Development of a Multifunctional Phytocosmetic Nanoemulsion Containing Achillea millefolium: A Sustainable Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Crude Extract Preparation

2.3. Analysis of the Extract by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry (HPLC-ESI/MS)

2.4. Determination of Total Phenolic Content

2.5. Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity

2.6. Tyrosinase Inhibition Assay

2.7. Cell Viability Assay

2.8. Development of Nanoemulsions

2.9. Characterization of Nanoemulsions

2.9.1. Macroscopic Evaluation

2.9.2. pH Determination

2.9.3. Evaluation of Droplet Means Diameter and Polydispersity Index

2.9.4. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.9.5. Viscosity

2.9.6. Spreadability

2.9.7. Occlusion Factor

2.9.8. In Vitro Analysis of SPF, UVA/UVB Ratio, and Critical Wavelength

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of the Crude Extract of A. millefolium

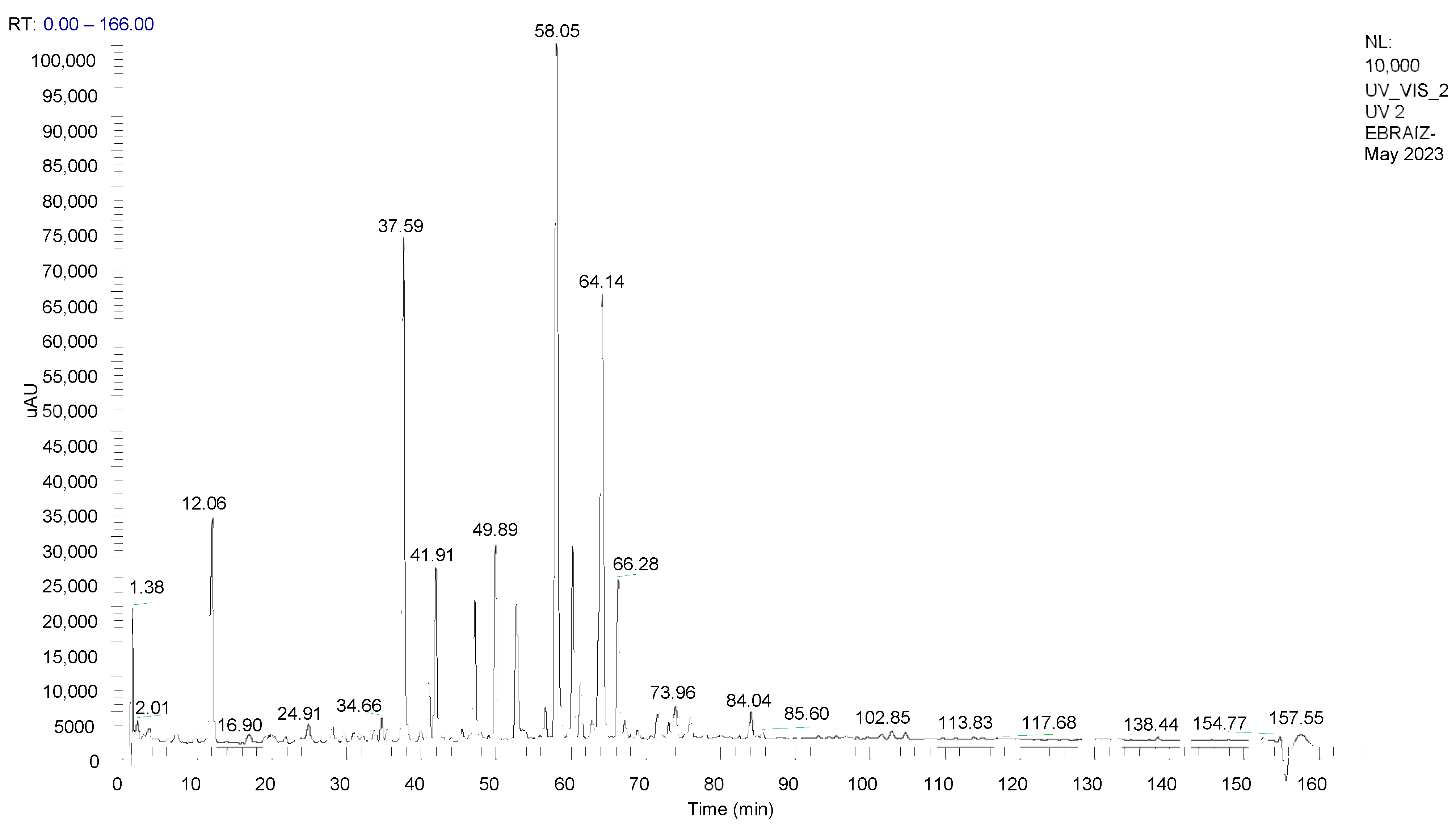

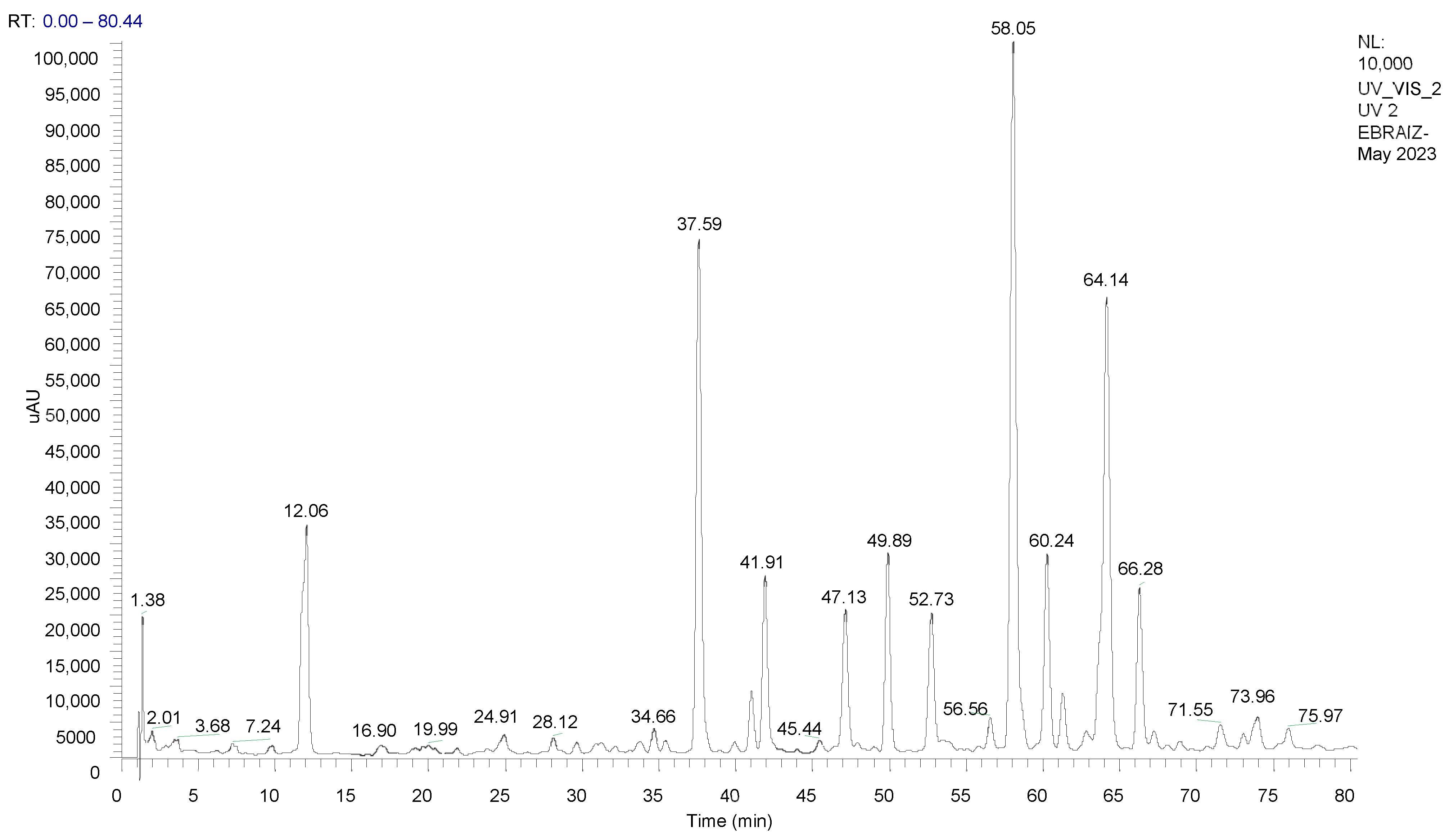

3.1.1. HPLC-ESI/MS Analysis of the Extract

3.1.2. Evaluation of Total Phenolic Content

3.1.3. Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity

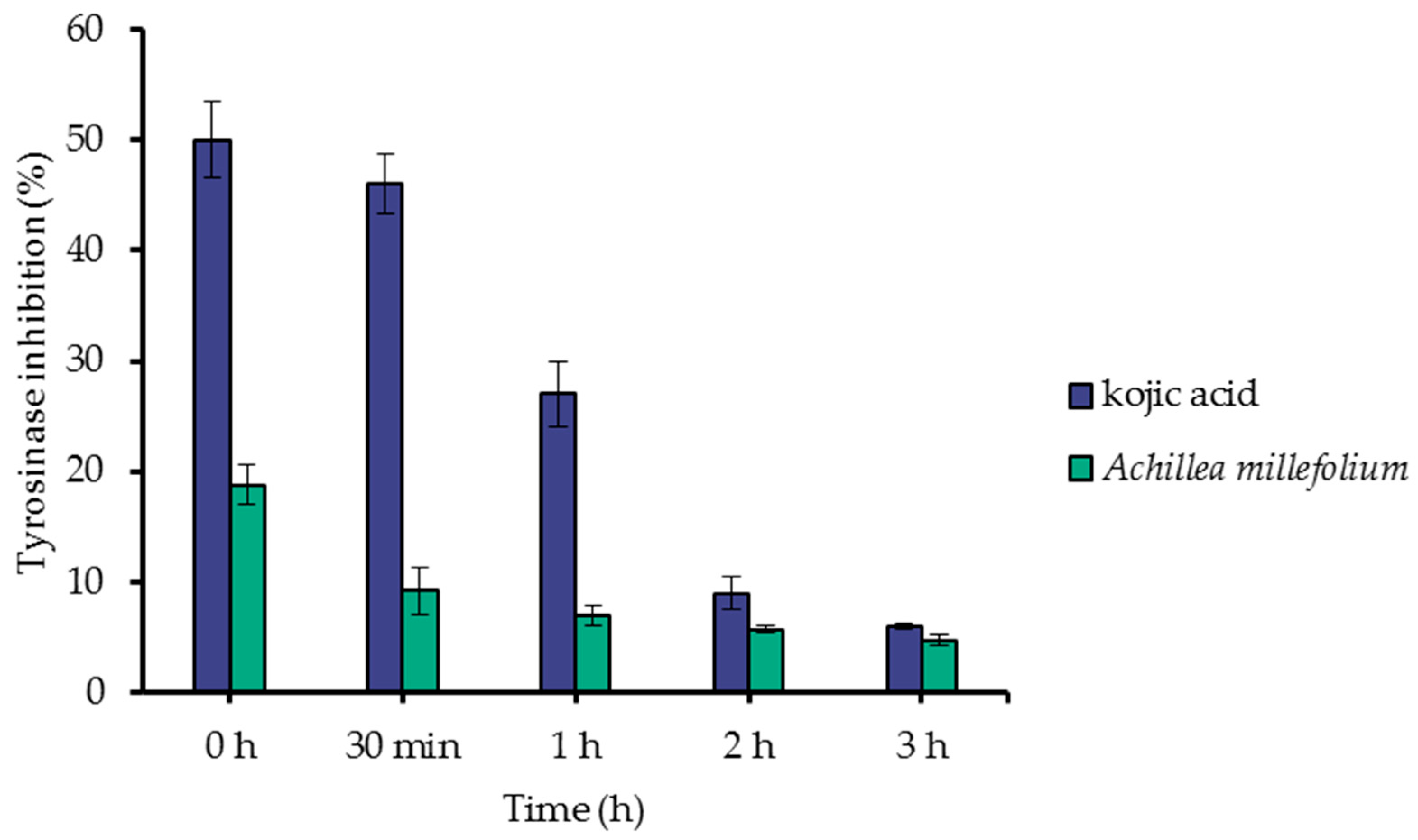

3.1.4. Tyrosinase Inhibition Assay

