Engineering the Morphology and Properties of MoS2 Films Through Gaseous Precursor-Induced Vacancy Defect Control

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

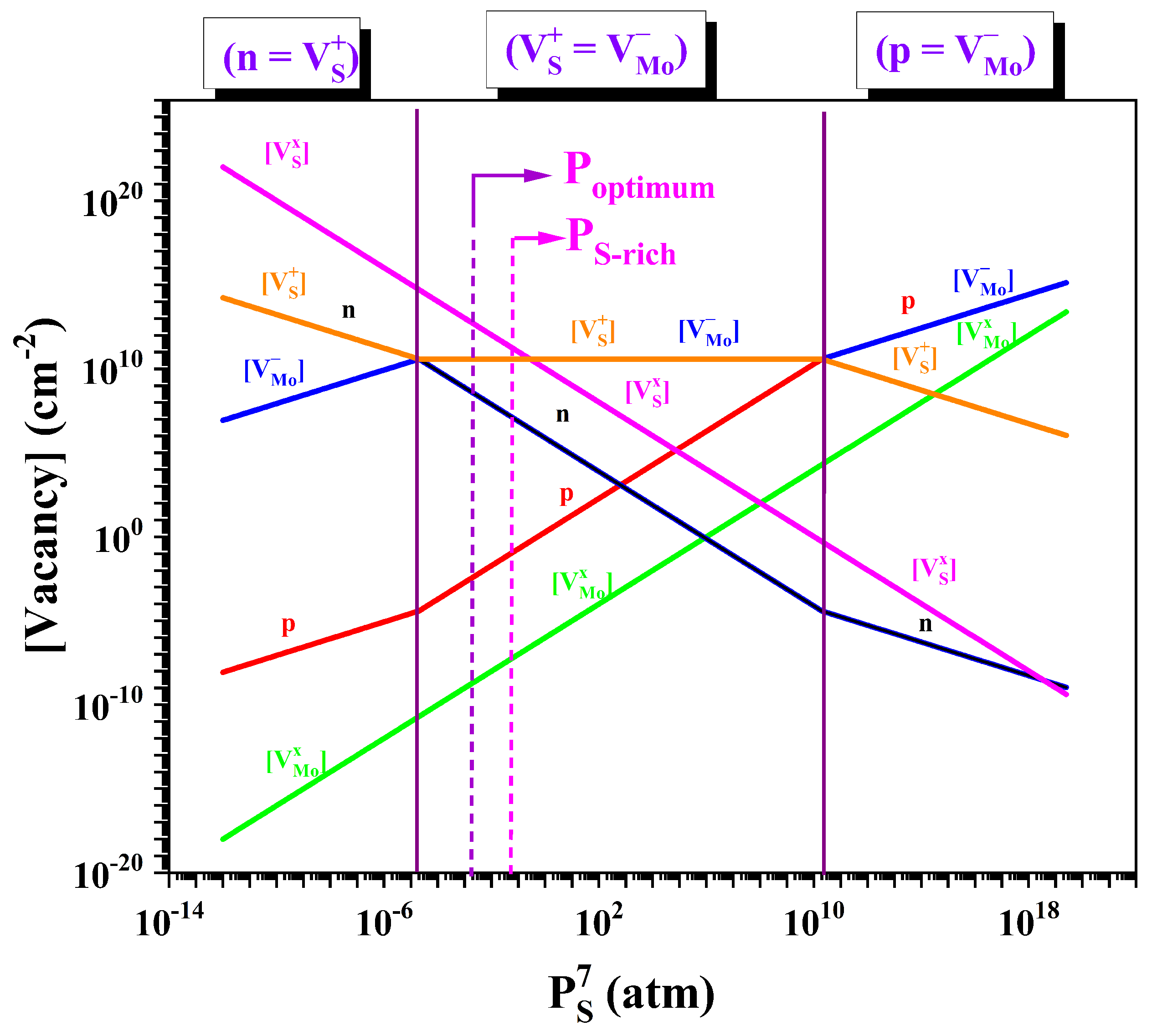

3.1. Analysis of Vacancy Defect Formation in MoS2

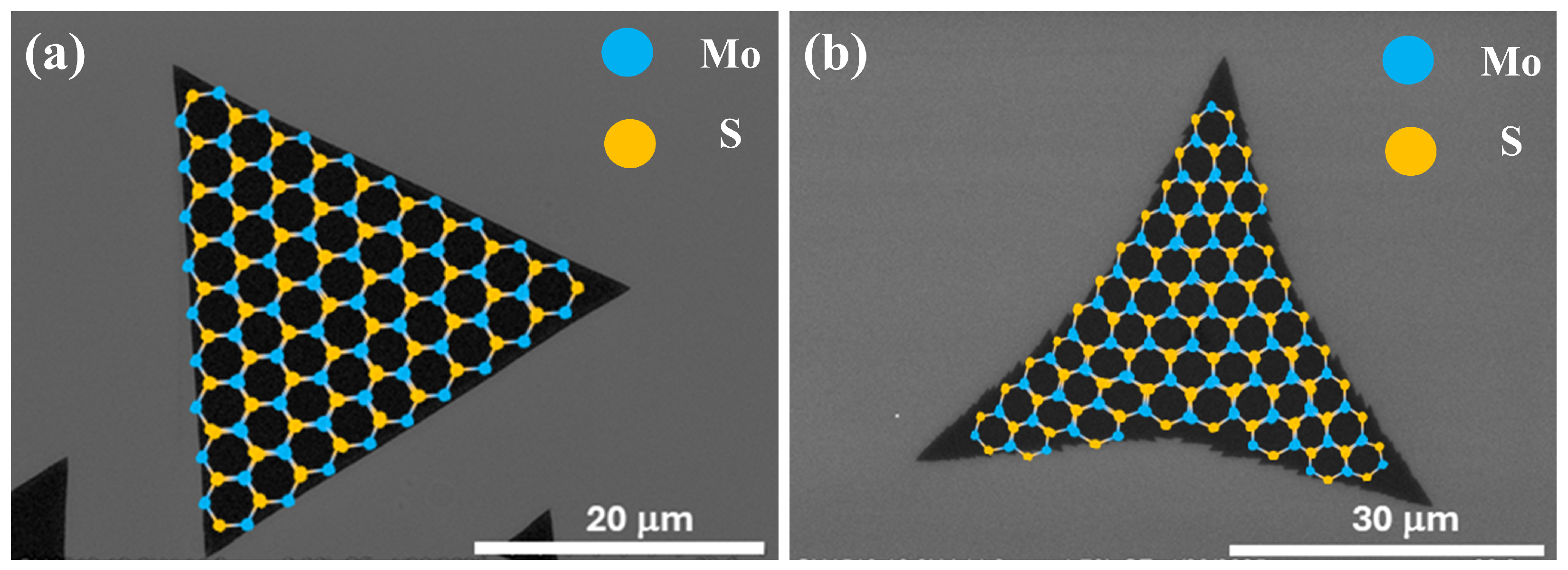

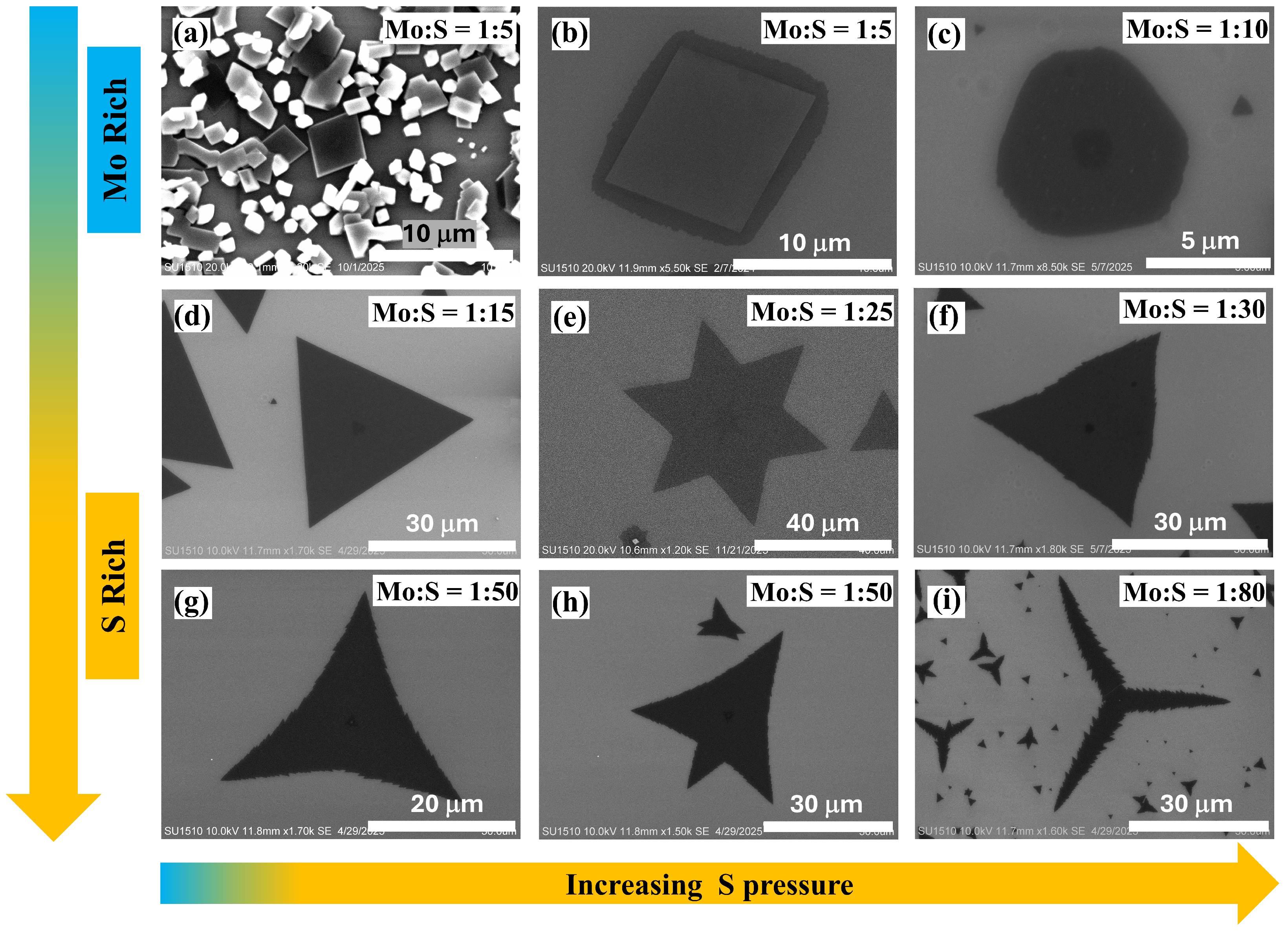

3.2. Evolution of Film Morphology, Structure and Composition with Varying S Vapor Pressure

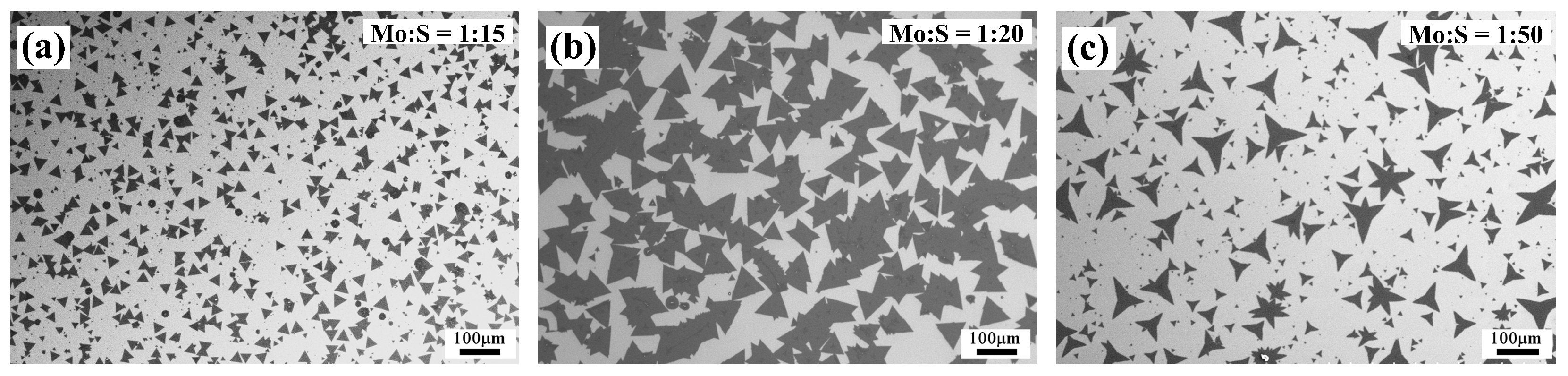

3.2.1. Variations in Film Morphology with Increasing S Pressure

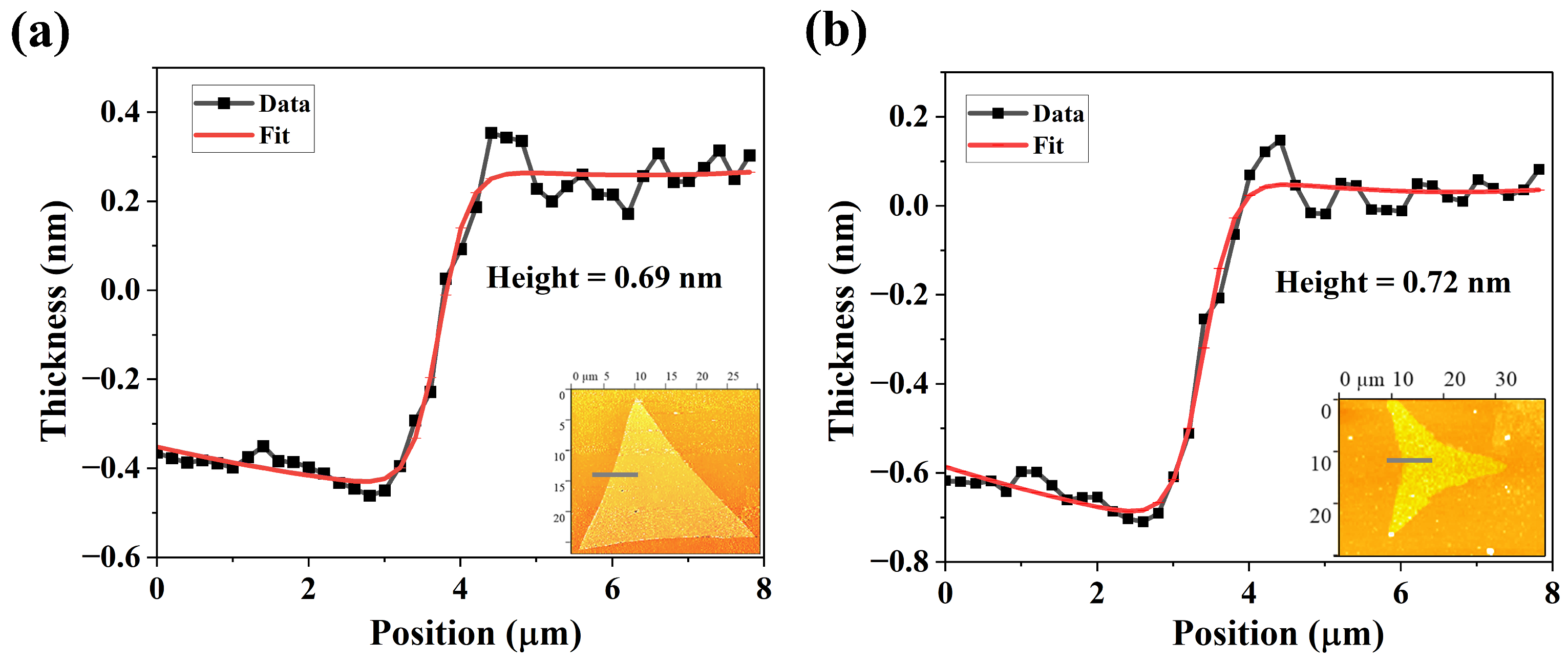

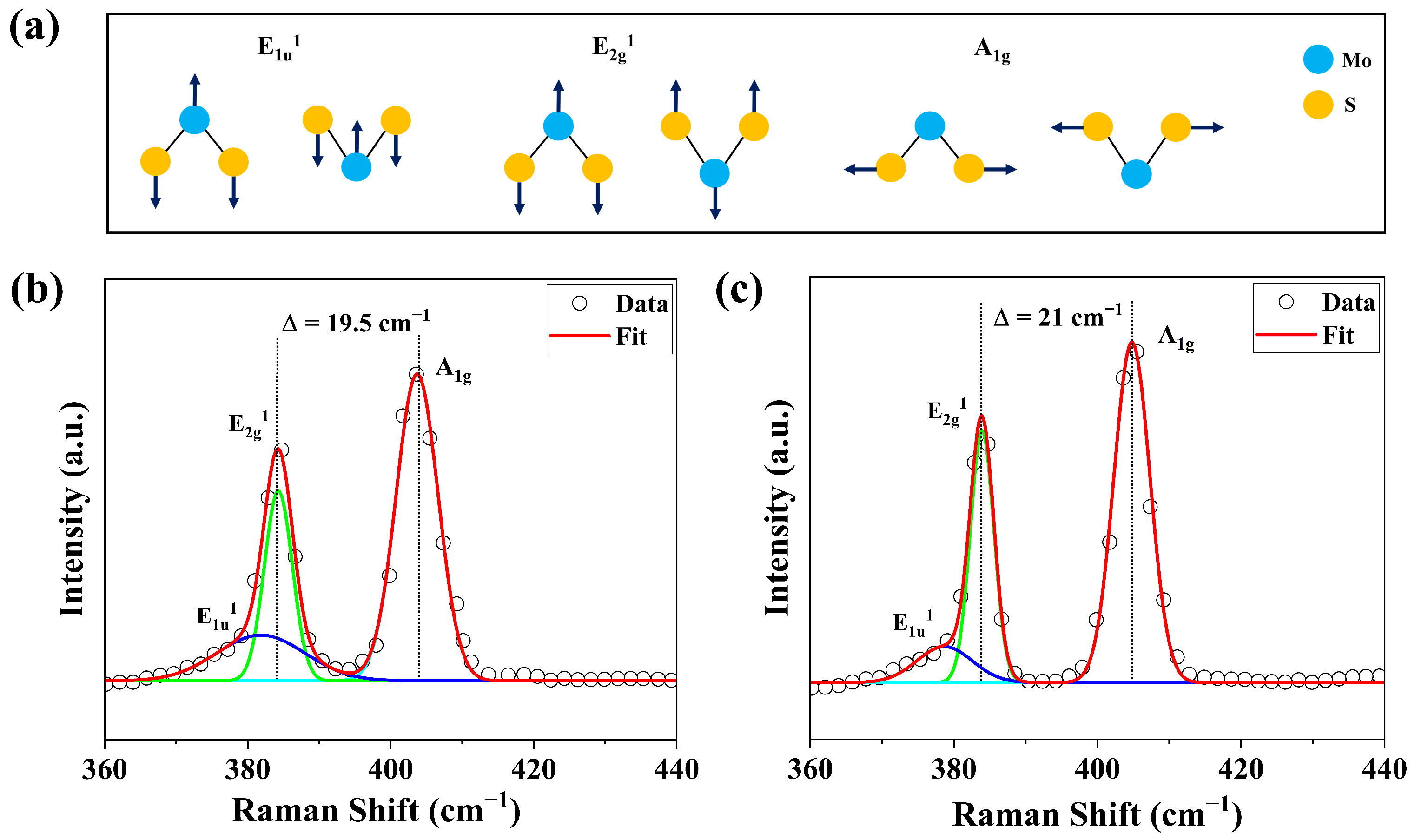

3.2.2. Structural and Compositional Characterization of Films Grown Under Varying S Pressure

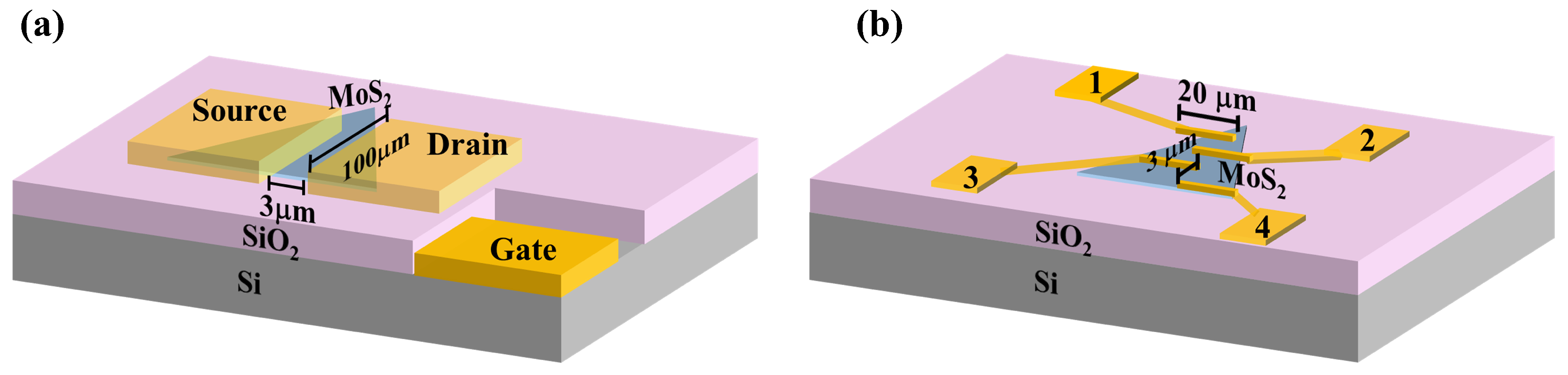

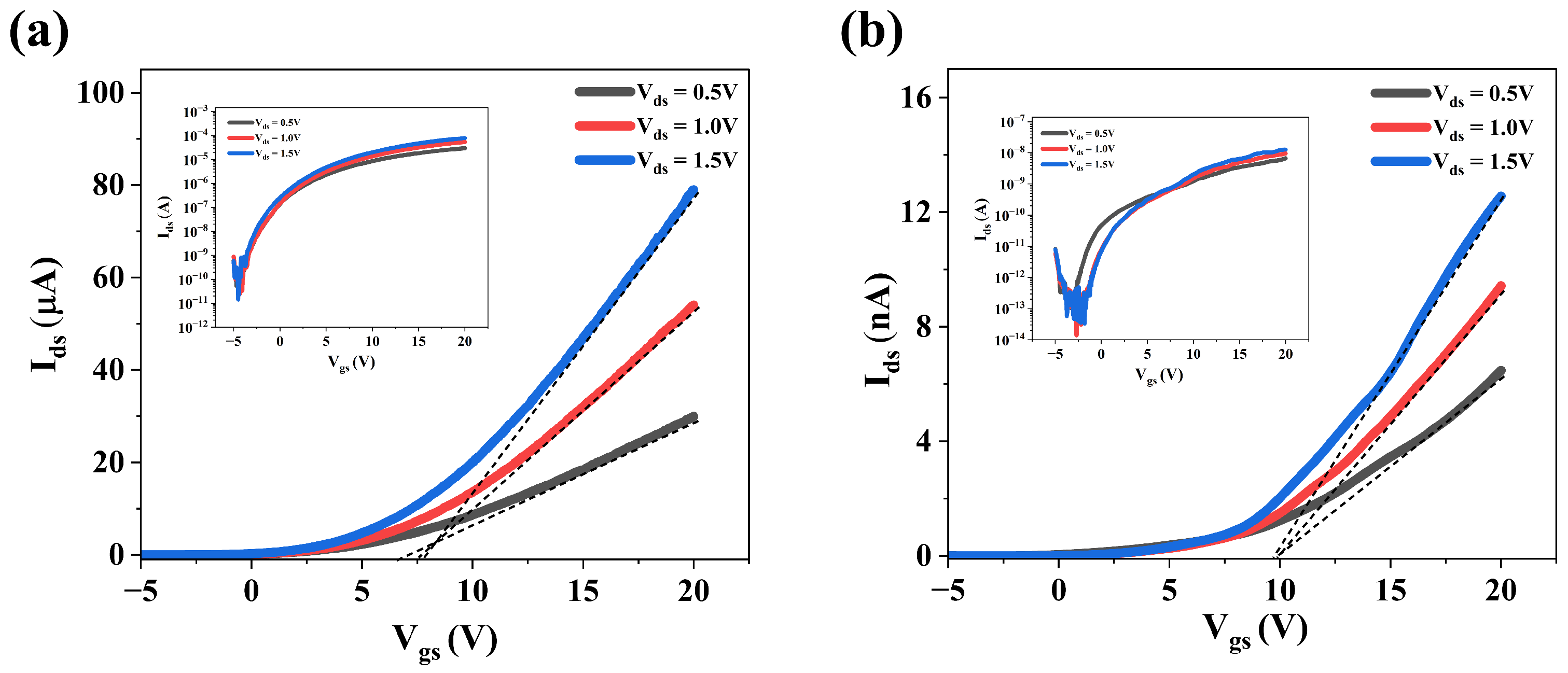

3.3. Electrical Properties of MoS2 Films Grown Under Varying S Pressure

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, Z.; Que, W. Molybdenum disulfide nanomaterials: Structures, properties, synthesis and recent progress on hydrogen evolution reaction. Appl. Mater. Today 2016, 3, 23–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalwa, H.S. A review of molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) based photodetectors: From ultra-broadband, self-powered to flexible devices. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 30529–30602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Liu, G.-B.; Feng, W.; Xu, X.; Yao, W. Coupled spin and valley physics in monolayers of MoS2 and other group-VI dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 196802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, K.F.; Lee, C.; Hone, J.; Shan, J.; Heinz, T.F. Atomically thin MoS2: A new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 136805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Q.; Jiang, D.-E. Stabilization and band-gap tuning of the 1T-MoS2 monolayer by covalent functionalization. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 3743–3748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radisavljevic, B.; Whitwick, M.B.; Kis, A. Integrated circuits and logic operations based on single-layer MoS2. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 9934–9938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yu, L.; Lee, Y.