Design of a Blockchain-Based Ubiquitous System for the Supply Chain with Autonomous Vehicles

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Smart Contracts in Ethereum

- Contractually defined terms and conditions, along with established procedures, designed by the parties to facilitate the exchange.

- Software implementation, since the contract operations are specified by lines of software code.

- Algorithms that define the rules that each party must comply with in order to perform actions in relation to the smart contract.

- Self-execution of the contract, since once signed, the execution is automated and the results are usually irrevocable.

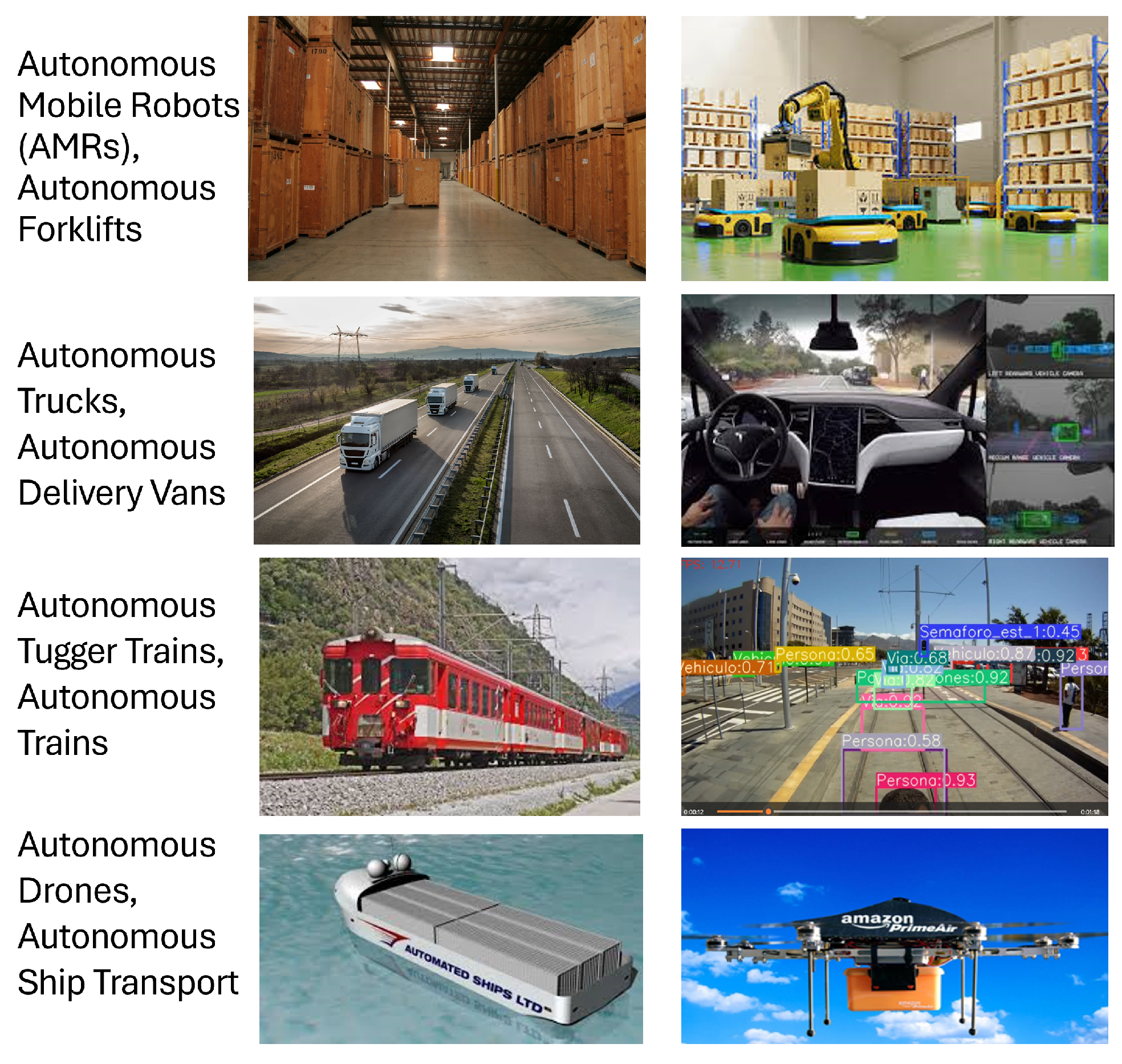

1.2. Autonomous Vehicles

- Autonomous Trucks: These are essential for long-distance transport and use artificial intelligence-based navigation to optimize routes and reduce fuel consumption. Leading this technological development are Tesla, Waymo, and Daimler.

- Autonomous Delivery Vans: They optimize last-mile delivery and navigate urban environments using real-time data. Examples include Nuro’s delivery pods and Amazon’s Scout.

- Autonomous Drones: They enable aerial deliveries to remote locations and are used by companies such as Zipline and Wing to transport medical and consumer products.

- Autonomous Mobile Robots (AMRs): Used in warehouses for picking, sorting, and transport, developed by Amazon (Kiva Systems) and Fetch Robotics.

- Autonomous Forklifts: Automate material handling, increasing efficiency and safety, with solutions from Seegrid and Toyota.

- Autonomous Tugger Trains: Used in manufacturing to transport materials along predefined routes, benefiting lean production environments.

- (1)

