1. Introduction

In recent years, UAV swarms have demonstrated remarkable potential in large-scale IoT and smart agriculture applications, such as crop monitoring, precision spraying, and environmental sensing [

1,

2,

3]. A key capability underlying these applications is the cooperative observation of multiple moving or dynamic targets in complex environments—formally defined as the Cooperative Multi-Robot Observation of Multiple Moving Targets (CMOMMT) problem [

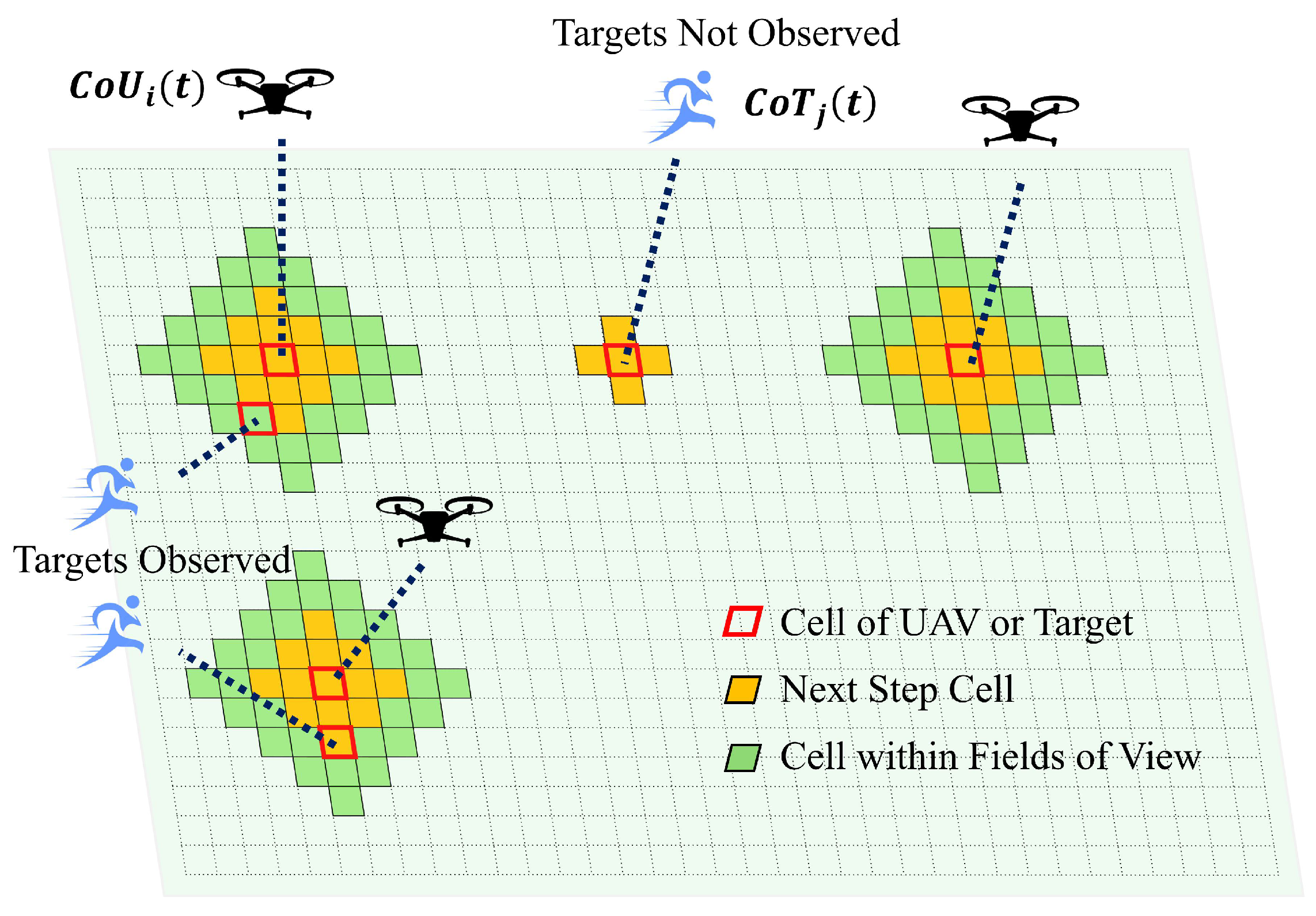

4]. The central objective of CMOMMT is to maximize the average observation rate across all targets by continuously balancing target following and exploratory search, despite the limited field-of-view and mobility constraints of each UAV, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

A wide spectrum of coordination strategies has been explored to address the CMOMMT problem, ranging from classical heuristic methods to modern learning-based frameworks [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Early approaches, such as force-vector and frontier-based methods, relied on local rules for decentralized cooperation. Later, optimization-based strategies (e.g., profit-driven algorithms, Particle Swarm Optimization, and Ant Colony Optimization) improved task allocation efficiency but required handcrafted objectives. Reinforcement learning (RL) methods further enhanced adaptiveness but often suffered from high sample complexity and instability in large-scale scenarios.

Among learning-based approaches, our previous work proposed the Supervised and Transfer Learning Framework (STLF) [

9], a two-stage framework that trains a Teacher Model with privileged global information and transfers knowledge to a Student Model operating under partial observability. STLF demonstrated strong performance in achieving high observation rates and outperforming several baselines. However, the original STLF operates under an idealized assumption of reliable and synchronous communication between UAVs and the Ground Base Station (GBS). In practice, UAV swarms often operate in wireless environments with limited bandwidth and shared uplink channels. Building upon the original STLF framework, this work enhances its applicability to realistic network environments by incorporating mechanisms to handle communication impairments such as congestion, collisions, and packet loss, which are frequently encountered in real-world UAV swarm deployments.

