Signal Modulation Recognition Based on DRSLSTM Neural Network

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Modulation Technologies

2.1.1. ASK Technologies

2.1.2. PSK Technologies

2.1.3. Amplitude Modulation (AM) and Frequency Modulation (FM)

2.2. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Neural Networks

2.2.1. Memory Cell

2.2.2. Gating Mechanisms

- (a)

- Long-Term Dependency Capture: By regulating the flow of information through gating mechanisms, LSTM effectively mitigates the vanishing gradient problem. For example, in signal modulation recognition, where the modulation mode of a signal is determined by the temporal correlation of its I/Q components over multiple time steps, LSTM can retain the phase and amplitude trends of the signal over hundreds of time steps, whereas traditional RNNs would lose this information due to gradient decay.

- (b)

- Robustness to Noise: The forget gate of LSTM can adaptively discard noise components in the sequence by assigning low weights to irrelevant fluctuations. This inherent noise suppression capability makes LSTM more suitable for low SNR scenarios compared to shallow feature extraction methods.

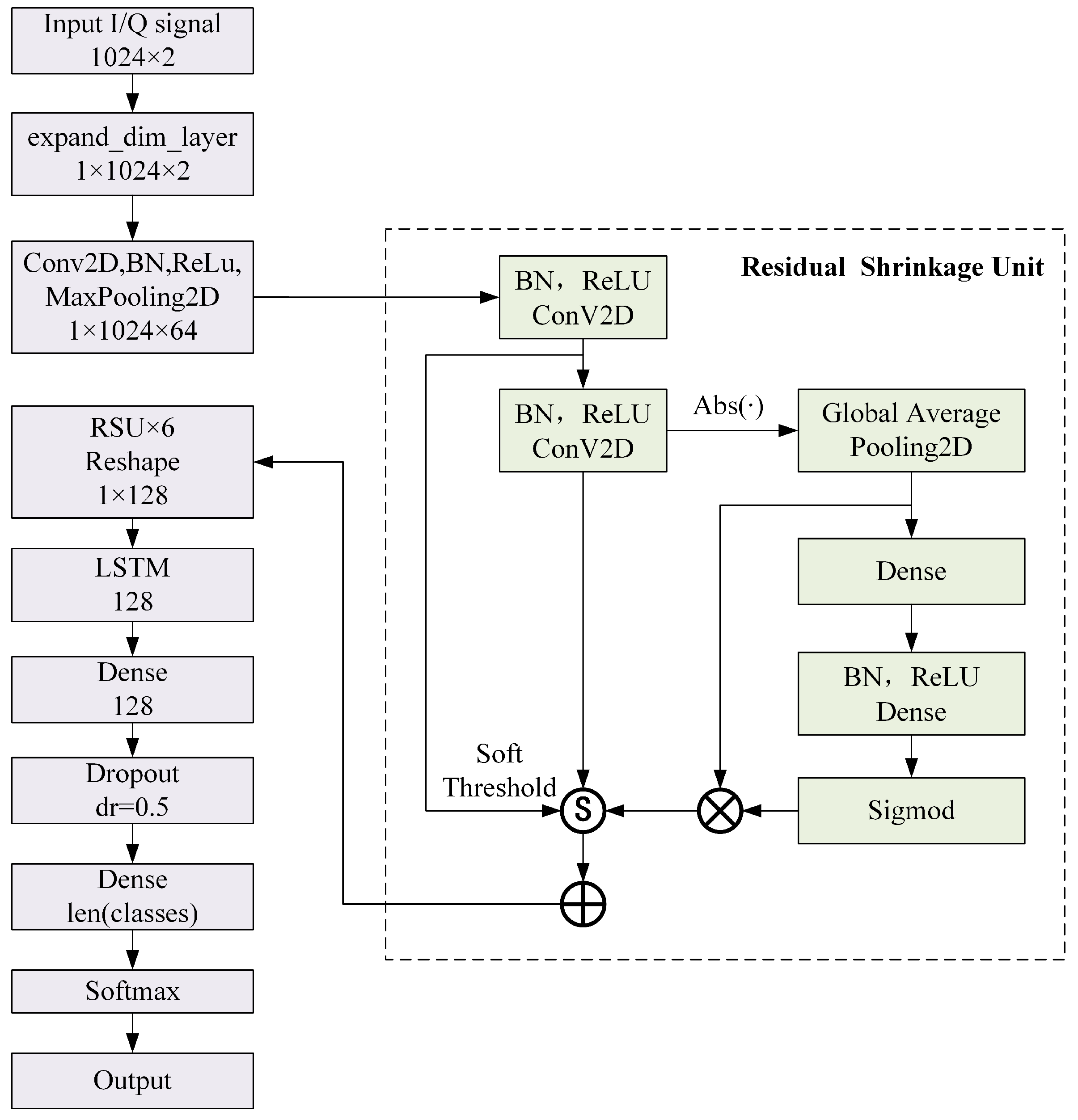

3. DRSLSTM Neural Network

3.1. DRSLSTM Model

3.2. Residual Shrinkage Unit

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Dataset and Experimental Environment

