1. Introduction

For ages, aromatic plants have been deeply involved in human medicine and everyday life. Nowadays, aromatic plants are regarded as a rich and important source of therapeutic agents, and some novel pharmaceuticals are expected to be derived from plants in the next decade. Currently, the research on aromatic plants is remarkable [

1,

2]. Essential oils (EOs) are natural and complex mixtures containing many volatile compounds. EOs are primarily produced by aromatic plants as secondary metabolites and have some important functions in nature, such as deterring herbivores or attracting pollinators. EOs are associated with distinct and potent aromas and a wide variety of biological activities, including antibacterial, antifungal, virucidal, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, insecticidal, etc., properties [

1,

3].

Nowadays, EOs play a significant role not only in the pharmaceutical industry but also in the sanitary, cosmetic, agricultural, and food industries.

According to recent reports, the global market for EOs is expected to grow significantly in the next five years. For 2023, the EO market was reported to reach more than USD 23 billion, and in 2030, it is expected to reach more than USD 42 billion [

4]. The European market of EOs represents a significant share of the global market. In Europe, the EO market is expected to reach a projected revenue of more than USD 20 billion in 2030. For 2023, the European market reached a revenue of more than USD 11 billion [

4].

The positive trend in the EO market is associated with the increasing demand for natural products worldwide, including natural products for personal care, cosmetics, supplementation, and remedies for the management of different health conditions. Moreover, the area of applications of EOs is constantly expanding. Currently, many EOs and compounds isolated from EOs are studied as alternatives to synthetic preservatives, as safer alternatives to pesticides, as natural antibacterial agents, and as promising novel drug candidates, etc. [

5,

6,

7,

8].

EOs have always been regarded as vital for the cosmetic industry [

6]. Although, in general, EOs are considered safe and non-toxic, these natural products contain numerous different nonpolar compounds with diverse chemical structures and diverse biological activity. This is regarded as one of the key points for their significant potential to cause allergic reactions [

7,

8]. At the same time, EOs are categorized as products that are frequently susceptible to forgery. Currently, the adulteration of EOs is regarded as a serious problem and could expose consumers to significant risks [

9].

The purpose of this study was to explore the use of EOs in daily life, including frequency, preferences, and health-related outcomes among Bulgarian adults. This is the first study regarding EO usage performed in Bulgaria.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Participants, and Setting

A cross-sectional questionnaire-based study was conducted in January 2025. Study participants included Bulgarian adults >18 years old. The respondents and their responses remained anonymous.

2.2. Study Tool

A questionnaire (

Supplementary Materials) was developed by the investigators who are experts in pharmaceutical chemistry, pharmaceutical analysis, pharmaceutical technology, and pharmacy practice. An initial draft of the questionnaire was evaluated by three researchers to ensure accuracy, structure, content clarity, and correct grammar. Then, a pilot study involving 20 participants assessed the instrument’s face and content validity. Readability and completion time were also evaluated. Adjustments were incorporated in the revised version of the questionnaire according to participants’ feedback. The pre-tested samples were excluded from the final analysis.

The final version of the study tool contains 19 questions divided into two sections.

Section 1 included questions regarding the sociodemographic characteristics of study participants (age, sex, occupation and employment status, education, and place of residence) and one dichotomous question (yes or no) about the usage of EOs. This section was composed of 6 questions. EO non-users were not directed to

Section 2.

Section 2 explored the utilization of EOs in daily life, including frequency of purchase, types of EOs used, reasons for use, personal preferences, places of purchase of EOs, satisfaction with usage, and health-related outcomes (e.g., observed side effects). This section included 13 questions. In relation to the utilization of specific EOs, a total of 21 types of EOs (including lavender, tea tree, rosemary, chamomile, rose, peppermint, orange, mandarin, lemon, clove, oregano, frankincense, ylang-ylang, cedar, pine, citronella, thyme, eucalyptus, lemon balm, and blends) were presented as options.

2.3. Data Collection

The study tool was generated using the Google Forms™ platform. At the beginning of the questionnaire, a consent statement was supplied, which included the objective of the study, an estimate of how long it would take, an explanation of the confidentiality of replies, and the voluntary nature of participation. Respondents gave their agreement by accepting the prompt to start answering the questions in the online tool. Individual identifiers/e-mails were not collected. The link to the survey was distributed online via social media platforms (Facebook and Instagram).

2.4. Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) v. 19 and MS Office Excel for Windows 10. The demographic characteristics and descriptive statistics of participants are presented as frequencies and percentages. A Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was performed to study whether there were significant differences between the dependent variable and the independent variables. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

A total of 1848 respondents completed the survey, of whom 68.7% (n = 1269) reported using EOs, while the remaining 31.3% indicated no usage.

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the two groups—users and non-users. In both groups, females represented most respondents. The majority of EO users were within the age groups of 18–29 years old (35.7%) or 30–40 years old (25.0%). In terms of education, individuals with a university degree predominate in both groups. Approximately one-third (32.2%) of EO consumers reported being healthcare professionals. The majority of the consumers were from cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants (84.6%).

