Pulse-Controlled Electrodeposition of Ni/ZrO2 with Coumarin Additive: A Parametric Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Electrolyte Composition

2.2. Electrodeposition Procedure

2.3. Characterization Techniques

3. Results

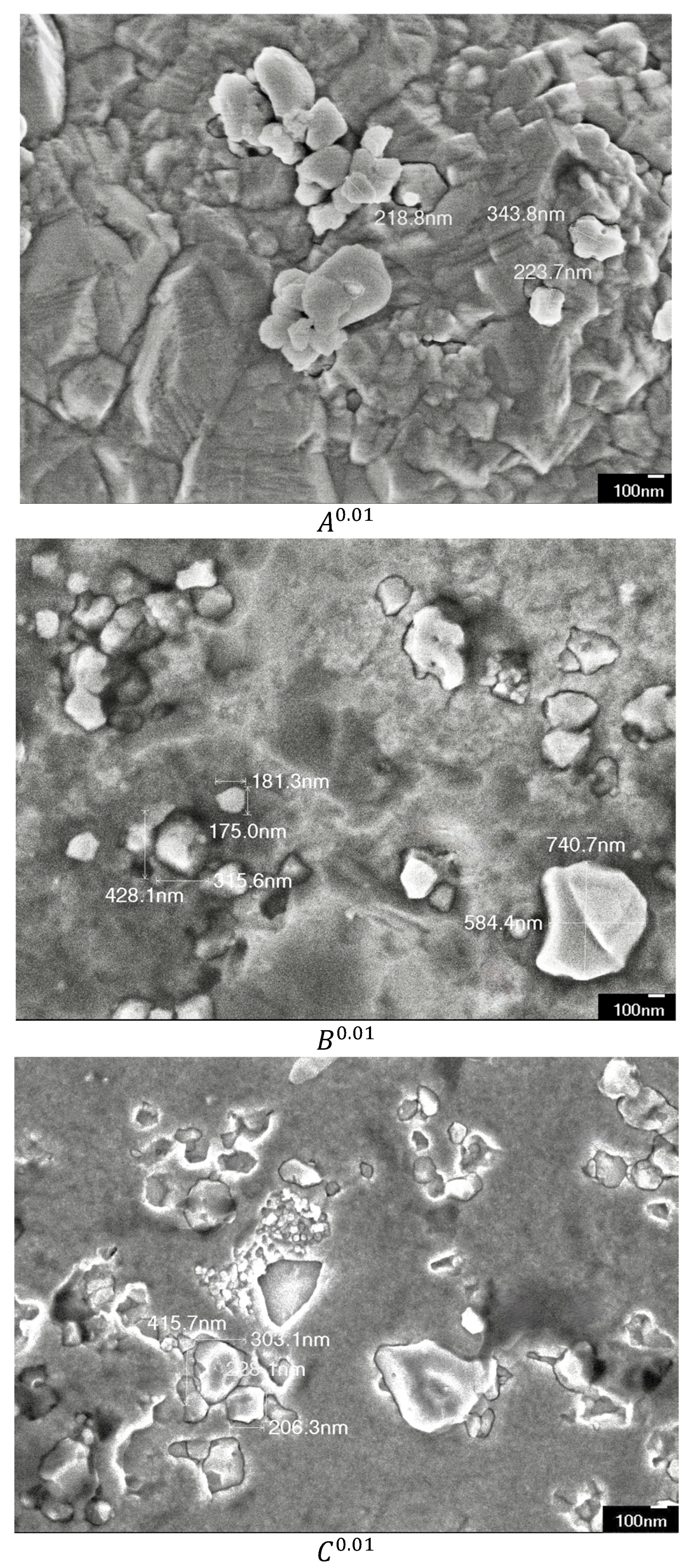

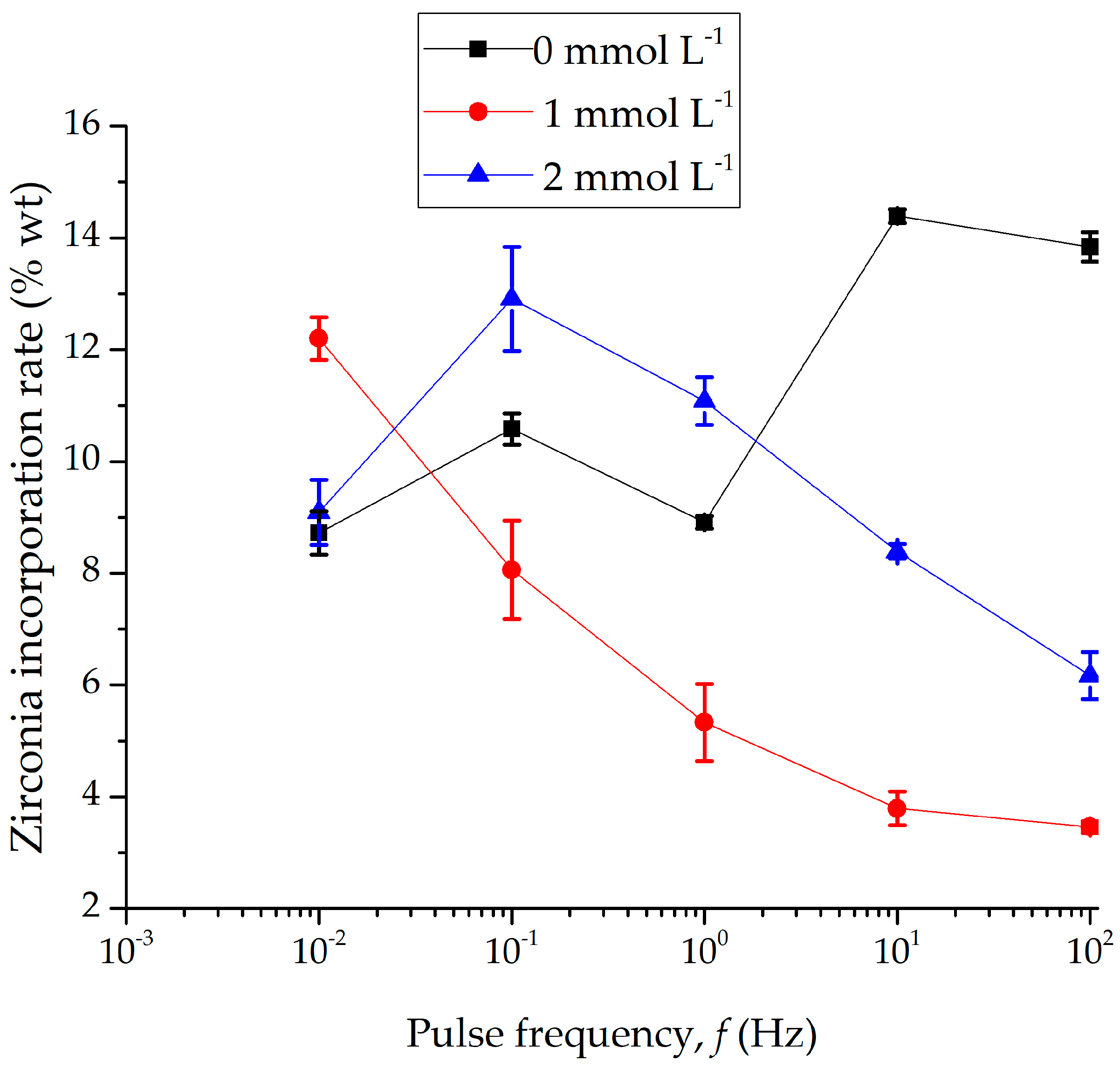

3.1. Microscopical Investigation and Compositional Analysis

