Interest as the Engine: Leveraging Diverse Hybrid Propagation for Influence Maximization in Interest-Based Social Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How to define an information propagation model within ISNs. This model must be capable of modeling not only the information propagation between users but also the platform’s interest-based information delivery to users.

- How to design an Influence Maximization algorithm suitable for ISNs. This algorithm needs to select a set of highly influential nodes in the Interest-driven Social Network while also mitigating the influence overlap problem as much as possible.

- We first define the SIHIM problem, considering influence propagation under both “node–node” and “Server–node” mechanisms. We prove that its objective function is monotonic and submodular and that influence estimation for this problem is NP-hard.

- We design a propagation model named Server-Based Independent Cascade (SB-IC), which fully considers the impact of users’ interest characteristics on influence propagation. This enables more accurate modeling of the information propagation process in ISNs.

- We propose a new IM algorithm called PaC. This method fully considers the multi-attribute characteristics of nodes, thereby accurately identifying influential nodes in the network while effectively avoiding the problem of influence overlap between nodes.

- We conducted extensive experiments on ten real-world datasets, comparing our proposed algorithm with several recent high-performance algorithms. The results demonstrate that our algorithm achieved an average improvement in influence spreading by 5.22% and 7.04% on the IC model and SB-IC model, respectively, compared to the other nine comparison algorithms.

2. Related Work

2.1. Greedy-Based Methods

2.2. Heuristic-Based Methods

2.3. Influence Maximization with Users’ Interests

3. Model and Problem Definition

3.1. Interest-Driven Social Network and Diffusion Model

- Information propagation based on social relationships: Each node u activated at time step will attempt to activate its inactive neighbor node v with probability .

- Information propagation based on node interests: The Servers will attempt to activate each inactive interest neighbor node w of node u that was activated at time step with probability .

3.2. Problem Definition

- (1)

- Monotonicity of the SIHIM problem

- (2)

- Sub-modularity of SIHIM problem

4. Proposed Method

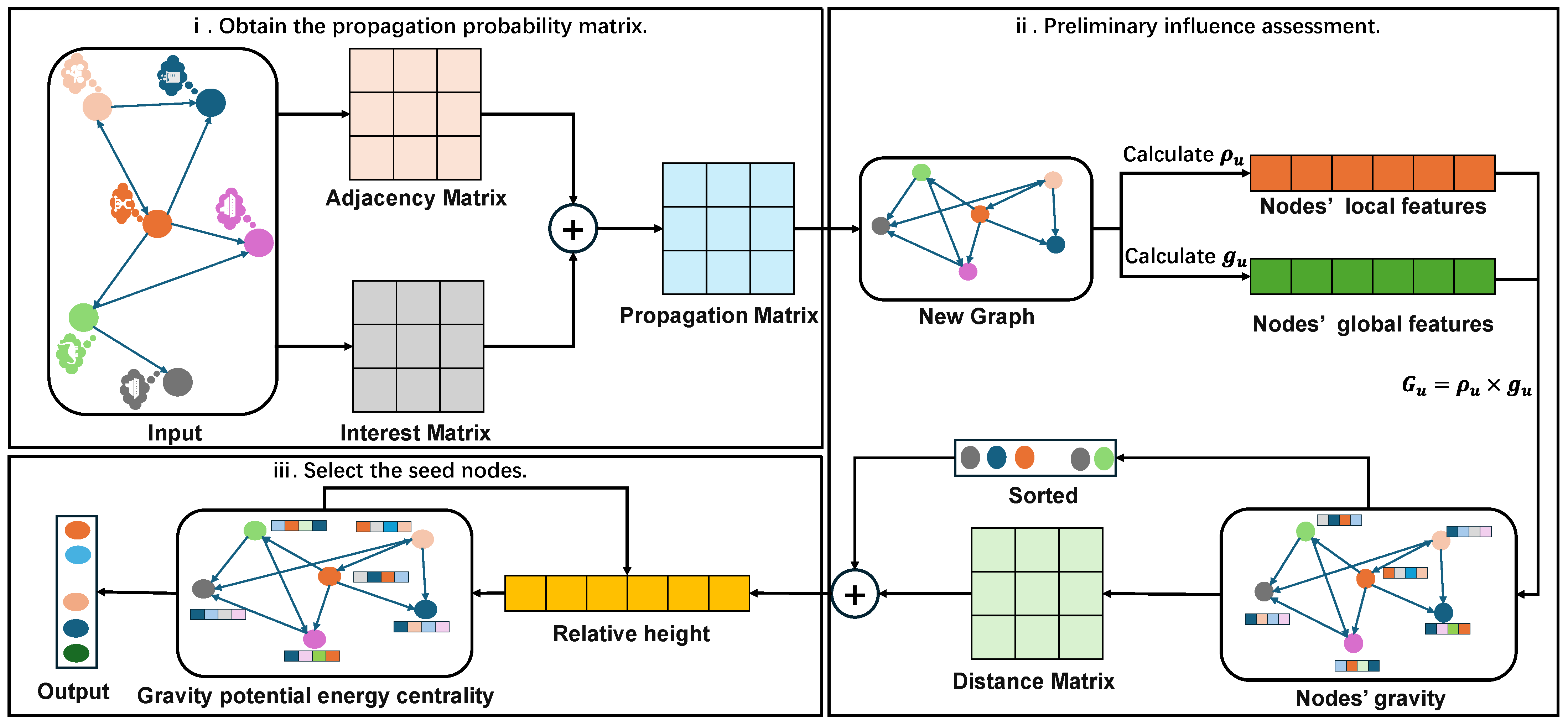

4.1. The Framework of Pascal Centrality

- Obtain the propagation matrix: The algorithm first constructs a Pascal centrality propagation matrix based on the initial propagation probabilities between nodes.

- Assess the initial influence: The algorithm then calculates the density and gravitational acceleration of each node to perform a preliminary assessment of the node’s influence.

- Select seed nodes: After completing the preliminary assessment, the algorithm iteratively updates the relative height of each node and finally outputs the node sequence based on the size of the PaC value.

4.2. Propagation Matrix

4.3. Assess the Initial Influence

4.4. Seed Node Selection

| Algorithm 1 Pascal Centrality. |

|

4.5. Complexity Analysis of the PaC Algorithm

5. Performance Analysis

5.1. Datasets and Compared Algorithms

- dolphins: The social network of 62 bottlenose dolphins in New Zealand was constructed based on their frequent interaction patterns.