3.2. Utilization of Specific EOs

Figure 1 illustrates the types of EOs most commonly used by Bulgarian consumers. The three most used EOs among surveyed adults include lavender EO (68.6%), tea tree EO (43.7%), and peppermint EO (39.5%).

More than half of the study’s participants indicated using EOs for aromatherapy or cosmetic purposes, such as improving skin/hair condition or as a fragrance (

Table 2).

Table 3 illustrates the association of the relevant sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents and their practices regarding the use of EOs. A statistically significant difference (

p < 0.001) was observed between sexes and the use of EOs for the treatment of hair loss and scalp care, with females reporting a more frequent use of the products compared to men. Employed respondents demonstrated a higher frequency of using medicinal products containing EOs (

p < 0.01).

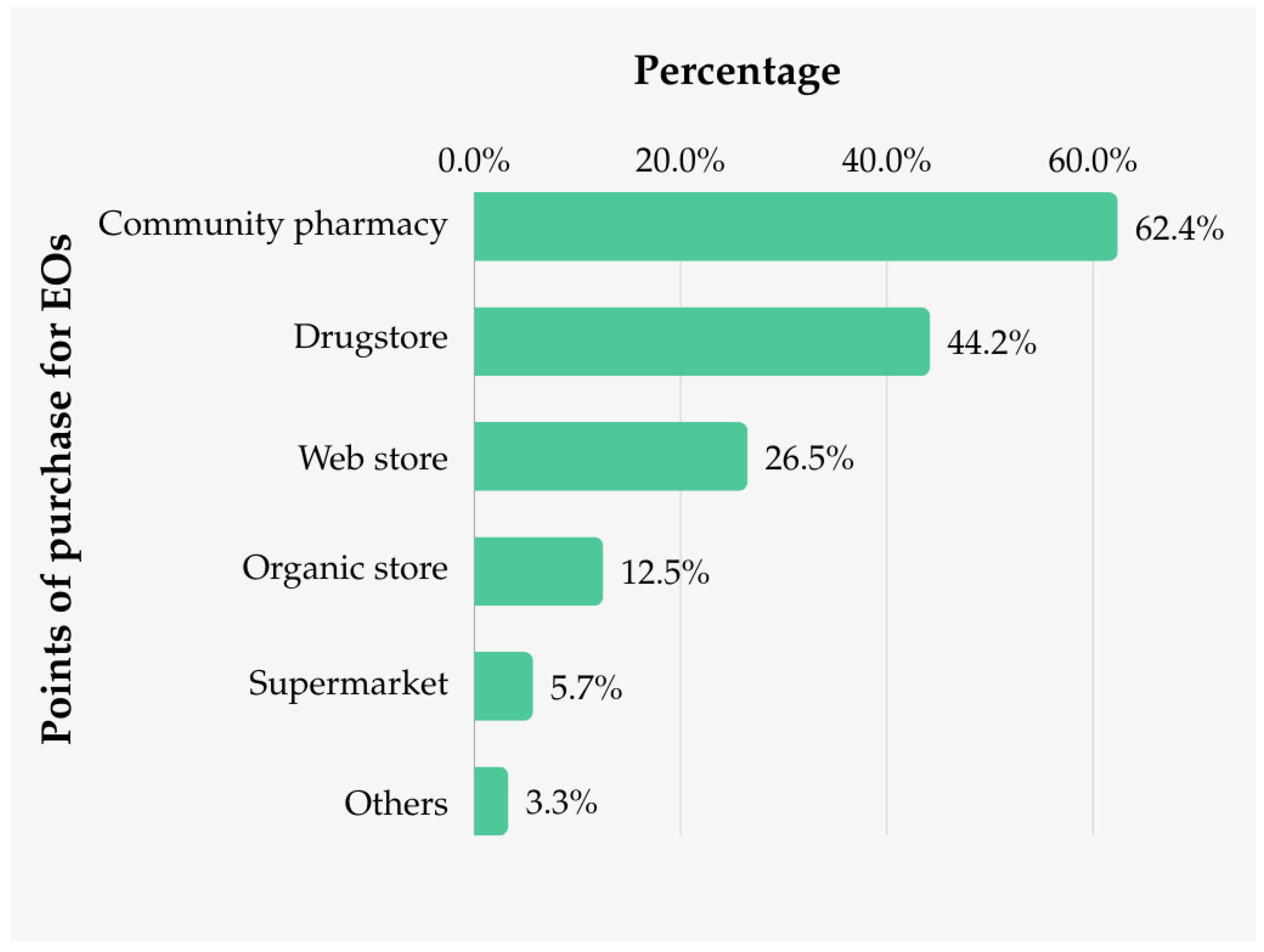

The most frequently used points of purchase for EOs, according to our respondents, were community pharmacies (63.4%), followed by drugstores (44.2%) and web stores (26.5%) (

Figure 2).

The majority of the participants (81%) reported being satisfied/very satisfied with the use of EOs as hair growth stimulants. Similar satisfaction levels were obtained regarding the use of EO-based insect repellents (

Table 4).