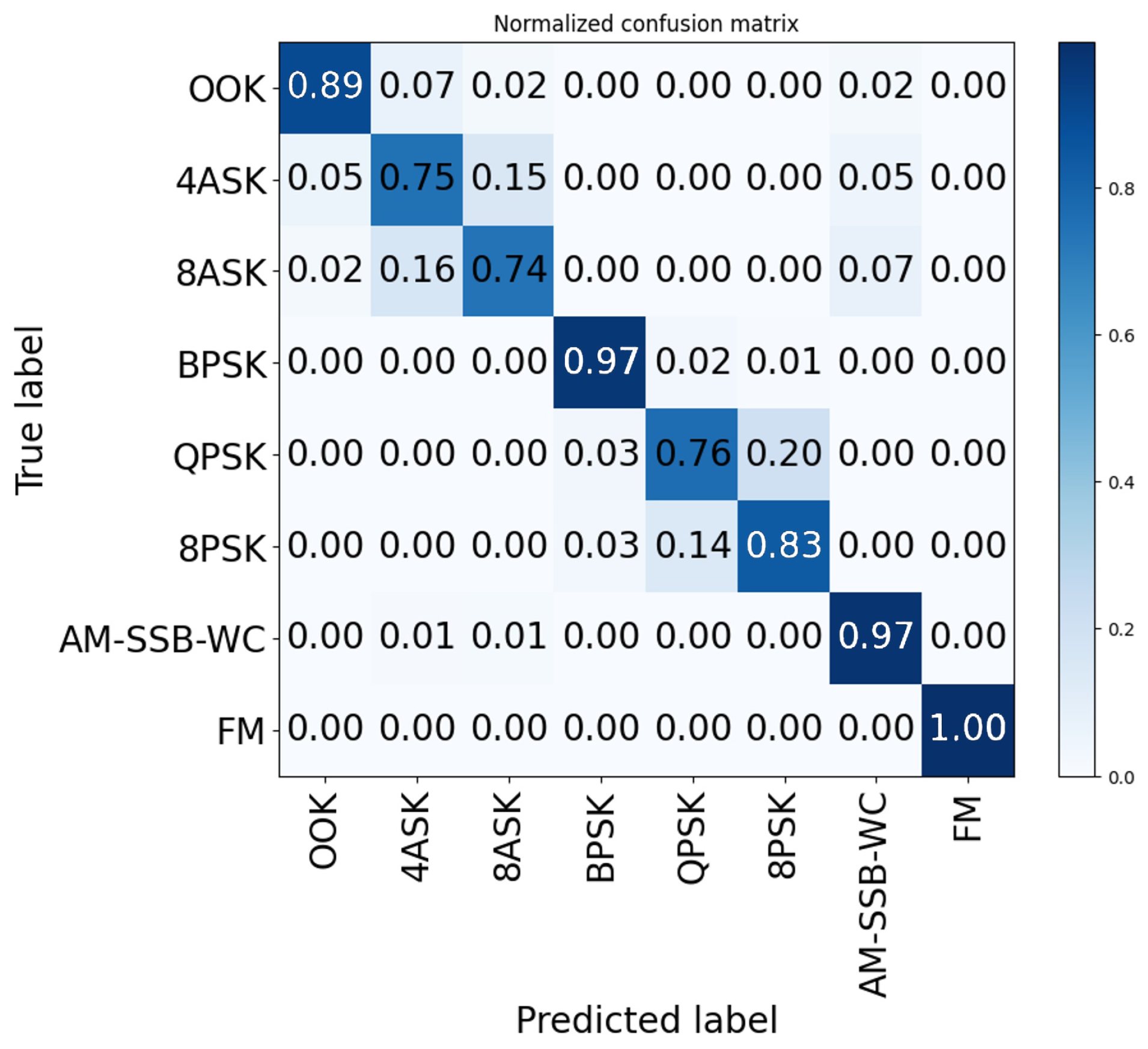

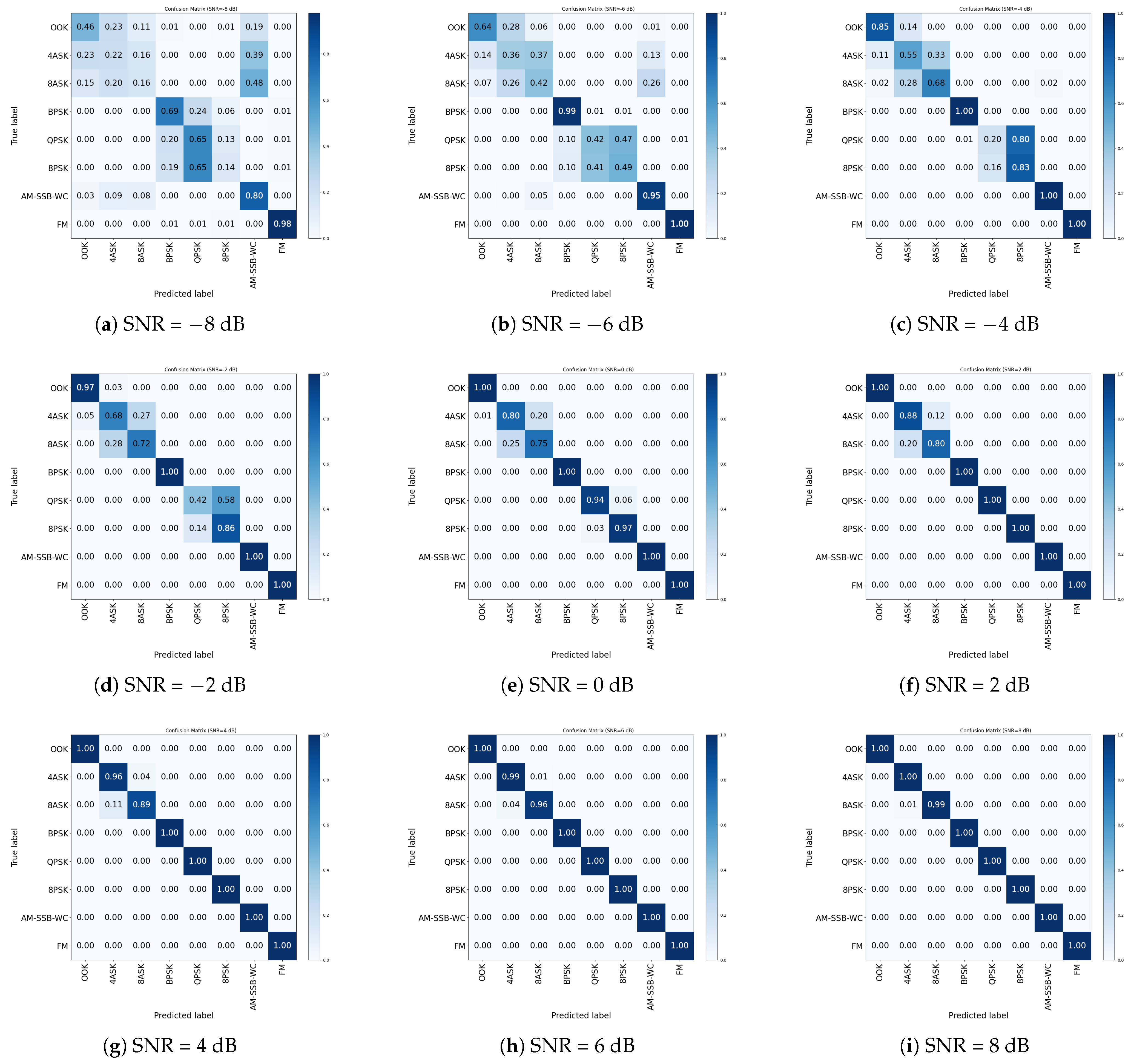

4.2. Results of DRSLSTM Model

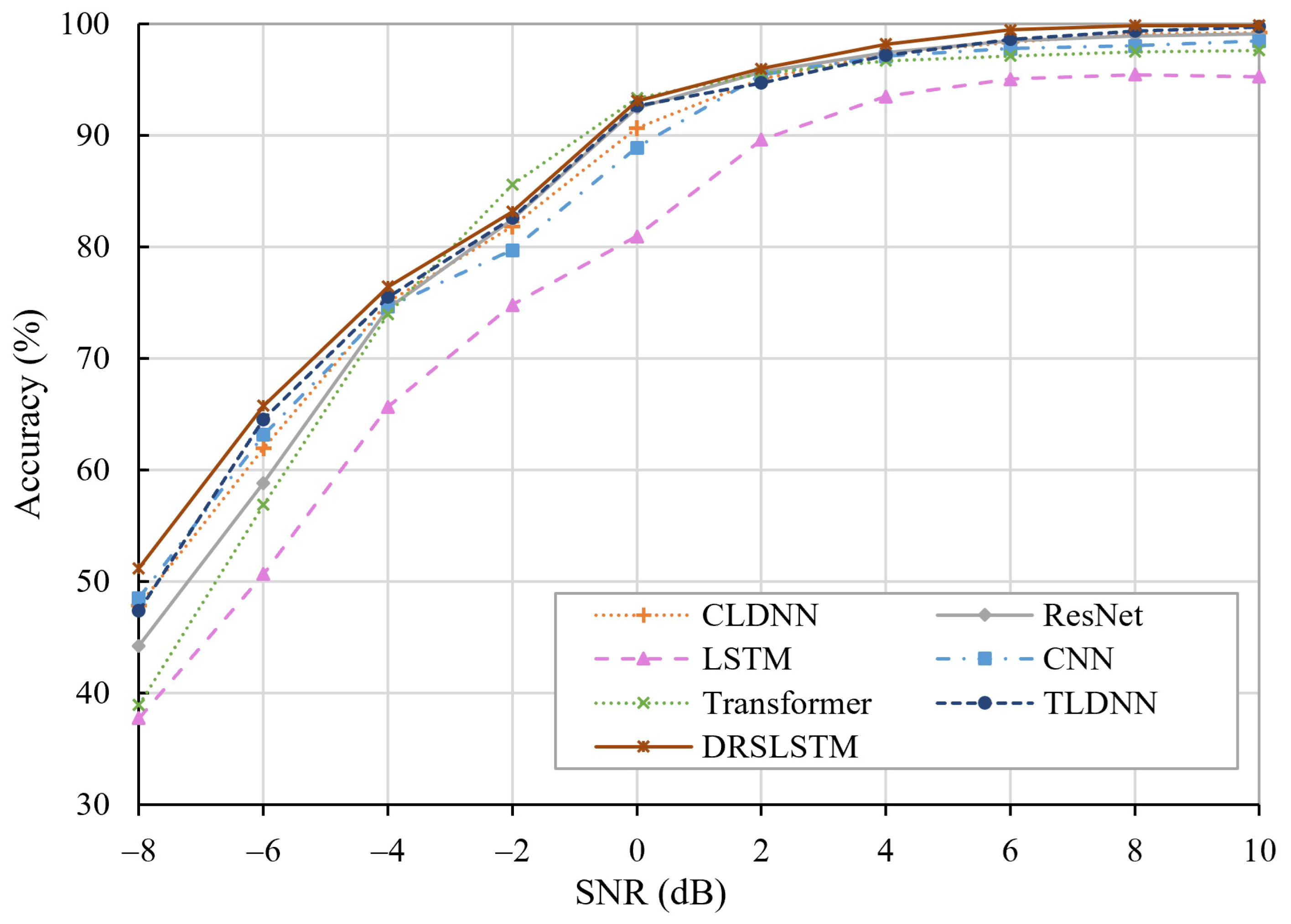

4.3. Comparison with Other Models

4.4. The Ablation Study of DRSLSTM

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zheng, Q.; Tian, X.; Yu, L.; Elhanashi, A.; Saponara, S. Recent Advances in Automatic Modulation Classification Technology: Methods, Results, and Prospects. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2025, 2025, 4067323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; He, J.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Chang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Z. Generalized Automatic Modulation Classification for OFDM Systems Under Unseen Synthetic Channels. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 23, 11931–11941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Zhang, X.; Chang, S.; Ren, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, J.; Cui, S. Joint Signal Detection and Automatic Modulation Classification via Deep Learning. