The Public Health Risks of Colistin Resistance in Dogs and Cats: A One Health Perspective Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Use of Colistin in Veterinary Medicine

3. Colistin Resistance

3.1. Intrinsic Resistance Mechanisms

3.2. Acquired Resistance Mechanisms

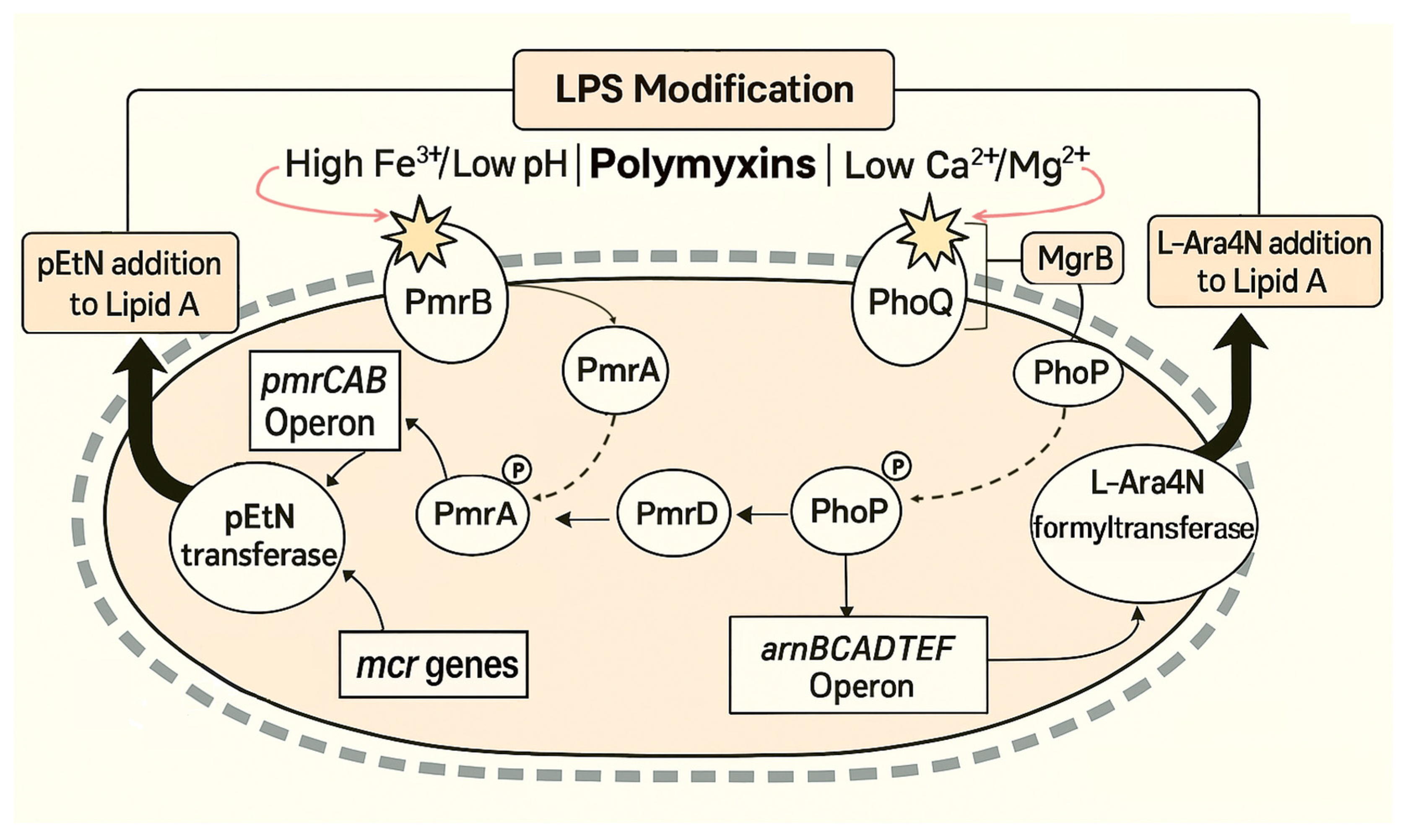

3.2.1. PmrAB Two-Component System

3.2.2. PhoPQ Two-Component System

3.2.3. Plasmid-Mediated Colistin Resistance

| Region | Country | Year | Host | Source | Bacterial Species | Mobile Genetic Elements | Other Antibiotic Resistance Genes in the Same Plasmid | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mcr-1 | ||||||||

| Africa | Algeria | 2025 | Cat | Commensal (rectal swab) | Enterobacter kobei | N/A | N/A | [58] |

| Asia | China | 2015 | Cat | Infection (diarrhea) | Escherichia coli | IncX3-X4 plasmid, ISAba125 | blaNDM-5 | [5] |

| China | 2016 | Dog and Cat | Commensal (feces) | Escherichia coli | N/A | N/A | [15] | |

| China | 2016 | Cat | Commensal (rectal swab) | Escherichia coli | IncX3-X4 plasmid, ISAba125 | blaNDM-5 | [4] | |

| China | 2017 | Dog | Commensal (rectal swabs) | Escherichia coli | IncI2, IncX4 and IncHI2 plasmids, ISApl1 | blaCTX-M-14 | [59] | |

| China | 2017 | Dog | Commensal (feces) | Escherichia coli | IncX4-like plasmid, ISEcp1 | blaCTX-M-55 | [60] | |

| China | 2017 | Dog and Cat | Commensal (nasal and rectal swabs) | Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae | N/A | N/A | [61] | |

| China | 2018 | Dog and Cat | Commensal (feces) and Infection (urine, nasal secretion, diarrhea) | Escherichia coli | IncHI2 plasmid and ISApl1, IncI2 | blaCTX-M-14, blaCTX-M-64, floR and fosA3 | [62] | |

| China | 2018 | Cat | Infection (tracheal lavage) | Klebsiella pneumoniae | IncX4 plasmid, IS26 | None | [63] | |

| China | 2019 | Dog | Infection | Escherichia coli | IncI2 plasmid | blaCTX-M-55 | [64] | |

| China | 2020 | Dog | Commensal (feces) | Escherichia coli | IncX4 plasmid, IS26 | None | [65] | |

| China | 2021 | Dog | Commensal (feces) | Klebsiella pneumoniae | N/A | N/A | [66] | |

| South Korea | 2020 | Dog | Infection (diarrhea) | Escherichia coli | IncI2 plasmid | None | [67] | |

| Taiwan | 2019 | Dog | Infection (UTI) | Enterobacter cloacae and Klebsiella pneumoniae | None | N/A | [68] | |

| Europe | France | 2019–2020 | Dog and Cat | Commensal (feces) | Escherichia coli, Rahnella aquatili | N/A | N/A | [69] |

| Germany | 2011 | Dog and Cat | Commensal (feces) | Escherichia coli | IncX4 plasmid | None | [70] | |

| Portugal | 2018 | Dog | Commensal (feces) | Escherichia coli | IncHI2A plasmid | sul1, dfrA1, aadA1 | [14] | |

| South America | Argentina | 2019 | Dog | Infection (UTI) | Escherichia coli | IncI2 plasmid | None | [71] |

| Brazil | 2020 | Dog | Infection (UTI, abdominal seroma, nasal secretion) | Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., Enterobacter spp. | N/A | N/A | [72] | |

| Brazil | 2021 | Cat | Infection (UTI) | Klebsiella pneumoniae | N/A | N/A | [73] | |

| Ecuador | 2016 | Dog | Commensal (rectal swab) | Escherichia coli | IncI2 | None | [74] | |

| Ecuador | 2019 | Dog | Commensal (feces) | Escherichia coli | N/A | N/A | [75] | |

| mcr-2 | ||||||||

| Asia | China | 2019 | Dog | Commensal (feces) | Klebsiella pneumoniae | N/A | N/A | [66] |

