Immunosensing Platforms for Detection of Metabolic Biomarkers in Oral Fluids

Abstract

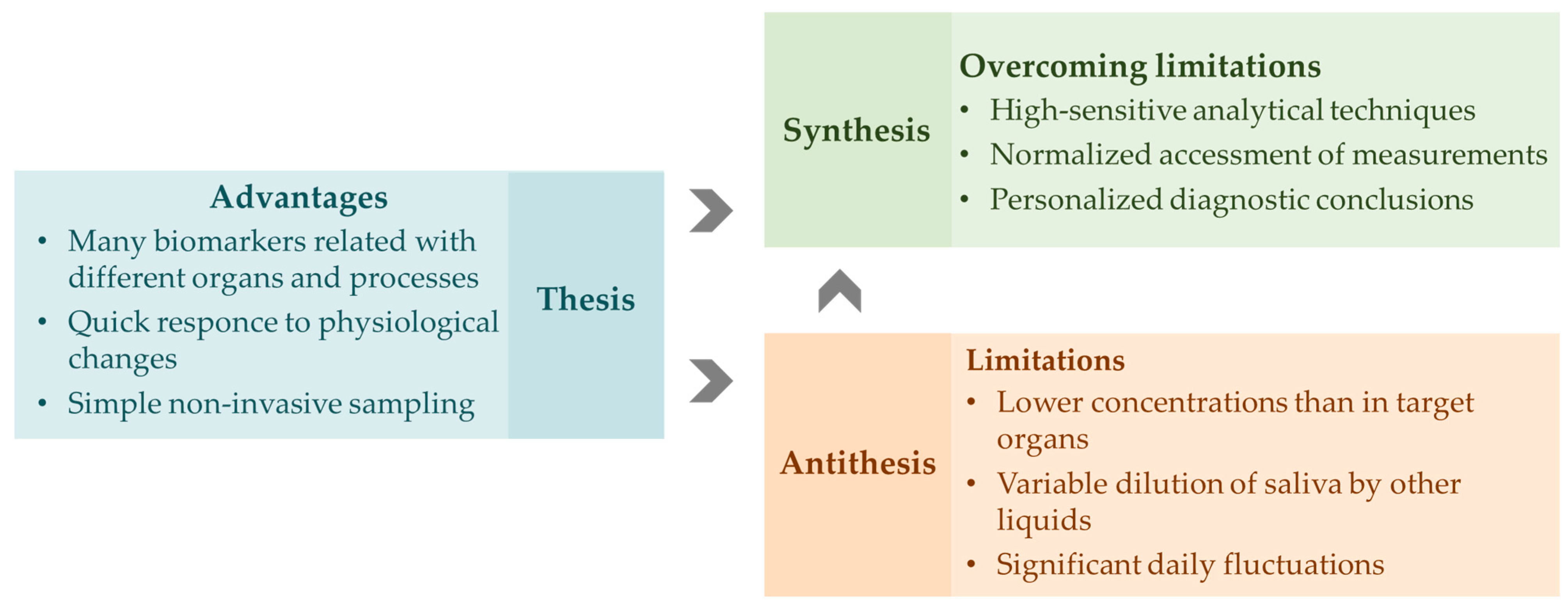

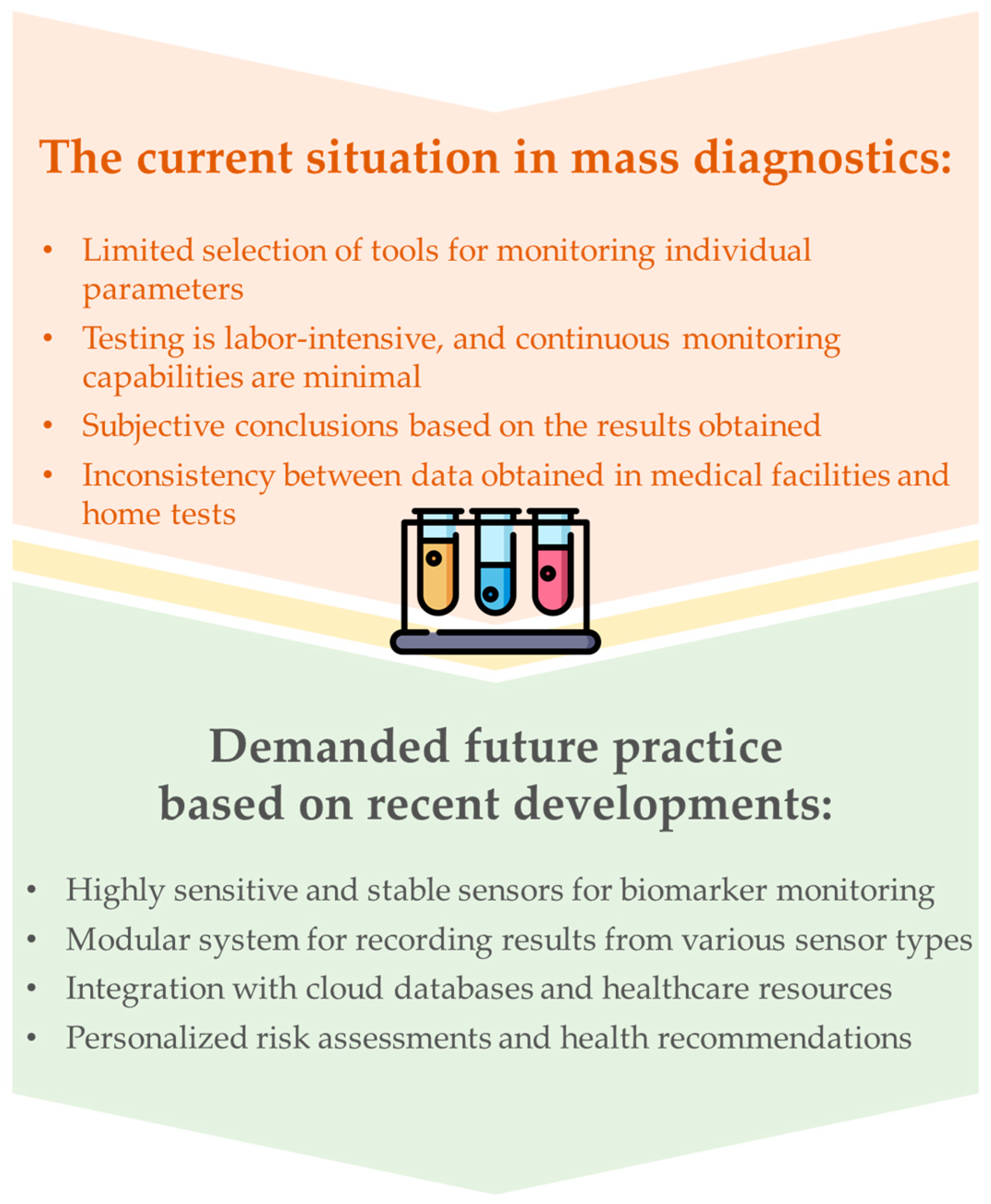

1. Introduction

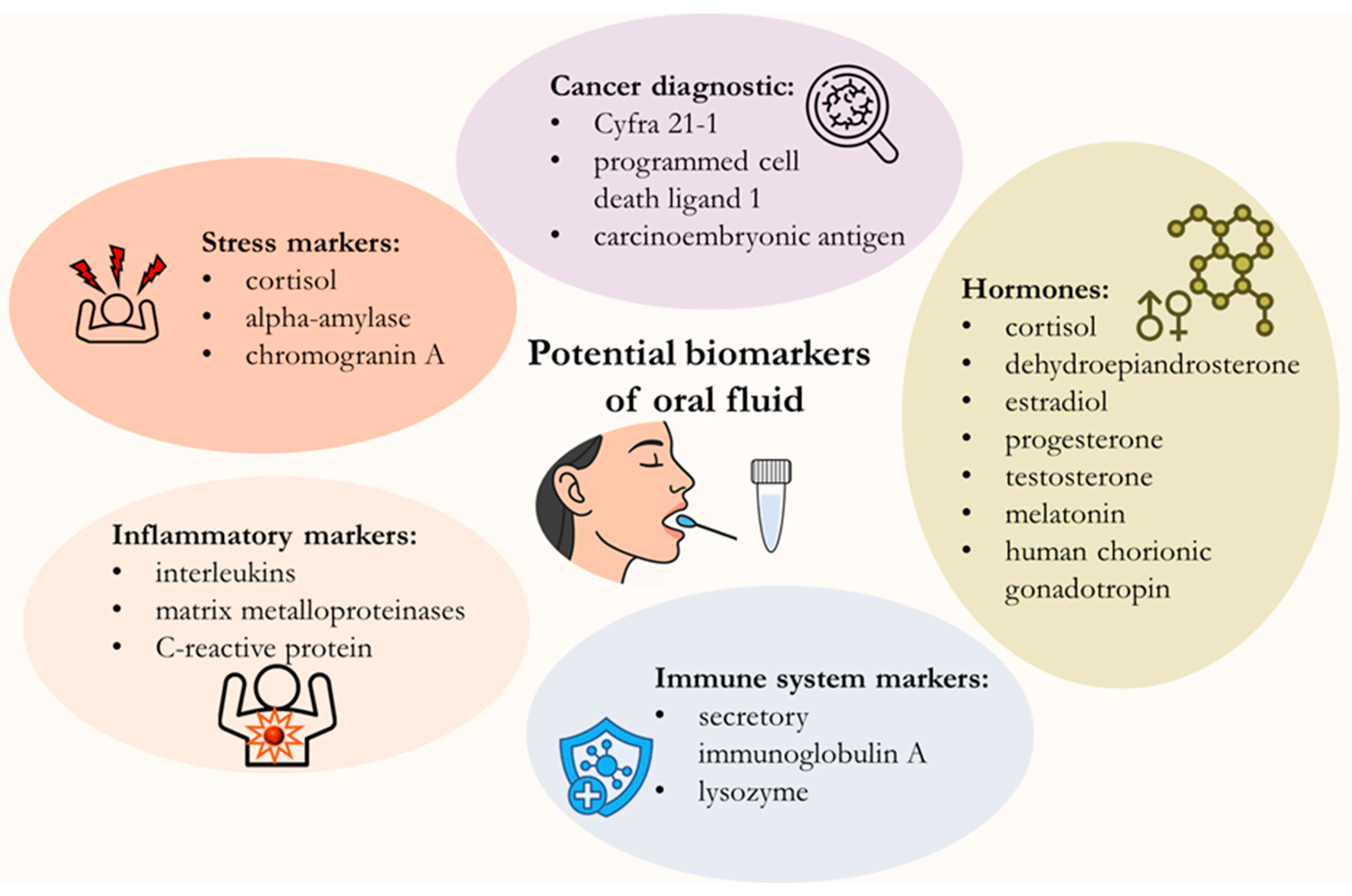

2. Potential Biomarkers in Saliva

| Biomarker | Reference Range in Saliva | Diagnostic Value (Clinical Indications) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| alpha-amylase | Varies from 2 to 900 U/mL |

