1. Introduction

With the advent of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, the global manufacturing industry is rapidly shifting toward intelligence and digitalization. Consequently, the smart factory has emerged as a new paradigm in manufacturing. A smart factory is an intelligent manufacturing system that integrates the entire production process—from product planning and design, through manufacturing and operations, to distribution and sales—by leveraging information and communication technology (ICT). This integration enables the production of customer-tailored products at minimal cost and in less time. Importantly, such systems distinguish themselves by pursuing a human-centered, convergent, and advanced manufacturing environment, rather than relying solely on technology-driven automation [

1]. Thus, smart factories play a pivotal role in securing sustainable competitiveness in manufacturing by fostering a digitally based, innovative production environment through the convergence of ICT and manufacturing technologies.

As a core strategy for the digital transformation and intelligentization of manufacturing, smart factory policy has been positioned as a major government-led industrial initiative over the past decade. Since 2014, the Ministry of SMEs and Startups has actively promoted the Smart Factory Construction Support Project as a key instrument to enhance the productivity and competitiveness of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) as well as mid-sized firms. This initiative has yielded remarkable quantitative outcomes, including the establishment of more than 35,000 smart factories by 2024 [

2]. Government support for smart factories is expected to continue. In 2024, the Ministry plans to invest KRW 219.1 billion in smart manufacturing innovation, with smart factories at its core, and in 2025, it will support 791 additional smart factory projects [

3].

However, despite the expansion of these smart factory policies, systematic performance analysis regarding the effectiveness of policy support and its economic impact remains relatively inadequate. Consequently, securing foundational data to quantitatively and empirically analyze policy outcomes and link them to policy feedback is urgently needed. Particularly, as the cumulative number of recipient firms expands, the performance management system must also be operated in a more sophisticated and reliable manner. Furthermore, as interest in return on investment (ROI) grows, the need for economic effectiveness analysis is also increasing.

This study aims to systematically analyze the actual effectiveness of the Smart Factory Construction Support Project and, based on this, provide foundational data for future policy formulation and institutional improvements. To this end, it analyzes changes in economic performance, focusing on firms that completed smart factory construction in 2019 and 2020. This paper particularly focuses on analyzing the causality of economic outcomes. Specifically, it examines whether government support for the smart factory initiative actually had an effect on sales revenue for firms that completed smart factory implementation. Smart factory construction primarily streamlines management and improves efficiency from a production operations perspective, and therefore may not directly lead to an increase in sales. However, this paper argues that smart factory implementation facilitates quality improvement and cost reduction, enhancing a company’s overall competitiveness, and ultimately contributing to increased sales. Furthermore, since constructing smart factories involves significant costs and poses challenges for SMEs to implement independently, the government has provided subsidies to support their adoption. This paper aims to evaluate the effectiveness of the project.

To rigorously verify the causal effectiveness of the outcomes, a propensity score matching (PSM) method was employed to conduct a comparative analysis with non-recipient firms. This approach sets non-recipient firms with similar characteristics (sales scale, industry, business tenure, etc.) as the control group. By estimating the counterfactual performance that would have occurred if the firms had not participated in the smart factory project, the method aims to quantitatively identify the pure policy effect of the initiative.

2. Related Works

2.1. Previous Research on the Effects of Smart Factory Adoption

Smart factories have emerged as a key strategy for enhancing manufacturing competitiveness, and related research has become increasingly active in recent years. However, while studies on process automation technologies such as robotics are relatively abundant, empirical research directly analyzing the effects of smart factory adoption remains limited. For example, Dauth et al. (2021) found that robot adoption in German manufacturing firms reduced manufacturing employment [

4], whereas Koch et al. (2021) reported that Spanish firms adopting robots employed approximately 10% more workers than their non-adopting counterparts [

5]. Similarly, Wang et al. (2021) argued that robots stimulate labor demand for highly skilled and educated workers by enhancing firm productivity [

6].

In contrast, since smart factory adoption is a relatively recent trend, empirical studies on its effects remain scarce. Sufian et al. (2019) observed that Industry 4.0 technologies, including smart factories, can generate positive impacts not only on operational performance (e.g., productivity gains and process automation) but also on managerial outcomes (e.g., cost reduction and ROI improvement) [

7]. In Korea, Seo and Kim (2022) found that firms adopting smart factories experienced, on average, a 35.2% increase in employment within two years of adoption, which they interpreted as a job re-creation effect [

8]. Furthermore, Kim and Park (2022) compared SMEs that adopted smart factories with those that did not, employing PSM to analyze firm-level outcomes in terms of total assets, employment, and sales revenue [

9]. Their results indicated that total assets increased most significantly in the year of adoption, with the effect gradually diminishing but remaining statistically significant. By contrast, the employment effect strengthened over time, while no significant positive effect on sales revenue was identified. These findings are noteworthy, given that the present study evaluates the effectiveness of government smart factory policy by examining the sales growth of recipient firms. However, the key distinction lies in the unit of analysis: while they focused on firms that voluntarily adopted smart factories [

9], this study examines firms that specifically received government support. Consequently, the estimated effect on sales growth is expected to differ.

In summary, although recent research has begun to investigate the effects of smart factories, empirical studies that apply causal inference frameworks to evaluate government support policies remain limited. This study contributes to the literature by employing a PSM-based empirical design to estimate the average treatment effect (ATE) of smart factory policies, thereby addressing issues of selection bias and providing more credible evidence of causal impacts.

2.2. Related Research on Causal Inference

In contexts where randomized controlled trial (RCT) is infeasible or constrained, causal inference provides a set of methodologies to identify and estimate the effects of interventions using observational data. Broadly, causal inference frameworks can be categorized into two major strands: Rubin’s causal model (RCM) [

10], which defines causal effects by contrasting potential outcomes under alternative treatment states, and Pearl’s causal diagrams [

11], which represent qualitative causal structures through directed acyclic graphs, where nodes denote variables and arrows indicate direct causal relationships.

The fundamental goal of causal inference is to estimate the change in an outcome that would occur when a treatment is applied. Ideally, this is achieved through the random assignment of experimental and control groups, enabling unbiased comparisons of outcomes. However, in most real-world settings, randomization is costly, time-consuming, or ethically infeasible. Consequently, causal effects must often be estimated from non-experimental (observational) data. Causal inference thus provides methodological tools to approximate causal relationships under such conditions.

The standard notation is as follows: treatment is denoted by (with indicating the treated group and the control group); the observed outcome is ; covariates are represented by ; and the potential outcomes are denoted by and . The expectation operator refers to the expected value with respect to the data-generating process.

According to Rubin’s causal model, causal effects are defined in terms of potential outcomes under different treatment states. For an individual

, the potential outcome under treatment is

, and the potential outcome under no treatment is

. The observed outcome can thus be written as:

The ATE, which is the primary estimand of causal inference, is defined as:

To identify the ATE from observational data, several key assumptions must be satisfied: consistency, the stable unit treatment value assumption (SUTVA), ignorability, and positivity [

12].

Consistency requires congruence between the assigned treatment and the observed outcome; that is, there should be no hidden or undefined treatments.

SUTVA stipulates that the treatment status of one unit does not influence the potential outcomes of other units, ensuring independence across units.

Ignorability (unconfoundedness) requires that, conditional on covariates

, treatment assignment is independent of the potential outcomes:

This implies that, after conditioning on observed covariates, treatment assignment can be considered as-if random.

