Bonding Characteristics and Chemical Inertness of Zr–Si–N Coatings with a High Si Content in Glass Molding

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. As-Deposited Zr–Si–N Coatings

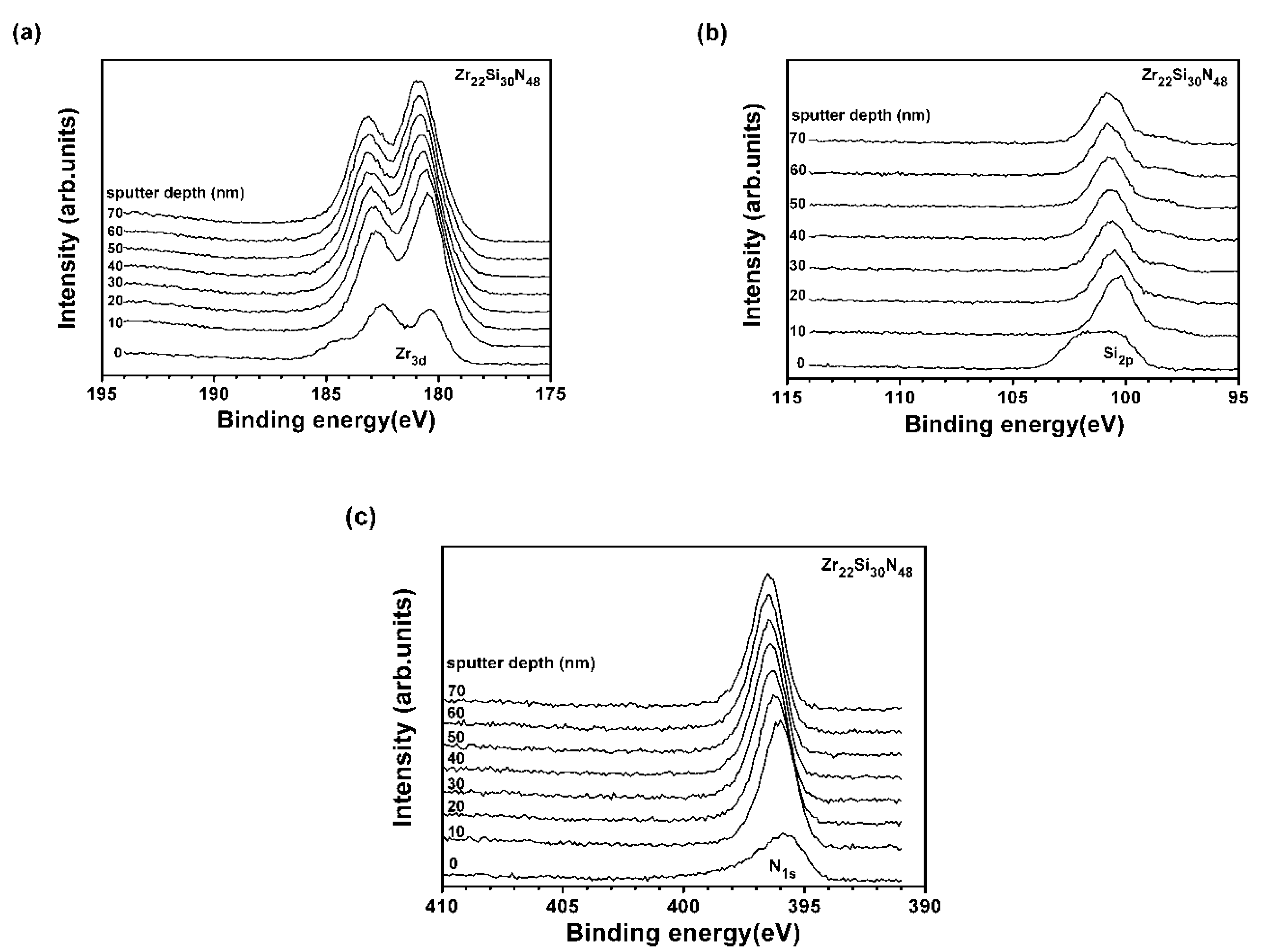

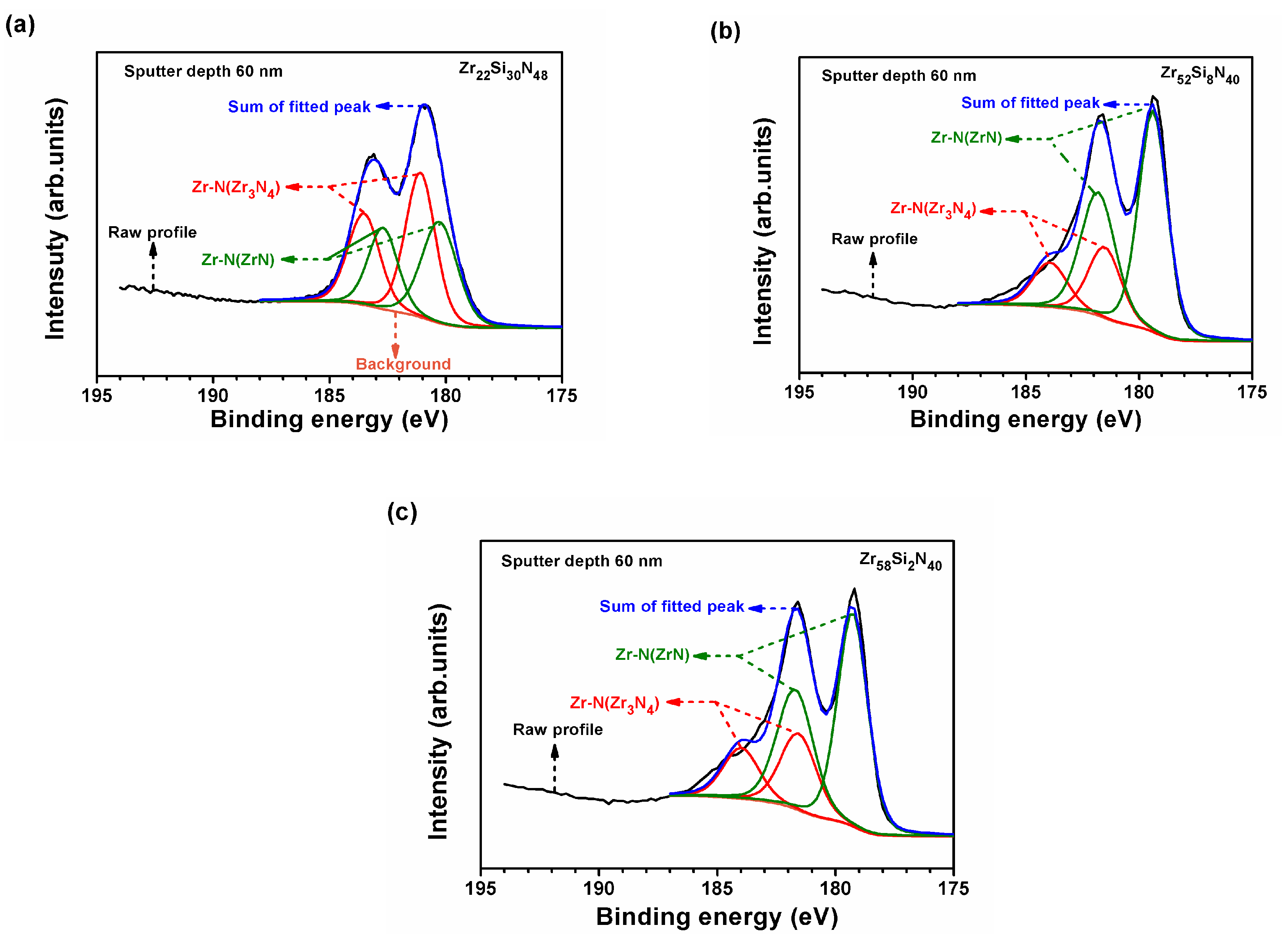

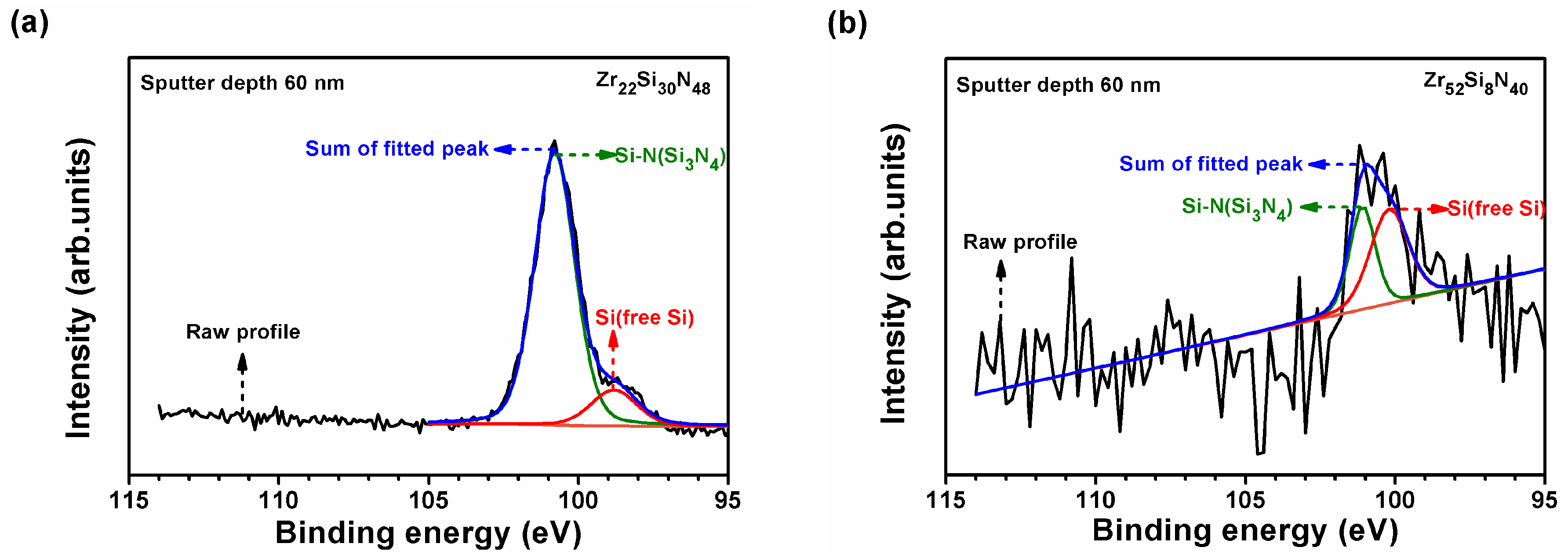

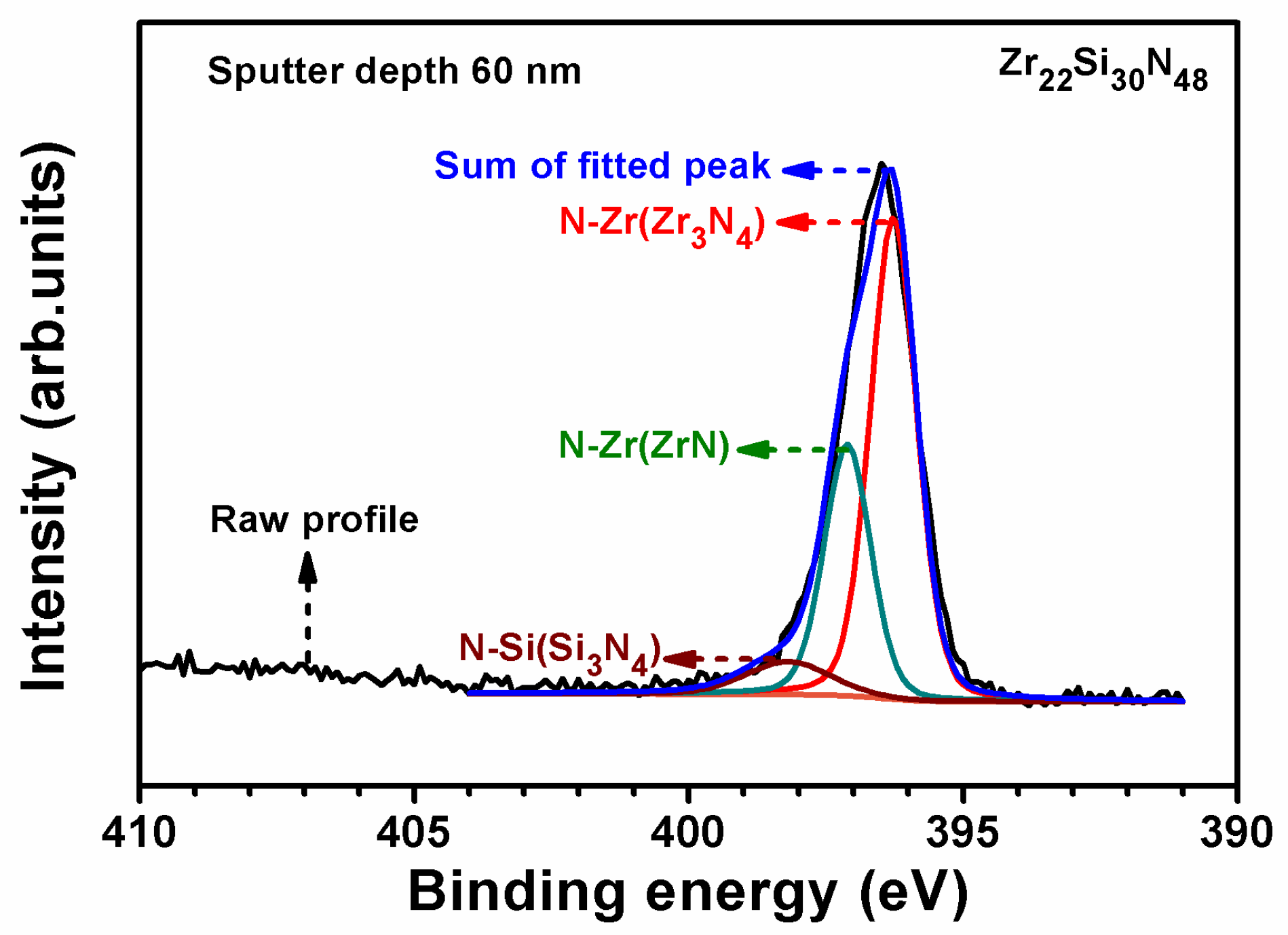

