Digitally Designed Bone Grafts for Alveolar Defects: A Scoping Review of CBCT-Based CAD/CAM Workflows

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The use of autologous block grafts, considered the gold standard due to their osteogenic, osteoinductive, and osteoconductive properties. These grafts are typically harvested from intraoral sites (mandibular symphysis, ascending ramus, tuberosity) or extraoral sites (iliac crest), but they present several limitations: donor site morbidity, increased surgical time, postoperative pain, risk of paresthesia, intraoperative shaping difficulties, and unpredictable volumetric resorption [3,4,5,6].

- The use of particulate bone grafts (autologous, homologous, xenogeneic, or synthetic), combined with resorbable or non-resorbable membranes for guided bone regeneration (GBR). Although GBR is well-validated and widely applied, it requires strict stability of the blood clot, carries a high risk of membrane exposure, involves prolonged healing times, and may result in insufficient quantitative or qualitative bone regeneration [7,8,9].

- The use of preformed or 3D-printed grafting materials, such as synthetic scaffolds (e.g., hydroxyapatite or β-TCP), or standardized allogenic/xenogenic blocks. These approaches may also suffer from mismatch between graft and actual defect, difficulties in stabilization, poor anatomical adaptation, and variability in regenerative outcomes [10,11,12,13].

- To identify and describe digital workflows used in the planning and design of custom bone grafts for maxillary bone regeneration.

- To categorize the modeling and manufacturing techniques (e.g., CAD/CAM milling, 3D printing) employed to fabricate patient-specific bone grafts.

- To evaluate the types of bone graft materials (autologous, allogenic, xenogeneic, synthetic) utilized in clinical and preclinical applications.

- To summarize reported clinical, radiographic, histological, volumetric, and implant-related outcomes associated with the use of personalized bone grafts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocols

- Population: patients presenting with bone defects in the mandible or maxilla;

- Concept: application of digital workflows for the design and fabrication of customized bone grafts using 3D imaging, STL/CAD modeling, and CAM milling;

- Context: bone regeneration in oral surgery, maxillofacial surgery, and implantology.

2.2. Search Strategy

- PubMed: (“Bone Regeneration” [MeSH Terms] OR “Ridge Augmentation” OR “Bone Graft” OR “Alveolar Ridge Augmentation”) AND (“CAD/CAM” OR “Computer-Aided Design” OR “Custom Block” OR “Milling”) AND (“CBCT” OR “Cone Beam Computed Tomography” OR “STL File” OR “3D Printing”)

- Web of Science: TS = (“Bone Regeneration” OR “Ridge Augmentation” OR “Bone Graft” OR “Alveolar Ridge Augmentation”) AND TS = (“CAD/CAM” OR “Computer-Aided Design” OR “Custom Block” OR “Milling”) AND TS = (“CBCT” OR “Cone Beam Computed Tomography” OR “STL File” OR “3D Printing”)

- Ovid MEDLINE: (bone regeneration or ridge augmentation or bone graft* or alveolar ridge augmentation) .mp. AND (cad cam or computer aided design or computer aided manufacturing or custom* block* or custom* graft* or custom* scaffold* or milling or 3d print*) .mp. AND (cbct or cone beam or stl or stereolithograph* or 3d model*) .mp. AND english.lg. AND yr = “2015-Current”

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Studies published in English between 2015 and 2025;

- Studies conducted on human subjects or validated animal models, involving digital technologies (CBCT, STL, CAD/CAM) for the design and fabrication of personalized bone grafts;

- Documented use of customized bone blocks (autologous, allogenic, xenogeneic, or synthetic);

- Studies clearly describing the digital workflow and surgical grafting into the recipient site;

- Clinical studies, cohort studies, case reports, case series, in vitro or in vivo experimental research.

- Articles not written in English;

- Studies without access to the full text;

- Narrative reviews, letters to the editor, conference abstracts;

- Studies involving 3D printing of surgical guides, splints, meshes, or membranes not associated with the fabrication of a solid personalized graft;

- Studies focused solely on prosthetics, implants, or CAD/CAM components with no bone regenerative purpose;

- Studies on bone regeneration using non-customized particulate grafts.