| mcr-3 | ||||||||

| Asia | China | 2019 | Dog | Commensal (feces) | Klebsiella pneumoniae | N/A | N/A | [66] |

| China | 2020 | Dog | Commensal (feces) | Escherichia coli | IncP1 plasmid, TnAs2, IS26 | None | [65] | |

| Taiwan | 2021 | Dog | Infection | Escherichia coli | N/A | N/A | [76] | |

| mcr-4 | ||||||||

| Asia | China | 2019 | Dog | Commensal (feces) | Klebsiella pneumoniae | N/A | N/A | [66] |

| mcr-5 | ||||||||

| Asia | China | 2019 | Dog | Commensal (feces) | Klebsiella pneumoniae | N/A | N/A | [66] |

| mcr-8 | ||||||||

| Asia | China | 2017 | Cat | Infection (UTI) | Klebsiella pneumoniae | IncFIA (HI1)/FII(K) plasmid, ISEcl1, ISKpn26 | None | [77] |

| mcr-9 | ||||||||

| Africa | Egypt | 2017 | Dog and Cat | Infection (ocular swab, nasal swab) | Enterobacter hormaechei | IncHI2 | blaVIM-4 | [78] |

| Asia | China | 2019 | Dog | Commensal (feces) | Klebsiella pneumoniae | N/A | N/A | [66] |

| Japan | 2021 | Cat | Infection (nasal cavity swab) | Enterobacter asburiae | IncHI2 plasmid | aac(6′)-Ib3, aph(6)-Id, blaTEM-1B, dfrA19, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, catA2, tetD | [79] | |

| Thailand | 2022 | Cat | Infection (abdominal fluid) | Enterobacter hormaechei | IncHI2/2A plasmid | N/A | [80] | |

| Europe | UK | 2021 | Dog | Infection (SSTI) | Escherichia coli | N/A | N/A | [81] |

| mcr-10 | ||||||||

| Asia | China | 2019 | Dog | Infection | Klebsiella pneumoniae | N/A | N/A | [66] |

| Japan | 2021 | Dog | Infection (pus) | Enterobacter roggenkampii | IncFIB plasmid | None | [82] | |

4. Methods for Colistin Susceptibility Testing

4.1. Challenges and Technical Limitations

4.2. Reference Methods: Broth Microdilution

Commercial Microdilution Systems

- BD Phoenix: This platform allows for manual or automated inoculation and tests colistin concentrations from 0.5 to 4 µg/mL, with turnaround times of 6–16 h. While it reliably detects plasmid-mediated colistin resistance, BD Phoenix (BD Diagnostics, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) has a high false-susceptible rate (~15%) and shows limited ability to identify heteroresistant populations [95].

- MicroScan: Requires manual inoculation, incubation for 16–20 h and has a narrow MIC range (2–4 µg/mL) [101]. MicroScan (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) reported performance varies substantially by species, with high categorical agreement for Enterobacterales (99.3%) but poor for non-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli (64.1%). A high rate of major errors (26.9%) was reported, mostly due to MIC overestimation in non-fermenters [102,103].

- Sensititre: Sensititre (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) features a wide MIC range of 0.12–128 µg/mL and incubation times of 18–24 h, with inoculation possible either manually or via autoinoculator. In one study, the system achieved 96% categorical agreement without false susceptibility, representing the most reliable performance among commercial microdilution platforms [84].

- UMIC: The UMIC Colistine kit (Biocentric, Bandol, France) is a manual-based system designed for individual isolate testing. This system covers a MIC range from 0.0625 to 64 µg/mL, with a required incubation time of 18–24 h. Studies indicate good reproducibility and high categorical agreement, with 92.5% for Enterobacterales and 89.7% for non-fermenting Gram-negative bacteria, while essential agreement ranges from 94–100% for Enterobacterales but may fall below 80% for non-fermenters [103,104,105].

- VITEK2: The system is fully automated and provides rapid results within 4–10 h, testing colistin concentrations from 0.5 to 16 µg/mL. VITEK2 (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) shows poor sensitivity for detecting resistant strains and heteroresistant subpopulations, leading to false susceptibility readings [106,107].

4.3. Molecular Approaches for Resistance Detection

- Conventional PCR: Standard PCR assays allow detection of individual mcr genes (simplex) or multiple variants in the same reaction (multiplex). Primer sets have been published for mcr-1 through mcr-5 [108] and mcr-6 to mcr-9 [109], enabling specific detection directly from bacterial isolates. Most recently a tenfold multiplex PCR method for mcr-1 to mcr-10 was developed showing a high specificity [110]. Results can generally be obtained within the same working day. These assays are considered reference methods for validating novel molecular tools.

- Real-Time PCR (qPCR): Several quantitative PCR assays have been developed to detect mcr genes directly from cultured bacteria, clinical samples, or stools. An SYBR Green-based assay demonstrated 100% specificity and a limit of detection of 102 CFU, with no false-positive results. Importantly, the assay was also conclusive when applied to stool samples spiked with mcr-1-positive E. coli [111]. Similarly, a TaqMan probe-based qPCR with a detection range of 101–108 DNA copies achieved 100% specificity when applied to bacterial isolates and fecal samples from chickens [112]. More recently, a multiplex TaqMan real-time PCR assay was introduced for the simultaneous detection of mcr-1 to mcr-10, offering high specificity, sensitivity, and reproducibility, and thus representing a powerful tool for comprehensive resistance surveillance [113].

- Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS): Screens the entire bacterial genome, identifying plasmid-mediated mcr genes and chromosomal mutations. Specificity approaches 100%, with a turnaround time of 1–2 days, depending on sequencing platform. WGS also enables high-resolution epidemiological typing but requires bioinformatics expertise and higher costs [108,109,114].

- Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP): The eazyplex® SuperBug kit (Amplex Biosystems GmbH, Giessen, Germany) detected mcr-1 with 100% sensitivity and specificity, delivering results in ~20 min. However, the system is limited to six samples per hour, and has not been validated for direct detection without pre-culture [115]. A multiplex LAMP assay later expanded detection to mcr-1 through mcr-5, also achieving 100% accuracy [116].

- DNA microarrays: Microarray-based assays enable parallel detection of numerous resistance determinants. The commercial Check-MDR CT103XL system (Check-Points Health, Wageningen, The Netherlands) can simultaneously detect mcr-1 and mcr-2 genes along with a wide range of β-lactamases encoding genes directly from Enterobacterales cultures. Results are available in approximately 6.5 h, with reported 100% sensitivity and specificity [117]. While highly powerful for surveillance, the method remains costly and technically complex, which limits its applicability for routine clinical diagnostics.

4.4. Novel and Emerging Assays

- Rapid Polymyxin NP test: This colorimetric assay detects resistance based on glucose metabolism in the presence of colistin. It has shown specificity and sensitivity of 99.3% and 95.4%, respectively, compared to BMD [118]. Importantly, it can identify heteroresistant populations and plasmid-mediated MCR-1 producers. The commercial version (Rapid Polymyxin NP test; ELITechGroup Microbiology, Puteaux, France) provides results within 2–3 h, making it suitable for routine diagnostics.

- Lateral flow immunoassay (LFIA): Monoclonal antibody-based LFIA (NG Biotech, Guipry, France) enables rapid detection of MCR-1-producing isolates directly from bacterial colonies. It shows 100% sensitivity and 98% specificity, but does not detect other producers of other MCR-variants [119]. Its speed (<15 min), low cost, and simplicity make it highly attractive for implementation in clinical and veterinary microbiology laboratories.

- Micromax technology: The Micromax assay (Halotech DNA SL, Madrid, Spain) is based on detection of DNA release following cell wall damage in the presence of colistin. It demonstrated 100% sensitivity and 96% specificity in A. baumannii, with results obtained within 3.5 h [120]. However, its technical complexity and cost currently limit widespread use.

