1. Introduction

The growing proliferation of renewable energy generation has led to a significant penetration of power electronic converters into power systems. The inherent nonlinearity of power electronic devices poses a major challenge to their large-scale integration. Adverse converter-grid interactions can trigger wideband oscillations, thereby threatening the operational security of both renewable energy systems and HVDC transmission networks [

1,

2,

3]. These issues have manifested in severe operational incidents, including abnormal transformer vibrations, widespread disconnection of renewable energy units, and sudden drops in transmitted power. Consequently, stability analysis is imperative for the successful and secure integration of renewable energy into the grid [

4,

5].

The impedance analysis method has been widely adopted for stability assessment in renewable energy grid-connected systems. By modeling the impedance of both the renewable energy converter and the grid, we can characterize the overall grid-connected system as an active impedance network [

6]. Furthermore, the stability of this equivalent network can be assessed using established criteria such as the Nyquist criterion, which in turn enables the analysis of interaction-induced oscillations between the renewable energy system and the grid. However, as converter manufacturers typically withhold structural parameters for proprietary reasons, the resulting lack of transparency makes it difficult to accurately characterize converter impedance through conventional mathematical modeling [

7]. The ability to directly characterize converter impedance has therefore made impedance measurement techniques a prominent focus for both researchers and industry practitioners [

8,

9]. To quantitatively evaluate the stability of renewable energy grid-connected systems, extensive research has been conducted on impedance measurement devices. By injecting perturbations and measuring the resulting voltage and current responses on the converter side, these devices estimate the system’s equivalent impedance using only external signals, without requiring internal parameters. Importantly, since this process requires no internal converter parameters, impedance measurement devices fundamentally support the real-world application of stability analysis [

9,

10,

11].

Numerous studies have been conducted on the design and implementation of impedance measurement devices. The impedance measurement device can be classified into series topology and parallel topology based on the voltage disturbance injection method and current disturbance injection method. For the former, ref. [

12] presented a design method for measuring the impedance of traction networks. Furthermore, a butterfly perturbation circuit was introduced to inject chirp signals into the railway traction power system for converter impedance measurement [

13]. However, these methods are not applicable to grid-connected renewable energy systems. Ref. [

14] introduced a series-type impedance measurement device capable of accurately measuring the impedance of high-voltage, high-capacity renewable energy stations. A cascaded H-bridge was used to inject perturbation signals into the system [

15], and the mechanism of DC-side voltage instability under high output power conditions was revealed. However, the use of open-loop control to generate the perturbation signals limits the precision of the disturbance control. Nevertheless, the voltage perturbation injection unit requires redesigning and reconstructing parts of the power lines during installation, resulting in complex operations and high installation costs. Therefore, impedance measurement devices based on current perturbation injection are more suitable for renewable energy grid-connected systems. Ref. [

16] proposed injecting controllable sinusoidal perturbation signals using a DC/AC converter, which reduces the instability risk to some extent. However, due to its topological constraints, this method is limited to low-voltage and small-capacity systems. Ref. [

17] proposed a modular impedance measurement unit based on silicon carbide (SiC) devices, suitable for systems with DC voltages up to 1 kV and AC voltages not exceeding 800 V. However, availability and reliability constraints of high-voltage SiC devices limit this solution’s widespread application [

18]. In terms of perturbation injection strategies, ref. [

19] proposed a Gaussian process regression-based data-driven algorithm that accurately predicts inverter impedance models with only minimal datasets. Ref. [

20] introduced an artificial neural network (ANN)-based impedance identification method for multiple operating points. However, this approach exhibits strong dependence on data quality and quantity. However, this approach is highly dependent on both data quality and volume. Moreover, this reliance consequently obstructs the analysis of system stability mechanisms and is detrimental to subsequent controller design. Reference [

14] proposes a fixed-modulation-ratio-based voltage perturbation injection method, but it achieves this at the cost of wide-bandwidth injection capability and control response speed. In [

18], a Pseudo-Random Binary Sequence (PRBS) is employed as the target output perturbation signal. While this enables rapid measurement and wide-frequency perturbation injection, the resulting signal exhibits a low signal-to-noise ratio and high sensitivity to nonlinearities and harmonics, thereby significantly limiting its practical engineering value. References [

21,

22] propose a wide-bandwidth impedance measurement method for measuring the impedance of electroacoustic transducers. This provides a new solution for impedance measurement in high-voltage, strongly nonlinear renewable energy systems. In summary, impedance measurement devices for renewable energy grid-connected systems face two primary challenges:

- (1)

Existing impedance measurement systems are inadequate for renewable stations due to their high-voltage (>10 kV) and high-power (10–20 MW) operation;

- (2)

The impedance measurement device requires injection of perturbation currents in the 10 Hz–1 kHz frequency range, for which existing injection control methods fail to meet the stringent requirements for both amplitude and frequency accuracy.

To address these challenges, this paper proposes a wide-band impedance frequency characteristic measurement device suitable for 10 kV power grid systems. First, the main circuit topology of a harmonic generation unit is designed based on a cascaded structure. To enable the injection of harmonic currents with controllable amplitude and frequency into the power grid, a dedicated control strategy for the harmonic generation unit is developed, which includes DC voltage control, voltage balancing control, and harmonic current control. By acquiring voltage and current data at the point of common coupling (PCC), the impedance frequency characteristics at the input port of a grid with high renewable energy penetration are directly calculated over a wide frequency range up to 1000 Hz. Finally, the proposed measurement system is validated using a Real-Time Digital Simulator (RTDS)-based hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) experimental platform, demonstrating its capability to accurately obtain the impedance characteristics of renewable energy systems in accordance with the design requirements.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- (1)

By utilizing the engineering parameters of the renewable energy station grid-connected system, we select a cascaded H-bridge (CHB) topology to enhance the voltage level of the device. Furthermore, based on Inter-phase DC voltage control Intra-phase voltage control, the port voltage of the device is maintained constant, thereby minimizing its impact on the system under test.

- (2)

Aiming at the requirements of wide-bandwidth impedance measurement, a perturbation injection strategy based on quasi-proportional-resonant (PR) control is proposed. This approach capitalizes on the advantage of quasi-PR control, which offers both frequency selectivity and fast response speed, to achieve wide-frequency-band perturbation current injection.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the principle of impedance measurement and designs the topology of an impedance measurement device suitable for high-voltage-level renewable energy grid integration systems.

Section 3 proposes a PR control-based disturbance injection strategy to achieve wide-frequency-domain current disturbance injection.

Section 4 provides experimental validation through hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) simulations, demonstrating the efficacy of the proposed device design and control strategy, along with the resulting impedance measurement results.

2. Impedance Measurement Principle and Device Structure Design

2.1. Impedance Measurement Principle

The resonance phenomenon is directly manifested as the waveform distortion of voltage and current signals at the access point of the new energy grid, and the relationship between voltage and current at different frequencies is reflected in the frequency domain impedance. Therefore, impedance is used to characterize the input and output characteristics of the new energy power supply–public power grid interconnection system.

Using a PV power station as an example,

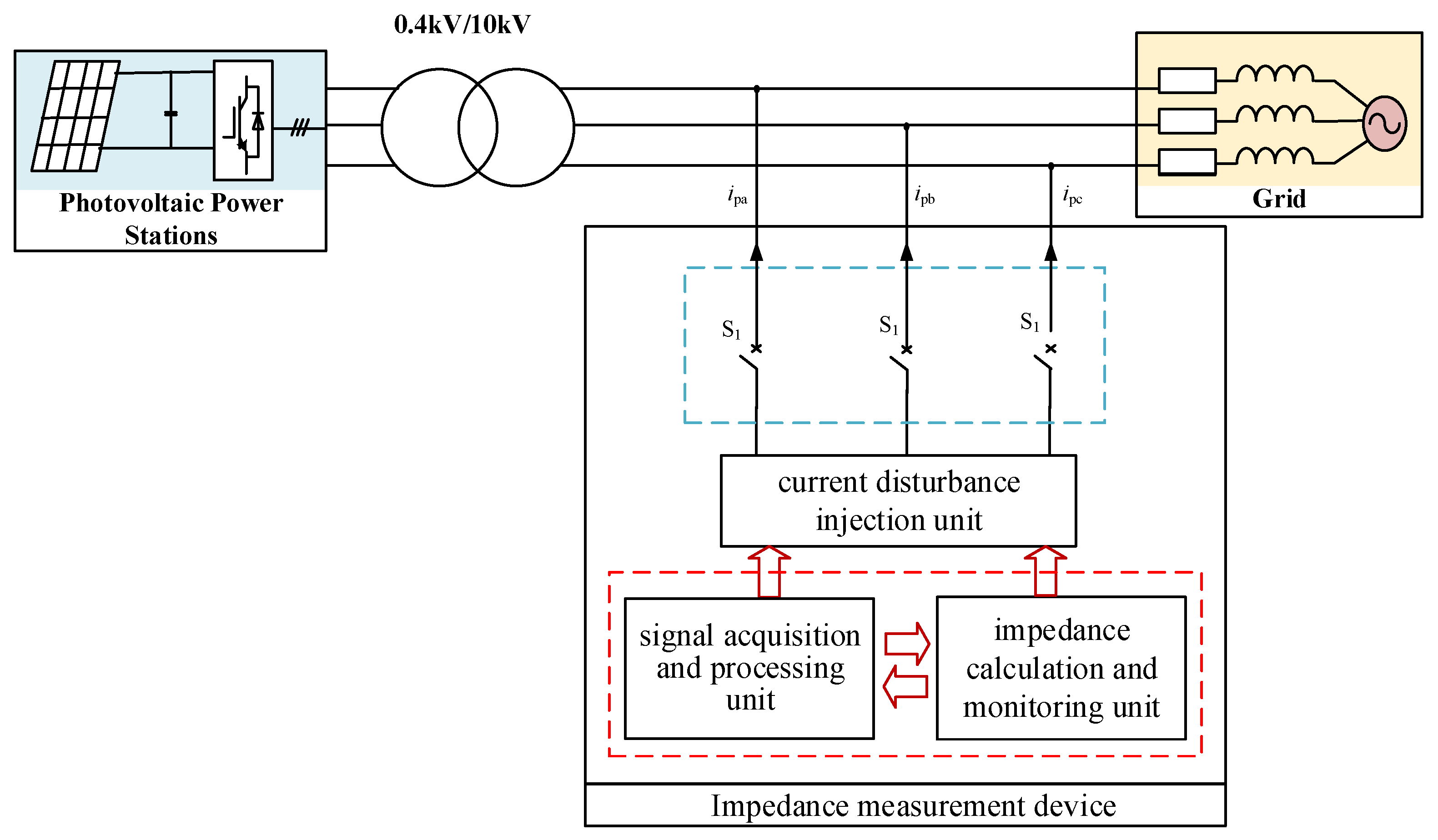

Figure 1 shows the topology of the impedance measurement of the power grid system, including the photovoltaic power generation terminal, the public power grid and the impedance measurement device.