| [47,49,60] |

| Calprotectin | low or undetectable |

| [61] |

| Chromogranin A | levels fluctuate based on time of day, physiological stress, and individual health conditions | Increases with mental and physical activity or acute stress | [62,63] |

| Cortisol |

|

| [28,30,64] |

| Cortisone |

|

| [30,65] |

| Cotinine | significant exposure: >1 ng/mL; minor exposure: <1 ng/mL | biomarker of tobacco smoke exposure | [66,67] |

| C-reactive protein | low, often below 1 ng/mL, or undetectable level |

| [68,69] |

| Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate | 0.6–7.4 ng/mL for females and 0.6–10.1 ng/mL for males |

| [31,32] |

| Estradiol | varies throughout the menstrual cycle and hormonal status, sub-pg/mL range |

| [55,56,70] |

| Free testosterone | vary significantly by age and sex, ~50–150 pg/mL for men ~10–50 pg/mL for women |

| [51,52,71,72] |

| Glucose | In non-diabetic group ~0.5–1 mg/mL |

| [47,73] |

| Hepcidin | Positive iron deficiency anemia: above 5.5 ng/mL; Negative iron deficiency anemia: 1.56 ng/mL < Hepcidin < 5.5 ng/mL |

| [74,75] |

| Insulin | Fasting cut-off value ∼16 pmol/L |

| [76] |

| Interleukins | low or undetectable |

| [37,77] |

| Lactate | 0.1–2.5 mM |

| [78,79] |

| Lysozyme | 1–57 μg/mL |

| [80,81] |

| Melatonin | vary significantly by time of day and individual factors, daytime levels range from 1 to 10 pg/mL |

| [82,83,84] |

| Progesterone | varies throughout the menstrual cycle, sub-ng/mL range |

| [54,57,85] |

| Pyruvic acid | - |

| [86,87] |

| Secretory immunoglobulin A | 100–900 µg/mL |

| [41,43,88,89] |

| Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha | low or undetectable, vary based on age, gender, and health status |

| [90,91] |

| Vitamin D | varies in the range from units to hundreds of pg/mL |

| [92] |

3. Current Techniques for Biomarker Detection in Oral Fluid

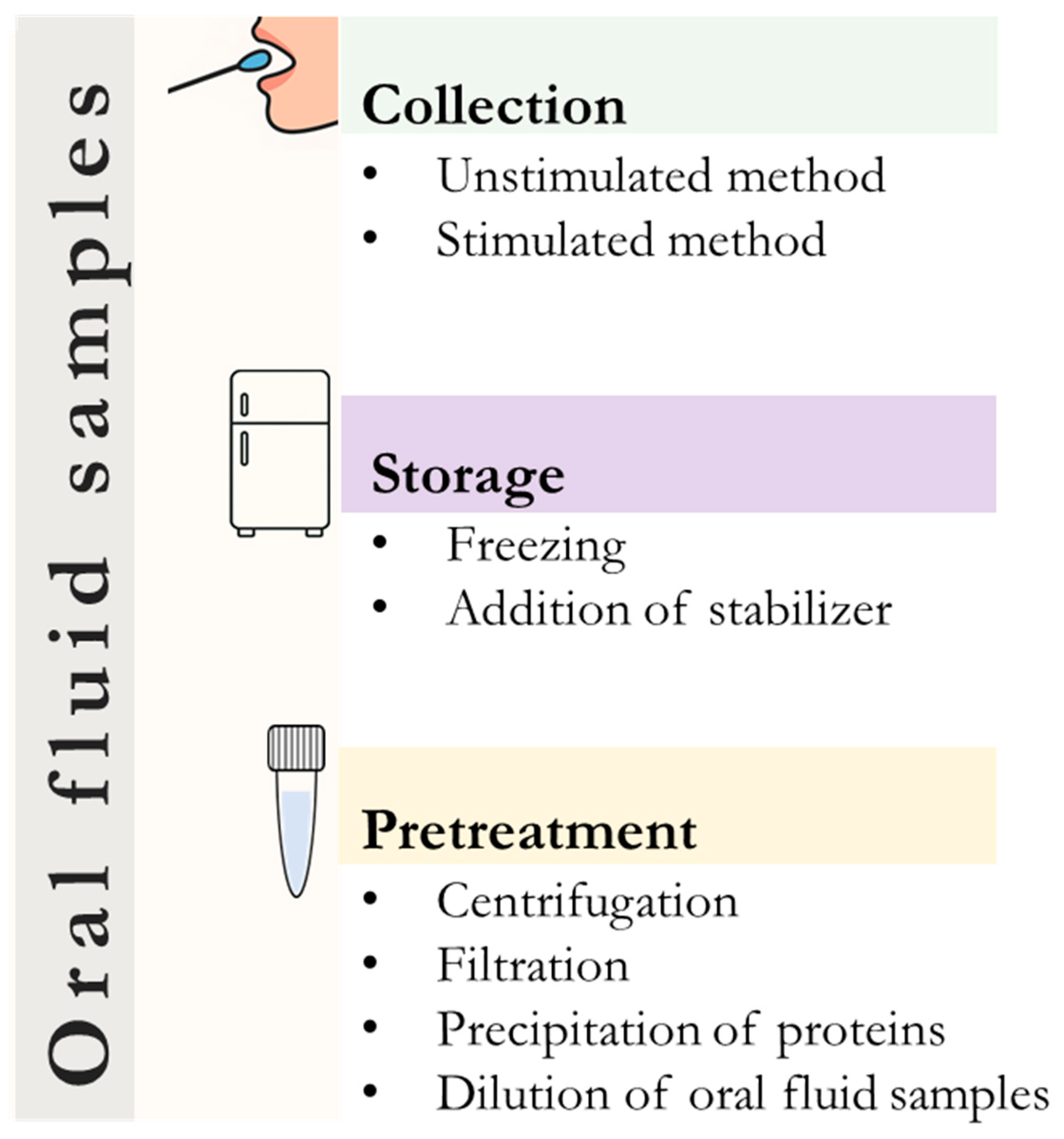

4. Sample Collection and Pretreatment

5. Non-Invasive Oral Fluid Analysis Using Immunosensors

5.1. Development of Optical Membrane Immunosensors

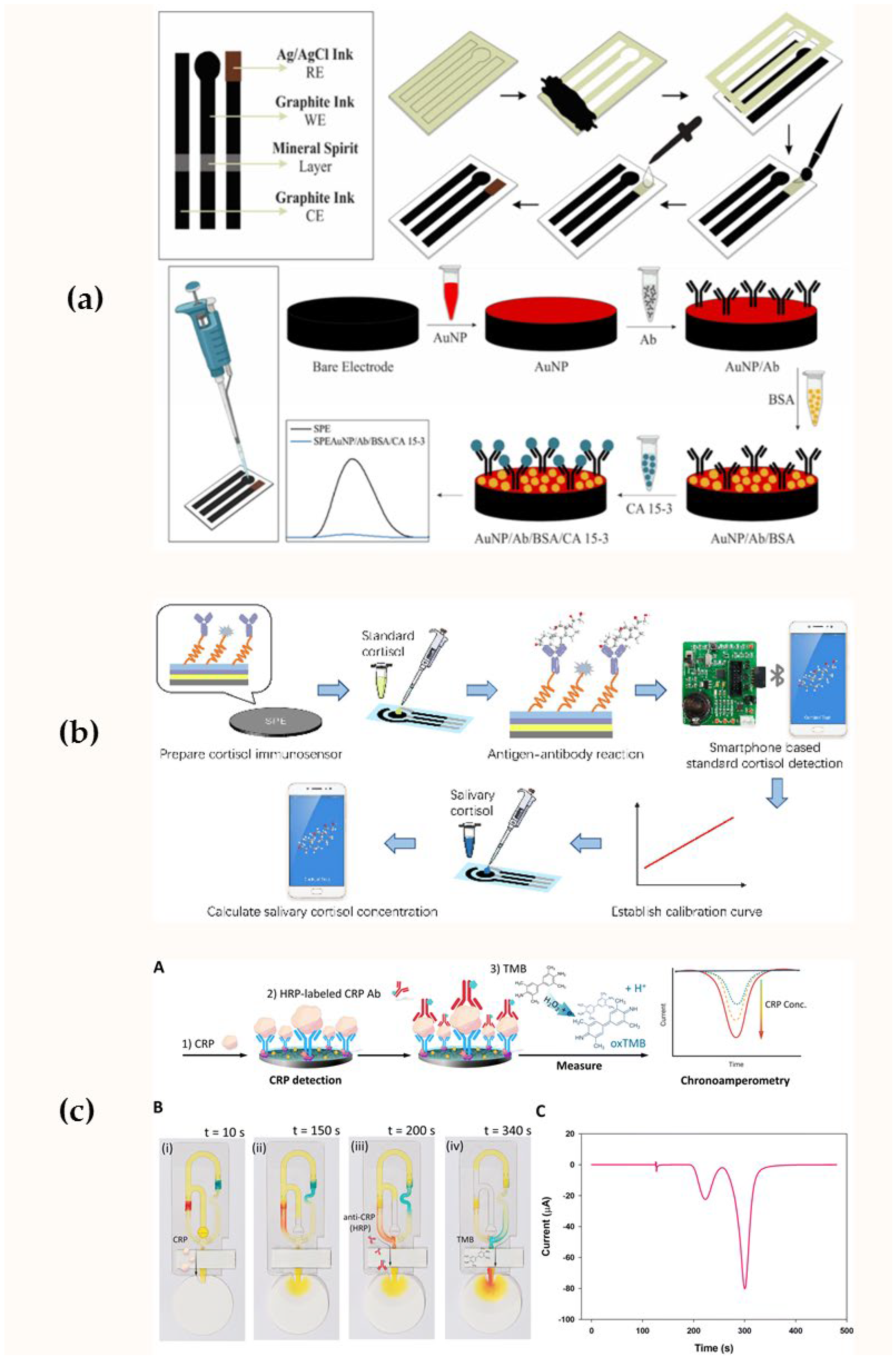

5.2. Development of Electrochemical Immunosensors

| Sensor Design | Working Electrode | Transduction Principle | Analyte | Detection Range | Limit of Detection | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amperometric immunosensors | ||||||

| Multiplex sandwich-type immunosensor platform | disposable carbon electrodes with four working surfaces | amperometry | IL-6, receptor activator of NF-kB ligand, protein arginine deiminase 4 | IL-6: 2.0–1000 pg/mL; RANKL: 2.5–1000 pg/mL; PAD4: 0.1–1000 ng/mL; anti-PAD4: 10–1000 ng/mL | IL-6 0.09 pg/mL RANKL 0.10 pg/mL PAD4 0.09 ng/mL anti-PAD4 14.5 ng/mL | [148] |