- dublin: This network records the contact network of an influenza outbreak at a school in Dublin.

- crime-moreno: This network is constructed based on the relationships between criminal cases and suspects, victims, witnesses, and other parties involved.

- Hamsterster: This represents a social network dataset containing anonymized friendships and family relationships among users, sourced from real-world interactions.

- Citeseer: This network is composed of citation relationships among 3312 publications across six categories.

- Politician: This includes mutual-follow data between blue-badge-certified pages crawled from Facebook.

- US-Grid: This is an undirected graph constructed using information about power grids in western US states.

- pgp: This dataset records the interaction and relationship network among users of the Pretty Good Privacy algorithm.

- indochina-2004: A large-scale web-crawling dataset covering webpage data from domain names in Indochina countries.

- Sinanet: This network is constructed based on the follower/followee relationships between microblog users extracted from Sina Weibo, along with their interests characterized by topic distributions in 10 forums.

| Network | k | c | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dolphins | 62 | 159 | 12 | 5.129 | 4 | 0.259 |

| dublin | 410 | 2765 | 50 | 13.488 | 17 | 0.456 |

| crime-moreno | 829 | 1473 | 25 | 3.554 | 3 | 0.006 |

| hamsterster | 2426 | 16,630 | 273 | 13.710 | 24 | 0.538 |

| citeseer | 3264 | 4536 | 99 | 2.779 | 7 | 0.145 |

| politician | 5908 | 41,706 | 323 | 14.119 | 31 | 0.385 |

| US-Grid | 4941 | 6594 | 19 | 2.669 | 5 | 0.080 |

| pgp | 10,682 | 24,317 | 205 | 4.553 | 31 | 0.266 |

| indochina-2004 | 11,358 | 47,606 | 199 | 8.383 | 49 | 0.710 |

| Sinanet | 3490 | 28,657 | 799 | 16.5313 | 20 | 0.179 |

- DC (1994): DC evaluates the importance of a node based on its degree, i.e., the number of edges connected to the node. Nodes with higher degrees are deemed more influential in the network, as they can directly influence more other nodes.

- K-Shell (2010): K-Shell assesses a node’s robustness and connectivity by iteratively removing nodes with degrees below a certain threshold. The higher a node’s K-Shell value, the more influential it is within the network.

- LGC (2021): LGC identifies critical nodes in complex networks by integrating both local and global topological information, effectively overcoming the limitations of focusing solely on local structure or global information.

- GGC (2021): GGC measures a node’s propagation capability by combining its local clustering coefficient and degree. This approach is more comprehensive than traditional gravity models and enables more accurate identification of influential nodes in complex networks.

- LSS (2023): LSS is a novel heuristic algorithm that evaluates a node’s influence by combining degree centrality, K-Shell values, and node connectivity. It features low computational complexity and requires no parameter tuning.

- NPIC (2024): NPIC assesses a node’s influence by integrating local attributes and global path information, providing a comprehensive method for evaluating node importance.

- EPC (2024): EPC is a complex-network key-node identification method based on potential centrality. It comprehensively considers both local and global topological information and measures the influence of nodes based on their degree and distance.

- RCNN (2020): RCNN is a complex network key node identification method based on graph convolutional networks. It converts the critical node identification problem into a regression problem, utilizes adjacency matrices and convolutional neural networks to learn and predict node influence.

- ToupleGDD (2024): ToupleGDD is an influence maximization method based on deep reinforcement learning. It incorporates three coupled graph neural networks and double deep Q-networks, uses personalized DeepWalk for node embedding, and optimizes seed selection policies through reinforcement learning.

