Transforming Credit Risk Analysis: A Time-Series-Driven ResE-BiLSTM Framework for Post-Loan Default Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of Literature

2.1. Benchmark Datasets and Loan Default Prediction Model

2.2. Design of BiLSTM and Its Variants in Anomaly Detection

2.3. XAI in Loan Default Prediction

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Preprocessing

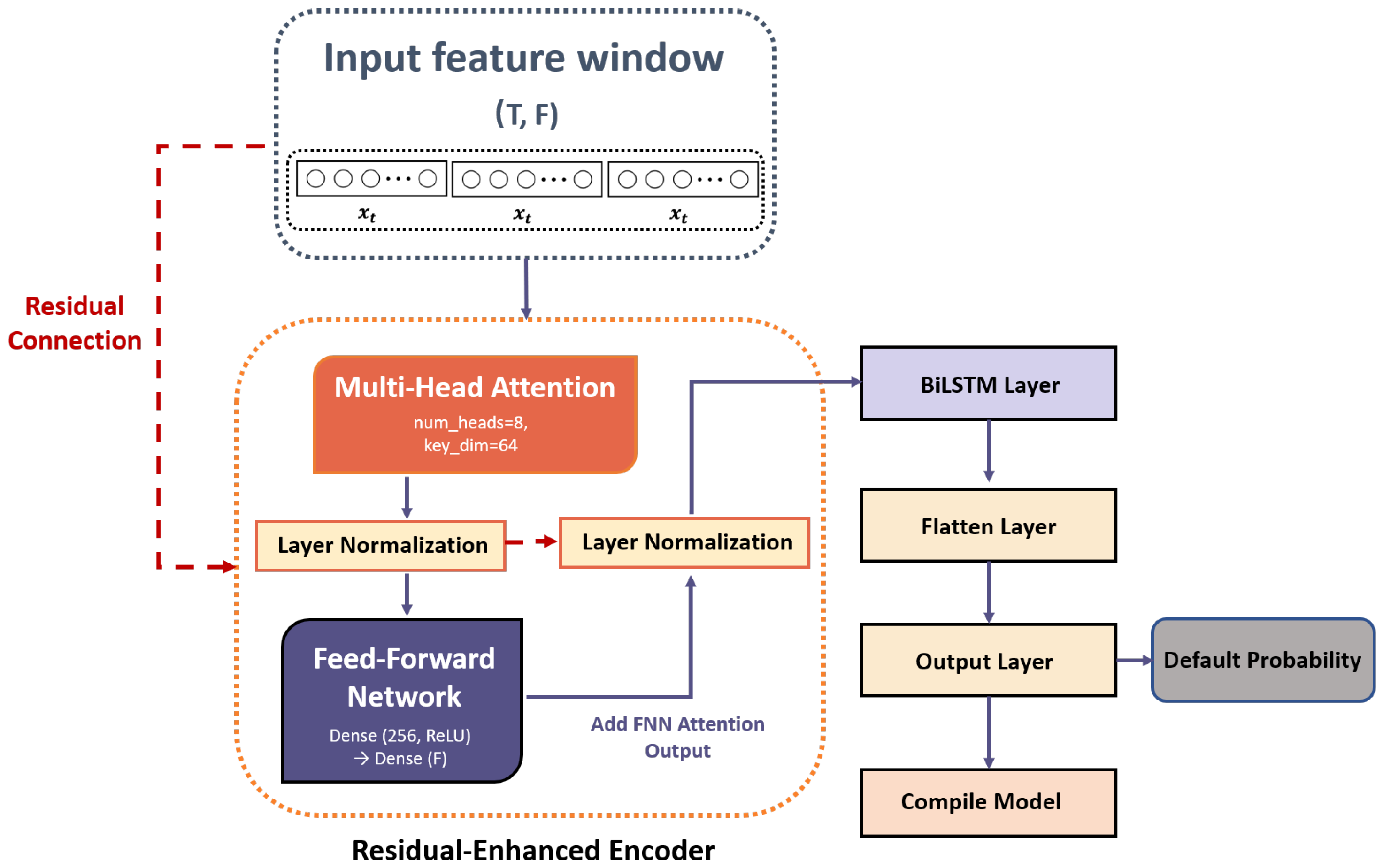

3.2. Proposed ResE-BiLSTM Model

| Algorithm 1: Pseudocode of the proposed ResE-BiLSTM |

|

3.2.1. Residual-Enhanced Encoder (ResE) Layer

- Multi-Head AttentionMulti-head attention [28] is a sophisticated attention mechanism integrating several attention processes in one model. It functions by projecting input into multiple subspaces via linear transformations with learned weight matrices. Each head processes its own transformed input independently, allowing the model to concentrate on different data aspects and grasp richer contextual details. This model utilizes a self-attention mechanism that computes attention using only the input, without external data. This method efficiently captures relationships and dependencies within the input sequence. Importantly, post-attention calculation maintains the output dimensionality consistent with the input, facilitating integration with subsequent layers.The query vector Q, key vector K, and value vector V are initially derived from linear transformations, with , , and , where X represents the input data and are weight matrices randomly initialized. The algorithm utilizes h attention heads to derive the attention matrix via the scaled dot product , where denotes the key vector dimension, and subsequently employs the softmax function to produce a probability distribution. The output for each attention head is derived by applying the attention weights to the value vector . Finally, combining the outputs from all attention heads and projecting back into the input space with completes the multi-head attention layer.

- Normalization Layer and Residual Connection MechanismThe normalization layer follows the multi-head attention and feed-forward network to improve model stability and performance. The residual connection in layer normalization ensures balanced input and layer output contributions [45], preserving essential information from earlier layers and enabling deeper layers to learn more complex features. Moreover, the normalization layer mitigates issues like vanishing and exploding gradients through output standardization, improving training stability. It also reduces the influence of input scale variations on parameter updates, speeding up convergence and optimizing the efficiency of the training process. The normalization layer operates as follows:where represents the mean of each feature, indicates their variance, is a small constant (set at 1 × 10−6) to avoid division by zero, as well as and are learnable parameters. As shown in Equation (1), layer normalization stabilizes the output distribution and improves training robustness.The residual connection mechanism incorporated within the ResE module plays a pivotal role in facilitating effective deep representation learning. Specifically, by introducing skip connections that directly add the input of a sub-layer (e.g., the multi-head attention or feed-forward layer) to its output prior to normalization, the model preserves the integrity of the original feature representations while enabling the training of deeper networks without degradation. This architectural design mitigates the vanishing gradient problem and ensures more stable and efficient gradient flow during backpropagation. Moreover, the integration of residual connections with layer normalization enhances the model’s capacity to learn complex temporal dependencies by stabilizing the output distributions across layers.

- Feed-Forward NetworkThe feed-forward network processes each time step independently, refining and improving the fine-grained features to improve feature representation [46]. Using the ReLU activation function, the network applies non-linear transformations to capture more intricate patterns and relationships within the data. The feed-forward network in this model features two layers. The initial layer is fully connected, containing 256 neurons and employing ReLU activation. The second layer reshapes the feature dimension to match the original input, maintaining compatibility with the BiLSTM layer. The resultant output is shaped as batch size, sequence length, feature dimension. This is followed by layer normalization applied to the combined outputs of the feed-forward network and attention layer, improving stability and robustness of the model.

3.2.2. BiLSTM

- Forward LSTM ProcessThe LSTM executes these operations at every time step:

- (a)

- Forget GateThis mechanism determines which part of the previous cell state () is preserved in the cell state. The forget gate governing this mechanism is defined in Equation (2):where is the sigmoid activation function mapping values to [0, 1], represents the weights for the forward forget gate, is the input data, denotes the prior hidden state, and is the forget gate bias.

- (b)

- Input GateThis operation determines the portion of current input () to be stored in the cell state. The input gate computation is defined by Equation (3):where is the weights for the forward input gate, is the hidden state from the preceding time step, is the bias term for the input gate.

- (c)

- Candidate Cell StateThis operation generates a candidate value () for potential updates to the cell state. As specified in Equation (4), this candidate value is computed by:where represents the weights for the candidate cell state, is the previous time step’s hidden state, and is the bias term for the candidate cell state.

- (d)

- Output GateThis operation delineates the cell state fraction impacting the hidden state (). The output gate is determined by Equation (5):where denotes the forward output gate weights, is the previous hidden state, and stands for the output gate bias.

- (e)

- Updated Cell StateThe current cell state is updated by integrating information from the forget gate, input gate, and candidate cell state, as formalized in Equation (6):where denotes the previous cell state, is the forget gate values, represents input gate values, and is the candidate cell state.

- (f)

- Updated Hidden StateThe updated hidden state is computed by applying the output gate to the newly updated cell state, as defined in Equation (7):

Following these six steps, the forward process refreshes the cell state () and the hidden state (), producing an output () through the output gate. - Backward LSTM ProcessThe backward LSTM functions similarly, but processes in reverse, beginning from to .