| multiplexed immunoplatform with four-channel potentiostat | four working electrodes of the screen-printed carbon electrode array | amperometry | progesterone, luteinizing hormone, estradiol, prolactin | progesterone: 38.1–250.0 pg/mL; estradiol: 23.3–50,000 pg/mL; luteinizing hormone: 1.0–100.0 mIU/mL; prolactin: 1–100 ng/mL | progesterone 2.85 pg/mL estradiol 5.88 pg/mL luteinizing hormone 0.30 mIU/mL prolactin 0.32 ng/mL | [155] |

| miniaturized, silicon-based sensor | gold sensing electrodes, modified with AuNPs (3D dendric nanostructures) | amperometry | lactoferrin and amyloid β-protein 1-42 | Lactoferrin: 2–32 μg/mL amyloid β-protein 1-42: 0.1–1 ng/mL | Lactoferrin: 2 μg/mL; amyloid β-protein 1-42: 0.1 pg/mL | [162] |

| dual sandwich-type immunosensor | screen-printed dual carbon electrodes modified with reduced graphene oxide and crystalline nanocellulose | amperometry | MMP-9 and MMP-13 | 1.0–1000 ng/mL | MMP-9 0.25 ng/mL MMP-13 0.30 ng/mL | [142] |

| Sandwich-type immunosensor | a screen-printed carbon electrode | chrono- amperometry | galectin-3 | n/a | 9.66 ng/mL | [150] |

| capillary-driven microfluidic immunosensor | screen-printed carbon electrode | chrono- amperometry | C-reactive protein | 0.625–10.0 μg/mL | 0.751 μg/mL | [172] |

| A dual bioelectronic sensor chip | two Au-sputtered electrodes | chrono- amperometry | vitamin C and vitamin D | vitamin C: 0–800 μM; vitamin D: 0–200 ng/mL | vitamin D: 29 ng/mL in buffer and 12 ng/mL in saliva; vitamin C: 28 μM in buffer and 84 µM in saliva | [169] |

| A dual-marker biosensor chip | two Au electrodes | chrono- amperometry | Insulin and glucose | Glucose: 0–20 mM; Insulin: 0–1200 pM | glucose: 0.2 mM; insulin: 41 pM | [170] |

| disposable immunosensing platforms using a field-portable dual potentiostat | disposable screen-printed carbon electrode | amperometry | luteinizing hormone and progesterone | luteinizing hormone: 0.3–125 mIU/mL; progesterone: 10−2–103 ng/mL | luteinizing hormone 0.10 mIU/mL; Progesterone 1.7 pg/mL | [156] |

| sandwich-type immunoplatform | cerium dioxide nanoparticles/ multi-walled carbon nanotubes composite | amperometry | myeloperoxidase | 1.0–100.0 ng/mL | 0.40 ng/mL | [143] |

| Impedance immunosensors | ||||||

| digital sensor chip | micro-Au electrodes | impedance | cortisol | 1 pg/mL– 10 mg/mL | 0.87 pg/mL | [154] |

| immunosensor | gold microelectrodes biofunctionalized using 4-carboxymethyl aryl diazonium | impedance | N-Terminal Natriuretic Peptide | 1–20 pg/mL | 0.03 pg/mL | [157] |

| A sensor chip with an electrical impedance analyzer | hybrid nanocomposite of graphene nanoplatelets with diblock co-polymers and Au electrodes | impedance | Prostate specific antigen | 0.0001–100 ng/mL | 40 fg/mL | [141] |

| immunosensing strip | screen-printed carbon electrode functionalized by carbon spherical shells polyethylenimine, glutaraldehyde | impedance | brain-derived neurotrophic factor | 10–20–10–10 g/mL | 10–20 g/mL | [158] |

| microfluidic impedance cytometer chip (with machine learning) | two gold microelectrodes on a glass substrate with a polydimethyl siloxane channel | impedance | IgG/IgA | n/a | 16.67 nM for IgG/IgA ratio | [161] |

| Voltammetric immunosensors | ||||||

| Electroactive interface-based immunosensor | silver nanoparticle-decorated titanium carbide MXene nanosheets modified screen-printed electrode | differential pulse voltammetry | TNF-α | 1–180 pg/mL | 0.97 pg/mL | [145] |

| disposable voltammetric immunosensor | screen-printed paper-based electrode modified with gold nanoparticle | voltammetry | CA 15-3 | 2–16 U/mL | 0.56 U/mL | [167] |

| Electrocatalysts-based immunosensor | glassy carbon electrode modified with flower-structured MoS2/ZnO composite | differential pulse voltammetry | IL-8 | 500–4500 pg/mL | 11.6 fM | [159] |

| Sandwich-type immunoassay | Au electrode | differential pulse voltammetry | sIgA silica nanochannel film | 10–300 ng/mL | 10 ng/mL | [147] |

| flexible three-electrode paper-based immunosensor | three-electrode system based on synthesized Ag ink with pen-on-paper technology on the surface of photographic paper | differential pulse voltammetry | Cyfra 21.1 | 0.0025–10 ng/mL | 0.0025 ng/mL | [166] |

| multiplex immunosensor | gold micro-electrodes modified by gold foam | differential pulse voltammetry | IgG and IL-8 | IgG: 0.01–1 pg/mL; IL-8: 0.01–1 pg/mL | IgG: 69.2 fg/mL; IL-8: 87.6 fg/mL | [171] |

| Other types of immunosensors | ||||||

| a paper-based electrical biosensor chip integrated with a printed circuit board | polymer– graphene nanoplatelets composite on Au electrodes | conductometry | cortisol | 3 pg/mL–10 μg/mL | 50 pg/mL | [153] |

| Sandwich-type immunosensor | glassy carbon electrod modified with ZnO nanoparticles | chronopotentiometry | cortisol | 10–7–102 nM | 5 × 10–7 nM | [144] |

| biphasic sandwich-type immunoassay based on tyramine-DNA cascade signal amplification | indium tin oxide | electrochemical with tyramine-DNA cascade signal amplification | IL-8 | 1.0–1000 pg/mL | 0.28 pg/mL | [149] |

| duplex of biosensors for multi-resonance analysis | Fiber-Bragg grating-assisted semi-distributed interferometer-based probe | interferometry | IL-6 and IL-8 | n/a | IL-6 480 aM IL-8 23.4 fM | [152] |

| signal-on photoelectrochemical competitive immunoassay | CdS/Au electrode | photoelectric | cortisol | 0.0001–100 ng/mL | 0.06 pg/mL | [146] |

| competition-type photoelectrochemical immunosensor | Fluorine-tin-oxide/TiO2/CuInS2 quantum dots electrode | photoelectric | cortisol | 0.01–100 ng/mL | 7.8 pg/mL | [78] |

| Enhanced electrochemiluminescence immunosensor | indium tin oxide modified with mesoporous silica nanochannel film and Co3O4 nanocatalyst | electrochemiluminescence | IL-6 | 1 fg/mL–10 ng/mL | 0.64 fg/mL | [165] |

5.3. Other Optical Immunosensors

| Sensor Design | Label | Signal Generation | Analyte | Detection Range | Limit of Detection | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sensing immune platform | AuNPs@HRP@FeMOF immune scaffold | colorimetric | Cyfra 21-1 | 3.1–50.0 ng/mL | 0.37 ng/mL | [193] |

| dual-mode sensing platform | silver nanoclusters with MnO2 nanosheets | fluorescence | PD-L1 | 1.98–196.78 pg/mL | 0.44 pg/mL | [182] |

| fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based immunoassay | Zn2GeO4:Mn2+ nanoparticles and Au nanoparticles | fluorescence | CRP | 5–20 ng/mL | 2.5 ng/mL | [183] |

| colorimetric sandwich immunosensor | magnetic particles | colorimetric | insulin | 10 pM–1 nM | 10 pM | [197] |

| fluorescence competition immunoassay | photonic crystal | fluorescence | calcitonin gene-related peptide | 0.05–100 pg/mL | 0.05 pg/mL | [192] |

| turn-off biosensor based on polymethylmethacrylate opal photonic crystals | photonic crystal and AuNPs | fluorescence | carcinoembryonic antigen | 0.1–2.5 ng/mL | 0.1 ng/mL | [193] |

| * SPR-based optical biosensor system | - | optical | macrophage inflammatory protein-1α | n/a | 129 fM (1.0 pg/mL) in buffer 346 fM (2.7 pg/mL) in saliva | [198] |

| all-in-one microfluidic immunosensing device | magnetic beads | colorimetric | CRP, IL-6, procalcitonin | CRP: 1.75–28 ng/mL; IL-6 and PCT: 1.56–100 ng/mL | CRP: 0.295 ng/mL; IL-6: 0.400 ng/mL; PCT: 0.947 ng/mL | [194] |

| multiplex bioanalytical assay | Au nanorods | optical | Cyfra 21-1 and CA-125 | Cyfra 21-1: 0.496–48.4 ng/mL; CA-125: 5–320 U/mL | Cyfra 21-1: 0.84 ng/mL CA-125: 1.6 U/mL | [195] |

| wash-free bead-based immunoassay | magnetic beads and fluorescent beads | fluorescence | CRP, MMP-8 and MMP-9 and TIMP-1 | CRP: 20–140 mg/L; MMP-8: 0.47–30 ng/mL; MMP-9: 0.47–30 ng/mL; TIMP-1: 0.69–44 ng/mL | CRP: 2.1 ± 6.3 mg/L MMP-8: 0.24 ng/mL MMP-9: 0.38 ng/mL TIMP-1: 0.39 ng/mL | [196] |

| double-sided polished photonics crystal fiber-based SPR sensor | - | optical | cortisol | 1.2–30 ng/mL | 1.2 ng/mL | [178] |

| a photothermal biosensor | AuNPs coupled to a platinum detector | temperature change | CRP | 0.1–100 ng/mL | 0.1 ng/mL | [190] |

6. Future Perspectives

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AbdulRaheem, Y. Unveiling the Significance and Challenges of Integrating Prevention Levels in Healthcare Practice. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2023, 14, 21501319231186500. [Google Scholar]

- Arikat, S.; Saboor, M. Evolving role of clinical laboratories in precision medicine: A narrative review. J. Lab. Precis. Med. 2024, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broseghini, E.; Carosi, F.; Berti, M.; Compagno, S.; Ghelardini, A.; Fermi, M.; Querzoli, G.; Filippini, D.M. Salivary Gland Cancers in the Era of Molecular Analysis: The Role of Tissue and Liquid Biomarkers. Cancers 2025, 17, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alotaibi, M.; Honarvar Shakibaei Asli, B.; Khan, M. Non-invasive inspections: A review on methods and tools. Sensors 2021, 21, 8474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surdu, A.; Foia, L.G. Saliva as a Diagnostic Tool for Systemic Diseases-A Narrative Review. Medicina 2025, 61, 243. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, C.; Wu, Z.; Lin, C.; Chen, X.; Zou, Y.; Zhao, W.; Li, X.; Huang, G.; Xu, B.; Briganti, G.E. Nurturing the marriages of urinary liquid biopsies and nano-diagnostics for precision urinalysis of prostate cancer. Smart Med. 2023, 2, e20220020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Cao, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wen, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Z. Wearable tesla valve-based sweat collection device for sweat colorimetric analysis. Talanta 2022, 240, 123208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, S.; Makouei, S.; Abbasian, K.; Danishvar, S. Exhaled Breath Analysis (EBA): A Comprehensive Review of Non-Invasive Diagnostic Techniques for Disease Detection. Photonics 2025, 12, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Chen, X.; Fu, Y. Salivary analysis: An emerging paradigm for non-invasive healthcare diagnosis and monitoring. Interdiscip. Med. 2023, 1, e20230009. [Google Scholar]