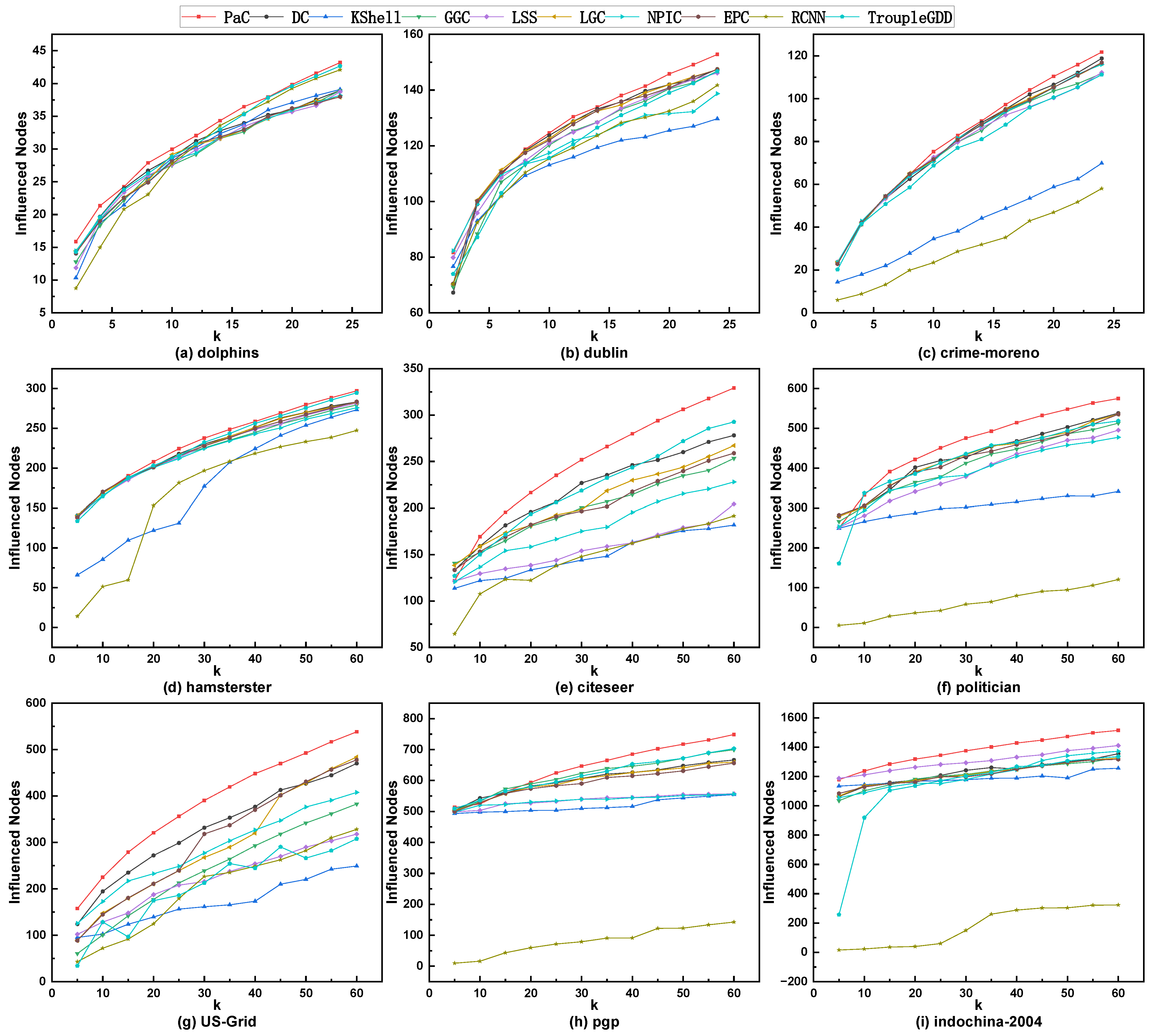

5.2. The Comparison of Influence Spreading

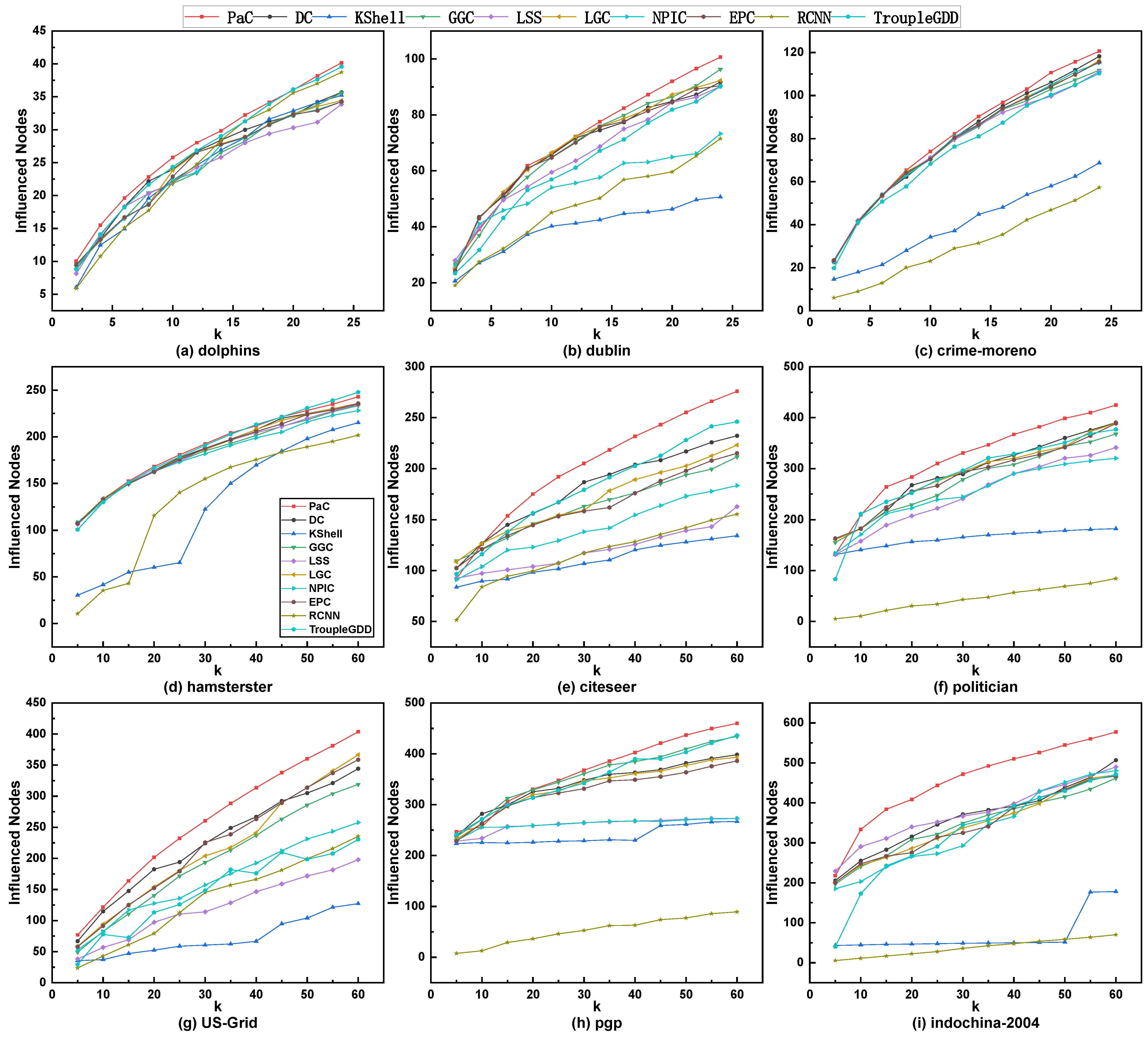

5.3. The Comparison of Influence Propagation Rate

5.4. The Comparison of Coverage Redundancy

5.5. Ablation Experiment