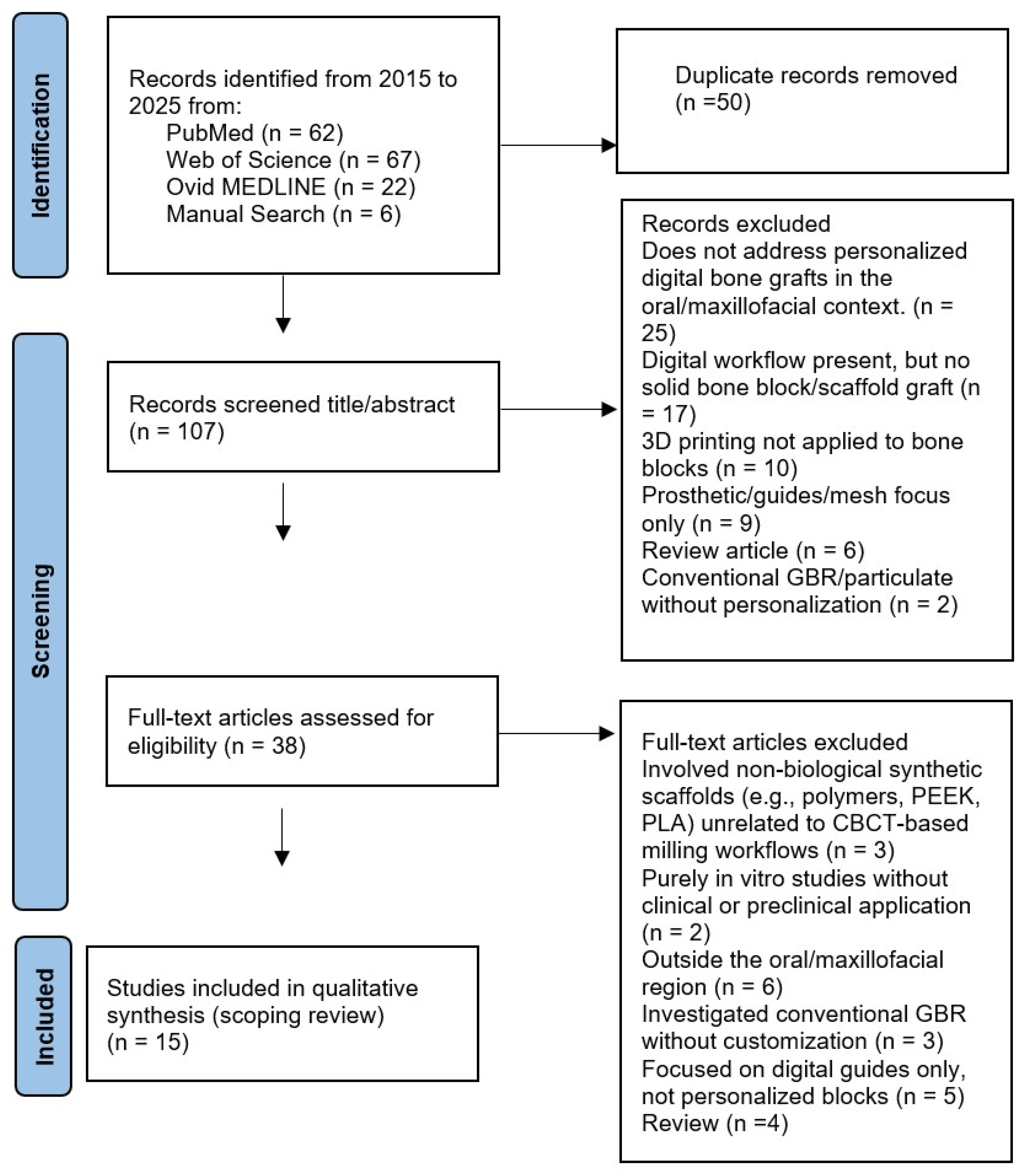

2.4. Study Selection

- (1)

- title and abstract screening for preliminary relevance assessment;

- (2)

- full-text reading to evaluate eligibility based on the predefined criteria.

2.5. Data Extraction

- Author and year of publication;

- Type of study (clinical, preclinical, in vitro, in vivo);

- Population (human or animal model);

- Type of bone defect treated (mandible or maxilla; vertical/horizontal/3D);

- Type of graft used (autologous, allogenic, xenogeneic, synthetic);

- Technologies used for the design and production of the graft (CBCT, STL segmentation, CAD modeling, CAM milling or 3D printing);

- Method of graft placement and type of fixation;

- Evaluated outcomes (e.g., bone integration, volumetric stability, complications, implant success);

- Main results, conclusions, and limitations as reported by the authors.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Overview of Included Literature

- 25—does not address personalized digital bone grafts in the oral/maxillofacial context.

