1. Introduction

The physical design of CMOS-integrated circuits is a fundamental and challenging step in modern VLSI design. This process involves translating a logical circuit description into an optimized geometric layout that meets critical metrics such as chip area, wirelength, timing closure, routing congestion, and power consumption. As modern integrated circuits become increasingly complex and contain billions of transistors, traditional methods for physical design become less effective. Deterministic placement and routing algorithms—including sequential placement and simulated annealing—often struggle with scalability, multi-objective optimization, and global convergence.

Nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithms, such as Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) [

1], provide a promising alternative for solving such complex combinatorial optimization problems. ACO is inspired by the foraging behavior of ants, which deposit pheromone trails to collectively communicate and identify the shortest paths. In computational terms, ACO uses simulated ants constructing candidate solutions by probabilistically choosing components based on pheromone intensity and heuristic information. Over time, the algorithm reinforces successful solution pathways through pheromone updates, thereby balancing exploration of the solution space with exploitation of past findings.

This research applies ACO to the optimization of CMOS physical design, focusing on placement and layout optimization stages. The algorithm is tailored to optimize essential physical design metrics such as layout area and aspect ratio. Its performance is rigorously evaluated on a benchmark of ten representative logic blocks (Adder, Multiplier, Shifter, MUX, Register, ALU, Decoder, Control, Cache, and Buffer), comparing against traditional baseline approaches and heuristic methods.

The major contributions of this paper include the following:

Demonstrating that ACO can reduce layout area by an average of 20.09% (maximum 27.27%) and optimize aspect ratios compared to traditional placement approaches across diverse parameters.

Developing a flexible and modular ACO framework that addresses key physical design metrics with thorough hyperparameter sensitivity analysis.

Providing a configurable automation tool requiring user-supplied configuration files and command-line parameters, which automates optimization, benchmarking, and reporting workflows for reproducible experiments.

Demonstrating robust scalability and convergence across ten functional blocks, establishing ACO as a practical solution for CMOS layout optimization.

This work establishes that bio-inspired computing methods offer practical advantages in physical design automation and represent a promising direction for managing the increasing complexities of modern VLSI circuits. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2, containing a review of the literature on VLSI placement and metaheuristic approaches.

Section 4 details the ACO algorithm applied to the CMOS physical design and discusses the implementation details.

Section 5 presents comprehensive results demonstrating the algorithm’s performance and the capabilities of the automation tool. Finally,

Section 6 and

Section 7 present the future research and summarize the conclusions.

2. Background

The physical design of CMOS-integrated circuits is a critical stage in modern VLSI design, involving the transformation of a logical circuit description into an optimized geometric layout. Among the key steps in this process, chip placement is a fundamental problem that involves arranging logic blocks on the chip to minimize total area and routing complexity [

2]. Each logic block often has several possible width and height combinations, representing alternative aspect ratios that can be selected during floorplanning [

3,

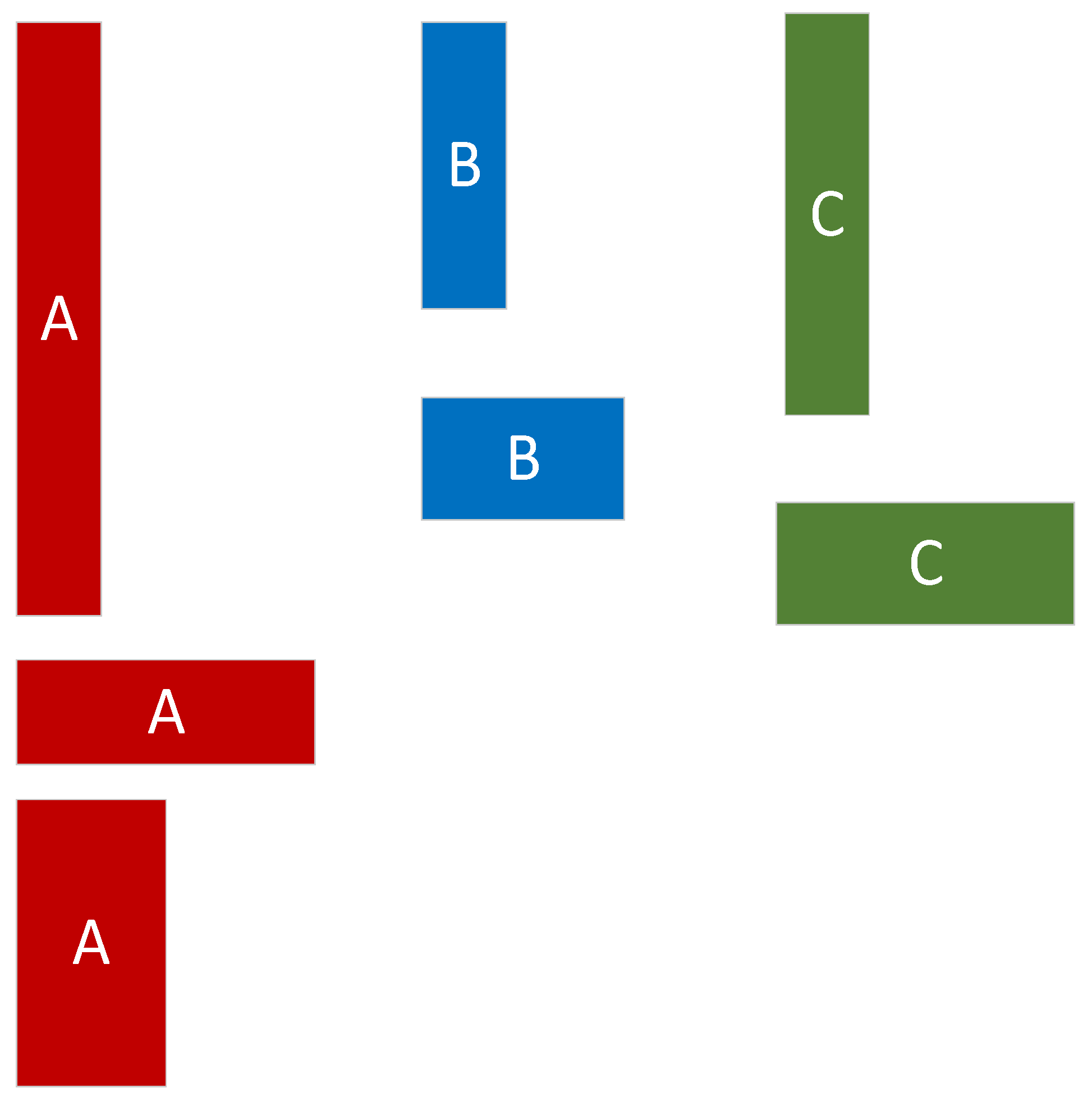

4]. As shown in

Figure 1, the initial configuration of the three example blocks: A, B, and C includes the following:

Block A: w = 1, h = 4 or w = 4, h = 1 or w = 2, h = 2.