When multiple UAVs simultaneously transmit status updates or receive commands from the GBS, network congestion can occur, leading to packet loss, delayed feedback, or even complete link failures [

10,

11]. Since centralized policies like STLF depend on timely and reliable communication, these network degradations can directly reduce coordination efficiency and overall tracking performance. Studies show that Ultra-Wideband can support accurate inter-UAV ranging, but even wideband systems remain constrained by limited spectrum and sensitivity to interference in dense swarms [

12,

13]. These observations further highlight that communication quality is a fundamental bottleneck, motivating coordination strategies that explicitly account for communication states. This challenge calls for a communication-aware swarm coordination framework that can adapt UAV behaviors to the underlying network state in real time.

To address this challenge, we propose CSOOC, a hybrid control architecture that integrates learning-based and rule-based policies while explicitly accounting for communication dynamics. CSOOC consists of three tightly coupled modules. First, during online mode, UAVs execute globally coordinated control commands generated by the STLF model, leveraging centralized decision-making for efficient target observation. Second, during offline mode, UAVs switch to a profit-driven mobility strategy based on locally constructed Gaussian maps, enabling autonomous target following and exploration when communication is degraded. Finally, to ensure smooth and stable coordination between these two modes, a STAR congestion control module is integrated into the framework. By combining temporal transmission desynchronization with RTS/CTS-based (Request-To-Send/Clear-To-Send) [

14] channel reservation, STAR mitigates network congestion and stabilizes uplink reliability, reducing unnecessary mode switching and maintaining consistent control performance.

The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

A communication-aware UAV swarm coordination framework, termed CSOOC, is introduced to enable dynamic online–offline behavioral switching under realistic and time-varying network conditions.

A profit-driven offline mobility strategy based on Gaussian maps is designed to maintain spatially informed target tracking during communication interruptions.

A dual-layer congestion control mechanism, named STAR, is developed by combining temporal transmission stratification with RTS/CTS handshake to enhance network reliability and mitigate packet collisions.

A unified co-simulation paradigm is established to bridge network communication and swarm control, allowing systematic evaluation of coordination performance under practical communication constraints.

These contributions also provide a new perspective on coupling network simulation with swarm coordination, enabling the study of UAV behavior under communication constraints. STAR reduces the impact of congestion, and the online–offline mechanism enables the swarm to adjust its coordination strategy according to current communication states.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work on CMOMMT coordination and communication-aware swarm control.

Section 3 formulates the problem and system architecture.

Section 4 presents the proposed CSOOC.

Section 5 reports extensive experimental results under varying network and swarm configurations.

Section 6 concludes the paper and discusses future directions.

3. Task Formulation

3.1. Mission Overview and Notation

In this study, we focus on the CMOMMT problem while incorporating realistic network communication modeling. By embedding a network simulator (NS-3 [

23]) into the mission workflow, the decision-making process accounts for communication latency, packet loss, and bandwidth constraints, thus reflecting more practical UAV‘s operation scenarios.

The illustration of CMOMMT formulation is shown in

Figure 2, and the key elements are defined as follows:

Search Region. The search region is modeled as a 2D square grid, discretized into uniform cells represented by gray dashed lines.

Time Step. Time is discretized into steps indexed by , where T denotes the total mission duration.

Targets. There are M homogeneous targets. The position of target j at time step t is denoted by , indicating the grid cell it occupies. At each time step, targets move to one of the four adjacent cells (up, down, left, or right), following a bounded mobility model.

UAVs. A set of N homogeneous UAVs are deployed in the search region to observe the M targets (). The UAVs have a higher maximum speed than the targets; otherwise, a target could easily evade pursuit by moving at its maximum speed. Additionally, UAVs maintain a fixed altitude throughout the mission. Each UAV is equipped with:

- 1.

GPS for self-localization.

- 2.

Onboard cameras to observe ground targets. UAV i observes cells within a given Euclidean radius, forming its field of view . If target j lies within , i.e., , it is considered observed. Areas outside remain unknown to UAV i, reflecting partial observability.

- 3.

Wireless communication modules to transmit observations to the GBS over a modeled network (e.g., LTE/5G) in NS-3, where transmission is subject to latency, packet loss, and congestion effects.

CMOMMT Workflow. Figure 3 shows the mission workflow. At each time step, UAVs first conduct local observations. The collected data are then transmitted via the simulated network to the GBS. The GBS aggregates information from all UAVs and computes coordinated movement decisions, which are sent back to the UAVs through the same network. This process, subject to communication delays and potential link interruptions, repeats until

.

Objective Function. The objective is to maximize the average observation rate of all targets over

T, denotedas

:

where

is a binary indicator of whether target

j is observed at time

t:

In the ideal case where every target is observed at each time step, . However, due to UAV mobility constraints, limited FoV, and the effects of network latency and packet loss, achieving for all is generally infeasible. The mission goal is to design a coordination policy that maximizes under both mobility and communication constraints.

3.2. Target Mobility Model

To construct a biomimetic target trajectory, we adopt a Lévy flight-based motion model that emulates the irregular and nonlinear movement patterns commonly observed in natural foraging behaviors [

9]. Unlike conventional random walks that restrict targets to locally confined regions, Lévy flights generate a mixture of frequent short moves and occasional long jumps, regulated by a heavy-tailed power-law distribution. This biologically inspired characteristic introduces task complexity, requiring the UAV swarm to adapt to diverse and unpredictable target motions. At each step

i, the target position updates as

where

is the step length sampled from a Lévy distribution and

is a unit direction vector. To satisfy speed constraints in simulation, steps exceeding the maximum target speed are segmented into smaller moves.

