Micronized Prinsepia utilis Royle Seed Powder as a Natural, Antioxidant-Enriched Pickering Stabilizer for Green Cosmetic Emulsions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Treatment of Prinsepia utilis Royle Seed Residue Powder

2.3. Characterization of RPURSRP and MPURSRP

2.3.1. Image Analysis-Based Particle Size Measurement

2.3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.3.3. Measurement of Three-Phase Contact Angle

2.3.4. Determination of Interfacial Tension

2.3.5. Preparation of Emulsions and the Determination of Emulsifying Ability of MPURSRP

2.3.6. Determination of Type for the Prepared Emulsions

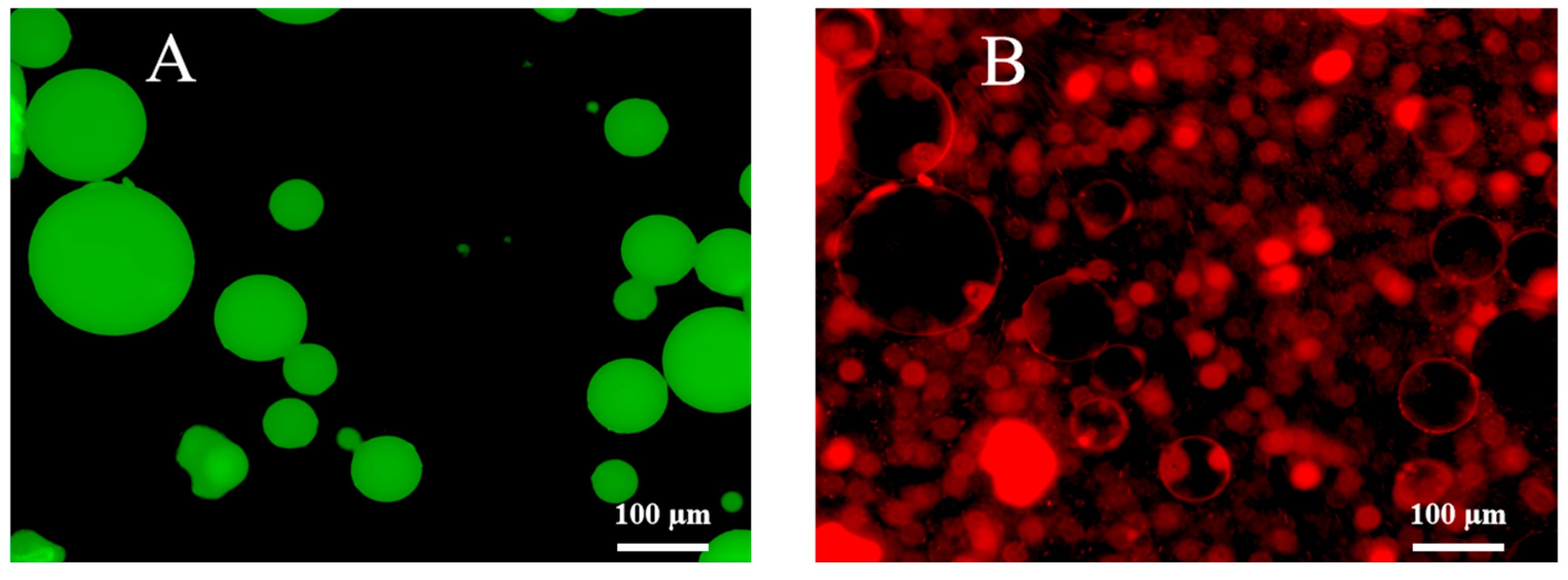

2.3.7. Microscope Observations

2.3.8. The Stability Test

2.3.9. Determination of Antioxidant Activity

2.3.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of RPURSRP and MPURARP

3.2. The Emulsifying Property of MPURSRP

3.3. The Wettability of MPURSRP

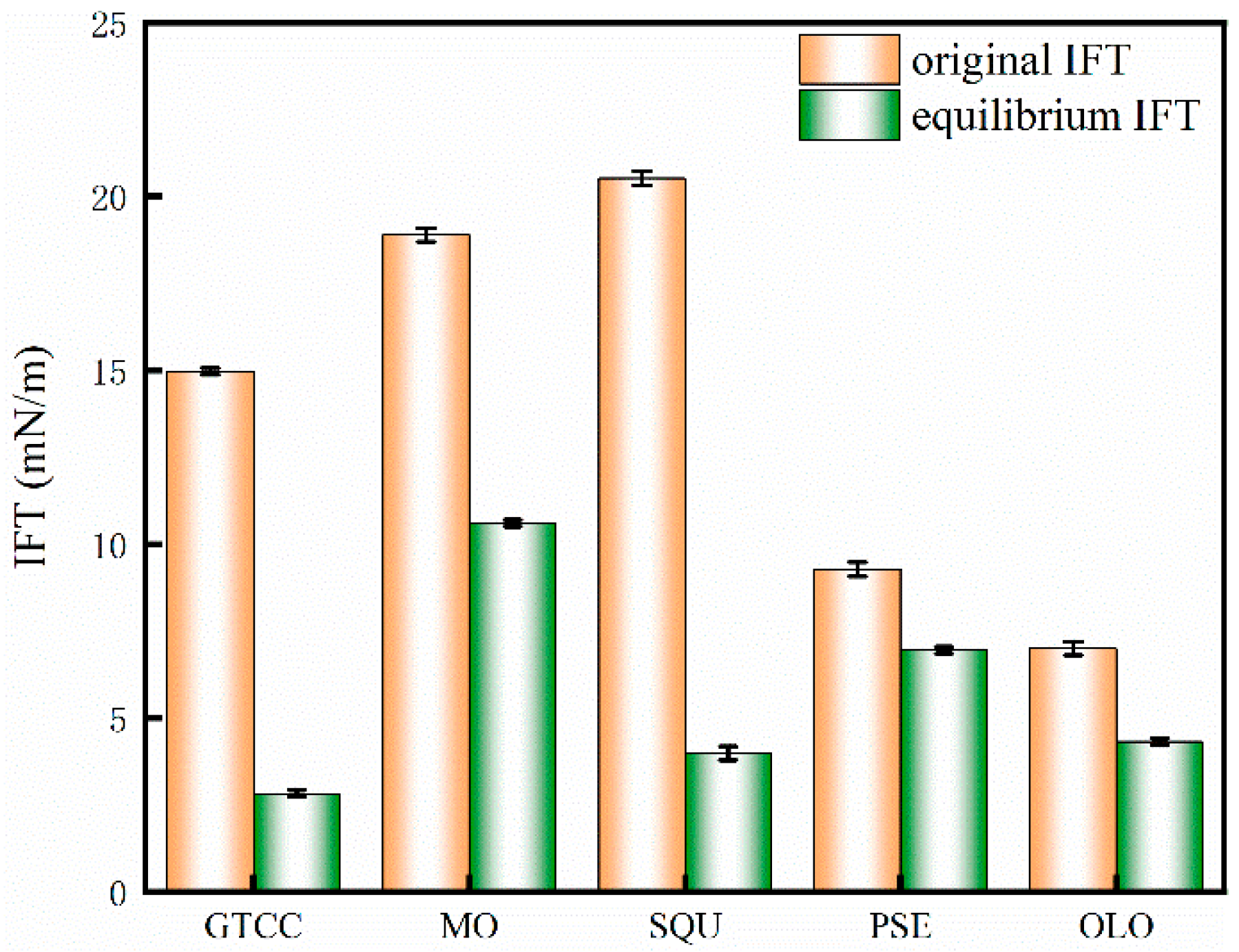

3.4. The Interfacial Activity of MPURSRP

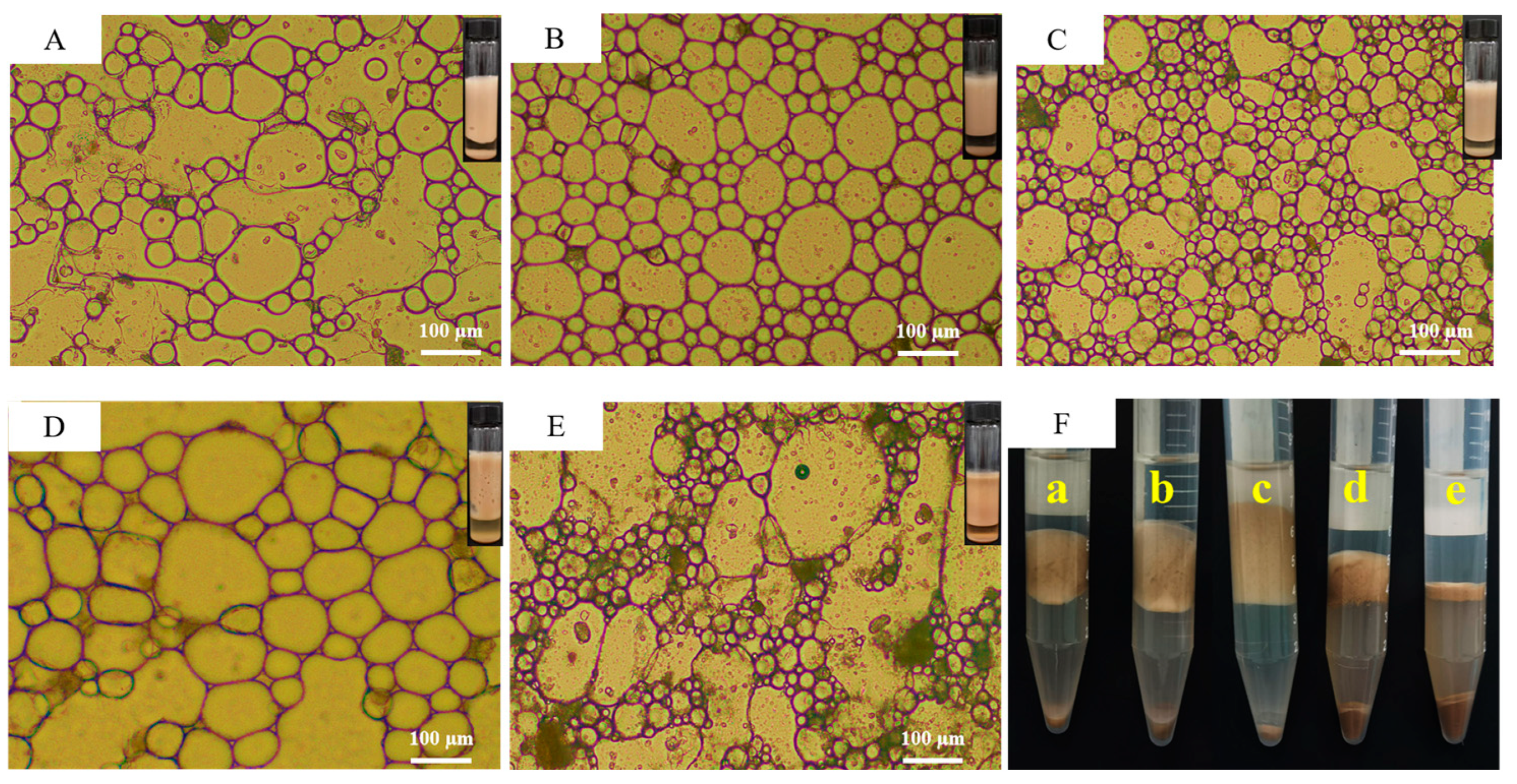

3.5. Influence of MPURSRP Concentrations on Emulsions

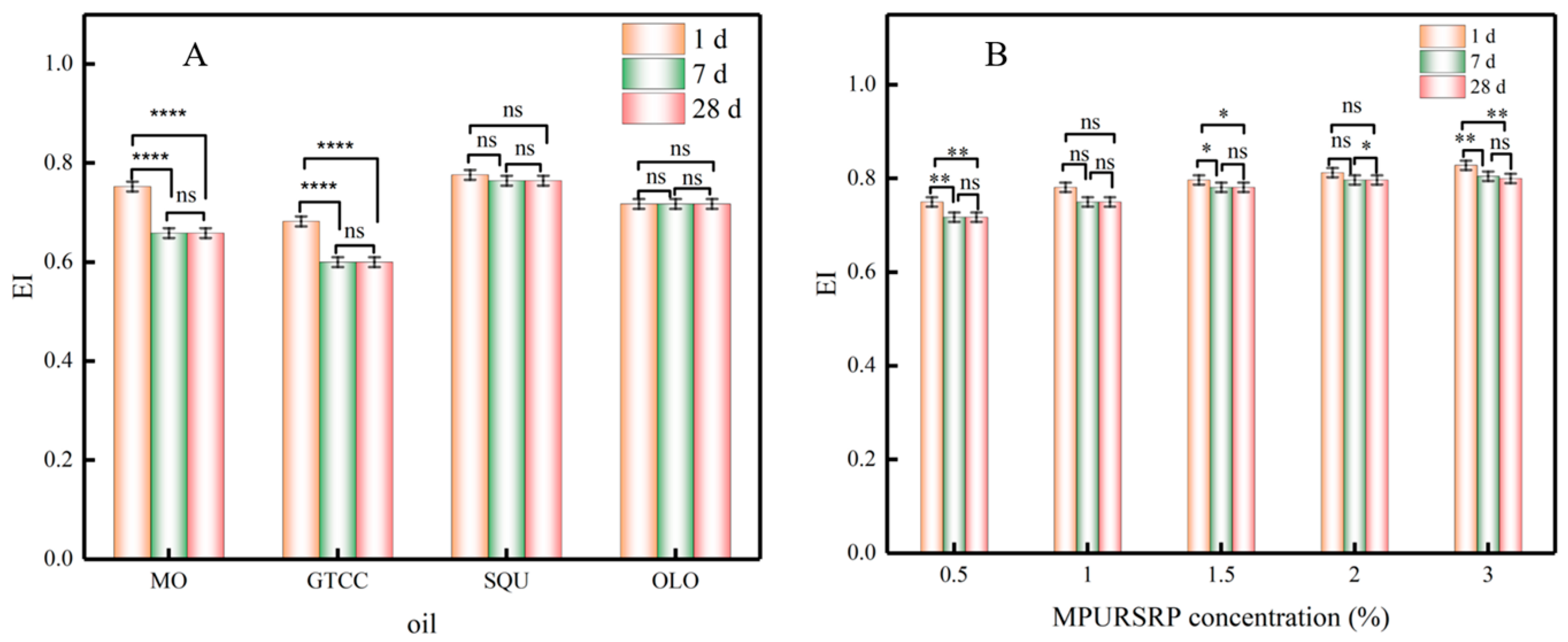

3.6. The Emulsion Index of Emulsions

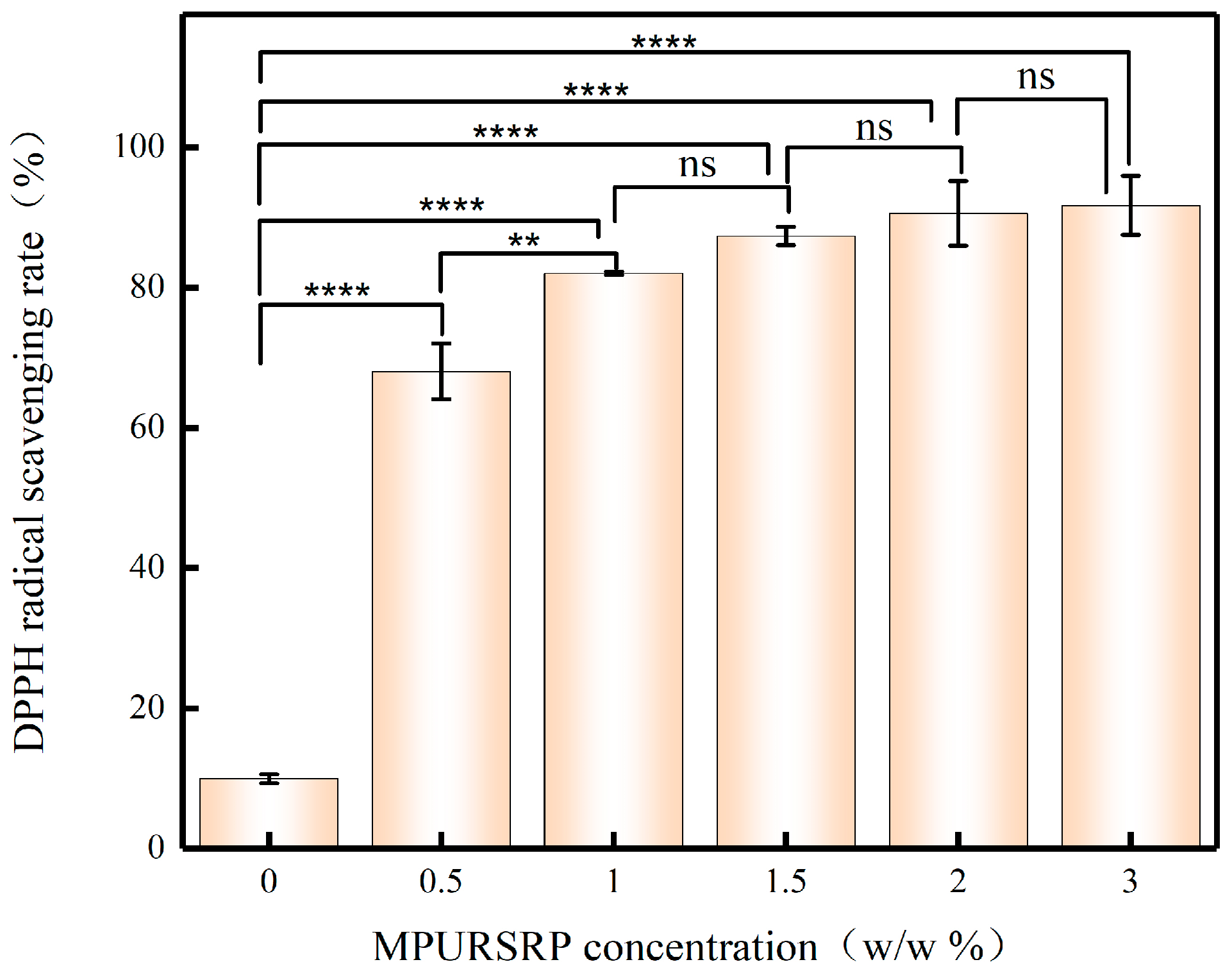

3.7. Antioxidant Efficacy of Emulsions Prepared by MPURSRP

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pickering, S.U. CXCVI.—Emulsions. J. Chem. Soc. Trans. 1907, 91, 2001–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Niu, Z.; Wang, F.; Feng, K.; Zong, M.; Wu, H. A novel Pickering emulsion system as the carrier of tocopheryl acetate for its application in cosmetics. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 109, 110503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Yan, X.; Xiao, Y.; Hu, L.; Weitz, D. Pickering emulsions stabilized by colloidal surfactants: Role of solid particles. Particuology 2021, 64, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Xuan, C.; Zhang, W.; Xie, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, W. An Overview of Pickering Emulsions: Solid-Particle Materials, Classification, Morphology, and Applications. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Q.; Yi, Z.; Ma, L.; Tan, Y.; Liu, D.; Cao, X.; Ma, X.; Li, X. Microenvironment-Responsive Antibacterial, Anti-Inflammatory, and Antioxidant Pickering Emulsion Stabilized by Curcumin-Loaded Tea Polyphenol Particles for Accelerating Infected Wound Healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 44467–44484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Chen, L.; Lin, R.; Zhang, P.; Lan, K.; Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Zhao, D. Interfacial Assembly Directed Unique Mesoporous Architectures: From Symmetric to Asymmetric. Acc. Mater. Res. 2020, 1, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Bhardwaj, K.; Sharma, R.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuča, K.; Dhanjal, D.S.; Verma, R.; Bhardwaj, P.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, D. Fruit and Vegetable Peels: Utilization of High Value Horticultural Waste in Novel Industrial Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, T.B.N.; Ferreira, M.S.L.; Fai, A.E.C. Utilization of Agricultural By-products: Bioactive Properties and Technological Applications. Food Rev. Int. 2022, 38, 1305–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre-Hernández, A.-B.; Vicente-López, J.-J.; Pérez-Llamas, F.; Candela-Castillo, M.-E.; García-Conesa, M.-T.; Frutos, M.-J.; Cano, A.; Hernández-Ruiz, J.; Arnao, M.B.; Maestre-Hernández, A.-B.; et al. Antioxidant Activity, Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Contents in Floral Saffron Bio-Residues. Processes 2023, 11, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegorin Brasil, G.S.A.; Borges, F.A.; Machado, A.d.A.; Mayer, C.R.M.; Udulutsch, R.G.; Herculano, R.D.; Funari, C.S.; dos Santos, A.G.; Santos, L.; Pegorin Brasil, G.S.A.; et al. A Sustainable Raw Material for Phytocosmetics: The Pulp Residue from the Caryocar brasiliense Oil Extraction. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2022, 32, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shi, C.; Gao, L.-Z. Plastid genome sequence of a wild woody oil species, Prinsepia utilis, provides insights into evolutionary and mutational patterns of Rosaceae chloroplast genomes. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, Z.; Lang, B.; Wu Meng, M.S.; Xue, D.; Gao, L.; Yang, L. Skincare plants of the Naxi of NW Yunnan, China. Plant Divers. 2020, 42, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maikhuri, R.K.; Parshwan, D.S.; Kewlani, P.; Negi, V.S.; Rawat, S.; Rawat, L.S. Nutritional Composition of Seed Kernel and Oil of Wild Edible Plant Species from Western Himalaya, India. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2021, 21, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, F.; Gao, H. Prinsepia Utilis Royle Oil Extract Improve Skin Barrier on Reconstructed Skin Model. Int. J. Nurs. Health Care Res. 2022, 5, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, B.; Li, T.; Xu, X.-K.; Zhang, X.-F.; Wei, P.-L.; Peng, C.-C.; Fu, J.-J.; Zeng, Q.; Cheng, X.-R.; Zhang, S.-D.; et al. γ-Hydroxynitrile glucosides from the seeds of Prinsepia utilis. Phytochemistry 2014, 105, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagale, R.; Acharya, S.; Gupta, A.; Chaudhary, P.; Chaudhary, G.P.; Pandey, J.; Borquaye, L.S. Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities of Prinsepia utilis Royle Leaf and Seed Extracts. J. Trop. Med. 2022, 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.T.; Cachola, I.; Pinto, J.F.; Paudel, A. Understanding Carrier Performance in Low-Dose Dry Powder Inhalation: An In Vitro–In Silico Approach. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staehlke, S.; Rebl, H.; Finke, B.; Mueller, P.; Gruening, M.; Nebe, J.B. Enhanced calcium ion mobilization in osteoblasts on amino group containing plasma polymer nanolayer. Cell Biosci. 2018, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, N.; Ye, Z.; Zhou, K.; Wang, F.; Lian, C.; Shang, Y. Construction and Properties of O/W Liquid Crystal Nanoemulsion. Langmuir 2024, 40, 7723–7732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marefati, A.; Matos, M.; Wiege, B.; Haase, N.U.; Rayner, M. Pickering emulsifiers based on hydrophobically modified small granular starches Part II—Effects of modification on emulsifying capacity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 201, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Ye, F.; Zhou, G.; Gao, R.; Qin, D.; Zhao, G. Micronized apple pomace as a novel emulsifier for food O/W Pickering emulsion. Food Chem. 2020, 330, 127325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ossa, J.S.H.; Wagner, J.R.; Palazolo, G.G. Impact of environmental stresses on the stability of acidic oil-in-water emulsions prepared with tofu whey concentrates. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Ao, F.; Ge, X.; Shen, W.; Chen, L.; Ao, F.; Ge, X.; Shen, W. Food-Grade Pickering Emulsions: Preparation, Stabilization and Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Yang, L.; Tu, R.; Huo, J.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Chen, D. Emulsion phase inversion from oil-in-water (1) to water-in-oil to oil-in-water (2) induced by in situ surface activation of CaCO3 nanoparticles via adsorption of sodium stearate. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2015, 477, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, D.G.; Pochat-Bohatier, C.; Cambedouzou, J.; Bechelany, M.; Miele, P. Current Trends in Pickering Emulsions: Particle Morphology and Applications. Engineering 2020, 6, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Hou, W.; Zhao, H. Silica particles with dynamic Janus surfaces in Pickering emulsion. Polymer 2022, 240, 124487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Zhao, X.; Yang, S.; He, F.; Qin, W.; Gong, H.; Yu, G.; Feng, Y.; Li, J. Interfacial regulation and visualization of Pickering emulsion stabilized by Ca2+-triggered amphiphilic alginate-based fluorescent aggregates. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 119, 106843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timm, K.; Myant, C.; Spikes, H.A.; Grunze, M. Particulate lubricants in cosmetic applications. Tribol. Int. 2011, 44, 1695–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Chen, H.; Bian, Z.; Sun, T.; Ding, H.; Yang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Lian, Q.