5. Epidemiology of Colistin Resistance in Companion Animals

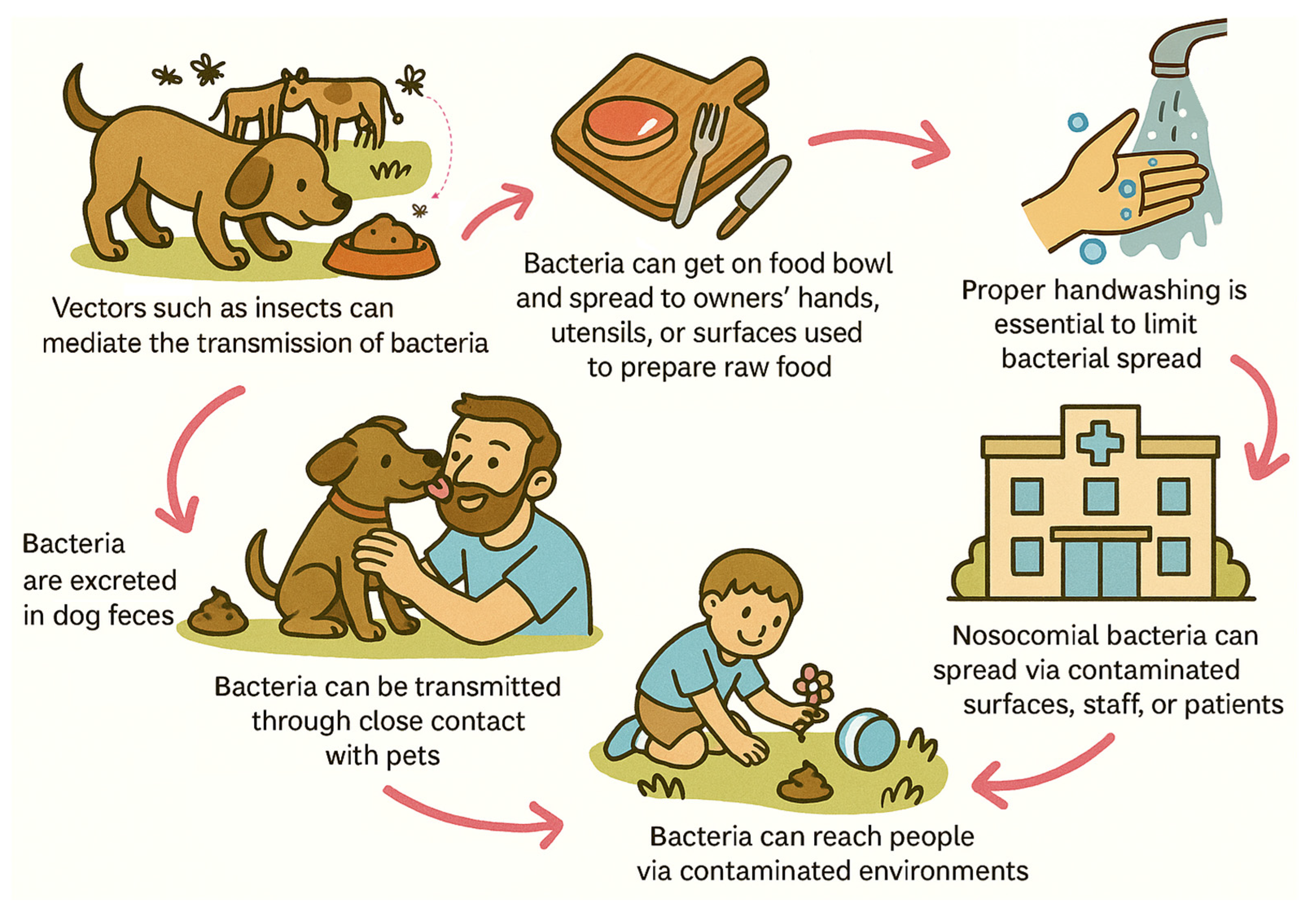

6. Transmission Potential and Dissemination Pathways

6.1. Companion Animals as a Reservoir for AMR Transmission

6.2. Evidence of Interhost Transmission of Resistant Bacteria

6.3. Plasmid-Mediated Dissemination of Resistance Genes

7. Strategies to Reduce Dissemination Risks

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| BMD | Broth microdilution |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| ECDC | European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| EU | European Union |

| EUCAST | European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| HPCIA | Highest priority critically important antimicrobials |

| MDR | Multidrug-resistant |

| MGE | Mobile genetic elements |

| MHB | Mueller-Hinton broth |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| L-Ara4N | 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose |

| PDR | Pan-drug-resistant |

| pEtN | Phosphoethanolamine |

| UTI | Urinary tract infection |

| XDR | Extensively drug-resistant |

References

- Husna, A.; Rahman, M.M.; Badruzzaman, A.T.M.; Sikder, M.H.; Islam, M.R.; Rahman, M.T.; Alam, J.; Ashour, H.M. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases (ESBL): Challenges and Opportunities. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: A Systematic Analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrancianu, C.O.; Popa, L.I.; Bleotu, C.; Chifiriuc, M.C. Targeting Plasmids to Limit Acquisition and Transmission of Antimicrobial Resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuang, X.; Yang, R.; Ye, X.; Sun, J.; Liao, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Y. NDM-5-Producing Escherichia coli Co-Harboring Mcr-1 Gene in Companion Animals in China. Animals 2022, 12, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Yang, R.-S.; Zhang, Q.; Feng, Y.; Fang, L.-X.; Xia, J.; Li, L.; Lv, X.-Y.; Duan, J.-H.; Liao, X.-P.; et al. Co-Transfer of BlaNDM-5 and Mcr-1 by an IncX3–X4 Hybrid Plasmid in Escherichia coli. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 16176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, Y.; Kurosasa, A.; Tsuchiya, A.; Takakuta, K. A New Antibiotic ‘Colistin’ Produced by Spore-Forming Soil Bacteria. J. Antibiot. 1950, 3, 457–458. [Google Scholar]

- Landman, D.; Georgescu, C.; Martin, D.A.; Quale, J. Polymyxins Revisited. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 21, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Kasiakou, S.K.; Saravolatz, L.D. Colistin: The Revival of Polymyxins for the Management of Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacterial Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 40, 1333–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, N.; Aranzana-Climent, V.; Magréault, S.; Marchand, S.; Couet, W. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Colistin. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2017, 56, 1441–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO’s List of Medically Important Antimicrobials: A Risk Management Tool for Mitigating Antimicrobial Resistance Due to Non-Human Use; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0; IGO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; ISBN 9789240084612.

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Antimicrobial Advice Ad Hoc Expert Group Updated Advice on the Use of Colistin Products in Animals within the European Union: Development of Resistance and Possible Impact on Human and Animal Health; European Medicines Agency (EMA): Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Elbediwi, M.; Li, Y.; Paudyal, N.; Pan, H.; Li, X.; Xie, S.; Rajkovic, A.; Feng, Y.; Fang, W.; Rankin, S.C.; et al. Global Burden of Colistin-Resistant Bacteria: Mobilized Colistin Resistance Genes Study (1980–2018). Microorganisms 2019, 7, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skov, R.L.; Monnet, D.L. Plasmid-Mediated Colistin Resistance (Mcr-1 Gene): Three Months Later, the Story Unfolds. Eurosurveillance 2016, 21, 30155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, J.; Moreira da Silva, J.; Frosini, S.-M.; Loeffler, A.; Weese, S.; Perreten, V.; Schwarz, S.; Gama, L.T.; Amaral, A.J.; Pomba, C. Mcr-1 Sharing between Co-Habiting Dogs and Humans in the Community, Lisbon, Portugal, 2018–2020. Eurosurveillance 2022, 27, 2101144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Doi, Y.; Huang, X.; Li, H.; Zhong, L.-L.; Zeng, K.-J.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Patil, S.; Tian, G.-B. Possible Transmission of Mcr-1– Harboring Escherichia coli between Companion Animals and Humans. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 1679–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialvaei, A.Z.; Samadi Kafil, H. Colistin, Mechanisms and Prevalence of Resistance. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2015, 31, 707–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catry, B.; Cavaleri, M.; Baptiste, K.; Grave, K.; Grein, K.; Holm, A.; Jukes, H.; Liebana, E.; Navas, A.L.; Mackay, D.; et al. Use of Colistin-Containing Products within the European Union and European Economic Area (EU/EEA): Development of Resistance in Animals and Possible Impact on Human and Animal Health. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2015, 46, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Ban on Antibiotics as Growth Promoters in Animal Feed Enters into Effect. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_05_1687 (accessed on 30 March 2024).

