Parameter Identification of SiC MOSFET Half-Bridge Converters Using a Multi-Objective Optimization Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Multiple objectives: The identification of parasitic inductance and capacitance is often a multi-objective problem, with conflicting objectives such as the minimization of the difference between the switching transient profiles of gate-source voltage, drain-source voltages, and drain current, carried out by using the equivalent circuit model including the estimated parasitic parameters and those measured by some preliminary experimental tests. MOGAs can optimize multiple objectives simultaneously, providing a trade-off between conflicting objectives.

- Non-linear relationships: Parasitic inductance and capacitance of SiC MOSFETs have non-linear relationships with the other quantities of the system, such as switching frequency and operating temperature of the power converter. MOGAs can handle complex and non-linear relationships between parameters, making them well-suited for this task.

- No gradient information required: MOGAs do not require gradient information on the objectives, making them suitable for identifying parameters in systems where the gradient information is difficult to obtain or unknown.

- Global optimization: MOGAs have the ability to search the entire design space and find the global optimum, rather than just a local optimum. This is important for identifying parameters in SiC MOSFETs, as the parasitic inductance and capacitance can significantly impact the system’s performance.

- Robustness to initial conditions: MOGAs are robust to initial conditions and are not susceptible to being trapped in local optima, making them well-suited for identifying parameters in complex systems.

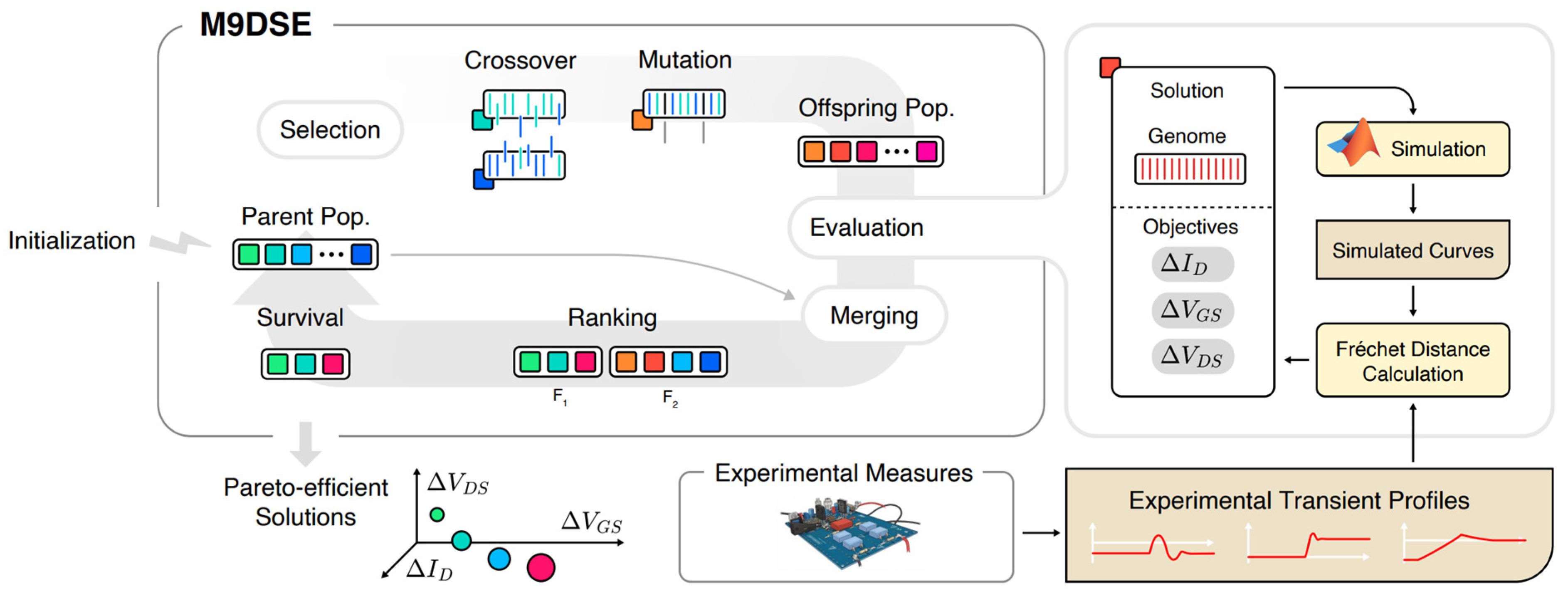

2. Parameters Identification Based on Multi-Objective Optimization Algorithm

- Initialization: Create an initial population of candidate solutions randomly or using heuristics.

- Evaluation: Evaluate the fitness of each candidate solution in the population using multiple objectives.

- Pareto dominance: Compare the candidate solutions based on their fitness values and identify the non-dominated solutions, also known as the Pareto front.

- Strength calculation: Calculate the strength value for each solution, which measures the solution’s proximity to other solutions in the Pareto front.

- Environmental selection: Select solutions for the next generation based on their strength values and the number of solutions in the population. Solutions with lower strength values are more likely to be discarded.

