergamasco, M. Beyond virtual museums: Experiencing immersive virtual reality in real museums. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beavis, C.; O’Mara, J.; Thompson, R. Digital games in the museum: Perspectives and priorities in videogame design. Learn. Media Technol. 2021, 46, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waydel-Bendyk, M. Evaluating potential of gamification to facilitate sustainable fashion consumption. In Proceedings of the HCI in Business, Government and Organizations: 7th International Conference, HCIBGO 2020, Held as Part of the 22nd HCI International Conference, HCII 2020, Copenhagen, Denmark, 19–24 July 2020; Proceedings 22. Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 205–215. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, R.; Oliveira, P.; Grilo, A.; Schwarz, A.; Cardon, G.; DeSmet, A.; Ferri, J.; Domenech, J.; Pomazanskyi, A. SmartLife smart clothing gamification to promote energy-related behaviours among adolescents. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC), Madeira Island, Portugal, 27–29 June 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1489–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesário, V.; Coelho, A.; Nisi, V. Enhancing museums’ experiences through games and stories for young audiences. In Proceedings of the Interactive Storytelling: 10th International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling, ICIDS 2017 Funchal, Madeira, Portugal, 14–17 November 2017; Proceedings 10. Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepe, J.; Koohnavard, S. Fashion and game design as hybrid practices: Approaches in education to creating fashion-related experiences in digital worlds. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2023, 16, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, P. Proceedings of the Designing for Play and Appropriation in Museum Experiences involving Tangible Interactions and Digital Technologies. Extended Abstracts of the 2020 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, Virtual, Canada, 2–4 November 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, P. Museums and the Post-Digital: Revisiting Challenges in the Digital Transformation of Museums. Heritage 2024, 7, 1784–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Accessibility Act. Available online: https://employment-social-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies-and-activities/social-protection-social-inclusion/persons-disabilities/union-equality-strategy-rights-persons-disabilities-2021-2030/european-accessibility-act_en (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Pasikowska-Schnass, M. Access to Cultural Life for People with Disabilities; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2019.

- Mosca, E.; Szigeti, F.; Tragianni, S.; Gallagher, D.; Groh, G. SHAP-based explanation methods: A review for NLP interpretability. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Gyeongju, Republic of Korea, 12–17 October 2022; pp. 4593–4603. [Google Scholar]

| # | KPI | Data Collection Method |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Percentage of end users reporting increased knowledge on arts and culture after project activities | Surveys |

| 2 | Percentage of cultural institutions reporting improved knowledge exchange and preservation practices | Interviews and feedback forms |

| 3 | Number of empowered professionals understanding culture- and fashion-related issues in game development | Surveys and interviews with professionals |

| 4 | Number of stakeholders claiming improved sensitivity and awareness of cultural content | Surveys and focus groups |

| 5 | Percentage of cultural institutions/museum administrators reporting new knowledge on creating cultural experiences and narratives | Surveys |

| 6 | Number of empowered professionals understanding tech-related issues in game development | Workshops and training evaluations |

| 7 | Number of cultural and textile/fashion organizations reporting enhanced knowledge on gaming and tech sectors | Surveys and interviews with organizations |

| 8 | Number of empowered professionals understanding more about tech-related issues related to technology development | Workshops and training evaluations |

| # | KPI | Data Collection Method |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | Number of organizations engaged and degree of engagement | Membership records and participation logs |

| 11 | Number of stakeholders and end users actively involved in network development initiatives | Surveys and participation records |

| 12 | Number of new partnerships formed | Partnership agreements |

| 13 | Number of initiatives and projects launched from new partnerships | Project reports and case studies |

| 14 | Number of cross-sectoral collaborations resulting in new cultural products or services | Surveys and interviews |

| 15 | Number of cross-sectoral participants actively engaging in co-design activities on the platform | Participation logs and activity records |

| 16 | Number of stakeholders reporting enhanced collaboration and understanding with other stakeholders from diverse sectors | Surveys and interviews with stakeholders |

| 17 | Number of co-design initiatives and projects initiated within the platform by cross-sectoral community members | Platform analytics and project reports |

| # | KPI | Data Collection Method |

|---|---|---|

| 18 | Percentage of end users reporting improved sense of belonging to the local community through heritage promotion | Surveys and community feedback |

| 19 | Percentage of community members reporting a stronger sense of identity and belonging to the gaming community | Surveys and community feedback |

| 20 | Number of end users actively participating in community events | Event participation logs |

| 21 | Number of community-driven initiatives supported by the project | Community project reports |

| 22 | Percentage increase in participation in cultural activities | Attendance records and surveys |

