Adhesion Improvement Between Cu-Etched Commercial Polyimide/Cu Foils and Biopolymers for Sustainable In-Mold Electronics

Abstract

1. Introduction

- drying the PI in an oven;

- polydopamine (PDA) coating;

- polydopamine coating followed by thermal treatment at 50 °C in vacuum;

- oxygen plasma surface activation;

- treatment of the PI with a silane adhesion promoter;

- lamination of a TPU adhesive tie layer.

2. Materials

3. Methods

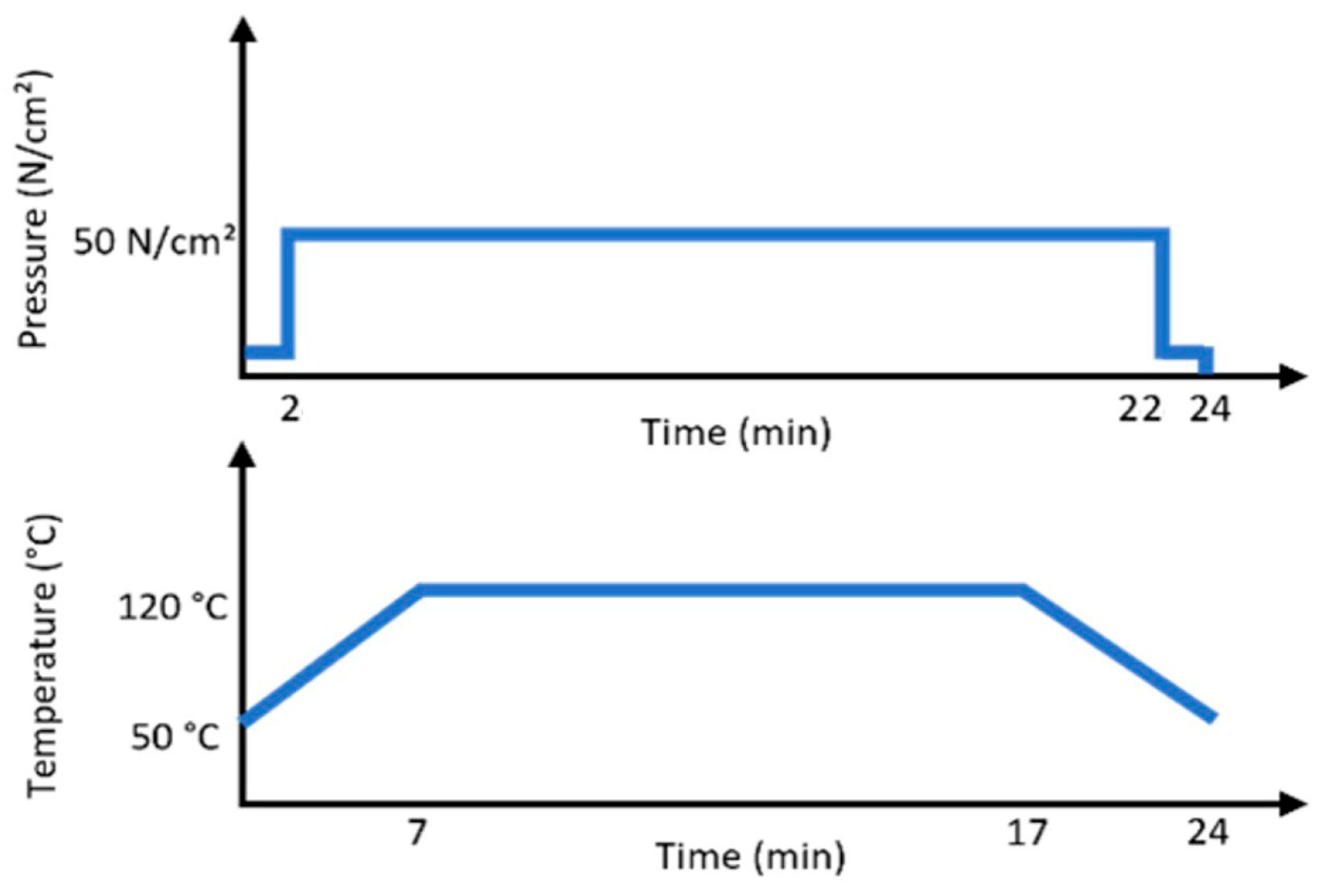

3.1. Sample Preparation

3.2. Surface Modifications

- drying in an oven at 120 °C,

- deposition of PDA,

- deposition of PDA followed by thermal treatment at 50 °C in vacuum,

- mild oxygen plasma,

- surface modification with APTES.