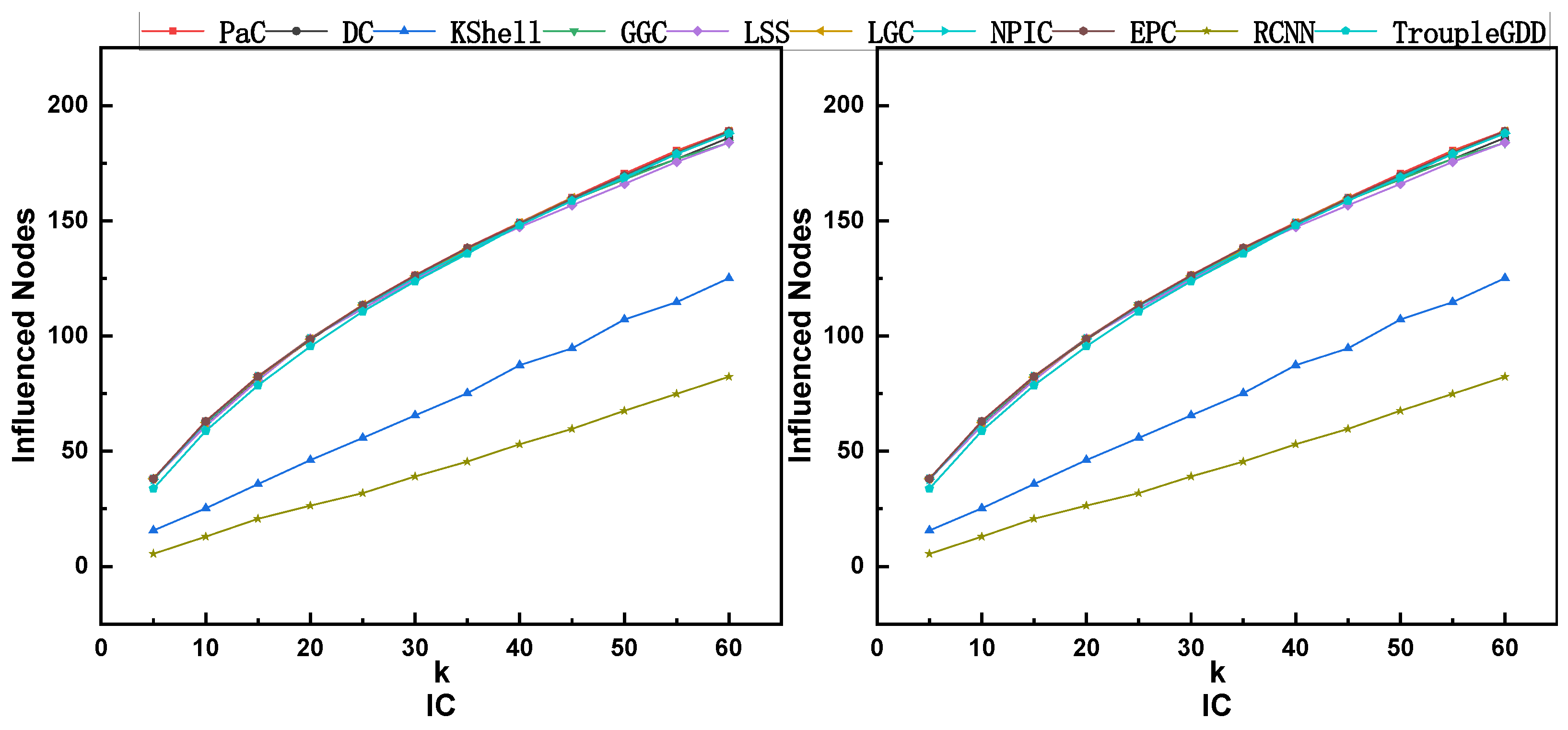

5.6. The Comparison of Influence Spreading on ISNs

5.7. Statistical Comparison of PaC and DC Performance

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IM | Influence Maximization |

