Design, Synthesis, and Antimalarial Evaluation of New Spiroacridine Derivatives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

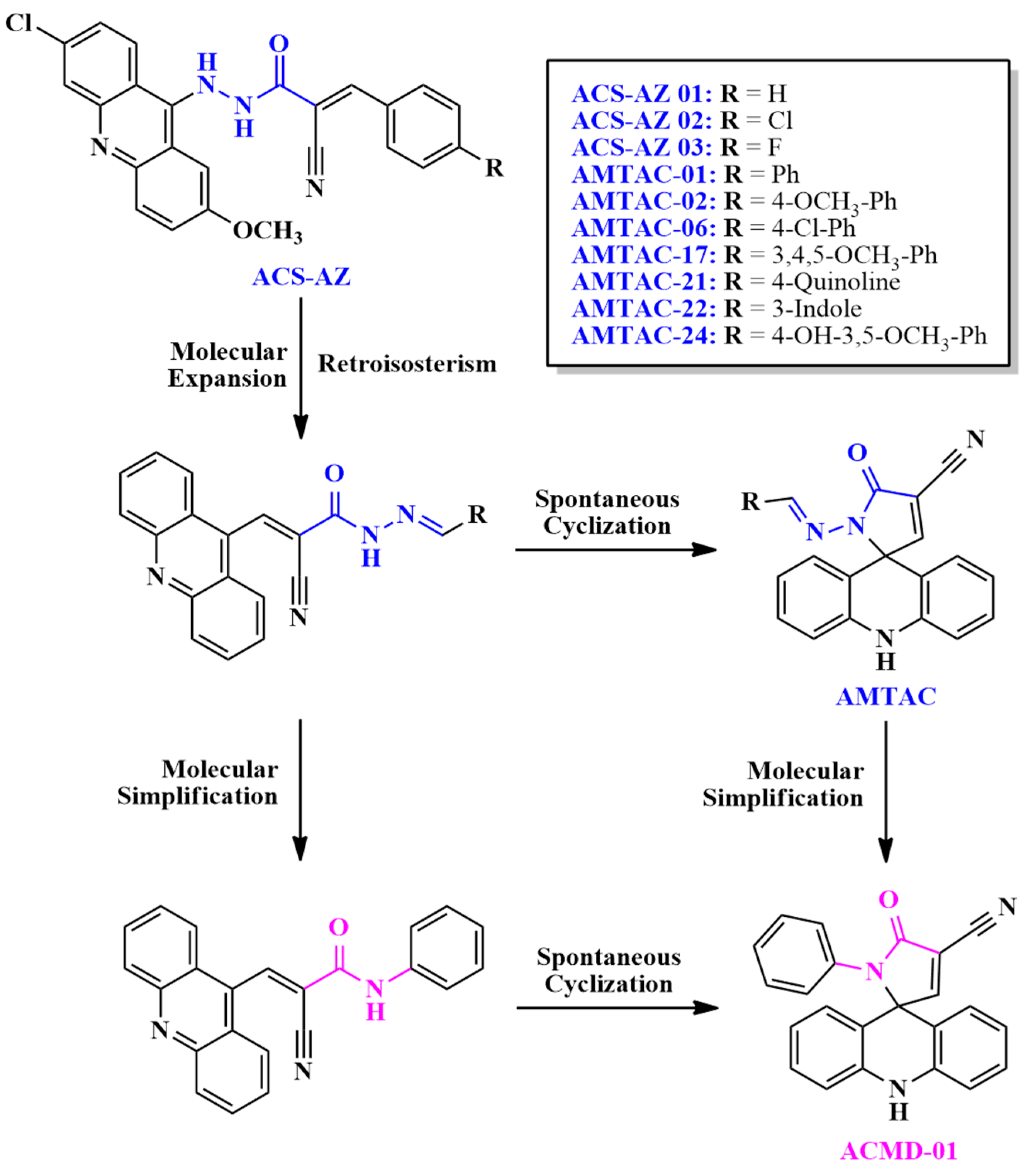

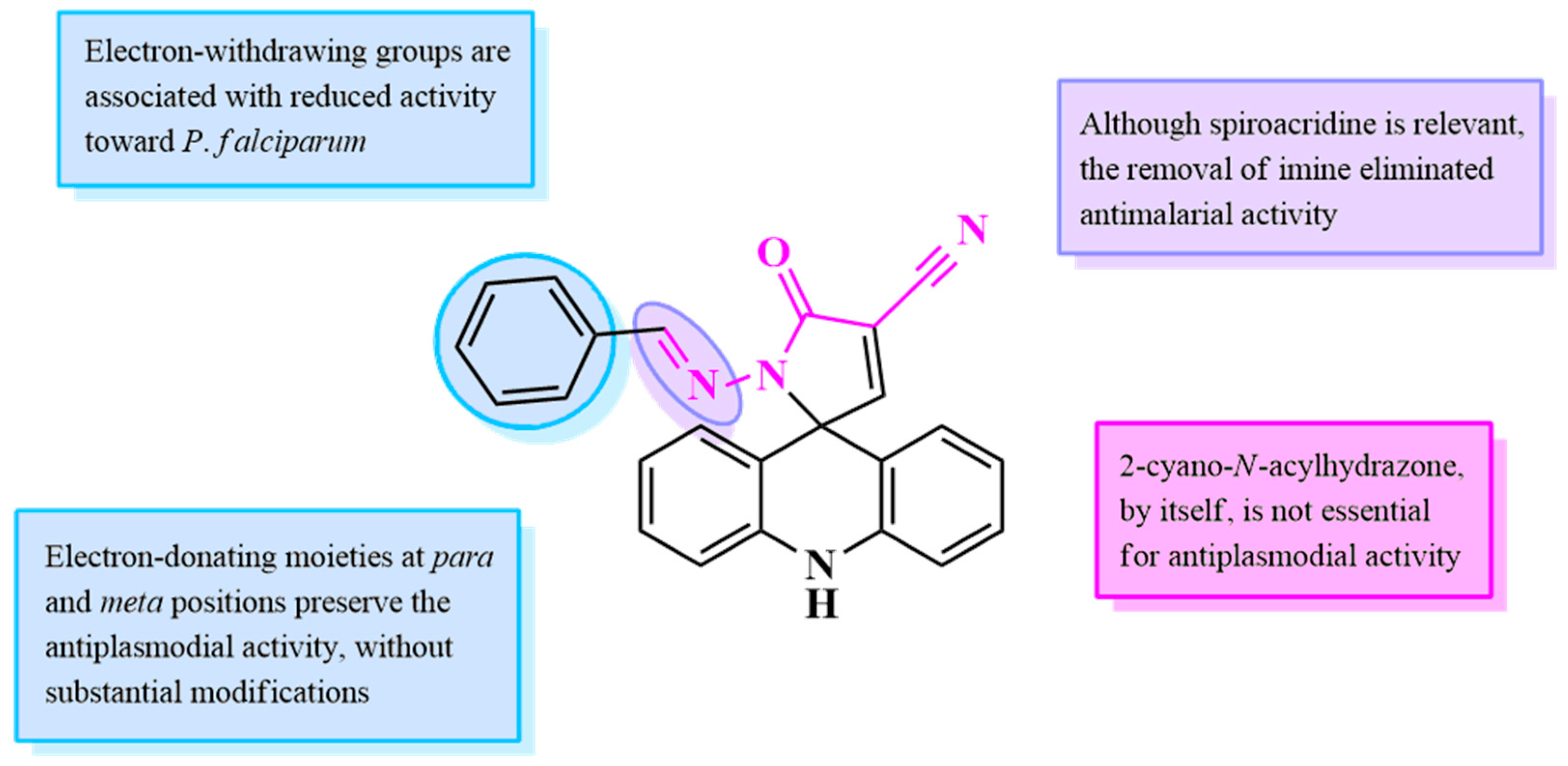

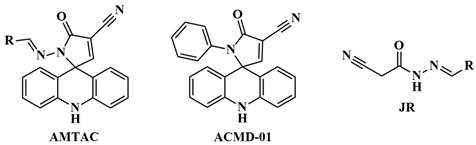