Block B: w = 1, h = 2 or w = 2, h = 1.

Block C: w = 1, h = 3 or w = 3, h = 1.

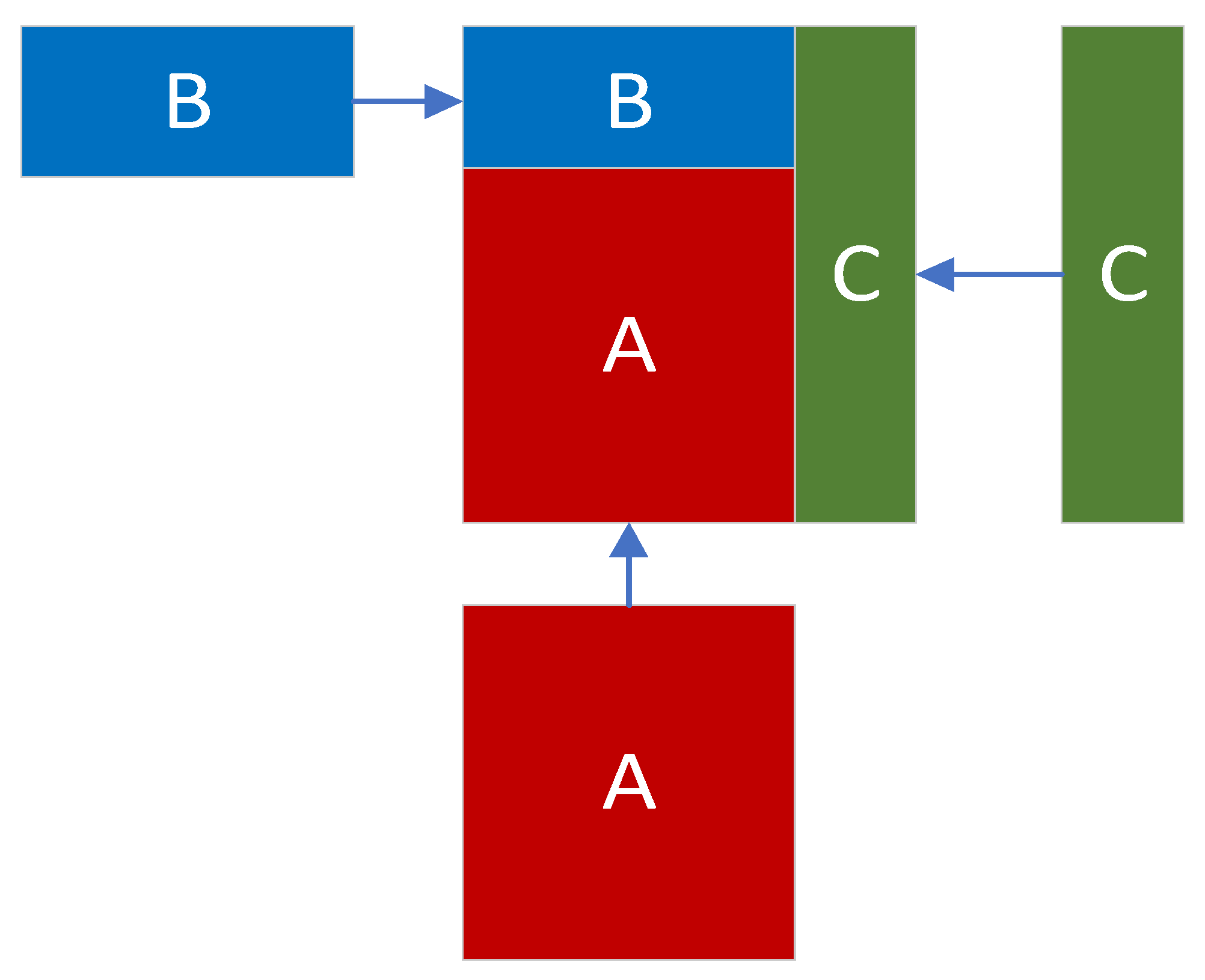

A traditional placement might select suboptimal aspect ratios (e.g., a long and thin shape for Block A), resulting in a scattered or elongated floorplan. This strategy typically leads to a larger total chip area and inefficient block adjacency, making signal routing more complex. On the other hand, optimized placement, as illustrated in

Figure 2, chooses the most compact and compatible aspect ratios for each block to achieve tight packing and minimal area. In this example, the optimized choices are as follows:

Block A: w = 2, h = 2.

Block B: w = 2, h = 1.

Block C: w = 1, h = 3.

These selections produce a global bounding box of just nine square units, effectively reducing wasted space and improving overall design efficiency. The process of aspect ratio selection and strategic positioning underscores the importance of optimization algorithms in VLSI layout planning.

A fundamental challenge in placement arises from the combinatorial explosion of possible configurations. Each block can assume multiple width–height combinations, leading to an exponentially growing solution space as the number of blocks increases. This makes VLSI placement an NP-hard problem, where exact optimization becomes computationally infeasible for large-scale designs. Consequently, designers rely on heuristic and metaheuristic approaches to approximate near-optimal solutions. Traditional methods such as simulated annealing and greedy heuristics [

5,

6] provide some improvement, but can become trapped in suboptimal solutions. In this work, the ACO algorithm is used as a bio-inspired approach for placement optimization. By emulating the collective intelligence of ants, ACO can dynamically explore various placement solutions and efficiently converge to near-optimal floorplans.

3. Literature Review

The optimization of VLSI floorplanning and placement has been extensively explored, with metaheuristic and hybrid approaches addressing challenges such as area minimization, aspect ratio control, wirelength reduction, and multi-objective trade-offs. This section reviews recent advances, focusing on Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), Genetic Algorithms (GA), Simulated Annealing (SA), hybrid metaheuristics, and deep learning-based methods, as reported in the literature.