3.2.1. Drying

3.2.2. PDA Coating

3.2.3. PDA Coating with Thermal Treatment in Vacuum

3.2.4. Plasma Activation

3.2.5. APTES Solution

3.2.6. TPU Lamination

3.3. Surface Characterization

3.3.1. Static Water Contact Angle

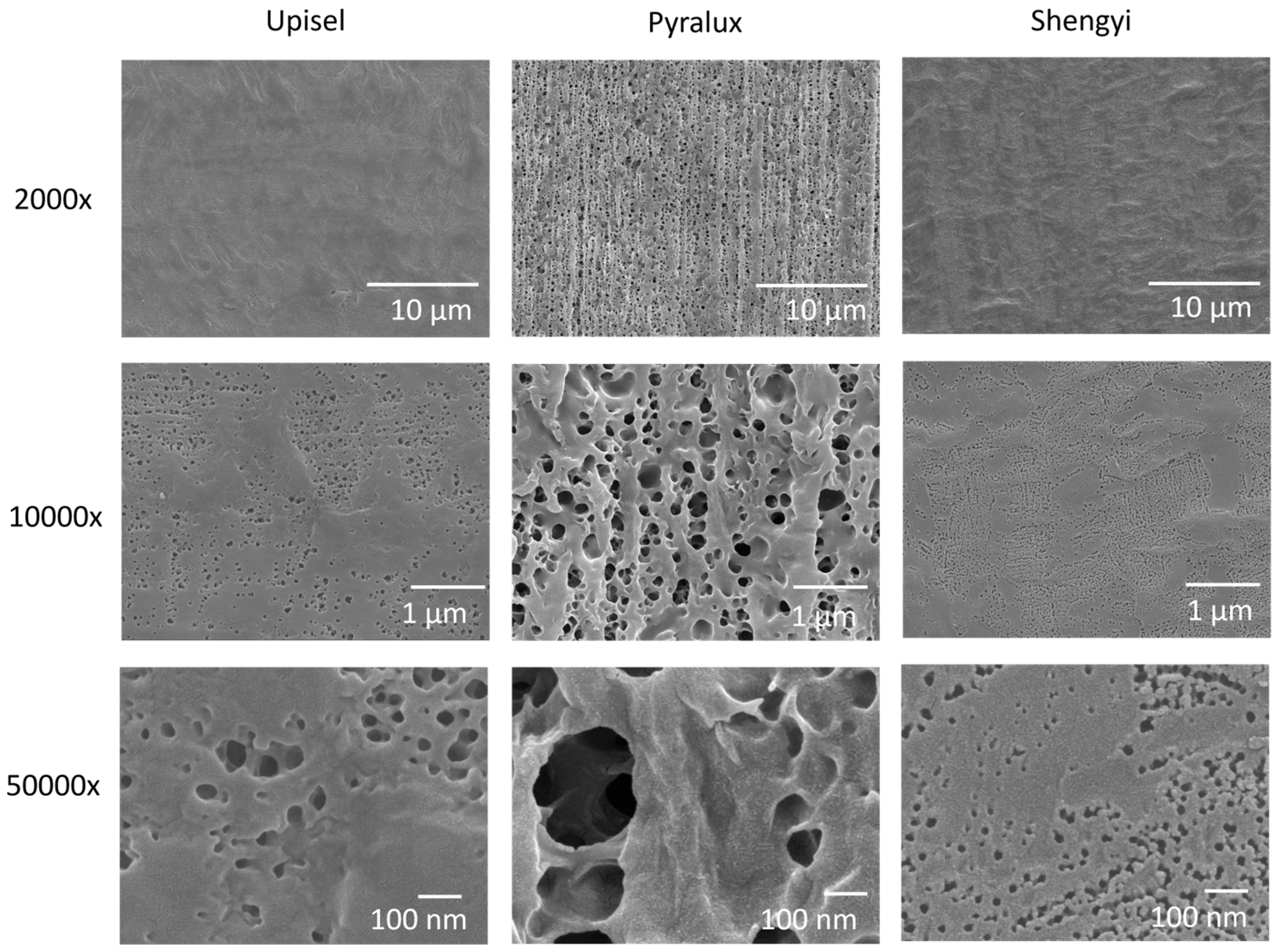

3.3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy

3.3.3. Attenuated Total Reflection Fourier Transformed Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR)

3.3.4. Optical Profilometry

3.3.5. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy

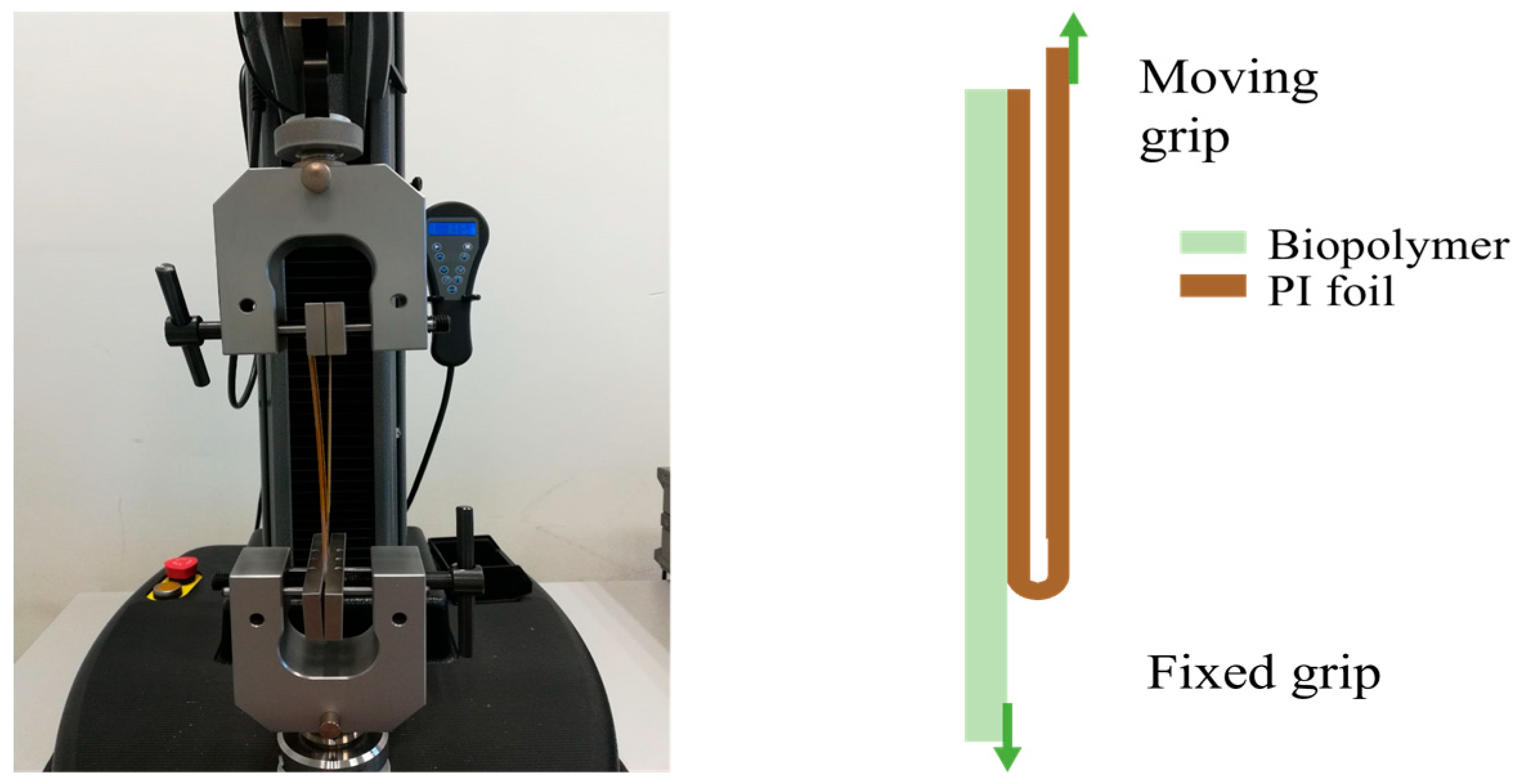

3.3.6. Peel Test

3.4. Statistical Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Introduction

