Zone-AGF: An O-RAN-Based Local Breakout and Handover Mechanism for Non-5G Capable Devices in Private 5G Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

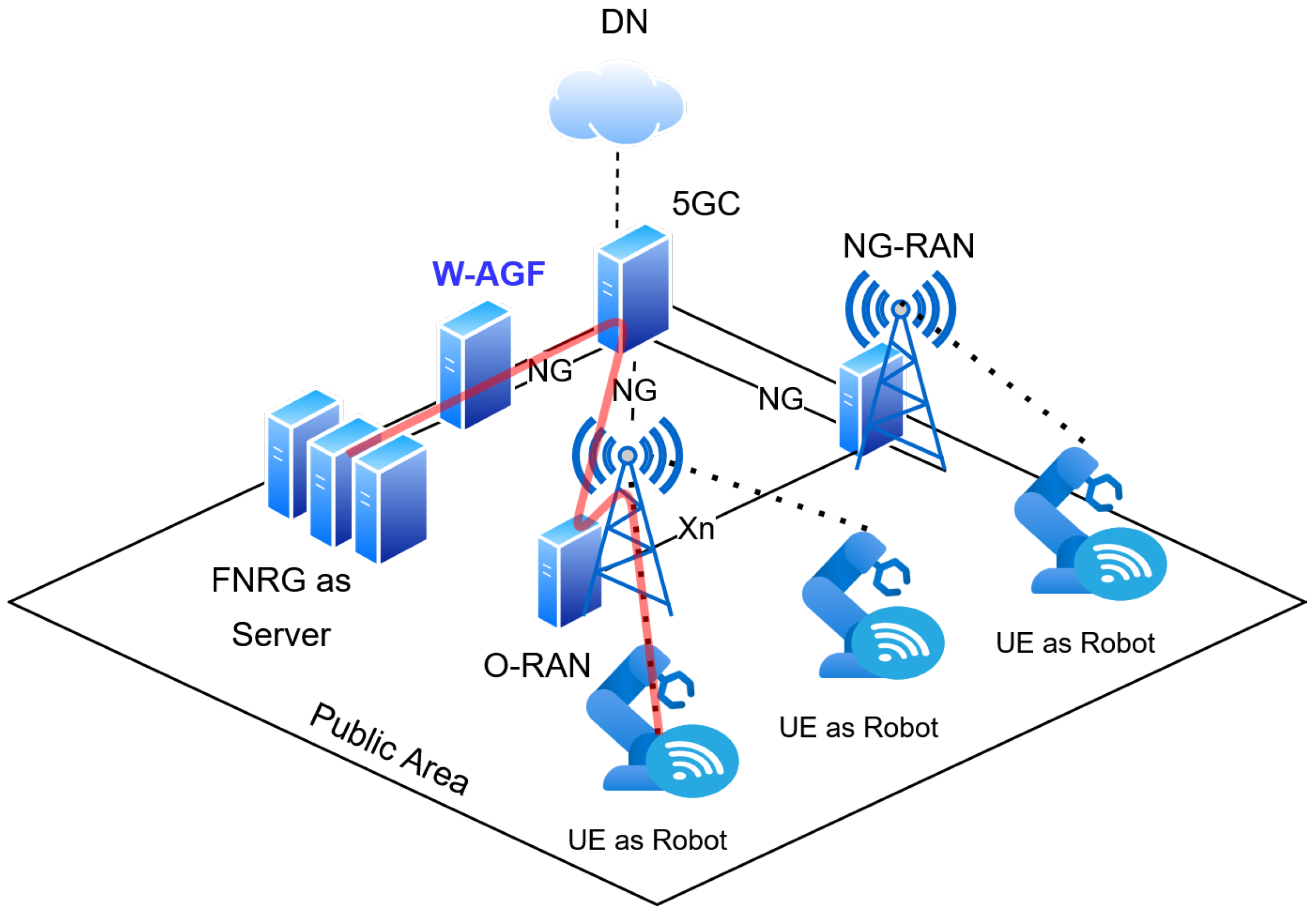

1.1. Motivation

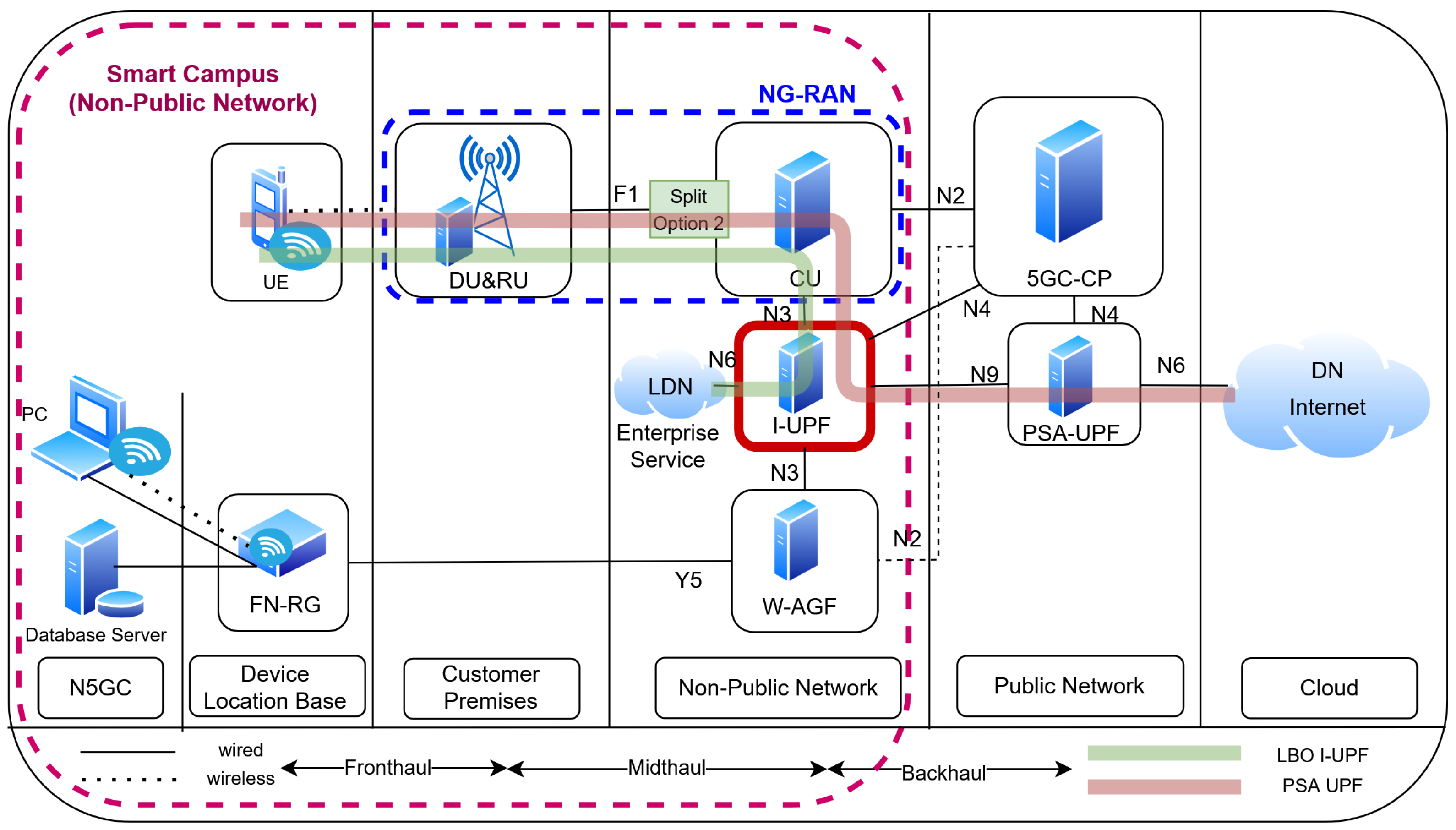

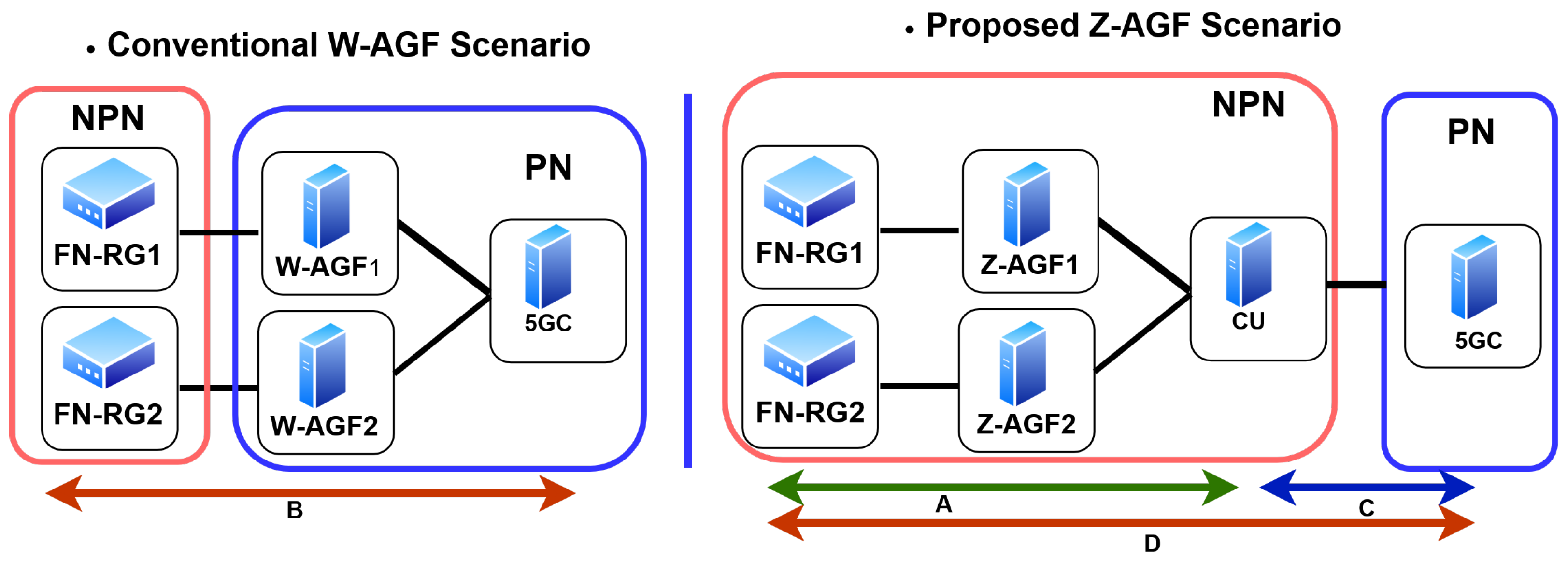

1.2. Proposed Solution

1.3. Key Contributions

- Novel Z-AGF architecture for seamless N5GC connectivity: We introduce a Zone-Access Gateway Function (Z-AGF) as a CU-coordinated control-plane entity that complements existing CU-O-RAN and W-AGF components to enable session continuity and mobility for N5GC and fixed devices in private 5G environments.

