The Impact of Humic Acid Coating on the Adsorption of Radionuclides (U-232) by Fe3O4 Particles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of HA Decorated Fe3O4 and Instrumentation

2.3. Adsorption Experiments

3. Results and Discussion

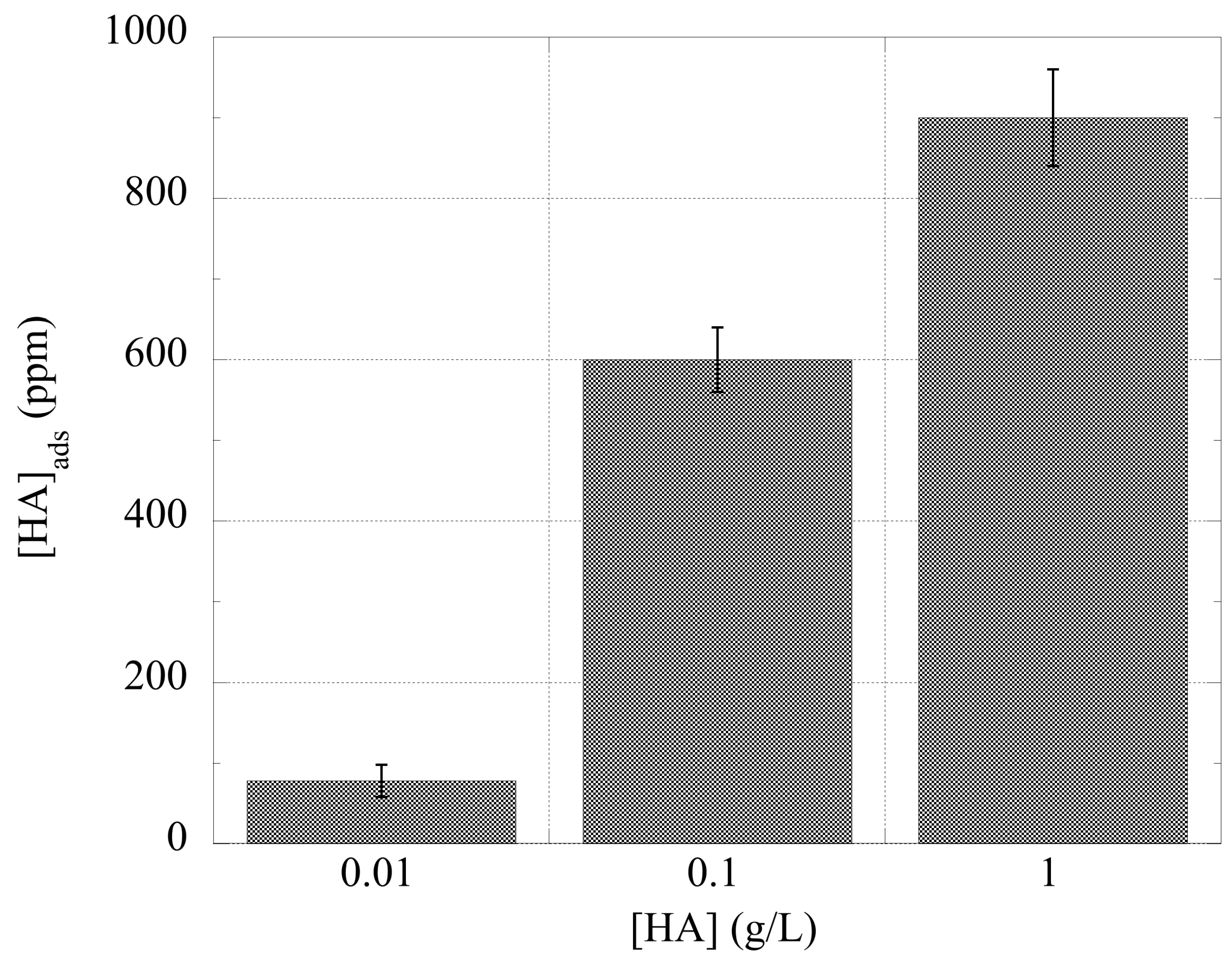

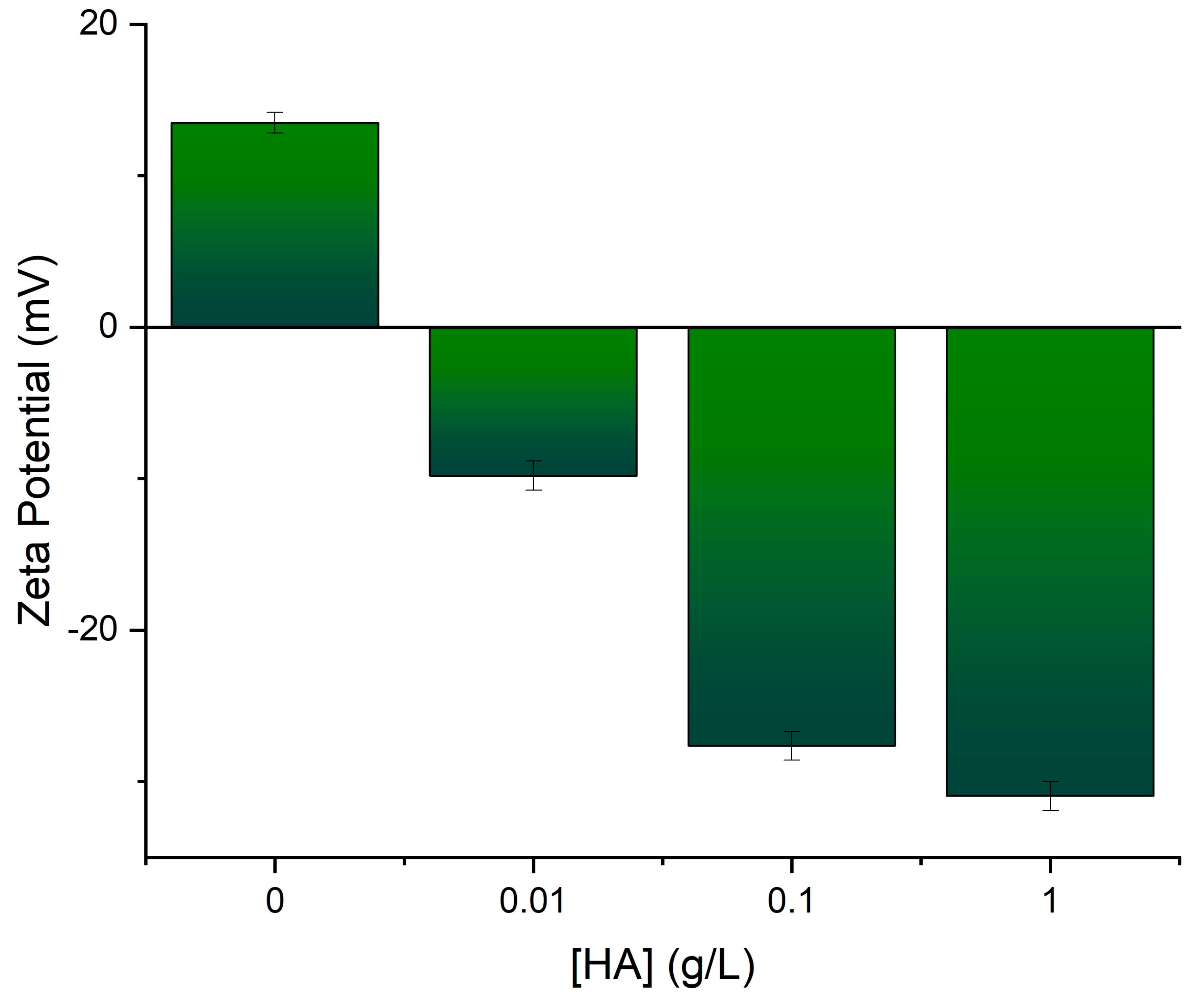

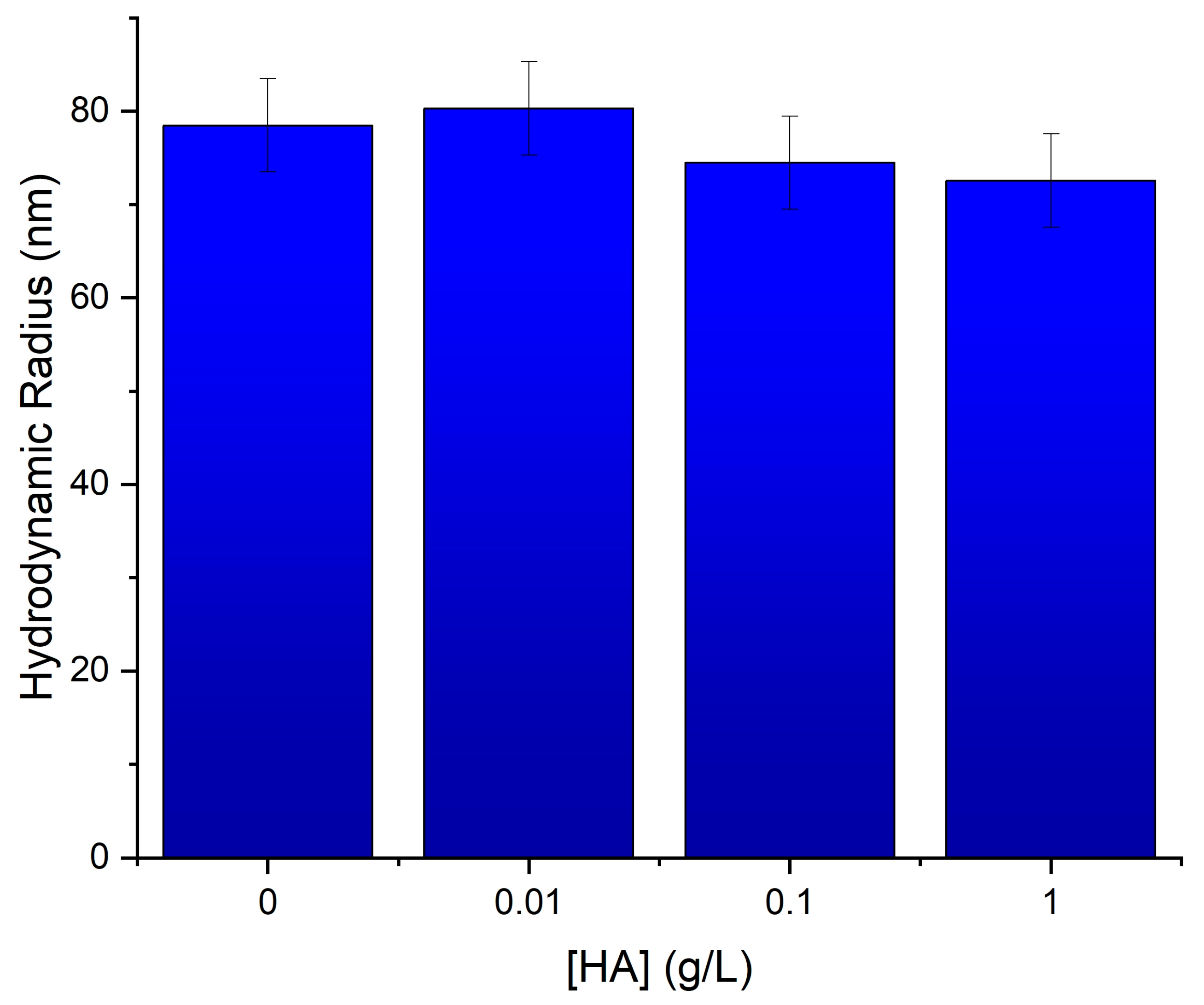

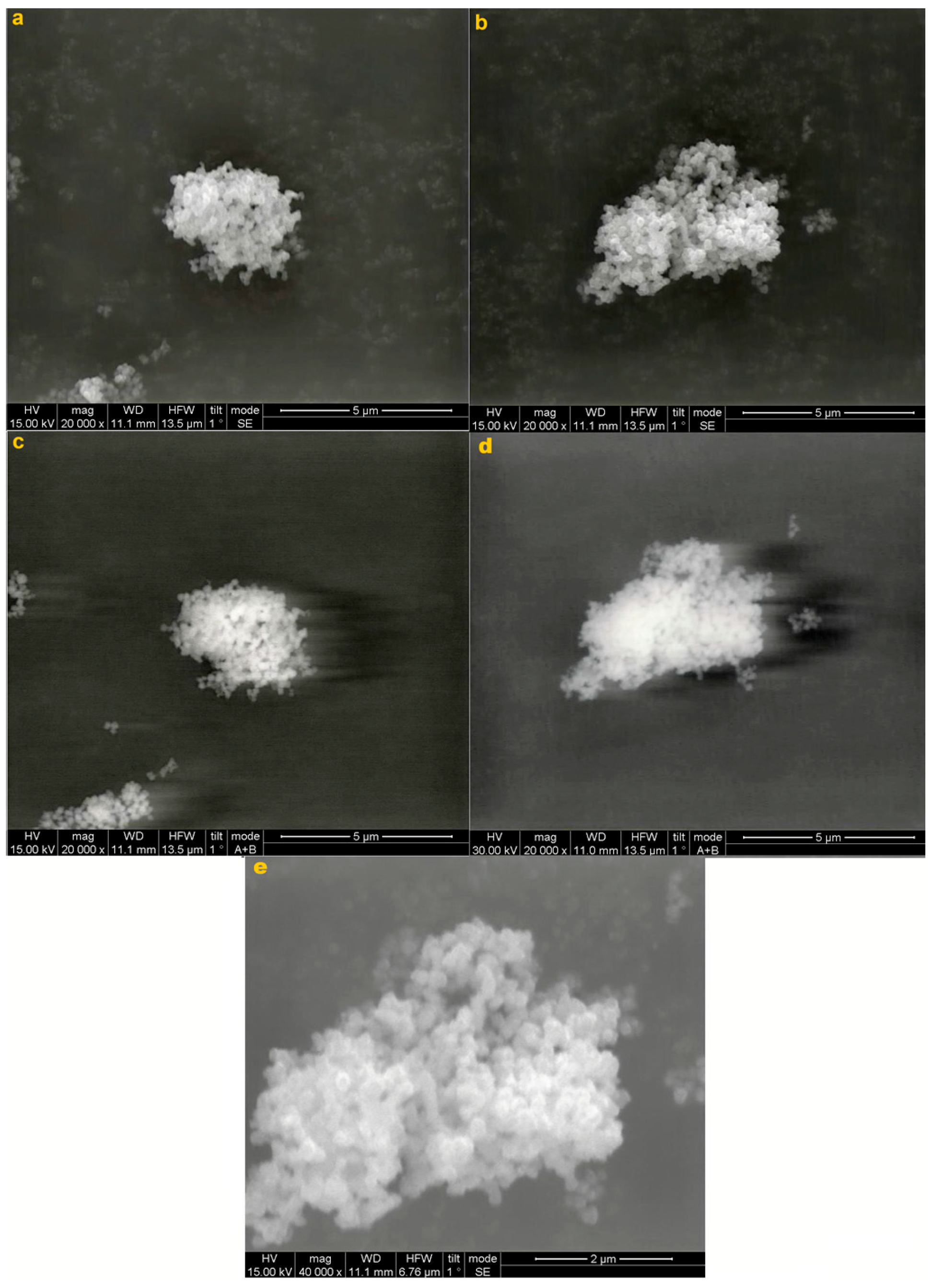

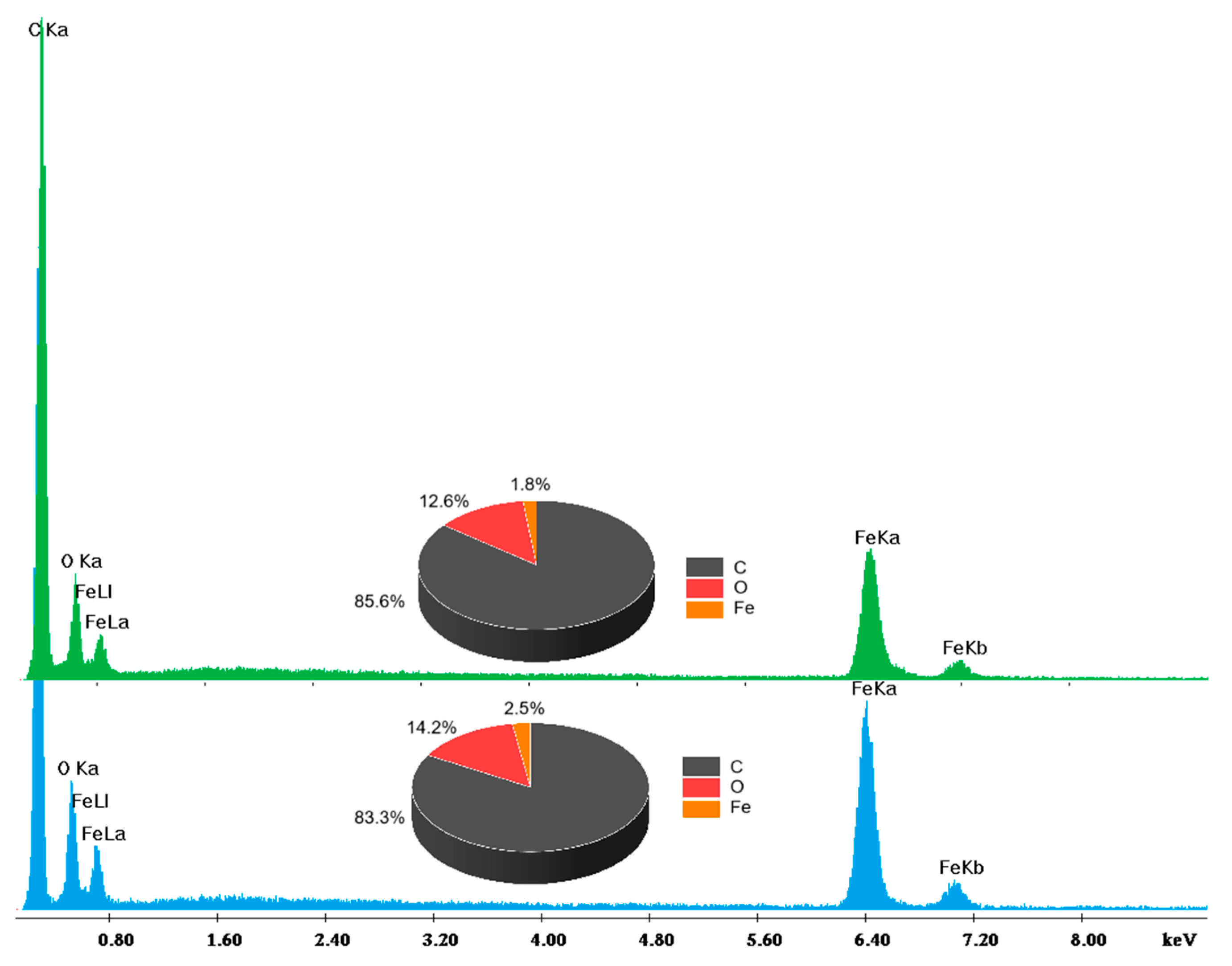

3.1. HA Functionalization of Fe3O4 and Characterization

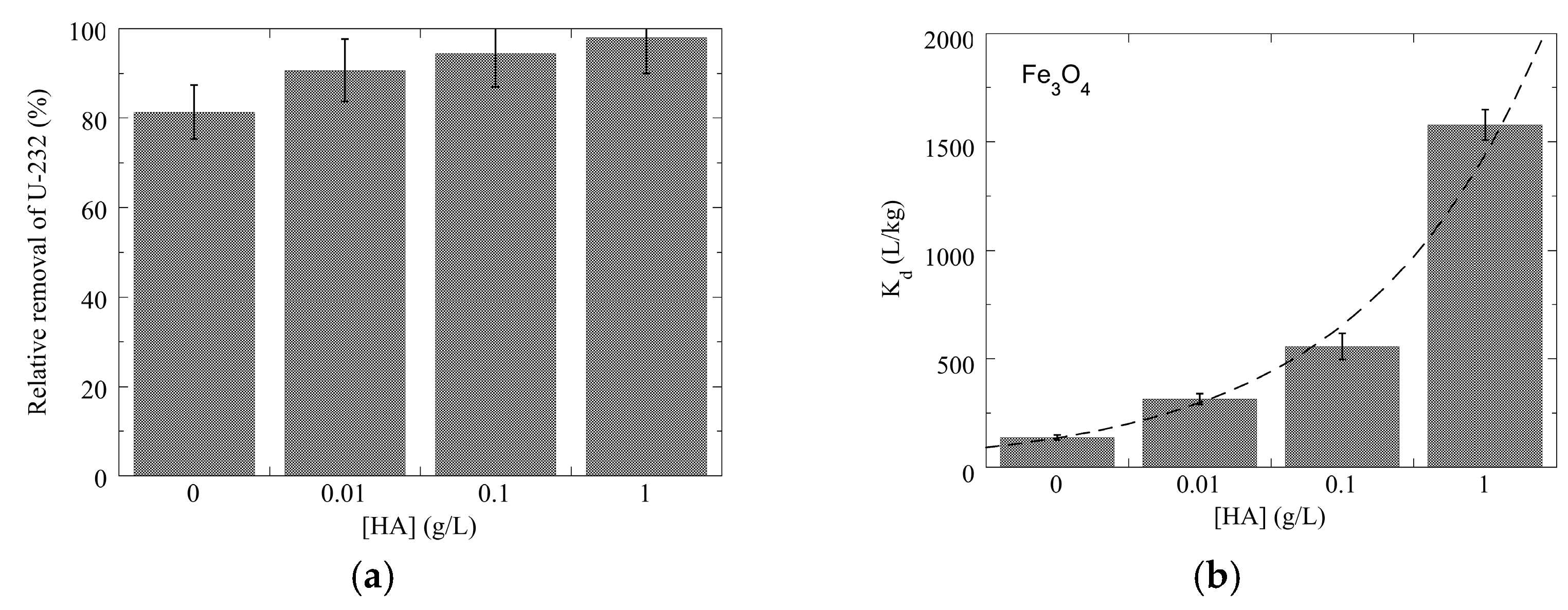

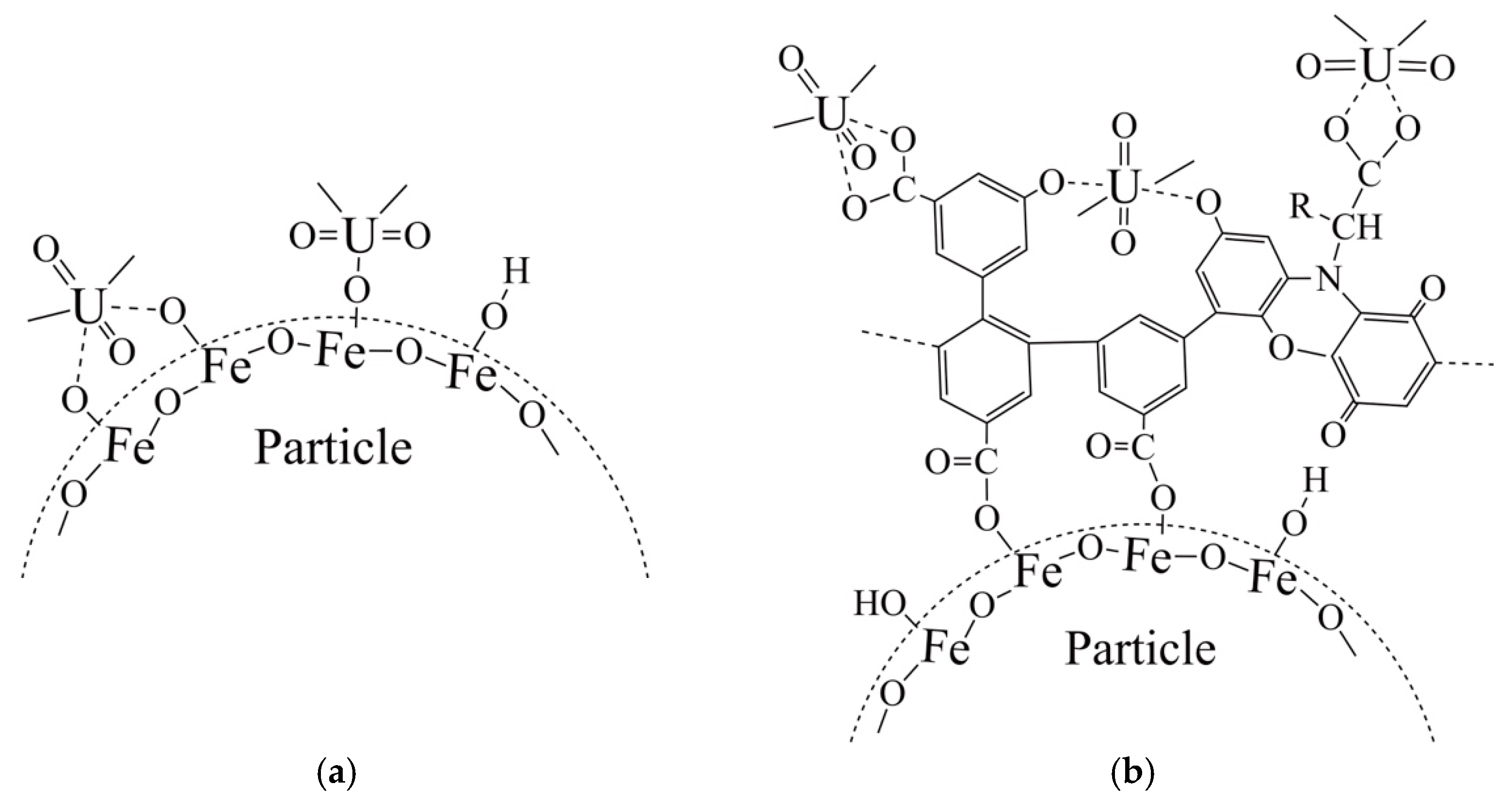

3.2. Adsorption Studies

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yi, S.; Chen, X.; Cao, X.; Yi, B.; He, W. Influencing factors and environmental effects of interactions between goethite and organic matter: A critical review. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1023277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.C.