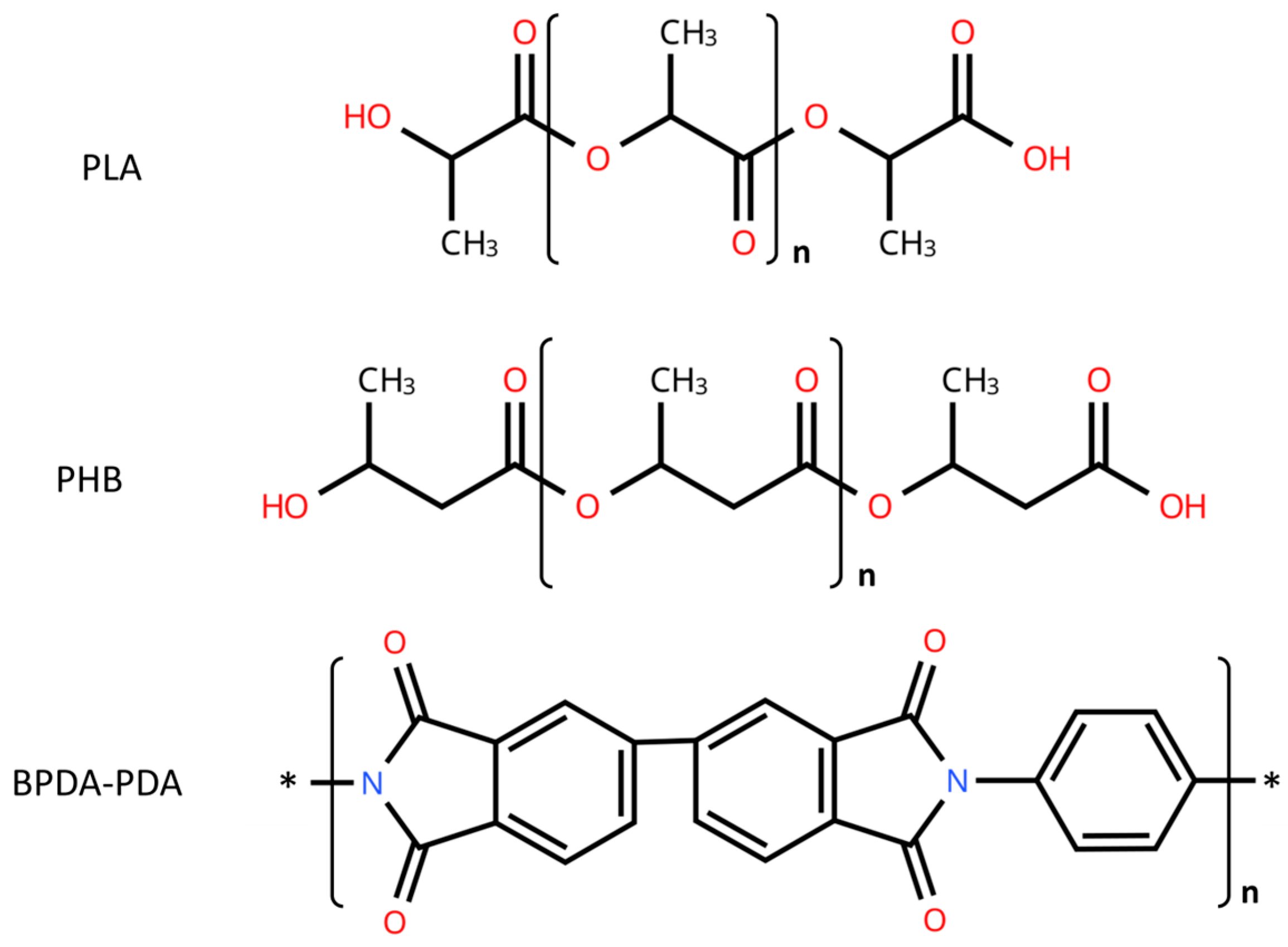

4.2. Infrared Analyses of the Pristine Cu Etched Surfaces

4.3. Surface Characterization of the Surface Modifications

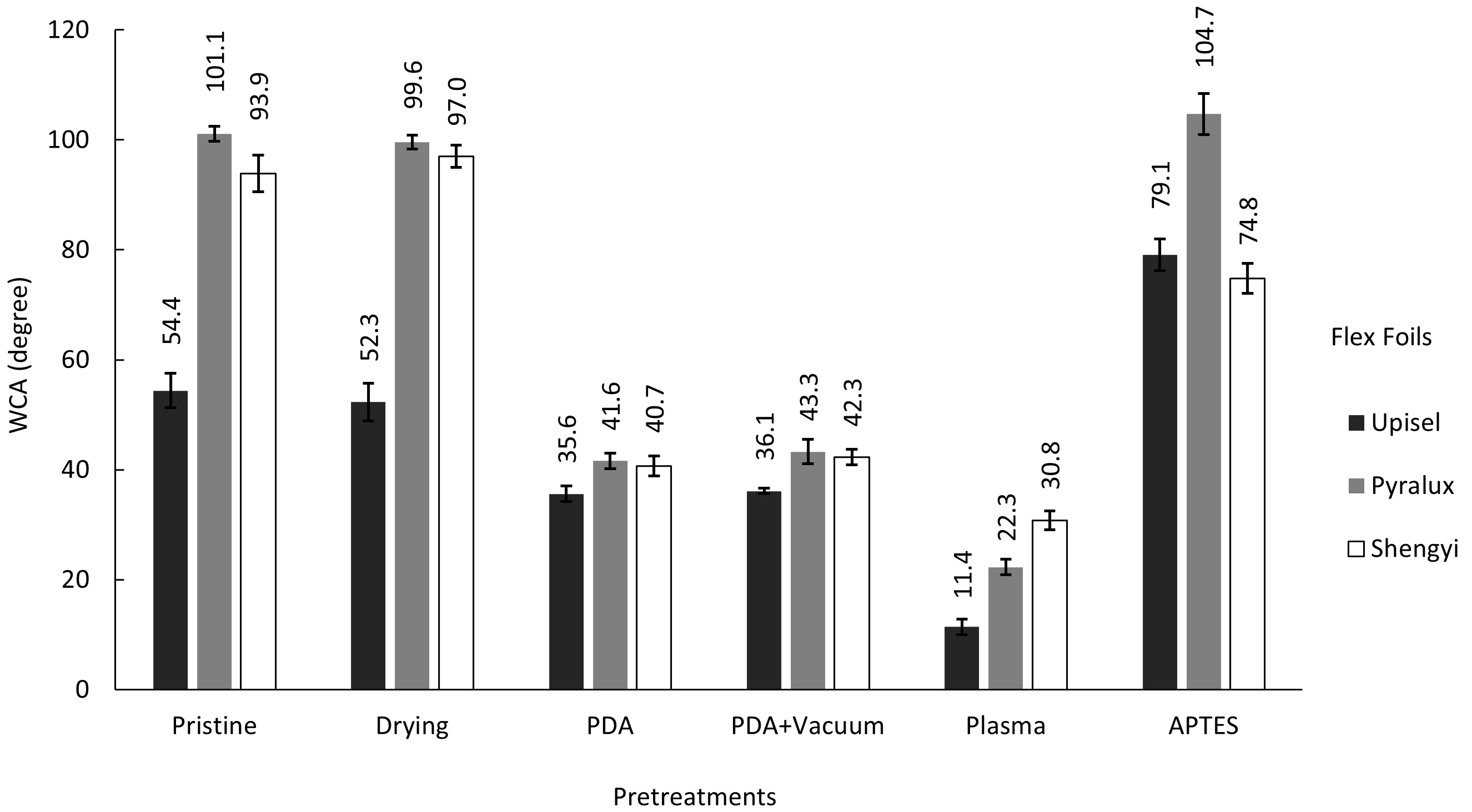

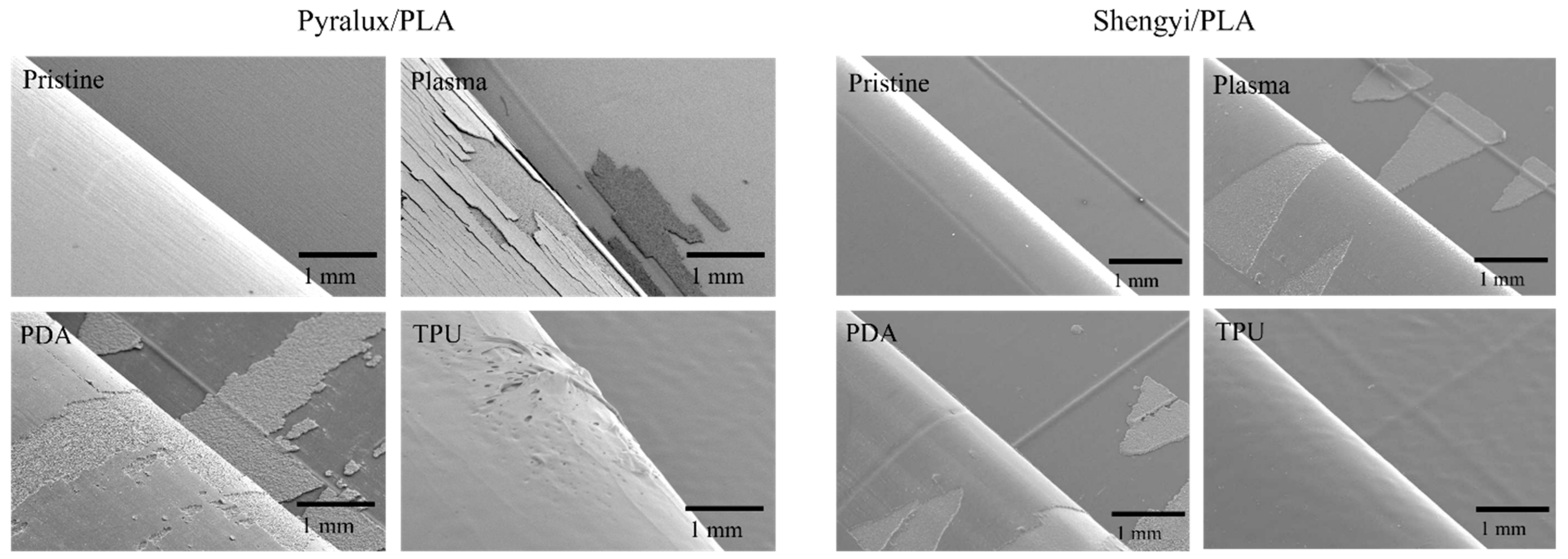

4.3.1. Roughness, Surface Morphology, and Water Contact Angle

