The Mycobiota of High Altitude Pear Orchards Soil in Colombia

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

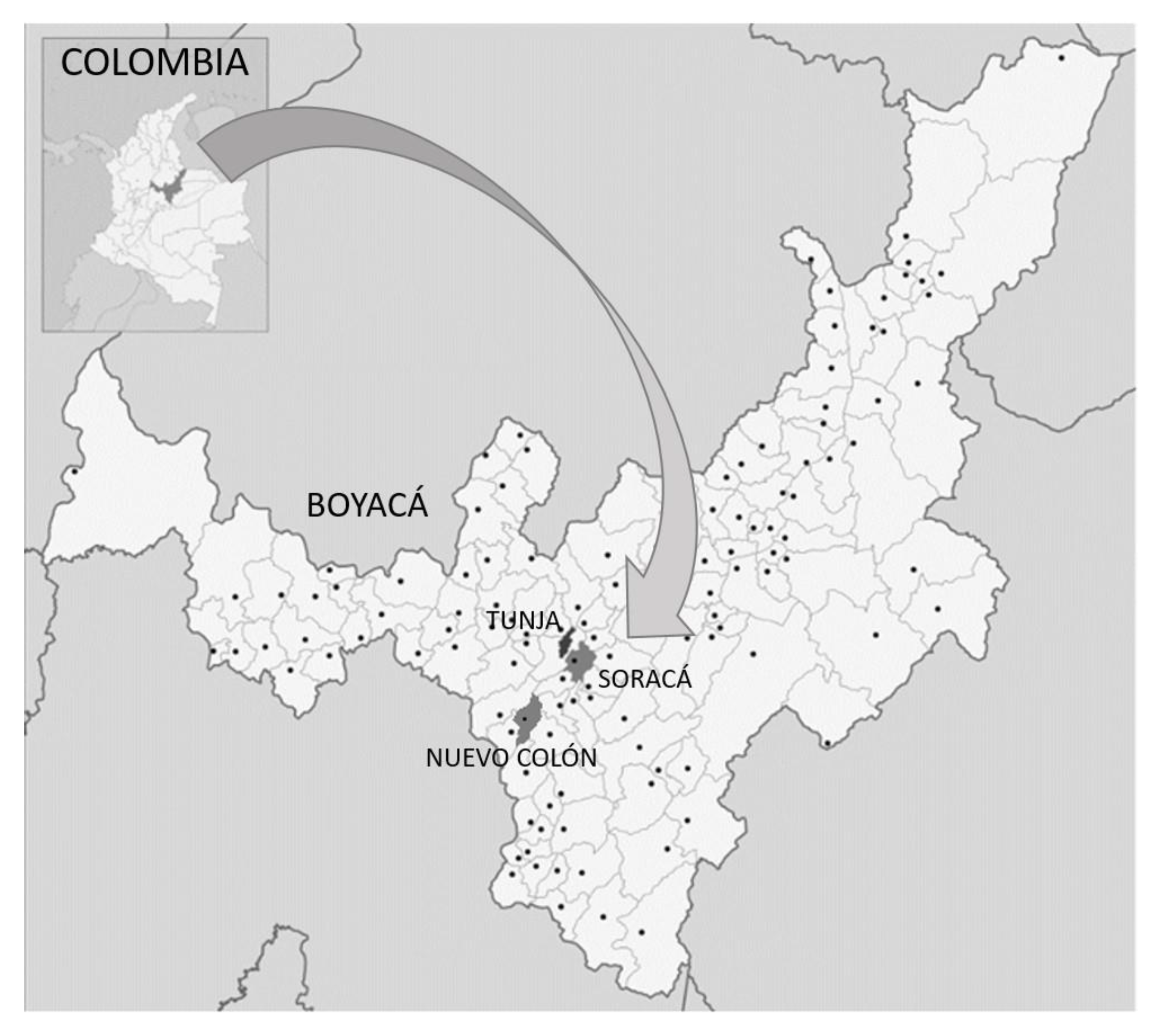

2.1. Area of Study

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Soil Physico-Chemical Analyses and Evaluation of Total Fungal Counts

2.4. DNA Extraction, ITS1 Amplification, Illumina Sequencing and Bioinformatic Data Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Soil Physico-Chemical Analyses and Evaluation of Total Fungal Counts