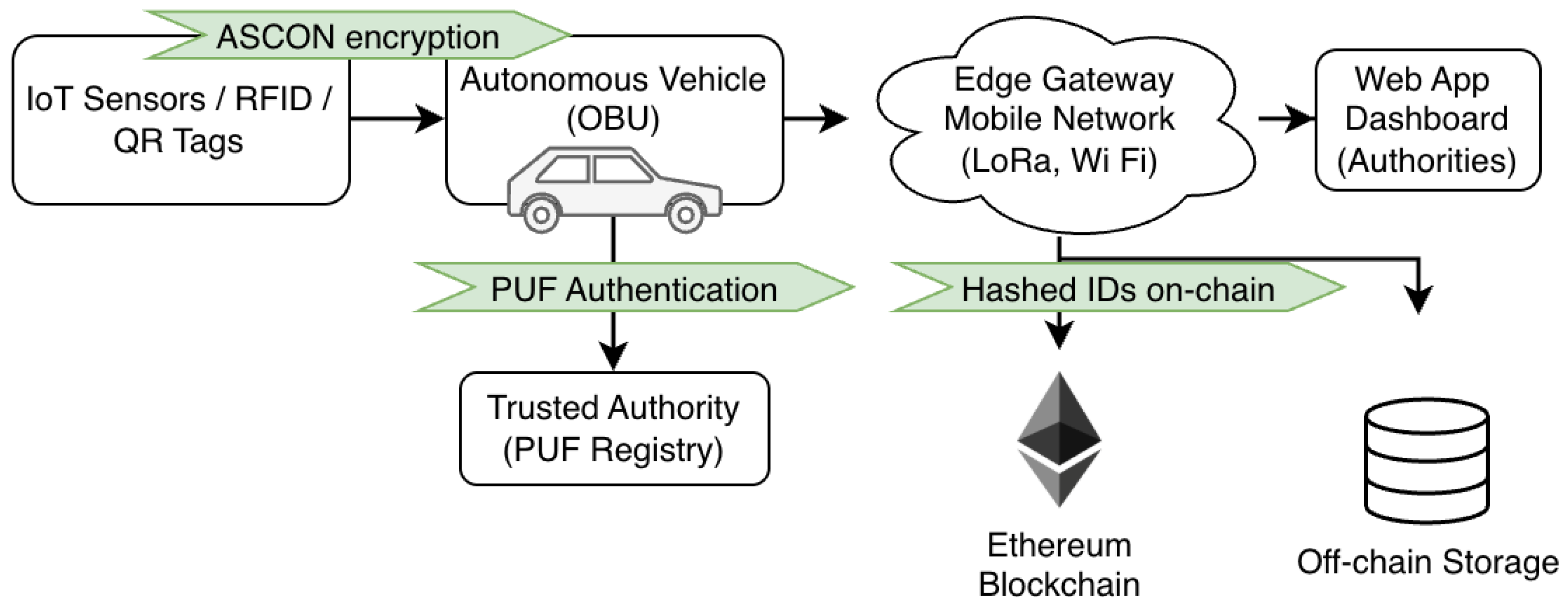

- It proposes a blockchain-based architecture that integrates IoT devices, RFID/QR technologies, and Autonomous Vehicles for real-time logistics monitoring.

- (2)

- It provides an implemented proof-of-concept on Ethereum 2.0, including smart contracts, a web interface, and an Android-based On-Board Unit (OBU).

- (3)

- It presents a quantitative analysis of gas consumption and transaction costs, validating the feasibility and efficiency of the system.

- (4)

- It incorporates advanced cryptographic mechanisms, such as Physical Unclonable Functions and lightweight encryption, to enhance privacy and security in the supply-chain process.

2. Related Work

2.1. Blockchain in Logistics

2.2. Integration with Autonomous Vehicles

2.3. IoT, RFID, and QR Technologies

2.4. Smart Contracts and Scalability

3. An Automated Blockchain-Based System for the Supply Chain

3.1. Phases of the Transport Process

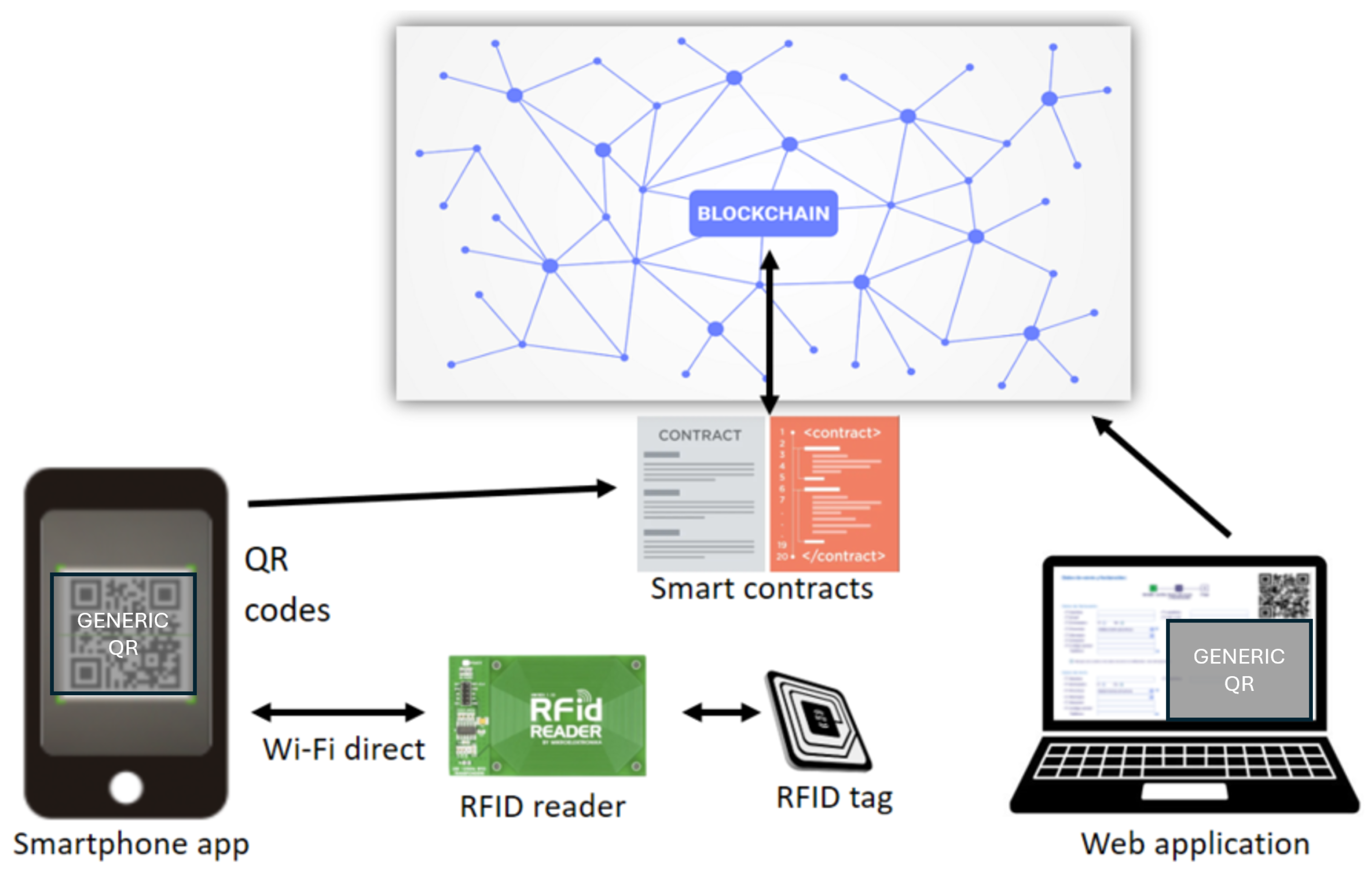

- Before transporting goodsThe first phase consists of organizing the goods to be transported and generating the corresponding delivery note. This delivery note will not only detail the goods corresponding to a customer but will also include a QR code. The purpose of this QR code is to digitally display the content of the delivery note and, therefore, the content of the container. After scanning it, it will provide the following information: ID of the delivery note, number of products, product code, date, origin, and destination of the goods, and companies and carriers. Since this QR code will be attached to the container, the information included in it will be protected using the lightweight authenticated encryption standard (ASCON) [21]. ASCON, established by NIST as a standard for Lightweight Authenticated Ciphers, provides both a hash function and a version with a longer key length resistant to brute force attacks through Grover’s algorithm. Hence, it protects against some quantum attacks.Finally, in this phase, the goods are labeled. For this, RFID codes are used to automate the merchandise check, which is detailed in the next phase. Once this phase is completed, the first transaction for the blockchain is generated, allowing the monitoring and control of the goods. This transaction contains information about items that are transported in clear or a hash with the information in case it is private.