3.2.3. Flatten and Output Layers

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

4. Experiment Results Analysis

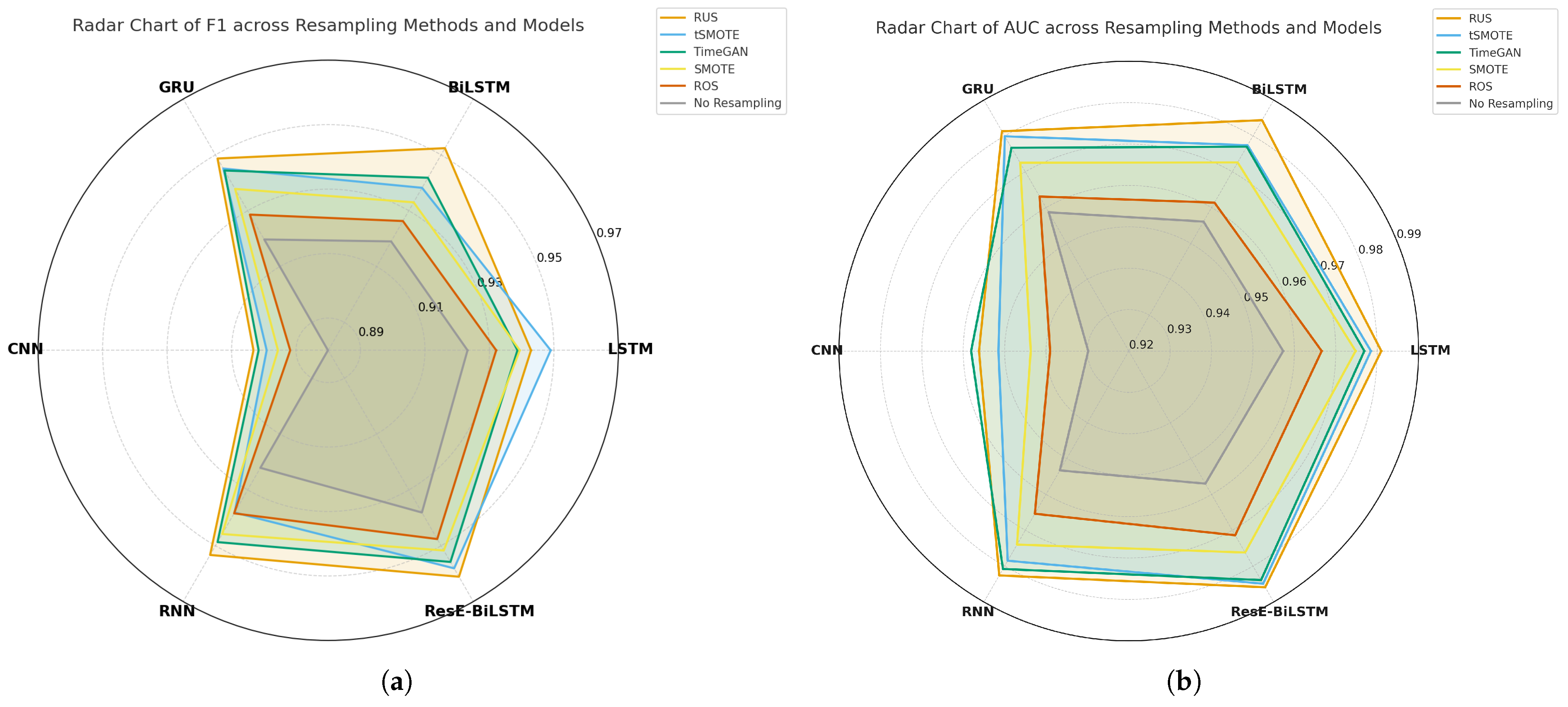

4.1. Resampling Methods Performance Analysis

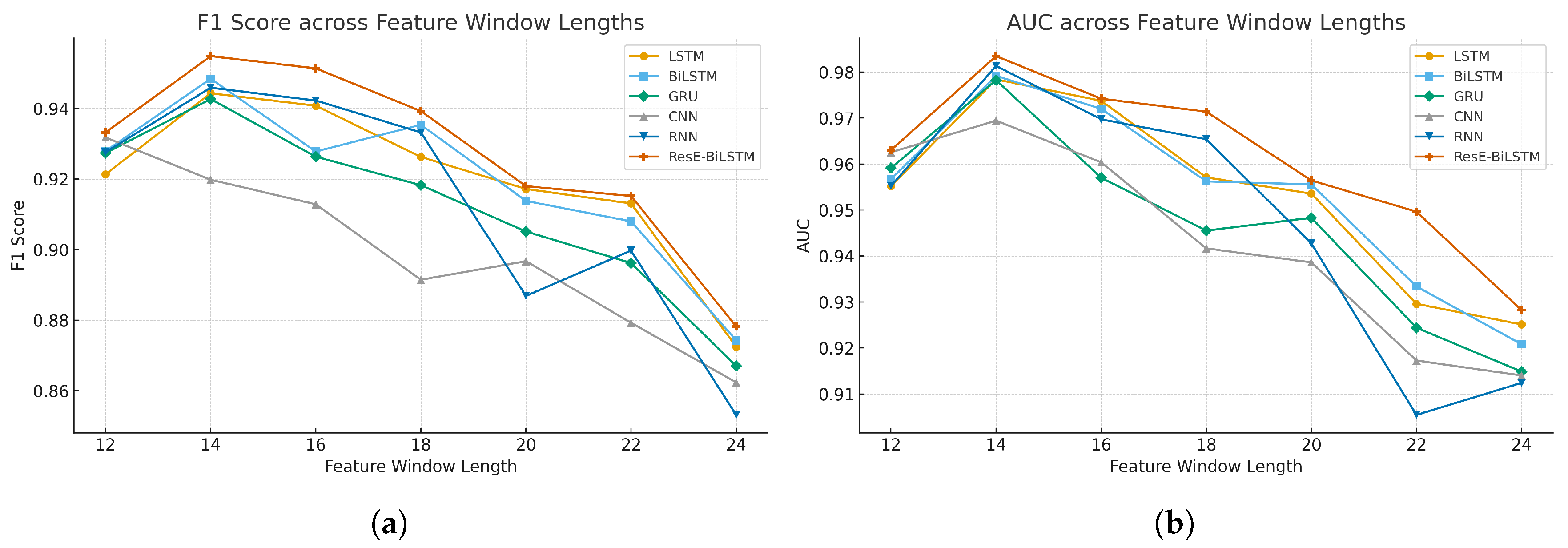

4.2. Feature Window Lengths Performance Analysis

4.3. ResE-BiLSTM Model Performance Analysis

4.3.1. AvgR Performance Analysis

4.3.2. Ranking Performance Grouped by Year

4.3.3. Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Tests

4.4. Ablation Study

4.5. Interpretability Performance Analysis

4.5.1. Barplot Analysis

4.5.2. SHAP Summary Plot Analysis

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Research Limitations

5.4. Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | Accuracy |

| AUC | Area under the ROC curve |

| BiGRU | Bidirectional gated recurrent unit |

| BiLSTM | Bidirectional long-short-term memory |

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| ELTV | Estimated loan to value |

| FN | False negative |

| FP | False positive |

| GRU | Gated recurrent unit |

| LIME | Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanation |

| LSTM | Long-short-term memory |

| ML | Machine learning |

| OOS | Out-of-sample |

| PR | Precision |

| RC | Recall |

| RNN | Recurrent neural network |

| SAN | Self-attention |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| TN | True negative |

| TP | True positive |

| UPB | Unpaid principal balance |

| XAI | Explainable artificial intelligence |

| XGB | Extreme gradient boosting |

Appendix A

| Cohort | LSTM [8] | BiLSTM [12] | GRU [56] | CNN [57] | RNN [58] | ResE-BiLSTM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009Q1 | 0.918 | 0.913 | 0.914 | 0.892 | 0.914 | 0.923 |

| 2009Q2 | 0.895 | 0.880 | 0.887 | 0.897 | 0.883 | 0.921 |

| 2009Q3 | 0.914 | 0.914 | 0.915 | 0.911 | 0.919 | 0.924 |

| 2009Q4 | 0.926 | 0.924 | 0.945 | 0.906 | 0.937 | 0.924 |

| 2010Q1 | 0.939 | 0.935 | 0.938 | 0.935 | 0.940 | 0.946 |

| 2010Q2 | 0.901 | 0.900 | 0.903 | 0.887 | 0.901 | 0.913 |

| 2010Q3 | 0.909 | 0.919 | 0.913 | 0.893 | 0.911 | 0.922 |

| 2010Q4 | 0.899 | 0.900 | 0.896 | 0.911 | 0.910 | 0.890 |

| 2011Q1 | 0.925 | 0.933 | 0.927 | 0.904 | 0.924 | 0.903 |

| 2011Q2 | 0.922 | 0.921 | 0.919 | 0.895 | 0.920 | 0.923 |

| 2011Q3 | 0.922 | 0.929 | 0.935 | 0.896 | 0.910 | 0.906 |

| 2011Q4 | 0.920 | 0.916 | 0.912 | 0.886 | 0.920 | 0.925 |

| 2012Q1 | 0.904 | 0.890 | 0.905 | 0.875 | 0.919 | 0.894 |

| 2012Q2 | 0.830 | 0.817 | 0.827 | 0.848 | 0.855 | 0.863 |

| 2012Q3 | 0.911 | 0.910 | 0.911 | 0.863 | 0.902 | 0.913 |

| 2012Q4 | 0.948 | 0.953 | 0.949 | 0.935 | 0.947 | 0.954 |

| 2013Q1 | 0.878 | 0.878 | 0.884 | 0.868 | 0.865 | 0.916 |

| 2013Q2 | 0.926 | 0.931 | 0.923 | 0.889 | 0.913 | 0.932 |

| 2013Q3 | 0.893 | 0.890 | 0.897 | 0.857 | 0.885 | 0.909 |

| 2013Q4 | 0.914 | 0.914 | 0.910 | 0.887 | 0.924 | 0.930 |

| 2014Q1 | 0.921 | 0.915 | 0.924 | 0.886 | 0.927 | 0.931 |

| 2014Q2 | 0.918 | 0.917 | 0.912 | 0.885 | 0.918 | 0.924 |

| 2014Q3 | 0.931 | 0.933 | 0.924 | 0.919 | 0.927 | 0.935 |

| 2014Q4 | 0.875 | 0.865 | 0.862 | 0.869 | 0.884 | 0.891 |

| 2015Q1 | 0.896 | 0.885 | 0.879 | 0.892 | 0.910 | 0.913 |

| 2015Q2 | 0.911 | 0.912 | 0.904 | 0.890 | 0.903 | 0.916 |

| 2015Q3 | 0.926 | 0.930 | 0.924 | 0.894 | 0.914 | 0.931 |

| 2015Q4 | 0.927 | 0.936 | 0.928 | 0.884 | 0.928 | 0.908 |

| 2016Q1 | 0.913 | 0.920 | 0.916 | 0.886 | 0.919 | 0.927 |

| 2016Q2 | 0.908 | 0.909 | 0.913 | 0.886 | 0.913 | 0.923 |

| 2016Q3 | 0.912 | 0.901 | 0.909 | 0.879 | 0.907 | 0.915 |

| 2016Q4 | 0.930 | 0.925 | 0.934 | 0.913 | 0.940 | 0.941 |

| 2017Q1 | 0.927 | 0.925 | 0.923 | 0.902 | 0.929 | 0.933 |

| 2017Q2 | 0.921 | 0.918 | 0.910 | 0.897 | 0.909 | 0.930 |

| 2017Q3 | 0.916 | 0.916 | 0.914 | 0.883 | 0.914 | 0.923 |

| 2017Q4 | 0.925 | 0.925 | 0.923 | 0.901 | 0.923 | 0.930 |

| 2018Q1 | 0.937 | 0.936 | 0.937 | 0.915 | 0.935 | 0.939 |

| 2018Q2 | 0.928 | 0.926 | 0.925 | 0.899 | 0.923 | 0.934 |

| 2018Q3 | 0.930 | 0.930 | 0.930 | 0.911 | 0.932 | 0.935 |

| 2018Q4 | 0.919 | 0.923 | 0.922 | 0.900 | 0.926 | 0.927 |

| 2019Q1 | 0.926 | 0.924 | 0.923 | 0.907 | 0.927 | 0.930 |

| 2019Q2 | 0.932 | 0.930 | 0.927 | 0.923 | 0.937 | 0.942 |

| 2019Q3 | 0.944 | 0.949 | 0.943 | 0.921 | 0.946 | 0.951 |

| 2019Q4 | 0.951 | 0.941 | 0.947 | 0.903 | 0.953 | 0.955 |

| Cohort | LSTM [8] | BiLSTM [12] | GRU [56] | CNN [57] | RNN [58] | ResE-BiLSTM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009Q1 | 0.950 | 0.949 | 0.945 | 0.950 | 0.950 | 0.951 |