For each simulated trajectory detail, we first generate a set of discrete trajectory points, then connect them into a continuous path, and finally segment the path according to the target’s movement step size. where the step length

is sampled from a truncated Lévy distribution,

with

controlling the heaviness of the tail and

bounding the maximum displacement per points.

The angle evolves in a Markovian manner,

where

S denotes the turning-strength parameter that governs how abruptly the target can change direction.

Given

and

, the updated position is computed as

each trajectory starts from a random initial location. Excessively long steps are segmented to comply with the maximum speed constraint. Compared with classical random walks, the Lévy flight model produces better reflecting real-world target dynamics and provides a more challenging benchmark for evaluating swarm coordination performance.

3.3. Communication Model

Each UAV maintains a wireless uplink to a GBS to transmit its state information and receive coordinated control commands. We model the communication as a discrete-time process aligned with the control time steps. At each time t, UAV i sends a status packet to the GBS, which may be successfully received or lost depending on network conditions such as channel contention and congestion.

Network congestion and collisions are simulated using the NS-3 environment, incorporating realistic wireless channel modelsprovides the foundation for the traffic control strategy introduced later.

3.4. Baseline Expert Policy: GKA

Within the CSOOC framework, the Greedy Knapsack Algorithm (GKA) serves a dual role: it provides expert supervision for the Teacher Model during the training of the STLF component and acts as an upper-performance reference in subsequent evaluations.

GKA simplifies the CMOMMT task by assuming complete global knowledge of all target positions. At each time step, it executes a two-stage decision process: (1) Point Selection—greedily selecting candidate locations that maximize instantaneous target coverage; and (2) Assignment—employing the Hungarian algorithm to minimize the total UAV travel distance. By combining greedy coverage with optimal assignment, GKA produces near-optimal per-step actions that represent the theoretical upper bound of coordination performance under ideal network conditions. These expert-generated labels are used to train the Teacher Model in STLF, enabling it to approximate the optimal coordination strategy achievable with full information.

4. Methods

4.1. Overview

The proposed CSOOC framework enables robust UAV swarm coordination under dynamic and unreliable communication conditions by tightly coupling swarm control with real-time network states. Its core objective is to ensure continuous and adaptive multi-target tracking through communication-aware decision-making, CSOOC integrates three fundamental components:

Online–Offline Coordination Strategy: UAVs dynamically switch between centralized control and local autonomy based on network connectivity. When communication with the GBS is stable, UAVs follow commands from the STLF module (online mode); when congestion or packet loss occurs, they execute a profit-driven local strategy (offline mode) to maintain observation coverage.

STAR Congestion Control Mechanism: A dual-layer communication regulation approach that combines temporal transmission stratification and RTS/CTS-based channel reservation to reduce packet collisions and stabilize uplink reliability.

Python–NS-3 Co-Simulation Platform: A socket-based bidirectional coupling between the STLF decision engine and the NS-3 network simulator, enabling synchronized evaluation of control and communication performance within each simulation step.

By unifying decision adaptation, congestion regulation, and cross-domain simulation, CSOOC bridges the gap between algorithmic coordination and real-world network dynamics, offering a framework for cooperative multi-UAV tracking in communication-constrained IoT environments.

4.2. Online and Offline Actions

The proposed CSOOC enables UAV swarms to adapt their decision-making strategy according to real-time communication status. When communication with the GBS is reliable, the swarm operates in online mode, executing globally coordinated commands generated by a centralized learning-based controller. When communication is unstable or fails, UAVs switch to offline mode, relying on local observations and autonomous decision-making. This dual-mode design ensures robust and continuous operation of UAV swarms under both ideal and degraded network conditions.

4.2.1. Online Mode: STLF-Based Centralized Control

When communication with the GBS is successful, UAVs operate in online mode, executing control commands generated by the STLF [

9]. The STLF framework learns a near-optimal coordination policy through a Teacher Model trained with privileged global information and then transfers this knowledge to a Student Model adapted to partial observability. As a result, UAVs can perform coordinated decision-making under realistic sensing constraints, maintaining high tracking efficiency.

