Behavior of Flexible Biogas Digester Made of PVC-Coated PET Polyester Fabric with Increased Durability by Nanocoating Under Northridge (1994) Earthquake Effect

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To present one of the first comprehensive studies on flexible polymeric biogas digesters developed using nanocoating, thereby filling a gap in the literature. At the same time, filling this gap also highlights the innovative aspect of the study.

- Demonstrating the effectiveness of ZrO2 nanocoatings in enhancing structural performance, durability, and seismic safety.

- Guiding future applications for sustainable and earthquake-resilient renewable energy systems in rural and industrial contexts.

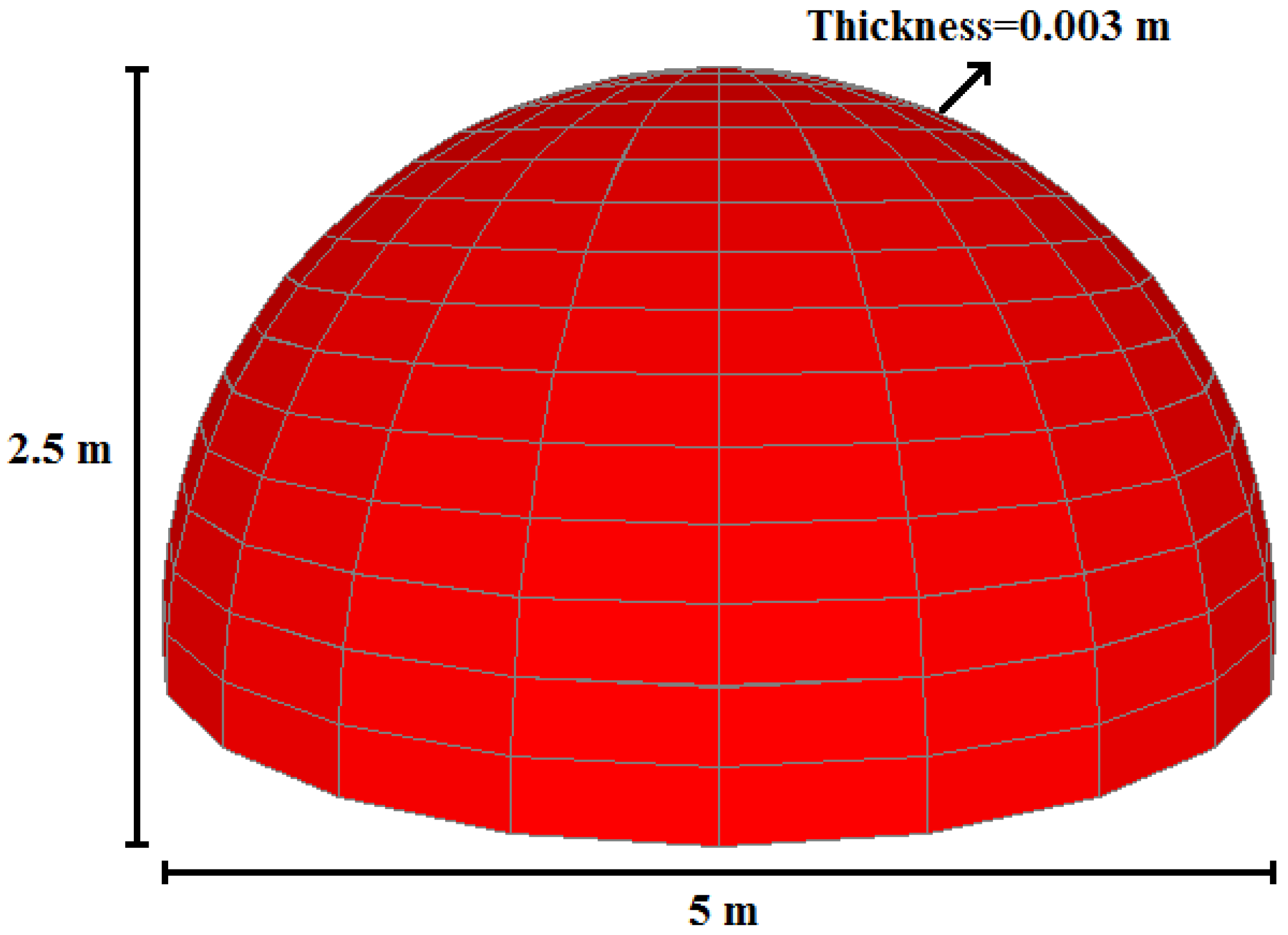

2. Description of the Flexible Biogas Digester

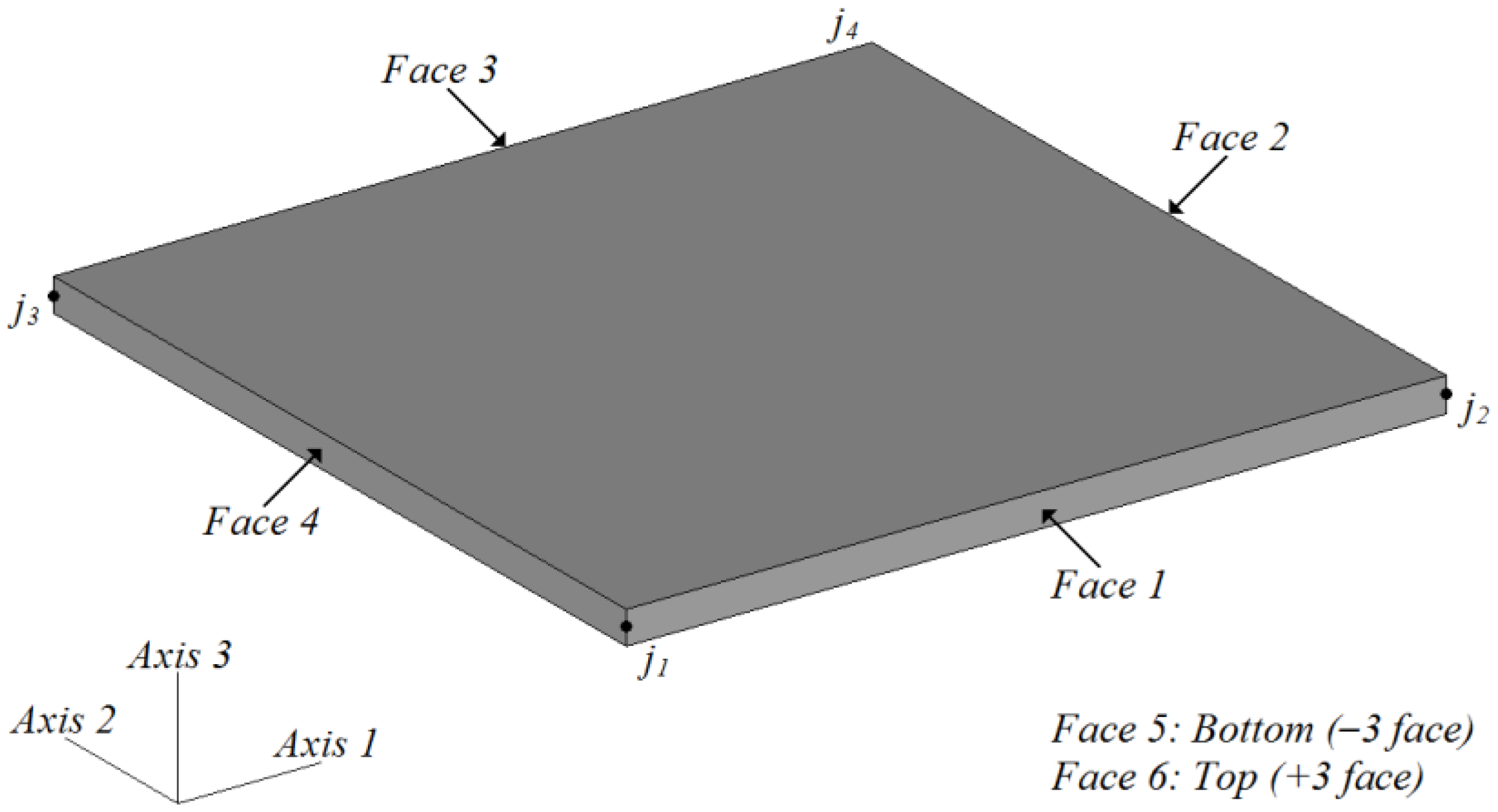

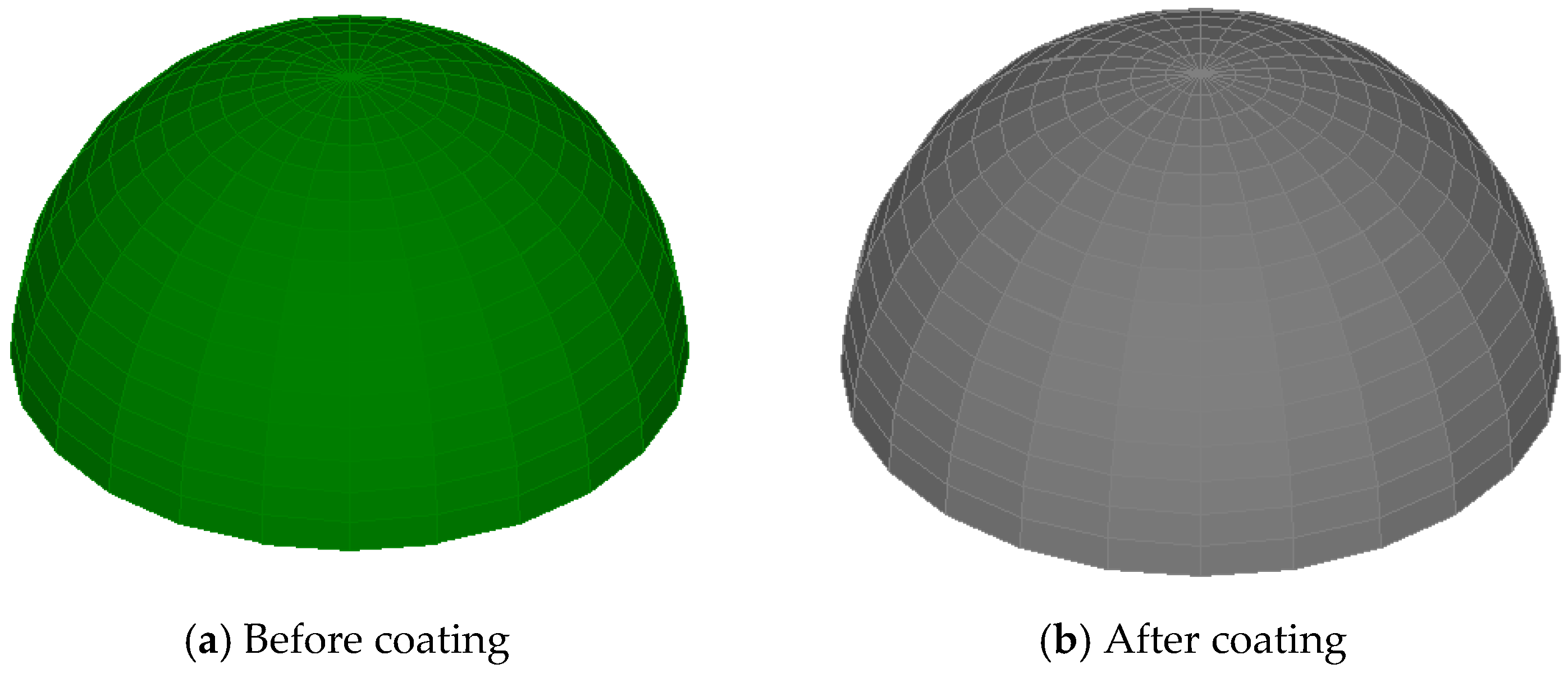

3. Finite Element Modeling of the Digester

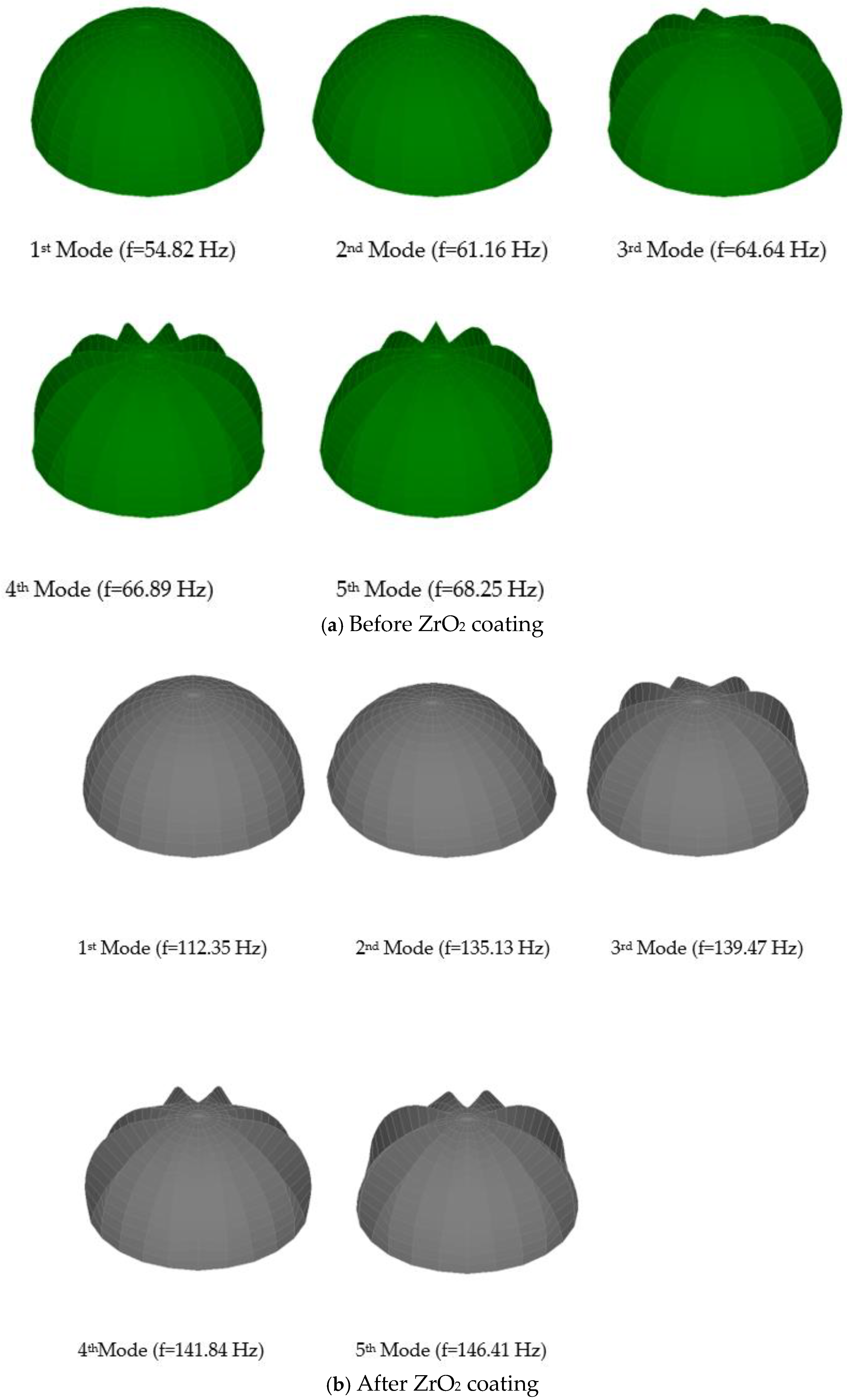

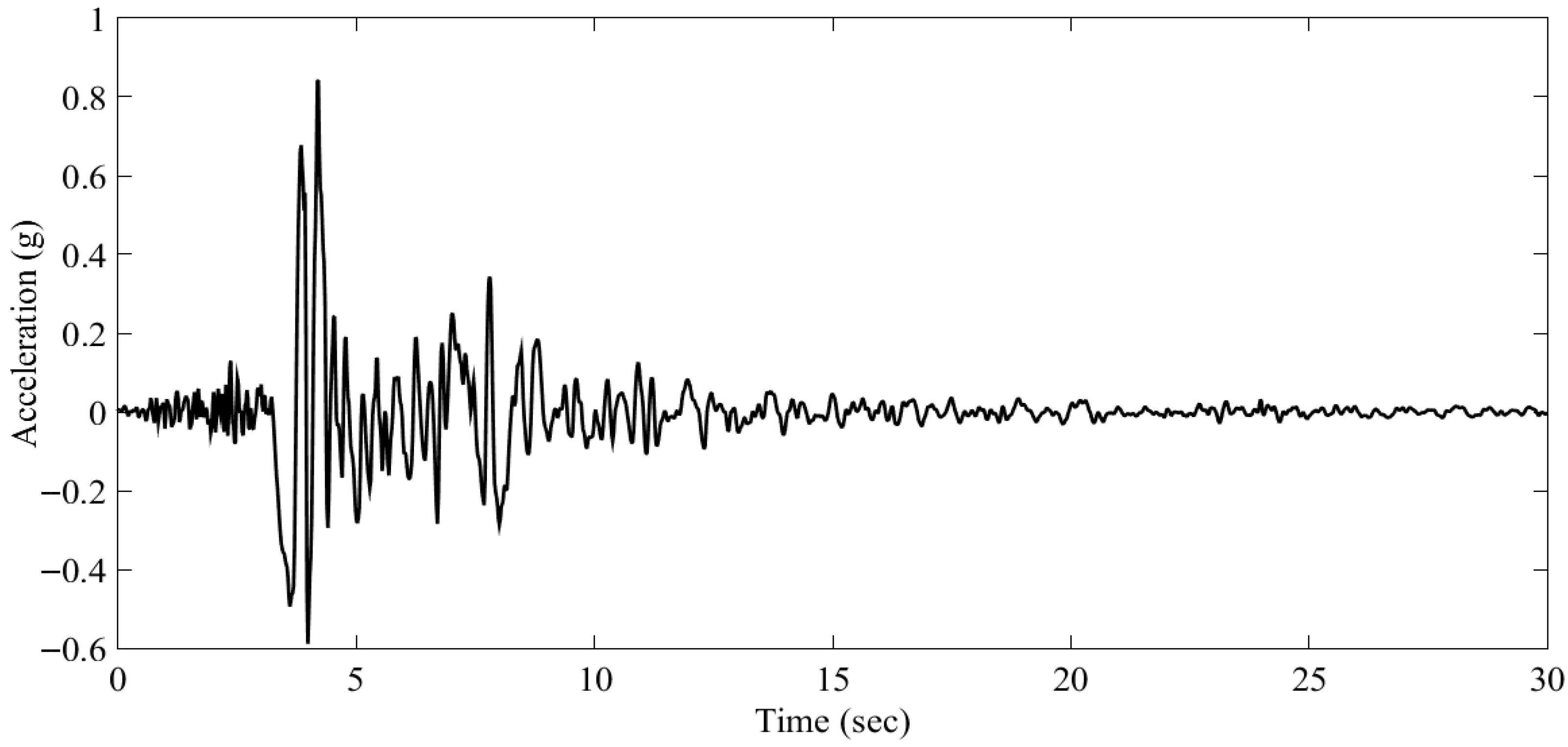

4. Dynamic Analyses of the Biogas Digester

4.1. Displacement Response

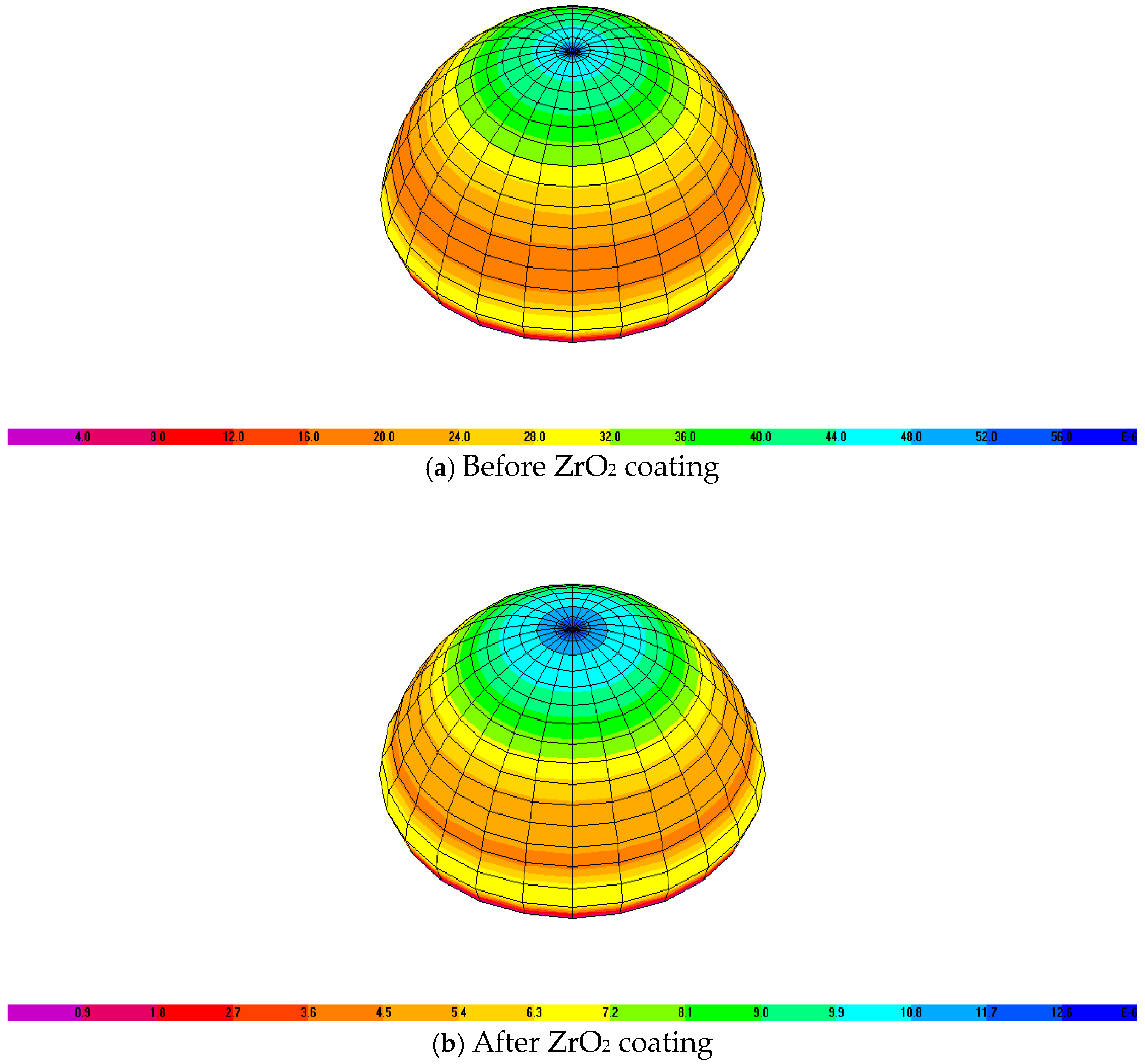