- Aro, K.; Wei, F.; Wong, D.T.; Tu, M. Saliva Liquid Biopsy for Point-of-Care Applications. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Miočević, O.; Cole, C.R.; Laughlin, M.J.; Buck, R.L.; Slowey, P.D.; Shirtcliff, E.A. Quantitative Lateral Flow Assays for Salivary Biomarker Assessment: A Review. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellagambi, F.G.; Lomonaco, T.; Salvo, P.; Vivaldi, F.; Hangouët, M.; Ghimenti, S.; Biagini, D.; Di Francesco, F.; Fuoco, R.; Errachid, A. Saliva sampling: Methods and devices. An overview. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 124, 115781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, L.F. Human Saliva as a Diagnostic Specimen. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 1621S–1625S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornelas-González, A.; Ortiz-Martínez, M.; González-González, M.; Rito-Palomares, M. Enzymatic methods for salivary biomarkers detection: Overview and current challenges. Molecules 2021, 26, 7026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdul, N.S.; AlGhannam, S.M.; Almughaiseeb, A.A.; Bindawoad, F.A.; Alduraibi, S.M.; Shenoy, M. A review on salivary constituents and their role in diagnostics. Bioinformation 2022, 18, 1021–1028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Frenkel, E.S.; Ribbeck, K. Salivary mucins in host defense and disease prevention. J. Oral Microbiol. 2015, 7, 29759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcotte, H.; Lavoie, M.C. Oral Microbial Ecology and the Role of Salivary Immunoglobulin A. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1998, 62, 71–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokor-Bratić, M. [Clinical significance of analysis of immunoglobulin A levels in saliva]. Med. Pregl. 2000, 53, 164–168. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, I.; Bugshan, A. The role of salivary contents and modern technologies in the remineralization of dental enamel: A narrative review. F1000Research 2020, 9, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizawa, J.M.; Schafer, C.A.; Schafer, J.J.; Farrell, J.J.; Paster, B.J.; Wong, D.T.W. Salivary Biomarkers: Toward Future Clinical and Diagnostic Utilities. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 26, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greabu, M.; Battino, M.; Mohora, M.; Totan, A.; Didilescu, A.; Spinu, T.; Totan, C.; Miricescu, D.; Radulescu, R. Saliva--a diagnostic window to the body, both in health and in disease. J. Med. Life 2009, 2, 124–132. [Google Scholar]