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Sales of Veterinary Antimicrobial Agents in 31 European Countries in 2022—Trends from 2010 to 2022: Thirteenth ESVAC Report; EMA/299538/2023; EMA: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC); European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); European Medicines Agency (EMA). Third Joint Inter-agency Report on Integrated Analysis of Consumption of Antimicrobial Agents and Occurrence of Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacteria from Humans and Food-producing Animals in the EU/EEA. EFSA J. 2021, 19, e06712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. European Sales and Use of Antimicrobials for Veterinary Medicine (ESUAvet)—Annual Surveillance Report for 2023; European Medicines Agency: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, C.; Zhong, L.; Zhong, Z.; Doi, Y.; Shen, J.; Wang, Y.; Ma, F.; Ahmed, M.A.E.E. Prevalence of Mcr-1 in Colonized Inpatients, China, 2011–2019. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 2502–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joosten, P.; Ceccarelli, D.; Odent, E.; Sarrazin, S.; Graveland, H.; Van Gompel, L.; Battisti, A.; Caprioli, A.; Franco, A.; Wagenaar, J.A.; et al. Antimicrobial Usage and Resistance in Companion Animals: A Cross-Sectional Study in Three European Countries. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnepf, A.; Kramer, S.; Wagels, R.; Volk, H.A.; Kreienbrock, L. Evaluation of Antimicrobial Usage in Dogs and Cats at a Veterinary Teaching Hospital in Germany in 2017 and 2018. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 689018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makita, K.; Sugahara, N.; Nakamura, K.; Matsuoka, T.; Sakai, M.; Tamura, Y. Current Status of Antimicrobial Drug Use in Japanese Companion Animal Clinics and the Factors Associated With Their Use. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 705648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, R.A.; Chopra, I. Leakage of Periplasmic Proteins from Escherichia coli Mediated by Polymyxin B Nonapeptide. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1986, 29, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaitan, A.O.; Morand, S.; Rolain, J.M. Mechanisms of Polymyxin Resistance: Acquired and Intrinsic Resistance in Bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, J.S. The Salmonella PmrAB Regulon: Lipopolysaccharide Modifications, Antimicrobial Peptide Resistance and More. Trends Microbiol. 2008, 16, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada, A.; Porrero, M.C.; Téllez, S.; Palomo, G.; García, M.; Domínguez, L. Polymorphism of Genes Encoding PmrAB in Colistin-Resistant Strains of Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica Isolated from Poultry and Swine. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diene, S.M.; Merhej, V.; Henry, M.; El Filali, A.; Roux, V.; Robert, C.; Azza, S.; Gavory, F.; Barbe, V.; La Scola, B.; et al. The Rhizome of the Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacter aerogenes Genome Reveals How New “Killer Bugs” Are Created Because of a Sympatric Lifestyle. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaitan, A.O.; Diene, S.M.; Kempf, M.; Berrazeg, M.; Bakour, S.; Gupta, S.K.; Thongmalayvong, B.; Akkhavong, K.; Somphavong, S.; Paboriboune, P.; et al. Worldwide Emergence of Colistin Resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae from Healthy Humans and Patients in Lao PDR, Thailand, Israel, Nigeria and France Owing to Inactivation of the PhoP/PhoQ Regulator MgrB: An Epidemiological and Molecular Study. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2014, 44, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, N.S.; Yang, J.; Bulitta, J.B.; Tsuji, B.T. Impact of Two-Component Regulatory Systems PhoP-PhoQ and PmrA-PmrB on Colistin Pharmacodynamics in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 3453–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Groisman, E.A. Signal-specific Temporal Response by the Salmonella PhoP/PhoQ Regulatory System. Mol. Microbiol. 2014, 91, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groisman, E.A. The Pleiotropic Two-Component Regulatory System PhoP-PhoQ. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 1835–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannatelli, A.; Giani, T.; D’Andrea, M.M.; Di Pilato, V.; Arena, F.; Conte, V.; Tryfinopoulou, K.; Vatopoulos, A.; Rossolini, G.M. MgrB Inactivation Is a Common Mechanism of Colistin Resistance in KPC-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae of Clinical Origin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 5696–5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-H.; Lin, T.-L.; Pan, Y.-J.; Wang, Y.-P.; Lin, Y.-T.; Wang, J.-T. Colistin Resistance Mechanisms in Klebsiella pneumoniae Strains from Taiwan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 2909–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippa, A.M.; Goulian, M. Feedback Inhibition in the PhoQ/PhoP Signaling System by a Membrane Peptide. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5, e1000788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.; Walsh, T.R.; Yi, L.X.; Zhang, R.; Spencer, J.; Doi, Y.; Tian, G.; Dong, B.; Huang, X.; et al. Emergence of Plasmid-Mediated Colistin Resistance Mechanism MCR-1 in Animals and Human Beings in China: A Microbiological and Molecular Biological Study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, Z.; Yin, W.; Shen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Shen, J.; Walsh, T.R. Epidemiology of Mobile Colistin Resistance Genes Mcr-1 to Mcr-9. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 3087–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, S.R.; Di Pilato, V.; Doi, Y.; Feldgarden, M.; Haft, D.H.; Klimke, W.; Kumar-Singh, S.; Liu, J.-H.; Malhotra-Kumar, S.; Prasad, A.; et al. Proposal for Assignment of Allele Numbers for Mobile Colistin Resistance (Mcr) Genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 2625–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, L.; Manageiro, V.; Correia, I.; Amaro, A.; Albuquerque, T.; Themudo, P.; Ferreira, E.; Caniça, M. Revealing Mcr-1-Positive ESBL-Producing Escherichia coli Strains among Enterobacteriaceae from Food-Producing Animals (Bovine, Swine and Poultry) and Meat (Bovine and Swine), Portugal, 2010–2015. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 296, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones-Dias, D.; Manageiro, V.; Ferreira, E.; Barreiro, P.; Vieira, L.; Moura, I.B.; Caniça, M. Architecture of Class 1, 2, and 3 Integrons from Gram Negative Bacteria Recovered among Fruits and Vegetables. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro-Almeida, M.; Mourão, J.; Novais, Â.; Pereira, S.; Freitas-Silva, J.; Ribeiro, S.; da Costa, P.M.; Peixe, L.; Antunes, P. High Diversity of Pathogenic Escherichia coli Clones Carrying Mcr-1 among Gulls Underlines the Need for Strategies at the Environment–livestock–human Interface. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 24, 4702–4713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, R.T.; Cunha, M.V.; Araujo, D.; Ferreira, H.; Fonseca, C.; Palmeira, J.D. Emergence of Colistin Resistance Genes (Mcr-1) in Escherichia coli among Widely Distributed Wild Ungulates. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 291, 118136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas Palmeira, J.; Cunha, M.V.; Ferreira, H.; Fonseca, C.; Tinoco Torres, R. Worldwide Disseminated IncX4 Plasmid Carrying Mcr-1 Arrives to Wild Mammal in Portugal. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0124522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.-H.; Feng, Y. Towards Understanding MCR-like Colistin Resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2018, 26, 794–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, B.B.; Lammens, C.; Ruhal, R.; Kumar-Singh, S.; Butaye, P.; Goossens, H.; Malhotra-Kumar, S. Identification of a Novel Plasmid-Mediated Colistin-Resistance Gene, Mcr-2, in Escherichia coli, Belgium, June 2016. Eurosurveillance 2016, 21, 30280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Li, H.; Shen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, R.; Walsh, T.R.; Shen, J.; Wang, Y. Novel Plasmid-Mediated Colistin Resistance Gene Mcr-3 in Escherichia coli. MBio 2017, 8, e00543-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carattoli, A.; Villa, L.; Feudi, C.; Curcio, L.; Orsini, S.; Luppi, A.; Pezzotti, G.; Magistrali, C.F. Novel Plasmid-Mediated Colistin Resistance Mcr-4 Gene in Salmonella and Escherichia coli, Italy 2013, Spain and Belgium, 2015 to 2016. Eurosurveillance 2017, 22, 30589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowiak, M.; Fischer, J.; Hammerl, J.A.; Hendriksen, R.S.; Szabo, I.; Malorny, B. Identification of a Novel Transposon-Associated Phosphoethanolamine Transferase Gene, Mcr-5, Conferring Colistin Resistance in d-Tartrate Fermenting Salmonella enterica Subsp. Enterica Serovar Paratyphi B. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 3317–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuOun, M.; Stubberfield, E.J.; Duggett, N.A.; Kirchner, M.; Dormer, L.; Nunez-Garcia, J.; Randall, L.P.; Lemma, F.; Crook, D.W.; Teale, C.; et al. Mcr-1 and Mcr-2 (Mcr-6.1) Variant Genes Identified in Moraxella Species Isolated from Pigs in Great Britain from 2014 to 2015. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 2745–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-Q.; Li, Y.-X.; Lei, C.-W.; Zhang, A.-Y.; Wang, H.-N. Novel Plasmid-Mediated Colistin Resistance Gene Mcr-7.1 in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 1791–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Yin, W.; Wang, S.; Zhang, S.; Shen, J.; Shen, Z.; Wang, Y. Emergence of a Novel Mobile Colistin Resistance Gene, Mcr-8, in NDM-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, L.M.; Gaballa, A.; Guldimann, C.; Sullivan, G.; Henderson, L.O.; Wiedmann, M. Identification of Novel Mobilized Colistin Resistance Gene Mcr-9 in a Multidrug-Resistant, Colistin-Susceptible Salmonella Enterica Serotype Typhimurium Isolate. MBio 2019, 10, e00853-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Feng, Y.; Liu, L.; Wei, L.; Kang, M.; Zong, Z. Identification of Novel Mobile Colistin Resistance Gene Mcr-10. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Shen, J.; Wu, C. Early Emergence of Mcr-1 in Escherichia coli from Food-Producing Animals. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Van Dorp, L.; Shaw, L.P.; Bradley, P.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Jin, L.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Rieux, A.; et al. The Global Distribution and Spread of the Mobilized Colistin Resistance Gene Mcr-1. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaziz, A.; Bendjama, E.; Chelaghma, W.; Zaatout, N.; Farouk, K.; Beghami, F.Z.; Boukhanoufa, R.; Demikha, A.; Rolain, J.-M.; Loucif, L. Detection and Genetic Characterisation of ESBL, Carbapenemase, and Mcr-1 Genes in Gram-Negative Bacterial Isolates from Companion Animals in Batna, Algeria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 2025, 118, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Wang, Y.; He, J.; Cai, C.; Liu, Q.; Yang, D.; Zou, Z.; Shi, L.; Jia, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Prevalence and Risk Analysis of Mobile Colistin Resistance and Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase Genes Carriage in Pet Dogs and Their Owners: A Population Based Cross-Sectional Study. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2021, 10, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Yin, W.; Schwarz, S.; Tyrrell, J.M.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, S.; Shen, Z.; et al. Comprehensive Resistome Analysis Reveals the Prevalence of NDM and MCR-1 in Chinese Poultry Production. Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 2, 16260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, L.; Wang, Y.; Schwarz, S.; Walsh, T.R.; Ou, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, M.; Shen, Z. Mcr-1 in Enterobacteriaceae from Companion Animals, Beijing, China, 2012–2016. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017, 23, 710–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Huang, X.-Y.; Xia, Y.-B.; Guo, Z.-W.; Ma, Z.-B.; Yi, M.-Y.; Lv, L.-C.; Lu, P.-L.; Yan, J.-C.; Huang, J.-W.; et al. Clonal Spread of Escherichia coli ST93 Carrying Mcr-1-Harboring IncN1-IncHI2/ST3 Plasmid Among Companion Animals, China. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmiedel, J.; Falgenhauer, L.; Domann, E.; Bauerfeind, R.; Prenger-Berninghoff, E.; Imirzalioglu, C.; Chakraborty, T. Multiresistant Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae from Humans, Companion Animals and Horses in Central Hesse, Germany. BMC Microbiol. 2014, 14, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Bai, X.; Ma, J.; Dang, R.; Xiong, Y.; Fanning, S.; Bai, L.; Yang, Z. Characterization of Five Escherichia coli Isolates Co-Expressing ESBL and MCR-1 Resistance Mechanisms from Different Origins in China. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Feng, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, H.; Yu, Y.; Liu, J.; Qiu, L.; Liu, H.; Guo, Z.; et al. Co-Occurrence of the Mcr-1.1 and Mcr-3.7 Genes in a Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli Isolate from China. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 3649–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, H.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, H.; Liu, J.; Qiu, L.; Guo, Z.; Huang, J.; Qiu, J.; et al. Colistin-Resistance Mcr Genes in Klebsiella pneumoniae from Companion Animals. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 25, 35–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, D.C.; Mechesso, A.F.; Kang, H.Y.; Kim, S.-J.; Choi, J.-H.; Kim, M.H.; Song, H.-J.; Yoon, S.-S.; Lim, S.-K. First Report of an Escherichia coli Strain Carrying the Colistin Resistance Determinant Mcr-1 from a Dog in South Korea. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.-H.; Chen, G.-J.; Lo, D.-Y. Chromosomal Locations of Mcr-1 IN Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterobacter cloacae from Dogs. Taiwan Vet. J. 2019, 45, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamame, A.; Davoust, B.; Rolain, J.-M.; Diene, S.M. Screening of Colistin-Resistant Bacteria in Domestic Pets from France. Animals 2022, 12, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guenther, S.; Falgenhauer, L.; Semmler, T.; Imirzalioglu, C.; Chakraborty, T.; Roesler, U.; Roschanski, N. Environmental Emission of Multiresistant Escherichia coli Carrying the Colistin Resistance Gene Mcr-1 from German Swine Farms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 1289–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumi, M.V.; Mas, J.; Elena, A.; Cerdeira, L.; Muñoz, M.E.; Lincopan, N.; Gentilini, É.R.; Di Conza, J.; Gutkind, G. Co-Occurrence of Clinically Relevant β-Lactamases and MCR-1 Encoding Genes in Escherichia coli from Companion Animals in Argentina. Vet. Microbiol. 2019, 230, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobs, V.C.; Valdez, R.E.; de Medeiros, F.; Fernandes, P.P.; Deglmann, R.C.; Gern, R.M.M.; França, P.H.C. Mcr-1-Carrying Enterobacteriaceae Isolated from Companion Animals in Brazil. Pesqui. Veterinária Bras. 2020, 40, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa Ito de Sousa, A.T.; dos Santos Costa, M.T.; Makino, H.; Cândido, S.L.; de Godoy Menezes, I.; Lincopan, N.; Nakazato, L.; Dutra, V. Multidrug-Resistant Mcr-1 Gene-Positive Klebsiella pneumoniae ST307 Causing Urinary Tract Infection in a Cat. Brazilian J. Microbiol. 2021, 52, 1043–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loayza-Villa, F.; Salinas, L.; Tijet, N.; Villavicencio, F.; Tamayo, R.; Salas, S.; Rivera, R.; Villacis, J.; Satan, C.; Ushiña, L.; et al. Diverse Escherichia coli Lineages from Domestic Animals Carrying Colistin Resistance Gene Mcr-1 in an Ecuadorian Household. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 22, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Paredes, D.; Haro, M.; Leoro-Garzón, P.; Barba, P.; Loaiza, K.; Mora, F.; Fors, M.; Vinueza-Burgos, C.; Fernández-Moreira, E. Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli Isolated from Canine Faeces in a Public Park in Quito, Ecuador. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2019, 18, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nittayasut, N.; Yindee, J.; Boonkham, P.; Yata, T.; Suanpairintr, N.; Chanchaithong, P. Multiple and High-Risk Clones of Extended-Spectrum Cephalosporin-Resistant and BlaNDM-5-Harbouring Uropathogenic Escherichia coli from Cats and Dogs in Thailand. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lei, L.; Zhang, H.; Dai, H.; Song, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Xia, Z. Molecular Investigation of Klebsiella pneumoniae from Clinical Companion Animals in Beijing, China, 2017–2019. Pathogens 2021, 10, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, H.O.; Oreiby, A.F.; Abd El-Hafeez, A.A.; Okanda, T.; Haque, A.; Anwar, K.S.; Tanaka, M.; Miyako, K.; Tsuji, S.; Kato, Y.; et al. First Report of Multidrug-Resistant Carbapenemase-Producing Bacteria Coharboring Mcr-9 Associated with Respiratory Disease Complex in Pets: Potential of Animal-Human Transmission. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 65, e01890-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Usui, M.; Harada, K.; Fukushima, Y.; Nakajima, C.; Suzuki, Y.; Yokota, S. Complete Genome Sequence of an Mcr-9 -Possessing Enterobacter asburiae Strain Isolated from a Cat in Japan. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2021, 10, e00281-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leelapsawas, C.; Sroithongkham, P.; Payungporn, S.; Nimsamer, P.; Yindee, J.; Collaud, A.; Perreten, V.; Chanchaithong, P. First Report of BlaOXA-181-Carrying IncX3 Plasmids in Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacter hormaechei and Serratia nevei Recovered from Canine and Feline Opportunistic Infections. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0358923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, D.A.; Pongchaikul, P.; Smith, S.; Bengtsson, R.J.; Baker, K.; Timofte, D.; Steen, S.; Jones, M.; Roberts, L.; Sánchez-Vizcaíno, F.; et al. Temporal, Spatial, and Genomic Analyses of Enterobacteriaceae Clinical Antimicrobial Resistance in Companion Animals Reveals Phenotypes and Genotypes of One Health Concern. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 700698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Usui, M.; Harada, K.; Fukushima, Y.; Nakajima, C.; Suzuki, Y.; Yokota, S. Complete Genome Sequence of an Mcr-10-Possessing Enterobacter roggenkampii Strain Isolated from a Dog in Japan. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2021, 10, e00426-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landman, D.; Salamera, J.; Quale, J. Irreproducible and Uninterpretable Polymyxin B MICs for Enterobacter cloacae and Enterobacter aerogenes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 4106–4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hindler, J.A.; Humphries, R.M. Colistin MIC Variability by Method for Contemporary Clinical Isolates of Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacilli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 1678–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in Europe—Annual Report of the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net) 2017; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Girardello, R.; Bispo, P.J.M.; Yamanaka, T.M.; Gales, A.C. Cation Concentration Variability of Four Distinct Mueller-Hinton Agar Brands Influences Polymyxin B Susceptibility Results. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 2414–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 30th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2020; ISBN 9781684400324. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI. Methods for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Anaerobic Bacteria; Approved Standard—Eighth Edition; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Matzneller, P.; Strommer, S.; Österreicher, Z.; Mitteregger, D.; Zeitlinger, M. Target Site Antimicrobial Activity of Colistin Might Be Misestimated If Tested in Conventional Growth Media. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2015, 34, 1989–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Rayner, C.R.; Nation, R.L.; Owen, R.J.; Spelman, D.; Tan, K.E.; Liolios, L. Heteroresistance to Colistin in Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 2946–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Band, V.I.; Crispell, E.K.; Napier, B.A.; Herrera, C.M.; Tharp, G.K.; Vavikolanu, K.; Pohl, J.; Read, T.D.; Bosinger, S.E.; Trent, M.S.; et al. Antibiotic Failure Mediated by a Resistant Subpopulation in Enterobacter cloacae. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 16053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, H.S.; Kim, S.Y.; Wi, Y.M.; Peck, K.R.; Ko, K.S. Colistin Heteroresistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates and Diverse Mutations of PmrAB and PhoPQ in Resistant Subpopulations. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Recommendations for MIC Determination of Colistin (Polymyxin E) as Recommended by the Joint CLSI-EUCAST Polymyxin Breakpoints Working Group. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/General_documents/Recommendations_for_MIC_determination_of_colistin_March_2016.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Laboratory Manual for Carbapenem and Colistin Resistance Detection and Characterisation for the Survey of Carbapenem- and/or Colistin-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae—Version 2.0; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC): Solna, Sweden, 2019.