Using a photovoltaic power station as a case study,

Figure 1 shows the topology for impedance measurement within a grid-connected system. The system comprises the PV power station terminal, the public power grid, and the impedance measurement device. The photovoltaic power generation terminal includes photovoltaic panels, photoelectric converters and station step-up transformers. The public power grid is composed of grid impedance and ideal power supply.

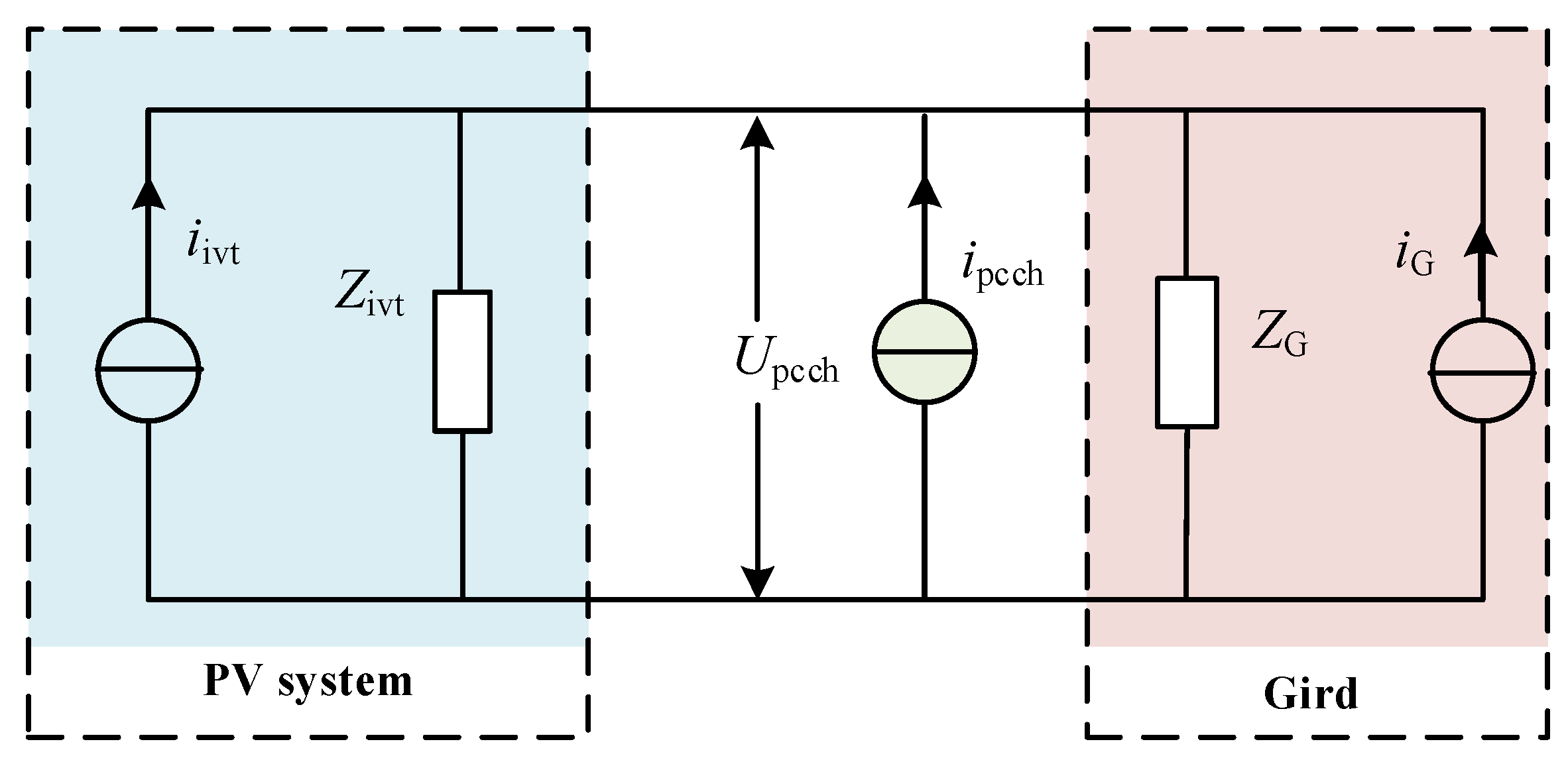

According to Norton’s theorem, the field side port of photovoltaic power generation can be equivalent to the parallel connection of photovoltaic field source

iivt and photovoltaic impedance

Zivt. The public grid port can be equivalent to the circuit topology of the equivalent impedance Z

G of the traditional power supply

iG parallel line. The equivalent circuit of the system is shown in

Figure 2. The harmonic impedance measurement device is put into the common connection point between the photovoltaic power station and the public power grid. By injecting the harmonic current with controllable amplitude and frequency, and measuring the voltage response

Upcch and the current response

Ipcch at the injection point, the impedance frequency characteristic curve of the common connection point port can be obtained.

By collecting the system response data after the disturbance signal is injected and analyzing according to (1), the impedance characteristics of the system to be tested can be obtained.

The value of I(s) is taken as iivt or iG. The photovoltaic impedance Zivt and gird impedance ZG can be calculated using (1).

The new energy system is a three-phase AC system, so the equation of the impedance characteristics of the new energy grid-connected converter is (2). In the algorithm function of the harmonic generation unit, the impedance data acquisition module performs fast Fourier transform on the collected voltage and current signals of the common connection point port to obtain the three-phase current phasor

ipma,

ipmb,

ipmc at a specific frequency, and the corresponding system impedance voltage drop phasor

vpma,

vpmb,

vpmc is

2.2. Structure of the Impedance Measurement Device

The impedance measurement device primarily consists of three key components: a signal acquisition and processing unit, a current disturbance injection unit, and a broadband impedance calculation and monitoring unit, as shown in

Figure 1.

The signal acquisition and processing unit is designed to measure and extract the current and voltage components at the disturbance frequency from the high-voltage side port of the Photovoltaic power station. The broadband impedance calculation and monitoring unit is responsible for computing the magnitude and phase of both the converter output impedance and the grid impedance, thereby enabling real-time assessment of oscillation risks in the system. The signal acquisition and processing unit and the broadband impedance calculation and monitoring unit are essentially identical in both high-voltage and low-voltage impedance measurement devices. Therefore, these components will not be redundantly elaborated in this paper.

The current disturbance injection unit is required to inject a perturbation current with an amplitude ranging from 1% to 10% of the photovoltaic power station rated current, covering a frequency spectrum from 10 Hz to 1 kHz. The current disturbance injection unit is a critical component in the development of impedance measurement devices. Similarly, the core of the current disturbance injection unit lies in its main circuit topology and control strategy. This paper will focus on these two aspects and propose an impedance measurement device suitable for high-voltage and high-capacity renewable energy power stations.

2.3. Topology of the Current Disturbance Injection Unit

Most existing low-voltage impedance measurement devices are based on a two-level voltage source converter (VSC) topology. However, due to the limited voltage withstand capability of their power switching devices, such systems are often inadequate for performing impedance measurements in high-voltage renewable energy generation facilities. The advancement of multilevel converter topologies and their associated control strategies has led to substantial improvements in the voltage level and power capacity of power electronic interfaces. To address the impedance measurement requirements in renewable energy power station, this paper adopts a three-phase cascaded H-bridge converter-based topology for the disturbance injection unit.

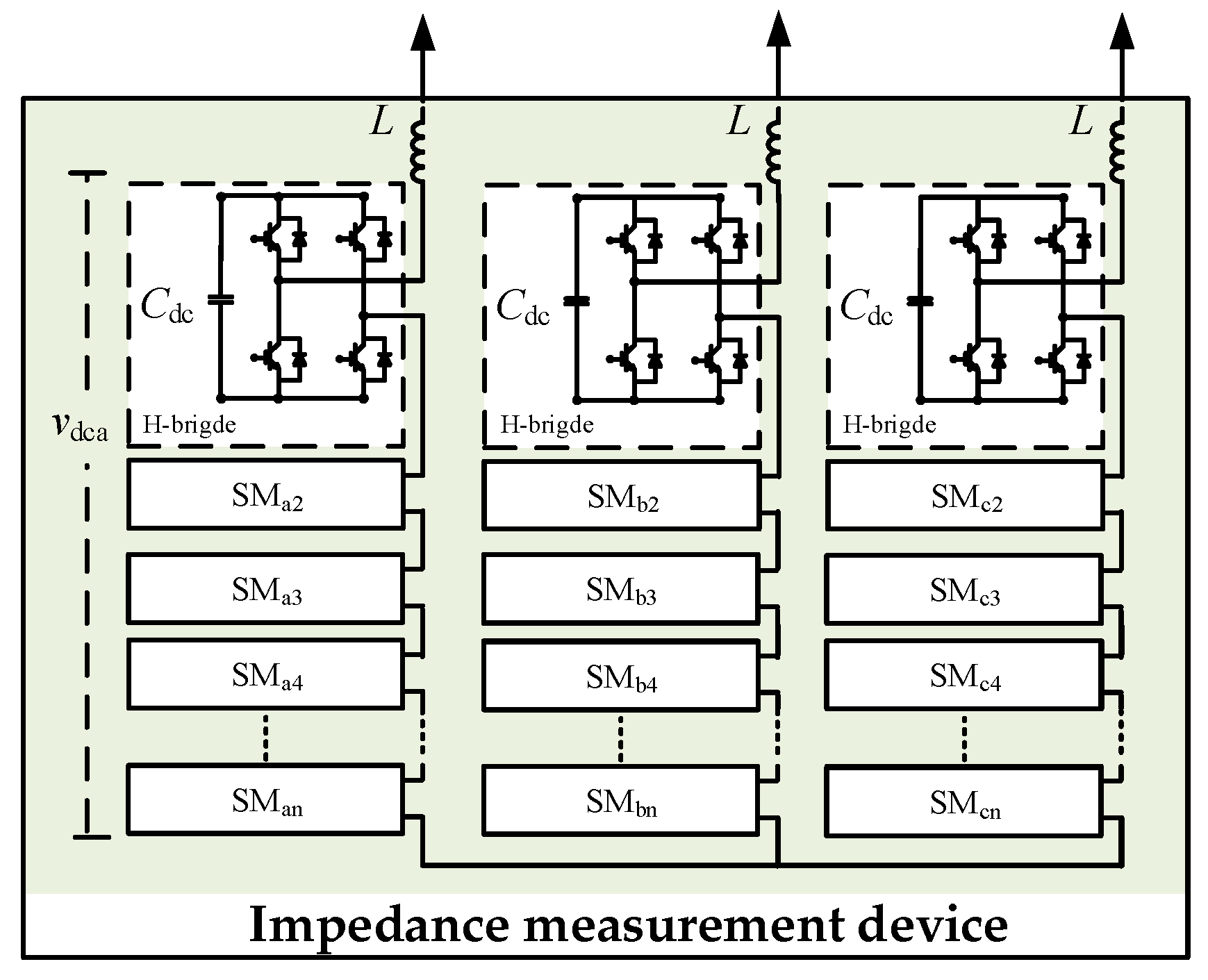

Since the harmonic converter does not require significant negative-sequence output capability, and the complexity of the control system for a three-phase star connection is lower than that of a delta connection, a three-phase H-bridge topology with a star connection is adopted in the proposed measurement system, as shown in

Figure 3. Where

vdca represents the DC voltage of phase-a, and SM stands for the submodule of the bridge arm.