2.1. Design of Compounds

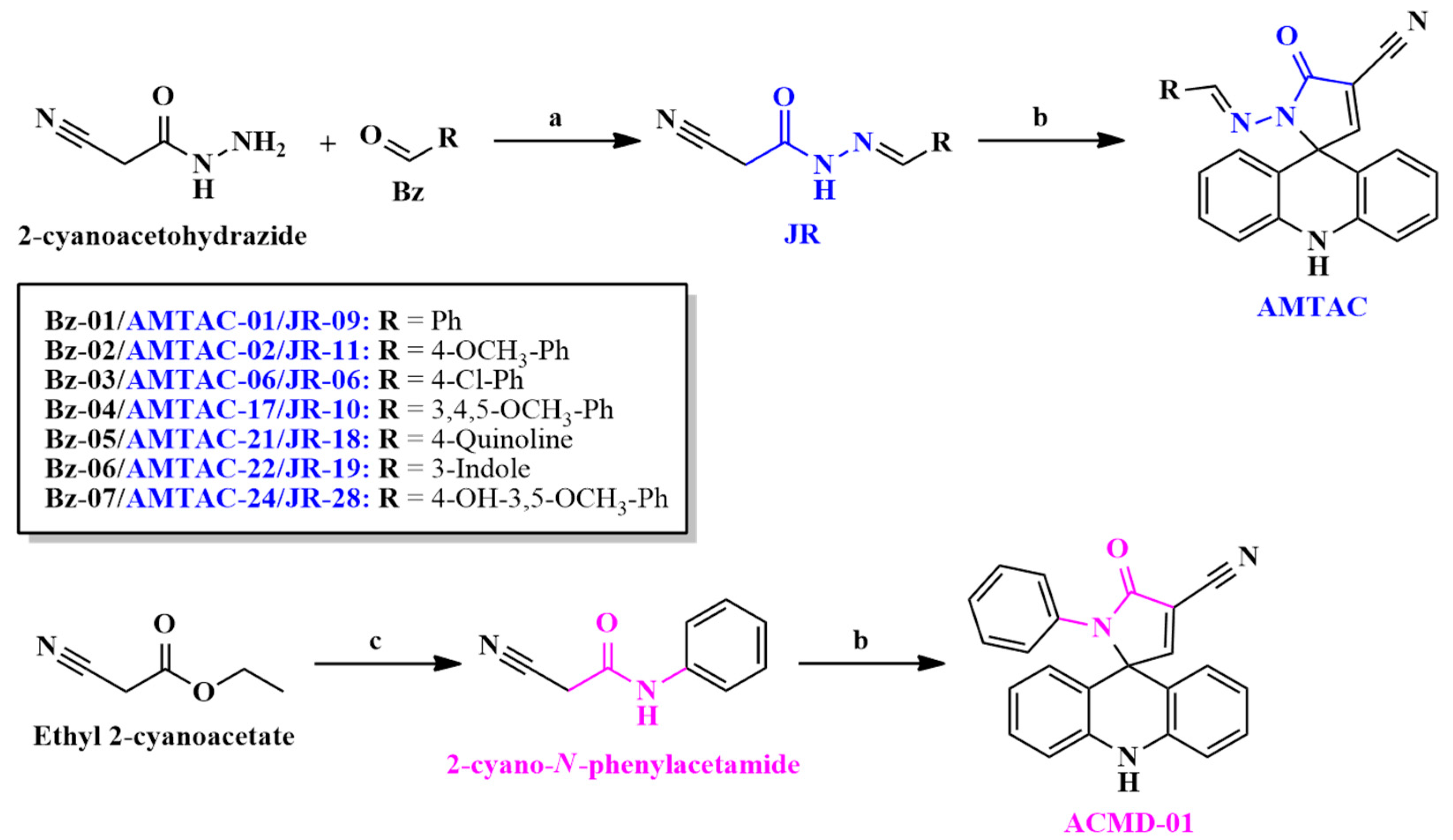

2.2. Synthesis and Structural Elucidation

2.3. Antimalarial Activity Against Asexual Blood Stages

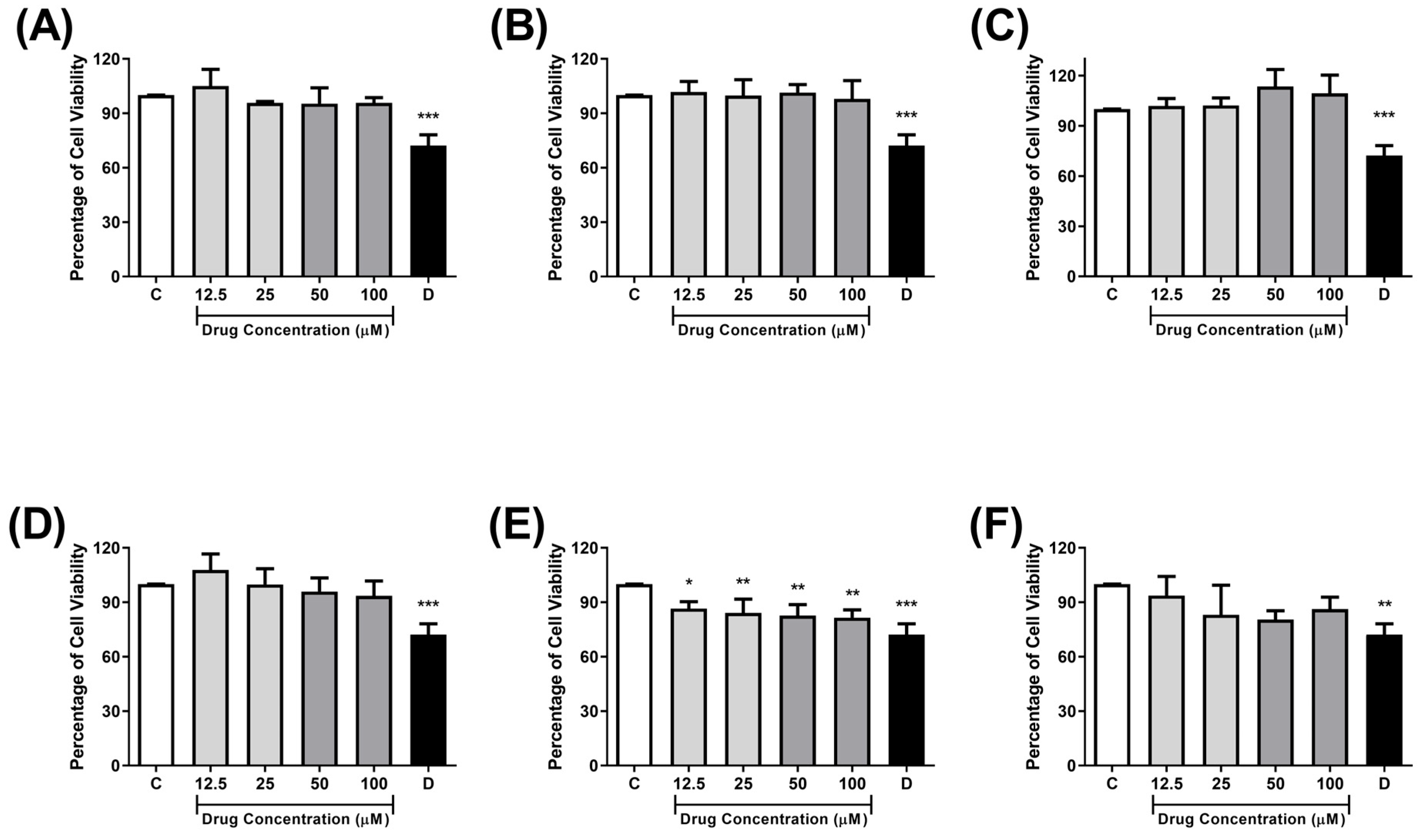

2.4. Cytotoxicity Against Monkey Kidney Cells (Vero E6)