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, C.G.; Han, Y.U.; Park, J.A.; Park, S.B. Humic Acid Removal from Water by Iron-coated Sand: A Column Experiment. Environ. Eng. Res. 2009, 14, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.D.; Zevi, Y.; Kou, X.M.; Xiao, J.; Wang, X.J.; Jin, Y. Effect of dissolved organic matter on the stability of magnetite nanoparticles under different pH and ionic strength conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 3477–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spark, K.M.; Wells, J.D.; Johnson, B.B. The interaction of a humic acid with heavy metals. Soil Res. 1997, 35, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeide, K.; Sachs, S.; Bubner, M.; Reich, T.; Heise, K.H.; Bernhard, G. Interaction of uranium(VI) with various modified and unmodified natural and synthetic humic substances studied by EXAFS and FTIR spectroscopy. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2003, 351, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, I.; Antoniou, E.; Pashalidis, I. Enhanced radionuclide (U-232) adsorption by humic acid-coated microplastics. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galamboš, M.; Suchánek, P.; Rosskopfová, O. Sorption of anthropogenic radionuclides on natural and synthetic inorganic sorbents. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2012, 293, 613–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, A.A.; Ahmed, I.M.; Gamal, R.; Abo-El-Enein, S.A.; Helal, A.A. Sorption of uranium(VI) from aqueous solution using nanomagnetite particles; with and without humic acid coating. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2022, 331, 3005–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhang, H.; Ma, J.; Li, F.; Zeng, Q.; Hu, N.; Wang, Y.; Dai, Z.; Ding, D. Coupled variations of dissolved organic matter distribution and iron (oxyhydr)oxides transformation: Effects on the kinetics of uranium adsorption and desorption. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 436, 129298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Xu, C.; Xing, W.; Sun, L.; Kaplan, D.I.; Fujitake, N.; Yeager, C.M.; Schwehr, K.A.; Santschi, P.H. Radionuclide uptake by colloidal and particulate humic acids obtained from 14 soils collected worldwide. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, A.A.A.H.; Abdul-Kareem, M.B.; Mohammed, A.K.; Naushad, M.; . Ghfar, A.A.; Ahamad, T. Humic acid coated sand as a novel sorbent in permeable reactive barrier for environmental remediation of groundwater polluted with copper and cadmium ions. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 36, 101373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, I.; Antoniou, E.; Kinigopoulou, V.; Giannakoudakis, D.A.; Triantafyllidis, K.S.; Anastopoulos, I.; Pashalidis, I. Interaction of humic acids with PN6 microplastics and increased affinity for radionuclides (U-232). J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2025, 334, 4875–4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.K.; Jain, A.; Kumar, S.; Tomar, B.S.; Tomar, R.; Manchanda, V.K.; Ramanathan, S. Role of magnetite and humic acid in radionuclide migration in the environment. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2009, 106, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bondareva, L.; Fedorova, N. The effect of humic substances on metal migration at the border of sediment and water flow. Environ. Res. 2020, 190, 109985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Z.; Kuang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zheng, J.; Ouyang, G. Preparation of magnetic adsorbent and its adsorption removal of pollutants: An overview. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 167, 117241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernysh, Y.; Chubur, V.; Ablieieva, I.; Skvortsova, P.; Yakhnenko, O.; Skydanenko, M.; Plyatsuk, L.; Roubík, H. Soil Contamination by Heavy Metals and Radionuclides and Related Bioremediation Techniques: A Review. Soil Syst. 2024, 8, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, M.