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 23, 17129–17142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyston, J.; Bhattacharjea, R.; Stark, A. Complex-Valued Convolutions for Modulation Recognition Using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Communications Workshops (ICC Workshops), Dublin, Ireland, 7–11 June 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Dong, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Jiang, Q. Deep-Learning Hopping Capture Model for Automatic Modulation Classification of Wireless Communication Signals. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2023, 59, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Chen, J.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tan, L.; Liang, G. A New Time-Aware Collaborative Filtering Intelligent Recommendation System. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2019, 61, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Yu, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, T. A New Source-Filter Model Audio Bandwidth Extension Using High Frequency Perception Feature for IoT Communications. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2020, 32, e4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazar, M.A.; Odabasioglu, N.; Ensari, T.; Kavurucu, Y.; Sayan, O.F. Performance Analysis and Improvement of Machine Learning Algorithms for Automatic Modulation Recognition over Rayleigh Fading Channels. Neural Comput. Appl. 2018, 29, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Gao, F.; Li, Z.; Dobre, O.A. Low Complexity Automatic Modulation Classification Based on Order-Statistics. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2017, 16, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Wan, Q. Cyclic Feature-Based Modulation Recognition Using Compressive Sensing. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2017, 6, 402–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liang, W.; Yan, K.; Li, W.; Wang, K.I.K.; Ma, J.; Jin, Q. Edge-Enabled Two-Stage Scheduling Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning for Internet of Everything. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 3295–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, C.; Sun, W. Point-by-Point Feature Extraction of Artificial Intelligence Images Based on the Internet of Things. Comput. Commun. 2020, 159, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.; Prokopiw, W.; Chan, Y. Modulation Identification of Digital Signals by the Wavelet Transform. IEE Proc.—Radar Sonar Navig. 2000, 147, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walenczykowska, M.; Kawalec, A.; Krenc, K. An Application of Analytic Wavelet Transform and Convolutional Neural Network for Radar Intrapulse Modulation Recognition. Sensors 2023, 23, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Xu, X.; Liang, W.; Zeng, Z.; Yan, Z. Deep-Learning-Enhanced Multitarget Detection for End–Edge–Cloud Surveillance in Smart IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 12588–12596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, T.J.; West, N. Radio Machine Learning Dataset Generation with GNU Radio. Available online: https://pubs.gnuradio.org/index.php/grcon/article/view/11/10 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- O’Shea, T.J.; Corgan, J.; Clancy, T.C. Convolutional Radio Modulation Recognition Networks. In Proceedings of the Engineering Applications of Neural Networks, Aberdeen, UK, 2–5 September 2016; pp. 213–226. [Google Scholar]