3.2. Soil Fungal Assemblage Composition

3.3. Soil Mycobiota Diversity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. FAOSTAT. 2019. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística-DANE. Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi-IGAC. Estudio General de Suelos y Zonificación de Tierras del Departamento de Boyacá; Tomo II, 1st ed.; IGAC: Bogotà, Colombia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural-MADR; Gobernación de Boyacá, Fondo Nacional de Fomento Hortifrutícola-FNFH; Asociación Hortifrutícola de Colombia-Asohofrucol; Sociedad de Agricultores y Ganaderos del Valle del Cauca-SAG. Desarrollo de la Fruticultura en Boyacá. Plan Frutícola Nacional, 1st ed; Ministerio de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural-MADR: Tunja, Colombia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Puentes, G. Sistema de producción de frutales caducifolios en el departamento de Boyacá. Equidad Desarro. 2006, 5, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chico, L.; Villota, L. Siembra intervención territorial. Diseño de experiencia de marca-territorio en el municipio de Soracá, Boyacá para el fortalecimiento de la agricultura de frutos caducifolios y de la competitividad de producto como identidad del territorio. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia, 20 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, M. A view of fungal ecology. Mycologia 1989, 81, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden, M.G.A.; Hartmann, M. Networking in the plant microbiome. PloS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panelli, S.; Capelli, E.; Comandatore, F.; Landinez-Torres, A.; Granata, M.U.; Tosi, S.; Picco, A.M. A metagenomic-based, cross-seasonal picture of fungal consortia associated with Italian soils subjected to different agricultural managements. Fungal Ecol. 2017, 30, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor, E.; Fuhrmann, O. Voyage d’exploration scientifique en Colombie. Available online: https://www.e-periodica.ch/cntmng?pid=bse-cr-001:1968:8::217 (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Martin, G. New or noteworthy fungi from Panama and Colombia I. Mycologia 1937, 29, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G. New or noteworthy fungi from Panama and Colombia II. Mycologia 1938, 30, 431–441. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, G. New or noteworthy fungi from Panama and Colombia III. Mycologia 1939, 31, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G. New or noteworthy fungi from Panama and Colombia IV. Mycologia 1939, 31, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, R. Oak mycorrhiza fungi in Colombia. Mycopathologia 1963, 20, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, G.; Varela, L. Los hongos de Colombia—III. Observaciones sobre los hongos, líquenes y mixomicetos de Colombia. Caldasia 1978, 12, 309–338. [Google Scholar]

- Landínez-Torres, A.Y.; Abril, J.L.B.; Tosi, S.; Nicola, L. Soil Microfungi of the Colombian Natural Regions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbandeh, M. Global Fruit Production in 2018, by Selected Variety (in Million Metric Tons). Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/264001/worldwide-production-of-fruit-by-variety/ (accessed on 22 September 2020).

- Zhang, Y.; Han, M.; Song, M.; Tian, J.; Song, B.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yao, Y. Intercropping with aromatic plants increased the soil organic matter content and changed the microbial community in a pear orchard. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 616932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadkertiová, R.; Dudášová, H.; Stratilová, E.; Balaščáková, M. Diversity of yeasts in the soil adjacent to fruit trees of the Rosaceae family. Yeast 2019, 36, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhao, F.; Wang, M.; Qi, K.; Wu, J.; Zhang, S. Soil chemical properties and geographical distance exerted effects on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal community composition in pear orchards in Jiangsu Province, China. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 142, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Pang, X.; Chen, X.; Ye, J.; Lin, S.; Jia, X. Rain-shelter cultivation influence rhizosphere bacterial community structure in pear and its relationship with fruit quality of pear and soil chemical properties. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 269, 109419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigoni, E.; Antonielli, L.; Pindo, M.; Pertot, I.; Perazzolli, M. Tissue age and plant genotype affect the microbiota of apple and pear bark. Microbiol. Res. 2018, 211, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volschenk, Q.; du Plessis, E.M.; Duvenage, F.J.; Korsten, L. Effect of postharvest practices on the culturable filamentous fungi and yeast microbiota associated with the pear carpoplane. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 118, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi—IGAC. Estudio General de Suelos y zonificación de tierras del departamento de Boyacá; Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi: Bogotà, Colombia, 2005; Volume 2, pp. 201–203. [Google Scholar]

