1. Introduction

Over the past four decades, global energy consumption has more than doubled, rising from 270.5 EJ to 580 EJ, with approximately 85% of this demand still being met by fossil fuels [

1]. This heavy reliance on non-renewable sources continues to drive greenhouse gas emissions, contributing significantly to climate change. If current trends persist, studies predict that the global temperature could rise by 1.5556 °C by 2050, well above the permissible increase of 0.4–0.9 °C outlined by the UNFCCC [

2]. Recognizing the urgent need for action, the United Nations General Assembly in 2015 emphasized that achieving Sustainable Development Goal 7, “Affordable and Clean Energy”, is only feasible through the widespread adoption of Renewable Energy Sources (RES) [

3]. RES are essential not only for mitigating environmental degradation by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and pollution but also for strengthening energy security [

4]. By diversifying the energy supply, promoting local energy production, and increasing system resilience against disruptions, RES help overcome the inherent weaknesses of traditional energy infrastructures [

5,

6]. RES supports the transition to a decentralized power grid through distributed generation (DG) technologies such as photovoltaic (PV) systems, wind turbine generators (WTGs), and battery energy storage systems (BESSs). These technologies enhance grid reliability, reduce transmission losses, and allow for more flexible and adaptive energy systems [

7]. As the global demand for electricity continues to surge and the urgency for clean energy intensifies, the integration of RES has become not just beneficial but inevitable for a sustainable energy future.

Facilitating RES integration into the electrical grid necessitates the use of power electronic converters [

8]. They condition the electrical output from RES and align it with the grid’s voltage and frequency, contributing to improved stability and reliability [

9]. They enable bidirectional energy exchange between storage devices, such as batteries, and the grid, playing a key role in energy storage systems. This capability helps manage the intermittent nature of renewable generation, contributes to grid stability, and provides subsidiary functions like voltage and frequency regulation [

10,

11]. In high-voltage direct-current (HVAC) network, converters improve the efficiency of long-distance power transmission by reducing transmission losses, increasing capacity, and enabling the connection of asynchronous grids [

12]. Integrating RES with power electronic converters poses a significant challenge, primarily due to power quality issues, with harmonic distortion being a major contributor to these problems [

13,

14]. The primary sources of harmonics in inverter-based systems can be categorized as follows [

15,

16]: (i) DC-link voltage harmonics, which stem from intermittency and rapid fluctuations in the power supply voltage; (ii) switching harmonics, arising due to inaccuracies or mismatches in the generation of switching signals; and (iii) grid voltage harmonics, introduced by discrepancies between the inverter’s AC output and the grid’s nominal voltage profile. Harmonic distortions within distribution networks can trigger resonance phenomena, which in turn may lead to a range of operational challenges. Harmonic distortion in power systems can degrade efficiency and reliability by causing equipment overheating, increased power losses, and higher maintenance costs [

17]. It can disrupt the operation of protection devices and sensitive equipment [

18], while also inducing resonance in the network, leading to harmonic amplification and further stressing system components [

15,

17].

To maximize the performance of RES integration in distribution grids, it is essential to mitigate the total harmonic distortion (THD) injected into the network. This can be achieved by implementing appropriate control strategies for power electronic converters, enabling effective mitigation of lower-order harmonics and higher-order harmonics, typically concentrated around the switching frequency, can be attenuated easily by incorporating passive filters at the point of common coupling (PCC)[

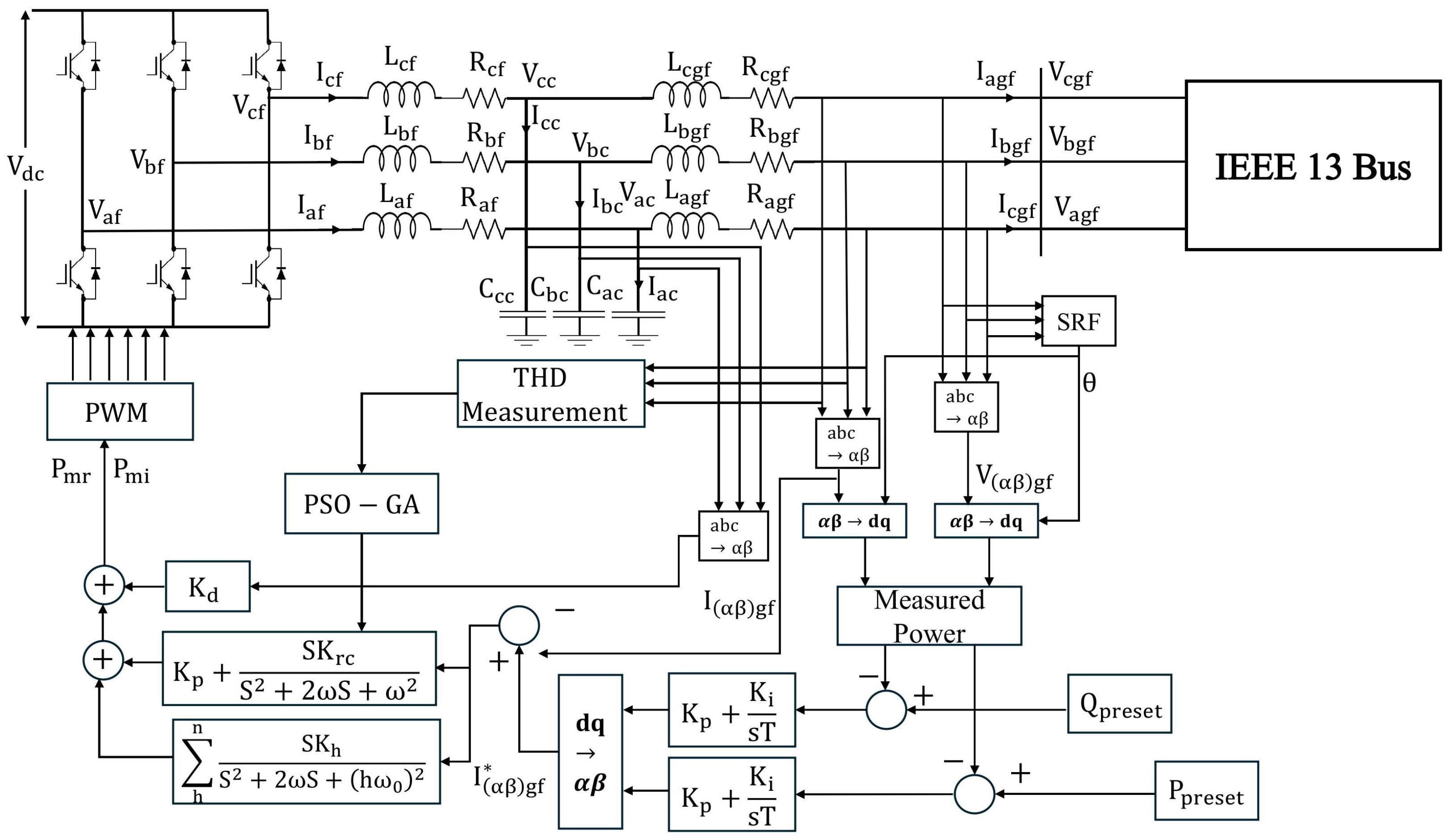

19]. In this study, a proportional resonant (PR) controller is implemented in DIgSILENT Power Factory to mitigate harmonics injected by grid-connected inverters equipped with LCL filters. The methodology framework is presented in

Figure 1, and the associated system topology is illustrated in

Figure 2.

This paper makes three contributions: (i) a feeder-level validation of stationary-frame PR current control on the unbalanced IEEE 13-bus system with EMT waveforms and FFT-based THD computed directly from DIgSILENT; (ii) a hybrid PSO–GA procedure constrained by analytic guard-rails (bandwidth, PM/GM, modulation, LCL resonance) so the optimizer searches only feasible/stable regions; (iii) a robustness and sensitivity study against large grid-impedance increase (up to ), LCL-parameter drift, and Hz grid-frequency detuning, with dynamic metrics (rise time, overshoot, ISE/ITAE) in addition to THD.

2. Literature Review

Advanced control of grid-tied inverters has centered on harmonic mitigation and power quality enhancement, particularly under the realistically unbalanced conditions typical of distribution networks. PR and multi-resonant controllers are the most prominent solutions.

PR and multi-resonant controllers for unbalanced grids: Hybrid SOGI-resonant control has been shown to attenuate harmonics from nonlinear loads while managing active and reactive power [

20], and metaheuristic-optimized quasi-PR control improves PV inverter performance under nonlinear and moderately unbalanced operation [

21]. A fixed-gain PR controller that eliminates phase-locked loops (PLLs) and employs active damping simplifies implementation but is effective only for mild unbalance [

22]. Robust multi-resonant approaches enhance dynamic response through pole placement and anti-windup strategies [

23], while resonant PID designs improve grid synchronization in balanced three-phase, four-wire systems [

24]. Controllers using proportional multi-resonant and nonlinear IP/A-W structures achieve low THD in single-phase operation, but their performance under variable loading remains unexplored [

25]. Selective-harmonic PR control tuned with genetic algorithms (GAs) demonstrates large THD reductions yet is validated only for balanced conditions [

26]. Coordinated active-damping and PR-HR designs mitigate resonance in three-phase LCL-filtered inverters, still assuming balanced grids [

27]. Digital PR with recursive harmonic compensation maintains synchronization under distorted but balanced voltages [

28], and enhanced PI-resonant control suppresses low-order harmonics while neglecting load asymmetry [

29]. Further, pole-placement resonant controllers for VSIs [

30,

31] and frequency-adaptive PR controllers for seamless stand-alone/grid-interactive transitions [

32] largely ignore pronounced unbalance.

Metaheuristic optimization of PR parameters: As controller gains strongly influence dynamic and harmonic performance, metaheuristic tuning has received considerable attention. A Bacterial-Foraging/Seagull-Optimiser hybrid achieved 1.5% THD and rapid dynamics in a 3.05-kW PV system, though higher-order harmonics and severe nonlinearity were not analyzed [

33]. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) enabled fast convergence and voltage regulation under unbalanced loads in islanded microgrids [

34]. Ant-Lion Optimization (ALO) reduced THD to 1.74% but exhibited high overshoot and a narrow reactive-power operating range [

35]. A hybrid Harris Hawks Optimization–PSO scheme cut conduction losses and THD in a seven-level inverter, albeit with significant computational complexity [

36]. GA-tuned damped PR controllers improved phase margin and resonance suppression [

37], while PSO-optimized PI/PR control in PV inverters delivered low THD during voltage sag and fault conditions with incomplete reporting of computational cost [

38]. Firefly Algorithm tuning attained 3.76% THD and high efficiency but without analyzing computation load or parameter sensitivity [

39]. Multi-resonant PR controllers optimized via Harris Hawks, PSO, and Grey Wolf Optimization realized 2.94% THD yet involved high-dimensional parameter spaces and fixed resonant bandwidths [

40]. GA-based PR tuning with a selective harmonic compensator met IEEE-519 limits but raised concerns over computational burden and transient overshoot [

26].

Table 1 comprehensively summarizes the performance characteristics and limitations of various PR-family controllers. Across the literature, the following two recurring limitations stand out:

Grid conditions: Most controllers are tested only on balanced or mildly unbalanced grids, despite the fact that real-world distribution feeders often exhibit significant phase-voltage and current disparities. These imbalances arise from uneven load distribution, asymmetric line impedance, and diverse transformer configurations.

Optimization methods: Standalone metaheuristic algorithms often suffer from slow convergence, a tendency to get trapped in local optima, and high computational complexity. Moreover, their feasibility for real-time implementation is rarely validated.

To bridge these gaps, this study (i) deploys a stationary-frame PR controller directly in realistically unbalanced multi-phase distribution networks, eliminating the need for sequence decomposition, and (ii) proposes a hybrid PSO–GA that combines PSO’s rapid convergence with GA’s global search diversity for robust parameter tuning.

3. Modeling of Stationary Frame PR Controller

Figure 1 illustrates the control architecture designed for the grid-connected inverter (GCI), incorporating a PR controller implemented within the stationary

coordinate system. The control system features an outer loop structure that manages both active and reactive power, while inner loops are dedicated to regulating the inverter currents along the

axes. This layered control scheme ensures accurate current tracking and stable operation. To achieve low HD and maintain synchronism with the grid, PR controllers are employed in the current loops, enabling precise alignment of the inverter output with the reference currents. The dynamic behavior of the GCI is captured through current equations formulated in the abc stationary frame. These equations are expressed as follows [

24,

40]: The terminology and classifications of key control components used throughout this work are summarized in

Table 2, providing a comprehensive taxonomy for clarity and consistency.

where

represents the inverter-side inductor, capacitor, grid-side inductor, inverter-side resistor and grid-side resistor, respectively, in the

reference frame. Similarly,

represents output inverter current, capacitor current, input grid current, inverter voltage, capacitor voltage, and grid voltage in the

reference frame.

By applying the Clarke transform to the system equations originally defined in the

frame, the dynamics can be expressed in the stationary

reference frame as shown below:

where

are output inverter current, input grid current, inverter side voltage, capacitor voltage, and grid side voltage in

reference frame, respectively. This model serves as the basis for the current control loops, where the PR controller aims to reduce current tracking errors and harmonics by evaluating the difference between the inverter output and the reference grid current. The control loops also interact with the outer power control loops to regulate the active and reactive power, ensuring the GCI efficiently operates within the grid’s requirements. The system demonstrates inherent decoupling properties, allowing the current dynamics in the

axes to be independently controlled without mutual interaction. As a result, unlike traditional control approaches based on the

-rotating reference frame, there is no requirement for additional feedforward paths or decoupling networks. Moreover, the proposed method eliminates the dependency on Park and inverse Park transformations, leading to a simpler and more computationally efficient control architecture in the stationary frame [

40].

Accurate calculation of the reference current, derived from active and reactive power, is essential for precise power regulation, grid synchronization, and maintaining overall system stability [

41]. This methodology allows the inverter to effectively manage power flow, ensuring the targeted active and reactive power levels are delivered to the grid, thereby promoting reliable and efficient operation of the power system. The instantaneous stationary power is given by Equation (

7) [

19,

40].