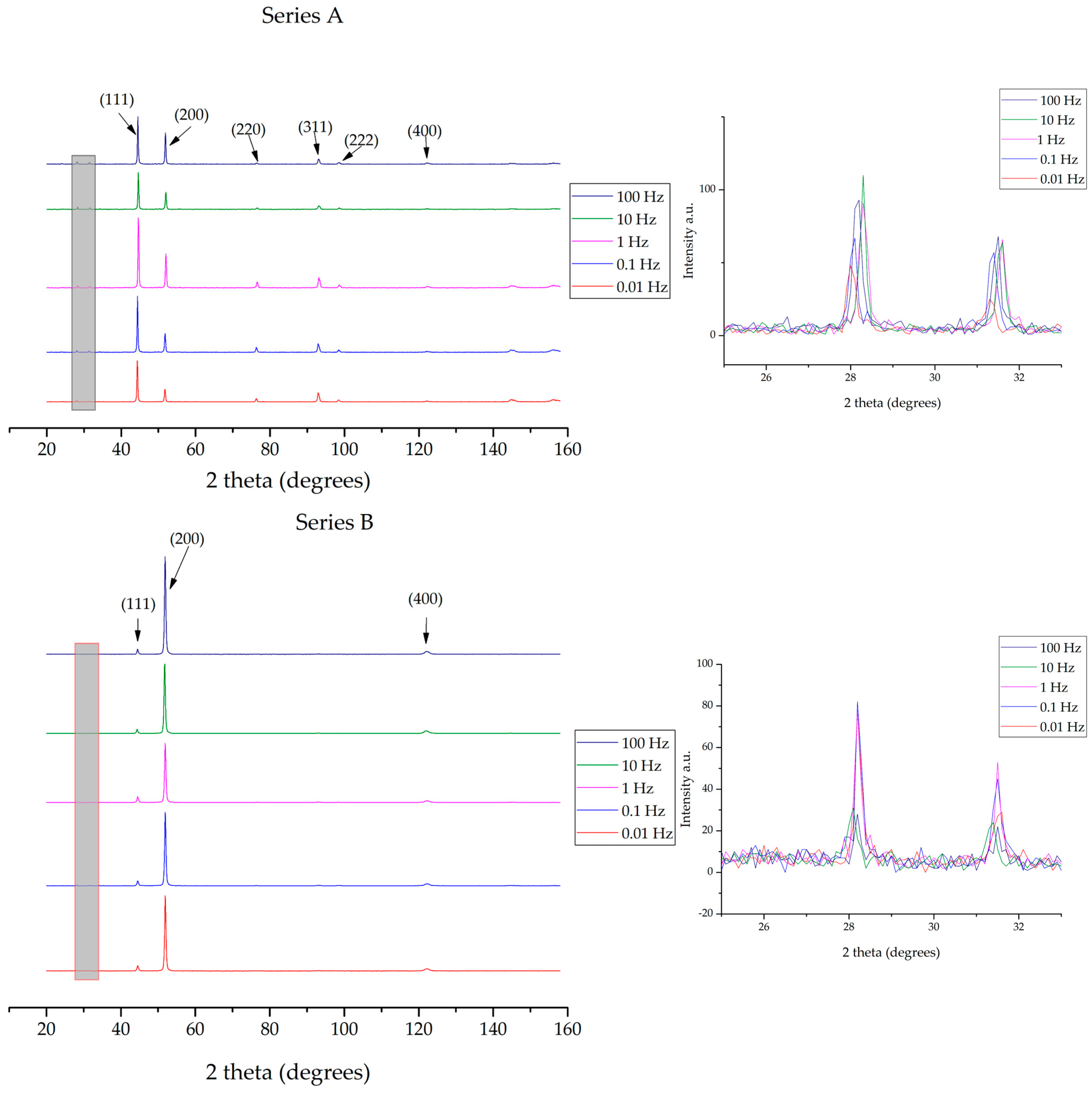

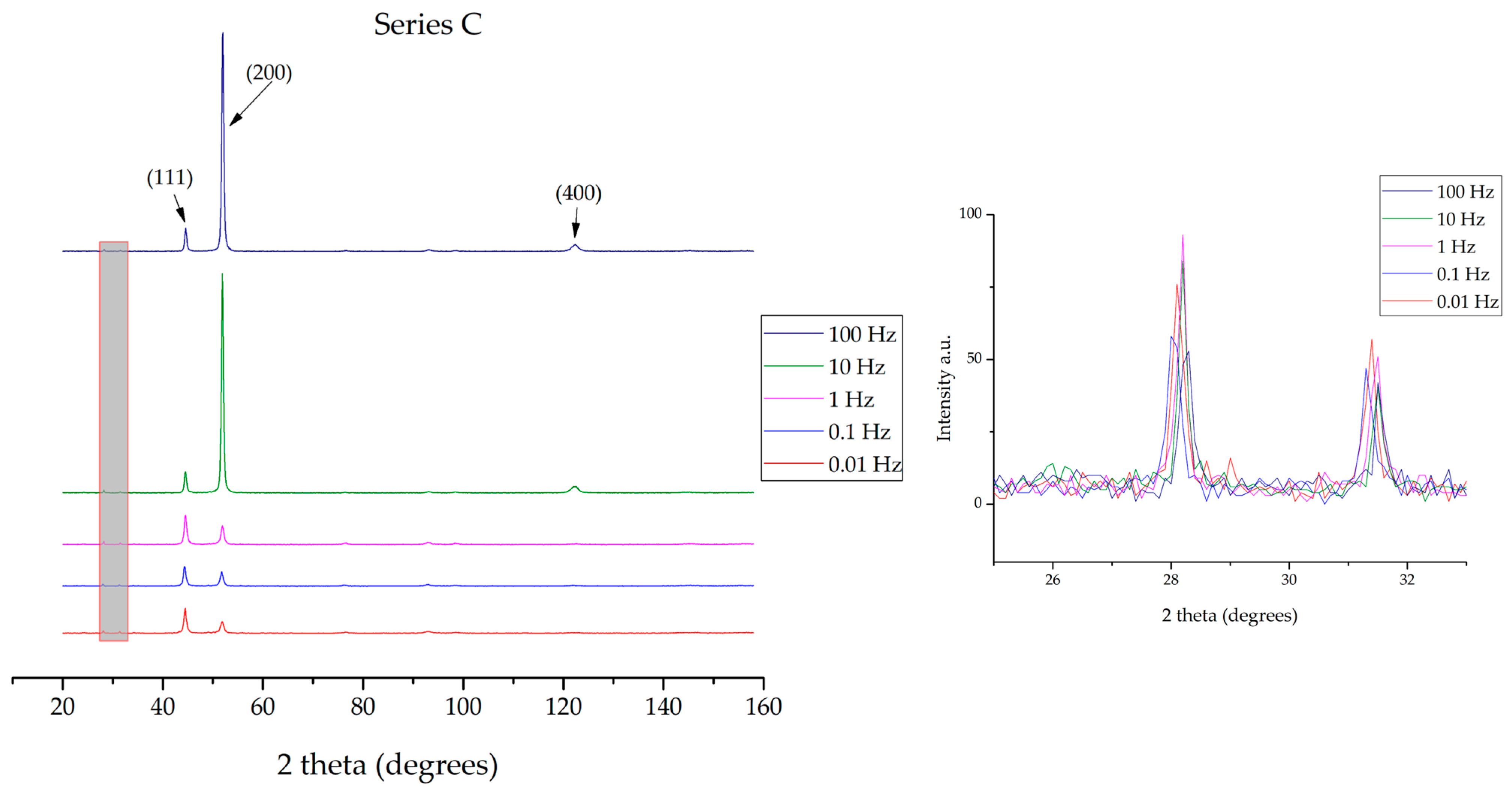

3.2. XRD Analyses, Crystallographic Orientation and Mean Crystalline Diameter Size

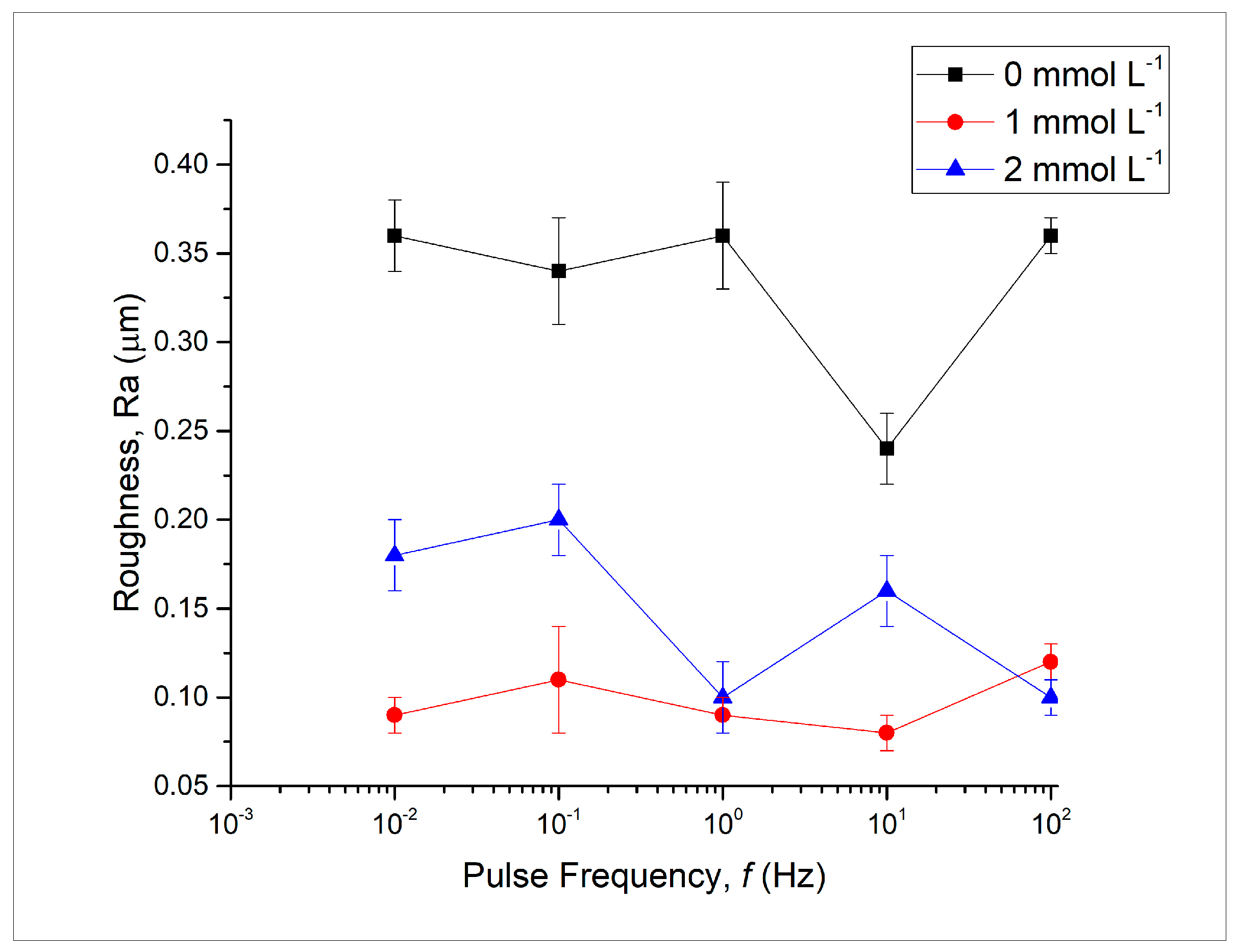

3.3. Determination of Coatings’ Vickers Microhardness and Roughness

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion on Microscopical Investigation and Compositional Analysis Findings