3.1. Metaheuristic and Hybrid Approaches

ACO has emerged as a robust metaheuristic for VLSI floorplanning, offering distributed search and adaptability to multi-objective criteria. In [

7], an ACO-based algorithm tailored for floorplanning with clustering constraints is presented, introducing a dynamic junction list-encoding and dual pheromone trails. Experiments on MCNC benchmarks demonstrate that the proposed method achieves average deadspace reductions ranging from 0.77% to 9.21% across various problem instances, with the best area results for the “apte” circuit at 46.92 mm

2 and deadspace of 0.77%. The algorithm also shows improved performance over simulated annealing (SA) in both single-cluster and multi-cluster scenarios, with area and deadspace metrics consistently outperforming the baseline.

A further extension of ACO is explored in [

8], where a hybridized Firefly and Ant Colony System (HMAC-FO) is proposed. This hybrid approach leverages the strengths of both algorithms to optimize area, wirelength, and thermal characteristics. On MCNC benchmarks, the HMAC-FO method achieves an average area reduction of 3.48%, wirelength reduction of 0.64%, and temperature reduction of 3.33% compared to the best existing methodologies. For example, on the “apte” circuit, the area is reduced from 48.03 mm

2 (LOA baseline) to 46.61 mm

2 (HMAC-FO).

The Variable-Order Ant System (VOAS), described in [

9], combines ACO with a corner list representation to further enhance area and wirelength optimization. VOAS achieves area values of 46.92 mm

2 for “apte” (deadspace 1.0%), 19.80 mm

2 for “xerox” (1.0%), and 36.24 mm

2 for “ami49” (1.0%), with normalized wirelengths and runtime metrics that compare favorably to other state-of-the-art algorithms. The approach demonstrates robust performance across a range of MCNC and GSRC benchmarks, with area and wirelength improvements observed in over 75% of test cases.

Genetic Algorithms (GA) [

10], and their hybrids have also been widely adopted for VLSI floorplanning. In [

11], a GA-based approach is presented, utilizing a B*-tree representation and best-fit heuristic for initial population generation. The method achieves area reductions of up to 12.3% (unused area) for the “ami33” benchmark and 6.6% for “ami49” as the number of iterations increases. The best reported area results are 1.17 mm

2 for “ami33” and 35.45 mm

2 for “ami49”, outperforming simulated annealing (SA) and differential evolution (DE) baselines.

A hybrid evolutionary algorithm combining GA and SA is detailed in [

12]. This approach applies GA for global search and SA for local refinement, achieving area reductions and wirelength improvements across standard benchmarks. For instance, the “xerox” circuit achieves a wirelength of 32.06 (hybrid) compared to 33.56 (GA), and the “ami49” circuit achieves a wirelength of 58.33 (hybrid) versus 63.55 (GA). The hybrid method also demonstrates reduced CPU time, with the “ami33” circuit requiring only 24 s (hybrid) compared to 30 s (GA).

Simulated Annealing (SA) remains a foundational technique for VLSI floorplanning. In [

13], an SA-based algorithm with block reshaping and compaction is presented, reporting area values of 46.92 mm

2 for “apte”, 19.96 mm

2 for “xerox”, and 36.05 mm

2 for “ami49”. The deadspace for these circuits is reported as 0.77%, 3.06%, and 1.69%, respectively. The method achieves competitive results compared to TCG, DPSO, and other recent algorithms, with area and aspect ratio improvements observed across multiple MCNC benchmarks.

3.2. Multi-Objective and Thermal-Aware Optimization

Multi-objective optimization, including thermal-aware floorplanning, has gained prominence in recent years. In [

14], an Enhanced Memetic Algorithm (EMA) using a Skewed B*-tree (SKB-tree) representation is introduced, optimizing area, wirelength, and temperature. On MCNC benchmarks, the EMA achieves area values of 47.3 mm

2 for “apte”, 1.18 mm

2 for “ami33”, and 36.4 mm

2 for “ami49”, with deadspace percentages of 1.56%, 2.5%, and 2.6%, respectively. The algorithm also demonstrates improved runtime, with the “ami33” circuit converging in 1.6 s, significantly faster than the VOAS comparator.

3.3. Deep Learning and Reinforcement Learning Approaches

Recent advances in deep learning have introduced reinforcement learning (RL) for VLSI floorplanning. In [

15], a deep RL algorithm based on sequence pairs is proposed, optimizing area and wirelength. On MCNC benchmarks, the method achieves area values of 46.94 mm

2 for “apte”, 20.40 mm

2 for “xerox”, and 9.20 mm

2 for “hp”, with deadspace percentages of 0.81%, 5.15%, and 4.02%, respectively. The RL approach outperforms simulated annealing (SA) and deep Q-learning baselines, with average area improvements of 2.7% and wirelength improvements of 9.1% over SA.

3.4. Comprehensive Reviews and Comparative Studies

A broad review of VLSI floorplanning optimization is provided in [

16], summarizing the performance of various metaheuristics, including GA, SA, PSO, and ACO. The review highlights that ACO with corner list representation achieves the best area optimization on MCNC benchmarks, with area values of 46.9 mm

2 for “apte”, 19.8 mm

2 for “xerox”, and 1.20 mm

2 for “ami33”. The review also notes that PSO and hybrid methods offer competitive performance, particularly in balancing area and wirelength objectives.

3.5. 3D Floorplanning and Advanced Representations

The extension of floorplanning to 3D VLSI is explored in [

17], where a simulated annealing-based algorithm is proposed for 3D slicing floorplans. The method achieves packing results on average 3% better than the sequence-triple-based algorithm, with runtime improvements of up to 17× for problems containing 100 blocks. The approach also demonstrates the ability to handle placement constraints and thermal distribution, with area and deadspace metrics reported for large-scale benchmarks.

While the reviewed literature demonstrates significant progress in metaheuristic algorithms and hybrid approaches for VLSI floorplanning, none of the prior studies propose or provide an automation tool specifically designed for ACO with configurable hyper-parameters. In contrast, our work introduces a novel automation framework that enables users to flexibly adjust parameters such as the number of ants, iteration count, pheromone evaporation rate, and the relative influence of heuristic and pheromone information (i.e., and ). This tool is engineered to facilitate reproducible experimentation and rapid benchmarking, empowering both practitioners and researchers to systematically investigate the impact of algorithmic settings on floorplanning outcomes. The availability of such a configurable and user-friendly automation tool distinguishes our contribution from existing works and addresses a notable gap in the current literature.