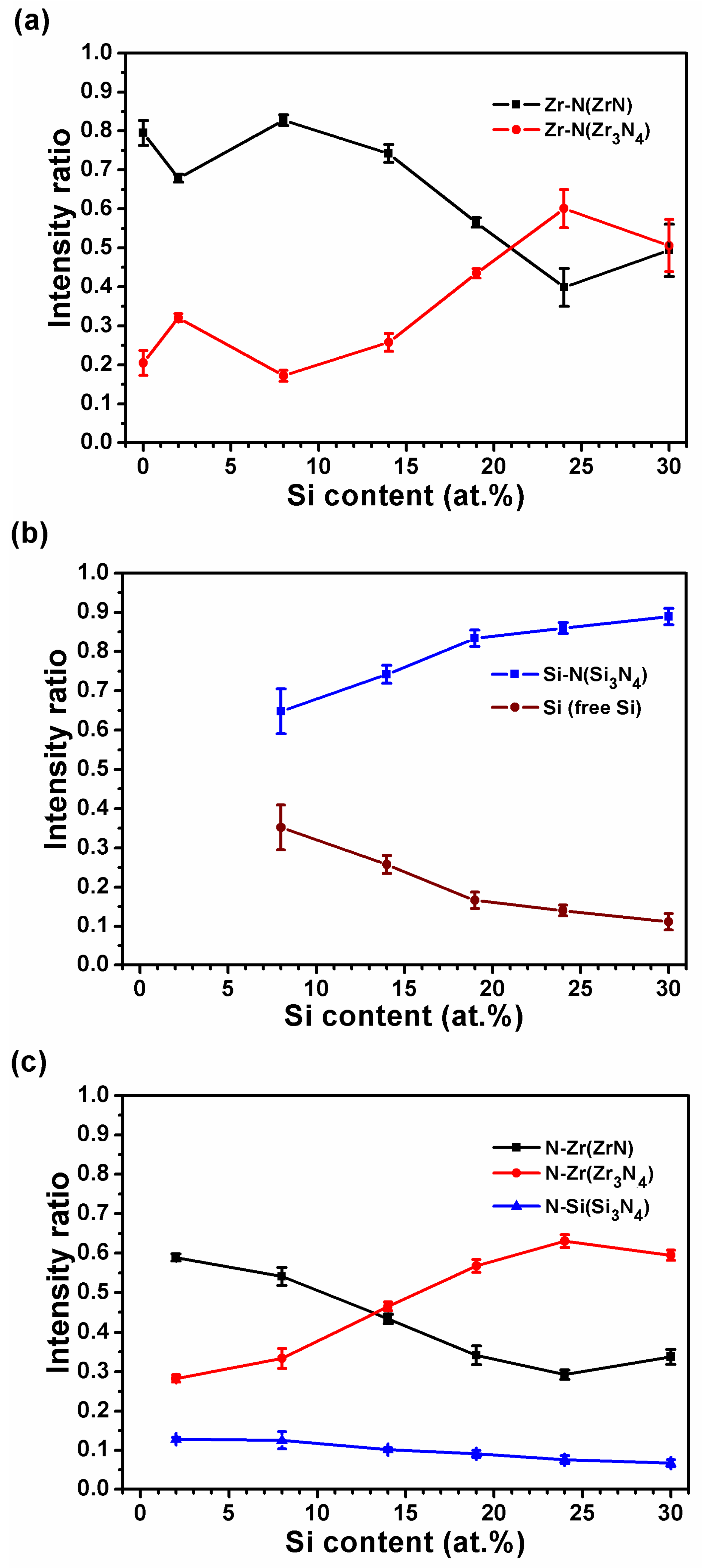

3.2. XPS Study of Zr–Si–N Coatings

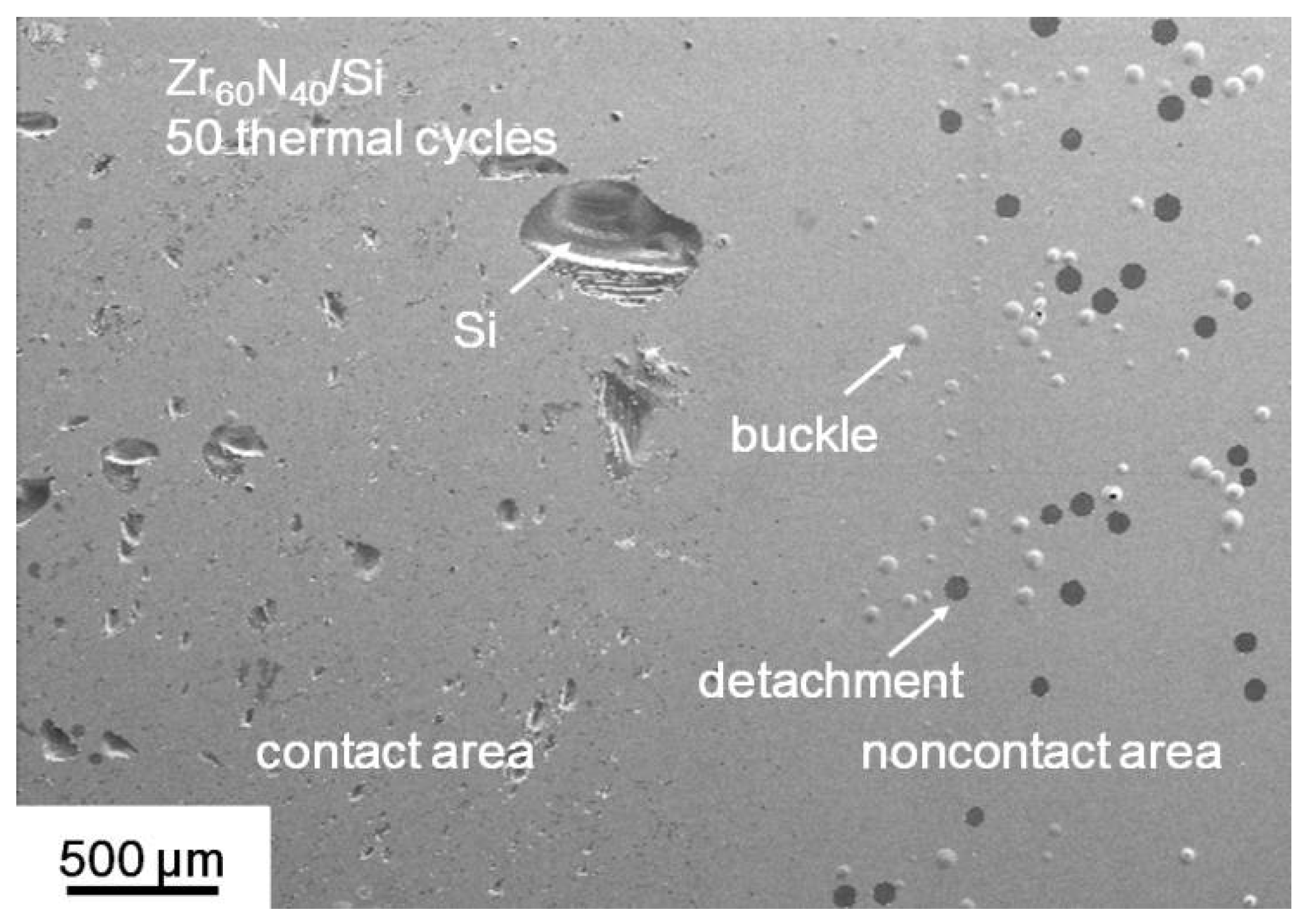

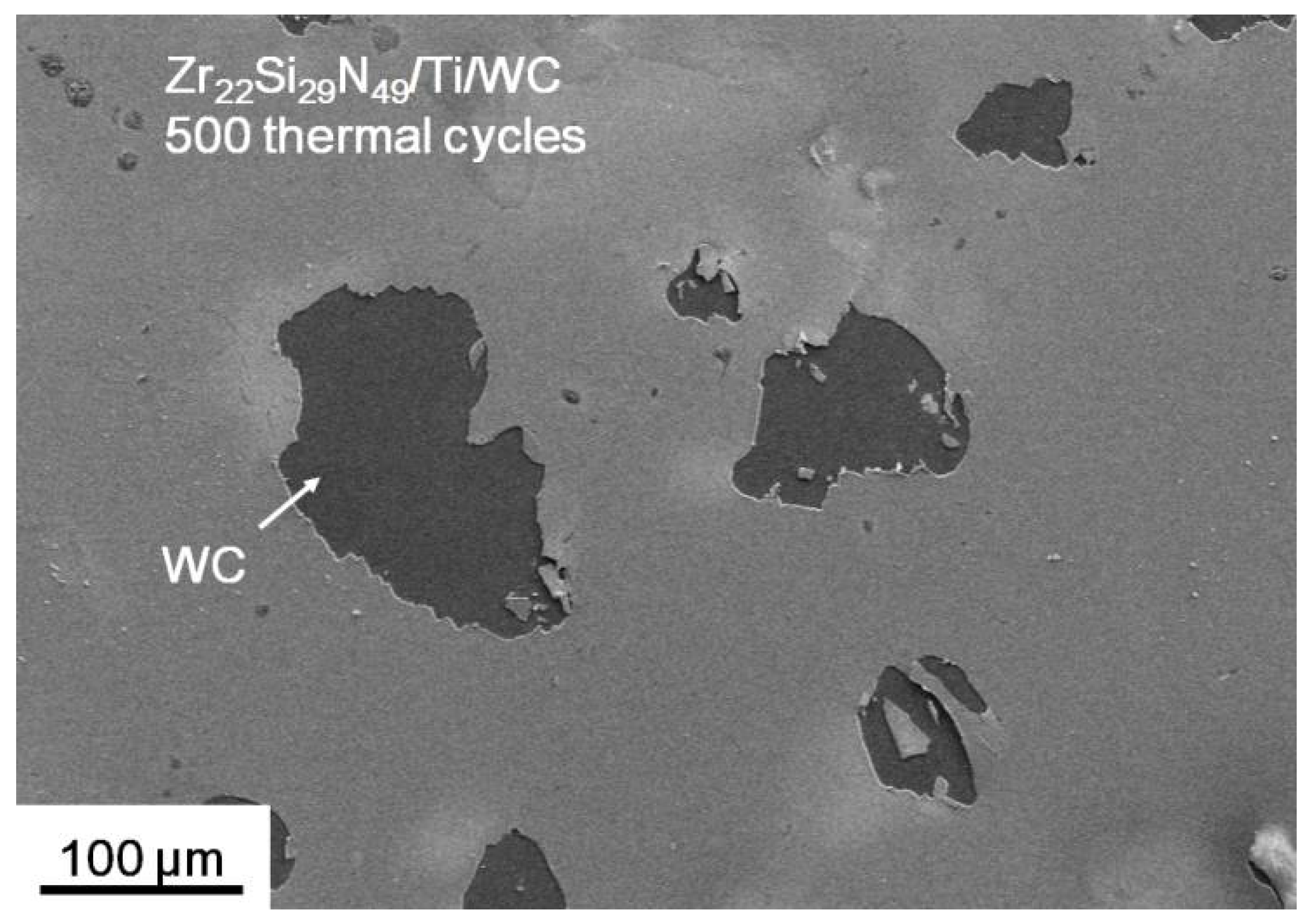

3.3. Thermal Stability and Chemical Inertness of Zr–Si–N Coatings

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Katsuki, M. Transferability of glass lens molding. Proc. SPIE 2006, 6149, 61490M. [Google Scholar]