4.2. Discussion on XRD Analyses, Crystallographic Orientation and Mean Crystalline Diameter Size Findings

4.3. Discussion on the Determination of Coatings’ Vickers Microhardness and Roughness Findings

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DC | Direct Current |

| PC | Pulse Current |

| Duty Cycle | |

| f | Pulse Frequency |

| d | Mean crystallite diameter size |

| RTC(hkl) | Relative Texture Coefficient (hkl) |

| HV | Vickers Microhardness |

| Ra | Average Surface Roughness |

References

- Zellele, D.M.; Yar-Mukhamedova, G.S.; Rutkowska-Gorczyca, M. A Review on Properties of Electrodeposited Nickel Composite Coatings: Ni-Al2O3, Ni-SiC, Ni-ZrO2, Ni-TiO2 and Ni-WC. Materials 2024, 17, 5715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondaiah, P.; Pitchumani, R. Electrodeposited nickel coatings for exceptional corrosion mitigation in industrial grade molten chloride salts for concentrating solar power. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 189, 113848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Mozammel, M.; Emarati, S.M.; Alinezhadfar, M. The role of TiO2 nanoparticles on the topography and hydrophobicity of electrodeposited Ni-TiO2 composite coating. Surf. Topogr. Metrol. Prop. 2020, 8, 025008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A.; Saeed, A.; Khan, Z.A. Influence of the Duty Cycle of Pulse Electrodeposition-Coated Ni-Al2O3 Nanocomposites on Surface Roughness Properties. Materials 2023, 16, 2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón, J.A.; Henao, J.E.; Gómez, M.A. Erosion–corrosion resistance of Ni composite coatings with embedded SiC nanoparticles. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 124, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardavila, M.M.; Hamilakis, S.; Loizos, Z.; Kollia, C. Ni/ZrO2 composite electrodeposition in the presence of coumarin: Textural modifications and properties. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2015, 45, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, D.J.; Kim, H.P. Electro-deposition of oxide-dispersed nickel composites and the behavior of their mechanical properties. Met. Mater. Int. 2009, 15, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirlapur, P.; Muniprakash, M.; Srivastava, M. Corrosion and Wear Response of Oxide-Reinforced Nickel Composite Coatings. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2016, 25, 2563–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, F.C.; Wang, S.; Zhou, N. The electrodeposition of composite coatings: Diversity, applications and challenges. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2020, 20, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardavila, Μ.M.; Sofianos, M.V.; Rodriguez, B.J.; Bekarevich, R.; Tzanis, A.; Gyftou, P.; Kollia, C. A comprehensive investigation of the effect of pulse plating parameters on the electrodeposition of Ni/ZrO2 composite coatings. Results Surf. Interfaces 2025, 18, 100421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Ying, W.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q. Influences of Duty Cycle and Pulse Frequency on Properties of Ni-SiC Nanocomposites fabricated by Pulse Electrodeposition. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2020, 15, 10550–10569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, U.S.; Tripathy, B.C.; Singh, P.; Keshavarz, A.; Iglauer, S. Roles of organic and inorganic additives on the surface quality, morphology, and polarization behavior during nickel electrodeposition from various baths: A review. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2019, 49, 847–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costavaras, T.A.; Froment, M.; Hugot-Le Goff, A.; Georgoulis, C. The influence of unsaturated organic molecules in the electrocrystallization on nickel. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1973, 120, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kima, S.-M.; Jina, S.-H.; Leea, Y.-J.; Lee, M.H. Design of Nickel Electrodes by Electrodeposition: Effect of Internal Stress on Hydrogen Evolution Reaction in Alkaline Solutions. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 252, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, G.T.; Taylor, K.J. The effects of coumarin in the electrodeposition of nickel. Electrochim. Acta 1963, 8, 887–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, G.T.; Taylor, K.J. The reactions of coumarin, cinnamyl alcohol, butynediol and propargyl alcohol at an electrode on which nickel is depositing. Electrochim. Acta 1966, 11, 1685–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, W. Nickel Plating Handbook; Nickel Institute: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2022; pp. 16, 17, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, F.C.; Low, C.T.J.; Bello, J.O. Influence of surfactants on electrodeposition of a Ni-nanoparticulate SiC composite coating. Trans. IMF 2015, 93, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajevardi, S.A.; Shahrabi, T. Effects of pulse electrodeposition parameters on the properties of Ni–TiO2 nanocomposite coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2010, 256, 6775–6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, P.; Mohanraj, M.; Sathish Kumar, R.; Thirumoorthy, A.; Prabhakaran, S. Evaluation on the microhardness of Ni-TiO2 nanocomposite coatings on AISI 1022 substrate. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 62, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, L.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, T. Influence of pulse frequency on the microstructure and wear resistance of electrodeposited Ni–Al2O3 composite coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2006, 201, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannopoulos, F.; Chronopoulou, N.; Bai, J.; Zhao, H.; Pantelis, D.I.; Pavlatou, E.A.; Karantonis, A. Nickel/MWCNT-Al2O3 electrochemical co-deposition: Structural properties and mechanistic aspects. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 207, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkar, T.; Harimkar, S.P. Effect of electrodeposition conditions and reinforcement content on microstructure and tribological properties of nickel composite coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2011, 205, 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostani, B.; Parvini Ahmadi, N.; Yazdani, S.; Arghavanian, R. Co-electrodeposition and properties evaluation of functionally gradient nickel coated ZrO2 composite coating. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2018, 28, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sknar, Y.E.; Sknar, I.V.; Savchuk, O.O.; Hrydnieva, T.V.; Butyrina, O.D. Electrodeposition of Ni-zirconia or Ni-titania composite coatings from a methanesulfonic acid bath. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 452, 129120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amblard, J.; Froment, M.; Spyrellis, N. Origine de textures dans les depot electrolytiques de nickel. Surf. Technol. 1977, 5, 205–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-C.; West, A.C. Nickel Deposition in the Presence of Coumarin An Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Study. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1997, 144, 3050–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, H.; Wang, W.; Meng, Y. Effect of Polyethyleneimine Cationic Surfactant on Morphology and Corrosion Resistance of Electrodeposited Ni-Co-SiC Composite Coatings. Coatings 2023, 13, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arghavanian, R.; Parvini Ahmadi, N.; Yazdani, S.; Bostani, B. Investigations on corrosion proceeding path and EIS of Ni–ZrO2 composite coating. Surf. Eng. 2012, 28, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.F.; Ding, S.; Wang, G.F. Different superplastic deformation behavior of nanocrystalline Ni and ZrO2/Ni nanocomposite. Mater. Lett. 2008, 62, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollia, C.; Spyrellis, N.; Amblard, J.; Froment, M.; Maurin, G. Nickel plating by pulse electrolysis: Textural and microstructural modifications due to adsorption/desorption phenomena. J. Appl. Electrochem. 1990, 20, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amblard, J.; Epelboin, I.; Froment, M.; Maurin, G. Inhibition and nickel electrocrystallization. J. Appl. Electrochem. 1979, 9, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibl, N. Some theoretical aspects of pulse electrolysis. Surf. Technol. 1980, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, D.-H.; Hong, K.-S.; Kim, J.-S.; Lee, J.-L.; Kim, G.-E.; Kwon, H.-S. Synergistic effects of coumarin and cis-2-butene-1,4-diol on high speed electrodeposition of nickel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2014, 248, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value/Range |