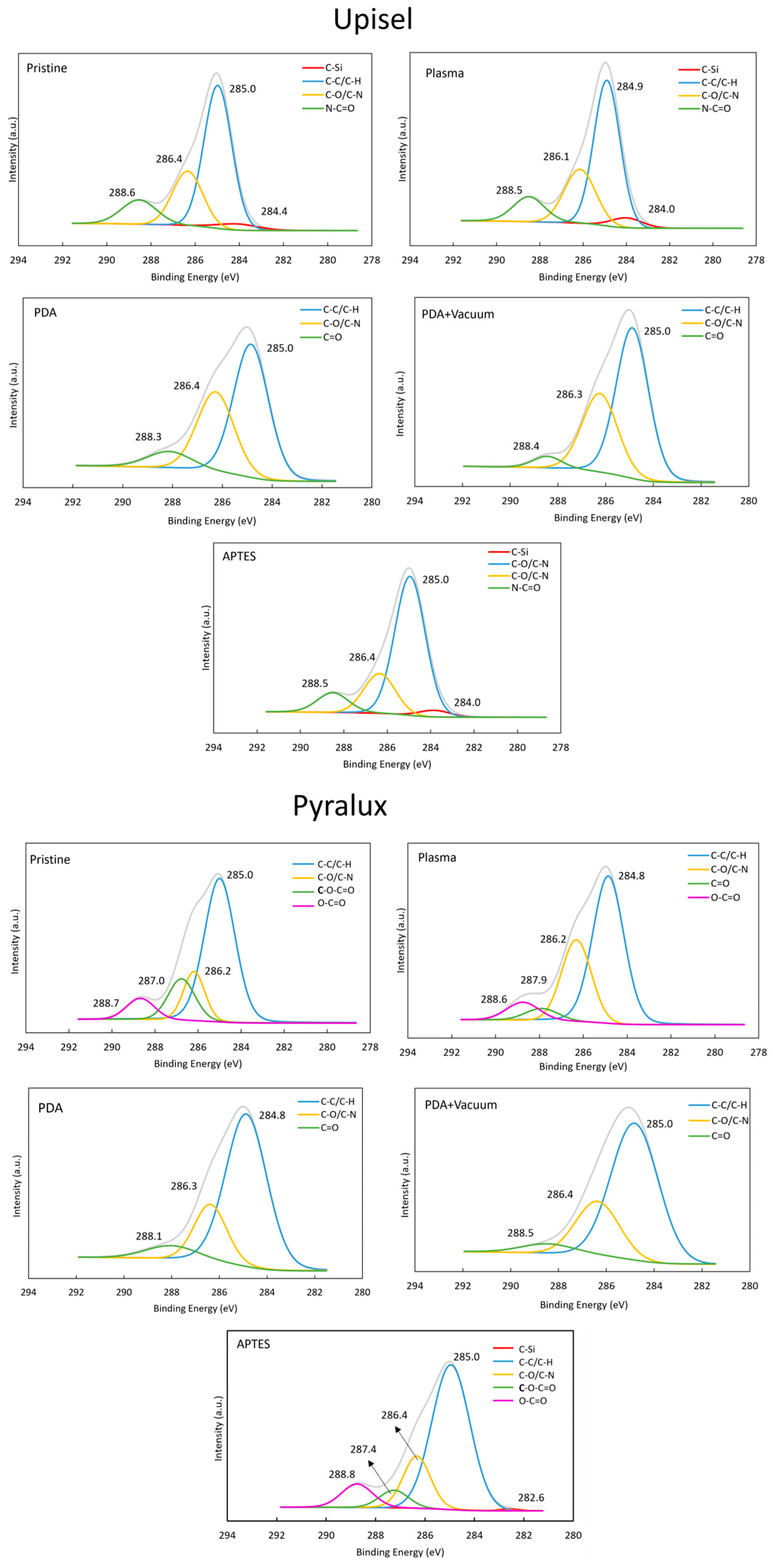

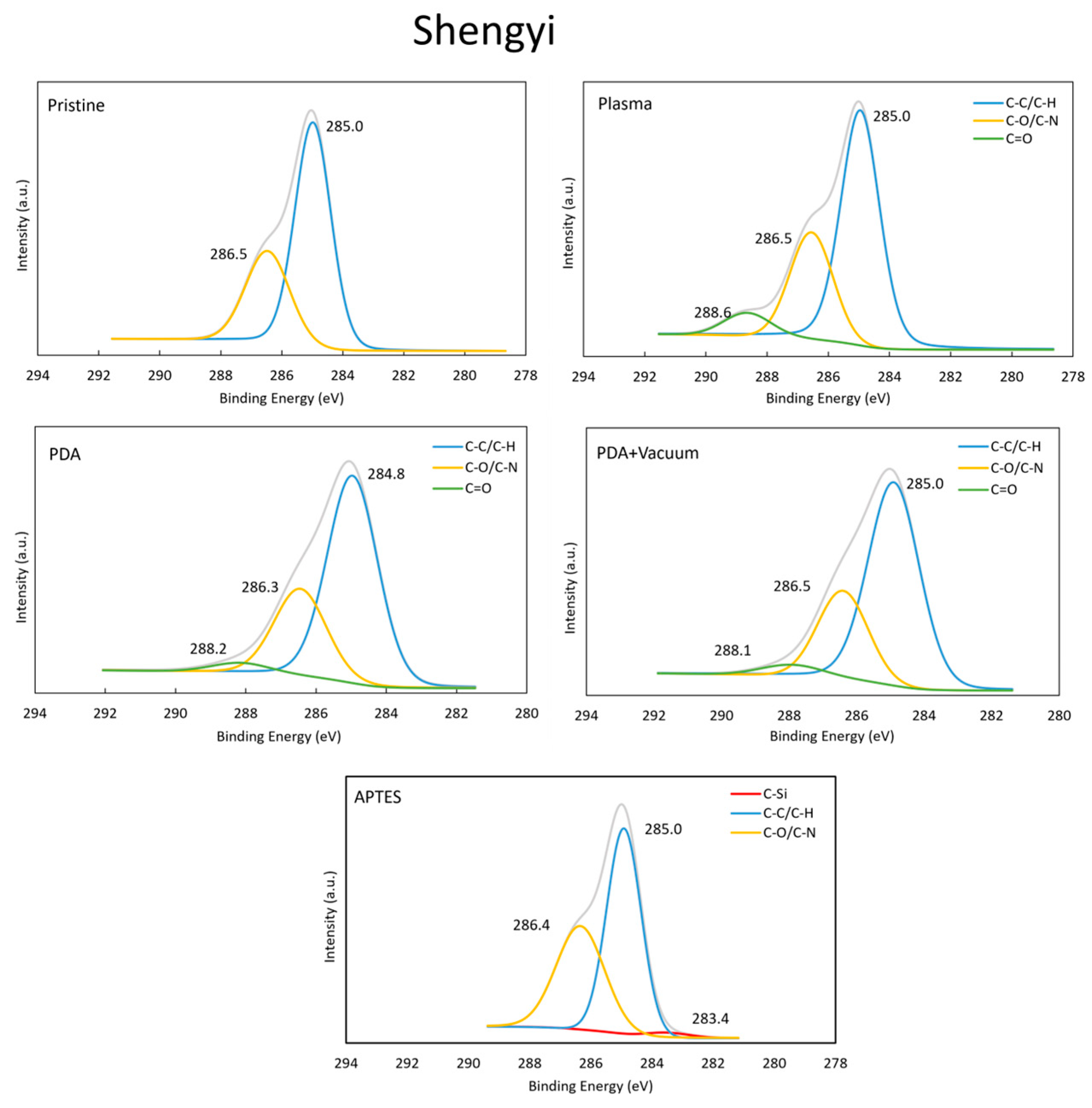

4.3.2. Evaluation of the Surface Chemical Compositions (XPS)

| Si Reference | C (at. %) | O (at. %) | N (at. %) | Si (at. %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDA | 63.1 ± 0.3 | 21.9 ± 0.2 | 7.6 ± 0.6 | 7.4 ± 0.6 |