- Practical integration and implementation: We demonstrate the integration of Z-AGF within a private smart-campus deployment using interoperable open-source platforms (Open5GS and UERANSIM), confirming feasibility and alignment with standardized O-RAN/3GPP interfaces.

- Latency-aware mobility enhancement: We design control- and user-plane mechanisms that apply localized breakout and QoS-aware routing at the access edge to support reliable and low-latency communication for delay-sensitive N5GC traffic.

- Experimental validation against a W-AGF baseline: We evaluate Z-AGF performance in terms of handover latency, packet loss, and session continuity, demonstrating consistent gains over a conventional W-AGF/UPF deployment in the examined smart-campus scenario.

2. Related Work

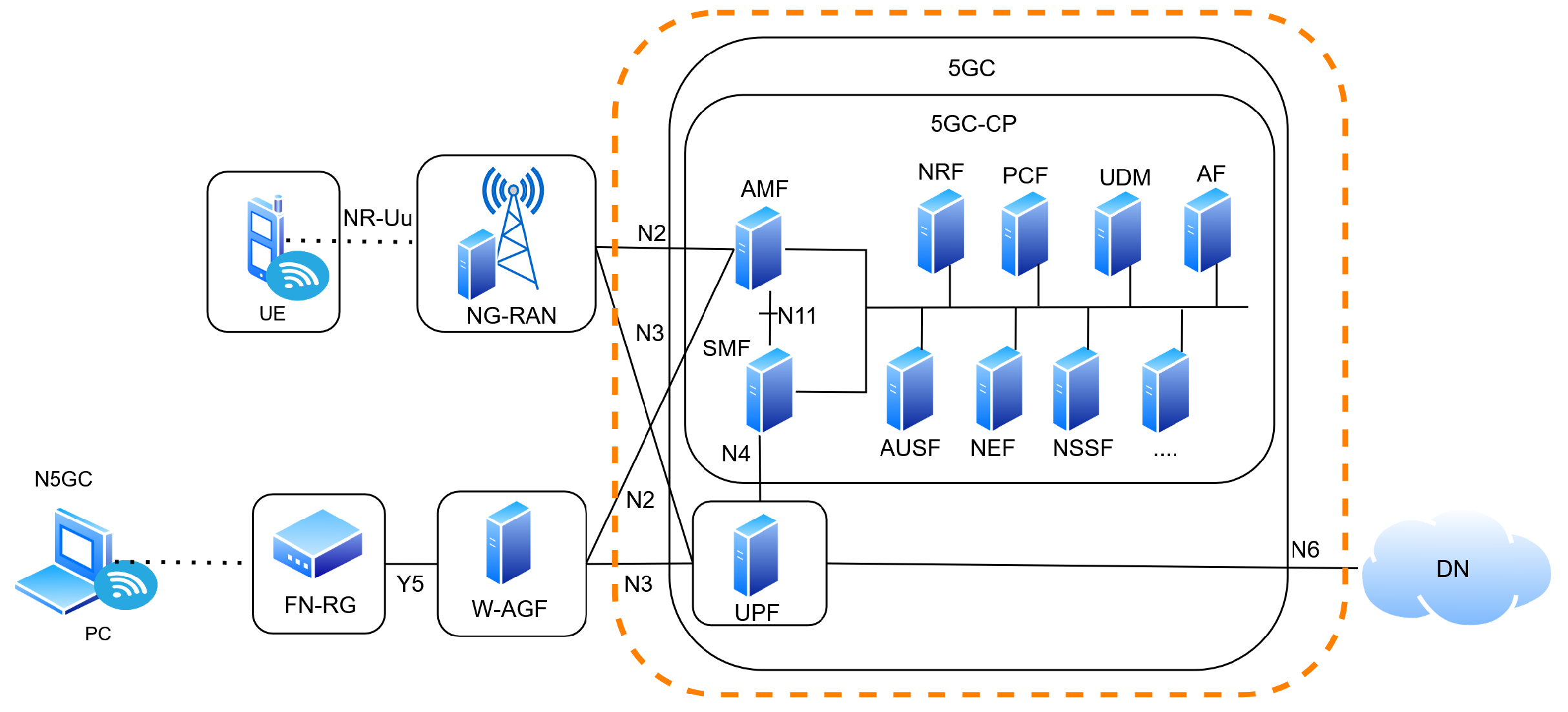

2.1. 5G System with Access Gateway Function Overview

2.1.1. 5G Core Network Architecture

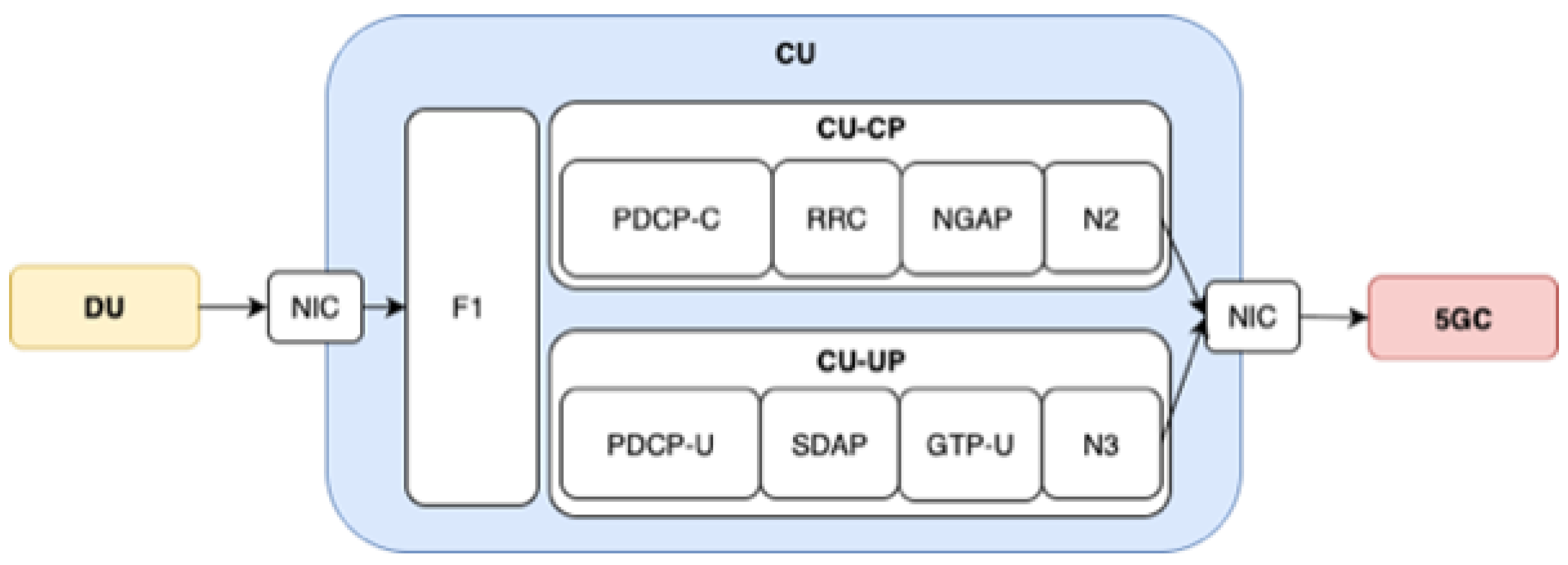

2.1.2. Central Unit (CU) in NG-RAN

2.1.3. Non-Public Network (NPN) in 5G Systems

2.2. Wireless–Wireline Convergence (WWC)

2.3. Wireline Access Network

- (1)

- Unified Authentication, enabling fixed broadband subscribers to use 5G credentials under a common identity management system [20];

- (2)

- Converged QoS Enforcement, ensuring consistent and predictable performance across wireline and wireless links [16]; and

- (3)

- Service Continuity, through session anchoring and context transfer mechanisms within the 5GC.By incorporating wireline access into the Wireless 5th-Generation Access Network framework, operators can reuse the existing broadband infrastructure to deliver true FMC and unified services via a single 5G Core architecture, thereby enhancing efficiency and accelerating 5G service convergence [11].