This design can not only significantly improve the power quality of the output current, but also improve the voltage level of the system. The H-bridge power module unit not only has good installation and debugging characteristics, but also its modular design makes the whole system highly scalable and easy to increase or decrease modules according to actual needs. In addition, this modular design also supports redundant operations. The standby module can be configured in the system and switched in time when the main module fails to ensure the stability and reliability of the system.

Assuming that the DC-side voltage of each H-bridge submodule is equal, the AC voltage at the cascaded H-bridge output port can be expressed as

In the above expression, uc(t) represents the AC-side output voltage of the converter; N is the number of cascaded H-bridge submodules; Udc denotes the capacitor voltage of each submodule; m indicates the carrier harmonic order; M is the modulation index of the modulated wave; ω1 and ωc are the angular frequencies of the fundamental and the carrier, respectively; J2k−1 represents the Bessel function of order 2k − 1.

To enable the harmonic converter to generate high-order harmonics, it is essential to appropriately control the harmonic frequency components in the output voltage of the cascaded H-bridge, which are expressed as 2Nmωc + (2k − 1)ω1. Both the converter topology and control simplicity must be considered comprehensively. A smaller number of H-bridge submodules increases the voltage rating required for each submodule, which is beneficial for control stability. Conversely, a larger number of submodules improves the output voltage level and increases the equivalent switching frequency of the converter, which is advantageous for generating high-frequency harmonic voltages. Therefore, the number of cascaded H-bridge submodules should be selected based on the voltage level of photovoltaic power station and the required equivalent switching frequency of the harmonic converter to ensure the injection of controllable harmonic currents.

3. Control Strategy of the Current Disturbance Injection Unit

The control objectives of the current disturbance injection unit are twofold: (1) to achieve broadband, high-fidelity current output, and (2) to maintain stable port voltage. The first objective is achieved through a precision current control strategy that injects a disturbance current with a frequency sweep from 10 Hz to 1 kHz and an amplitude ranging from 1% to 10% of the rated current of the renewable power station, thereby meeting the requirements for wideband impedance measurement. The second objective is achieved through a voltage control scheme that maintains balanced total DC capacitor voltage among all H-bridge modules inter-phase and ensures voltage balance across the capacitor in each submodule intra-phase.

This section addresses the aforementioned challenges from two distinct perspectives. In terms of topology, this paper adopts a CHB structure, where series-connected submodules enable the setup to accommodate high voltage levels. As for the control strategy, inter-phase DC voltage control and intra-phase voltage control are employed to coordinate voltage balancing among the submodules and ensured stable system output voltage. Additionally, quasi-PR control is utilized, leveraging its high frequency selectivity to achieve wide-band perturbation current injection.

3.1. Voltage Control Strategy of the Current Disturbance Injection Unit

Maintaining the balance of the DC-side voltages during the operation of cascaded H-bridge modules is critically important. This not only enhances the reliability and stability of the overall system, but also prevents additional losses and potential faults caused by voltage imbalances, thereby extending the service life of the impedance measurement device. To address this issue, this study adopts a hierarchical voltage balancing control architecture, which consists of two main components: inter-phase DC voltage control and intra-phase voltage control. These two control layers operate independently without mutual interference and function in a coordinated manner.

- (1)

Inter-phase DC voltage control

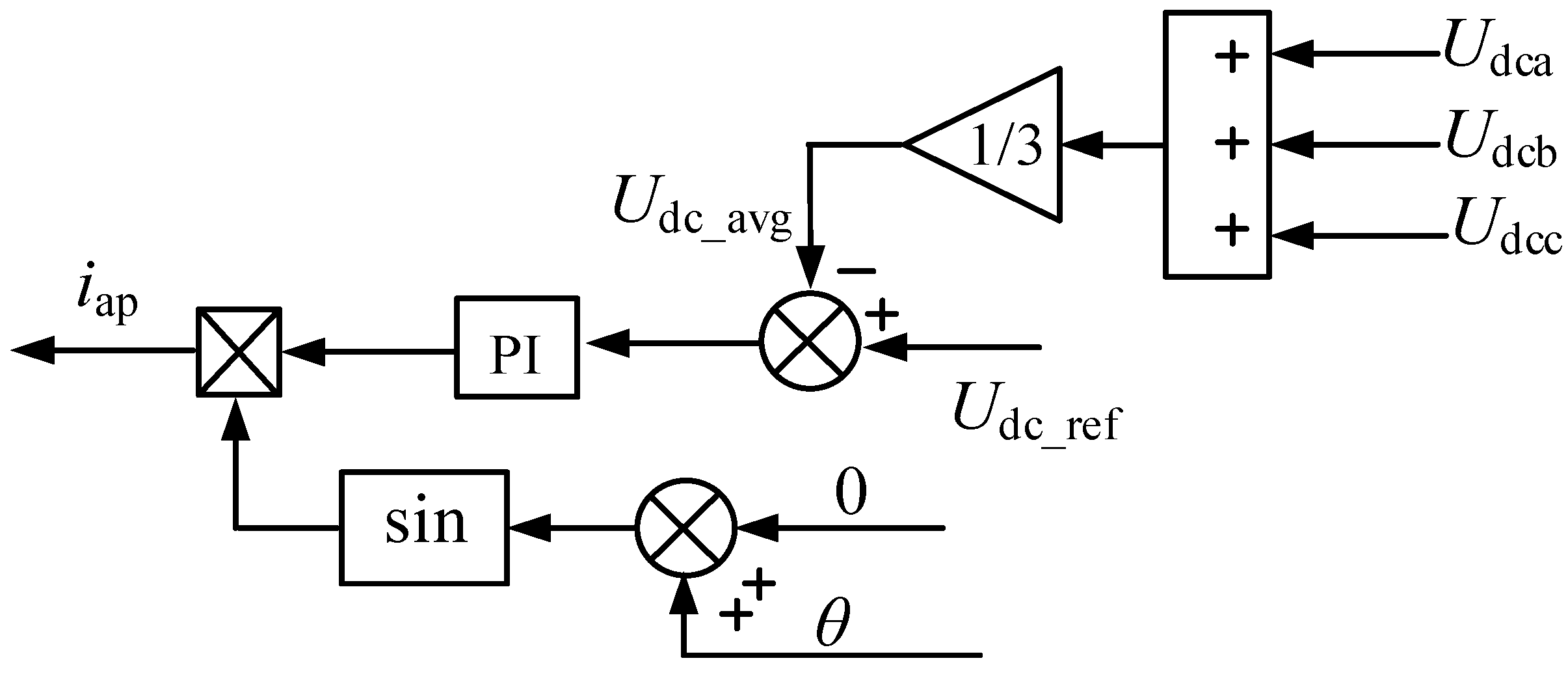

The inter-phase DC voltage control loop is illustrated in

Figure 4.

Udca,

Udcb,

Udcc represent the sum of the equivalent capacitor voltages in each phase of the current disturbance injection unit.

Udc_ref denotes the reference value for the single-phase DC capacitor voltage. By comparing the reference value with the measured actual voltages, error signals for the three-phase voltages are obtained. These error signals are then fed into their respective proportional–integral (PI) controllers for regulation. The outputs of the controllers are subsequently multiplied by unit-amplitude sinusoidal signals of the corresponding phases, resulting in the steady-state current components

iap,

ibp,

icp that are used for DC voltage regulation.

Figure 4 shows that the total DC-side voltages of each phase-

Udca,

Udcb and

Udcc are obtained by summing the voltages of their corresponding submodules. The detailed mathematical expression is given in Equation (4), where the parameter

n denotes the index of the sub-power modules within each phase. In addition, the function of the PI controllers illustrated in the figure is described mathematically in Equation (5), which is used to regulate system voltage stability and improve dynamic response performance.

- (2)