| PDA + Vacuum | 59.9 ± 1.4 | 22.4 ± 0.4 | 7.3 ± 0.5 | 10.3 ± 1.1 |

4.3.3. Surface Characterization Conclusion

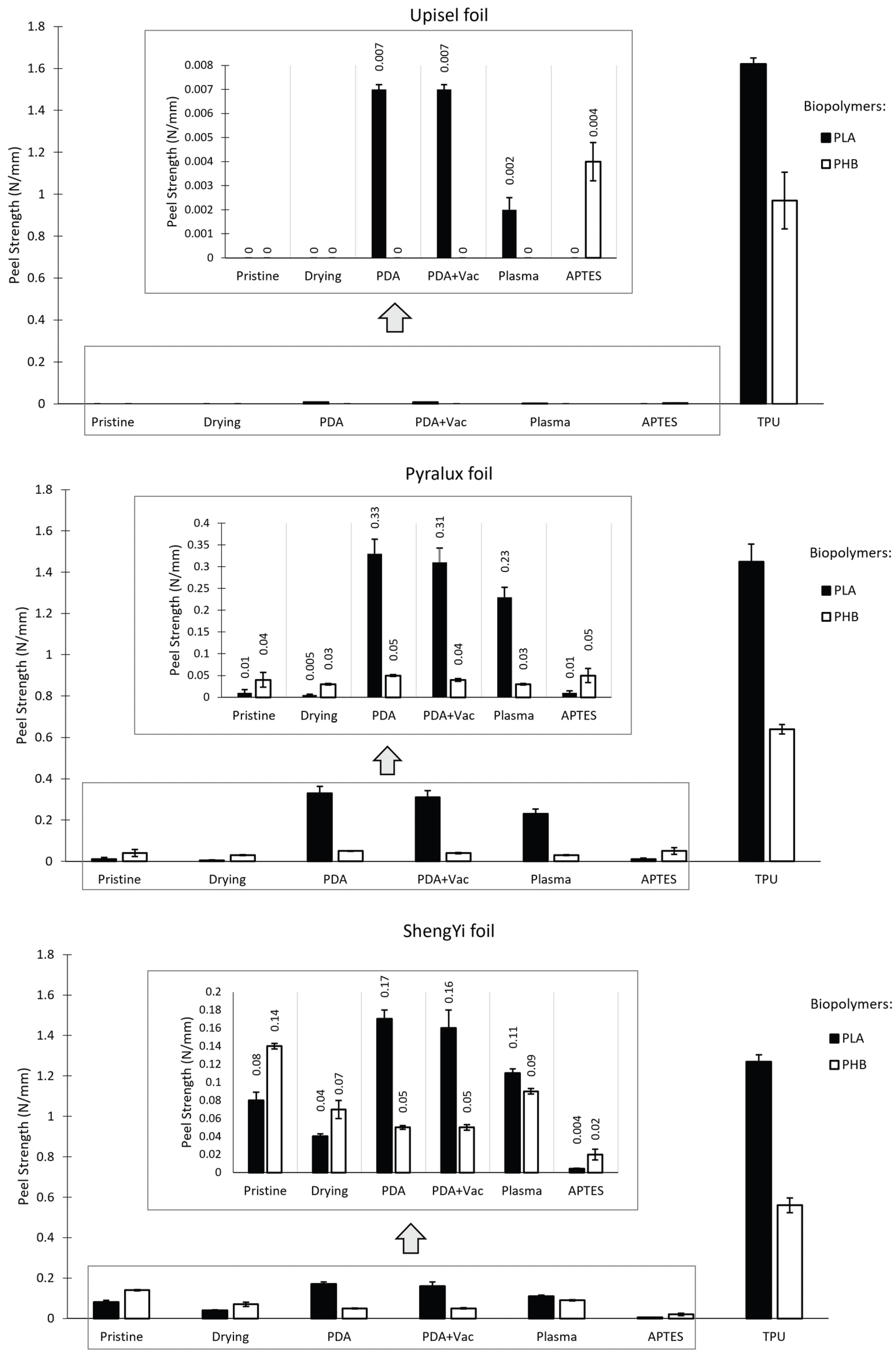

4.4. Adhesive Strength

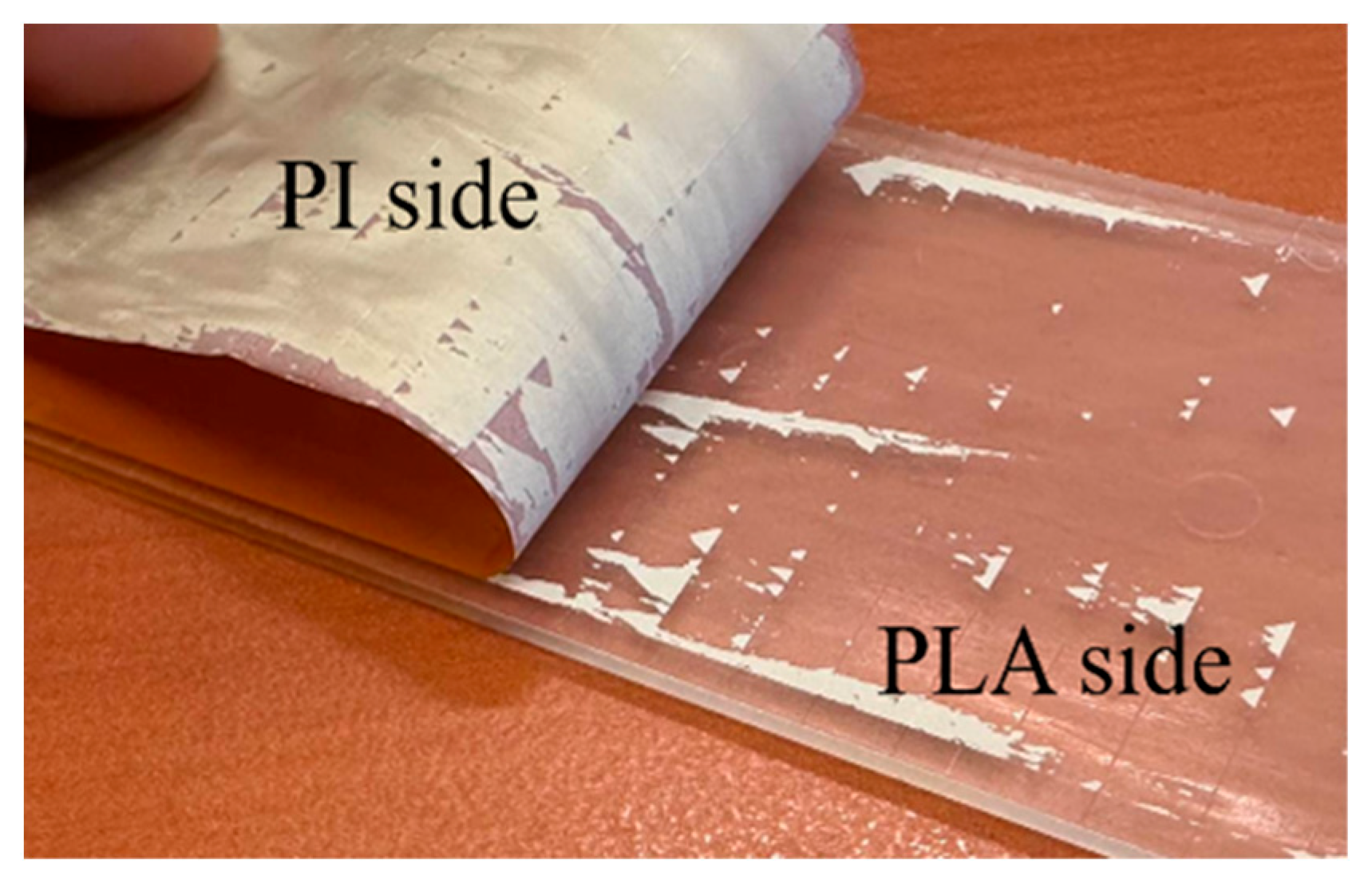

4.4.1. Adhesive Strength Measurements

4.4.2. Loci of Failure

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beltrão, M.; Duarte, F.M.; Viana, J.C.; Paulo, V. A Review on In-Mold Electronics Technology. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2022, 62, 967–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakr, M.; Bossuyt, F.; Vanfleteren, J. The Integration of Electronic Circuits in Plastics Using Injection Technologies: A Literature Review. Flex. Print. Electron. 2022, 7, 023001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusanen, O.; Simula, T.; Niskala, P.; Lindholm, V.; Heikkinen, M. Injection Molded Structural Electronics Brings Surfaces to Life. In Proceedings of the 2019 22nd European Microelectronics and Packaging Conference & Exhibition (EMPC), Pisa, Italy, 16–19 September 2019; Volume 2019, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abalansa, S.; El Mahrad, B.; Icely, J.; Newton, A. Electronic Waste, an Environmental Problem Exported to Developing Countries: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santato, C.; Alarco, P.J. The Global Challenge of Electronics: Managing the Present and Preparing the Future. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2022, 7, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazlali, Z.; Schaubroeck, D.; Cauwe, M.; Ugduler, S.; Van Laere, T.; Manhaeghe, D.; De Meester, S.; Cardon, L.; Vanfleteren, J. Eco-Friendly In-Mold Electronics Using Polylactic Acid. In Proceedings of the 2024 Electronics Goes Green 2024+ (EGG), Berlin, Germany, 18–20 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshood, T.D.; Nawanir, G.; Mahmud, F.; Mohamad, F.; Ahmad, M.H.; AbdulGhani, A. Sustainability of Biodegradable Plastics: New Problem or Solution to Solve the Global Plastic Pollution? Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 5, 100273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.european-bioplastics.org/bioplastics/ (accessed on 22 April 2023).

- Ramesh Kumar, S.; Shaiju, P.; O’Connor, K.E. Bio-Based and Biodegradable Polymers—State-of-the-Art, Challenges and Emerging Trends. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2020, 21, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taib, N.A.A.B.; Rahman, M.R.; Huda, D.; Kuok, K.K.; Hamdan, S.; Bakri, M.K.B.; Julaihi, M.R.M.B.; Khan, A. A Review on Poly Lactic Acid (PLA) as a Biodegradable Polymer; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; Volume 80, ISBN 0123456789. [Google Scholar]

- De Luca, S.; Milanese, D.; Gallichi-Nottiani, D.; Cavazza, A.; Sciancalepore, C. Poly (Lactic Acid) and Its Blends for Packaging Application: A Review. Clean Technol. 2023, 5, 1304–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhvi, M.S.; Zinjarde, S.S.; Gokhale, D.V. Polylactic Acid: Synthesis and Biomedical Applications. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 127, 1612–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getachew, A.; Woldesenbet, F. Production of Biodegradable Plastic by Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) Accumulating Bacteria Using Low Cost Agricultural Waste Material. BMC Res. Notes 2016, 9, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, B.; Fournet, M.B.; McDonald, P.; Mojicevic, M. Production of Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) and Factors Impacting Its Chemical and Mechanical Characteristics. Polymers 2020, 12, 2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddah, H.A. Polypropylene as a Promising Plastic: A Review. Am. J. Polym. Sci. 2016, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassajfar, M.N.; Deviatkin, I.; Leminen, V.; Horttanainen, M. Alternative Materials for Printed Circuit Board Production: An Environmental Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goosey, M. Polymers in Printed Circuit Board (PCB) and Related Advanced Interconnect Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; ISBN 9789048140183. [Google Scholar]