To optimize the current control strategy within the GCI framework, PR controllers are often employed as an alternative to PI controllers. Unlike the PI controller, which places an integrator at the origin in the s-domain, the PR controller distributes the integral action around a pair of complex conjugate poles centered at the grid fundamental frequency. The ideal transfer function of a PR controller can be derived by symmetrically placing the integrator at

, resulting in [

19,

26,

40]:

Here,

represents proportional gain,

is the resonant gain, and

corresponds to the grid’s nominal frequency. This structure ensures infinite gain at the resonance frequency, allowing for zero steady-state error in tracking sinusoidal references. However, the infinite gain characteristic of the ideal PR controller may lead to instability in practical implementations. To address this, a damping term is introduced around the resonant frequency, yielding a more robust and implementable form [

19,

26,

40]:

In this practical formulation,

defines the bandwidth of the resonant peak, effectively smoothing the infinite gain and enhancing the controller’s stability while preserving its tracking ability. Furthermore, to mitigate specific harmonic components in the current, harmonic compensators (HCs) can be incorporated. Each HC targets a particular harmonic order

h, and their aggregate transfer function is expressed as [

19,

40]:

Each HC functions as a band-pass filter centered at allowing selective suppression of specific harmonic components without affecting the fundamental frequency response. The design of each HC is defined by its resonant gain and bandwidth , both dependent on the targeted harmonic order h.

Design Model and Checks (Used in Tuning)

Blocks. Using the practical PR definition in (

9), we include optional selective harmonic compensators (SHCs) as

The combined (sampling + computation + PWM) delay is modeled as

and, for frequency-domain evaluation (margins/crossover), approximated by Padé (1,1),

Open loop and sensitivity functions. With

and

as in

Section 4 (plant relations (

22)–(

24); see also (

29)–(

30)), the loop used for checks is

The sensitivity and complementary-sensitivity are

Targets and acceptance. Let

. We target a practical crossover band

A candidate

is accepted if the following hold:

The PR internal model implies

as

; we verify the finite-

bound (

17) numerically.

Objective (statement). With spectral/tracking terms computed from EMT waveforms, the fitness is

where the crossover penalty is

Symbols: grid fundamental; switching freq.; sampling freq.; = ; PR bandwidth; HC bandwidth; gains; delays; crossover; PM/GM margins; weights/tolerances.

Remark (frequency detuning robustness).

For grid-frequency excursions

Hz, we enforce

so that

remains within the PR pass band, and verify

with

using the delay-inclusive loop (

14). If harmonic compensator are enabled, their bandwidths satisfy

so that

are covered. This ensures the proposed tuning maintains tracking and margins for

Hz without reconfiguration.

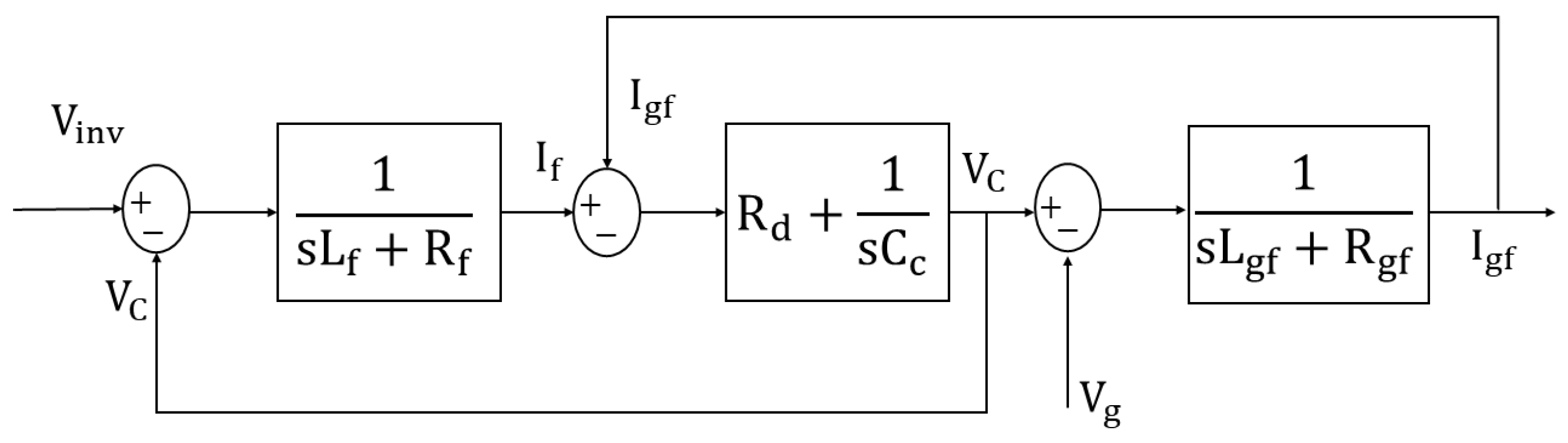

4. Integrating LCL Filters with PR-Based Current Control

LCL filters are favored in GCI for their superior harmonic suppression over L and LC filters. Its steeper roll-off in frequency response allows it to effectively suppress high-frequency switching harmonics, thereby enhancing power quality at PCC. LCL filter offers improved cost and size efficiency, as it achieves superior filtering performance with smaller passive components, whereas simple L filters would require significantly larger inductance for comparable attenuation. The LCL configuration also contributes to higher overall system efficiency by reducing ripple current on the inverter side, which in turn minimizes power losses and thermal stress on components. These advantages collectively improve the performance of the GCI [

42,

43]. The following equations characterize the relationship between the inverter output voltage and the grid-side current in a GCI system, incorporating the effects of the LCL filter components [

44,

45]. This mathematical model is essential for understanding the system’s dynamic response and for developing effective current control strategies. The schematic representation of the LCL filter configuration is illustrated in

Figure 2.

Here,

denote the damping resistor, grid resistance, and grid inductance, respectively, while the remaining parameters are defined in the preceding section. The selection of

is often guided by the analysis of current ripple under inverter switching conditions. The capacitor

is chosen based on its reactive power contribution, which is typically limited to approximately 5% of the inverter’s nominal power. The grid-side inductance

is then designed to ensure sufficient attenuation of high-frequency harmonics, with a commonly adopted inductance ratio of

. These guidelines facilitate the effective parameterization of LCL filters for robust harmonic attenuation and system stability [

44,

45].

Figure 3 illustrates the block diagram representation of the LCL filter transfer function.

Here, represent DC-link voltage, switching frequency, desired attenuation factor, and rated current of the converter, respectively. corresponds to the base impedance, while defines the base value of the filter capacitance. The parameters indicate the fundamental grid angular frequency, angular switching frequency, and angular resonance frequency respectively.

Let

,

,

. From (

30), with

,

. Hence the

minimum resonance (closest to

) occurs at

We enforce

and verify

together with

,

dB on the design open loop (including delay). The damping

in (

29) is recomputed using the actual

, so the resonance peak remains controlled. Thus, within typical tolerances (e.g.,

= 20%,

= 10%), stability is retained; only modest THD shifts are expected due to

relocation.

4.1. Parameter Design of PR Controller

In contrast to traditional implementations where the controller output directly generates inverter voltages, this work employs a modulation-based control strategy. The PR controller outputs

and

, which represent the real and imaginary components of the modulation index used to generate inverter switching signals via a PWM unit, as described by Equations (

31) and (

32),

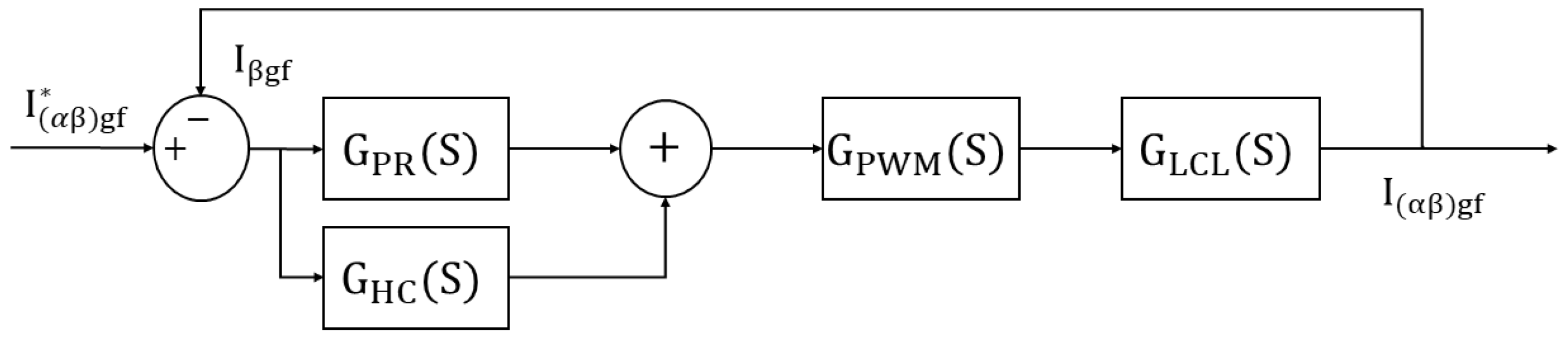

The PR controller parameters can be tuned based on the control structure shown in

Figure 4. Consequently, the open-loop transfer function is expressed as

The bandwidth of the PR controller is typically designed to fall within 5% to 10% of the inverter’s switching frequency to ensure fast transient performance. The resonant section within the PR controller is configured to target the fundamental frequency, allowing it to effectively track and regulate sinusoidal signals near this frequency. At the resonant frequency, the controller offers a significantly high gain, while the gain rapidly decreases at other frequencies, minimizing interference from harmonics. Moreover, a noticeable decline in the phase response occurs near the resonant frequency. Therefore, it is crucial to ensure that the minimum phase response in this region still satisfies the required phase margin.

4.2. Analytical Framework for PR Controller and Harmonic Compensator Design

To ensure stable and accurate sinusoidal current tracking, the analytical design of the PR controller and HC was carried out based on the open-loop model of the inverter LCL filter system. Following the analytical guidelines presented in [

40], two key design objectives were satisfied: (i) achieving adequate control bandwidth (BW) and (ii) ensuring suitable phase margins at the fundamental and harmonic frequencies.

4.2.1. Control Bandwidth and Proportional Gain Design

The control bandwidth of the PR controller was selected within 5–10% of the inverter switching frequency to provide a rapid dynamic response while maintaining stability. For a switching frequency of 10 kHz, this corresponds to a control BW of 0.5 –1 kHz. The resonant term of the PR controller was tuned at the grid’s fundamental frequency (50 Hz) to provide infinite gain at this frequency and eliminate steady-state error.

The proportional gain

was designed to achieve a desired phase margin

(typically 40°–60°) at the open-loop 0 dB crossover frequency

, which can be determined by

The proportional gain ensuring unit magnitude at

is expressed as

where

represents the computational and PWM delay. These relationships ensure that the PR controller provides sufficient gain and phase margin for stability.

4.2.2. Resonant Gain Design

Due to the sharp phase drop at the resonant frequency, the resonant gain

must be chosen to retain an appropriate phase margin

(40°–60°) around the fundamental frequency. At this frequency,

, the resonant term phase condition can be expressed as

and the required

is obtained by

where

4.2.3. Harmonic Compensators

Higher-order HCs were designed following the same procedure, with resonant frequencies set at integer multiples of the fundamental frequency

for

. This ensures selective harmonic attenuation while preserving system stability [

40].

In (11)–(13) the grid impedance enters via

. For a conservative resonance check we define

We design the loop with and verify together with , on the open loop including delay. Under a increase in grid inductance (), shifts according to the expression above but remains well separated from for the stated bounds; the passive damping in (18) further mitigates peaking. Therefore, the controller remains stable; a modest THD change can occur due to the new resonance location but does not alter the stability guarantees.