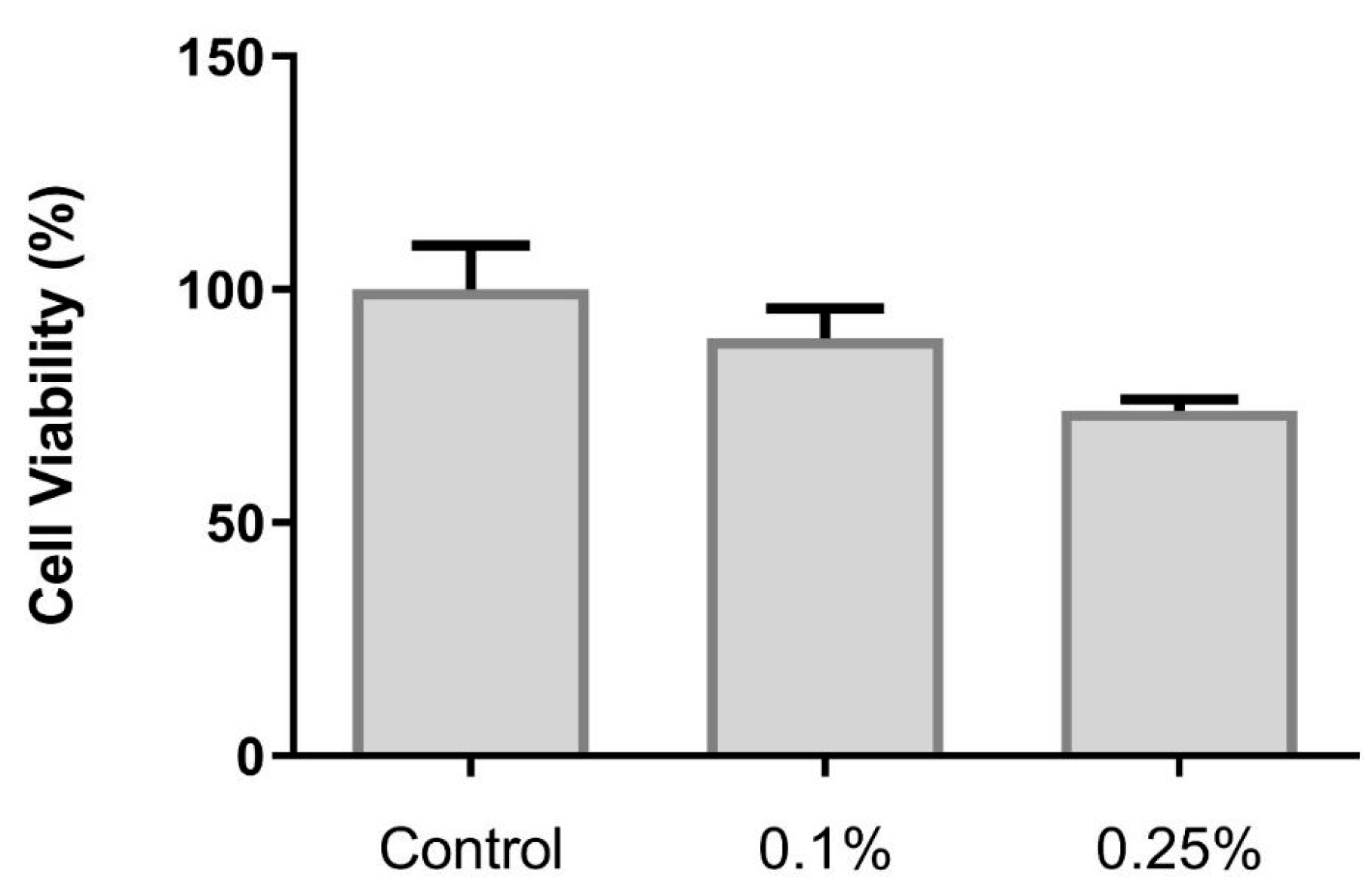

3.1.5. Cell Viability Assay

3.2. Characterization of Nanoemulsions

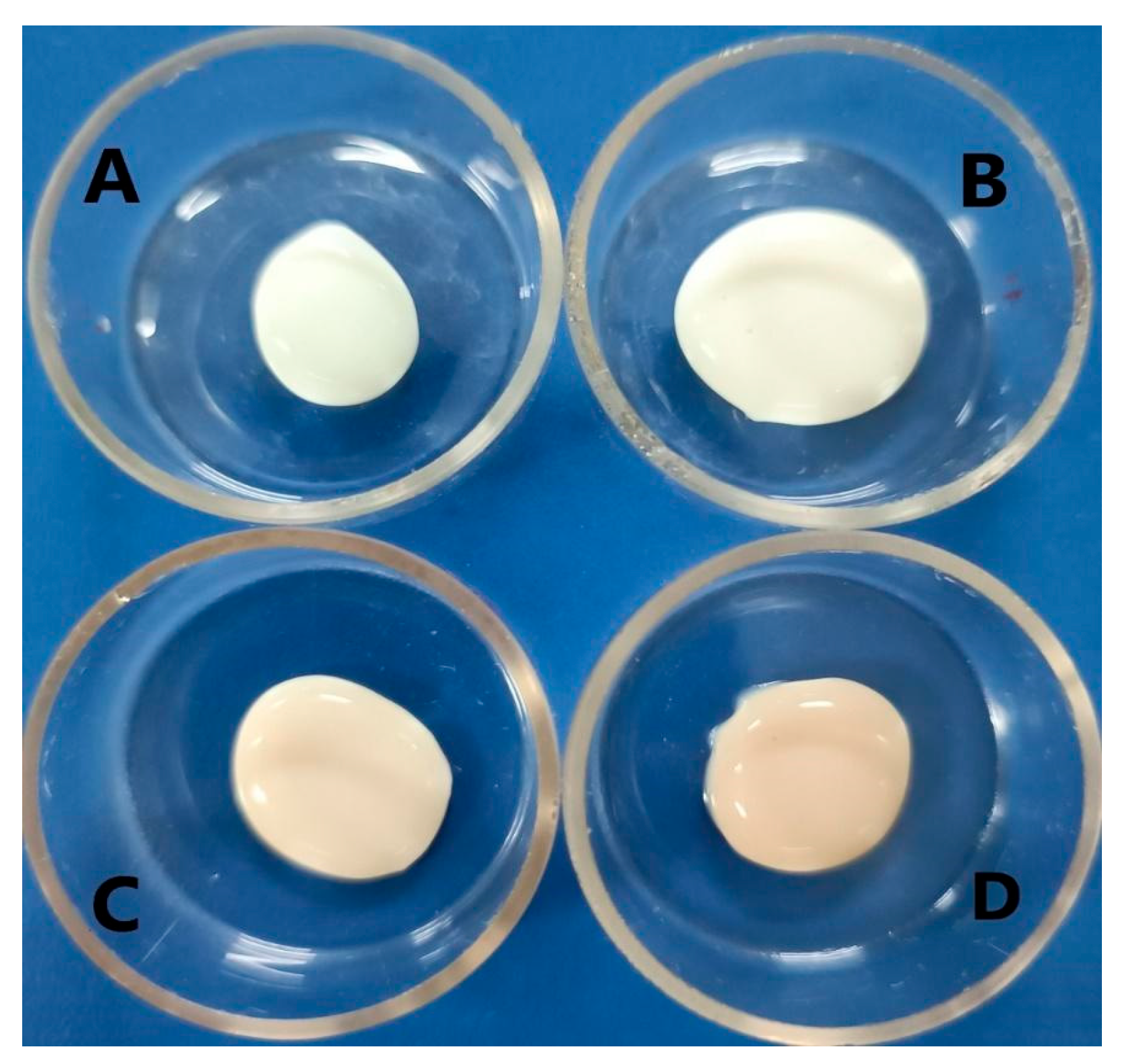

3.2.1. Macroscopic Evaluation

3.2.2. Evaluation of Droplet Means Diameter and Polydispersity Index

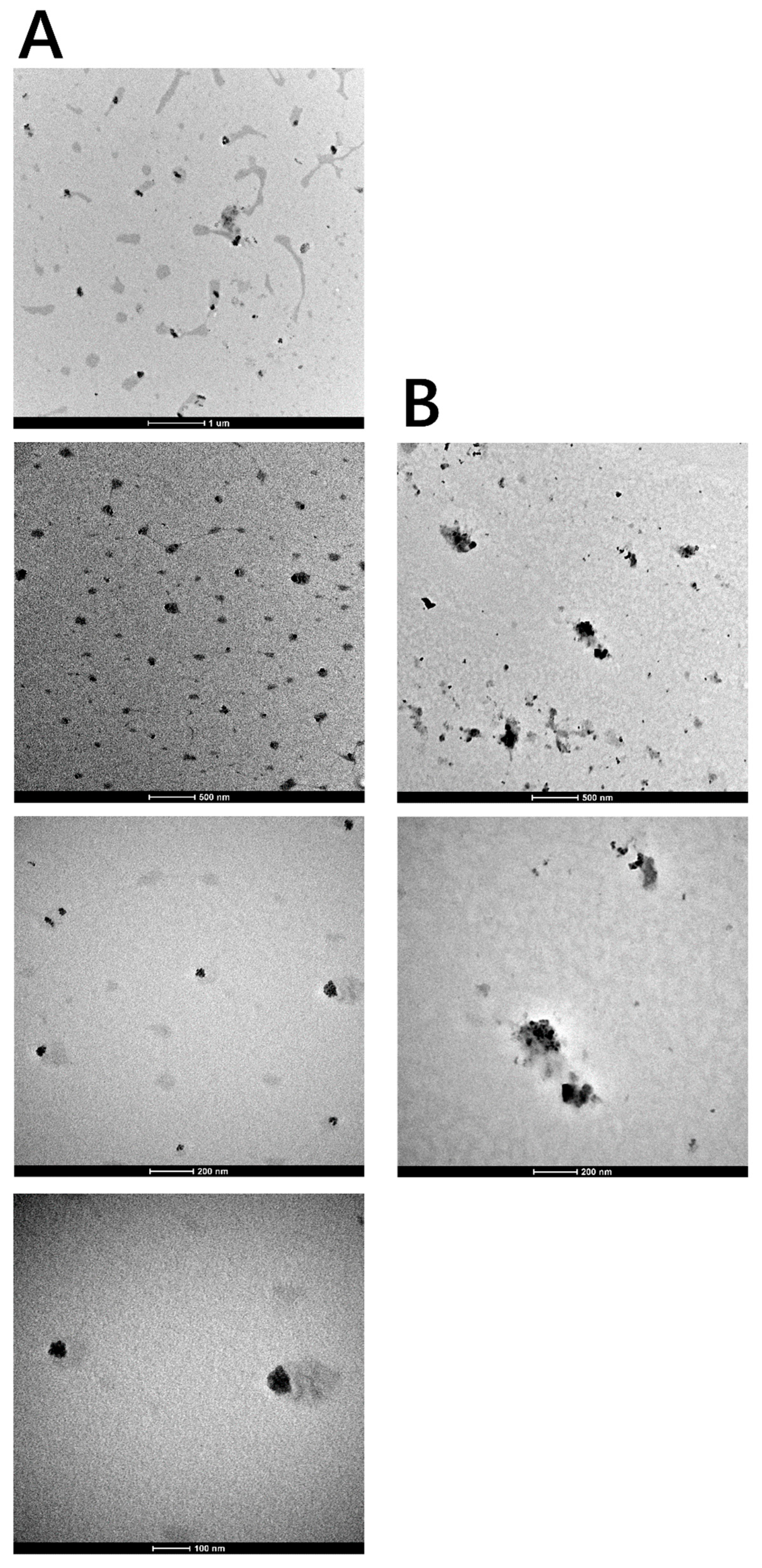

3.2.3. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

3.2.4. pH Determination

3.2.5. Viscosity

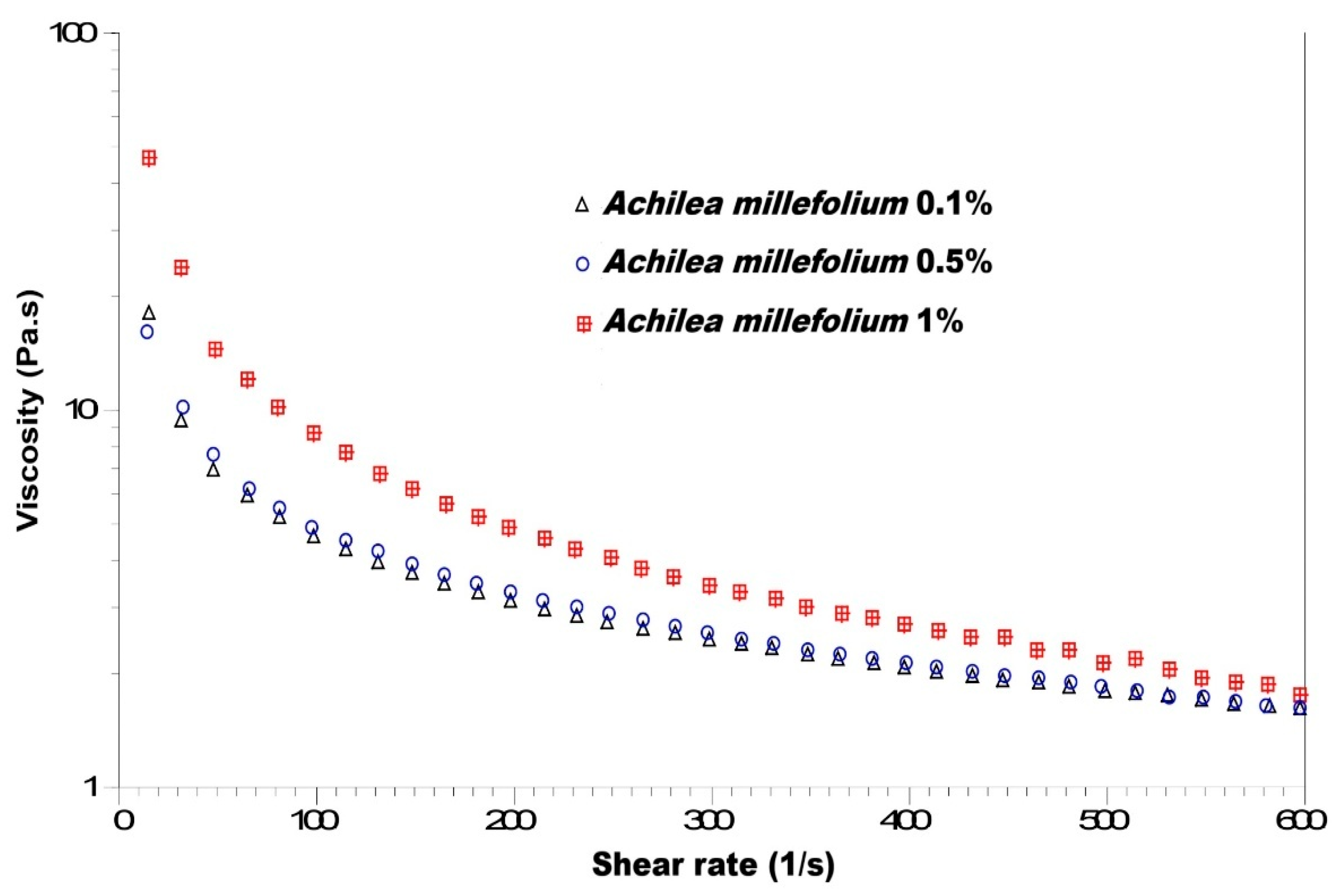

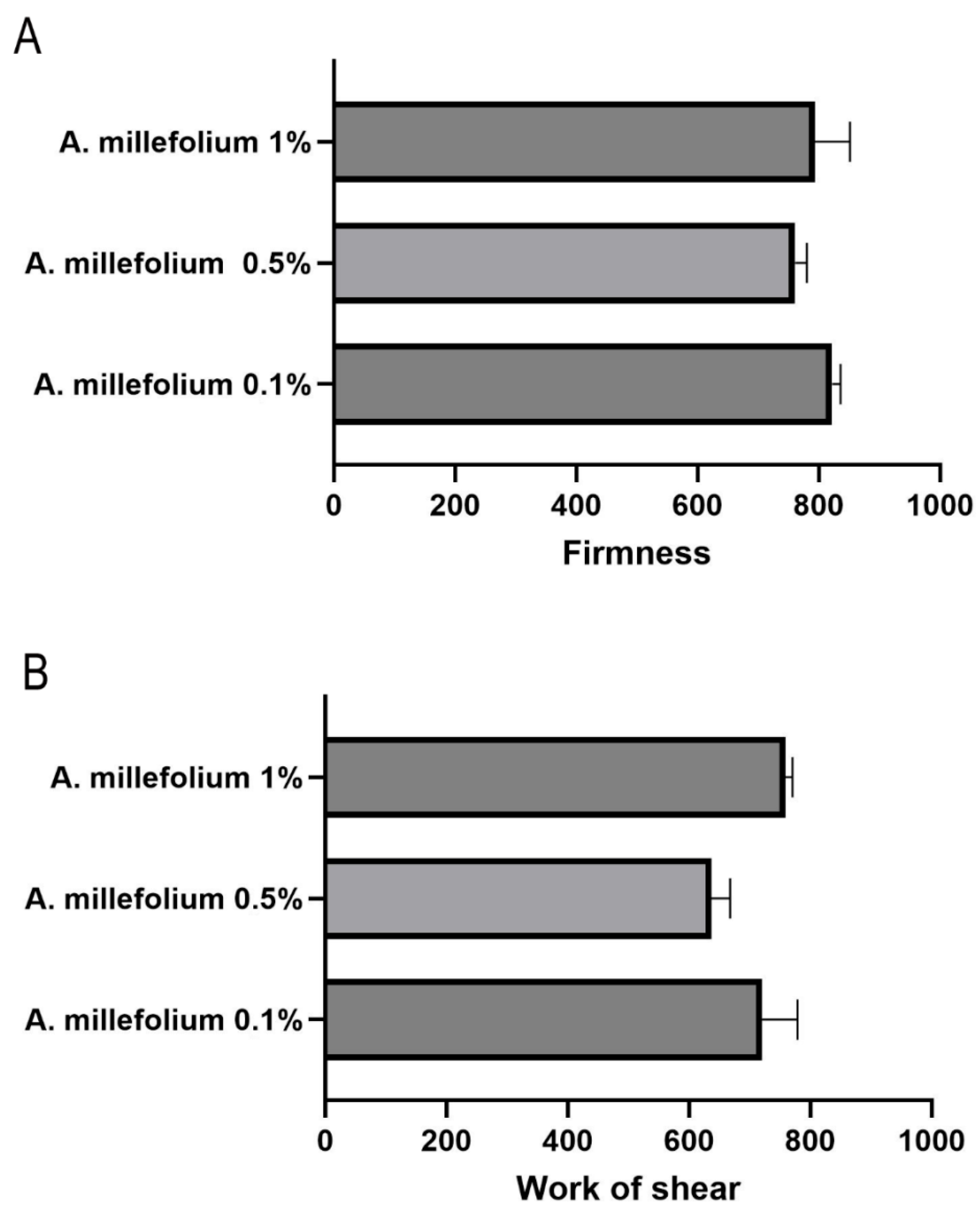

3.2.6. Spreadability

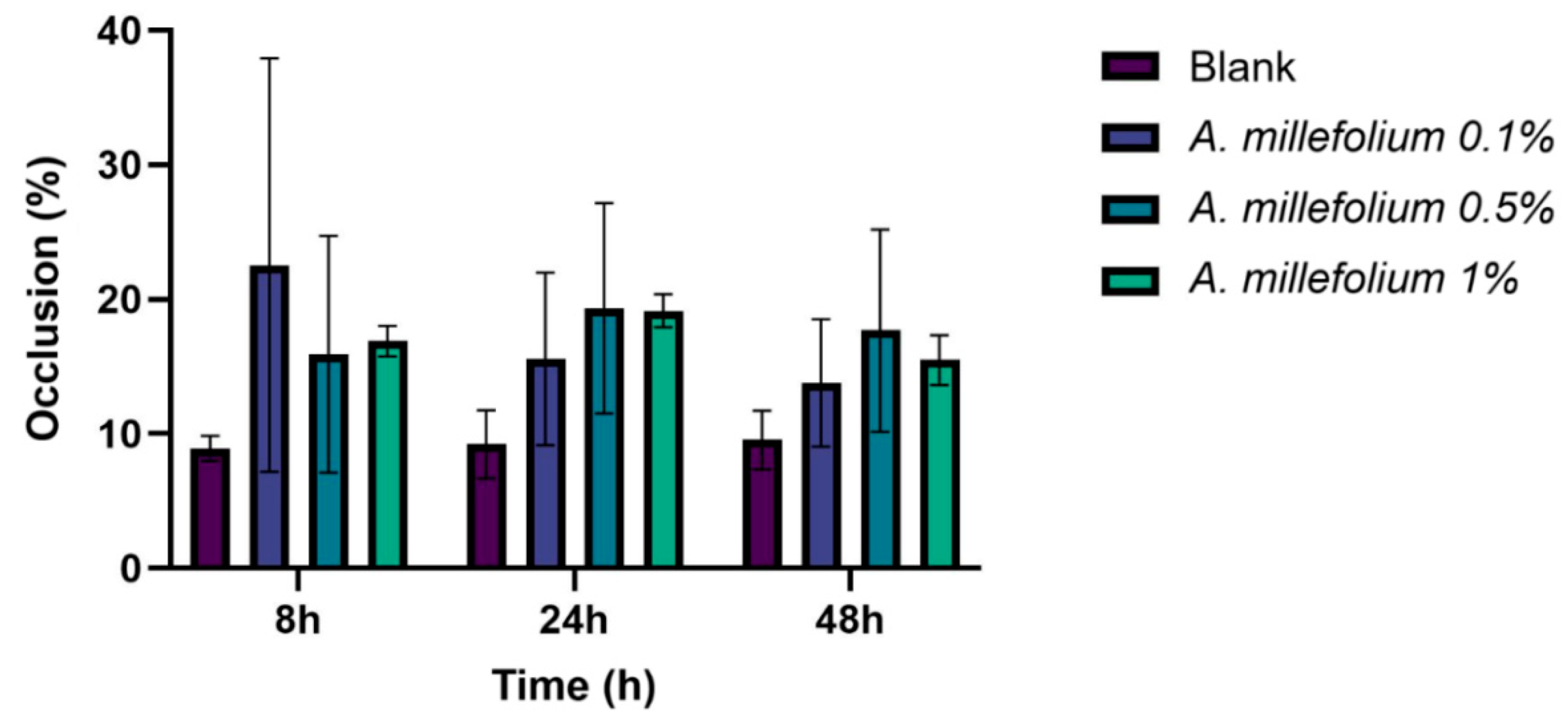

3.2.7. Occlusion Factor

3.2.8. In Vitro SPF Analysis, UVA/UVB Ratio, and Critical Wavelength

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Programmes for Age-Friendly Cities and Communities: A Guide. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240068698 (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Bonifant, H.; Holloway, S. A review of the effects of ageing on skin integrity and wound healing. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2019, 24, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesa-Arango, A.C.; Flórez-Muñoz, S.V.; Sanclemente, G. Mechanisms of skin aging. Iatreia 2017, 30, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.Z.M.D. Desenvolvimento de Formulações Cosméticas com Ácido