A Decade of Autologous Micrografting Technology in Hair Restoration: A Review of Clinical Evidence and the Evolving Landscape of Regenerative Treatments

Abstract

1. Introduction

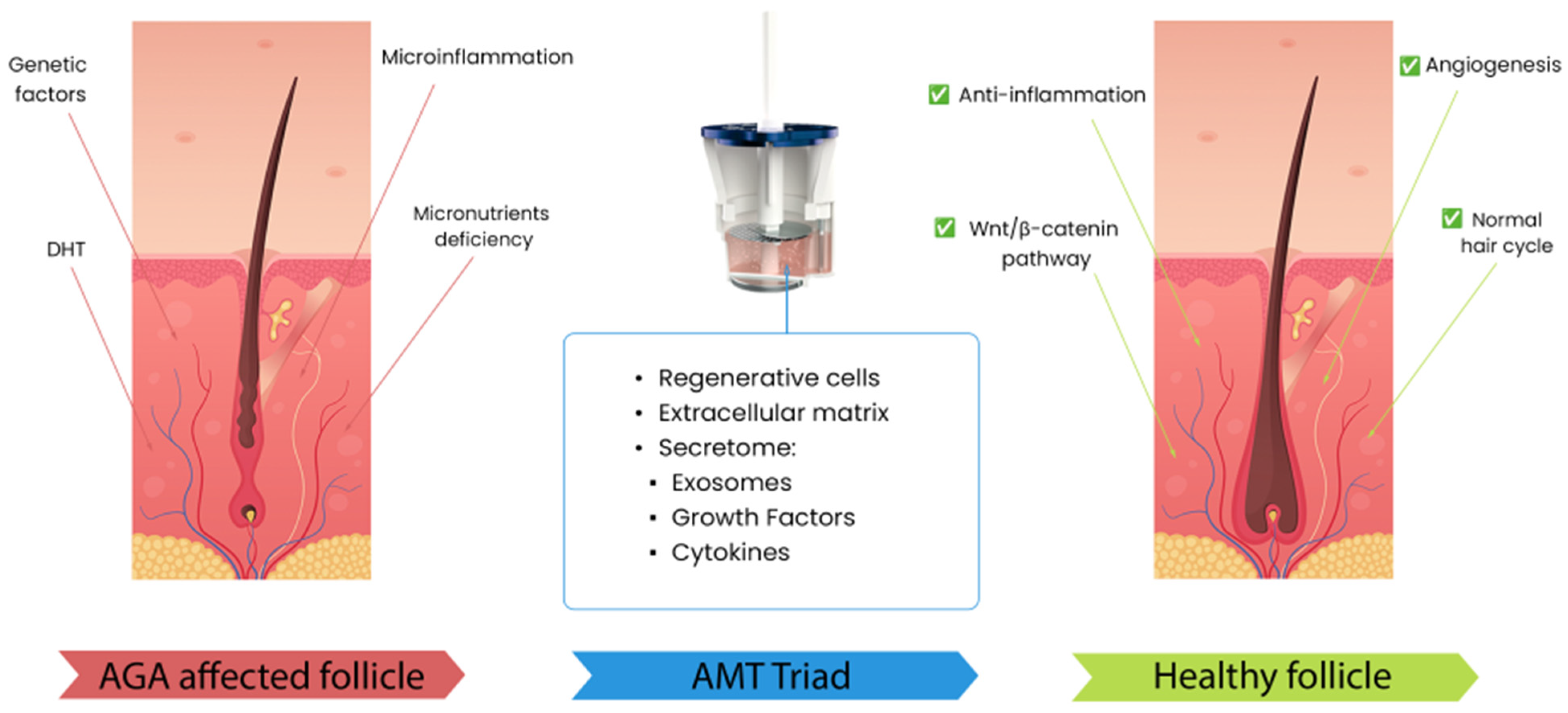

1.1. Pathophysiology of Androgenetic Alopecia

1.2. Differential Diagnosis

2. Approved Treatments

2.1. Minoxidil

2.2. Finasteride

2.3. Dutasteride

3. Regenerative Medicine-Based Treatments

3.1. Platelet-Rich-Plasma (PRP)

3.2. Adipose Tissue-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (AT-MSCs)

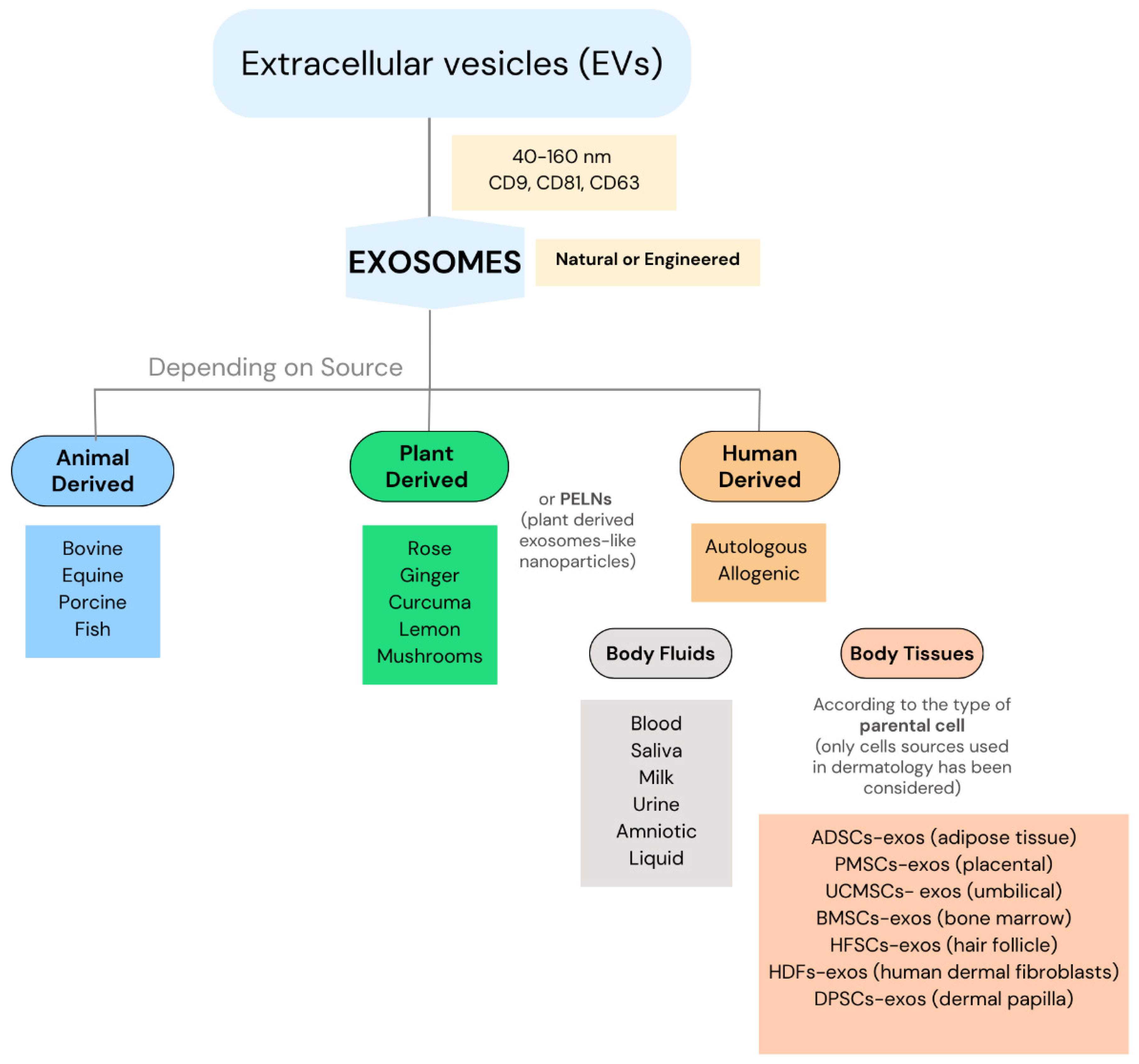

3.3. Exosomes

3.4. Autologous Micrografting Technology

| No. | Study | Year | Brief Description | Sample Size & Study Design | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Trovato, Letizia et al. [66] | 2015 | In vitro preclinical validation of Regenera®, demonstrating the viability and characterization of stem cell populations into 80 µm micrografts | 23 samples, All samples were tested for cell viability and cell characterization throughout flow cytometry analysis (FACS) with antibodies and 7AAD staining | In vitro, the presence of MSCs with expression of CD90 (52%), CD105 (82%) and CD73 (82%). Cell viability in all tissue samples is over 70%, up to 100%. |