4. Methodology and Implementation

4.1. Overview of ACO for VLSI Placement

The ACO algorithm used in this research models the natural foraging behavior of ants for application in CMOS physical design optimization [

18,

19]. The problem of layout placement and global routing is framed as a combinatorial optimization task where ants probabilistically construct candidate layout solutions across a search graph.

ACO is well-suited for NP-hard placement problems because it employs a distributed search mechanism that balances exploration and exploitation. Unlike deterministic heuristics, which often converge prematurely, ACO uses probabilistic solution construction and pheromone reinforcement to escape local optima. The algorithm’s complexity is approximately , where m is the number of ants and n is the number of blocks, making it scalable for moderate design sizes while maintaining solution diversity.

4.2. Algorithm Steps

The key steps in the algorithm are detailed below.

4.2.1. Initialization

The physical layout is initialized by defining a set of functional blocks with configurable dimensions and an initial placement state. Pheromone levels are initialized uniformly across all possible placement pairs or decision points, representing equal initial preference. A population of artificial ants is deployed randomly within the layout space, each tasked with independently constructing candidate solutions. Parameters such as pheromone importance (), heuristic importance (), pheromone evaporation rate, and the number of ants are configured at this stage.

4.2.2. Solution Construction (Ant Exploration)

Each ant incrementally builds a candidate placement solution by selecting the placement of each block stepwise. The selection is probabilistic, governed by a formula that combines pheromone intensity (representing the learned desirability of previous successful layouts) and heuristic information such as block size, or potential wirelength impact. At each step, ants evaluate feasible next placements considering these components to balance the exploration of new placements and exploitation of good previous solutions. This process continues until all blocks are assigned positions, resulting in a complete layout solution per ant.

4.2.3. Evaluation of Solutions

Once a candidate layout is constructed by an ant, it is evaluated using key physical design metrics. This includes calculating the total area occupied by the blocks, assessing the aspect ratio of the bounding box (aiming for compactness), and estimating routing wirelength. These metrics help quantify solution quality, enabling ranking and comparison across ants. Typically, a combined cost function weighted by these metrics guides the optimization.

4.2.4. Pheromone Update

Following the evaluation, pheromone levels are updated to reinforce the components of high-quality solutions. The algorithm increases pheromone levels on placement decisions contributing to better layouts (e.g., those that minimize area) based on defined update rules. Pheromone evaporation also occurs simultaneously across all paths to prevent early stagnation and to maintain diversity in the solution search space. This dynamic ensures a balance between intensifying the search around promising solutions and exploring new potential layouts [

19,

20].

4.2.5. Termination Criteria

The iterative search continues for a predefined maximum number of iterations or until convergence criteria are met; such as minimal improvement in best solution quality over several iterations. Upon termination, the best layout configuration found is selected as the optimized floorplan.

This iterative, decentralized search enables the algorithm to escape local optima and explore diverse layouts. Parameter tuning controls the balance between exploitation of known good paths and exploration of novel configurations.