- Constantin, V.; Luchian, I.; Goriuc, A.; Budala, D.G.; Bida, F.C.; Cojocaru, C.; Butnaru, O.-M.; Virvescu, D.I. Salivary Biomarkers Identification: Advances in Standard and Emerging Technologies. Oral 2025, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ou, Y.; Fan, K.; Liu, G. Salivary diagnostics: Opportunities and challenges. Theranostics 2024, 14, 6969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, P.; Crewther, B.; Cook, C.; Punyadeera, C.; Pandey, A.K. Sensing methods for stress biomarker detection in human saliva: A new frontier for wearable electronics and biosensing. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 5339–5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Tian, L.; Li, W.; Wang, K.; Yang, Q.; Lin, J.; Zhang, T.; Dong, B.; Wang, L. Recent Advances and Perspectives Regarding Paper-Based Sensors for Salivary Biomarker Detection. Chemosensors 2023, 11, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, V.; Beduk, T.; Khushaim, W.; Ceylan, A.E.; Timur, S.; Wolfbeis, O.S.; Salama, K.N. Electrochemical sensors targeting salivary biomarkers: A comprehensive review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2021, 135, 116164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raff, H.; Phillips, J.M. Bedtime salivary cortisol and cortisone by LC-MS/MS in healthy adult subjects: Evaluation of sampling time. J. Endocr. Soc. 2019, 3, 1631–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasco, V.; Bima, C.; Geranzani, A.; Giannelli, J.; Marinelli, L.; Bona, C.; Cambria, V.; Berton, A.M.; Prencipe, N.; Ghigo, E. Morning serum cortisol level predicts central adrenal insufficiency diagnosed by insulin tolerance test. Neuroendocrinology 2021, 111, 1238–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvam Hellan, K.; Lyngstad, M.; Methlie, P.; Løvås, K.; Husebye, E.S.; Ueland, G.Å. Utility of salivary cortisol and cortisone in the diagnostics of adrenal insufficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 110, 1218–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bäcklund, N.; Brattsand, G.; Israelsson, M.; Ragnarsson, O.; Burman, P.; Edén Engström, B.; Høybye, C.; Berinder, K.; Wahlberg, J.; Olsson, T. Reference intervals of salivary cortisol and cortisone and their diagnostic accuracy in Cushing’s syndrome. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 182, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.Y.; Park, S.; Lee, C.; Ku, E.J.; Lee, S.; Kim, K.-A.; Kim, S.W.; Rhee, Y.; Lim, J.S.; Chung, C.H. Clinical Utility of Salivary Steroid Profiling for the Differential Diagnosis of Adrenal Diseases. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, dgaf499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Z.; Wemm, S.E.; Han, L.; Spink, D.C.; Wulfert, E. Noninvasive determination of human cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2019, 411, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, C.R.; Moraes, S.M.; Buzalaf, M.A.R. Saliva-based Hormone Diagnostics: Advances, applications, and future perspectives. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2025, 25, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Qassem, M.; Kyriacou, P.A. Measuring stress: A review of the current cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) measurement techniques and considerations for the future of mental health monitoring. Stress 2023, 26, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaza-Guzmán, D.; Cardona-Vélez, N.; Gaviria-Correa, D.; Martínez-Pabón, M.; Castaño-Granada, M.; Tobón-Arroyave, S. Association study between salivary levels of interferon (IFN)-gamma, interleukin (IL)-17, IL-21, and IL-22 with chronic periodontitis. Arch. Oral Biol. 2015, 60, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, G.; Giudice, A.L.; Polizzi, A.; Alibrandi, A.; Murabito, P.; Indelicato, F. Identification of the different salivary Interleukin-6 profiles in patients with periodontitis: A cross-sectional study. Arch. Oral Biol. 2021, 122, 104997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiamulera, M.M.A.; Zancan, C.B.; Remor, A.P.; Cordeiro, M.F.; Gleber-Netto, F.O.; Baptistella, A.R. Salivary cytokines as biomarkers of oral cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shi, Q.; Yang, S.; Wang, Q.; Xu, J.; Guo, B. The relationship between levels of salivary and serum interleukin-6 and oral lichen planus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2017, 148, 743–749.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melguizo-Rodríguez, L.; Costela-Ruiz, V.J.; Manzano-Moreno, F.J.; Ruiz, C.; Illescas-Montes, R. Salivary biomarkers and their application in the diagnosis and monitoring of the most common oral pathologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Arthur, C.P.; Ciferri, C.; Matsumoto, M.L. Structure of the secretory immunoglobulin A core. Science 2020, 367, 1008–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aase, A.; Sommerfelt, H.; Petersen, L.B.; Bolstad, M.; Cox, R.J.; Langeland, N.; Guttormsen, A.; Steinsland, H.; Skrede, S.; Brandtzaeg, P. Salivary IgA from the sublingual compartment as a novel noninvasive proxy for intestinal immune induction. Mucosal Immunol. 2016, 9, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauch, R.M.; Rossi, C.L.; Nolasco da Silva, M.T.; Bianchi Aiello, T.; Ribeiro, J.D.; Ribeiro, A.F.; Høiby, N.; Levy, C.E. Secretory IgA-mediated immune response in saliva and early detection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the lower airways of pediatric cystic fibrosis patients. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2019, 208, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Ramírez, S.; Sosa-Hernández, V.A.; Cervantes-Díaz, R.; Carrillo-Vázquez, D.A.; Meza-Sánchez, D.E.; Núñez-Álvarez, C.; Torres-Ruiz, J.; Gómez-Martín, D.; Maravillas-Montero, J.L. Salivary IgA subtypes as novel disease biomarkers in systemic lupus erythematosus. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1080154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, H.R.; Zavattaro, E.; Abdolahnejad, A.; Lopez-Jornet, P.; Omidpanah, N.; Sharifi, R.; Sadeghi, M.; Shooriabi, M.; Safaei, M. Serum and salivary IgA, IgG, and IgM levels in oral lichen planus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Medicina 2018, 54, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Nayak, M.T.; Sunitha, J.; Dawar, G.; Sinha, N.; Rallan, N.S. Correlation of salivary glucose level with blood glucose level in diabetes mellitus. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2017, 21, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.; Liao, Z.; Wang, S.; Liu, W. Correlations of salivary and blood glucose levels among six saliva collection methods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ros, P.; Navarro-Flores, E.; Julián-Rochina, I.; Martínez-Arnau, F.M.; Cauli, O. Changes in salivary amylase and glucose in diabetes: A scoping review. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiongco, R.E.G.; Arceo, E.S.; Rivera, N.S.; Flake, C.C.D.; Policarpio, A.R. Estimation of salivary glucose, amylase, calcium, and phosphorus among non-diabetics and diabetics: Potential identification of non-invasive diagnostic markers. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2019, 13, 2601–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, N.; Nater, U.M. Salivary alpha-amylase as a biomarker of stress in behavioral medicine. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2020, 27, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erta, G.; Gersone, G.; Jurka, A.; Tretjakovs, P. Salivary α-Amylase as a Metabolic Biomarker: Analytical Tools, Challenges, and Clinical Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathyapalan, T.; Al-Qaissi, A.; Kilpatrick, E.S.; Dargham, S.R.; Adaway, J.; Keevil, B.; Atkin, S.L. Salivary testosterone measurement in women with and without polycystic ovary syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Titman, A.; Bright, O.; Dliso, S.; Shantsila, A.; Lip, G.Y.; Adaway, J.; Keevil, B.; Hawcutt, D.B.; Blair, J. Salivary Testosterone, Androstenedione and 11-Oxygenated 19-Carbon Concentrations Differ by Age and Sex in Children. Clin. Endocrinol. 2025, 103, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvi, S.N.; Hammami, M.M. An improved method for measurement of testosterone in human plasma and saliva by ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2020, 11, 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Sakkas, D.; Howles, C.M.; Atkinson, L.; Borini, A.; Bosch, E.A.; Bryce, C.; Cattoli, M.; Copperman, A.B.; de Bantel, A.F.; French, B. A multi-centre international study of salivary hormone oestradiol and progesterone measurements in ART monitoring. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2021, 42, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiers, T.; Dielen, C.; Somers, S.; Kaufman, J.-M.; Gerris, J. Salivary estradiol as a surrogate marker for serum estradiol in assisted reproduction treatment. Clin. Biochem. 2017, 50, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieder, J.K.; Darabos, K.; Weierich, M.R. Estradiol and women’s health: Considering the role of estradiol as a marker in behavioral medicine. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2020, 27, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cando, L.F.T.; Dispo, M.D.; Tantengco, O.A.G. Salivary progesterone as a biomarker for predicting preterm birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2022, 88, e13628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, A.; Carpenter, G.; So, P.-W. Salivary metabolomics: From diagnostic biomarker discovery to investigating biological function. Metabolites 2020, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidopoulou, S.; Makedou, K.; Kourti, A.; Gkeka, I.; Karakostas, P.; Pikilidou, M.; Tolidis, K.; Kalfas, S. Vitamin D and LL-37 in Serum and Saliva: Insights into Oral Immunity. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reviansyah, F.H.; Ristin, A.D.; Rauf, A.A.; Sepirasari, P.D.; Alim, F.N.; Nur, Y.; Takarini, V.; Yusuf, M.; Aripin, D.; Susilawati, S. Noninvasive detection of alpha-amylase in saliva using screen-printed carbon electrodes: A promising biomarker for clinical oral diagnostics. Med. Devices Evid. Res. 2025, 18, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majster, M.; Almer, S.; Malmqvist, S.; Johannsen, A.; Lira-Junior, R.; Boström, E.A. Salivary calprotectin and neutrophils in inflammatory bowel disease in relation to oral diseases. Oral Dis. 2025, 31, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallina, S.; Di Mauro, M.; D’Amico, M.A.; D’Angelo, E.; Sablone, A.; Di Fonso, A.; Bascelli, A.; Izzicupo, P.; Di Baldassarre, A. Salivary chromogranin A, but not α-amylase, correlates with cardiovascular parameters during high-intensity exercise. Clin. Endocrinol. 2011, 75, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budala, D.G.; Luchian, I.; Virvescu, D.I.; Tudorici, T.; Constantin, V.; Surlari, Z.; Butnaru, O.; Bosinceanu, D.N.; Bida, C.; Hancianu, M. Salivary Biomarkers as a Predictive Factor in Anxiety, Depression, and Stress. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonelli, G.; Ceccato, F.; Artusi, C.; Marinova, M.; Plebani, M. Salivary cortisol and cortisone by LC-MS/MS: Validation, reference intervals and diagnostic accuracy in Cushing’s syndrome. Clin. Chim. Acta Int. J. Clin. Chem. 2015, 451 Pt B, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perogamvros, I.; Keevil, B.G.; Ray, D.W.; Trainer, P.J. Salivary cortisone is a potential biomarker for serum free cortisol. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 4951–4958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramdzan, A.N.; Almeida, M.I.G.S.; McCullough, M.J.; Segundo, M.A.; Kolev, S.D. Determination of salivary cotinine as tobacco smoking biomarker. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2018, 105, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, M.; Garg, A.; Yadav, P.; Jha, K.; Handa, S. Diagnostic Methods for Detection of Cotinine Level in Tobacco Users: A Review. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. JCDR 2016, 10, ZE04–ZE06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartaglia, F.C.; Khijmatgar, S.; Del Fabbro, M.; Maspero, C.; Caprioglio, A.; Amati, F.; Sozzi, D. Procalcitonin and C-reactive Protein as Alternative Salivary Biomarkers in Infection and Inflammatory Diseases Detection and Patient Care: A Scoping Review. Adv. Biomark. Sci. Technol. 2025, 7, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pay, J.B.; Shaw, A.M. Towards salivary C-reactive protein as a viable biomarker of systemic inflammation. Clin. Biochem. 2019, 68, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabregat-Safont, D.; Alechaga, É.; Haro, N.; Gomez-Gomez, À.; Velasco, E.R.; Nabás, J.F.; Andero, R.; Pozo, O.J. Towards the non-invasive determination of estradiol levels: Development and validation of an LC-MS/MS assay for quantification of salivary estradiol at sub-pg/mL level. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1331, 343313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan-Dawood, F.S.; Choe, J.K.; Dawood, M.Y. Salivary and plasma bound and “free” testosterone in men and women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1984, 148, 442–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lood, Y.; Aardal, E.; Ahlner, J.; Ärlemalm, A.; Carlsson, B.; Ekman, B.; Wahlberg, J.; Josefsson, M. Determination of testosterone in serum and saliva by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry: An accurate and sensitive method applied on clinical and forensic samples. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2021, 195, 113823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.; Saha, S.; Mohanty, S.; Sharma, N.; Rath, S. Salivary dynamics: Assessing pH, glucose levels, and oral microflora in diabetic and non-diabetic individual. IP Int. J. Med. Microbiol. Trop. Dis. 2024, 10, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabasa, V.; Seheri, M.L.; Magwira, C.A. Expression of salivary hepcidin and its inducer, interleukin 6 as well as type I interferons are significantly elevated in infants with poor oral rotavirus vaccine take in South Africa. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1517893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.-N.; Yang, Y.-Z.; Feng, Y.-Z. Serum and salivary ferritin and Hepcidin levels in patients with chronic periodontitis and type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Oral Health 2018, 18, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiei, H.; Little, J.P. Saliva insulin concentration following ingestion of a standardized mixed meal tolerance test: Influence of obesity status. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2025, 50, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaedicke, K.M.; Preshaw, P.M.; Taylor, J.J. Salivary cytokines as biomarkers of periodontal diseases. Periodontology 2000 2016, 70, 164–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Liu, B.; Gao, R.; Su, L.; Su, Y. TiO2/CuInS2-sensitized structure for sensitive photoelectrochemical immunoassay of cortisol in saliva. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2022, 26, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossini, E.L.; Milani, M.I.; Lima, L.S.; Pezza, H.R. Paper microfluidic device using carbon dots to detect glucose and lactate in saliva samples. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 248, 119285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraboschi, P.; Ciceri, S. Applications of Lysozyme, an Innate Immune Defense Factor, as an Alternative Antibiotic. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomašovský, R.; Opetová, M.; Polačková, M.; Maráková, K. Analysis of lysozyme in human saliva by CE-UV: A new simple, fast, and reliable method. Talanta 2026, 297, 128605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeuse, J.J.; Calaprice, C.; Huyghebaert, L.C.; Rechchad, M.; Peeters, S.; Cavalier, E.; Le Goff, C. Development and validation of an Ultrasensitive LC-MS/MS method for the quantification of melatonin in human saliva. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2023, 34, 1056–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundberg, I.; Rasmusson, A.J.; Ramklint, M.; Just, D.; Ekselius, L.; Cunningham, J.L. Daytime melatonin levels in saliva are associated with inflammatory markers and anxiety disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2020, 112, 104514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salarić, I.; Karmelić, I.; Lovrić, J.; Baždarić, K.; Rožman, M.; Čvrljević, I.; Zajc, I.; Brajdić, D.; Macan, D. Salivary melatonin in oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maged, A.M.; Mohesen, M.; Elhalwagy, A.; Abdelhafiz, A. Salivary progesterone and cervical length measurement as predictors of spontaneous preterm birth. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015, 28, 1147–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guduguntla, P.; Guttikonda, V.R. Estimation of serum pyruvic acid levels in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2020, 24, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, A.; Bhat, M.; Prasad, K.; Trivedi, D.; Acharya, S. Estimation of Pyruvic acid in serum and saliva among healthy and potentially malignant disorder subjects–a stepping stone for cancer screening? J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2015, 7, e462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, D.S.-Q.; Koh, G.C.-H. The use of salivary biomarkers in occupational and environmental medicine. Occup. Environ. Med. 2007, 64, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostinov, M.; Svitich, O.; Chuchalin, A.; Abramova, N.; Osiptsov, V.; Khromova, E.; Pakhomov, D.; Tatevosov, V.; Vlasenko, A.; Gainitdinova, V. Changes in nasal, pharyngeal and salivary secretory IgA levels in patients with COVID-19 and the possibility of correction of their secretion using combined intranasal and oral administration of a pharmaceutical containing antigens of opportunistic microorganisms. Drugs Context 2023, 12, 2022-10-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brierly, G.; Celentano, A.; Breik, O.; Moslemivayeghan, E.; Patini, R.; McCullough, M.; Yap, T. Tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancers 2023, 15, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, H.R.; Ramezani, M.; Mahmoudiahmadabadi, M.; Omidpanah, N.; Sadeghi, M. Salivary and serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in oral lichen planus: A systematic review and meta-analysis study. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2017, 124, e183–e189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, M.W.; Black, L.J.; Hart, P.H.; Jones, A.P.; Palmer, D.J.; Siafarikas, A.; Lucas, R.M.; Gorman, S. The challenges of developing and optimising an assay to measure 25-hydroxyvitamin D in saliva. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 194, 105437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assad, D.X.; Mascarenhas, E.C.P.; de Lima, C.L.; de Toledo, I.P.; Chardin, H.; Combes, A.; Acevedo, A.C.; Guerra, E.N.S. Salivary metabolites to detect patients with cancer: A systematic review. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 25, 1016–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, S.; Sugimoto, M.; Kitabatake, K.; Sugano, A.; Nakamura, M.; Kaneko, M.; Ota, S.; Hiwatari, K.; Enomoto, A.; Soga, T. Identification of salivary metabolomic biomarkers for oral cancer screening. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfermeijer, M.; van Winden, L.J.; Starreveld, D.E.; Razab-Sekh, S.; van Faassen, M.; Bleiker, E.M.; van Rossum, H.H. An LC-MS/MS-based method for the simultaneous quantification of melatonin, cortisol and cortisone in saliva. Anal. Biochem. 2024, 689, 115496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sembler-Møller, M.L.; Belstrøm, D.; Locht, H.; Pedersen, A.M.L. Proteomics of saliva, plasma, and salivary gland tissue in Sjögren’s syndrome and non-Sjögren patients identify novel biomarker candidates. J. Proteom. 2020, 225, 103877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.-Y.; Kim, J.-W.; Kim, H.-A.; Suh, C.-H. Salivary biomarkers in patients with Sjögren’s Syndrome—A systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyvärinen, E.; Solje, E.; Vepsäläinen, J.; Kullaa, A.; Tynkkynen, T. Salivary metabolomics in the diagnosis and monitoring of neurodegenerative dementia. Metabolites 2023, 13, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vining, R.F.; McGinley, R.A.; McGinley, R.A. Hormones in Saliva. CRC Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 1986, 23, 95–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafar, A.; Rico, P.; Işık, A.; Jontell, M.; Çevik-Aras, H. Quantitative detection of epidermal growth factor and interleukin-8 in whole saliva of healthy individuals. J. Immunol. Methods 2014, 408, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, F.; Mozaffari, H.R.; Tavasoli, J.; Zavattaro, E.; Imani, M.M.; Sadeghi, M. Evaluation of serum and salivary interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 levels in oral squamous cell carcinoma patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2019, 39, 727–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, G.S.; Mathews, S.T. Saliva as a non-invasive diagnostic tool for inflammation and insulin-resistance. World J. Diabetes 2014, 5, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredolini, C.; Byström, S.; Pin, E.; Edfors, F.; Tamburro, D.; Iglesias, M.J.; Häggmark, A.; Hong, M.-G.; Uhlen, M.; Nilsson, P. Immunocapture strategies in translational proteomics. Expert Rev. Proteom. 2016, 13, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karachaliou, C.-E.; Koukouvinos, G.; Goustouridis, D.; Raptis, I.; Kakabakos, S.; Petrou, P.; Livaniou, E. Cortisol Immunosensors: A literature review. Biosensors 2023, 13, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilea, A.; Andrei, V.; Feurdean, C.N.; Băbțan, A.-M.; Petrescu, N.B.; Câmpian, R.S.; Boșca, A.B.; Ciui, B.; Tertiș, M.; Săndulescu, R. Saliva, a magic biofluid available for multilevel assessment and a mirror of general health—A systematic review. Biosensors 2019, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, S.; Samara, M.; Ampadi Ramachandran, R.; Gosh, S.; George, H.; Wang, R.; Pesavento, R.P.; Mathew, M.T. A review on saliva-based health diagnostics: Biomarker selection and future directions. Biomed. Mater. Devices 2024, 2, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, T.; Matos Pires, N.M.; Yang, Z.; Jiang, Z. Advances in electrochemical biosensors based on nanomaterials for protein biomarker detection in saliva. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2205429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slowey, P.D. Saliva Collection Devices and Diagnostic Platforms. In Advances in Salivary Diagnostics; Streckfus, C.F., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 33–61. [Google Scholar]