| 2 | Álvarez, X., Valenzuela, & M., Tuffet, J. [61] | 2017 | Pilot study evaluating the Regenera® technology for treating AGA through microscopic and histologic analyses for grade III–IV of alopecia Hamilton scale. | 3 patients with male pattern AGA., Results were measured 30 days post-treatment with a micrometer (for hair thickness), hair loss test, and biopsy for identification of cells in the proliferative phase of the cell cycle. | The microscopic results showed an increase in hair thickness and a reduction in hairreduction of hair loss. The histological results showed an increase in epidermis thickness, the number of blood vessels and fibroblastic activity in the hair bulb. |

| 3 | Álvarez, X., Valenzuela, & M., Tuffet, J. [67] | 2017 | The clinical and histological evaluation of the Regenera® method for AGA treatment showed promising results, including increased hair density and follicle regeneration. | 17 patients with AGA (9 with MPHL and 8 with FPHL). Variables assessed after 30 days post-AMT with picture comparison and improving according to Hamilton and Ludwig scale. | An increase in hair thickness in 70% of the patients, 50% of the patients observed a decrease in hair loss. The perception of pain during the treatment was evaluated by most of the patients as level 3 out of 10. |

| 4 | Pinto, H., Gálvez, R., & Casanova, J. [68] | 2018 | The article highlights the importance of dermatoscopy in predicting the outcomes for AGA using the Regenera® protocol. | Review of 100 dermoscopies, the aim of this study was to establish an algorithm based on the 8 most important trichoscopic parameters and guideline to select the patients for AMT. | Scalp dermascopic measurements used to propose an easy score system and algorithm for treating different patient profiles with AGA. |

| 5 | Gentile, Pietro et al. [48] | 2019 | The study evaluated the clinical outcomes of autologous micrografts (with HF-MSCs) vs. Placebo in AGA. A randomized, long-term, evaluator-blinded, half-head group study. | 27 patients, 17 males with Hamilton II–VI and 10 females Ludwig I–II. Clinical Evaluation of hair regrowth using phototrichograms. Histological evaluation of the skin biopsies for viability and quantity of the cells. | Improvement shown in the hair cumulative mean after 58 weeks of 18 hairs more vs. baseline. A total hair density increase of 23.3 hairs/cm2 vs. baseline. Characterization was made of HF-MSCs and mean quantity of 4124.7 cells. With the highest % of CD44+ cells from dermal papilla. |

| 6 | Ruiz, R. G. et al. [62] | 2019 | The study explored the use of progenitor-cell-enriched micrografts from the dermis in the treatment of AGA by clinical and histological evaluations after 4, 6 and 12 months. | 100 patients with AGA were treated with AMT and assessed with TrichoScan Test and histological evaluation of the biopsies was performed. | The TrichoScan Analysis reported a mean increase in total hair density of 30% after 2 months post-treatment and a 10% increase in anagen hairs. |

| 7 | Zari S. [63] | 2021 | A retrospective cohort study assessed the short-term efficacy of autologous cellular micrografts in treating AGA in 140 patients, both males and females. | 140 patients with AGA (male and female). Efficacy was evaluated at 1 and 6 months by trichometry parameters (TrichoScan). | The results showed an increase in mean hair density by 4.5–7.12 hair/cm2. average hair thickness by 0.96–1.88 μm, % thick hair by 1.74–3.26%, and mean number of follicular units by 1.30–2.77, resulting in an increase in cumulative hair thickness by 0.48–0.56 unit. |

| 8 | Hawwam, S. A., Ismail, M., & Elhawary, E. [69] | 2023 | This study evaluated the effectiveness of autologous micrograft injections from scalp tissue in treating COVID-19-associated telogen effluvium. | 20 female patients. Patients were evaluated at the beginning, after 3 and 6 months post-treatment. The evaluation was based on changes in hair density and hair thickness and global photographic assessment. | 11, 6 and 3 patients presented marked clinical improvement, moderate and mild improvement, respectively. Hair density/cm2 mean was 184.1 (T0) vs. 192.9 (T6). Hair thickness (mm) 0.06 (T0) vs. 0.08 (T6). |

| 9 | Krefft-Trzciniecka K. et al. [60] | 2024 | The clinical assessment focused on treating female AGA with autologous stem cells derived from human hair follicles. | 23 patients with AGA (Ludwig grade I–III). The aim of the study was to evaluate the clinical effect of AMT based on images before and 6 months after the treatment. | A significant improvement was observed on the visual analog scale (VAS) when comparing pre- and post-procedure photos (p < 0.001). |