| IC | Independent Cascade |

| LT | Linear Threshold |

| TIM | Topic-aware Influence Maximization |

| ISN | Interest-Based Social Network |

| SIHIM | Social–Interest Hybrid Influence Maximization Problem |

| SB-IC | Server-Based Independent Cascad |

| PaC | Pascal Centrality |

| DC | Degree Centrality |

| HIM | Holistic Influence Maximization |

| OI | Opinion-cum-Interaction |

| TFIP | Two-Factor Information Propagation |

| PIED | Potential Interest Expansion Degree |

References

- Yanchenko, E.; Murata, T.; Holme, P. Influence maximization on temporal networks: A review. Appl. Netw. Sci. 2024, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Li, W.; Liu, F.; Zhong, K.; Wu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Jin, Q. Influence maximization algorithm based on group trust and local topology structure. Neurocomputing 2024, 564, 126936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaouadi, M.; Romdhane, L.B. A survey on influence maximization models. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 248, 123429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Domingos, P. Mining knowledge-sharing sites for viral marketing. In Proceedings of the Eighth ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 23–26 July 2002; pp. 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempe, D.; Kleinberg, J.; Tardos, É. Maximizing the spread of influence through a social network. In Proceedings of the Ninth ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Washington, DC, USA, 24–27 August 2003; pp. 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. Threshold models of collective behavior. Am. J. Sociol. 1978, 83, 1420–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-De-León, C. On the global stability of SIS, SIR and SIRS epidemic models with standard incidence. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2011, 44, 1106–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leskovec, J.; Krause, A.; Guestrin, C.; Faloutsos, C.; VanBriesen, J.; Glance, N. Cost-effective outbreak detection in networks. In Proceedings of the 13th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Jose, CA, USA, 12–15 August 2007; pp. 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, A.; Lu, W.; Lakshmanan, L.V. Celf++ optimizing the greedy algorithm for influence maximization in social networks. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference Companion on World Wide Web, Hyderabad, India, 28 March–1 April 2011; pp. 47–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S. Efficient influence maximization in social networks. In Proceedings of the 15th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Paris, France, 28 June–1 July 2009; pp. 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Shen, H.; Huang, J.; Zhang, G.; Cheng, X. Staticgreedy: Solving the scalability-accuracy dilemma in influence maximization. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, San Francisco, CA, USA, 27 October–1 November 2013; pp. 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, P.; Zang, W.; Guo, L. On the upper bounds of spread for greedy algorithms in social network influence maximization. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2015, 27, 2770–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, T.K.; Abbasi, A.; Chakrabortty, R.K. A two-stage VIKOR assisted multi-operator differential evolution approach for Influence Maximization in social networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 192, 116342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, Z.; Rui, X.; Chai, Y.; Yu, P.S.; Sun, L. Triadic closure sensitive influence maximization. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 2023, 17, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhu, L. Turing instability analysis of a reaction–diffusion system for rumor propagation in continuous space and complex networks. Inf. Process. Manag. 2024, 61, 103621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.C.; Roeder, D.; Mulholland, R.R. Centrality in social networks: II. Experimental results. Soc. Netw. 1979, 2, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garas, A.; Schweitzer, F.; Havlin, S. A k-shell decomposition method for weighted networks. New J. Phys. 2012, 14, 083030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Din, S.U.; Khan, N.; Mawuli, C.B.; Shao, J. Towards investigating influencers in complex social networks using electric potential concept from a centrality perspective. Inf. Fusion 2024, 109, 102439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.C. A set of measures of centrality based on betweenness. Sociometry 1977, 40, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.C. Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Soc. Netw. 1978, 1, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Cheong, K.H. Node influence ranking in complex networks: A local structure entropy approach. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 160, 112136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agneessens, F.; Borgatti, S.P.; Everett, M.G. Geodesic based centrality: Unifying the local and the global. Soc. Netw. 2017, 49, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Shang, Q.; Deng, Y. A generalized gravity model for influential spreaders identification in complex networks. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 143, 110456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Sheng, J.; Wang, B.; Din, S.U.; Khan, N. Leveraging neighborhood and path information for influential spreaders recognition in complex networks. J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 2024, 62, 377–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibnoulouafi, A.; El Haziti, M.; Cherifi, H. M-centrality: Identifying key nodes based on global position and local degree variation. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2018, 2018, 073407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Wang, B.; Sheng, J.; Long, J.; Khan, N.; Sun, Z. Identifying vital nodes from local and global perspectives in complex networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 186, 115778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Shao, J.; Yang, Q.; Khan, N.; Bernard, C.M.; Kumar, R. LSS: A locality-based structure system to evaluate the spreader’s importance in social complex networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 228, 120326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Jiang, J.; Xu, H.; Kassim, M. IMNE: Maximizing influence through deep learning-based node embedding in social network. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2024, 88, 101609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.Y.; Wang, Y.P.; Fu, Y.; Chen, D.B.; Xie, M. Identifying critical nodes in complex networks via graph convolutional networks. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 198, 105893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, C.; Jiang, J.; Wang, J.; Thai, M.T.; Xue, R.; Song, J.; Qiu, M.; Zhao, L. Deep graph representation learning and optimization for influence maximization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 21350–21361. Available online: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v202/ling23b.html (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Zhong, Y.; Wang, S.; Liang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Su, C. ReCovNet: Reinforcement learning with covering information for solving maximal coverage billboards location problem. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 128, 103710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Yan, S.; Guo, J.; Wu, W. ToupleGDD: A fine-designed solution of influence maximization by deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2023, 11, 2210–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Du, H.; Li, X. Topic-aware information coverage maximization in social networks. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2023, 11, 1722–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslay, C.; Barbieri, N.; Bonchi, F.; Baeza-Yates, R. Online Topic-aware Influence Maximization Queries. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Extending Database Technology, EDBT, Athens, Greece, 24–28 March 2014; pp. 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Fan, J.; Li, G.; Feng, J.; Tan, K.l.; Tang, J. Online topic-aware influence maximization. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2015, 8, 666–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingöl, K.; Eravcı, B.; Etemoğlu, Ç.Ö.; Ferhatosmanoğlu, H.; Gedik, B. Topic-based influence computation in social networks under resource constraints. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2016, 12, 970–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Zhong, C.; Yang, Q. An influence maximization algorithm based on community-topic features for dynamic social networks. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 608–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galhotra, S.; Arora, A.; Roy, S. Holistic influence maximization: Combining scalability and efficiency with opinion-aware models. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Management of Data, San Francisco, CA, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016; pp. 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Li, J.; Mian, A.; Li, R.H.; Sellis, T.; Yu, J.X. Target-aware holistic influence maximization in spatial social networks. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2020, 34, 1993–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, C. An influence maximization method based on crowd emotion under an emotion-based attribute social network. Inf. Process. Manag. 2022, 59, 102818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Lan, B.; Nong, J.; Pang, G.; Hao, F. SentiRank: A Novel Approach to Sentiment Leader Identification in Social Networks Based on the D-TFRank Model. Electronics 2025, 14, 2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareie, A.; Sheikhahmadi, A.; Jalili, M. Identification of influential users in social networks based on users’ interest. Inf. Sci. 2019, 493, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Guo, P.; Guo, J. GraphHash: Topic-Aware Influence Maximization Using Hash. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), Washington, DC, USA, 15–18 December 2024; pp. 7183–7192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halal, T.; Cautis, B.; Groz, B.; Gao, R. Topic-aware influence maximization with deep reinforcement learning and graph attention networks. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2025, 39, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadikia, M.H.; Roayaei, M. Dynamic Adaptive Parametric Social Network Analysis Using Reinforcement Learning: A Case Study in Topic-Aware Influence Maximization. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 129372–129384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, C.Y.; Chen, J.J.; Liao, S.G. DyHGTCR-Cas: Learning unified spatio-temporal features based on dynamic heterogeneous graph neural network for information cascade prediction. Inf. Process. Manag. 2025, 62, 104029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Mukherjee, N. Topic and opinion infused hypergraphs for influence maximization. Phys. Lett. A 2025, 545, 130507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vombatkere, K.; Mousavi, S.; Zannettou, S.; Roesner, F.; Gummadi, K.P. Tiktok and the art of personalization: Investigating exploration and exploitation on social media feeds. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2024, Singapore, 13–17 May 2024; pp. 3789–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, L. A new status index derived from sociometric analysis. Psychometrika 1953, 18, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zhao, X.; Ge, B.; Xiao, W.; Ruan, Y. An efficient algorithm for mining a set of influential spreaders in complex networks. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2019, 516, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Li, Y.; Carson, M.B.; Wang, X.; Yu, J. Node attribute-enhanced community detection in complex networks. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, R.; Ahmed, N. The network data repository with interactive graph analytics and visualization. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2015, 29, 4292–4293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Hou, L.; Liu, K. The effect of product distance on the eWOM in recommendation network. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 22, 901–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, A.; Dospinescu, N.; Dospinescu, O. Beyond credibility: Understanding the mediators between electronic word-of-mouth and purchase intention. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.05359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | k | Algorithms | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PaC | DC | KShell | GGC | LSS | LGC | NPIC | EPC | ||

| dolphins | 2 | 5.500 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 5.000 |