2.4. Wireline Access Gateway Function (W-AGF)

2.4.1. RG Registration Categories Based on SUPI Location and Access Type

- 5G-RG (FWA)—SUPI in RG with Wireless Access

- 5N-RG (Hybrid)—SUPI in RG with Wireline Backhaul

- 5N-RG (Wireline)—SUPI in RG with Fully Fixed Access

- FN-RG —SUPI in W-AGF (Proxy Model)

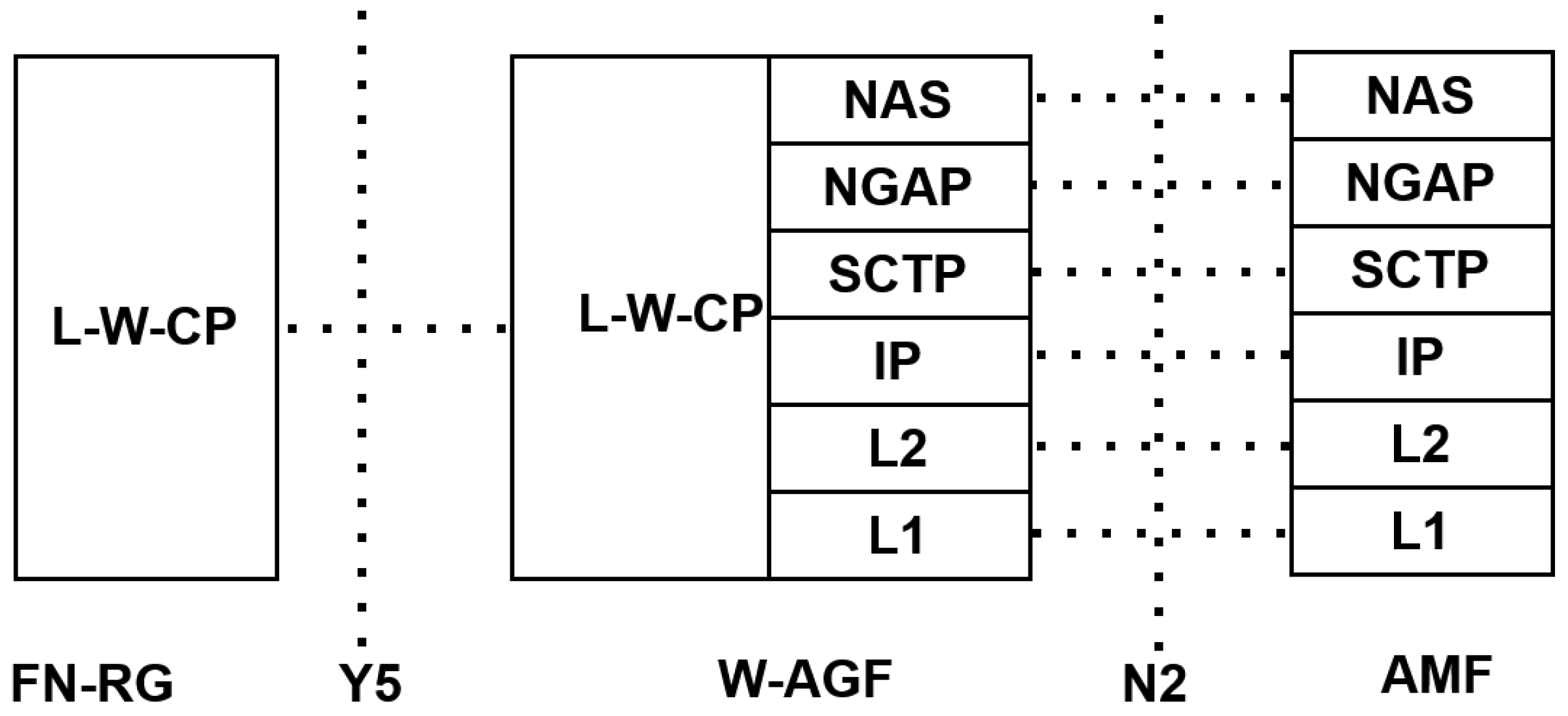

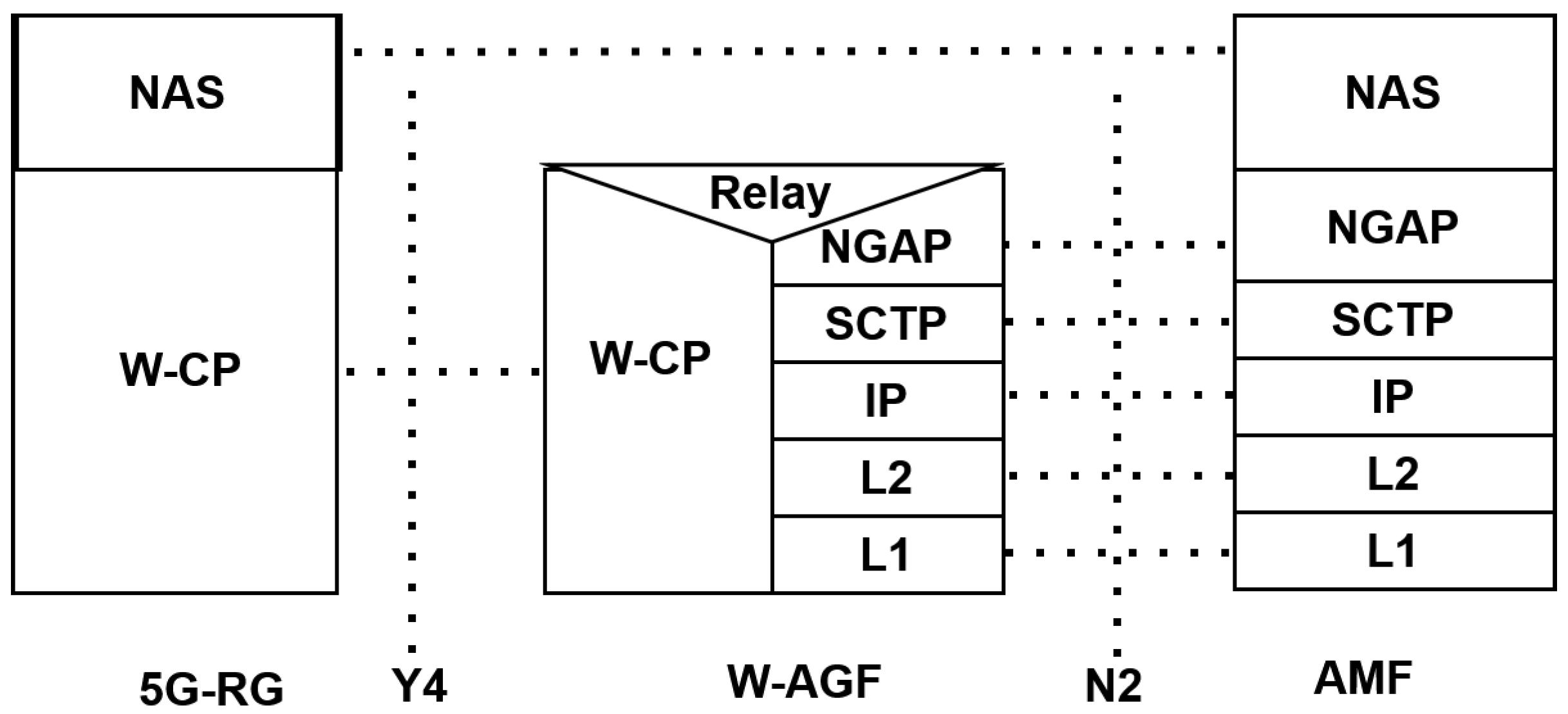

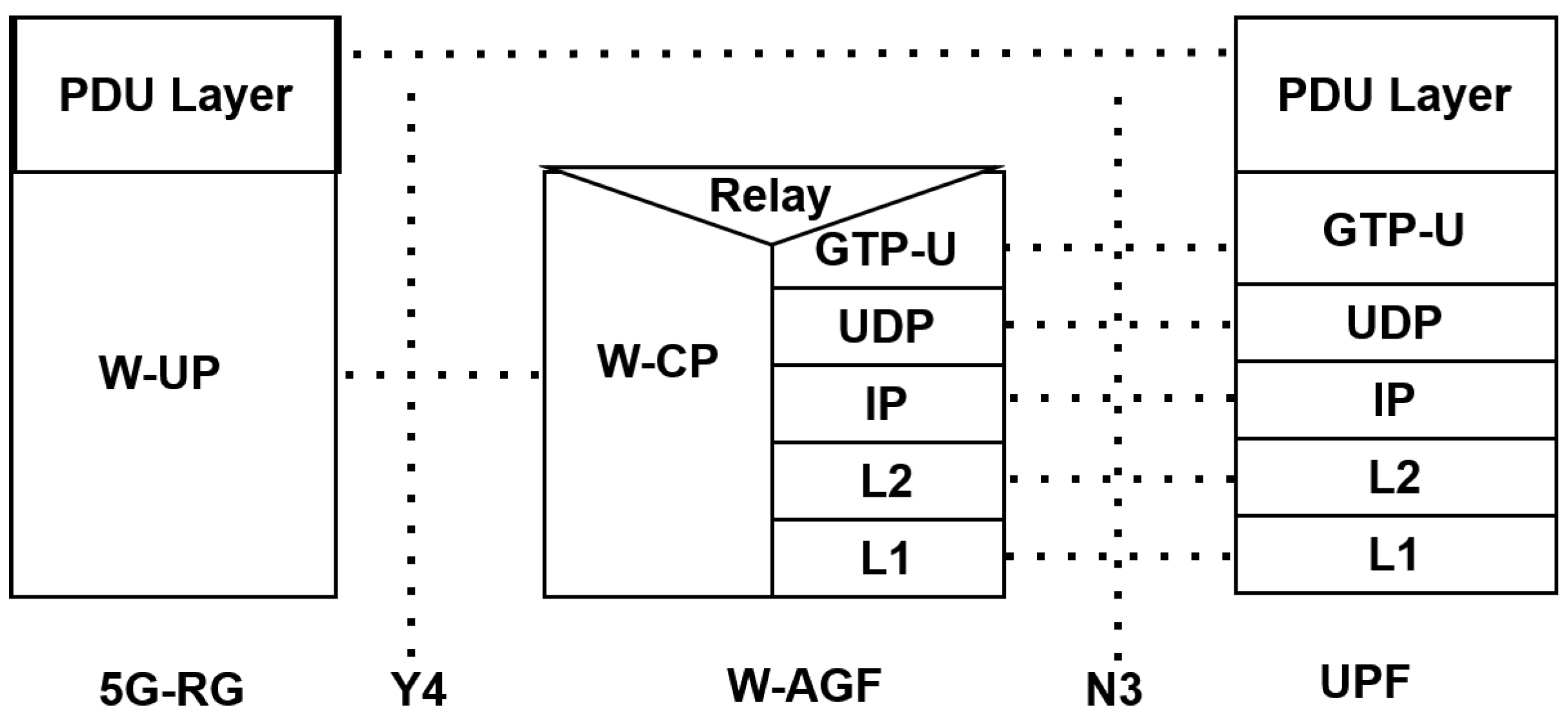

2.4.2. W-AGF Protocol Architecture and Functional Interworking

- FN-RG Protocol Stack

- 5G-RG Protocol Stack

2.4.3. Possible Existing Technology: I-UPF Integration

2.5. CU–O-RAN-Based Mobility Management

2.6. Local Breakout (LBO) and URLLC Integration

2.7. Access-Agnostic 5GC Convergence Alternatives

2.7.1. AMF-Based Convergence Sublayer

2.7.2. Common AN/CN Interface Definition

2.7.3. Convergence NAS Protocol on UE and CN

2.8. Research Gap

3. Proposed Approach: Zone Access Gateway Function (Z-AGF)

3.1. Architectural Overview

3.2. Interface Legitimacy and F1AP Adaptation in Z-AGF

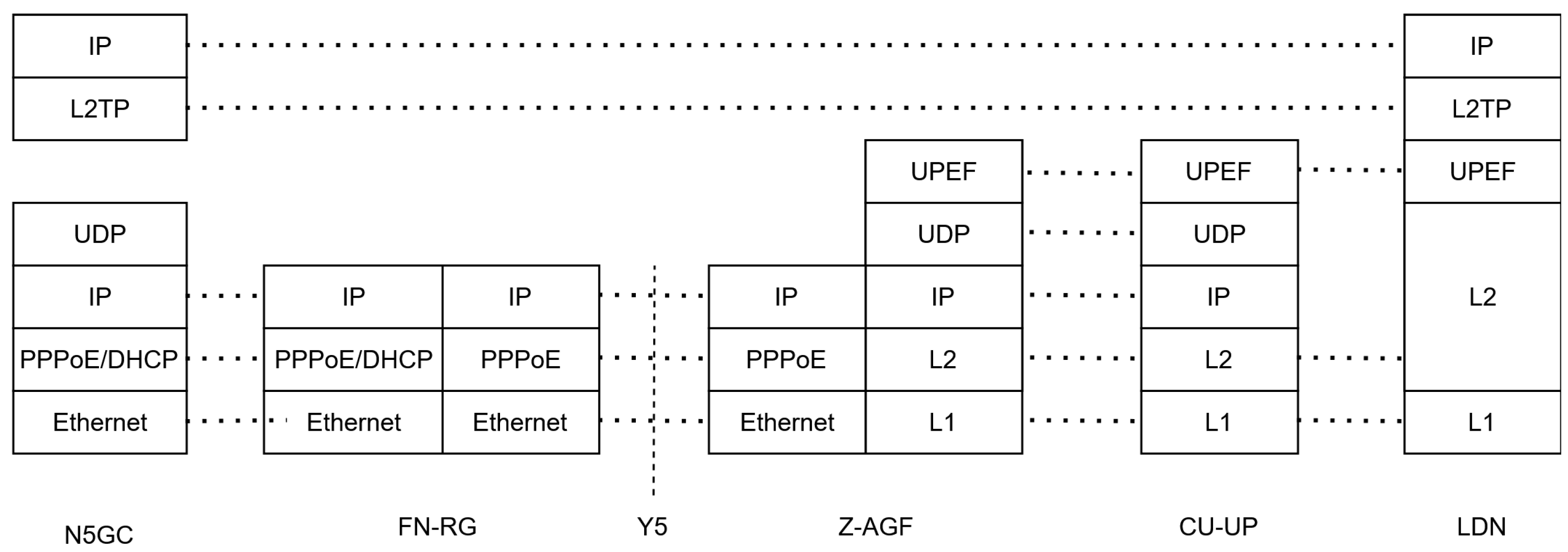

3.3. Protocol Stack Design

3.3.1. Control Plane Inter-Working

3.3.2. User-Plane Operations

3.3.3. Local Breakout Mechanism

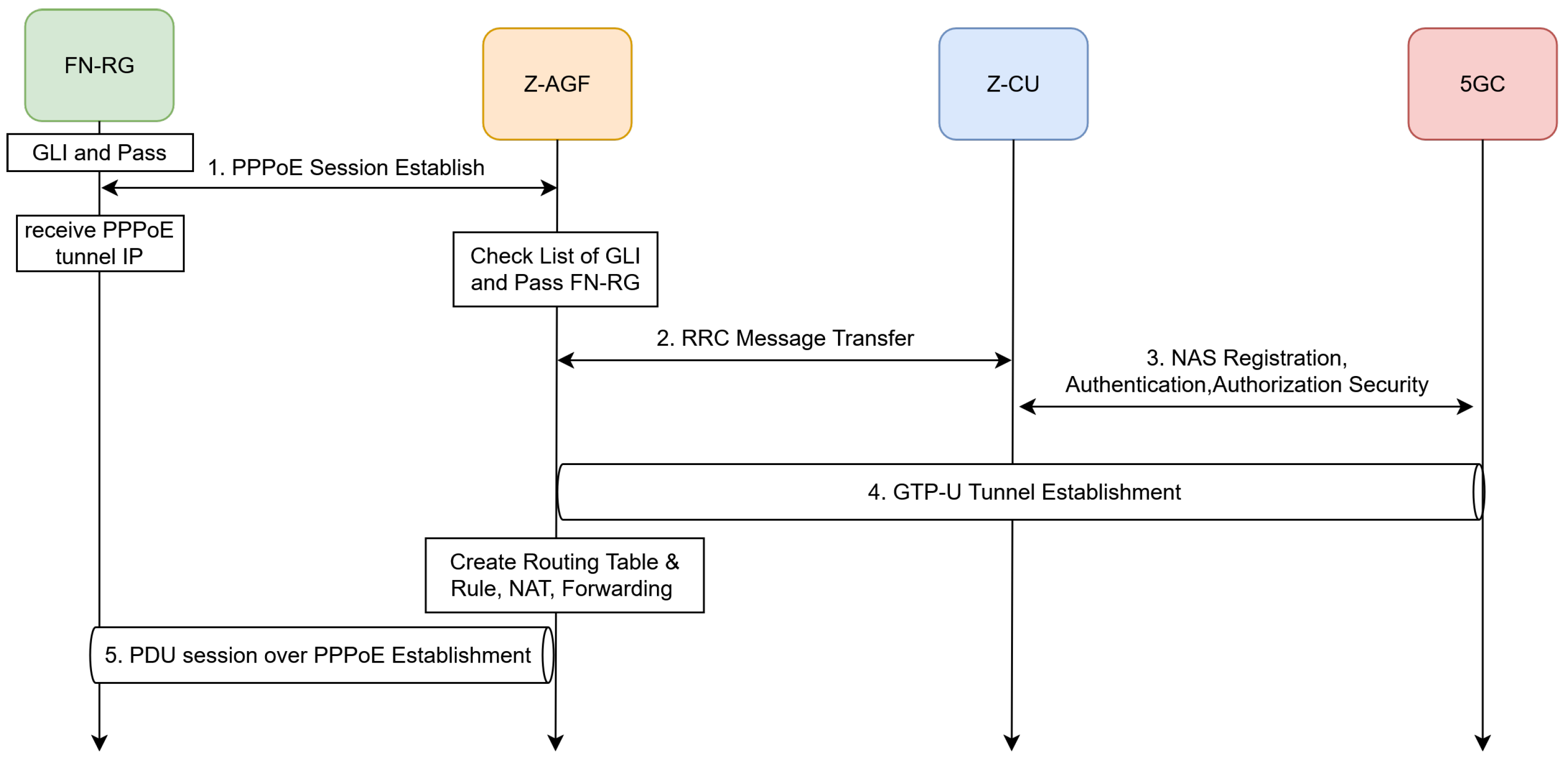

3.4. Z-AGF Call Flow Procedures