- 17—digital workflow present, but no solid bone block/scaffold graft (e.g., planning, navigation, or generic CAD only).

- 10—3D printing general (biomaterials/platforms) not applied to personalized bone blocks or not oral.

- 9—prosthetic/guides/mesh focus only (no personalized bone block).

- 6—review article (excluded by protocol).

- 2—conventional GBR/particulate without personalization.

- 3 involved non-biological synthetic scaffolds (e.g., polymers, PEEK, PLA) unrelated to CBCT-based milling workflows.

- 2 were purely in vitro studies without clinical or preclinical application.

- 6 addressed bone regeneration but outside the oral/maxillofacial region (orthopedic or cranial vault).

- 3 investigated conventional GBR without customization.

- 5 focused on digital guides only, not personalized blocks.

- 4 were reviews

- Synthetic materials (e.g., hydroxyapatite, TCP, PLA): 13 articles.

- CAD/CAM-milled allogenic bone blocks: 7 articles.

- Customized xenografts: 1 articles, specifically a CAD/CAM-milled xenogeneic cancellous block designed from CBCT data.

- Unspecified or mixed materials: 2 articles.

3.2. Characteristics and Technological Approaches of Included Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Future Research Directions

4.2. Limitation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| β-TCP | β-Tricalcium Phosphate |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| CAM | Computer-Aided Manufacturing |

| CBCT | Cone-Beam computed tomography |

| GBR | Guided Bone Regeneration |

| HA | Hydroxyapatite |

| PLA | Polylactic Acid |

| PEEK | Polyether Ether Ketone |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews |

| PCC | Population-Concept-Context |

| STL St | Standard Tessellation Language |

References

- Schropp, L.; Wenzel, A.; Kostopoulos, L.; Karring, T. Bone healing and soft tissue contour changes following single-tooth extraction: A clinical and radiographic 12 month prospective study. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2003, 23, 313–323. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, M.G.; Lindhe, J. Dimensional ridge alterations following tooth extraction. An experimental study in the dog. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2005, 32, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkenke, E.; Radespiel Tröger, M.; Wiltfang, J.; Schultze Mosgau, S.; Winkler, G.; Neukam, F.W. Morbidity of harvesting of retromolar bone grafts: A prospective study. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2002, 13, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarano, A.; Carinci, F.; Assenza, B.; Piattelli, A. Vertical ridge augmentation using an inlay technique with a xenograft without miniscrews and miniplates: A case series. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2011, 22, 1125–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Grusovin, M.G.; Felice, P.; Karatzopoulos, G.; Worthington, H.V.; Coulthard, P. Interventions for replacing missing teeth: Horizontal and vertical bone augmentation techniques for dental implant treatment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, CD003607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misch, C.M. Autogenous bone: Is it still the gold standard? Implant. Dent. 2010, 19, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, I.A.; Jovanovic, S.A.; Lozada, J.L. Vertical ridge augmentation using guided bone regeneration in three clinical scenarios prior to implant placement: A retrospective study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2009, 24, 502–510. [Google Scholar]

- Zitzmann, N.U.; Naef, R.; Schärer, P. Resorbable versus nonresorbable membranes in combination with Bio Oss for guided bone regeneration. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 1997, 12, 844–852. [Google Scholar]

- Nissan, J.; Mardinger, O.; Chaushu, G.; Calderon, S.; Schwartz Arad, D. Long term outcome of autogenous block grafts for alveolar ridge augmentation. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 69, 2654–2658. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, E.J.; Davydov, A.V.; Frukhtbeyen, S.; Seppala, J.E.; Takagi, S.; Chow, L.; Alimperti, S. Biofabrication of 3D printed hydroxyapatite composite scaffolds for bone regeneration. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 16, 045020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacotti, M. CAD CAM customized bone grafts in pre implant surgery: A case report. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2006, 21, 387–390. [Google Scholar]

- Seemann, R.; Rybaczek, T.; Moser, D.; Gahleitner, A.; Schicho, K.; Ewers, R. Computer assisted bone augmentation in the edentulous maxilla using individualized CAD/CAM scaffolds. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2010, 21, 801–806. [Google Scholar]