- Colombia—Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales Promedios Climatológicos 1981–2010. Available online: http://www.ideam.gov.co/web/tiempo-y-clima/clima (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Wikimedia Commons, Mapa de Municipios de Soracá y Nuevo Colón, Boyacá (Colombia). Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Colombia_-_Boyaca_-_Soraca.svg (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Gams, W.; Hoestra, E.S.; Aptroot, A. CSB Course in Mycology, 4th ed.; CBS: Baarn, The Netherlands, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Landínez-Torres, A.Y.; Panelli, S.; Picco, A.M.; Comandatore, F.; Tosi, S.; Capelli, E. A meta-barcoding analysis of soil mycobiota of the upper Andean Colombian agro-environment. Sci. Rep-UK 2019, 9, 10085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Mills, D.A. Improved Selection of Internal Transcribed Spacer-Specific Primers Enables Quantitative, Ultra-High-Throughput Profiling of Fungal Communities. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2013, 79, 2519–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nilsson, H.; Larsson, K.-H.; Taylor, A.F.S.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Jeppesen, T.S.; Schigel, D.; Kennedy, P.; Picard, K.; Glöckner, F.O.; Tedersoo, L.; et al. The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi: Handling dark taxa and parallel taxonomic classifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 47, D259–D264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Sánchez-Ramírez, S.; Kõljalg, U.; Bahram, M.; Döring, M.; Schigel, D.; May, T.; Ryberg, M.; Abarenkov, K. High-level classification of the Fungi and a tool for evolutionary ecological analyses. Fungal Divers. 2018, 90, 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological statistics package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 9. [Google Scholar]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. Phyloseq: An r package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Simpson, G.L.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Wagner, H. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R Package Version 2. 0–10. 2013. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/index.html (accessed on 14 July 2020).

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suwannarach, N.; Kumla, J.; In-on, A.; Lumyong, S. Soil metabarcoding offers a new tool for the investigation and hunting of truffles in Northern Thailand. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Zhao, X.; Ren, J.; Dong, J.; Zhang, H.; Dong, Q.; Jiang, C.; Zhong, C.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, H. Influence of Peanut, Sorghum, and Soil Salinity on Microbial Community Composition in Interspecific Interaction Zone. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 678250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, A.; Pinochet, J.; Fernandez, C.; Calvet, C.; Caprumbi, A. Growth response of OHF-333 pear rootstock to arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, phosphorus nutrition and Pratylenchus vulnus infection. Fund. Appl. Nematol. 1997, 20, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Gualdrón-Arenas, C.; Suarez-Navarro, A.L.; Valencia-Zapata, H. Hongos del suelo aislados de zonas de vegetacion natural del paramo de Chisaca, Colombia. Caldasia 1997, 19, 235–245. [Google Scholar]

- Useche, Y.M.; Valencia, H.; Pérez, H. Caracterización de bacterias y hongos solubilizadores de fosfato bajo tres usos de suelo en el Sur del Trapecio Amazónico. Acta Biológica Colomb. 2004, 9, 129–130. [Google Scholar]

- Moratto, C.; Martínez, L.J.; Valencia, H.; Sánchez, J. Efecto del uso del suelo sobre hongos solubilizadores de fosfato y bacterias diazotróficas en el páramo de Guerrero (Cundinamarca). Agron. Colomb. 2005, 23, 299–309. [Google Scholar]

- Avellaneda-Torres, L.M.; Torres-Roja, E. Biodiversidad de grupos funcionales de microorganismos asociados a suelos bajo cultivo de papa, ganadería y páramo en el Parque Nacional Natural de Los Nevados, Colombia. Biota Colomb. 2015, 16, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitiva-Jaramillo, A.; Torrenegra-Guerrero, R.; Cabrera-Parada, C.; Díaz-Puentes, N.; Pineda-Parra, V. Contribución al Estudio de Microhongos Filamentosos en los Ecosistemas Páramo de Guasca y el Tablazo; Pontificia Universidad Javeriana: Bogotá, Colombia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Posada, R.H.; Sánchez de Prager, M.; Sieverding, E.; Dorantes, K.A.; Heredia-Abarca, G.P. Relaciones entre los hongos filamentosos y solubilizadores de fosfatos con algunas variables edáficas y el manejo de cafetales. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2012, 60, 1075–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posada, R.H.; Heredia-Abarca, G.; Sieverding, E.; Sánchez de Prager, M. Solubilization of iron and calcium phosphates by soil fungi isolated from coffee plantations. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2013, 59, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Moncada, D.A.; Jaramillo-Mazo, C.; Vásquez-Restrepo, J.; Ramírez, C.A.; Cardona-Bustos, N.L. Antagonismo de Purpureocillium sp. (cepa UdeA0106) con hongos aislados de cultivos de flores. Actual. Biológicas 2014, 36, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, R.; Vertel, M.; Pérez Cordero, A. Efecto de diferentes tipos de abonos sobre hongos edáficos en el agroecosistema de Bothriochloa pertusa, (L) A. Camus, En Sabanas sucreñas, Colombia. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2015, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Vera, D.F.; Pérez, H.; Valencia, H. Aislamiento de hongos solubilizadores de fosfatos de la rizosfera de arazá (Eugenia stipitata, Myrtaceae). Acta Biológica Colomb 2002, 7, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán Pineda, M.E. Hongos solubilizadores de fosfato en suelo de páramo cultivado con papa (Solanum tuberosum). Cienc. en Desarro. 2014, 5, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pérez, A.C.; De La Ossa, V.J.; Montes, V.D. Hongos solubilizadores de fosfatos en fincas ganaderas del departamento de sucre. Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Anim.—RECIA 2012, 4, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, M.L.; Uribe, D. Aislamiento de hongos degradadores de lignina a partir de suelos con dos usos agrícolas (sabana de pastoreo y bosque secundario) de sabana inundable, Puerto López (Meta). Soc. Colomb. la Cienc. del Suelo 2007, 37, 70–74. [Google Scholar]