| 23 | Number of new end users visiting partner cultural institutions for the first time during or after the project | Visitor logs and feedback forms |

| 24 | Number of end users expressing a desire to participate in future cultural activities | Surveys and focus groups |

| # | KPI | Data Collection Method |

|---|---|---|

| 25 | Percentage of stakeholder organizations developing job descriptions for new roles inspired by the project’s outcomes | Analysis of job postings and organizational reports |

| 26 | Number of stakeholders planning to recruit or expand their workforce due to project-inspired initiatives | Surveys and focus groups with stakeholders |

| 27 | New funding/investments attracted by cultural institutions and fashion designers/textile companies for sustainable products | Financial records |

| 28 | Number of organizations reporting improved sustainability practices | Sustainability assessments |

| 29 | Number of new services launched and innovated | Innovation logs and project reports |

| 30 | Number of newly created or innovated products | Product logs, innovation records, and surveys |

| 31 | Number of good practices disseminated | Best practices documentation |

| # | KPI | Data Collection Method |

|---|---|---|

| 32 | Number of people reporting increased soft and life skills through project activities | Surveys and interviews |

| 33 | Number of people reporting improved educational performance through digital experiences | Academic records and surveys |

| 34 | Number of fashion/textile professionals reporting enhanced technical skills in gamification and transmedia storytelling due to the project’s activities | Surveys and interviews with fashion/textile professionals |

| 35 | Number of cultural industry professionals reporting enhanced technical skills in service innovation and experience management through gamified experiences | Surveys and interviews with cultural industry professionals |

| 36 | Number of game co-designers reporting enhanced technical skills in game design and technology development through the co-design platform | Surveys and interviews with game co-designers |

| 37 | Number of contents/technical knowledge consumed during the game design process | Content usage analytics |

| 38 | Number of end users claiming improved work efficiency thanks to the development of hard skills | Surveys and interviews |

| # | KPI | Data Collection Method |

|---|---|---|

| 39 | Number of end users reporting increased sensitivity to sustainability and social inclusion issues | Surveys and interviews |

| 40 | Number of stakeholders claiming to have reached a deeper understanding of social inclusivity and its value through gamification | Focus groups and surveys |

| 41 | Number of end users with vulnerable and/or disadvantaged conditions claiming greater inclusion and accessibility in cultural experiences delivered through video games and other project-promoted activities | Surveys and interviews with end users |

| # | KPI | Data Collection Method |

|---|---|---|

| 42 | Number of digitized cultural objects and assets | Digitalization logs and reports |

| 43 | Percentage of platform users reporting satisfaction with the accessibility features | Surveys and feedback forms |

| 44 | Number of collaborative projects initiated through the platform | Platform analytics and project logs |

| 45 | Percentage of users who understand and effectively use explainable AI components | Surveys and usage analytics |

| 46 | Number of users participating in workshops on on ethics and social inclusiveness | Workshop attendance logs |

| 47 | User engagement levels in co-design activities on the platform | Platform analytics (e.g., time spent, actions taken) |

| 48 | Percentage of gamified experiences co-designed on the platform that include elements of diversity and inclusion | Content analysis of co-designed projects |

| 49 | Number of users participating in workshops on heritage promotion and education through gamification | Workshop attendance logs |

| 50 | Percentage of platform users who feel their contributions to co-design activities are valued | Surveys and feedback forms |

| 51 | Number of new features implemented on the platform based on user feedback | Platform development logs and user feedback analysis |

| 52 | Percentage of users who report increased knowledge of ethics, diversity, and inclusion after using the platform | Surveys and interviews with users |

| 53 | Number of video game professionals reporting participation in legal awareness programs | Surveys and interviews with professionals |

| 54 | Number of video game companies and SMEs adopting legal compliance frameworks | Surveys and interviews with companies |

| 55 | Number of legal awareness materials (e.g., guidelines, toolkits) disseminated to video game professionals | Distribution logs and feedback forms |

| 56 | Number of video game professionals reporting participation in ethical-design culture programs | Surveys and interviews with professionals |

| 57 | Number of ethical-design guidelines and best practices disseminated to video game professionals | Distribution logs and feedback forms |

| 58 | Number of video game companies adopting ethical-design practices | Surveys and interviews with companies |

| KPI# | KPI | Target Value | Proxy Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Number of empowered professionals understanding culture- and fashion-related issues in game development | 100 professionals | Course on Digital Humanities |

| 6 | Number of empowered professionals understanding tech-related issues in game development | 60% of professionals (60 out of 100) | Course on Digital Humanities |

| 7 | Number of cultural and textile/fashion organizations reporting enhanced knowledge on gaming and tech sectors | 50 organizations | Course on Digital Humanities |