Two-Stage Learning Paradigm

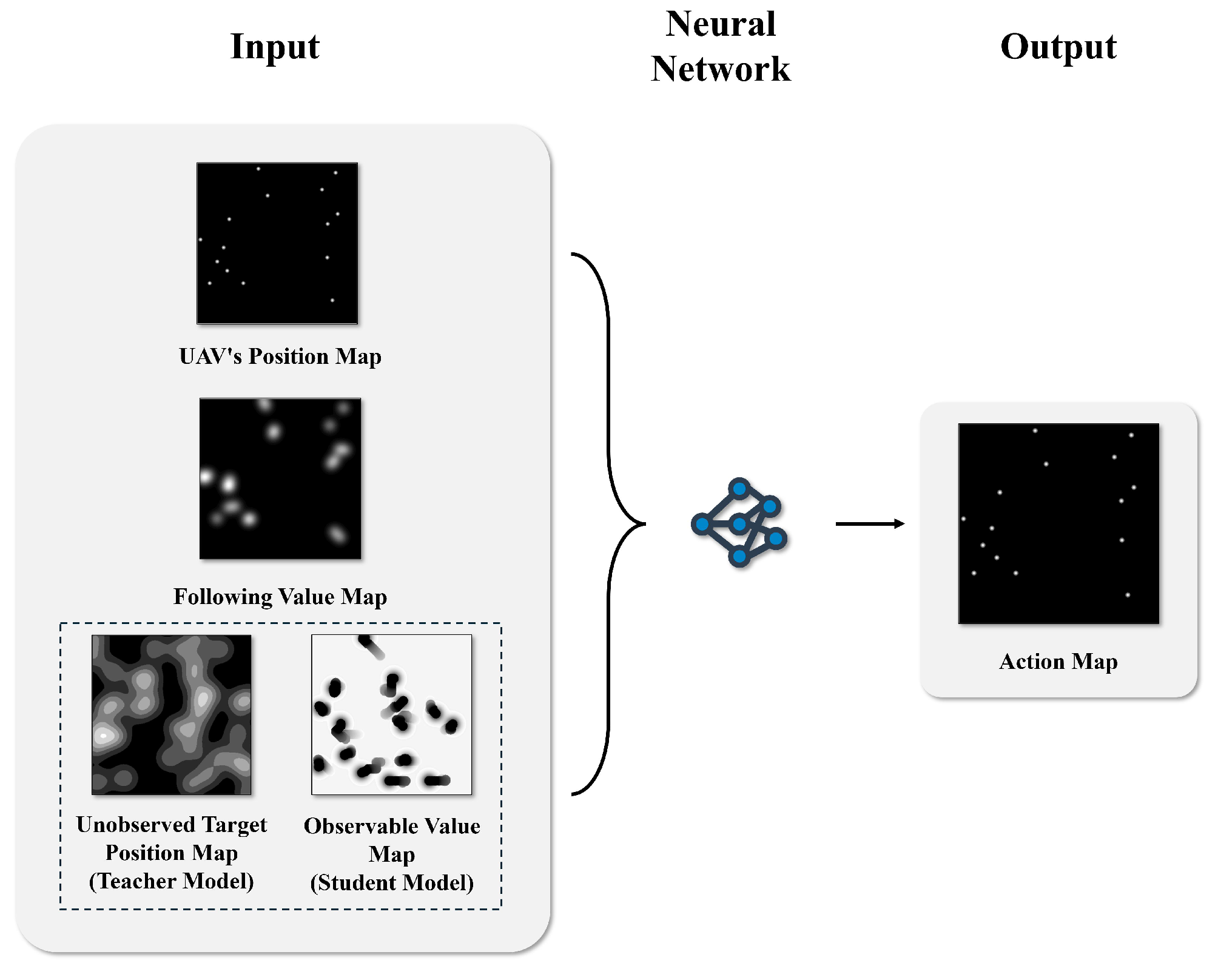

As illustrated in

Figure 4, the STLF consists of two stages:

Stage 1–Teacher Model: trained using expert demonstrations from the GKA, with access to full global information. It learns to output near-optimal movement actions that maximize the overall observation rate.

Stage 2–Student Model: initialized from the Teacher Model and fine-tuned under partial observability. Privileged global data are replaced by an Observable Value Map (OVM), which probabilistically estimates unobserved target distributions.

Gaussian-Based State Representation

At each time step, the environment is represented by four spatial maps that encode UAV states and target-related information as smooth Gaussian distributions. Unlike binary occupancy maps, Gaussian representations provide continuous and differentiable spatial cues, capturing positional uncertainty and improving the model’s spatial reasoning capability.

Specifically, as illustrated in

Figure 5, the input to the neural network consists of:

UAV Position Map: encodes the current positions of all UAVs.

Following Value Map: represents targets currently observed within any UAV’s FoV, modeled as Gaussian peaks centered on detected target locations.

Unobserved Target Map (Teacher only): provides the privileged global positions of targets outside all UAVs’ FoVs during Teacher Model training.

Observable Value Map (Student only): provides a probabilistic estimation of unobserved targets, constructed from historical observations during Student Model deployment.

These four maps are stacked as a multi-channel input tensor and fed into the STLF model, allowing it to jointly consider both tracking and exploration under different information settings.

Centralized Action Generation

The stacked input tensor is processed by the residual CNN backbone of the STLF model, which consists of downsampling, residual, and upscaling modules. The output is an action map indicating the next-step movement decision for each UAV. These commands are generated at the GBS, which aggregates state information from all UAVs and broadcasts the resulting control signals back to the swarm. This centralized control mechanism enables globally coordinated behaviors under ideal communication conditions.

4.2.2. Offline Mode: Profit-Driven Local Control

When communication with the GBS fails due to congestion, packet loss, or excessive delay, UAVs automatically switch to offline mode. In this mode, UAVs can no longer receive centralized commands from the STLF model and must make fully autonomous mobility decisions. The primary goal of the offline strategy is to maintain effective target observation and exploration despite the absence of global coordination. This offline mechanism complements the online mode within the CSOOC, ensuring operational continuity under degraded communication conditions.

Local Map Construction

Inspired by the structure of the STLF input representation, each UAV maintains two local, Gaussian-based maps derived entirely from its own historical observations: the Local Following Value Map () and the Local Observable Value Map (). These maps serve as lightweight surrogates of the global STLF input, enabling UAVs to make autonomous decisions when communication is unavailable.

Local Following Value Map (

): This map encodes the locations of targets currently detected within the UAV’s sensing range. Each observed target at position

is represented by an isotropic 2D Gaussian distribution

where

corresponds to the UAV’s observation radius. Multiple target observations are superposed, while the absence of targets results in a zero map, shifting the UAV’s behavior toward exploration.

Local Observable Value Map (): This map provides a probabilistic estimate of where unobserved targets are most likely to appear, based solely on the UAV’s past observations. It integrates a temporal component—capturing increasing uncertainty with time since last visit—and a spatial component—biasing exploration toward regions just beyond the UAV’s current FoV. controls the spatial spread of this exploration bias.

