BWO-Optimized CNN-BiGRU-Attention Model for Short-Term Load Forecasting

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We quantitatively analyze the dynamic coupling between meteorological factors and power load using Pearson correlation coefficients, identifying key input features to reduce data redundancy.

- We construct a CNN-BiGRU-Attention model to capture bidirectional temporal dependencies and spatial features. Crucially, we integrate the Beluga Whale Optimization (BWO) algorithm to autonomously tune the model’s hyperparameters, thereby overcoming the limitations of manual tuning and preventing entrapment in local optima.

- The proposed model is rigorously evaluated against five baseline models (BP, GRU, BiGRU, BiGRU-Attention, and CNN-BiGRU-Attention) using real-world datasets, demonstrating superior performance in terms of MAPE, RMSE, and .

2. Literature Review

2.1. Evolution of Load Forecasting Methods

2.2. Hybrid Architectures and Attention Mechanisms

2.3. Hyperparameter Optimization Strategies

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset

3.2. Data Preprocessing

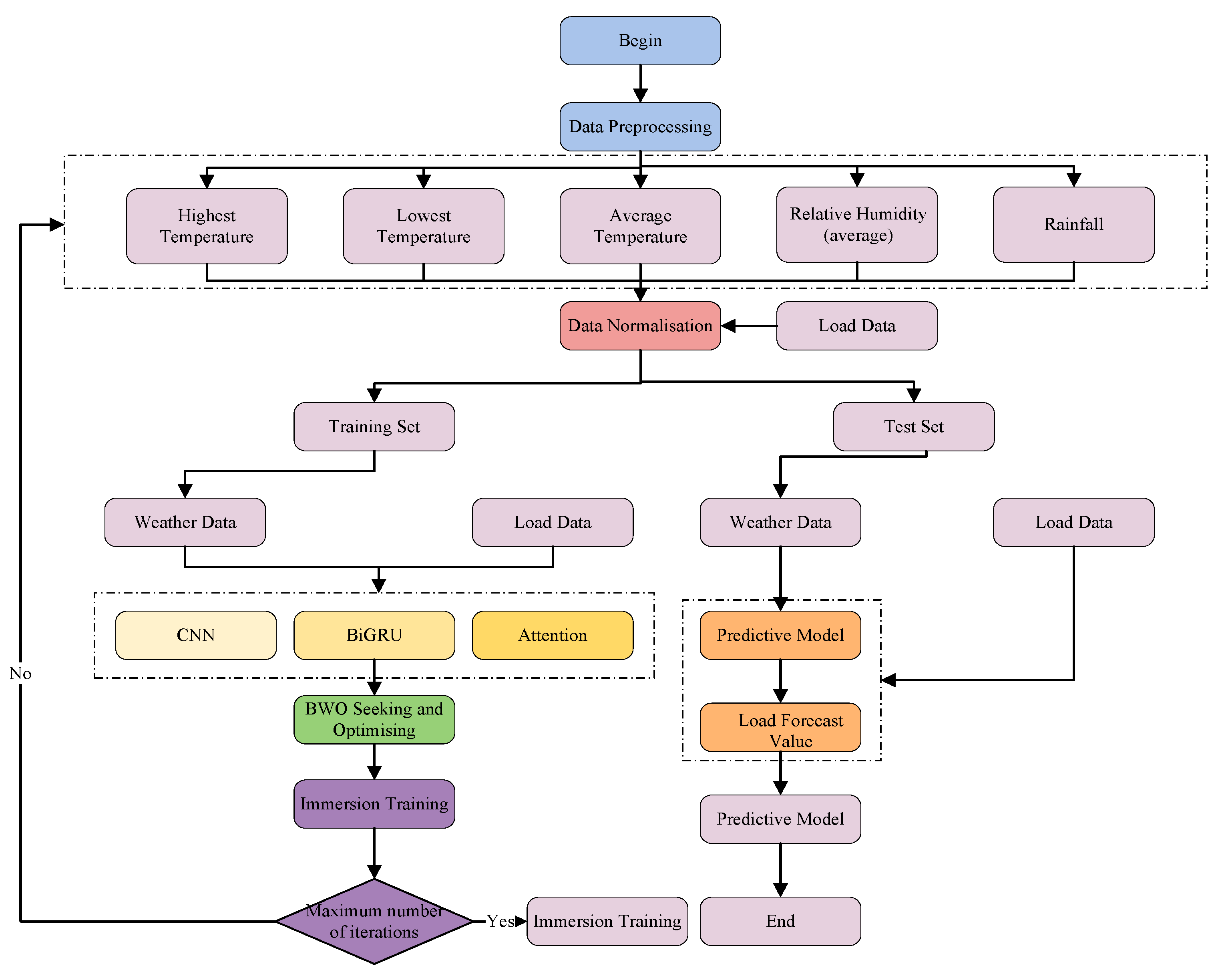

3.3. Process Flow

4. CNN-BiGRU-Attention Based on Whale Optimization

4.1. Convolutional Neural Network(CNN)

4.2. Bidirectional Gated Recirculation Unit(BiGRU)

4.3. Attention Mechanism(Attention)

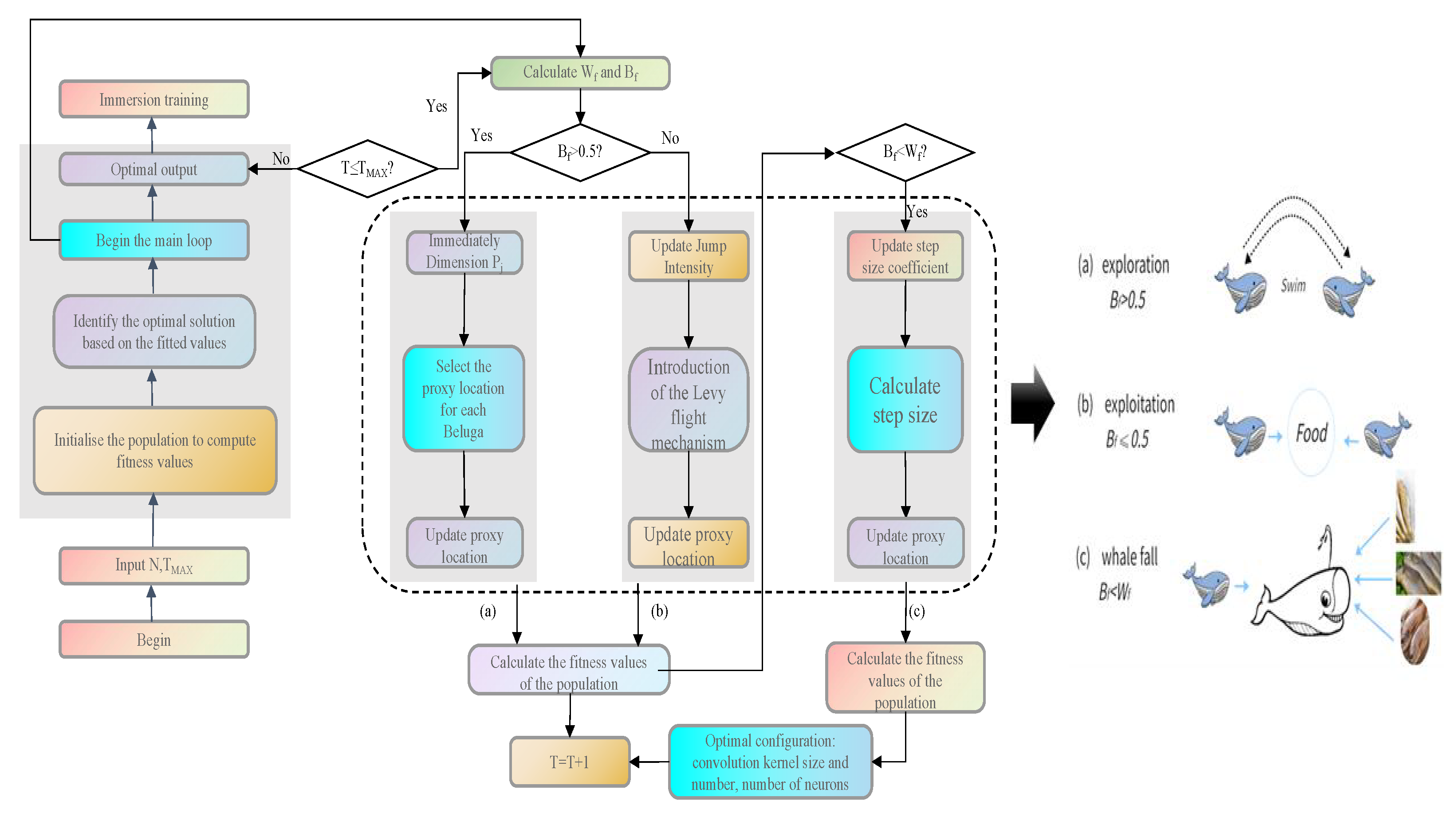

4.4. Beluga Whale Optimization(BWO)

5. Experimental Results

5.1. Evaluation Indicators

- MAE (Mean Absolute Error): measures average magnitude of error in MW.

- RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error): By squaring errors, RMSE penalizes large deviations heavily. In grid security, a large prediction error (e.g., missed peak) is far more dangerous than many small errors. Thus, RMSE is the primary metric for operational reliability.

- MAPE (Mean Absolute Percentage Error): provides a percentage-based error measure, critical for economic assessment and electricity market bidding.

- (Coefficient of Determination): Measures how well the model replicates the variance and shape of the load curve.

5.2. Experimental Setup

5.3. Loss Function

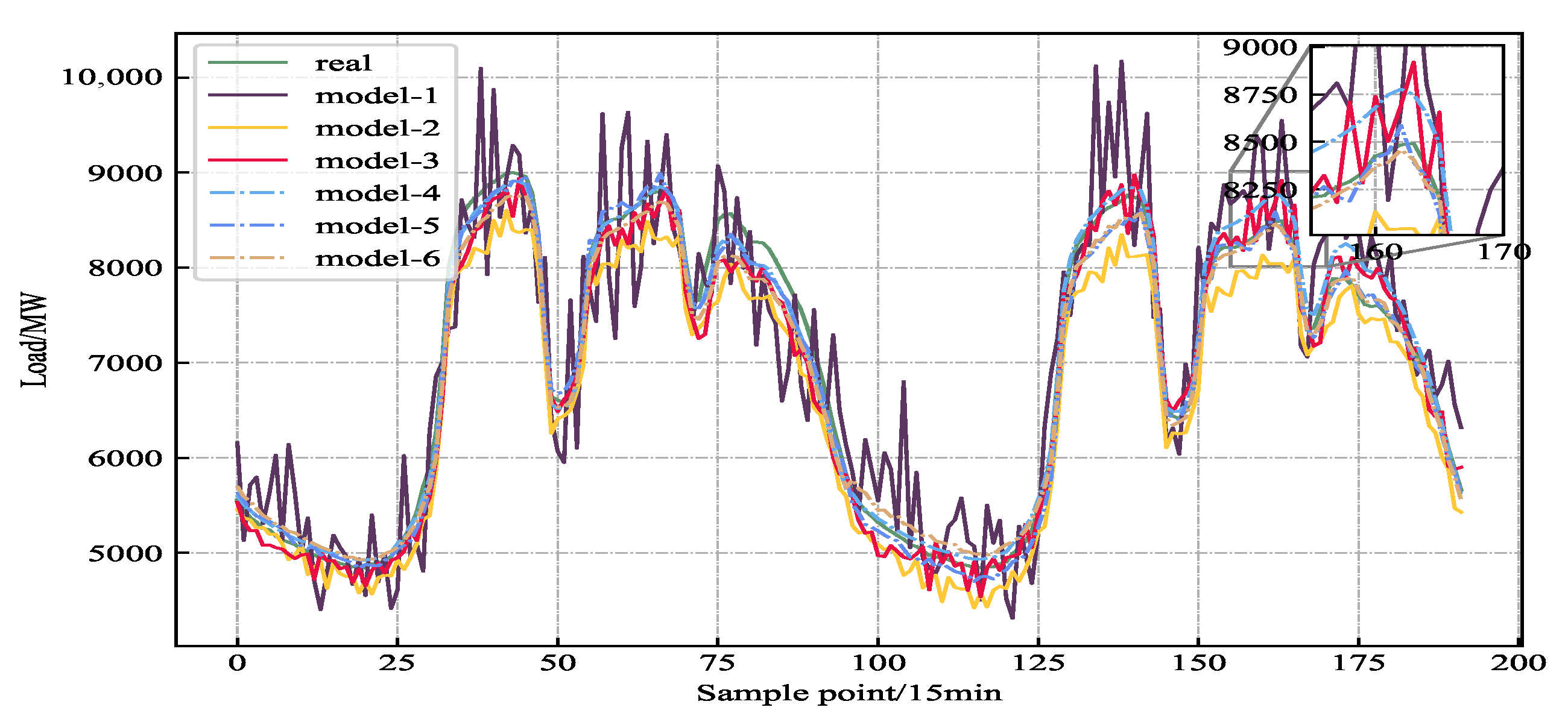

5.4. Model Comparison Analysis

5.5. Convergence Effect of the Optimized White Whale Model

6. Conclusions and Future Works

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dong, Q.; Huang, R.; Cui, C.; Towey, D.; Zhou, L.; Tian, J.; Wang, J. Short-Term Electricity-Load Forecasting by deep learning: A comprehensive survey. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 154, 110980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bossly, A. Metaheuristic Optimization with Deep Learning Enabled Smart Grid Stability Prediction. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2023, 75, 6395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar Madrid, E.; Antonio, N. Short-term electricity load forecasting with machine learning. Information 2021, 12, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuang, R.; Kai, Y.; Jicai, S.; Jiming, Q.; Xiangyu, W.; Yonggen, C. Short-term Power Load Forecasting Based on CNN-BiGRU-Attention. J. Electr. Eng. 2024, 19, 344–350. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Song, J.; Tao, H.; Wang, P.; Mo, H.; Du, W. Quarter-Hourly Power Load Forecasting Based on a Hybrid CNN-BiLSTM-Attention Model with CEEMDAN, K-Means, and VMD. Energies 2025, 18, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtahina, U.; Alahakoon, S.; Wolfs, P. Hyperparameter tuning of load-forecasting models using metaheuristic optimization algorithms—a systematic review. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xing, C. Data source selection based on an improved greedy genetic algorithm. Symmetry 2019, 11, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Liu, P.; Lan, L.; Guo, M.; Guo, H. Enhancing Accuracy in Wind and Photovoltaic Power Forecasting Through Neutral Network and Beluga Whale Optimization Algorithm. Int. J. Multiphys. 2024, 18, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Youssef, H.; Kamel, S.; Hassan, M.H.; Mohamed, E.M.; Belbachir, N. Exploring LBWO and BWO algorithms for demand side optimization and cost efficiency: Innovative approaches to smart home energy management. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 28831–28852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lin, Z.; Feng, Z. Short-term offshore wind speed forecast by seasonal ARIMA-A comparison against GRU and LSTM. Energy 2021, 227, 120492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbiah, S.S.; Chinnappan, J. Deep learning based short term load forecasting with hybrid feature selection. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 210, 108065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazirali, R.; Yaghoubi, E.; Abujazar, M.S.S.; Ahmad, R.; Vakili, A.H. State-of-the-art review on energy and load forecasting in microgrids using artificial neural networks, machine learning, and deep learning techniques. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 225, 109792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, N.; Du, E.; Yan, J.; Han, S.; Liu, Y. A comprehensive review for wind, solar, and electrical load forecasting methods. Glob. Energy Interconnect. 2022, 5, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, D.; Yu, M.; Sun, L.; Gao, T.; Wang, K. Short-term multi-energy load forecasting for integrated energy systems based on CNN-BiGRU optimized by attention mechanism. Appl. Energy 2022, 313, 118801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fargalla, M.A.M.; Yan, W.; Deng, J.; Wu, T.; Kiyingi, W.; Li, G.; Zhang, W. TimeNet: Time2Vec attention-based CNN-BiGRU neural network for predicting production in shale and sandstone gas reservoirs. Energy 2024, 290, 130184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Ye, L.; Zhao, Y.; Dai, B.; Pei, M.; Tang, Y. Review of meta-heuristic algorithms for wind power prediction: Methodologies, applications and challenges. Appl. Energy 2021, 301, 