In Vitro Efficacy of Antibiotic Combinations with Carbapenems and Other Agents against Anaerobic Bacteria

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Antibiotic Susceptibilities of Study Isolates

2.2. Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index (FICI) of Carbapenems and Clindamycin

2.3. FICI of Carbapenems and Minocycline

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

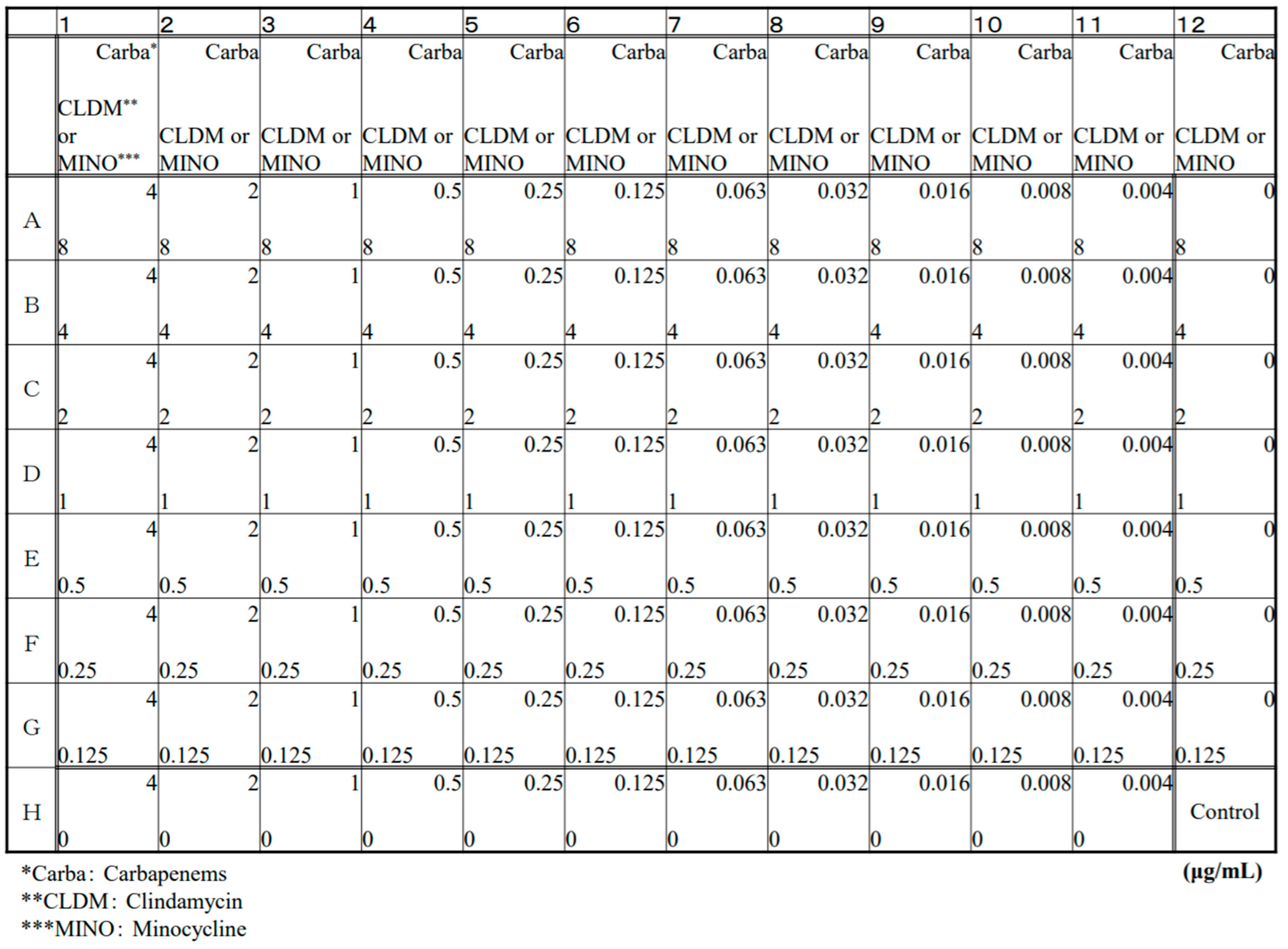

4.1. Antibiotics and Checkerboard Production

4.2. Bacterial Strains

4.3. Antibiotic Susceptibility Test

4.4. Evaluation of Antibiotic Combination Effect

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ngo, J.T.; Parkins, M.D.; Gregson, D.B.; Pitout, J.D.; Ross, T.; Church, D.L.; Laupland, K.B. Population-based assessment of the inci-dence, risk factors, and outcomes of anaerobic bloodstream infections. Infection 2013, 1, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Dennehy, F.; Donoghue, O.; McNicholas, S. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of anaerobic bacteria at an Irish Uni-versity Hospital over a ten-year period (2010–2020). Anaerobe 2021, 7344, 102497. [Google Scholar]

- Umemura, T.; Hamada, Y.; Yamagishi, Y.; Suematsu, H.; Mikamo, H. Clinical characteristics associated with mortality of patients with anaerobic bacteremia. Anaerobe 2016, 39, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, Y.; Park, Y.; Kim, M.; Choi, J.Y.; Yong, D.; Jeong, S.H.; Lee, K. Anaerobic Bacteremia: Impact of Inappropriate Therapy on Mortality. Infect. Chemother. 2016, 48, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Yu, V.L.; Morris, A.J.; McDermott, L.; Wagener, M.W.; Harrell, L.; Snydman, D.R. Antimicrobial Resistance and Clinical Outcome of Bacteroides Bacteremia: Findings of a Multicenter Prospective Observational Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2000, 30, 870–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahar, J.-R.; Farhat, H.; Chachaty, E.; Meshaka, P.; Antoun, S.; Nitenberg, G. Incidence and clinical significance of anaerobic bacteraemia in cancer patients: A 6-year retrospective study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2005, 11, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copsey-Mawer, S.; Hughes, H.; Scotford, S.; Anderson, B.; Davis, C.; Perry, M.D.; Morris, T.E. UK Bacteroides species surveil-lance survey: Change in antimicrobial resistance over 16 years (2000–2016). Anaerobe 2021, 72, 102447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soki, J.; Hedberg, M.; Patrick, S.; Balint, B.; Herczeg, R.; Nagy, I.; Hecht, D.W.; Nagy, E.; Urbán, E. Emergence and evolution of an international cluster of MDR Bacteroides fragilis isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 2441–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, I.; Aoki, K.; Miura, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Matsumoto, T. Fatal sepsis caused by multidrug-resistant Bacteroides fragilis, harboring a cfiA gene and an upstream insertion sequence element, in Japan. Anaerobe 2017, 44, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Könönen, E.; Bryk, A.; Niemi, P.; Kanervo-Nordström, A. Antimicrobial Susceptibilities of Peptostreptococcus anaerobius and the Newly Described Peptostreptococcus stomatis Isolated from Various Human Sources. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 2205–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fujita, K.; Takata, I.; Sugiyama, H.; Suematsu, H.; Yamagishi, Y.; Mikamo, H. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of clinical isolates of the anaerobic bacteria which can cause aspiration pneumonia. Anaerobe 2019, 57, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.Y.; Huang, Y.T.; Liao, C.H.; Yen, L.C.; Lin, H.Y.; Hsueh, P.R. Increasing trends in antimicrobial resistance among clin-ically important anaerobes and Bacteroides fragilis isolates causing nosocomial infections: Emerging resistance to carbapenems. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 3161–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, W.; Shahin, M.; Rotimi, V. Surveillance and trends of antimicrobial resistance among clinical isolates of anaerobes in Kuwait hospitals from 2002 to 2007. Anaerobe 2010, 16, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snydman, D.R.; Jacobus, N.V.; McDermott, L.A.; Golan, Y.; Hecht, D.W.; Goldstein, E.J.C.; Harrell, L.J.; Jenkins, S.; Newton, D.; Pierson, C.; et al. Lessons Learned from the Anaerobe Survey: Historical Perspective and Review of the Most Recent Data (2005–2007). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 50, S26–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ednie, L.M.; Credito, K.L.; Khantipong, M.; Jacobs, M.R.; Appelbaum, P.C. Synergic activity, for anaerobes, of trovafloxacin with clindamycin or metronidazole: Chequerboard and time-kill methods. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2000, 45, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inubushi, J.; Liang, K. Update on minocycline in vitro activity against odontogenic bacteria. J. Infect. Chemother. 2020, 26, 1334–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateda, K.; Ishii, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Yamaguchi, K. ‘Break-point Checkerboard Plate’ for screening of appropriate antibiotic combinations against multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 38, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, I.; Yamaguchi, T.; Tsukimori, A.; Sato, A.; Fukushima, S.; Mizuno, Y.; Matsumoto, T. Effectiveness of antibiotic combination therapy as evaluated by the Break-point Checkerboard Plate method for multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in clinical use. J. Infect. Chemother. 2014, 4, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, J.L.; Cheng, N.; Chow, A.W. Interactions of ciprofloxacin with clindamycin, metronidazole, cefoxitin, cefotaxime, and mezlocillin against gram-positive and gram-negative anaerobic bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1987, 31, 1379–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fass, R.J.; Ruiz, D.E.; Prior, R.B.; Perkins, R.L. In Vitro Activity of Gentamicin and Minocycline Alone and in Combination Against Bacteria Associated with Intra-Abdominal Sepsis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1976, 10, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Takeda, M.; Narikawa, S.; Hosoyamada, M.; Cha, S.H.; Sekine, T.; Endou, H. Characterization of organic anion transport inhibitors using cells stably expressing human organic anion transporters. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 419, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, H.; Kunitomo, W.; Kaori, B.; Kato, N.; Ueno, N. The effect of clindamycin on antibacterial activity of β-lactam antibiotics against β-lactamase high-producing Bacteroides fragilis. Prog. Med. 1991, 11, 2647–2652. [Google Scholar]