| 4 | 4.500 | 3.375 | 3.375 | 3.375 | 3.875 | 3.250 | 3.250 | 3.250 | |

| 6 | 3.944 | 3.389 | 2.722 | 2.778 | 3.222 | 2.889 | 2.889 | 2.889 | |

| 8 | 3.563 | 3.313 | 2.906 | 2.719 | 2.750 | 2.594 | 2.594 | 2.594 | |

| 10 | 3.340 | 3.060 | 2.860 | 2.480 | 2.60 | 2.90 | 2.640 | 2.820 | |

| 12 | 3.181 | 3.125 | 2.708 | 2.403 | 2.556 | 2.958 | 2.444 | 2.958 | |

| 14 | 3.265 | 3.031 | 2.745 | 2.551 | 2.500 | 2.745 | 2.745 | 2.745 | |

| 16 | 3.352 | 2.906 | 2.703 | 2.484 | 2.508 | 2.633 | 2.633 | 2.633 | |

| 18 | 3.556 | 2.975 | 2.846 | 2.630 | 2.463 | 2.759 | 2.759 | 2.759 | |

| 20 | 3.625 | 2.905 | 2.890 | 2.605 | 2.375 | 2.745 | 2.745 | 2.745 | |

| 22 | 3.868 | 2.872 | 2.851 | 2.574 | 2.322 | 2.694 | 2.686 | 2.686 | |

| 24 | 3.931 | 2.816 | 2.792 | 2.611 | 2.417 | 2.656 | 2.656 | 2.656 | |

| dublin | 2 | 5.500 | 6.000 | 5.500 | 6.000 | 6.000 | 6.000 | 5.500 | 6.000 |

| 4 | 3.875 | 3.875 | 3.500 | 3.500 | 3.625 | 3.875 | 3.625 | 3.875 | |

| 6 | 3.111 | 3.111 | 2.778 | 3.000 | 3.167 | 3.167 | 2.944 | 3.111 | |

| 8 | 3.094 | 2.875 | 2.375 | 2.719 | 2.750 | 2.875 | 2.563 | 2.875 | |

| 10 | 2.920 | 2.760 | 2.100 | 2.680 | 2.500 | 2.640 | 2.360 | 2.620 | |

| 12 | 3.056 | 2.681 | 1.972 | 2.542 | 2.444 | 2.639 | 2.194 | 2.528 | |

| 14 | 3.010 | 2.663 | 1.918 | 2.490 | 2.337 | 2.561 | 2.051 | 2.561 | |

| 16 | 2.914 | 2.531 | 1.820 | 2.430 | 2.320 | 2.469 | 2.039 | 2.492 | |

| 18 | 2.975 | 2.562 | 1.710 | 2.377 | 2.290 | 2.444 | 1.963 | 2.444 | |

| 20 | 3.050 | 2.500 | 1.645 | 2.350 | 2.300 | 2.465 | 1.905 | 2.400 | |

| 22 | 3.140 | 2.475 | 1.649 | 2.360 | 2.264 | 2.426 | 1.855 | 2.426 | |

| 24 | 3.229 | 2.524 | 1.597 | 2.500 | 2.302 | 2.417 | 1.913 | 2.385 | |

| crime-moreno | 2 | 7.000 | 7.000 | 6.000 | 7.000 | 7.000 | 7.000 | 7.000 | 7.000 |

| 4 | 4.750 | 4.750 | 3.875 | 4.750 | 4.750 | 4.750 | 4.750 | 4.750 | |

| 6 | 4.389 | 4.056 | 3.444 | 4.056 | 4.056 | 4.056 | 4.056 | 4.056 | |

| 8 | 4.063 | 3.938 | 3.156 | 3.781 | 3.781 | 3.969 | 3.781 | 3.969 | |

| 10 | 3.960 | 3.700 | 2.960 | 3.620 | 3.580 | 3.700 | 3.700 | 3.700 | |

| 12 | 3.917 | 3.667 | 2.819 | 3.556 | 3.556 | 3.667 | 3.667 | 3.667 | |

| 14 | 3.929 | 3.592 | 2.714 | 3.520 | 3.490 | 3.510 | 3.510 | 3.510 | |

| 16 | 3.891 | 3.602 | 2.633 | 3.469 | 3.453 | 3.508 | 3.508 | 3.508 | |

| 18 | 3.883 | 3.568 | 2.568 | 3.395 | 3.383 | 3.500 | 3.457 | 3.457 | |

| 20 | 3.910 | 3.535 | 2.505 | 3.380 | 3.315 | 3.480 | 3.445 | 3.445 | |

| 22 | 3.942 | 3.521 | 2.603 | 3.339 | 3.335 | 3.446 | 3.446 | 3.446 | |

| 24 | 3.983 | 3.545 | 2.712 | 3.337 | 3.358 | 3.465 | 3.441 | 3.441 | |

| hamsterster | 5 | 3.160 | 3.400 | 3.000 | 3.240 | 3.080 | 3.240 | 3.240 | 3.240 |