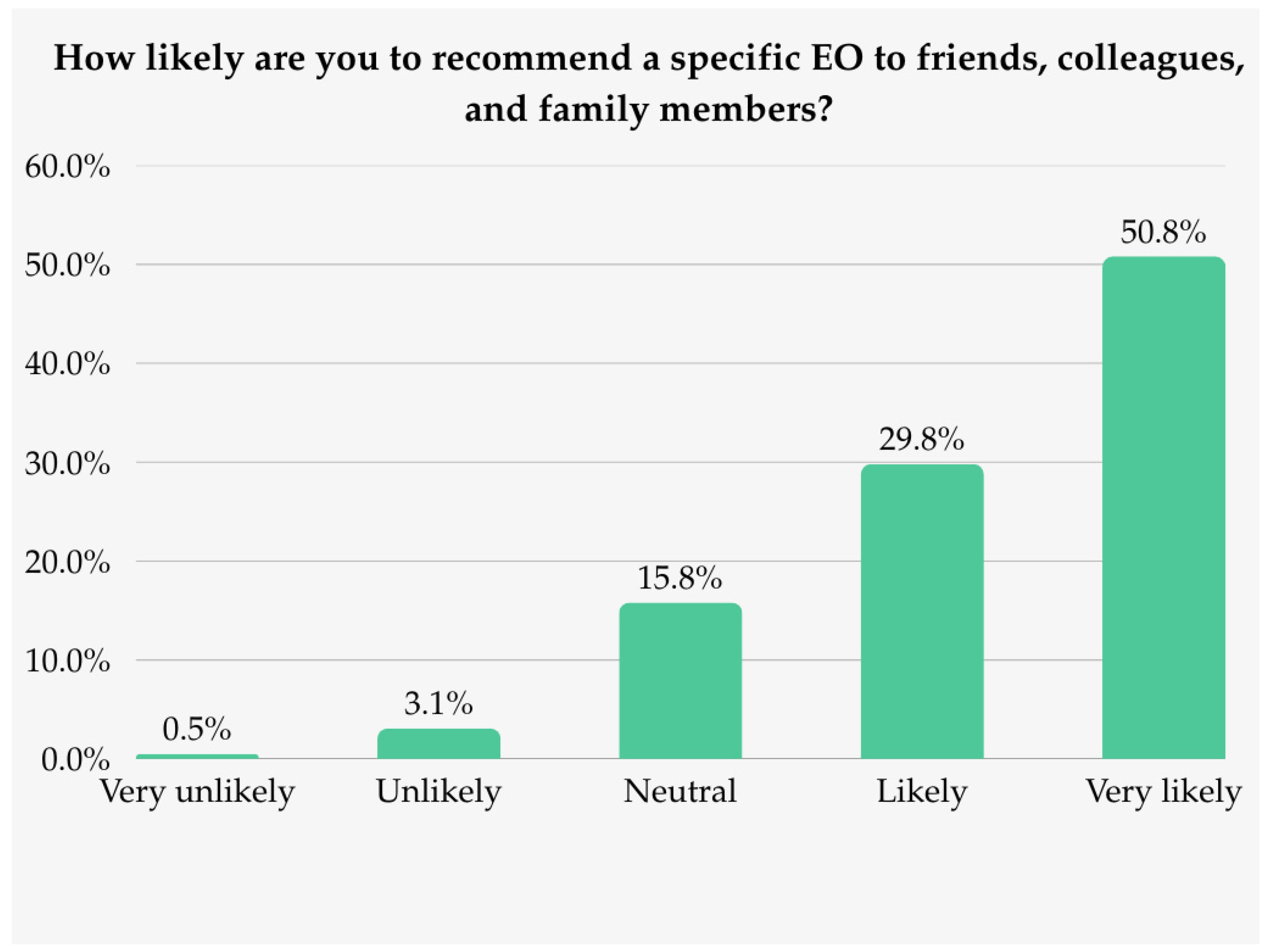

Most of the Bulgarian adults participating in the survey (80.6%) indicated a strong likelihood of recommending the use of specific EOs to friends, colleagues, family members, or relatives (

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

The study was associated with some important findings: usage of EOs among Bulgarian adults is widespread (68.7% of the respondents were EO users); secondly, it was found that EO usage was significantly associated with younger age, higher education, and female sex (

p < 0.001). The most used essential oil (EO), according to our respondents, was lavender. Bulgaria has deep traditions in the cultivation of lavender. It is considered that these traditions started in 1907, and nowadays, the country is regarded as one of the leaders in the cultivation and export of lavender. Some of the most important factors for this are the excellent adaptation of the herb to the Bulgarian geographical latitudes and the mild climate [

10]. However, similar results were obtained from other studies conducted among the general population in countries like France, China, the USA, and Turkey [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Bulgaria and Turkey are also associated with traditions in the cultivation of

Rosa Damascena Mill. and in the production of rose oil [

15]. At the same time, rose oil is regarded as one of the most expensive EOs, and this could be the possible reason for its less frequent usage compared to other EOs like lavender EO [

16].