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H. Enhancing strength and ductility of AlSi10Mg fabricated by selective laser melting by TiB2 nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 109, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Takano, K.; Hanochi, H.; Asaumi, Y.; Yusa, S.-i.; Nakamura, Y.; Fujii, S. pH-Responsive Aqueous Bubbles Stabilized With Polymer Particles Carrying Poly(4-vinylpyridine) Colloidal Stabilizer. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Nicolai, T. The effect of the contact angle on particle stabilization and bridging in water-in-water emulsions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 638, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanamaia, R.; Horna, G.; McClements, D.J. Influence of oil polarity on droplet growth in oil-in-water emulsions stabilized by a weakly adsorbing biopolymer or a nonionic surfactant. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2002, 247, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, W.; Ye, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, W. Pickering emulsions stabilized by hydrophobically modified hemp powders: The effect of formula compositions on emulsifying capability and stability. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2019, 41, 2143–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szumała, P.; Luty, N. Effect of different crystalline structures on W/O and O/W/O wax emulsion stability. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2016, 499, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witecka, A.; Yamamoto, A.; Dybiec, H.; Swieszkowski, W. Surface characterization and cytocompatibility evaluation of silanized magnesium alloy AZ91 for biomedical applications. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2012, 13, 064214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.J.; Armes, S.P. Pickering Emulsifiers Based on Block Copolymer Nanoparticles Prepared by Polymerization-Induced Self-Assembly. Langmuir 2020, 36, 15463–15484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Meng, X.; Wu, L.; Gao, C.; Lv, K.; Sun, B. Improvement of Emulsion Stability and Plugging Performance of Nanopores Using Modified Polystyrene Nanoparticles in Invert Emulsion Drilling Fluids. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 890478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frelichowska, J.; Bolzinger, M.-A.; Chevalier, Y. Pickering emulsions with bare silica. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2009, 343, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Shen, X.; Chang, S.; Ou, W.; Zhang, W. Effect of oil properties on the formation and stability of Pickering emulsions stabilized by ultrafine pearl powder. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 338, 116645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, E.; Zamani, N.; Soleimani, E.; Zamani, N. Surface modification of alumina nanoparticles: A dispersion study in organic media. Acta Chim. Slov. 2017, 64, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manga, M.S.; Hunter, T.N.; Cayre, O.J.; York, D.W.; Reichert, M.D.; Anna, S.L.; Walker, L.M.; Williams, R.A.; Biggs, S.R. Measurements of Submicron Particle Adsorption and Particle Film Elasticity at Oil–Water Interfaces. Langmuir 2016, 32, 4125–4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Tian, X.; Jin, Y.; Chen, J.; Walters, K.B.; Ding, S. A pH responsive Pickering emulsion stabilized by fibrous palygorskite particles. Appl. Clay Sci. 2014, 102, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wen, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, R.; Ren, J.; et al. Pickering Emulsion Stabilized by Tea Seed Cake Protein Nanoparticles as Lutein Carrier. Foods 2022, 11, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Gao, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, K.; Du, F. Improving the emulsion stability by regulation of dilational rheology properties. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2019, 583, 123906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Qu, L.; Wang, F.; Mei, Z.; Wu, X.; Wang, B.; Liu, H.; He, L. A study on the anti-senescent effects of flavones derived from Prinsepia utilis Royle seed residue. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 328, 118021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Oil | Polarity Index (mN/m) | Emulsion Type |