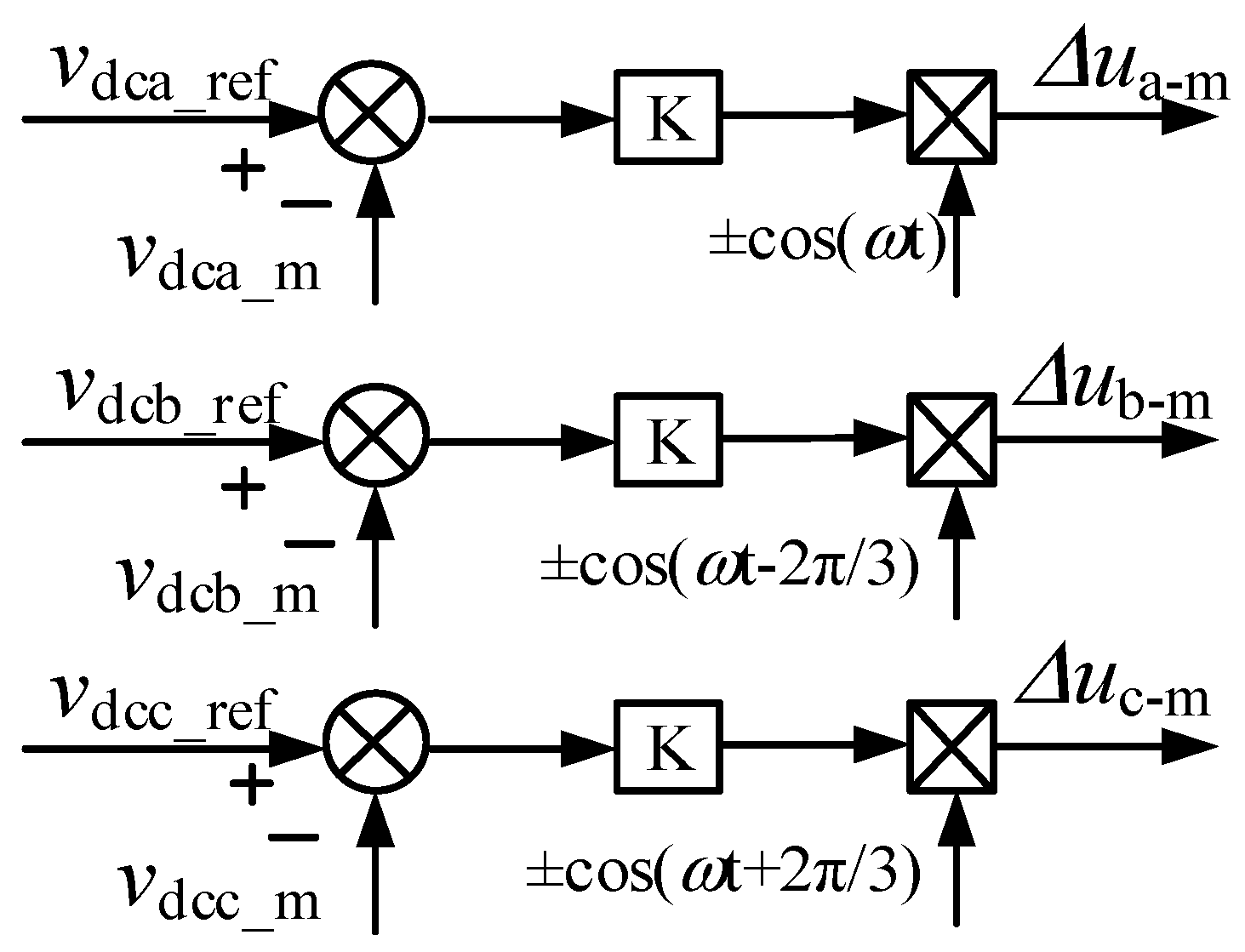

Intra-phase voltage control

Each phase of the impedance measurement device typically comprises multiple H-bridge power units, with their AC-side outputs connected in series. The DC-side capacitor voltages of the individual H-bridge modules are independently regulated. However, during actual operation, due to inevitable differences in power losses among the converter units, it is often difficult for the system to achieve an ideal balanced operating state. Although all submodules are triggered by identical pulse commands, variations in current and voltage, as well as hardware inconsistencies and environmental influences, can lead to discrepancies among the units.

Therefore, to ensure the stable operation of the cascaded H-bridge structure, capacitor voltage balancing control must be implemented. In this paper, the method illustrated in

Figure 5 is adopted to achieve this objective. Where K is the scaling parameter of intra-phase voltage control.

Figure 5 shows that

vdca_m represents the capacitor voltage of the

m-

th submodule in phase

a, while

vdca_ref denotes its corresponding reference value. To achieve voltage balancing among the submodules within the same phase, minor adjustments can be applied to their respective sinusoidal modulation waveforms. The required compensation voltage signal is determined based on the actual operating conditions of the system, specifically whether the converter needs to inject or absorb reactive power.

Since the balancing of capacitor voltages within a phase primarily relies on power redistribution, the output of the PI controller is multiplied by the sinusoidal signal cos ωt to generate an AC quantity. This process effectively transforms the DC control output into an AC component synchronized with the system frequency. The final control output can be expressed as (6).

This regulation method enables precise control of the capacitor voltage in each submodule, thereby maintaining a balanced operating state. By adjusting the compensation voltage signals for each submodule, the final three-phase voltage modulation signals are generated. After modulation, these signals effectively govern the operating states of the individual submodules, ensuring balanced and stable capacitor voltages across the entire system.

3.2. Current Control Strategy of the Current Disturbance Injection Unit

The core function of the impedance measurement device is to accurately and rapidly generate current signals with the required amplitude and frequency. Therefore, selecting an appropriate current control strategy is critical. Common control strategies include hysteresis control, PI control, deadbeat control, quasi-PR control, and intelligent control techniques. A comparison of the advantages and disadvantages of these different algorithms is presented in

Table 1.

Impedance measurement is inherently a frequency-domain operation. The frequency selectivity of quasi-PR control naturally aligns with the point-by-point frequency scanning requirement of impedance measurement. Furthermore, quasi-PR control offers a favorable balance between stability and dynamic performance. Moreover, it effectively mitigates the adverse effects of system parameter variations and frequency deviations during operation. This ensures that the parallel-type impedance measurement device can operate efficiently and stably under varying conditions. Therefore, this paper proposes a current inner-loop control strategy based on quasi-PR control.

As a result, this study adopts quasi-PR control as the current inner-loop control strategy. The corresponding control function of the quasi-PR controller is given in Equation (7).

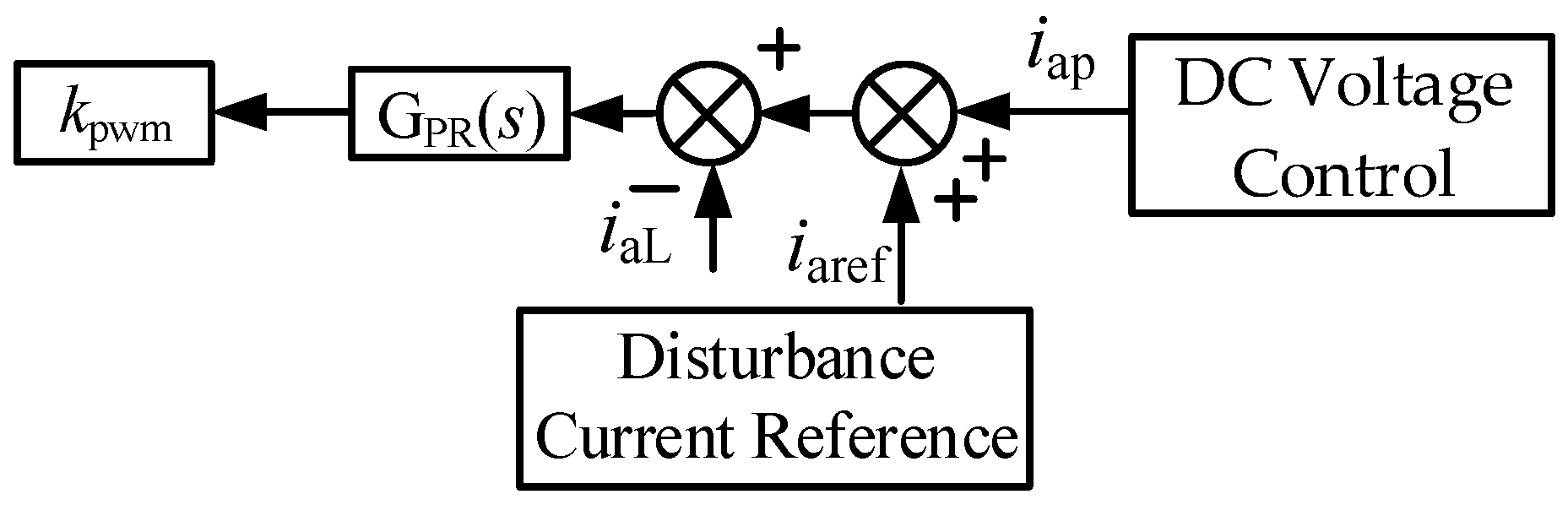

The structure of the AC current control adopted in this study is illustrated in

Figure 6, which shows that the input variable

iaL represents the output arm current of phase a from the cascaded H-bridge, while

iaref denotes the reference value of the disturbance current, which contains the desired current amplitude and frequency components. The control structure first generates the signal

iap through the DC voltage control loop. This signal is then compared with both the sampled arm current and the reference disturbance current. The resulting error is processed by the quasi-PR controller, and the controller’s output is subsequently sent to the modulation control stage.

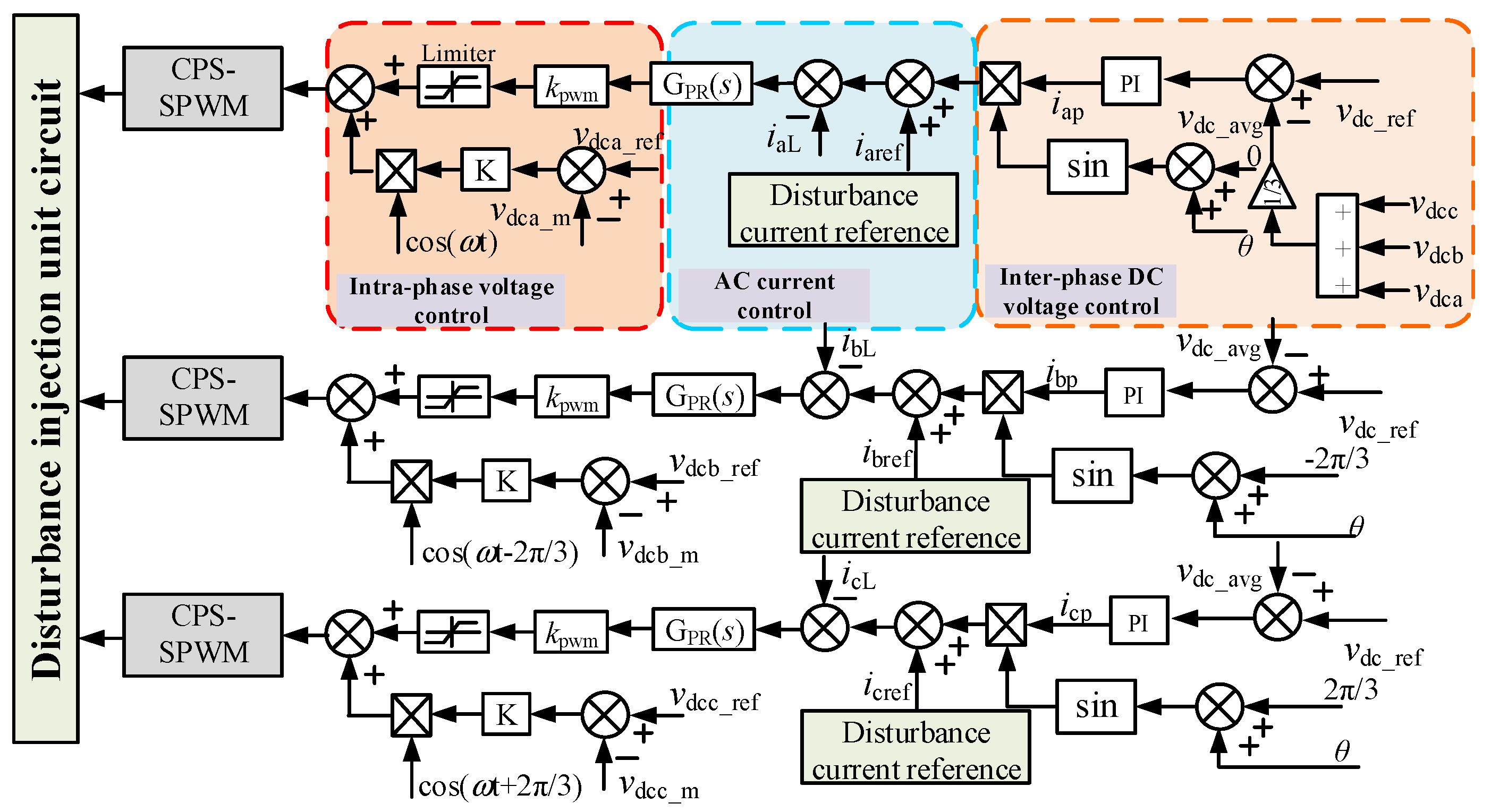

3.3. Overall Control Strategy of the Current Disturbance Injection Unit

In summary, the overall control strategy for the current disturbance injection unit can be derived as illustrated in

Figure 7. The proposed control scheme not only enables wide-frequency-range and high-precision current output but also ensures port voltage stability, thereby providing effective current perturbation injection for broadband impedance measurement applications.

