Advances in Coumarin Fluorescent Probes for Medical Diagnostics: A Review of Recent Developments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Coumarins, Structure, Diversity, and Synthetic Pathways

3. Optical Properties and Mechanisms of Action Fluorescent Probes

3.1. Photophysical Characteristics of Coumarins

3.2. Fluorescence Mechanisms of Coumarin Sensors

3.2.1. PeT (Photoinduced Electron Transfer)

3.2.2. ICT (Intramolecular Charge Transfer)

3.2.3. ESIPT (Excited-State Intramolecular Proton Transfer)

3.2.4. Other Sensing Mechanisms

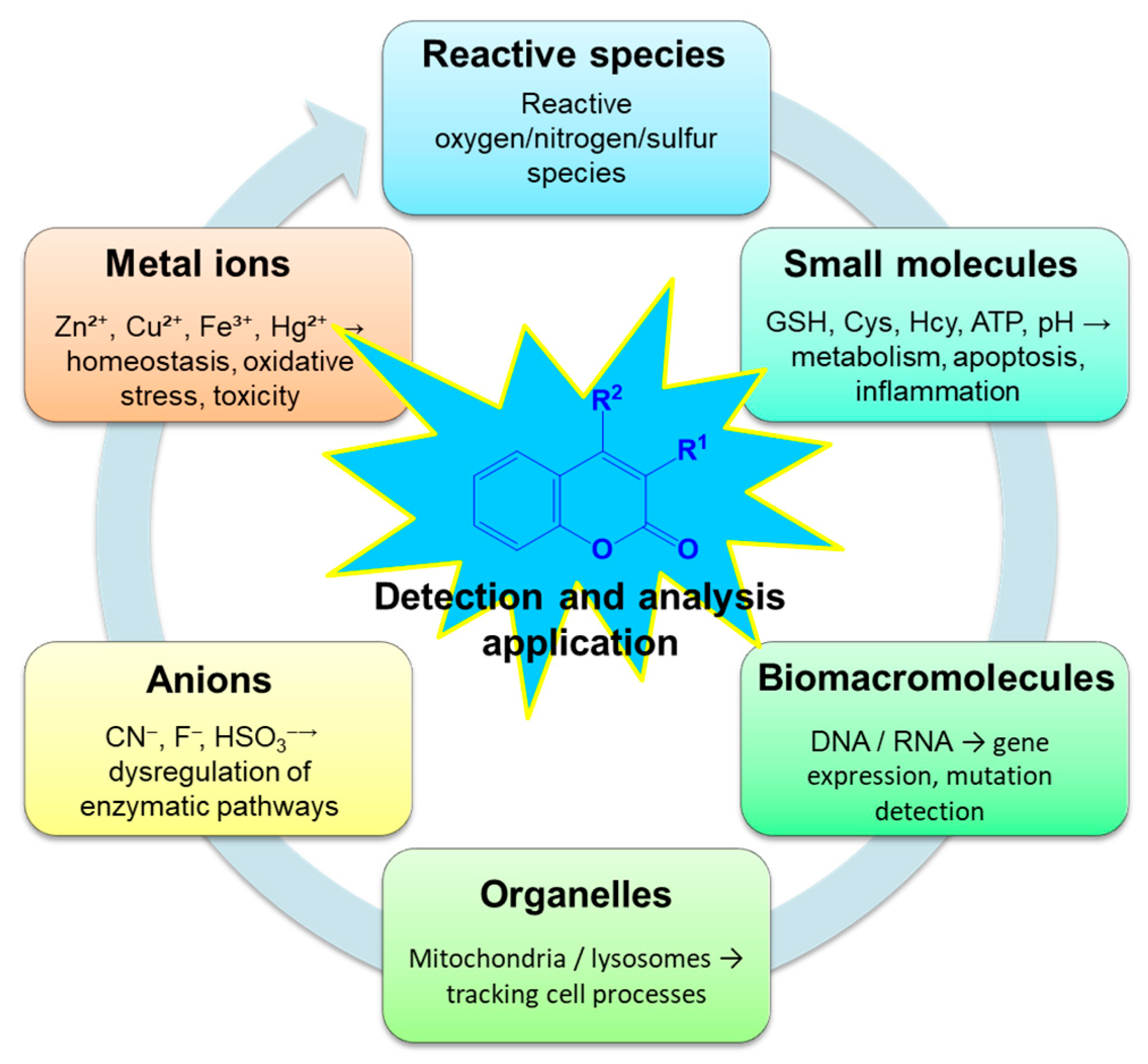

4. Coumarin Fluorescent Probes in the Detection of Biological Biomarkers

4.1. Coumarin-Based Probes for Biologically Relevant Small Molecules

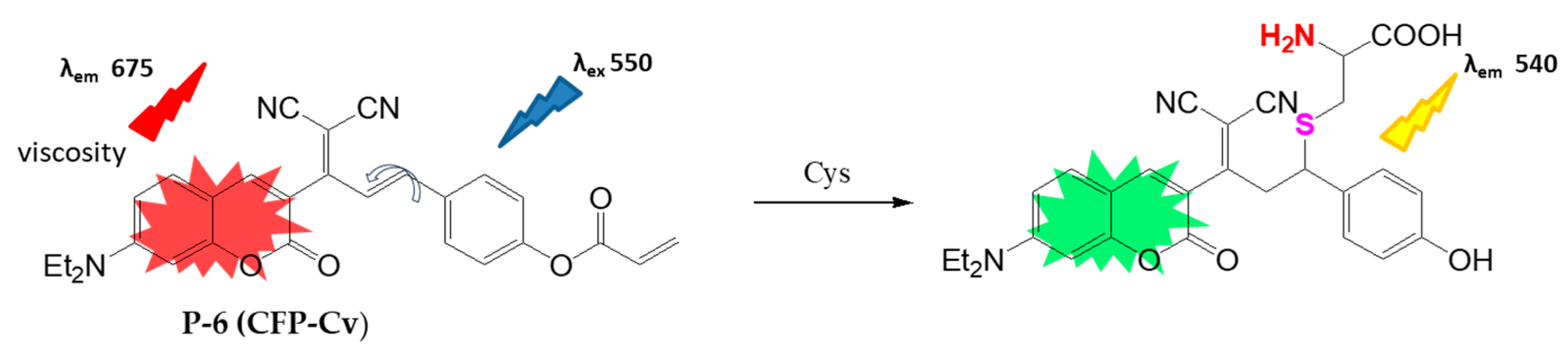

4.1.1. Biothiol Detection

4.1.2. Formaldehyde Detection

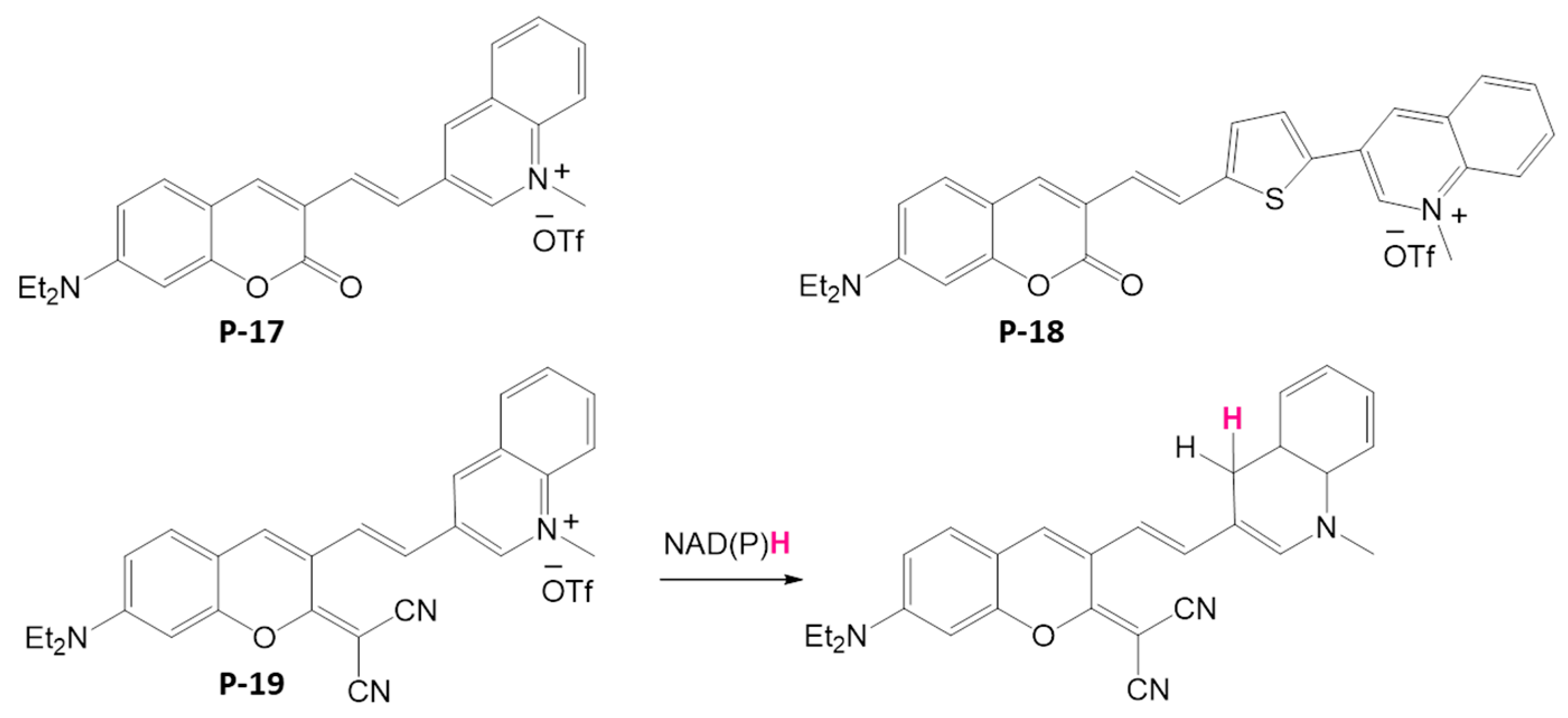

4.1.3. NADH and NADPH Detection

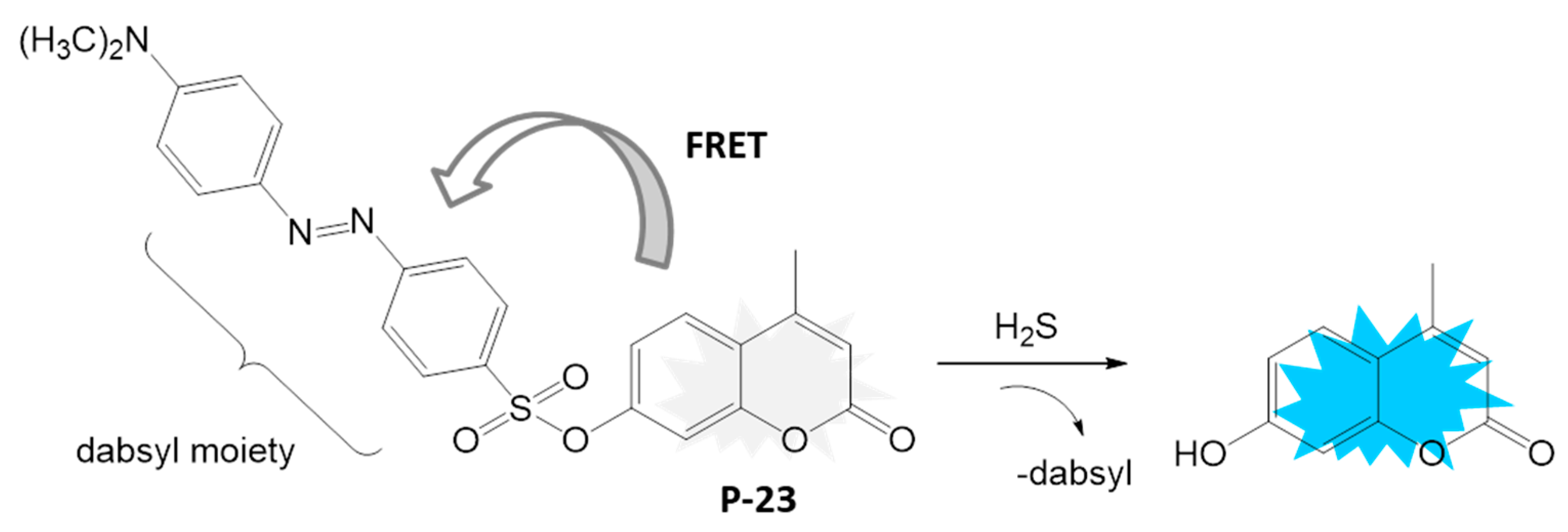

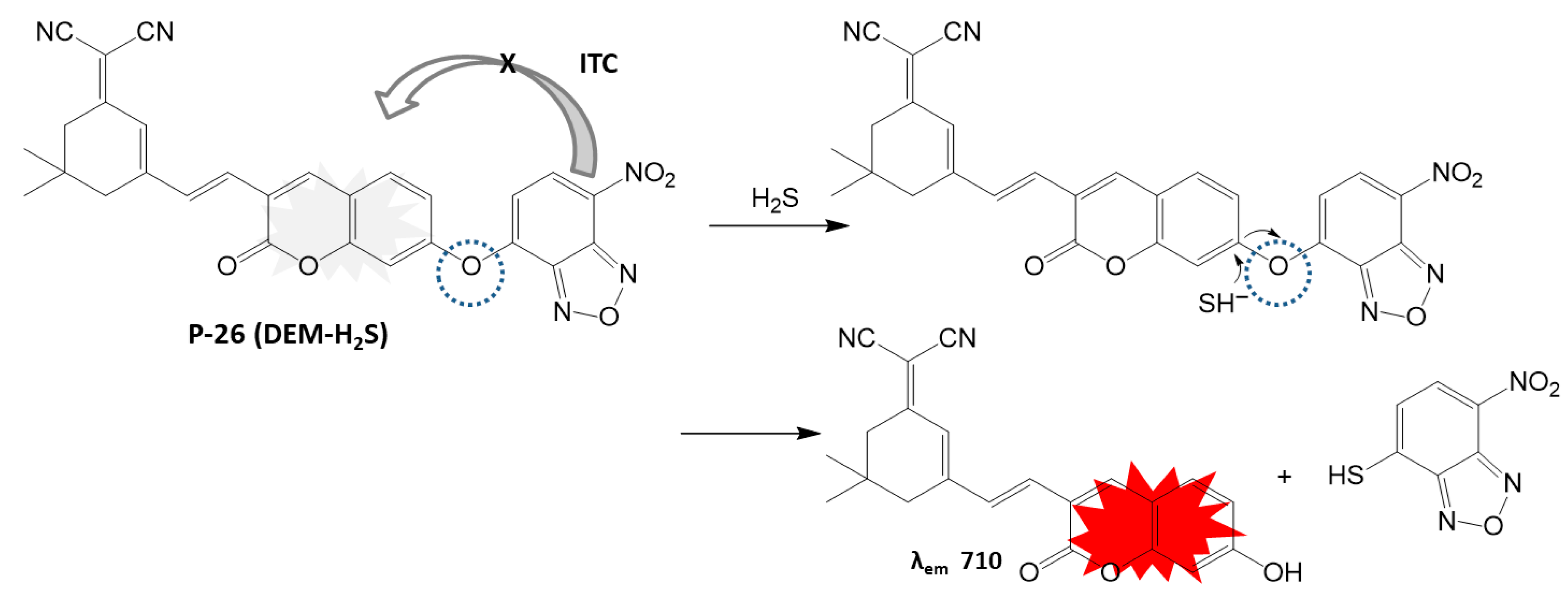

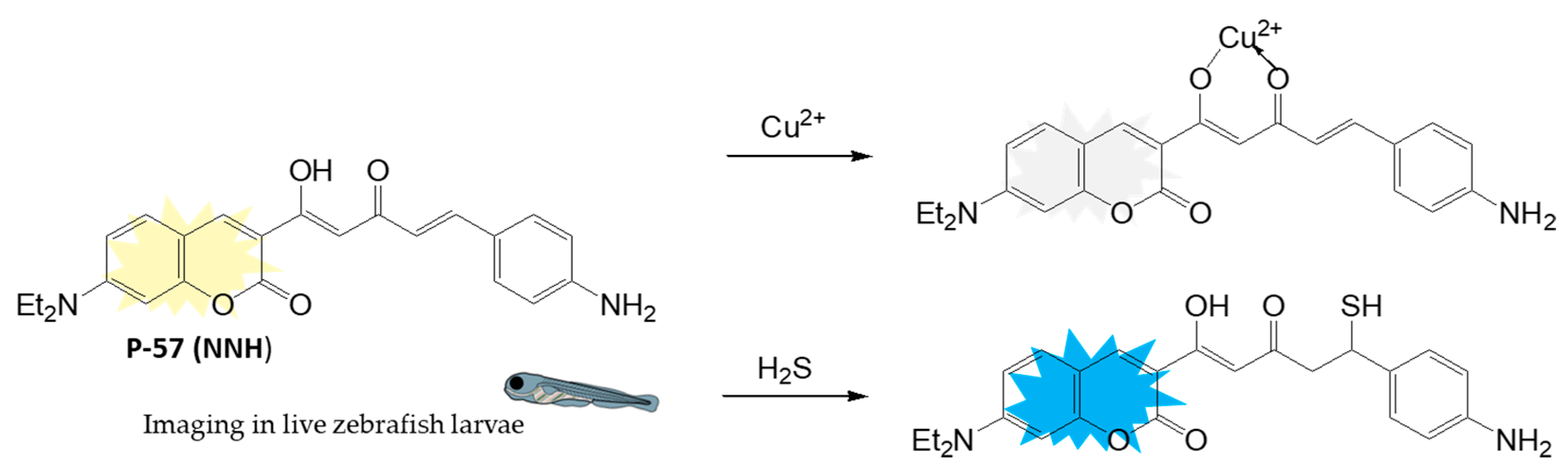

4.1.4. H2S Detection

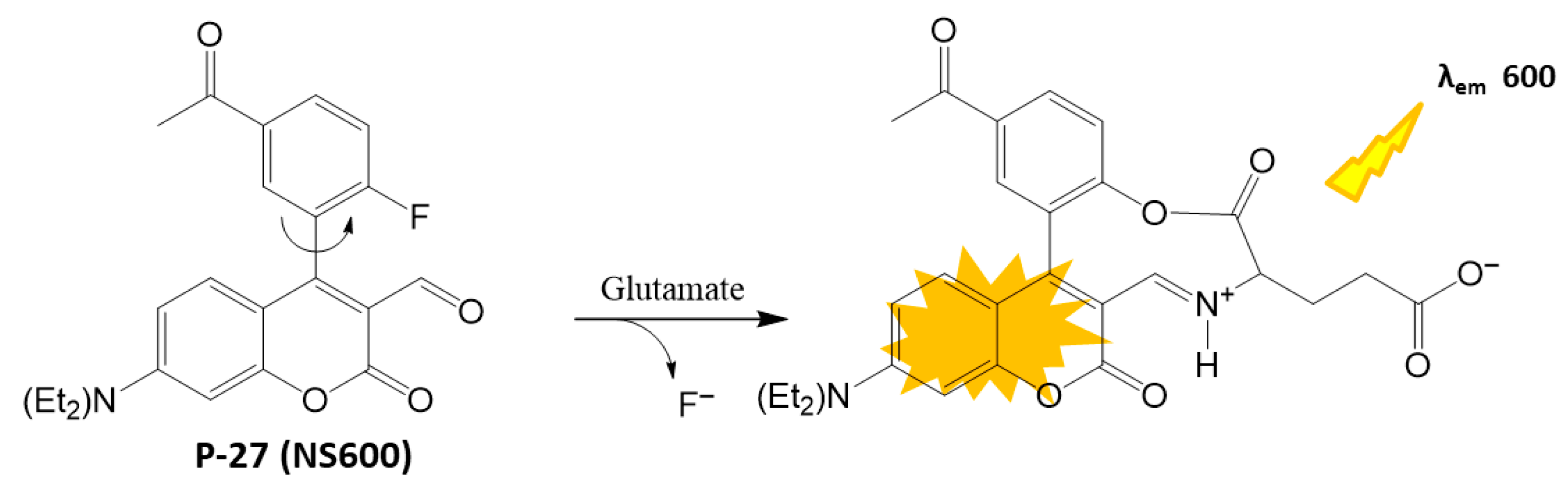

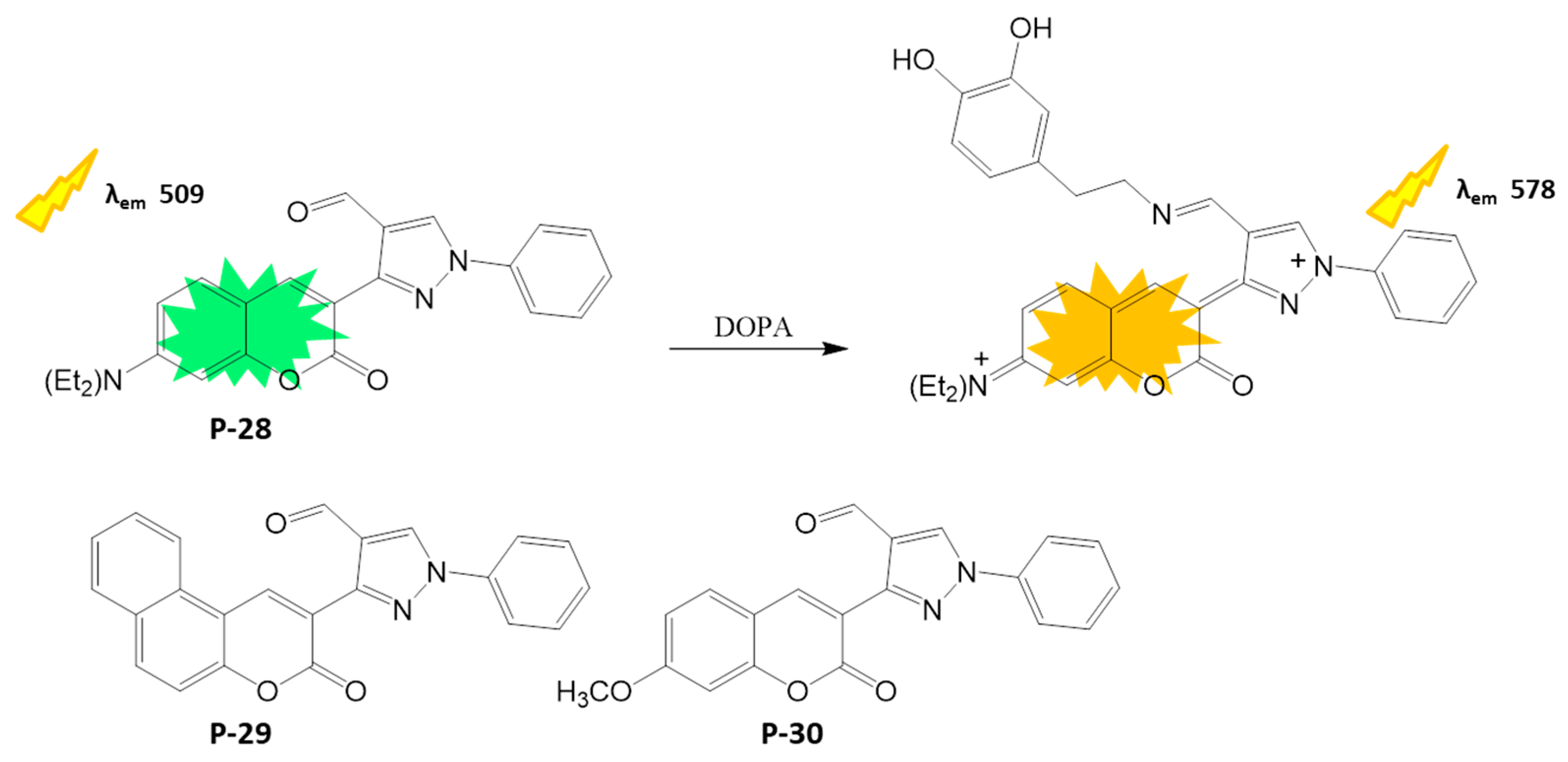

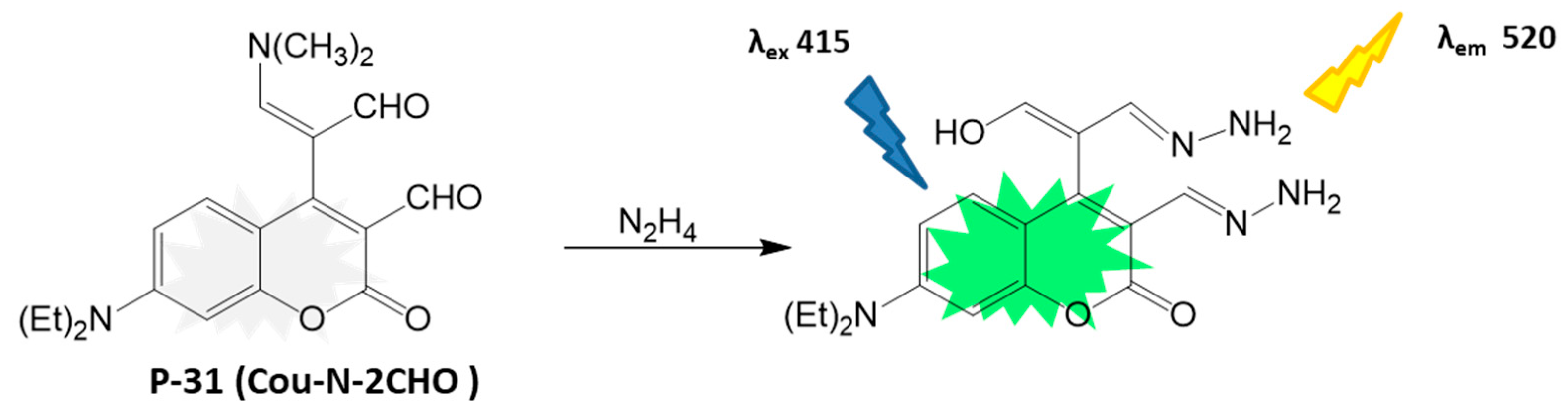

4.1.5. Neurotransmitter Detection

4.1.6. Detection of Other Small Molecules

4.2. Probes for Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species

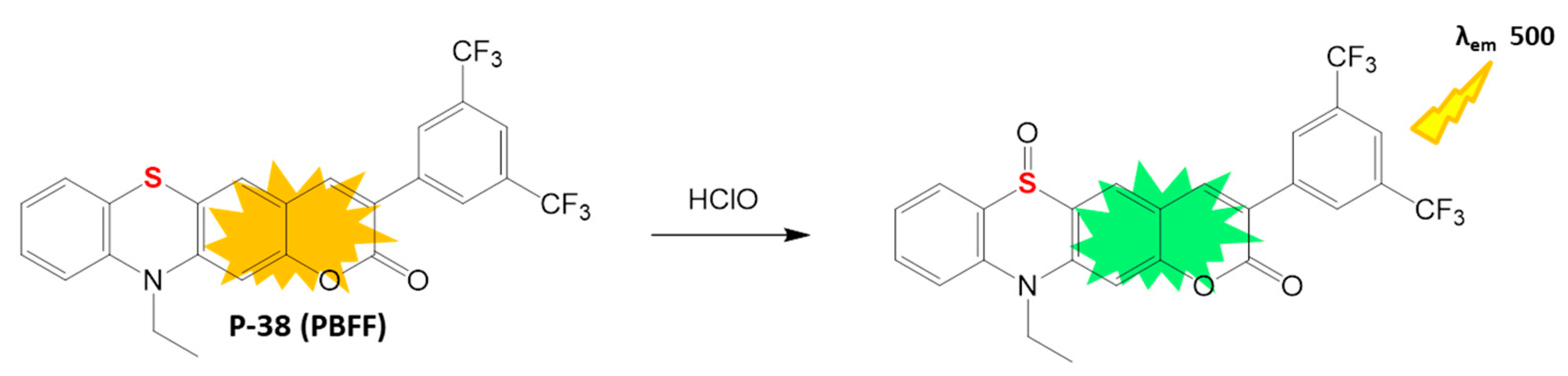

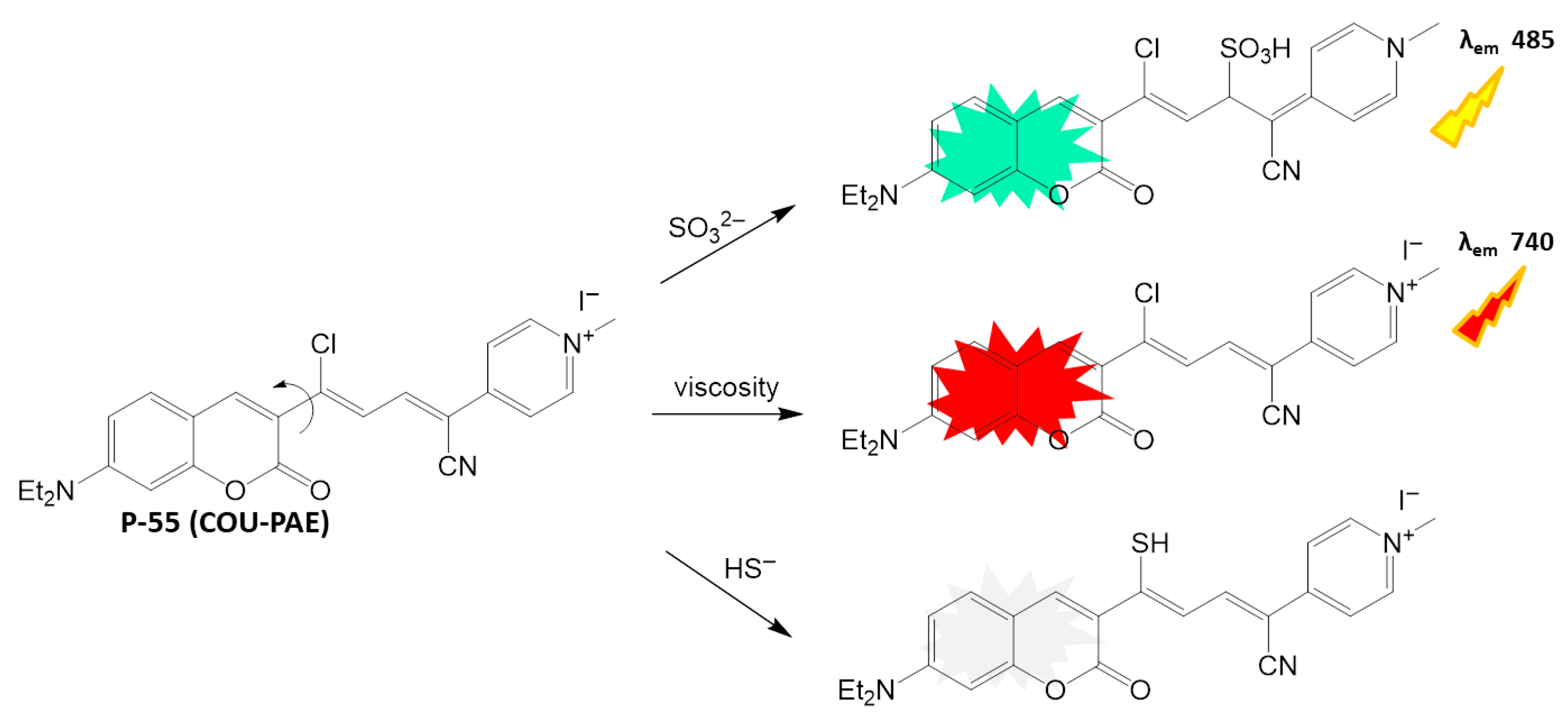

4.2.1. HClO Detection

4.2.2. H2O2 Detection

4.2.3. HNO Detection

4.2.4. ONOO− Detection

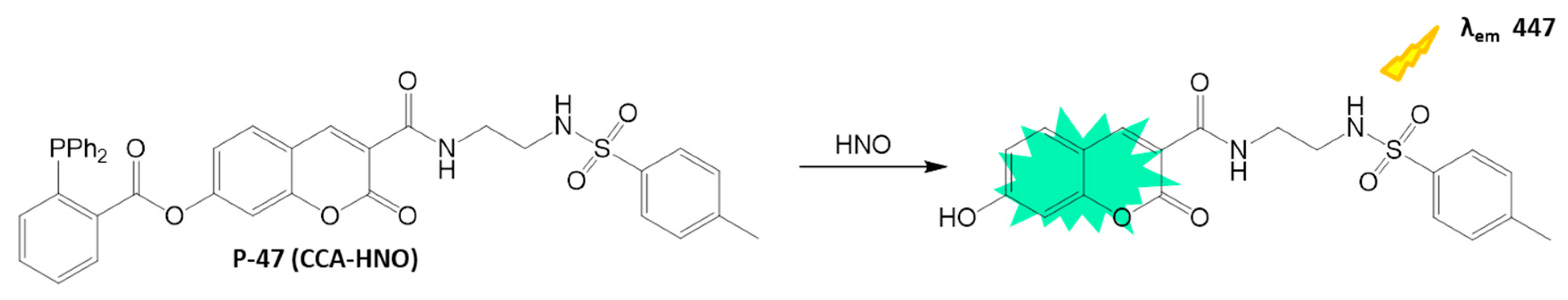

4.3. Probes for Detection of Anions and Cations

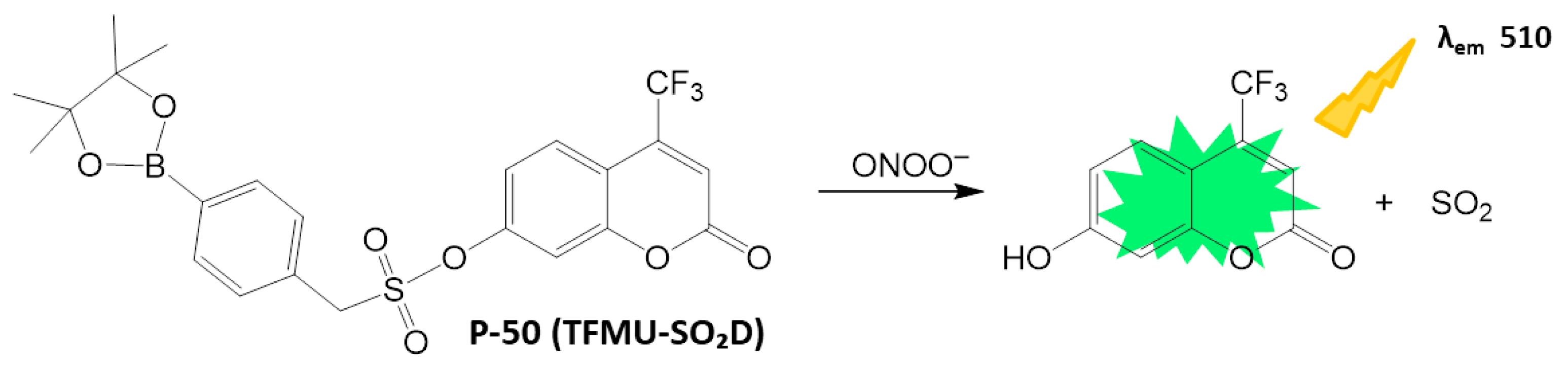

4.3.1. Anions Detection

4.3.2. Metal Detection

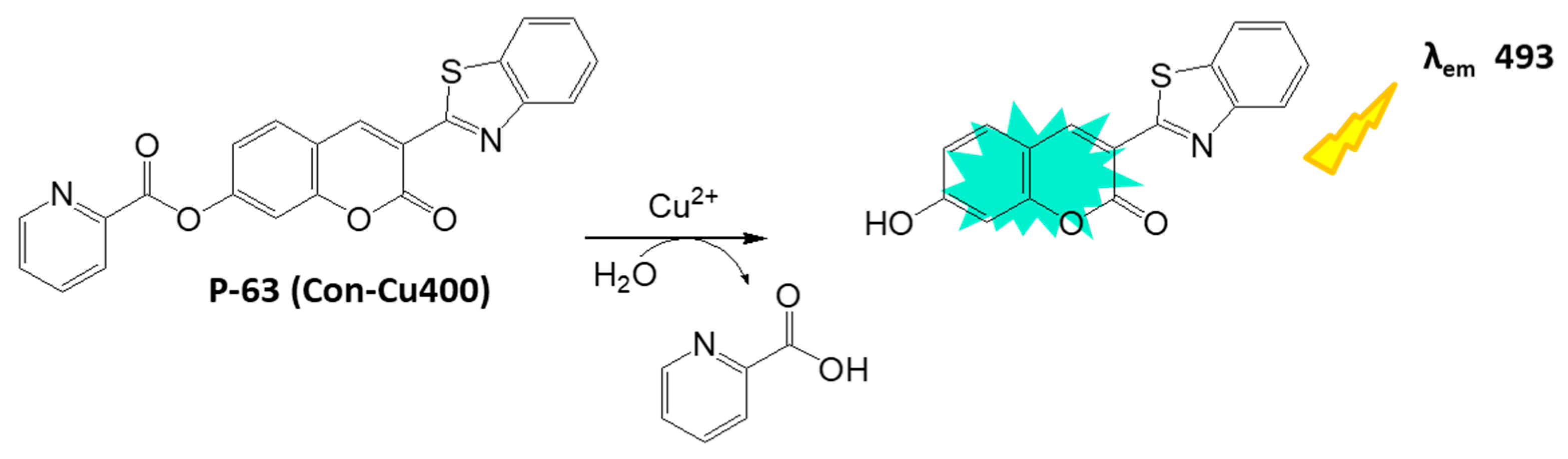

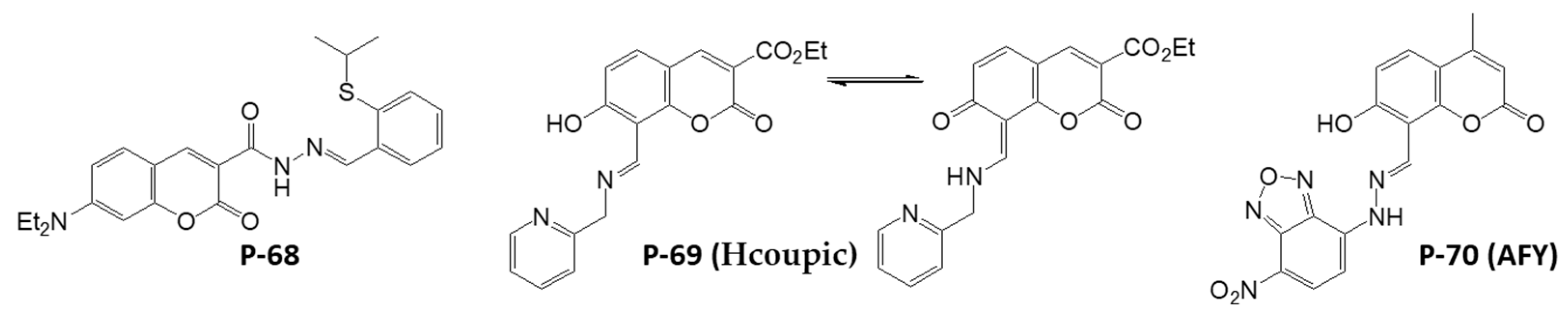

Cu2+/Al3+ Detection

Hg2+ Detection

Detection of Other Metals

4.4. Subcellular- and Structure-Targeted Probes

4.5. Emerging Anticancer and Theranostic Coumarin-Based Probes

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Langhals, H. Fluorescence and Fluorescent Dyes. Phys. Sci. Rev. 2020, 5, 20190100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dsouza, R.N.; Pischel, U.; Nau, W.M. Fluorescent Dyes and Their Supramolecular Host/Guest Complexes with Macrocycles in Aqueous Solution. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 7941–7980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Da, Y.; Tian, Y. Fluorescent Proteins and Genetically Encoded Biosensors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 1189–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menchicchi, B.; Stiel, A.C.; Nieddu, M.; Fuenzalida-Werner, J.P. Fluorescent proteins: A journey from the cell to extreme environments in material science. Photochem. Photobiol 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyawaki, A. Proteins on the Move: Insights Gained from Fluorescent Protein Technologies. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 656–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, P.W.; Kim, G.J.; Kim, J.S. A Short Guide on Blue Fluorescent Proteins: Limits and Perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonasera, K.; Galletta, M.; Calvo, M.R.; Pezzotti Escobar, G.; Leonardi, A.A.; Irrera, A. Organic Fluorescent Sensors for Environmental Analysis: A Critical Review and Insights into Inorganic Alternatives. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, M.; Li, X.; Fan, Y.; Li, J.; Lu, K.; Wen, H.; Ren, J. Recent Advances of Fluorescent Sensors for Bacteria Detection—A Review. Talanta 2022, 254, 124133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loskutova, A.; Seitkali, A.; Aliyev, D.; Bukasov, R. Quantum Dot-Based Luminescent Sensors: Review from Analytical Perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanbarlou, S.; Kahforoushan, D.; Abdollahi, H.; Zarrintaj, P.; Alomar, A.; Villanueva, C.; Davachi, S.M. Advances in Quantum Dot-Based Fluorescence Sensors for Environmental and Biomedical Detection. Talanta 2025, 294, 128176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, R.; Kumar, J.; Singh, M. Fluorescent Carbon Dots for Sensing Applications: A Review. Anal. Sci. 2024, 40, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halicka, K.; Meloni, F.; Czok, M.; Spychalska, K.; Baluta, S.; Malecha, K.; Pilo, M.I.; Cabaj, J. New Trends in Fluorescent Nanomaterials-Based Bio/Chemical Sensors for Neurohormones Detection—A Review. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 33749–33768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Qi, Q.; Li, B.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, J.; Liu, L. Recent Advances on Fluorescent Sensors for Detection of Pathogenic Bacteria. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Huang, F.; Huang, X.; Zhang, F.; Pei, D.; Zhang, J.; Hai, J. Recent Progress in Small Molecule Fluorescent Probes for Imaging and Diagnosis of Liver Injury. Targets 2025, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, J.V.; Chenoweth, D.M.; Petersson, E.J. Rational Design of Small Molecule Fluorescent Probes for Biological Applications. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 5747–5763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Tiwari, K.; Tiwari, R.; Pramanik, S.K.; Das, A. Small Molecules as Fluorescent Probes for Monitoring Intracellular Enzymatic Transformations. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 11718–11760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, Q.; Chen, W. Advancements in Small Molecule Fluorescent Probes for Superoxide Anion Detection: A Review. J. Fluoresc. 2025, 35, 2497–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Pan, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, H.; Liu, X. Advances in Small-Molecule Fluorescent Probes for the Study of Apoptosis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 9133–9189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Huang, Z.; Sui, C.; Xu, M.; Sun, X. Advances in Small-Molecule Fluorescent Probes for Cellular Senescence Diagnosis and Therapy: A Review. Dye. Pigment. 2024, 235, 112599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Qu, Y.; Tang, F.; Wang, H.; Ding, A.; Li, L. Advances in Small-Molecule Fluorescent pH Probes for Monitoring Mitophagy. Chem. Biomed. Imaging 2024, 2, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Finney, N.S. Small-Molecule Fluorescent Probes and Their Design. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 29051–29061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Liu, Z.; Verwilst, P.; Koo, S.; Jangjili, P.; Kim, J.S.; Lin, W. Coumarin-Based Small-Molecule Fluorescent Chemosensors. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 10403–10519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Liu, T.; Sun, J.; Wang, X. Synthesis and Application of Coumarin Fluorescence Probes. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 10826–10847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Indurthi, H.K.; Saha, P.; Sharma, D.K. Coumarin-Based Fluorescent Probes for the Detection of Ions, Biomolecules and Biochemical Species Responsible for Diseases. Dye. Pigment. 2024, 228, 112257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Jung, J.; Huh, Y.; Kim, D. Benzo[g]Coumarin-Based Fluorescent Probes for Bioimaging Applications. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2018, 2018, 5249765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Hou, J.; Wang, P.; Peng, X.; Ge, G. Coumarin-Based Near-Infrared Fluorogenic Probes: Recent Advances, Challenges and Future Perspectives. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 480, 215020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.A.; Kandathil, V.; Sobha, A.; Somappa, S.B.; Feldman, M.R.; Bugarin, A.; Patil, S.A. Comprehensive Review on Medicinal Applications of Coumarin-Derived Imine–Metal Complexes. Molecules 2022, 27, 5220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranđelović, S.; Bipat, R. A Review of Coumarins and Coumarin-Related Compounds for Their Potential Antidiabetic Effect. Clin. Med. Insights Endocrinol. Diabetes 2021, 14, 11795514211042023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şeker Karatoprak, G.; Dumlupınar, B.; Celep, E.; Kurt Celep, I.; Küpeli Akkol, E.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E. A Comprehensive Review on the Potential of Coumarin and Related Derivatives as Multi-Target Therapeutic Agents in the Management of Gynecological Cancers. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1423480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.K.; Khatoon, S.; Khan, M.F.; Akhtar, M.S.; Ahamad, S.; Saquib, M. Coumarins as Versatile Therapeutic Phytomolecules: A Systematic Review. Phytomedicine 2024, 134, 155972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koley, M.; Han, J.; Soloshonok, V.A.; Mojumder, S.; Javahershenas, R.; Makarem, A. Latest Developments in Coumarin-Based Anticancer Agents: Mechanism of Action and Structure–Activity Relationship Studies. RSC Med. Chem. 2023, 15, 10–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Kaushik, N.; Paliwal, A.; Sengar, M.S.; Paliwal, D. Biological Activity and Therapeutic Potential of Coumarin Derivatives: A Comprehensive Review. Curr. Drug Discov. Technol. 2025, 22, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsis, T.M.; Ebrahim, M.A.; Fayed, E.A. Synthetic Coumarin Derivatives with Anticoagulation and Antiplatelet Aggregation Inhibitory Effects. Med. Chem. Res. 2023, 32, 2269–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontogiorgis, C.; Detsi, A.; Hadjipavlou-Litina, D. Coumarin-Based Drugs: A Patent Review (2008–Present). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2012, 22, 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadati, F.; Chahardehi, A.M.; Jamshidi, N.; Jamshidi, N.; Ghasemi, D. Coumarin: A Natural Solution for Alleviating Inflammatory Disorders. Curr. Res. Pharmacol. Drug Discov. 2024, 7, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasperkiewicz, K.; Ponczek, M.B.; Owczarek, J.; Guga, P.; Budzisz, E. Antagonists of Vitamin K—Popular Coumarin Drugs and New Synthetic and Natural Coumarin Derivatives. Molecules 2020, 25, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Cruz-Martins, N.; López-Jornet, P.; Lopez, E.P.; Harun, N.; Yeskaliyeva, B.; Beyatli, A.; Sytar, O.; Shaheen, S.; Sharopov, F.; et al. Natural Coumarins: Exploring the Pharmacological Complexity and Underlying Molecular Mechanisms. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 6492346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, S.; Singh, R.; Sangwan, S. A Review on Convenient Synthesis of Substituted Coumarins Using Reusable Solid Acid Catalysts. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 29130–29155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoz, H.; Ali, R.; Khan, F.A.; Kakkar, P.; Soni, R.; Assiri, M.A.; Ahamad, S.; Saquib, M.; Hussain, M.K. Coumarins as Versatile Scaffolds: Innovative Synthetic Strategies for Generating Diverse Heterocyclic Libraries in Drug Discovery. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1352, 144426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhaoui, A.; Eddahmi, M.; Dib, M.; Khouili, M.; Aires, A.; Catto, M.; Bouissane, L. Synthesis and Biological Properties of Coumarin Derivatives: A Review. ChemistrySelect 2021, 6, 5848–5870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalpozzo, R.; Mancuso, R. Copper-Catalyzed Synthesis of Coumarins: A Mini-Review. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, W.; Talbi, S.; Hamri, S.; Hafid, A.; Khouili, M. Coumarin Derivatives: Microwave Synthesis and Biological Properties—A Review. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2024, 61, 2070–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchoupou, I.T.; Manyeruke, M.H.; Salami, S.A.; Ezekiel, C.I.; Ambassa, P.; Tembu, J.V.; Krause, R.W.; Ngameni, B.; Noundou, X.S. An Overview of the Synthesis of Coumarins via Knoevenagel Condensation and Their Biological Properties. Results Chem. 2025, 15, 102181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwaczko, K. Coumarins Synthesis and Transformation via C–H Bond Activation—A Review. Inorganics 2022, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, H.L.; Staeck, N.; Müller, P.; Bogdos, M.K.; Morandi, B. Intermolecular Synthesis of Coumarins from Acid Chlorides and Unactivated Alkynes Through Palladium Catalysis. Org. Lett. 2025, 27, 8869–8874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, J.; Yan, L.; Li, Y.; Zhao, N.; Liu, H.; Huang, H.; Zhou, Y. A Ru(II)-Catalyzed C–H Activation and Annulation Cascade for the Construction of Highly Coumarin-Fused Benzo[a]quinolizin-4-Ones and Pyridin-2-Ones. Org. Chem. Front. 2023, 10, 2680–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citarella, A.; Vittorio, S.; Dank, C.; Ielo, L. Syntheses, Reactivity, and Biological Applications of Coumarins. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1362992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, N.M.; Martelli, L.S.R.; Corrêa, A.G. Asymmetric Organocatalyzed Synthesis of Coumarin Derivatives. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2021, 17, 1952–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Docherty, J.H.; Lister, T.M.; McArthur, G.; Findlay, M.T.; Domingo-Legarda, P.; Kenyon, J.; Choudhary, S.; Larrosa, I. Transition-Metal-Catalyzed C–H Bond Activation for the Formation of C–C Bonds in Complex Molecules. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 7692–7760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkune, N.W.; Moloudi, K.; George, B.P.; Abrahamse, H. An Update on Recent Advances in Fluorescent Materials for Fluorescence Molecular Imaging: A Review. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 22267–22284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiya, S.; Martis, G.J.; Shetty, N.S.; Gaonkar, S.L. Organic Fluorescent Compounds: A Review of Synthetic Strategies and Emerging Applications. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, I.S.; Misra, R. Design, Synthesis and Functionalization of BODIPY Dyes: Applications in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells (DSSCs) and Photodynamic Therapy (PDT). J. Mater. Chem. C 2023, 11, 8688–8723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruna, N.; Verma, V.P.; Singh, A.P.; Shrivastava, R. Recent Advancement in Development of Fluorescein-Based Molecular Probes for Analytes Sensing. J. Mol. Struci. 2023, 1295, 136549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Tang, A.; Tan, S.; Wang, G.; Huang, H.; Niu, W.; Liu, S.; Ge, M.; Yang, L.; Gao, F.; et al. Recent Progress and Outlooks in Rhodamine-Based Fluorescent Probes for Detection and Imaging of Reactive Oxygen, Nitrogen, and Sulfur Species. Talanta 2024, 274, 126004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooshmand, S.E.; Baeiszadeh, B.; Mohammadnejad, M.; Ghasemi, R.; Darvishi, F.; Khatibi, A.; Shiri, M.; Hussain, F.H. Novel Probe Based on Rhodamine B and Quinoline as a Naked-Eye Colorimetric Probe for Dual Detection of Nickel and Hypochlorite Ions. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, L.; Li, H.; Ding, X.; Liu, Z.; He, D.; Kowah, J.A.H.; Wang, L.; Yuan, M.; Liu, X. A Review of the Application of Spectroscopy to Flavonoids from Medicine and Food Homology Materials. Molecules 2022, 27, 7766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachollet, S.P.J.T.; Addi, C.; Pietrancosta, N.; Mallet, J.; Dumat, B. Fluorogenic Protein Probes with Red and Near-Infrared Emission for Genetically Targeted Imaging. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 14467–14473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Dai, J.; Zhou, R.; Liu, G.; Liu, X.; Yan, X.; Liu, F.; Sun, P.; Wang, C.; Lu, G. Highly Efficient Red/NIR-Emissive Fluorescent Probe with Polarity-Sensitive Character for Visualizing Cellular Lipid Droplets and Determining Their Polarity. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 12095–12102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero Llopis, P.; Senft, R.A.; Ross-Elliott, T.J.; Stephansky, R.; Keeley, D.P.; Koshar, P.; Marqués, G.; Gao, Y.-S.; Carlson, B.R.; Pengo, T.; et al. Best Practices and Tools for Reporting Reproducible Fluorescence Microscopy Methods. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 1463–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmied, C.; Nelson, M.S.; Avilov, S.; Bakker, G.J.; Bertocchi, C.; Bischof, J.; Boehm, U.; Brocher, J.; Carvalho, M.T.; Chiritescu, C.; et al. Community-Developed Checklists for Publishing Images and Image Analyses. Nat. Methods 2024, 21, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Liu, J.; O’Connor, H.M.; Gunnlaugsson, T.; James, T.D.; Zhang, H. Photoinduced Electron Transfer (PeT) Based Fluorescent Probes for Cellular Imaging and Disease Therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 2332–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, L.; Guo, R.; Lin, W. A Coumarin-Based “Off–On” Fluorescent Probe for Highly Selective Detection of Hydrogen Sulfide and Imaging in Living Cells. Anal. Methods 2021, 13, 1511–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qiu, X.; Sun, L.; Yan, Q.; Luck, R.L.; Liu, H. A Two-Photon Fluorogenic Probe Based on a Coumarin Schiff Base for Formaldehyde Detection in Living Cells. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022, 274, 121074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Tian, X.; Gong, S.; Meng, Z.; Yang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S. A Novel Coumarin-Derived Fluorescent Probe for Real-Time Detection of pH in Living Zebrafish and Actual Food Samples. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1299, 137141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehra, N.; Kaushik, R. ESIPT-Based Probes for Cations, Anions and Neutral Species: Recent Progress, Multidisciplinary Applications and Future Perspectives. Anal. Methods 2023, 15, 5268–5285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajbanshi, M.; Mahato, M.; Maiti, A.; Ahmed, S.; Das, S.K. An ESIPT-Based Chromone–Coumarin Coupled Fluorogenic Dyad for Specific Recognition of Sarin Gas Surrogate, Diethylchlorophosphate. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2024, 447, 115230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, S.; Mukhopadhyay, S.K.; Gangopadhyay, M.; Biswas, S.; Dey, S.; Singh, N.D.P. Coumarin–Benzothiazole–Chlorambucil (Cou–Benz–Cbl) Conjugate: An ESIPT-Based pH-Sensitive Photoresponsive Drug Delivery System. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 3490–3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.; Kim, J.S.; Sessler, J.L. Small Molecule-Based Ratiometric Fluorescence Probes for Cations, Anions, and Biomolecules. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 4185–4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, D.; Shaily. Coumarin-Based Fluorescent Sensors. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2023, 37, e7138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, J. Optical Chemosensors Synthesis and Application for Trace Level Metal Ions Detection in Aqueous Media: A Review. J. Fluoresc. 2024, 35, 561–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeta, J.; Džijak, R.; Obořil, J.; Dračínský, M.; Vrabel, M. A Systematic Study of Coumarin–Tetrazine Light-Up Probes for Bioorthogonal Fluorescence Imaging. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 9945–9953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, Y.; Kwok, S.; Hayashi, Y. Application of FRET Probes in the Analysis of Neuronal Plasticity. Front. Neural Circuits 2013, 7, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu, M.; Yanai, K.; Shigeto, H.; Yamamura, S.; Watanabe, K.; Ohtsuki, T. FRET Probe for Detecting Two Mutations in One EGFR mRNA. Analyst 2023, 148, 2626–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabr, M.T.; Ibrahim, M.M.H.; Tripathi, A.; Prabhakar, C. A Coumarin-Benzothiazole Derivative as a FRET-Based Chemosensor of Adenosine 5′-Triphosphate. Chemosensors 2019, 7, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Sun, L.; Liu, X.; Pang, X.; Fan, F.; Yang, X.; Hua, R.; Wang, Y. A Reversible CHEF-Based NIR Fluorescent Probe for Sensing Hg2+ and Its Multiple Application in Environmental Media and Biological Systems. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 874, 162460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatun, M.; Ghorai, P.; Mandal, J.; Ghosh Chowdhury, S.; Karmakar, P.; Blasco, S.; García-España, E.; Saha, A. Aza-Phenol Based Macrocyclic Probes Design for “CHEF-on” Multi-Analytes Sensor: Crystal Structure Elucidation and Application in Biological Cell Imaging. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 7479–7491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nootem, U.; Daengngern, R.; Sattayanon, C.; Wattanathana, W.; Wannapaiboon, S.; Rashatasakhon, P.; Chansaenpak, K. The Synergy of CHEF and ICT toward Fluorescence ‘Turn-On’ Probes Based on Push–Pull Benzothiazoles for Selective Detection of Cu2+ in Acetonitrile/Water Mixture. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2021, 415, 113318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slassi, S.; Aarjane, M.; El-Ghayoury, A.; Amine, A. A Highly Turn-On Fluorescent CHEF-Type Chemosensor for Selective Detection of Cu2+ in Aqueous Media. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019, 215, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Wang, Q.; Dickie, D.; Pu, L. Mechanistic Study on a BINOL–Coumarin-Based Probe for Enantioselective Fluorescent Recognition of Amino Acids. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 6352–6358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushothaman, P.; Karpagam, S. Thiophene Derived Sky-Blue Fluorescent Probe for the Selective Recognition of Mercuric Ion through CHEQ Mechanism and Application in Real Time Samples. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 305, 123518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Xue, L.; Gao, Y.; Fu, S.; Wang, H. A Coumarin-Based Ratiometric Fluorescent Probe for the Detection of Cu2+ and Mechanochromism as well as Application in Living Cells and Vegetables. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 305, 123479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gothland, A.; Jary, A.; Grange, P.; Leducq, V.; Beauvais-Remigereau, L.; Dupin, N.; Marcelin, A.-G.; Calvez, V. Harnessing Redox Disruption to Treat Human Herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) Related Malignancies. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, L.B. The basics of thiols and cysteines in redox biology and chemistry. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 80, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyamira, M.M.; Héctor, R.R.; María Magdalena, V.L.; Héctor, V.M. Glutathione Participation in the Prevention of Cardiovascular Diseases. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfei, S.; Schito, G.C.; Schito, A.M.; Zuccari, G. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)-Mediated Antibacterial Oxidative Therapies: Available Methods to Generate ROS and a Novel Option Proposal. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerapana, E.; Wang, C.; Simon, G.M.; Richter, F.; Khare, S.; Dillon, M.B.D.; Bachovchin, D.A.; Mowen, K.; Baker, D.; Cravatt, B.F. Quantitative Reactivity Profiling Predicts Functional Cysteines in Proteomes. Nature 2010, 468, 790–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annamaria, F.; Edgar, D.; Yoboue, E.D.; Roberto, S. Cysteines as Redox Molecular Switches and Targets of Disease. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, P.Y.; Liu, M.Y. Amino Acid Cysteine Induces Senescence and Decelerates Cell Growth in Melanoma. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 18, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, S.A.; Choi, Y.B.; Takahashi, H.; Zhang, D.; Li, W.; Godzik, A.; Bankston, L.A. Cysteine Regulation of Protein Function—As Exemplified by NMDA-Receptor Modulation. Trends Neurosci. 2002, 25, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Banaclocha, M.A. N-Acetyl-Cysteine in the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. What Are We Waiting For? Med. Hypotheses 2012, 79, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Banaclocha, M.A. Targeting the Cysteine Redox Proteome in Parkinson’s Disease: The Role of Glutathione Precursors and Beyond. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adil, M.; Amin, S.S.; Mohtashim, M. N-Acetylcysteine in Dermatology. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2018, 84, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatami, B.; Abdi, S.; Pourhoseingholi, M.A.; Eghlimi, H.; Rabbani, A.H.; Masoumi, M.; Hajimohammadebrahim-Ketabforoush, M. The Effects of N-Acetylcysteine on Hepatic, Hematologic, and Renal Parameters in Cirrhotic Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2023, 16, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.D.; Refsum, H.; Bottiglieri, T.; Fenech, M.; Hooshmand, B.; McCaddon, A.; Miller, J.W.; Rosenberg, I.H.; Obeid, R. Homocysteine and Dementia: An International Consensus Statement. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 62, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, S.S.; Al-Khlaiwi, T.; Almusahwah, A.; Alsomali, A.; Habib, S.A. Homocysteine as a Predictor and Prognostic Marker of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 8598–8608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaddon, A.; Miller, J.W. Homocysteine—A Retrospective and Prospective Appraisal. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1179807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandhya, G.; Monisha, S.; Singh, S.; Stezin, A.; Diwakar, L.; Issac, T.G. Hyperhomocysteinemia and Its Effect on Ageing and Language Functions—HEAL Study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marroncini, G.; Martinelli, S.; Menchetti, S.; Bombardiere, F.; Martelli, F.S. Hyperhomocysteinemia and Disease—Is 10 μmol/L a Suitable New Threshold Limit? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoyama, K.; Kinoshita, C.; Nakaki, T. Disorders of Glutathione Metabolism. In Rosenberg’s Molecular and Genetic Basis of Neurological and Psychiatric Disease, 7th ed.; Rosenberg, R.N., Pascual, J.M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; pp. 847–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotgia, S.; Fois, A.G.; Paliogiannis, P.; Carru, C.; Mangoni, A.A.; Zinellu, A. Methodological Fallacies in the Determination of Serum/Plasma Glutathione Limit Its Translational Potential in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Molecules 2021, 26, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnasser, S.M. The Role of Glutathione S-Transferases in Human Disease Pathogenesis and Their Current Inhibitors. Genes Dis. 2024, 12, 101482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, S.; Shi, Y.; Lin, F.; Rui, L.; Shi, J.; Sun, K. Glutathione: A Key Regulator of Extracellular Matrix and Cell Death in Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Mediat. Inflamm. 