- Mangano, F.; Zecca, P.; Pozzi Taubert, S.; Macchi, A.; Luongo, G.; Mangano, C. Maxillary sinus augmentation using CAD/CAM technology. Int. J. Med. Robot. 2012, 8, 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Yen, T.; Stathopoulou, P.G. CAD/CAM and 3D printing applications for alveolar ridge augmentation: A systematic review. Curr. Oral Health Rep. 2018, 5, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlee, M.; Rothamel, D. Ridge augmentation using customized allogenic bone blocks: A case series. Implant. Dent. 2013, 22, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume, O.; Back, M.; Dinya, E.; Palkovics, D.; Windisch, P. Efficacy and volume stability of a customized allogeneic bone block for the reconstruction of advanced alveolar ridge deficiencies at the anterior maxillary region: A retrospective radiographic evaluation. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 3927–3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangano, C.; Luongo, G.; Luongo, F.; Lerner, H.; Margiani, B.; Admakin, O.; Mangano, F. Custom-made computer-aided-design/computer-assisted-manufacturing (CAD/CAM) synthetic bone grafts for alveolar ridge augmentation: A retrospective clinical study with 3 years of follow-up. J. Dent. 2022, 127, 104323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figliuzzi, M.; Mangano, F.G.; Fortunato, L.; De Fazio, R.; Macchi, A.; Iezzi, G.; Piattelli, A.; Mangano, C. Vertical ridge augmentation of the atrophic posterior mandible with custom made CAD/CAM porous hydroxyapatite scaffolds. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2013, 24, 856–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mounir, M.; Shalash, M.; Mounir, S.; Nassar, Y.; El Khatib, O. Assessment of three-dimensional bone augmentation of severely atrophied maxillary alveolar ridges using prebent titanium mesh vs customized poly-ether-ether-ketone (PEEK) mesh: A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2019, 21, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Morsy, O.A.; Barakat, A.; Mekhemer, S.; Mounir, M. Assessment of 3-dimensional bone augmentation of severely atrophied maxillary alveolar ridges using patient-specific poly ether-ether ketone (PEEK) sheets. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2020, 22, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boogaard, M.J.; Romanos, G.E. Allograft customized bone blocks for ridge reconstruction: A case report and radiological analysis. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzal, S.Q.; Al-Dubai, M.; Mounir, R.; Ali, S.; Mounir, M. Maxillary vertical alveolar ridge augmentation using computer-guided sandwich osteotomy technique with simultaneous implant placement versus conventional technique: A pilot study. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2021, 23, 842–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaffeneder Mantai, S.; Rupprecht, S.; Tietze, A.; Locher, M.; Wiltfang, J. Maxillary full arch horizontal augmentation with CAD/CAM allogenic blocks: A case report. Maxillofac. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2022, 44, 21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ambrosio, F.; Azimi, K.; López-Torres, A.; Notice, T.; Khoshneviszadeh, A.; Neely, A.; Kinaia, B. Custom allogeneic block graft for ridge augmentation: Case series. Clin. Adv. Periodontics 2023, 13, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, A.; Leira, Y.; Batalla, P.; Caneiro, L.; Wichmann, M.; Blanco, J. Three-dimensional imaging analysis of CAD/CAM custom-milled versus prefabricated allogeneic block remodelling at 6 months and long-term follow-up of dental implants: A retrospective cohort study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2024, 51, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hnítecka, S.; Payer, M.; Slouka, D.; Koller, J.; Rasperini, G.; Schlee, M. Ridge augmentation using customized CAD/CAM xenogeneic bone blocks: A multicenter case series with histological analysis. Materials 2024, 17, 5305. [Google Scholar]