Positivity (overlap) requires that the conditional probability of receiving treatment, given covariates, is strictly positive. This prevents estimation instability by ensuring sufficient overlap between treated and control groups and avoiding extrapolation outside the common support.

Violations of these assumptions often arise from confounding variables, which simultaneously affect both treatment assignment and outcomes. The presence of confounders can severely bias estimates of treatment effects. A well-known illustration is Simpson’s paradox, where the aggregated effect of treatment can differ substantially—and even reverse direction—from subgroup-specific effects [

13]. Another important source of bias is selection bias, in which confounding factors influence individuals’ treatment choices, thereby distorting the estimated causal effect.

Yao et al. (2021) proposed seven major causal inference methodologies to address these challenges [

12]. The first is re-weighting methods, which use balancing scores to adjust outcomes such that the treated and control groups become statistically exchangeable [

14]. The second is stratification methods, which reduce bias by partitioning the population into strata based on confounders and then comparing treated and control units within each stratum [

15]. The third is matching methods, which estimate counterfactual outcomes for treated and control groups by pairing each unit with its most similar counterpart [

16]. By matching observable characteristics, bias from confounders can be mitigated. In this context, propensity scores are often used to compute the distance between subjects during the matching process [

17]. Propensity scores summarize the influence of covariates on treatment assignment, thereby reducing the curse of dimensionality and facilitating efficient matching. In addition to these three approaches, methods such as tree-based models, representation learning, multi-task learning, and meta-learning have also been developed to address causal inference problems [

12]. Causal inference techniques are now widely applied across diverse domains, including advertising, recommendation systems, medicine, education, and political science.

2.3. Propensity Score Matching (PSM)

A propensity score is defined as the conditional probability that an individual receives treatment given their observed characteristics [

14]. PSM is a widely used procedure to reduce covariate imbalance between treatment and control groups in non-randomized settings, thereby enabling credible comparisons of counterfactual outcomes. In essence, PSM adjusts the treatment and control groups to approximate the conditions of random assignment. It relies on the balancing property, which states that if two units share the same propensity score, the distribution of their observed covariates will also be balanced [

14].

The general procedure of PSM is as follows:

Estimate propensity scores using a classification algorithm, such as logistic regression, based on observed covariates.

Apply a matching algorithm (e.g., nearest-neighbor matching) to pair treated and control units, thereby reconstructing groups or reweighting observations to ensure comparability.

Use the matched sample to estimate causal effects (e.g., ATE or ATT (ATE on the treated)) and analyze the results.

Conduct balance diagnostics to verify whether the matching procedure has adequately approximated random assignment [

18].

PSM has long been recognized as a crucial methodology for causal inference across various disciplines. Dehejia and Wahba (2002), for instance, showed that by matching the treatment group from the National Supported Work (NSW) experiment to non-experimental comparison groups from the Current Population Survey (CPS) and the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), PSM could recover treatment effect estimates (ATE/ATT) that closely approximated experimental benchmarks, even with observational data [

19]. Similarly, Lindenauer et al. (2004) demonstrated the effectiveness of PSM in comparative effectiveness research by applying it to a large-scale cohort of more than 780,000 patients across 329 hospitals [

20]. Beyond healthcare, PSM has also been applied in marketing: Bakhtiari et al. (2013) used it to adjust credit card customer data and estimate the causal effect of affinity card ownership, finding—contrary to conventional assumptions—that affinity card holders were not more profitable than non-owners [

21].

2.4. Current Status of Causal Inference Research for Public Policy

Yao et al. (2021) identified policy decision-making as a major application area of causal inference, alongside domains such as advertising, recommendation systems, and pharmaceuticals [

12]. A representative dataset in this field is the Infant Health and Development Program (IHDP) introduced by Hill (2011) [

22]. The IHDP dataset is a semi-simulated dataset designed to examine the impact of high-quality child care on children’s cognitive test scores. Based on this dataset, numerous studies have explored alternative causal inference methodologies for policy-related decision-making. For instance, Johansson et al. (2016) developed a deep learning–based causal inference algorithm that outperformed existing state-of-the-art methods [

23]. Similarly, Schwab et al. (2018) proposed the Perfect Match (PM) methodology, a neural network–based approach for counterfactual inference that augments propensity score–matched nearest neighbors to expand the treated sample [

24]. Yao et al. (2018) introduced the Similarity-preserved Individual Treatment Effect (SITE) estimation method, which improves performance by balancing imbalanced data distributions using local similarity, thereby differing from prior approaches [

25].

Blankshain and Stigler (2020) offered guidelines for applying causal inference in policy analysis, presenting a six-step framework to support policymaker decision-making, with applications in areas such as national security [

26]. Welfare policy represents one of the most significant domains for causal inference applications. For example, Finkelstein and Hendren (2020) proposed a framework to evaluate government policy impacts on net spending using causal inference, introducing the concept of the marginal value of public funds [

27]. This measure has since been applied across fields such as public finance, labor, and trade. Similarly, in public health, Glass et al. (2013) argued that a causal inference framework enables the design of more effective health policies and fosters greater public trust [

28].

More recent studies have applied causal inference to analyze COVID-19 policies. Zhu et al. (2025) investigated the effects of lockdown measures on personal computer usage, employing panel data techniques such as difference-in-differences (DiD) and synthetic control [

29]. Their findings demonstrated that such policies significantly influenced both the volume and intensity of computer use.

Causal inference has also benefited from advances in machine learning. Athey (2015) showed that supervised machine learning, traditionally used for prediction, can also serve as an effective tool for causal inference in policy evaluation [

30]. Extending this line of research, Kreif and Diaz-Ordaz (2019) examined balance between treated and control groups, demonstrating that machine learning can assist in variable selection and improve propensity score modeling in high-dimensional settings [

31].

In the field of education policy, Cordero et al. (2018) applied causal inference methods such as DiD and PSM to assess the impact of education reforms, moving beyond correlation-based analyses to establish more precise causal relationships [

32]. Weissman (2021) narrowed the scope further to physics education, applying causal inference to recommend more robust education policies and highlighting the limitations of policy approaches based solely on associations [

33].

3. Research Methodology and Data Preparation

3.1. Overview of the Smart Factory Construction Support Project and Research Questions

As noted in the introduction, the Korean government has promoted smart factory policies since 2014 to foster manufacturing innovation in the era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Reviewing implementation progress, by the end of 2022 a total of 30,144 smart factory projects had been carried out. However, both budget allocations and implementation slowed in 2023 and 2024, with the cumulative number reaching 35,282 factories by 2024. Government support is nevertheless expected to increase again in the future [

2].

Smart factories are regarded as a cornerstone of digital transformation and as a critical government initiative to promote collaboration between the public and private sectors, particularly in driving innovation among SMEs. Yet, as emphasized earlier, systematic performance analyses of the effectiveness and economic impact of smart factory policies remain relatively insufficient. Accordingly, there is a pressing need for empirical research that quantitatively evaluates policy outcomes and integrates them into the policy feedback loop.

This study seeks to systematically assess the effectiveness of the Smart Factory Construction Support Project and to provide empirical evidence that can inform future policy design and institutional improvements. Government subsidies support manufacturing SMEs in achieving digital transformation and overcoming resource constraints [

34]; however, their effectiveness has not been clearly demonstrated. Specifically, this study analyzes changes in firms’ economic performance, focusing on companies that completed smart factory construction in 2019 and 2020. The analysis emphasizes causal inference, investigating whether government support for smart factory initiatives generated measurable improvements in sales performance among participating firms.