4.1. Main Purposes of EO Applications

4.1.1. Aromatherapy

Most of the respondents reported the use of EOs for aromatherapy (59.1%). Aromatherapy is used to reduce stress, enhance mood, reduce fatigue, and improve the quality of sleep. Moreover, nowadays, it is regarded as a nonpharmacological natural method for the improvement of the symptoms of some medical conditions. Peppermint and lavender EOs are among the most important EOs used in aromatherapy [

17]. This correlates with the findings of our study: the lavender EO is the most frequently used essential oil (68.6%) among Bulgarian adults, followed by tea tree and peppermint EOs. According to some studies, the use of lavender EO in aromatherapy is associated with important benefits, including a decrease in arousal levels and an improvement in attention [

16]. Moreover, aromatherapy with lavender oil could be successfully involved in the management of depression, anxiety, and mild sleep disorders [

18,

19,

20]. In general, the main constituents in lavender EOs are linalool and linalyl acetate [

21,

22], compounds with pronounced neuroprotective effects and significant anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties [

23].

In recent years, some randomized controlled studies have evaluated the relationship between peppermint EO aromatherapy and different medical conditions [

5,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. It was reported that aromatherapy with peppermint EOs could reduce the symptoms of fatigue in hypothyroid and prediabetic patients [

25,

26]. At the same time, aromatherapy with peppermint EO was reported to reduce anxiety in patients with acute coronary syndrome [

27]. In 2020, Nuriye Efe Ertürk and Sultan Taşcı reported that peppermint EO significantly reduced the frequency of nausea and vomiting in cancer patients [

5]. In 2023, Mesut Meşe and Serdar Sarıtaş reported that the inhalation of peppermint oil reduced pain and anxiety levels in patients after lumbar discectomy surgery [

28]. A small pilot study suggested that peppermint EO could be used in the management of mental exhaustion and moderate burnout [

24].

It seems that aromatherapy could be successfully involved in the management of different medical conditions and symptoms. However, some limitations should be considered, including the great differences between the chemical profiles of EOs obtained from the same plant species. Moreover, there is a lack of validated protocols in this area.

4.1.2. Use of EOs as Hair Stimulants

Currently, there is a high demand for natural products for hair/scalp treatments and care. The absence of cumulative synthetic compounds is regarded as a benefit for many consumers. The main characteristics that are reported to be important for consumers in the hair care category are not only the natural ingredients but also the lack of sulfates, silicones, parabens, and other compounds perceived as harmful [

29]. This has pushed the cosmetic industry towards research for natural, green ingredients for the production of new products and to reformulate others [

8].

EOs can affect scalp and hair health after topical application. In general, this is associated with antibacterial, antifungal, and antioxidant activity [

29]. The application of some EOs on the scalp is associated with some important benefits, including the promotion of an increase in the hair shaft density, a cleaning effect on the hair bulb, and strengthening of the entire bulb/stem system. Some of the most important EOs involved in the stimulation of hair growth and improvement of scalp health are

Rosmarinus officinalis EO,

Eucalyptus globulus EO,

Matricaria chamomilla L. EO, and others. Currently, on the European market, there are many popular products for hair stimulation that include mixtures of different EOs (

Rosmarinus officinalis EO,

Pelargonium graveolens EO,

Lavandula angustifolia Mill. EO,

Eucalyptus globulus EO, and

Matricaria chamomilla L. EO) and other components to achieve synergism. Some of these products include hair growth serum sprays, masks, or tonics. According to manufacturers the main benefits after the long-term use of these products include a reduction in hair loss, the stimulation of faster hair growth, the enhancement of the density of the hair, an improvement in the structure and shine of the hair, an improvement in scalp health, the expenditure of the life of the hair, etc. [

8].

More than half (59%) of the EO consumers in our study reported the use of EOs for the treatment of hair loss, stimulation of hair growth, or scalp care. Most of these respondents expressed satisfaction with the achieved outcomes.

Currently, there are different European regulations concerning EOs [

30,

31,

32]. Regulation (EC) N° 1223/2009 on cosmetic products is the main regulatory framework governing finished cosmetic products placed on the European Union (EU) market [

32]. All products containing EOs intended to be used as hair stimulants in the EU follow Regulation (EC) N° 1223/2009 [

32]. According to this regulation, a cosmetic product is defined as “any substance or mixture intended to be applied to the external surfaces of the human body including epidermis, hair, nails, lips, etc., for the sole or main purpose of cleaning, perfuming, changing their appearance, or correcting body odors”. The regulation replaced the Directive 76/768/EC [

30], adopted in 1976, and has some significant strengths compared to the old directive including better safety requirements for cosmetic products, and the introduction of the notion of a ‘responsible person’ (this allows the precise identification of the responsible person and outlines their obligations); a centralized notification of all cosmetic products placed on the EU market and reports of serious undesirable effects, colourants, preservatives and UV filters must be explicitly authorized.