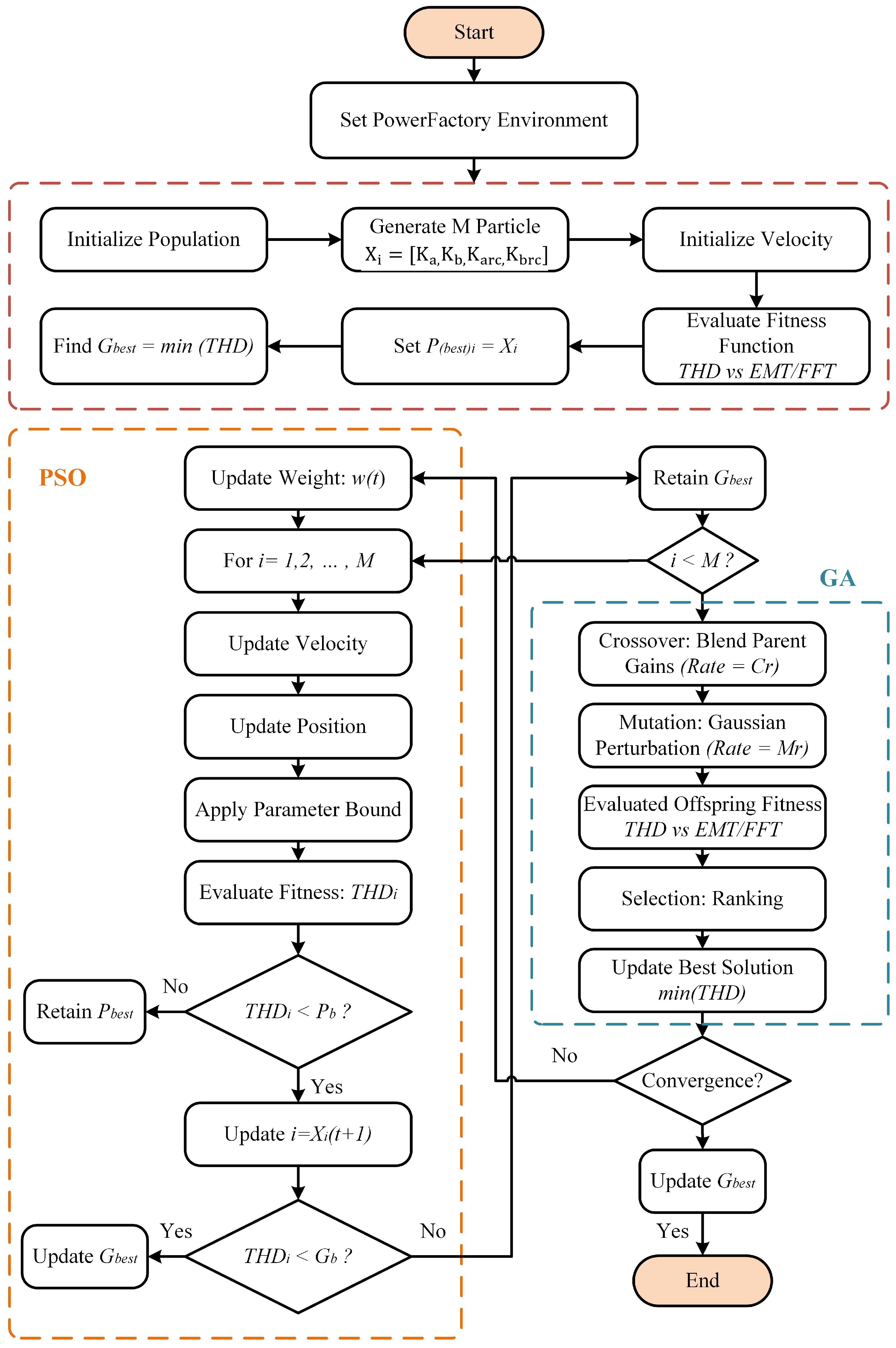

5. Hybrid PSO-GA Optimization for PR Controller Tuning

In this study, a hybrid PSO-GA framework is proposed for the optimal tuning of PR controller parameters in a two-level grid-connected inverter topology. The optimization primarily aims to reduce the THD in the inverter’s output current, improving the quality of the current fed into the grid. The optimization algorithm was developed in Python 3.12.3 and integrated with the DIgSILENT PowerFactory simulation platform through its COM-based API. This coupling enables dynamic parameter manipulation, automated execution of electromagnetic transient (EMT) simulations, and harmonic distortion evaluation through FFT-based frequency-domain analysis, collectively constituting a high-fidelity, closed-loop co-simulation framework. The hybrid metaheuristic leverages the rapid convergence behavior of PSO and the robust global search capabilities of GA to overcome local optima and ensure comprehensive exploration of the solution space. The process initiates with the stochastic generation of a swarm population, where each particle represents a candidate solution comprising a vector of PR controller gains. These gain values are directly injected into the DSL-based controller model within PowerFactory. The fitness of each particle is quantitatively determined by calculating the THD from the inverter current spectrum, obtained through FFT post-processing of waveform data generated from EMT simulations. This approach ensures precise harmonic profiling under realistic dynamic grid conditions and supports the derivation of globally optimal control parameters.

Throughout each iteration of the hybrid PSO-GA process, candidate PR controller parameters undergo programmatic injection into the PowerFactory model via its DSL interface. Subsequently, EMT simulation execution yields inverter current waveforms, which undergo FFT analysis utilizing PowerFactory’s built-in spectral module. THD calculation from the frequency-domain data serves as the fitness metric for each particle. Particle personal best and global best positions update dynamically based on THD fitness values. Standard PSO velocity and position update equations govern swarm evolution, incorporating inertia weight , cognitive acceleration coefficient , and social acceleration coefficient . To prevent premature convergence and augment global search efficacy, GA operators are embedded strategically within the optimization loop. Upon reaching a predefined PSO iteration count or detecting population stagnation, a GA phase activates.

This phase applies tournament selection to isolate elite particles based on fitness performance. Selected elites undergo arithmetic crossover, generating offspring solutions, which are further subjected to Gaussian mutation to introduce stochastic variability. These offspring replace the lowest-performing swarm members, reintroducing population diversity and facilitating escape from local minima. Termination criteria include attainment of maximum iterations or convergence of global fitness improvement below a specified threshold.

The optimization concludes with identification of the PR controller gain set yielding minimum THD, accompanied by corresponding FFT spectral data for post-optimization validation. The hybrid PSO-GA exhibits superior convergence characteristics and enhanced exploratory capacity relative to standalone PSO or GA implementations, resulting in more accurate PR controller tuning and improved harmonic mitigation performance in grid-connected inverter systems. The

Figure 5 illustrates the implementation flowchart of the hybrid algorithm. The detailed pseudo-code of the GA, PSO, and hybrid PSO-GA is presented in Algorithms 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

| Algorithm 1 GA for tuning PI and PR controller parameters |

Require: PowerFactory controller model with PI and PR controllers, simulation environment, parameter bounds Ensure: Optimal controller gains minimizing total harmonic distortion (THD) - 1:

Initialize GA parameters: - 2:

Population size N - 3:

Maximum generations G - 4:

Crossover rate - 5:

Mutation rate - 6:

Parameter bounds - 7:

THD threshold for early stopping - 8:

Initialize population of N individuals randomly: - 9:

Each individual where - 10:

= PI controller gains - 11:

= PR controller gains - 12:

Set best_score , best_solution - 13:

for generation to G do do - 14:

for each individual do - 15:

Update controller parameters in PowerFactory: - 16:

Set PI gains: , - 17:

Set PR gains: , - 18:

Run simulation and FFT harmonic analysis - 19:

Calculate THD value as fitness score - 20:

if best_score then - 21:

best_score - 22:

best_solution - 23:

end if - 24:

end for - 25:

if best_score then - 26:

break ⊳ Early stopping criterion met - 27:

end if - 28:

Selection: Use tournament selection (size=2) to select parents based on fitness - 29:

Crossover: For each parent pair, perform one-point crossover with probability to generate offspring - 30:

Mutation: Apply Gaussian mutation to each gene of offspring with probability ; clip within - 31:

Form new population with mutated offspring - 32:

end for - 33:

return best_solution = optimal , best_score = minimum THD

|

| Algorithm 2 PSO for Tuning PI and PR Controller Parameters |

- 1:

Initialize PSO parameters: - 2:

Number of particles N - 3:

Maximum iterations I - 4:

Inertia weight w - 5:

Cognitive coefficient - 6:

Social coefficient - 7:

Parameter bounds - 8:

THD threshold for early stopping - 9:

Initialize particle positions and velocities randomly for - 10:

Each position within bounds - 11:

Set personal bests , evaluate fitness for each particle - 12:

Set global best best based on - 13:

for iteration to I do - 14:

for each particle to N do - 15:

Update velocity:

where - 16:

Update position: - 17:

Clamp within - 18:

Update controller parameters in PowerFactory with - 19:

Run simulation and FFT harmonic analysis - 20:

Calculate THD value as fitness score - 21:

if then - 22:

- 23:

end if - 24:

if then - 25:

- 26:

end if - 27:

end for - 28:

if then - 29:

break ⊳ Early stopping criterion met - 30:

end if - 31:

end for - 32:

return best_solution = , best_score = =0

|

| Algorithm 3 Hybrid PSO-GA for Tuning PI and PR Controller Parameters |

- 1:

Initialize PSO-GA parameters: - 2:

Number of particles N - 3:

Maximum iterations I - 4:

Inertia weight w - 5:

Cognitive and social coefficients , - 6:

GA crossover rate , mutation rate - 7:

Parameter bounds - 8:

THD threshold for early stopping - 9:

Initialize particle positions and velocities randomly for - 10:

Each within bounds - 11:

Set personal bests , evaluate fitness - 12:

Set global best best - 13:

for iteration to I do - 14:

for each particle to N do - 15:

- 16:

Update position: - 17:

Clamp within - 18:

Run simulation and evaluate using PowerFactory - 19:

if then - 20:

end if - 21:

if then - 22:

end if - 23:

end for - 24:

Apply GA operators: - 25:

Perform tournament selection on - 26:

Apply crossover (probability ) to selected parents - 27:

Apply Gaussian mutation (probability ); clip within bounds - 28:

Replace worst-performing particles with offspring - 29:

if then - 30:

break ⊳ Early stopping criterion met - 31:

end if - 32:

end for - 33:

return best_solution = , best_score =

|

6. Discussion

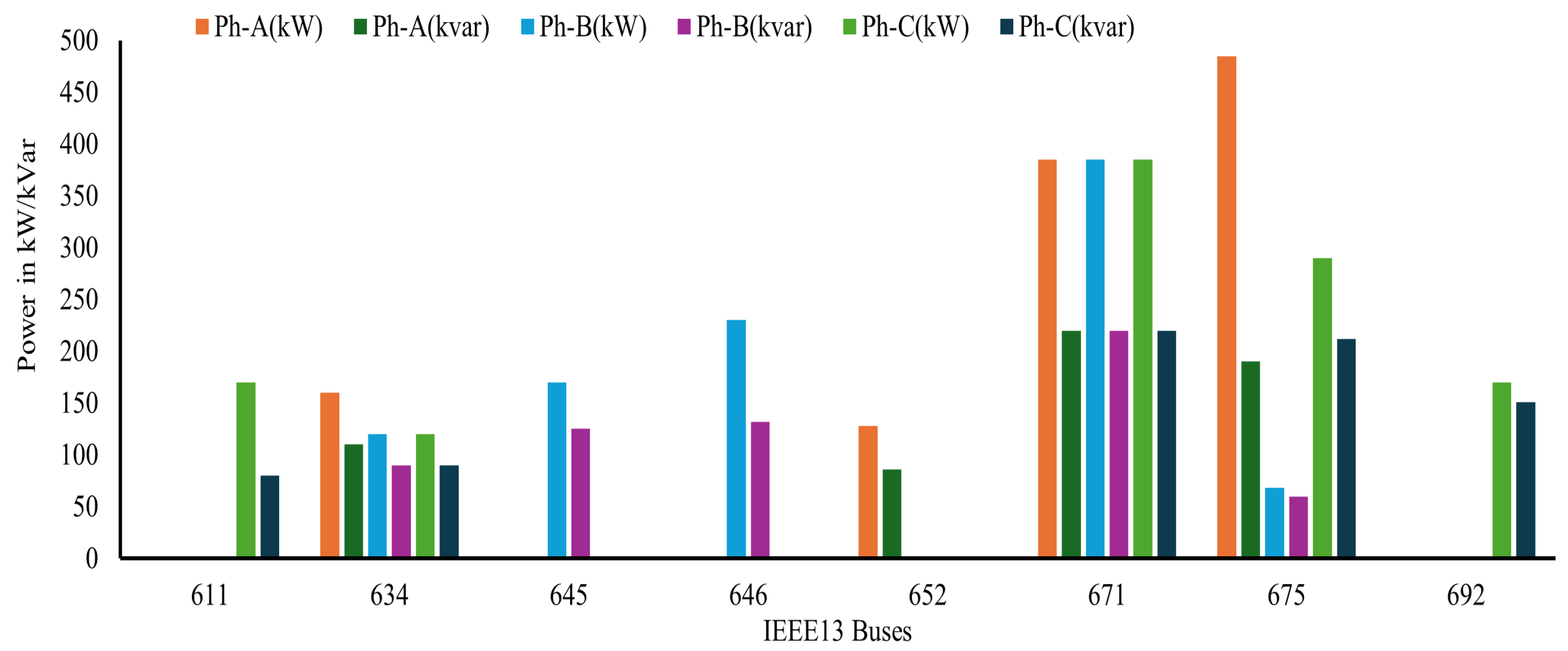

The control strategy depicted in

Figure 1, along with the optimization framework shown in

Figure 5, was implemented and simulated in DIgSILENT PowerFactory. The test system consists of a two-level GCI coupled with a BESS, connected to the IEEE 13-bus distribution network. This IEEE 13-bus system is a standard unbalanced radial test feeder featuring a combination of single-phase, two-phase, and three-phase loads, making it suitable for validating distributed generation performance in realistic distribution scenarios. The system’s phase-wise load allocation is depicted in

Figure 6. The detailed parameters of the inverter and associated converter components are presented in

Table 3. This study focuses on the implementation of a PR controller to regulate the inverter output current and minimize harmonic injection into the grid. The PR controller parameters are fine-tuned via a hybrid optimization approach to effectively mitigate harmonics. The performance of the system is assessed in terms of current harmonic distortion and is validated against the limits specified by IEC 61727 [

46] and IEEE 1547 [

47] standards.