3.4.1. PDU Session Establishment

- FN-RG requests a PPPoE session from the ISP (Z-AGF): its broadcasts a PPPoE Discovery Procedure to the Z-AGF. A PPPoE session was established, and the Z-AGF executed the control procedures for FN-RG registration and session setup.

- Registration and Authentication: The Z-AGF handles the registration and authentication procedure of the FN-RG to the 5G Core Network and sends it through an RRC message transfer.

- PDU Session Acceptance: The Z-AGF receives the PDU Session Establishment Accept message and establishes the corresponding GTP-U tunnel. At this stage, Z-AGF manages the FN-RG’s user plane.

- Tunnel Creation: The tunnel to the Z-AGF was created and is listed in the routing table.

- PDU Session Completion: The PDU session of the FN-RG is successfully established.

3.4.2. Local Breakout (LBO) Procedures

- DHCP/PPPoE Connection: A DHCP/PPPoE connection is established between the N5GC device and FN-RG.

- SCCRQ Initiation: The N5GC device sends an SCCRQ message.

- UPEF Encapsulation: The Z-AGF encapsulates the N5GC SCCRQ within the UPEF tunnel.

- UPEF Message Transfer: The encapsulated message is forwarded through the UPEF tunnel.

- CU Decapsulation: The CU decapsulates the received UPEF message.