3.2. Necessity and Expected Effects of PSM Analysis

To rigorously evaluate the outcomes of the Smart Factory Construction Support Project, it is necessary to systematically compare the financial performance of participating firms with that of non-participating firms. In particular, assessing whether smart factory construction generated measurable improvements in quantitative outcomes—such as sales growth—is crucial for validating the policy’s effectiveness.

However, a simple comparison of recipient and non-recipient firms risks severe selection bias, as it fails to account for differences in firm characteristics (e.g., size, tenure, industry). For instance, recipient firms may inherently possess higher growth potential, which could lead to an overestimation of the policy’s effect if left uncontrolled. Conversely, firms may have applied for government support precisely because they were experiencing difficulties, in which case their performance might be underestimated relative to non-recipient firms. In either scenario, a naïve comparison is likely to produce biased or misleading estimates of the policy’s net effect.

While an RCT would provide the most reliable identification strategy, such an approach is infeasible in real-world policy contexts. Consequently, analyses based on observational data must employ statistical techniques capable of adjusting for confounding variables such as firm characteristics.

PSM offers a powerful quasi-experimental method for causal estimation in non-experimental settings. By estimating each firm’s propensity score—the conditional probability of receiving smart factory support given observed covariates—and matching recipient firms with non-recipients of similar characteristics, PSM reduces confounding bias and approximates the conditions of random assignment.

After matching, the treated group (recipient firms) and the control group (non-recipient firms) can be regarded as comparable groups, differing only in their receipt of government support. This facilitates estimation of the policy’s causal effect, isolating the treatment effect attributable to the smart factory initiative.

3.3. PSM Analysis Procedure and Components

This study employed the PSM technique to analyze the policy effects of the Smart Factory Construction Support Project. The analysis followed five main steps:

Data preprocessing: Raw data were cleaned and restructured into a format suitable for analysis. Missing or incomplete observations were removed, annual data were aggregated at the firm level, and information on recipient and non-recipient firms was merged to construct a comparable dataset.

Variable construction: Key dependent variables for performance measurement, such as sales growth rate and compound annual growth rate (CAGR), were calculated. Potential confounding variables capturing firm characteristics (e.g., age, industry, sales scale) were generated or transformed as needed. Outlier removal criteria were established, and extreme observations were excluded to enhance the validity and robustness of the analysis.

Pre-PSM effect analysis: Before matching, the average sales growth rate and CAGR were compared between recipient and non-recipient firms, and the ATE was preliminarily estimated. Recipient firms were classified as the treated group and non-recipient firms as the control group. Statistical significance was assessed using t-tests. This step served both to identify baseline differences between groups and to provide a benchmark for comparison with post-PSM results.

PSM implementation: Propensity scores were estimated to predict each firm’s likelihood of receiving support, using machine learning techniques. One-to-one or nearest-neighbor matching was then applied to pair recipient firms with non-recipients of similar propensity scores, thereby forming balanced treated and control groups.

Post-PSM effect analysis: After matching, policy effects were estimated by comparing outcomes between the matched groups. Differences in post-matching sales growth rate and CAGR were analyzed, and t-tests were conducted to quantitatively assess the impact of smart factory support.

Through this multi-stage procedure, the study seeks to evaluate the program’s effectiveness under conditions that approximate random assignment. Compared with simple comparison methods, the use of PSM is expected to yield more credible estimates of the policy’s net causal effect.

3.4. Data Preprocessing

Data preprocessing for the empirical analysis was conducted on both recipient and non-recipient firms, separated by support year, following three main steps: removal of missing values, transformation of annual sales data, and outlier removal.

In the missing value removal stage, records lacking essential variables required for analysis were discarded. During the data transformation and merging stage, sales revenue data were restructured from an annual format into a firm-specific time-series format. For the 2019 recipient firms and their matched non-recipient counterparts, the dataset was constructed using four years of sales revenue data (2018–2021), thereby covering pre- and post-treatment periods (t − 1, t, t + 1, t + 2). In contrast, for the 2020 recipient firms and corresponding non-recipient firms, the dataset consisted of three years of sales revenue data (2019–2021), enabling comparative analysis across the time points t − 1, t, and t + 1.

3.5. Variable Construction

To empirically analyze the policy effects of the Smart Factory Construction Support Program, both outcome variables and control variables were defined, and additional data cleaning procedures were conducted. Two financial performance indicators—sales growth rate and CAGR—were employed as outcome variables to capture quantitative policy effects.

The sales growth rate was calculated as follows:

CAGR, which measures the average growth rate over the entire analysis period, was calculated using the following formula:

Before generating these outcome variables, firms with zero or negative sales in the initial or final year were excluded to prevent computational errors in the calculation of sales growth rate and CAGR. For recipient firms in 2019, sales growth rates were computed for the years 2019, 2020, and 2021, while CAGR was calculated over the period 2018–2021. For 2020 recipient firms, sales growth rates were computed for 2020 and 2021, and CAGR was calculated over the period 2019–2021. After constructing these outcome variables, outliers in the sales growth rate distribution were removed using the interquartile range (IQR) method.

Following this refinement process, the final dataset included 1868 cases for 2019 recipient firms and 2554 cases for 2020 recipient firms. For non-recipient firms in the control group, which refer to companies that do not receive the government subsidies, the sample size decreased from 239,487 to 145,467 for the 2019 cohort and to 150,933 for the 2020 cohort after preprocessing.

In addition, three confounding variables were defined to control for heterogeneity that could influence both treatment assignment and financial performance:

Base-year sales: measured as sales in the year immediately preceding support (e.g., 2018 sales for firms supported in 2019). This variable captures firm size and financial capacity.

Years in operation: calculated by converting the firm’s founding year into its age at the time of support. Older firms are typically more stable, making this a potential confounder.

Industry code: medium-level industry codes were one-hot encoded into 74 binary variables to control for industry heterogeneity.

In this study, we assume the ignorability condition holds conditional on key pre-treatment covariates—base-year sales, years in operation, and industry sector. These variables capture firms’ initial scale, managerial experience, and structural characteristics that jointly influence both the likelihood of receiving government support and subsequent performance outcomes. By conditioning on these covariates, we aim to mitigate potential selection bias arising from non-random program participation. This allows the treatment assignment to approximate randomization, thereby enabling a more credible estimation of the causal effect of government support on firm performance. If unobserved confounders affect both the likelihood of receiving government support and firm performance, the ignorability assumption may be violated, leading to biased estimates of the treatment effect. This is a common risk shared by most causal inference studies.

4. PSM Results and Discussion

To accurately assess the policy effects using PSM, we first compared the treated and control groups and estimated causal effects prior to PSM implementation. These results were then contrasted with the post-PSM estimates, allowing us to evaluate how PSM alters the estimation of causal relationships.

4.1. Association Analysis Before PSM

Before conducting the PSM analysis, a preliminary comparison was performed to examine differences in policy outcomes between firms that participated in the Smart Factory Construction Support Project (recipient firms) and those that did not (non-recipient firms). Specifically, we compared annual average performance measures and estimated the ATE based on sales growth rate and CAGR.