| 2009Q2 | 0.897 | 0.881 | 0.892 | 0.901 | 0.885 | 0.953 |

| 2009Q3 | 0.921 | 0.919 | 0.922 | 0.925 | 0.922 | 0.927 |

| 2009Q4 | 0.964 | 0.951 | 0.965 | 0.959 | 0.964 | 0.956 |

| 2010Q1 | 0.978 | 0.980 | 0.977 | 0.974 | 0.982 | 0.983 |

| 2010Q2 | 0.895 | 0.893 | 0.900 | 0.888 | 0.904 | 0.915 |

| 2010Q3 | 0.894 | 0.919 | 0.911 | 0.896 | 0.917 | 0.920 |

| 2010Q4 | 0.923 | 0.921 | 0.915 | 0.970 | 0.954 | 0.919 |

| 2011Q1 | 0.929 | 0.928 | 0.935 | 0.915 | 0.915 | 0.862 |

| 2011Q2 | 0.969 | 0.973 | 0.976 | 0.934 | 0.985 | 0.988 |

| 2011Q3 | 0.941 | 0.935 | 0.954 | 0.949 | 0.908 | 0.902 |

| 2011Q4 | 0.940 | 0.925 | 0.919 | 0.945 | 0.956 | 0.935 |

| 2012Q1 | 0.893 | 0.863 | 0.893 | 0.859 | 0.923 | 0.863 |

| 2012Q2 | 0.785 | 0.770 | 0.783 | 0.807 | 0.816 | 0.828 |

| 2012Q3 | 0.920 | 0.919 | 0.916 | 0.851 | 0.932 | 0.933 |

| 2012Q4 | 0.985 | 0.985 | 0.983 | 0.971 | 0.979 | 0.990 |

| 2013Q1 | 0.854 | 0.852 | 0.862 | 0.879 | 0.834 | 0.911 |

| 2013Q2 | 0.981 | 0.987 | 0.978 | 0.922 | 0.981 | 0.980 |

| 2013Q3 | 0.869 | 0.865 | 0.877 | 0.829 | 0.855 | 0.903 |

| 2013Q4 | 0.919 | 0.913 | 0.918 | 0.901 | 0.937 | 0.920 |

| 2014Q1 | 0.931 | 0.917 | 0.939 | 0.883 | 0.946 | 0.948 |

| 2014Q2 | 0.930 | 0.929 | 0.925 | 0.931 | 0.944 | 0.936 |

| 2014Q3 | 0.952 | 0.950 | 0.939 | 0.945 | 0.945 | 0.949 |

| 2014Q4 | 0.850 | 0.834 | 0.827 | 0.872 | 0.870 | 0.874 |

| 2015Q1 | 0.875 | 0.854 | 0.847 | 0.892 | 0.905 | 0.901 |

| 2015Q2 | 0.925 | 0.923 | 0.919 | 0.922 | 0.913 | 0.936 |

| 2015Q3 | 0.932 | 0.938 | 0.926 | 0.890 | 0.912 | 0.936 |

| 2015Q4 | 0.931 | 0.946 | 0.935 | 0.910 | 0.940 | 0.941 |

| 2016Q1 | 0.928 | 0.935 | 0.928 | 0.905 | 0.961 | 0.941 |

| 2016Q2 | 0.916 | 0.928 | 0.927 | 0.887 | 0.921 | 0.941 |

| 2016Q3 | 0.915 | 0.893 | 0.907 | 0.881 | 0.904 | 0.929 |

| 2016Q4 | 0.950 | 0.939 | 0.954 | 0.933 | 0.971 | 0.958 |

| 2017Q1 | 0.955 | 0.941 | 0.938 | 0.934 | 0.955 | 0.957 |

| 2017Q2 | 0.926 | 0.913 | 0.898 | 0.927 | 0.894 | 0.939 |

| 2017Q3 | 0.943 | 0.944 | 0.941 | 0.925 | 0.942 | 0.947 |

| 2017Q4 | 0.956 | 0.957 | 0.950 | 0.927 | 0.959 | 0.961 |

| 2018Q1 | 0.977 | 0.975 | 0.976 | 0.943 | 0.979 | 0.963 |

| 2018Q2 | 0.958 | 0.953 | 0.957 | 0.914 | 0.955 | 0.963 |

| 2018Q3 | 0.968 | 0.963 | 0.965 | 0.939 | 0.970 | 0.964 |

| 2018Q4 | 0.915 | 0.927 | 0.923 | 0.903 | 0.938 | 0.940 |

| 2019Q1 | 0.957 | 0.956 | 0.958 | 0.932 | 0.958 | 0.947 |

| 2019Q2 | 0.911 | 0.909 | 0.904 | 0.926 | 0.922 | 0.931 |

| 2019Q3 | 0.940 | 0.953 | 0.940 | 0.930 | 0.949 | 0.967 |

| 2019Q4 | 0.940 | 0.918 | 0.929 | 0.897 | 0.949 | 0.953 |

| Cohort | LSTM [8] | BiLSTM [12] | GRU [56] | CNN [57] | RNN [58] | ResE-BiLSTM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009Q1 | 0.883 | 0.872 | 0.880 | 0.829 | 0.874 | 0.883 |

| 2009Q2 | 0.892 | 0.880 | 0.881 | 0.892 | 0.879 | 0.896 |

| 2009Q3 | 0.905 | 0.909 | 0.907 | 0.894 | 0.915 | 0.921 |

| 2009Q4 | 0.886 | 0.894 | 0.923 | 0.849 | 0.908 | 0.889 |

| 2010Q1 | 0.898 | 0.889 | 0.897 | 0.894 | 0.896 | 0.908 |

| 2010Q2 | 0.910 | 0.909 | 0.906 | 0.887 | 0.897 | 0.911 |

| 2010Q3 | 0.929 | 0.918 | 0.916 | 0.891 | 0.905 | 0.934 |

| 2010Q4 | 0.870 | 0.876 | 0.873 | 0.847 | 0.861 | 0.856 |

| 2011Q1 | 0.921 | 0.938 | 0.918 | 0.892 | 0.936 | 0.961 |

| 2011Q2 | 0.873 | 0.866 | 0.860 | 0.851 | 0.854 | 0.874 |

| 2011Q3 | 0.902 | 0.923 | 0.915 | 0.837 | 0.914 | 0.912 |

| 2011Q4 | 0.897 | 0.907 | 0.905 | 0.820 | 0.880 | 0.914 |

| 2012Q1 | 0.917 | 0.927 | 0.922 | 0.900 | 0.913 | 0.937 |

| 2012Q2 | 0.914 | 0.907 | 0.908 | 0.916 | 0.919 | 0.922 |

| 2012Q3 | 0.900 | 0.899 | 0.905 | 0.881 | 0.868 | 0.912 |

| 2012Q4 | 0.910 | 0.920 | 0.914 | 0.897 | 0.913 | 0.928 |

| 2013Q1 | 0.912 | 0.914 | 0.915 | 0.854 | 0.912 | 0.922 |

| 2013Q2 | 0.869 | 0.873 | 0.865 | 0.851 | 0.843 | 0.883 |

| 2013Q3 | 0.925 | 0.926 | 0.925 | 0.900 | 0.928 | 0.917 |

| 2013Q4 | 0.909 | 0.915 | 0.900 | 0.870 | 0.908 | 0.941 |

| 2014Q1 | 0.910 | 0.912 | 0.908 | 0.891 | 0.905 | 0.913 |

| 2014Q2 | 0.903 | 0.904 | 0.897 | 0.831 | 0.890 | 0.910 |

| 2014Q3 | 0.909 | 0.913 | 0.907 | 0.891 | 0.907 | 0.920 |

| 2014Q4 | 0.911 | 0.912 | 0.917 | 0.866 | 0.902 | 0.919 |

| 2015Q1 | 0.924 | 0.928 | 0.929 | 0.894 | 0.916 | 0.932 |

| 2015Q2 | 0.895 | 0.898 | 0.887 | 0.853 | 0.891 | 0.899 |

| 2015Q3 | 0.918 | 0.921 | 0.921 | 0.898 | 0.917 | 0.926 |

| 2015Q4 | 0.923 | 0.925 | 0.921 | 0.853 | 0.915 | 0.931 |

| 2016Q1 | 0.895 | 0.902 | 0.902 | 0.863 | 0.873 | 0.904 |

| 2016Q2 | 0.898 | 0.888 | 0.896 | 0.886 | 0.903 | 0.890 |

| 2016Q3 | 0.909 | 0.911 | 0.913 | 0.877 | 0.911 | 0.897 |

| 2016Q4 | 0.909 | 0.909 | 0.913 | 0.891 | 0.906 | 0.923 |

| 2017Q1 | 0.897 | 0.906 | 0.906 | 0.867 | 0.901 | 0.907 |

| 2017Q2 | 0.916 | 0.924 | 0.925 | 0.864 | 0.927 | 0.930 |

| 2017Q3 | 0.885 | 0.884 | 0.884 | 0.833 | 0.882 | 0.896 |

| 2017Q4 | 0.891 | 0.890 | 0.893 | 0.871 | 0.885 | 0.907 |

| 2018Q1 | 0.896 | 0.894 | 0.896 | 0.884 | 0.889 | 0.908 |

| 2018Q2 | 0.895 | 0.896 | 0.891 | 0.882 | 0.889 | 0.903 |

| 2018Q3 | 0.890 | 0.894 | 0.892 | 0.879 | 0.891 | 0.904 |

| 2018Q4 | 0.923 | 0.918 | 0.920 | 0.896 | 0.913 | 0.923 |

| 2019Q1 | 0.892 | 0.888 | 0.885 | 0.878 | 0.895 | 0.911 |

| 2019Q2 | 0.957 | 0.957 | 0.957 | 0.920 | 0.955 | 0.958 |

| 2019Q3 | 0.948 | 0.944 | 0.946 | 0.910 | 0.942 | 0.942 |

| 2019Q4 | 0.964 | 0.969 | 0.968 | 0.910 | 0.957 | 0.970 |

| Cohort | LSTM [8] | BiLSTM [12] | GRU [56] | CNN [57] | RNN [58] | ResE-BiLSTM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009Q1 | 0.915 | 0.909 | 0.911 | 0.885 | 0.910 | 0.916 |