117446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Li, G.; Meng, Z. Beluga whale optimization: A novel nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 251, 109215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiri, M.M.; Aldehim, G.; Alotaibi, F.A.; Alnfiai, M.M.; Assiri, M.; Mahmud, A. Short-term load forecasting in smart grids using hybrid deep learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 23504–23513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gao, J.; Guo, J.; Xie, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, M.J. Optimal loading distribution of chillers based on an improved beluga whale optimization for reducing energy consumption. Energy Build. 2024, 307, 113942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, D.; Wang, K.; Sun, L.; Wu, J.; Xu, X. Short-term photovoltaic power generation forecasting based on random forest feature selection and CEEMD: A case study. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 93, 106389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.Y.; Chan, Y.H. Short-term electric load forecasting using particle swarm optimization-based convolutional neural network. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 126, 106773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Li, J.; Zhu, M. An improved convolutional neural network with load range discretization for probabilistic load forecasting. Energy 2020, 203, 117902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurangzeb, K.; Alhussein, M.; Javaid, K.; Haider, S.I. A pyramid-CNN based deep learning model for power load forecasting of similar-profile energy customers based on clustering. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 14992–15003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Wang, Z.; Ji, W.; Gao, X.; Li, X. A short-term power load forecasting method based on attention mechanism of CNN-GRU. Power Syst. Technol. 2019, 43, 4370–4376. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Liu, C.; Duan, Q. Piggery ammonia concentration prediction method based on CNN-GRU. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1624, 042055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, A.; Tahir, M.A.; Iqbal, N.; Ul-Hasan, A.; Shafait, F.; Kazmi, S.M.R. A novel technique for short-term load forecasting using sequential models and feature engineering. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 96221–96232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Huo, Y.; Fu, L.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y. Load-forecasting method for IES based on LSTM and dynamic similar days with multi-features. Glob. Energy Interconnect. 2023, 6, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurangzeb, K.; Alhussein, M. Deep learning framework for short term power load forecasting, a case study of individual household energy customer. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Advances in the Emerging Computing Technologies (AECT), Al Madinah Al Munawwarah, Saudi Arabia, 10 February 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatello, M.; Martschenko, D.O.; Cho, M.K.; Brothers, K.B. Data sharing and community-engaged research. Science 2022, 378, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X. Spatiotemporal feature learning based hour-ahead load forecasting for energy internet. Electronics 2020, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisvari, A.; Lin, Z.; Liu, X. Wind power forecasting–A data-driven method along with gated recurrent neural network. Renew. Energy 2021, 163, 1895–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shi, J.; Yang, W.; Yin, Q. High and low frequency wind power prediction based on Transformer and BiGRU-Attention. Energy 2024, 288, 129753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Luo, Y.; Fang, Z.M.; Dou, F. Short-term power load forecasting method based on Attention-BiLSTM-LSTM neural network. J. Comput. Appl. 2021, 41, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G.; Hu, G.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Y. A novel algorithm system for wind power prediction based on RANSAC data screening and Seq2Seq-Attention-BiGRU model. Energy 2023, 283, 128986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, S.C.; Lin, S.S. Improved beluga whale optimization for solving the simulation optimization problems with stochastic constraints. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Single Model | Mixed Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 |