- García, R.D.Y.; Cárdenas, H.J.F.; Silva Parra, A. Evaluación de sistemas de labranza sobre propiedades físico-químicas y microbiológicas en un Inceptisol. Rev. Ciencias Agrícolas 2018, 35, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ortiz, D.R.; Sarria-Villa, G.A.; Agudelo, F.V.de; Carabalí, A.G.; Espinosa, A.T.M. Reconocimiento de hongos con potencial benéfico asociados a la rizósfera de chontaduro (Bactris gasipaes H.B.K.) en la region Pacifico del Valle del Cauca, Colombia. Acta Agronómica 2011, 60, 319–327. [Google Scholar]

- Elías, R.; Arcos, O.; Arbeláez, G. Estudio del antagonismo de algunas especies de Trichoderma aisladas de suelos colombianos en el control de Fusarium oxysporum y Rhizoctonia solani. Agron. Colomb. 1993, 10, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Veerkamp, J.; Gams, W. Los hongos de Colombia—VIII: Some new species of soil fungi from Colombia. Caldasia 1983, 12, 710–717. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, M.L.O.; Vélez, D.U. Determinación de la actividad lignocelulolítica en sustrato natural de aislamientos fúngicos obtenidos de sabana de pastoreo y de bosque secundario de sabana inundable tropical. Cienc. del Suelo 2010, 28, 169–180. [Google Scholar]

- Simonin, M.; Dasilva, C.; Terzi, V.; Ngonkeu, M.; Diouf, D.; Kane, A.; Béna, G.; Moulin, L. Influence of plant genotype and soil on the wheat rhizosphere microbiome: Evidences for a core microbiome across eight African and European soils. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020, 96, fiaa067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aon, M.A.; Cabello, M.N.; Sarena, D.E.; Colaneri, A.C.; Franco, M.G.; Burgos, J.L.; Cortassa, S. Spatio-temporal patterns of soil microbial and enzymatic activities in an agricultural soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2001, 18, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, E.; Hanaka, A. Mortierella Species as the Plant Growth-Promoting Fungi Present in the Agricultural Soils. Agriculture 2021, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, B.S.; Baijal, U. Species of Mortierella from India-III. Mycopathol. Mycol. Appl. 1963, 20, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Chen, L.; Redmile-Gordon, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Ning, Q.; Li, W. Mortierella elongata’s roles in organic agriculture and crop growth promotion in a mineral soil. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 1642–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Venegas, C.P.; Cardona, G.I.; Mazorra, A.; Arguellez, J.H.; Arcos, A.L. Micorrizas Arbusculares dela Amazonia Colombiana, 1st ed.; Instituto Amazónico de Investigaciones Científicas–SINCHI: Bogotá, Colombia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Posada, R.H.; Sánchez de Prager, M.; Heredia-Abarca, G.; Sieverding, E. Effects of soil physical and chemical parameters, and farm management practices on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi communities and diversities in coffee plantations in Colombia and Mexico. Agrofor. Syst. 2018, 92, 555–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolaños-B, M.M.; Rivillas-Osorio, C.A.; Suárez-Vásquez, S. Identificación de micorrizas arbusculares en suelos de la zona cafetera colombiana. Cenicafé 2000, 51, 245–262. [Google Scholar]