-H.; Shi, Y.; Hsu, A.; Chin, M.L.; Li, L.-J.; Dubey, M.; Kong, J.; Palacios, T. Integrated circuits based on bilayer MoS2 transistors. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 4674–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur, R.; Tsuchiya, T.; Toprasertpong, K.; Terabe, K.; Takagi, S.; Takenaka, M. High responsivity in MoS2 phototransistors based on charge trapping HfO2 dielectrics. Commun. Mater. 2020, 1, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Wang, X.; Su, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, D.; Guo, J.; Shao, L.; Bao, W.; Chen, H. Large-scale MoS2 pixel array for imaging sensor. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Mun, J.; Shin, J.-S.; Kang, S.-W. Highly sensitive two-dimensional MoS2 gas sensor decorated with Pt nanoparticles. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 181462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Vicente, N.; Pham, T.; Mulchandani, A. Biological sensing using vertical MoS2-graphene heterostructure-based field-effect transistor biosensors. Biosensors 2025, 15, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.-Y.; Tarasov, A.; Hesabi, Z.R.; Taghinejad, H.; Campbell, P.M.; Joiner, C.A.; Adibi, A.; Vogel, E.M. Flexible MoS2 field-effect transistors for gate-tunable piezoresistive strain sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 12850–12855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Fan, C.; Liu, J.; Hao, S.; Lu, X.; Zhou, J.; Qiu, M.; Li, J.; Hao, G. Te nanomesh-monolayer WSe2 vertical van der Waals heterostructure for high-performance photodetector. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2025, 126, 031904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Hao, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, K.; Fan, C.; Zhang, S.; Wei, Y.; Hao, G. Controllable growth of two-dimensional wrinkled WSe2 nanostructures via chemical vapor deposition based on thermal mismatch strategy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2024, 125, 072102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.; Wang, S.; Chu, L.; Toh, M.; Kumar, R.; Zhao, W.; Castro Neto, A.H.; Martin, J.; Adam, S.; Özyilmaz, B.; et al. Transport properties of monolayer MoS2 grown by chemical vapor deposition. