Flow-Induced Groove Corrosion in Gas Well Deliquification Tubing: Synergistic Effects of Multiphase Flow and Electrochemistry

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Current Status of Wellbore Corrosion in Drainage Wells

1.2. Analysis of Corrosion Causes in Drainage Wellbores

2. Experiment and Procedure

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Variation Law of Multiphase Flow in the Wellbore String

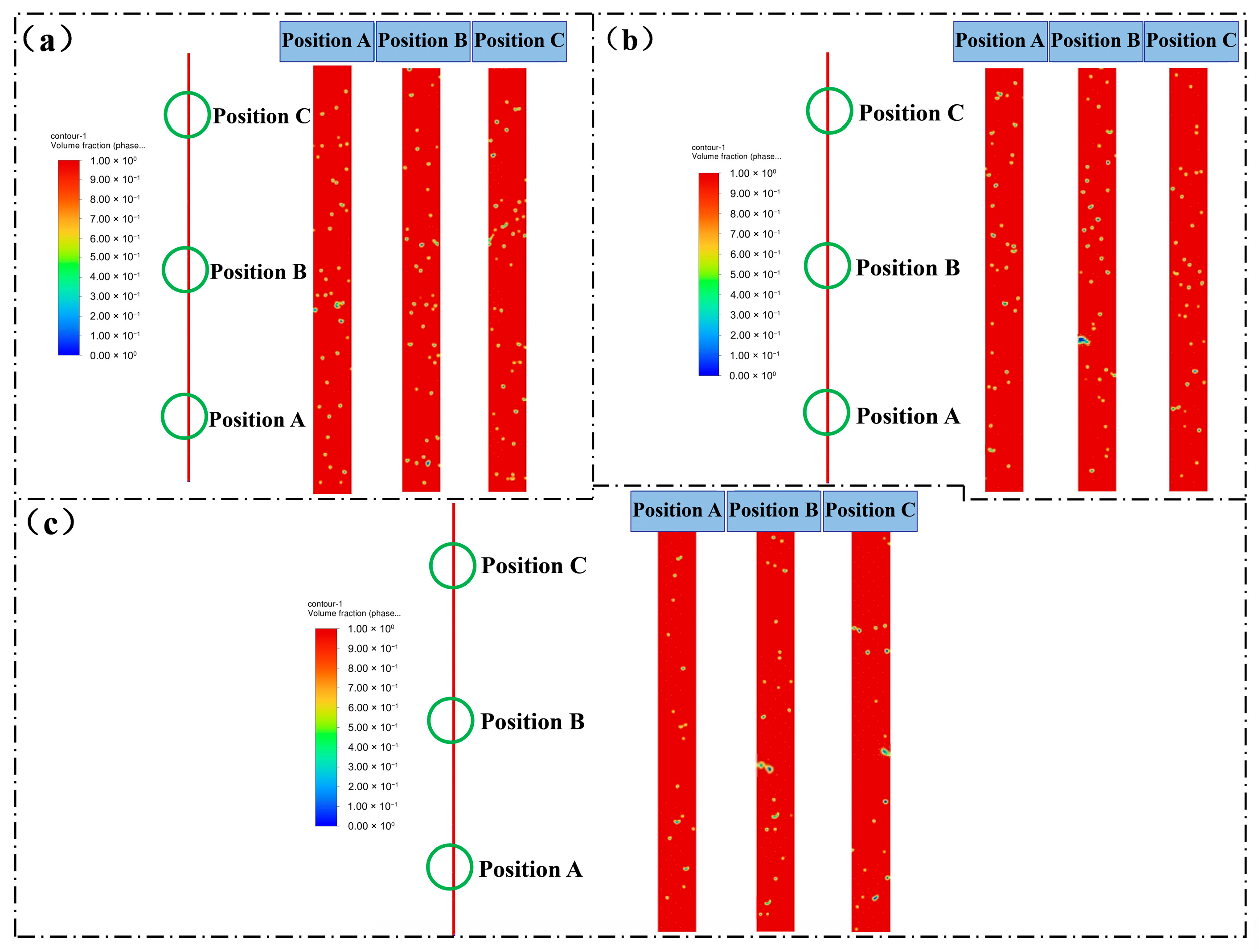

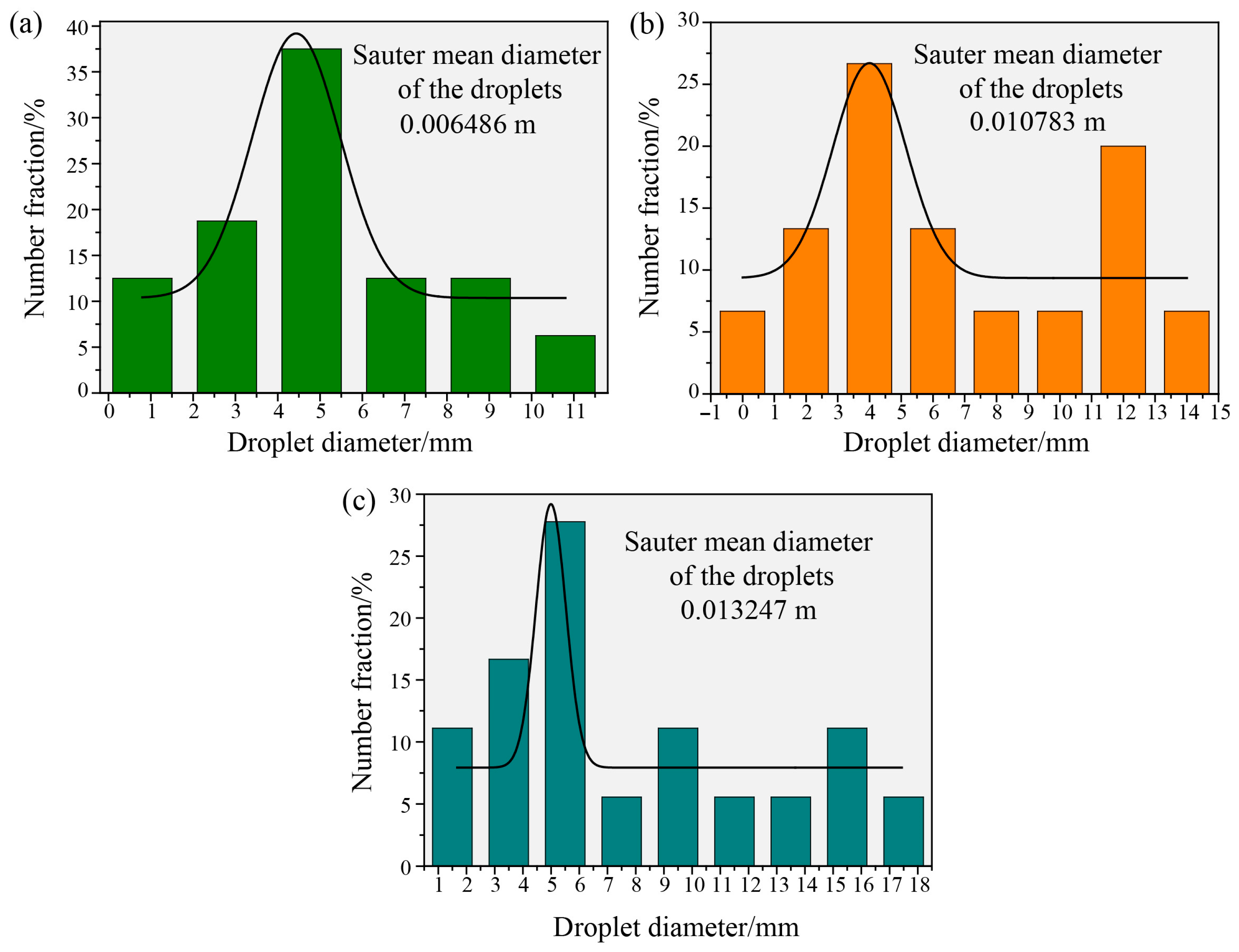

3.1.1. Distributions of Flow Patterns Below the Gas Lift Valve

3.1.2. Flow Pattern Distribution at and Above the Gas Lift Valve

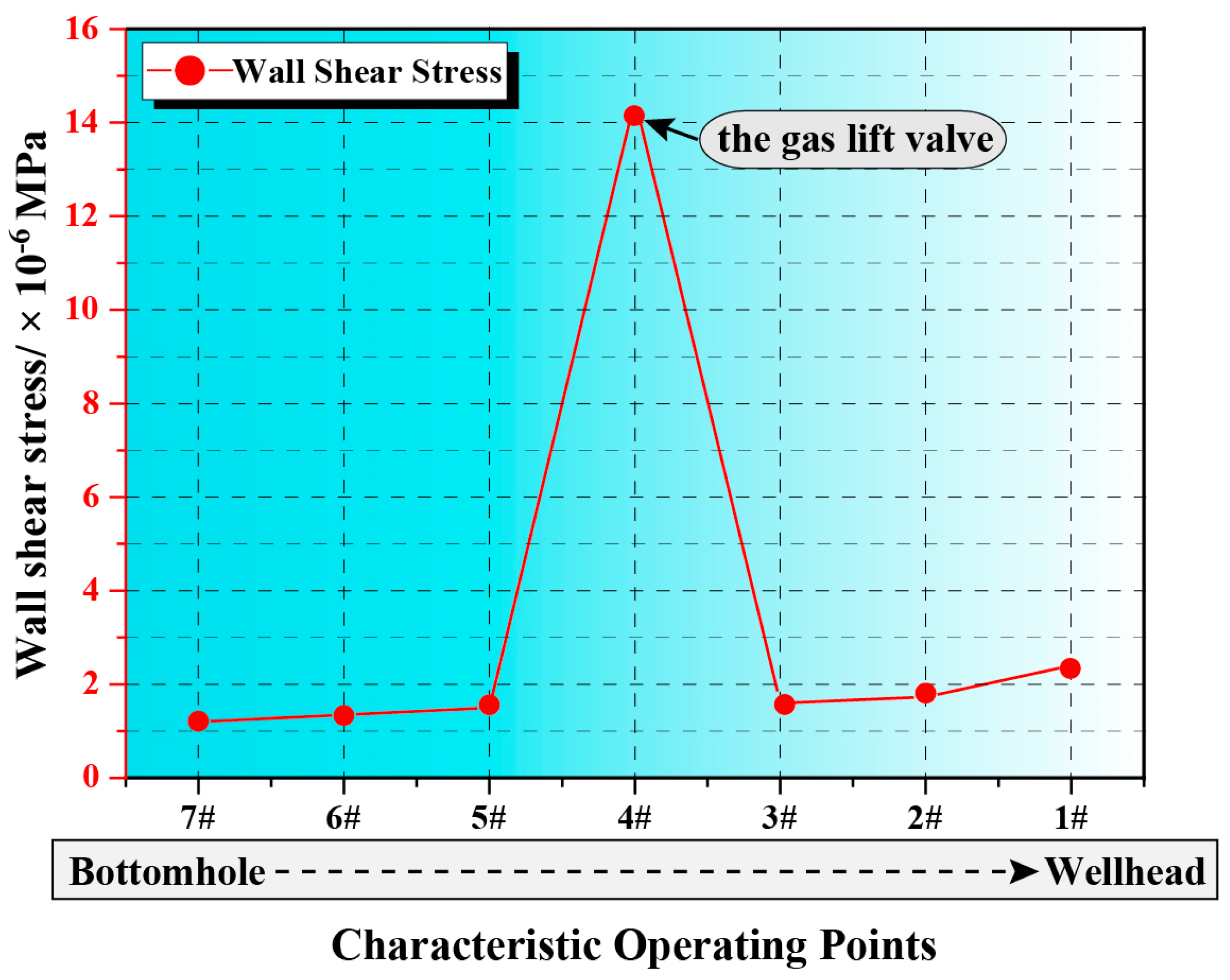

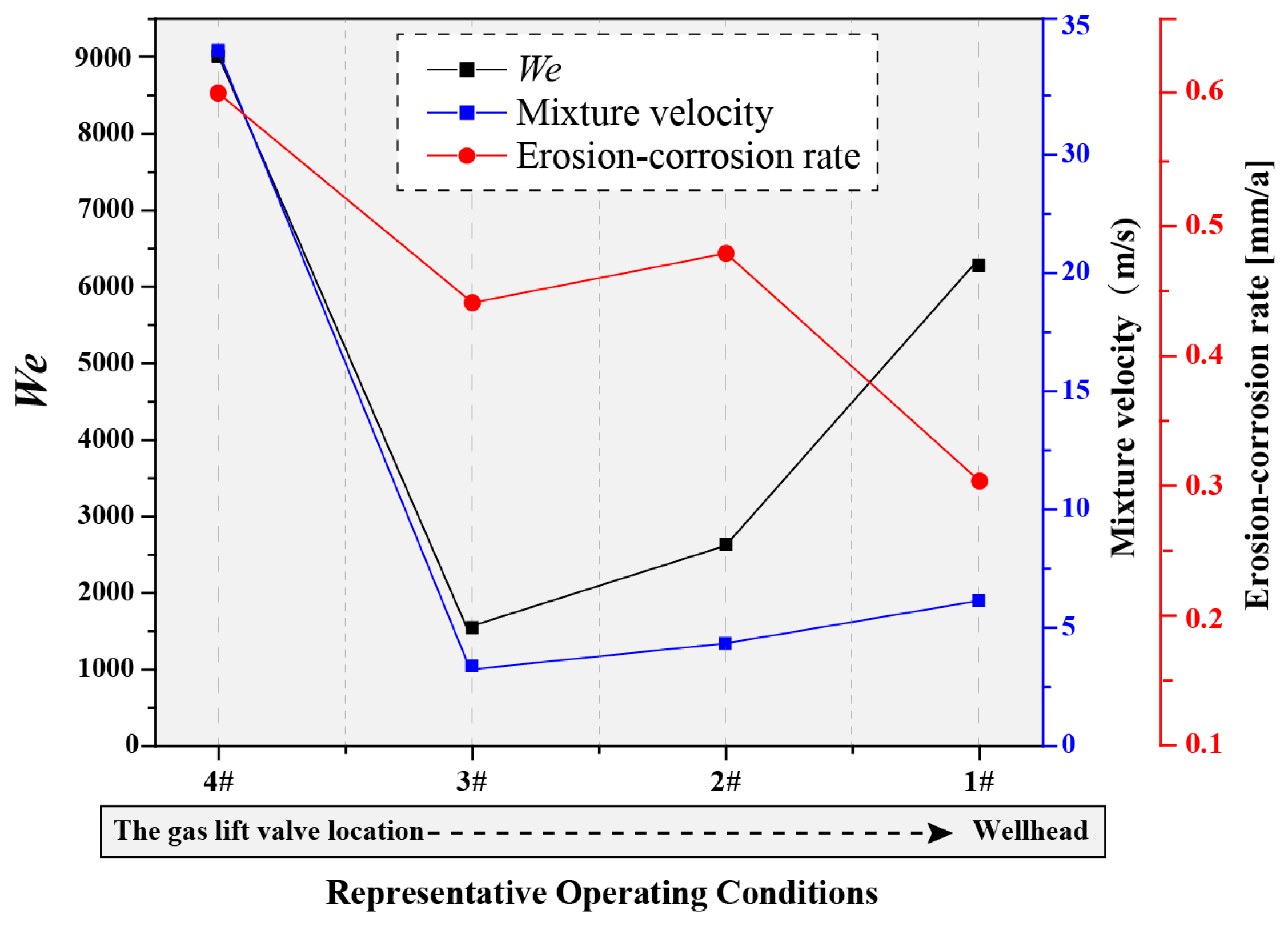

3.2. The Promoting Mechanism of Hydrodynamic Factors on Wellbore Corrosion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xiong, C.M.; Cao, G.Q.; Zhang, J.J.; Li, N.; Xu, W.L.; Wu, J.W.; Li, J.; Zhang, N. Nanoparticle foaming agents for major gas fields in China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2019, 46, 1022–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.T.; Song, Z.J.; Hu, Y.L.; Xu, Y.H.; Zhang, K.X.; Jiang, N.; Han, X.; Zhang, Y.H.; Wang, Z.F. Bubble formation and interface dynamics in oil-water systems: From gas-liquid-liquid interactions to CO2-assisted recovery. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2026, 347, 103695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.C.; Yang, C.D.; Zhang, S.L. Gas Production Engineering; Petroleum Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.J.; Lin, Y.H.; Ma, H.Y.; Zhang, H.L.; Li, Y.F.; Zhang, L.; Deng, K.H. Experimental studies on CO2 corrosion of rubber materials for packer under compressive stress in gas wells. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2017, 80, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.H.; Yuan, B.; Wang, Y.Q.; Zhu, L. H2S-CO2 mixture corrosion-resistant Fe2O3-amended wellbore cement for sour gas storage and production wells. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 188, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadeer, M.; Mohamed, E.; Ibrahim, I.; Akram, A.; Imad, B. Failure analysis, corrosion rate prediction, and integrity assessment of J55 downhole tubing in ultra-deep gas and condensate well. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 151, 107381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimwegen, A.T.; Portela, L.M.; Henkes, R.A.W.M. The effect of the diameter on air-water annular and churn flow in vertical pipes with and without surfactants. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2017, 88, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.T.; Wu, J.Y.; Lv, M.; Li, Q.; Liu, C.Y.; Zhang, T.; Sun, Z.; He, M.X.; Li, X.F. A new straight-line reserve evaluation method for water bearing gas reservoirs with high water production rate. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 196, 107808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.X.; Jiang, M.Q.; Wang, H.Y.; Liu, W.; Lu, Y.J.; Yang, Z.Z.; Chu, J. Probing the mechanism and impact of sand production on defoaming during foam drainage gas recovery: An experimental and molecular dynamics study. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 716, 136673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guet, S.; Ooms, G. Fluid mechanical aspects of the gas-lift technique. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2006, 38, 225–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Kaisare, N.S.; Nandola, N.N. Dynamic plunger lift model for deliquification of shale gas wells. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2017, 103, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamari, A.; Bahadori, A.; Mohammadi, A.H. Prediction of maximum possible liquid rates produced from plunger lift by use of a rigorous modeling approach. SPE Prod. Oper. 2017, 32, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasmi, T.; Rahmawati, S.D.; Sukarno, P.; Soewono, E. Applications of line-pack model of gas flow in intermittent gas lift injection line. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2017, 157, 930–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, S.; Frigaard, I.A.; Taghavi, S.M. Drainage flows in oil and gas well plugging: Experiments and modeling. Geonenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 238, 212894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwonodi, R.I. A novel model for predicting the productivity index of horizontal/vertical wells based on Darcy’s law, drainage radius, and flow convergence. Heliyon 2024, 10, 25073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashmia, G.M.; Hasana, A.R.; Kabir, C.S. Simplified modeling of plunger-lift assisted production in gas wells. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2018, 52, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, R.Q.; Li, Y.; Song, J.P.; Lei, Y. The establishment of multiphase flow experiment platform in gas lift test base. J. Oil Gas Technol. 2014, 36, 129–131. [Google Scholar]

- Nandola, N.N.; Kaisare, N.S.; Gupta, A. Online optimization for a plunger lift process in shale gas wells. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2018, 108, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Boiko, I.; Al-Durra, A. Plastic bag model of the artificial gas lift system for slug flow analysis. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 33, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.; Zou, H.L.; Chen, T.; Ding, Y.H. A method for comparison of lifting effects of plunger lift and continuous gas lift. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 190, 107101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najeeb, A.S.; Ubedullah, A.; Bilal, S.; Muhammad, K.M.; Darya, K.B.; Zhang, R.; Yi, P. Optimizing gas well deliquification: Experimental analysis of surfactant-based strategies for liquid unloading in gas wells for enhanced recovery. Unconv. Resour. 2025, 7, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, B.; Yang, J.Q.; Lu, Y.H.; Yin, B.T. Numerical simulation of gas-liquid two-phase flow oattern in large annulus of deep well. Pet. Drill. Tech. 2024, 52, 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Liu, H.T.; Zhang, Q.; Fan, M.; Yin, B.T.; Wang, X.R.; Sun, X.H.; Wang, Z.Y. Effect of liquid viscosity on the gas-liquid two phase countercurrent flow in the wellbore of bullheading killing. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 221, 111274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.J.; Sun, X.H.; Wang, Z.Y.; Chen, Y.H. Effects of phase transition on gas kick migration in deepwater horizontal drilling. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2017, 46, 710–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Sun, B.J.; Wang, Z.Y.; Wang, J.B.; Yang, C.F. Numerical simulation of two phase flow in wellbores by means of drift flux model and pressure based method. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 36, 811–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsanea, M.; Mateus-Rubiano, C.; Karami, H. Experimental investigation of well deliquification using the partial tubing restrictions. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 243, 213278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washino, K.; Chan, E.L.; Kaji, T. On large scale CFD-DEM simulation for gas-liquid-solid three-phase flows. Particuology 2020, 59, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajemidupe, O.T.; Aliyu, A.M.; Baba, Y.D. Sand minimum transport conditions in gas-solid-liquid three atratified flow in a horizontal pipe at low particle concentrations. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2019, 143, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Pots, B.F.M.; Brown, B.; Kee, K.E.; Nesic, S. A direct measurement of wall shear stress in multiphase flow-Is it an important parameter in CO2 corrosion of carbon steel pipelines? Corros. Sci. 2016, 110, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Yu, F.; Pang, X.; Zhang, G.; Qiao, L.; Chu, W.; Lu, M. Mechanical properties of CO2 corrosion product scales and their relationship to corrosion rates. Corros. Sci. 2008, 50, 2796–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F. Research on Electrochemical Behavior and Corrosion Scale Characteristics of CO2 Corrosion for Tubing and Casing Steel. Ph.D. Thesis, Northwestern Polytechnical University, Xi’an, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- He, T.J.; Jiang, P.; Liao, K.X.; Leng, J.H.; Liao, J.C.; He, G.X.; Zhao, S.; Tang, X. Investigation into flow-induced internal corrosion direct assessment in small-diameter dry gas fluctuating pipeline. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 163, 108566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, B.B.; Lotte, H.; Jens, L.S.; John, H.; Morten, S.J. Flow-induced corrosion of brass flowmeters used for drinking water. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 171, 109394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, M. Erosion-corrosion of metallic materials in slurries: Corrosion Reviews. Corros. Rev. 1994, 12, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | The Remaining Wall Thickness (10−3 m) | Average Wall Thickness (10−3 m) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 3.27 | 5.53 | 2.43 | 2.22 | 3.05 | 3.77 | 3.58 | 2.69 | 5.29 | 2.77 | 3.46 |