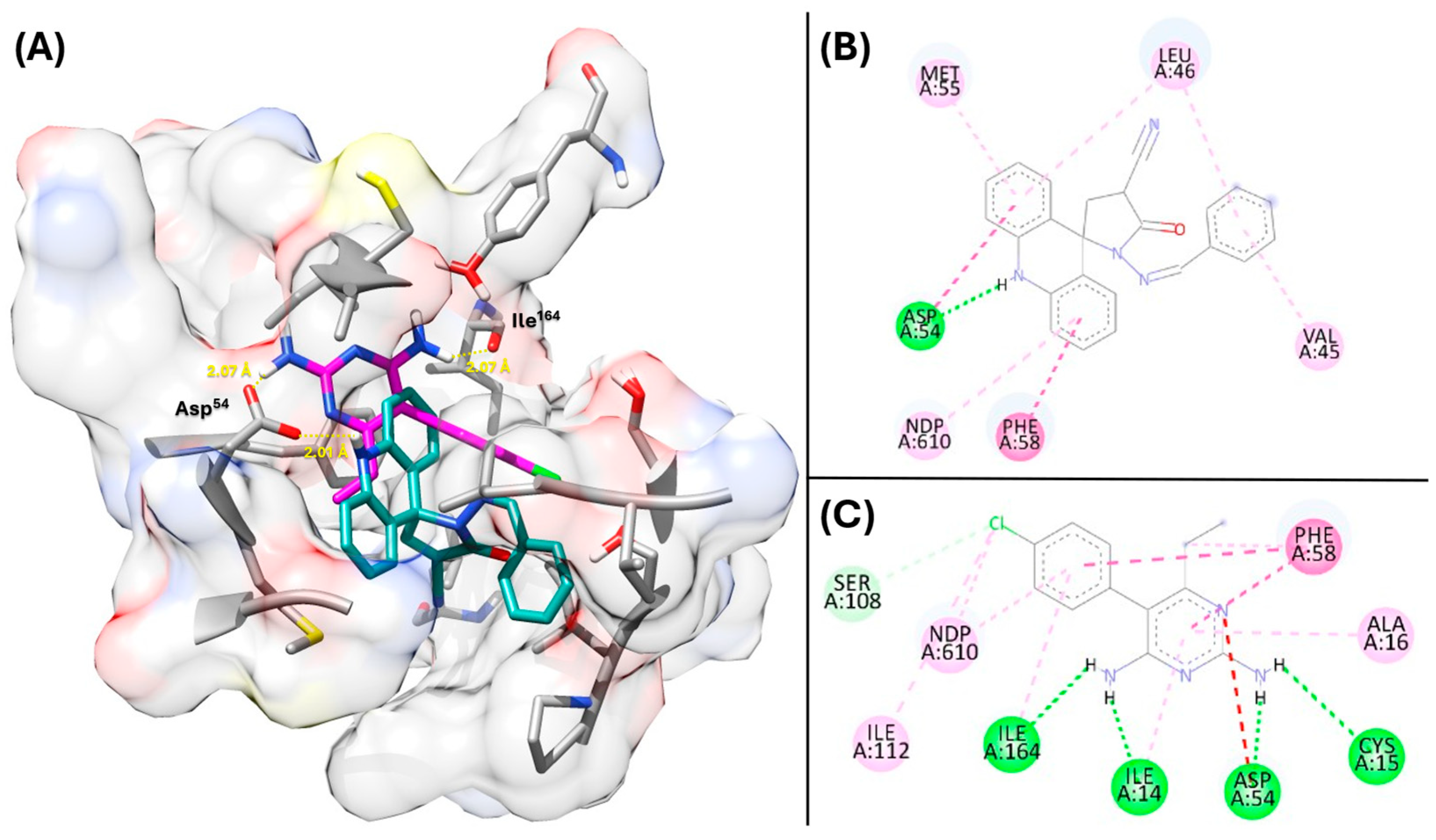

2.5. Proposing the Mechanism of Action Through Molecular Docking

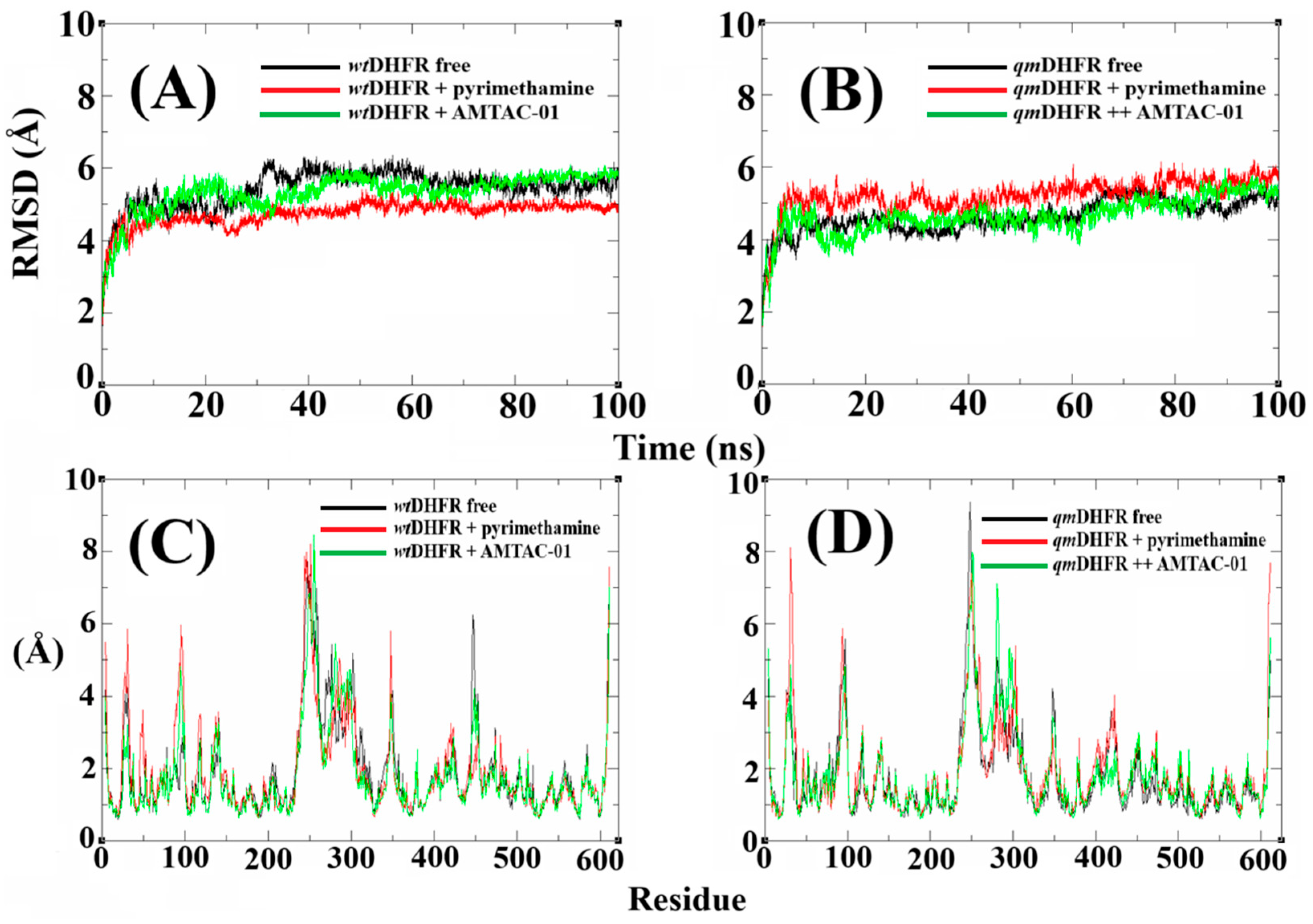

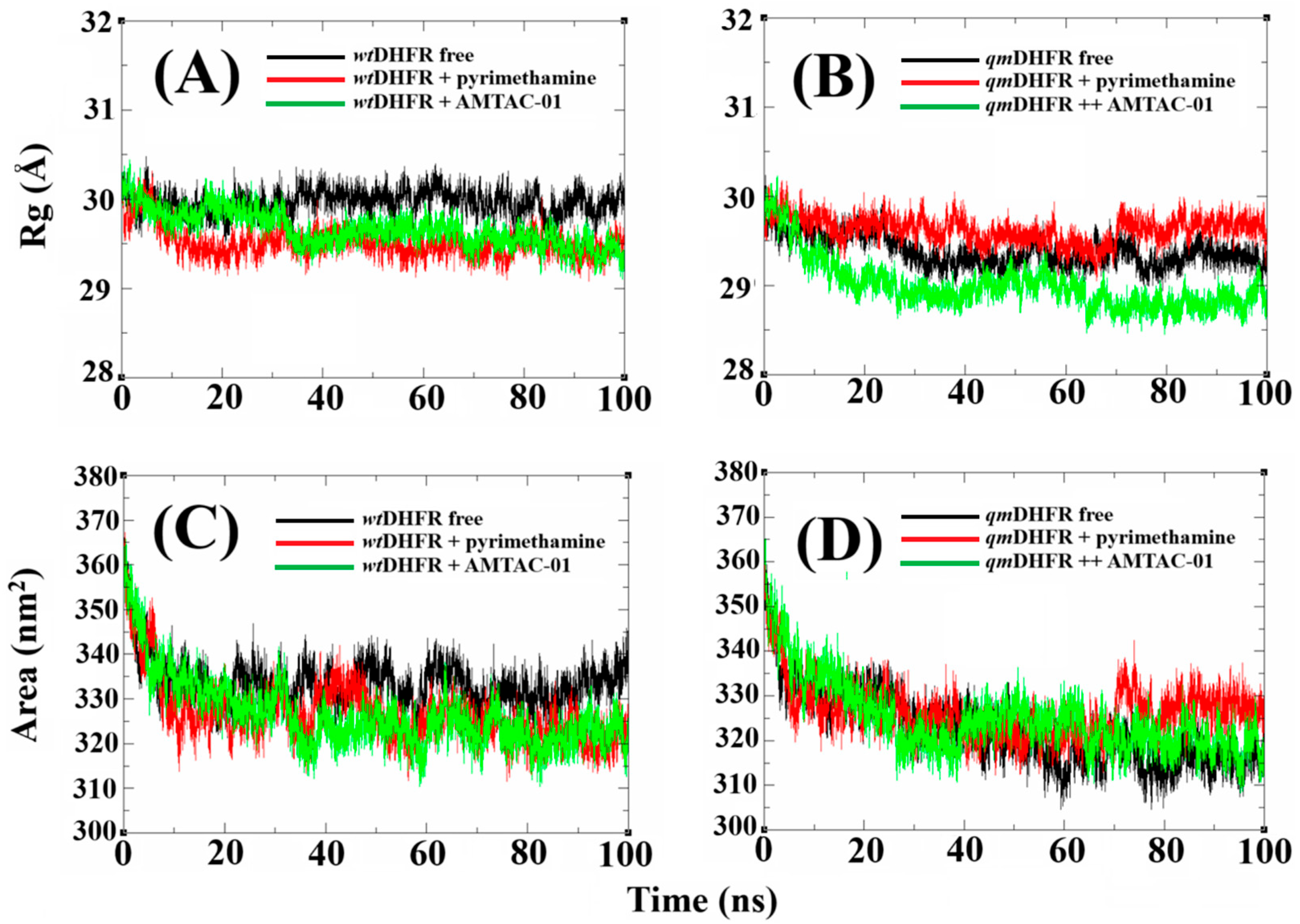

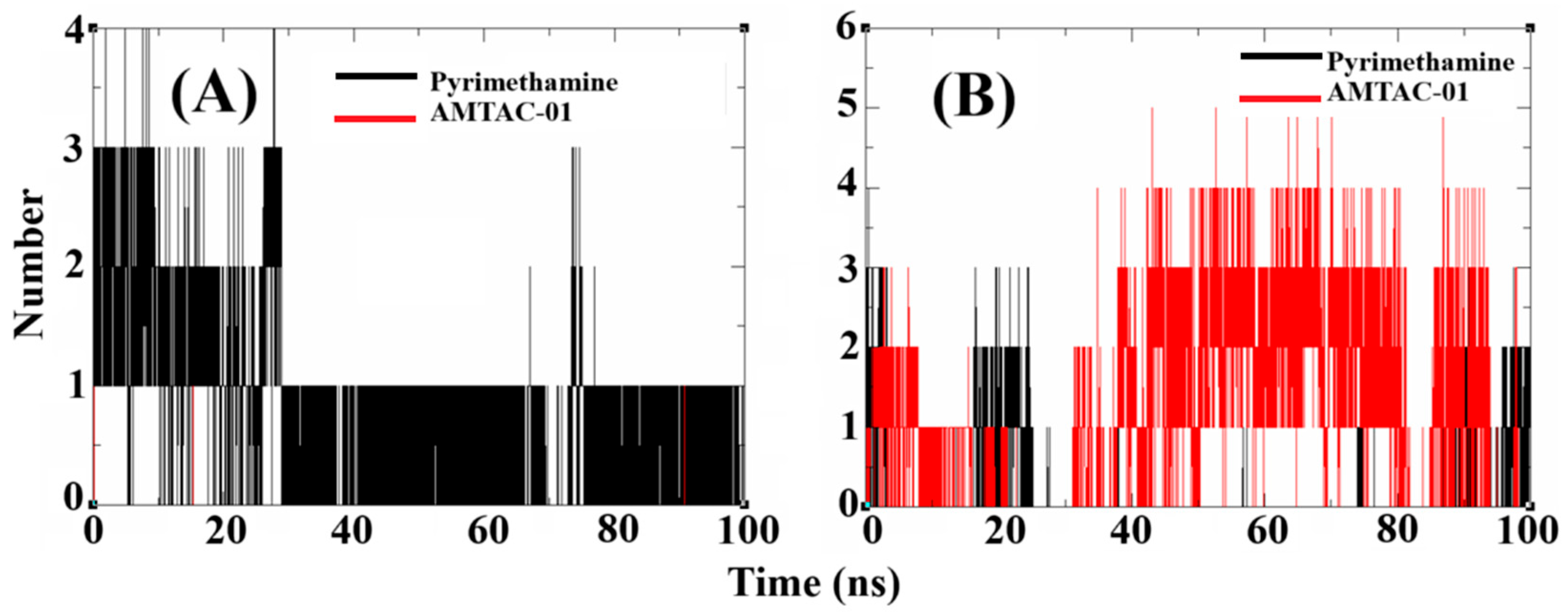

2.6. Molecular Dynamics (MDs) Simulations to Propose the Target and Insights to Overcome Resistance

2.7. Validation of DHFR Targeting Through MM-PBSA Calculations

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Synthesis and Structural Characterization