- Diaham, S. Polyimide in Electronics: Applications and Processability Overview. Polyim. Electron. Electr. Eng. Appl. 2021, 3, 2020–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakr, M.; Su, Y.; Rezaei, A.; Bossuyt, F.; Vanfleteren, J. Over-Molding of Flexible Polyimide-Based Electronic Circuits. Flex. Print. Electron. 2021, 6, 025007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakr, M.; Su, Y.; Bossuyt, F.; Vanfleteren, J. Effect of Overmolding Process on the Integrity of Electronic Circuits. In Proceedings of the 2019 22nd European Microelectronics and Packaging Conference & Exhibition (EMPC), Pisa, Italy, 16–19 September 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, A. Preparation for Bonding; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 2, ISBN 9783319554112. [Google Scholar]

- Raos, G.; Zappone, B. Polymer Adhesion: Seeking New Solutions for an Old Problem#. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 10617–10644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen-Puc, M.; Schander, A.; Vargasgleason, M.G.; Lang, W. An Assessment of Surface Treatments for Adhesion of Polyimide Thin Films. Polymers 2021, 13, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashayekhi, F.; Bardon, J.; Westermann, S.; Addiego, F. Adhesion Optimization between Incompatible Polymers through Interfacial Engineering. Polymers 2021, 13, 4273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafkopoulos, G.; Karakurt, E.; Martinho, R.P.; Duvigneau, J.; Vancso, G.J. Engineering of Adhesion at Metal—Poly (Lactic Acid) Interfaces by Poly (Dopamine): The Effect of the Annealing Temperature. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 5370–5380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazlali, Z.; Schaubroeck, D.; Cauwe, M.; Cardon, L.; Bauwens, P.; Vanfleteren, J. Polylactic Acid and Polyhydroxybutyrate as Printed Circuit Board Substrates: A Novel Approach. Processes 2025, 13, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Dellatore, S.M.; Miller, W.M.; Messersmith, P.B. Mussel-Inspired Surface Chemistry for Multifunctional Coatings. Science 2007, 318, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öztoprak, N.; Mehmet, G.; Murat, G. Characterization of Interface, Tensile—Shear, and Vibration Performance of AA2024—T351/PP Composite Stepped—Lap Joint. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 138, 5537–5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaham, S.; Locatelli, M.L.; Lebey, T.; Malec, D. Thermal Imidization Optimization of Polyimide Thin Fi Lms Using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy and Electrical Measurements. Thin Solid Films 2011, 519, 1851–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaham, S.; Locatelli, M.; Khazaka, R. BPDA-PDA Polyimide: Synthesis, Characterizations, Aging and Semiconductor Device Passivation. In High Performance Polymers-Polyimides Based-From Chemistry to Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y.; Dong, J.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Q. Preparation of High-Performance Polyimide Fibers via a Partial Pre-Imidization Process. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 3619–3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhland, K.; Haase, N.; Fischer, A. Detailed Examination of Nitrile Stretching Vibrations Relevant for Understanding the Behavior of Thermally Treated Polyacrylonitrile. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134, 44936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, M.; Kong, H.; Ding, X.; Zhang, L.; Yu, M. Effect of Graphene Oxide Coatings on the Structure of Polyacrylonitrile Fi Bers during Pre-Oxidation. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 28146–28152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.R.; Liedberg, B. Infrared Reflection-Absorption Spectroscopy of Polyacrylonitrile on Copper and Aluminium Surfaces. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 1988, 26, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.Z.; Shanahan, M.E.R. Irreversible Effects of Hygrothermal Aging on DGEBA/DDA Epoxy Resin. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1997, 69, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustata, F.; Tudorachi, N.; Rosu, D. Composites: Part B Curing and Thermal Behavior of Resin Matrix for Composites Based on Epoxidized Soybean Oil/Diglycidyl Ether of Bisphenol A. Compos. Part B Eng. 2011, 42, 1803–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, C.; Jian, R.; Liu, D.; Liu, Y. Enhanced Fl Ame Retardancy of DGEBA Epoxy Resin with a Novel Bisphenol-A Bridged Cyclotriphosphazene. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2017, 144, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, R.; Li, H.; Zhu, Y. Terahertz and FTIR Spectroscopy of ‘Bisphenol A’. J. Mol. Struct. 2014, 1059, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wu, Q.; Li, S.; Wu, P. Study of the Infrared Spectral Features of an Epoxy Curing Mechanism. Appl. Spectrosc. 2008, 62, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, C.F., Jr. Printed Circuits Handbook; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 0071510796. [Google Scholar]

- Zangmeister, R.A.; Morris, T.A.; Tarlov, M.J. Characterization of Polydopamine Thin Films Deposited at Short Times by Autoxidation of Dopamine. Langmuir 2013, 29, 8619–8628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, K.; Singh, N.; Yadav, J.; Nayak, J.M.; Sahoo, S.K.; Lata, J.; Chand, D.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, R. Polydopamine films change their physicochemical and antimicrobial properties with a change in reaction conditions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 5744–5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zhu, L.; Zhu, L.; Zhu, B.; Xu, Y. Surface Characteristics of a Self-Polymerized Dopamine Coating Deposited on Hydrophobic Polymer Films. Langmuir 2011, 27, 14180–14187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, D.; Grosu, I.; Filip, C. Applied Surface Science How Thick, Uniform and Smooth Are the Polydopamine Coating Layers Obtained under Different Oxidation Conditions? An in-Depth AFM Study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 597, 153680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbassi, F.; Morra, M.; Occhiello, E. Polymer Surfaces from Physics to Technology. IEEE Electr. Insul. Mag. 1999, 15, 36–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.H.; Patel, K.D.; Patel, N.A.; Patel, D.Y.; Chauhan, K.V. Study the Influence of Deposition Parameter on Structure & Wettability Properties of Chromium Oxide Coating Deposited by Reactive RF Magnetron Sputtering on GFRP Composite. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 50, 2381–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundriyal, P.; Pandey, M.; Bhattacharya, S. Plasma-Assisted Surface Alteration of Industrial Polymers for Improved Adhesive Bonding. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2020, 101, 102626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, D.; Vercammen, Y.; Van Vaeck, L.; Vanderleyden, E.; Dubruel, P.; Vanfleteren, J. Surface Characterization and Stability of an Epoxy Resin Surface Modified with Polyamines Grafted on Polydopamine. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 303, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobeira, R.; Philips, C.; Declercq, H.; Cools, P.; De Geyter, N.; Cornelissen, R.; Morent, R. Effects of Different Sterilization Methods on the Physico-Chemical and Bioresponsive Properties of Plasma-Treated Polycaprolactone Films. Biomed. Mater. 2017, 12, 015017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, H.; Hanks, T.W. Polydopamine: A Bioinspired Adhesive and Surface Modification Platform. Polym. Int. 2022, 71, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Bu, J.; Liu, W.; Niu, H.; Qi, S.; Tian, G.; Wu, D. Surface Modification of Polyimide Fibers by Oxygen Plasma Treatment and Interfacial Adhesion Behavior of a Polyimide Fiber/Epoxy Composite. Sci. Eng. Compos. Mater. 2017, 24, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Tong, H.; Liu, C.; Ye, X.; Yuan, X.; Xu, J.; Li, H. Activation of Polyimide by Oxygen Plasma for Atomic Layer Deposition of Highly Compact Titanium Oxide Coating. Nanotechnology 2024, 35, 265704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Properties | PP | PE | PLA | PHB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density (g/cm3) | 0.91–0.94 | 0.9–0.97 | 1.25 | 1.23 |