2024, 2024, 4482642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szwaczko, K. Fluorescent coumarin-based probe for detection of biological thiols. Curr. Org. Chem. 2023, 27, 1329–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Chen, W.; Cheng, Y.; Hakuna, L.; Strongin, R.; Wang, B. Thiol Reactive Probes and Chemosensors. Sensors 2012, 12, 15907–15946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Huang, Y.; Guan, X. Fluorescent Probes for Live Cell Thiol Detection. Molecules 2021, 26, 3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Peng, X.; Yoon, J. Fluorescent and Colorimetric Probes for Detection of Thiols. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 2120–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Lv, X.; Hao, J. A Fluorescent Probe Capable of Naked Eye Recognition for the Selective Detection of Biothiols. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2022, 425, 113654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Huo, F.; Yin, C. The Chronological Evolution of Small Organic Molecular Fluorescent Probes for Thiols. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 1220–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Yin, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, M.; Chen, S. Recent Progress in the Development of Fluorescent Probes for Thiophenol. Molecules 2019, 24, 3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonikov, A. Endogenous Deficiency of Glutathione as the Most Likely Cause of Serious Manifestations and Death in COVID-19 Patients. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020, 6, 1558–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.-Y.; Chen, Y.-Z.; Zheng, H.-R.; Wu, L.-Z.; Tung, C.-H.; Yang, Q.-Z. Design Strategies of Fluorescent Probes for Selective Detection among Biothiols. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 6143–6160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Jiang, J.; Shu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhang, K. Recent Progress in the Rational Design of Biothiol-Responsive Fluorescent Probes. Molecules 2023, 28, 4252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Peng, H.; Wang, B. Recent Advances in Thiol and Sulfide Reactive Probes. J. Cell. Biochem. 2014, 115, 1007–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Ma, D. A Ratiometric Fluorescent Probe for the Detection of Biological Thiols Based on a New Supramolecular Design. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 303, 123167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickraman, I.; Yhobu, Z.; Małecki, J.G.; Ganapathy, K.; Nagaraja, A.T.; Budagumpi, S. Bioorthogonal Chemistry of Water-Soluble Blue Fluorescent Coumarin-Substituted Azole Derivatives for Bioimaging and Bioconjugation Applications. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2025, 8, 5552–5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pervez, W.; Laraib; Yin, C.; Huo, F. Homocysteine Fluorescent Probes: Sensing Mechanisms and Biological Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 522, 216202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Lin, Y.; Wang, J.; Ye, T.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Guo, L.; Li, L.; Qian, Z.; Liu, H. Near-infrared mitochondria-targeted fluorescent probe with a large Stokes shift for rapid and sensitive detection of cysteine/homocysteine and its bioimaging application. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2023, 374, 132799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Feng, S.; Song, X.; Zheng, Q.; Feng, G.; Song, A. A benzotriazole-coumarin derivative as a turn-on fluorescent probe for highly efficient and selective detection of homocysteine and its bioimaging application. Microchem. J. 2023, 185, 108293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, I.; Su, J.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, K.; Yuan, L.; Qin, F.; Niu, H.; Ye, Y. A Responsive Aggregation-Induced Emission Fluorescent Probe for the Detection of Cysteine in Food, Serum Samples and Oxidative Stress Environments. Microchem. J. 2024, 206, 111671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Gong, X.-L.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, X.; Peng, Y.; Wang, Y.-W. Coumarin-Based Fluorescence Probe for Differentiated Detection of Biothiols and Its Bioimaging in Cells. Biosensors 2023, 13, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Song, Z.; Guo, X.; Chu, Y.; Yi, L.; Hao, Y. A Highly Selective Ratiometric Fluorescent Probe for Cysteine Detection. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1335, 142031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, D.; Wang, X.; Luo, D.; Meng, S.; Zhou, L.; Fan, Y.; Ling-hu, C.; Meng, J.; Si, W.; Chen, Q.; et al. A Simple ESIPT Combines AIE Character “Turn-On” Fluorescent Probe for Hcy/Cys/GSH Detection and Cell Imaging Based on Coumarin Unit. Dye. Pigment. 2023, 208, 110762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Ming, Y.; Kong, F.; Liu, F.; Shao, C.; Bian, Y. Dual channel fluorescent probe for revealing the fluctuation of cysteine levels and viscosity in cancer cells during erastin-induced ferroptosis. Bioorg. Chem. 2025, 164, 108865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cao, F.; Yin, H.L.; Huang, Z.J.; Lin, Z.T.; Mao, N.; Sun, B.; Wang, G. Ferroptosis: Past, Present and Future. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Wang, J.; Bian, Y.; Shao, C. D-A-D Type Based NIR Fluorescence Probe for Monitoring the Cysteine Levels in Pancreatic Cancer Cell During Ferroptosis. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 146, 107260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Kong, F.; Zhang, D.; Yuan, X.H.; Bian, Y.; Shao, C. Dual-Locked NIR Fluorescent Probe for Detection of GSH and Lipid Droplets and Its Bioimaging Application in a Cancer Model. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 327, 125395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, L.; Yang, G.; Xin, H.; Huang, Y.; Li, K.; Liu, J.; Pang, J.; Cao, D. Coumarin–Aurone Based Fluorescence Probes for Cysteine Sensitive In-Situ Identification in Living Cells. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2024, 244, 114173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Wei, Y.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, C.; Wang, Q. A Novel Coumarin–Thiazole Conjugated ICT Fluorescent Probe for Cysteine-Specific Detection in Food Samples, Living Cells and Zebrafish. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 2025, 53, 100542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Li, Y.; Shang, J.; Li, H. A Multi-Responsive Coumarin–Benzothiazole Fluorescent Probe for Selective Detection of Biological Thiols and Hydrazine. J. Anal. Sci. Technol. 