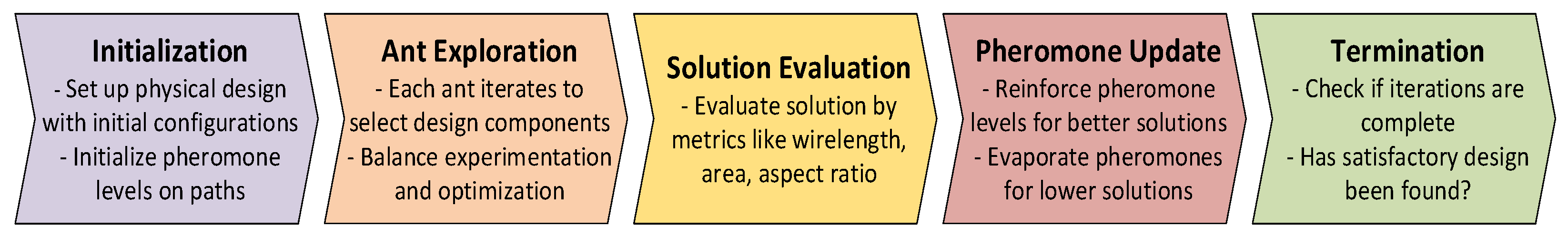

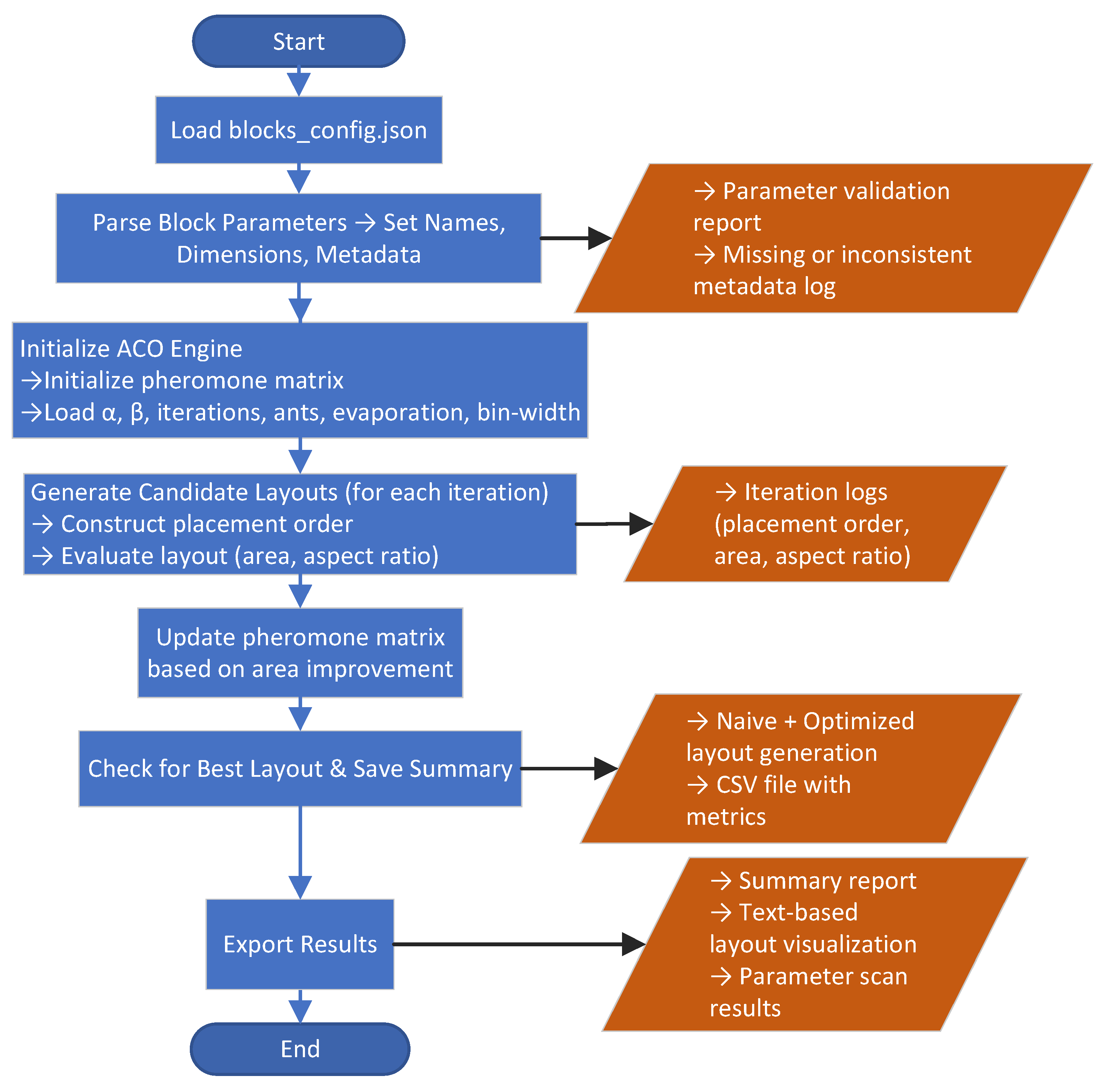

Figure 3 shows a flowchart summarizing these steps.

An open-source implementation of the ACO algorithm, developed in Python, accompanies this work. This provides a reproducible framework for benchmarking and further research on physical design automation using metaheuristics.

4.3. Implementation

The implementation of the proposed ACO algorithm for VLSI placement is detailed in this section. It covers the specific experimental setup, including the selection and dimensional specifications of the circuit logic modules. This is followed by an expanded description of the algorithmic steps tailored to this application.

4.3.1. Parameter Tuning and Experimental Setup

A comprehensive parameter study was conducted to evaluate the sensitivity of the ACO algorithm to its hyperparameters. The experiments varied key parameters across predefined ranges: number of ants (20, 40, 80), iterations (100, 200, 300), evaporation rate ( = 0.1, 0.3, 0.5), and alpha–beta pairs = (1.0, 1.0), (1.0, 2.0), (1.5, 1.5), and (2.0, 1.0). Bin widths were tested from 40 to 80 units. Each configuration was evaluated based on layout area reduction and aspect ratio.

Based on these experiments, a baseline configuration of

,

,

, 20 ants, and 30 iterations was selected for subsequent evaluations to balance solution quality and runtime efficiency. This choice aligns with practical runtime constraints while maintaining competitive optimization performance. Sensitivity analysis results are presented in

Section 5 to validate robustness.

Next,

Table 1 summarizes the set of functional blocks used in this study, along with their dimensions and computed areas. These blocks represent typical components in VLSI layouts and serve as the benchmark for evaluating the proposed optimization algorithm.

All experiments were performed on a desktop computer equipped with an Intel Core i7 processor and 16 GB of RAM. The algorithm was implemented in Python 3.11 using standard scientific computing libraries. In addition, Matlab software R2024 was used to generate experimental plots.

4.3.2. Mathematical Formulation

The ACO algorithm used for VLSI placement is expanded in this subsection. The algorithm iteratively constructs and improves layout solutions through probabilistic exploration guided by pheromone trails and heuristic information. The following formulations govern solution construction and evaluation.

Initialization

The algorithm begins by defining a set of functional blocks with configurable dimensions and initializing pheromone levels uniformly across all possible placement pairs. A population of artificial ants is deployed randomly within the layout space. Parameters such as pheromone influence (), heuristic influence (), evaporation rate (), colony size, and iteration count are set at this stage.

4.3.3. Solution Construction

Each ant incrementally builds a candidate placement solution through the stepwise selection of position of each block. The selection is probabilistic, governed by:

where

denotes the pheromone level and

represents the heuristic desirability (e.g., inverse block area or wirelength impact). Specifically,

i represents the last placed block (or the initial state), and

j denotes the candidate block being considered for the next position in the sequence.

4.3.4. Evaluation of Solutions

Each candidate solution

is evaluated using a cost function that combines layout metrics:

where

A is total area and

R is the aspect ratio,

and

are weighting coefficients.

4.3.5. Pheromone Update

After all ants complete their solutions, pheromone evaporation weakens all trails:

Pheromone levels are then reinforced based on solution quality:

with

where

Q controls deposit magnitude.

Termination Criteria

The algorithm repeats until either the maximum number of iterations () is reached or improvements plateau. The best placement solution with minimum cost is returned.