4.1.3. Medicinal Products Containing EOs

In the EU, EOs intended for medical use are regarded as herbal medicinal products (HMPs) and traditional HMPs [

33]. Currently, there are some important HMPs on the pharmaceutical market containing EOs [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. Most of these products are used in the management of conditions such as insomnia, anxiety (

Lavandula angustifolia Mill), cough, etc. [

46,

47]. Given their widespread availability and popularity, EOs used as active substances in medicinal products must meet specific standards for efficacy, quality, and safety. At the EU level, a simplified registration process for traditional HMPs was introduced in 2004 with the adoption of Directive 2004/24/EU, also known as the Herbal Medicines Directive (Directive 2004/24/EC, 2004) [

31]. HMPs containing EOs for oral intake in Bulgaria are limited and are mainly intended for the treatment of symptoms of sinusitis, bronchitis, and temporary anxiety in adults, including one or more temporary symptoms, such as restlessness, tension, or sleep disturbance [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

More than half (55.6%) of respondents reported an intake of medicinal products containing EOs, while 23.2% of consumers indicated ambiguity if they have ever taken medicinal products containing EOs. However, it is highly likely that most of the consumers have had an oral intake of HMPs containing EOs but are not too familiar with the content of the medications they have taken.

For example, the

Mentha piperita L. tincture oral drop solution is a quite popular OTC product [

34] that contains not only

Mentha piperita L. tincture but also some amount of

Mentha piperita L. EO (peppermint oil). Normally, this EO is obtained from the fresh aerial parts of the flowering

Mentha piperita L.

According to the scientific conclusions of the EMA Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products, HMPs containing peppermint oil are available in solid, semi-solid, or liquid forms to be taken by mouth, applied to the skin, sprayed in the mouth, or inhaled. Peppermint oil containing HMPs is also available in different combinations with other plant extracts. In general, oral intake of this EO is associated with the relief of stomach cramps. Peppermint EO’s mechanism of action is still not fully clarified. However, it is considered that this EO relaxes the smooth muscles of the intestines by affecting calcium channels, reducing muscle contractions, and potentially offering relief from pain or discomfort.

Other very popular OTC medicines—Gelomyrtol/Myrtol

® (300/120 mg)—are often recommended by physicians/pharmacists to manage the symptoms of acute or chronic sinusitis and bronchitis [

35,

36].

Anise EO containing HMPs are another important group of natural products used to manage the symptoms of mild indigestion complaints. Moreover, these HMPs can be used as expectorants for coughs associated with colds. Anise EO is obtained by steam distillation of the dry ripe fruits of the plant

Pimpinella anisum L. Anise EO containing HMPs are available in a solid or liquid form for peroral intake [

37]. Anise EO may be found in medicines containing a combination with other EOs or plant extracts.

4.1.4. EOs as Repellents

Nowadays, mosquito control and personal protection are regarded as important issues worldwide. However, these concerns are considered critical, especially for tropical Africa, because of some mosquito-borne diseases including malaria.

Repellents are one of the most effective protection methods against mosquitos. In the last decade, a great demand was reported for natural products for protection that balances effectiveness with safety and environmental impact.

Currently,

N,

N-diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET) is one of the most widely used compounds in mosquito repellents [

48]. According to recent studies, repellents containing DDET are widely used. For example, about 30% of the US population is using such products [

49]. However, DEET is associated with many adverse reactions and toxicity [

50].

However, many studies published in recent years indicated that EOs may serve as an eco-friendly and much safer alternative to the classic mosquito repellents [

51,

52,

53]. Due to their repellent properties, some EOs have been used since ancient times in civilizations such as Egypt, India, and China. According to our survey, 23.4% of respondents reported using EOs as insect repellents. Additionally, one-third of surveyed adults reported that the primary benefit they expect from using EOs is insect protection. Citronella EO is a common ingredient in most of the commercially available repellents of natural origin. The efficacy of citronella EO is mainly due to biologically active substances such as citronellal, citronellol, and geraniol. Except for mosquito repellent action, the latter is also associated with antimicrobial, anthelmintic, antioxidant, and wound healing activities [

54]. Almost one-quarter (19%) of the study’s participants indicated the use of citronella EO. Furthermore, most respondents (86.3%) considered EO-based repellents, such as those containing citronella, to be effective.

The eucalyptus and geranium EOs are considered to provide good repellent activity as well [

55]. The EO of

Thymus vulgaris and its main volatile compounds are also associated with strong repellent activity [

1,

56].

A major drawback of EOs exhibiting repellent activity is the short duration of protection due to their high volatility. For example, citronella EO-based repellents should be reapplied every 20–60 min [

53]. Essential oil-based mosquito repellents are easy to apply to the skin or clothing, are non-toxic, and are an affordable solution, especially in developing countries [

57]. Moreover, citronella EO-based repellents could be used for the protection of small children.