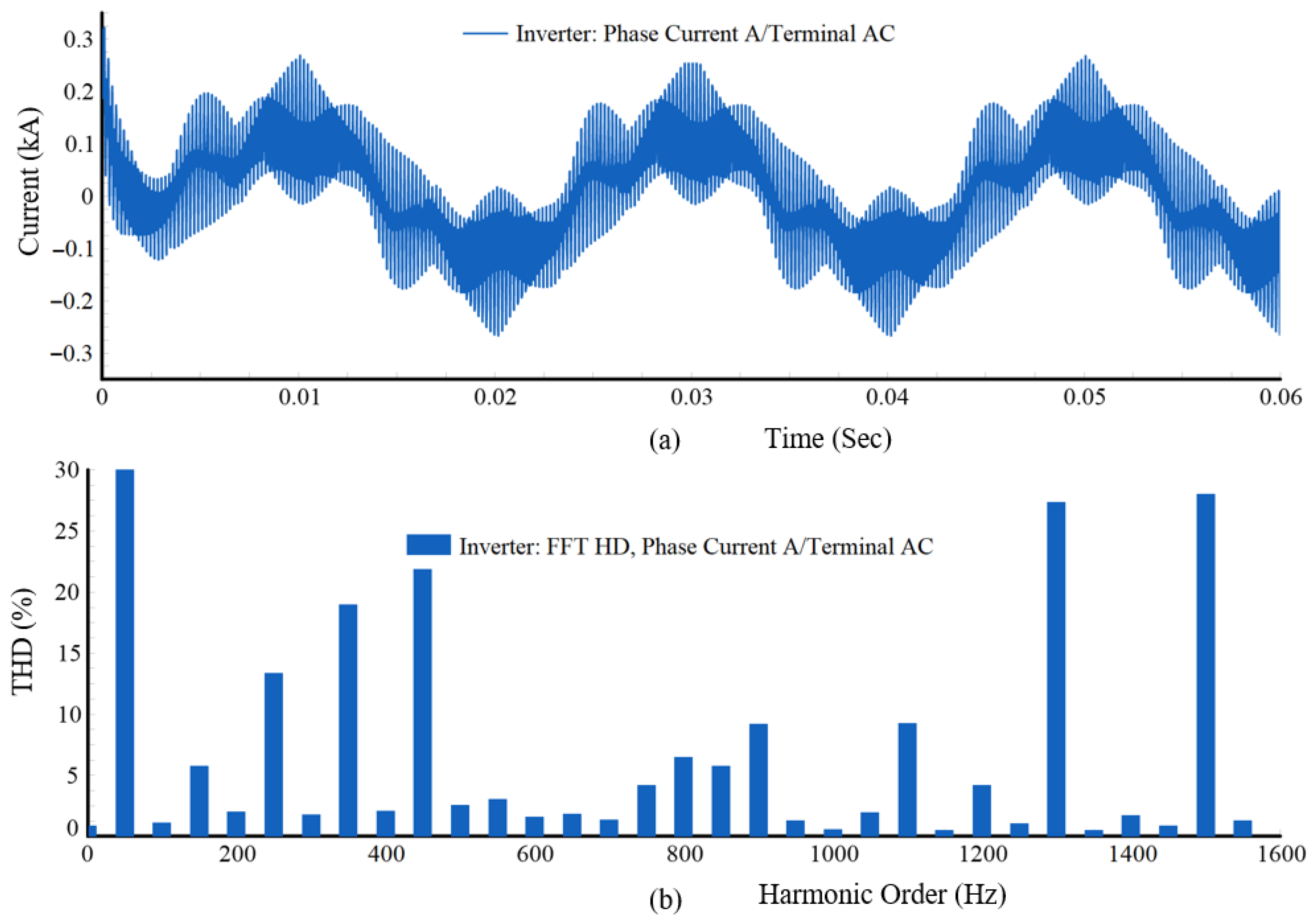

Figure 7 depicts the inverter output current operating in the absence of any current regulation method. The waveform is evidently distorted, reflecting the absence of harmonic suppression mechanisms. The FFT spectrum analysis reveals the presence of both low-order and high-order harmonic components contributing significantly to waveform degradation. Among the low-order harmonics, the 3rd harmonic (150 Hz) registers a magnitude of 5.73%, the 5th harmonic (250 Hz) is measured at 13.36%, the 7th harmonic (350 Hz) at 18.94%, and the 9th harmonic (450 Hz) reaches 21.94%. These components are indicative of severe harmonic distortion commonly associated with inverter switching in the absence of appropriate control. The high-frequency harmonics, such as the 26th (1300 Hz) and 30th (1500 Hz), exhibit exceptionally high distortion levels of 27.35% and 28.01%, respectively. Such high-frequency content is typically introduced by the switching operation and indicates poor spectral attenuation. This excessive distortion not only violates compliance requirements but also poses serious technical concerns, including elevated power losses, thermal stress on equipment, potential resonance conditions, and increased electromagnetic interference. These baseline results clearly demonstrate the limitations of operating the inverter without an active current control mechanism. Consequently, they highlight the necessity for deploying an optimally tuned PR controller to effectively mitigate harmonic injection and ensure reliable, standard-compliant grid integration.

6.1. Performance Analysis of Optimized Controller

This section presents a comprehensive analysis of the performance of a PR and PI controller optimized using three distinct metaheuristic algorithms: PSO, GA, and a hybrid PSO-GA technique. The controller’s effectiveness is assessed based on multiple performance indicators, including current waveform quality, harmonic distortion suppression, control accuracy, and optimization efficiency. The EMT simulations were conducted with a fixed integration time step of 1 s (0.000001 s), ensuring high temporal resolution required for accurate dynamic analysis. Each simulation ran for a total duration of 1 s, which was sufficient to observe both transient and steady-state responses of the inverter system under test.

6.1.1. Voltage Quality Comparison Between PR and PI Controllers

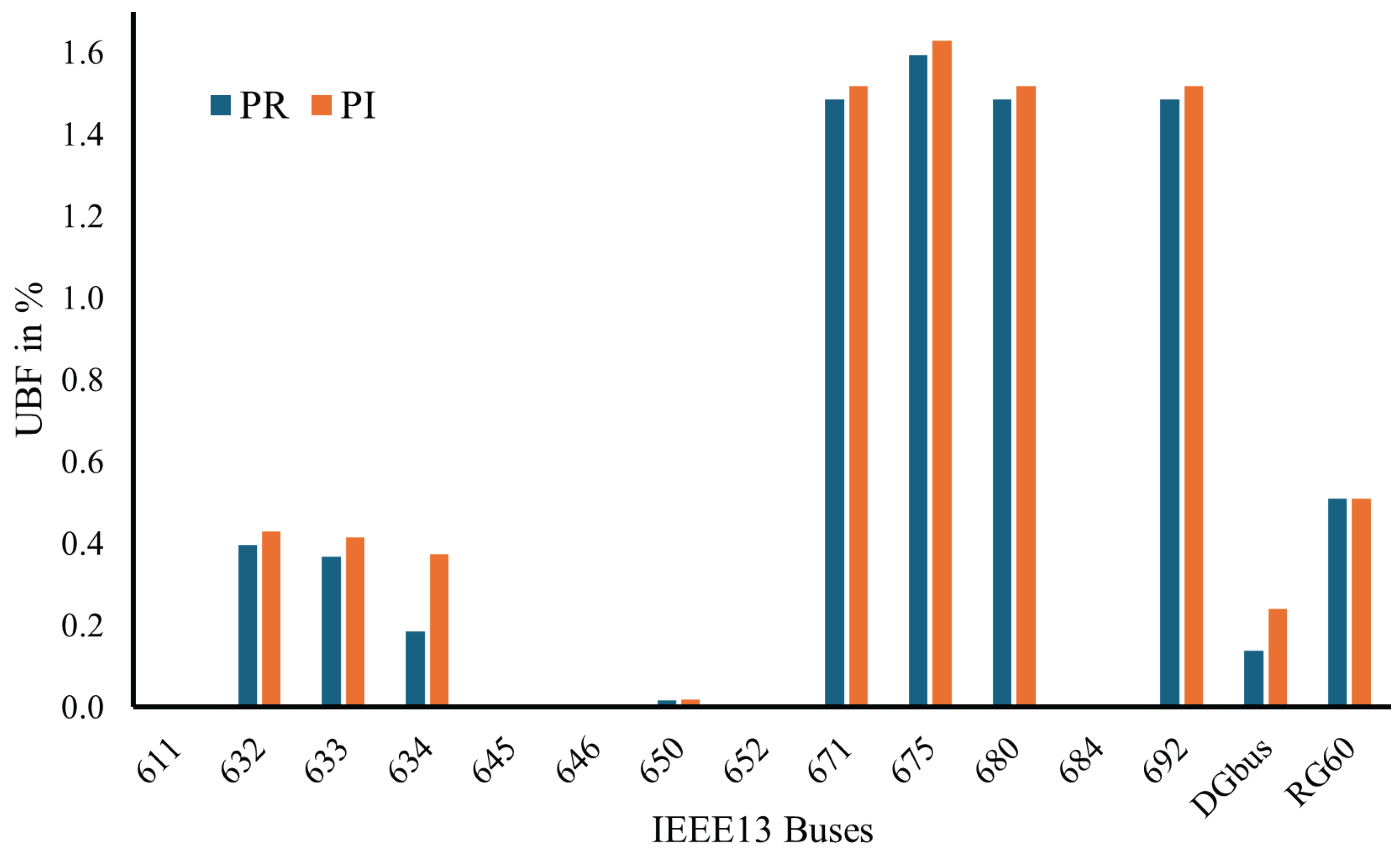

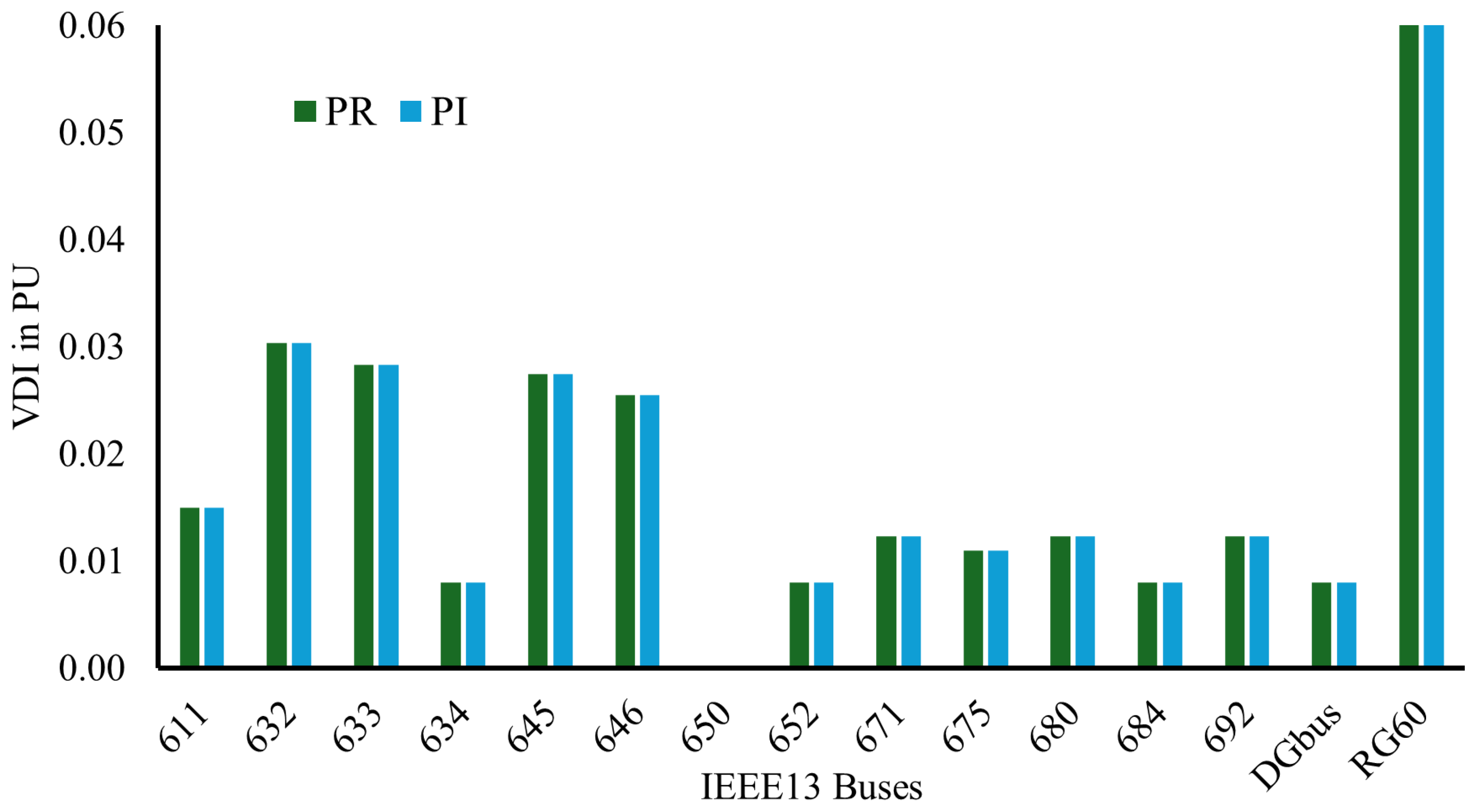

The evaluation of voltage unbalance factor (VUF) given in

Figure 8 and voltage deviation index (VDI) shown in

Figure 9 demonstrates that both PR and PI controllers exhibit minimal influence on voltage magnitude deviation. The VDI values remain identical across all buses for both control strategies, indicating that the selection of the current controller does not significantly impact steady-state voltage magnitude regulation.

Slight variations are observed in the VUF values, with the PR controller providing marginal improvements over the PI controller at specific buses. For instance, at Bus 634, the VUF decreases from 0.3744% (PI) to 0.1856% (PR), and at the DG bus, from 0.2415% (PI) to 0.1392% (PR). Despite these localized improvements, the majority of the buses exhibit either identical or minimally different VUF values. Several nodes, including Buses 611, 645, 646, 652, and 684, maintain zero unbalance under both control strategies.

These results indicate that the PR controller offers a slight advantage in mitigating voltage unbalance, particularly in locations affected by inverter injection or unbalanced loading. However, the overall effect remains limited, and neither controller demonstrates a substantial impact on voltage quality indices in isolation. The observed voltage unbalance and deviation are predominantly influenced by the distribution network configuration, load characteristics, and voltage regulation equipment. Therefore, additional system-level mitigation strategies, such as phase balancing, load reallocation, or deployment of a dedicated unbalance compensator, are recommended to achieve significant improvements in voltage quality.