- Maschmeyer, R.O.; Andrysick, C.A.; Geyer, T.W.; Meissner, H.E.; Parker, C.J.; Sanford, L.M. Precision molded-glass optics. Appl. Opt. 1983, 22, 2410–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, A.Y.; Jain, A. Compression molding of aspherical glass lenses—A combined experimental and numerical analysis. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2005, 88, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monji, H.; Aoki, M.; Torii, H.; Okinaka, H. Molding Method for Producing Optical Glass Element. U.S. Patent 4,629,487A, 16 December 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kuribayashi, K.; Sakai, M.; Monji, H.; Aoki, M.; Okinaka, H.; Torii, H. Mold for Press-Molding Glass Optical Elements and a Molding Method Using the Same. U.S. Patent 4,685,948A, 11 August 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.B.; Chen, W.Y.; Duh, J.G.; Tsai, Y.Y.; Chen, Y.I. Ir-based multi-component coating on tungsten carbide by RF magnetron sputtering process. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2003, 163–164, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klocke, F.; Bouzakis, K.D.; Georgiadis, K.; Gerardis, S.; Skordaris, G.; Pappa, M. Adhesive interlayers’ effect on the entire structure strength of glass molding tools’ Pt–Ir coatings by nano-tests determined. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2011, 206, 1867–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.L.; Huo, C.B.; Chou, W.C.; Lin, Y.R.; Ma, K.J.; Chien, H.H. Study on the design of precious metal based protective films for glass moulding process. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2013, 231, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.C.; Chen, Y.I.; Tsai, H.Y.; Lin, K.C.; Chen, Y.H. Thermal stability of Ir–Re coatings annealed in oxygen containing atmospheres. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2013, 237, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.C.; Chen, Y.I.; Shyu, J.J.; Tsai, H.Y.; Lin, K.Y.; Chen, Y.H.; Lin, K.C. The chemical inertness of Ir–Re and Ta–Ru coatings in molding B2O3-ZnO-La2O3-based glass. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2014, 259, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.Y.; Wei, J.J.; Chen, L.X.; Liu, J.L.; Hei, L.F.; Li, C.M.; Zhang, Y. Anti-sticking Re–Ir coating for glass molding process. Thin Solid Films 2015, 584, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uno, K.; Fujino, T.; Nakamori, H. Process for producing mold used for obtaining press molded glass article. U.S. Patent 5,008,002A, 16 April 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hirota, S.; Oogami, Y.; Hashimoto, K. Method of molding a glass composition into an optical element. U.S. Patent 6,776,007B2, 17 August 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kleer, G.; Doell, W. Ceramic multilayer coatings for glass moulding applications. Surf. Coat. Technol. 1997, 94–95, 647–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hock, M.; Schäffer, E.; Döll, W.; Kleer, G. Composite coating materials for the moulding of diffractive and refractive optical components of inorganic glasses. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2003, 163–164, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Duh, J.G.; Yau, B.S. Processing of chromium tungsten nitride hard coatings for glass molding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2006, 201, 1316–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischbach, K.D.; Georgiadis, K.; Wang, F.; Dambon, O.; Klocke, F.; Chen, Y.; Yi, A.Y. Investigation of the effects of process parameters on the glass-to-mold sticking force during precision glass molding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2010, 205, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.N.; Han, S.; Weng, K.W.; Lee, C.T. Investigation on the structural and mechanical properties of anti-sticking sputtered tungsten chromium nitride films. Thin Solid Films 2013, 529, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.Y.; Cheng, C.M.; Liou, Y.Y.; Tillmann, W.; Hoffmann, F.; Sprute, T. High temperature wettability of multicomponent CrAlSiN and TiAlSiN coatings by molten glass. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2013, 231, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.I.; Wang, H.H. Oxidation resistance and mechanical properties of Cr–Ta–Si–N coatings in glass molding processes. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2014, 260, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.I.; Cheng, Y.R.; Chang, L.C.; Lu, T.S. Chemical inertness of Ta–Si–N coatings in glass molding. Thin Solid Films 2015, 584, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.I.; Cheng, Y.R.; Chang, L.C.; Lee, J.W. Chemical inertness of Cr–W–N coatings in glass molding. Thin Solid Films 2015, 593, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.C.; Zheng, Y.Z.; Gao, Y.X.; Chen, Y.I. Mechanical properties and oxidation resistance of sputtered Cr–W–N coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 320, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vepřek, S.; Haussmann, M.; Reiprich, S.; Shizhi, L.; Dian, J. Novel thermodynamically stable and oxidation resistant superhard coating materials. Surf. Coat. Technol. 1996, 86–87, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.B.; Cho, K.; Lee, M.H.; Kim, K.H. Effects of Si content and free Si on oxidation behavior of Ti–Si–N coating layers. Thin Solid Films 2014, 447–448, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyer, P.; Pilloud, D.; Pierson, J.F.; Millet, J.-P.; Charnay, M.; Stauder, B.; Jacquot, P. Oxidation resistance improvement of arc-evaporated TiN hard coatings by silicon addition. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2006, 201, 4158–4162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nose, M.; Zhou, M.; Nagae, T.; Mae, T.; Yokota, M.; Saji, S. Properties of Zr–Si–N coatings prepared by RF reactive sputtering. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2000, 132, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilloud, D.; Pierson, J.F.; Marco de Lucas, M.C.; Alnot, M. Stabilisation of tetragonal zirconia in oxidized Zr–Si–N nanocomposite coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2004, 229, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeman, P.; Musil, J. Difference in high-temperature oxidation resistance of amorphous Zr–Si–N and W–Si–N films with a high Si content. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2006, 252, 8319–8325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musil, J. Hard nanocomposite coatings: Thermal stability, oxidation resistance and toughness. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2012, 207, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.I.; Chang, S.C.; Chang, L.C. Oxidation resistance and mechanical properties of Zr–Si–N coatings with cyclic gradient concentration. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 320, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.I.; Lin, K.Y.; Wang, H.H.; Cheng, Y.R. Characterization of Ta–Si–N coatings prepared using direct current magnetron co-sputtering. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 305, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.I.; Lin, K.Y.; Wang, H.H.; Lin, K.C. Thermal stability of TaN, CrTaN, TaSiN, and CrTaSiN hard coatings in oxygen-containing atmospheres. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2014, 259, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulder, J.F.; Stickle, W.F.; Sobol, P.E.; Bomben, K.D. Handbook of X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy; Chastain, J., King, R.C., Eds.; Physical Electronics: Chanhassen, MN, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, W.C.; Pharr, G.M. An improved technique for determining hardness and elastic modulus using load and displacement sensing indentation experiments. J. Mater. Res. 1992, 7, 1564–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.M. Rough Surfaces, 2nd ed.; Imperial College Press: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, G.C.A.M.; Abdalla, M.M.; van Keulen, F.; Pujada, B.R.; van Venrooy, B. Celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Stoney equation for film stress: Developments from polycrystalline steel strips to single crystal silicon wafers. Thin Solid Films 2009, 517, 1858–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brantly, W.A. Calculated elastic constants for stress problems associated with semiconductor devices. J. Appl. Phys. 1973, 44, 534–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertóti, I. Characterization of nitride coatings by XPS. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2002, 151–152, 194–203. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.H.; Guruz, M.; Chung, Y.W.; Keer, L.M. Thermal stability of hard TiN/SiNx multilayer coatings with an equiaxed microstructure. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2002, 154, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Zhao, W.; Yue, J.; Li, G. Crystallization of Si3N4 layers and its influences on the microstructure and mechanical properties of ZrN/Si3N4 nanomultilayers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 89, 121916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadias, G.; Uglov, V.V.; Saladukhin, I.A.; Zlotski, S.V.; Tolmachova, G.; Dub, S.N.; Janse van Vuuren, A. Growth, structural and mechanical properties of magnetron-sputtered ZrN/SiNx nanolaminated coatings, Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 308, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