Hialurónico. Master’s Thesis, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal, December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Veloso, L.M.; Santana, B.; Colombo, C.R.; Vargas, E.J.C.; Vieira, L.R.; Valadão, M.F.; Valadão, M.F.; Bizzi, L.A. O uso de bioestimuladores injetáveis de colágeno para controle de sinais de envelhecimento facial. Recima21 2023, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, I.N.; Silva, M.J.A.; Sampaio, L.H.F. Avaliação dos efeitos de um emissor de ondas ultrassônicas no tratamento do envelhecimento facial. Braz. J. Health Rev. 2022, 5, 2127–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Zhao, K.; Guo, X.; Tu, J.; Zhang, D.; Sun, W.; Kong, X. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound inhibits adipogenic differentiation via HDAC1 signalling in rat visceral preadipocytes. Adipocyte 2019, 8, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannach, A.B.; Rangel, K.C.; Abreu, C.S.; Malés, F.C.; Morais, D.C.; Oliveira, G.P.; Zung, S.P. Avaliação dos efeitos antienvelhecimento por métodos in vitro e ex vivo de produto cosmético multifuncional. Braz. J. Health Rev. 2022, 5, 8136–8146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagner, S.; Costa, A. Bases biomoleculares do fotoenvelhecimento. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2009, 84, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, J.E.S.; Mickos, T.B.; Silva, K.F.; Sartor, C.F.P.; Felipe, D.F. Estudo da atividade fotoprotetora de diferentes extratos vegetais e desenvolvimento de formulação de filtro solar. In Proceedings of the VIII Encontro Internacional de Produção Científica Cesumar, Maringá, Brazil, 22–25 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A.C.P.; Paiva, J.P.; Diniz, R.R.; Dos Anjos, V.M.; Silva, A.B.S.M.; Pinto, A.V.; Dos Santos, E.P.; Leitão, A.C.; Cabral, L.M.; Rodrigues, C.R.; et al. Photoprotection assessment of olive (Olea europaea L.) leaves extract standardized to oleuropein: In vitro and in silico approach for improved sunscreens. J. Photochem. Photobiol. 2019, 193, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, K.C.; Alves, B.L.; dos Santos, R.S.; de Araújo, L.A.; Bergamasco, R.; Bruschi, M.L.; Ueda-Nakamura, T.; Lautenschlager, S.d.O.S.; Nakamura, C.V. Exploring Skin Biometrics, Sensory Profiles, and Rheology of Two Photoprotective Formulations with Natural Extracts: A Commercial Product Versus a Vegan Test Formulation. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flor, J.; Mazin, M.R.; Ferreira, L.A. Cosméticos Naturais, Orgânicos e Veganos. Cosmet. Toilet. 