Both maps are updated locally at each time step:

reflects the latest sensing results, while

accumulates temporal decay and spatial bias information. This design allows each UAV to maintain a compact yet informative representation of its local environment, forming the foundation for profit-driven offline decision-making. Although the structure is conceptually aligned with the global STLF representation (

Figure 5), the local maps only encode state information perceived by a single UAV, without aggregating global observations from the entire swarm.

Profit Function and Movement Selection

At each offline step, the UAV evaluates all candidate positions

within its mobility range. For each candidate, the expected profit is defined as the total increase in local map values obtained after moving to

p, compared with the map constructed at the UAV’s current position

:

where

represents the combined local following and observable value maps.

The UAV then selects the movement that maximizes this profit:

This formulation explicitly compares the candidate map with the map generated at the current position, ensuring that the UAV chooses the location yielding the greatest net information gain.

Behavioral Consistency and Advantages

This profit-driven strategy allows UAVs to autonomously maintain effective coverage during communication outages by exploiting local spatiotemporal information. Because and share the same Gaussian structure as the online STLF inputs, offline actions remain behaviorally consistent with the online mode, enabling smooth policy switching once communication is restored. This ensures that the CSOOC can maintain swarm-level functionality even in the presence of severe communication degradation.

Although CSOOC does not incorporate an explicit collision-avoidance module, it achieves implicit separation through its utility-map design. In the online stage, targets observed by any UAV are removed from the Unobserved Target Map, lowering the utility in that area and naturally preventing UAVs from converging on the same region. During communication loss, the offline policy follows locally constructed profit maps, where previously visited or low-value areas remain unattractive, encouraging further spatial dispersion.

4.3. STAR: Stratified Transmission and RTS/CTS Congestion Control

The proposed coordination framework relies on timely feedback from the GBS. However, a significant challenge arises from the synchronized nature of the UAV swarm: at the beginning of each discrete time step, all UAVs simultaneously attempt to transmit their status updates to the base station. This concurrent transmission leads to severe network congestion, packet collisions, and ultimately communication failures that degrade overall observation performance.

To address this issue, we propose a dual-layer congestion control mechanism termed STAR. STAR integrates temporal desynchronization of UAV transmissions with an RTS/CTS-based channel reservation protocol, providing robust uplink reliability under high-density swarm scenarios.

4.3.1. Stratified Transmission Timing

Instead of having all UAVs transmit at the same instant within a time step, we employ a stratified sampling strategy to distribute transmissions over each one-second interval. Specifically, time is divided into 1-s strata (buckets) denoted as , where is the discrete time step.

For each UAV

, the transmission time within the

k-th stratum is determined by

where

is an independent random variable that follows a uniform distribution over the interval

. This means that all values in

are equally likely to be selected, introducing randomness without bias toward any specific moment within the stratum.

This formulation ensures that each UAV transmits exactly one packet per interval, while the random offset introduces temporal diversity among UAVs. By avoiding phase-locking of transmission schedules, the probability of repeated collisions is reduced. In practice, each UAV maintains an independent timer that triggers the packet transmission at the sampled time within each stratum.

4.3.2. RTS/CTS-Enhanced Handshake

To further reduce packet collisions during the uplink phase, STAR incorporates a Request-to-Send/Clear-to-Send (RTS/CTS [

14]) mechanism into the communication protocol. Before transmitting its data packet, each UAV first sends a short RTS frame to the base station. The base station, upon receiving an RTS, responds with a CTS frame if the channel is clear, thereby reserving the channel for the corresponding UAV.

The handshake success of UAV

i at transmission attempt

can be modeled as

where

is a binary variable indicating whether the RTS/CTS exchange is successful.

This handshake mechanism mitigates hidden terminal problems and minimizes the chance of data packet collisions, which are more costly due to their larger size. The combination of temporally staggered transmissions and channel reservation significantly improves the reliability and throughput of the uplink channel. The STAR scheme is implemented within the NS-3 simulation environment, where the MAC-layer behavior explicitly models the timing and handshake mechanisms.

In addition to reducing packet collisions, STAR addresses bandwidth limitations and latency fluctuations in dense UAV swarms. By assigning stratified transmission windows, STAR prevents a large number of UAVs from contending for the channel simultaneously, which reduces instantaneous congestion.

4.4. NS-3 with Python’s Communication

To simulate the impact of network conditions on swarm coordination, we establish a bidirectional communication link between the Python-based CMOMMT environment simulation and the NS-3 network simulator. This integration is achieved through a socket-based interface, enabling real-time data exchange between the two simulation environments. The communication process is designed to operate in a discrete-time manner, with each time step

t corresponding to a synchronized simulation cycle in both platforms.

Figure 6 shows the interaction description at each discrete moment.

At the beginning of each time step, the Python environment sends the current positions to the NS-3 simulator via a TCP socket. This data packet includes the coordinates of each UAV, which are used by NS-3 to model wireless transmission between the UAVs and the GBS. The NS-3 simulator then emulates the uplink communication process, incorporating factors such as signal propagation, interference, packet collisions, and queuing delays based on the configured network model. The output of this simulation—namely, the success or failure of each UAV’s transmission—is returned to the Python side through the same socket connection.

On the Python side, the CMOMMT simulation environment processes the received communication feedback to determine the operational mode for each UAV. If a UAV successfully receives a control command from the GBS within the current time step, it operates in online mode, executing the action generated by the STLF model. If communication fails—due to packet loss, congestion, or delay—the UAV switches to offline mode, where it follows a predefined mobility strategy based on a local Gaussian profit map. This map integrates both exploration and tracking incentives, allowing the UAV to continue mission-critical behavior without central guidance.