| 10 | Vincenzi, C., Cameli, N., Pessei, V., Tosti, A. [70] | 2024 | The study highlighted the use of the Regenera® system for autologous micrografting in AGA treatment. Patients reported satisfactory hair improvement and treatment tolerability, indicating this regenerative approach as a promising tool for clinicians. | Combination of 2 studies involving the analysis of 30 patients in total. 17 patients with 1 time AMT/year vs. 13 patients with 2 times AMT/year. Clinical assessment with global photography using TrichoLab and patient satisfaction. | After 3 months versus baseline, hair diameter increases by 7.35% +/−1.89% (p < 1%). After 6 months versus baseline, hair diameter increases by 5.23% +/−1.78% (p < 1%). 69% (9/13) of the patients revealed an improvement. No statistically significant outcomes were seen 1 time AMT group vs. 2 times AMT. |

| 11 | Gentile, P. et al. [64] | 2025 | This multicentric, observational, evaluator-blinded study analysed autologous micrografts containing nanovesicles, exosomes, and follicle stem cells for AGA treatment. | 83 patients (52 with MPHL and 31 with FPHL). The treated patients were 60. Hair regrowth was evaluated with photography, physician’s and patient’s global assessment scales and phototrichograms at 1 year follow-up. In vitro analysis was performed through quantitative, morphological and size characterization of EVs with TEM and fluorescent microscopy. | A hair density (HD) increases of 28 ± 4 hairs/cm2 at T4 (12 months) vs. baseline in FPHL. In MPHL, an HD increase of 30 ± 5 hairs/cm2 at T4 (12 months) with an SSD in hair regrowth (p = 0.0012). The presence of EVs and their interaction with the surrounding cellular population were demonstrated. |