4.4. Layout Visualization

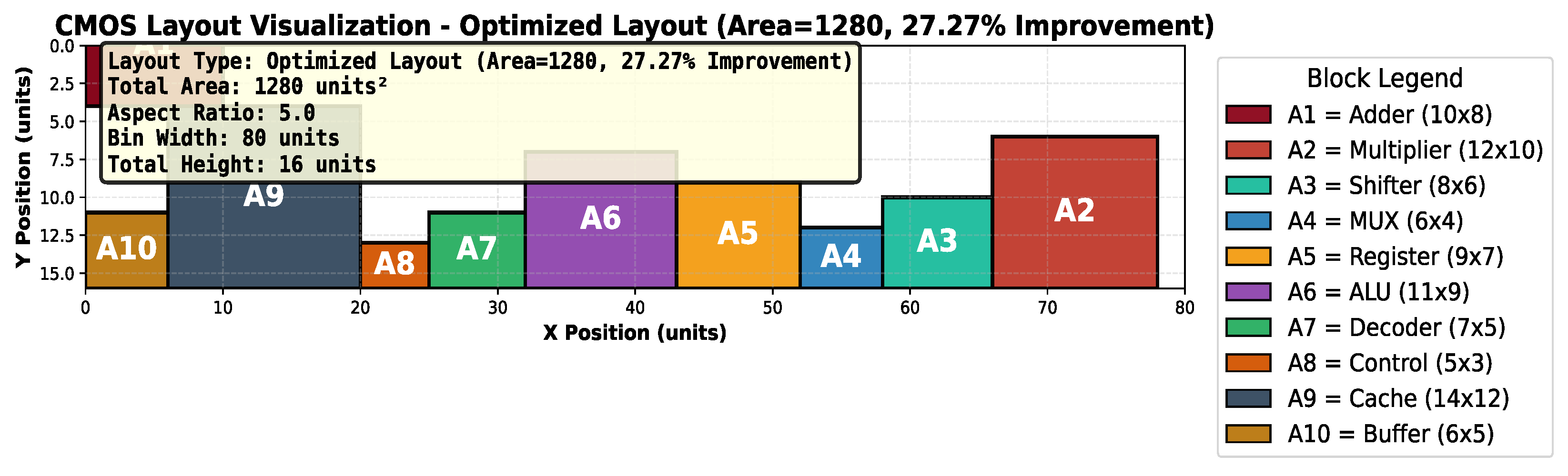

This sub-section illustrates the impact of optimization by comparing the traditional and optimized layouts. The optimized configuration in this case achieves a 27.27% reduction in area relative to the baseline.

4.4.1. Traditional Layout

The traditional layout arranges blocks sequentially within a fixed bin width of 80 units, resulting in significant unused space. This configuration yields a total area of

and an aspect ratio of 3.64, as shown in

Figure 4.

4.4.2. Optimized Layout

The optimized layout rearranges block placement to minimize height while maintaining the same bin width. This approach reduces the total area to

, achieving a 27.27% improvement over the traditional case, though the aspect ratio increased to 5.00 (

Figure 5).

4.5. Automation Tool for ACO Optimization

To streamline experimentation and ensure reproducibility, a modular automation tool was developed in Python (

Figure 6). This tool automates the entire workflow of ACO-based optimization, from input parsing to result reporting, eliminating manual intervention and reducing the risk of human error.

Key Features:

Configurable Inputs: Users provide block specifications and algorithm parameters through JSON configuration files and command-line arguments, enabling rapid parameter tuning and batch execution.

Automated Workflow: The tool initializes pheromone matrices, executes iterative optimization, and evaluates layouts using predefined cost functions. This supports large-scale parameter sweeps for sensitivity analyses without requiring manual setup.

Comprehensive Outputs: Results are exported as CSV logs, summary tables, and visualizations (e.g., traditional vs. optimized layouts, performance metrics). The workflow also generates reports for seamless integration.

Reproducibility and Scalability: By automating input parsing, execution, and reporting, the tool ensures consistent results across runs and facilitates benchmarking against other metaheuristics. This design supports scalability for experiments involving hundreds of configurations and thousands of iterations.

Why It Matters?: In physical design research, reproducibility is critical for validating algorithmic improvements and comparing methods. Manual workflows often introduce inconsistencies and limit scalability. The proposed automation tool addresses these challenges by providing a standardized, repeatable process that can be easily extended to new benchmarks, hybrid algorithms, and multi-objective formulations.

Figure 6 illustrates the workflow, highlighting stages such as configuration parsing, ACO engine initialization, solution construction, pheromone updates, and exporting results.

5. Results and Discussion

The proposed ACO algorithm was evaluated on a CMOS physical design task involving ten functional blocks: Adder, Multiplier, Shifter, MUX, Register, ALU, Decoder, Control, Cache, and Buffer. The primary objective was to minimize total layout area while maintaining practical aspect ratios. A comprehensive parameter study was conducted across 540 independent runs spanning 108 unique configurations, varying colony size, iteration count, evaporation rate, and – pairs.

5.1. Quantitative Performance

Table 2 summarizes the overall statistics obtained from 540 independent runs across 108 parameter configurations. The ACO algorithm achieved an average area reduction of 20.09% with a standard deviation of 4.46%, indicating stable convergence behavior across diverse settings. Improvements ranged from 13.64% to 27.27%, demonstrating the algorithm’s ability to deliver significant compaction even under varying conditions.

Aspect ratio changes averaged +0.70, meaning layouts became less square but remained within the practical bounds for routing and manufacturability. While this trade-off reflects the algorithm’s prioritization of area minimization, the magnitude of change is moderate and does not compromise design feasibility.

The low variability in results suggests robustness to parameter tuning, which is critical for large-scale design automation. Extreme cases and their corresponding hyperparameter settings are detailed in

Table 3, providing actionable insights for practitioners. These findings confirm that ACO consistently outperforms traditional heuristic approaches, offering measurable gains in layout efficiency without excessive computational overhead.

5.2. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

Figure 7 aggregates the impact of key parameters like colony size, iteration count, and evaporation rate on area reduction. The boxplots reveal several important trends:

Colony Size: Increasing the number of ants from 20 to 80 improves median area reduction only marginally (approximately 19% to 23%), while variability remains low. This indicates diminishing returns beyond 20 ants, consistent with metaheuristic principles where additional agents increase computational cost without proportional gains.

Iteration Count: Higher iteration counts lead to modest improvements in median area reduction (from 19% at 100 iterations to about 23% at 300 iterations). Most gains occur early, suggesting that convergence is achieved efficiently and excessive iterations may not be necessary for practical workflows.

Evaporation Rate: Variations in evaporation rate (0.1 to 0.5) have minimal impact on optimization quality, with median area reduction remaining stable around 20%. This robustness simplifies parameter tuning and confirms that ACO maintains consistent performance across pheromone decay settings.

These observations underscore the algorithm’s stability and scalability. Designers can prioritize moderate colony sizes and iteration counts to balance runtime and solution quality, while evaporation rate can be tuned flexibly without risk of performance degradation.