- Zaleznik, D.F.; Zhang, Z.; Onderdonk, A.B.; Kasper, D.L. Effect of Subinhibitory Doses of Clindamycin on the Virulence of Bacteroides fragilis: Role of Lipopolysaccharide. J. Infect. Dis. 1986, 154, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, C.C.; Sanders, W.E., Jr.; Goering, R.V. Influence of Clindamycin on derepression of β-lactamase in Enterobacter spp. and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983, 24, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, E. Anaerobic infections: Update on treatment considerations. Drugs 2010, 70, 841–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, H.S.; Shadomy, S.V.; Boyer, A.E.; Chuvala, L.; Riggins, R.; Kesterson, A.; Myrick, J.; Craig, J.; Candela, M.G.; Barr, J.R.; et al. Evaluation of Combination Drug Therapy for Treatment of Antibiotic-Resistant Inhalation Anthrax in a Murine Model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e00788-e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beganovic, M.; Daffinee, K.E.; Luther, M.K.; La Plante, K.L. Minocycline Alone and in Combination with Polymyxin B, Meropenem, and Sulbactam against Carbapenem-Susceptible and -Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in an In Vitro Pharmacodynamic Model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2021, 65, e01680-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhanel, G.G.; Wiebe, R.; Dilay, L.; Thomson, K.; Rubinstein, E.; Hoban, D.J.; Noreddin, A.M.; Karlowsky, J.A. Comparative Review of the Carbapenems. Drugs 2007, 67, 1027–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, M.I.; Shaker, M.A.; Mady, F.M. Imipenem/cilastatin encapsulated polymeric nanoparticles for destroying car-bapenem-resistant bacterial isolates. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goa, K.L.; Noble, S. Panipenem/Betamipron. Drugs 2003, 63, 913–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P.-L.; Yau, C.-Y.; Ho, L.-Y.; Lai, E.L.-Y.; Liu, M.C.-J.; Tse, C.W.-S.; Chow, K.-H. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Bacteroides fragilis group organisms in Hong Kong by the tentative EUCAST disc diffusion method. Anaerobe 2017, 47, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyanova, L.; Markovska, R.; Mitov, I. Multidrug resistance in anaerobes. Futur. Microbiol. 2019, 14, 1055–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadarangani, S.P.; Cunningham, S.A.; Jeraldo, P.R.; Wilson, J.W.; Khare, R.; Patel, R. Metronidazole- and car-bapenem-resistant bacteroides thetaiotaomicron isolated in Rochester, Minnesota. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 4157–4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brook, I.; Walker, R.I. Interaction between penicillin, clindamycin or metronidazole and gentamicin against species of clostridia and anaerobic and facultatively anaerobic Gram-positive cocci. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1985, 15, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, B.A.; Tang, H.J.; Wang, Y.Y.; Liu, Y.C.; Ko, W.C.; Liu, C.Y.; Chuang, Y.C. In vitro antimicrobial effect of cefazolin and cefotaxime combined with minocycline against Vibrio cholerae non-O1 non-O139. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2005, 38, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matthew, N.L.; Harriet, M.L. Meropenem an updated review of its use in the management of intrrra-abdominal infections. Drugs 2000, 60, 619–641. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically, 9th ed.; Approved Standard; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Malvern, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yap, J.K.Y.; Tan, S.Y.Y.; Tang, S.Q.; Thien, V.K.; Chan, E.W.L. Synergistic Antibacterial Activity between 1,4-Naphthoquinone and β-Lactam Antibiotics against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Microb. Drug Resist. 2021, 27, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MIC (μg/mL) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | MIC50 | MIC90 | ||