- Record Z-AGF Information in Z-CU: The Z-CU records Z-AGF information as follows:

- Z-AGF ID = 1

- Z-CU (Z-AGF) IP = 10.50.0.88

- CU Message Handling: The CU transfers the SCCRQ message to the target entity.

- Tunnel and Session Validation: The CU verifies the N5GC device’s tunnel ID and session ID.

- L2TP Procedure: The CU performs L2TP configuration for the N5GC device.

- Record Session Parameters:N5GC Device Tunnel ID (stored)

- Record Session Parameters:N5GC Device Session ID (stored)

- PPP Exchange: PPP negotiation is performed between the N5GC device and the Z-AGF.

- IPCP Configuration: The N5GC device receives a PPP IPCP Configuration ACK message.

- Record N5GC Device Information:

- N5GC ID = 1

- Z-CU Z-AGF ID = 1

- N5GC Z-AGF IP Tunnel = 10.50.0.88

- CU Encapsulation: The CU encapsulates traffic using F1-U.

- F1-U Message Transfer: The CU transfers the encapsulated F1-U message.

- Z-AGF Decapsulation: The Z-AGF decapsulates the F1-U traffic, carrying the LBO payload.

- Final Configuration: The N5GC device receives PPP IPCP Configuration ACK confirmation.

- LBO Tunnel Creation: The LBO tunnel for the N5GC device is successfully created.

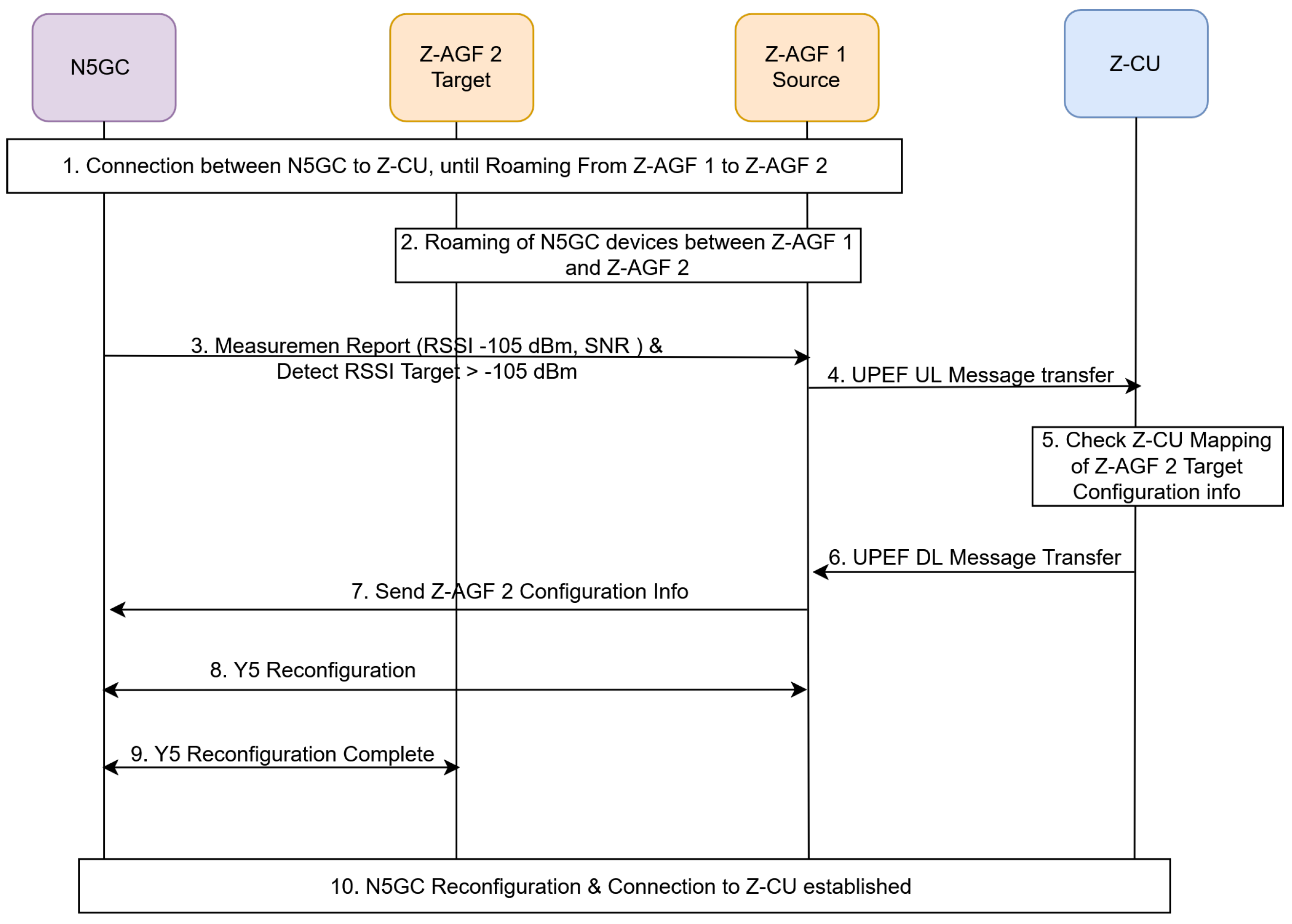

3.4.3. Handover Procedures

- Connection Establishment: The N5GC device establishes an active connection with the current Z-AGF.

- Roaming Event: The N5GC device initiates a handover, roaming from Z-AGF1 to Z-AGF2.

- Tunnel Detection: The serving Z-AGF detects a new tunnel request from the N5GC device.

- F1AP UL Message Transfer: The Z-AGF sends an F1AP uplink message to initiate a tunnel update request.

- Tunnel Update Request: The request is sent to the Z-CU for coordination.

- Tunnel Information Update: The Z-CU updates the tunnel parameters as follows in Table 1:

- Tunnel Update Response: The Z-CU sends the tunnel update response to confirm the successful modification.

- F1AP DL Message Transfer: The CU transmits a downlink F1AP message carrying the tunnel update response.

- Y5 Reconfiguration (Target Tunnel Setup): The Y5 interface was reconfigured to establish the tunnel toward the target Z-AGF.

- Tunnel Response Delivery: The CU sends the tunnel update response to the target Z-AGF.

- Target Z-AGF Tunnel Detection: The target Z-AGF detects and activates a new N5GC tunnel request.

- Y5 Reconfiguration Completion: The system completes Y5 reconfiguration by breaking the tunnel associated with the source Z-AGF.

- Connection to LNS Established: A new connection to the LNS is established, completing the inter-Z-AGF handover process.

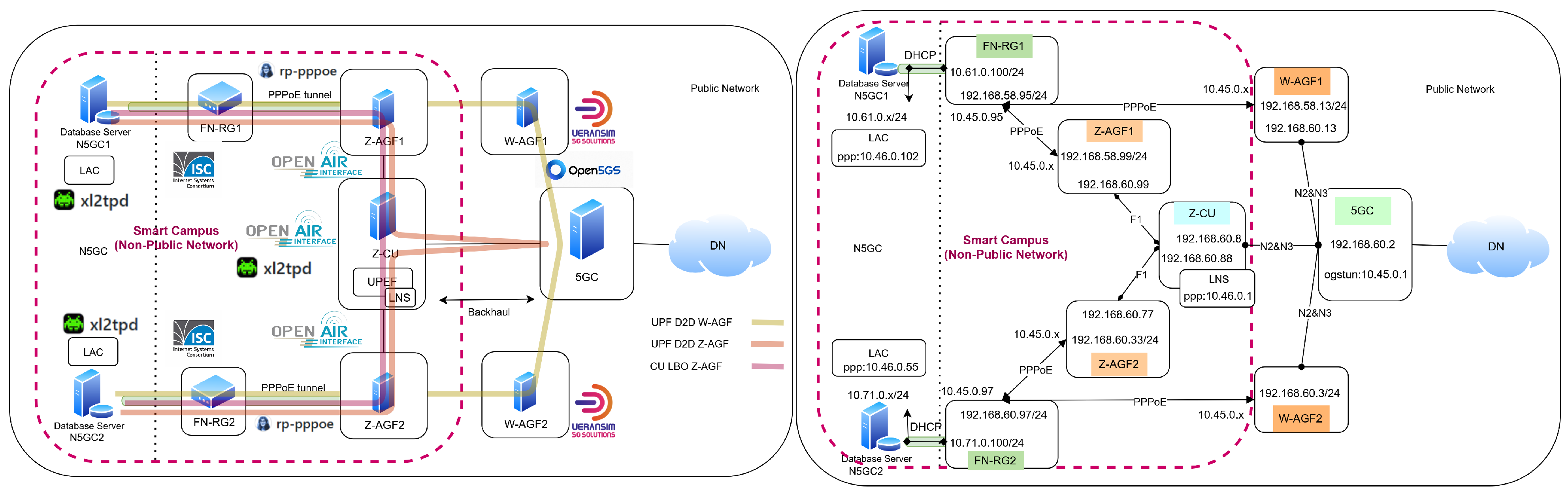

4. Implementation and Experimental Setup

4.1. Prototype Experimental Environment

- 5G Core Network: Implemented using the Open5GS platform [22,34], comprising Access and Mobility Management Function (AMF), Session Management Function (SMF), and User-Plane Function (UPF) [35]. These modules were deployed on Ubuntu 22.04 (Jammy) with kernel version 5.15.0, providing reference 5GC functions for the control and user-plane operations.

- Wi-Fi Access and Gateway Layer: The Wireless Access Gateway Functions (W-AGFs) were virtualized and connected to departmental Wi-Fi access points simulated via host-based bridges. Each W-AGF instance interacts with the Z-AGF through a lightweight control channel for session synchronization and mobility coordination. The W-AGF was realized through the UERANSIM [36] framework, operating as a proxy UE over the N2 and N3 interfaces toward the 5GC, and integrated with an rp-pppoe [37] server for PPPoE-based aggregation.