- Erpek, T.; O’Shea, T.J.; Clancy, T.C. Learning a Physical Layer Scheme for the MIMO Interference Channel. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), Kansas City, MO, USA, 20–24 May 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea, T.J.; Roy, T.; West, N.; Hilburn, B.C. Demonstrating Deep Learning Based Communications Systems Over the Air In Practice. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Dynamic Spectrum Access Networks (DySPAN), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 22–25 October 2018; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G. Exponential Stability of Positive Recurrent Neural Networks with Multi-proportional Delays. Neural Process. Lett. 2019, 49, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, Z.; Tang, C. Modulation Recognition Algorithm Based on ResNet50 Multi-feature Fusion. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Intelligent Transportation, Big Data & Smart City (ICITBS), Xi’an, China, 27–28 March 2021; pp. 677–680. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, L.; Dou, W.; Hu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, J. A Context-Aware Service Evaluation Approach over Big Data for Cloud Applications. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 2020, 8, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daldal, N.; Yıldırım, Ö.; Polat, K. Deep Long Short-Term Memory Networks-Based Automatic Recognition of Six Different Digital Modulation Types under Varying Noise Conditions. Neural Comput. Appl. 2019, 31, 1967–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Yang, Q.; Jiao, X.; Niu, Y.; Ji, G. A Transformer-based CTDNN Structure for Automatic Modulation Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2021 7th International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC), Chengdu, China, 10–13 December 2021; pp. 159–163. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, S.; Fan, Y.; Wang, M.; Xu, Z.; Hou, S. A Complex-Valued Convolutional Fusion-Type Multi-Stream Spatiotemporal Network for Automatic Modulation Classification. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.T.; Cui, D.; Lou, S.T. Training Images Generation for CNN Based Automatic Modulation Classification. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 62916–62925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W. Anti-Interference Performance of QPSK Modulation and Demodulation Technology in Mobile Communication with MATLAB Simulation. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 5th International Conference on Electronic Technology, Communication and Information (ICETCI), Changchun, China, 23–25 May 2025; pp. 176–181. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Bhuiyan, M.Z.A.; Yang, X.; Wang, T.; Xu, X.; Hayajneh, T.; Khan, F. AntiConcealer: Reliable Detection of Adversary Concealed Behaviors in EdgeAI-Assisted IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 22184–22193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morohashi, I.; Sekine, N. Generation and Detection of FM-CW Signals in All-Photonic THz Radar Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 49th International Conference on Infrared, Millimeter, and Terahertz Waves (IRMMW-THz), Perth, Australia, 1–6 September 2024; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Hu, R.; Wang, X.; Tu, W.; Zhang, M. Nonlinear Prediction with Deep Recurrent Neural Networks for Non-Blind Audio Bandwidth Extension. China Commun. 2018, 15, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, A.; Guo, W.; Cui, Y.; Zhao, X.; Liu, L. Learning Deep Binaural Representations With Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Spontaneous Speech Emotion Recognition. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 23496–23505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Qiu, S.; Li, J. Modulation Recognition Method of Satellite Communication Based on CLDNN Model. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 30th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Kyoto, Japan, 20–23 June 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Y.; Lu, Z.; Zeng, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, J. Enhancing Automatic Modulation Recognition Through Robust Global Feature Extraction. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 4192–4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset Content | Parameter |