4.2. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Spiroacridines

4.3. Investigation of Antiplasmodial Activity Against Asexual Blood Stages

4.4. Evaluation of Cytotoxicity Against Mammalian Cells

4.5. Statistical Analysis

4.6. Molecular Docking

4.7. Homology Modeling

4.8. Molecular Dynamics (MDs) Simulations

4.9. MM-PBSA Calculations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 1H-NMR | 1-Hydrogen Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| 3D7-GFP | Plasmodium falciparum 3D7HT-GFP |

| 13C-NMR | 13-Carbon Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| ΔGbind | Gibbs Free Binding Energy |

| ATR | Attenuated Total Reflectance |

| CQ | Chloroquine |

| DHFR | Dihydrofolate Reductase |

| DHODH | Dihydroorotate Dehydrogenase |

| ENR | Enoyl Acyl Carrier Protein Reductase |

| FP2 | Falcipain-2 |

| FP3 | Falcipain-3 |

| GFP | Green Fluorescent Protein |

| GHIT | Japanese Global Health Innovative Technology |

| GOLD | Genetic Optimization for Ligand Docking |

| HRESIMS | High-Resolution Electrospray Ionization Mass |

| IC50 | Half-Maximal Inhibitory Concentration |

| LD50 | Median Lethal Dose |

| LDH | Lactate Dehydrogenase |

| MALDI-TOF | Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight |

| MD | Molecular Dynamics |

| MM-PBSA | Molecular Mechanics Poisson–Boltzmann Surface Area |

| PNPase | Purine Nucleoside Phosphorylase |

| ProRS | Prolyl-tRNA Synthetase |

| qmDHFR | Quadrupole-Mutated Dihydrofolate Reductase |

| Rg | Radius of Gyration |

| RI | Resistance Index |

| RMSD | Root Mean Square Deviation |

| RMSF | Root Mean Square Fluctuation |

| SAR | Structure–Activity Relationship |

| SASA | Solvent Accessible Surface Area |

| SI | Selectivity Index |

| TLC | Thin-Layer Chromatography |

| Topo II | Topoisomerase II |

| wtDHFR | Wild-Type Dihydrofolate Reductase |

References

- de Azevedo Teotônio Cavalcanti, M.; Da Silva Menezes, K.J.; De Oliveira Viana, J.; de Oliveira Rios, É.; Corrêa de Farias, A.G.; Weber, K.C.; Nogueira, F.; dos Santos Nascimento, I.J.; de Moura, R.O. Current Trends to Design Antimalarial Drugs Targeting N-Myristoyltransferase. Future Microbiol. 2024, 19, 1601–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, I.J.d.S.; Cavalcanti, M.d.A.T.; de Moura, R.O. Exploring N-Myristoyltransferase as a Promising Drug Target against Parasitic Neglected Tropical Diseases. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 258, 115550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salkeld, J.; Duncan, A.; Minassian, A.M. Malaria: Past, Present and Future. Clin. Med. 2024, 24, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2024; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Volume WHO/HTM/GM, ISBN 978-92-4-010444-0. [Google Scholar]

