A Novel Approach for Tissue Analysis in Joint Infections Using the Scattered Light Integrating Collector (SLIC)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

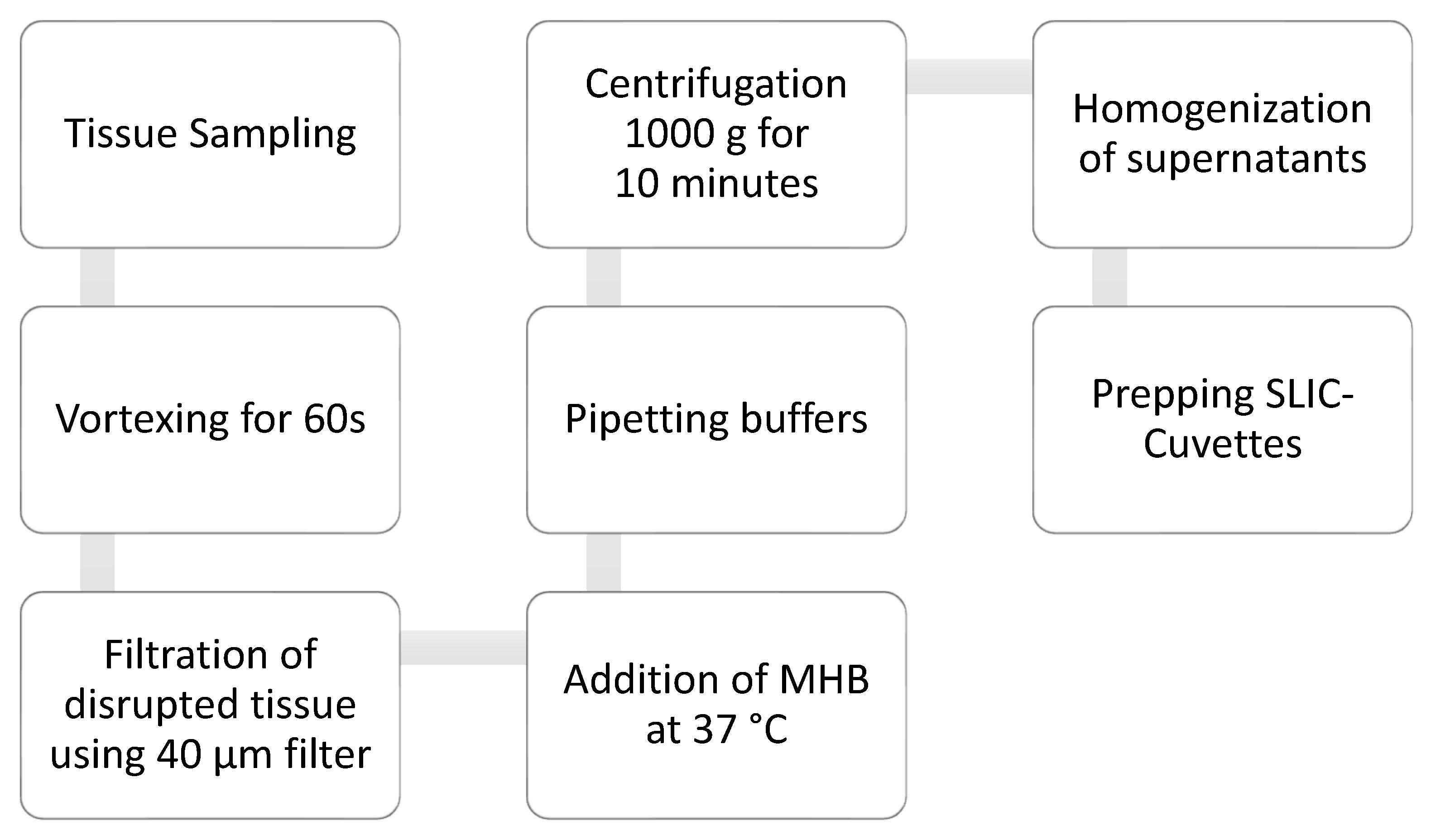

2.2. Sample Processing

2.2.1. Coagulation Interference Tests

2.2.2. Storage Tests

2.2.3. Sample Amount

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.3.1. Area Under the Curve (AUC)