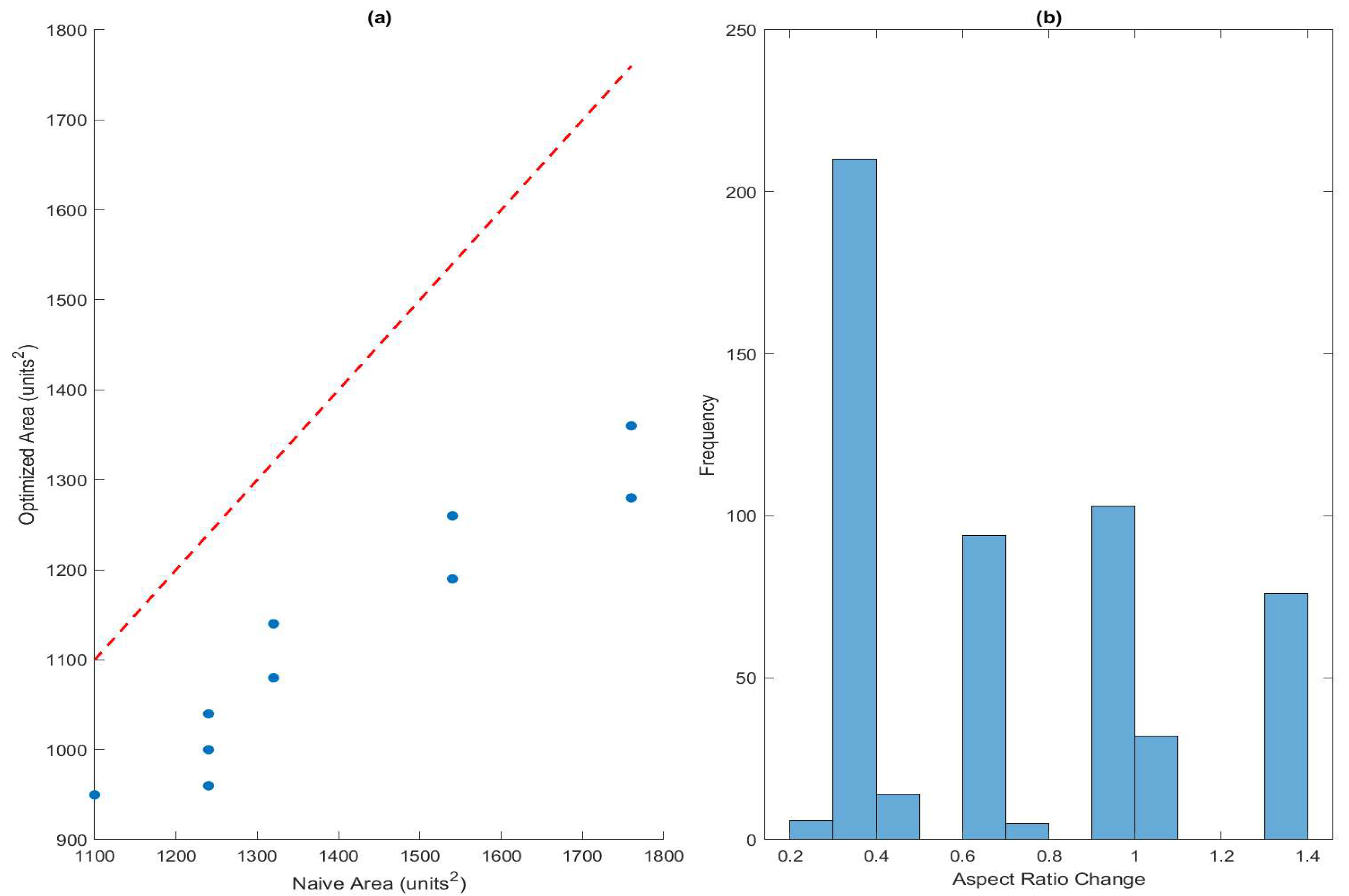

5.3. Performance Distribution and Trade-Offs

Figure 8 illustrates the overall optimization behavior of the ACO. The scatter plot confirms consistent area reduction across all runs, with most points lying below the diagonal, validating ACO’s effectiveness for layout compaction. The histogram highlights a trade-off; while area reduction is substantial, aspect ratio changes indicate layouts often become less square. This reflects the algorithm’s prioritization of area minimization over shape regularity, which is a common challenge in physical design optimization.

Such trade-offs are typical when conflicting objectives exist. The flexibility of the ACO framework allows users to adjust cost-function weights to prioritize compactness or regularity as needed, motivating future research in multi-objective optimization to achieve balanced designs.

Beyond these trade-offs, the distribution of solutions across multiple runs demonstrates that ACO avoids premature convergence and explores diverse solution spaces, overcoming the limitations of deterministic algorithms. Parameter tuning such as pheromone evaporation rate, heuristic influence, and colony size proved crucial for balancing convergence speed and solution diversity.

Although manually stacked layouts can approximate efficiency in select cases, ACO consistently delivers superior compactness and aspect ratios as design complexity increases. In all tests, ACO matched or exceeded heuristic baselines without requiring explicit domain knowledge. Combined with the automation tool, this approach ensures reproducibility and scalability for large benchmarks. Overall, ACO effectively balances exploration and exploitation, converging toward compact floorplans that reduce wasted chip area without significant computational overhead.

6. Future Work and Industrial Applications

The proposed ACO framework was implemented along with an automation tool that enables reproducible and scalable experimentation. While test results demonstrate promising improvements in layout area and aspect ratio optimization, several gaps need to be addressed to ensure its broader applicability. Future research will therefore focus on three key directions: overcoming current limitations, introducing algorithmic enhancements, and enabling industrial integration. These are outlined below.

6.1. Addressing Current Limitations

The current ACO implementation focuses primarily on area minimization and aspect ratio control, without explicit consideration of critical metrics like wirelength, routing congestion, power consumption, etc. Additionally, evaluation on a limited set of functional blocks provides proof-of-concept validation but does not demonstrate scalability to industrial designs with hundreds or thousands of modules.

6.2. Algorithmic Enhancements

Future research will leverage the automation tool to introduce several algorithmic improvements aimed at enhancing both the quality and scalability of solutions. A key area is multi-objective optimization: incorporating wirelength estimation, congestion analysis, and thermal-aware placement through weighted cost functions to better reflect real-world design constraints. Scalability will be addressed by benchmarking against larger and more complex public suites such as MCNC, GSRC, and ISPD, as well as by enabling parallel ACO implementations for efficiency.

Hybridization strategies will also play a central role: combining ACO with advanced techniques such as reinforcement learning or graph neural networks to accelerate convergence and improve optimization performance. Finally, adaptive parameter tuning will be explored: enabling self-tuning mechanisms for critical hyperparameters (, , , and population size) based on design characteristics and runtime feedback, thereby dynamically balancing exploration and exploitation throughout the search process.

