Antibacterial Characteristics of Nanoclay-Infused Cavit Temporary Filling Material: In Vitro Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Bacteria

2.2. Experimental Groups

- Cavit1 (C1): negative control = 100% by weight CAVISOL temporary filling material + 3 drops eugenol.

- Cavit2 (C2): 80% by weight CAVISOL temporary filling material + 20% by weight nanoclay + 3 drops eugenol.

- Cavit3 (C3): 60% by weight CAVISOL temporary filling material + 40% by weight nanoclay + 3 drops eugenol.

- Cavit4 (C4): 40% by weight CAVISOL temporary filling material + 60% by weight nanoclay + 3 drops eugenol.

- Cavit5 (C5): 20% by weight CAVISOL temporary filling material + 80% by weight nanoclay + 3 drops eugenol.

- Cavit6 (C6): positive control = 100% by weight nanoclay + 3 drops eugenol.

2.3. Tests

- Zone of Inhibition Testing: the zone of inhibition was evaluated using two methods, disk diffusion and the well diffusion assay.

- The microtiter dish assay.

2.4. Implementation Method

2.4.1. Preparation of Experimental Groups

2.4.2. Preparation of Culture Media

2.4.3. Preparation of Bacterial Suspension

2.4.4. Disc Diffusion Test

2.4.5. Well Diffusion Test

2.4.6. Biofilm Assessment Test (Microtiter Dish Assay)

- Preparation of PBS Solution:

- Preparation of Extracts from Groups 1–6:

- The cultivation of seven bacterial strains in broth culture medium and the preparation of 0.5 McFarland concentration.

- Treatment with extracts from temporary filling materials and nanoclay: in each well containing the extract, 50 microliters of the bacterial suspension with a concentration of 0.5 McFarland was dispensed using a yellow sampler.

- Incubation: incubation was performed for 24 h, with the plates containing Escherichia coli and Streptococcus mutans placed in an incubator at 37 degrees Celsius, and the plates containing Enterococcus faecalis placed in a CO2 incubator at 37 degrees Celsius.

- Fluorescent biofilm staining: After incubation, the contents of the plates were carefully aspirated using a sterile pipette. To detach non-adherent bacteria, each well was washed three times with 200 microliters of sterile PBS. Subsequently, in each well, 200 microliters of 4% crystal violet was added. After 12 min, the excess dye was poured off, and the plates were washed under a gentle stream of distilled water.

- Recording biofilm absorption using the ELISA plate reader (Tecan EL-Reader, Männedorf, Switzerland): After washing the crystal violet, 200 microliters of 33% acetic acid solution was added to each well for 15 min. At this stage, the colors that had penetrated the biofilm were released, and then they were read using the ELISA instrument at a wavelength of 600 nanometers. The more bacterial biofilm remained, the more color it absorbed. Therefore, after adding acetic acid, it produced more color, ultimately registering a higher absorption in the ELISA instrument.