| 2009Q2 | 0.894 | 0.880 | 0.886 | 0.896 | 0.882 | 0.924 |

| 2009Q3 | 0.913 | 0.914 | 0.914 | 0.909 | 0.919 | 0.924 |

| 2009Q4 | 0.923 | 0.921 | 0.943 | 0.900 | 0.935 | 0.921 |

| 2010Q1 | 0.936 | 0.932 | 0.935 | 0.932 | 0.937 | 0.944 |

| 2010Q2 | 0.902 | 0.901 | 0.903 | 0.887 | 0.900 | 0.913 |

| 2010Q3 | 0.911 | 0.918 | 0.914 | 0.893 | 0.911 | 0.927 |

| 2010Q4 | 0.896 | 0.898 | 0.894 | 0.904 | 0.905 | 0.886 |

| 2011Q1 | 0.925 | 0.933 | 0.926 | 0.903 | 0.925 | 0.909 |

| 2011Q2 | 0.918 | 0.916 | 0.914 | 0.890 | 0.915 | 0.927 |

| 2011Q3 | 0.921 | 0.929 | 0.934 | 0.889 | 0.911 | 0.907 |

| 2011Q4 | 0.918 | 0.916 | 0.911 | 0.877 | 0.916 | 0.924 |

| 2012Q1 | 0.905 | 0.894 | 0.907 | 0.878 | 0.918 | 0.898 |

| 2012Q2 | 0.844 | 0.833 | 0.840 | 0.858 | 0.864 | 0.873 |

| 2012Q3 | 0.910 | 0.909 | 0.911 | 0.865 | 0.899 | 0.922 |

| 2012Q4 | 0.946 | 0.951 | 0.947 | 0.932 | 0.945 | 0.958 |

| 2013Q1 | 0.882 | 0.882 | 0.887 | 0.866 | 0.871 | 0.917 |

| 2013Q2 | 0.921 | 0.927 | 0.918 | 0.885 | 0.907 | 0.929 |

| 2013Q3 | 0.896 | 0.894 | 0.900 | 0.863 | 0.890 | 0.910 |

| 2013Q4 | 0.914 | 0.914 | 0.909 | 0.885 | 0.922 | 0.930 |

| 2014Q1 | 0.920 | 0.915 | 0.923 | 0.887 | 0.925 | 0.930 |

| 2014Q2 | 0.916 | 0.916 | 0.911 | 0.878 | 0.916 | 0.923 |

| 2014Q3 | 0.930 | 0.932 | 0.922 | 0.917 | 0.925 | 0.934 |

| 2014Q4 | 0.879 | 0.871 | 0.869 | 0.869 | 0.886 | 0.896 |

| 2015Q1 | 0.899 | 0.890 | 0.885 | 0.892 | 0.910 | 0.916 |

| 2015Q2 | 0.909 | 0.910 | 0.903 | 0.886 | 0.902 | 0.917 |

| 2015Q3 | 0.925 | 0.929 | 0.923 | 0.894 | 0.914 | 0.931 |

| 2015Q4 | 0.927 | 0.935 | 0.928 | 0.880 | 0.927 | 0.936 |

| 2016Q1 | 0.911 | 0.918 | 0.914 | 0.884 | 0.915 | 0.922 |

| 2016Q2 | 0.907 | 0.907 | 0.911 | 0.886 | 0.912 | 0.915 |

| 2016Q3 | 0.912 | 0.902 | 0.910 | 0.879 | 0.907 | 0.913 |

| 2016Q4 | 0.929 | 0.924 | 0.933 | 0.911 | 0.938 | 0.940 |

| 2017Q1 | 0.925 | 0.923 | 0.922 | 0.898 | 0.927 | 0.931 |

| 2017Q2 | 0.921 | 0.918 | 0.911 | 0.894 | 0.910 | 0.935 |

| 2017Q3 | 0.913 | 0.913 | 0.911 | 0.876 | 0.911 | 0.921 |

| 2017Q4 | 0.922 | 0.922 | 0.921 | 0.898 | 0.920 | 0.933 |

| 2018Q1 | 0.934 | 0.933 | 0.934 | 0.913 | 0.931 | 0.935 |

| 2018Q2 | 0.925 | 0.924 | 0.923 | 0.897 | 0.921 | 0.932 |

| 2018Q3 | 0.927 | 0.927 | 0.927 | 0.908 | 0.929 | 0.933 |

| 2018Q4 | 0.919 | 0.922 | 0.922 | 0.899 | 0.925 | 0.931 |

| 2019Q1 | 0.923 | 0.921 | 0.920 | 0.904 | 0.925 | 0.928 |

| 2019Q2 | 0.934 | 0.932 | 0.930 | 0.923 | 0.938 | 0.944 |

| 2019Q3 | 0.944 | 0.948 | 0.943 | 0.920 | 0.945 | 0.954 |

| 2019Q4 | 0.952 | 0.943 | 0.948 | 0.903 | 0.953 | 0.961 |

| Cohort | LSTM [8] | BiLSTM [12] | GRU [56] | CNN [57] | RNN [58] | ResE-BiLSTM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009Q1 | 0.968 | 0.967 | 0.969 | 0.954 | 0.964 | 0.971 |