- Loading and transport of goodsOnce the truck/vehicle is loaded, the mapping between the goods and the delivery note is carried out. For this, the truck has an RFID reader with a WiFi connection, which is used to read the RFID tags of the merchandise placed on the truck, and through a WiFi connection, it sends the information to the vehicle’s mobile terminal, where the mapping is carried out. If the mapping is correct, the ID of the delivery note and the ID of the vehicle are associated. At this time, the vehicle starts the transport of goods, and a new transaction is generated with this information on the blockchain. On the contrary, if the mapping is not correct, the vehicle alerts to correct the problems for the transport of goods, and a new blockchain transaction is generated with the vehicle’s ID, the delivery note ID, and the reasons for the rejection. This phase is repeated as many times as the goods change the carrier.

- Freight transportDuring this phase, the proposed system allows two types of monitoring: the location of the goods at any time and the control of the merchandise. The first one is carried out with the GPS coordinates issued by the vehicle’s terminal, and a transaction for the blockchain is generated every time there is a large enough pool of locations. The second method involves connecting to the carrier’s application, allowing the owner of the goods to remotely query the status of the merchandise at any time. This transaction is registered on the blockchain, identifying the person who requested the query.

- Control of merchandise by the authoritiesThe proposed system simplifies the work of authorities who need information about transported goods. Through a custom interface for customs authorities, they can quickly access details about the goods, including their origin and destination. This access is also recorded on the blockchain. Additionally, authorities will have full access to the blockchain, allowing them to see all transactions generated throughout the process.