- Variation: Apply genetic operators such as crossover and mutation to generate new offspring from the selected solutions.

- Repeat: Repeat the evaluation, Pareto dominance, strength calculation, environmental selection, and variation steps until a stopping criterion is met.

- Output: The final set of non-dominated solutions represents the Pareto front, which is the output of the SPEA2 algorithm.

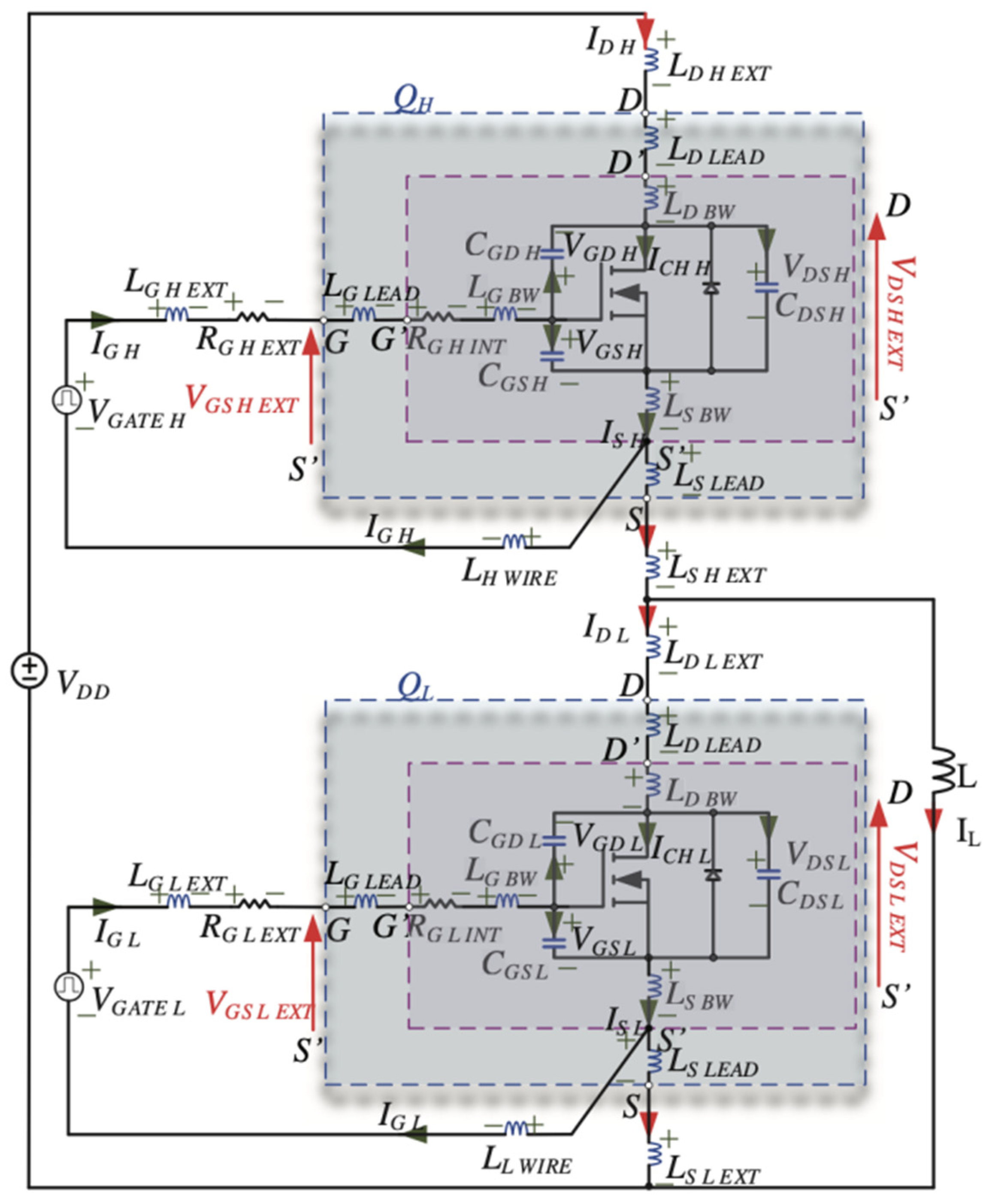

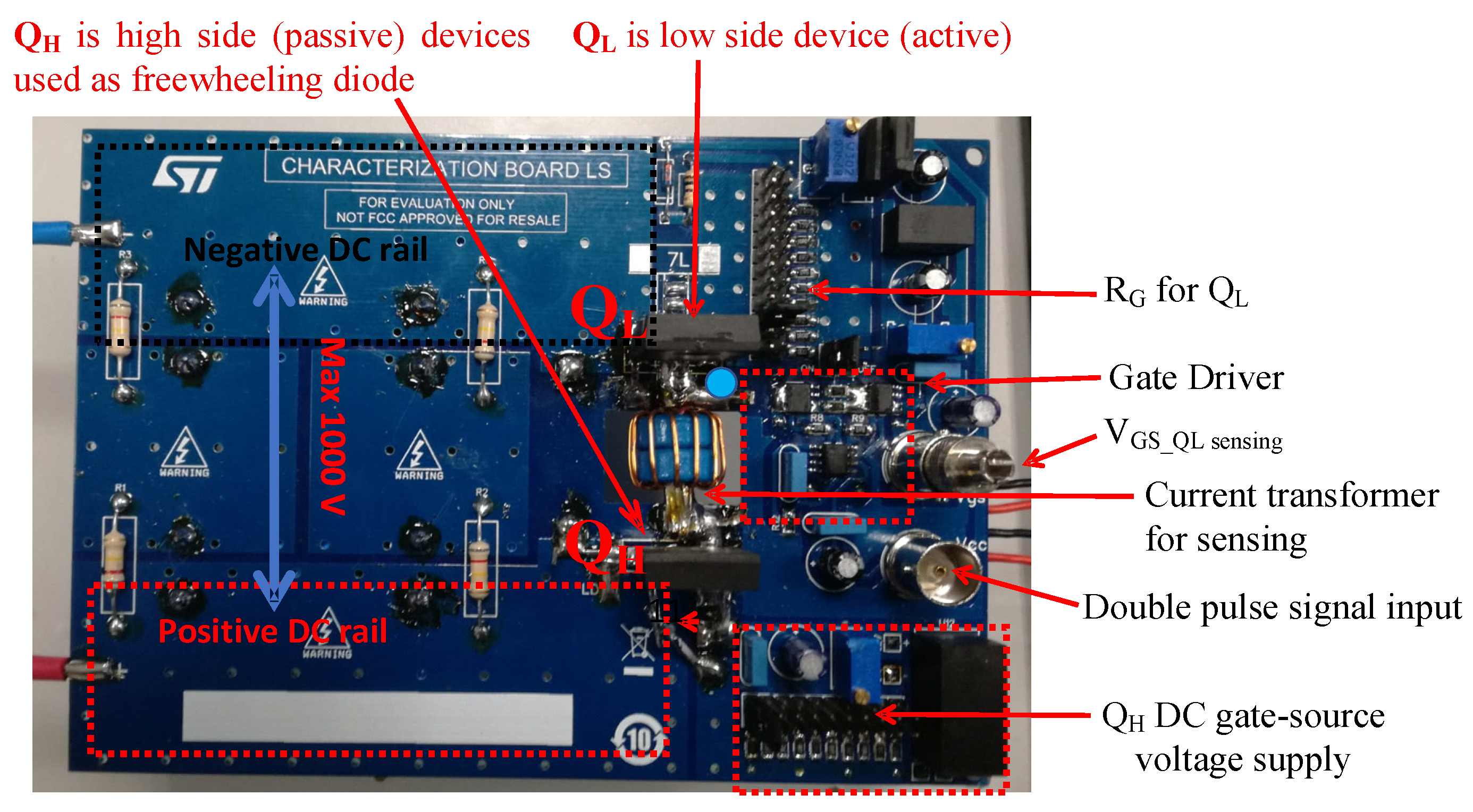

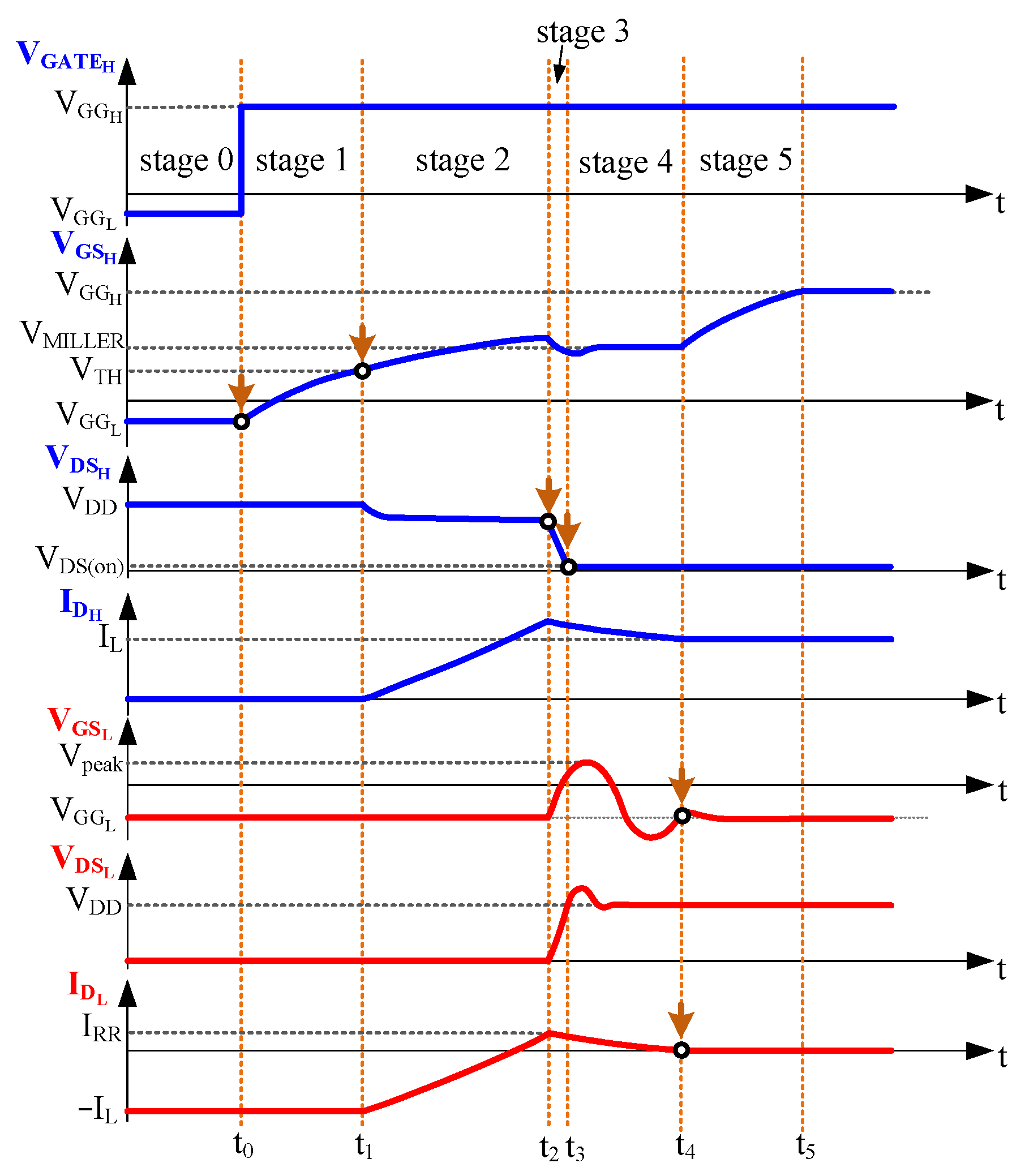

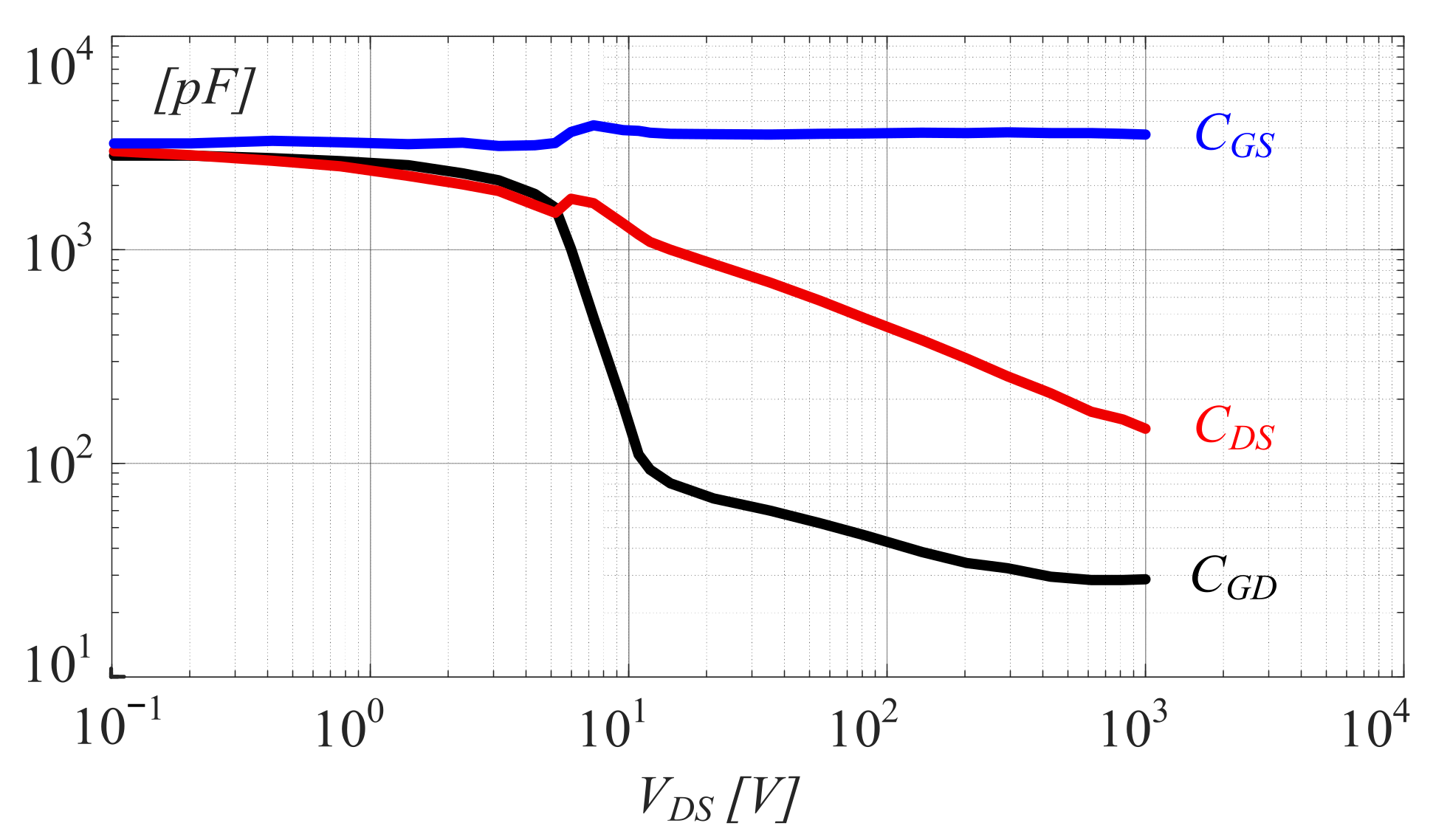

3. Turn-On Switching Modeling of SiC MOSFETs in a Half-Bridge Topology

4. Problem Statement

5. The M9DSE Software

5.1. Inputs

- A set of n values chosen by the user for each of the 14 parameters of the problem, also known as the configuration space;

- A seed, used for random execution;

- A size for the initial population, necessarily divisible by 2;

- A value between 0 and 1 for the probability of crossover;

- A value between 0 and 1 for the probability of mutation;

- The number of generations to explore.

5.2. Genetic Process

- (1)

- Random generation of the starting population:

- (a)

- Generation of an individual composed of its 14 parameters with respective values randomly taken from the configuration space;

- (b)

- A simulation on MATLAB of the generated individual and the assignment of , and based on the comparison with experimental tests;

- (c)

- Repetition from (a) until the number of individuals chosen for the initial population is generated.

- (2)

- Application of the crossover and mutation operators to the current population based on respective probabilities.

- (3)

- Simulation in MATLAB of any individuals generated in the previous step, with the relative assignment of the , , and .

- (4)

- Selection of non-dominated individuals in the current population and elimination of any dominated individual.

- (5)

- Repetition starting from step (2) until the chosen number of generations is reached.