4. Verification

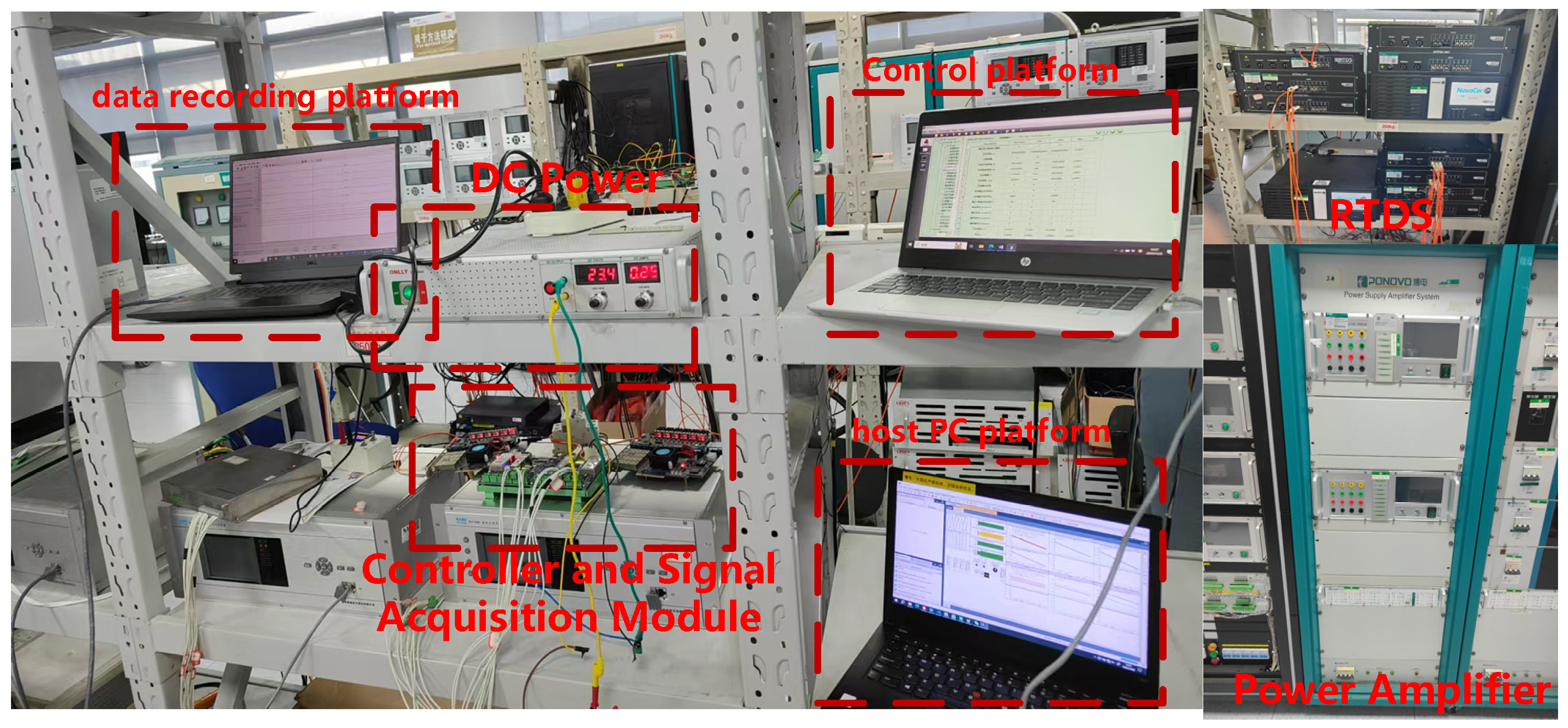

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed main circuit topology and control strategy for the impedance measurement device, a hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) experimental platform of a grid-connected photovoltaic system incorporating the proposed device was established based on RTDS, as shown in

Figure 1. The main circuit parameters and control parameters of the disturbance injection unit are shown in

Table 2.

The HIL experimental platform in this paper was composed of the following components: three laptops, a controller with a signal acquisition module, a DC power supply, a digital power amplifier, and an RTDS simulator. The three computers function as the host PC platform, the control platform, and the data recording platform, respectively. The host PC is connected to the RTDS simulator via Ethernet. It utilizes the RSCAD FX 2. 1 software to construct the main circuit model, enables real-time parameter adjustment, and allows for the observation of changes in the system’s operational status. The data recording platform utilizes both FileZilla 3. 39. 0 and WaveEv 1. 07. 03 software: the former is used to record and save system operational data, while the latter is dedicated to displaying the saved .cfg format waveform files generated by the former. Data acquisition and verification of the proposed control strategy are carried out by the Digital Signal Processor (DSP) controller and signal acquisition module. The interface and energy adaptation between the real-time simulator and the controller are implemented by the digital power amplifier. Power for the controller is supplied by the DC output source.

The proposed impedance measurement method is deployed on two primary platforms: a DSP-based controller and a CPU + FPGA real-time simulator. For the PV power station, a pre-packaged model from the RSCAD library, which incorporates the complete main circuit and control system, is employed. Furthermore, the main circuit topology based on the cascaded H-bridge is constructed within RSCAD. The CPU + FPGA architecture is utilized to meet the simulation scale requirements of large grids and the accuracy demands for simulating power electronic switching details. The proposed wide-bandwidth perturbation injection strategy is implemented in the DSP controller. The hardware implementation scheme is as follows: The RTDS outputs the system voltage and current signals to the controller through its I/O board and data acquisition card. Based on the system operational data and perturbation signal commands, the controller generates PWM control signals. These signals drive the impedance measurement device within the RTDS to output the required perturbation, thereby achieving impedance measurement for the renewable energy station. The HIL platform forms a closed real-time testing loop, enabling the safe and precise verification of the proposed impedance measurement method in a laboratory environment.

Based on the control strategies proposed earlier, a hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) experimental platform for the impedance measurement device has been established, as shown in

Figure 8. The platform consists of a host computer, controller and signal acquisition module, DC power source, digital power amplifier, and an RTDS cabinet. The proposed control strategy is implemented on a control board with a digital signal processor (DSP) and field-programmable gate array (FPGA) architecture. The main circuit of the photovoltaic power station and its control algorithm, along with the main circuit of the impedance measurement device, are executed in the RTDS platform.

4.1. Verification of Current Disturbance Injection Strategy

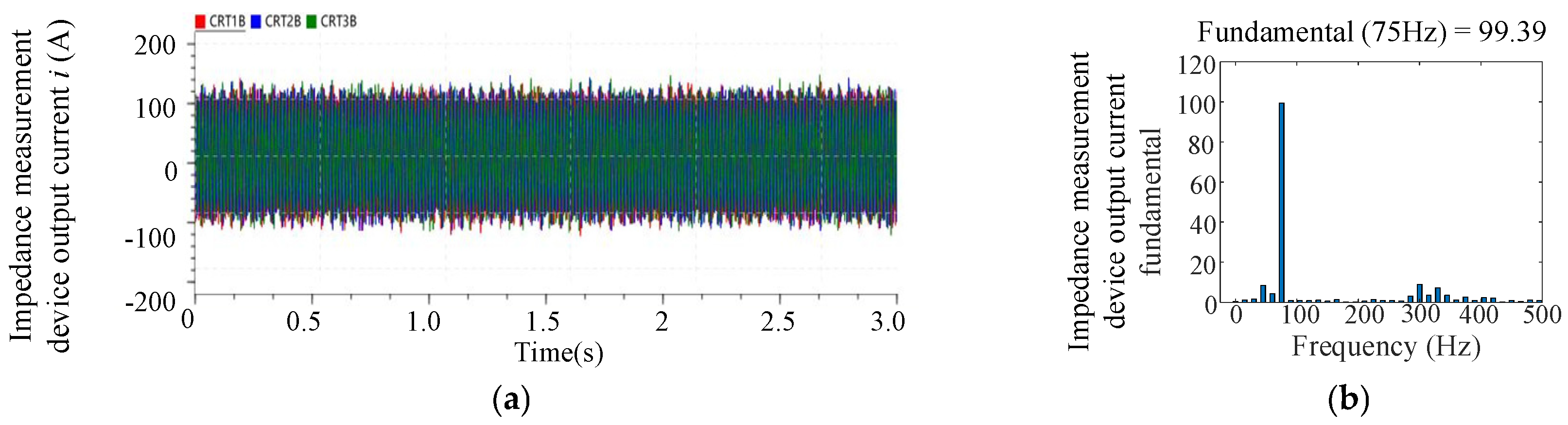

The proposed control strategy was validated through simulation using the established HIL impedance measurement system. A disturbance current with an amplitude of 100 A and a frequency of 75 Hz was applied, and the injection performance of the current disturbance signal across the entire disturbance frequency band was observed, as illustrated in

Figure 9. As shown in the figure, the impedance measurement device injects a 75 Hz disturbance current with an amplitude of 100 A into the system under test.

Furthermore, to ensure the stable and reliable operation of the impedance measurement equipment, it is also essential to maintain the stability of the DC-side capacitor voltage. The capacitor voltage of each H-bridge module is regulated at 900 V in this paper. The capacitor voltages of each H-bridge module in the disturbance injection unit closely with their design values, as shown in

Figure 10.