|---|---|---|

| SQU | 46.20 (non-polar) | O/W |

| MO | 43.79 (non-polar) | O/W |

| OLO | 24.80 (neutral) | O/W |

| GTCC | 21.30 (neutral) | O/W |

| PSE | 4.60 (polar) | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ye, C.; Zhou, K.; Ye, Z.; Shang, Y.; Wang, F. Micronized Prinsepia utilis Royle Seed Powder as a Natural, Antioxidant-Enriched Pickering Stabilizer for Green Cosmetic Emulsions. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12060281

Ye C, Zhou K, Ye Z, Shang Y, Wang F. Micronized Prinsepia utilis Royle Seed Powder as a Natural, Antioxidant-Enriched Pickering Stabilizer for Green Cosmetic Emulsions. Cosmetics. 2025; 12(6):281. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12060281

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Chuanjun, Kangfu Zhou, Zhicheng Ye, Yazhuo Shang, and Feifei Wang. 2025. "Micronized Prinsepia utilis Royle Seed Powder as a Natural, Antioxidant-Enriched Pickering Stabilizer for Green Cosmetic Emulsions" Cosmetics 12, no. 6: 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12060281

APA StyleYe, C., Zhou, K., Ye, Z., Shang, Y., & Wang, F. (2025). Micronized Prinsepia utilis Royle Seed Powder as a Natural, Antioxidant-Enriched Pickering Stabilizer for Green Cosmetic Emulsions. Cosmetics, 12(6), 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12060281