- Portelli, M.; Militi, A.; Lo Giudice, A.; Lo Giudice, R.; Rustico, L.; Fastuca, R.; Perillo, L. 3D Assessment of Endodontic Lesions with a Low-Dose CBCT Protocol. Dent. J. 2020, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangano, F.G.; Zecca, P.; van Noort, R.; Apresyan, S.; Iezzi, G.; Piattelli, A.; Macchi, A.; Mangano, C. Custom-Made Computer-Aided Design/Computer-Aided Manufacturing Biphasic Calcium-Phosphate Scaffold for Augmentation of an Atrophic Mandibular Anterior Ridge: Case Report. Case Rep. Dent. 2015, 2015, 941265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, P.S.; Earwaker, W.J.; Barker, T.M.; Redmond, M.J.; Thompson, R.G.; Effeney, D.J.; Tomlinson, F.H. Custom Cranioplasty Using Stereolithography and Acrylic. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 2000, 53, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botticelli, D.; Berglundh, T.; Lindhe, J. The Jumping Distance Revisited: An Experimental Study in the Dog. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2003, 14, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suomalainen, A.; Vehmas, T.; Kortesniemi, M.; Robinson, S.; Peltola, J. Accuracy of Linear Measurements Using Cone Beam Computed Tomography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2008, 37, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauwels, R.; Jacobs, R.; Singer, S.R.; Mupparapu, M. CBCT-Based Bone Quality Assessment: Are Hounsfield Units Applicable? Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2015, 44, 20140238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spin-Neto, R.; Gotfredsen, E.; Wenzel, A. Impact of Voxel Size Variation on CBCT-Based Diagnostic Outcome in Dentistry: A Systematic Review. J. Digit. Imaging 2013, 26, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santagata, M.; De Luca, R.; Lo Giudice, G.; Troiano, A.; Lo Giudice, G.; Corvo, G.; Fortunato, L. Arthrocentesis and Sodium Hyaluronate Infiltration in Temporomandibular Disorders Treatment. Clinical and MRI Evaluation. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2020, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puleio, F.; Lizio, A.S.; Coppini, V.; Lo Giudice, R.; Lo Giudice, G. CBCT-Based Assessment of Vapor Lock Effects on Endodontic Disinfection. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, R.; Lupi, E.; Iacomino, E.; Galeotti, A.; Capogreco, M.; Santos, J.M.M.; D’Amario, M. Low-Level Laser Therapy for the Treatment of Oral Mucositis Induced by Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Medicina 2023, 59, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trybek, G.; Jedliński, M.; Jaroń, A.; Preuss, O.; Mazur, M.; Grzywacz, A. Impact of Lactoferrin on Bone Regenerative Processes and Its Possible Implementation in Oral Surgery—A Systematic Review of Novel Studies with Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author and Year | Study Type | Model/Population | Bone Defect | Graft Material | Technology | Fixation | Main Outcomes | Conclusions/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jacotti 2006 [11] | Case report | 1 patient | Posterior mandible ridge deficiency | Customized allogeneic block | CBCT → CAD/CAM milling | Titanium screws + membrane | Feasible adaptation, implant placement achieved | Single case, short follow-up |

| Seemann 2010 [12] | Pilot clinical series | Patients (n not specified) | Edentulous maxilla | Individualized CAD/CAM synthetic scaffolds | CBCT → CAD/CAM | Screws | Feasibility; implant placement possible | Pilot; limited data |

| Mangano 2012 [13] | Case series | 5 patients, 10 sinuses | Posterior maxilla, sinus lift | Custom HA blocks | CBCT-based CAD/CAM | Not specified | All implants functional at 2 years | Small sample, synthetic HA only |

| Schlee 2013 [15] | Case series | ≤3 patients | Horizontal/vertical ridge defects | Allogeneic cancellous block | CBCT → CAD/CAM | Titanium screws + membrane | Histology showed vital bone, feasibility | Very small series |

| Mangano 2012 [18] | Clinical report | Patients (n not specified) | Maxillary sinus augmentation | Custom synthetic grafts | CBCT → CAD/CAM | Not specified | Successful augmentation, implants placed | Details incomplete |

| Figliuzzi 2013 [19] | Case report | 1 patient | Posterior mandible, vertical defect | Porous HA scaffold | CBCT → CAD/CAM | Titanium screws | Implants placed at 6 months, functional | Limited evidence |

| Mounir 2019 [20] | Randomized clinical trial | 16 patients, 32 implants | Severe ridge atrophy | Autograft/xenograft particulate with PEEK vs. Ti mesh | CAD/CAM PEEK vs. prebent Ti mesh | Screws | Comparable bone gain; PEEK easier handling | Pilot RCT, short-term |