To further validate the effectiveness of the proposed control strategy, the frequency command of the disturbance current was set to 25 Hz, with amplitude commands set to 30 A, 50 A, 100 A, and 150 A, respectively. The discrepancies between the command values and the actual output values are compared in

Table 3.

Furthermore, the amplitude command of the disturbance current was set to 50 A, with frequency commands set to 75 Hz, 125 Hz, 350 Hz, and 500 Hz, respectively. The discrepancies between the command values and the actual output values are compared in

Table 4.

As observed in

Table 4, the absolute error between the reference and the output values exhibits an increasing trend with the rising perturbation frequency reference. This phenomenon can be attributed to frequency distortion inherent in the digital discretization process, which introduces an error in the amplitude at the target frequency [

23]. Moreover, this distortion is exacerbated at higher frequencies, leading to a progressively larger amplitude error.

As indicated in

Table 3 and

Table 4, the impedance measurement device accurately generates perturbation currents at specified frequencies and amplitudes according to the commanded values, with an output error of less than 4%.

Therefore, the developed system is capable of injecting wide-bandwidth and high-accuracy disturbance currents, thereby fulfilling the requirements for precise impedance measurement.

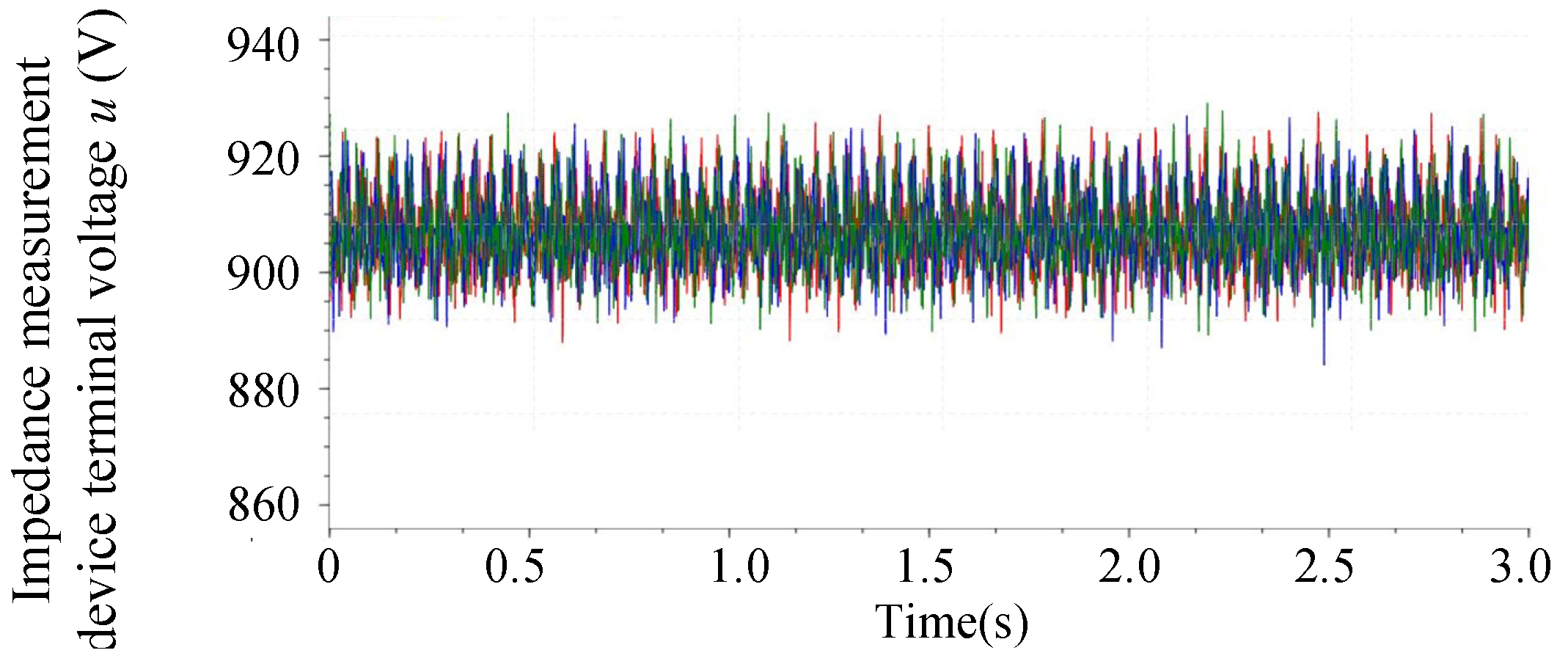

4.2. Verification of Passive Impedance Measurement Results

The photovoltaic power stations in

Figure 1 was replaced with passive impedance components—specifically, a resistor-inductor (RL) series circuit and a resistor-capacitor (RC) parallel circuit—to validate the accuracy of the impedance measurements. The component values were set to 10 Ω, 3 mH, and 15 μF, respectively. A comparison between the measured and theoretical impedance values is presented in

Figure 11.

As shown in

Figure 11, the magnitude and phase frequency responses of the measured impedance closely match those of the actual impedance, confirming the effectiveness of the proposed measurement device.

4.3. Verification of PV Power Station Grid Connection System Impedance Measurement Results

The main circuit and control algorithm of the photovoltaic (PV) power station are implemented using pre-built encapsulated models within the RTDS environment. While the control parameters of the station can be externally modified, its detailed internal circuit structure remains inaccessible. As a result, obtaining an accurate theoretical model of the station is not feasible—a situation commonly encountered in practical engineering scenarios. In this section, the impedance-based stability assessment method is employed: the impedance of both the PV power station and the grid are measured, and the frequency points with high oscillation risk are identified through impedance analysis. To validate the accuracy of the impedance measurements, system oscillations are emulated by intentionally adjusting the control parameters of the PV power station.

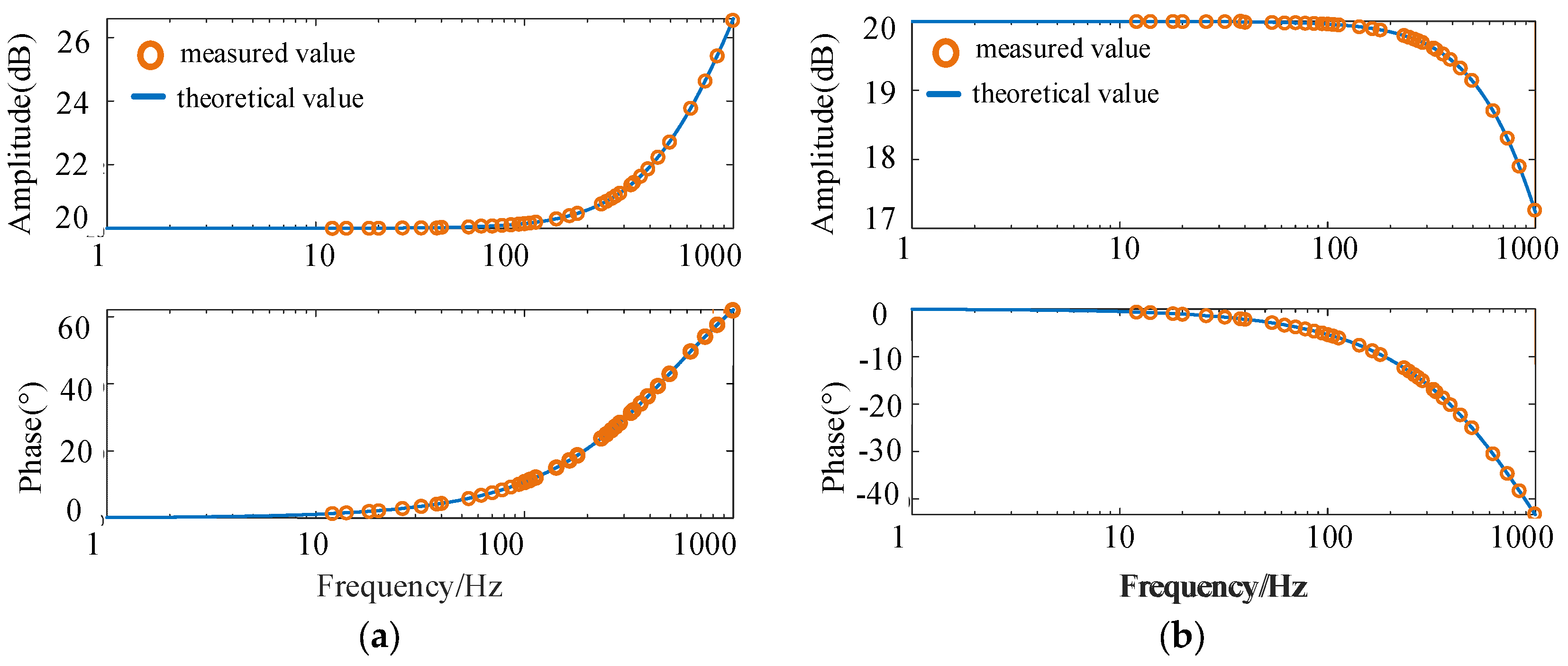

The obtained impedance of the renewable energy converter and the power grid are shown in

Figure 12. An impedance-based stability analysis confirms that the system is stable under the measured conditions.

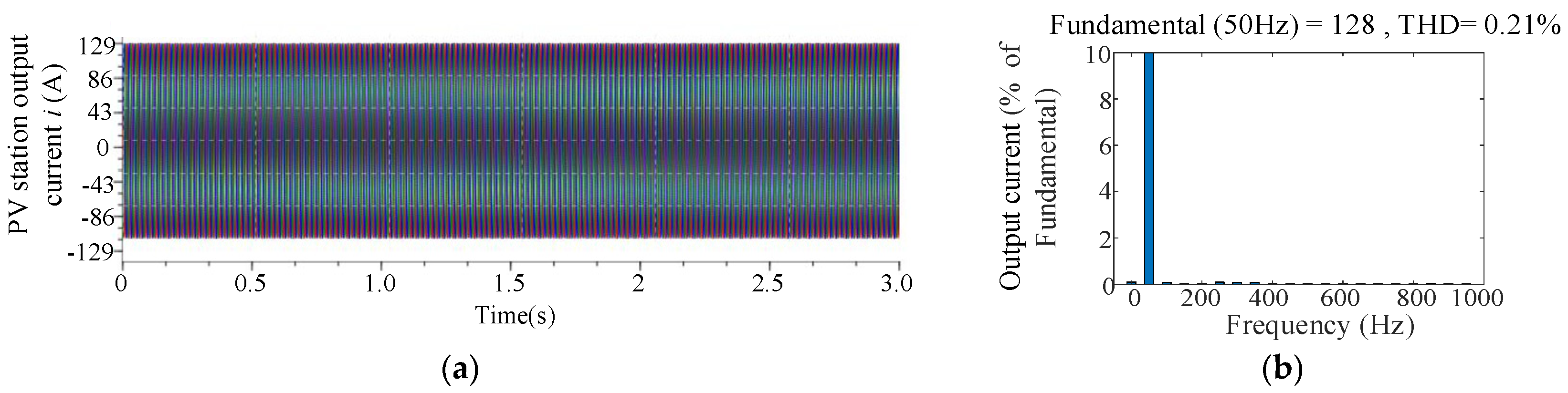

Figure 13 presents the grid-side current waveform at the PCC along with its FFT analysis. As shown in the figure, the magnitude curve of the PV station impedance does not intersect with that of the grid impedance. Moreover, at frequencies where their magnitudes are close, the phase difference does not approach 180°. The results demonstrate that the system remains stable, which is consistent with the conclusions drawn from the impedance-based analysis.