| 2009Q2 | 0.955 | 0.956 | 0.958 | 0.952 | 0.948 | 0.969 |

| 2009Q3 | 0.970 | 0.971 | 0.969 | 0.966 | 0.971 | 0.972 |

| 2009Q4 | 0.977 | 0.976 | 0.980 | 0.963 | 0.979 | 0.972 |

| 2010Q1 | 0.985 | 0.983 | 0.983 | 0.977 | 0.985 | 0.986 |

| 2010Q2 | 0.957 | 0.958 | 0.961 | 0.946 | 0.955 | 0.963 |

| 2010Q3 | 0.970 | 0.970 | 0.968 | 0.957 | 0.964 | 0.972 |

| 2010Q4 | 0.963 | 0.965 | 0.952 | 0.975 | 0.957 | 0.955 |

| 2011Q1 | 0.972 | 0.975 | 0.970 | 0.962 | 0.972 | 0.974 |

| 2011Q2 | 0.973 | 0.973 | 0.975 | 0.964 | 0.979 | 0.981 |

| 2011Q3 | 0.967 | 0.969 | 0.971 | 0.960 | 0.964 | 0.966 |

| 2011Q4 | 0.968 | 0.966 | 0.965 | 0.958 | 0.971 | 0.973 |

| 2012Q1 | 0.968 | 0.967 | 0.970 | 0.943 | 0.972 | 0.966 |

| 2012Q2 | 0.930 | 0.925 | 0.930 | 0.928 | 0.943 | 0.945 |

| 2012Q3 | 0.969 | 0.971 | 0.968 | 0.938 | 0.965 | 0.974 |

| 2012Q4 | 0.975 | 0.976 | 0.979 | 0.973 | 0.979 | 0.981 |

| 2013Q1 | 0.956 | 0.959 | 0.960 | 0.931 | 0.955 | 0.962 |

| 2013Q2 | 0.977 | 0.977 | 0.978 | 0.959 | 0.977 | 0.979 |

| 2013Q3 | 0.958 | 0.958 | 0.959 | 0.938 | 0.951 | 0.960 |

| 2013Q4 | 0.968 | 0.968 | 0.967 | 0.949 | 0.972 | 0.974 |

| 2014Q1 | 0.969 | 0.968 | 0.970 | 0.949 | 0.972 | 0.973 |

| 2014Q2 | 0.970 | 0.970 | 0.967 | 0.948 | 0.972 | 0.977 |

| 2014Q3 | 0.968 | 0.970 | 0.965 | 0.964 | 0.970 | 0.971 |

| 2014Q4 | 0.952 | 0.951 | 0.946 | 0.932 | 0.949 | 0.953 |

| 2015Q1 | 0.961 | 0.958 | 0.957 | 0.948 | 0.964 | 0.966 |

| 2015Q2 | 0.962 | 0.962 | 0.960 | 0.949 | 0.959 | 0.963 |

| 2015Q3 | 0.966 | 0.965 | 0.963 | 0.948 | 0.960 | 0.967 |

| 2015Q4 | 0.971 | 0.972 | 0.971 | 0.946 | 0.970 | 0.965 |

| 2016Q1 | 0.957 | 0.965 | 0.965 | 0.948 | 0.965 | 0.969 |

| 2016Q2 | 0.952 | 0.950 | 0.952 | 0.944 | 0.953 | 0.949 |

| 2016Q3 | 0.959 | 0.955 | 0.960 | 0.939 | 0.956 | 0.958 |

| 2016Q4 | 0.966 | 0.964 | 0.967 | 0.960 | 0.971 | 0.971 |

| 2017Q1 | 0.960 | 0.960 | 0.960 | 0.952 | 0.962 | 0.970 |

| 2017Q2 | 0.960 | 0.962 | 0.959 | 0.945 | 0.959 | 0.963 |

| 2017Q3 | 0.958 | 0.960 | 0.957 | 0.938 | 0.959 | 0.964 |

| 2017Q4 | 0.963 | 0.964 | 0.962 | 0.946 | 0.961 | 0.973 |

| 2018Q1 | 0.969 | 0.970 | 0.969 | 0.960 | 0.971 | 0.972 |

| 2018Q2 | 0.967 | 0.966 | 0.966 | 0.953 | 0.967 | 0.969 |

| 2018Q3 | 0.965 | 0.967 | 0.967 | 0.956 | 0.969 | 0.973 |

| 2018Q4 | 0.970 | 0.969 | 0.969 | 0.959 | 0.971 | 0.973 |

| 2019Q1 | 0.975 | 0.973 | 0.974 | 0.968 | 0.978 | 0.978 |

| 2019Q2 | 0.980 | 0.980 | 0.979 | 0.972 | 0.980 | 0.983 |

| 2019Q3 | 0.978 | 0.979 | 0.978 | 0.969 | 0.981 | 0.983 |

| 2019Q4 | 0.984 | 0.980 | 0.982 | 0.956 | 0.983 | 0.986 |

References

- Hilal, W.; Gadsden, S.A.; Yawney, J. Financial Fraud: A Review of Anomaly Detection Techniques and Recent Advances. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 193, 116429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hashedi, K.G.; Al-Hashedi, K.G.; Magalingam, P.; Magalingam, P. Financial fraud detection applying data mining techniques: A comprehensive review from 2009 to 2019. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2021, 40, 100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, C.C.; Yang, Y.; Bellotti, A.; Hua, X. Machine Learning for Chinese Corporate Fraud Prediction: Segmented Models Based on Optimal Training Windows. Information 2025, 16, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Wang, S.; Liu, B.; Liu, P. How fintech impacts pre- and post-loan risk in Chinese commercial banks. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2020, 27, 2514–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Pant, V.; Kumar, S.; Bansal, P.K. Bank Loan Prediction System using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 9th International Conference System Modeling and Advancement in Research Trends (SMART), Moradabad, India, 4–5 December 2020; pp. 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaan, M.; Kumar, A.; Keshri, C.; Jain, R.; Nagrath, P. Loan default prediction using decision trees and random forest: A comparative study. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1022, 012042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmasry, M. Machine Learning Approach for Credit Score Analysis: A Case Study of Predicting Mortgage Loan Defaults. Master’s Thesis, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Q.; Shi, R.; Fan, T.; Ma, Y.; Huang, J. Prediction of Financial Time Series Based on LSTM Using Wavelet Transform and Singular Spectrum Analysis. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 9942410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardeshi, K.; Gill, S.S.; Abdelmoniem, A.M. Stock Market Price Prediction: A Hybrid LSTM and Sequential Self-Attention based Approach. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Yang, X.; Zhao, Y. Rural micro-credit model design and credit risk assessment via improved LSTM algorithm. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2023, 9, e1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siami-Namini, S.; Siami-Namini, S.; Tavakoli, N.; Tavakoli, N.; Namin, A.S.; Namin, A.S. A Comparative Analysis of Forecasting Financial Time Series Using ARIMA, LSTM, and BiLSTM. arXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siami-Namini, S.; Tavakoli, N.; Namin, A.S. The Performance of LSTM and BiLSTM in Forecasting Time Series. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 9–12 December 2019; pp. 3285–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y. Explainable AI Methods for Credit Card Fraud Detection: Evaluation of LIME and SHAP Through a User Study. Master’s Thesis, University of Skövde, Skövde, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sai, C.V.; Das, D.; Elmitwally, N.; Elezaj, O.; Islam, M.B. Explainable AI-Driven Financial Transaction Fraud Detection Using Machine Learning and Deep Neural Networks. SSRN 2023, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mac, F. Freddie Mac Dataset. 2024. Available online: https://www.freddiemac.com/research/datasets/sf-loanlevel-dataset (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Van Leeuwen, M. A Survey on Explainable Anomaly Detection. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 2023, 18, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LendingClub. Lending-Club Dataset. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/matmcreative/Lending-Club-Loan-Analysis/ (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Zandi, S.; Korangi, K.; Óskarsdóttir, M.; Mues, C.; Bravo, C. Attention-based Dynamic Multilayer Graph Neural Networks for Loan Default Prediction. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Bellotti, A.; Qu, R.; Bai, R. Discrete-Time Survival Models with Neural Networks for Age–Period–Cohort Analysis of Credit Risk. Risks 2024, 12, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthika, J.; Senthilselvi, A. An integration of deep learning model with Navo Minority Over-Sampling Technique to detect the frauds in credit cards. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 21757–21774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanimozhi, P.; Parkavi, S.; Kumar, T.A. Predicting Mortgage-Backed Securities Prepayment Risk Using Machine Learning Models. In Proceedings of the 2023 2nd International Conference on Smart Technologies and Systems for Next Generation Computing (ICSTSN), Villupuram, India, 21–22 April 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, C.; Hu, T.; Li, B. A BiLSTM-Attention Model for Detecting Smart Contract Defects More Accurately. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Software Quality, Reliability and Security, Guangzhou, China, 5–9 December 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, V.; Ganapathisamy, S. Hybrid Sampling and Similarity Attention Layer in Bidirectional Long Short Term Memory in Credit Card Fraud Detection. Int. J. Intell. Eng. Syst. 2022, 15, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Iqbal, M.; Mitra, B.; Kumar, V.; Lal, N. Hybrid CNN-BILSTM-Attention Based Identification and Prevention System for Banking Transactions. Nat. Volatiles Essent. Oils 2021, 8, 2552–2560. [Google Scholar]

- Joy, B.; R, D. A Tensor Based Approach for Click Fraud Detection on Online Advertising Using BiLSTM and Attention based CNN. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Self Sustainable Artificial Intelligence Systems (ICSSAS), Erode, India, 18–20 October 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakar, K.; Giridhar, M.S.; Amrita, T.; Joshi, T.M.; Pal, S.; Aswal, U. Comparative Evaluation of Fraud Detection in Online Payments Using CNN-BiGRU-A Approach. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Self Sustainable Artificial Intelligence Systems (ICSSAS), Erode, India, 18–20 October 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, NIPS’17, Red Hook, NY, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, T.; Cai, T.; Yu, B.; Yu, B.; Xu, W.; Xu, W. Transformer-Based BiLSTM for Aspect-Level Sentiment Classification. In Proceedings of the 2021 4th International Conference on Robotics, Control and Automation Engineering (RCAE), Wuhan, China, 4–6 November 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussougou, M.K.M.; Park, D. Attention-Based 1D CNN-BiLSTM Hybrid Model Enhanced with FastText Word Embedding for Korean Voice Phishing Detection. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Jia, X.; Zhang, W.; Sheng, V.S. A New Distributed Log Anomaly Detection Method based on Message Middleware and ATT-GRU. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. 2023, 17, 486–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALMahadin, G.; Aoudni, Y.; Shabaz, M.; Agrawal, A.V.; Yasmin, G.; Alomari, E.S.; Al-Khafaji, H.M.R.; Dansana, D.; Maaliw, R.R. VANET Network Traffic Anomaly Detection Using GRU-Based Deep Learning Model. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 70, 4548–4555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mill, E.; Garn, W.; Ryman-Tubb, N.F.; Turner, C.J. Opportunities in Real Time Fraud Detection: An Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) Research Agenda. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2023, 14, 1172–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, Z.; Kaldykhanov, D.; Tolep, K.K.; Park, J.G. A Machine Learning Model Selection considering Tradeoffs between Accuracy and Interpretability. In Proceedings of the 2021 13th International Conference on Information Technology and Electrical Engineering (ICITEE), Chiang Mai, Thailand, 14–15 October 2021; pp. 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raval, J.; Bhattacharya, P.; Jadav, N.K.; Tanwar, S.; Sharma, G.; Bokoro, P.N.; Elmorsy, M.; Tolba, A.; Raboaca, M.S. RaKShA: A Trusted Explainable LSTM Model to Classify Fraud Patterns on Credit Card Transactions. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS). Basel II: International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards. 2006. Available online: https://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs128.htm (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Menggang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Ming, L.; Jia, X.; Liu, R.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y. Internet Financial Credit Risk Assessment with Sliding Window and Attention Mechanism LSTM Model. Teh. Vjesn.—Tech. Gaz. 2023, 30, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, A.; Qazani, M.R.C.; Jewel Rana, B.; Akter, S.; Mohajerzadeh, A.; Sathi, N.J.; Ali, L.E.; Khan, M.S.; Asadi, H. SMOTE-ENN resampling technique with Bayesian optimization for multi-class classification of dry bean varieties. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 181, 113467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, A.; Molani, S.; Wei, Q.; Hadlock, J. Imputing missing observations with time sliced synthetic minority oversampling technique. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.05634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, C. Enhancing Financial Time-Series Analysis with TimeGAN: A Novel Approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 9th International Conference on Computer Science and Engineering (UBMK), Antalya, Turkiye, 26–28 October 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 447–450. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W.; Jeon, J.; Kim, S.; Jang, M.; Lee, H.; Yoo, S.; Oh, K.J. Prediction of index futures movement using TimeGAN and 3D-CNN: Empirical evidence from Korea and the United States. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 171, 112748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Park, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, H. Are self-attentions effective for time series forecasting? Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 114180–114209. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, C.; Zhou, X.; Pei, Y.; Wei, C. RCSAN residual enhanced channel spatial attention network for stock price forecasting. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ba, J.L.; Kiros, J.R.; Hinton, G.E. Layer Normalization. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1607.06450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Zhang, T.; Huang, J. Advanced hybrid LSTM-transformer architecture for real-time multi-task prediction in engineering systems. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.; Paliwal, K.K. Bidirectional recurrent neural networks. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 1997, 45, 2673–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, R.; Rawashdeh, J.; Abdullah, M. Machine Learning with Oversampling and Undersampling Techniques: Overview Study and Experimental Results. In Proceedings of the 2020 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Systems (ICICS), Irbid, Jordan, 7–9 April 2020; pp. 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamseddine, E.; Mansouri, N.; Soui, M.; Abed, M. Handling class imbalance in COVID-19 chest X-ray images classification: Using SMOTE and weighted loss. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 129, 109588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, Q.H.; Mai, S.H.; Do, Q.T.; Thai, D.K. A cluster-based data splitting method for small sample and class imbalance problems in impact damage classification. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 120, 108628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Cai, Y.; Li, Y. Oversampling Method for Imbalanced Classification. Comput. Inform. 2015, 34, 1017–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, J.Z.; Ghorbani, A.A. Improved competitive learning neural networks for network intrusion and fraud detection. Neurocomputing 2012, 75, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessmann, S.; Baesens, B.; Seow, H.V.; Thomas, L.C. Benchmarking state-of-the-art classification algorithms for credit scoring: An update of research. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 247, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Fang, T.; Hu, J.; Goh, C.C.; Zhang, H.; Cai, Y.; Bellotti, A.G.; Lee, B.G.; Ming, Z. A comprehensive study on the interplay between dataset characteristics and oversampling methods. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2025, 76, 1981–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Lin, Y.; Liu, Y. Improving interpolation-based oversampling for imbalanced data learning. Knowl. Based Syst. 2020, 187, 104826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touzani, Y.; Douzi, K. An LSTM and GRU based trading strategy adapted to the Moroccan market. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakkar, S.; B, S.; Reddy, L.S.; Pal, S.; Dimri, S.; Nishant, N. Analysis of Discovering Fraud in Master Card Based on Bidirectional GRU and CNN Based Model. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Self Sustainable Artificial Intelligence Systems (ICSSAS), Erode, India, 18–20 October 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.; Mustafa, G.; Rana, M.R.R.; Alshahrani, S.M.; Alymani, M. RNN-BiLSTM-CRF based amalgamated deep learning model for electricity theft detection to secure smart grids. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cohort | Number of Loans | Average Loan Length (Months) | Median Loan Length (Months) | Default Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009Q1 | 17,604 | 56.805 | 42 | 1.755% |