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 1909–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Zou, X.; Najmaei, S.; Liu, Z.; Shi, Y.; Kong, J.; Lou, J.; Ajayan, P.M.; Yakobson, B.I.; Idrobo, J.-C. Intrinsic structural defects in monolayer molybdenum disulfide. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 2615–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchione, M.A.; Mendoza-Cruz, R.; Bazán-Diaz, L.; Velázquez-Salazar, J.J.; Santiago, U.; Arellano-Jiménez, M.J.; Perez, J.F.; José-Yacamán, M.; Samaniego-Benitez, J.E. Electron microscopy study of the carbon-induced 2H–3R–1T phase transition of MoS2. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 1190–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Y.; Shim, G.W.; Seo, S.-B.; Choi, S.-Y. Effective shape-controlled growth of monolayer MoS2 flakes by powder-based chemical vapor deposition. Nano Res. 2017, 10, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.-P.; Su, J.; Liu, Z.-T. Effect of vacancies in monolayer MoS2 on electronic properties of Mo–MoS2 contacts. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 20538–20544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Littler, C.; Syllaios, A.J.; Neogi, A.; Philipose, U. Analyzing growth kinematics and fractal dimensions of molybdenum disulfide films. Nanotechnology 2021, 32, 245602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-H.; Zhang, X.-Q.; Zhang, W.; Chang, M.-T.; Lin, C.-T.; Chang, K.-D.; Yu, Y.-C.; Wang, J.T.-W.; Chang, C.-S.; Li, L.-J.; et al. Synthesis of large-area MoS2 atomic layers with chemical vapor deposition. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1202.5458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, T.; Muijsers, J.C.; Van Wolput, J.H.M.C.; Verhagen, C.P.J.; Niemantsverdriet, J.W. Basic reaction steps in the sulfidation of crystalline MoO3 to MoS2, as studied by X-ray photoelectron and infrared emission spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 14144–14150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, G.; Abraham, J.; Littler, C.; Syllaios, A.J.; Philipose, U. Growth of highly-ordered metal nanoparticle arrays in the dimpled pores of an anodic aluminum oxide template. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pondick, J.V.; Woods, J.M.; Xing, J.; Zhou, Y.; Cha, J.J. Stepwise sulfurization from MoO3 to MoS2 via chemical vapor deposition. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2018, 1, 5655–5661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Huang, C.; Aivazian, G.; Ross, J.S.; Cobden, D.H.; Xu, X. Vapor–solid growth of high optical quality MoS2 monolayers with near-unity valley polarization. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 2768–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansh, A.; Patbhaje, U.; Kumar, J.; Meersha, A.; Shrivastava, M. Origin of electrically induced defects in monolayer MoS2 grown by chemical vapor deposition. Commun. Mater. 2023, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshchikov, M.A.; Morkoç, H. Luminescence properties of defects in GaN. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 97, 061301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipose, U.; Sapkota, G. Defect formation in InSb nanowires and its effect on stoichiometry and carrier transport. J. Nanopart. Res. 2013, 15, 2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smidstrup, S.; Stokbro, K.; Blom, A.; Markussen, T.; Wellendorff, J.; Schneider, J.; Gunst, T.; Verstichel, B.; Khomyakov, P.A.; Vej-Hansen, U.G.; et al. QuantumATK: An integrated platform of electronic and atomic-scale modelling tools. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2020, 32, 015901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smidstrup, S.; Stradi, D.; Wellendorff, J.; Khomyakov, P.A.; Vej-Hansen, U.G.; Lee, M.-E.; Ghosh, T.; Jónsson, E.; Jónsson, H.; Stokbro, K. First-principles Green’s-function method for surface calculations: A pseudopotential localized basis set approach. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 96, 195309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, M.W. NIST-JANAF thermochemical tables. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1998, 28, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Chadi, D.J. The problem of doping in II-VI semiconductors. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 1994, 24, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Rong, Y.; Fan, Y.; Pacios, M.; Bhaskaran, H.; He, K.; Warner, J.H. Shape evolution of monolayer MoS2 crystals grown by chemical vapor deposition. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 6371–6379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Li, H.; Xu, W.; Wang, S.; Sawada, H.; Allen, C.S.; Kirkland, A.I.; Grossman, J.C.; Warner, J.H. Atomically flat zigzag edges in monolayer MoS2 by thermal annealing. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 5502–5507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Tan, C.; Huang, X.; Ouyang, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, Z.; Dong, M. Emerging MoS2 wafer-scale technique for integrated circuits. Nano-Micro Lett. 2023, 15, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.K.; Singh, D.K. Continuous large area monolayered molybdenum disulfide growth using atmospheric pressure chemical vapor deposition. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 10930–10940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Li, S.; Zhou, S.; Lee, J.K.; Wang, S.; Sarwat, S.G.; Wang, X.; Bhaskaran, H.; Pasta, M.; Warner, J.H. Large dendritic monolayer MoS2 grown by atmospheric pressure chemical vapor deposition for electrocatalysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 4630–4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyagi, M.; Tiwari, A.A.; Dey, S.; Sahdev, D. Chemical vapor deposition growth of large-area molybdenum disulphide (MoS2) dendrites. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects 2024, 40, 101380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Amani, M.; Najmaei, S.; Xu, Q.; Zou, X.; Zhou, W.; Yu, T.; Qiu, C.; Birdwell, A.G.; Crowne, F.J.; et al. Strain and structure heterogeneity in MoS2 atomic layers grown by chemical vapour deposition. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Winslow, D.; Zhang, D.; Pandey, R.; Yap, Y.K. Recent advancement on the optical properties of two-dimensional molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) thin films. Photonics 2015, 2, 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, B.; Matte, H.S.S.R.; Sood, A.K.; Rao, C.N.R. Layer-dependent resonant Raman scattering of a few layer MoS2. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2013, 44, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isherwood, L.H.; Hennighausen, Z.; Son, S.