3.2. System Implementation

4. Implemented Prototype

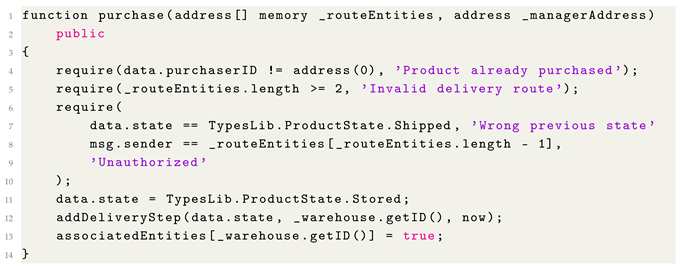

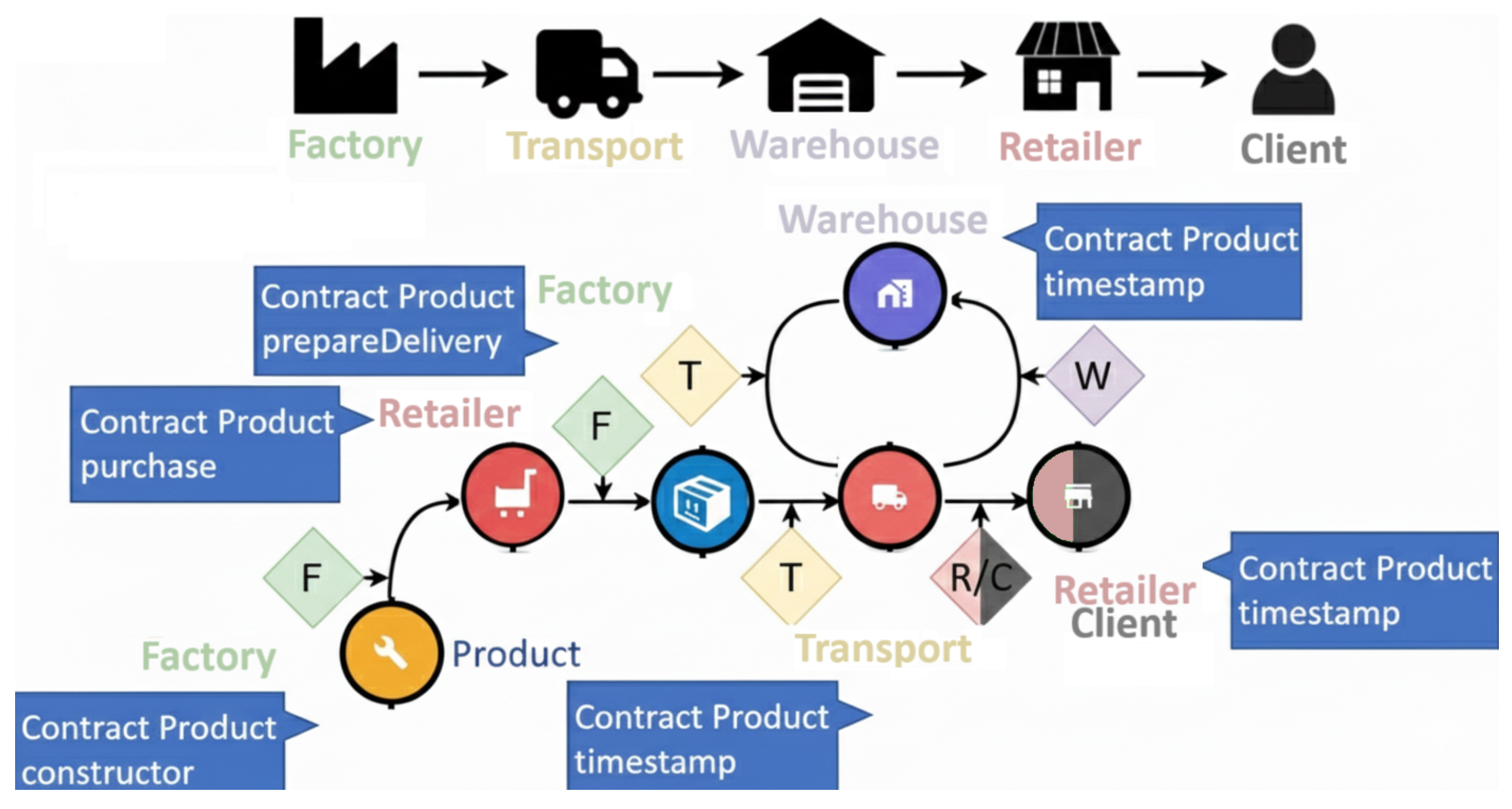

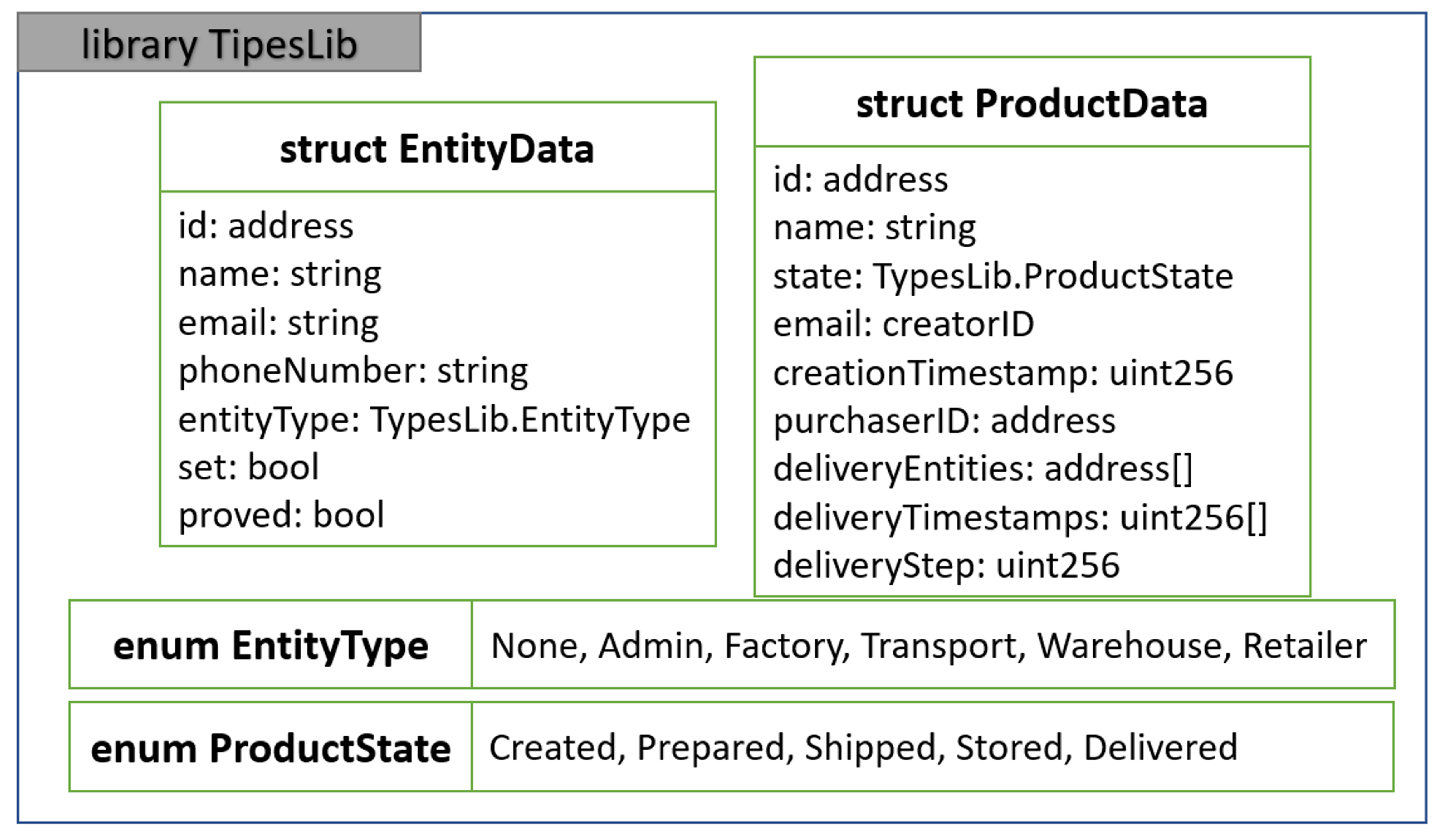

4.1. Implementation of Smart Contracts for the Supply Chain System

- purchase (see Listing 1): It starts the product lifecycle and creates the complete route for this specific product.

- prepareDelivery: It sets the product status to Prepared, in the place to connect the RFID reader to check that the products are in the container.

- timestampDeliveryStep: It changes the status and timestamp of the products.