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Lee, J.K.; Kim, S.S.; Park, C.K.; Choi, J.W. Review and compilation of data on radionuclide migration and retardation for the performance assessment of a HLW repository in Korea. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2008, 40, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, E.; Raptopoulos, G.; Anastopoulos, I.; Giannakoudakis, D.A.; Arkas, M.; Paraskevopoulou, P.; Pashalidis, I. Uranium Removal from Aqueous Solutions by Aerogel-Based Adsorbents—A Critical Review. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milonjić, S.K.; Kopečni, M.M.; Ilić, Z.E. The point of zero charge and adsorption properties of natural magnetite. J. Radioanal. Chem. 1983, 78, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretzschmar, R.; Sticher, H.; Hesterberg, D. Effects of Adsorbed Humic Acid on Surface Charge and Flocculation of Kaolinite. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1997, 61, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, S.; Brendler, V.; Geipel, G. Uranium(VI) complexation by humic acid under neutral pH conditions studied by laser-induced fluorescence spectroscopy. Radiochim. Acta 2007, 95, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Guinart, O.; Kaplan, D.; Rigol, A.; Vidal, M. Deriving probabilistic soil distribution coefficients (Kd). Part 1: General approach to decreasing and describing variability and example using uranium Kd values. J. Environ. Radioactiv. 2020, 222, 106362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beza, P.; Anastopoulos, I.; Arkas, M.; Bompotis, T.; Giannakopoulos, K.; Ioannidis, I.; Pashalidis, I. The Impact of Humic Acid Coating on the Adsorption of Radionuclides (U-232) by Fe3O4 Particles. Coatings 2025, 15, 1399. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121399

Beza P, Anastopoulos I, Arkas M, Bompotis T, Giannakopoulos K, Ioannidis I, Pashalidis I. The Impact of Humic Acid Coating on the Adsorption of Radionuclides (U-232) by Fe3O4 Particles. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1399. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121399

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeza, Paraskevi, Ioannis Anastopoulos, Michael Arkas, Theofanis Bompotis, Konstantinos Giannakopoulos, Ioannis Ioannidis, and Ioannis Pashalidis. 2025. "The Impact of Humic Acid Coating on the Adsorption of Radionuclides (U-232) by Fe3O4 Particles" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1399. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121399

APA StyleBeza, P., Anastopoulos, I., Arkas, M., Bompotis, T., Giannakopoulos, K., Ioannidis, I., & Pashalidis, I. (2025). The Impact of Humic Acid Coating on the Adsorption of Radionuclides (U-232) by Fe3O4 Particles. Coatings, 15(12), 1399. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121399