- Schenck, N.C.; Spain, J.L.; Sieverding, E.; Howeler, R.H. Several New and Unreported Vesicular-Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (Endogonaceae) from Colombia. Mycologia 1984, 76, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, J.C.; Arias, I.; Koomen, I.; Hayman, D.S. The management of populations of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in acid-infertile soils of a savanna ecosystem. Plant Soil 1990, 122, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahecha-Vásquez, G.; Sierra, S.; Posada, R. Diversity indices using arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to evaluate the soil state in banana crops in Colombia. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2017, 109, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, R.M.; Taheri, W.I.; Osborne, S.L.; Buyer, J.S.; Douds Jr., D.D. Fall cover cropping can increase arbuscular mycorrhizae in soils supporting intensive agricultural production. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2012, 61, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshiri, M.H.; Mozafari, V.; Sedaghati, E.; Bagheri, V. Response of Petunia Plants (Petunia hybrida cv. Mix) Inoculated with Glomus mosseae and Glomus intraradices to Phosphorous and Drought Stress. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2011, 13, 929–942. [Google Scholar]

- George, P.B.L.; Creer, S.; Griffiths, R.I.; Emmet, B.A.; Robinson, D.A.; Jones, D.L. Primer and Database Choice Affect Fungal Functional but Not Biological Diversity Findings in a National Soil Survey. Front. Environ. Sci. 2019, 7, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mycobank Database of Pairwise Alignment. Available online: https://www.mycobank.org/page/Pairwise_alignment (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Kacprzak, M.; Malina, G. The tolerance and Zn2+, Ba2+ and Fe3+ accumulation by Trichoderma atroviride and Mortierella exigua isolated from contaminated soil. Can. J. Soil. Sci. 2005, 85, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, H.; Lv, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Ju, X.; Song, Z.; Ren, L.; Jia, B.; Qiao, M.; et al. High-yield oleaginous fungi and high-value microbial lipid resources from Mucoromycota. BioEnerg. Res 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, E.C.Q.; Godinho, V.M.; Silva, D.A.S.; de Paula, M.T.R.; Vitoreli, G.A.; Zani, C.L.; Alves, T.M.A.; Junior, P.A.S.; Murta, S.M.F.; Barbosa, E.C.; et al. Cultivable fungi present in Antarctic soils: Taxonomy, phylogeny, diversity, and bioprospecting of antiparasitic and herbicidal metabolites. Extremophiles 2018, 22, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooney, D.G.; Emerson, R. Thermophilic Fungi: An Account of Their Biology, Activities and Classification; W.H. Freeman & Co.: San Francisco, CA, USA; London, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Tiscornia, S.; Segui, C.; Bettucci, L. Composition and characterization of fungal communities from different composted materials. Cryptogamie Mycol. 2009, 30, 363–376. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, W.H.; Yang, C.H.; Lin, M.J.; Chen, C.Y.; Tsou, Y.J. Humicola phialophoroides sp. nov. from soil with potential for biological control of plant diseases. Bot. Stud. 2011, 52, 197–202. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, J.J.; Hu, J.; Ran, W.; Xu, Y.C.; Shen, Q.R. Control of cotton Verticillium wilt and fungal diversity of rhizosphere soils by bio-organic fertilizer. Biol. Fert. Soils 2012, 48, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.W.; Yang, R.Y.; Meijer, M.; Kraak, B.; Sun, B.D.; Jiang, Y.L.; Wu, Y.M.; Bai, F.Y.; Seifert, K.A.; Crous, P.W.; et al. Redefining Humicola sensu stricto and related genera in the Chaetomiaceae. Stud. Mycol. 2019, 93, 65–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurkov, A. Yeasts of the soil—obscure but prescious. Yeast 2018, 5, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keswani, C.; Singh, S.P.; Cueto, L.; Garcia-Estrada, C.; Mezaache-Aichour, S.; Glare, T.R.; Boriss, R.; Singh, S.P.; Blazquez, M.A.; Sansinenea, E. Auxins of microbial origin and their use in agriculture. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 2020, 104, 8549–8565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerbell, R. Ascomycetes: Aspergillus, Fusarium, Sporothrix, Piedraia, and Their Relatives. In Pathogenic Fungi in Humans and Animals, 2nd ed.; Howard, D.H., Ed.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 400–425. [Google Scholar]