2021, 12, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Gan, Y.; Long, Z.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Yin, P.; Yao, S. Multifunctional Fluorescent Probe for Simultaneous Detection of ATP, Cys, Hcy, and GSH: Advancing Insights into Epilepsy and Liver Injury. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2415882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Xi, D.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, X.; Xu, K.; Liu, H.; Fang, M. Precision Imaging of Biothiols in Live Cells and Treatment Evaluation During the Development of Liver Injury via a Near-Infrared Fluorescent Probe. Chem. Biomed. Imaging 2025, 3, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valverde-Santiago, M.; Pontel, L.B. Emerging Mechanisms Underlying Formaldehyde Toxicity and Response. Cell 2025, 85, 2068–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, B.; Faquin, W. The Heavy Health Costs of a Chemical “That’s Too Big to Fail”: Despite Longstanding Ties Linking Formaldehyde to Cancer and Other Diseases, Lessening the Danger of the Ubiquitous Chemical Remains a Hard Lift. Cancer Cytopathol. 2025, 133, e70053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santonocito, R.; Pappalardo, A.; Tuccitto, N.; Cavallaro, A.; Trusso Sfrazzetto, G. Formaldehyde Sensing by Fluorescent Organic Sensors. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2025, 23, 8592–8608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.J.; Liu, W.C.; Lu, F.N.; Tang, Y.; Yuan, Z.Q. Recent Progress in Fluorescent Formaldehyde Detection Using Small Molecule Probes. J. Anal. Test. 2022, 6, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Rayyan, A.; Ahmad, I.; Bahtiti, N.H.; Muhmood, T.; Bondock, S.; Abohashrh, M.; Faheem, H.; Tehreem, N.; Yasmeen, A.; Waseem, S.; et al. Recent Progress in the Development of Organic Chemosensors for Formaldehyde Detection. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 14859–14872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, A.; Yang, S.; Liu, M.; Wang, X.; Liao, W.; Zeng, W. Fluorescent Probes and Materials for Detecting Formaldehyde: From Laboratory to Indoor for Environmental and Health Monitoring. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 36421–36432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fappiano, L.; Carriera, F.; Iannone, A.; Notardonato, I.; Avino, P. A Review on Recent Sensing Methods for Determining Formaldehyde in Agri-Food Chain: A Comparison with the Conventional Analytical Approaches. Foods 2022, 11, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Pan, S.; De, P. Recent Progress on Polymeric Probes for Formaldehyde Sensing: A Comprehensive Review. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2024, 25, 2423597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, A.; Li, H.; Anorma, C.; Chan, J. A Reaction-Based Fluorescent Probe for Imaging Formaldehyde in Living Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 10890–10893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, T.F.; Burgos-Barragan, G.; Wit, N.; Patel, K.J.; Chang, C.J. A 2-Aza-Cope Reactivity-Based Platform for Ratiometric Fluorescence Imaging of Formaldehyde in Living Cells. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 4073–4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; He, X.; Cui, J.; Liu, T.; Tian, Z.; He, S. A Coumarin-Based Fluorescent Probe for Rapid Detection of Endogenous Formaldehyde. Chin. J. Appl. Chem. 2019, 36, 1053–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.G.; Chen, B.; Shao, L.X.; Cheng, J.; Huang, M.Z.; Chen, Y.; Hu, Y.Z.; Han, Y.F.; Han, F.; Li, X. A Fluorogenic Probe for Ultrafast and Reversible Detection of Formaldehyde in Neurovascular Tissues. Theranostics 2017, 7, 2305–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.; Tang, F.; Shangguan, X.; Che, S.; Niu, J.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, X.; Tang, B. Two-Photon Imaging of Formaldehyde in Live Cells and Animals Utilizing a Lysosome-Targetable and Acidic pH-Activatable Fluorescent Probe. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 6520–6523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, T.; Liu, C.; Wang, K.; Rong, X.; Liu, X.; Yan, T.; Cai, X.; Sheng, W.; Zhu, B. A Novel Regenerated Fluorescent Probe for Formaldehyde Detection in Food Samples and Zebrafish. Microchem. J. 2024, 205, 111223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, T.F.; Chang, C.J. An Aza-Cope Reactivity-Based Fluorescent Probe for Imaging Formaldehyde in Living Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 10886–10889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruemmer, K.J.; Walvoord, R.R.; Brewer, T.F.; Burgos-Barragan, G.; Wit, N.; Pontel, L.B.; Patel, K.J.; Chang, C.J. Development of a General Aza-Cope Reaction Trigger Applied to Fluorescence Imaging of Formaldehyde in Living Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 5338–5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantó, C.; Menzies, K.; Auwerx, J. NAD⁺ Metabolism and the Control of Energy Homeostasis: A Balancing Act Between Mitochondria and the Nucleus. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, W. NAD⁺/NADH and NADP⁺/NADPH in Cellular Functions and Cell Death: Regulation and Biological Consequences. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2008, 10, 179–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, W.M.; Seeds, W.A.; Mattson, M.P.; Bradshaw, P.C. NADPH and Mitochondrial Quality Control as Targets for a Circadian-Based Fasting and Exercise Therapy for the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Cells 2022, 11, 2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, H.Q.; Lin, J.F.; Tian, T.; Xie, D.; Xu, R.H. NADPH Homeostasis in Cancer: Functions, Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassan, M.; Choi, S.K.; Galán, M.; Lee, Y.H.; Trebak, M.; Matrougui, K. Enhanced p22phox Expression Impairs Vascular Function through p38 and ERK1/2 MAP Kinase-Dependent Mechanisms in Type 2 Diabetic Mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2014, 306, H972–H980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorce, S.; Stocker, R.; Seredenina, T.; Holmdahl, R.; Aguzzi, A.; Chio, A.; Depaulis, A.; Heitz, F.; Olofsson, P.; Olsson, T.; et al. NADPH Oxidases as Drug Targets and Biomarkers in Neurodegenerative Diseases: What Is the Evidence? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 112, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Y.; Liu, J. The Recent Development of Fluorescent Probes for the Detection of NADH and NADPH in Living Cells and In Vivo. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 245, 118919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