4.1.1. Recipient Firms vs. Non-Recipient Firms in 2019 (Pre-PSM)

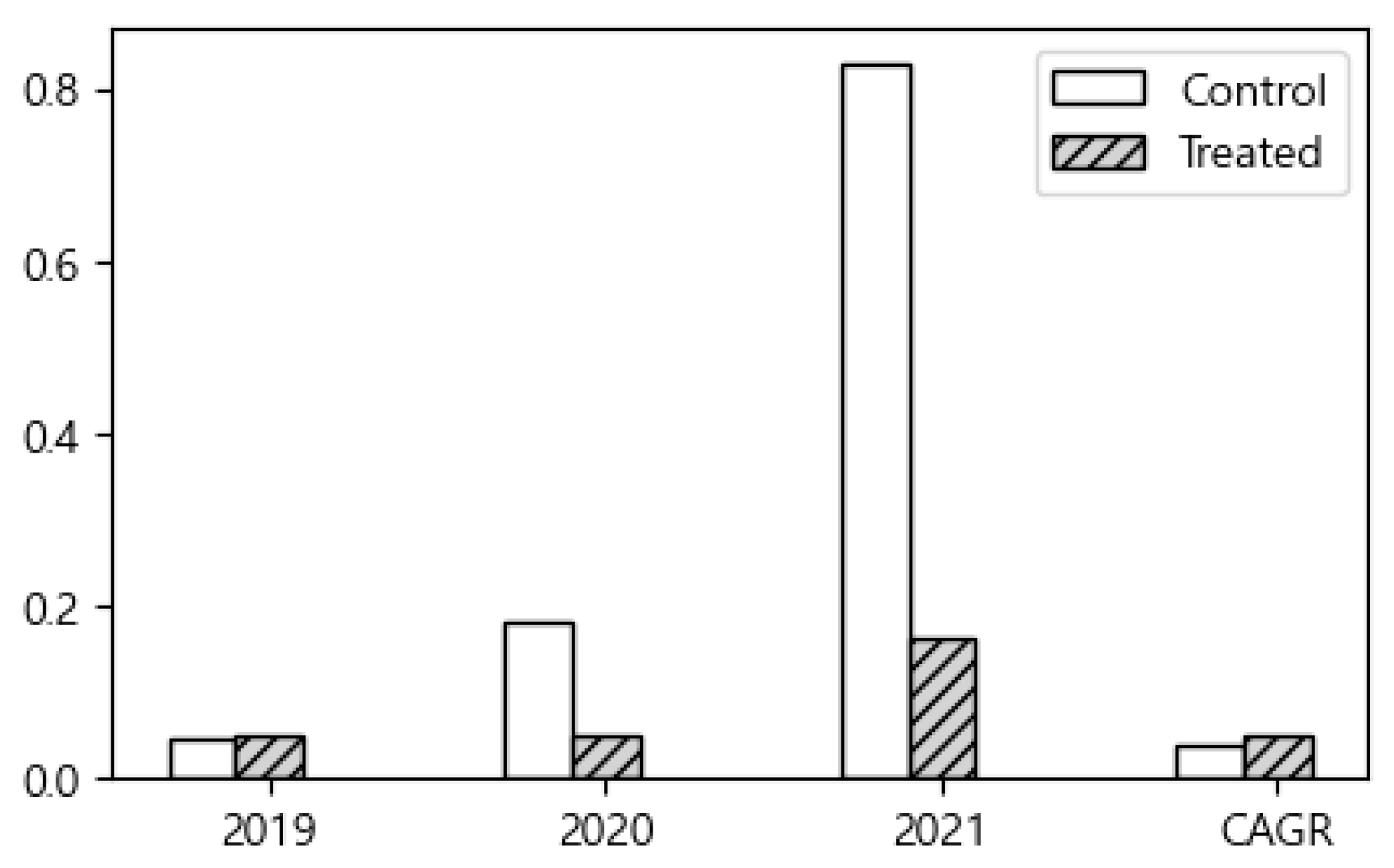

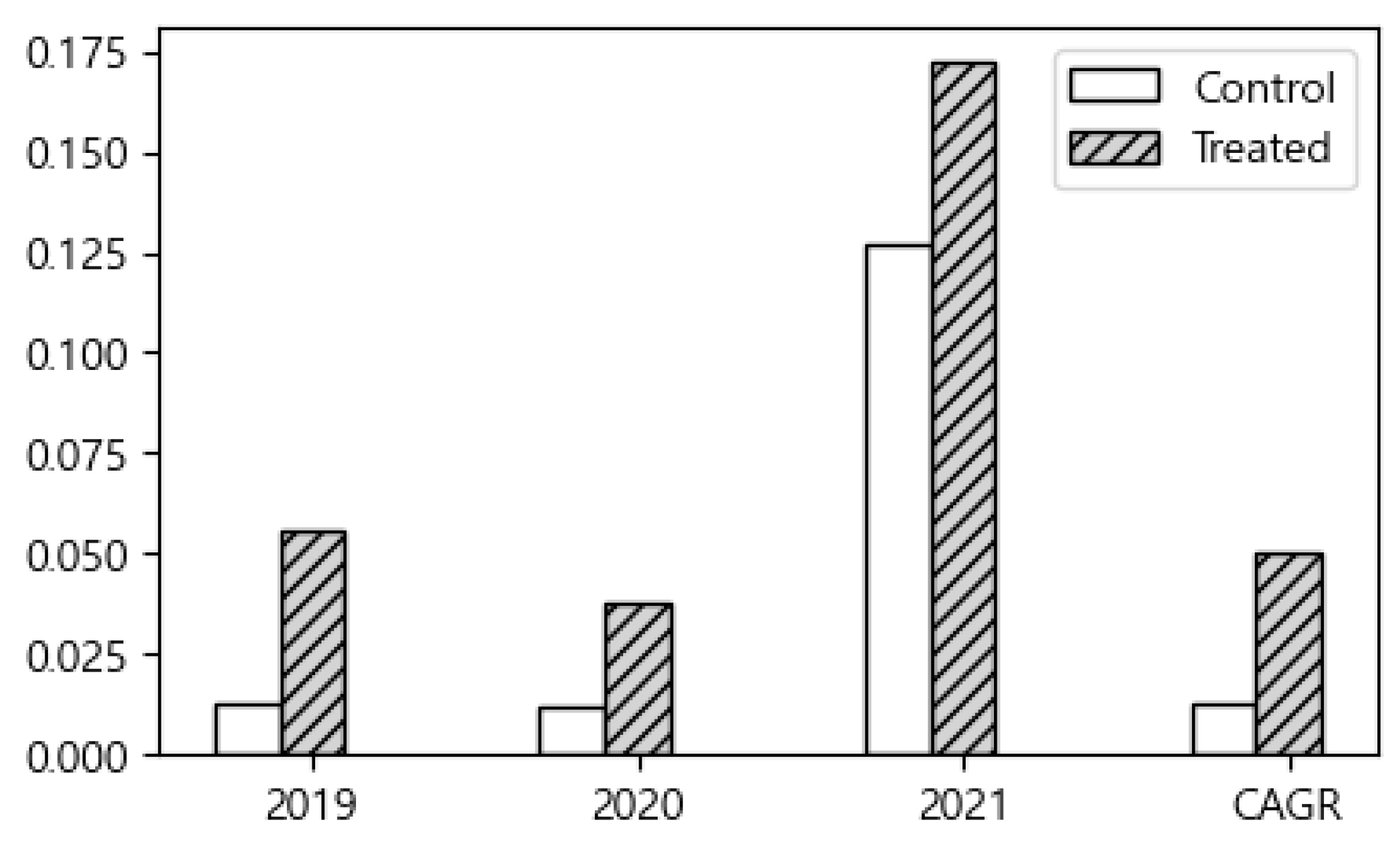

As shown in

Figure 1, recipient firms exhibited slightly higher sales growth rates and CAGRs than non-recipient firms in 2019. However, in the subsequent years (2020 and 2021), non-recipient firms demonstrated relatively higher sales growth rates.