2019, 31, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A.L.F.; Silva, W.G.; Silva, J.M.L. A influência dos cosméticos naturais e orgânicos na saúde da pele: Benefícios e desafios. Ciência Atual 2024, 21, 737–747. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, W.A.S.; Antunes, A.S.; Penido, R.G.; Correa, H.S.G.; Nascimento, A.M.; Andrade, A.L.; Santos, V.R.; Cazati, T.; Amparo, T.R.; Souza, G.H.B.; et al. Photoprotective activity and increase of SPF in sunscreen formulation using lyophilized red propolis extracts from Alagoas. Rev. Bras. Farm. 2019, 29, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, P.E.; Gomes, A.C.C.; Gomes, A.K.C.; Nigro, F.; Kuster, R.M.; Freitas, Z.M.F.; Coutinho, C.S.C.; Monteiro, M.S.S.B.; Santos, E.P.; Simas, N.K. Development and Characterization of Phytocosmetic Formulations with Saccharum officinarum. Rev. Bras. Farm. 2020, 30, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Torres, J.; Garcia Chávez, A. Alcamidas en plantas: Distribución e importancia. Av. Perspect. 2001, 20, 377–387. [Google Scholar]

- Resolução RDC Nº 10, de 9 de Março de 2010. Available online: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/anvisa/2010/res0010_09_03_2010.html (accessed on 7 February 2021).