- Najafzadeh, M.J.; Dolatabadi, S.; Saradeghi Keisari, M.; Naseri, A.; Feng, P.; de Hoog, G.S. Detection and identification of opportunistic Exophiala species using the rolling circle amplification of ribosomal internal transcribed spacers. J. Microbiol. Methods 2013, 94, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.M.; Rajendran, R.K.; Lin, Y.F.; Kirschner, R.; Hu, S. Onychomycosis associated with Exophiala oligosperma in Taiwan. Mycopathologia 2015, 181, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, S.T.; Reddy, G.S.N.; Garcia-Pichel, F. Exophiala crusticola anam. nov. (affinity Herpotrichiellaceae), a novel black yeast from biological soil crusts in the Western United States. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2006, 56, 2697–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Hoog, G.S.; Vicente, V.A.; Najafzadeh, M.J.; Harrak, M.J.; Badali, H.; Seyedmousavi, S. Waterborne Exophiala species causing disease in cold-blooded animals. Persoonia 2011, 27, 46–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferrari, B.C.; Zhang, C.; van Dorst, J. Recovering greater fungal diversity from pristine and diesel fuel contaminated sub-Antarctic soil through cultivation using both a high and a low nutrient media approach. Front. Microbiol. 2011, 2, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maciá-Vicente, J.G.; Glynou, K.; Piepenbring, M. A new species of Exophiala associated with roots. Mycol. Progress 2016, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogórek, R.; Kurczaba, K.; Łobas, Z.; Jakubska-Busse, A. Species diversity of micromycetes associated with Epipactis helleborine and Epipactis purpurata (Orchidaceae, Neottieae) in Southwestern Poland. Diversity 2020, 12, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, S.S.; Zreik, M.M.; Mulder, J.L. Distribution of arachidonic acid among lipid classes during culture ageing of five Zygomycete species. Mycol. Res. 1996, 100, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, A.; Bosshardt Hughes, O.; Palavecino, E.L.; Jakharia, N. Cutaneous infection caused by Paraconiothyrium cyclothyrioides in a renal transplant recipient. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2021, 23, e13624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Nara, K.; Lian, C.; Zong, K.; Peng, K.; Xue, S.; Shen, Z. Ectomycorrhizal fungal communities associated with Masson pine (Pinus massoniana Lamb.) in Pb-Zn sites of central south China. Mycorrhiza 2012, 22, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brayford, D. Cylindrocarpon. In Methods for Research on Soilborne Phytopathogenic Fungi; Singleton, L.L., Mihail, J.D., Rush, M., Eds.; APS Press: St Paul, MN, USA, 1993; pp. 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchel, D. Survey of the Grassland Fungi of County Clare; Heritage Council: Dublin, Ireland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vidović, S.; Zeković, Z.; Jokić, S. Clavaria mushrooms and extracts: Investigation on valuable components and antioxidant properties. Int. J. Food Prop. 2014, 17, 2072–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, K.; Perry, B.A.; Drabfinis, A.W.; Pfister, D.H. A phylogeny of highly diverse cup-fungus family Pyronemataceae (Pezizomycetes, Ascomycota) clarifies relationships and evolution of selected life history traits. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2013, 67, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L. Soil fungal communities associated with plant health as revealed by next-generation sequencing. Ph.D. Thesis, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.H.; Ravnskov, S.; Larsen, J.; Nilsson, R.H.; Nicolaisen, M. Soil fungal community structure along a soil health gradient in pea fields examined using deep amplicon sequencing. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 46, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; van den Ende, A.H.G.G.; Bakkers, J.M.J.E.; Sun, J.; Lackner, M.; Najafzadeh, M.J.; Melchers, W.J.G.; Li, R.; de Hoog, G.S. Identification of Pseudallescheria and Scedosporium species by three molecular methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Grantina-Ievina, L.; Andersone, U.; Berkolde-Pire, D.; Nikolajeva, Y.; Ievinsh, G. Critical tests for determination of microbiological quality and biological activity in commercial vermicompost samples of different origins. Environ. Biotech. 2013, 97, 10541–10554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmarán, C.C.; Berretta, M.; Martínez, S.; Barrera, V.; Munaut, F.; Gasoni, L. Species diversity of Cladorrhinum in Argentina and description of a new species, Cladorrhinum australe. Mycol. Prog. 2015, 14, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaya, A.; Xue, A.; Hsiang, T. Selection and screening of fungal endophytes against wheat pathogens. Biol. Control 2021, 154, 104511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsonowati, W.; Marian, M.; Narisawa, K. The effectiveness of a dark septate endophytic fungus, Cladophiara chaetospira SK51, to mitigate strawberry Fusarium wilt disease and with growth promotion activities. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, T.; Liu, M.J.; Zhang, X.T.; Zhang, H.B.; Sha, T.; Zhao, Z.W. Improved tolerance of maize (Zea mays L.) to heavy metals by colonization of a dark septate endophyte (DSE) Exophiala pisciphila. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 1069–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, S.; Kumar, A.; Singh, B.; Nain, L.; Joshi, M.; Satya, S. Bioaugmented composting of Jatropha de-oiled cake and vegetable waste under aerobic and partial anaerobic conditions. J. Basic Microbiol. 2013, 53, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethuraman, A.; Janzen, F.J.; Weisrock, D.W.; Obrycki, J.J. Insights from population genomics to enhance and sustain biological control of insect pests. Insects 2020, 11, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, G.B.P.; Heckler, L.L.; dos Santos, R.F.; Durigon, M.R.; Blume, E. Identification and utilization of Trichoderma spp. stored and native in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum biocontrol. Rev. Caatinga 2015, 28, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plot | Sand | Silt | Clay | Soil texture | Moisture (105 °C) | pH | C org. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (USDA) | (g/kg) | (%) | ||