| 2009Q2 | 16,730 | 59.773 | 42 | 1.470% |

| 2009Q3 | 15,728 | 63.581 | 44 | 2.893% |

| 2009Q4 | 16,080 | 62.189 | 42 | 2.674% |

| 2010Q1 | 15,779 | 63.375 | 42 | 2.884% |

| 2010Q2 | 16,132 | 61.989 | 40 | 3.149% |

| 2010Q3 | 15,525 | 64.412 | 46 | 2.209% |

| 2010Q4 | 12,957 | 77.178 | 67 | 1.443% |

| 2011Q1 | 13,969 | 71.587 | 61 | 2.098% |

| 2011Q2 | 16,211 | 61.687 | 47 | 2.807% |

| 2011Q3 | 15,196 | 65.807 | 55 | 2.165% |

| 2011Q4 | 12,631 | 79.170 | 76 | 1.362% |

| 2012Q1 | 12,304 | 81.274 | 85 | 1.756% |

| 2012Q2 | 11,566 | 86.460 | 92 | 1.816% |

| 2012Q3 | 11,209 | 89.214 | 95 | 1.963% |

| 2012Q4 | 10,939 | 91.416 | 97 | 1.901% |

| 2013Q1 | 11,138 | 89.783 | 96 | 2.182% |

| 2013Q2 | 11,444 | 87.382 | 92 | 2.386% |

| 2013Q3 | 12,733 | 78.536 | 83 | 2.592% |

| 2013Q4 | 15,045 | 66.467 | 65 | 2.951% |

| 2014Q1 | 16,002 | 62.492 | 62 | 3.412% |

| 2014Q2 | 16,287 | 61.399 | 61 | 2.923% |

| 2014Q3 | 15,715 | 63.633 | 67 | 2.660% |

| 2014Q4 | 15,778 | 63.379 | 66 | 2.903% |

| 2015Q1 | 15,638 | 63.947 | 67 | 2.954% |

| 2015Q2 | 14,592 | 68.531 | 68 | 2.947% |

| 2015Q3 | 15,923 | 62.802 | 63 | 3.410% |

| 2015Q4 | 15,860 | 63.052 | 62 | 3.140% |

| 2016Q1 | 17,180 | 58.207 | 59 | 3.423% |

| 2016Q2 | 16,102 | 62.104 | 59 | 3.198% |

| 2016Q3 | 15,871 | 63.008 | 60 | 3.459% |

| 2016Q4 | 15,961 | 62.653 | 61 | 3.390% |

| 2017Q1 | 19,386 | 51.584 | 49 | 4.354% |

| 2017Q2 | 20,066 | 49.836 | 45 | 4.625% |

| 2017Q3 | 20,019 | 49.953 | 44 | 4.311% |

| 2017Q4 | 20,194 | 49.520 | 44 | 4.600% |

| 2018Q1 | 22,999 | 43.480 | 39 | 4.913% |

| 2018Q2 | 26,343 | 37.961 | 31 | 4.555% |

| 2018Q3 | 29,629 | 33.751 | 27 | 4.398% |

| 2018Q4 | 32,095 | 31.158 | 24 | 4.518% |

| 2019Q1 | 36,704 | 27.245 | 22 | 4.795% |

| 2019Q2 | 34,226 | 29.218 | 22 | 4.885% |

| 2019Q3 | 32,061 | 31.191 | 24 | 4.429% |

| 2019Q4 | 30,083 | 33.241 | 29 | 4.168% |

| No. | Feature | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Loan Sequence Number | Unique ID allocated for every loan. |

| 2 | Current Actual UPB | Indicates the reported final balance of the mortgage. |

| 3 | Current Loan Delinquency Status | Days overdue relative to the due date of the most recent payment made. |

| 4 | Defect Settlement Date | Date for resolution of Underwriting or Servicing Defects that are pending confirmation. |

| 5 | Modification Flag | Signifies that the loan has been altered. |

| 6 | Current Interest Rate (Current IR) | Displays the present interest rate on the mortgage note, with any modifications included. |

| 7 | Current Deferred UPB | The current non-interest bearing UPB of the modified loan. |

| 8 | Due Date Of Last Paid Installment (DDLPI) | Date until which the principal and interest on a loan are paid. |

| 9 | Estimated Loan To Value (ELTV) | LTV ratio using Freddie Mac’s AVM value. |

| 10 | Delinquency Due To Disaster | Indicator for hardship associated with disasters as reported by the Servicer. |

| 11 | Borrower Assistance Status Code | Type of support arrangement for interim loan payment mitigation. |

| 12 | Current Month Modification Cost | Monthly expense resulting from rate adjustment or UPB forbearance. |

| 13 | Interest Bearing UPB | The interest-bearing UPB of the adjusted loan. |

| Data Cohorts | RUS | SMOTE | TimeGAN | tSMOTE | ROS | No Resampling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009Q1 | 12.9 | 21.3 | 14.0 | 13.0 | 24.5 | 25.2 |

| 2009Q2 | 14.3 | 21.4 | 13.6 | 15.2 | 21.5 | 25.0 |

| 2009Q3 | 14.4 | 20.3 | 14.5 | 13.8 | 22.3 | 25.6 |

| 2009Q4 | 12.6 | 22.2 | 15.0 | 14.1 | 21.5 | 25.6 |

| 2010Q1 | 12.0 | 20.0 | 14.4 | 14.1 | 24.7 | 25.8 |

| 2010Q2 | 11.7 | 21.1 | 15.3 | 14.6 | 23.0 | 25.3 |

| 2010Q3 | 13.6 | 20.0 | 14.6 | 13.9 | 22.9 | 26.1 |

| 2010Q4 | 13.4 | 21.0 | 14.4 | 13.5 | 22.3 | 26.5 |

| 2011Q1 | 12.5 | 21.2 | 13.4 | 15.0 | 23.2 | 25.7 |

| 2011Q2 | 13.6 | 21.1 | 14.3 | 13.6 | 22.6 | 25.9 |

| 2011Q3 | 13.1 | 20.0 | 14.2 | 13.1 | 23.9 | 26.8 |

| 2011Q4 | 13.8 | 21.5 | 14.5 | 13.1 | 22.0 | 26.1 |

| 2012Q1 | 12.7 | 20.1 | 16.6 | 14.1 | 22.9 | 24.5 |

| 2012Q2 | 14.8 | 21.3 | 15.1 | 13.5 | 21.5 | 24.8 |

| 2012Q3 | 13.3 | 22.1 | 14.0 | 14.1 | 22.1 | 25.4 |

| 2012Q4 | 11.3 | 20.4 | 14.9 | 15.2 | 23.0 | 26.2 |

| 2013Q1 | 11.3 | 21.4 | 15.5 | 14.3 | 21.9 | 26.6 |

| 2013Q2 | 13.5 | 21.4 | 13.5 | 14.3 | 23.0 | 25.2 |

| 2013Q3 | 11.6 | 20.9 | 15.6 | 14.6 | 21.6 | 26.6 |

| 2013Q4 | 12.4 | 21.6 | 14.3 | 13.5 | 22.4 | 26.8 |

| 2014Q1 | 13.4 | 20.3 | 14.3 | 13.8 | 23.4 | 25.9 |

| 2014Q2 | 14.8 | 20.1 | 13.3 | 14.2 | 23.5 | 25.1 |

| 2014Q3 | 13.0 | 22.2 | 13.2 | 13.8 | 23.3 | 25.5 |

| 2014Q4 | 12.2 | 20.4 | 15.6 | 14.3 | 22.4 | 26.0 |

| 2015Q1 | 12.0 | 21.0 | 14.8 | 13.8 | 22.7 | 26.6 |

| 2015Q2 | 13.8 | 21.1 | 14.4 | 13.7 | 22.6 | 25.3 |

| 2015Q3 | 14.2 | 21.4 | 13.2 | 13.8 | 21.5 | 26.9 |

| 2015Q4 | 13.2 | 21.8 | 14.0 | 13.5 | 22.7 | 25.7 |

| 2016Q1 | 13.4 | 21.2 | 13.2 | 13.9 | 23.0 | 26.3 |

| 2016Q2 | 12.9 | 20.2 | 15.2 | 14.5 | 22.6 | 25.7 |

| 2016Q3 | 14.4 | 20.1 | 14.4 | 13.3 | 23.0 | 25.8 |

| 2016Q4 | 13.7 | 20.3 | 14.1 | 15.2 | 22.0 | 25.6 |

| 2017Q1 | 11.9 | 21.2 | 13.8 | 15.4 | 23.0 | 25.8 |

| 2017Q2 | 12.4 | 20.4 | 14.8 | 14.6 | 23.1 | 25.7 |

| 2017Q3 | 14.3 | 21.5 | 13.5 | 13.2 | 21.9 | 26.6 |

| 2017Q4 | 11.3 | 21.2 | 15.3 | 15.4 | 22.4 | 25.3 |

| 2018Q1 | 13.9 | 20.8 | 14.4 | 13.8 | 22.9 | 25.2 |

| 2018Q2 | 12.3 | 20.4 | 15.2 | 13.8 | 22.5 | 26.7 |

| 2018Q3 | 13.9 | 20.0 | 13.5 | 13.4 | 24.1 | 26.2 |

| 2018Q4 | 12.8 | 20.8 | 13.4 | 13.9 | 23.4 | 26.6 |

| 2019Q1 | 11.4 | 20.4 | 14.4 | 14.4 | 23.8 | 26.7 |

| 2019Q2 | 13.2 | 20.4 | 15.2 | 14.1 | 21.7 | 26.4 |

| 2019Q3 | 12.2 | 22.3 | 13.7 | 13.0 | 22.8 | 26.9 |

| 2019Q4 | 12.7 | 22.1 | 14.3 | 13.3 | 23.6 | 25.0 |

| Average | 13.0 | 21.0 | 14.3 | 14.0 | 22.8 | 25.9 |

| Data Cohorts | RUS | SMOTE | TimeGAN | tSMOTE | ROS | No Resampling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009Q1 | 8.1 | 19.9 | 12.9 | 13.6 | 25.2 | 31.3 |

| 2009Q2 | 10.6 | 18.6 | 14.2 | 13.7 | 23.7 | 30.1 |

| 2009Q3 | 6.8 | 19.7 | 12.8 | 12.5 | 26.3 | 32.8 |

| 2009Q4 | 10.0 | 18.8 | 14.2 | 14.1 | 24.1 | 29.8 |

| 2010Q1 | 6.6 | 19.7 | 12.4 | 12.4 | 26.8 | 33.1 |

| 2010Q2 | 8.5 | 19.1 | 13.4 | 13.4 | 25.1 | 31.4 |

| 2010Q3 | 9.9 | 18.8 | 13.9 | 14.3 | 24.2 | 29.8 |

| 2010Q4 | 10.1 | 18.5 | 13.7 | 13.8 | 24.1 | 30.9 |

| 2011Q1 | 10.5 | 19.1 | 14.3 | 14.1 | 23.8 | 29.2 |

| 2011Q2 | 9.2 | 19.4 | 13.7 | 13.7 | 24.4 | 30.7 |

| 2011Q3 | 11.3 | 18.7 | 14.9 | 14.5 | 22.9 | 28.7 |

| 2011Q4 | 10.5 | 19.6 | 14.3 | 13.7 | 23.8 | 29.2 |

| 2012Q1 | 11.2 | 19.1 | 14.5 | 14.7 | 22.9 | 28.5 |

| 2012Q2 | 11.1 | 19.0 | 14.7 | 14.3 | 23.2 | 28.7 |

| 2012Q3 | 10.4 | 18.9 | 14.7 | 14.6 | 23.5 | 28.8 |

| 2012Q4 | 8.4 | 19.6 | 13.1 | 12.9 | 25.3 | 31.8 |

| 2013Q1 | 10.8 | 19.4 | 14.7 | 14.6 | 23.4 | 28.1 |

| 2013Q2 | 10.5 | 18.7 | 14.3 | 14.0 | 24.0 | 29.6 |

| 2013Q3 | 11.5 | 19.1 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 23.4 | 28.4 |