2.3.2. Endpoint Analysis (Mean 300 min)

2.3.3. Slope

2.3.4. Data Folds (Storage Testing)

2.4. SLIC Technology

3. Results

3.1. Proof of Concept

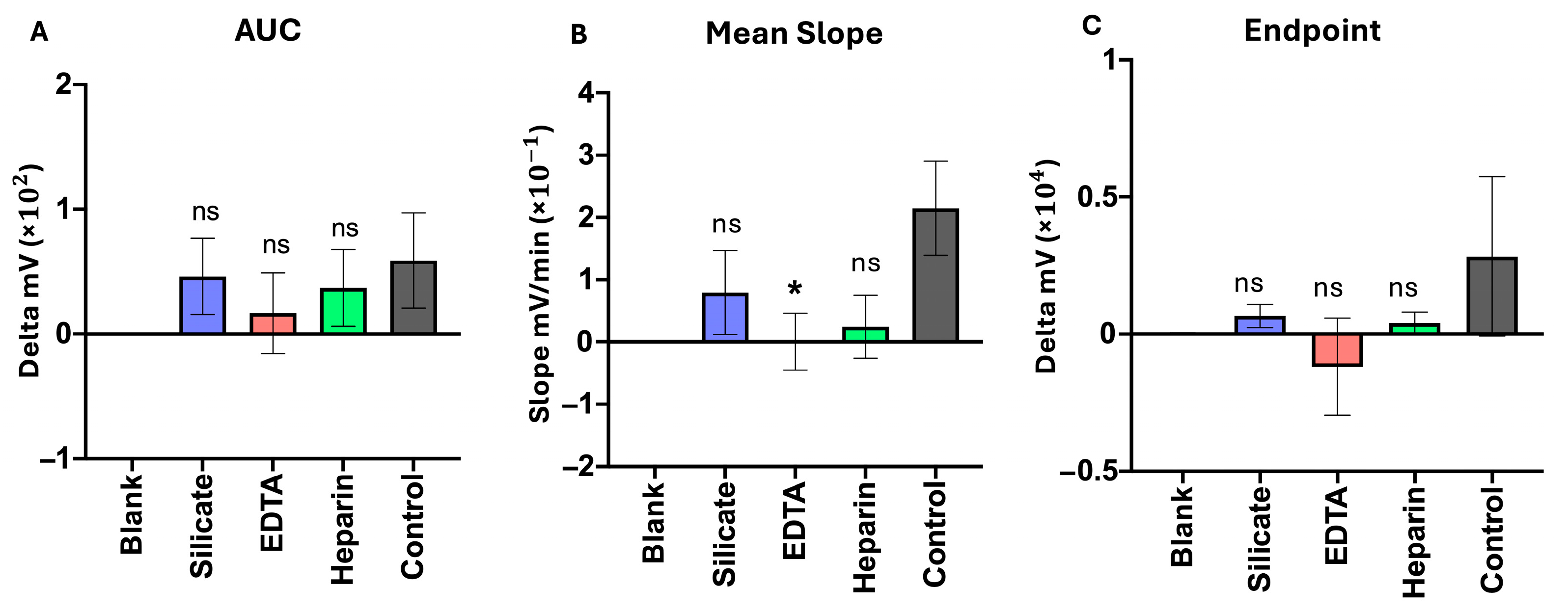

3.2. Coagulation Interference Tests

3.3. Storage Tests

3.4. Sample Amount

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hischebeth, G.T.R.; Randau, T.M.; Molitor, E.; Wimmer, M.D.; Hoerauf, A.; Bekeredjian-Ding, I.; Gravius, S. Comparison of bacterial growth in sonication fluid cultures with periprosthetic membranes and with cultures of biopsies for diagnosing periprosthetic joint infection. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016, 84, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad, C.L.; Haleem, A. Prosthetic Joint Infections: An Update. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2018, 20, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wengler, A.; Nimptsch, U.; Mansky, T. Hip and knee replacement in Germany and the USA: Analysis of individual inpatient data from German and US hospitals for the years 2005 to 2011. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2014, 111, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymski, D.; Walter, N.; Hierl, K.; Rupp, M.; Alt, V. Direct Hospital Costs per Case of Periprosthetic Hip and Knee Joint Infections in Europe—A Systematic Review. J. Arthroplast. 2024, 39, 1876–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupp, M.; Kerschbaum, M.; Freigang, V.; Bärtl, S.; Baumann, F.; Trampuz, A.; Alt, V. PJI-TNM als neues Klassifikationssystem für Endoprotheseninfektionen. Orthopäde 2021, 50, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izakovicova, P.; Borens, O.; Trampuz, A. Periprosthetic joint infection: Current concepts and outlook. EFORT Open Rev. 2019, 4, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannotti, F.; Prati, P.; Fidanza, A.; Iorio, R.; Ferretti, A.; Pèrez Prieto, D.; Kort, N.; Violante, B.; Pipino, G.; Schiavone Panni, A.; et al. Prevention of Periprosthetic Joint Infection (PJI): A Clinical Practice Protocol in High-Risk Patients. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 5, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.S.; Rao, A.; Manadan, A.M.; Block, J.A. Peripheral Bacterial Septic Arthritis: Review of Diagnosis and Management. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2017, 23, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Arias, M.; Balsa, A.; Mola, E.M. Septic arthritis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2011, 25, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirtliff, M.E.; Mader, J.T. Acute septic arthritis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2002, 15, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, G.S.; Parvizi, J. Think Twice before Prescribing Antibiotics for That Swollen Knee: The Influence of Antibiotics on the Diagnosis of Periprosthetic Joint Infection. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darwich, A.; Dally, F.J.; Abu Olba, K.; Mohs, E.; Gravius, S.; Hetjens, S.; Assaf, E.; Bdeir, M. Superinfection with Difficult-to-Treat Pathogens Significantly Reduces the Outcome of Periprosthetic Joint Infections. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akgün, D.; Perka, C.; Trampuz, A.; Renz, N. Outcome of hip and knee periprosthetic joint infections caused by pathogens resistant to biofilm-active antibiotics: Results from a prospective cohort study. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2018, 138, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axelsson, C.; Rehnstam-Holm, A.S.; Nilson, B. Rapid detection of antibiotic resistance in positive blood cultures by MALDI-TOF MS and an automated and optimized MBT-ASTRA protocol for Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect. Dis. (Lond.) 2020, 52, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, R.J.H.; Falconer, K.; Powell, T.; Bowness, R.; Gillespie, S.H. A simple label-free method reveals bacterial growth dynamics and antibiotic action in real-time. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreolla, E.; Fernandes, M.B.C.; Lima, C.; Saraiva, A.C.M. ANALYSIS OF TISSUE BIOPSY AND JOINT ASPIRATION IN THE DIAGNOSIS OF PERIPROSTHETIC HIP INFECTIONS: CROSS-SECTIONAL STUDY. Acta Ortop. Bras. 2021, 29, 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieber, H.; Frontzek, A.; Heinrich, S.; Breil-Wirth, A.; Messler, J.; Hegermann, S.; Ulatowski, M.; Koutras, C.; Steinheisser, E.; Kruppa, T.; et al. Microbiological diagnosis of polymicrobial periprosthetic joint infection revealed superiority of investigated tissue samples compared to sonicate fluid generated from the implant surface. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 106, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signore, A.; Sconfienza, L.M.; Borens, O.; Glaudemans, A.W.J.M.; Cassar-Pullicino, V.; Trampuz, A.; Winkler, H.; Gheysens, O.; Vanhoenacker, F.M.H.M.; Petrosillo, N.; et al. Consensus document for the diagnosis of prosthetic joint infections: A joint paper by the EANM, EBJIS, and ESR (with ESCMID endorsement). Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2019, 46, 971–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, M.; Sousa, R.; Wouthuyzen-Bakker, M.; Chen, A.F.; Soriano, A.; Vogely, H.C.; Clauss, M.; Higuera, C.A.; Trebše, R. The EBJIS definition of periprosthetic joint infection. Bone Jt. J. 2021, 103-b, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, M.; Rosas, J.; Iborra, J.; Manero, H.; Pascual, E. Comparison of manual and automated cell counts in EDTA preserved synovial fluids. Storage has little influence on the results. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1997, 56, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo, M.E.; Salvadó, M.; Trampuz, A.; Plasencia, V.; Rodriguez-Villasante, M.; Sorli, L.; Puig, L.; Horcajada, J.P. Sonication versus vortexing of implants for diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 591–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Zhang, L.; Cai, Y.; Huang, Z.; Li, W.; Zhang, C.; Yang, B.; Lin, J.; Wahl, P.; Zhang, W. Effects of different tissue specimen pretreatment methods on microbial culture results in the diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection. Bone Jt. Res. 2021, 10, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandakhalikar, K.D.; Rahmat, J.N.; Chiong, E.; Neoh, K.G.; Shen, L.; Tambyah, P.A. Extraction and quantification of biofilm bacteria: Method optimized for urinary catheters. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, N.G.; McCaffrey, D.; Mackle, E. Contamination of histology biopsy specimen—A potential source of error for surgeons: A case report. Cases J. 2009, 2, 7619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lew, K. 3.05—Blood Sample Collection and Handling. In Comprehensive Sampling and Sample Preparation; Pawliszyn, J., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 95–121. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Gazendam, A.; Wood, T.J.; Tushinski, D.; Bali, K. Diagnosing Periprosthetic Joint Infection: A Scoping Review. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2022, 15, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, N.D.; Jennings, J.M. Joint aspiration for diagnosis of chronic periprosthetic joint infection: When, how, and what tests? Arthroplasty 2023, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutler, E.; Gelbart, T.; Kuhl, W. Interference of heparin with the polymerase chain reaction. Biotechniques 1990, 9, 166. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, N.Y.L.; Rainer, T.H.; Chiu, R.W.K.; Lo, Y.M.D. EDTA Is a Better Anticoagulant than Heparin or Citrate for Delayed Blood Processing for Plasma DNA Analysis. Clin. Chem. 2004, 50, 256–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazmati, N.; Liebold, C.; Offerhaus, C.; Volkenand, A.; Grote, S.; Pöpsel, J.; Körber-Irrgang, B.; Hoppe, T.; Wisplinghoff, H. Rapid high-throughput processing of tissue samples for microbiological diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infections using bead-beating homogenization. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2024, 62, e0148623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askar, M.; Ashraf, W.; Scammell, B.; Bayston, R. Comparison of different human tissue processing methods for maximization of bacterial recovery. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 38, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAnulty, J.F. Hypothermic organ preservation by static storage methods: Current status and a view to the future. Cryobiology 2010, 60, S13–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.D.S.; De Melo, B.S.T.; Oliva, A.; de Araújo, P.S.R. Sonication protocols and their contributions to the microbiological diagnosis of implant-associated infections: A review of the current scenario. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1398461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieslinski, J.; Ribeiro, V.S.T.; Kraft, L.; Suss, P.H.; Rosa, E.; Morello, L.G.; Pillonetto, M.; Tuon, F.F. Direct detection of microorganisms in sonicated orthopedic devices after in vitro biofilm production and different processing conditions. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2021, 31, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertheloot, D.; Nessler, V.B.; Assaf, E.; Amerschlager, C.F.; Ali, K.; Ossendorff, R.; Jaenisch, M.; Strauss, A.C.; Burger, C.; Walmsley, P.J.; et al. Novel Method for the Rapid Establishment of Antibiotic Susceptibility Profiles in Bacterial Strains Linked to Musculoskeletal Infections Using Scattered Light Integrated Collector Technology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, L.; Hammond, R.; Shorten, R.J.; Derrick, J.P. An investigation of scattered light integrating collector technology for rapid blood culture sensitivity testing. J. Med. Microbiol. 2024, 73, 001896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnegan, S.; Percival, S.L. EDTA: An Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Agent for Use in Wound Care. Adv. Wound Care 2015, 4, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Morin, P.A. Optimal storage conditions for highly dilute DNA samples: A role for trehalose as a preserving agent. J. Forensic Sci. 2005, 50, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, Z.T. A hands-on overview of tissue preservation methods for molecular genetic analyses. Org. Divers. Evol. 2010, 10, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cauter, M.; Cornu, O.; Yombi, J.C.; Rodriguez-Villalobos, H.; Kaminski, L. The effect of storage delay and storage temperature on orthopaedic surgical samples contaminated by Staphylococcus Epidermidis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, S.F.; Williams, C.J.; Lendrem, B.C.; Wilson, K.J. Sample size determination for point-of-care COVID-19 diagnostic tests: A Bayesian approach. Diagn. Progn. Res. 2023, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, M.C.; Smith, C.; Pritchard, C.C.; Tait, J.F. DNA Yield From Tissue Samples in Surgical Pathology and Minimum Tissue Requirements for Molecular Testing. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2016, 140, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazares, L.H.; Van Tongeren, S.A.; Costantino, J.; Kenny, T.; Garza, N.L.; Donnelly, G.; Lane, D.; Panchal, R.G.; Bavari, S. Heat fixation inactivates viral and bacterial pathogens and is compatible with downstream MALDI mass spectrometry tissue imaging. BMC Microbiol. 2015, 15, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayser, K.; Schultz, H.; Goldmann, T.; Görtler, J.; Kayser, G.; Vollmer, E. Theory of sampling and its application in tissue based diagnosis. Diagn. Pathol. 2009, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Renz, N.; Trampuz, A.; Ojeda-Thies, C. Twenty common errors in the diagnosis and treatment of periprosthetic joint infection. Int. Orthop. 2020, 44, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portillo, M.E.; Sancho, I. Advances in the Microbiological Diagnosis of Prosthetic Joint Infections. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicenti, G.; Bizzoca, D.; Nappi, V.; Pesce, V.; Solarino, G.; Carrozzo, M.; Moretti, F.; Dicuonzo, F.; Moretti, B. Serum biomarkers in the diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection: Consolidated evidence and recent developments. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenstern, C.; Renz, N.; Cabric, S.; Maiolo, E.; Perka, C.; Trampuz, A. Thermogenic diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection by microcalorimetry of synovial fluid. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2020, 21, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Ni, M.; Chai, W.; Li, X.; Hao, L.; Chen, J. Synovial Fluid Viscosity Test is Promising for the Diagnosis of Periprosthetic Joint Infection. J. Arthroplast. 2019, 34, 1197–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo, S.; Davoudian, K.; De La Franier, B.; Hianik, T.; Thompson, M. Staphylococcus aureus Detection in Milk Using a Thickness Shear Mode Acoustic Aptasensor with an Antifouling Probe Linker. Biosensors 2023, 13, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Bhat, A.; O’Connor, C.; Curtin, J.; Singh, B.; Tian, F. Review of Detection Limits for Various Techniques for Bacterial Detection in Food Samples. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lu, F.; Wang, Y.; Ji, J.; Xu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, M.; Xia, J.; Wang, B. Methodological comparison of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid-based detection of respiratory pathogens in diagnosis of bacterium/fungus-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1168812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Assaf, E.; Amerschläger, C.F.; Nessler, V.B.; Ali, K.; Ossendorff, R.; Jaenisch, M.; Strauss, A.C.; Burger, C.; Hischebeth, G.T.; Walmsley, P.J.; et al. A Novel Approach for Tissue Analysis in Joint Infections Using the Scattered Light Integrating Collector (SLIC). Biosensors 2025, 15, 795. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120795