| B. fragilis | (n = 18) | |||

| IPM | 0.063–1 | 0.125 | 0.5 | |

| MEPM | 0.008–1 | 0.125 | 1 | |

| DRPM | 0.032–1 | 0.125 | 1 | |

| BIPM | 0.032–2 | 0.125 | 1 | |

| PAPM | 0.063–2 | 0.25 | 2 | |

| CLDM | 0.25–8< | 0.75 | 8< | |

| MINO | 1–8< | 2 | 8< | |

| B. thetaiotaomicron | (n = 20) | |||

| IPM | 0.25–1 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| MEPM | 0.032–1 | 0.125 | 0.25 | |

| DRPM | 0.125–1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| BIPM | 0.06–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | |

| PAPM | 0.25–2 | 0.5 | 2 | |

| CLDM | 1–8< | 6 | 8< | |

| MINO | 1–4 | 2 | 4 | |

| P. distasonis | (n = 20) | |||

| IPM | 0.5–2 | 1 | 2 | |

| MEPM | 0.25–2 | 0.75 | 2 | |

| DRPM | 0.063–2 | 0.5 | 2 | |

| BIPM | 0.032–1 | 0.125 | 0.5 | |

| PAPM | 0.03–2 | 0.125 | 2 | |

| CLDM | 0.25–8< | 4 | 8< | |

| MINO | 1–8< | 2 | 4 | |

| P. anaerobius | (n = 12) | |||

| IPM | 0.03–1 | 0.125 | 1 | |

| MEPM | 0.015–1 | 0.125 | 0.5 | |

| DRPM | 0.06–1 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| BIPM | 0.03–1 | 0.125 | 0.5 | |

| PAPM | 0.12–2 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| CLDM | 0.25–8< | 0.5 | 8< | |

| MINO | 1–8< | 2 | 4 | |

| FICI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤0.5 Synergistic | >0.5 to ≤1.0 Additive | >1.0 to ≤2.0 Indifferent | >2.0 Antagonistic | |