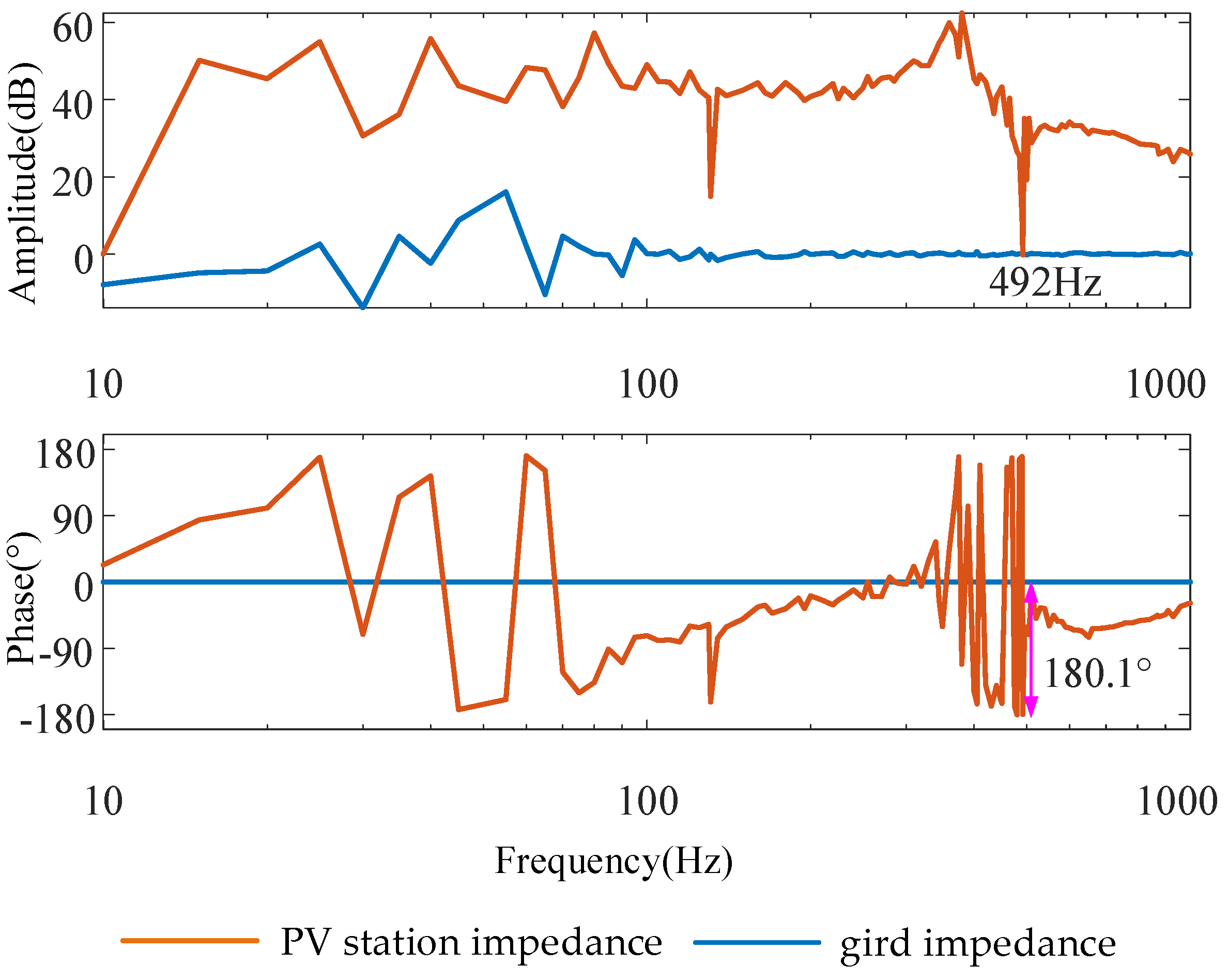

Under the operating condition shown in

Figure 10, the proportional and integral gains of the outer voltage loop controller of the PV converter,

kp_Udc and

ki_Udc are both set to 5, while the proportional and integral gains of the inner current loop controller,

kp_I and

ki_I are both set to 0.5. As can be seen from

Figure 12, the system exhibits a high risk of oscillation at 116 Hz, 492 Hz, and 585 Hz.

To further investigate the accuracy of the proposed impedance measurement method, the PI controller parameters in the voltage and current loops were modified to simulate system oscillations. Impedance characteristics of the PV station under different operating conditions were measured and compared with the grid impedance to analyze system stability.

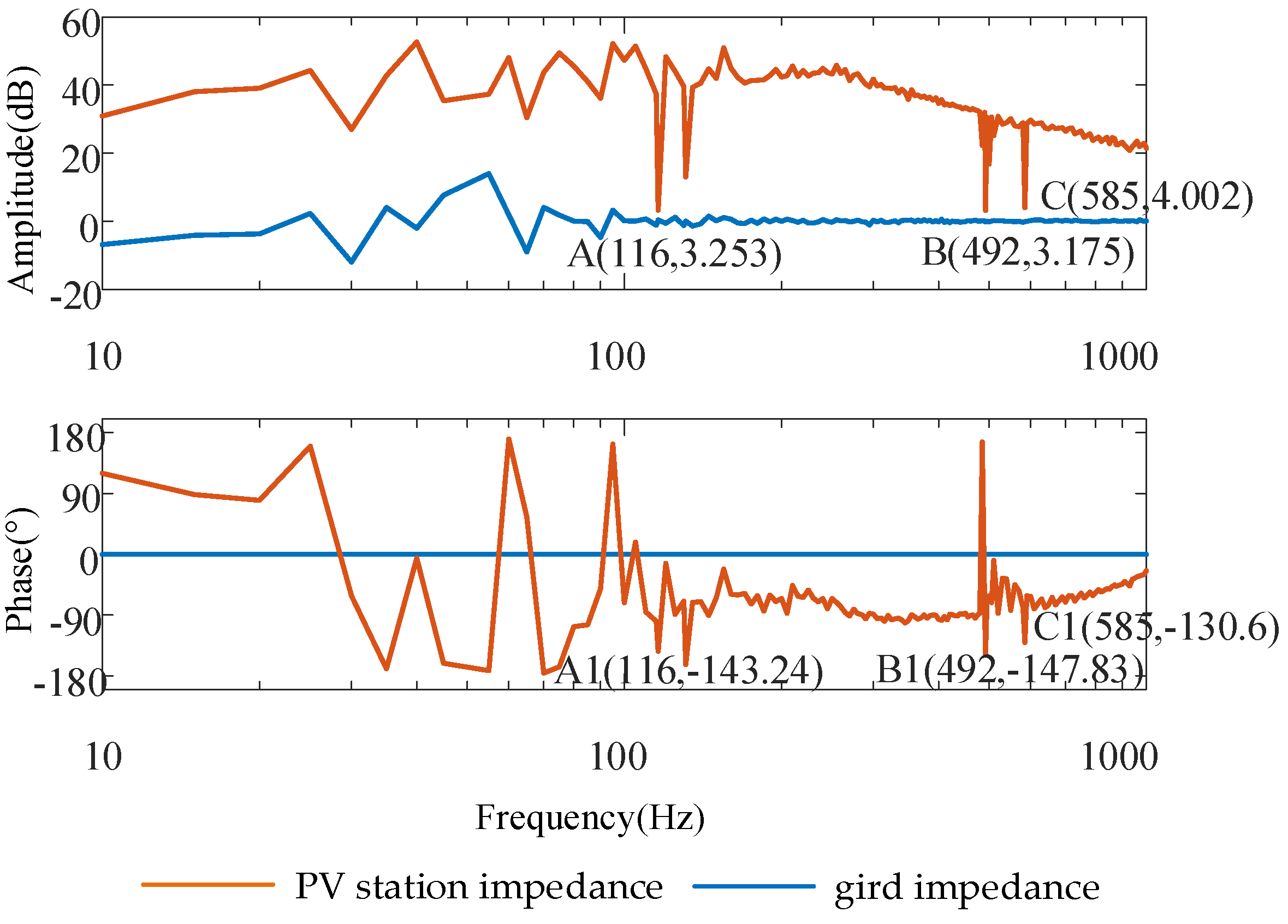

Subsequently, in case 1, the controller parameters of the PV converter are modified: the voltage outer loop gains

kp_Udc and

ki_Udc are adjusted to 30 and 5, and the current inner loop gains

kp_I and

ki_I are adjusted to 0.132 and 0.5. The obtained impedance of the renewable energy converter and the power grid is shown in