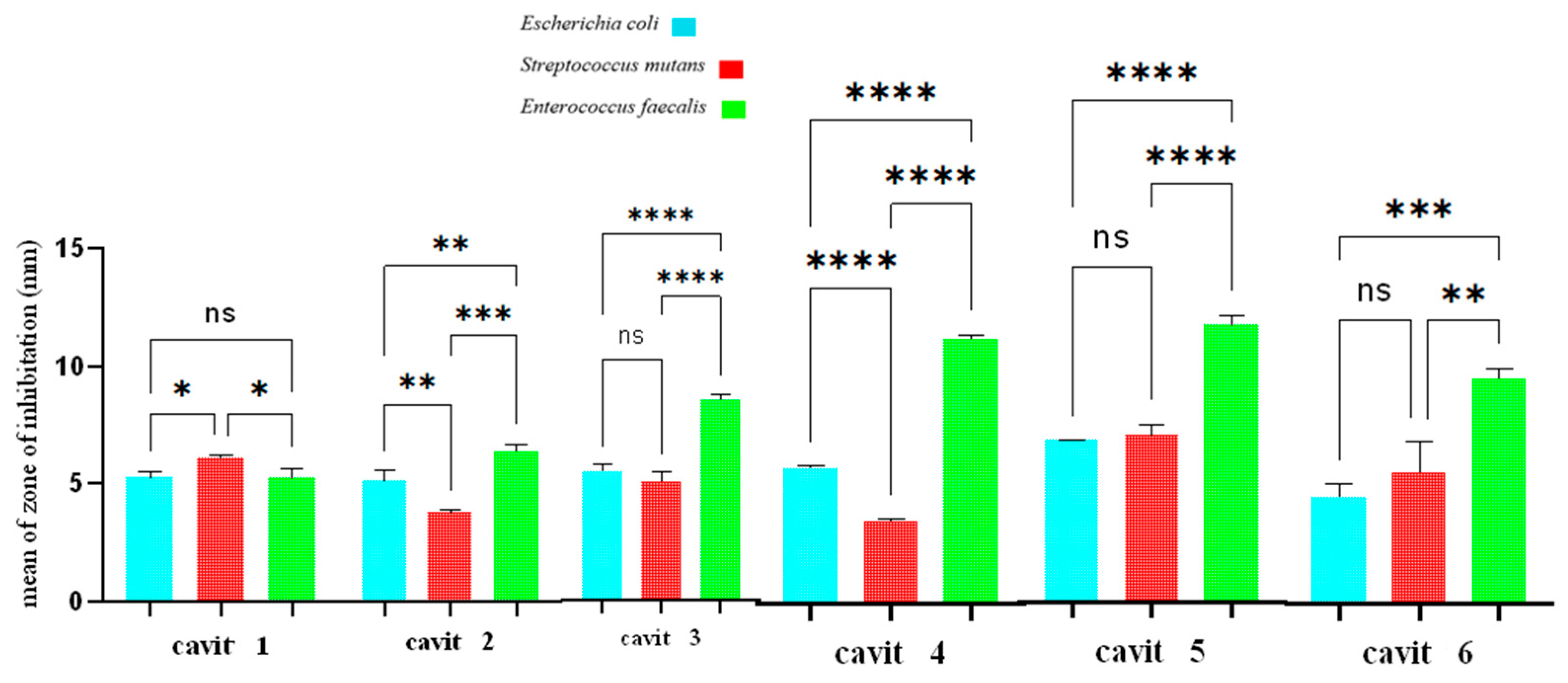

3. Results

3.1. Well Diffusion Test

3.2. Disk Diffusion Test

3.3. Microtiter Dish

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shahi, S.; Asl, A.M. In vitro comparison of coronal microleakage of four temporary restorative materials used in endodontic treatment. J. Dent. Med. 2008, 21, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Amorim, L.d.F.G.d.; Toledo, O.A.D.; Estrela, C.R.D.A.; Decurcio, D.D.A.; Estrela, C. Antimicrobial analysis of different root canal filling pastes used in pediatric dentistry by two experimental methods. Braz. Dent. J. 2006, 17, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggio, C.; Trovati, F.; Ceci, M.; Colombo, M.; Pietrocola, G. Antibacterial activity of different root canal sealers against Enterococcus faecalis. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2017, 9, e743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Queiroz, A.M.d.; Nelson Filho, P.; Silva, L.A.B.D.; Assed, S.; Silva, R.A.B.D.; Ito, I.Y. Antibacterial activity of root canal filling materials for primary teeth: Zinc oxide and eugenol cement, Calen paste thickened with zinc oxide, Sealapex and EndoREZ. Braz. Dent. J. 2009, 20, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazemisalman, B.; Niaz, S.; Darvish, S.; Notash, A.; Ramazani, A.; Luchian, I. The Antibacterial Properties of a Reinforced Zinc Oxide Eugenol Combined with Cloisite 5A Nanoclay: An In-Vitro Study. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vail, M.M.; Steffel, C.L. Preference of temporary restorations and spacers: A survey of Diplomates of the American Board of Endodontists. J. Endod. 2006, 32, 513–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naoum, H.; Chandler, N.P. Temporization for endodontics. Int. Endod. J. 2002, 35, 964–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, T.; Nomura, Y.; Tanaka, N.; Teshima, W.; Okazaki, M.; Shintani, H. Leachability of plasticizer and residual monomer from commercial temporary restorative resins. J. Dent. 2004, 32, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brännström, M.; Nordenvall, K. Bacterial penetration, pulpal reaction and the inner surface of Concise enamel bond. Composite fillings in etched and unetched cavities. J. Dent. Res. 1978, 57, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabinejad, M.; Ung, B.; Kettering, J.D. In vitro bacterial penetration of coronally unsealed endodontically treated teeth. J. Endod. 1990, 16, 566–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushashe, A.M.; Gonzaga, C.C.; Tomazinho, P.H.; da Cunha, L.F.; Leonardi, D.P.; Pissaia, J.F.; Correr, G.M. Antibacterial Effect and Physical-Mechanical Properties of Temporary Restorative Material Containing Antibacterial Agents. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2015, 2015, 697197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada, I.; Mico-Munoz, P.; Giner-Lluesma, T.; Mico-Martinez, P.; Collado-Castellano, N.; Manzano-Saiz, A. Influence of microbiology on endodontic failure. Literature review. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Y Cir. Bucal 2019, 24, e364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.M.; Morais, M.B.D.; Morais, T.B. A novel and potentially valuable exposure measure: Escherichia coli in oral cavity and its association with child daycare center attendance. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2012, 58, 517–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheiham, A. Dental caries affects body weight, growth and quality of life in pre-school children. Br. Dent. J. 2006, 201, 625–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Chu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, L.; Qian, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W. Recent advances on nanomaterials for antibacterial treatment of oral diseases. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 20, 100635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allaker, R.P.; Memarzadeh, K. Nanoparticles and the control of oral infections. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2014, 43, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temirek, M.M.; Abdelaziz, M.M.; Alshareef, W. Antibacterial Activity of Nanoclay-Modified Glass Ionomer versus Nanosilver-Modified Glass Ionomer. J. Int. Dent. Med. Res. 2022, 15, 1442–1449. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, D.R.; Robeson, L.M. Polymer nanotechnology: Nanocomposites. Polymer 2008, 49, 3187–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavinasab, S.M.; Atai, M.; Alavi, B. To compare the microleakage among experimental adhesives containing nanoclay fillers after the storages of 24 hours and 6 months. Open Dent. J. 2011, 5, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solhi, L.; Atai, M.; Nodehi, A.; Imani, M.; Ghaemi, A.; Khosravi, K. Poly (acrylic acid) grafted montmorillonite as novel fillers for dental adhesives: Synthesis, characterization and properties of the adhesive. Dent. Mater. 