- Z-AGF Module: Implemented as a middleware between the W-AGFs and the Centralized Unit (CU), the Z-AGF was developed in Python 3.13 (control-plane) and C++23 (user-plane). It incorporates three submodules: Mobility Management Module (MMM), Session Persistence Engine (SPE), and QoS Policy Control Unit (QPCU). Z-AGF leverages the OpenAirInterface (OAI) [34,38] stack to support F1 interface signaling and proxy UE interconnection with the CU. An rp-pppoe server provides tunneling support for subscriber sessions through PPPoE encapsulation.

- Centralized Unit (CU): The CU–O-RAN instance was emulated using the OpenAirInterface CU implementation, which manages the F1 Application Protocol (F1AP) signaling and coordinates Z-AGF functions during handovers and QoS updates. The CU interfaces with the UPF for packet forwarding and session management across distributed AGFs.

- Fixed network residential gateway (FN-RGs): Each FN-RG node was implemented using the ISC-DHCP server [39] for dynamic IP allocation to end devices, complemented by xl2tpd [40] for Layer-2 tunneling to local access networks. The FN-RGs emulate customer premises equipment (CPE) devices that act as tunnel endpoints for PPPoE sessions connected to AGFs.

- Database and Analytics: A MongoDB instance stores session contexts, device identifiers, and latency statistics collected during the post-analysis experiments [41].

- UE and Traffic Simulation: The UERANSIM toolkit emulates 5G user equipment (UE) and generates UDP/TCP traffic flows. For N5GC devices, Wi-Fi clients were emulated via virtual interfaces connected through departmental W-AGFs.

4.2. Experimental Configuration and Results

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Evaluation Methodology

- Scenario 1: Standard W-AGF(baseline), mobility and session management handled solely by W-AGF/I-UPF.

- Scenario 2: Z-AGF Enabled, Mobility jointly managed by the Z-AGF and CU using cached session contexts.

- Scenario 3: Z-AGF combined with LBO, mobility and localized data routing for intra-campus communication.