| SR | 36.6 ± 2.6 | 47.4 ± 2.3 | 15.9 ± 4.1 | Loam | 211.1 ± 13.9 | 5.4 ± 0.2 * | 2.3 ± 0.1 |

| NC-A | 38.3 ± 4.5 | 44.4 ± 8.1 | 17.3 ± 3.6 | Loam | 213.2 ± 14.6 | 6.1 ± 0.3 | 3.2 ± 0.4 |

| NC-B | 39.3 ± 2.1 | 47.9 ± 1.4 | 12.8 ± 0.7 | Loam | 203.7 ± 6.0 | 6.6 ± 0.1 * | 2.8 ± 0.3 |

| Plot | Organic matter | N tot | C/N | Ca | Mg | K | P |

| (%) | (%) | (mg/kg) | (mg/kg) | (mg/kg) | (mg/kg) | ||

| SR | 4.0 ± 0.2 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 11.1 ± 0.3 | 1540 ± 202 | 156 ± 36 | 355 ± 31 | 97.0 ± 10.0 * |

| NC-A | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 0.25 ± 0.03 | 12.7 ± 0.1 | 2700 ± 400 | 144 ± 16 | 304 ± 27 | 209.1 ± 34.4 |

| NC-B | 4.9 ± 0.4 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 11.5 ± 0.6 | 3060 ± 340 | 168 ± 13 | 347 ± 78 | 281.2 ± 23.6 * |

| Observed | Shannon | Simpson | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SR | 201.67 ± 26.58 | 4.31 ± 0.33 | 0.97 ± 0.01 |

| NC-A | 222.33 ± 1.53 | 4.36 ± 0.04 | 0.97 ± 0.01 |

| NC-B | 180.33 ± 37.87 | 3.89 ± 0.49 | 0.93 ± 0.05 |

| Species | Relative Abundance |

|---|---|

| Mortierella exigua Linnem. | 6.69% |

| Humicola olivacea X.Wei Wang & Samson | 2.13% |

| Solicoccozyma terrea (Di Menna) Yurkov | 1.80% |

| Chaetomium homopilatum Omvik | 1.47% |

| Mortierella camargensis W. Gams & R. Moreau | 1.43% |

| Fusarium solani (Mart.) Sacc. | 1.35% |

| Exophiala radicis Maciá-Vicente, Glynou & M. Piepenbr. var.1 | 1.30% |

| Mortierella amoeboidea W. Gams | 1.20% |

| Humicola nigrescens Omvik | 1.09% |

| Solicoccozyma phenolica (Á. Fonseca, Scorzetti & Fell) Yurkov | 0.63% |

| Bionectria rossmaniae Schroers | 0.49% |

| Gibberella intricans Wollenw. var.1 | 0.48% |

| Exophiala radicis Maciá-Vicente, Glynou & M. Piepenbr. var.2 | 0.44% |

| Metacordyceps chlamydosporia (H.C. Evans) G.H. Sung, J.M. Sung, Hywel-Jones & Spatafora | 0.42% |