| El Morsy 2020 [21] | Clinical study | 14 patients, 34 implants | Anterior maxilla, severe atrophy | Autograft + xenograft particulate, PEEK containment | CAD/CAM PEEK sheets | Monocortical screws | Significant 3D bone gain; 1 dehiscence | No control, device study |

| Boogaard 2021 [22] | Case report | 1 patient | Atrophic mandible, vertical defect | Customized allogeneic block (ACBB) | CBCT → CAD/CAM | Titanium screws | No resorption at 5 months, implant osseointegrated | Single case |

| Nazzal 2021 [23] | Pilot RCT | 12 patients (6 guided vs. 6 conventional) | Vertical maxillary deficiency | Autogenous interpositional graft | 3D-printed patient-specific guides | Plates/screws | Improved accuracy of vertical gain | Not a block, but relevant workflow |

| Pfaffeneder-Mantai 2022 [24] | Multicenter prospective | 1 patient (case report in abstract) | Atrophic maxilla | Customized allogeneic blocks | CBCT → CAD/CAM | Screws | Stable augmentation, implants placed at 14 months | Case-based; limited data |

| Ambrosio 2023 [25] | Case series | 2 patients | Horizontal ridge defects | Customized allogeneic blocks | CBCT → CAD/CAM | Likely screws + membrane | Reduced surgical time, stable augmentation, implants placed | Promising but very limited |

| Blume 2023 [16] | Prospective study | Patients with anterior maxillary atrophy | Anterior maxilla defects | Customized allogeneic cancellous block | CBCT → CAD/CAM; volumetric 3D analysis | Screws + membrane | Hard tissue gain 0.75 cm3 at 2 mo, 0.52 cm3 at 6 mo; stability ratio 67.8% | Reliable but small sample |

| Seidel 2024 [26] | Retrospective cohort | 19 patients, 20 grafts | Horizontal/vertical defects | Allogeneic blocks (custom vs. prefabricated) | CBCT → CAD/CAM | Screws + membranes | Bone stability 87.6% vs. 83% at 6 mo; implant FU 44 mo | Retrospective, heterogeneous |

| Hnítecka 2024 [27] | Multicenter case series | Patients (n not specified) | Alveolar ridge defects | Customized xenogeneic blocks | CBCT → CAD/CAM | Screws + membrane | Feasible; some histology available | Sample size/outcomes limited |

| a | |||||

| Author Year | Jacotti 2006 [11] | Seemann 2010 [12] | Mangano 2012 [13] | Schlee 2013 [15] | Blume 2023 [16] |

| Study type | Case report Study type | Pilot series | Case series | Case series | Prospective study |

| Population Model | 1 patient Population/Model | Patients (n NR) | 5 pts/10 sinuses | ≤3 patients | Patients with anterior maxillary atrophy |

| Site/Defect | Posterior mandible ridge deficiency Site/Defect | Edentulous maxilla | Posterior maxilla, sinus lift | Horizontal/vertical ridge defects | Anterior maxilla defects |

| Graft material | Customized allogeneic block Graft material | Synthetic individualized scaffold | Custom HA blocks | Customized allogeneic cancellous block | Customized allogeneic cancellous block |

| Workflow | CBCT → CAD/CAM milling Workflow | CBCT → CAD/CAM | CBCT → CAD/CAM | CBCT → CAD/CAM | CBCT → CAD/CAM + volumetric analysis |

| Fit tolerance (mm) | NR Fit tolerance (mm) | NR | NR | ≤0.5 mm (qualitative) | ≤0.5 mm |

| Volumetric stability/Bone gain | NR Volumetric stability/Bone gain | NR | All implants functional at 24 mo | NR | 0.75 cm3 at 2 mo → 0.52 cm3 at 6 mo (67.8%) |

| Follow-up (month) | NR Follow-up | 12 | 24 | 12 | 6 |

| Implant survival | Implant placed (reported) Implant survival | NR | 100% (10/10) | 100% (reported) | NR |

| Histology | NR Histology | NR | NR | Yes | NR |

| Notes | Single case; short FU Notes | Feasibility pilot | Synthetic HA only | Very small series | Dimensional analysis |

| b | |||||

| Author Year | Mangano 2012 [18] | Figliuzzi 2013 [19] | Mounir 2019 [20] | El Morsy 2020 [21] | Boogaard 2021 [22] |

| Study type | Clinical report | Case report | RCT pilot | Clinical study | Case report |