Table 1 presents the ATE estimates, calculated as the difference in outcome variables between recipient and non-recipient firms, together with the corresponding

t-test results for differences between the treated and control groups. Although the figure suggests that non-recipient firms had a notably higher sales growth rate than recipient firms in 2021, the

p-value of 0.883 indicates that the difference is not statistically significant.

These results suggest that, for the 2019 cohort, the impact of smart factory implementation on financial performance was not clearly evident in the pre-analysis, highlighting the need for more rigorous comparative methods.

4.1.2. Recipient Firms vs. Non-Recipient Firms in 2020 (Pre-PSM)

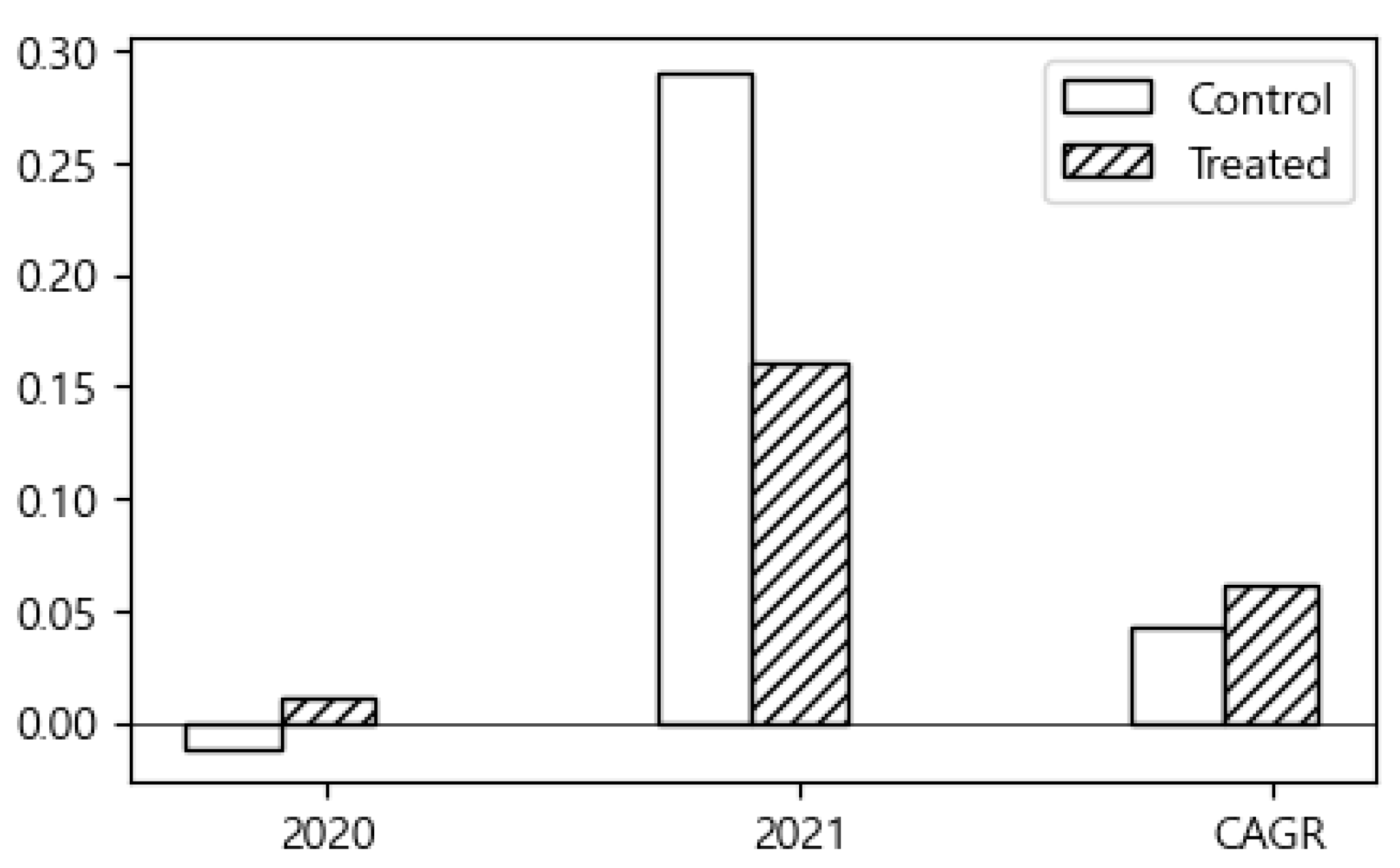

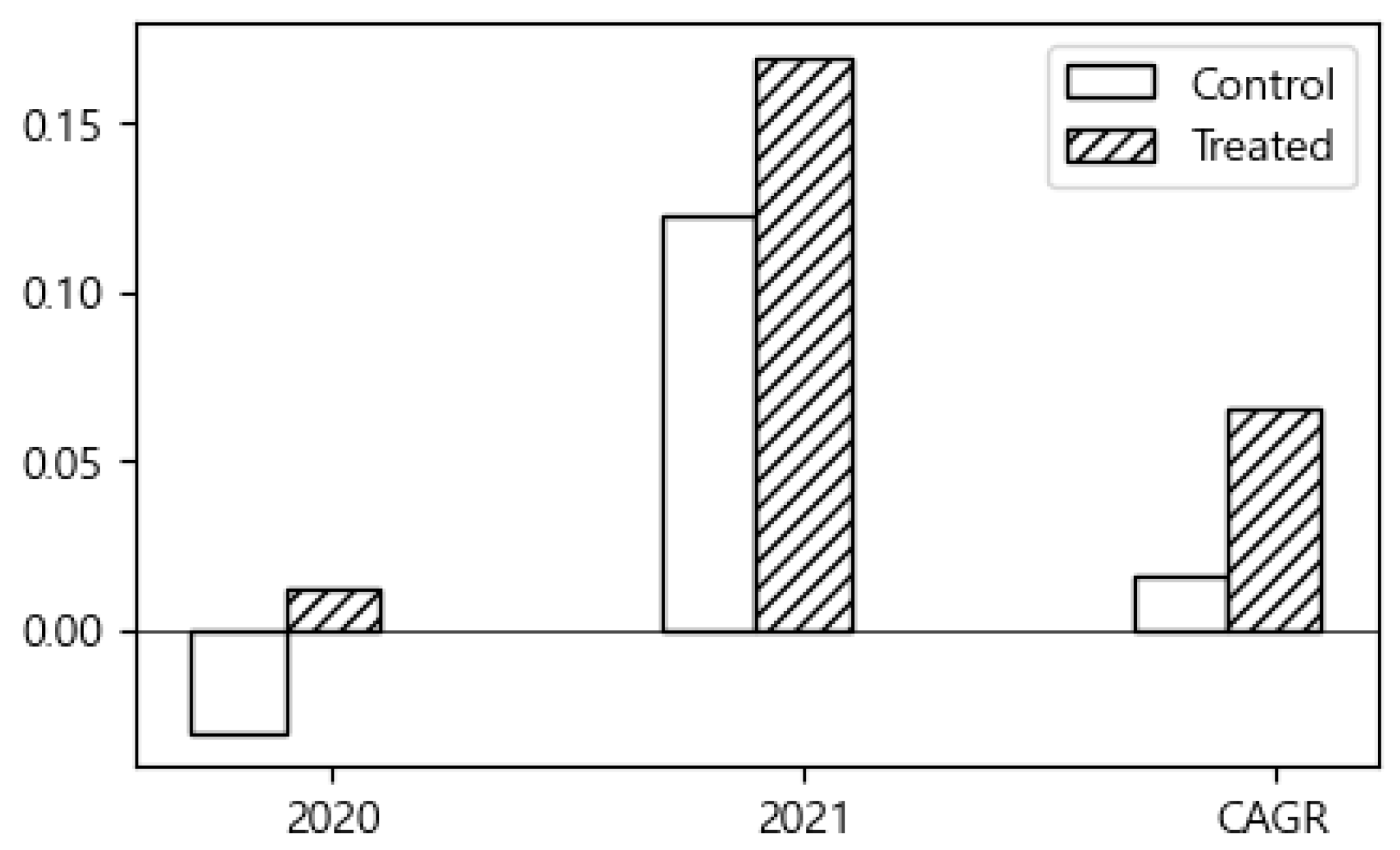

As illustrated in

Figure 2, recipient firms outperformed non-recipient firms in both sales growth rate and CAGR in 2020. However, in 2021, non-recipient firms exhibited higher sales growth rates.

Table 2 reports the estimated ATE results for the 2020 support program. Although the graph shows that non-recipient firms had higher sales growth rates than recipient firms in 2021, the difference was not statistically significant. Accordingly, it is difficult to conclude that a clear support effect was present in that year. By contrast, both the 2020 average annual sales growth rate and CAGR demonstrated statistically significant support effects at the 1% level. Nevertheless, with ATE values of only 2.25% and 1.9%, respectively, the magnitude of the effect cannot be considered substantial.

These results indicate that firms receiving support in 2020 experienced statistically significant improvements in short-term sales growth and average annual growth rate, suggesting the presence of a potential policy effect. However, given that the estimated ATE values were relatively small (2.25% and 1.9%, respectively), it is difficult to argue that the effect was commensurate with the level of government support. This pre-analysis thus underscores the necessity of more rigorous causal inference. Serving as baseline evidence, these results will later be compared with post-PSM estimates, where endogeneity and selection bias are more systematically addressed, enabling a more credible evaluation of policy effectiveness.

4.2. PSM Implementation Procedure and Matching Results

The implementation of PSM consisted of two stages. The first involved estimating propensity scores for both recipient and non-recipient firms. The second involved matching firms across groups based on these scores.

4.2.1. Propensity Score Estimation

The propensity score represents the conditional probability of a firm receiving smart factory support and provides a quantitative benchmark for comparing the characteristics of the treated group (recipient firms) and the control group (non-recipient firms). Since treatment assignment was influenced by confounding variables—namely, year of establishment, base-year sales, and industry sector—the propensity score can be interpreted as a single index summarizing these characteristics. To derive this score, a classification model was trained with the confounding variables as independent variables and support status as the dependent variable.