- Alven, S.; Aderibigbe, B. Combination Therapy Strategies for the Treatment of Malaria. Molecules 2019, 24, 3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gujjari, L.; Kalani, H.; Pindiprolu, S.K.; Arakareddy, B.P.; Yadagiri, G. Current Challenges and Nanotechnology-Based Pharmaceutical Strategies for the Treatment and Control of Malaria. Parasite Epidemiol. Control 2022, 17, e00244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanboonkunupakarn, B.; White, N.J. Advances and Roadblocks in the Treatment of Malaria. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 88, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindar, L.; Hasbullah, S.A.; Rakesh, K.P.; Hassan, N.I. Triazole Hybrid Compounds: A New Frontier in Malaria Treatment. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 259, 115694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonte, M.; Tassi, N.; Gomes, P.; Teixeira, C. Acridine-Based Antimalarials—From the Very First Synthetic Antimalarial to Recent Developments. Molecules 2021, 26, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albino, S.L.; da Silva, J.M.; de Caldas Nobre, M.S.; Silva, Y.M.S.d.M.E.; Santos, M.B.; de Araújo, R.S.A.; do Carmo Alves de Lima, M.; Schmitt, M.; de Moura, R.O. Bioprospecting of Nitrogenous Heterocyclic Scaffolds with Potential Action for Neglected Parasitosis: A Review. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020, 26, 4112–4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, C.; Vale, N.; Pérez, B.; Gomes, A.; Gomes, J.R.B.; Gomes, P. “Recycling” Classical Drugs for Malaria. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11164–11220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, S.M.V.; Lafayette, E.A.; Silva, W.L.; de Lima Serafim, V.; Menezes, T.M.; Neves, J.L.; Ruiz, A.L.T.G.; de Carvalho, J.E.; de Moura, R.O.; Beltrão, E.I.C.; et al. New Spiro-Acridines: DNA Interaction, Antiproliferative Activity and Inhibition of Human DNA Topoisomerases. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 92, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, T.M.; de Almeida, S.M.V.; de Moura, R.O.; Seabra, G.; de Lima, M.d.C.A.; Neves, J.L. Spiro-Acridine Inhibiting Tyrosinase Enzyme: Kinetic, Protein-Ligand Interaction and Molecular Docking Studies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 122, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, V.M.; Duarte, S.S.; Silva, D.K.F.; Ferreira, R.C.; de Moura, R.O.; Segundo, M.A.S.P.; Farias, D.; Vieira, L.; Gonçalves, J.C.R.; Sobral, M.V. Cytotoxicity of a New Spiro-Acridine Derivative: Modulation of Cellular Antioxidant State and Induction of Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in HCT-116 Colorectal Carcinoma. Naunyn-Schmiedeb. Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 1901–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, S.S.; Silva, D.K.F.; Lisboa, T.M.H.; Gouveia, R.G.; Ferreira, R.C.; de Moura, R.O.; da Silva, J.M.; de Almeida Lima, É.; Rodrigues-Mascarenhas, S.; da Silva, P.M.; et al. Anticancer Effect of a Spiro-Acridine Compound Involves Immunomodulatory and Anti-Angiogenic Actions. Anticancer Res. 2020, 40, 5049–5057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.K.F.; Duarte, S.S.; Lisboa, T.M.H.; Ferreira, R.C.; Lopes, A.L.d.O.; Carvalho, D.C.M.; Rodrigues-Mascarenhas, S.; da Silva, P.M.; Segundo, M.A.S.P.; de Moura, R.O.; et al. Antitumor Effect of a Novel Spiro-Acridine Compound Is Associated with Up-Regulation of Th1-Type Responses and Antiangiogenic Action. Molecules 2019, 25, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, C.d.O.; Silva, V.R.; Santos, L.d.S.; Urtiga, S.C.; de Moura, R.O.; Marcelino, H.R.; Soares, M.B.P.; Bezerra, D.P.; Oliveira, E.E. Spiro-Acridine Derivative-Loaded PLA Nanoparticles for Colorectal Cancer Treatment. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 101, 106244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, V.M.; Duarte, S.S.; Ferreira, R.C.; de Sousa, N.F.; Scotti, M.T.; Scotti, L.; da Silva, M.S.; Tavares, J.F.; de Moura, R.O.; Gonçalves, J.C.R.; et al. AMTAC-19, a Spiro-Acridine Compound, Induces in Vitro Antitumor Effect via the ROS-ERK/JNK Signaling Pathway. Molecules 2024, 29, 5344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouveia, R.G.; Ribeiro, A.G.; Segundo, M.Â.S.P.; de Oliveira, J.F.; de Lima, M.d.C.A.; de Lima Souza, T.R.C.; de Almeida, S.M.V.; de Moura, R.O. Synthesis, DNA and Protein Interactions and Human Topoisomerase Inhibition of Novel Spiroacridine Derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 5911–5921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F.S.; Sousa, G.L.S.; Rocha, J.C.; Ribeiro, F.F.; de Oliveira, M.R.; de Lima Grisi, T.C.S.; Araújo, D.A.M.; Nobre, M.S.d.C.; Castro, R.N.; Amaral, I.P.G.; et al. In Vitro Anti-Leishmania Activity and Molecular Docking of Spiro-Acridine Compounds as Potential Multitarget Agents against Leishmania Infantum. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 49, 128289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira Viana, J.; Sena Mendes, M.; Santos Castilho, M.; Olímpio de Moura, R.; Guimarães Barbosa, E. Spiro-Acridine Compound as a Pteridine Reductase 1 Inhibitor: In Silico Target Fishing and in Vitro Studies. ChemMedChem 2024, 19, e202300545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albino, S.; Nobre, M.; da Silva, J.; dos Reis, M.; Nascimento, M.; de Oliveira, M.; Borges, T.; Albuquerque, L.; Kuckelhaus, S.; Alves, L.; et al. Synthesis, Biological Evaluation, Molecular Dynamics, and QM-MM Calculation of Spiro-Acridine Derivatives Against Leishmaniasis. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Viana, J.; Silva e Souza, E.; Sbaraini, N.; Vainstein, M.H.; Gomes, J.N.S.; de Moura, R.O.; Barbosa, E.G. Scaffold Repositioning of Spiro-Acridine Derivatives as Fungi Chitinase Inhibitor by Target Fishing and in Vitro Studies. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.d.M.; Macedo, T.S.; Teixeira, H.M.P.; Moreira, D.R.M.; Soares, M.B.P.; Pereira, A.L.d.C.; Serafim, V.d.L.; Mendonça-Júnior, F.J.B.; de Lima, M.d.C.A.; de Moura, R.O.; et al. Correlation between DNA/HSA-Interactions and Antimalarial Activity of Acridine Derivatives: Proposing a Possible Mechanism of Action. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2018, 189, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, A.D.T.d.O.; de Miranda, M.D.S.; Jacob, Í.T.T.; Amorim, C.A.d.C.; de Moura, R.O.; da Silva, S.Â.S.; Soares, M.B.P.; de Almeida, S.M.V.; Souza, T.R.C.d.L.; de Oliveira, J.F.; et al. Synthesis, in Vitro and in Vivo Biological Evaluation, COX-1/2 Inhibition and Molecular Docking Study of Indole-N-Acylhydrazone Derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 5388–5396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, K.R.d.L.P.; da Silva, S.C.; Marchand, P.; Barreto Mota, F.V.; de Assis Correia, J.C.; Gomes Silva, J.d.A.; de Lima, G.T.; Santana, M.A.; da Silva Moura, W.C.; Dos Santos, V.L.; et al. Effects of Acylhydrazone Derivatives on Experimental Pulmonary Inflammation by Chemical Sensitization. Anti-Inflamm. Anti-Allergy Agents Med. Chem. 2022, 21, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima Porto Ramos, K.R.; Silva, J.d.A.G.; de Sousa, R.S.; de Oliveira Borba, E.F.; de Farias Silva, M.G.; Albino, S.L.; Paz, S.T.; Soares da Silva, R.; Peixoto, C.A.; dos Santos, V.L.; et al. N-Acyl Hydrazone Derivatives Reduce pro-Inflammatory Cytokines, INOS and COX-2 in Acute Lung Inflammation Model. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2025, 420, 111677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.-K.; Jia, Z.-M.; Liu, W.-Q.; Gu, Y.-Z.; Xi, J.-H.; Xu, J.; Yang, G.-Z.; Yang, X.-Z.; Chen, Y. Synthesis and Antiproliferative Evaluation of New Hybrids of Piperine and Acylhydrazone. Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşci, H.; Hökelek, T.; Sağlik, B.N.; Kaynak, F.B.; Tozkoparan, B.; Kelekçi, N.G. Synthesis, Characterization, and MAO Inhibitory Activities of Three New Drug-like N-Acylhydrazone Derivatives. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1318, 139228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemirembe, K.; Cabrera, M.; Cui, L. Interactions between Tafenoquine and Artemisinin-Combination Therapy Partner Drug in Asexual and Sexual Stage Plasmodium falciparum. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2017, 7, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, L.; Cabral, L.I.L.; Sena, M.I.; Guerreiro, B.; Rodrigues, A.S.; de Andrade-Neto, V.F.; Cristiano, M.L.S.; Nogueira, F. New Endoperoxides Highly Active in Vivo and in Vitro against Artemisinin-Resistant Plasmodium falciparum. Malar. J. 2018, 17, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, A.; Godara, P.; Prusty, D.; Bashir, M. Plasmodium falciparum Topoisomerases: Emerging Targets for Anti-Malarial Therapy. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 265, 116056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, T.; Chitnumsub, P.; Kamchonwongpaisan, S.; Maneeruttanarungroj, C.; Nichols, S.E.; Lyons, T.M.; Tirado-Rives, J.; Jorgensen, W.L.; Yuthavong, Y.; Anderson, K.S. Exploiting Structural Analysis, in Silico Screening, and Serendipity to Identify Novel Inhibitors of Drug-Resistant Falciparum Malaria. ACS Chem. Biol. 2009, 4, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluyemi, W.M.; Nwokebu, G.; Adewumi, A.T.; Eze, S.C.; Mbachu, C.C.; Ogueli, E.C.; Nwodo, N.; Soliman, M.E.S.; Mosebi, S. The Characteristic Structural and Functional Dynamics of P. Falciparum DHFR Binding with Pyrimidine Chemotypes Implicate Malaria Therapy Design. Chem. Phys. Impact 2024, 9, 100703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayasurya; Gupta, S.; Shah, S.; Pappachan, A. Drug Repurposing for Parasitic Protozoan Diseases. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2024, 207, 23–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Flórez, A.; Galizzi, M.; Izquierdo, L.; Bustamante, J.M.; Rodriguez, A.; Rodriguez, F.; Rodríguez-Cortés, A.; Alberola, J. Repurposing Bioenergetic Modulators against Protozoan Parasites Responsible for Tropical Diseases. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2020, 14, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-Q.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, Q.-X.; Lu, X.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, H.; Dai, J.-G. Repositioning of Antiparasitic Drugs for Tumor Treatment. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 670804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, P.A.T.d.M.; Cardoso, M.V.d.O.; dos Santos, I.R.; Amaro de Sousa, F.; da Conceição, J.M.; Gouveia de Melo Silva, V.; Duarte, D.; Pereira, R.; Oliveira, R.; Nogueira, F.; et al. Dual Parasiticidal Activities of Phthalimides: Synthesis and Biological Profile against Trypanosoma Cruzi and Plasmodium falciparum. ChemMedChem 2020, 15, 2164–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, K.T.; Fisher, G.M.; Firmin, M.; Liepa, A.J.; Wilson, T.; Gardiner, J.; Mohri, Y.; Debele, E.; Rai, A.; Davey, A.K.; et al. Discovery of 1,3,4-Oxadiazoles with Slow-Action Activity against Plasmodium falciparum Malaria Parasites. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 278, 116796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kore, M.; Rao, A.G.; Acharya, D.; Kirwale, S.S.; Bhanot, A.; Govekar, A.; Mohanty, A.K.; Roy, A.; Vembar, S.S.; Sundriyal, S. Design, Synthesis and in Vitro Evaluation of Primaquine and Diaminoquinazoline Hybrid Molecules Against the Malaria Parasite. Chem.–Asian J. 2025, 20, e202401366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Checkley, L.; Ferdig, M.T.; Vennerstrom, J.L.; Miller, M.J. Synthesis and Antimalarial Activity of Amide and Ester Conjugates of Siderophores and Ozonides. BioMetals 2023, 36, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuno, K.; Burrows, J.N.; Duncan, K.; van Huijsduijnen, R.H.; Kaneko, T.; Kita, K.; Mowbray, C.E.; Schmatz, D.; Warner, P.; Slingsby, B.T. Hit and Lead Criteria in Drug Discovery for Infectious Diseases of the Developing World. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatton, M.L.; Martin, L.B.; Cheng, Q. Evolution of Resistance to Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine in Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 2116–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibley, C.H.; Hyde, J.E.; Sims, P.F.; Plowe, C.V.; Kublin, J.G.; Mberu, E.K.; Cowman, A.F.; Winstanley, P.A.; Watkins, W.M.; Nzila, A.M. Pyrimethamine–Sulfadoxine Resistance in Plasmodium falciparum: What Next? Trends Parasitol. 2001, 17, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozovsky, E.R.; Chookajorn, T.; Brown, K.M.; Imwong, M.; Shaw, P.J.; Kamchonwongpaisan, S.; Neafsey, D.E.; Weinreich, D.M.; Hartl, D.L. Stepwise Acquisition of Pyrimethamine Resistance in the Malaria Parasite. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 12025–12030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amusengeri, A.; Tata, R.B.; Tastan Bishop, Ö. Understanding the Pyrimethamine Drug Resistance Mechanism via Combined Molecular Dynamics and Dynamic Residue Network Analysis. Molecules 2020, 25, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, A.; Mohammadnejadi, E.; Razzaghi-Asl, N. Gefitinib Derivatives and Drug-Resistance: A Perspective from Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 163, 107204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Chen, H.; Wei, D.; Wang, J. Molecular Dynamics Simulations Exploring Drug Resistance in HIV-1 Proteases. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2010, 55, 2677–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- José dos Santos Nascimento, I.; Mendonça de Aquino, T.; da Silva Júnior, E.F.; Olimpio de Moura, R. Insights on Microsomal Prostaglandin E2 Synthase 1 (MPGES-1) Inhibitors Using Molecular Dynamics and MM/PBSA Calculations. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2023, 21, 1033–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albino, S.L.; da Silva Moura, W.C.; dos Reis, M.M.L.; Sousa, G.L.S.; da Silva, P.R.; de Oliveira, M.G.C.; Borges, T.K.d.S.; Albuquerque, L.F.F.; de Almeida, S.M.V.; de Lima, M.d.C.A.; et al. ACW-02 an Acridine Triazolidine Derivative Presents Antileishmanial Activity Mediated by DNA Interaction and Immunomodulation. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, I.J.d.S.; de Aquino, T.M.; da Silva-Júnior, E.F. Repurposing FDA-Approved Drugs Targeting SARS-CoV2 3CLpro: A Study by Applying Virtual Screening, Molecular Dynamics, MM-PBSA Calculations and Covalent Docking. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2022, 19, 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, I.J.d.S.; Santos, M.B.; Marinho, W.P.D.J.; de Moura, R.O. Insights to Design New Drugs against Human African Trypanosomiasis Targeting Rhodesain Using Covalent Docking, Molecular Dynamics Simulations, and MM-PBSA Calculations. Curr. Comput.-Aided Drug Des. 2024, 21, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genheden, S.; Ryde, U. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Methods to Estimate Ligand-Binding Affinities. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2015, 10, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trager, W.; Jensen, J.B. Continuous Culture of Plasmodium falciparum: Its Impact on Malaria Research. Int. J. Parasitol. 1997, 27, 989–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, N.F.; de Freitas, M.E.G.; Sidrônio, M.G.S.; Souza, H.D.; Czeczot, A.; Perelló, M.; Fiss, G.F.; Scotti, L.; de Araújo, D.A.M.; Barbosa Filho, J.M.; et al. Preclinical Evaluation of Selene-Ethylenelacticamides in Tuberculosis: Effects Against Active, Dormant, and Resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis and in Vitro Toxicity Investigation. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neese, F. The ORCA Program System. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. Software Update: The ORCA Program System—Version 5.0. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2022, 12, e1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, W. Semiempirical Quantum-Chemical Methods. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2014, 4, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.; Willett, P.; Glen, R.C.; Leach, A.R.; Taylor, R. Development and Validation of a Genetic Algorithm for Flexible Docking. J. Mol. Biol. 1997, 267, 727–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Nascimento, I.J.; da Silva-Júnior, E.F. TNF-α Inhibitors from Natural Compounds: An Overview, CADD Approaches, and Their Exploration for Anti-Inflammatory Agents. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2021, 25, 2317–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Nascimento, I.J.; de Aquino, T.M.; da Silva-Júnior, E.F. Molecular Docking and Dynamics Simulations Studies of a Dataset of NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibitors. Recent Adv. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Discov. 2022, 15, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, K.; Bordoli, L.; Kopp, J.; Schwede, T. The SWISS-MODEL Workspace: A Web-Based Environment for Protein Structure Homology Modelling. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoete, V.; Cuendet, M.A.; Grosdidier, A.; Michielin, O. SwissParam: A Fast Force Field Generation Tool for Small Organic Molecules. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 2359–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Barros, W.A.; Nunes, C.d.S.; Souza, J.A.d.C.R.; Nascimento, I.J.d.S.; Figueiredo, I.M.; de Aquino, T.M.; Vieira, L.; Farias, D.; Santos, J.C.C.; de Fátima, Â. The New Psychoactive Substances 25H-NBOMe and 25H-NBOH Induce Abnormal Development in the Zebrafish Embryo and Interact in the DNA Major Groove. Curr. Res. Toxicol. 2021, 2, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.R.; Guimarães, A.S.; do Nascimento, J.; do Santos Nascimento, I.J.; da Silva, E.B.; McKerrow, J.H.; Cardoso, S.H.; da Silva-Júnior, E.F. Computer-Aided Design of 1,4-Naphthoquinone-Based Inhibitors Targeting Cruzain and Rhodesain Cysteine Proteases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 41, 116213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Kumar, R.; Lynn, A. G_mmpbsa—A GROMACS Tool for High-Throughput MM-PBSA Calculations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014, 54, 1951–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, I.J.d.S.; Mendonça de Aquino, T.; Ferreira da Silva-Júnior, E. Molecular Dynamics Applied to Discover Antiviral Agents. In Frontiers in Computational Chemistry; Bentham Science: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2022; pp. 62–131. [Google Scholar]