| 8 | Number of empowered professionals understanding more about tech-related issues related to technology development | 50% of professionals (250 out of 500) | Course on Digital Humanities |

| 11 | Number of new partnerships formed | 10 partnerships/year | Average value of new partnership deals |

| 12 | Number of initiatives and projects launched from new partnerships | 5 projects/year | Average costs of urban regeneration interventions and territorial animation projects |

| 13 | Number of cross-sectoral collaborations resulting in new cultural products or services | 12 collaborations/year | Tutoring cost for a incubation process |

| 19 | Number of end users actively participating in community events | 1000 end users | Value of event participation fees |

| 21 | Percentage increase in participation in cultural activities | 50% increase (250 additional participants out of 500) | Increased revenue from ticket sales |

| 25 | Number of stakeholders planning to recruit or expand their workforce due to project-inspired initiatives | 15 stakeholders | Annual unemployment benefit |

| 26 | New funding/investments attracted by cultural institutions and fashion designers/textile companies for sustainable products | 7 funding granted | Tuscany region financing to cultural organizations through public call |

| 28 | Number of new services launched and innovated | 12 services/year | Tutoring cost for a incubation process |

| 29 | Number of newly created or innovated products | 30 products | Tutoring cost for a incubation process |

| 31 | Number of people reporting increased soft and life skills through project activities | 50% of participants (250 out of 500) | Soft skills course—Forma Camere, Camera di Commercio di Roma |

| 33 | Number of fashion/textile professionals reporting enhanced technical skills in gamification and transmedia storytelling due to the project’s activities | 60 professionals | Cost of game design course |

| 34 | Number of cultural industry professionals reporting enhanced technical skills in service innovation and experience management through gamified experiences | 50 professionals | Cost of innovation management course |

| 35 | Number of game co-designers reporting enhanced technical skills in game design and technology development through the co-design platform | 80 co-designers | Cost of game design course |

| 41 | Number of digitized cultural objects and assets | 350 digitized objects | Cost savings from digital preservation |

| 43 | Number of collaborative projects initiated through the platform | 20 projects/year | Cost of digitalization voucher |

| 45 | Number of users participating in workshops on on ethics and social inclusiveness | 200 users/year | Course on Digital Humanities |

| 50 | Number of new features implemented on the platform based on user feedback | 10 features/year | Development cost savings per feature |

| 52 | Number of video game professionals reporting participation in legal awareness programs | 150 professionals/year | Average cost of legal awareness training program per professional |

| 53 | Number of video game companies and SMEs adopting legal compliance frameworks | 40 companies | Cost of implementing a legal compliance framework per company |

| 54 | Number of legal awareness materials (e.g., guidelines, toolkits) disseminated to video game professionals | 500 materials/year | Cost of producing and distributing legal awareness materials per unit |

| 55 | Number of video game professionals reporting participation in ethical-design culture programs | 200 professionals/year | Average cost of ethical-design training program per professional |

| 56 | Number of ethical-design guidelines and best practices disseminated to video game professionals | 300 materials/year | Cost of producing and distributing ethical-design materials per unit |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kosti, M.V.; Diplaris, S.; Georgakopoulou, N.; Runnel, P.; Marini, C.; Rovatsos, N.; Barakli, A.; de Lera, E.; Vrochidis, S.; Kompatsiaris, I. i-Game: Redefining Cultural Heritage Through Inclusive Game Design and Advanced Technologies. Electronics 2025, 14, 1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14061141

Kosti MV, Diplaris S, Georgakopoulou N, Runnel P, Marini C, Rovatsos N, Barakli A, de Lera E, Vrochidis S, Kompatsiaris I. i-Game: Redefining Cultural Heritage Through Inclusive Game Design and Advanced Technologies. Electronics. 2025; 14(6):1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14061141

Chicago/Turabian StyleKosti, Makrina Viola, Sotiris Diplaris, Nefeli Georgakopoulou, Pille Runnel, Camilla Marini, Nikos Rovatsos, Angeliki Barakli, Eva de Lera, Stefanos Vrochidis, and Ioannis Kompatsiaris. 2025. "i-Game: Redefining Cultural Heritage Through Inclusive Game Design and Advanced Technologies" Electronics 14, no. 6: 1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14061141

APA StyleKosti, M. V., Diplaris, S., Georgakopoulou, N., Runnel, P., Marini, C., Rovatsos, N., Barakli, A., de Lera, E., Vrochidis, S., & Kompatsiaris, I. (2025). i-Game: Redefining Cultural Heritage Through Inclusive Game Design and Advanced Technologies. Electronics, 14(6), 1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14061141