The socket interface ensures that both simulators remain synchronized throughout the mission duration. Each simulation step in Python corresponds to a fixed time interval in NS-3, preserving temporal consistency between the mobility and network layers. This co-simulation framework allows us to evaluate the robustness of the online policy under varying network conditions, providing a more realistic assessment of swarm performance in communication-constrained environments.

5. Experiment

5.1. Experimental Setup

Experiments were implemented in Python 3.9 using the PyTorch 2.9.1 deep learning framework and trained on an NVIDIA V100 GPU. The network simulation component was deployed on a VMware® Workstation 16 Pro virtual machine (version 16.2.3) running Ubuntu 22.04.2 LTS. The NS-3 network simulator (version 3.44) was used to emulate wireless communication, including congestion, packet loss, and latency effects, through its built-in Wi-Fi and LTE modules. The Python-based STLF environment and NS-3 were synchronized via TCP sockets to ensure consistent discrete-time communication and control cycles throughout each simulation episode.

Table 1 outlines the simulation parameters used to instantiate the CMOMMT scenario. The search area is defined as a

grid containing 60 targets. UAV swarm sizes are configured as 15, 20, and 30, corresponding to UAV-to-target ratios of 1:4, 1:3, and 1:2, respectively. Observation radii are specified as 12 (small), 18 (medium), and 24 (large) cells. UAVs and targets move at maximum speeds of 3 and 1 cells per time step, respectively. Each simulation runs for 500 time steps. All results are averaged over five independent trials to reduce stochastic variance introduced by random initialization and transmission timing.

In the NS-3 configuration, UAVs communicate with the ground base station over Wi-Fi (IEEE 802.11n) with a fixed transmission power of 10 dBm, with 20 MHz. Each UAV transmits one UDP packet of size 1024 Bytes per time step, enabling accurate modeling of congestion and packet loss under high-density scenarios.

For Gaussian smoothing used in input maps, the standard deviation is defined based on the input type: in the UAV’s position map, is set to the UAV’s maximum movement range per time step; in the following value map, equals the UAV’s observation radius; and in the unobserved target position map, is set to 1.5 times the UAV’s observation radius. This design ensures that each input map accurately represents its respective spatial influence and observation uncertainty.

5.2. Evaluation Metrics

To quantitatively evaluate the performance of CSOOC, we adopt two categories of metrics:

- (1)

Task-level metrics (CMOMMT performance): The primary objective metric is the Average Observation Rate (AOR), defined as the ratio between the total number of targets observed at each time step and the total number of targets in the environment. A higher AOR reflects better overall swarm coverage and tracking efficiency across the mission.

- (2)

Network-level metrics (communication quality): To characterize the impact of network conditions on swarm coordination, we measure:

Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR): the percentage of successfully received packets at the GBS over the total transmitted packets.

Latency: the average end-to-end transmission delay for packets sent from UAVs to the GBS.

Jitter: the variation in packet arrival time, indicating the stability of the wireless link.

These metrics jointly capture both the mission performance and the underlying network reliability, enabling a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed framework under different communication conditions.

5.3. Validation with NS-3 Network Simulation

To illustrate the performance degradation caused by communication impairments, a relatively small-scale configuration is adopted, consisting of 15 UAVs with an observation radius of 12 units.

Figure 7 illustrates the average observation rate curves under this setting. For completeness,

Figure 7 also visualizes the standard deviation of each curve as a shaded region. The SD values are 0.76% for GKA with NS-3, 0.78% for GKA without NS-3, 1.56% for STLF with NS-3, and 1.16% for STLF without NS-3.

In the lines with NS-3, both the STLF and the GKA exhibit stable tracking performance, yet a clear performance gap remains. GKA, benefiting from complete global information, consistently generates near-optimal assignments with a higher observation rate. In contrast, STLF, although able to approximate the expert strategy through knowledge transfer, achieves slightly lower performance due to partial observability constraints.

When the NS-3 network simulation is integrated into the mission workflow, the overall performance declines. Since all UAVs transmit their status simultaneously at each discrete time step, network congestion, packet collisions, and additional delays occur. These impairments particularly affect those two methods, where unstable communication leads to reduced accuracy of coordinated decisions, thereby lowering the average observation rate compared to the ideal case. This experiment also verifies that our socket-based co-simulation mechanism successfully bridges the Python-based CMOMMT environment and the NS-3 network simulation. The observed degradation in both network quality and observation performance is fully consistent with expectations, confirming the correctness and effectiveness of the integration.

Table 2 reports the network statistics. It can be observed that the PDR is below 100% for both methods, with values of 75.35% for GKA and 71.91% for STLF. Meanwhile, the average latency remains around 5 ms, and the jitter is measured at 3.26 ms and 3.61 ms, respectively. These results suggest that although the network is still operational, packet loss and jitter have a direct negative impact on centralized coordination, thus reducing overall tracking performance.

In summary,

Figure 7 and

Table 2 jointly demonstrate that: (1) under ideal communication, GKA consistently outperforms STLF; (2) once realistic network effects are introduced, both algorithms experience performance degradation; and (3) the proposed Python–NS-3 socket-based co-simulation framework accurately reflects network-induced performance loss, validating its effectiveness for communication-aware UAV swarm coordination studies.