| Listing 1. Smart contract purchase function. |

|

4.2. Integration of RFID and QR Code Technologies in Supply Chain Management

4.3. OBU Android Application

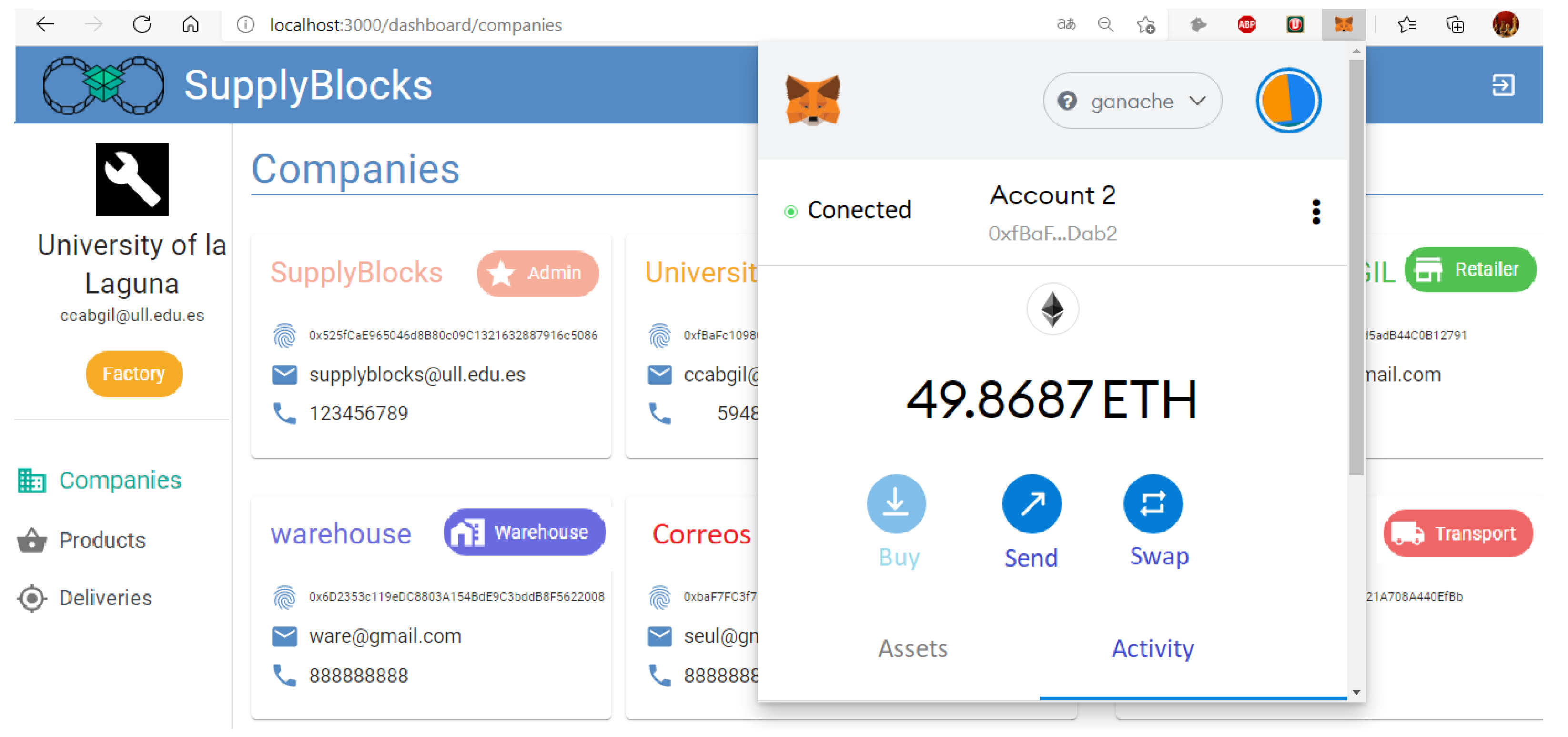

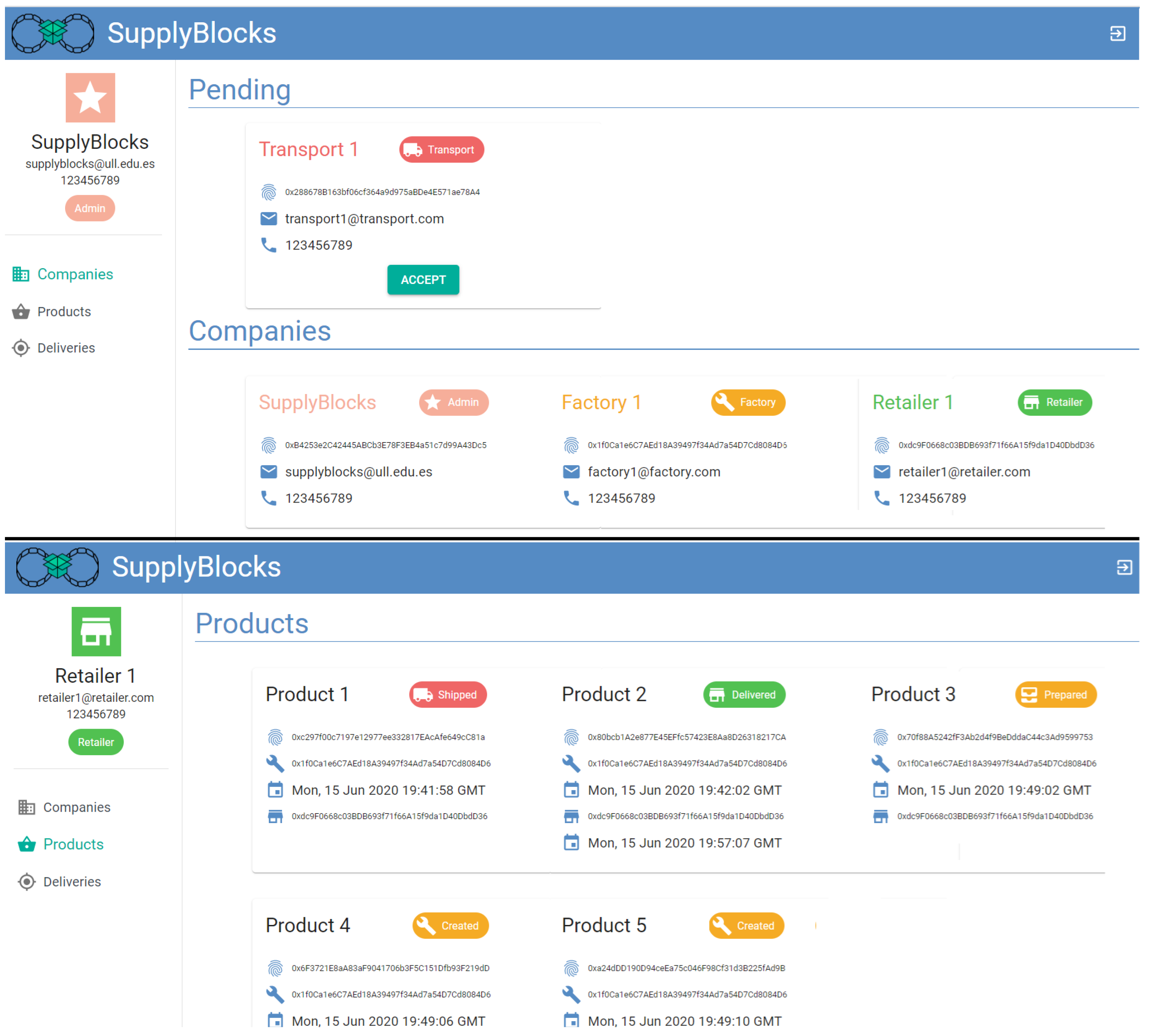

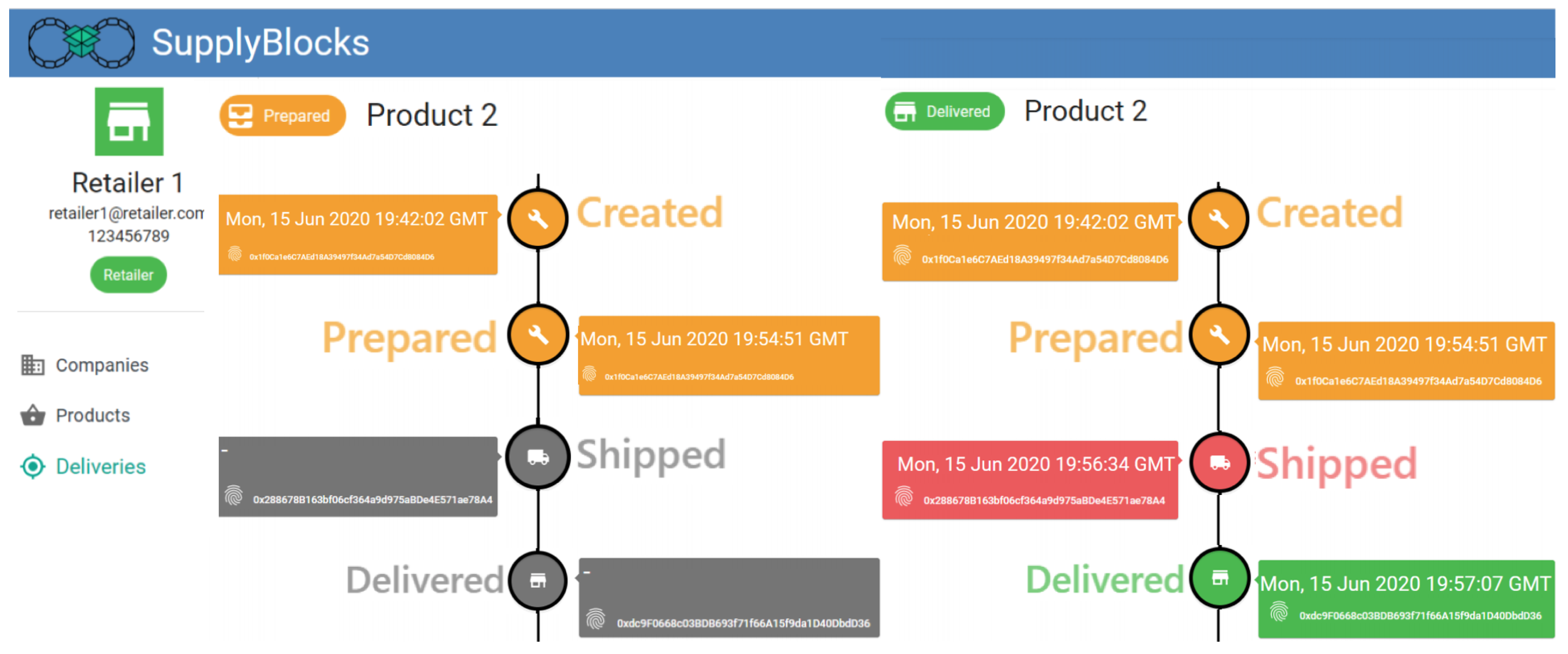

4.4. Web Application

- Product name;

- Product status;

- Address of the associated product smart contract;

- Entity smart contract address of type F user who created it;

- Creation date;

- Entity smart contract address of the type M user who acquired it or if it has been acquired;

- Delivery date, if delivered.

- Administrator: all registered products are displayed.

- Manufacturer: a form is displayed to add new products. If a product has been purchased, a button will appear next to its card to prepare the shipment, or whatever the same, to change the status of the product from C to P.