| 2013Q4 | 10.3 | 18.8 | 14.2 | 14.6 | 23.9 | 29.2 |

| 2014Q1 | 10.0 | 19.3 | 13.9 | 13.9 | 23.9 | 29.9 |

| 2014Q2 | 9.8 | 19.2 | 13.4 | 14.0 | 24.7 | 29.9 |

| 2014Q3 | 7.3 | 19.1 | 13.2 | 13.0 | 25.6 | 32.7 |

| 2014Q4 | 10.5 | 19.0 | 14.1 | 14.2 | 23.7 | 29.6 |

| 2015Q1 | 11.1 | 19.0 | 14.2 | 14.4 | 23.5 | 28.7 |

| 2015Q2 | 11.4 | 18.5 | 12.5 | 12.3 | 24.8 | 31.5 |

| 2015Q3 | 9.8 | 18.8 | 14.1 | 14.3 | 24.2 | 29.8 |

| 2015Q4 | 10.1 | 19.3 | 14.1 | 14.5 | 24.0 | 29.1 |

| 2016Q1 | 10.3 | 18.8 | 14.6 | 14.3 | 23.9 | 29.0 |

| 2016Q2 | 9.5 | 19.0 | 13.7 | 13.4 | 24.4 | 31.1 |

| 2016Q3 | 9.9 | 19.0 | 14.2 | 14.3 | 23.9 | 29.7 |

| 2016Q4 | 9.4 | 18.4 | 14.3 | 13.5 | 24.3 | 31.0 |

| 2017Q1 | 9.1 | 19.3 | 13.7 | 14.0 | 24.4 | 30.5 |

| 2017Q2 | 10.4 | 18.8 | 14.3 | 14.4 | 23.8 | 29.4 |

| 2017Q3 | 12.8 | 19.4 | 12.3 | 12.1 | 24.3 | 30.1 |

| 2017Q4 | 9.3 | 19.1 | 14.3 | 14.0 | 23.9 | 30.4 |

| 2018Q1 | 7.7 | 19.6 | 13.3 | 13.6 | 25.2 | 31.6 |

| 2018Q2 | 8.9 | 19.2 | 13.8 | 13.2 | 25.2 | 30.7 |

| 2018Q3 | 11.6 | 19.7 | 11.3 | 12.8 | 25.1 | 30.5 |

| 2018Q4 | 9.4 | 18.7 | 13.9 | 13.4 | 25.0 | 30.5 |

| 2019Q1 | 8.8 | 19.3 | 13.3 | 12.7 | 25.2 | 31.7 |

| 2019Q2 | 9.5 | 19.5 | 13.2 | 12.2 | 25.3 | 31.4 |

| 2019Q3 | 9.1 | 19.0 | 13.6 | 13.9 | 24.8 | 30.6 |

| 2019Q4 | 10.6 | 19.4 | 14.2 | 14.6 | 23.8 | 28.4 |

| Average | 9.8 | 19.1 | 13.8 | 13.7 | 24.3 | 30.2 |

| Data Cohorts | Months | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 20 | 22 | 24 | |

| 2009Q1 | 19.7 | 11.8 | 15.2 | 16.5 | 27.5 | 28.7 | 31.1 |

| 2009Q2 | 22.6 | 8.4 | 13.0 | 18.2 | 24.9 | 27.6 | 35.8 |

| 2009Q3 | 20.3 | 13.2 | 12.9 | 12.4 | 24.4 | 30.2 | 37.1 |

| 2009Q4 | 18.1 | 10.6 | 13.5 | 15.7 | 25.5 | 27.2 | 39.9 |

| 2010Q1 | 19.5 | 7.6 | 14.2 | 14.8 | 27.8 | 27.8 | 38.8 |

| 2010Q2 | 18.7 | 11.9 | 14.4 | 14.5 | 24.5 | 27.3 | 39.2 |

| 2010Q3 | 17.5 | 11.6 | 13.3 | 13.4 | 25.7 | 29.6 | 39.4 |

| 2010Q4 | 18.9 | 14.9 | 13.2 | 17.4 | 24.6 | 27.2 | 34.3 |

| 2011Q1 | 20.8 | 10.8 | 8.7 | 13.4 | 28.2 | 29.5 | 39.1 |

| 2011Q2 | 17.3 | 11.8 | 12.3 | 17.0 | 27.1 | 30.6 | 34.4 |

| 2011Q3 | 21.5 | 9.4 | 13.9 | 13.8 | 28.2 | 27.8 | 35.9 |

| 2011Q4 | 21.2 | 8.7 | 12.8 | 12.6 | 27.7 | 28.0 | 39.5 |

| 2012Q1 | 20.5 | 10.7 | 13.3 | 12.8 | 23.9 | 28.0 | 41.3 |

| 2012Q2 | 21.0 | 10.6 | 11.5 | 18.4 | 25.8 | 28.4 | 34.8 |

| 2012Q3 | 17.8 | 14.3 | 15.7 | 13.6 | 22.8 | 30.6 | 35.7 |

| 2012Q4 | 21.8 | 9.2 | 12.8 | 15.0 | 26.5 | 29.7 | 35.5 |

| 2013Q1 | 17.5 | 11.8 | 12.5 | 15.9 | 28.2 | 27.8 | 36.8 |

| 2013Q2 | 19.4 | 9.2 | 8.4 | 18.0 | 27.6 | 27.4 | 40.5 |

| 2013Q3 | 21.6 | 10.5 | 15.2 | 18.3 | 24.6 | 24.1 | 36.2 |

| 2013Q4 | 21.6 | 11.9 | 14.4 | 9.2 | 24.7 | 27.1 | 41.6 |

| 2014Q1 | 18.8 | 8.3 | 15.4 | 16.5 | 27.9 | 29.5 | 34.1 |

| 2014Q2 | 17.2 | 11.4 | 11.4 | 18.6 | 27.7 | 29.9 | 34.3 |

| 2014Q3 | 19.2 | 10.7 | 14.9 | 17.8 | 26.1 | 29.9 | 31.9 |

| 2014Q4 | 21.3 | 12.6 | 12.1 | 14.4 | 25.3 | 27.7 | 37.1 |

| 2015Q1 | 19.2 | 12.8 | 7.7 | 18.9 | 24.2 | 30.6 | 37.1 |

| 2015Q2 | 19.3 | 8.7 | 15.6 | 17.6 | 24.5 | 31.6 | 33.2 |

| 2015Q3 | 18.3 | 9.5 | 11.7 | 17.9 | 26.8 | 27.8 | 38.5 |

| 2015Q4 | 20.9 | 10.9 | 15.1 | 12.0 | 24.7 | 27.5 | 39.4 |

| 2016Q1 | 21.8 | 10.6 | 7.7 | 16.2 | 24.3 | 30.9 | 39.0 |

| 2016Q2 | 17.7 | 12.7 | 8.2 | 16.5 | 27.2 | 30.0 | 38.2 |

| 2016Q3 | 19.0 | 8.7 | 14.6 | 15.1 | 25.6 | 28.0 | 39.5 |

| 2016Q4 | 20.3 | 9.3 | 12.6 | 17.6 | 26.5 | 28.9 | 35.3 |

| 2017Q1 | 18.7 | 12.5 | 13.7 | 12.4 | 24.3 | 30.4 | 38.5 |

| 2017Q2 | 18.7 | 11.3 | 13.7 | 12.8 | 25.7 | 31.3 | 37.0 |

| 2017Q3 | 19.9 | 12.4 | 13.7 | 17.9 | 28.4 | 29.8 | 28.4 |

| 2017Q4 | 17.7 | 12.1 | 9.5 | 13.7 | 25.3 | 29.2 | 43.0 |

| 2018Q1 | 17.3 | 11.6 | 13.5 | 14.2 | 27.6 | 29.0 | 37.3 |

| 2018Q2 | 20.1 | 9.0 | 11.5 | 15.3 | 26.1 | 28.2 | 40.3 |

| 2018Q3 | 20.2 | 12.2 | 14.6 | 18.2 | 27.2 | 31.7 | 26.4 |

| 2018Q4 | 19.9 | 11.5 | 14.4 | 14.5 | 24.4 | 27.4 | 38.4 |

| 2019Q1 | 20.7 | 10.7 | 15.2 | 12.1 | 25.8 | 27.3 | 38.7 |

| 2019Q2 | 20.4 | 11.9 | 11.4 | 15.9 | 27.6 | 27.1 | 36.2 |

| 2019Q3 | 18.7 | 7.6 | 12.4 | 18.0 | 27.1 | 29.8 | 36.9 |

| 2019Q4 | 19.3 | 12.7 | 13.4 | 13.7 | 26.4 | 28.7 | 36.3 |

| Average | 19.6 | 10.9 | 12.8 | 15.4 | 26.1 | 28.8 | 36.9 |

| Quarter | LSTM | BiLSTM | GRU | CNN | RNN | ResE-BiLSTM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009Q1 | 2.2 | 4.8 | 3.4 | 5.4 | 4.2 | 1 |

| 2009Q2 | 3 | 5.2 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 5.4 | 1 |

| 2009Q3 | 4.8 | 4 | 3.8 | 5.2 | 2.2 | 1 |

| 2009Q4 | 3.4 | 4.2 | 1 | 5.6 | 2 | 4.8 |

| 2010Q1 | 2.8 | 4.8 | 4.2 | 5.6 | 2.6 | 1 |

| 2010Q2 | 3.2 | 4 | 2.6 | 6 | 4.2 | 1 |

| 2010Q3 | 4 | 2.2 | 3.6 | 5.8 | 4.4 | 1 |

| 2010Q4 | 3.4 | 2.6 | 4.8 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 5.4 |

| 2011Q1 | 3.4 | 1.6 | 3 | 5.4 | 3.6 | 4 |

| 2011Q2 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 4 | 6 | 3.4 | 1 |

| 2011Q3 | 3.4 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 5.2 | 4.2 | 4.8 |