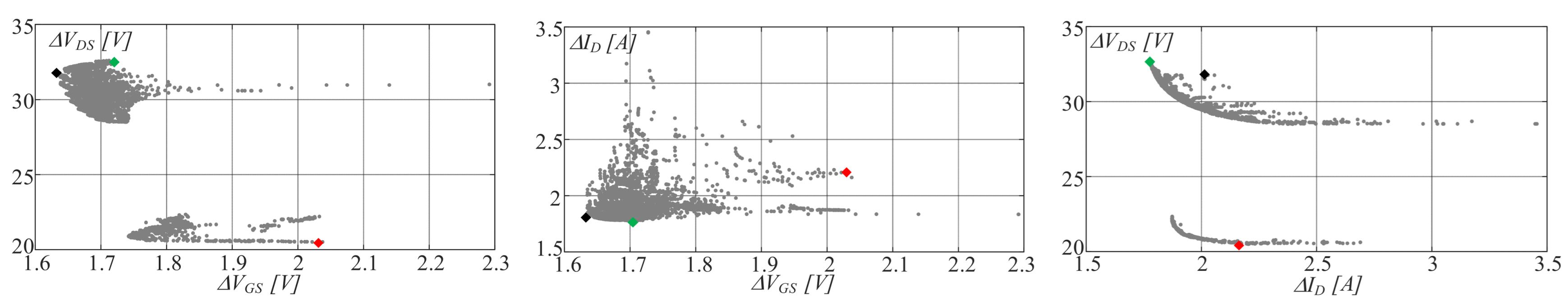

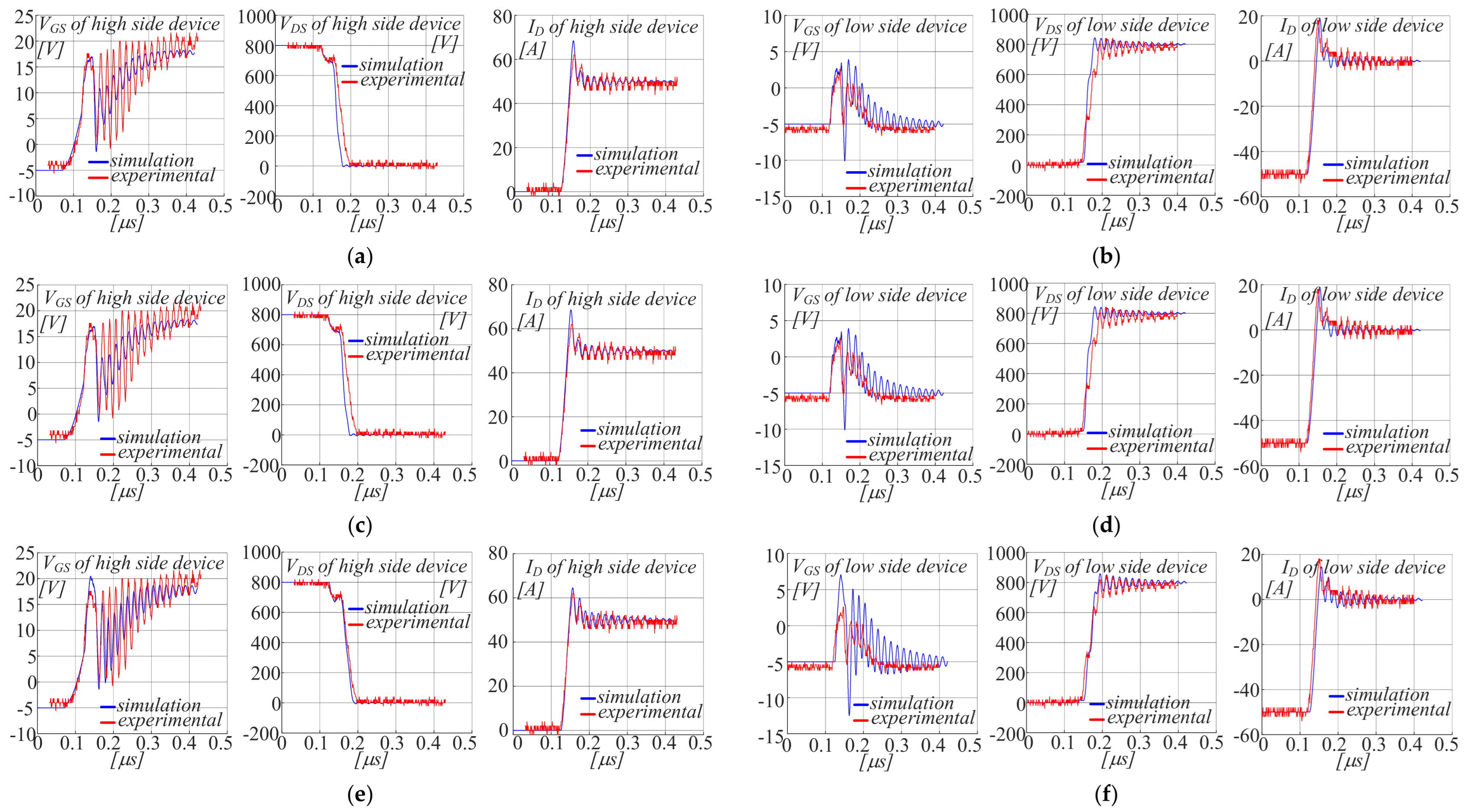

5.3. Results of the Process

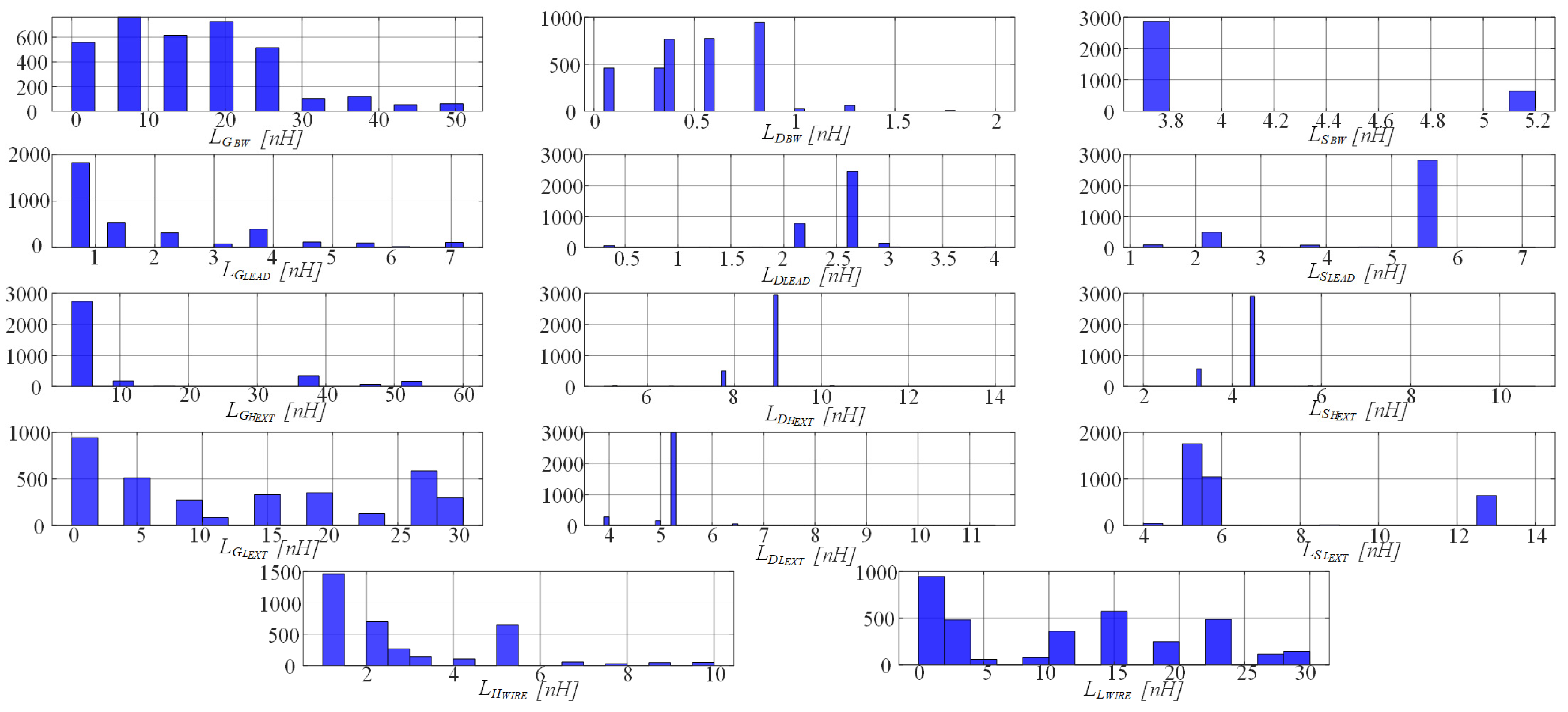

6. Parametric Exploration with M9DSE

6.1. Population

6.2. Total Generations

6.3. Configuration Space

6.4. Results

6.5. Selecting the Optimal Solutions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- She, X.; Huang, A.Q.; Lucia, O.; Ozpineci, B. Review of silicon carbide power devices and their applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 8193–8205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deboy, G. Shaping the transition from Si-based power devices to SiC MOSFETs and GaN HEMTs. In Proceedings of the 2022 24th European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications (EPE’22 ECCE Europe), Hannover, Germany, 5–9 September 2022; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Yuan, X.; Wu, X.; Shi, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. Performance Evaluation of High-Power SiC MOSFET Modules in Comparison to Si IGBT Modules. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 1181–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-J.; Kusic, G.L.; Reed, G.F. Comparative PSCAD and Matlab/Simulink simulation models of power losses for SiC MOSFET and Si IGBT devices. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Power and Energy Conference at Illinois, Champaign, IL, USA, 24–25 February 2012; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, L.F.S.; Lefranc, P.; Jeannin, P.-O.; Sarrazin, B. Review on SiC-MOSFET devices and associated gate drivers. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), Lyon, France, 19–22 February 2018; pp. 824–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risseh, A.E.; Nee, H.-P.; Kostov, K. Electrical performance of directly attached SiC power MOSFET bare dies in a half-bridge configuration. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 3rd International Future Energy Electronics Conference and ECCE Asia (IFEEC 2017—ECCE Asia), Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 3–7 June 2017; pp. 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Xiao, L.; Zhao, J.; Chen, G. Physical analysis and modeling of the nonlinear Miller capacitance for SiC MOSFET. In Proceedings of the IECON 2017—43rd Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Beijing, China, 29 October–1 November 2017; pp. 1411–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadik, D.-P.; Kostov, K.; Colmenares, J.; Giezendanner, F.; Ranstad, P.; Nee, H.