6.1.2. Inverter Current Quality and Harmonic Suppression

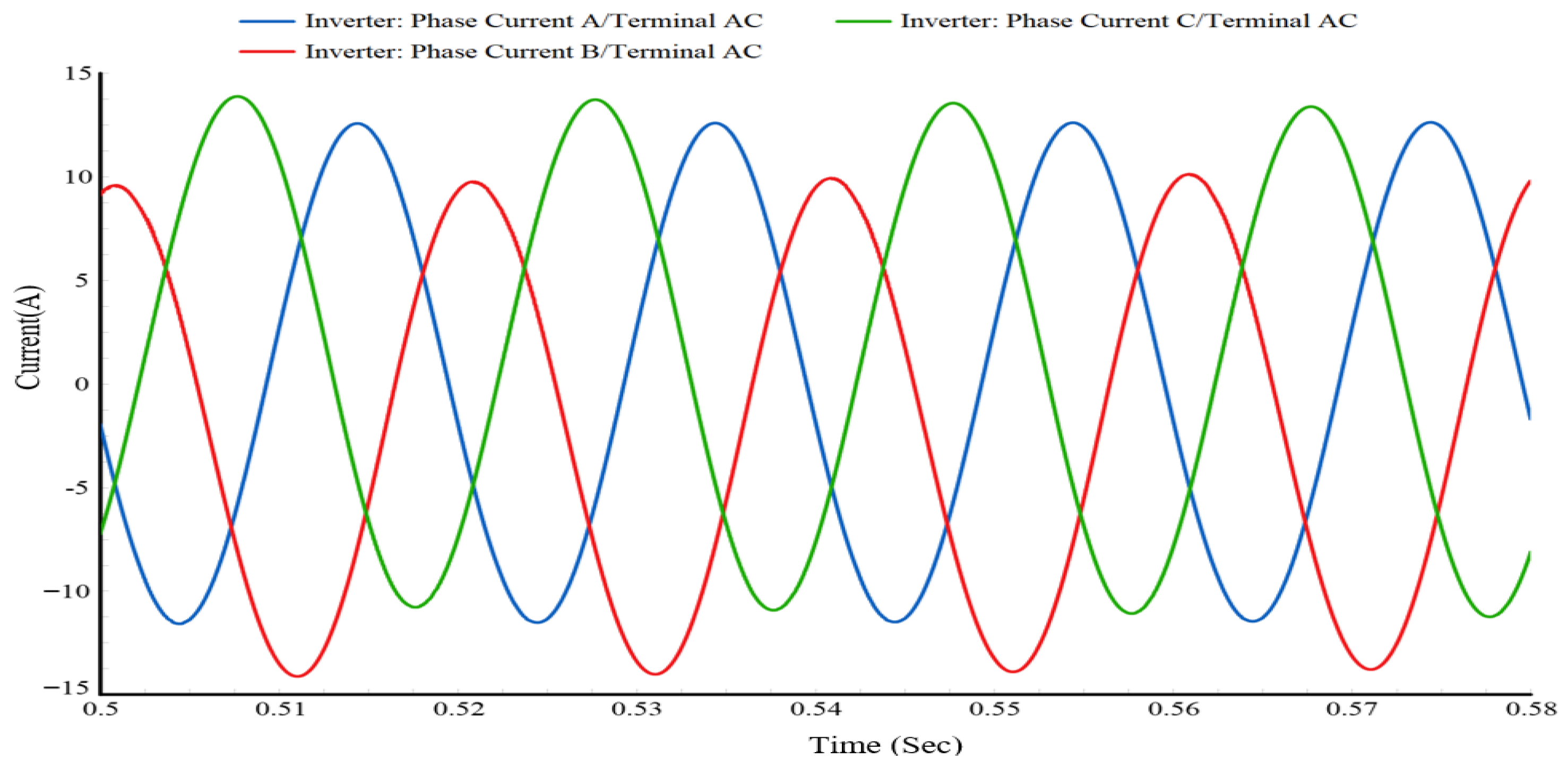

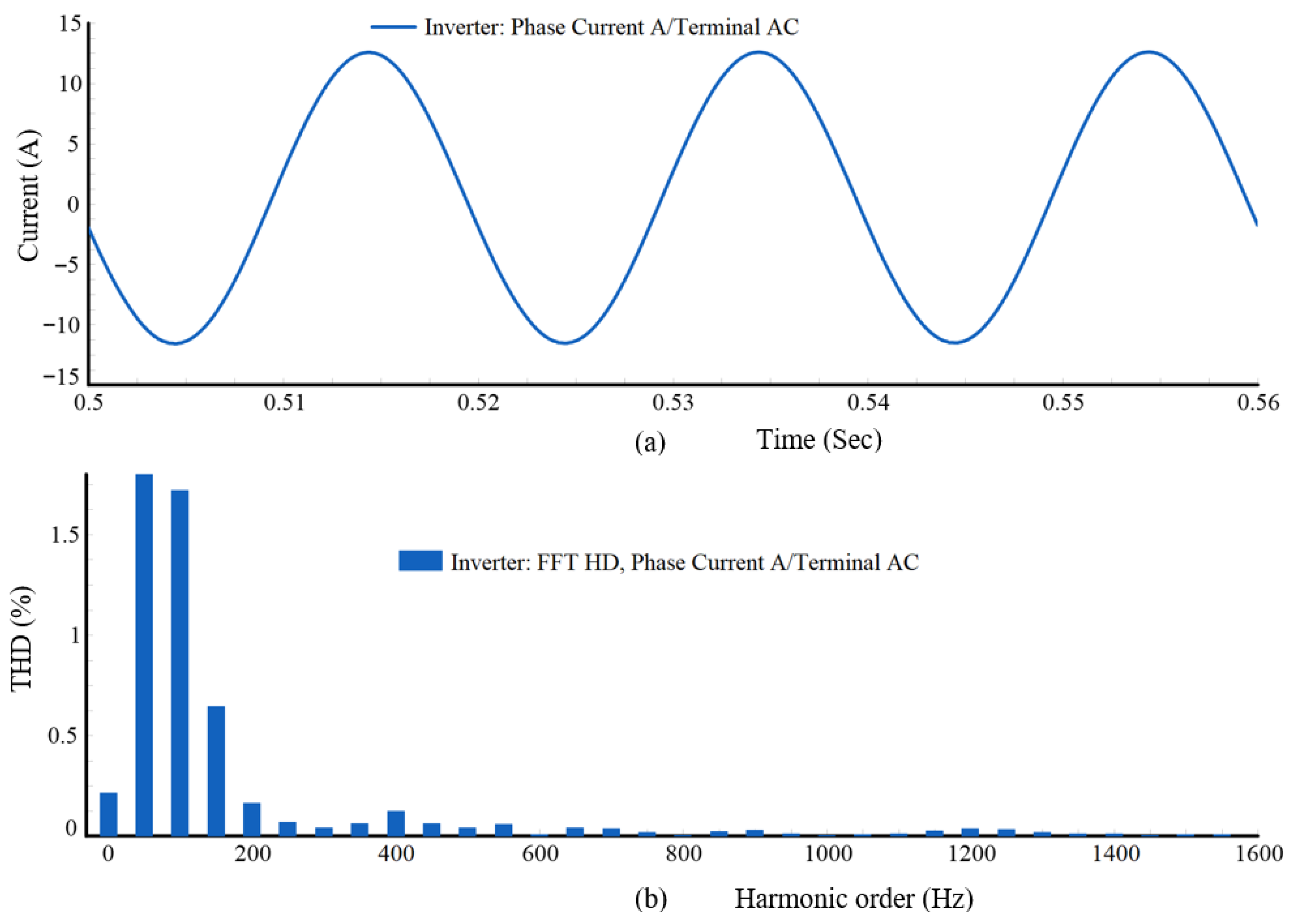

The implementation of the optimized PR controller resulted in a high-fidelity inverter output current, as depicted in

Figure 10. The time-domain waveform exhibits a close resemblance to the ideal sinusoidal reference under steady-state operating conditions, demonstrating excellent current tracking capability. The corresponding frequency-domain spectrum, presented in

Figure 11, highlights a dominant fundamental frequency component with significantly suppressed harmonic content. The lowest THD recorded was 1.0687%, achieved through the hybrid PSO-GA optimization approach. This THD value complies with the allowable harmonic distortion limits defined by IEEE 1547 and IEC 61727 standards for grid-connected inverter systems. Relative to single-metaheuristic tuning, the hybrid approach reduces THD by 27.6% compared with PSO and 14.1% compared with GA, demonstrating that the combined global exploration of PSO and local exploitation of GA translates into materially cleaner current injection.

6.1.3. Optimized Controller Gain Parameters and Harmonic Performance

The optimal gain parameters for both the PR and PI controllers were obtained using three metaheuristic optimization algorithms: PSO, GA, and a hybrid PSO-GA. For the PR controller, the tuning process targeted four critical parameters:

and

, the proportional gains along the

-axes, respectively, and

and

, the corresponding resonant gains responsible for harmonic suppression. In parallel, the PI controller was optimized by adjusting

and

, the proportional and integral gains along the

d-axis, respectively, as well as

and

, the proportional and integral gains along the

q-axis. These parameters significantly affect both the dynamic response and the harmonic attenuation capabilities of the inverter.

Table 4 presents the optimized gain values and their corresponding THD percentages.

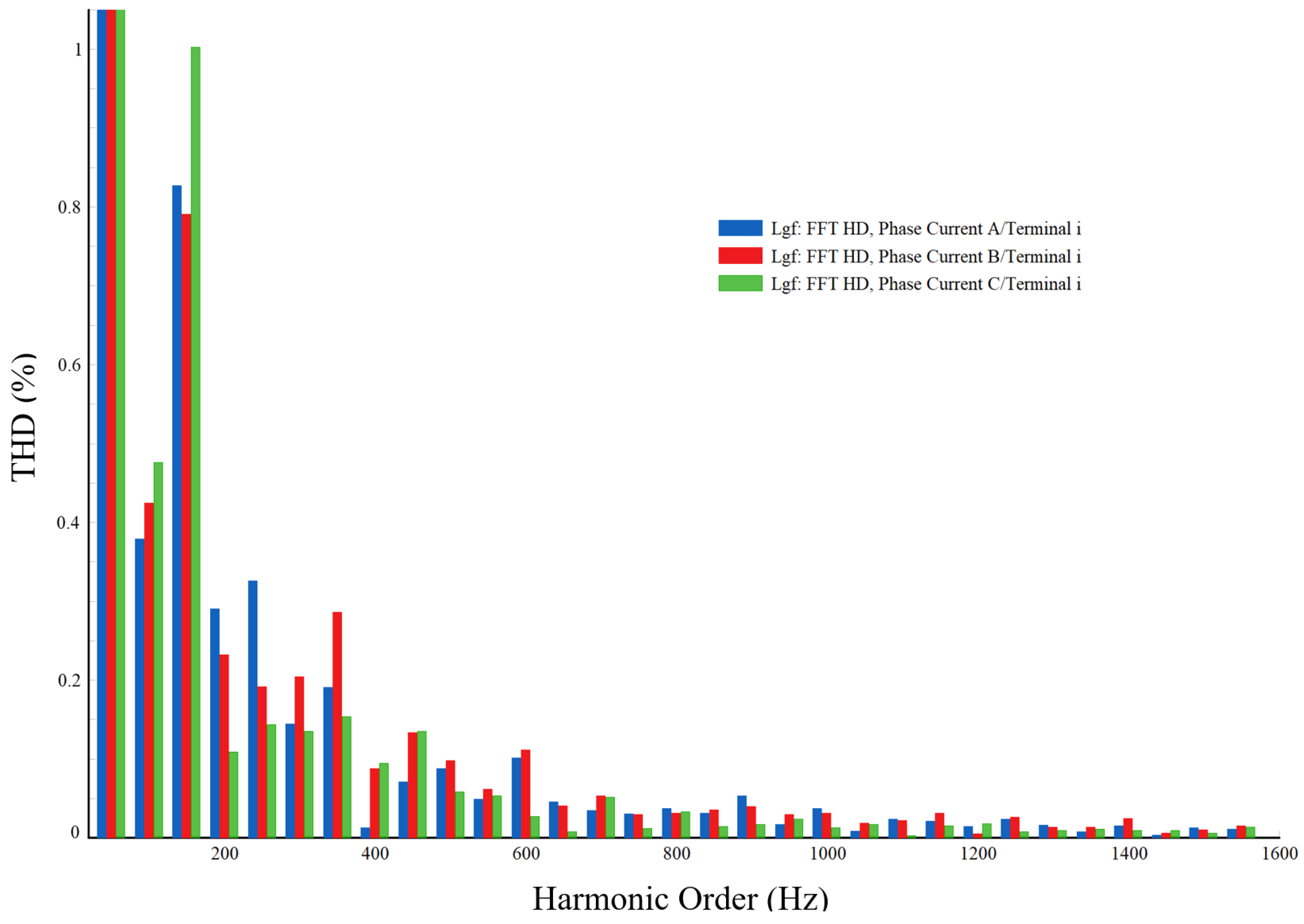

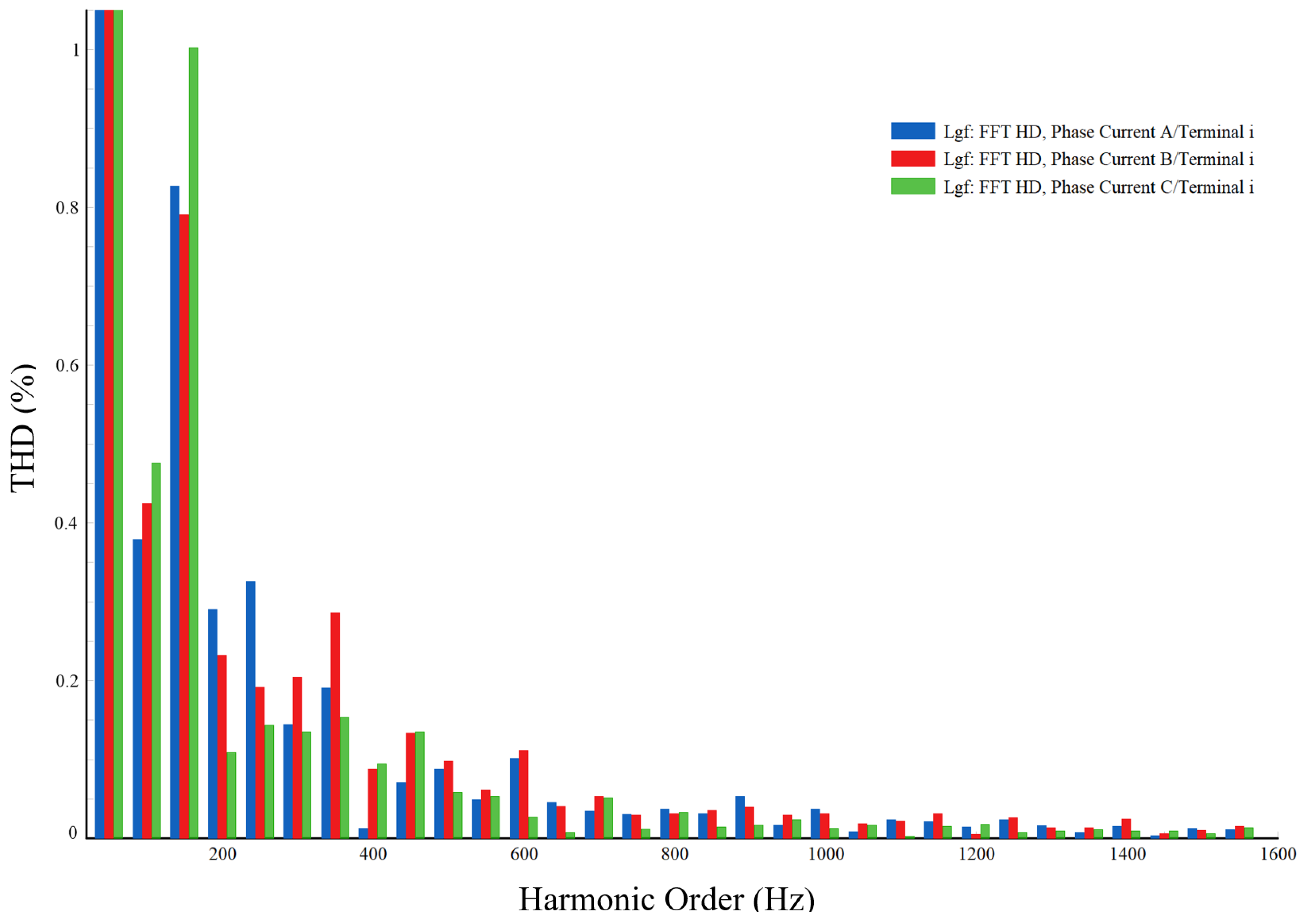

Among the optimization techniques tested, the hybrid PSO-GA produced the lowest THD values for both controllers, indicating superior tuning performance for harmonic mitigation. The corresponding FFT spectrum of the inverter current, illustrating the effectiveness of the hybrid optimization, is presented in

Figure 12. The PR controller achieved a minimum THD of 1.0687%, demonstrating effective harmonic suppression. The PI controller showed a minimum THD of 2.696%, which, while higher than the PR controller, represents a significant improvement over other methods.