4.2. Stress Distribution and Critical Zones

5. Conclusions

- Enhanced structural rigidity: ZrO2 coating increased natural frequencies from 54.82–68.25 Hz to 112.35–146.41 Hz, indicating improved stiffness without significant mass addition.

- Reduced displacement: Maximum horizontal displacement at the digester’s top decreased by 77% (from 0.057 mm to 0.013 mm), demonstrating superior performance compared to conventional reinforcement methods.

- Improved stress distribution: Von Mises stress at critical bottom regions reduced significantly—minimum stress decreased from 11.41 kPa to 4.47 kPa and maximum stress from 60.47 kPa to 15.18 kPa—minimizing stress concentration at ground interface zones.

- Practical benefits: Increased rigidity reduces crack formation, corrosion, and maintenance costs while maintaining a favorable strength-to-weight ratio.

- Broader implications: Nanocoatings offer superior corrosion resistance, easy applicability, extended service life, and fire resistance, positioning them as viable alternatives to traditional retrofitting techniques for various biogas digester applications.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PVC | Poly(vinyl chloride) |

| PET | Poly(ethylene terephthalate) |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| FRP | Fiber Reinforced Polymer |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| HDPE | High Density Polyethylene |

| PGA | Peak Ground Acceleration |

| CNTs | Carbon Nanotubes |

References

- Martins das Neves, L.C.; Converti, A.; Vessoni Penna, T.C. Biogas production: New trends for alternative energy sources in rural and urban zones. Chem. Eng. Technol. Ind. Chem. Plant Equip. Process Eng. Biotechnol. 2009, 32, 1147–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abanades, S.; Abbaspour, H.; Ahmadi, A.; Das, B.; Ehyaei, M.A.; Esmaeilion, F.; Assad, M.E.H.; Hajilounezhad, T.; Jamali, D.H.; Hmida, A.; et al. A critical review of biogas production and usage with legislations framework across the globe. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 3377–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drosg, B.; Fuchs, W.; Al Seadi, T.; Madsen, M.; Linke, B. Nutrient Recovery by Biogas Digestate Processing; IEA Bioenergy: Dublin, Ireland, 2015; Volume 2015, p. 711. [Google Scholar]