- Poirel, L.; Jayol, A.; Nordmanna, P. Polymyxins: Antibacterial Activity, Susceptibility Testing, and Resistance Mechanisms Encoded by Plasmids or Chromosomes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 30, 557–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doijad, S.P.; Gisch, N.; Frantz, R.; Kumbhar, B.V.; Falgenhauer, J.; Imirzalioglu, C.; Falgenhauer, L.; Mischnik, A.; Rupp, J.; Behnke, M.; et al. Resolving Colistin Resistance and Heteroresistance in Enterobacter Species. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schurek, K.N.; Sampaio, J.L.M.; Kiffer, C.R.V.; Sinto, S.; Mendes, C.M.F.; Hancock, R.E.W. Involvement of PmrAB and PhoPQ in Polymyxin B Adaptation and Inducible Resistance in Non-Cystic Fibrosis Clinical Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 4345–4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasoo, S. Susceptibility Testing for the Polymyxins: Two Steps Back, Three Steps Forward? J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 2573–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turlej-Rogacka, A.; Xavier, B.B.; Janssens, L.; Lammens, C.; Zarkotou, O.; Pournaras, S.; Goossens, H.; Malhotra-Kumar, S. Evaluation of Colistin Stability in Agar and Comparison of Four Methods for MIC Testing of Colistin. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 37, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skov, R.; Skov, G. EUCAST Guidelines for Detection of Resistance Mechanisms and Specific Resistances of Clinical and/or Epidemiological Importance. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/resistance_mechanisms/ (accessed on 9 January 2022).