5.2. Handover Latency Analysis

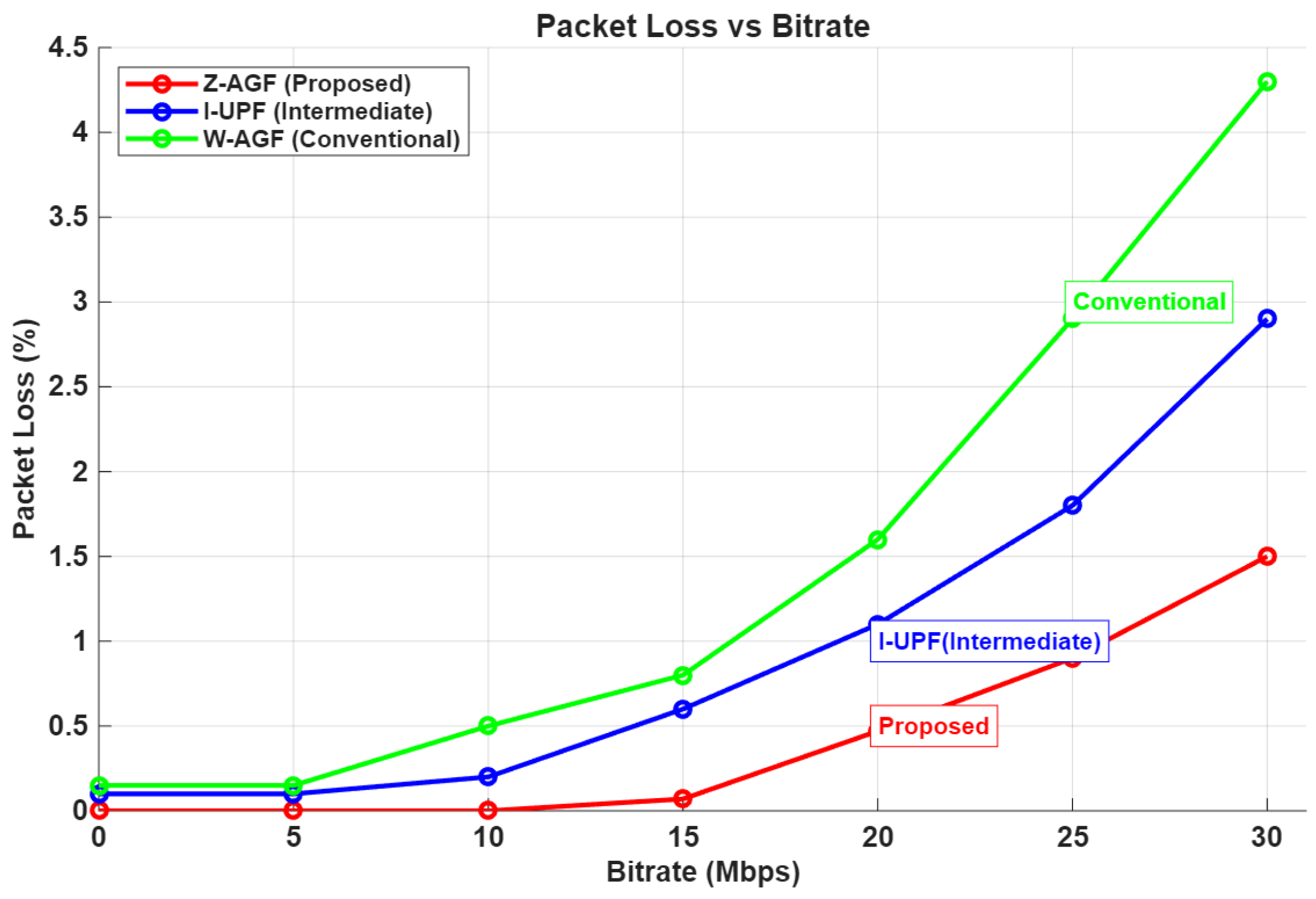

5.3. Packet Loss and Session Continuity

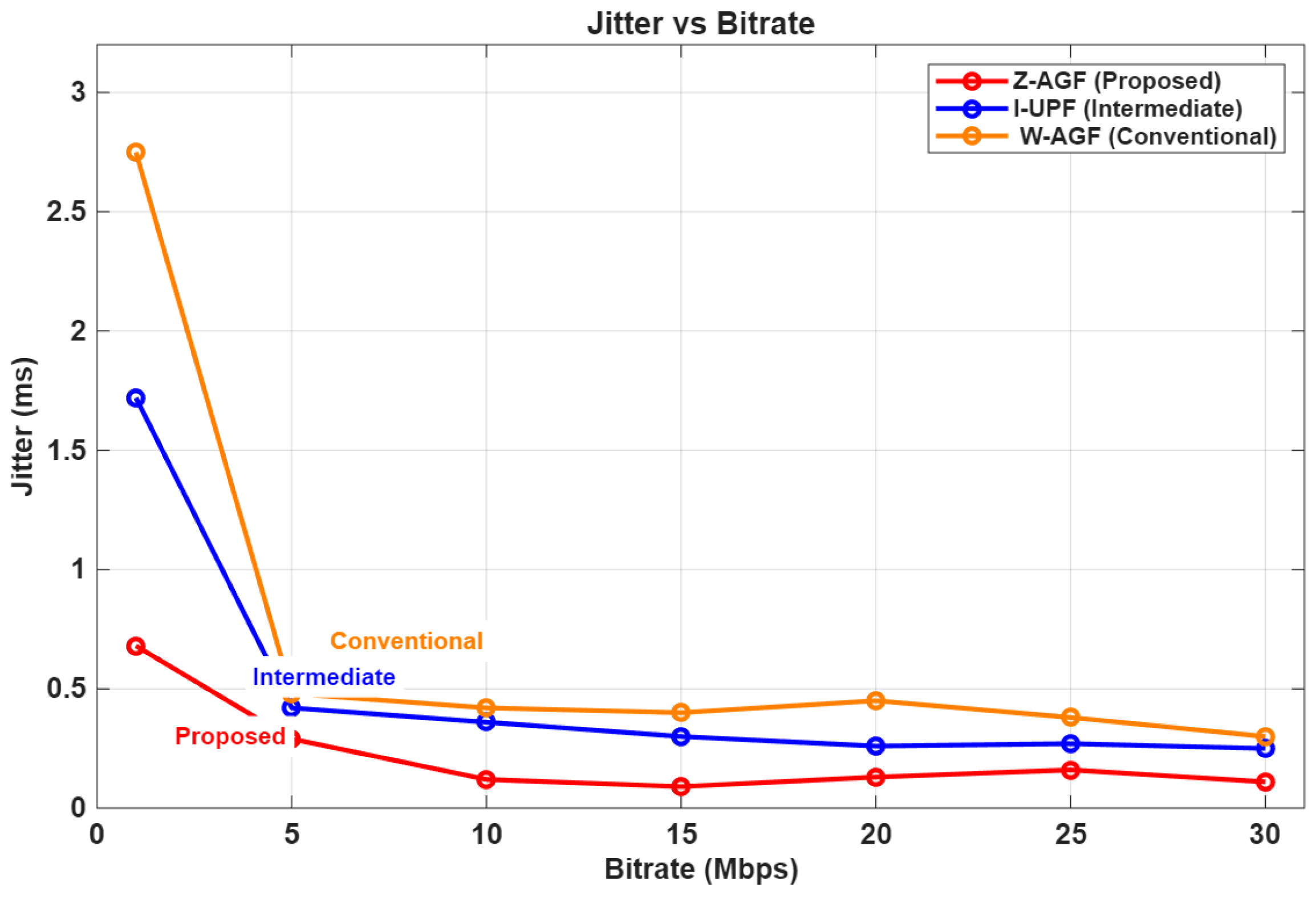

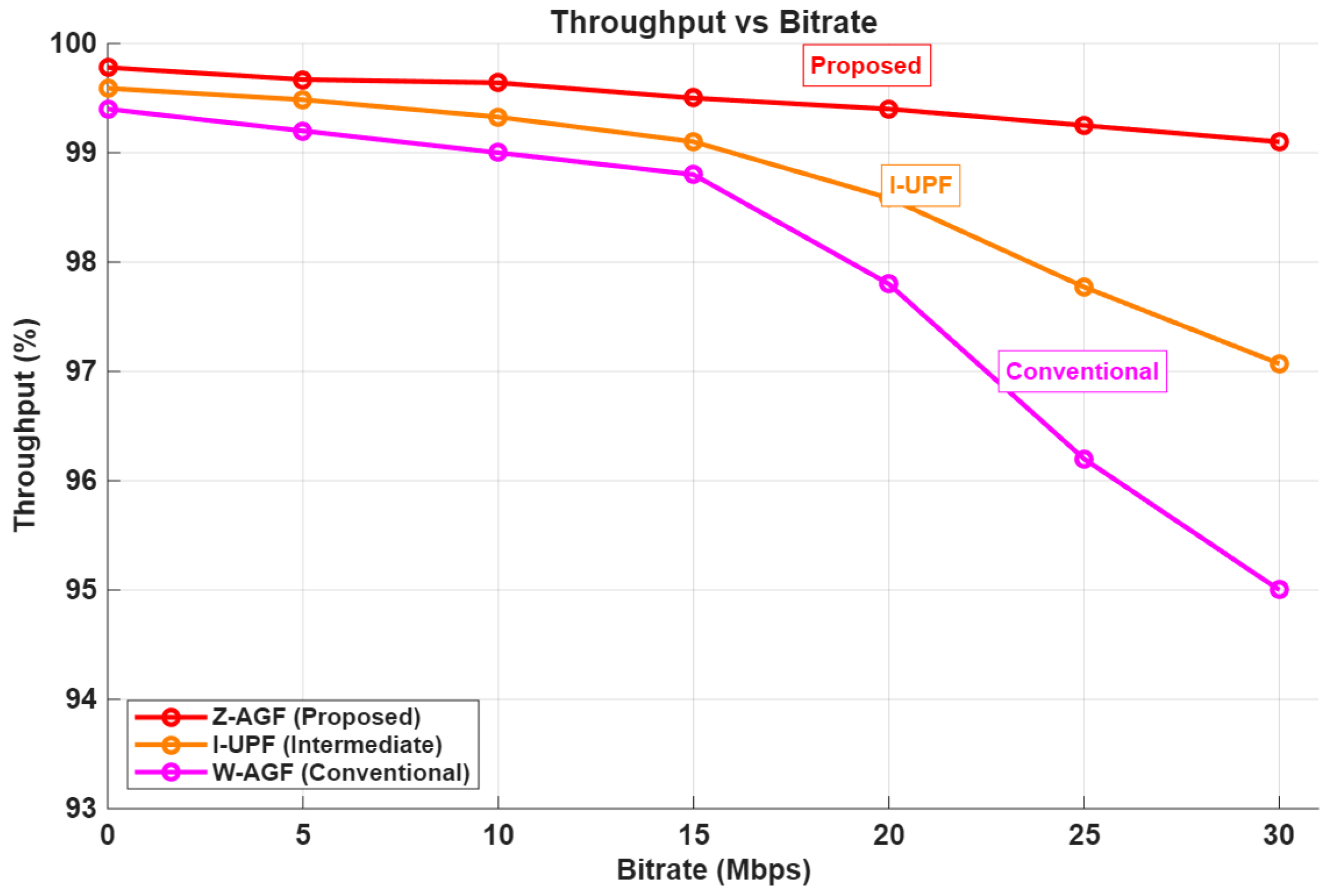

5.4. Local Breakout and QoS Performance

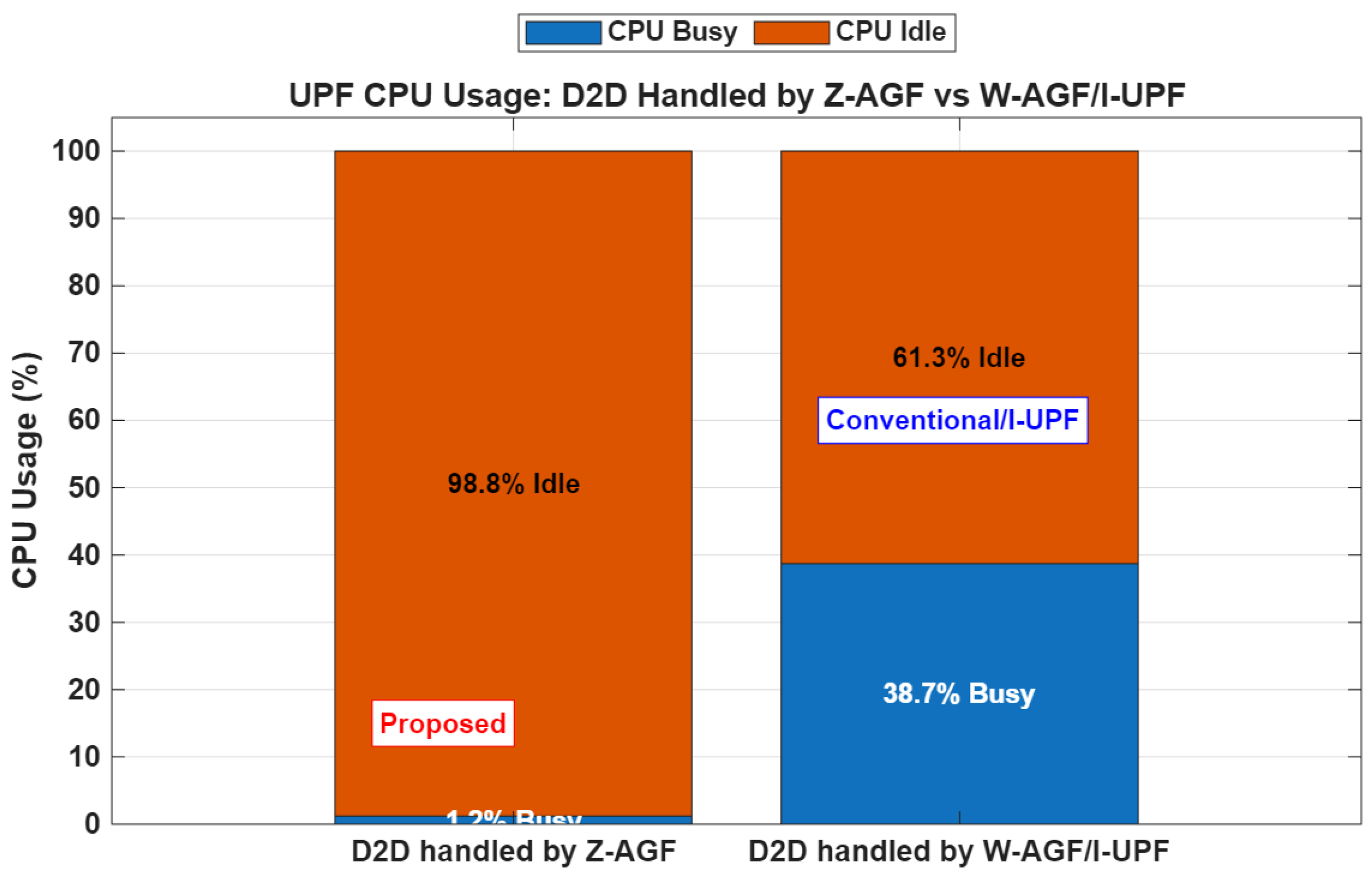

5.5. Functional and Resource Efficiency

5.6. Security, Trust, and Policy Governance in LBO

5.7. Key Findings

- Up to 45.6% latency reduction during handovers.

- 69% packet loss reduction and 98.1% session continuity.

- 85.6% reduction of RTT for local communications under LBO.

- 98.8% UPF idle rate, validating the effective local offloading.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3GPP | Third Generation Partnership Project |

| 5GC|5GS | 5th Generation Core|5th Generation System |

| 5G-RG | 5th Generation Residential Gateway |

| AGF|AF | Access Gateway Function|Application Function |

| AS|AMF | Access Stratum|Access and Mobility Management Function |

| ATSSS | Access Traffic Steering, Switching and Splitting |

| AUN3 | Authenticable Non-3GPP Device |

| AUSF | Authentication Server Function |

| BBF | Broadband Forum |

| BBM | Break-Before-Make |

| CDF | Cumulative Distribution Function |

| CHAP | Challenge-Handshake Authentication Protocol |

| CP | Control Plane |

| CPE | Customer Premises Equipment |

| CU | Centralized Unit |

| D2D | Device-to-Device |

| DHCP | Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol |

| DL | Down Link |

| DU | Distributed Unit |

| DN | Data Network |

| DOCSIS | Data Over Cable Systems Interface Specifications |

| DSL | Digital Subscriber Line |

| F1AP | F1 Application Protocol |

| FN-RG | Fixed Network Residential Gateway |

| FMC | Fixed-Mobile Convergence |

| FWA | Fixed Wireless Access |

| GPON | Gigabit Passive Optical Network |

| GTP-U | GPRS Tunneling Protocol - User Plane |

| GLI | Global Line Identifier |

| gNB | Next-Generation Node B |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| IP/IPCP | Internet Protocol/IP Control Protocol |