The PSO algorithm yielded higher THD values of 1.4754% for the PR controller and 4.12% for the PI controller, reflecting lower harmonic mitigation effectiveness. The GA produced intermediate results, with THD values better than PSO but higher than the hybrid PSO-GA. The corresponding FFT analyses of the inverter current for PSO and GA optimization are shown in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14, respectively. These results confirm that the hybrid PSO-GA’s combined global and local search capabilities improve controller gain optimization, resulting in reduced harmonic distortion. The PR controller outperformed the PI controller in minimizing harmonic distortion under all tested optimization strategies. This demonstrates the advantages of the PR controller structure when paired with advanced metaheuristic tuning algorithms for GCI applications.

6.1.4. Error Metric Evaluation

To comprehensively assess the performance of the optimized controllers, classical error-based indices were computed for both the PR and PI controllers. These metrics quantify each controller’s ability to accurately track reference currents while minimizing dynamic and steady-state errors. The results are presented separately for the

/

axes (PR controller) and

d/

q axes (PI controller) in

Table 5.

For the PR controller, the hybrid PSO-GA method achieved the lowest error values along the -axis, with an IAE of 0.0260 and an ISE of 0.00045, marking substantial reductions of approximately 71% and 99%, respectively, compared to the PSO results. These values were also marginally lower than those obtained with GA, which recorded identical IAE and ISE values along this axis, indicating comparable steady-state accuracy but superior overall harmonic suppression by the hybrid method due to its lower THD (1.0687% vs. 1.2443%). Although PSO recorded the lowest IAE on the -axis (0.000543), its performance on other metrics was inferior and associated with a higher THD (1.4754%), highlighting a trade-off between localized accuracy and global harmonic mitigation. For the PI controller, the hybrid PSO-GA method outperformed other algorithms across all evaluated metrics in both -axes. It achieved the lowest IAE values of 0.4454 (d-axis) and 0.4736 (q-axis), alongside minimum ITSE values of 0.1826 and 0.2828, indicating enhanced transient response and steady-state precision. Corresponding ISE values showed significant reductions, decreasing from 1.7711 (PSO) to 0.3461 (hybrid) in the d-axis and from 2.2402 to 0.4500 in the q-axis, reflecting improved damping characteristics. The GA consistently surpassed PSO performance, lowering ITAE in the d-axis from 0.4342 (PSO) to 0.2510 (GA), yet fell short of the hybrid approach, underscoring the advantage of integrating global and local search strategies for optimizing controller parameters in complex landscapes. These findings confirm the effectiveness of the hybrid PSO-GA for multi-parameter controller tuning and reinforce the PR controller’s suitability for precision harmonic mitigation in GCI.

6.2. Error Base Statistical Analysis

Figure 15,

Figure 16,

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 provide a comprehensive analysis of the PR controller performance optimized using PSO, GA, and hybrid PSO-GA, focusing on current tracking error and overall control improvement.

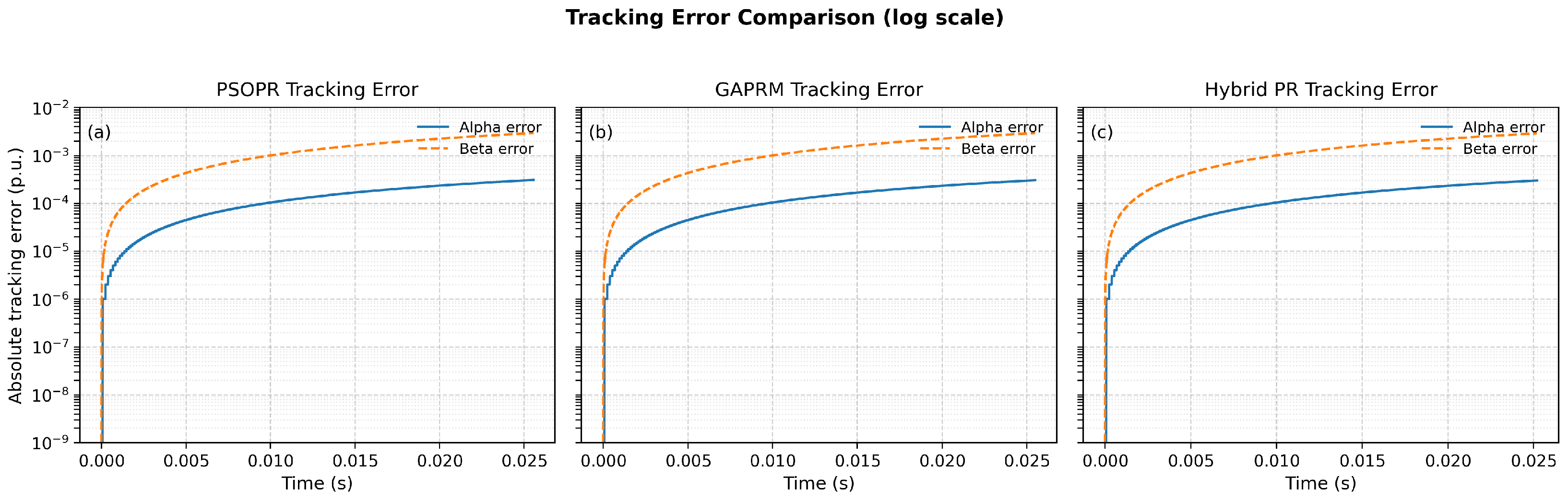

Figure 15 presents log-log plots comparing the current tracking error over a 25 ms simulation window for both the

- and

-axes. The first subplot illustrates the PSO-optimized PR controller performance, which exhibits the highest

-axis error, starting around

pu and increasing to

pu. The error remains of second order or lower along the

-axis. In contrast, the middle subplot demonstrates the GA-optimized controller, which achieves reduced errors on both axes compared to PSO, with a notably better performance along the

-axis. The third subplot highlights the hybrid PSO-GA, which outperforms both standalone PSO and GA in terms of convergence rate and learning behavior. It achieves significantly lower error magnitudes, confirming its superior tuning capability.

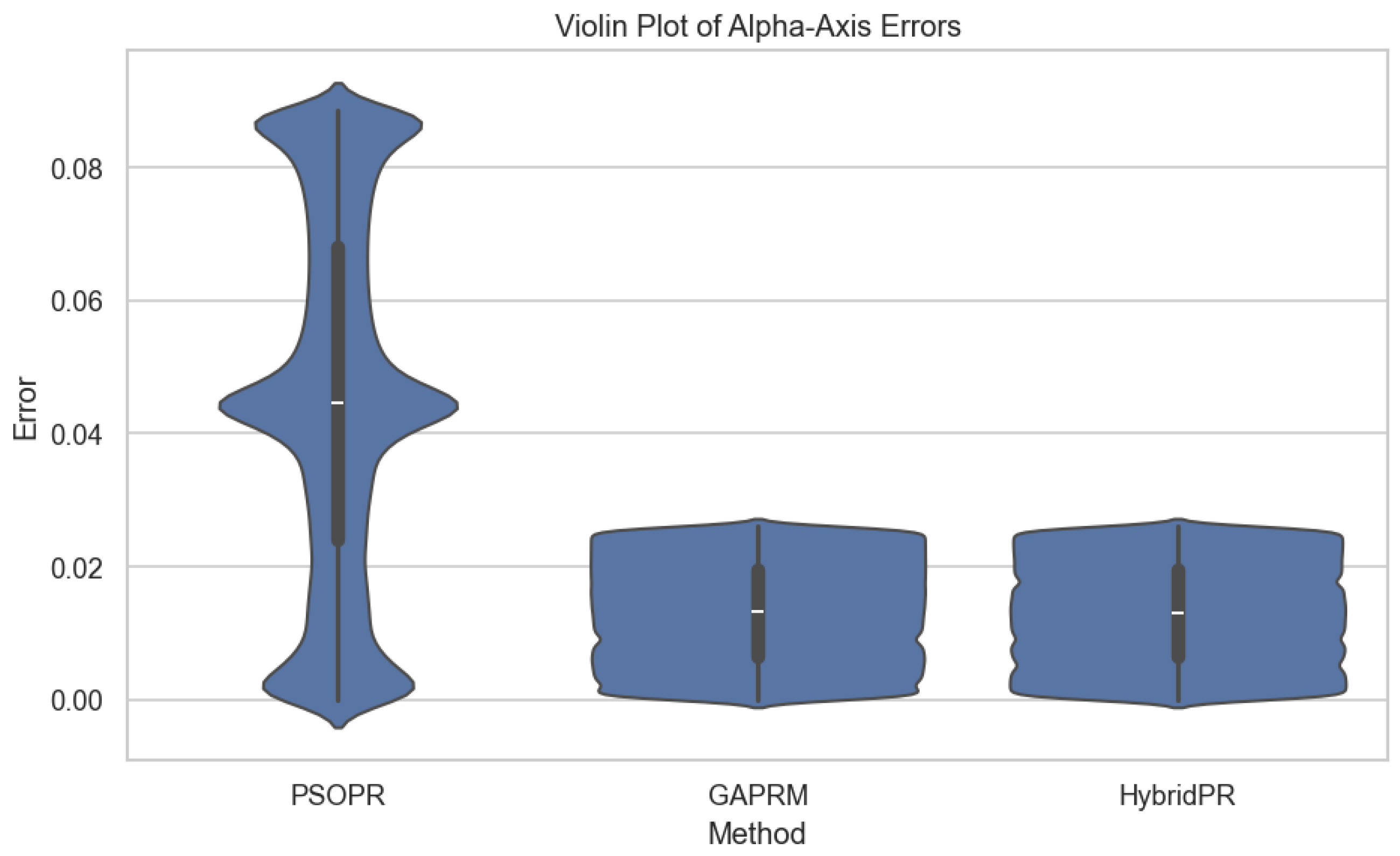

The absolute error distributions are visualized using violin plots in

Figure 16. For the PR controller, the PSO-based tuning yields a median error around 0.045 pu, while the GA and hybrid algorithms exhibit narrower distributions, reducing the

-axis error to approximately 0.015 pu. This indicates that PSO generates larger

-axis errors compared to GA and the hybrid approach.

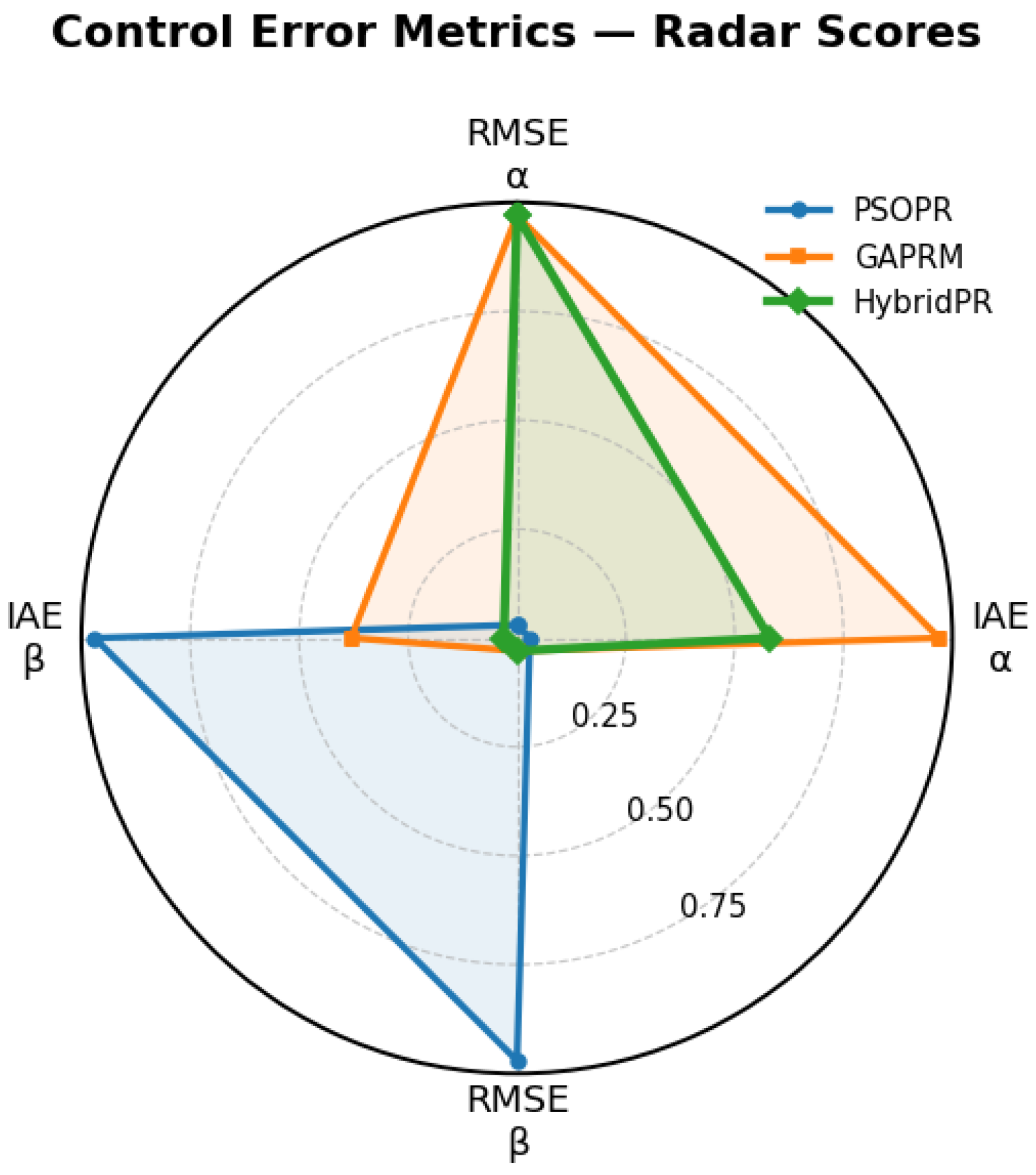

The performance trade-offs among the algorithms are visualized in the radar chart shown in

Figure 17, where the root mean square error (RMSE) and IAE are compared after normalizing each metric within the range [0, 1]. PSO displays the highest values for both RMSE and IAE, whereas the hybrid algorithm yields the lowest, demonstrating superior overall performance.