- Jorgensen, J.H.; Ferraro, M.J. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: A Review of General Principles and Contemporary Practices. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 49, 1749–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Shin, J.H.; Lee, K.; Joo, M.Y.; Park, K.H.; Shin, M.G.; Suh, S.P.; Ryang, D.W.; Kim, S.H. Comparison of the Vitek 2, MicroScan, and Etest Methods with the Agar Dilution Method in Assessing Colistin Susceptibility of Bloodstream Isolates of Acinetobacter Species from a Korean University Hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 1924–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayol, A.; Nordmann, P.; André, C.; Poirel, L.; Dubois, V. Evaluation of Three Broth Microdilution Systems to Determine Colistin Susceptibility of Gram-Negative Bacilli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 1272–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, E.; van Westreenen, M.; Goessens, W.; Croughs, P. The Accuracy of Four Commercial Broth Microdilution Tests in the Determination of the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Colistin. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2020, 19, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardet, L.; Okdah, L.; Le Page, S.; Baron, S.A.; Rolain, J.-M. Comparative Evaluation of the UMIC Colistine Kit to Assess MIC of Colistin of Gram-Negative Rods. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo-Ten-Foe, J.R.; de Smet, A.M.G.A.; Diederen, B.M.W.; Kluytmans, J.A.J.W.; van Keulen, P.H.J. Comparative Evaluation of the VITEK 2, Disk Diffusion, Etest, Broth Microdilution, and Agar Dilution Susceptibility Testing Methods for Colistin in Clinical Isolates, Including Heteroresistant Enterobacter cloacae and Acinetobacter baumannii Strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 3726–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.Y.; Ng, S.Y. Comparison of Etest, Vitek and Agar Dilution for Susceptibility Testing of Colistin. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2007, 13, 541–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebelo, A.R.; Bortolaia, V.; Kjeldgaard, J.S.; Pedersen, S.K.; Leekitcharoenphon, P.; Hansen, I.M.; Guerra, B.; Malorny, B.; Borowiak, M.; Hammerl, J.A.; et al. Multiplex PCR for Detection of Plasmid-Mediated Colistin Resistance Determinants, Mcr-1, Mcr-2, Mcr-3, Mcr-4 and Mcr-5 for Surveillance Purposes. Euro Surveill. 2018, 23, 17-00672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borowiak, M.; Baumann, B.; Fischer, J.; Thomas, K.; Deneke, C.; Hammerl, J.A.; Szabo, I.; Malorny, B. Development of a Novel Mcr-6 to Mcr-9 Multiplex PCR and Assessment of Mcr-1 to Mcr-9 Occurrence in Colistin-Resistant Salmonella enterica Isolates from Environment, Feed, Animals and Food (2011–2018) in Germany. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ma, S.; Zhao, C.; Yan, S.; Zhu, L. Tenfold Multiplex PCR Method for Simultaneous Detection of Mcr-1 to Mcr-10 Genes and Application for Retrospective Investigations of Salmonella and Escherichia coli Isolates in China. Microb. Pathog. 2025, 203, 107478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bontron, S.; Poirel, L.; Nordmann, P. Real-Time PCR for Detection of Plasmid-Mediated Polymyxin Resistance (Mcr-1) from Cultured Bacteria and Stools. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 2318–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabou, S.; Leangapichart, T.; Okdah, L.; Le Page, S.; Hadjadj, L.; Rolain, J.-M. Real-Time Quantitative PCR Assay with Taqman® Probe for Rapid Detection of MCR-1 Plasmid-Mediated Colistin Resistance. New Microbes New Infect. 2016, 13, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Yang, G.; Liu, W.; Wu, D.; Duan, C.; Jia, X.; Li, Z.; Zou, X.; Yu, R.; Zou, D.; et al. A Multiplex TaqMan Real-Time PCR Assays for the Rapid Detection of Mobile Colistin Resistance (Mcr-1 to Mcr-10) Genes. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1279186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schürch, A.C.; Arredondo-Alonso, S.; Willems, R.J.L.; Goering, R.V. Whole Genome Sequencing Options for Bacterial Strain Typing and Epidemiologic Analysis Based on Single Nucleotide Polymorphism versus Gene-by-Gene–Based Approaches. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018, 24, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imirzalioglu, C.; Falgenhauer, L.; Schmiedel, J.; Waezsada, S.-E.; Gwozdzinski, K.; Roschanski, N.; Roesler, U.; Kreienbrock, L.; Schiffmann, A.P.; Irrgang, A.; et al. Evaluation of a Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification-Based Assay for the Rapid Detection of Plasmid-Encoded Colistin Resistance Gene Mcr-1 in Enterobacteriaceae Isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e02326-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.-L.; Zhou, Q.; Tan, C.; Roberts, A.P.; El-Sayed Ahmed, M.A.E.-G.; Chen, G.; Dai, M.; Yang, F.; Xia, Y.; Liao, K.; et al. Multiplex Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (Multi-LAMP) Assay for Rapid Detection of Mcr-1 to Mcr-5 in Colistin-Resistant Bacteria. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 1877–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernasconi, O.J.; Principe, L.; Tinguely, R.; Karczmarek, A.; Perreten, V.; Luzzaro, F.; Endimiani, A. Evaluation of a New Commercial Microarray Platform for the Simultaneous Detection of β-Lactamase and Mcr-1 and Mcr-2 Genes in Enterobacteriaceae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 3138–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordmann, P.; Jayol, A.; Poirel, L. Rapid Detection of Polymyxin Resistance in Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 1038–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volland, H.; Dortet, L.; Bernabeu, S.; Boutal, H.; Haenni, M.; Madec, J.-Y.; Robin, F.; Beyrouthy, R.; Naas, T.; Simon, S. Development and Multicentric Validation of a Lateral Flow Immunoassay for Rapid Detection of MCR-1-Producing Enterobacteriaceae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019, 57, e01454-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo, M.; Santiso, R.; Otero, F.; Bou, G.; Lepe, J.A.; McConnell, M.J.; Cisneros, J.M.; Gosálvez, J.; Fernández, J.L. Rapid Determination of Colistin Resistance in Clinical Strains of Acinetobacter baumannii by Use of the Micromax Assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 3675–3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Expert Consensus Protocol on Colistin Resistance Detection and Characterisation for the Survey of Carbapenem- and/or Colistin-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae—Version 3.0; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC): Solna, Sweden, 2019.