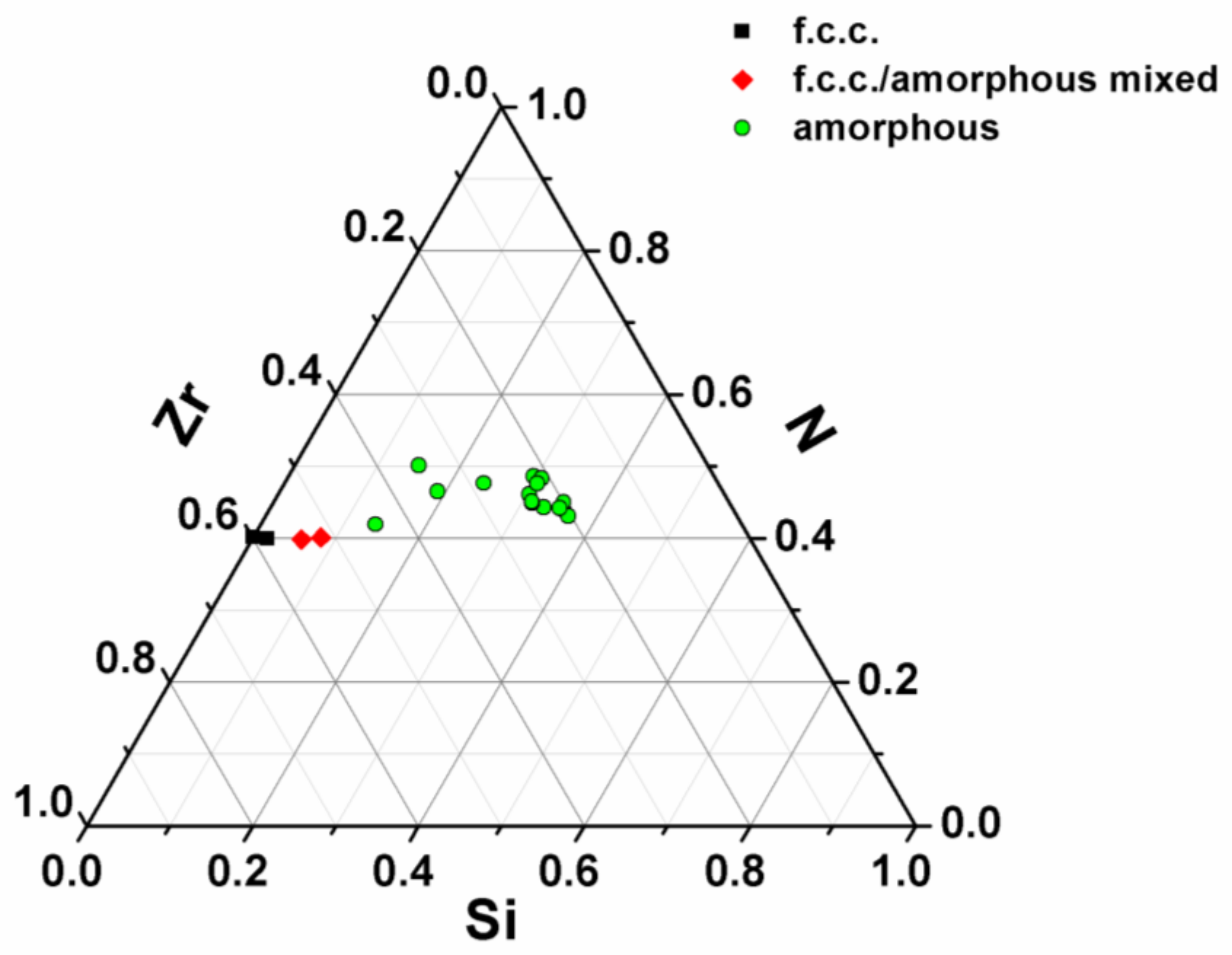

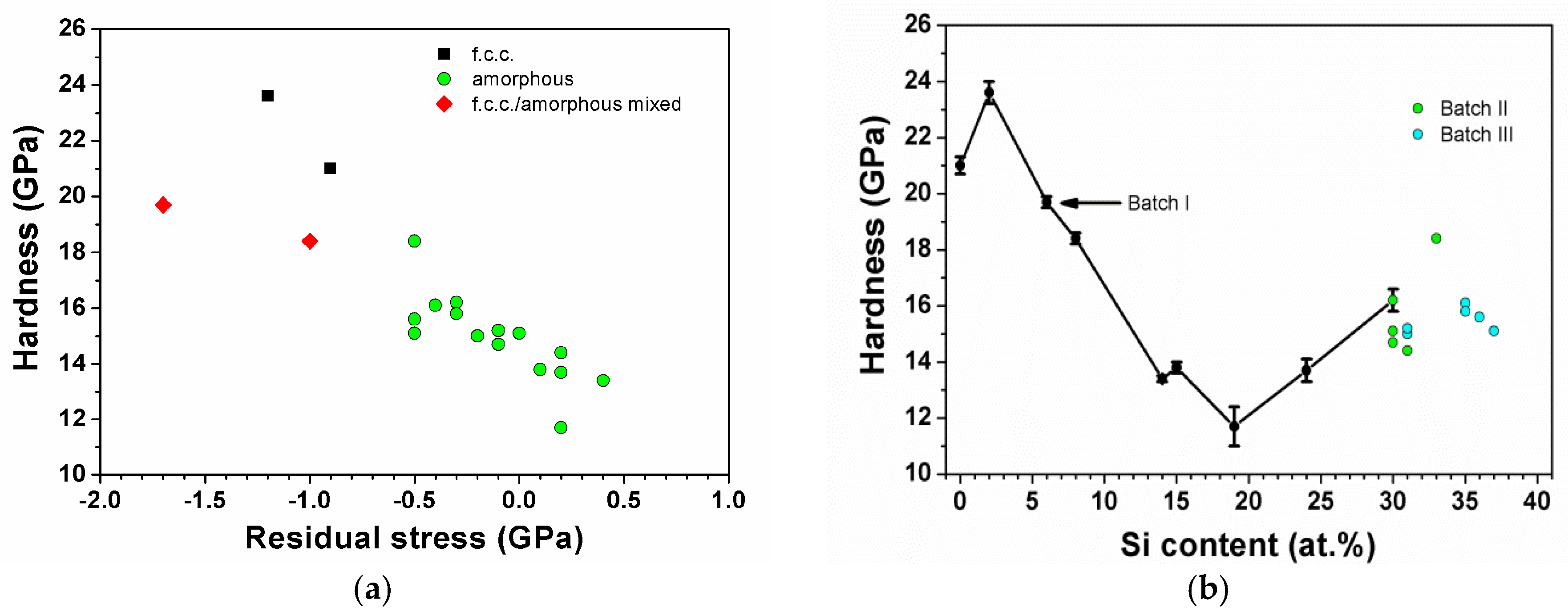

| Sample | Sputtering Power (W) | N2 Ratio | R 1 | Time | Chemical Composition (at.%) | T 2 | H 3 | E 4 | Residual Stress | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WZr | WSi | (rpm) | (min) | Zr | Si | N | O | (nm) | (GPa) | (GPa) | (GPa) | ||