While logistic regression has been widely used in prior studies, in this analysis it failed to produce sufficiently reliable propensity score predictions due to an extremely low F1-score. To address this limitation and enhance predictive performance, a gradient boosting algorithm was adopted as an alternative.

Table 3 presents the performance comparison between logistic regression and gradient boosting at the default threshold of 0.5.

A critical challenge in propensity score estimation was the extreme class imbalance between recipient and non-recipient firms. For the 2019 data, after preprocessing, the sample included 1868 recipient firms compared to 145,467 non-recipient firms—a ratio of approximately 1:78. In such imbalanced contexts, accuracy is not an appropriate evaluation metric. Indeed, although accuracy rates were similar for logistic regression and gradient boosting, the F1-score for gradient boosting was 217 times higher, highlighting its superior performance in handling imbalanced data.

Table 4 presents the performance metrics after adjusting thresholds to maximize the F1-score. Although logistic regression improved marginally, its F1-score remained far below acceptable levels, confirming its inadequacy for propensity score estimation. Gradient boosting, however, consistently outperformed logistic regression, yielding substantially higher F1-scores (41.15% for 2019 and 35.38% for 2020).

Based on these results, this study adopted the gradient boosting algorithm for estimating propensity scores, as it provided substantially more reliable and discriminative performance than logistic regression under severe class imbalance conditions.

4.2.2. Inter-Group Matching and Suitability Verification

Using the estimated propensity scores, each recipient firm was matched with a non-recipient firm exhibiting the most similar score. Matching was conducted using the 1:1 nearest-neighbor method, with cases excluded if no sufficiently similar counterpart was available. This strategy was designed to minimize the influence of confounding variables and to ensure conditional comparability between the treated and control groups.

Several approaches are available for utilizing propensity scores. For instance, Inverse Probability Weighting (IPW) can be applied by weighting outcome values in proportion to the propensity scores, thereby rebalancing the groups. However, given the substantial imbalance between recipient and non-recipient firms in this study, 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching was selected as the most appropriate method to directly equalize group sizes and address data imbalance.

The matching results were as follows:

2019 cohort: Among 1868 recipient firms, 1358 were successfully matched, resulting in a combined dataset of 2716 firms across the treated and control groups.

2020 cohort: Among 2554 recipient firms, 1617 were successfully matched, yielding a combined dataset of 3234 firms across the two groups.