3.5. Comparison of Regenerative Treatments

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Y.; Tosti, A.; Wang, E.; Heilmann-Heimbach, S.; Aguh, C.; Jimenez, F.; Sung-Jan, L.; Kwon, O.; Plikus, M. Androgenetic alopecia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2025, 11, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Shen, M.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Tang, Y.; Xie, H.; Chen, X.; Li, J. Epidemiology and disease burden of androgenetic alopecia in college freshmen in China: A population-based study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norwood, O.T. Male pattern baldness: Classification and incidence. South Med. J. 1975, 68, 1359–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, E. Classification of the types of androgenetic alopecia (common baldness) occurring in the female sex. Br. J. Dermatol. 1977, 97, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingrassia, J.; Buontempo, M.; Alhanshali, L.; Akoh, C.; Glick, S.; Shapiro, J.; Lo Sicco, K. The financial burden of alopecia: A survey study. Int. J. Women’s Dermatol. 2023, 9, e118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nestor, M.S.; Ablon, G.; Gade, A.; Han, H.; Fischer, D.L. Treatment options for androgenetic alopecia: Efficacy, side effects, compliance, financial considerations, and ethics. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 3759–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Cui, Y.; Wu, J.; Jin, H. Efficacy and safety of dutasteride compared with finasteride in treating males with benign prostatic hyperplasia: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 1566–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger, A.; Tomic-Canic, M.; Tosti, A. Advances in Stem Cell-Based Therapy for Hair Loss. CellR4 Repair Replace. Regen. Reprogramming 2020, 8, e2894. [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama, M. Hair follicle bulge: A fascinating reservoir of epithelial stem cells. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2007, 46, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geyfman, M.; Plikus, M.V.; Treffeisen, E.; Andersen, B.; Paus, R. Resting no more: Re-defining telogen, the maintenance stage of the hair growth cycle. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2015, 90, 1179–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lolli, F.; Pallotti, F.; Rossi, A.; Fortuna, M.; Caro, G.; Lenzi, A.; Sansone, A.; Lombardo, F. Androgenetic alopecia: A review. Endocrine 2017, 57, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Diaz Duran, R.; Martinez-Ledesma, E.; Garcia-Garcia, M.; Gauzin, D.; Sarro-Ramírez, A.; Gonzalez-Carillo, C.; Rodríguez-Sardin, D.; Fuentes, A.; Cardenas-Lopez, A. The Biology and Genomics of Human Hair Follicles: A Focus on Androgenetic Alopecia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirastu, N.; Joshi, P.K.; de Vries, P.S.; Cornelis, M.; McKeigue, P.; Keum, N.; Franceschini, N.; Colombo, M.; Giovannuci, e.; Spiliopoulou, A.; et al. GWAS for male-pattern baldness identifies 71 susceptibility loci explaining 38% of the risk. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trüeb, R.M. Molecular mechanisms of androgenetic alopecia. Exp. Gerontol. 2002, 37, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellular Senescence: Ageing and Androgenetic Alopecia—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.westernu.edu/37088073/ (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Leirós, G.J.; Attorresi, A.I.; Balañá, M.E. Hair follicle stem cell differentiation is inhibited through cross-talk between Wnt/β-catenin and androgen signalling in dermal papilla cells from patients with androgenetic alopecia. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012, 166, 1035–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, B.; Li, Y.; Han, L.; Tang, X.; Deng, W.; Lai, W.; Wan, M. Dihydrotestosterone Regulates Hair Growth Through the Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway in C57BL/6 Mice and In Vitro Organ Culture. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inui, S.; Itami, S. Molecular basis of androgenetic alopecia: From androgen to paracrine mediators through dermal papilla. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2011, 61, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vañó, S.; Jaén, P. Practical Handbook of Hair Disorders #TricoHRC, 2nd ed.; Instituto Ramón y Cajal de Investigación Sanitaria: Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Oiwoh, S.O.; Enitan, A.O.; Adegbosin, O.T.; Akinboro, A.O.; Onayemi, E.O. Androgenetic Alopecia: A Review. Niger. Postgrad. Med. J. 2024, 31, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.D.; Tang, L.L.; Chen, H.J.; Wu, Y.; Li, W.Y.; Wen, S.J.; Lin, Y.K. Identification of immune microenvironment changes, immune-related pathways and genes in male androgenetic alopecia. Medicine 2023, 102, e35242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheisari, M.; Hamidi, A.B.; Hamedani, B.; Zerehpoush, F.B. Androgenetic alopecia; An attempt to target microinflammation. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e13266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahé, Y.F.; Michelet, J.F.; Billoni, N.; Jarrousse, F.; Buan, B.; Commo, S.; Saint-Léger, D.; Bernard, B. Androgenetic alopecia and microinflammation. Int. J. Dermatol. 2000, 39, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.Y.; Chen, J.Y.F.; Hsu, W.L.; Yu, S.; Chen, W.C.; Chiu, S.H.; Yang, H.R.; Lin, S.Y.; Wu, C.Y. Female Pattern Hair Loss: An Overview with Focus on the Genetics. Genes 2023, 14, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devjani, S.; Ezemma, O.; Kelley, K.J.; Stratton, E.; Senna, M. Androgenetic Alopecia: Therapy Update. Drugs 2023, 83, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Peng, H.; Yang, Y.; Lv, K.; Zhou, S.; Pan, X.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y.; Li, G.; Ma, D. Nitric oxide synergizes minoxidil delivered by transdermal hyaluronic acid liposomes for multimodal androgenetic-alopecia therapy. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 32, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiska, Y.M.; Mirmirani, P.; Roseborough, I.; Mathes, E.; Bhutani, T.; Ambrosy, A.; Aguh, C.; Bergfeld, W.; Callender, V.; Castelo-Soccio, L.; et al. Low-Dose Oral Minoxidil Initiation for Patients With Hair Loss: An International Modified Delphi Consensus Statement. JAMA Dermatol. 2025, 161, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Sun, J.; Xie, B.; Zhang, H.; Song, X. New Target for Minoxidil in the Treatment of Androgenetic Alopecia. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2023, 17, 2537–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Goren, A.; Dhurat, R.; Agrawal, S.; Sinclair, R.; Trüeb, R.; Vañó-Galván, S.; Chen, G.; Tan, Y.; Kovacevic, M.; et al. Tretinoin enhances minoxidil response in androgenetic alopecia patients by upregulating follicular sulfotransferase enzymes. Dermatol. Ther. 2019, 32, e12915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitalia, J.; Dhurat, R.; Goren, A.; McCoy, J.; Kovacevic, M.; Situm, M.; Naccarato, T.; Lotti, T. Characterization of follicular minoxidil sulfotransferase activity in a cohort of pattern hair loss patients from the Indian Subcontinent. Dermatol. Ther. 2018, 31, e12688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goren, A.; Castano, J.A.; McCoy, J.; Bermudez, F.; Lotti, T. Novel enzymatic assay predicts minoxidil response in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia. Dermatol. Ther. 2014, 27, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, A.; Godwin, M. The effectiveness of treatments for androgenetic alopecia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 77, 136–141.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DailyMed—PROPECIA-Finasteride Tablet, Film Coated. Available online: https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=6f904709-65aa-44ce-b144-b4c8a0416e36 (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Kaufman, K.D.; Dawber, R.P. Finasteride, a Type 2 5alpha-reductase inhibitor, in the treatment of men with androgenetic alopecia. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 1999, 8, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, L.; Hordinsky, M.; Fiedler, V.; Swinehart, J.; Unger, W.P.; Cotterill, P.C.; Thiboutot, D.M.; Lowe, N.; Jacobson, C.; Whiting, D.; et al. The effects of finasteride on scalp skin and serum androgen levels in men with androgenetic alopecia. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1999, 41, 550–554. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.J.; Shi, X.; Wu, T.; Zhang, M.D.; Tang, J.; Yin, G.M.; Long, Z.; He, L.Y.; Qi, L.; Wang, L. Sexual, physical, and overall adverse effects in patients treated with 5α-reductase inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian J. Androl. 2022, 24, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traish, A.M. Post-finasteride syndrome: A surmountable challenge for clinicians. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 113, 21–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, E.A.; Hordinsky, M.; Whiting, D.; Stough, D.; Hobbs, S.; Ellis, M.; Wilson, T.; Rittmaster, R. The importance of dual 5alpha-reductase inhibition in the treatment of male pattern hair loss: Results of a randomized placebo-controlled study of dutasteride versus finasteride. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2006, 55, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubelin Harcha, W.; Barboza Martínez, J.; Tsai, T.F.; Katsuoka, K.; Kawashima, M.; Tsuboi, R.; Barnes, A.; Ferron-Brady, G.; Chetty, D. A randomized, active- and placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of different doses of dutasteride versus placebo and finasteride in the treatment of male subjects with androgenetic alopecia. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014, 70, 489–498.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhurat, R.; Sharma, A.; Rudnicka, L.; Kroumpouzos, G.; Kassir, M.; Galadari, H.; Wollina, U.; Lotti, T.; Golubovic, M.; Binic, I.; et al. 5-Alpha reductase inhibitors in androgenetic alopecia: Shifting paradigms, current concepts, comparative efficacy, and safety. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e13379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozo-Pérez, L.; Tornero-Esteban, P.; López-Bran, E. Clinical and preclinical approach in AGA treatment: A review of current and new therapies in the regenerative field. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.Y.; Han, X.J.; Wu, J.; Yuan, Q.Y.; Zhou, J.; Yu, Z.P.; Han, X.H.; Guan, X.H. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Highlights a Contribution of Human Amniotic Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Derived Exosomes to Androgenetic Alopecia. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2025, 39, e70820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, P.; Gottlieb, S. Balancing Safety and Innovation for Cell-Based Regenerative Medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 954–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnoff, J.T.; Awan, T.M.; Borg-Stein, J.; Harmon, K.G.; Herman, D.C.; Malanga, G.; Master, Z.; Mautner, K.; Shapiro, S. American Medical Society for Sports Medicine Position Statement: Principles for the Responsible Use of Regenerative Medicine in Sports Medicine. Clin. J. Sport Med. Off. J. Can. Acad. Sport Med. 2021, 31, 530–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdin, R.; Zhang, Y.; Jimenez, J.J. Treatment of Androgenetic Alopecia Using PRP to Target Dysregulated Mechanisms and Pathways. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 843127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.; Khetarpal, S. Platelet-rich plasma for androgenetic alopecia: A review of the literature and proposed treatment protocol. Int. J. Womens Dermatol. 2019, 5, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camila Ospina Rios, M. The role of platelet-rich plasma in androgenetic alopecia: A comprehensive narrative review. Glob. J. Res. Anal. 2023, 12, 62–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, P.; Scioli, M.G.; Bielli, A.; Angelis, B.; De Sio, C.; De Fazio, D.; Ceccarelli, G.; Trivisonna, A.; Orlandi, A.; Cervelli, V.; et al. Platelet-Rich Plasma and Micrografts Enriched with Autologous Human Follicle Mesenchymal Stem Cells Improve Hair Re-Growth in Androgenetic Alopecia. Biomolecular Pathway Analysis and Clinical Evaluation. Biomedicines 2019, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Carviel, J.L. Meta-analysis of efficacy of platelet-rich plasma therapy for androgenetic alopecia. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2017, 28, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentile, P.; Garcovich, S. Systematic Review of Platelet-Rich Plasma Use in Androgenetic Alopecia Compared with Minoxidil®, Finasteride®, and Adult Stem Cell-Based Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, J.; Ho, A.; Sukhdeo, K.; Yin, L.; Sicco, K.L. Evaluation of platelet-rich plasma as a treatment for androgenetic alopecia: A randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 83, 1298–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Tang, X.; Zhang, X.; Cao, C.; Yu, M.; Wan, M. Adipose Mesenchymal Stromal Cell-Derived Exosomes Carrying MiR-122-5p Antagonize the Inhibitory Effect of Dihydrotestosterone on Hair Follicles by Targeting the TGF-β1/SMAD3 Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Cheng, M.; Xiao, T.; Qi, R.; Gao, X.; Chen, H.; Wu, Y.; Xu, X. miR-574-3p and miR-125a-5p in Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell Exosomes Synergistically Target TGF-β1/SMAD2 Signaling Pathway for the Treatment of Androgenic Alopecia. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2025, 145, 2719–2735.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Liu, J.; Xie, X.; Jin, Q.; Yang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. Restoration of follicular β-catenin signaling by mesenchymal stem cells promotes hair growth in mice with androgenetic alopecia. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, Y.; Ntege, E.H.; Sunami, H.; Inoue, Y. Regenerative medicine strategies for hair growth and regeneration: A narrative review of literature. Regen. Ther. 2022, 21, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Yu, L.; Ma, T.; Xu, W.; Zian, H.; Sun, Y.; Shi, H. Small extracellular vesicles isolation and separation: Current techniques, pending questions and clinical applications. Theranostics 2022, 12, 6548–6575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yao, J.; Jiang, Q.; Shi, Y.; Ge, W.; Xu, X. Engineered Exosomes Biopotentiated Hydrogel Promote Hair Follicle Growth via Reprogramming the Perifollicular Microenvironment. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Deng, T.; Ben, Y.; Lu, R.; Zhou, X.; Yan, R.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; et al. Subcutaneous injection of genetically engineered exosomes for androgenic alopecia treatment. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1614090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queen, D.; Avram, M.R. Exosomes for Treating Hair Loss: A Review of Clinical Studies. Dermatol. Surg. 2025, 51, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krefft-Trzciniecka, K.; Piętowska, Z.; Pakiet, A.; Nowicka, D.; Szepietowski, J.C. Short-Term Clinical Assessment of Treating Female Androgenetic Alopecia with Autologous Stem Cells Derived from Human Hair Follicles. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, X.; Valenzuela, M.; Tuffet, J. Clinical and Histological Evaluation of the Regenera® Method for the Treatment of Androgenetic Alopecia. Int. Educ. Appl. Sci. Res. J. 2018, 3, 2456–5040. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, R.G.; Rosell, J.M.C.; Ceccarelli, G.; De Sio, C.; De Angelis, G.; Pinto, H.; Astarita, C.; Graziano, A. Progenitor-cell-enriched micrografts as a novel option for the management of androgenetic alopecia. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 235, 4587–4593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zari, S. Short-Term Efficacy of Autologous Cellular Micrografts in Male and Female Androgenetic Alopecia: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 14, 1725–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, P.; Garcovich, S.; Perego, F.; Arsiwala, N.; Faruk Yavuz, M.; Pessei, V.; Pusceddu, T.; Zavan, B.; Arsiwala, S. Autologous Micrografts Containing Nanovesicles, Exosomes, and Follicle Stem Cells in Androgenetic Alopecia: In Vitro and In Vivo Analysis Through a Multicentric, Observational, Evaluator-Blinded Study. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2025, 49, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astarita, C.; Arora, C.L.; Trovato, L. Tissue regeneration: An overview from stem cells to micrografts. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 300060520914794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, L.; Monti, M.; del Fante, C.; Cervio, M.; Lampinen, M.; Ambrosio, L.; Redi, C.A.; Perotti, C.; Kankuri, E.; Ambrosio, G.; et al. A New Medical Device Rigeneracons Allows to Obtain Viable Micro-Grafts From Mechanical Disaggregation of Human Tissues. J. Cell Physiol. 2015, 230, 2299–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, X.; Valenzuela, M.; Tuffet, J. Microscopic and Histologic Evaluation of the Regenera method for the Treatment of Androgenetic Alopecia in a Small Number of Cases. Int. J. Res. Studies Med. Health Sci. 2017, 2, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hernán, P.; Rafael, G.; José, C. Dermoscopy Is the Crucial Step for Proper Outcome Prospection When Treating Androgenetic Alopecia with the Regenera® Protocol: A Score Proposal. Int. J. Clin. Dev. Anat. 2018, 4, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawwam, S.; Ismail, M.; Elhawary, E. The Role of Autologous Micrografts Injection from The Scalp Tissue in The Treatment of COVID-19 Associated Telogen Effluvium: Clinical and Trichoscopic Evaluation. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincenzi, C.; Cameli, N.; Pessei, V.; Tosti, A. Role of Autologous Micrografting Technology through Rigenera® System in the Treatment of Androgenetic Alopecia. Skin Appendage Disord. 2025, 11, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.; Grimalt, R. A Review of Platelet-Rich Plasma: History, Biology, Mechanism of Action, and Classification. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018, 4, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, S.; Amuzescu, A.; Mitran, C.; Mitran, M.; Matei, C.; Constantin, C.; Tampa, M.; Neagu, M. Eficàcia de la teràpia amb plasma ric en plaquetes en l’alopècia androgènica: Una metaanàlisi. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Cole, J.; Deutsch, D.; Everts, P.; Niedbalski, R.; Panchaprateep, R.; Rinaldi, F.; Rose, P.; Sinclair, R.; Vogel, J.; et al. Plasma ric en plaquetes com a tractament per a l’alopècia androgenètica. Dermatol. Surg. 2019, 45, 1262–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mysore, V.; Alexander, S.; Nepal, S.; Venkataram, A. Regenerative Medicine Treatments for Androgenetic Alopecia. Indian J Plast. Surg. 2021, 54, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| MPHL | FPHL |