- European Commission. Commission Implementing Decision 2013/652/EU of 12 November 2013 on the Monitoring and Reporting of Antimicrobial Resistance in Zoonotic and Commensal Bacteria. Off. J. Eur. Union 2013. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dec_impl/2013/652/oj/eng (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Mader, R.; Damborg, P.; Amat, J.P.; Bengtsson, B.; Bourély, C.; Broens, E.M.; Busani, L.; Crespo-Robledo, P.; Filippitzi, M.E.; Fitzgerald, W.; et al. Building the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network in Veterinary Medicine (EARS-Vet). Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2001359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedres-Svarm. Sales of Antibiotics and Occurrence of Resistance in Sweden; Public Health Agency of Sweden: Solna, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Anses. Résapath—Réseau D’épidémiosurveillance de L’antibiorésistance des Bactéries Pathogènes Animales, Bilan 2022; Anses: Lyon, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; Ma, S.; Chen, S.; Schwarz, S.; Cao, Y.; Dang, X.; Zhai, W.; Zou, Z.; Shen, J.; Lyu, Y.; et al. Low Prevalence of Colistin-Resistant Escherichia coli from Companion Animals, China, 2018–2021. One Health Adv. 2023, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halaby, T.; al Naiemi, N.; Kluytmans, J.; van der Palen, J.; Vandenbroucke-Grauls, C.M.J.E. Emergence of Colistin Resistance in Enterobacteriaceae after the Introduction of Selective Digestive Tract Decontamination in an Intensive Care Unit. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 3224–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.-P.; Lin, Q.-Q.; He, W.-Y.; Wang, J.; Yi, M.-Y.; Lv, L.-C.; Yang, J.; Liu, J.-H.; Guo, J.-Y. Co-Selection May Explain the Unexpectedly High Prevalence of Plasmid-Mediated Colistin Resistance Gene Mcr-1 in a Chinese Broiler Farm. Zool. Res. 2020, 41, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zurfluh, K.; Tasara, T.; Poirel, L.; Nordmann, P.; Stephan, R. Draft Genome Sequence of Escherichia coli S51, a Chicken Isolate Harboring a Chromosomally Encoded Mcr-1 Gene. Genome Announc. 2016, 4, e00796-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FEDIAF. European Pet Food Data: An Updated and Robust Approach; FEDIAF: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- McNicholas, J.; Gilbey, A.; Rennie, A.; Ahmedzai, S.; Dono, J.-A.; Ormerod, E. Pet Ownership and Human Health: A Brief Review of Evidence and Issues. BMJ 2005, 331, 1252–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijs, A.P.; Gijsbers, E.F.; Hengeveld, P.D.; Dierikx, C.M.; de Greeff, S.C.; van Duijkeren, E. ESBL/PAmpC-Producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae Carriage among Veterinary Healthcare Workers in the Netherlands. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2021, 10, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endimiani, A.; Brilhante, M.; Bernasconi, O.J.; Perreten, V.; Schmidt, J.S.; Dazio, V.; Nigg, A.; Gobeli Brawand, S.; Kuster, S.P.; Schuller, S.; et al. Employees of Swiss Veterinary Clinics Colonized with Epidemic Clones of Carbapenemase-Producing Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 766–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damborg, P.; Broens, E.M.; Chomel, B.B.; Guenther, S.; Pasmans, F.; Wagenaar, J.A.; Weese, J.S.; Wieler, L.H.; Windahl, U.; Vanrompay, D.; et al. Bacterial Zoonoses Transmitted by Household Pets: State-of-the-Art and Future Perspectives for Targeted Research and Policy Actions. J. Comp. Pathol. 2016, 155, S27–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dazio, V.; Nigg, A.; Schmidt, J.S.; Brilhante, M.; Campos-Madueno, E.I.; Mauri, N.; Kuster, S.P.; Brawand, S.G.; Willi, B.; Endimiani, A.; et al. Duration of Carriage of Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria in Dogs and Cats in Veterinary Care and Co-Carriage with Their Owners. One Health 2021, 13, 100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Osman, M.; Green, B.A.; Yang, Y.; Ahuja, A.; Lu, Z.; Cazer, C.L. Evidence for the Transmission of Antimicrobial Resistant Bacteria between Humans and Companion Animals: A Scoping Review. One Health 2023, 17, 100593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westgarth, C.; Pinchbeck, G.L.; Bradshaw, J.W.S.; Dawson, S.; Gaskell, R.M.; Christley, R.M. Dog-human and Dog-dog Interactions of 260 Dog-owning Households in a Community in Cheshire. Vet. Rec. 2008, 162, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walther, B.; Hermes, J.; Cuny, C.; Wieler, L.H.; Vincze, S.; Abou Elnaga, Y.; Stamm, I.; Kopp, P.A.; Kohn, B.; Witte, W.; et al. Sharing More than Friendship—Nasal Colonization with Coagulase-Positive Staphylococci (CPS) and Co-Habitation Aspects of Dogs and Their Owners. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joosten, P.; Van Cleven, A.; Sarrazin, S.; Paepe, D.; De Sutter, A.; Dewulf, J. Dogs and Their Owners Have Frequent and Intensive Contact. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada, A.; Ugarte-Ruiz, M.; Iglesias, M.R.; Porrero, M.C.; Martínez, R.; Florez-Cuadrado, D.; Campos, M.J.; García, M.; Píriz, S.; Sáez, J.L.; et al. Detection of Plasmid Mediated Colistin Resistance (MCR-1) in Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica Isolated from Poultry and Swine in Spain. Res. Vet. Sci. 2016, 105, 134–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomba, C.; Rantala, M.; Greko, C.; Baptiste, K.E.; Catry, B.; van Duijkeren, E.; Mateus, A.; Moreno, M.A.; Pyörälä, S.; Ružauskas, M.; et al. Public Health Risk of Antimicrobial Resistance Transfer from Companion Animals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokracka, J.; Koczura, R.; Kaznowski, A. Multiresistant Enterobacteriaceae with Class 1 and Class 2 Integrons in a Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant. Water Res. 2012, 46, 3353–3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoesser, N.; Mathers, A.J.; Moore, C.E.; Day, N.P.; Crook, D.W. Colistin Resistance Gene Mcr-1 and PHNSHP45 Plasmid in Human Isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 285–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zhu, B.; Liang, B.; Xu, X.; Qiu, S.; Jia, L.; Li, P.; Yang, L.; Li, Y.; Xiang, Y.; et al. A Novel Mcr-1 Variant Carried by an IncI2-Type Plasmid Identified from a Multidrug Resistant Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurfluh, K.; Klumpp, J.; Nüesch-Inderbinen, M.; Stephan, R. Full-Length Nucleotide Sequences of Mcr-1-Harboring Plasmids Isolated from Extended-Spectrum-β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli Isolates of Different Origins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 5589–5591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, A.; Smith, M.; Smith, F.; Park, J.; King, C.; Currie, K.; Langdridge, D.; Davis, M.; Flowers, P. Understanding the Relationship between Pet Owners and Their Companion Animals as a Key Context for Antimicrobial Resistance-Related Behaviours: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2019, 7, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tompson, A.C.; Mateus, A.L.P.; Brodbelt, D.C.; Chandler, C.I.R. Understanding Antibiotic Use in Companion Animals: A Literature Review Identifying Avenues for Future Efforts. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 719547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, D.H.; Page, S.W. Antimicrobial Stewardship in Veterinary Medicine. Microbiol. Spectr. 2018, 6, 675–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willemsen, A.; Cobbold, R.; Gibson, J.; Wilks, K.; Lawler, S.; Reid, S. Infection Control Practices Employed within Small Animal Veterinary Practices—A Systematic Review. Zoonoses Public Health 2019, 66, 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hembach, N.; Schmid, F.; Alexander, J.; Hiller, C.; Rogall, E.T.; Schwartz, T. Occurrence of the Mcr-1 Colistin Resistance Gene and Other Clinically Relevant Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Microbial Populations at Different Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants in Germany. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsitch, M.; Siber, G.R. How Can Vaccines Contribute to Solving the Antimicrobial Resistance Problem? MBio 2016, 7, e00428-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Plasmid Type | Year | Country | Host | Bacterial Species | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mcr-1 | IncI2 | 2015 | China | Pig | Escherichia coli | [38] |