| b | 3.85 | 2.13 | 4.98 | 2.55 | 4.22 | 3.54 | 3.77 | 3.35 | 3.43 | 4.79 | 3.66 |

| Operating Point | Section | Well Depth (m) | Outer Diameter (m) | Wall Thickness (m) | Pressure (MPa) | Temperature (°C) | Gas Production (104 m3/d) | Injection Volume (104 m3/d) | Liquid Production Volume (m3/d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1# | Upper part of the gas lift valve | 0 | 0.073025 | 0.00551 | 1.46 | 22.83 | 3.47 | / | 16.3 |

| 2# | 1200 | 0.073025 | 0.00551 | 4.1 | 53.69 | 3.47 | / | 16.3 | |

| 3# | 1500 | 0.073025 | 0.00551 | 4.2 | 55.89 | 3.47 | / | 16.3 | |

| 4# | Gas lift valve position | 1674 | 0.073025 | 0.00551 | 5.7 | 66.48 | 1.9 | 1.57 | 16.3 |

| 5# | Lower part of the gas lift valve | 1715 | 0.073025 | 0.00551 | 7.3 | 69.91 | 1.9 | / | 16.3 |

| 6# | 2500 | 0.073025 | 0.00551 | 14.6 | 86.78 | 1.9 | / | 16.3 | |

| 7# | 3200 | 0.073025 | 0.00551 | 22.61 | 98.75 | 1.9 | / | 16.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, W.; Xie, J.; Yi, J.; Wen, L.; Dai, P.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lv, X. Flow-Induced Groove Corrosion in Gas Well Deliquification Tubing: Synergistic Effects of Multiphase Flow and Electrochemistry. Coatings 2025, 15, 1490. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121490

Song W, Xie J, Yi J, Wen L, Dai P, Li Y, Liu Y, Lv X. Flow-Induced Groove Corrosion in Gas Well Deliquification Tubing: Synergistic Effects of Multiphase Flow and Electrochemistry. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1490. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121490

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Wenwen, Junfeng Xie, Jun Yi, Lei Wen, Pan Dai, Yongxu Li, Yanming Liu, and Xianghong Lv. 2025. "Flow-Induced Groove Corrosion in Gas Well Deliquification Tubing: Synergistic Effects of Multiphase Flow and Electrochemistry" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1490. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121490

APA StyleSong, W., Xie, J., Yi, J., Wen, L., Dai, P., Li, Y., Liu, Y., & Lv, X. (2025). Flow-Induced Groove Corrosion in Gas Well Deliquification Tubing: Synergistic Effects of Multiphase Flow and Electrochemistry. Coatings, 15(12), 1490. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121490