| Batch I | |||||||||||||

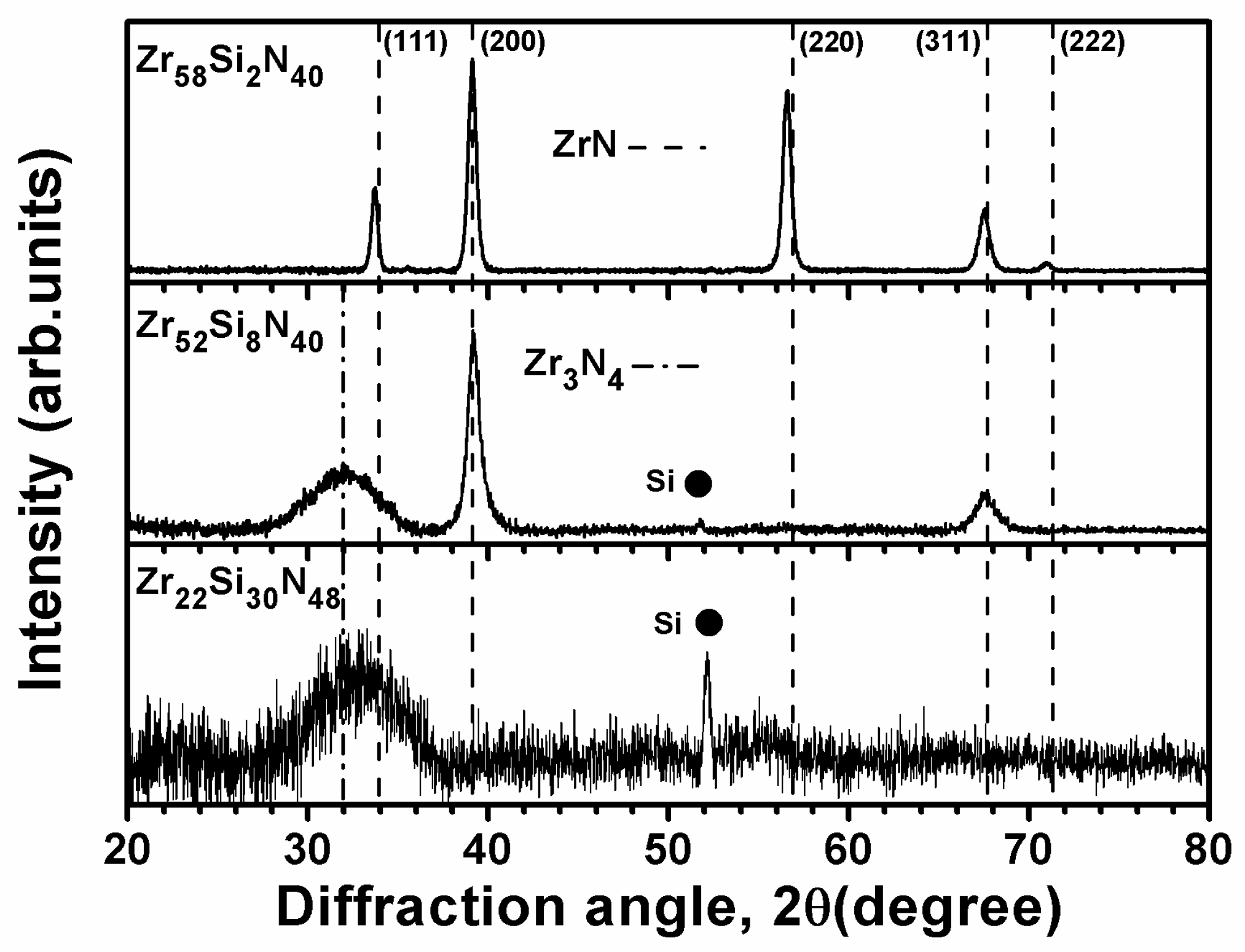

| Zr60N40 | 300 | 0 | 0.4 | 5 | 60 | 57.9 ± 0.8 | – | 38.8 ± 0.8 | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 820 | 21.0 ± 0.3 | 248 ± 6 | –0.9 ± 0.2 |

| Zr58Si2N40 | 290 | 10 | 0.4 | 5 | 60 | 56.9 ± 1.0 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 39.0 ± 1.2 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 860 | 23.6 ± 0.4 | 267 ± 4 | –1.2 ± 0.1 |

| Zr54Si6N40 | 280 | 20 | 0.4 | 5 | 70 | 53.5 ± 0.7 | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 39.3 ± 1.0 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 680 | 19.7 ± 0.2 | 204 ± 3 | –1.7 ± 0.1 |

| Zr52Si8N40 | 270 | 30 | 0.4 | 5 | 70 | 51.2 ± 1.4 | 8.1 ± 0.1 | 39.7 ± 1.7 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 700 | 18.4 ± 0.2 | 207 ± 2 | –1.0 ± 0.3 |

| Zr44Si14N42 | 235 | 65 | 0.4 | 5 | 70 | 43.8 ± 1.1 | 13.7 ± 0.3 | 41.5 ± 1.3 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 740 | 13.4 ± 0.1 | 191 ± 4 | 0.4 ± 0.2 |

| Zr35Si15N50 | 225 | 75 | 0.4 | 5 | 70 | 34.3 ± 0.7 | 14.7 ± 0.3 | 49.3 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 811 | 13.8 ± 0.2 | 187 ± 3 | 0.1 ± 0.3 |

| Zr34Si19N47 | 200 | 100 | 0.4 | 5 | 80 | 33.9 ± 0.4 | 18.8 ± 0.4 | 45.9 ± 0.8 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 940 | 11.7 ± 0.7 | 148 ± 5 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| Zr28Si24N48 | 150 | 150 | 0.4 | 5 | 90 | 28.0 ± 0.5 | 23.8 ± 0.3 | 47.2 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 840 | 13.7 ± 0.4 | 196 ± 2 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| Zr22Si30N48 | 100 | 100 | 0.4 | 5 | 150 | 21.6 ± 0.2 | 29.4 ± 0.3 | 48.2 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 910 | 16.2 ± 0.4 | 217 ± 4 | –0.3 ± 0.0 |

| Batch II | |||||||||||||

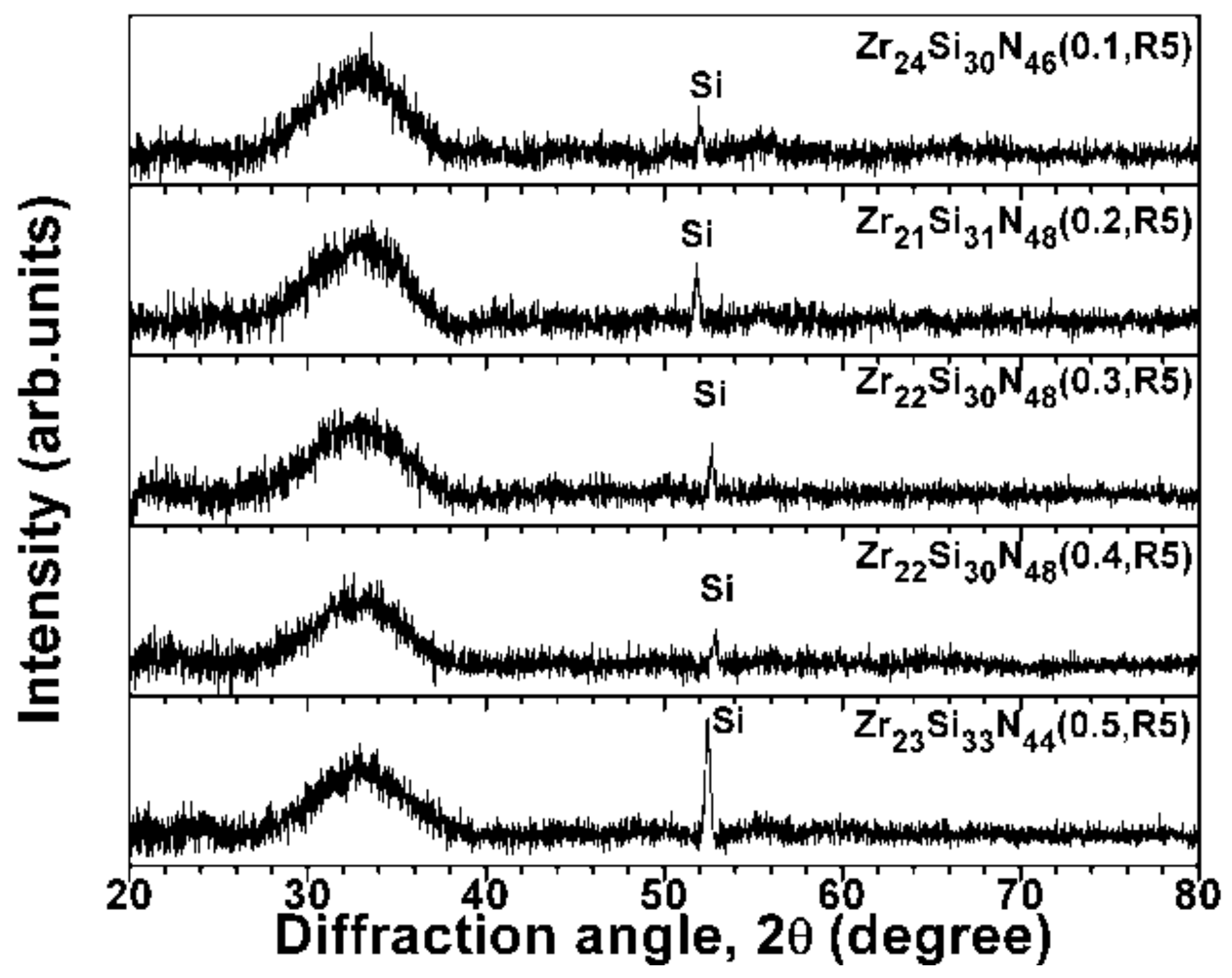

| Zr24Si30N46 | 100 | 100 | 0.1 | 5 | 100 | 23.4 ± 0.3 | 30.1 ± 0.2 | 45.7 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1080 | 14.7 ± 0.4 | 210 ± 5 | –0.1 ± 0.1 |