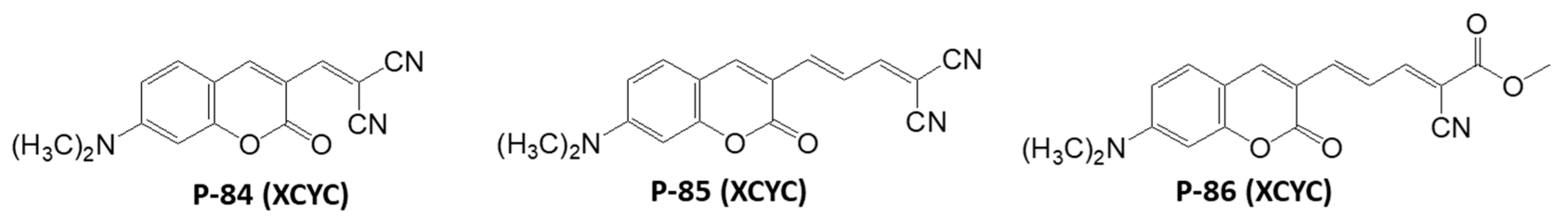

- Olowolagba, A.M.; Idowu, M.O.; Arachchige, D.L.; Aworinde, O.R.; Dwivedi, S.K.; Graham, O.R.; Werner, T.; Luck, R.L.; Liu, H. Syntheses and Applications of Coumarin-Derived Fluorescent Probes for Real-Time Monitoring of NAD(P)H Dynamics in Living Cells across Diverse Chemical Environments. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 5437–5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.-Q.; Xin, H.; Zhu, Y.-Z. Hydrogen Sulfide: Third Gaseous Transmitter, but with Great Pharmacological Potential. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2007, 28, 1709–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.-Q.; Yuan, H.; Liu, Y.-F.; Zhu, Y.-W.; Wang, Y.; Liang, X.-Y.; Gao, W.; Ren, Z.-G.; Ji, X.-Y.; Wu, D.-D. Role of Hydrogen Sulfide in Health and Disease. MedComm 2024, 5, e661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piragine, E.; Malanima, M.A.; Lucenteforte, E.; Martelli, A.; Calderone, V. Circulating Levels of Hydrogen Sulfide (H2S) in Patients with Age-Related Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, H.M.; Pluth, M.D. Advances and Opportunities in H2S Measurement in Chemical Biology. JACS Au 2023, 3, 2677–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duc, C.; Boukhenane, M.-L.; Wojkiewicz, J.-L.; Redon, N. Hydrogen Sulfide Detection by Sensors Based on Conductive Polymers: A Review. Front. Mater. 2020, 7, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjana, M.; Kulkarni, R.M.; Sunil, D. Small Molecule Optical Probes for Detection of H2S in Water Samples: A Review. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 14672–14691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, K.; Luo, C.; Xie, M.; Shi, X.; Lin, X. Review of Chemical Sensors for Hydrogen Sulfide Detection in Organisms and Living Cells. Sensors 2023, 23, 3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Iqbal, S.; Khan, A.; Fatima, F.; Mahar, H.; Bhutto, R.A. Advances in Fluorescent Probes for Hydrogen Sulfide Detection: Applications in Food Safety, Environmental Monitoring, and Biological Systems. Microchem. J. 2025, 215, 114188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Mazur, F.; Liang, K.; Chandrawati, R. Sensitivity and Selectivity Analysis of Fluorescent Probes for Hydrogen Sulfide Detection. Chem. Asian J. 2022, 17, e202101399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, M.; Wang, Y.; Du, C.; Shieh, M. Activity-Based Fluorescent Probes for Reactive Sulfur Species. Acc. Chem. Res. 2025, 58, 2804–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.; Gu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Tang, Y.; Guo, R.; Lin, W. Development of a New Hydrogen Sulfide Fluorescent Probe Based on Coumarin–Chalcone Fluorescence Platform and Its Imaging Application. Chemosensors 2023, 11, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Mi, L.; Dong, S.; Yang, H.; Xu, S. Construction of a Coumarin-Based Fluorescent Probe for Accurately Visualizing Hydrogen Sulfide in Live Cells and Zebrafish. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 16327–16334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xun, Y.; Nan, G.; Ahn, D.-H.; Jindong, D.; Zhu, D.; Chengchen, L.; Ming, Z.; Bo, H.; Kangkang, J.; Song, J.-W.; et al. A Coumarin-Based Fluorescent Probe for Imaging H2S and Distinguishing Breast Cancer Cells from Normal Ones. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 414, 126158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sontisiri, P.; Promrug, D.; Arthan, D.; Choengchan, N.; Thongyoo, P. A New Coumarin-Based “OFF–ON” Fluorescent Sensor for H2S Detection in HeLa Cells. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 326, 125170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Q.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, D.; Chen, X.; Du, F.; Zhou, Z.; Fu, C.; Li, L.; Yang, N.; Yu, C. A Novel Coumarin–Fluorescein-Based Fluorescent Probe for Ultrafast and Visual Detection of H2S in a Parkinson’s Disease Model. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 306, 123567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Bao, J.; Pan, X.; Chen, Q.; Yan, J.; Yang, G.; Khan, B.; Zhang, K.; Han, X. A Near-Infrared Fluorescent Probe with Large Stokes Shift for Sensitive Detection of Hydrogen Sulfide in Environmental Water, Food Spoilage, and Biological Systems. J. Phys. Chem. B 2024, 128, 5846–5854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, W.; Kwak, H.; Cheong, E.; Lee, C.J. GABA Tone Regulation and Its Cognitive Functions in the Brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2023, 24, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.Y.; Wong, A.H.C. GABAergic Inhibitory Neurons as Therapeutic Targets for Cognitive Impairment in Schizophrenia. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2018, 39, 733–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calì, C.; Wawrzyniak, M.; Becker, C.; Maco, B.; Cantoni, M.; Jorstad, A.; Nigro, B.; Grillo, F.; De Paola, V.; Fua, P.; et al. The effects of aging on neuropil structure in mouse somatosensory cortex—A 3D electron microscopy analysis of layer 1. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, P.C.; Pereira, D.B.; Borgkvist, A.; Wong, M.Y.; Barnard, C.; Sonders, M.S.; Zhang, H.; Sames, D.; Sulzer, D. Fluorescent dopamine tracer resolves individual dopaminergic synapses and their activity in the brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 870–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demailly, A.; Moreau, C.; Devos, D. Effectiveness of Continuous Dopaminergic Therapies in Parkinson’s Disease: A Review of L-DOPA Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics. J. Park. Dis. 2024, 14, 925–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.R.; Thokchom, B.; Abbigeri, M.B.; Bhavi, S.M.; Singh, S.R.; Metri, N.; Yarajarla, R.B. The Role of L-DOPA in Neurological and Neurodegenerative Complications: A Review. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2025, 480, 5221–5242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teleanu, R.I.; Niculescu, A.-G.; Roza, E.; Vladâcenco, O.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Teleanu, D.M. Neurotransmitters—Key Factors in Neurological and Neurodegenerative Disorders of the Central Nervous System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Yadav, P.; Liu, X.; Gillis, K.D.; Glass, T.E. Fluorescent Sensor for the Visualization of Amino Acid Neurotransmitters in Neurons Based on an SNAr Reaction. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2025, 16, 1238–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbhijnaKrishna, R.; Lu, Y.-H.; Wu, S.-P.; Velmathi, S. Comparative Study of Fluorophores for Precise Dopamine Detection and Investigation of Its Association with Stress and Coffee Addiction in HEK 293 Cells. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2025, 8, 5580–5591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, P.S.; Kisby, G.E. Role of Hydrazine-Related Chemicals in Cancer and Neurodegenerative Disease. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2021, 34, 1953–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garthwaite, J. NO as a Multimodal Transmitter in the Brain: Discovery and Current Status. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Tang, C.; Du, J.; Jin, H. Endogenous Sulfur Dioxide: A New Member of the Gasotransmitter Family in the Cardiovascular System. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 8961951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, W.K. Genetics of Monoamine Neurotransmitter Disorders. Transl. Pediatr. 2015, 4, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.; Li, X.; Yu, Z.; Zheng, X.; Ren, H.; Wu, J.; Lv, C.; Wang, P.; Liu, W. Coumarin Bialdehyde-Based Fluorescent Probe for the Detection of Hydrazine in Living Cells, Soil Samples and Its Application in Test Strips. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 343, 126540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, W.; Bu, Y.; Huang, H.; Wang, J.; Ren, M.; Deng, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, S.; Yu, Z.-P.; Zhou, H. Bifunctional Single-Molecular Fluorescent Probe: Visual Detection of Mitochondrial SO2 and Membrane Potential. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 6287–6294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Luo, Y.; Jin, S.; Xu, T.; Liang, Y.; Meng, Z.; Xu, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z. Rational Design of a Novel Dual-Functional Fluorescent Probe for Simultaneous Monitoring and Imaging of Mitochondrial CO and ATP Fluctuations during Drug-Induced Liver Injury without Spectral Crosstalk. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 21558–21571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AbhijnaKrishna, R.; Lu, Y.-H.; Wu, S.-P.; Velmathi, S. Sensitive Detection of Sulfur Mustard Poisoning via N-Salicylaldehyde Naphthyl Thiourea Probe and Investigation into Detoxification Scavengers. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 8341–8350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.V.; Kumar, V.; Biswas, U.; Boopathi, M.; Ganesan, K.; Gupta, A.K. Luminol-Based Turn-On Fluorescent Sensor for Selective and Sensitive Detection of Sulfur Mustard at Ambient Temperature. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 1193–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuo, W.; Bouquet, J.; Taran, F.; Le Gall, T. A FRET Probe for the Detection of Alkylating Agents. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 8655–8658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, L.; Chen, X.; Sun, M.; Xu, Q.; Cao, Y.; Xiao, K.; Li, Z. Visualization of Sulfur Mustard in Living Cells and Whole Animals with a Selective and Sensitive Turn-On Fluorescent Probe. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 296, 126678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Sun, M.; Xu, Q.; Cen, J.; Cao, Y.; Li, Z.; Xiao, K. Development of a Series of Fluorescent Probes for the Early Diagnostic Imaging of Sulfur Mustard Poisoning. ACS Sens. 2019, 4, 2794–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, B.; Chang, C. Chemistry and Biology of Reactive Oxygen Species in Signaling or Stress Responses. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heemels, M.T. Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nature 2016, 539, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandimali, N.; Bak, S.G.; Park, E.H.; Lim, H.J.; Won, Y.S.; Kim, E.K.; Park, S.-I.; Lee, S.J. Free Radicals and Their Impact on Health and Antioxidant Defenses: A Review. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, R.T.; Rhodes, C.J. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Metabolic Disease—Don’t Shoot the Metabolic Messenger. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, S.; Abdul Manap, A.S.; Attiq, A.; Albokhadaim, I.; Kandeel, M.; Alhojaily, S.M. From Imbalance to Impairment: The Central Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Oxidative Stress-Induced Disorders and Therapeutic Exploration. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1269581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Averill-Bates, D. Reactive Oxygen Species and Cell Signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2024, 1871, 119573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, M.C.; Andriantsitohaina, R. Reactive Nitrogen Species: Molecular Mechanisms and Potential Significance in Health and Disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 669–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumilaar, S.G.; Hardianto, A.; Dohi, H.; Kurnia, D. A Comprehensive Review of Free Radicals, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants: Overview, Clinical Applications, Global Perspectives, Future Directions, and Mechanisms of Antioxidant Activity of Flavonoid Compounds. J. Chem. 2024, 2024, 5594386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duanghathaipornsuk, S.; Farrell, E.J.; Alba-Rubio, A.C.; Zelenay, P.; Kim, D.-S. Detection Technologies for Reactive Oxygen Species: Fluorescence and Electrochemical Methods and Their Applications. Biosensors 2021, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Ye, C.; Lin, Z.; Huang, L.; Li, D. Recent Progress of Near-Infrared Fluorescent Probes in the Determination of Reactive Oxygen Species for Disease Diagnosis. Talanta 2024, 268, 125264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Zhu, M.; Liu, J.; James, T.D. Recent Progress in the Development of Fluorescent Probes for Imaging Pathological Oxidative Stress. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 3873–3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P.; Bayir, H.; Belousov, V.; Chang, C.J.; Davies, K.J.; Davies, M.J.; Dick, T.P.; Finkel, T.; Forman, H.J.; Janssen-Heininger, Y.; et al. Guidelines for Measuring Reactive Oxygen Species and Oxidative Damage in Cells and In Vivo. Nat. Metab. 2022, 4, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Jiang, M.; Sheng, J.; Li, K.; Dong, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, S. Engineering Dual-Mode-Responsive Probes for Real-Time HClO Monitoring in Drug-Induced Liver Injury. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 17521–17528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.H.; Xing, H.Y.; Meng, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Xiao, Q.; Li, N.B.; Xue, P.; Luo, H.Q. Engineering HClO Ratiometric Fluorescent Probe by Inducing Molecular Aggregation to Suppress TICT Formation for Monitoring Drug-Induced Liver Injury. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Deng, Y.; Yin, P.; Yao, S. Imaging of HClO, H2O2, and Their Mixture in Diabetic Models. Chem. Biomed. Imaging 2025, 3, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.; Fang, M.; Chen, M.; Wang, C.; Xu, X.; Wang, Q.; Feng, Y.; Meng, X. Dual-Color Visualization of Hepatic Fibrosis and Multidimensional Assessment of Therapeutic Drugs by a Multifunctional Single-Molecular Fluorescent Probe. ACS Sens. 2025, 10, 3569–3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Peng, W.; Zheng, H.; Chen, K.; Lin, Q.; Zhang, S.; Yang, L. Assessing Atherosclerosis by Super-Resolution Imaging of HClO in Foam Cells Using a Ratiometric Fluorescent Probe. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 14215–14221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.-Y.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Y.-H.; Han, D.; Yang, H.-K.; Lin, J.-T.; Xia, H.-C. Coumarin-Based Fluorescent Probe for Hypochlorite Detection and Imaging of Acute Kidney Injury. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 435, 137645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, J.; Chen, W.; Liu, Q.; Sheng, J.; Zhang, S.; Yang, L. Side-Chain-Fixed Homoadamantane-Fused Tetrahydroquinoxaline Coumarin: A Robust Platform for Highly Photostable HClO Probe Development. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 436, 137705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ren, L.; Gao, T.; Chen, T.; Han, J.; Wang, Y. A Coumarin-Based Fluorescent Probe for Sensitive Monitoring of H2O2 in Water and Living Cells. Tetrahedron Lett. 2023, 114, 154291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Yu, S.; Liu, Z.; Ma, M.; Chen, J. A Simple and Sensitive Coumarin-Based Fluorescence Probe (ZXD-1) for Determination of Hydrogen Peroxide and Its Application in Bioimaging. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1299, 137124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, R.; Ren, F.; Yang, S.; Shao, A. Coumarin-Conjugated Macromolecular Probe for Sequential Stimuli-Mediated Activation. Bioconjug. Chem. 2024, 35, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doctorovich, F.; Bikiel, D.E.; Pellegrino, J.; Suárez, S.A.; Martí, M.A. Reactions of HNO with Metal Porphyrins: Underscoring the Biological Relevance of HNO. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 2907–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, J.C.; Ritchie, R.H.; Favaloro, J.L.; Andrews, K.L.; Widdop, R.E.; Kemp-Harper, B.K. Nitroxyl (HNO): The Cinderella of the Nitric Oxide Story. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2008, 29, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuto, J.M.; Cisneros, C.J.; Kinkade, R.L. A Comparison of the Chemistry Associated with the Biological Signaling and Actions of Nitroxyl (HNO) and Nitric Oxide (NO). J. Inorg. Biochem. 2013, 118, 201–208, (PMC). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Xu, T.; Du, W.; Liang, Y.; Gong, S.; Meng, Z.; Xu, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z. A Highly Efficient Coumarin-Based Turn-On Fluorescent Probe for Specific and Sensitive Detection of Exogenous and Endogenous Nitroxyl in Vivo and in Vitro. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1319, 139412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Yang, Q.; Zan, Q.; Zhao, K.; Lu, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Shuang, S.; Dong, C. Multifunctional fluorescent probe for simultaneous detection of ONOO−, viscosity, and polarity and its application in ferroptosis and cancer models. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 5780–5787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Huang, H.; Li, M.; Fan, J.; Sun, W.; Du, J.; Long, S.; Peng, X. A Tumor-Specific Platform of Peroxynitrite Triggering Ferroptosis of Cancer Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2208105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lai, H.-J.; Wu, W.-N.; Zhao, X.-L.; Fan, Y.-C.; Bian, L.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.-H.; James, T.D.; Bian, Y. A Bifunctional Coumarin/Phenanthridine-Fused Probe for the Detection of Mitochondrial Peroxynitrite in Live Cells, Arabidopsis thaliana, Zebrafish, and Mice. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 442, 138066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.-M.; Lai, H.-J.; Wu, W.-N.; Zhao, X.-L.; Wang, Y.-C.; Xu, Z.-H.; James, T.D.; Bian, Y. A Coumarin-Based Probe with Far-Red Emission for the Ratiometric Detection of Peroxynitrite in the Mitochondria of Living Cells and Mice. Talanta 2024, 284, 127272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Corrales, M.; Rovira, A.; Gandioso, A.; Bosch, M.; Nonell, S.; Marchán, V. Transformation of COUPY Fluorophores into a Novel Class of Visible-Light-Cleavable Photolabile Protecting Groups. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 16222–16227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Peng, S.; Tang, J.; Zhang, D.; Ye, Y. ONOO− Activatable Fluorescent Sulfur Dioxide Donor for a More Accurate Assessment of Cell Ferroptosis. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 2041–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Zheng, S.; Liu, Q.; Dong, C.; Dong, B.; Fan, C.; Lu, Z.; Yoon, J. Screening Drug-Induced Liver Injury Through Two Independent Parameters of Lipid Droplets and Peroxynitrite with a π-Extended Coumarin-Based NIR Fluorescent Probe. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2024, 410, 135659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, S.-S.; Wang, Z.-Q.; Mi, J.-F.; Mao, G.-J.; Ouyang, J.; Hu, L.; Li, C.-Y. A Novel Colon-Targeting Ratiometric Probe with Large Emission Shift for Imaging Peroxynitrite in Ulcerative Colitis. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 18852–18858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Acha, N.; Elosúa, C.; Corres, J.M.; Arregui, F.J. Fluorescent Sensors for the Detection of Heavy Metal Ions in Aqueous Media. Sensors 2019, 19, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, L.; Yan, F.; Chen, G.; Huang, Y.; Huang, L.; Li, D. Recent Progress on Fluorescent Probes in Heavy Metal Determinations for Food Safety: A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 5689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, X.; An, J.; Dai, J.; Ying, Y.; Li, R.; Wang, W.; Liu, L.; Wu, H. Chalcogen-Based Fluorescent Probes for Metal Ion Detection: Principles, Applications, and Design Strategies. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 513, 215896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamei, M.; Achumi, A.G.; Puzari, A. A Sensitive Fluorescence Probe for the Trace Detection of Fe(III) Based on a Post-Synthesis-Modified Copper-Based Metal–Organic Framework. Chem. Select 2023, 8, e202301525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, J.; Xu, S.; Dong, B. Recent Progress in Fluorescent Probes for Metal Ion Detection. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 875241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eapen, A.K.; Das, D.; Sutradhkar, S.; Sarkar, P.; Ghosh, B.N. Recent Development in Coumarin-Based Cyanide Sensors. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1337, 142188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Feng, W.; Zhang, H.; Feng, G. An aza-coumarin-hemicyanine based nearinfrared fluorescent probe for rapid, colorimetric and ratiometric detection of bisulfite in food and living cells. Sens. Actuators B 2017, 243, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, E.; Sacco, C.; Moore, G.; DiNardi, S. Sulfite Oxidase Deficiency: A High Risk Factor in SO2, Sulfite, and Bisulfite Toxicity? Med. Hypotheses 1981, 7, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zheng, K.; Wang, J.; Yue, W.; Wang, H.; Lun, S.; Jing, Y.; Liang, Y.; Cui, X.; Jiang, Y. A Multifunctional Fluorescence Probe for HSO3−/SO32− and Viscosity in Real Samples and Living Cells. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2026, 348, 127100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xu, J.; Shan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, C.; Ding, G. A Ratiometric Fluorescent Probe with Favorable Water Solubility Based on a Coumarin Unit for Ultrafast Detection of SO2 Derivatives (SO32−/HSO3−) and Its Bioimaging. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1338, 142268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Z.-Y.; Mao, P.-D.; Jin, K.-S.; Wu, W.-N.; Bian, L.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Fan, Y.-C.; Xu, Z.-H.; James, T.D. A Dual-Responsive Golgi-Targeting Probe for the Simultaneous Fluorescence Detection of SO2 and Viscosity in Food Specimens and Live Cells. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 441, 137933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yuan, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, H.; Xu, K. A Coumarin-Based Near-Infrared Fluorescent Probe for the Detection of Hydrogen Sulfide/Sulfur Dioxide and Mitochondrial Viscosity. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2024, 418, 136243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Fang, X.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Qian, J. Coumarin-Based Fluorescent Probes for Colorimetric and Ratiometric Fluorescent Detection of Sulfite: Structure–Activity Relationship. Tetrahedron 2024, 159, 134017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H.; Hardy, J.; Blennow, K.; Chen, C.; Perry, G.; Kim, S.H.; Villemagne, V.L.; Aisen, K.; Vendruscolo, M.; Iwatsubo, T.; et al. The Amyloid-β Pathway in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 5481–5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliyasu, M.O.; Musa, S.A.; Oladele, S.B.; Iliya, A.I. Amyloid-Beta Aggregation Implicates Multiple Pathways in Alzheimer’s Disease: Understanding the Mechanisms. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1081938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Meng, Z.; Wang, S.; Kou, J.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Y. A Dual-Functional Coumarin-Based Fluorescent Probe for Turn-Off Detection of Cu2+ and Ratiometric Detection of H2S and Its Applications in Environmental Samples and Bioimaging Samples. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1294, 136390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niranjuan, R.; Prasad, G.D.; Arockiaraj, M.; Rajeshkumar, V.; Mahadevagowda, S.H. Novel coumarin-Schiff base derived electronically distinct fluorescent probes: Synthesis and comparative investigations of their unique selective sensing properties with Cu2+ and Cu⁺ ions. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1321, 139929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Huang, L.; Wang, L.; Meng, X.; Zhou, J.; Duan, H. Two Novel Coumarin-Based Fluorescent Probes for the Detection of Cu2+ and Biological Applications. J. Chem. Res. 2023, 47, 17475198231199438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataria, S.; Kaur, G.; Kaur, M.; Sareen, D. A rhodamine–coumarin conjugate as a dual-channel dual-analyte probe with logic gate operation. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1340, 142540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, C.; Pei, F.; Wang, X.; Zhang, P.; Li, H.; Sai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Chang, K.; Ni, T.; Yang, Z. Coumarin-Based Fluorescent Probes for the Detection of Copper (II) and Imaging in Mice of Wilson’s Disease. Bioorg. Chem. 2025, 154, 108051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, X.; Hu, C.; Pang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Shen, R.; Yang, A. A Coumarin-Based Multifunctional Chemosensor for Cu2+/Al3+ as an AD Theranostic Agent: Synthesis, X-Ray Single Crystal Analysis and Activity Study. Anal. Chim. Acta 2023, 1279, 341818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, X.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Zhao, Y. Coumarin-Based AIEgen Exhibiting Mechanochromism for High Selectivity and Sensitivity Detection of Cu2+ and Al3+ in Both Solution and Live Cells. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1346, 143232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, A.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, Y. A Mitochondria-Targeted Ratiometric and Colorimetric Fluorescent Probe for Hg2+ Based on Deselenation–Hydrolysis–Elimination Strategy. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 64, 17470–17478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Malik, P.; Heena; Stanzin, J.; Devi, S.; Sharma, D.; Singh, K.N.; Singh, J.; Singh, G.; Selvaraj, M. Coumarin Modified Silatrane: A Potent Probe for Hg(II) Ion Detection, Biological Evaluation and Acetylcholinesterase Inhibition. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 171, 113494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Wang, F. Simple Coumarin-Based Fluorescent Probe for Recognition of Pd(II) and Its Live Cell Imaging. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 35121–35126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanti, R.; Butcher, R.J.; Swarnakar, A.; Sarkar, S.; Goswami, S. A New Coumarin–Pyridyl Based Probe for Zn(II) and Effective Detection of Nitro Aromatics by Zn(II) Complex in Aqueous Medium: Live Cell Imaging and Practical Applications. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1350, 143864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, X.; Yang, F.; Gao, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhang, L.; Gao, Y. A Coumarin-Based Red-Emitting Fluorescent Probe for Sequential Detection of Fe3+ and PPi, and Its Applications in Real Water Sample and Bioimaging In Vivo. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1345, 141572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Debnath, J. Autophagy at the crossroads of catabolism and anabolism. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Czaja, M. Regulation of lipid stores and metabolism by lipophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2013, 20, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francisco, T.N.; Malafaia, D.; Melo, L.; Silva, A.M.S.; Albuquerque, H.M.T. Recent Advances in Fluorescent Theranostics for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Comprehensive Survey on Design, Synthesis, and Properties. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 13556–13591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Nam, J.S.; Lee, C.G.; Park, M.; Yoo, C.M.; Rhee, H.W.; Seo, J.K.; Kwon, T.H. Analysing the mechanism of mitochondrial oxidation-induced cell death using a multifunctional iridium(III) photosensitiser. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.-Z.; Yao, S.; Wu, J.; Diao, J.; He, W.; Guo, Z.; Chen, Y. Recent Advances in Single Fluorescent Probes for Monitoring Dual Organelles in Two Channels. Smart Mol. 2024, 20, 2304400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Zhang, T.; Song, Y.; Sang, Z.; Zeng, H.; Liu, P.; Wang, P.; Ge, G. Rationally Engineered hCES2A Near-Infrared Fluorogenic Substrate for Functional Imaging and High-Throughput Inhibitor Screening. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 15665–15672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, Q.; Feng, G. One-Stone, Three-Birds: A Smart Single Fluorescent Probe for Simultaneous and Discriminative Imaging of Lysosomes, Lipid Droplets, and Mitochondria. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 2671–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Kang, J.; Ye, T.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, G.; Pan, J. Application of a Novel Coumarin-Derivative Near-Infrared Fluorescence Probe to Amyloid-β Imaging and Inhibition in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Lumin. 2023, 256, 119661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, N.; Bhuskute, K.R.; Varghese, N.R.; Buchanan, J.A.; Xu, Y.; McCutcheon, F.M.; Medcalf, R.L.; Jolliffe, K.A.; Sunde, M.; New, E.J.; et al. A Coumarin-Based Array for the Discrimination of Amyloids. ACS Sens. 2024, 9, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Z.; Fu, Y.; Fu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, H.; Xu, M.-H. Design of a Coumarin-Based Fluorescent Probe for Efficient In Vivo Imaging of Amyloid-β Plaques. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2023, 14, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, J.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, F.; Kim, J.S. Engineering of BODIPY-Based Theranostics for Cancer Therapy. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 476, 214908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, R.C.; Papageorgiou, P.S.; Pitsillos, R.; Woodward, A.; Papageorgiou, S.G.; Solomou, E.E.; Georgiou, M.F. A Narrative Review of Theranostics in Neuro-Oncology: Advancing Brain Tumor Diagnosis and Treatment Through Nuclear Medicine and Artificial Intelligence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Huang, J.; Pu, K. Near-Infrared Chemiluminescent Theranostics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202501681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, J.; Gong, Q.; Udochukwu Akakuru, O.; Liu, C.; Zou, R.; Wu, A. Research Advances in Integrated Theranostic Probes for Tumor Fluorescence Visualization and Treatment. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 24311–24330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimizonuzi, H.; Ghayourvahdat, A.; Ahmed, M.H.; Kareem, R.A.; Zrzor, A.J.; Mansoor, A.S.; Athab ZHKalavi, S. A State-of-the-Art Review of the Recent Advances of Theranostic Liposome Hybrid Nanoparticles in Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis. Cancer Cell Int. 2025, 25, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorasani, A.; Shahbazi-Gahrouei, D.; Safari, A. Recent Metal Nanotheranostics for Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy: A Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkett, B.J.; Bartlett, D.J.; McGarrah, P.W.; Lewis, A.R.; Johnson, D.R.; Berberoğlu, K.; Pandey, M.K.; Packard, A.T.; Halfdanarson, T.R.; Hruska, C.B.; et al. A Review of Theranostics: Perspectives on Emerging Approaches and Clinical Advancements. Radiol. Imaging Cancer 2023, 5, e220157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Verwillst, P.; Liu, M.; Ma, D.; Singh, N.; Yoo, J.; Kim, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, J.-H.; Huang, H.; et al. Theranostic Fluorescent Probes. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 2699–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratihar, S.; Bhagavath, K.K.; Govindaraju, T. Small Molecules and Conjugates as Theranostic Agents. RSC Chem. Biol. 2024, 4, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, N.-N.; Hu, M.-H. Coumarin-Based Fluorescent Ligands Target Mitochondrial G-Quadruplexes for Liver Cancer Growth Suppression. Bioorg. Chem. 2025, 167, 109275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zutão, A.D.; Pachane, B.C.; Nunes, P.S.G.; Vidal, H.D.A.; Sobrinho Selistre-de-Araujo, H.; Corrêa, A.G.; Cominetti, M.R.; Fuzer, A.M. Enhanced Cytotoxicity of 10-Gingerol–Coumarin–Triazole Hybrid as a Theranostic Agent for Triple Negative Breast Cancer. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2025, 16, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Szwaczko, K.; Kulkowska, A.; Matwijczuk, A. Advances in Coumarin Fluorescent Probes for Medical Diagnostics: A Review of Recent Developments. Biosensors 2026, 16, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010036

Szwaczko K, Kulkowska A, Matwijczuk A. Advances in Coumarin Fluorescent Probes for Medical Diagnostics: A Review of Recent Developments. Biosensors. 2026; 16(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010036

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzwaczko, Katarzyna, Aleksandra Kulkowska, and Arkadiusz Matwijczuk. 2026. "Advances in Coumarin Fluorescent Probes for Medical Diagnostics: A Review of Recent Developments" Biosensors 16, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010036

APA StyleSzwaczko, K., Kulkowska, A., & Matwijczuk, A. (2026). Advances in Coumarin Fluorescent Probes for Medical Diagnostics: A Review of Recent Developments. Biosensors, 16(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010036