- Poll, E.-M.; Kreitschmann-Andermahr, I.; Langejuergen, Y.; Stanzel, S.; Gilsbach, J.M.; Gressner, A.; Yagmur, E. Saliva collection method affects predictability of serum cortisol. Clin. Chim. Acta 2007, 382, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durdiaková, J.; Fábryová, H.; Koborová, I.; Ostatníková, D.; Celec, P. The effects of saliva collection, handling and storage on salivary testosterone measurement. Steroids 2013, 78, 1325–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, R.; Heavey, S.; Graham, D.G.; Wellman, R.; Khan, S.; Thrumurthy, S.; Simpson, B.S.; Baker, T.; Jevons, S.; Ariza, J. An optimised saliva collection method to produce high-yield, high-quality RNA for translational research. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polson, C.; Sarkar, P.; Incledon, B.; Raguvaran, V.; Grant, R. Optimization of protein precipitation based upon effectiveness of protein removal and ionization effect in liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B 2003, 785, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Zhai, Q.; Zhang, H.; Ji, P.; Chen, C.; Zhang, H. Comparisons of different extraction methods and solvents for saliva samples. Metabolomics 2024, 20, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, M.G. Automatically Signal-Enhanced Lateral Flow Immunoassay for Ultrasensitive Salivary Cortisol Detection. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 2707–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, P.; Arredondo, M.; Pineda, N.; Campoy, J.; Acevedo, R.; Olvera, X.; Romero, D.; Batina, N. New insights into the construction of a µPAD for cortisol detection in human saliva samples freshly extracted without previous treatment. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2025, 29, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.-K.; Kim, J.-W.; Kim, J.-M.; Kim, M.-G. High sensitive and broad-range detection of cortisol in human saliva using a trap lateral flow immunoassay (trapLFI) sensor. Analyst 2018, 143, 3883–3889. [Google Scholar]

- Scarsi, A.; Pedone, D.; Pompa, P.P. A dual-color plasmonic immunosensor for salivary cortisol measurement. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.-K.; Kim, K.; Park, J.; Jang, H.; Kim, M.-G. Advanced trap lateral flow immunoassay sensor for the detection of cortisol in human bodily fluids. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Kwon, J.; Shin, S.; Eun, Y.-G.; Shin, J.H.; Lee, G.-J. Optimization of Saliva Collection and Immunochromatographic Detection of Salivary Pepsin for Point-of-Care Testing of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux. Sensors 2020, 20, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panfilova, E. Development of a Prototype Lateral Flow Immunoassay of Cortisol in Saliva for Daily Monitoring of Stress. Biosensors 2021, 11, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skirda, A.M.; Orlov, A.V.; Malkerov, J.A.; Znoyko, S.L.; Rakitina, A.S.; Nikitin, P.I. Enhanced Analytical Performance in CYFRA 21-1 Detection Using Lateral Flow Assay with Magnetic Bioconjugates: Integration and Comparison of Magnetic and Optical Registration. Biosensors 2024, 14, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Nardo, F.; Cavalera, S.; Baggiani, C.; Giovannoli, C.; Anfossi, L. Direct vs Mediated Coupling of Antibodies to Gold Nanoparticles: The Case of Salivary Cortisol Detection by Lateral Flow Immunoassay. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 32758–32768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apilux, A.; Rengpipat, S.; Suwanjang, W.; Chailapakul, O. Development of competitive lateral flow immunoassay coupled with silver enhancement for simple and sensitive salivary cortisol detection. EXCLI J. 2018, 17, 1198–1209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Choi, C.W.; Hong, D.; Kim, M.-G. Light source-free smartphone detection of salivary cortisol via colorimetric lateral flow immunoassay using a photoluminescent film. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2025, 271, 116971. [Google Scholar]

- Zangheri, M.; Cevenini, L.; Anfossi, L.; Baggiani, C.; Simoni, P.; Di Nardo, F.; Roda, A. A simple and compact smartphone accessory for quantitative chemiluminescence-based lateral flow immunoassay for salivary cortisol detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 64, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upaassana, V.T.; Setty, S.; Jang, H.; Ghosh, S.; Ahn, C. On-site analysis of cortisol in saliva based on microchannel lateral flow assay (mLFA) on polymer lab-on-a-chip (LOC). Biomed. Microdevices 2025, 27, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Huang, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Lin, Z.; Chen, T. A rapid and highly sensitive fluorescence immunochromatographic test strip for pepsin detection in human hypopharyngeal saliva. Anal. Methods 2025, 17, 1074–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; You, M.; Li, Z.; Cao, L.; Xu, F.; Li, F.; Li, A. Upconversion nanoparticles-based lateral flow immunoassay for point-of-care diagnosis of periodontitis. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 334, 129673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.-K.; Akbali, B.; Sham, T.-T.; Haworth-Duff, A.; Blair, J.C.; Smith, B.L.; Sricharoen, N.; Lima, C.; Chen, T.-Y.; Huang, C.-H.; et al. SERS-based lateral flow immunoassay utilising plasmonic nanoparticle clusters for ultra-sensitive detection of salivary cortisol. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 19656–19665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzi, L.; Maier, T.; Ertl, P.; Hainberger, R. Quantitative detection of C-reactive protein in human saliva using an electrochemical lateral flow device. Biosens. Bioelectron. X 2022, 10, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandhakumar, P.; Muñoz San Martín, C.; Arévalo, B.; Ding, S.; Lunker, M.; Vargas, E.; Djassemi, O.; Campuzano, S.; Wang, J. Redox Cycling Amplified Electrochemical Lateral-Flow Immunoassay: Toward Decentralized Sensitive Insulin Detection. ACS Sens. 2023, 8, 3892–3901. [Google Scholar]

- Yee, E.H.; Lathwal, S.; Shah, P.P.; Sikes, H.D. Detection of Biomarkers of Periodontal Disease in Human Saliva Using Stabilized, Vertical Flow Immunoassays. ACS Sens. 2017, 2, 1589–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinyua, D.M.; Memeu, D.M.; Mugo Mwenda, C.N.; Ventura, B.D.; Velotta, R. Advancements and Applications of Lateral Flow Assays (LFAs): A Comprehensive Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atta, S.; Zhao, Y.; Li, J.Q.; Vo-Dinh, T. Dual-Modal Colorimetric and Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS)-Based Lateral Flow Immunoassay for Ultrasensitive Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Using a Plasmonic Gold Nanocrown. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 4783–4790. [Google Scholar]

- Abarintos, V.; Piper, A.; Merkoci, A. Electrochemical lateral flow assays: A new frontier for rapid and quantitative biosensing. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2025, 54, 101750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Tu, F.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Liu, Z. A time-resolved fluorescent microsphere-lateral flow immunoassay strip assay with image visual analysis for quantitative detection of Helicobacter pylori in saliva. Talanta 2023, 256, 124317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizian, P.; Casals-Terré, J.; Guerrero-SanVicente, E.; Grinyte, R.; Ricart, J.; Cabot, J.M. Coupling Capillary-Driven Microfluidics with Lateral Flow Immunoassay for Signal Enhancement. Biosensors 2023, 13, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, A.; Brasiunas, B.; Blazevic, K.; Kausaite-Minkstimiene, A.; Ramanaviciene, A. Ultra-sensitive electrochemical immunosensors for clinically important biomarker detection: Prospects, opportunities, and global trends. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2024, 46, 101524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Guan, C.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Han, G. Advances in Electrochemical Biosensors for the Detection of Common Oral Diseases. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2025, 55, 775–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Zhang, F.; Xu, W.; Deng, Z.; Tang, Z.; Huang, J. Advancements and Trends in Electrochemical Biosensors for Saliva-Based Diagnosis of Oral Diseases: A Bibliometric Analysis (2000–2023). Int. Dent. J. 2025, 75, 100840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Dighe, K.; Wang, Z.; Srivastava, I.; Daza, E.; Schwartz-Dual, A.S.; Ghannam, J.; Misra, S.K.; Pan, D. Detection of prostate specific antigen (PSA) in human saliva using an ultra-sensitive nanocomposite of graphene nanoplatelets with diblock-co-polymers and Au electrodes. Analyst 2018, 143, 1094–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-López, C.; García-Rodrigo, L.; Sánchez-Tirado, E.; González-Cortés, A.; Agüí, L.; Yáñez-Sedeño, P.; Pingarrón, J.M. Nanocellulose-modified electrodes for simultaneous biosensing of microbiome-related oral diseases biomarkers. Microchim. Acta 2025, 192, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-López, C.; García-Rodrigo, L.; Sánchez-Tirado, E.; Agüí, L.; González-Cortés, A.; Yáñez-Sedeño, P.; Pingarrón, J.M. Cerium dioxide-based nanostructures as signal nanolabels for current detection in the immunosensing determination of salivary myeloperoxidase. Microchem. J. 2024, 201, 110505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divyamani, M.P.; Hegde, S.N.; Naveen Kumar, S.K.; Dharma Guru Prasad, M.P. ZnO Nanoparticle-Based Electrochemical Immunosensor for One-Step Quantification of Cortisol in Saliva. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 38303–38310. [Google Scholar]