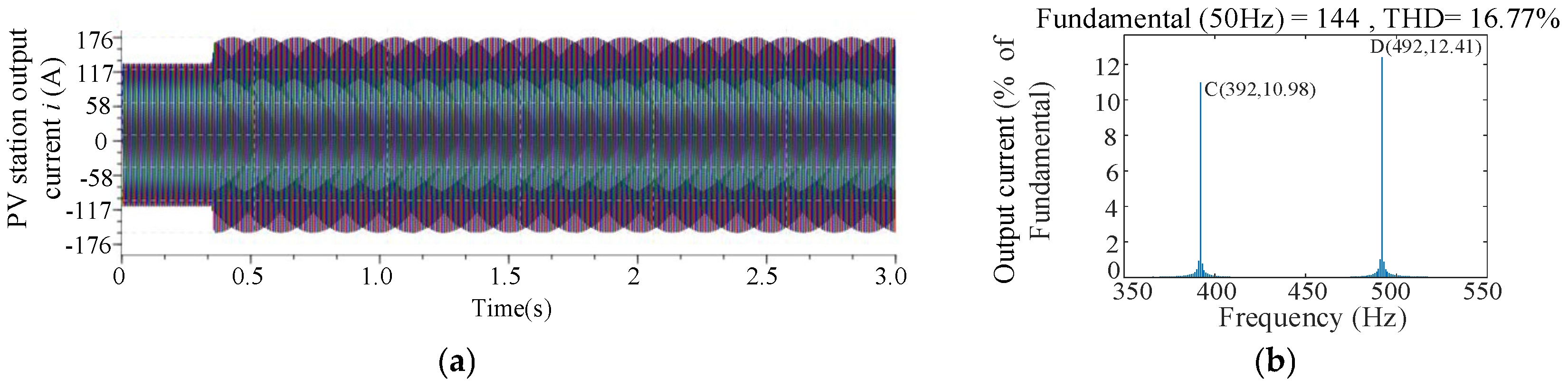

Figure 14. The figure reveals that at 492 Hz, the impedance magnitude difference is zero and the phase difference reaches 181° between the PV station and the grid. This condition satisfies the criterion for oscillatory instability in the impedance-based analysis method. These findings are corroborated by the operational results from the HIL experimental platform, as evidenced in

Figure 15. Under this new set of parameters, the system becomes unstable, and the instability occurs precisely at 492 Hz. Therefore, the results obtained from the proposed measurement method are in close agreement with the experimental results, which validates the effectiveness of the proposed approach. Furthermore, the same frequency previously identified as having the higher instability risk in

Figure 12. This result indirectly confirms the accuracy and effectiveness of the impedance measurement method presented in this paper.

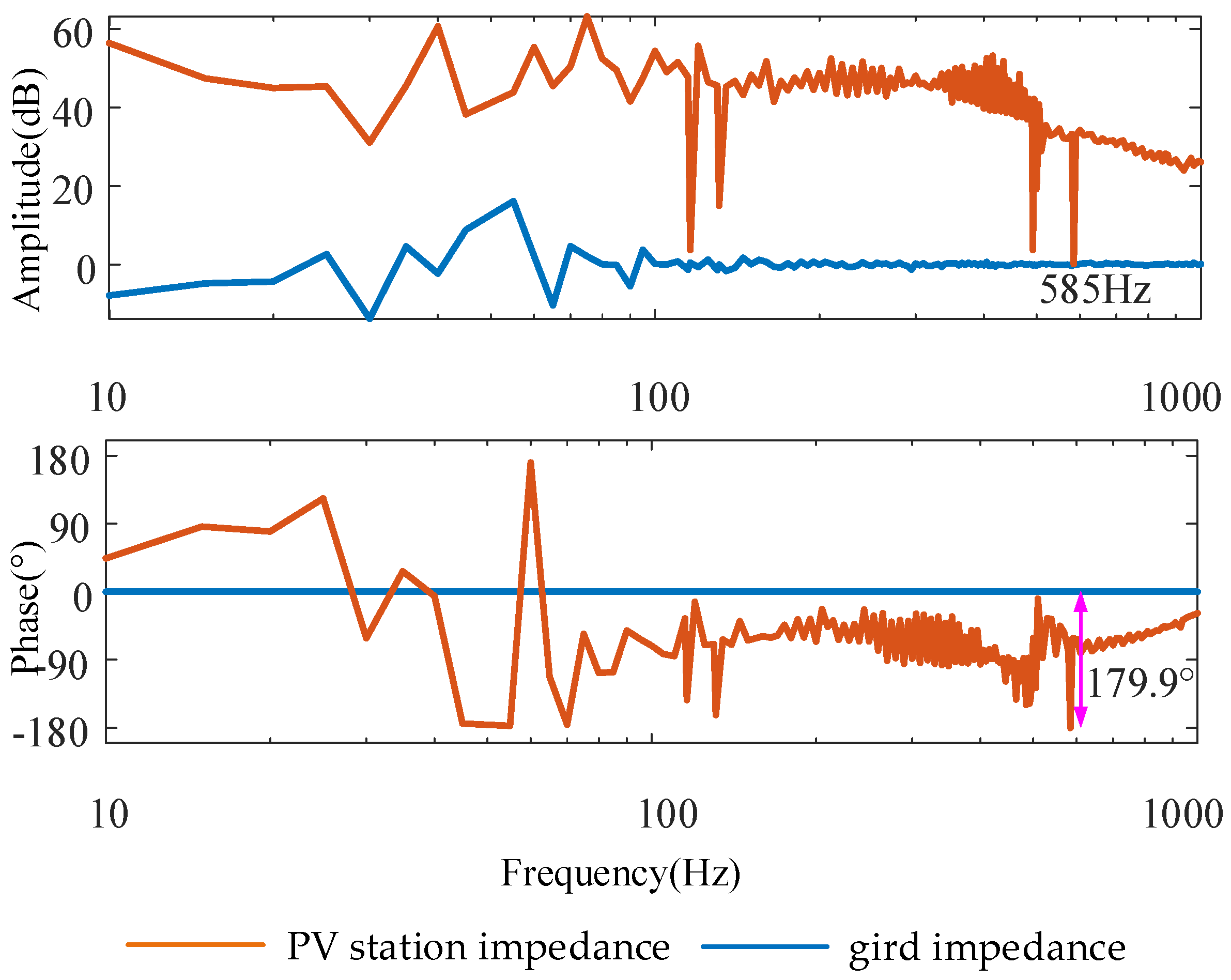

Subsequently, in case 2, the controller parameters of the PV converter are modified: the voltage outer loop gains

kp_Udc and

ki_Udc are adjusted to 25 and 5, and the current inner loop gains

kp_I and

ki_I are adjusted to 0.19 and 0.5. The obtained impedance of the renewable energy converter and the power grid are shown in

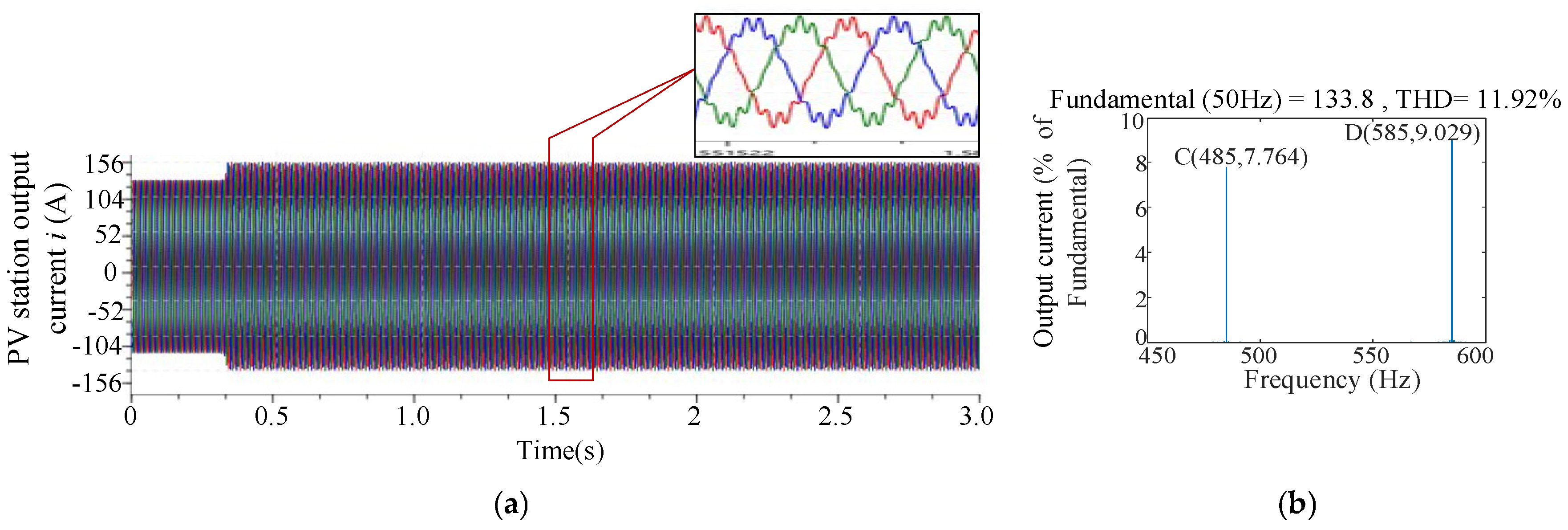

Figure 16. The figure reveals that at 585 Hz, the impedance magnitude difference is zero and the phase difference reaches 179.9° between the PV station and the grid. This condition satisfies the criterion for oscillatory instability in the impedance-based analysis method. These findings are corroborated by the operational results from the HIL experimental platform, as evidenced in

Figure 17. Under this new set of parameters, the system becomes unstable, and the instability occurs precisely at 585 Hz. Therefore, the results obtained from the proposed measurement method are in close agreement with the experimental results, which validates the effectiveness of the proposed approach. Furthermore, the same frequency previously identified as having the higher instability risk in

Figure 12. This result indirectly confirms the accuracy and effectiveness of the impedance measurement method presented in this paper.

5. Discussion

The effectiveness of the proposed method has been validated on a HIL experimental platform. This section focuses on discussing the advantages and challenges of the proposed method in practical engineering scenarios, aiming to further enhance its engineering value and expand its application fields.

The implementation scheme of the impedance measurement method proposed in this paper is largely consistent between the hardware-in-the-loop platform and practical engineering applications. However, in real-world projects, it is crucial to ensure proper safety isolation and connection of the impedance measurement device. Furthermore, the proposed method offers significant advantages in terms of both scalability and cost-effectiveness.

In terms of scalability, the CHB topology can be readily adapted to various application scenarios with different voltage levels and power capacities by increasing the number of series-connected H-bridge power modules. Furthermore, the device can reshape the system impedance by adjusting its control parameters, thereby enabling wide-band oscillation suppression. In terms of cost-effectiveness, hardware components such as power modules, sensors, controllers, and cooling systems can be largely reused. The primary development cost is concentrated at the software level. Furthermore, the integration of multiple functions into a single device reduces space requirements and associated costs. Consequently, the impedance measurement device based on the proposed method offers promising application prospects.

The method proposed in this paper is theoretically feasible. However, practical engineering applications of the impedance measurement device remain scarce, resulting in a lack of relevant empirical references. Furthermore, environmental factors such as background harmonics may adversely affect the impedance measurement results [

24], potentially leading to inaccuracies at frequency points that are integer multiples of the fundamental frequency. Future work is planned to develop the measurement device, conduct impedance tests on practical renewable energy stations, and subsequently refine the impedance measurement method based on the results obtained.