-P. Analysis of Parasitic Elements of SiC Power Modules with Special Emphasis on Reliability Issues. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2016, 4, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMarino, C.M.; Mouawad, B.; Johnson, C.M.; Boroyevich, D.; Burgos, R. 10-kV SiC MOSFET power module with reduced common-mode noise and electric field. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 6050–6060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulvirenti, M.; Montoro, G.; Nania, M.; Scollo, R.; Scelba, G.; Cacciato, M.; Scarcella, G.; Salvo, L. Analysis of transient gate–source overvoltages in silicon carbide MOSFET power devices. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Portland, OR, USA, 23–27 September 2018; pp. 1895–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wong, T.T.Y.; Shen, Z.J. A New Characterization Technique for Extracting Parasitic Inductances of SiC Power MOSFETs in Discrete and Module Packages Based on Two-Port S-Parameters Measurement. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2018, 33, 9819–9833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noppakunkajorn, J.; Han, D.; Sarlioglu, B. Analysis of High-Speed PCB with SiC Devices by Investigating Turn-Off Overvoltage and Interconnection Inductance Influence. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2015, 1, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Wang, Z.; Liang, Z.; Wang, F. Electrical Performance Advancement in SiC Power Module Package Design with Kelvin Drain Connection and Low Parasitic Inductance. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2019, 7, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, T.; Yang, F.; Ma, D.; Zhao, C.; Pei, Y.; Gan, Y. Cu Clip-Bonding Method with Optimized Source Inductance for Current Balancing in Multichip SiC MOSFET Power Module. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 7952–7964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guacci, M.; Bortis, D.; Kovačević-Badstübner, I.F.; Grossner, U.; Kolar, J.W. Analysis and design of a 1200 V All-SiC planar interconnection power module for next generation more electrical aircraft power electronic building blocks. CPSS Trans. Power Electron. Appl. 2017, 2, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, A.B.; Munk-Nielsen, S.; Uhrenfeldt, C. Overview of Digital Design and Finite-Element Analysis in Modern Power Electronic Packaging. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 10892–10905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBoi, B.T.; Lemmon, A.N.; McPherson, B.; Passmore, B. Improved Methodology for Parasitic Analysis of High-Performance Silicon Carbide Power Modules. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 12415–12425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, A.J.; Hontz, M.R.; Khanna, R.; Lemmon, A.N.; DeBoi, B.T.; Shahabi, A. An Automated Model Tuning Procedure for Optimizing Prediction of Transient and Dispersive Behavior in Wide Bandgap Semiconductor FETs. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 12252–12263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Peng, H.; Cheng, Z.; Liu, X.; Xin, Q.; Kang, Y.; Wu, J.; Chu, X. A Novel Power Loop Parasitic Extraction Approach for Paralleled Discrete SiC MOSFETs on Multilayer PCB. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2021, 9, 6370–6384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulvirenti, M.; Salvo, L.; Sciacca, A.G.; Scelba, G.; Cacciato, M. Modeling of SiC-MOSFET Converter Leg Including Parasitics of 518 Printed Circuit Board Layout and Device Packaging. In Proceedings of the 2020 22nd European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications 519 (EPE’20 ECCE Europe), Lyon, France, 7–11 September 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umetani, K.; Aikawa, K.; Hiraki, E. Straightforward Measurement Method of Common Source Inductance for Fast Switching Semiconductor Devices Mounted on Board. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 8258–8267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukunoki, Y.; Horiguchi, T.; Nakayama, Y.; Nishizawa, A.; Nakamura, Y.; Konno, K.; Kuzumoto, M.; Akagi, H. Modeling of a silicon-carbide MOSFET with focus on internal stray capacitances and inductances, and its verification. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), Tampa, FL, USA, 26–30 March 2017; pp. 2671–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornello, L.D.; Spitaleri, M.G.; Scarcella, G.; Cacciato, M. Analytical modeling of SiC-MOSFETs for parasitic parameter adjustment based on experimental data. Electr. Eng. 2025, 107, 15205–15215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leon-Aldaco, S.E.; Calleja, H.; Aguayo Alquicira, J. Metaheuristic Optimization Methods Applied to Power Converters: A Review. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2015, 30, 6791–6803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yang, X.; Ye, J.; Liu, G. Novel Prognostics for IGBTs Using Wire-Bond Contact Degradation Model Considering On-Chip Temperature Distribution. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 4411–4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| 1200 V | |