- Retailer: all registered products appear, and a button next to them to purchase them. This type of user is the only one who can purchase products.

- Transport company: products to be transported or products transported in the past are displayed.

- Warehousing company: products currently or past stored are displayed.

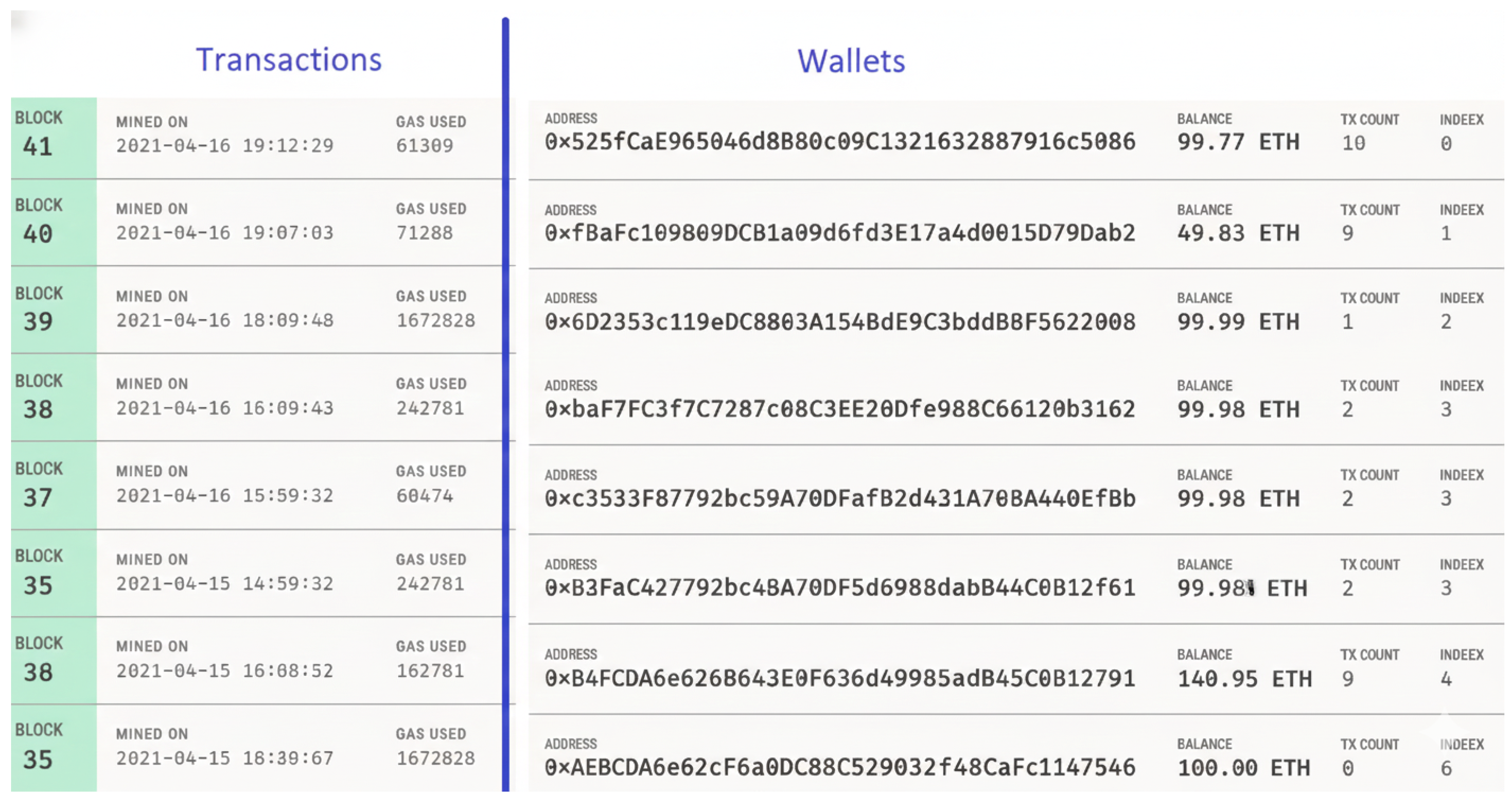

4.5. Experimental Setup

- Hardware Environment:

- –

- Server/PC: The blockchain node and web application were hosted in a local development environment on a desktop PC (Dell, Round Rock, Texas, USA) equipped with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-6400 CPU @ 2.70 GHz and 16.0 GB RAM, running a 64-bit Windows operating system (Windows 10/11).