- Kintzios, S.; Papageorgiou, K.; Yiakoumettis, I.; Baričevič, D.; Kušar, A. Evaluation of the antioxidants activities of four Slovene medicinal plant species by traditional and novel biosensory assays. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2010, 53, 773–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumbeckaite, S.; Benetis, R.; Bumblauskiene, L.; Burdulis, D.; Janulis, V.; Toleikis, A.; Viškelis, P.; Jakštas, V. Achillea millefolium L. s.l. herb extract: Antioxidant activity and effect on the rat heart mitochondrial functions. Food Chem. 2011, 127, 1540–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitalini, S.; Beretta, G.; Iriti, M.; Orsenigo, S.; Basilico, N.; Dall’Acqua, S.; Iorizzi, M.; Fico, G. Phenolic compounds from Achillea millefolium L. and their bioactivity. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2011, 58, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalili, A.; Milani, S.E.; Kamali, N.; Mohammadi, S.; Pakbaz, M.; Jamalnia, S.; Sadeghi, M. Beneficial effects of Achillea millefolium on skin injuries; a literature review. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2022, 34, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pain, S.; Altobelli, C.; Boher, A.; Cittadini, L.; Favre-Mercuret, M.; Gaillard, C.; Sohm, B.; Vogelgesang, B.; André-Frei, V. Surface rejuvenating effect of Achillea millefolium extract. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2011, 33, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocevar, N.; Glavac, I.; Injac, R.; Kreft, S. Comparison of capillary electrophoresis and high performance liquid chromatography for determination of flavonoids in Achillea millefolium. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2008, 46, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, A.J.; Scheiber, S.A.; Thomas, C.; Pardini, R.S. Inhibition of glutathione reductase by flavonoids. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1992, 44, 1603–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirley, B.W. Flavonoid biosynthesis: ‘new’ functions for an ‘old’ pathway. Trends Plant Sci. 1996, 1, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrali, M.; Signorini, C.; Caciotti, B.; Sugherini, L.; Ciccoli, L.; Giachetti, D.; Comporti, M. Protection against oxidative damage of erythrocyte membranes by the flavonoid quercetin and its relation to iron chelating activity. FEBS Lett. 1997, 416, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cos, P.; Ying, L.; Calomme, M.; Hu, J.P.; Cimanga, K.; Van Poel, B.; Pieters, L.; Vlietinck, A.J.; Vanden Berghe, D. Structure-activity relationship and classification of flavonoids as inhibitors of xanthine oxidase and superoxide scavengers. J. Nat. Prod. 1998, 61, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, R.; Sasamoto, W.; Matsumoto, A.; Itakura, H.; Igarashi, O.; Kondo, K. Antioxidant ability of various flavonoids against DPPH radicals and LDL oxidation. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2001, 47, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saewan, N.; Jimtaisong, A. Photoprotection of natural flavonoids. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 3, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonen, J.; Bronselaer, A.; Nielandt, J.; Veryser, L.; De Tré, G.; De Spiegeleer, B. Alkamid database: Chemistry, occurrence and functionality of plant N-alkylamides. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 142, 563–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artaria, C.; Maramaldi, G.; Bonfigli, A.; Rigano, L.; Appendino, G. Lifting properties of the alkamide fraction from the fruit husks of Zanthoxylum bungeanum. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2011, 33, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veryser, L. Analytical, Pharmacokinetic and Regulatory Characterisation of Selected Plant n-alkylamides. Ph.D. Thesis, Universiteit Gent, Ghent, Belgium, 4 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Demarne, M.F.; Passaro, V.G. Use of an Acmella oleracea Extract for the Botulinum Toxin-Like Effect Thereof in an Ant-Wrinkle Cosmetic Composition. US 7,531,193 B2, 12 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, A.F.; Carvalho, M.G.; Smith, R.E.; Sabaa-Srur, A.U.O. Spilanthol: Occurrence, extraction, chemistry and biological activities. Rev. Bras. Farm. 2016, 26, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Spiegeleer, B.; Boonen, J.; Malysheva, S.V.; Mavungu, J.D.; De Saeger, S.; Roche, N.; Blondeel, P.; Taevernier, L.; Veryser, L. Skin penetration enhancing properties of the plant N-alkylamide spilanthol. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 148, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greger, H.; Hofer, O. Polyenoic acid piperideides and other alkamides from Achillea millefolium. Phytochemistry 1989, 28, 2363–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veryser, L.; Taevernier, L.; Wynendaele, E.; Verheust, Y.; Dumoulin, A.; De Spiegeleer, B. N-alkylamide profiling of Achillea ptarmica and Achillea millefolium extracts by liquid and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Anal. 2017, 7, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irie, M.F.; Pacheco, M.M.; Gomes, A.K.C.; Simas, N.K.; Gomes, A.C.C. Raízes de Achillea millefolium: Estudo fitoquímico e avaliação do potencial antioxidante. In Proceedings of the IX Encontro da Saúde do IFRJ/Campus Realengo, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 11 February 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekinić, I.G.; Skroza, D.; Ljubenkov, I.; Krstulović, L.; Možina, S.S.; Katalinić, V. Phenolic Acids Profile, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activity of Chamomile, Common Yarrow and Immortelle (Asteraceae). Nat. Prod. Commun. 2014, 9, 1745–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. Lebensm-Wiss. Techonol 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, S.; Nerya, O.; Musa, R.; Shmuel, M.; Tamir, S.; Vaya, J. Chalcones as potent tyrosinase inhibitors: The importance of a 2, 4-substituted resorcinol moiety. Bioorg Med. Chem. 2005, 13, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrini, D.J.; Suffredini, I.B.; Varella, A.D.; Younes, R.N.; Ohara, M.T. Extracts from Amazonian plants have inhibitory activity against tyrosinase: An in vitro evaluation. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 45, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, T.Z.S.; Santos-Oliveira, R.; Siqueira, L.B.O.; Cardoso, V.D.S.; de Freitas, Z.M.F.; Barros, R.C.D.S.A.; Villa, A.L.V.; Monteiro, M.S.S.B.; Dos Santos, E.P.; Ricci-Junior, E. Development and characterization of a nanoemulsion containing propranolol for topical delivery. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 2827–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, J.; de Freitas, Z.M.F.; Monteiro, M.S.S.B.; Vermelho, A.B.; Ricci Junior, E.; dos Santos, E.P. Development and characterization of photoprotective formulations containing keratin particles. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 55, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgado, C.S.; Simas, N.K.; Gomes, A.C.C.; Luz, D.A.; Kuster, R.M.; Monteiro, M.S.S.B.; Ricci-Júnior, E. Development of Phytocosmetic Photoprotective Nanoemulsion Containing Winery Industry Waste. Braz. J Pharmacog. 2025, 35, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, L.B.O.; Santos, A.P.M.; Silva, M.R.M.; Pinto, S.R.; Santos-Oliveira, R.; Ricci Júnior, E. Pharmaceutical nanotechnology applied to phthalocyanines for the promotion of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy: A literature review. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2022, 39, 102896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, M.S.S.B.; dos Santos, T.M.; Oliveira, C.A.; Freitas, Z.M.F.; Santos, E.P. Desenvolvimento e avaliação de hidrogeis de carboximetilcelulose para o tratamento de feridas. Infarma Ciências Farm. 2020, 32, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojerová, J.; Medovcíková, A.; Mikula, M. Photoprotective efficacy and photostability of fifteen sunscreen products having the same label SPF subjected to natural sunlight. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 15, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasco, M.V.R.; Balogh, T.S.; Pedriali, C.A.; Sarruf, F.D.; Pinto, C.A.S.O.; Kaneko, T.M.; Baby, A.R. Novas metodologias para avaliação da eficácia fotoprotetora (in vitro)—Revisão. Rev. Ciênc Farm. Básica 2011, 32, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ruvolo-Junior, E.; Kollias, N.; Cole, C. New noninvasive approach assessing in vivo sun protection factor (SPF) using diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) and in vitro transmission. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2014, 30, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Rahaman, M.S.; Islam, M.R.; Rahman, F.; Mithi, F.M.; Alqahtani, T.; Almikhlafi, M.A.; Alghamdi, S.Q.; Alruwaili, A.S.; Hossain, M.S.; et al. Role of Phenolic Compounds in Human Disease: Current Knowledge and Future Prospects. Molecules 2021, 27, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Molina, M.; Albaladejo-Marico, L.; Yepes-Molina, L.; Nicolas-Espinosa, J.; Navarro-León, E.; Garcia-Ibañez, P.; Carvajal, M. Exploring Phenolic Compounds in Crop By-Products for Cosmetic Efficacy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayat, S.; Miana, G.A.; Kanwal, M.; Ahsan, Z.; Tariq, M.J. Determination of Total Flavonoid Content and Phenolic Content, Antioxidant Assay, and Antiepileptic Activity of Achillea millefolium Extract. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2025, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovanović, K.; Gavarić, N.; Švarc-Gajić, J.; Brezo-Borjan, T.; Zlatković, B.; Lončar, B.; Aćimović, M. Subcritical Water Extraction as an Effective Technique for the Isolation of Phenolic Compounds of Achillea Species. Processes 2023, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanini, M.Z.; Custódio, D.L.; Ivan, A.L.M.; Martins, S.M.; Paranzini, M.J.R.; Martinez, R.M.; Verri, W.A., Jr.; Vicentini, F.T.M.C.; Arakawa, N.S.; Faria, T.J.; et al. Topical Formulations Containing Pimenta pseudocaryophyllus Extract: In Vitro Antioxidant Activity and In Vivo Efficacy Against UV-B-Induced Oxidative Stress. AAPS PharmSciTech 2014, 15, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Petruk, G.; Del Giudice, R.; Rigano, M.M.; Monti, D.M. Antioxidants from Plants Protect against Skin Photoaging. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2018, 2018, 1454936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; Sung, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, Y.; Jeong, H.S.; Lee, J. Protective activity of caffeic acid and sinapic acid against UVB-induced photoaging in human fibroblasts. J. Food Biochem. 2019, 43, 12701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lee, W.; Jayawardena, T.U.; Cha, S.H.; Jeon, Y.J. Dieckol, an algae-derived phenolic compound, suppresses airborne particulate matter-induced skin aging by inhibiting the expressions of pro-inflammatory cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases through regulating NF-κB, AP-1, and MAPKs signaling pathways. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 146, 111823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merecz-Sadowska, A.; Sitarek, P.; Kucharska, E.; Kowalczyk, T.; Zajdel, K.; Cegliński, T.; Zajdel, R. Antioxidant Properties of Plant-Derived Phenolic Compounds and Their Effect on Skin Fibroblast Cells. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mapoung, S.; Semmarath, W.; Arjsri, P.; Umsumarng, S.; Srisawad, K.; Thippraphan, P.; Yodkeeree, S.; Limtrakul, P. Determination Of Phenolic Content, Antioxidant Activity, And Tyrosinase Inhibitory Effects of Functional Cosmetic Creams Available on the Thailand Market. Plants 2021, 10, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, M.L.; Falqué, E.; Domínguez, H. Relevance of Natural Phenolics from Grape and Derivative Products in the Formulation of Cosmetics. Cosmetics 2015, 2, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolwitsch, C.B.; Pires, F.B.; Loose, R.F.; Dal Prá, V.; Schneider, V.M.; Schmidt, M.E.P.; Monego, D.L.; Carvalho, C.A.; Fernandes, A.A.; Mazutti, M.A.; et al. Atividade Antioxidante (ROO•, O2•- e DPPH) e Compostos Fenólicos Majoritários para folha, flor, ramo e inflorescência da Achillea (celastraceae). Ciência Nat. 2016, 38, 1487–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guz, L.; Adaszek, Ł.; Wawrzykowski, J.; Ziętek, J.; Winiarczyk, S. In vitro antioxidant and antibabesial activities of the extracts of Achillea millefolium. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2019, 22, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahiruddin, S.; Parveen, A.; Khan, W.; Parveen, R.; Ahmad, S. TLC-Based Metabolite Profiling and Bioactivity-Based Scientific Validation for Use of Water Extracts in AYUSH Formulations. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat Med. 2021, 2021, 2847440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manayi, A.; Vazirian, M.; Saeidnia, S. Echinacea purpurea: Pharmacology, phytochemistry and analysis methods. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2015, 9, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.Y.; Lim, Y.Y.; Yule, C.M. Evaluation of antioxidant, antibacterial andanti-tyrosinase activities of four macaranga species. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, A.A.; Azlan, A.; Ismail, A.; Hashim, P.; Gani, S.S.A.; Zainudin, B.H.; Abdul-lah, N.A. Phenolic composition, antioxidant, anti-wrinkles and tyrosinaseinhibitory activities of cocoa pod extract. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A.F.; Silva, K.C.B.; de Oliveira, M.C.C.; de Carvalho, M.G.; Sabaa Srur, A.U.O. Effects of Acmella oleracea methanolic extract and fractions on the tyrosinase enzyme. Rev. Bras. Farm. 2016, 26, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-B.; Liu, R.H.; Ho, M.-C.; Wu, T.-Y.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lo, I.-W.; Hou, M.-F.; Yuan, S.-S.; Wu, Y.-C.; Chang, F.-R. Alkylamides of Acmella oleracea. Molecules 2015, 20, 6970–6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaston, T.E.; Mendrick, D.N.; Paine, M.F.; Roe, A.L.; Yeung, C.K. “Natural” is not synonymous with “Safe”: Toxicity of natural products alone and in combination with pharmaceutical agents. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 113, 104642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alnuqaydan, A.M.; Sanderson, B.J. Toxicity and Genotoxicity of Beauty Products on Human Skin Cells In Vitro. J. Clin. Toxicol. 2016, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 10993-5:2009; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices—Part 5: Tests for In Vitro Cytotoxicity. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Becker, L.C.; Bergfeld, W.F.; Belsito, D.V.; Hill, R.A.; Klaassen, C.D.; Liebler, D.C.; Marks, J.G., Jr.; Shank, R.C.; Slaga, T.J.; Snyder, P.W.; et al. Safety Assessment of Achillea millefolium as Used in Cosmetics. Int. J. Toxicol. 2016, 35, 5S–15S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J. Nanoemulsions versus microemulsions: Terminology, differences, and similarities. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 1719–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa Verde, F.R.; von der Weid, I.; Santos, P.R. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Nacional da Propriedade Industrial—INPI, Diretoria de Patentes—DIRPA, Coordenação-Geral de Estudos, Projetos e Disseminação de Informação Tecnológica—CEPIT, Divisão de Estudos e Projetos—DIESP. 2017; Radar Tecnológico—n. 14; 17 f. Available online: https://www.gov.br/inpi/pt-br/assuntos/informacao/copy_of_14RadarTecnologiconanocosmtico29_11_2017.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Carvalho, I.P.S. Desenvolvimento de Nanopartículas Lipídicas Sólidas no Carreamento de Extrato Alcaloídico de Solanum lycocarpum e Avaliação Biológica In Vitro em Células de Câncer de Bexiga. Master’s Thesis, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lambers, H.; Piessens, S.; Bloem, A.; Pronk, H.; Finkel, P. Natural skin surface pH is on average below 5, which is beneficial for its resident flora. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2006, 28, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, I.; Tavares, R.S.N.; Bravo, M.G.L.; Gaspar, L.R. Biologia, histologia e fisiologia da pele. Cosmet. Toilet. Bras. 2020, 32, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lahoud, M.H.; Campos, R. Aspectos teóricos relacionados à reologia farmacêutica. Visão Acadêmica 2010, 11, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, T.V.; Costa, R.A.; Guimarães, A.B.M.; Sousa, I.L.L.; Gonçalves, K.G.; Nascimento, W.M.C. Desenvolvimento de formas farmacêuticas semissólidas contendo o extrato aquoso obtido das cascas do Anacardium occidentale L. e realização do estudo de estabilidade acelerado. Rev. Nurs. 2019, 22, 3150–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotowy, J.; Marcondes, F.B.; Silva, T.F.B.X.; Lubi, N.C. Avaliação da estabilidade de emulsão desenvolvida com extratos de Aloe vera (Aloe vera L.), Calêndula (Calendula officinalis L.), Camomila (Matricaria chamomilla L.) e Centella asiática (Centella asiática L.). Sci. Electron. Arch. 2020, 13, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, A.; Bianchini, R.; Jachowicz, J. Texture analysis of cosmetic/pharmaceutical raw materials and formulations. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2014, 36, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calixto, L.S.; Infante, V.H.P.; Maia Campos, P.M.B.G. Design and Characterization of Topical Formulations: Correlations Between Instrumental and Sensorial Measurements. AAPS PharmSciTech 2018, 19, 1512–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gore, E.; Picard, C.; Savary, G. Spreading behavior of cosmetic emulsions: Impact of the oil phase. Biotribology 2018, 16, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, G.M.D. Desenvolvimento e Eficácia Clínica de Formulações Dermocosméticas para o Controle de Alterações Cutâneas Relacionadas ao Fotoenvelhecimento. Ph.D. Thesis, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- The European Cosmetics Association. Colipa Guidelines—Method for the In Vitro Determination of UVA Protection. Available online: https://downloads.regulations.gov/FDA-1978-N-0018-0698/attachment_70.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Kale, S.; Gaikwad, M.; Bhandare, S. Determination and comparison of in vitro SPF of topical formulation containing Lutein ester from Tagetes erecta L. flowers, Moringa oleifera Lam seed oil and Moringa oleifera Lam seed oil containing Lutein ester. Int. J. Pharm. Biomed. Res. 2011, 2, 1220–1224. [Google Scholar]