|---|---|

| Anisotrichosis (>20% miniaturized hair) | Anisotrichosis (>10% miniaturized hair) |

| Peripilar sign (local microinflammation) | Lower diameter of hair shafts in the frontal area vs. occipital area |

| Decreased number of hair shafts | Yellow dots |

| Yellow dots | Increase in the follicular units with one single hair shaft |

| Focal atrichia (loss of follicular units) |

| Treatment | Source Tissue | Invasive Profile/Method of Extraction | Number of Sessions | Protocol Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRP | Blood | Minimally/blood extraction | 3–5 sessions | Point-of-Care |

| AT-MSCs | Adipose tissue | Highly/liposuction | 4–6 sessions | Laboratory-dependant |

| ADSVCs | Adipose tissue Stromal Vascular Fraction | Highly/liposuction | 1–2 sessions | Point-of Care |

| ADRCs | Adipose tissue Cells | Highly/liposuction | 1–2 sessions | Point-of-Care |

| Exosomes | Several (natural/synthetic) | Depends on the source/cultivation | Lack of data | Laboratory-dependant |

| AMT | Scalp | Minimally/tissue biopsy | 1 session | Point-of-Care |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, V.; Tosti, A.; Ivanova, A.; Huertas, M.; Vincenzi, C. A Decade of Autologous Micrografting Technology in Hair Restoration: A Review of Clinical Evidence and the Evolving Landscape of Regenerative Treatments. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12060254

Wang V, Tosti A, Ivanova A, Huertas M, Vincenzi C. A Decade of Autologous Micrografting Technology in Hair Restoration: A Review of Clinical Evidence and the Evolving Landscape of Regenerative Treatments. Cosmetics. 2025; 12(6):254. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12060254

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Vera, Antonella Tosti, Antoniya Ivanova, Marta Huertas, and Colombina Vincenzi. 2025. "A Decade of Autologous Micrografting Technology in Hair Restoration: A Review of Clinical Evidence and the Evolving Landscape of Regenerative Treatments" Cosmetics 12, no. 6: 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12060254

APA StyleWang, V., Tosti, A., Ivanova, A., Huertas, M., & Vincenzi, C. (2025). A Decade of Autologous Micrografting Technology in Hair Restoration: A Review of Clinical Evidence and the Evolving Landscape of Regenerative Treatments. Cosmetics, 12(6), 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics12060254