6.3. Industrial Applications

The modular automation tool positions ACO for practical integration into electronic design automation (EDA) workflows, enabling several high-impact applications. One promising use case is as a rapid floorplanning accelerator, generating high-quality initial placements that can feed into commercial tools. In system-on-chip (SoC) design, the framework can optimize macro-placement in heterogeneous integration scenarios where block sizes vary widely and aspect ratio control is critical.

Beyond initial placement, the tool supports systematic parameter exploration during architecture design, enabling teams to evaluate trade-offs primarily across area and aspect ratio objectives. Dynamic floorplanning for reconfigurable computing platforms, such as FPGA/ASIC hybrids requiring runtime layout adaptation, represents another compelling application.

Finally, the open-source implementation, which includes a JSON-configurable interface and comprehensive logging, supports technology transfer and customization for specific foundry processes. This flexibility ensures adaptability to a wide range of industrial requirements.

7. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) is an effective and scalable approach for CMOS physical design, particularly in placement and global routing. By mimicking the foraging behavior of ants, ACO systematically explores diverse layout configurations and reinforces high-quality solutions through pheromone-based feedback. Across 540 runs and 108 parameter configurations, the algorithm achieved an average 20.09% reduction in layout area, with improvements of up to 27.27%, and maintained practical aspect ratios. These gains translate into better chip utilization and manufacturability compared to traditional heuristic approaches.

Beyond quantitative improvements, ACO’s modular and probabilistic nature supports multi-objective optimization and seamless integration with other metaheuristics. Its ability to balance exploration and exploitation helps avoid local optima and ensures robust convergence, which is a critical requirement for modern VLSI and SoC floorplanning. The automation tool developed in this work further enhances reproducibility and scalability, enabling systematic benchmarking and parameter sensitivity analysis.

Future research will focus on extending ACO to larger benchmarks, incorporating additional objectives such as wirelength, congestion, and timing, and exploring hybrid algorithms that combine ACO with local search or reinforcement learning. Overall, this work underscores the potential of bio-inspired metaheuristics to advance physical design automation in increasingly complex integrated circuits.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.P.; methodology, A.A.P. and J.T.; software, A.A.P.; validation, S.A. and A.A.P.; formal analysis, J.T.; investigation, J.T.; resources, A.A.P.; data curation, J.T.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.P.; writing—review and editing, S.A.; visualization, A.A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The complete Python implementation, configuration files, and raw run logs used in this study are available at [repository to be added upon acceptance]. This open-source release enables replication of all reported results and facilitates comparative evaluation with other metaheuristic approaches for VLSI physical-design optimization.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Caylen Hunt for his assistance with the preliminary data collection in this study. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dorigo, M.; Birattari, M.; Stutzle, T. Ant colony optimization. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 2006, 1, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahng, A.B.; Lienig, J.; Markov, I.L.; Hu, J. VLSI Physical Design: From Graph Partitioning to Timing Closure; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; ISBN 9789048195909. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, D.F.; Liu, C.L. A New Algorithm for Floorplan Design. In Proceedings of the 23rd ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 29 June–2 July 1986; pp. 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, N.; Chu, C.C.-N. FastPlace: Efficient Analytical Placement Using Cell Shifting, Iterative Local Refinement and a Hybrid Net Model. In Proceedings of the 2004 International Symposium on Physical Design, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 18–21 April 2004; pp. 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Yang, R.; Chen, M.; Jia, X.; Li, X.; Du, S. An Efficient Simulated Annealing Based VLSI Floorplanning Algorithm for Slicing Structure. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Computer Science and Service System, Nanjing, China, 11–13 August 2012; pp. 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Chandel, R.; Chandel, A.; Sandhu, P.S. Simulated annealing based delay centric VLSI circuit partitioning. In Proceedings of the 2010 3rd International Conference on Computer Science and Information Technology, Wuxi, China, 4–6 June 2010; Volume 1, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.-W. Ant Colony Optimization for VLSI Floorplanning with Clustering Constraints. J. Chin. Inst. Ind. Eng. 2009, 26, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, B.; Venkatesan, R.; Aljafari, B.; Kotecha, K.; Indragandhi, V.; Vairavasundaram, S. A Novel Multicriteria Optimization Technique for VLSI Floorplanning Based on Hybridized Firefly and Ant Colony Systems. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 14677–14692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoo, C.-S.; Jeevan, K.; Ganapathy, V.; Ramiah, H. Variable-Order Ant System for VLSI Multiobjective Floorplanning. Appl. Soft Comput. 2013, 13, 3285–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purkayastha, A.A.; Choudhury, S.R.; Pradhan, S.N. A genetic algorithm approach for hybrid ALU design. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computing, Communication & Automation (ICCCA), Greater Noida, India, 15–16 May 2015; pp. 1298–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, T.; Dutta, H.S.; De, M. Optimization of Floor-Planning using Genetic Algorithm. Procedia Technol. 2012, 4, 825–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanavas, I.H.; Gnanamurthy, R.K. Optimal Solution for VLSI Physical Design Automation Using Hybrid Genetic Algorithm. Math. Probl. Eng. 2014, 2014, 809642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenifer, J.; Anand, S.; Levingstan, Y. Simulated Annealing Algorithm for Modern VLSI Floorplanning Problem. ICTACT J. Microelectron. 2016, 2, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanthi, J.; Gracia Nirmala Rani, D.; Rajaram, S. An Enhanced Memetic Algorithm using SKB tree representation for fixed-outline and temperature driven non-slicing floorplanning. Integr. VLSI J. 2022, 86, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Du, S.; Yang, C. A Deep Reinforcement Learning Floorplanning Algorithm Based on Sequence Pairs. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Baghel, A.S.; Agarwal, A. A Review on VLSI Floorplanning Optimization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, and Optimization Techniques (ICEEOT), Chennai, India, 3–5 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.; Deng, L.; Wong, M.D.F. Floorplanning for 3-D VLSI Design. In Proceedings of the Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference (ASP-DAC), Shanghai, China, 18–21 January 2005; pp. 405–411. [Google Scholar]

- Dorigo, M.; Gambardella, L.M. Ant colony system: A cooperative learning approach to the traveling salesman problem. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 1997, 1, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socha, K.; Dorigo, M. Ant Colony Optimization for Continuous Domains. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2008, 185, 1155–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stützle, T.; Hoos, H.H. MAX–MIN Ant System. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2000, 16, 889–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).