To wider validation of NS-3, we examine the impact of different channel bandwidths, we evaluate both methods under 10 MHz and 40 MHz settings, while keeping 20 MHz as the default configuration. The 20 MHz bandwidth is consistent with the standard IEEE 802.11 PHY configuration used throughout our NS-3 simulations, and it provides sufficient capacity for the experimental setup. As shown in

Table 3, performance remains similar when the bandwidth is increased to 40 MHz, confirming that the default setting is already adequate for the given traffic load. In contrast, reducing the bandwidth to 10 MHz leads to noticeable degradation in both PDR and AOR, indicating that the network becomes congested when channel capacity is limited.

5.4. Validation of STAR Congestion Control

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed STAR mechanism, we compare network performance and swarm tracking results with and without STAR under identical communication and mission parameters. Specifically, we conduct experiments using the 15 UAVs with an observation radius of 12 units setting and evaluate both communication metrics and swarm-level observation performance.

The results in

Table 4 clearly demonstrate that introducing the STAR congestion control mechanism significantly improves network reliability and swarm coordination performance. Specifically, the PDR increases from

to

for GKA and from

to

for STLF, indicating a substantial reduction in packet collisions and transmission failures. As network stability improves, the UAV swarm can receive more accurate coordination commands, leading to more effective target coverage and tracking.

Moreover, STAR stabilizes the network by effectively reducing jitter. For example, the jitter for GKA decreases from ms to ms, suggesting more predictable and less bursty transmission delays. Although the average latency slightly increases for both algorithms (e.g., from ms to ms for GKA), this is a reasonable trade-off considering the significant gains in delivery reliability and stability. The additional delay stems from the temporal stratification component of STAR, which intentionally staggers UAV transmissions to reduce collisions.

Overall, these findings validate the effectiveness of the proposed STAR congestion control mechanism. By jointly applying temporal desynchronization and channel reservation, STAR enhances network stability and improves swarm coordination performance under dense communication scenarios.

5.5. Validation of Offline Action Within CSOOC

To isolate and evaluate the contribution of offline action within the proposed CSOOC, we conduct controlled experiments under communication uncertainty. These experiments are performed using the same configuration as the network validation experiment—15 UAVs with an observation radius of 12 units.

When communication feedback from the GBS is lost, UAVs operating under CSOOC transition from online mode to the offline action module, which is driven by Gaussian-based local profit maps. Rather than stalling or performing random movements, each UAV makes autonomous mobility decisions based on its own historical observations, dynamically balancing between target following and exploratory search. This design provides behavioral continuity in the absence of centralized guidance, maintaining effective coverage over moving targets.

As shown in

Table 5, introducing offline actions leads to a clear improvement in tracking performance. For the GKA baseline, the AOR increases from

to

, while for STLF, it increases from

to

. The PDR also improves, reflecting the more adaptive behavior of UAVs during periods of unstable communication.

Figure 8 further illustrates how the average observation rate evolves over time, showing improvements for both GKA and STLF when offline action is enabled.

These results highlight the critical role of the offline action module in CSOOC:

It preserves coordinated swarm behavior through local decision-making, even when global control is temporarily unavailable.

It ensures graceful performance degradation instead of abrupt mission failure during communication disruptions.

It provides a bridge between online and offline modes, maintaining strategy consistency with the STLF policy.

In summary, the offline module acts as an essential behavioral backbone of the CSOOC framework, enabling UAV swarms to maintain robust observation performance under communication uncertainty without requiring external intervention.

5.6. Validation of the CSOOC and Comparative Analysis

To comprehensively validate the effectiveness of the proposed CSOOC framework, its performance is compared with several baseline algorithms under varying UAV maximum speeds and UAV-to-target ratios. In previous experiments, the contributions of the offline action mechanism and the STAR congestion control were individually examined; here, both components are jointly incorporated into all comparative methods to ensure fairness and isolate the effect of coordination strategy. To further assess the generalization capability of CSOOC, evaluations are conducted across different swarm scales (15, 20, and 30 UAVs) and observation radii (12, 18, and 24 cells), which effectively vary the UAV-to-target ratio and spatial coverage conditions within the CMOMMT environment. The benchmarking algorithms include:

GKA: A near-optimal heuristic that serves as the performance upper bound.

CSOOC: An enhanced version of STLF that incorporates a profit-driven mobility strategy and congestion control for communication-aware swarm coordination.

PAMTS [

5]: PAMTS is a profit-driven search-and-follow algorithm that coordinates UAVs using an observation profit metric, guiding each UAV at every time step toward the location with the highest expected profit.

PAMTS Follow [

5]: A variant of PAMTS that prioritizes target following upon detection. In contrast to the original PAMTS, which dynamically balances exploration and tracking, PAMTS Follow disables exploration by setting its weight to zero, improving observation consistency, especially in tasks requiring persistent surveillance, such as convoy protection or long-term monitoring.

A-CMOMMT [

4]: The earliest proposed solution to the CMOMMT task.

I-CMOMMT [

7]: Built upon A-CMOMMT, I-CMOMMT incorporates an idleness vector to account for the time since a region was last observed.

ROD (Reward-based Orientation Determination) [

8]: The ROD method is included for comparison, as it determines UAV movement directions based on reward evaluation to optimize cooperative target search efficiency.

VDP-ACO (Voronoi-based Dynamic Partition with Ant Colony Optimization) [

33]: A distributed framework that integrates Voronoi-based dynamic area partitioning and ant colony optimization under the distributed model predictive control architecture to enhance cooperative target search efficiency in dynamic environments.

The baselines selected in this study are representative used in CMOMMT research, covering classical, optimization-based, and learning-enhanced coordination strategies that directly address the characteristics of the multi-target tracking task. While DRL coordination algorithms are also of interest, our focus here is to evaluate CSOOC against task-specific and domain-relevant approaches. Incorporating DRL-based coordination methods constitutes a meaningful extension for future work.