| B. fragilis (n = 18) | ||||

| Imipenem | 0 | 6 (33.3%) | 11 (61.1%) | 1 (5.6%) |

| Meropenem | 0 | 6 (33.3%) | 9 (50.0%) | 3 (16.7%) |

| Doripenem | 3 (16.6%) | 4 (22.2%) | 10 (55.6%) | 1 (5.6%) |

| Biapenem | 0 | 7 (38.8%) | 10 (55.6%) | 1 (5.6%) |

| Panipenem | 0 | 7 (38.8%) | 10 (55.6%) | 1 (5.6%) |

| B. thetaiotaomicron (n = 20) | ||||

| Imipenem | 1 (5.0%) | 11 (55.0%) | 8 (40.0%) | 0 |

| Meropenem | 0 | 4 (20.0%) | 15 (75.0%) | 1 (5.0%) |

| Doripenem | 0 | 6 (30.0%) | 11 (55.0%) | 3 (15.0%) |

| Biapenem | 0 | 10 (50.0%) | 8 (40.0%) | 2 (10.0%) |

| Panipenem | 0 | 6 (30.0%) | 13 (65.0%) | 1 (5.0%) |

| P. distasonis (n = 20) | ||||

| Imipenem | 0 | 12 (60.0%) | 8 (40.0%) | 0 |

| Meropenem | 0 | 10 (50.0%) | 9 (45.0%) | 1 (5.0%) |

| Doripenem | 0 | 5 (25.0%) | 12 (60.0%) | 3 (15.0%) |

| Biapenem | 0 | 10 (50.0%) | 8 (40.0%) | 2 (10.0%) |

| Panipenem | 0 | 5 (25.0%) | 14 (70.0%) | 1 (5.0%) |

| P. anaerobius (n = 12) | ||||

| Imipenem | 4 (33.3%) | 8 (66.7%) | 0 | 0 |

| Meropenem | 4 (33.3%) | 8 (66.7%) | 0 | 0 |

| Doripenem | 6 (50.0%) | 4 (33.3%) | 2 (16.7%) | 0 |

| Biapenem | 7 (58.4%) | 4 (33.3%) | 1 (8.3%) | 0 |

| Panipenem | 2 (16.7%) | 8 (66.6%) | 2 (16.7%) | 0 |

| FICI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤0.5 Synergistic | >0.5 to ≤1.0 Additive | >1.0 to ≤2.0 Indifferent | >2.0 Antagonistic | |

| B. fragilis (n = 18) | ||||

| Imipenem | 1 (5.6%) | 12 (66.6%) | 4 (22.2%) | 1 (5.6%) |

| Meropenem | 0 | 7 (38.9%) | 11 (61.1%) | 0 |

| Doripenem | 0 | 6 (33.3%) | 12 (66.7%) | 0 |

| Biapenem | 0 | 7 (38.9%) | 9 (50.0%) | 2 (11.1%) |

| Panipenem | 0 | 7 (38.9%) | 10 (55.5%) | 1 (5.6%) |

| B. thetaiotaomicron (n = 20) | ||||

| Imipenem | 0 | 15 (75.0%) | 5 (25.0%) | 0 |

| Meropenem | 0 | 4 (20.0%) | 16 (80.0%) | 0 |

| Doripenem | 0 | 5 (25.0%) | 15 (75.0%) | 0 |

| Biapenem | 0 | 12 (60.0%) | 8 (40.0%) | 0 |

| Panipenem | 0 | 6 (30.0%) | 13 (65.0%) | 1 (5.0%) |

| P. distasonis (n = 20) | ||||

| Imipenem | 0 | 16 (80.0%) | 4 (20.0%) | 0 |

| Meropenem | 0 | 6 (30.0%) | 14 (70.0%) | 0 |

| Doripenem | 0 | 7 (35.0%) | 13 (65.0%) | 0 |

| Biapenem | 0 | 6 (30.0%) | 14 (70.0%) | 0 |

| Panipenem | 1 (5.0%) | 6 (30.0%) | 13 (65.0%) | 0 |

| P. anaerobius (n = 12) | ||||

| Imipenem | 4 (33.3%) | 8 (66.7%) | 0 | 0 |

| Meropenem | 4 (33.3%) | 7 (58.3%) | 1 (8.3%) | 0 |

| Doripenem | 1 (8.3%) | 11 (91.7%) | 0 | 0 |

| Biapenem | 0 | 12 (100.0%) | 0 | 0 |

| Panipenem | 1 (8.3%) | 11 (91.7%) | 0 | 0 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Umemura, T.; Hagihara, M.; Mori, T.; Mikamo, H. In Vitro Efficacy of Antibiotic Combinations with Carbapenems and Other Agents against Anaerobic Bacteria. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11030292

Umemura T, Hagihara M, Mori T, Mikamo H. In Vitro Efficacy of Antibiotic Combinations with Carbapenems and Other Agents against Anaerobic Bacteria. Antibiotics. 2022; 11(3):292. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11030292

Chicago/Turabian StyleUmemura, Takumi, Mao Hagihara, Takeshi Mori, and Hiroshige Mikamo. 2022. "In Vitro Efficacy of Antibiotic Combinations with Carbapenems and Other Agents against Anaerobic Bacteria" Antibiotics 11, no. 3: 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11030292

APA StyleUmemura, T., Hagihara, M., Mori, T., & Mikamo, H. (2022). In Vitro Efficacy of Antibiotic Combinations with Carbapenems and Other Agents against Anaerobic Bacteria. Antibiotics, 11(3), 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11030292