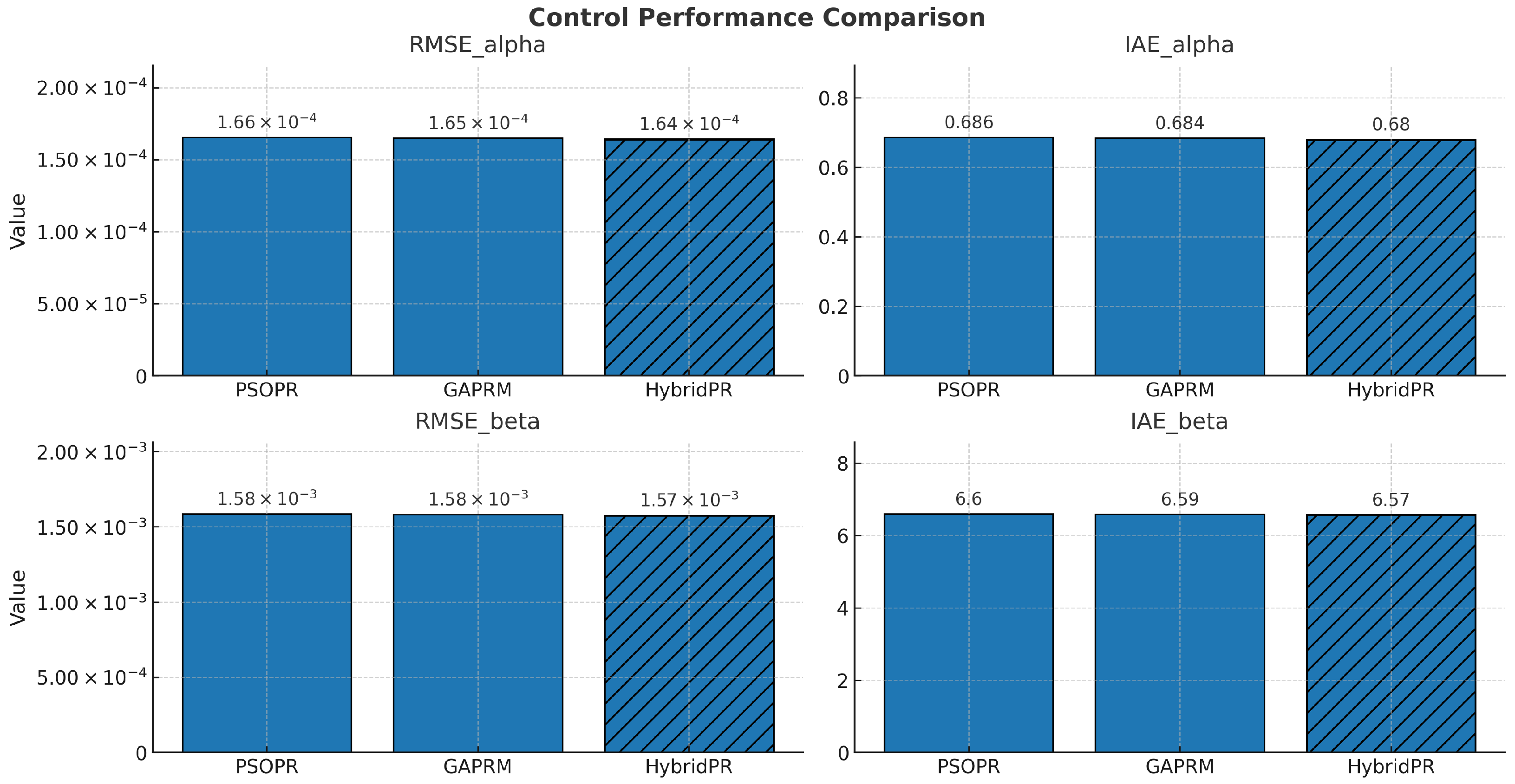

Additionally, the bar chart in

Figure 18 illustrates RMSE and IAE values separately for the

- and

-axes.Collectively, these results provide strong evidence that metaheuristic optimization techniques are effective in tuning PR controllers for current tracking. Furthermore, the hybrid PSO-GA, by leveraging the strengths of both individual methods, offers significantly improved tracking performance and reduced error metrics.

Speed and Convergence Behavior

In addition to control performance, the convergence behavior and computational efficiency of each optimization algorithm were assessed.

Table 6 summarizes the number of iterations required to achieve convergence and the total execution time for each algorithm.

The hybrid PSO-GA exhibits the fastest convergence for both PR and PI controllers, requiring three iterations and moderate execution times of 1419.40 s (PR) and 1474.95 s (PI). The PSO algorithm converges within three iterations for the PR controller but requires four iterations for the PI controller, accompanied by increased execution times. The GA demonstrates the slowest convergence and highest computational burden, necessitating six iterations and exceeding 2600 s for both controllers.

Optimization of the PI controller demands greater iterations and longer execution times than the PR controller, reflecting increased tuning complexity. The hybrid PSO-GA’s superior convergence rate and computational efficiency across both controllers substantiate its robustness and efficacy for multi-parameter optimization in harmonic mitigation. Notably, the PR controller achieves faster and more stable tuning relative to the PI controller.

7. Conclusions

A high-fidelity harmonic mitigation framework has been established for grid-connected two-level inverters operating in an unbalanced grid. The study benchmarked a PR controller against a conventional PI controller, each tuned by PSO, GA and a hybrid PSO–GA method. The hybrid PSO–GA produced the most favorable trade-off among THD, convergence speed and computation time for both controllers. For the PR configuration, THD is reduced to 1.0687%, meeting the IEEE1547 and IEC61727 limits. The same optimizer lowered PI-based THD to 2.696%, an improvement over standalone PSO (4.12%) and GA (3.38%), yet still above the PR benchmark. Optimal gains derived through hybrid tuning yielded the smallest error indices (IAE, ISE, ITAE, ITSE) in the frame for the PR controller and in the frame for the PI controller, confirming superior reference current tracking. Convergence analysis showed that hybrid PSO–GA reached optimal gains in three iterations for both controllers, matching PSO’s iteration count for PR while cutting execution time relative to GA. GA required six iterations and the longest runtime, whereas PSO exhibited rapid convergence but delivered suboptimal harmonic suppression, especially for the PI case. Unlike other conventional models, this study uses feeder-level EMT waveforms on an unbalanced IEEE 13-bus system. The comparative results highlight the following two key insights:

Controller architecture governs harmonic performance: The PR controller, equipped with resonant poles at the fundamental frequency, achieved approximately lower THD and an order-of-magnitude reduction in ISE compared with the optimized PI controller.

Hybrid metaheuristic tuning enhances both control strategies: The combination of PSO’s global exploration and GA’s local refinement consistently produced lower distortion and error metrics than either algorithm alone, without requiring additional iterations.

Residual harmonic components above 200 Hz persist, indicating the need for system-level mitigation that accounts for interactions between inverter-generated harmonics and those from nonlinear loads. Future research should focus on dynamic testing under non-ideal operating conditions, including load switching events, fault ride-through scenarios, and stochastic fluctuations from renewable energy sources. Such studies will further establish the robustness and reliability of the proposed method in real-world grid- connected environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.D. and T.M.G.; methodology, P.D. and T.M.G.; software, P.D.; validation, P.D., T.M.G. and S.L.; formal analysis, P.D.; investigation, P.D.; resources, O.B.; data curation, P.D.; writing—original draft preparation, P.D.; writing—review and editing, T.M.G., S.L. and O.B.; visualization, P.D.; supervision, T.M.G. and O.B.; project administration, T.M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Singh, M.K.; Malek, J.; Sharma, H.K.; Kumar, R. Converting the threats of fossil fuel-based energy generation into opportunities for renewable energy development in India. Renew. Energy 2024, 224, 120153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, J. A century-long analysis of global warming and earth temperature using a random walk with drift approach. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 7, 100237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielen, D.; Boshell, F.; Saygin, D.; Bazilian, M.D.; Wagner, N.; Gorini, R. The role of renewable energy in the global energy transformation. Energy Strategy Rev. 2019, 24, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wu, S.; Xu, J. Synergy between pollution control and carbon reduction: China’s evidence. Energy Econ. 2023, 119, 106541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, B.; Zuo, C.; Mao, L.; Huang, B.; Wang, X. Security energy management of microgrids including PHEV subject to high penetration of renewable energy sources. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 268, 126207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cergibozan, R. Renewable energy sources as a solution for energy security risk: Empirical evidence from OECD countries. Renew. Energy 2022, 183, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegireddy, N.K.R.; Kunduru, S.R.; Choppavarapu, S.B. 11-Power electronic converters for distributed energy storage systems. In Distributed Energy Storage Systems for Digital Power Systems; Palanisamy, S., Chenniappan, S., Padmanaban, S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 239–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehimi, S.; Bevrani, H.; Kato, T.; Kato, T. Chapter 18—Grid connected converters in power grids systems: A systematic review on impacts and challenges. In Energy Efficiency of Modern Power and Energy Systems; Abdel Aleem, S.H., Erhan Balci, M., Rawa, M.J.H., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 415–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shan, Y.; Cheng, K.W.; Islam, S. Overview of Power Converter Control in Microgrids—Challenges, Advances, and Future Trends. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 9907–9922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabash, A. Review of Battery Storage and Power Electronic Systems in Flexible A-R-OPF Frameworks. Electronics 2023, 12, 3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farivar, G.G.; Manalastas, W.; Tafti, H.D.; Ceballos, S.; Sanchez-Ruiz, A.; Lovell, E.C.; Konstantinou, G.; Townsend, C.D.; Srinivasan, M.; Pou, J. Grid-Connected Energy Storage Systems: State-of-the-Art and Emerging Technologies. Proc. IEEE 2023, 111, 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Hou, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, B.; Wu, Y. A Modular Multiport DC Power Electronic Transformer Based on Triple-Active-Bridge for Multiple Distributed DC Units. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 15191–15205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rönnberg, S.; Bollen, M. Power quality issues in the electric power system of the future. Electr. J. 2016, 29, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparza, M.; Segundo, J.; Núñez, C.; Wang, X.; Blaabjerg, F. A Comprehensive Design Approach of Power Electronic-Based Distributed Generation Units Focused on Power-Quality Improvement. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2017, 32, 942–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayagam, A.; Aziz, A.; PM, B.; Chandran, J.; Veerasamy, V.; Gargoom, A. Harmonics assessment and mitigation in a photovoltaic integrated network. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2019, 20, 100264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owosuhi, A.; Hamam, Y.; Munda, J. Maximizing the Integration of a Battery Energy Storage System–Photovoltaic Distributed Generation for Power System Harmonic Reduction: An Overview. Energies 2023, 16, 2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; Ma, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S. Optimization model for harmonic mitigation based on PV-ESS collaboration in small distribution systems. Appl. Energy 2024, 356, 122410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wannous, K.; Toman, P. Evaluation of Harmonics Impact on Digital Relays. Energies 2018, 11, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushra, E.; Zeb, K.; Ahmad, I.; Khalid, M. A comprehensive review on recent trends and future prospects of PWM techniques for harmonic suppression in renewable energies based power converters. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, A.; Chowdhuri, S. Development of Hybrid SOGI-Resonant Controller in DQ reference frame for decoupled PQ control of a VSI under nonlinear loading. Electr. Eng. 2025, 107, 3359–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valedsaravi, S.; Aroudi, A.E.; Barrado-Rodrigo, J.A.; Hamzeh, M.; Martínez-Salamero, L. Multi-resonant Controller Design for a PV-Fed Multifunctional Grid-Connected Inverter in Presence of Unbalanced and Nonlinear Load. J. Control. Autom. Electr. Syst. 2023, 34, 766–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, Y. Power-current coordinated control without sequence extraction under unbalanced voltage conditions. IET Power Electron. 2020, 13, 2274–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojić, D.; Šekara, T. Multi-resonant current controller for grid-tied inverters with LCL filters based on pole placement under robustness constraints. J. Power Electron. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurkevich, V. Resonant PID Controller Design for a Three-Phase Four-Wire Voltage Inverter with Split DC Buses. Optoelectron. Instrum. Process. 2022, 58, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beddar, A.; Abadlia, I.; Abdoune, F.; Hassaine, L.; Bengourina, M.R. Investigation and implementation of a nonlinear decoupled power control for a single-phase grid-connected power inverter via an LCL filter. J. Eng. Res. 2023, 11, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, B.; Rastegar, H.; Pichan, M. An optimized proportional resonant current controller based genetic algorithm for enhancing shunt active power filter performance. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 156, 109738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Yan, Y.; Wu, F.; Sun, Z.; Farooq, A.; Xu, W. Parameter co-design of active damping loop and grid current controller for a 3-phase LCL-filtered grid-connected inverter. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 133, 107203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, K.; Busarello, T.; Uddin, W.; Khalid, M. An Improved digital multi-resonant controller for 3 phase grid-tied and standalone PV system under balanced and unbalanced conditions. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 103036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Hu, K.; Zhuang, B.; Zhang, M.; Han, G. Design and implementation of an improved adaptive embedded-factor current controller for three-phase grid-connected inverter. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 234, 110558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Peng, L.; Liu, X. Selective Pole Placement and Cancellation for Proportional–Resonant Control Design Used in Voltage Source Inverter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 8921–8934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busada, C.A.; Jorge, S.G.; Solsona, J.A. Resonant Current Controller With Enhanced Transient Response for Grid-Tied Inverters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 2935–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, A.A.; Narayanan, V.; Singh, B. A Frequency Adaptive Ramp-Rate Based PR Controller for Seamless Transition of Three-Phase AC Microgrid Between SA to GI Modes. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2024, 60, 4786–4795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, C.S.; Puttamadappa, C.; Chandrashekar, Y. Power Quality Improvement in Grid Integrated PV Systems with SOA Optimized Active and Reactive Power Control. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2023, 18, 735–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, Z.; Zhu, J.; Husev, O.; Vinnikov, D.; Yu, L. Proportional Resonant Controller Tuning in Three-Phase Four-Leg VSI Based on Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 19th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference (PEMC), Gliwice, Poland, 25–29 April 2021; pp. 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.P.; Kanakasabapathy, P. PR controller-based droop control strategy for AC microgrid using Ant Lion Optimization technique. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 6189–6198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, S.; Suganyadevi, M. Performance Analysis of Simplified Seven-Level Inverter using Hybrid HHO-PSO Algorithm for Renewable Energy Applications. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. A Electr. Eng. 2024, 48, 781–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Wei, W.; Peng, Y.; Lei, J. Optimized design of damped proportional-resonant controllers for grid-connected inverters through genetic algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Power Electronics and Application Conference and Exposition, Shanghai, China, 5–8 November 2014; pp. 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhammash, H.; Satti, L.; Ahmad, N.; Althobaiti, A.; Ullah, N.; Babqi, A.; Ibeas, A. Optimization of proportional resonant and proportional integral controls using particle swarm optimization technique for PV grid tied inverter. Math. Model. Eng. Probl. 2023, 10, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugapriya, M.; Mayurappriyan, P.; Lakshmi, K. Firefly-optimized PI and PR controlled single-phase grid-linked solar PV system to mitigate the power quality and to improve the efficiency of the system. Electr. Eng. 2024, 107, 6827–6849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, M.A.; Aziz, B.A.; Nashed, M.N.F.; Osman, F.A. Optimal design of proportional-resonant controller and its harmonic compensators for grid-integrated renewable energy sources based three-phase voltage source inverters. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2021, 15, 1371–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyab, M.; Sarwar, A.; Murshid, S.; Tariq, M.; Al-Durra, A.; Bakhsh, F.I. Active and reactive power control of grid-connected single-phase asymmetrical eleven-level inverter. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2023, 17, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurrola-Corral, C.; Segundo, J.; Esparza, M.; Cruz, R. Optimal LCL-filter design method for grid-connected renewable energy sources. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 120, 105998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, H. Optimal design of LCL filter in grid-connected inverters. IET Power Electron. 2019, 12, 1774–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, H.H.; Shafiee, Q.; Bevrani, H. Optimal passive LCL filter design for grid-connected converters in weak grids. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 235, 110896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saïd-Romdhane, M.B.; Naouar, M.; Belkhodja, I.S.; Monmasson, E. Simple and systematic LCL filter design for three-phase grid-connected power converters. Math. Comput. Simul. 2016, 130, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 61727; Photovoltaic (PV) Systems–Characteristics of the Utility Interface. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- IEEE Std 1547-2018 (Revision of IEEE Std 1547-2003); IEEE Standard for Interconnection and Interoperability of Distributed Energy Resources with Associated Electric Power Systems Interfaces. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Overview of the control strategy for the PR controller.