-K.; Spencer, B.F.; Wady, P.T.; Shubeita, S.M.; Kar, S.; Casiraghi, C.; Baidak, A. The influence of crystal thickness and interlayer interactions on the properties of heavy ion irradiated MoS2. 2D Mater. 2020, 7, 035011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.; Neumann, C.; Kaiser, D.; Mupparapu, R.; Lehnert, T.; Hübner, U.; Tang, Z.; Winter, A.; Kaiser, U.; Staude, I.; et al. Controlled growth of transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers using Knudsen-type effusion cells for the precursors. J. Phys. Mater. 2019, 2, 016001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markeev, P.A.; Najafidehaghani, E.; Gan, Z.; Sotthewes, K.; George, A.; Turchanin, A.; de Jong, M.P. Energy-level alignment at interfaces between transition-metal dichalcogenide monolayers and metal electrodes studied with Kelvin probe force microscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 13551–13559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Ghosh, R.; Rai, A.; Sanne, A.; Kim, K.; Movva, H.C.P.; Dey, R.; Pramanik, T.; Chowdhury, S.; Tutuc, E.; et al. Intra-domain periodic defects in monolayer MoS2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 110, 201905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Li, F.; Xu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Qiu, F.; Li, Z.; Qi, J. High mobility monolayer MoS2 transistors and its charge transport behaviour under E-beam irradiation. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55, 14315–14325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Conde, A.; Sánchez, F.J.G.; Liou, J.J. On the extraction of threshold voltage, effective channel length and series resistance of MOSFETs. J. Telecommun. Inf. Technol. 2000, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hu, J.; Yue, C.; Della Fera, N.; Ling, Y.; Mao, Z.; Wei, J. High performance field-effect transistor based on multilayer tungsten disulfide. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 10396–10402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, S.; Addou, R.; Buie, C.; Wallace, R.M.; Hinkle, C.L. Defect-dominated doping and contact resistance in MoS2. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 2880–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuperman Benedik, H.; Rom, N.; Caspary Toroker, M. The effect of sulfur vacancy distribution on charge transport across MoS2 monolayers: A quantum mechanical study. ACS Mater. Au 2025, 5, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Cheng, P.; Chua, L.O.; Zhuge, F. All-optically controlled memristor for optoelectronic neuromorphic computing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2005582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferry, D.K. Electron transport in some transition metal di-chalcogenides: MoS2 and WS2. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2017, 32, 085003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baugher, B.W.H.; Churchill, H.O.H.; Yang, Y.; Jarillo-Herrero, P. Intrinsic electronic transport properties of high-quality monolayer and bilayer MoS2. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 4212–4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghatak, S.; Pal, A.N.; Ghosh, A. Nature of electronic states in atomically thin MoS2 field-effect transistors. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 7707–7712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.-H.; Kim, M.-S.; Shim, J.; Jeon, J.; Park, H.-Y.; Jung, W.-S.; Yu, H.-Y.; Pang, C.-H.; Lee, S.; Park, J.-H. High-performance transition metal dichalcogenide photodetectors enhanced by self-assembled monolayer doping. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 4219–4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.-W.; Shih, C.-C.; Lin, C.-L.; Yu, M.-Z.; Lai, J.-J.; Luo, J.-C.; Lin, G.-L.; Jian, W.-B.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; et al. High field-effect performance and intrinsic scattering in the two-dimensional MoS2 semiconductors. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 564, 150422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, B.; Bera, A.; Muthu, D.V.S.; Bhowmick, S.; Waghmare, U.V.; Sood, A.K. Symmetry-dependent phonon renormalization in monolayer MoS2 transistor. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 85, 161403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reaction Equations for Formation of Vacancies | Equilibrium Constant Equations (Mass–Action Relations) |