| mcr-2 | IncX4 | 2016 | Belgium | Calves and pigs | Escherichia coli | [47] |

| mcr-3 | IncHI2 | 2017 | China | Pig | Escherichia coli | [48] |

| mcr-4 | ColE | 2017 | Italy | Pig | Salmonella enterica | [49] |

| mcr-5 | ColE | 2017 | Germany | Poultry | Salmonella Paratyphi B | [50] |

| mcr-6 | IncX4 | 2017 | UK | Pig | Moraxella pluranimalium | [51] |

| mcr-7 | IncI2 | 2018 | China | Chicken | Klebsiella pneumoniae | [52] |

| mcr-8 | IncFII | 2018 | China | Pig | Klebsiella pneumoniae | [53] |

| mcr-9 | IncHI2 | 2019 | USA | Human | Salmonella enterica | [54] |

| mcr-10 | IncFIA | 2020 | China | Human | Enterobacter roggenkampii | [55] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Menezes, J.; Fernandes, L.; Marques, C.; Pomba, C. The Public Health Risks of Colistin Resistance in Dogs and Cats: A One Health Perspective Review. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1213. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121213

Menezes J, Fernandes L, Marques C, Pomba C. The Public Health Risks of Colistin Resistance in Dogs and Cats: A One Health Perspective Review. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1213. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121213

Chicago/Turabian StyleMenezes, Juliana, Laura Fernandes, Cátia Marques, and Constança Pomba. 2025. "The Public Health Risks of Colistin Resistance in Dogs and Cats: A One Health Perspective Review" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1213. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121213

APA StyleMenezes, J., Fernandes, L., Marques, C., & Pomba, C. (2025). The Public Health Risks of Colistin Resistance in Dogs and Cats: A One Health Perspective Review. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1213. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121213