- Vasu, S.; Verma, D.; Souraph S, O.S.; Anki Reddy, K.; Packirisamy, G.; S, U.K. In Situ Ag-Seeded Lamellar Ti3C2 Nanosheets: An Electroactive Interface for Noninvasive Diagnosis of Oral Carcinoma via Salivary TNF-α Sensing. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2025, 8, 420–434. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, D.; Fu, Q.; Gao, R.; Su, L.; Su, Y.; Liu, B. Signal-on photoelectrochemical immunoassay for salivary cortisol based on silver nanoclusters-triggered ion-exchange reaction with CdS quantum dots. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022, 414, 3033–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaki, S.; Wakida, S.-i.; Saito, M.; Tamiya, E. Towards On-site Determination of Secretory IgA in Artificial Saliva with Gold-Linked Electrochemical Immunoassay (GLEIA) Using Portable Potentiostat and Disposable Printed Electrode. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2021, 193, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-López, C.; Garcia-Rodrigo, L.; Sánchez-Tirado, E.; Agüí, L.; González-Cortés, A.; Yáñez-Sedeño, P.; Pingarrón, J.M. Electrochemical immunoplatform for the determination of multiple salivary biomarkers of oral diseases related to microbiome dysbiosis. Bioelectrochemistry 2025, 161, 108816. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, C.; Ye, H.; Jie, H.; Qiu, Y.; Li, N.; Zhuang, J. Biphasic electrochemical immunoassay based on tyramine-DNA cascade signal amplification for detection of interleukin-8 in human saliva samples. Microchem. J. 2025, 212, 113240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, T.W.; Zhang, X.; Punyadeera, C.; Henry, C.S. Electrochemical immunosensor for the quantification of galectin-3 in saliva. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2024, 400, 134811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Zhang, J.; Gao, N.; Huo, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, T.; Zhang, X.; Simayijiang, H.; Yan, J. Rapid and visual detection of specific bacteria for saliva and vaginal fluid identification with the lateral flow dipstick strategy. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2023, 137, 1853–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhakypbekova, A.; Bekmurzayeva, A.; Blanc, W.; Tosi, D. Parallel fiber-optic semi-distributed biosensor for detection of IL-6 and IL-8 cancer biomarkers in saliva at femtomolar limit. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 189, 113139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Misra, S.K.; Wang, Z.; Daza, E.; Schwartz-Duval, A.S.; Kus, J.M.; Pan, D.; Pan, D. Paper-Based Analytical Biosensor Chip Designed from Graphene-Nanoplatelet-Amphiphilic-diblock-co-Polymer Composite for Cortisol Detection in Human Saliva. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 2107–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Dighe, K.; Wang, Z.; Srivastava, I.; Schwartz-Duval, A.S.; Misra, S.K.; Pan, D. Electrochemical-digital immunosensor with enhanced sensitivity for detecting human salivary glucocorticoid hormone. Analyst 2019, 144, 1448–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arévalo, B.; Serafín, V.; Beltrán-Sánchez, J.F.; Aznar-Poveda, J.; López-Pastor, J.A.; García-Sánchez, A.J.; García-Haro, J.; Campuzano, S.; Yañez-Sedeño, P.; Pingarrón, J.M. Simultaneous determination of four fertility-related hormones in saliva using disposable multiplexed immunoplatforms coupled to a custom-designed and field-portable potentiostat. Anal. Methods 2021, 13, 3471–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafín, V.; Arévalo, B.; Martínez-García, G.; Aznar-Poveda, J.; Lopez-Pastor, J.A.; Beltrán-Sánchez, J.F.; Garcia-Sanchez, A.J.; Garcia-Haro, J.; Campuzano, S.; Yáñez-Sedeño, P.; et al. Enhanced determination of fertility hormones in saliva at disposable immunosensing platforms using a custom designed field-portable dual potentiostat. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 299, 126934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraket, A.; Ghedir, E.K.; Zine, N.; Jaffrezic-Renault, N.; Aarfane, A.; Nasrellah, H.; Belhora, F.; Bonet, F.P.; Bausells, J.; Errachid, A. Electrochemical Immunosensor Prototype for N-Terminal Natriuretic Peptide Detection in Human Saliva: Heart Failure Biomedical Application. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, N.O.; Calegaro, M.L.; Mattoso, L.H.C.; Machado, S.A.S.; Oliveira, O.N., Jr.; Raymundo-Pereira, P.A. Low-Cost, Disposable Biosensor for Detection of the Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Biomarker in Noninvasively Collected Saliva toward Diagnosis of Mental Disorders. ACS Polym. Au 2025, 5, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetrivel, C.; Sivarasan, G.; Durairaj, K.; Ragavendran, C.; Kamaraj, C.; Karthika, S.; Lo, H.-M. MoS2-ZnO Nanocomposite Mediated Immunosensor for Non-Invasive Electrochemical Detection of IL8 Oral Tumor Biomarker. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Simone, S.G.; Carvalho, J. Electro Sensors Based on Quantum Dots and Their Applications in Diagnostic Medicine. In New Advances in Biosensing; Karakuş, S., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; Sui, J.; Javanmard, M. A two-minute assay for electronic quantification of antibodies in saliva enabled through a reusable microfluidic multi-frequency impedance cytometer and machine learning analysis. Biomed. Microdevices 2023, 25, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, P.; Wang, J.; Mao, H.; Zhou, L.; Wu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Sun, T.; Hui, J.; Ma, G. AuNP/Magnetic Bead-Enhanced Electrochemical Sensor Toward Dual Saliva Alzheimer’s Biomarkers Detection. Sensors 2025, 25, 4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Li, G. Electrochemical biosensing methods for analysis of trace biomarkers: A review. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, S.; Ju, H. Electrochemiluminescence nanoemitters for immunoassay of protein biomarkers. Bioelectrochemistry 2023, 149, 108281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J. Sensitive Detection of Biomarker in Gingival Crevicular Fluid Based on Enhanced Electrochemiluminescence by Nanochannel-Confined Co3O4 Nanocatalyst. Biosensors 2025, 15, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tofighi, F.B.; Saadati, A.; Kholafazad-kordasht, H.; Farshchi, F.; Hasanzadeh, M.; Samiei, M. Electrochemical immunoplatform to assist in the diagnosis of oral cancer through the determination of CYFRA 21.1 biomarker in human saliva samples: Preparation of a novel portable biosensor toward non-invasive diagnosis of oral cancer. J. Mol. Recognit. 2021, 34, e2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.E.F.; Pereira, A.C.; Resende, M.A.C.; Ferreira, L.F. Disposable Voltammetric Immunosensor for Determination and Quantification of Biomarker CA 15-3 in Biological Specimens. Analytica 2024, 5, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, T.W.; Decsi, D.B.; Punyadeera, C.; Henry, C.S. Saliva-based microfluidic point-of-care diagnostic. Theranostics 2023, 13, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Valdepeñas Montiel, V.; Sempionatto, J.R.; Vargas, E.; Bailey, E.; May, J.; Bulbarello, A.; Düsterloh, A.; Matusheski, N.; Wang, J. Decentralized vitamin C & D dual biosensor chip: Toward personalized immune system support. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 194, 113590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, E.; Teymourian, H.; Tehrani, F.; Eksin, E.; Sánchez-Tirado, E.; Warren, P.; Erdem, A.; Dassau, E.; Wang, J. Enzymatic/Immunoassay Dual-Biomarker Sensing Chip: Towards Decentralized Insulin/Glucose Detection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 6376–6379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moukri, N.; Juska, V.; Patella, B.; Giuffrè, M.R.; Pace, E.; Cipollina, C.; O’Riordan, A.; Inguanta, R. Multiplex on-chip immunosensor for advancing inflammation biomarkers monitoring. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 445, 138604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewarsa, P.; Schenkel, M.S.; Rahn, K.L.; Laiwattanapaisal, W.; Henry, C.S. Improving design features and air bubble manipulation techniques for a single-step sandwich electrochemical ELISA incorporating commercial electrodes into capillary-flow driven immunoassay devices. Analyst 2024, 149, 2034–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzaracchio, V.; Arduini, F. Smart microfluidic devices integrated in electrochemical point-of-care platforms for biomarker detection in biological fluids. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Xu, N.; Men, H.; Li, S.; Lu, Y.; Low, S.S.; Li, X.; Zhu, L.; Cheng, C.; Xu, G.; et al. Salivary Cortisol Determination on Smartphone-Based Differential Pulse Voltammetry System. Sensors 2020, 20, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamiya, E.; Osaki, S.; Tsuchihashi, T.; Ushijima, H.; Tsukinoki, K. Point-of-Care Diagnostic Biosensors to Monitor Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing IgG/sIgA Antibodies and Antioxidant Activity in Saliva. Biosensors 2023, 13, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, F.; Yue, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, H.S. Advancing biosensors with machine learning. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 3346–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellassai, N.; D’Agata, R.; Jungbluth, V.; Spoto, G. Surface plasmon resonance for biomarker detection: Advances in non-invasive cancer diagnosis. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Pal, S.; Prajapati, Y.K. Dual Polished-Based Dual Core LRSPR Sensor for Stress Monitoring Using Cortisol Biomarker in Human Saliva. Sens. Imaging 2025, 26, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, M.V.; López-Martínez, E.; Berganza-Granda, J.; Goni-de-Cerio, F.; Cortajarena, A.L. Biomarker sensing platforms based on fluorescent metal nanoclusters. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3, 1331–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehtesabi, H. Carbon nanomaterials for salivary-based biosensors: A review. Mater. Today Chem. 2020, 17, 100342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, N.; Qin, D.; Chen, X.; Yang, H.; Hua, F. The application of quantum dots in dental and oral medicine: A scoping review. J. Dent. 2025, 153, 105536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indongo, G.; Abraham, M.K.; Rajeevan, G.; Kala, A.B.; Dhahir, D.M.; George, D.S. Fluorescence Probe for the Detection of Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) Using Antibody-Conjugated Silver Nanoclusters and MnO2 Nanosheets. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 18156–18165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Mao, Y. Luminescent Zn2GeO4:Mn2+ Nanoparticles with High Quantum Yield for Salivary Protein Detection. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 16260–16266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; He, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Pan, J.; Lao, Z.; Lin, M.; Wang, T.; Cui, X.; Ding, J.; Zhao, S. An ultrasensitive colorimetric assay based on a multi-amplification strategy employing Pt/IrO2@SA@HRP nanoflowers for the detection of progesterone in saliva samples. Anal. Methods 2021, 13, 1164–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulahoum, H.; Ghorbanizamani, F.; Timur, S. Laser-printed paper ELISA and hydroxyapatite immobilization for colorimetric congenital anomalies screening in saliva. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1306, 342617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, I.; Xue, R.; Srivastava, I. Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Nanotags: Design Strategies, Biomedical Applications, and Integration of Machine Learning. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 17, e70015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, N.; Hassanzadeh-Barforoushi, A.; Rey Gomez, L.M.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y. SERS biosensors for liquid biopsy towards cancer diagnosis by detection of various circulating biomarkers: Current progress and perspectives. Nano Converg. 2024, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Weng, H.; Chen, Z.; Zong, M.; Fang, S.; Wang, Z.; He, S.; Wu, Y.; Lin, J.; Feng, S. Antibody screening-assisted multichannel nanoplasmonic sensing chip based on SERS for viral screening and variants identification. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2025, 271, 117015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, V.; Sousa, P.; Catarino, S.O.; Correia-Neves, M.; Minas, G. Microfluidic immunosensor for rapid and highly-sensitive salivary cortisol quantification. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 90, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Choi, S.; Kwon, K.; Bae, N.-H.; Kwak, B.S.; Cho, W.C.; Lee, S.J.; Jung, H.-I. A photothermal biosensor for detection of C-reactive protein in human saliva. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 246, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Z.; Chi, J.; Yang, X.; Cheng, L.; Xie, D.; Tan, Z.; Chen, S.; Yun, Y.; Yibulayimu, Y.; Wu, W. Printed photonic crystal biochips for rapid and sensitive detection of biomarkers in various body fluids. Nat. Protoc. 2025, 20, 3783–3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Chi, J.; Lian, Z.; Yun, Y.; Yang, X.; He, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhao, W.; Gong, Z.; et al. One-droplet saliva detection on photonic crystal-based competitive immunoassay for precise diagnosis of migraine. SmartMat 2024, 5, e1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sun, X.; Ma, C.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, L.; Huang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Wan, H.; Wang, P. Multifunctional AuNPs@HRP@FeMOF immune scaffold with a fully automated saliva analyzer for oral cancer screening. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 222, 114910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Wang, S.; Zheng, J.; Li, B.; Cheng, N.; Gan, N. All-in-one microfluidic immunosensing device for rapid and end-to-end determination of salivary biomarkers of cardiovascular diseases. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2025, 271, 117077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D.; Mukherjee, A.; Ethiraj, K.R. Gold nanorod-based multiplex bioanalytical assay for the detection of CYFRA 21-1 and CA-125: Towards oral cancer diagnostics. Anal. Methods 2022, 14, 3614–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johannsen, B.; Karpíšek, M.; Baumgartner, D.; Klein, V.; Bostanci, N.; Paust, N.; Früh, S.M.; Zengerle, R.; Mitsakakis, K. One-step, wash-free, bead-based immunoassay employing bound-free phase detection. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1153, 338280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, Z.u.Q.; Samaraweera, S.; Wang, Z.; Krishnan, S. Colorimetric nano-biosensor for low-resource settings: Insulin as a model biomarker. Sens. Diagn. 2024, 3, 1659–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, M.; Arcadio, F.; Borriello, A.; Bencivenga, D.; Piccirillo, A.; Stampone, E.; Zeni, L.; Cennamo, N.; Della Ragione, F.; Guida, L. A novel plasmonic optical-fiber-based point-of-care test for periodontal MIP-1α detection. iScience 2023, 26, 108539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngamchuea, K.; Chaisiwamongkhol, K.; Batchelor-McAuley, C.; Compton, R.G. Chemical analysis in saliva and the search for salivary biomarkers–A tutorial review. Analyst 2018, 143, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.K.; Udeh-Momoh, C.; Lim, M.A.; Gleerup, H.S.; Leifert, W.; Ajalo, C.; Ashton, N.; Zetterberg, H.; Rissman, R.A.; Winston, C.N. Guidelines for the standardization of pre-analytical variables for salivary biomarker studies in Alzheimer’s disease research: An updated review and consensus of the Salivary Biomarkers for Dementia Research Working Group. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2025, 21, e14420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, O.; D’Agostino, V.G.; Lara Santos, L.; Vitorino, R.; Ferreira, R. Shaping the future of oral cancer diagnosis: Advances in salivary proteomics. Expert Rev. Proteom. 2024, 21, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noiphung, J.; Nguyen, M.P.; Punyadeera, C.; Wan, Y.; Laiwattanapaisal, W.; Henry, C.S. Development of Paper-Based Analytical Devices for Minimizing the Viscosity Effect in Human Saliva. Theranostics 2018, 8, 3797–3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, N.G.; Scoble, J.A.; Muir, B.W.; Pigram, P.J. Orientation and characterization of immobilized antibodies for improved immunoassays. Biointerphases 2017, 12, 02D301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Xie, S.; Steckl, A.J. Salivary endotoxin detection using combined mono/polyclonal antibody-based sandwich-type lateral flow immunoassay device. Sens. Diagn. 2023, 2, 1460–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, H.-J.; Kim, K.-S.; Kwoen, M.; Park, E.-S.; Lee, H.-J.; Park, K.-U. Saliva assay: A call for methodological standardization. J. Periodontal Implant Sci. 2024, 55, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfried-Blackmore, A.; Rubin, S.J.; Bai, L.; Aluko, S.; Yang, Y.; Park, W.; Habtezion, A. Effects of processing conditions on stability of immune analytes in human blood. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, D.B.; Rathoure, A.K.; Awasthi, A.; Gautam, S.; Kumar, S.; Kapoor, A. Microfluidic Paper-Based Lab-on-a-Chip Chemiluminescence Sensing for Healthcare and Environmental Applications: A Review. Luminescence 2025, 40, e70324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goumas, G.; Vlachothanasi, E.N.; Fradelos, E.C.; Mouliou, D.S. Biosensors, artificial intelligence biosensors, false results and novel future perspectives. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zant, W.; Ray, P. Democratization of Point-of-Care Viral Biosensors: Bridging the Gap from Academia to the Clinic. Biosensors 2025, 15, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneta, T.; Alahmad, W.; Varanusupakul, P. Microfluidic paper-based analytical devices with instrument-free detection and miniaturized portable detectors. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2019, 54, 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeniak, D.; Cruz, D.F.; Chilkoti, A.; Mikkelsen, M.H. Plasmonic fluorescence enhancement in diagnostics for clinical tests at point-of-care: A review of recent technologies. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2107986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hang, Y.; Wang, A.; Wu, N. Plasmonic silver and gold nanoparticles: Shape-and structure-modulated plasmonic functionality for point-of-caring sensing, bio-imaging and medical therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 2932–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-E.; Tieu, M.V.; Hwang, S.Y.; Lee, M.-H. Magnetic particles: Their applications from sample preparations to biosensing platforms. Micromachines 2020, 11, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crivianu-Gaita, V.; Thompson, M. Aptamers, antibody scFv, and antibody Fab’fragments: An overview and comparison of three of the most versatile biosensor biorecognition elements. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 85, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghayegh, F.; Norouziazad, A.; Haghani, E.; Feygin, A.A.; Rahimi, R.H.; Ghavamabadi, H.A.; Sadighbayan, D.; Madhoun, F.; Papagelis, M.; Felfeli, T. Revolutionary point-of-care wearable diagnostics for early disease detection and biomarker discovery through intelligent technologies. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2400595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sensor Design | Label | Signal Generation | Analyte | Detection Range, ng/mL | LOD, ng/mL | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lateral flow immunoassay | gold nanoparticles | colorimetric | cortisol | 0.01–10 | 3.8 × 10−3 | [114] |