| Tensile Strength (MPa) | 20–40 | 10–30 | 21–60 | 20–40 |

| Elongation at Break (%) | 3–700 | 90–700 | 3–30 | 5–8 |

| Young’s Modulus (GPa) | 1.5–2 | 0.2–1.0 | 3.0–4.0 | 3–3.5 |

| Melting Point (°C) | 160–170 | 105–135 | 150–180 | 165–175 |

| Flexible Foil Layers | Upisel-N SR1220 | Pyralux FR9120R | Shengyi SF305R |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyimide (PI) | 50 µm | 50 µm | 25 µm |

| Adhesive | No adhesive layer | 25 µm acrylic-based adhesive | 20 µm epoxy-based adhesive |

| Copper (Rolled-annealed) | 18 µm | 35 µm | 18 µm |

| Layer 1. Etched Polyimide Foil | Layer 2. Biopolymer |

|---|---|

| Upisel-N SR1220 | PLA |

| Pyralux FR9120R | PHB |

| Shengyi SF305R |

| PI Foil | Upisel | Pyralux | Shengyi |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine | 203 ± 5 | 334 ± 34 | 304 ± 4 |

| Plasma | 206 ± 5 | 339 ± 32 | 302 ± 4 |

| PDA | 213 ± 6 | 327 ± 8 | 315 ± 12 |

| PDA + Vacuum | 204 ± 7 | 340 ± 25 | 307 ± 7 |

| APTES | 207 ± 5 | 331 ± 29 | 306 ± 5 |

| Upisel Foil | C (at. %) | O (at. %) | N (at. %) | Si (at. %) | Cr (at. %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine | 38.9 ± 1.0 | 45.0 ± 0.8 | 3.7 ± 1.4 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 9.6 ± 0.8 |

| PDA | 72.4 ±0.7 | 20.1 ± 0.5 | 7.3 ± 0.5 | <DL * | <DL |

| PDA + Vacuum | 70.0 ± 0.7 | 21.6 ± 0.4 | 8.2 ± 0.5 | <DL | <DL |

| Plasma | 36.5 ± 1.2 | 47.1 ± 0.6 | 4.6 ± 1.5 | 3.3 ± 0.8 | 8.5 ± 1.1 |

| APTES | 34.9 ± 0.8 | 43.4 ± 1.8 | 5.0 ± 0.7 | 5.6 ± 0.6 | 11.7 ± 2.6 |

| Pyralux Foil (Acrylic) | C (at. %) | O (at. %) | N (at. %) | Si (at. %) | Cr (at. %) | S (at. %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine | 48.7 ± 2.8 | 40.3 ± 1.5 | 4.0 ± 0.8 | <DL * | 4.9 ± 0.4 | 2.0 ± 0.5 |

| PDA | 69.3 ± 0.7 | 23.0 ± 0.4 | 7.4 ± 0.6 | <DL | <DL | <DL |

| PDA + Vacuum | 72.3 ± 0.7 | 21.1 ± 0.5 | 6.5 ± 0.4 | <DL | <DL | <DL |

| Plasma | 37.5 ± 1.4 | 50.0 ± 0.4 | 3.4 ± 0.4 | <DL | 6.9 ± 1.1 | 2.2 ± 0.3 |

| APTES | 50.4 ± 0.4 | 36.8 ± 0.6 | 5.3 ± 1.0 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 4.7 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.3 |

| Shengyi Foil (Epoxy) | C (at. %) | O (at. %) | N (at. %) | Si (at. %) | S (at. %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine | 76.1 ± 0.6 | 21.2 ± 1.0 | 1.3 ± 1.2 | <DL * | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

| PDA | 74.0 ± 0.4 | 19.4 ± 0.2 | 6.3 ± 0.3 | <DL | 0.1 ± 0.1 |

| PDA + Vacuum | 76.3 ± 0.4 | 18.3 ± 0.2 | 5.4 ± 0.2 | <DL | <DL |

| Plasma | 61.0 ± 0.6 | 34.5 ± 0.6 | 3.6 ± 1.0 | <DL | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

| APTES | 71.8 ± 2.4 | 22.5 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 2.3 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.4 |

| PI Foil | Upisel | Pyralux | Shengyi |

|---|---|---|---|

| O/C before plasma | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.3 |

| O/C after plasma | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0.6 |

| Sample | Upisel/PLA | Upisel/PHB | Pyralux/PLA | Pyralux/PHB | Shengyi/PLA | Shengyi/PHB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine | Adhesive | Adhesive | Adhesive | Adhesive | Adhesive | Adhesive |

| Drying | Adhesive | Adhesive | Adhesive | Adhesive | Adhesive | Adhesive |

| PDA | Adhesive | Adhesive | Adhesive/ Cohesive | Adhesive | Adhesive/ Cohesive | Adhesive |

| PDA + Vacuum | Adhesive | Adhesive | Adhesive/ Cohesive | Adhesive | Adhesive/ Cohesive | Adhesive |

| O2 plasma | Adhesive | Adhesive | Adhesive/ Cohesive | Adhesive | Adhesive/ Cohesive | Adhesive |

| APTES | Adhesive | Adhesive | Adhesive | Adhesive | Adhesive | Adhesive |

| TPU | Cohesive | Cohesive | Cohesive | Cohesive | Cohesive | Cohesive |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fazlali, Z.; Schaubroeck, D.; Cauwe, M.; Leus, K.; Morent, R.; De Geyter, N.; Cardon, L.; Bauwens, P.; Vanfleteren, J. Adhesion Improvement Between Cu-Etched Commercial Polyimide/Cu Foils and Biopolymers for Sustainable In-Mold Electronics. Coatings 2025, 15, 1489. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121489

Fazlali Z, Schaubroeck D, Cauwe M, Leus K, Morent R, De Geyter N, Cardon L, Bauwens P, Vanfleteren J. Adhesion Improvement Between Cu-Etched Commercial Polyimide/Cu Foils and Biopolymers for Sustainable In-Mold Electronics. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1489. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121489

Chicago/Turabian StyleFazlali, Zahra, David Schaubroeck, Maarten Cauwe, Karen Leus, Rino Morent, Nathalie De Geyter, Ludwig Cardon, Pieter Bauwens, and Jan Vanfleteren. 2025. "Adhesion Improvement Between Cu-Etched Commercial Polyimide/Cu Foils and Biopolymers for Sustainable In-Mold Electronics" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1489. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121489

APA StyleFazlali, Z., Schaubroeck, D., Cauwe, M., Leus, K., Morent, R., De Geyter, N., Cardon, L., Bauwens, P., & Vanfleteren, J. (2025). Adhesion Improvement Between Cu-Etched Commercial Polyimide/Cu Foils and Biopolymers for Sustainable In-Mold Electronics. Coatings, 15(12), 1489. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121489