- FDA Rules and Regulations—Labeling and Effectiveness Testing; Sunscreen Drug Products for Over-the-Counter Human Use. Federal Register, Vol. 76, No. 117, Friday; 17 June 2011. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2011-06-17/pdf/2011-14766.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

| Components | Nanoemulsions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blank % (w/w) | A % (w/w) | B % (w/w) | C % (w/w) | |

| Achillea millefolium | - | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Diethylamino hydroxybenzoyl hexyl benzoate (DHHB) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Octyl Methoxycinnamate (OMC) | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Polysorbate 80 (Tween™ 80) | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Methylparaben | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Solution of Pluronic® F-127 (12.5%) * | q.s. 10 g | q.s. 10 g | q.s. 10 g | q.s. 10 g |

| Retention Time (min) | UVmax (nm) | [M+H] | Molecular Formula | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19.57 | 260 | 207.02 | C11H12O4 | sinapaldehyde |

| 37.59 | 260 | 230.11 | C15H19NO | Isobutylamide of undeca-2E,4E-dieno-8,10-diynoic acid |

| 41.91 | 264 | 242.15 | C16H19NO | Piperidamide of undeca-2E,4E-dieno-8,10-diynoic acid |

| 47.13 | 262 | 222.14 | C14H23NO | Isobutylamide of deca-2E,4E,8Z-trienoic acid |

| 49.89 | 264 | 288.18 | C18H25NO2 | Tyramide of deca-2E,4E-dienoic acid |

| 52.73 | 266 | 234.19 | C15H23NO | Piperidamide of deca-2E,4E,8Z-trienoic acid |

| 58.05 | 262 | 224.21 | C14H25NO | Isobutylamide of deca-2E,4E-dienoic acid (pellitorine) |

| 60.24 | 266 | 270.18 | C18H23NO | Isobutylamide of tetradeca-2E,4E,12Z-trieno-8,10-diynoic acid |

| 64.14 | 266 | 236.26 | C15H25NO | Piperidamide of deca-2E,4E-dienoic acid |

| 66.28 | 262 | 302.20 | C19H27NO2 | 4-methoxyphenylethylamide of -deca-2E,4E-dienoic acid |

| Formulation | Blank | A. millefolium 0.1% | A. millefolium 0.5% | A. millefolium 1% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Droplet means diameter (nm) | 217 ± 4.65 | 230 ± 6.88 | 222 ± 0.56 | 230 ± 3.35 |

| Polydispersity index (PDI) | 0.265 ± 0.008 | 0.419 ± 0.033 | 0.373 ± 0.015 | 0.383 ± 0.015 |

| Formulation | Blank | A. millefolium 0.1% | A. millefolium 0.5% | A. millefolium 1% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sun Protection Factor (SPF) | 14.4 ± 0.9 a,b | 15.3 ± 2.0 a,b | 22.7 ± 5.2 a | 17.0 ± 1.0 a,b |

| UVA/UVB ratio | 0.638 ± 0.005 c | 0.652 ± 0.010 b,c | 0.648 ± 0.008 b,c | 0.648 ± 0.005 b,c |

| Critical wavelength (λc) | 369.9 ± 0.3 b,d | 371.1 ± 0.5 d,e | 370.6 ± 0.5 d,e | 370.0 ± 0.0 b,e |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Christiani, T.S.; Rangel, L.P.; Soares, A.S.R.; Gomes, A.C.C.; Santos, A.C.d.; Monteiro, M.S.S.B.; Simas, N.K.; Ricci-Junior, E. Development of a Multifunctional Phytocosmetic Nanoemulsion Containing Achillea millefolium: A Sustainable Approach. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12060255

Christiani TS, Rangel LP, Soares ASR, Gomes ACC, Santos ACd, Monteiro MSSB, Simas NK, Ricci-Junior E. Development of a Multifunctional Phytocosmetic Nanoemulsion Containing Achillea millefolium: A Sustainable Approach. Cosmetics. 2025; 12(6):255. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12060255

Chicago/Turabian StyleChristiani, Thais Silva, Luciana Pereira Rangel, Andressa Souto Ramalho Soares, Anne Caroline Candido Gomes, Ariely Costa dos Santos, Mariana Sato S. B. Monteiro, Naomi Kato Simas, and Eduardo Ricci-Junior. 2025. "Development of a Multifunctional Phytocosmetic Nanoemulsion Containing Achillea millefolium: A Sustainable Approach" Cosmetics 12, no. 6: 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12060255

APA StyleChristiani, T. S., Rangel, L. P., Soares, A. S. R., Gomes, A. C. C., Santos, A. C. d., Monteiro, M. S. S. B., Simas, N. K., & Ricci-Junior, E. (2025). Development of a Multifunctional Phytocosmetic Nanoemulsion Containing Achillea millefolium: A Sustainable Approach. Cosmetics, 12(6), 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12060255