Figure 1.

Overview of the control strategy for the PR controller.

Figure 2.

IEEE 13-bus system topology with grid-connected inverter-based distributed generation.

Figure 2.

IEEE 13-bus system topology with grid-connected inverter-based distributed generation.

Figure 3.

Block diagram of LCL filter.

Figure 3.

Block diagram of LCL filter.

Figure 4.

Block diagram of close current loop control.

Figure 4.

Block diagram of close current loop control.

Figure 5.

Flowchart of the hybrid algorithm implementation.

Figure 5.

Flowchart of the hybrid algorithm implementation.

Figure 6.

Phase-wise load distribution across the IEEE 13-bus feeder.

Figure 6.

Phase-wise load distribution across the IEEE 13-bus feeder.

Figure 7.

(a) FFT analysis of Phase A inverter output current; (b) harmonic distortion of phase current across harmonic orders.

Figure 7.

(a) FFT analysis of Phase A inverter output current; (b) harmonic distortion of phase current across harmonic orders.

Figure 8.

VUF at different buses with PR and PI controllers.

Figure 8.

VUF at different buses with PR and PI controllers.

Figure 9.

VDI at different buses with PR and PI controllers.

Figure 9.

VDI at different buses with PR and PI controllers.

Figure 10.

Optimized three phase inverter current.

Figure 10.

Optimized three phase inverter current.

Figure 11.

(a) Optimized phase A inverter current (b) Result of FFT analysis on phase A inverter current.

Figure 11.

(a) Optimized phase A inverter current (b) Result of FFT analysis on phase A inverter current.

Figure 12.

FFT analysis of inverter current with Hybrid PSO-GA optimized PR-controller.

Figure 12.

FFT analysis of inverter current with Hybrid PSO-GA optimized PR-controller.

Figure 13.

FFT analysis of inverter current with PSO optimized PR-controller.

Figure 13.

FFT analysis of inverter current with PSO optimized PR-controller.

Figure 14.

FFT analysis of inverter current with GA optimized PR-controller.

Figure 14.

FFT analysis of inverter current with GA optimized PR-controller.

Figure 15.

Log-scale current tracking error for each optimization algorithm: (a) PSO-tuned PR controller, (b) GA-tuned PR controller, and (c) Hybrid-tuned PR controller.

Figure 15.

Log-scale current tracking error for each optimization algorithm: (a) PSO-tuned PR controller, (b) GA-tuned PR controller, and (c) Hybrid-tuned PR controller.

Figure 16.

Violin plot of -axis current tracking error.

Figure 16.

Violin plot of -axis current tracking error.

Figure 17.

Radar chart of normalized control performance metrics.

Figure 17.

Radar chart of normalized control performance metrics.

Figure 18.

Comparison of RMSE and IAE in - and -frames.

Figure 18.

Comparison of RMSE and IAE in - and -frames.

Table 1.

PR-Family controller performance and reported drawbacks.

Table 1.

PR-Family controller performance and reported drawbacks.

| Ref | Year | Control | Hybrid † | Technique | THD (%) | Settling Time | Optimization | Drawbacks |

|---|

| [23] | 2025 | Multi-resonant PR current controller | × | MR-PR | 1.56 | 3.5 ms | Pole placement | Multi-loop structure raises implementation complexity and sensor count requirements |

| [24] | 2022 | Resonant PID (PIR) voltage tracker | × | PIR | not specified | not specified | Manual tuning | High frequency PWM pulsations cause saturation; unmodeled delays can destabilize the loop |

| [25] | 2023 | Nonlinear decoupled (inner P-MR, outer IP-AW) | ✓ | PI + PR | not specified | not specified | Nyquist gain sweep | Anti-windup still slows step response when power commands saturate |

| [26] | 2024 | GA optimized PR for shunt APF | × | PR | 4.2 / 4.5 | ≈4 ms | Genetic Algorithm | GA search is large & time consuming; no real hardware validation in prior work |

| [27] | 2021 | Active damping co-designed HR-PR | ✓ | HR-PR | ∼1.5 | not specified | Analytic co-design | Performance sensitive to LCL, resonance shift co-design needed for every filter |

| [28] | 2024 | Digital PR + resonant harmonic compensator (PV SAPF) | ✓ | PR + RHC | not specified | <5 ms | FPSO (PV side) gains hand tuned | Harmonic-loop gains still tuned manually; mode switch logic adds control overhead |

| [29] | 2024 | Adaptive-factor PI-R current regulator | × | PI-R | 1.72 | 2.5 ms | Online adaptive | Nonlinear adaptive factor complicates practical realization |

| [30] | 2022 | Selective pole placement PR with 5th/7th HR loops | × | PR + HR | 2.5 | 2.1 ms | Pole placement | Extra HR loops increases order & on chip load; relies on reduced order approximation |

| [31] | 2018 | Transient enhanced PR (L filter inverter) | × | PR | not specified | 2.8 ms | Classical design | Classic PR shows limited transient bandwidth; digital delay increases system order |

| [32] | 2024 | Frequency-adaptive ramp-rate PR (SA→GI) | × | PR | <5 | not specified | Manual freq. domain | Needs accurate frequency estimator; low selected to keep phase margin |

| [33] | 2023 | SOA optimized control of modular MMI PV inverter | ✓ | PI/PR | 3–4 | not specified | SOA + BFOA | Heuristics incur long convergence; modular hardware adds communication load |

| [34] | 2021 | PSO tuned PR (outer V, inner I) for 4 leg VSI | ✓ | Dual loop PR + PI | qualitative | not specified | PSO | Only qualitative THD; PSO parameters sensitive to initial guess (self stated) |

| [35] | 2023 | Droop controlled G with PR inner loop (ALO optimized ) | ✓ | Droop + PR | not specified | not specified | Ant Lion Opt. | ALO design still shows 52% overshoot; slower than PSO alternative |

| [36] | 2024 | 7-level SHE-PWM inverter (HHO–PSO angle opt.) | × | Openloop SHE | 2.58 / 1.49 | not specified | HHO–PSO | Offline angle table; open loop lacks feedback sensitive to dc link imbalance |

| [37] | 2014 | Damped PR with weighted current feedback (LC grid) | × | PR current loop | 1.56–1.74 | 2.5 ms | Genetic Algorithm | GA tuning heavy; paper does not test under grid fault disturbances |

| [38] | 2023 | PSO optimized PI & PR for PV grid tie | × | PR current+PI dc | 1.93 | not specified | PSO | Fixed gain PID not robust; PSO may get stuck in local minima, slowing tuning |

| [39] | 2025 | Firefly optimized dual loop PI/PR (PV) | ✓ | Dual loop PI/PR | 3.76 / 4.10 | 160 ms | Firefly Algorithm | 160 ms rise/settle still high; optimization time vs. GA/PSO not benchmarked |

| [40] | 2021 | PR + 5th–17th HC (HHO-tuned) | ✓ | Multi resonant PR | 2.94 | not specified | Harris Hawks Opt. | Tuning many HCs is time consuming; ideal PR infinite-gain needs added damping |

Table 2.

Taxonomy of mathematical symbols and parameters with units.

Table 2.

Taxonomy of mathematical symbols and parameters with units.

| Symbol | Description (Units) | Symbol | Description (Units) |

|---|

| Currents and Voltages |

| Inverter, grid, capacitor currents (A) | | Inverter output, capacitor, grid voltages (V) |

| Instantaneous active/reactive power (W, var) | | |

| LCL Filter and Grid Elements |

| Inverter-side inductance/resistance (H, ) | | Grid-side inductance/resistance (H, ) |

| Shunt capacitance, damping resistor (F, ) | | Grid inductance/resistance (H, ) |

| r | Inductance ratio (–) | | |

| Frequencies |

| Grid and switching angular freq. (rad/s) | | LCL resonance frequency (rad/s) |

| Fundamental freq. in PR design (rad/s) | | PR core / HC bandwidths (rad/s) |

| Controller Gains |

| PR proportional gains () | | PR gains () |

| PI proportional gains () | | PI integral gains () |

| Optimization Parameters |

| GA population, generations; PSO iterations | | PSO cognitive, social coeffs; inertia weight |

| GA crossover and mutation probabilities | | THD threshold for early stopping (%) |

| Design and Performance |

| DC-link voltage (V) | | Rated inverter current (A) |

| Switching frequency (Hz) | | Ripple-attenuation factor (–) |

| Base impedance / capacitance (, F) | | Capacitance scaling factor (–) |

| THD | Total harmonic distortion of inverter current (%) | | |

Table 3.

Key parameters of the two-level inverter and simulation setup.

Table 3.

Key parameters of the two-level inverter and simulation setup.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|

| Filter inductance, (p.u.) | 0.0547 |

| Grid-side inductance, (p.u.) | 0.0301 |

| Shunt capacitance, (F) | 10 |

| Switching frequency, (kHz) | 10 |

| Sampling frequency, (kHz) | 10 |

| DC-link voltage, (V) | 1000 |

| Grid voltage (rms) (V) | 480 |

| Grid frequency, (Hz) | 50 |

| Converter rating (kVA) | 10 |

| EMT time step (s) | s |

Table 4.

Optimized gain parameters and THD.

Table 4.

Optimized gain parameters and THD.

| Ctrl. | Algorithm | | | | | THD (%) |

|---|

| PR controller |

| | PSO | 0.001888 | 0.001739 | 0.000776 | 0.003215 | 1.5060 |

| | GA | 0.001235 | 0.000682 | 0.001570 | 0.002607 | 1.2390 |

| | PSO–GA | 0.000705 | 0.001143 | 0.003123 | 0.003712 | 1.0624 |

| PI controller |

| | PSO | 0.0091 | 0.0034 | 0.00022 | 0.00207 | 4.1200 |

| | GA | 0.0100 | 0.00009 | 0.00009 | 0.0100 | 3.3800 |

| | PSO–GA | 0.0100 | 0.00010 | 0.0100 | 0.00010 | 2.6960 |

Table 5.

Error metric evaluation for optimized PR and PI controllers.

Table 5.

Error metric evaluation for optimized PR and PI controllers.

| Controller | Axis | Metric | PSO | GA | Hybrid PSO-GA |

|---|

| PR | Alpha | IAE | 0.0889 | 0.0260 | 0.0260 |

| ISE | 0.1201 | 0.00045 | 0.00045 |

| ITAE | 0.0347 | 0.0347 | 0.0347 |

| ITSE | 0.00068 | 0.00068 | 0.00068 |

| Beta | IAE | 0.000543 | 0.2507 | 0.2507 |

| ISE | 0.0082 | 0.0419 | 0.0419 |

| ITAE | 0.0334 | 0.0334 | 0.0334 |

| ITSE | 0.0629 | 0.0629 | 0.0629 |

| PI | d-axis | IAE | 0.8202 | 0.4872 | 0.4454 |

| ISE | 1.7711 | 0.4166 | 0.3461 |

| ITAE | 0.4342 | 0.2510 | 0.2329 |

| ITSE | 0.9645 | 0.2174 | 0.1826 |

| q-axis | IAE | 0.7770 | 0.6452 | 0.4736 |

| ISE | 2.2402 | 0.8175 | 0.4500 |

| ITAE | 0.4252 | 0.3505 | 0.2672 |

| ITSE | 1.2998 | 0.4905 | 0.2828 |

Table 6.

Convergence iteration and execution time for controller optimization.

Table 6.

Convergence iteration and execution time for controller optimization.

| Controller | Algorithm | Convergence

(Iterations) | Execution

Time (s) |

|---|

| PR | PSO | 3 | 1253.40 |

| GA | 6 | 2656.17 |

| PSO-GA | 3 | 1419.40 |

| PI | PSO | 4 | 1566.60 |

| GA | 6 | 2749.90 |

| PSO-GA | 3 | 1474.95 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).