Assaf E, Amerschläger CF, Nessler VB, Ali K, Ossendorff R, Jaenisch M, Strauss AC, Burger C, Hischebeth GT, Walmsley PJ, et al. A Novel Approach for Tissue Analysis in Joint Infections Using the Scattered Light Integrating Collector (SLIC). Biosensors. 2025; 15(12):795. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120795

Chicago/Turabian StyleAssaf, Elio, Cosmea F. Amerschläger, Vincent B. Nessler, Kani Ali, Robert Ossendorff, Max Jaenisch, Andreas C. Strauss, Christof Burger, Gunnar T. Hischebeth, Phillip J. Walmsley, and et al. 2025. "A Novel Approach for Tissue Analysis in Joint Infections Using the Scattered Light Integrating Collector (SLIC)" Biosensors 15, no. 12: 795. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120795

APA StyleAssaf, E., Amerschläger, C. F., Nessler, V. B., Ali, K., Ossendorff, R., Jaenisch, M., Strauss, A. C., Burger, C., Hischebeth, G. T., Walmsley, P. J., Wirtz, D. C., Hammond, R. J. H., Bertheloot, D., & Schildberg, F. A. (2025). A Novel Approach for Tissue Analysis in Joint Infections Using the Scattered Light Integrating Collector (SLIC). Biosensors, 15(12), 795. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120795