4.2. Adverse Reactions Associated with EOs

Most of the respondents reported no adverse reactions after the application or intake of EOs. However, 4.0% reported contact dermatitis, skin irritation, and allergic reactions. In fact, other studies also reported some adverse reactions after topical applications or inhalation of EOs. The most commonly reported adverse reaction was skin irritation and contact dermatitis after exposure to lavender, peppermint, tea tree, and ylang-ylang EOs [

58]. In general, patients experienced a full recovery after 48 h. However, in some cases, the recovery process lasted for an extended period of time (up to 1 year), and oral or topical corticosteroids were involved in the treatment [

59,

60].

4.3. Comparison to Similar Studies

The current study is associated with a large sample size (

n = 1848) compared to similar studies (

Table 5). However, many similarities were found between the studies, including that the consumption of EOs is considerable among the general population in different countries, that lavender EO is the most frequently used EO, and that the EO’s application/intake could provoke some adverse reactions, including rash, skin irritation, and allergy.

4.4. Limitations of the Study

Despite the large sample size (n = 1848), our study has several limitations that should be noted. Firstly, no data regarding pregnancy status, marital status, or overall health status were collected. Secondly, specific information regarding the body sites for the dermal application of EOs was not provided. Additionally, the duration of use of specific EOs was not reported. Since this study employs a cross-sectional design, it does not permit the assessment of causal relationships. Furthermore, self-reported data may be subject to the effects of recall bias and social desirability bias, thereby affecting the accuracy of the results. Using social media to recruit survey participants also presents a considerable risk of undercoverage bias. Even in today’s digital era, not all individuals within the target demographic can be reached through online platforms such as Facebook and Instagram. Furthermore, data show that frequent Internet users are generally younger and highly educated.

5. Conclusions

Nowadays, EOs play a significant role not only in the pharmaceutical industry but also in the sanitary, cosmetic, agricultural, and food industries. According to recent reports, the global market of EOs is expected to grow significantly in the next five years.

This is the first study to explore the use of EOs in daily life, including frequency, preferences, and health-related outcomes among Bulgarian adults. The present study revealed several significant findings. Firstly, the use of EOs among Bulgarian adults was found to be widespread, with 68.7% of respondents reporting usage. Secondly, EO usage demonstrated statistically significant associations with younger age, education level, and female gender. Furthermore, the majority of EO users did not report any adverse effects following use. However, 4.0% of participants reported experiencing contact dermatitis after EO application. These findings confirm the high potential of EOs as green and safer alternatives to many synthetic compounds. Bulgarian adults use EOs for various applications, including skin care, general wellness, aromatherapy, and repellents. The majority of the consumers of EOs would recommend EOs to other people. Moreover, the satisfaction level with the use of EOs was found to be significant.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.I., D.G.-K., R.S. and N.K.; methodology, S.I., D.G.-K., R.S. and N.K.; software, R.S.; validation, R.S., D.G.-K. and S.I.; formal analysis, R.S.; investigation, S.I., D.G.-K., R.S. and N.K.; resources, S.I. and R.S.; data curation, S.I., D.G.-K., R.S. and N.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.I., R.S. and N.K.; writing—review and editing, S.I. and D.G.-K.; visualization, S.I. and R.S.; supervision, S.I., K.I. and D.G.-K.; project administration, S.I., K.I. and D.G.-K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Approval by an ethics committee was not required for this study as it was sociological in nature from a methodological perspective and did not involve clinical research. No personal data were collected, stored, or analyzed.