- Obileke, K.; Onyeaka, H.; Nwokolo, N. Materials for the design and construction of household biogas digesters for biogas production: A review. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 3761–3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiandelli, M. Development and Implementation of Small-Scale Biogas Balloon Biodigester in Bali, Indonesia. Master’s Thesis, KTH School of Industrial Engineering and Management, Stockholm, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Asadi, H.; Uhlemann, J.; Stranghoener, N.; Ulbricht, M. Tensile strength deterioration of PVC coated PET woven fabrics under single and multiplied artificial weathering impacts and cyclic loading. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 342, 127843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Li, Z.; Mang, H.P.; Huba, E.M.; Gao, R.; Wang, X. Development and application of prefabricated biogas digesters in developing countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 34, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiman, I. The role of fixed-dome and floating drum biogas digester for energy security in Indonesia. Indones. J. Energy 2020, 3, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandraul, A.; Murari, V.; Kumar, S. A review on dynamic analysis of membrane based space structures. Adv. Space Res. 2024, 74, 740–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyester. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polyester (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Sen, A.K. Coated Textiles: Principles and Applications, 2nd ed.; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, U. Strengthening of Structures Using Carbon Fibre/Epoxy Composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 1995, 9, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmiran, A.; Zagers, K.; Yuan, W. Nonlinear Finite Element Modeling of Concrete Confined by Fiber Composites. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 2000, 35, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Einde, L.; Zhao, L.; Seible, F. Use of FRP Composites in Civil Structural Applications. Constr. Build. Mater. 2003, 17, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H. Seismic Assessment of a Retrofitted Chimney by FEM Analysis and Field Testing. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 2004, 4, 337–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obileke, K.; Mamphweli, S.; Meyer, E.L.; Makaka, G.; Nwokolo, N. Design and fabrication of a plastic biogas digester for the production of biogas from cow dung. J. Eng. 2020, 2020, 1848714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuce, I.; Canoglu, S.; Yukseloglu, S.M.; Li Voti, R.; Cesarini, G.; Sibilia, C.; Larciprete, M.C. Titanium and silicon dioxide-coated fabrics for management and tuning of infrared radiation. Sensors 2022, 22, 3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, S.; Akhtar, A.; Faisal, S.; Husain, M.D.; Siddiqui, M.O.R. Durable multifunction finishing on polyester knitted fabric by applying zinc oxide nanoparticles. Pigment Resin Technol. 2025, 54, 1006–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharouf, H.M.; Tuhmaz, G.; Saffour, Z. Preparation of Zinc Oxide Nano-Layer on Cotton Fabric for UV Protection Application. Al-Nahrain J. Eng. Sci. 2019, 22, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankodi, D.H.; Agarwal, D.B. Studies on nano–UV protective finish on apparel fabrics for health protection. Res. J. Text. Appar. 2011, 15, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczyglewska, P.; Feliczak-Guzik, A.; Nowak, I. Nanotechnology–general aspects: A chemical reduction approach to the synthesis of nanoparticles. Molecules 2023, 28, 4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, S.A.; Raina, A.; Mohan, S.; Arvind Singh, R.; Jayalakshmi, S.; Irfan Ul Haq, M. Nanostructured coatings: Review on processing techniques, corrosion behaviour and tribological performance. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Xia, K.; Wu, D.; Mou, J.; Zheng, S. Technical characteristics and wear-resistant mechanism of nano coatings: A review. Coatings 2020, 10, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourhashem, S.; Saba, F.; Duan, J.; Rashidi, A.; Guan, F.; Nezhad, E.G.; Hou, B. Polymer/Inorganic nanocomposite coatings with superior corrosion protection performance: A review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2020, 88, 29–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, K.L.; Vidyasagar, C.S.; Benny Karunakar, D. Mechanical and tribological properties of MgO/multiwalled carbon nanotube-reinforced zirconia-toughened alumina composites developed through spark plasma sintering and microwave sintering. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2022, 31, 682–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Rodríguez, C.; Fernández-González, D.; García-Quiñonez, L.V.; Castillo-Rodríguez, G.A.; Aguilar-Martínez, J.A.; Verdeja, L.F. MgO refractory doped with ZrO2 nanoparticles: Influence of cold isostatic and uniaxial pressing and sintering temperature in the physical and chemical properties. Metals 2019, 9, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Salas, B.; Salvador-Carlos, J.; Beltrán-Partida, E.A.; Castillo-Sáenz, J.; Chairez-González, J.; Curiel-Álvarez, M. Zirconium Nanostructures Obtained from Anodic Synthesis By-Products and Their Potential Use in PVA-Based Coatings. Ceramics 2025, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogas, J.A.; Ahmed, H.H.; Diniz, T. Influence of cracking on the durability of reinforced concrete with carbon nanotubes. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhineshbabu, N.R.; Manivasakan, P.; Yuvakkumar, R.; Prabu, P.; Rajendran, V. Enhanced functional properties of ZrO2/SiO2 hybrid nanosol coated cotton fabrics. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2013, 13, 4017–4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Xie, W.; Yu, K.; Qian, K. Preparation and characterization of basalt fabrics coated with zirconia obtained by sol-gel method for textile reinforced concrete. J. Text. Inst. 2022, 113, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthys, S.; Toutanji, H.; Taerwe, L. Stress–Strain Behavior of Large-Scale Circular Columns Confined with FRP Composites. J. Struct. Eng. 2006, 132, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.L.; Zhang, L. State-of-the-Art Review on FRP Strengthened Steel Structures. Eng. Struct. 2007, 29, 1808–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallares, F.J.; Ivorra, S.; Pallares, L.; Adam, J.M. Seismic Assessment of a CFRP-Strengthened Masonry Chimney. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Struct. Build. 2009, 162, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, J.; Silvestre, N.; De Brito, J. Review on concrete nanotechnology. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2016, 20, 455–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X. On the use of nanotechnology to manage steel corrosion. Recent Pat. Eng. 2010, 4, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonczyk, J. Lessons Learned from the Northridge Earthquake (January 1994) with Respect to Design and Code Regulation on the Example of Steel Frame Behaviour (No. NEA-CSNI-R--2002-22, pp. 15–23). Available online: https://www.oecd-nea.org/upload/docs/application/pdf/2020-01/csni-r2002-22.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- A1 Sports VARIES PVC Coated Tarpaulin Fabric, Thickness: 3 mm. Available online: https://www.aajjo.com/product/a1-sports-varies-pvc-coated-tarpaulin-fabric-thickness-3-mm-in-mumbai-a1-sports-machines (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Tuhta, S.; Günday, F. Investigation of Steel Chimney Retrofitted with Nanocoating Under Earthquake Excitation Using FEM. Coatings 2025, 15, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surpam, M.; Tanawade, A. Analysis and Design of Pre-engineered Building Structure Using SAP2000. In Dynamic Behavior of Soft and Hard Materials; Springer Proceedings in Materials, Volume 36; Springer: Singapore, 2024; Volume 3, p. 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, X.Q.; Cao, N.V.; Lee, W.S.; Park, M.Y.; Chung, J.D.; Bae, K.J.; Kwon, O.K. Effect of coating thickness, binder and cycle time in adsorption cooling applications. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 184, 116265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, U.A.; Alam, M.A.; Abdo, H.S.; Anis, A.; Al-Zahrani, S.M. Synergistic effect of nanoparticles: Enhanced mechanical and corrosion protection properties of epoxy coatings incorporated with SiO2 and ZrO2. Polymers 2023, 15, 3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Modulus of Elasticity (kN/m2) | Poisson’s Ratio | Mass Per Unit Volume (kN/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fabric * | 3.5 × 106 | 0.40 | 1.4 |

| ZrO2 | 1.75 × 108 | 0.27 | 5.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuce, I.; Tuhta, S. Behavior of Flexible Biogas Digester Made of PVC-Coated PET Polyester Fabric with Increased Durability by Nanocoating Under Northridge (1994) Earthquake Effect. Coatings 2025, 15, 1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121401

Yuce I, Tuhta S. Behavior of Flexible Biogas Digester Made of PVC-Coated PET Polyester Fabric with Increased Durability by Nanocoating Under Northridge (1994) Earthquake Effect. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121401

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuce, Ismail, and Sertaç Tuhta. 2025. "Behavior of Flexible Biogas Digester Made of PVC-Coated PET Polyester Fabric with Increased Durability by Nanocoating Under Northridge (1994) Earthquake Effect" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121401

APA StyleYuce, I., & Tuhta, S. (2025). Behavior of Flexible Biogas Digester Made of PVC-Coated PET Polyester Fabric with Increased Durability by Nanocoating Under Northridge (1994) Earthquake Effect. Coatings, 15(12), 1401. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121401