|---|---|

| NiSO4·6H2O | 300 L−1 |

| NiCl2·6H2O | 35 g L−1 |

| H3BO3 | 40 g L−1 |

| ZrO2 | 40 g L−1 |

| Coumarin, Ccoum | 0, 1, 2 mmol L−1 |

| pH | 4.4 ± 0.1 |

| Temperature, Θ | 50 ± 1 °C |

| Peak current density, Jp | 5 A dm−2 |

| Duty cycle, γ | 70% |

| Pulse frequency, f (Hz) | 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100 |

| Ton (s) | 70, 0.7, 0.07, 7 × 10−3, 7 × 10−4 |

| Toff (s) | 30, 0.3, 0.03, 3 × 10−3, 3 × 10−4 |

| Deposition time | Adjusted to ~90 µm coating |

| Agitation | Homogenizer, 12,000 rpm |

| Series | Deposits’ Abbreviation | Ccoum (mmol L−1) | Pulse Frequency (Hz) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | 0.01 | |

| 0 | 0.1 | ||

| 0 | 1 | ||

| 0 | 10 | ||

| 0 | 100 | ||

| B | 1 | 0.01 | |

| 1 | 0.1 | ||

| 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 10 | ||

| 1 | 100 | ||

| C | 2 | 0.01 | |

| 2 | 0.1 | ||

| 2 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 10 | ||

| 2 | 100 |

| Deposit | Texture | d (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| [211] | 27.76 | |

| [211] | 27.11 | |

| [211]+[100] | 25.99 | |

| [100]+[211] | 27.46 | |

| [100]+[211] | 27.44 | |

| [100] | 22.49 | |

| [100] | 22.55 | |

| [100] | 21.50 | |

| [100] | 21.53 | |

| [100] | 22.22 | |

| [100]+[211] | 11.41 | |

| [100]+[211] | 13.49 | |

| [100]+[211] | 13.25 | |

| [100] | 19.66 | |

| [100] | 19.30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dardavila, M.M.; Kollia, C. Pulse-Controlled Electrodeposition of Ni/ZrO2 with Coumarin Additive: A Parametric Study. Coatings 2025, 15, 1400. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121400

Dardavila MM, Kollia C. Pulse-Controlled Electrodeposition of Ni/ZrO2 with Coumarin Additive: A Parametric Study. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1400. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121400

Chicago/Turabian StyleDardavila, Maria Myrto, and Constantina Kollia. 2025. "Pulse-Controlled Electrodeposition of Ni/ZrO2 with Coumarin Additive: A Parametric Study" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1400. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121400

APA StyleDardavila, M. M., & Kollia, C. (2025). Pulse-Controlled Electrodeposition of Ni/ZrO2 with Coumarin Additive: A Parametric Study. Coatings, 15(12), 1400. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121400