| Thelonectria rubrococca (Brayford & Samuels) Salgado & P. Chaverri | 0.40% |

| Clonostachys divergens Schroers | 0.38% |

| Diaporthe columnaris (D.F. Farr & Castl.) Udayanga & Castl. | 0.37% |

| Mortierella alpina Peyronel | 0.32% |

| Cladosporium delicatulum Cooke | 0.29% |

| Auxarthron umbrinum (Boud.) G.F. Orr & Plunkett | 0.27% |

| Fusarium cuneirostrum O’Donnell & T. Aoki var.1 | 0.25% |

| Fusarium cuneirostrum O’Donnell & T. Aoki var.2 | 0.23% |

| Mucor moelleri (Vuill.) Lendn. | 0.23% |

| Mortierella gamsii Milko | 0.16% |

| Periconia macrospinosa Lefebvre & Aar.G. Johnson | 0.15% |

| Exophiala bonariae Isola & Zucconi | 0.13% |

| Ilyonectria robusta (A.A. Hildebr.) A. Cabral & Crous | 0.12% |

| Aspergillus wentii Wehmer | 0.11% |

| Penicillium virgatum Nirenberg & Kwaśna | 0.09% |

| Gibberella intricans Wollenw. var.2 | 0.07% |

| Penicillium camemberti Thom | 0.07% |

| Metarhizium marquandii (Massee) Kepler, S.A. Rehner & Humber | 0.06% |

| Exophiala pisciphila McGinnis & Ajello | 0.05% |

| Absidia anomala Hesselt. & J.J. Ellis | 0.04% |

| Penicillium jensenii K.W. Zaleski | 0.03% |

| OTUs | Relative Abundance SR | Relative Abundance NC | Adjusted p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fusarium sp. 1 | 8.47% | 0.00% | 5.74 × 10−25 |

| Chaetomium homopilatum Omvik | 4.81% | 0.00% | 5.25 × 10−22 |

| Leohumicola levissima H.D.T. Nguyen & Seifert | 3.62% | 0.00% | 9.34 × 10−11 |

| Cylindrocarpon sp. 1 | 3.00% | 0.00% | 1.44 × 10−4 |

| Solicoccozyma sp. | 2.36% | 0.00% | 1.60 × 10−14 |

| Paraconiothyrium cyclothyrioides Verkley | 1.61% | 0.00% | 2.46 × 10−11 |

| Clavaria sp. 1 | 1.34% | 0.00% | 3.22 × 10−4 |

| Fusarium nisikadoi T. Aoki & Nirenberg | 1.30% | 0.00% | 8.39 × 10−10 |

| Cylindrocarpon sp. 2 | 1.15% | 0.00% | 1.60 × 10−9 |

| Clavaria sp. 2 | 1.08% | 0.00% | 5.20 × 10−4 |

| Amaurodon sp. | 1.05% | 0.00% | 9.07 × 10−4 |

| Mortierella sp. 1 | 1.00% | 0.00% | 1.53 × 10−8 |

| OTUs | Relative Abundance SR | Relative Abundance NC | Adjusted p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudaleuria sp. | 0.08% | 9.76% | 5.86 × 10−3 |

| Mortierella alpina Peyronel | 0.00% | 6.44% | 5.90 × 10−18 |

| Fusarium sp. 2 | 0.00% | 5.95% | 4.01 × 10−19 |

| Pseudallescheria fimeti (Arx, Mukerji & N. Singh) McGinnis, A.A. Padhye & Ajello | 0.00% | 5.23% | 2.64 × 10−17 |

| Solicoccozyma terrea (Di Menna) Yurkov var.1 | 0.41% | 4.98% | 2.17 × 10−4 |

| Mortierella gamsii Milko | 0.00% | 3.17% | 2.38 × 10−10 |

| Cylindrocarpon sp. 3 | 0.00% | 2.48% | 3.78 × 10−8 |

| Cladorrhinum sp. | 0.00% | 1.54% | 4.47 × 10−11 |

| Solicoccozyma terrea (Di Menna) Yurkov var.2 | 0.00% | 1.43% | 1.44 × 10−11 |

| Mortierella sp. 2 | 0.00% | 1.20% | 1.07 × 10−12 |

| Exophiala pisciphila McGinnis & Ajello | 0.00% | 1.09% | 7.04 × 10−10 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nicola, L.; Landínez-Torres, A.Y.; Zambuto, F.; Capelli, E.; Tosi, S. The Mycobiota of High Altitude Pear Orchards Soil in Colombia. Biology 2021, 10, 1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10101002

Nicola L, Landínez-Torres AY, Zambuto F, Capelli E, Tosi S. The Mycobiota of High Altitude Pear Orchards Soil in Colombia. Biology. 2021; 10(10):1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10101002

Chicago/Turabian StyleNicola, Lidia, Angela Yaneth Landínez-Torres, Francesco Zambuto, Enrica Capelli, and Solveig Tosi. 2021. "The Mycobiota of High Altitude Pear Orchards Soil in Colombia" Biology 10, no. 10: 1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10101002

APA StyleNicola, L., Landínez-Torres, A. Y., Zambuto, F., Capelli, E., & Tosi, S. (2021). The Mycobiota of High Altitude Pear Orchards Soil in Colombia. Biology, 10(10), 1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10101002