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R | Inhibition (%) | IC50 (μM) b | RI c | |||

| 10 μΜ | 3D7-GFP | Dd2 | MRA-1240 | Dd2 | MRA-1240 | ||

| AMTAC-01 |  | 96.8 ± 0.1 | 2.11 ± 0.60 | 1.37 ± 0.46 | 1.66 ± 0.08 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| AMTAC-02 |  | 97.6 ± 0.1 | 3.19 ± 0.49 | 3.12 ± 0.34 | 4.01 ± 0.17 | 1.0 | 1.3 |

| AMTAC-06 |  | 62.4 ± 8.9 | – | – | – | – | – |

| AMTAC-17 |  | 97.4 ± 0.1 | 3.28 ± 0.49 | 3.29 ± 0.38 | 4.09 ± 0.05 | 1.0 | 1.2 |

| AMTAC-21 |  | 91.1 ± 0.1 | 3.78 ± 0.18 | 3.99 ± 0.23 | 4.07 ± 0.27 | 1.0 | 1.1 |

| AMTAC-22 |  | 95.3 ± 0.1 | 3.01 ± 0.52 | 2.34 ± 0.11 | 2.88 ± 0.30 | 0.8 | 1.0 |

| AMTAC-24 |  | 66.8 ± 10.8 | – | – | – | – | – |

| ACMD-01 |  | 9.8 ± 1.6 | – | – | – | – | – |

| JR-06 |  | 12.4 ± 1.0 | – | – | – | – | – |

| JR-09 |  | 14.8 ± 0.4 | – | – | – | – | – |

| JR-10 |  | 12.6 ± 1.4 | – | – | – | – | – |

| JR-11 |  | 13.4 ± 1.4 | – | – | – | – | – |

| JR-18 |  | 14.7 ± 7.2 | – | – | – | – | – |

| JR-19 |  | 16.8 ± 5.0 | – | – | – | – | – |

| JR-28 |  | 5.5 ± 11.5 | – | – | – | – | – |

| CQ a | – | 94.34 ± 0.54 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.26 ± 0.09 | 0.19 ± 0.07 | 11.0 | 7.9 |

| Compound | IC50 (μM) b | SI c | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D7-GFP | Dd2 | MRA-1240 | Vero E6 | 3D7-GFP | Dd2 | MRA-1240 | |

| AMTAC-01 | 2.11 ± 0.60 | 1.37 ± 0.46 | 1.66 ± 0.08 | >100.00 | >47.3 | >72.7 | >60.2 |

| AMTAC-02 | 3.19 ± 0.49 | 3.12 ± 0.34 | 4.01 ± 0.17 | >100.00 | >31.3 | >32.0 | >24.9 |

| AMTAC-17 | 3.28 ± 0.49 | 3.29 ± 0.38 | 4.09 ± 0.05 | >100.00 | >30.5 | >30.4 | >24.5 |

| AMTAC-21 | 3.78 ± 0.18 | 3.99 ± 0.23 | 4.07 ± 0.27 | >100.00 | >26.4 | >25.1 | >24.6 |

| AMTAC-22 | 3.01 ± 0.52 | 2.34 ± 0.11 | 2.88 ± 0.30 | >100.00 | >33.2 | >42.7 | >34.7 |

| CQ a | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.26 ± 0.09 | 0.19 ± 0.07 | >100.00 | >4251.2 | >387.5 | >539.2 |

| Target | RMSD 10 (Å) | FitScore | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMTAC-01 | AMTAC-02 | AMTAC-17 | AMTAC-21 | AMTAC-22 | Standard 11 | ||

| DHODH 1 | 0.78 | 58.22 | 46.79 | 13.49 | 56.60 | 50.98 | 74.96 |

| W-DHFR 2 | 0.41 | 70.45 | 68.33 | 70.36 | 71.33 | 75.16 | 65.65 |

| M-DHFR 3 | 0.46 | 65.53 | 61.73 | 66.78 | 70.66 | 72.85 | 63.45 |

| PNPase 4 | 0.45 | 46.48 | 49.04 | 44.08 | 51.08 | 49.58 | 64.76 |

| Topo II 5 | – | 41.23 | 46.61 | 48.80 | 40.21 | 40.35 | 50.77 |

| ProRS 6 | 1.01 | 48.06 | 56.75 | 48.58 | 53.05 | 55.58 | 67.43 |

| LDH 7 | 0.51 | 50.25 | 49.38 | 54.95 | 53.96 | 54.62 | 56.94 |

| FP2 8 | 0.73 | 70.38 | 74.74 | 69.08 | 79.23 | 74.13 | 108.76 |

| FP3 9 | 1.08 | 78.06 | 72.73 | 63.90 | 80.82 | 74.51 | 131.94 |

| Compound | ΔGbind (kJ.mol−1) | SASA (kJ.mol−1) | Polar solvation (kJ.mol−1) | Electrostatic (kJ.mol−1) | van der Waals (kJ.mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrimethamine 1 | −50.837 ± 10.296 | −14.481 ± 0.821 | 88.637 ± 20.564 | −12.113 ± 14.691 | −112.880 ± 12.000 |

| AMTAC-01 | −68.018 ± 13.969 | −19.119 ± 1.185 | 158.622 ± 32.375 | −47.442 ± 15.868 | −160.079 ± 21.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cavalcanti, M.d.A.T.; Albino, S.L.; Menezes, K.J.d.S.; de Araújo, W.J.S.; Campos, F.d.F.G.R.; dos Reis, M.M.L.; Morais, I.; Duarte, D.M.F.A.; Nascimento, I.J.d.S.; Rodrigues-Junior, V.d.S.; et al. Design, Synthesis, and Antimalarial Evaluation of New Spiroacridine Derivatives. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1214. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121214

Cavalcanti MdAT, Albino SL, Menezes KJdS, de Araújo WJS, Campos FdFGR, dos Reis MML, Morais I, Duarte DMFA, Nascimento IJdS, Rodrigues-Junior VdS, et al. Design, Synthesis, and Antimalarial Evaluation of New Spiroacridine Derivatives. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1214. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121214

Chicago/Turabian StyleCavalcanti, Misael de Azevedo Teotônio, Sonaly Lima Albino, Karla Joane da Silva Menezes, Wallyson Junio Santos de Araújo, Fernanda de França Genuíno Ramos Campos, Malu Maria Lucas dos Reis, Inês Morais, Denise Maria Figueiredo Araújo Duarte, Igor José dos Santos Nascimento, Valnês da Silva Rodrigues-Junior, and et al. 2025. "Design, Synthesis, and Antimalarial Evaluation of New Spiroacridine Derivatives" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1214. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121214

APA StyleCavalcanti, M. d. A. T., Albino, S. L., Menezes, K. J. d. S., de Araújo, W. J. S., Campos, F. d. F. G. R., dos Reis, M. M. L., Morais, I., Duarte, D. M. F. A., Nascimento, I. J. d. S., Rodrigues-Junior, V. d. S., Nogueira, F., & Moura, R. O. d. (2025). Design, Synthesis, and Antimalarial Evaluation of New Spiroacridine Derivatives. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1214. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121214