| 10 | 2.500 | 2.400 | 2.000 | 2.300 | 2.420 | 2.400 | 2.300 | 2.400 | |

| 15 | 2.333 | 2.129 | 1.667 | 2.084 | 2.147 | 2.129 | 2.129 | 2.129 | |

| 20 | 2.350 | 2.010 | 1.500 | 1.940 | 2.035 | 1.970 | 1.975 | 1.970 | |

| 25 | 2.302 | 1.944 | 1.400 | 1.902 | 1.938 | 1.944 | 1.886 | 1.922 | |

| 30 | 2.316 | 1.922 | 1.836 | 1.873 | 1.933 | 1.907 | 1.867 | 1.907 | |

| 35 | 2.564 | 1.904 | 2.055 | 1.847 | 1.909 | 1.893 | 1.828 | 1.883 | |

| 40 | 2.636 | 1.893 | 2.195 | 1.839 | 1.884 | 1.893 | 1.801 | 1.873 | |

| 45 | 2.794 | 1.892 | 2.246 | 1.846 | 1.853 | 1.878 | 1.779 | 1.844 | |

| 50 | 2.818 | 1.868 | 2.218 | 1.837 | 1.862 | 1.850 | 1.792 | 1.839 | |

| 55 | 2.831 | 1.836 | 2.205 | 1.830 | 1.853 | 1.837 | 1.774 | 1.825 | |

| 60 | 2.936 | 1.816 | 2.186 | 1.822 | 1.847 | 1.816 | 1.770 | 1.813 | |

| citeseer | 5 | 7.560 | 8.840 | 6.840 | 8.520 | 7.080 | 8.760 | 7.000 | 8.520 |

| 10 | 6.980 | 5.720 | 4.140 | 5.320 | 4.400 | 5.720 | 4.460 | 5.360 | |

| 15 | 6.796 | 5.471 | 3.222 | 4.342 | 3.578 | 4.973 | 4.244 | 4.644 | |

| 20 | 6.735 | 5.380 | 2.960 | 4.055 | 3.170 | 4.355 | 3.675 | 4.360 | |

| 25 | 6.667 | 5.195 | 2.882 | 3.746 | 2.987 | 4.018 | 3.387 | 3.995 | |

| 30 | 6.578 | 5.704 | 2.776 | 3.747 | 2.882 | 3.969 | 3.282 | 3.818 | |

| 35 | 6.582 | 5.346 | 2.770 | 3.648 | 2.788 | 4.350 | 3.137 | 3.761 | |

| 40 | 7.046 | 5.255 | 3.645 | 3.553 | 2.701 | 4.630 | 3.284 | 3.878 | |

| 45 | 7.157 | 5.140 | 4.184 | 3.651 | 2.680 | 4.512 | 3.398 | 4.108 | |

| 50 | 7.271 | 4.978 | 4.040 | 3.838 | 2.705 | 4.384 | 3.423 | 4.262 | |

| 55 | 7.530 | 4.964 | 3.898 | 3.740 | 2.701 | 4.420 | 3.346 | 4.281 | |

| 60 | 7.661 | 4.928 | 3.779 | 3.882 | 2.857 | 4.391 | 3.307 | 4.171 | |

| politician | 5 | 3.800 | 4.440 | 3.880 | 4.200 | 3.800 | 4.360 | 3.800 | 4.360 |

| 10 | 3.200 | 2.860 | 2.560 | 2.820 | 2.560 | 2.820 | 2.720 | 2.820 | |

| 15 | 3.222 | 2.858 | 2.040 | 2.404 | 2.236 | 2.502 | 2.449 | 2.502 | |

| 20 | 3.040 | 2.780 | 1.840 | 2.290 | 2.040 | 2.480 | 2.255 | 2.480 | |

| 25 | 2.978 | 2.661 | 1.723 | 2.270 | 1.960 | 2.347 | 2.107 | 2.315 | |

| 30 | 3.047 | 2.547 | 1.696 | 2.269 | 1.947 | 2.442 | 1.984 | 2.347 | |

| 35 | 3.083 | 2.520 | 1.612 | 2.282 | 1.981 | 2.487 | 2.017 | 2.370 | |

| 40 | 3.156 | 2.529 | 1.603 | 2.243 | 2.089 | 2.421 | 2.054 | 2.390 | |

| 45 | 3.209 | 2.492 | 1.584 | 2.286 | 2.126 | 2.415 | 2.075 | 2.360 | |

| 50 | 3.240 | 2.506 | 1.558 | 2.295 | 2.152 | 2.398 | 2.101 | 2.382 | |

| 55 | 3.304 | 2.528 | 1.549 | 2.279 | 2.149 | 2.467 | 2.059 | 2.428 | |

| 60 | 3.319 | 2.565 | 1.540 | 2.307 | 2.217 | 2.497 | 2.137 | 2.497 | |

| US-Grid | 5 | 21.640 | 26.040 | 10.520 | 17.400 | 10.680 | 15.240 | 17.560 | 15.240 |

| 10 | 16.160 | 19.080 | 6.040 | 12.820 | 9.680 | 12.680 | 16.620 | 11.300 | |

| 15 | 16.084 | 15.978 | 7.098 | 10.884 | 10.716 | 11.604 | 16.164 | 11.604 | |

| 20 | 16.250 | 15.525 | 7.080 | 10.880 | 13.330 | 12.100 | 15.330 | 11.625 | |

| 25 | 16.181 | 17.470 | 6.670 | 12.670 | 13.707 | 12.014 | 14.747 | 11.611 | |

| 30 | 16.196 | 17.311 | 6.118 | 12.231 | 12.713 | 12.309 | 14.544 | 12.180 | |

| 35 | 16.019 | 16.432 | 5.767 | 11.828 | 12.817 | 11.540 | 14.822 | 11.356 | |

| 40 | 16.239 | 15.748 | 6.365 | 12.226 | 13.899 | 11.333 | 14.644 | 11.726 | |

| 45 | 15.960 | 15.511 | 9.611 | 12.616 | 14.705 | 12.003 | 14.371 | 11.597 | |

| 50 | 15.779 | 16.338 | 12.365 | 12.835 | 14.878 | 11.865 | 14.666 | 11.865 | |

| 55 | 15.961 | 16.753 | 14.548 | 12.752 | 14.845 | 12.129 | 14.658 | 11.760 | |

| 60 | 15.974 | 16.627 | 15.972 | 13.081 | 15.172 | 12.082 | 14.679 | 11.711 | |

| pgp | 5 | 6.120 | 6.360 | 5.80 | 6.360 | 5.960 | 5.960 | 5.960 | 5.960 |

| 10 | 4.280 | 4.680 | 3.460 | 3.960 | 3.640 | 3.940 | 3.780 | 3.940 | |

| 15 | 3.827 | 4.040 | 2.627 | 3.516 | 3.000 | 3.364 | 2.991 | 3.364 | |

| 20 | 3.880 | 3.555 | 2.230 | 3.205 | 2.645 | 3.170 | 2.630 | 3.100 | |

| 25 | 3.979 | 3.317 | 2.002 | 2.978 | 2.466 | 2.990 | 2.389 | 2.949 | |

| 30 | 4.047 | 3.291 | 1.849 | 2.940 | 2.522 | 3.044 | 2.351 | 2.787 | |

| 35 | 4.024 | 3.242 | 1.749 | 2.909 | 2.419 | 2.956 | 2.365 | 2.783 | |

| 40 | 4.151 | 3.116 | 1.685 | 2.815 | 2.464 | 2.960 | 2.309 | 2.736 | |

| 45 | 4.318 | 3.034 | 1.726 | 2.784 | 2.421 | 2.934 | 2.211 | 2.714 | |

| 50 | 4.282 | 2.984 | 1.936 | 2.853 | 2.397 | 2.931 | 2.121 | 2.793 | |

| 55 | 4.319 | 2.925 | 1.992 | 2.893 | 2.377 | 2.896 | 2.132 | 2.751 | |

| 60 | 4.449 | 2.885 | 2.034 | 2.871 | 2.383 | 2.829 | 2.141 | 2.767 | |

| indochina-2004 | 5 | 8.080 | 7.920 | 6.400 | 8.240 | 8.720 | 7.200 | 6.400 | 7.200 |