|---|---|

| Modulation Types | ‘OOK’, ‘4ASK’, ‘8ASK’, |

| ‘BPSK’, ‘QPSK’, ‘8PSK’, | |

| ‘AM-SSB-WC’, ‘FM’ | |

| SNR Range | −8 dB:2 dB:10 dB |

| Number of Samples | 327,680 |

| Sampling Frequency | 1 MHz |

| Sample Format | 1024 × 2 I/Q data |

| Roll-off Factor | 0.35 |

| Number of Samples per Symbol | 8 |

| Maximum Carrier Offset and Its Standard Deviation | 500 Hz, 0.01 Hz |

| Channel Fading Model | Rayleigh Fading |

| Network Training Hyperparameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Maximum Training Iterations | 200 |

| Batch Size | 512 |

| Initial Learning Rate | 0.001 |

| Learning Rate Decay Factor | 0.5 |

| Learning Rate Decay Patience Epochs | 4 |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Loss Function | CCE Loss |

| SNR (dB) | CLDNN | Resnet | LSTM | CNN | Transformer | TLDNN | DRSLSTM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −8 | 47.83% | 44.23% | 37.75% | 48.53% | 38.91% | 47.37% | 51.19% |

| −6 | 61.93% | 58.83% | 50.65% | 63.15% | 56.87% | 64.54% | 65.76% |

| −4 | 75.05% | 74.51% | 65.66% | 74.65% | 73.98% | 75.51% | 76.44% |

| −2 | 81.83% | 82.46% | 74.81% | 79.70% | 85.58% | 82.58% | 83.16% |

| 0 | 90.66% | 92.48% | 80.94% | 88.89% | 93.35% | 92.65% | 93.10% |

| 2 | 95.05% | 95.72% | 89.63% | 95.45% | 95.57% | 94.72% | 95.99% |

| 4 | 97.31% | 97.45% | 93.51% | 97.11% | 96.68% | 97.19% | 98.18% |

| 6 | 98.36% | 98.48% | 95.06% | 97.78% | 97.12% | 98.64% | 99.45% |

| 8 | 99.10% | 98.92% | 95.46% | 98.04% | 97.49% | 99.36% | 99.86% |

| 10 | 99.22% | 99.10% | 95.27% | 98.47% | 97.64% | 99.75% | 99.86% |

| Average | 84.63% | 84.20% | 77.87% | 84.18% | 83.31% | 85.23% | 86.30% |

| Dataset | CLDNN | Resnet | LSTM | CNN | Transformer | TLDNN | DRSLSTM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RML2016.01a | 56.07% | 61.33% | 59.12% | 57.14% | 60.54% | 62.82% | 62.91% |

| RML2018.01a | 84.63% | 84.20% | 77.87% | 84.18% | 83.31% | 85.23% | 86.30% |

| Model Configuration | Average Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|

| Full Model (RSU + LSTM) | 86.30 % |

| Without LSTM Module | 85.82% |

| Without RSU Module | 85.09% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tan, P.; Chen, D.; Zhou, K.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, S. Signal Modulation Recognition Based on DRSLSTM Neural Network. Electronics 2025, 14, 4424. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224424

Tan P, Chen D, Zhou K, Shen Y, Zhao S. Signal Modulation Recognition Based on DRSLSTM Neural Network. Electronics. 2025; 14(22):4424. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224424

Chicago/Turabian StyleTan, Ping, Dongxu Chen, Kaijun Zhou, Yi Shen, and Shen Zhao. 2025. "Signal Modulation Recognition Based on DRSLSTM Neural Network" Electronics 14, no. 22: 4424. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224424

APA StyleTan, P., Chen, D., Zhou, K., Shen, Y., & Zhao, S. (2025). Signal Modulation Recognition Based on DRSLSTM Neural Network. Electronics, 14(22), 4424. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14224424