4.2.3. Visual Verification of Propensity Score Distribution

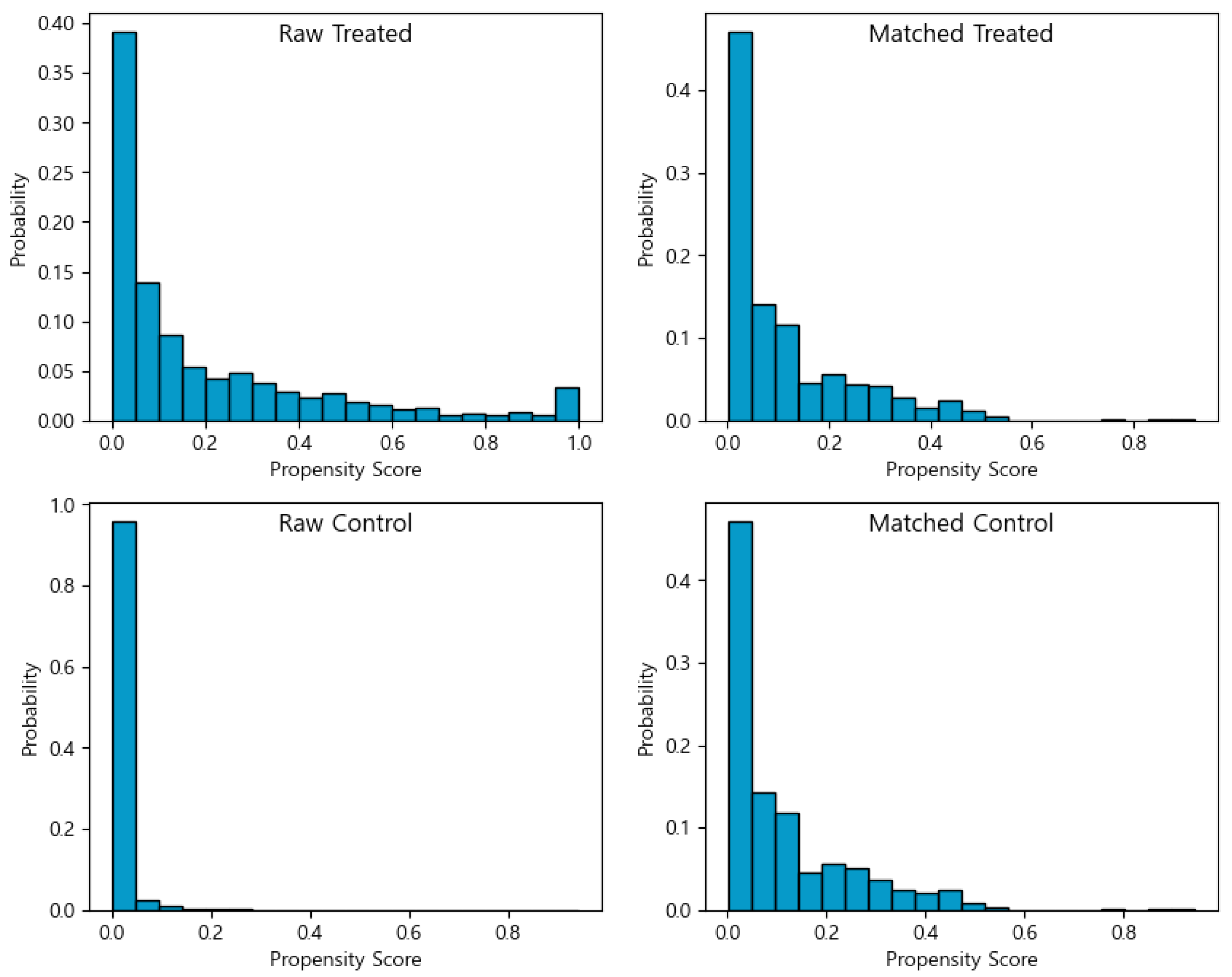

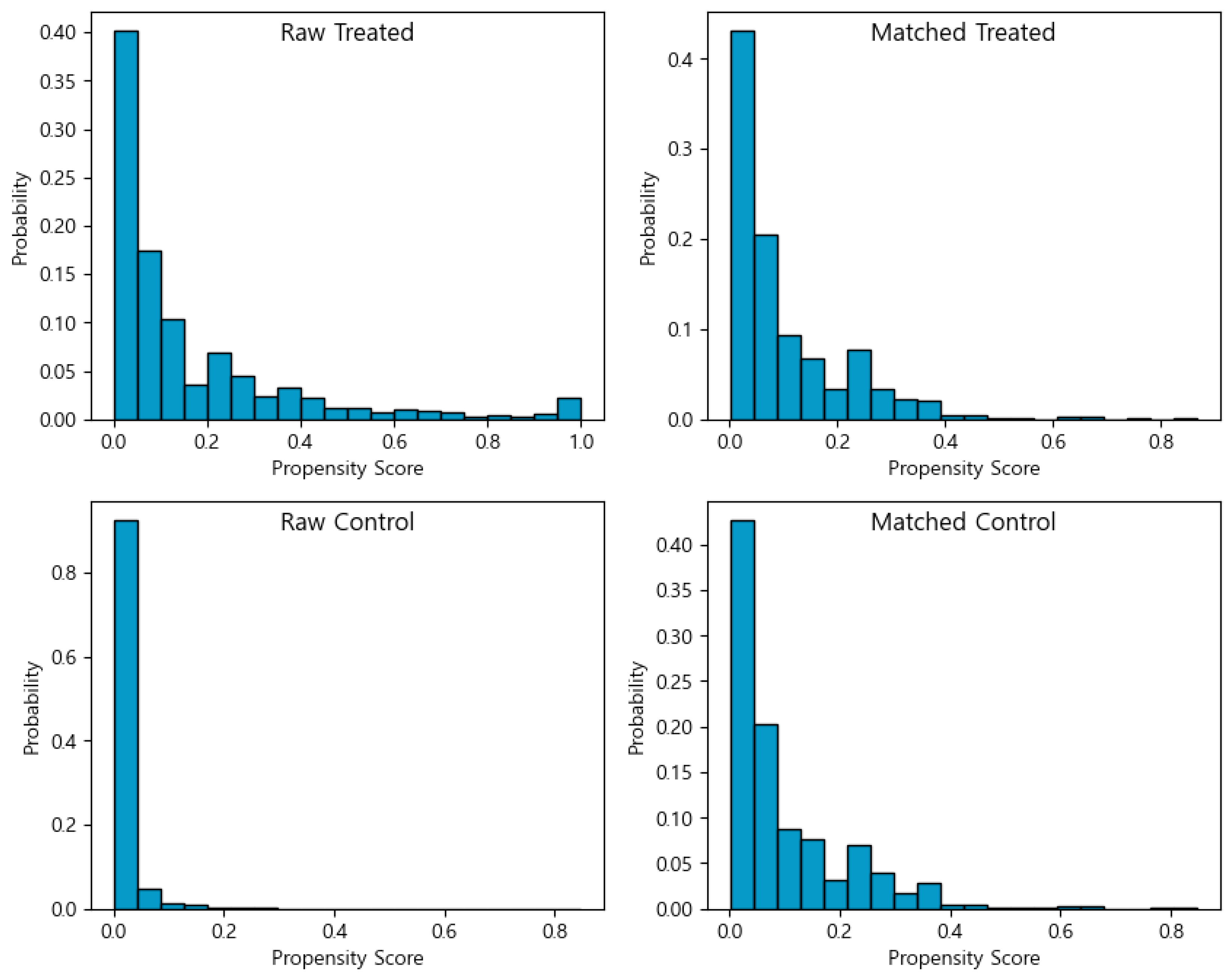

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 present the propensity score distributions of recipient (treated) and non-recipient (control) firms before and after matching for the 2019 and 2020 cohorts, respectively. In these figures, “Raw Treated” and “Raw Control” denote the distributions of treated and control firms prior to matching, while “Matched Treated” and “Matched Control” indicate the corresponding distributions after matching.

As shown in both figures, a clear imbalance existed between the treated and control groups prior to matching. However, following PSM, the two groups exhibit highly similar propensity score distributions. Since the propensity score represents the joint influence of observed confounding variables, the similarity of the post-matching distributions suggests that the confounding influence was successfully balanced across the groups. In other words, the effect of confounding variables on treatment assignment was effectively mitigated, thereby improving the validity of subsequent causal effect estimation.

4.3. Causal Analysis After PSM

After ensuring comparability between the control group (non-recipient firms) and the treatment group (recipient firms) through PSM, this study conducted an outcome analysis to estimate the net effect of the policy intervention. The analysis focused on firms that established smart factories in 2019 and 2020, with policy effects evaluated primarily through annual sales growth rates and CAGR, using completed 1:1 matching with corresponding non-recipient firms.

4.3.1. Recipient Firms vs. Non-Recipient Firms in 2019 (Post-PSM)

As shown in

Figure 5, recipient firms outperformed non-recipient firms in both average sales growth rate and CAGR across 2019, 2020, and 2021. This finding contrasts with the pre-PSM results, where non-recipient firms recorded higher performance in both 2020 and 2021.

Table 5 reports the ATE estimates and

t-test results after PSM. The ATE was positive for all four indicators, suggesting that the financial performance of recipient firms was generally higher than that of non-recipient firms. However, the difference in 2020 was not statistically significant (

p = 0.102).