- –

- OBU (On-Board Unit): A Nexus 5 smartphone was used as the hardware for the initial proof-of-concept implementation phase of this research (c. 2014).

- –

- IoT Hardware: A Small long-range UHF RFID reader module (Invelion, Shenzhen, China) with an R200 chip, TTL antenna, and UART board SDK for ESP32 Raspberry Pi embedded system.

- Software Environment:

- –

- Blockchain Stack:The system was simulated on an Ethereum network using Ganache v7.9.0. Smart contracts were written in Solidity v0.8.20 and deployed via the Truffle Suite v5.11.5.

- –

- Web Stack: The web backend used Node.js v18.LTS, MongoDB v6.0, React v18, and the web3.js v1.10.0 library.

- –

- Mobile OBU Stack:The OBU application was developed natively for Android 4.4 (KitKat) in an Eclipse IDE with the ADT plugin, using Java (JDK 7) and the ZXing (Zebra Crossing) v3.5.0 library.

5. Discussion

5.1. Security and Privacy Analysis

5.2. Scalability Analysis

5.3. Performance Evaluation and Platform Justification

5.4. Comparison with Related Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olivié, I.; Gracia, M. Is this the end of globalization (as we know it)? Globalizations 2020, 17, 990–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.K.S.; Ting, H.Y.; Atanda, A.F. Enhancing Supply Chain Traceability through Blockchain and IoT Integration: A Comprehensive Review. Green Intell. Syst. Appl. 2024, 4, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yu, Q.; Wan, S.; Cao, H.; Huang, Y. Digital supply chain: Literature review of seven related technologies. Manuf. Rev. 2024, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Feng, X.; Jiang, Z.; Gong, Q.; Wang, Y. A blockchain-enabled framework for reverse supply chain management of power batteries. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 415, 137823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y. Blockchain-Based Information Sharing Mechanism for Complex Product Supply Chain. Electronics 2025, 14, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero-García, A.; Santos-González, I.; Caballero-Gil, C.; Molina-Gil, J.; Hernández-Goya, C.; Caballero-Gil, P. Blockchain-Based Ubiquitous Transport and Logistics Monitoring System. Proceedings 2019, 31, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simchi-Levi, D.; Kaminsky, P.; Simchi-Levi, E. Designing and Managing the Supply Chain: Concepts, Strategies and Case Studies, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York City, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rejeb, A.; Rejeb, K.; Simske, S.; Treiblmaier, H. Blockchain Technologies in Logistics and Supply Chain Management: A Bibliometric Review. Logistics 2021, 5, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, A.; Khari, M.; Misra, S.; Sugandh, U. Blockchain in Agriculture to Ensure Trust, Effectiveness, and Traceability from Farm Fields to Groceries. Future Internet 2023, 15, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolakis, N.; Schumacher, R.; Dora, M.; Kumar, M. Artificial intelligence and blockchain implementation in supply chains: A pathway to sustainability and data monetisation? Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 327, 157–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varriale, V.; Cammarano, A.; Michelino, F.; Caputo, M. Blockchain as enabling factor for implementing RFID and IoT technologies in VMI: A simulation on the Parmigiano Reggiano supply chain. Oper. Manag. Res. 2022, 15, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugurusi, G.; Ahishakiye, E. Blockchain technology needs for sustainable mineral supply chains: A framework for responsible sourcing of Cobalt. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 200, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Wang, H.C. Autonomous Vehicles Enabled by the Integration of IoT, Edge Intelligence, 5G, and Blockchain. Sensors 2023, 23, 1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toorajipour, R.; Sohrabpour, V.; Nazarpour, A.; Oghazi, P.; Fischl, M. Artificial Intelligence in Supply Chain Management: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 502–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathla, G.; Bhadane, K.; Singh, R.K.; Kumar, R.; Aluvalu, R.; Krishnamurthi, R.; Kumar, A.; Thakur, R.N.; Basheer, S. Autonomous Vehicles and Intelligent Automation: Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022, 2022, 7632892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldweesh, A. A Blockchain-Based Data Authentication Algorithm for Secure Information Sharing in Internet of Vehicles. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunmozhi, M.; Venkatesh, V.; Arisian, S.; Shi, Y.; Sreedharan, V.R. Application of blockchain and smart contracts in autonomous vehicle supply chains: An experimental design. Transp. Res. Part Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 165, 102864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; He, J.; Cheng, X.; Liu, Z. Electric Vehicle Charging Transaction Model Based on Alliance Blockchain. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogarajan, L.; Masukujjaman, M.; Ali, M.H.; Khalid, N.; Osman, L.H.; Alam, S.S. Exploring the Hype of Blockchain Adoption in Agri-Food Supply Chain: A Systematic Literature Review. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.; Adu-Duodu, K.; Li, Y.; Sham, R.; Almubarak, M.; Wang, Y.; Solaiman, E.; Perera, C.; Ranjan, R.; Rana, O. Blockchain-Enabled Provenance Tracking for Sustainable Material Reuse in Construction Supply Chains. Future Internet 2024, 16, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobraunig, C.; Eichlseder, M.; Mendel, F.; Schläffer, M. Ascon v1.2: Lightweight Authenticated Encryption and Hashing. J. Cryptol. 2021, 34, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unhelkar, B.; Joshi, S.; Sharma, M.; Prakash, S.; Mani, A.K.; Prasad, M. Enhancing supply chain performance using RFID technology and decision support systems in Industry 4.0: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2022, 2, 100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanadham, Y.V.R.S.; Jayavel, K. A Framework for Data Privacy Preserving in Supply Chain Management Using Hybrid Meta-Heuristic Algorithm with Ethereum Blockchain Technology. Electronics 2023, 12, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanescu, D.; Galán-García, P.; Montalvillo, L.; Urbieta, A. A Systematic Literature Review of Lightweight Blockchain for IoT. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 123138–123159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Si, X.; Kang, H. A Literature Review of Blockchain-Based Applications in Supply Chain. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androulaki, E.; Barger, A.; Bortnikov, V.; Cachin, C.; Christidis, K.; Caro, A.D.; Enyeart, D.; Ferris, C.; Gagliano, G.; Manevich, Y.; et al. Hyperledger Fabric: A Distributed Operating System for Permissioned Blockchains. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth EuroSys Conference, Porto, Portugal, 23–26 April 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, S.; Kouhizadeh, M.; Sarkis, J.; Shen, L. Blockchain technology and its relationships to sustainable supply chain management. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 2117–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touloupou, M.; Themistocleous, M.; Iosif, E.; Christodoulou, K. A Systematic Literature Review Toward a Blockchain Benchmarking Framework. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 70630–70644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshudukhi, K.S.; Khemakhem, M.A.; Eassa, F.E.; Jambi, K.M. An Interoperable Blockchain Security Frameworks Based on Microservices and Smart Contract in IoT Environment. Electronics 2023, 12, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Chong, H.Y.; Xu, Y. Blockchain-Smart Contracts for Sustainable Project Performance: Bibliometric and Content Analyses. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 8159–8182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar, I.; Debe, M.; Jayaraman, R.; Salah, K.; Omar, M.; Arshad, J. Blockchain-based Supply Chain Traceability for COVID-19 PPE. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 167, 107995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perboli, G.; Musso, S.; Rosano, M. Blockchain in Logistics and Supply Chain: A Lean Approach for Designing Real-World Use Cases. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 62018–62028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A’zam, M.K.Z.N.; Muhammad, M.H.; Ahmarofi, A.A.; Zukhi, M.Z.M.; Sobry, S.C.; Hanafi, A.H.A. Integrating Blockchain, AI, and RFID Technologies to Combat Counterfeiting in Supply Chain Management: A Comprehensive Literature Review. J. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2025, 10, 87–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqarni, M.A.; Alkatheiri, M.S.; Chauhdary, S.H.; Saleem, S. Use of Blockchain-Based Smart Contracts in Logistics and Supply Chains. Electronics 2023, 12, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Mehmood, A.; Maple, C.; Curran, K.; Song, H. Performance Analysis of Blockchain-Enabled Security and Privacy Algorithms in Connected and Autonomous Vehicles: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 4773–4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, D. SupplyBlocks. 2020. Available online: https://github.com/DauteRR/SupplyBlocks (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- Rodríguez, D. Master’s Final Project: Aplicación de Blockchain en Logística. Master’s Thesis, University of La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Babaei, A.; Schiele, G. Physical Unclonable Functions in the Internet of Things: State of the Art and Open Challenges. Sensors 2019, 19, 3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B.; Peng, S.; Wu, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, B. LoRa-Based Physical Layer Key Generation for Secure V2V/V2I Communications. Sensors 2020, 20, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Guo, E.; Lian, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, X.; Su, C. A review and implementation of physical layer channel key generation in the Internet of Things. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2024, 83, 103779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwal, A.; Gangavalli, H.R.; Thirupathi, A. A survey of Layer-two blockchain protocols. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2023, 209, 103539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, P.; Jauhar, S.; Ramkumar, M.; Pratap, S. Procurement, Traceability and Advance Cash Credit Payment Transactions in Supply Chain Using Blockchain Smart Contracts. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 167, 108038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T. An agri-food supply chain traceability system for China based on RFID & blockchain technology. In Proceedings of the 2016 13th International Conference on Service Systems and Service Management, Kunming, China, 24–26 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Helo, P.; Shamsuzzoha, A. A blockchain architecture for project deliveries. Robot. -Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2020, 63, 101909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ShipChain Company. The End-to-End Logistics Platform of the Future: Trustless, Transparent Tracking. 2019. Available online: https://www.blockdata.tech/profiles/shipchain (accessed on 30 January 2022).