| IPV6CP | IPV6 Control Protocol |

| IPoE | Internet Protocol over Ethernet |

| I-UPF | Intermediate-UPF |

| ISP | Internet Service Provider |

| MAC | Media Access Control |

| MBB | Make-Before-Break |

| N5GC | Non-5G Capable |

| NAS | Non-Access Stratum |

| NAUN3 | Non-Authenticable Non-3GPP Device |

| NEF | Network Exposure Function |

| NF | Network Function |

| NGAP | Next-Generation Application Protocol |

| NG-RAN | Next-Generation Radio Access Network |

| NIC | Network Interface Card |

| NPN | Non-Public Network |

| NR | New Radio |

| NRF | Network Slice Selection Function |

| NSSF | Network Exposure Function |

| L2TP | Layer 2 Tunneling Protocol |

| LAC | L2TP Access Concentrator |

| LBO | Local Breakout |

| LCP | Link Control Protocol |

| LDN | Local Data Network |

| LNS | L2TP Network Server |

| L-W-CP/UP | Legacy Wireline Access Control/User Plane Protocol |

| PCF | Policy Control Function |

| PDU | Packet Data Unit |

| PN | Public Network |

| PNI-NPN | Public Network Integrated NPN |

| PPP | Point-to-Point Protocol |

| PPPoE | Point-to-Point Protocol over Ethernet |

| PDCP-C | Packet Data Convergence Protocol - Control |

| PDCP-U | Packet Data Convergence Protocol - User |

| PHY | Physical |

| PSA-UPF | PDU Session Anchor - UPF |

| QoS | Quality of Service |

| RAN | Radio Access Network |

| RG | Residential Gateway |

| RLC | Radio Link Control |

| RRC | Radio Resource Control |

| RTT | Round-Trip Time |

| RU | Radio Unit |

| SUPI | Subscription Permanent Identifier |

| SCCRQ | Start-Control-Connection-Request |

| SCTP | Stream Control Transmission Protocol |

| SDAP | Service Data Adaptation Protocol |

| SMF | Session Management Function |

| SNPN | Standalone Non-Public Network |

| UDM | Unified Data Management |

| UDP | User Datagram Protocol |

| UE | User Equipment |

| UP/UL | User Plane/Up Link |

| UPF/UPEF | User Plane Function/User Plane Extension Function |

| W-5GAN | Wireline 5G Access Network |

| W-AGF | Wireline Access Gateway Function |

| W-CP/UP | Wireline Access Control/User Plane Protocol |

| WWC | Wireless Wireline Convergence |

| XGS-PON | 10-Gigabit Symmetric Passive Optical Network |

| Z-AGF | Zone-Access Gateway Function |

| Z-CU | Zone-Centralized Unit |

References

- Trick, U. 5G: An Introduction to the 5th Generation Mobile Networks; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3GPP TS 23.501 v17.9.0; System Architecture for the 5G System (5GS). 3GPP: Valbonne, France, 2024.

- Recommendation Y.3101; Framework of IMT-2020 Network Requirements. ITU-T: Paris, France, 2022.

- Broadband Forum. Access Gateway Function Functional Requirements for 5G; BBF TR-456 Issue 2; Broadband Forum: Fremont, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 3GPP TS 23.316 v17.6.0; Access to the 5G Core via Fixed Access Networks. 3GPP: Valbonne, France, 2023.

- Broadband Forum. Functional Requirements for Hybrid Wireline-Wireless Networks; BBF TR-456 Corrigendum 1; Broadband Forum: Fremont, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- O-RAN.WG1.Architecture-v10.00; O-RAN Architecture Description. O-RAN Alliance: Alfter, Germany, 2023.

- 3GPP TS 23.502 v17.7.0; Procedures for the 5G System (5GS). 3GPP: Valbonne, France, 2024.

- 3GPP TS 29.502 v17.4.0; Session Management Services for the 5G System (SMF). 3GPP: Valbonne, France, 2023.

- Wu, J.; Zhang, L. MEC-Enabled Local Breakout for Low-Latency Services in 5G Networks. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 45678–45689. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Choi, S. Low-Latency Path Optimization in Distributed UPF Architectures. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2023, 20, 1001–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Lee, Y.; Lin, P. Performance Analysis of MEC-Based Local Breakout in Edge 5G. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2023, 61, 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, J. O-RAN-Based Latency Benchmarking for 5G Private Networks. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 99901–99912. [Google Scholar]

- Broadband Forum. WWC Scenarios and Deployment Guidelines; BBF Report; Broadband Forum: Fremont, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Peng, M.; Wang, C. Enhancing Mobility Management in O-RAN through CU Coordination. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2023, 61, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- 3GPP TS 38.401 v17.4.0; NG-RAN Architecture and Functional Split. 3GPP: Valbonne, France, 2023.

- 3GPP TS 38.471 v17.5.0; F1 Application Protocol (F1AP). 3GPP: Valbonne, France, 2023.

- 3GPP TS 38.472 v17.3.0; Signaling Procedures for F1AP. 3GPP: Valbonne, France, 2023.

- 3GPP TS 38.413 v17.7.0; NGAP Protocol for 5GS. 3GPP: Valbonne, France, 2024.

- IETF. 5WE Encapsulation for Fixed Access Integration; RFC 8822; IETF: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, R.; Kumar, P.; Jayakody, D.N.K.; Liyanage, M. A Survey on Security and Privacy of 5G Technologies: Potential Solutions, Recent Advancements, and Future Directions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2020, 22, 196–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Open5GS Project. Open Source 5G Core Network. Available online: https://open5gs.org (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- 3GPP TS 22.261 v17.2.0; Service Requirements for the 5G System (Stage 1). 3GPP: Valbonne, France, 2023.

- Broadband Forum. WWC Progress Report; BBF Technical Update; Broadband Forum: Fremont, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- CableLabs. 5G WWC Core Architecture Overview. Technical Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.cablelabs.com/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Ren, L.; Xu, K. AI-Driven RIC/xApp Integration for Intelligent 6G Networks. IEEE Netw. 2024, 38, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Broadband Forum. WT-456: AGF Requirements for 5G RG/FN-RG; BBF Working Text; Broadband Forum: Fremont, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 3GPP TS 24.502 v17.5.0; Non-Access Stratum (NAS) Protocol for 5GS. 3GPP: Valbonne, France, 2024.

- SCTE–ISBE. Authentication and Key Management for WWC Access. Technical Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.scte.org/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- 3GPP. 5G System Architecture Update; Release 17 Summary; 3GPP: Valbonne, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Foukas, X.; Marina, M.K. 3GPP Core Network Evolution Toward Access-Agnostic 5G Systems. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2022, 40, 1182–1196. [Google Scholar]

- Yousaf, F.; Fontanelli, P.; Iovanna, P.; Costa-Requena, J. A Survey on Converged Fixed-Mobile Access in 5G. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2021, 23, 1954–1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ruffini, M.; Kaminski, N.; Marchetti, N.; Doyle, L.; Marquez-Barja, J.M. Optical and wireless network convergence in 5G systems—An experimental approach. J. Light. Technol. 2017, 35, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, Y. Experimental Evaluation of OAI and Open5GS Integration in Private 5G Networks. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 90900–90911. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.; Huang, P. Optimizing Distributed User Plane in Private 5G Networks. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 120340–120351. [Google Scholar]

- UERANSIM Team. 5G UE and RAN Simulator. Available online: https://github.com/aligungr/UERANSIM (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Roaring Penguin. RP-PPPoE: PPP Over Ethernet. Available online: http://www.roaringpenguin.com/products/pppoe (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- OpenAirInterface Software Alliance. 5G RAN & Core Platforms. Available online: https://openairinterface.org (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Internet Systems Consortium (ISC). ISC DHCP Server. Available online: https://www.isc.org/dhcp/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Xelerance. xl2tpd: L2TP Daemon. Available online: https://github.com/xelerance/xl2tpd (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- MongoDB Inc. MongoDB Community Server. Available online: https://www.mongodb.com/try/download/community (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Hitayezu, A. Zone-Access Gateway Function Data. Available online: https://hackmd.io/@rkT12RG1TWOl4CBfOlDE4w/BJ4nWnNcA (accessed on 9 November 2025).

| N5GC ID | Z-CU Z-AGF ID | Z-CU, Z-AGF IP |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||

| 1 | 2 | 10.51.0.88 |

| Configuration | Average (ms) | Improvement (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Standard W-AGF (Baseline) | 412 | – |

| I-UPF (Intermediate) | 308 | 25.2% reduction |

| Z-AGF Enabled | 252 | 38.8% reduction |

| Z-AGF with LBO | 224 | 45.6% reduction |

| Configuration | PLR (%) | SCR (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Standard W-AGF (Baseline) | 7.8 | 86.3 |

| I-UPF (Intermediate) | 4.6 | 92.7 |

| Z-AGF Enabled | 3.1 | 96.5 |

| Z-AGF with LBO | 2.4 | 98.1 |

| Feature | W-AGF | I-UPF | Z-AGF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Session continuity | Limited | Partial | Full (CU) |

| Local breakout | Core | Edge | Integrated (UPEF) |

| Mobility management | None | Limited | Z-CU (MBB) |

| Latency optimization | Moderate | High | Ultra-Low (LBO) |

| IP management | Static | Shared | Dynamic (LNS) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hitayezu, A.; Wang, J.-T.; Dini, S.Z. Zone-AGF: An O-RAN-Based Local Breakout and Handover Mechanism for Non-5G Capable Devices in Private 5G Networks. Electronics 2025, 14, 4794. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244794

Hitayezu A, Wang J-T, Dini SZ. Zone-AGF: An O-RAN-Based Local Breakout and Handover Mechanism for Non-5G Capable Devices in Private 5G Networks. Electronics. 2025; 14(24):4794. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244794

Chicago/Turabian StyleHitayezu, Antoine, Jui-Tang Wang, and Saffana Zyan Dini. 2025. "Zone-AGF: An O-RAN-Based Local Breakout and Handover Mechanism for Non-5G Capable Devices in Private 5G Networks" Electronics 14, no. 24: 4794. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244794

APA StyleHitayezu, A., Wang, J.-T., & Dini, S. Z. (2025). Zone-AGF: An O-RAN-Based Local Breakout and Handover Mechanism for Non-5G Capable Devices in Private 5G Networks. Electronics, 14(24), 4794. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244794