2012, 28, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Jana, S.C. The relationship between nano-and micro-structures and mechanical properties in PMMA–epoxy–nanoclay composites. Polymer 2003, 44, 2091–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritto, F.P.; da Silva, E.M.; Borges, A.L.S.; Borges, M.A.P.; Sampaio-Filho, H.R. Fabrication and characterization of low-shrinkage dental composites containing montmorillonite nanoclay. Odontology 2022, 110, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumara, P.P.; Deng, X.; Cooper, P.R.; Cathro, P.; Dias, G.; Gould, M.; Ratnayake, J. Montmorillonite in dentistry: A review of advances in research and potential clinical applications. Mater. Res. Express 2024, 11, 072001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramovitz, I.; Beyth, N.; Paz, Y.; I Weiss, E.; Matalon, S. Antibacterial temporary restorative materials incorporating polyethyleneimine nanoparticles. Quintessence Int. 2013, 44, 209–216. [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj, A.; Hossain, S.; Majhi, M.R. Preparation and characterization of clay bonded high strength silica refractory by utilizing agriculture waste. Bol. Soc. Esp. Cerám. Y Vidr. 2017, 56, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassel, M.O.; Khattab, M.A. Antibacterial activity against Streptococcus mutans and inhibition of bacterial induced enamel demineralization of propolis, miswak, and chitosan nanoparticles based dental varnishes. J. Adv. Res. 2017, 8, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, I.X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, I.S.; Mei, M.L.; Li, Q.; Chu, C.H. The antibacterial mechanism of silver nanoparticles and its application in dentistry. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 2555–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ebashree, H.S.; Kingsley, S.J.; Sathish, E.S.; Devapriya, D. Antimicrobial activity of few medicinal plants against clinically isolated human cariogenic pathogens—An in vitro study. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2011, 2011, 541421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanmohammadi, A.; Hassani, M.; Vahabi, S.; Salman, B.N.; Ramazani, A. In Vitro Antibacterial Activity Study of Doxycycline/Polymethacrylic Acid Coated Silk Suture. Fibers Polym. 2022, 23, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzaidy, F.A.; Khalifa, A.K.; Emera, R.M. The antimicrobial efficacy of nanosilver modified root canal sealer. Eur. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Barzegar, A.; Ghaffari, T. Nanoclay-reinforced polymethylmethacrylate and its mechanical properties. Dent. Res. J. 2018, 15, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fareed, M.A.; Stamboulis, A. Effect of nanoclay dispersion on the properties of a commercial glass ionomer cement. Int. J. Biomater. 2014, 2014, 685389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, J.M.; Danial, E.N. In vitro antibacterial activity and minimum inhibitory concentration of zinc oxide and nano-particle zinc oxide against pathogenic strains. J. Health Sci. 2012, 2, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yang, D.; Ting, V.P.; Hamerton, I.; Van Duijneveldt, J.S.; Rochat, S. Modified sepiolite nanoclays in advanced composites for engineering applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 19221–19232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.A.; Nguyen, T.H. Enhanced Mechanical Properties and Fire Resistance of Epoxy/Nanoclay Composite Coatings for Advanced Steel Protection. Trends Sci. 2025, 22, 10096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hala, F.; Mohammed, M.; Abd El-Fattah, H.; Thanaa, I. Antibacterial effect of two types of nano particles incorporated in zinc oxide based sealers on Enterococcus faecalis (in vitro study). Alex. Dent. J. 2016, 41, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Ge, S. Application of Antimicrobial Nanoparticles in Dentistry. Molecules 2019, 24, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanpour, M.; Mazloumi, M.; Nouri, A.; Lotfiman, S. Silver-doped nanoclay with antibacterial activity. J. Ultrafine Grained Nanostruct. Mater. 2017, 50, 124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Vanlalveni, C.; Lallianrawna, S.; Biswas, A.; Selvaraj, M.; Changmai, B.; Rokhum, S.L. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using plant extracts and their antimicrobial activities: A review of recent literature. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 2804–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaidka, S.; Somani, R.; Singh, D.J.; Sheikh, T.; Chaudhary, N.; Basheer, A. Herbal combat against E. faecalis—An in vitro study. J. Oral Biol. Craniofacial Res. 2017, 7, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thosar, N.R.; Chandak, M.; Bhat, M.; Basak, S. Evaluation of antimicrobial activity of two endodontic sealers: Zinc oxide with thyme oil and zinc oxide eugenol against root canal microorganisms—An in vitro study. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2018, 11, 79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barbosa-Ribeiro, M.; De-Jesus-Soares, A.; Zaia, A.A.; Ferraz, C.C.; Almeida, J.F.; Gomes, B.P. Antimicrobial susceptibility and characterization of virulence genes of Enterococcus faecalis isolates from teeth with failure of the endodontic treatment. J. Endod. 2016, 42, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Liu, Y.; Liao, T.; Yang, H. Nanoclay-Mediated Crystal-Phase Engineering in Biofunctions to Balance Antibacteriality and Cytotoxicity. Nano Lett. 2025, 25, 2009–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Bacterial Species | Cavity Groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Cavit3> | Cavit5> | Cavit2> | Cavit4> | Cavit1> | Cavit6 |