As shown in

Figure 9 and

Table 6, the average observation rate of all methods increases consistently with both the number of UAVs and the observation radius. This trend aligns with expectations, as larger swarms and wider sensing ranges allow broader spatial coverage and more frequent target detections. Across all configurations, the gap between methods gradually narrows with increasing swarm size, reflecting the diminishing marginal benefit of coordination when coverage becomes saturated. Nevertheless, distinct performance hierarchies remain evident across methods.

The proposed CSOOC demonstrates stable and superior performance across all tested configurations. By integrating a profit-driven offline module and the STAR congestion control mechanism, CSOOC effectively maintains high observation rates under both sparse and dense swarm conditions. Compared to the original STLF, CSOOC exhibits stronger adaptability to varying UAV–target ratios, sustaining coordinated behavior even when communication intermittency occurs. Its consistent improvement across all radii highlights the framework’s capability to seamlessly couple centralized and decentralized decision-making under communication uncertainty.

In contrast, traditional heuristic approaches show limited robustness. PAMTS and A-CMOMMT depend heavily on parameter tuning and pre-defined heuristics, which restrict their adaptability when the environment scale changes. PAMTS Follow and ROD display strong behavioral biases—favoring tracking and exploration respectively—resulting in poor balance between persistent observation and spatial exploration. I-CMOMMT achieves moderate improvements by incorporating idleness awareness but remains constrained by the lack of communication feedback modeling. VDP-ACO exhibits fluctuating results, performing competitively in medium-scale cases but losing effectiveness in dense scenarios due to its distributed optimization overhead.

Quantitatively, CSOOC achieves an average observation rate of 39.7% across all parameter configurations, surpassing other baseline algorithms by 4.4–11.13%. These results confirm that CSOOC not only sustains stable coordination under communication constraints but also scales efficiently across different swarm sizes and sensing ranges, establishing it as a robust and generalizable solution for real-world CMOMMT tasks.

The network performance metrics summarized in

Table 7 further validate the effectiveness of the STAR congestion control mechanism integrated into all methods. Compared with the corresponding results in

Table 4 (without STAR), every algorithm exhibits noticeable improvements in packet delivery ratio (PDR), latency, and jitter, confirming that STAR effectively mitigates transmission contention and stabilizes network behavior. The average PDR values increase by 13.68–21.48% across all configurations, while both latency and jitter decrease, reflecting more reliable and smoother uplink communication between UAVs and the ground base station. To avoid enumerating all entries of

Table 7, we highlight the key trends that summarize the overall network behavior. The STAR mechanism consistently maintains a high packet delivery ratio, typically above 85–90% across different swarm sizes and observation radii. This indicates that STAR effectively mitigates congestion and improves communication stability in different UAV numbers. CSOOC keeps the end-to-end latency below 10 ms in all tested configurations, demonstrating that the framework preserves real-time responsiveness under varying network loads.

It is noteworthy that the GKA and CSOOC do not always achieve the absolute best network metrics among all tested methods. This variation, however, is not a limitation of the proposed framework but rather a result of spatial topology factors. Since the ground base station is located at the center of the environment (), UAVs positioned closer to the center experience more stable connections, while those distributed toward the map boundaries suffer from weaker signal strength and higher contention levels. Therefore, the overall network statistics are influenced by the spatial dispersion of UAVs and their instantaneous proximity to the base station rather than by the control algorithm itself.

Despite these variations, CSOOC maintains a consistently high PDR (above 90%) and low latency (below 10 ms) across all swarm configurations. This stability ensures timely feedback for the online mode and reliable switching between online and offline behaviors during communication fluctuations. The results collectively demonstrate that STAR effectively enhances the underlying communication layer and that CSOOC can preserve robust coordination performance even when physical topology or link quality varies dynamically.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper presented CSOOC, a communication-state driven online–offline coordination framework for UAV swarm multi-target tracking under realistic network conditions. Building upon the foundation of the STLF architecture, CSOOC introduces two critical extensions: a profit-driven offline action module for autonomous control during communication outages, and the STAR congestion control mechanism for maintaining uplink stability in dense swarm environments. By dynamically coupling swarm decision-making with network communication states, CSOOC achieves robust, adaptive coordination capable of sustaining high observation performance even under imperfect connectivity.

Extensive experiments conducted through a Python–NS-3 co-simulation platform demonstrated the framework’s effectiveness and generalization capability. Results show that CSOOC consistently outperforms baseline algorithms across diverse configurations of UAV counts, observation radii, and target densities. The integration of STAR improves packet delivery ratios by more than 15% on average, while the offline module ensures behavioral continuity during transient link failures. These findings collectively verify that communication-aware coordination and adaptive control can bridge the gap between algorithmic efficiency and practical UAV swarm deployment in real-world IoT sensing environments. Beyond simulation, CSOOC is well-suited for deployment in practical scenarios where communication quality varies over time. Examples include large-scale agricultural monitoring, disaster response operations, persistent environmental surveillance, and long-range infrastructure inspection, where uplink congestion and intermittent connectivity frequently occur. The STAR mechanism can stabilize packet delivery under these conditions, while the online–offline switching logic enables the swarm to maintain coordinated behavior even during temporary communication loss. Future work will focus on extending the CSOOC framework to decentralized communication architectures and heterogeneous UAV platforms, as well as integrating learning-based congestion prediction and adaptive bandwidth allocation to further enhance scalability and robustness in large-scale aerial networks.