| Model | Architecture | MAPE | RMSE | MAE | Improvement Logic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | BP | 5.821 | 345.67 | 278.45 | 0.8277 | Baseline |

| Model 2 | GRU | 3.456 | 210.34 | 165.23 | 0.9302 | + Temporal memory (captures sequence). |

| Model 3 | BiGRU | 2.631 | 158.92 | 125.67 | 0.9436 | + Bidirectionality (captures future context). |

| Model 4 | BiGRU-Attn | 2.158 | 132.45 | 103.12 | 0.9521 | + Attention (weights critical moments). |

| Model 5 | CNN-BiGRU-Attn | 1.783 | 105.78 | 80.56 | 0.9619 | + Spatial features (CNN cleans input). |

| Model 6 | BWO-Optimized | 1.585 | 92.46 | 63.5 | 0.9758 | + Global Optimization (avoids local optima). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wu, R.; Wen, X. BWO-Optimized CNN-BiGRU-Attention Model for Short-Term Load Forecasting. Information 2026, 17, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010006

Wu R, Wen X. BWO-Optimized CNN-BiGRU-Attention Model for Short-Term Load Forecasting. Information. 2026; 17(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Ruihan, and Xin Wen. 2026. "BWO-Optimized CNN-BiGRU-Attention Model for Short-Term Load Forecasting" Information 17, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010006

APA StyleWu, R., & Wen, X. (2026). BWO-Optimized CNN-BiGRU-Attention Model for Short-Term Load Forecasting. Information, 17(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010006