| S. mutans | Cavit5> | Cavit3= | Cavit1 | Cavit6> | Cavit2> | Cavit4 |

| E. faecalis | Cavit5> | Cavit3> | Cavit4> | Cavit6> | Cavit2> | Cavit1 |

| Bacterial Species | Cavity Groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Cavit6> | Cavit5> | Cavit4> | Cavit3> | Cavit2> | Cavit1 |

| S. mutans | Cavit5> | Cavit4> | Cavit3> | Cavit2> | Cavit6> | Cavit1 |

| E. faecalis | Cavit6> | Cavit5> | Cavit4> | Cavit2> | Cavit3> | Cavit1 |

| Bacterial Species | Cavity Groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Cavit4> | Cavit5> | Cavit6> | Cavit3> | Cavit2> | Cavit1 |

| S. mutans | Cavit6> | Cavit2> | Cavit3> | Cavit4> | Cavit5> | Cavit1 |

| E. faecalis | Cavit6> | Cavit1> | Cavit2> | Cavit3> | Cavit4> | Cavit5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nazemi Salman, B.; Notash, A.; Ramazani, A.; Niaz, S.; Naeimi, S.M.; Darvish, S.; Luchian, I. Antibacterial Characteristics of Nanoclay-Infused Cavit Temporary Filling Material: In Vitro Study. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 299. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16080299

Nazemi Salman B, Notash A, Ramazani A, Niaz S, Naeimi SM, Darvish S, Luchian I. Antibacterial Characteristics of Nanoclay-Infused Cavit Temporary Filling Material: In Vitro Study. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2025; 16(8):299. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16080299

Chicago/Turabian StyleNazemi Salman, Bahareh, Ayda Notash, Ali Ramazani, Shaghayegh Niaz, Seyed Mohammadrasoul Naeimi, Shayan Darvish, and Ionut Luchian. 2025. "Antibacterial Characteristics of Nanoclay-Infused Cavit Temporary Filling Material: In Vitro Study" Journal of Functional Biomaterials 16, no. 8: 299. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16080299

APA StyleNazemi Salman, B., Notash, A., Ramazani, A., Niaz, S., Naeimi, S. M., Darvish, S., & Luchian, I. (2025). Antibacterial Characteristics of Nanoclay-Infused Cavit Temporary Filling Material: In Vitro Study. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 16(8), 299. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16080299