These results illustrate the value of applying PSM. Performance differences that were obscured before matching became more interpretable after adjustment. Indicators that appeared insignificant or negative in the pre-PSM analysis either turned positive or exhibited clearer differences after PSM, reflecting a successful correction for selection bias and enhancing the credibility of causal effect estimation.

4.3.2. Recipient Firms vs. Non-Recipient Firms in 2020 (Post-PSM)

Similar patterns were observed in the 2020 cohort. As illustrated in

Figure 6, recipient firms outperformed non-recipient firms across all financial performance indicators.

Table 6 presents the ATE estimates and

t-test results for the 2020 cohort after PSM. Recipient firms demonstrated significantly stronger financial performance than non-recipient firms across all outcome variables. Importantly, the performance gap in 2021—where non-recipient firms had outperformed recipient firms prior to PSM—was reversed after matching, with recipient firms achieving significantly higher results.

4.4. Summary and Discussion of Analysis Results

Table 7 compares the ATE estimates before and after PSM for the 2019 and 2020 treatment–control pairs. For the 2019 cohort, the pre-PSM results indicated that non-recipient firms outperformed recipient firms in 2020 and 2021. After PSM, however, recipient firms exhibited superior performance across all indicators. Moreover, while no significant differences were observed between the treated and control groups prior to PSM, statistically significant differences emerged post-PSM in all years except 2020.

For the 2020 cohort, recipient firms demonstrated a significantly higher sales growth rate in 2021 after PSM. In addition, ATE values increased across the other outcome variables as well.

Overall, prior to PSM, non-recipient firms outperformed recipient firms in three of the seven outcome indicators. Following PSM, this trend reversed. Furthermore, the number of statistically significant results increased from two pre-PSM to six post-PSM. From a policy perspective, these findings suggest that the initially ambiguous effects of the support program became more clearly positive after accounting for selection bias, thereby providing stronger justification for the continuation of government support.

The propensity score can be regarded as a composite measure that represents the joint influence of confounding variables. Rather than directly controlling each confounder, balancing the propensity score makes the treated and control groups comparable. In this study, PSM was employed to identify control firms most similar to the treated firms, thereby constructing comparable groups. Moreover, by ensuring that the control group was the same size as the treatment group, this approach also addressed the issue of data imbalance.

This raises the question of whether controlling for propensity scores effectively balanced the confounding variables. To test this, we examined whether differences in the selected confounders—such as baseline sales and years of operation—between the treated and control groups changed before and after PSM. For this purpose, we calculated Cohen’s d for a total of 76 confounding variables, using the following formula:

Table 8 presents the statistics for the calculated Cohen’s d. For the 2019 analysis, the mean Cohen’s d decreased from 0.12 before PSM to 0.03 after PSM. The maximum value also dropped from 1.19 to 0.15. Furthermore, while 47 of the 76 variables showed significant differences prior to PSM, this number declined to 5 post-PSM. The largest reduction was observed for industry code C25, which decreased to approximately 1/103 of its original value.

The 2020 results were similar: the mean decreased from 0.12 to 0.03, and the maximum value declined from 0.95 to 0.23. The number of variables with significant differences dropped from 49 to 6. Among these, the largest relative reduction was found in industry code G46, which decreased to just 1/140 of its initial value.

In summary, although the gradient boosting algorithm used for propensity score estimation did not yield highly satisfactory predictive performance, it effectively fulfilled its primary purpose of controlling for confounding variables.

5. Conclusions

The South Korean government has implemented the Smart Factory policy as a core strategy for the digital transformation and intelligentization of manufacturing, with particular emphasis on expanding support for SMEs. This study set out to evaluate the effectiveness of this policy by examining firms that received support in 2019 and 2020, using SME data from 2018 to 2021. To achieve this, PSM—a widely used causal inference methodology—was employed to construct a control group of non-recipient firms matched to the recipient firms. This approach enabled the estimation of the pure causal effect, free from the influence of confounding variables.

By comparing treatment and control groups before and after PSM, this study confirmed that PSM improves the accuracy of effect estimation by accounting for confounding factors. The results highlight that PSM can serve as a valuable tool for evaluating policy effectiveness in non-experimental settings.

However, this study faced several limitations. First, multi-year panel data covering both pre- and post-treatment periods was not available at the time of analysis. Consequently, conventional panel-based methods such as difference-in-differences (DiD) could not be applied. Future research will be able to conduct more rigorous analyses once sufficient panel data are secured. Second, the propensity score prediction algorithm used in this study demonstrated limited predictive accuracy. With panel data, this limitation could potentially be addressed through the use of doubly robust approaches that combine counterfactual prediction with propensity score estimation. To mitigate these limitations, sales growth rate and CAGR were selected as outcome variables instead of sales amounts. Since these measures inherently reflect year-to-year differences in sales, the analysis retains characteristics similar to the DiD approach. In other words, differences between the treatment and control groups are essentially derived as differences-in-differences. Thus, even without explicitly applying the DiD method, this study was able to capture some of its advantages, including control for time-invariant fixed effects. Third, there may be potential bias arising from unobserved confounding factors such as managerial quality and R&D capability; however, it is practically impossible to control for all such variables. In addition, while segmenting companies into subgroups based on specific factors could provide additional insights, this approach may also introduce increased analytical complexity and difficulties in ensuring the validity of the results. These limitations should be acknowledged as one of the constraints of the study. Fourth, this study did not quantitatively address the ROI of the project. Detailed project cost data would be required to calculate a quantitative policy ROI, but such information was not available in the dataset of this study.

The findings of this study carry several important policy implications. First, the results provide empirical evidence that government support for smart factory adoption can enhance the financial performance of SMEs, particularly when appropriate methods are employed to control for selection bias. This underscores the value of continued public investment in digital transformation initiatives as a means of strengthening the competitiveness of smaller firms. In addition, the findings of this study can be effectively utilized in selecting target companies in the future, for example, by incorporating implementation experience as one of the selection criteria. Second, the analysis demonstrates that while the observed policy effects may appear ambiguous in simple comparisons, rigorous causal inference methods such as PSM can reveal significant positive impacts. This highlights the need for policymakers to incorporate advanced evaluation techniques into performance management systems. Doing so would enable more accurate assessments of program effectiveness and ensure that limited public resources are allocated efficiently.

Despite these contributions, this study also opens avenues for further research. First, during the propensity score estimation process, we employed gradient boosting algorithm to complement the low predictive power of the commonly used logistic regression model; however, we were still unable to achieve a satisfactory F1-score. A low F1-score in the propensity score model could indicate the poor classification of treatment assignment, leading to inaccurate matching between treated and control units. This could weaken covariate balance, violates the ignorability assumption, and results in biased estimates of the treatment effect. However, this limitation inevitably arose due to the restricted availability of covariate data, and it is expected to be overcome in the future as more comprehensive data become available. Second, the results suggest that the policy effects of smart factory adoption may vary over time, with short-term benefits emerging more clearly than long-term ones. Future studies should therefore adopt a longitudinal perspective to capture both immediate and delayed policy effects. Third, the analysis highlights the importance of securing richer longitudinal datasets and applying more advanced causal inference techniques, such as difference-in-differences or doubly robust estimation methods. Incorporating these approaches would allow researchers to more comprehensively evaluate both the direct and indirect impacts of smart factory policies, thereby providing stronger evidence for refining and sustaining government support programs.