|---|---|

| 2 MoO3(g) + 7 S(g) ⇌ 2 MoS2(s) + 3 SO2(g) | Kf = · |

| 7 S(v) ⇌ + | Kv = []/ |

| + ⇌ 0 | = [][] |

| ⇌ + e− | Kd = [] n/[] |

| ⇌ + h+ | Ka = [] p/[] |

| 0 ⇌ n + p | Ki = n · p |

| Parameter | Optimum | S-Rich |

|---|---|---|

| () | ||

| (/Vs) | 20.4 | 13.1 |

| at V (V) | 7.5 | 9.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abraham, J.; Shepherd, N.D.; Littler, C.; Syllaios, A.J.; Philipose, U. Engineering the Morphology and Properties of MoS2 Films Through Gaseous Precursor-Induced Vacancy Defect Control. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1723. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15221723

Abraham J, Shepherd ND, Littler C, Syllaios AJ, Philipose U. Engineering the Morphology and Properties of MoS2 Films Through Gaseous Precursor-Induced Vacancy Defect Control. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(22):1723. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15221723

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbraham, James, Nigel D. Shepherd, Chris Littler, A. J. Syllaios, and Usha Philipose. 2025. "Engineering the Morphology and Properties of MoS2 Films Through Gaseous Precursor-Induced Vacancy Defect Control" Nanomaterials 15, no. 22: 1723. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15221723

APA StyleAbraham, J., Shepherd, N. D., Littler, C., Syllaios, A. J., & Philipose, U. (2025). Engineering the Morphology and Properties of MoS2 Films Through Gaseous Precursor-Induced Vacancy Defect Control. Nanomaterials, 15(22), 1723. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15221723