| @ , , | 21 mΩ |

| (Maximum Operative Range) | −10 V/+22 V |

| @ , | 2.45 V |

| Parameter | Range | Default Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1–50 nH | 2 nH | 1 nH | |

| 0.1–2 nH | 0.38 nH | 0.575 nH | |

| 1–12 nH | 3 nH | 3.75 nH | |

| 0.7–7 nH | 3 nH | 0.7 nH | |

| 0.4–4 nH | 3 nH | 2.65 nH | |

| 0.7–7 nH | 3 nH | 5.425 nH | |

| 4–60 nH | 6 nH | 4 nH | |

| 4–14 nH | 5 nH | 9 nH | |

| 2–12 nH | 6 nH | 3.25 nH | |

| 1–30 nH | 6 nH | 4.625 nH | |

| 4–14 nH | 5 nH | 5.25 nH | |

| 4–14 nH | 6 nH | 5.25 nH | |

| 1–10 nH | 2.5 nH | 1 nH | |

| 1–30 nH | 2.5 nH | 15.5 nH |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monteleone, S.; Tornello, L.D.; Patti, D.; Scelba, G.; Palesi, M.; Russo, E.; Pulvirenti, M.; Salvo, L. Parameter Identification of SiC MOSFET Half-Bridge Converters Using a Multi-Objective Optimization Method. Electronics 2025, 14, 4458. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224458

Monteleone S, Tornello LD, Patti D, Scelba G, Palesi M, Russo E, Pulvirenti M, Salvo L. Parameter Identification of SiC MOSFET Half-Bridge Converters Using a Multi-Objective Optimization Method. Electronics. 2025; 14(22):4458. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224458

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonteleone, Salvatore, Luigi Danilo Tornello, Davide Patti, Giacomo Scelba, Maurizio Palesi, Enrico Russo, Mario Pulvirenti, and Luciano Salvo. 2025. "Parameter Identification of SiC MOSFET Half-Bridge Converters Using a Multi-Objective Optimization Method" Electronics 14, no. 22: 4458. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224458

APA StyleMonteleone, S., Tornello, L. D., Patti, D., Scelba, G., Palesi, M., Russo, E., Pulvirenti, M., & Salvo, L. (2025). Parameter Identification of SiC MOSFET Half-Bridge Converters Using a Multi-Objective Optimization Method. Electronics, 14(22), 4458. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224458