| Zr21Si31N48 | 100 | 100 | 0.2 | 5 | 120 | 20.8 ± 0.2 | 30.4 ± 0.3 | 47.8 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1050 | 14.4 ± 0.4 | 209 ± 7 | 0.2 ± 0.2 |

| Zr22Si30N48 | 100 | 100 | 0.3 | 5 | 140 | 21.7 ± 0.1 | 30.3 ± 0.3 | 47.2 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 1010 | 15.1 ± 0.4 | 215 ± 5 | 0.0 ± 0.1 |

| Zr22Si30N48 | 100 | 100 | 0.4 | 5 | 150 | 21.6 ± 0.2 | 29.4 ± 0.3 | 48.2 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 910 | 16.2 ± 0.4 | 217 ± 4 | –0.3 ± 0.0 |

| Zr23Si33N44 | 100 | 100 | 0.5 | 5 | 180 | 22.5 ± 0.3 | 32.6 ± 0.7 | 43.8 ± 0.9 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 920 | 18.4 ± 0.4 | 237 ± 5 | –0.5 ± 0.1 |

| Batch III | |||||||||||||

| Zr20Si36N44 | 100 | 100 | 0.4 | 1 | 150 | 20.3 ± 0.4 | 35.3 ± 0.3 | 43.4 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 950 | 15.6 ± 0.3 | 212 ± 6 | –0.5 ± 0.3 |

| Zr24Si31N45 | 100 | 100 | 0.4 | 3 | 150 | 23.6 ± 0.3 | 31.0 ± 0.5 | 44.4 ± 1.0 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1033 | 15.0 ± 0.5 | 208 ± 5 | –0.2 ± 0.1 |

| Zr24Si31N45 | 100 | 100 | 0.4 | 7 | 150 | 23.5 ± 0.3 | 30.8 ± 0.4 | 44.6 ± 0.8 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1040 | 15.2 ± 0.2 | 205 ± 7 | –0.1 ± 0.1 |

| Zr20Si35N45 | 100 | 100 | 0.4 | 10 | 150 | 19.8 ± 0.3 | 34.7 ± 0.2 | 44.6 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 920 | 16.1 ± 0.2 | 206 ± 4 | –0.4 ± 0.3 |

| Zr20Si37N43 | 100 | 100 | 0.4 | 20 | 150 | 20.2 ± 0.4 | 36.2 ± 0.4 | 42.7 ± 0.8 | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 905 | 15.1 ± 0.2 | 194 ± 5 | –0.5 ± 0.1 |

| Zr21Si35N44 | 100 | 100 | 0.4 | 30 | 150 | 20.6 ± 0.5 | 34.5 ± 0.8 | 43.7 ± 1.2 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 890 | 15.8 ± 0.2 | 211 ± 6 | –0.3 ± 0.2 |

| Sample | Binding Energy (eV) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zr3d 5/2 | Si2p | N1s | |||||

| ZrN | Zr3N4 | Si3N4 | Free Si | ZrN | Zr3N4 | Si3N4 | |

| Zr60N40 | 179.55 ± 0.06 | 181.39 ± 0.05 | – | – | 397.05 ± 0.03 | 396.20 ± 0.05 | – |

| Zr58Si2N40 | 179.30 ± 0.03 | 181.61 ± 0.02 | – | – | 396.87 ± 0.01 | 396.06 ± 0.05 | 398.58 ± 0.16 |

| Zr53Si8N39 | 179.14 ± 0.04 | 181.09 ± 0.06 | 100.68 ± 0.08 | 98.92 ± 0.48 | 396.90 ± 0.01 | 396.03 ± 0.01 | 398.36 ± 0.29 |

| Zr44Si14N42 | 179.51 ± 0.01 | 180.93 ± 0.02 | 100.67 ± 0.06 | 98.53 ± 0.15 | 396.98 ± 0.01 | 396.12 ± 0.10 | 398.53 ± 0.10 |

| Zr34Si19N47 | 179.44 ± 0.00 | 180.75 ± 0.03 | 100.68 ± 0.02 | 98.41 ± 0.09 | 396.94 ± 0.05 | 396.08 ± 0.02 | 398.31 ± 0.18 |

| Zr28Si24N48 | 179.87 ± 0.07 | 181.03 ± 0.04 | 100.89 ± 0.05 | 98.74 ± 0.06 | 397.04 ± 0.03 | 396.18 ± 0.03 | 398.21 ± 0.17 |

| Zr22Si30N48 | 180.22 ± 0.03 | 181.01 ± 0.06 | 100.59 ± 0.13 | 98.51 ± 0.11 | 396.97 ± 0.11 | 396.13 ± 0.12 | 397.94 ± 0.18 |

| Sample | Surface Roughness (nm) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycles | 0 | 250 | 250 | 400 | 400 | 500 | 500 | 750 | |

| Position | Inner 1 | Outer 2 | Inner | Outer | Inner | Outer | Outer | ||

| Zr60N40/Si | 1.0 ± 0.0 | F 3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Zr58Si2N40/Si | 0.9 ± 0.1 | F | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Zr53Si8N39/Si | 0.3 ± 0.0 | F | 0.4 ± 0.1 | – | – | – | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 11 ± 0.5 | |

| Zr44Si14N42/Si | 0.5 ± 0.0 | F | 0.7 ± 0.0 | – | – | – | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | |

| Zr35Si15N50/Si | 0.6 ± 0.0 | F | 0.7 ± 0.0 | – | – | – | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | |

| Zr34Si19N47/Si | 0.5 ± 0.0 | F | 0.6 ± 0.0 | – | – | – | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | |

| Zr28Si24N48/Si | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | – | – | F | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | |

| Zr22Si29N49/Ti/WC | 1.5 ± 0.0 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.0 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | F | 1.8 ± 0.1 | – | |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, L.-C.; Zheng, Y.-Z.; Chen, Y.-I.; Chang, S.-C.; Liu, B.-W. Bonding Characteristics and Chemical Inertness of Zr–Si–N Coatings with a High Si Content in Glass Molding. Coatings 2018, 8, 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings8050181

Chang L-C, Zheng Y-Z, Chen Y-I, Chang S-C, Liu B-W. Bonding Characteristics and Chemical Inertness of Zr–Si–N Coatings with a High Si Content in Glass Molding. Coatings. 2018; 8(5):181. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings8050181

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Li-Chun, Yu-Zhe Zheng, Yung-I Chen, Shan-Chun Chang, and Bo-Wei Liu. 2018. "Bonding Characteristics and Chemical Inertness of Zr–Si–N Coatings with a High Si Content in Glass Molding" Coatings 8, no. 5: 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings8050181

APA StyleChang, L.-C., Zheng, Y.-Z., Chen, Y.-I., Chang, S.-C., & Liu, B.-W. (2018). Bonding Characteristics and Chemical Inertness of Zr–Si–N Coatings with a High Si Content in Glass Molding. Coatings, 8(5), 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings8050181