| Population Model | Patients (n NR) | 1 patient | 16 pts/32 implants | 14 pts/34 implants | 1 patient |

| Site/Defect | Maxillary sinus augmentation | Posterior mandible, vertical defect | Severe ridge atrophy | Anterior maxilla, severe atrophy | Atrophic mandible, vertical defect |

| Graft material | Custom synthetic grafts | Porous HA scaffold | Auto/xeno particulate with PEEK vs. Ti mesh | Particulate + PEEK containment | Customized allogeneic block |

| Workflow | CBCT → CAD/CAM | CBCT → CAD/CAM | CAD/CAM PEEK vs. Ti mesh | CAD/CAM PEEK sheets | CBCT → CAD/CAM |

| Fit tolerance (mm) | NR | ≤0.3 mm (qualitative) | NR | NR | NR |

| Volumetric stability/Bone gain | Successful augmentation; implants placed | Implants placed at 6 mo | Comparable bone gain | Vertical: 3.47 ± 1.46 mm; Horizontal: 3.42 ± 1.10 mm | No resorption at 5 mo |

| Follow-up (month) | NR | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| Implant survival | NR | 100% (1/1) | NR | Implants placed | Implant osseointegrated |

| Histology | NR | Yes | NR | NR | Yes |

| Notes | Details incomplete | Functional outcome | Handling easier with PEEK | 1 wound dehiscence | Single case |

| c | |||||

| Author Year | Nazzal 2021 [23] | Pfaffeneder-Mantai 2022 [24] | Ambrosio 2023 [25] | Seidel 2024 [26] | Hnítecka 2024 [27] |

| Study type | Pilot RCT | Prospective multicenter | Case series | Retrospective cohort | Multicenter case series |

| Population Model | 12 pts (6 guided vs. 6 conv.) | Patients (case-based) | 2 patients | 19 pts/20 grafts | Patients (n NR) |

| Site/Defect | Vertical maxillary deficiency | Horizontal ridge defects | Horizontal ridge defects | Horizontal/vertical defects | Alveolar ridge defects |

| Graft material | Autogenous interpositional graft | Customized allogeneic blocks | Customized allogeneic blocks | Allogeneic blocks (custom vs. prefab) | Customized xenogeneic blocks |

| Workflow | 3D-printed surgical guides | CBCT → CAD/CAM | CBCT → CAD/CAM | CBCT → CAD/CAM | CBCT → CAD/CAM |

| Fit tolerance (mm) | NR | NR | NR | ≤0.5 mm | ≤0.5 mm |

| Volumetric stability/Bone gain | Guided > conventional accuracy | Stable augmentation; implants placed | Stable augmentation; implants placed | Stability: 87.6% vs. 83% at 6 mo; MBL 0.41 mm | Volumetric stability; positive histology |

| Follow-up (month) | 6 | 14 | 6 | Up to 44 | 12 |

| Implant survival | NR | NR | NR | 100% | NR |

| Histology | NR | NR | NR | NR | Yes |

| Notes | Workflow study | Multicenter | Small case series | Heterogeneous | Early evidence |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Puleio, F.; Lo Giudice, G.; Marenzi, G.; Bucci, R.; Nucera, R.; Lo Giudice, R. Digitally Designed Bone Grafts for Alveolar Defects: A Scoping Review of CBCT-Based CAD/CAM Workflows. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 310. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16090310

Puleio F, Lo Giudice G, Marenzi G, Bucci R, Nucera R, Lo Giudice R. Digitally Designed Bone Grafts for Alveolar Defects: A Scoping Review of CBCT-Based CAD/CAM Workflows. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2025; 16(9):310. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16090310

Chicago/Turabian StylePuleio, Francesco, Giuseppe Lo Giudice, Gaetano Marenzi, Rosaria Bucci, Riccardo Nucera, and Roberto Lo Giudice. 2025. "Digitally Designed Bone Grafts for Alveolar Defects: A Scoping Review of CBCT-Based CAD/CAM Workflows" Journal of Functional Biomaterials 16, no. 9: 310. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16090310

APA StylePuleio, F., Lo Giudice, G., Marenzi, G., Bucci, R., Nucera, R., & Lo Giudice, R. (2025). Digitally Designed Bone Grafts for Alveolar Defects: A Scoping Review of CBCT-Based CAD/CAM Workflows. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 16(9), 310. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16090310