| 2011Q4 | 2.8 | 3.8 | 4.8 | 5.2 | 2.6 | 1.6 |

| 2012Q1 | 3 | 4 | 2.4 | 6 | 1.8 | 3.8 |

| 2012Q2 | 4 | 6 | 4.6 | 3.4 | 2 | 1 |

| 2012Q3 | 3 | 3.6 | 3 | 5.8 | 4.6 | 1 |

| 2012Q4 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 6 | 4.2 | 1 |

| 2013Q1 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 5 | 5.4 | 1 |

| 2013Q2 | 3.4 | 2.2 | 3.8 | 5.8 | 4.2 | 1.6 |

| 2013Q3 | 3 | 3.6 | 2.4 | 6 | 4.2 | 1.8 |

| 2013Q4 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 4.8 | 6 | 2.2 | 1.2 |

| 2014Q1 | 3.8 | 4.4 | 3.2 | 6 | 2.6 | 1 |

| 2014Q2 | 3 | 3.8 | 5 | 5.4 | 2.6 | 1.2 |

| 2014Q3 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 5.2 | 5.6 | 3.8 | 1.4 |

| 2014Q4 | 3.2 | 4 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 3.2 | 1 |

| 2015Q1 | 3.4 | 4.4 | 5 | 4.6 | 2.4 | 1.2 |

| 2015Q2 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 4.4 | 5.6 | 5 | 1 |

| 2015Q3 | 3 | 2 | 3.8 | 6 | 5 | 1.2 |

| 2015Q4 | 4 | 1.4 | 3 | 6 | 3.8 | 2.8 |

| 2016Q1 | 4.6 | 2.6 | 3.8 | 6 | 2.8 | 1.2 |

| 2016Q2 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 2.8 | 6 | 2 | 2.4 |

| 2016Q3 | 2.4 | 4.4 | 2.2 | 6 | 3.8 | 2.2 |

| 2016Q4 | 4 | 4.6 | 2.8 | 6 | 2.4 | 1.2 |

| 2017Q1 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 4.6 | 6 | 2.4 | 1 |

| 2017Q2 | 3 | 3.2 | 4 | 5.2 | 4.6 | 1 |

| 2017Q3 | 3 | 2.4 | 4.4 | 6 | 4.2 | 1 |

| 2017Q4 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 4 | 6 | 4.2 | 1 |

| 2018Q1 | 2.4 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 6 | 3.6 | 1.8 |

| 2018Q2 | 2.4 | 3.4 | 4 | 6 | 4.2 | 1 |

| 2018Q3 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 6 | 2.2 | 1.6 |

| 2018Q4 | 4 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 6 | 2.6 | 1 |

| 2019Q1 | 3 | 4.2 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 1.8 |

| 2019Q2 | 3.2 | 3.8 | 4.8 | 5.2 | 3 | 1 |

| 2019Q3 | 3.6 | 2.4 | 4.2 | 6 | 3 | 1.8 |

| 2019Q4 | 3 | 4.4 | 3.8 | 6 | 2.8 | 1 |

| Year | LSTM | BiLSTM | GRU | CNN | RNN | ResE-BiLSTM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 12.10 | 14.10 | 11.65 | 17.30 | 12.40 | 7.45 |

| 2010 | 12.15 | 11.80 | 12.70 | 15.70 | 12.35 | 10.30 |

| 2011 | 10.75 | 9.55 | 10.55 | 20.20 | 12.25 | 11.65 |

| 2012 | 12.50 | 12.80 | 12.10 | 16.45 | 11.80 | 9.35 |

| 2013 | 12.15 | 11.40 | 11.80 | 19.40 | 13.20 | 7.05 |

| 2014 | 11.85 | 12.40 | 13.95 | 18.55 | 11.40 | 6.85 |

| 2015 | 11.30 | 9.95 | 12.75 | 20.65 | 12.90 | 7.45 |

| 2016 | 12.60 | 12.70 | 10.70 | 20.25 | 10.65 | 8.05 |

| 2017 | 11.05 | 10.75 | 13.70 | 21.75 | 12.60 | 5.15 |

| 2018 | 11.45 | 11.80 | 12.20 | 21.60 | 11.60 | 6.35 |

| 2019 | 11.10 | 12.45 | 12.80 | 20.85 | 10.15 | 7.65 |

| Data Cohort | p-Value for F1 | p-Value for AUC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | BiLSTM | LSTM | BiLSTM | |

| 2009Q1 | 4.12 | 2.68 | 2.28 | 5.87 |

| 2009Q2 | ||||

| 2009Q3 | 1.98 | 1.14 | ||

| 2009Q4 | 7.40 | 3.21 | 6.25 | 4.85 |

| 2010Q1 | 1.33 | 2.88 | ||

| 2010Q2 | 9.33 | |||

| 2010Q3 | 2.28 | 3.60 | 2.28 | |

| 2010Q4 | 5.12 | 6.18 | 7.40 | 8.32 |

| 2011Q1 | 6.25 | 3.60 | 9.83 | 5.20 |

| 2011Q2 | ||||

| 2011Q3 | 3.60 | 3.28 | 2.28 | 3.60 |

| 2011Q4 | ||||

| 2012Q1 | 4.85 | 6.25 | 4.12 | 3.60 |

| 2012Q2 | ||||

| 2012Q3 | 1.01 | |||

| 2012Q4 | 7.24 | |||

| 2013Q1 | ||||

| 2013Q2 | 8.21 | 3.60 | 4.85 | |

| 2013Q3 | 4.91 | 2.28 | ||

| 2013Q4 | ||||

| 2014Q1 | 3.60 | 1.01 | ||

| 2014Q2 | 5.47 | 6.41 | ||

| 2014Q3 | 2.24 | 1.51 | 2.17 | 1.83 |

| 2014Q4 | 7.36 | 5.57 | ||

| 2015Q1 | ||||

| 2015Q2 | 2.38 | 1.64 | ||

| 2015Q3 | 8.91 | 1.28 | 1.09 | |

| 2015Q4 | 1.06 | 7.53 | 6.76 | |

| 2016Q1 | 2.28 | 6.25 | 1.01 | |

| 2016Q2 | 1.01 | 4.61 | ||

| 2016Q3 | 3.22 | 3.59 | 1.95 | |

| 2016Q4 | ||||

| 2017Q1 | 9.71 | |||

| 2017Q2 | 1.86 | 1.52 | ||

| 2017Q3 | 3.41 | 7.13 | ||

| 2017Q4 | ||||

| 2018Q1 | 5.20 | 6.80 | 4.91 | 6.39 |

| 2018Q2 | 2.12 | |||

| 2018Q3 | ||||

| 2018Q4 | ||||

| 2019Q1 | 2.85 | 2.23 | 1.58 | |

| 2019Q2 | 1.12 | 9.77 | ||

| 2019Q3 | ||||

| 2019Q4 | 2.08 | |||

| Cohort | Metrics | ResE-BiLSTM | E-BiLSTM (M1) | A-BiLSTM (M2) | BiLSTM (M3) | LSTM (M4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009; 2010; 2011 | Accuracy | 0.9283 | 0.9151 | 0.7514 | 0.9121 | 0.9040 |

| Precision | 0.9614 | 0.9493 | 0.9451 | 0.9467 | 0.9534 | |

| Recall | 0.8917 | 0.8670 | 0.5347 | 0.8734 | 0.8497 | |

| F1 | 0.9252 | 0.9063 | 0.6812 | 0.9085 | 0.8984 | |

| AUC | 0.9709 | 0.9618 | 0.8702 | 0.9614 | 0.9594 | |

| 2012; 2013; 2014 | Accuracy | 0.9311 | 0.9184 | 0.7460 | 0.9086 | 0.9079 |

| Precision | 0.9317 | 0.9191 | 0.7421 | 0.8930 | 0.8957 | |

| Recall | 0.9404 | 0.9267 | 0.7750 | 0.9286 | 0.9234 | |

| F1 | 0.9360 | 0.9229 | 0.7535 | 0.9104 | 0.9093 | |

| AUC | 0.9724 | 0.9612 | 0.8475 | 0.9577 | 0.9556 | |

| 2015; 2016; 2017 | Accuracy | 0.9203 | 0.9050 | 0.7047 | 0.8933 | 0.8882 |

| Precision | 0.8945 | 0.8843 | 0.6839 | 0.8811 | 0.8696 | |

| Recall | 0.9312 | 0.9184 | 0.7763 | 0.9094 | 0.9132 | |

| F1 | 0.9125 | 0.9010 | 0.7241 | 0.8950 | 0.8909 | |

| AUC | 0.9678 | 0.9572 | 0.8101 | 0.9561 | 0.9549 | |

| 2018; 2019; 2020 | Accuracy | 0.9331 | 0.9196 | 0.7950 | 0.9154 | 0.9120 |

| Precision | 0.9791 | 0.9687 | 0.9599 | 0.9579 | 0.9579 | |

| Recall | 0.8671 | 0.8496 | 0.6967 | 0.8325 | 0.8257 | |

| F1 | 0.9197 | 0.9052 | 0.8074 | 0.8908 | 0.8869 | |

| AUC | 0.9736 | 0.9619 | 0.9059 | 0.9593 | 0.9599 |

| Feature | ResE-BiLSTM | BiLSTM | LSTM | GRU | RNN | CNN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interest Bearing UPB-Delta | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| Current Actual UPB-Delta | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| Estimated Loan to Value (ELTV) | 12 | 11 | 14 | 14 | 11 | 14 |

| Borrower Assistance Status Code_F | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | - |

| Delinquency Due To Disaster_Y | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | - |

| Current Deferred UPB | 3 | 3 | - | 3 | 4 | 8 |

| Delinquency Due To Disaster_NAN | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | - |

| Borrower Assistance Status Code_NAN | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Current Interest Rate | - | - | 1 | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Su, Z.; Goh, C.C.; Fang, T.; Bellotti, A.; Lee, B.G. Transforming Credit Risk Analysis: A Time-Series-Driven ResE-BiLSTM Framework for Post-Loan Default Detection. Information 2026, 17, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010005

Yang Y, Lin Y, Zhang Y, Su Z, Goh CC, Fang T, Bellotti A, Lee BG. Transforming Credit Risk Analysis: A Time-Series-Driven ResE-BiLSTM Framework for Post-Loan Default Detection. Information. 2026; 17(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yue, Yuxiang Lin, Ying Zhang, Zihan Su, Chang Chuan Goh, Tangtangfang Fang, Anthony Bellotti, and Boon Giin Lee. 2026. "Transforming Credit Risk Analysis: A Time-Series-Driven ResE-BiLSTM Framework for Post-Loan Default Detection" Information 17, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010005

APA StyleYang, Y., Lin, Y., Zhang, Y., Su, Z., Goh, C. C., Fang, T., Bellotti, A., & Lee, B. G. (2026). Transforming Credit Risk Analysis: A Time-Series-Driven ResE-BiLSTM Framework for Post-Loan Default Detection. Information, 17(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010005