Informed Consent Statement

At the beginning of the questionnaire, a consent statement was provided, outlining the study’s objectives, the estimated completion time, the confidentiality of responses, and the voluntary nature of participation. Respondents indicated their informed consent by proceeding with the online questionnaire.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jaramillo, S.P.; Calva, J.; Jiménez, A.; Armijos, C. Isolation of Geranyl Acetate and Chemical Analysis of the Essential Oil from Melaleuca armillaris (Sol. Ex Gaertn.) Sm. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crișan, I.; Ona, A.; Vârban, D.; Muntean, L.; Vârban, R.; Stoie, A.; Mihăiescu, T.; Morea, A. Current Trends for Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) Crops and Products with Emphasis on Essential Oil Quality. Plants 2023, 12, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.K.; Kumar, P.; Singh, P.; Tripathi, N.N.; Bajpai, V.K. Essential Oils: Sources of Antimicrobials and Food Preservatives. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horizon Report. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/horizon/outlook/essential-oils-market-size/global (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Efe Ertürk, N.; Taşcı, S. The Effects of Peppermint Oil on Nausea, Vomiting and Retching in Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy: An Open Label Quasi–Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. Complement. Ther. Med. 2021, 56, 102587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharmeen, J.; Mahomoodally, F.; Zengin, G.; Maggi, F. Essential Oils as Natural Sources of Fragrance Compounds for Cosmetics and Cosmeceuticals. Molecules 2021, 26, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkic, A.; Stappen, I. Essential Oils and Their Single Compounds in Cosmetics—A Critical Review. Cosmetics 2018, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, E.; Lucia, A. Essential Oils and Their Individual Components in Cosmetic Products. Cosmetics 2021, 8, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schripsema, J.; Da Silva, S.M.; Dagnino, D. Differential NMR and Chromatography for the Detection and Analysis of Adulteration of Vetiver Essential Oils. Talanta 2022, 237, 122928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenova, A.; Popova, T.P.; Bankova, R.; Ignatov, I. In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity of Bulgarian Lavender Essential Oil. Acta Microbiol. Bulg. 2024, 40, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornic, N.; Ficheux, A.S.; Roudot, A.C.; Saboureau, D.; Ezzedine, K. Usage Patterns of Aromatherapy among the French General Population: A Descriptive Study Focusing on Dermal Exposure. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2016, 76, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Nakai, S. Usage Patterns of Aromatherapy Essential Oil among Chinese Consumers. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodier, M.C.; Zhang, A.J.; Nikle, A.B.; Hylwa, S.A.; Goldfarb, N.I.; Warshaw, E.M. Use of Essential Oils: A General Population Survey. Contact Dermat. 2019, 80, 391–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gökkaya, İ.; Koçer, G.G.; Renda, G. What Does a Community Think About Aromatherapy? Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2024, 38, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agaoglu, Y.S. Rose Oil Industry and the Production of Oil Rose (Rosa damascena Mill.) in Turkey. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2000, 14, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloggi, E.; Menicucci, D.; Cesari, V.; Frumento, S.; Gemignani, A.; Bertoli, A. Lavender Aromatherapy: A Systematic Review from Essential Oil Quality and Administration Methods to Cognitive Enhancing Effects. Appl. Psych. Health Well-Being 2022, 14, 663–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavikian, S.; Fallahi, M.; Khatony, A. Comparing the Effect of Aromatherapy with Peppermint and Lavender Essential Oils on Fatigue of Cardiac Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 9925945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari-Koulaee, A.; Elyasi, F.; Taraghi, Z.; Ilali, E.S.; Moosazadeh, M. A Systematic Review of the Effects of Aromatherapy with Lavender Essential Oil on Depression. Cent. Asian J. Glob. Health 2020, 9, e442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanifar, S.; Bagheri-Saveh, M.I.; Nezakati, A.; Mohammadi, R.; Seidi, J. The Effect of Music Therapy and Aromatherapy with Chamomile-Lavender Essential Oil on the Anxiety of Clinical Nurses: A Randomized and Double-Blind Clinical Trial. J. Med. Life 2020, 13, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkaraman, A.; Dügüm, Ö.; Özen Yılmaz, H.; Usta Yesilbalkan, Ö. Aromatherapy: The Effect of Lavender on Anxiety and Sleep Quality in Patients Treated with Chemotherapy. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 22, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokajewicz, K.; Białoń, M.; Svydenko, L.; Fedin, R.; Hudz, N. Chemical Composition of the Essential Oil of the New Cultivars of Lavandula angustifolia Mill. Bred in Ukraine. Molecules 2021, 26, 5681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorova, V.; Ivanov, K.; Georgieva, Y.; Karcheva-Bahchevanska, D.; Ivanova, S. Comparison between the Chemical Composition of Essential Oil from Commercial Products and Biocultivated Lavandula angustifolia Mill. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2023, 2023, 1997157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, É.R.Q.; Maia, J.G.S.; Fontes-Júnior, E.A.; Do Socorro Ferraz Maia, C. Linalool as a Therapeutic and Medicinal Tool in Depression Treatment: A Review. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2022, 20, 1073–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varney, E.; Buckle, J. Effect of Inhaled Essential Oils on Mental Exhaustion and Moderate Burnout: A Small Pilot Study. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2013, 19, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, J.; Hires, C.Y.; Dunne, E.W.; Keenan, L.A. Aromatherapy Reduces Fatigue among Women with Hypothyroidism: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2020, 17, 20180229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hur, M.-H.; Hong, J.H.; Yeo, S. Effects of Aromatherapy on Stress, Fructosamine, Fatigue, and Sleep Quality in Prediabetic Middle-Aged Women: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2019, 31, 100978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, M.; Kashfi, L.S.; Mirmohamadkhani, M.; Ghods, A.A. The Effect of Aromatherapy with Peppermint Essential Oil on Anxiety of Cardiac Patients in Emergency Department: A Placebo-Controlled Study. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2022, 46, 101533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meşe, M.; Sarıtaş, S. Effects of Inhalation of Peppermint Oil after Lumbar Discectomy Surgery on Pain and Anxiety Levels of Patients: A Randomized Controlled Study. EXPLORE 2024, 20, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelan, U.S.; De Oliveira, A.C.; Cacoci, É.S.P.; Martins, T.E.A.; Giacon, V.M.; Velasco, M.V.R.; Lima, C.R.R.D.C. Potential Use of Essential Oils in Cosmetic and Dermatological Hair Products: A Review. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 1407–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council Directive 76/768/EEC of 27 July 1976 on the Approximation of the Laws of the Member States Relating to Cosmetic Products. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:31976L0768 (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Directive 2004/24/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 March 2004 Amending, as Regards Traditional Herbal Medicinal Products, Directive 2001/83/EC on the Community Code Relating to Medicinal Products for Human Use. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32004L0024 (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Cosmetics Regulation. Available online: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/sectors/cosmetics/legislation_en (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Quality of Essential Oils as Active Substances in Herbal Medicinal Products/Traditional Herbal Medicinal Products. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/quality-essential-oils-active-substances-herbal-medicinal-products-traditional-herbal-medicinal-products-scientific-guideline (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Tinctura Mentha. Available online: https://www.bda.bg/images/stories/documents/bdias/ss2883.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Huang, D.; Pei, C.; Li, S.; Wang, Z. Gelomyrtol for Acute or Chronic Sinusitis: A Protocol for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2020, 99, e20611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taw, M.B.; Nguyen, C.T.; Wang, M.B. Integrative Approach to Rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 55, 947–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anise Oil. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/herbal/anisi-aetheroleum (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Carmolis Oral Drops. Available online: https://www.bda.bg/images/stories/documents/bdias/2015-03-04-00830.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Gelomyrtol. Available online: https://www.bda.bg/images/stories/documents/bdias/2016-09-07-5608.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Gelomyrtol 120 Mg. Available online: https://www.bda.bg/images/stories/documents/bdias/2016-09-07-5607.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Levaxan. Available online: https://www.bda.bg/images/stories/documents/bdias/2024-09-10-135939.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Mucoplant. Available online: https://www.bda.bg/images/stories/documents/bdias/2024-01-15-133659.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Myrtol. Available online: https://www.bda.bg/images/stories/documents/bdias/2020-04-13-119118.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Tavipec 300 Mg. Available online: https://www.bda.bg/images/stories/documents/bdias/2024-11-04-136418.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Tavipec. Available online: https://www.bda.bg/images/stories/documents/bdias/2017-03-15-7915.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Gillissen, A.; Wittig, T.; Ehmen, M.; Krezdorn, H.; De Mey, C. A Multi-centre, Randomised, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Clinical Trial on the Efficacy and Tolerability of GeloMyrtol® forte in Acute Bronchitis. Drug Res. 2013, 63, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsebai, M.F.; Albalawi, M.A. Essential Oils and COVID-19. Molecules 2022, 27, 7893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kongkaew, C.; Sakunrag, I.; Chaiyakunapruk, N.; Tawatsin, A. Effectiveness of Citronella Preparations in Preventing Mosquito Bites: Systematic Review of Controlled Laboratory Experimental Studies. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2011, 16, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osimitz, T.G.; Murphy, J.V. Neurological Effects Associated with Use of the Insect Repellent N,N-Diethyl-m-Toluamide (DEET). J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 1997, 35, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swale, D.R.; Bloomquist, J.R. Is DEET a Dangerous Neurotoxicant? Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 2068–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adorjan, B.; Buchbauer, G. Biological Properties of Essential Oils: An Updated Review. Flavour Fragr. J. 2010, 25, 407–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerio, L.S.; Olivero-Verbel, J.; Stashenko, E. Repellent Activity of Essential Oils: A Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.Y. Essential Oils as Repellents against Arthropods. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 6860271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Rao, R.; Kumar, S.; Mahant, S.; Khatkar, S. Therapeutic Potential of Citronella Essential Oil: A Review. Curr. Drug Discov. Technol. 2019, 16, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Shakya, S.; Verma, M.; Prabahar, A.E.; Pallathadka, H.; Verma, A.K. Mosquito Repellents Derived from Plants. Int. J. Mosq. Res. 2023, 10, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samada, L.H.; Tambunan, U.S.F. Biopesticides as Promising Alternatives to Chemical Pesticides: A Review of Their Current and Future Status. OnLine J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 20, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellappandian, M.; Vasantha-Srinivasan, P.; Senthil-Nathan, S.; Karthi, S.; Thanigaivel, A.; Ponsankar, A.; Kalaivani, K.; Hunter, W.B. Botanical Essential Oils and Uses as Mosquitocides and Repellents against Dengue. Environ. Int. 2018, 113, 214–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adişen, E.; Önder, M. Allergic Contact Dermatitis from Laurus Nobilis Oil Induced by Massage. Contact Dermat. 2007, 56, 360–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiadis, G.I.; Pfab, F.; Klein, A.; Braun-Falco, M.; Ring, J.; Ollert, M. Erythema Multiforme Due to Contact with Laurel Oil. Contact Dermat. 2007, 57, 116–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleasel, N.; Tate, B.; Rademaker, M. Allergic Contact Dermatitis Following Exposure to Essential Oils. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2002, 43, 211–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, Q. A Study on the Knowledge and Use of Essential Oil by People of Different Age-Focused on Women in Zhejiang, China. J. Korea Soc. Comput. Inf. 2011, 26, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askeur, Y.; Adil, S.; Kamel, D. Use of Aromatherapy for Migraine Pain Relief. Curr. Perspect. Med. Aromat. Plants 2024, 7, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).