| 10 | 6.160 | 5.940 | 3.700 | 5.640 | 5.520 | 4.660 | 3.700 | 4.660 | |

| 15 | 5.724 | 5.200 | 2.800 | 5.173 | 4.293 | 3.813 | 3.209 | 3.813 | |

| 20 | 5.620 | 5.260 | 2.350 | 4.815 | 4.315 | 3.425 | 2.860 | 3.210 | |

| 25 | 5.363 | 5.206 | 2.080 | 4.611 | 3.779 | 3.456 | 2.499 | 3.456 | |

| 30 | 5.256 | 4.896 | 1.900 | 4.420 | 3.400 | 3.507 | 2.293 | 3.293 | |

| 35 | 5.144 | 4.596 | 1.771 | 4.377 | 3.229 | 3.445 | 2.460 | 3.198 | |

| 40 | 5.095 | 4.294 | 1.675 | 4.316 | 3.344 | 3.609 | 2.365 | 3.336 | |

| 45 | 5.146 | 4.090 | 1.600 | 4.118 | 3.323 | 4.041 | 2.655 | 3.670 | |

| 50 | 5.151 | 4.076 | 1.540 | 4.039 | 3.318 | 3.911 | 2.660 | 3.911 | |

| 55 | 5.120 | 3.915 | 2.446 | 4.005 | 3.326 | 3.786 | 2.784 | 3.759 | |

| 60 | 5.268 | 3.919 | 3.083 | 3.937 | 3.312 | 3.708 | 3.298 | 3.696 | |

| Density | 0.0005 |

| Maximum degree | 19 |

| Average number of triangles | 0.3953 |

| Average clustering coefficient | 0.08010 |

| (a) dolphins | (b) dublin | (c) crime-moreno | ||||||||||

| PaC | PaC, p = 0.1 | PaC, p = 0.5 | PaC-p | PaC | PaC, p = 0.1 | PaC, p = 0.5 | PaC-p | PaC | PaC, p = 0.1 | PaC, p = 0.5 | PaC-p | |

| 10 | 29.79 | 28.35 | 29.51 | 27.66 | 124.49 | 118.06 | 122.07 | 113.80 | 75.38 | 72.12 | 74.00 | 71.12 |

| 20 | 39.76 | 36.73 | 38.48 | 35.61 | 146.21 | 141.58 | 143.25 | 128.28 | 109.61 | 105.71 | 108.78 | 104.11 |

| 30 | 47.87 | 42.52 | 47.18 | 41.16 | 162.57 | 154.81 | 160.66 | 140.68 | 138.69 | 133.81 | 136.09 | 125.75 |

| (d) hamsterster | (e) citeseer | (f) politician | ||||||||||

| PaC | PaC, p = 0.1 | PaC, p = 0.5 | PaC-p | PaC | PaC, p = 0.1 | PaC, p = 0.5 | PaC-p | PaC | PaC, p = 0.1 | PaC, p = 0.5 | PaC-p | |

| 10 | 168.09 | 166.19 | 164.04 | 163.54 | 168.12 | 134.66 | 152.84 | 128.58 | 330.06 | 298.21 | 331.31 | 267.98 |

| 20 | 208.69 | 194.71 | 205.25 | 192.78 | 214.75 | 181.55 | 209.99 | 161.76 | 422.59 | 355.27 | 417.38 | 351.22 |

| 30 | 236.48 | 224.51 | 236.28 | 212.51 | 248.97 | 209.03 | 244.10 | 172.37 | 474.58 | 434.98 | 459.09 | 375.31 |

| (g) US-Grid | (h) pgp | (i) indochina-2004 | ||||||||||

| PaC | PaC, p = 0.1 | PaC, p = 0.5 | PaC-p | PaC | PaC, p = 0.1 | PaC, p = 0.5 | PaC-p | PaC | PaC, p = 0.1 | PaC, p = 0.5 | PaC-p | |

| 10 | 226.36 | 197.74 | 216.78 | 167.65 | 524.56 | 500.50 | 522.18 | 500.71 | 1245.81 | 1220.87 | 1228.70 | 1195.42 |

| 20 | 317.27 | 287.24 | 307.78 | 198.98 | 593.33 | 531.56 | 564.49 | 506.63 | 1319.11 | 1278.30 | 1302.22 | 1220.15 |

| 30 | 386.11 | 352.54 | 378.62 | 258.71 | 647.42 | 539.63 | 623.83 | 530.57 | 1371.87 | 1322.95 | 1355.90 | 1236.27 |

| Metric | PaC | DC |

|---|---|---|

| Sample size (n) | 10,000 | 10,000 |

| Mean (M) | 100.95 | 100.31 |

| Standard deviation () | 10.91 | 10.94 |

| 95% CI of the mean | [100.74, 101.16] | [100.09, 100.52] |

| Mean difference () | 0.64 | |

| 95% CI of the mean difference | [0.34, 0.94] | |

| t-statistic | 4.14 | |

| Degrees of freedom () | 19,998 | |

| p-value | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Liu, W.; Jiang, W.; Yang, J.; Chen, L. Interest as the Engine: Leveraging Diverse Hybrid Propagation for Influence Maximization in Interest-Based Social Networks. Information 2026, 17, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010003

Li J, Liu W, Jiang W, Yang J, Chen L. Interest as the Engine: Leveraging Diverse Hybrid Propagation for Influence Maximization in Interest-Based Social Networks. Information. 2026; 17(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jian, Wei Liu, Wenxin Jiang, Jinhao Yang, and Ling Chen. 2026. "Interest as the Engine: Leveraging Diverse Hybrid Propagation for Influence Maximization in Interest-Based Social Networks" Information 17, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010003

APA StyleLi, J., Liu, W., Jiang, W., Yang, J., & Chen, L. (2026). Interest as the Engine: Leveraging Diverse Hybrid Propagation for Influence Maximization in Interest-Based Social Networks. Information, 17(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010003