| paper-based microanalytical devices | gold nanoparticles | colorimetric | cortisol | n/a | n/a | [115] |

| trap lateral flow immunoassay based ratiometric method (with deletion and detection zones) | gold nanoparticles | enzyme-catalyzed color signal | cortisol | 0.01–100 | 9.9 × 10−3 | [116] |

| dual-color competitive lateral flow immunoassay | gold nanoparticles and gold nanostars | color transition from red to blue | cortisol | n/a | low (0–10 ng/mL)—blue signal medium (15–25 ng/mL)—more purple, high (30–50 ng/mL), clearly pink/reddish | [117] |

| paper-based trap lateral flow immunoassay | gold nanoparticles | colorimetric | cortisol | 0.01–1000 | 9.1 × 10−3 | [118] |

| immune-chromatographic strip | gold nanoparticles | colorimetric | pepsin | 10–5000 | 10 | [119] |

| Immune- chromatographic test | gold nanoparticles | colorimetric | cortisol | 1–100 | 1 | [120] |

| lateral flow immunoassay | magnetic particles | colorimetric | CYFRA 21-1 | 0.002–2.1 | 0.9 × 10−3 | [121] |

| lateral flow immunoassay | gold nanoparticle | colorimetric | cortisol | 2.8–7.3 | 2.5 | [122] |

| lateral flow immunoassay | gold nanoparticles with silver enhancement | colorimetric | cortisol | 0.5–150 | 0.5 | [123] |

| lateral flow immunoassay | platinum nanoparticles | photoluminescence | cortisol | 0.14–200 | 0.139 | [124] |

| lateral flow immunoassay | HRP | chemiluminescence | cortisol | 0.3–60 | 0.3 | [125] |

| microchannel lateral flow assay on lab-on-a-chip | Dab-af488 | fluorescence | cortisol | 0.93–30.0 | 1.8 | [126] |

| Immune- chromatographic test strip | fluorescent microsphere 300 nm | fluorescence | pepsin | 2.5–100.0 | 1.9 | [127] |

| multiple lateral flow imunostrip | green core–shell upconversion nanoparticles | luminescence | MMP-8, IL-1β and TNF-α | n/a | MMP-8: 5.455 IL-1β: 0.054 TNF-α: 4.439 | [128] |

| lateral flow immunoplatform integrated with surface-enhanced Raman scattering | gold nanoparticle clusters with Raman reporter | SERS | cortisol | 0.01 × 10−3−100 | 0.014 × 10−3 | [129] |

| sandwich type of lateral flow immunoassay | enzymatic activity of streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase | electrochemical | CRP | n/a | 3 (in buffer) 55 (in filtered saliva) | [130] |

| electrochemical lateral flow assay with nanocatalytic redox cycling | gold nanoparticles and ammonia-borane | electrochemical | insulin | 0–29 | 0.07 | [131] |

| vertical flow paper-based sandwich immunoassay | eosin-conjugated reporter molecules | colorimetric | MMP-8 and MMP-9 | MMP-8: 0.02–0.85; MMP-9: 0.08–0.76 | - | [132] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Komova, N.S.; Serebrennikova, K.V.; Zherdev, A.V.; Dzantiev, B.B. Immunosensing Platforms for Detection of Metabolic Biomarkers in Oral Fluids. Biosensors 2025, 15, 794. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120794

Komova NS, Serebrennikova KV, Zherdev AV, Dzantiev BB. Immunosensing Platforms for Detection of Metabolic Biomarkers in Oral Fluids. Biosensors. 2025; 15(12):794. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120794

Chicago/Turabian StyleKomova, Nadezhda S., Kseniya V. Serebrennikova, Anatoly V. Zherdev, and Boris B. Dzantiev. 2025. "Immunosensing Platforms for Detection of Metabolic Biomarkers in Oral Fluids" Biosensors 15, no. 12: 794. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120794

APA StyleKomova, N. S., Serebrennikova, K. V., Zherdev, A. V., & Dzantiev, B. B. (2025). Immunosensing Platforms for Detection of Metabolic Biomarkers in Oral Fluids. Biosensors, 15(12), 794. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120794