| Reference | Objective | Technologies | Main Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| [2] | Supply chain traceability | Blockchain, IoT | Identified benefits and limitations of blockchain–IoT integration |

| [5] | Information sharing in complex product supply chains | Blockchain, CP-ABE, IPFS | Proposed a secure and efficient information-sharing mechanism enhancing transparency and collaboration |

| [4] | Reverse supply chain management of power batteries | Blockchain, Smart contracts, Double-chain structure | Improved traceability and transparency in battery recycling |

| [23] | Privacy-preserving data protection in supply chain management | Blockchain, Hybrid meta-heuristic optimization, Ethereum smart contracts | Developed a privacy-preserving framework improving data confidentiality and secure processing in supply-chain operations |

| [3] | Digital transformation of supply chains | Blockchain, AI, IoT, Big Data | Proposed integration framework linking seven key digital technologies to optimize logistics performance |

| Smart Contract Function | Average Gas Used |

|---|---|

| Manager.createEntity | 719,498 |

| Manager.approveEntity | 59,319 |

| Product.constructor | 1,672,850 |

| Product.purchase | 242,781 |

| Product.prepareDelivery | 71,288 |

| Product.timestamp | 60,474 |

| Supply Chain System | Blockchain Tracking | Real-Time Tracking | RFID Checking | Authorities Interface | Implemented |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omar et al. [42] | Yes, not specified | Not mentioned | RFID is used for authentication | Not mentioned | No |

| Feng [43] | Yes (platform not mentioned) | Yes, GPS | Yes, method not specified | indirectly | No |

| Helo et al. [44] | Yes (Ethereum and Kovan Network) | Yes, GPS | Yes, method not specified | not mentioned | Yes, blockchain, web and smartphone app |

| Shipchain [45] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not mentioned | Offers implementations |

| SupplyBlocks | Ethereum, in the future, Cardano | Yes, GPS and positioning systems | Yes, in containers | Yes | Yes, Ethereum blockchain, web platform, and Android app |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caballero-Gil, C.; Molina-Gil, J.; Hernández-Goya, C.; Diaz-Santos, S.; Burmester, M. Design of a Blockchain-Based Ubiquitous System for the Supply Chain with Autonomous Vehicles. Electronics 2025, 14, 4744. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234744

Caballero-Gil C, Molina-Gil J, Hernández-Goya C, Diaz-Santos S, Burmester M. Design of a Blockchain-Based Ubiquitous System for the Supply Chain with Autonomous Vehicles. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4744. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234744

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaballero-Gil, Cándido, Jezabel Molina-Gil, Candelaria Hernández-Goya, Sonia Diaz-Santos, and Mike Burmester. 2025. "Design of a Blockchain-Based Ubiquitous System for the Supply Chain with Autonomous Vehicles" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4744. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234744

APA StyleCaballero-Gil, C., Molina-Gil, J., Hernández-Goya, C., Diaz-Santos, S., & Burmester, M. (2025). Design of a Blockchain-Based Ubiquitous System for the Supply Chain with Autonomous Vehicles. Electronics, 14(23), 4744. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234744