A Crowd Simulation Framework in Special Natural Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

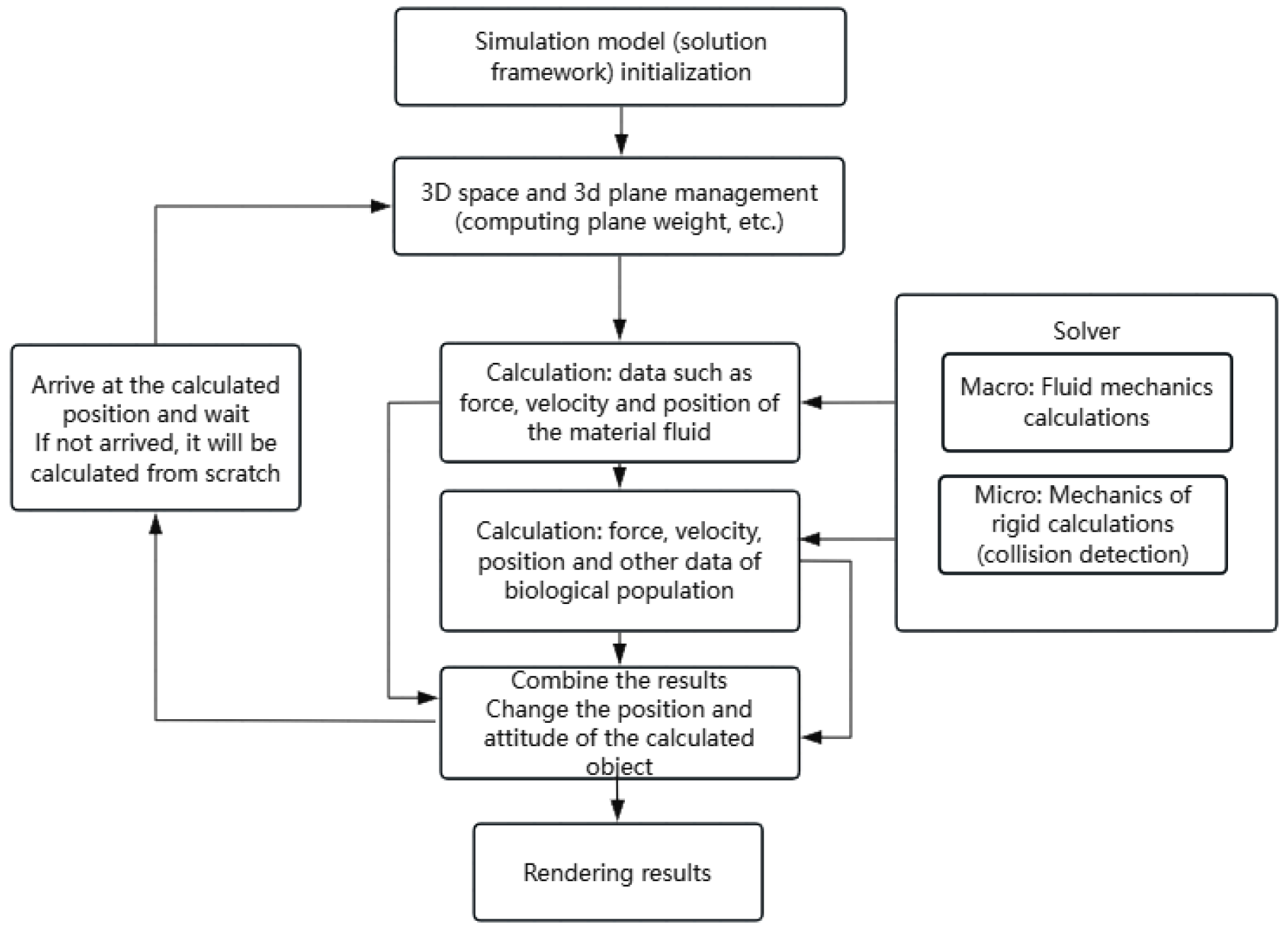

3. Methods

- •

- : The object’s velocity;

- •

- : The force acting on the object;

- •

- : The object’s position.

- •

- Solid type: Densely packed entities exhibiting strong inter-molecular forces.

- •

- Liquid type: Entities with weaker inter-molecular forces, allowing for greater flexibility in motion.

3.1. Forces Computation

- •

- represents external forces, typically gravity, expressed as .

- •

- accounts for pressure-induced forces, defined as . This force moves particles from high-pressure to low-pressure regions and is equal to the gradient of the pressure field.

- •

- models viscous forces, expressed as , which arises due to velocity differences among particles and depends on the viscosity coefficient.

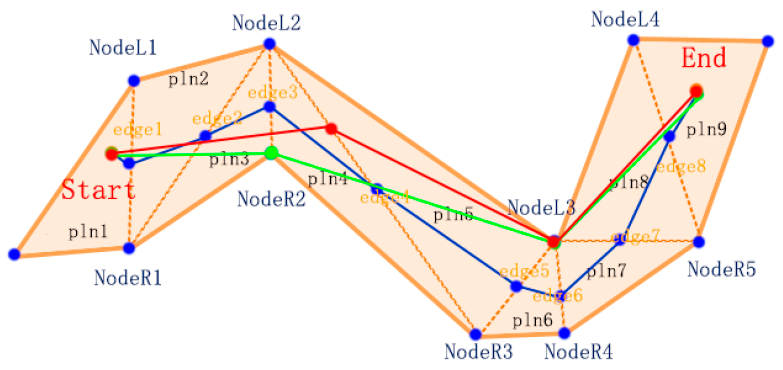

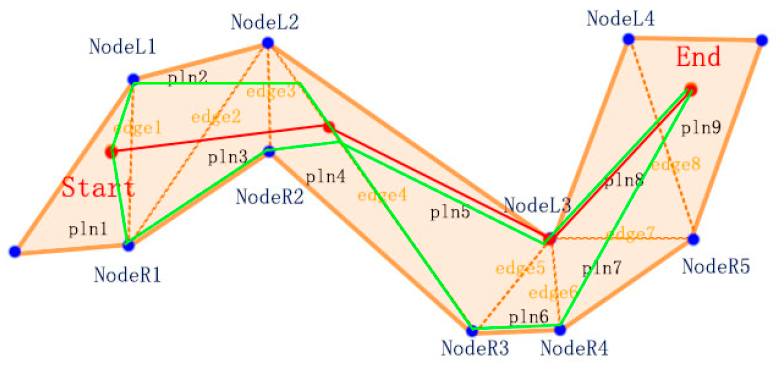

3.2. Global Path Planning

| Algorithm 1. The Variable-rotation Path Finding Method | |

| For a given convex polygon, there are: The starting point is: Start, and the end point is: End. FindNextTracePoint(TracePoints,Edges,End) Input:TracePoints,Edges,End Output:Path Select First P ⊂ TracePoints Make Line L_Start_To_End Find Nearest edgei If(L_Start_To_End intersect with edgei) { Calculate the intersection: cross_point_i; | For each point in {leftPointi, cross_point_i, rightPointi} End } Else { For each point in {leftPointi, rightPointi} End } If TracePoints !=Null Return Step:FindNextTracePoint Else Return Final Path End |

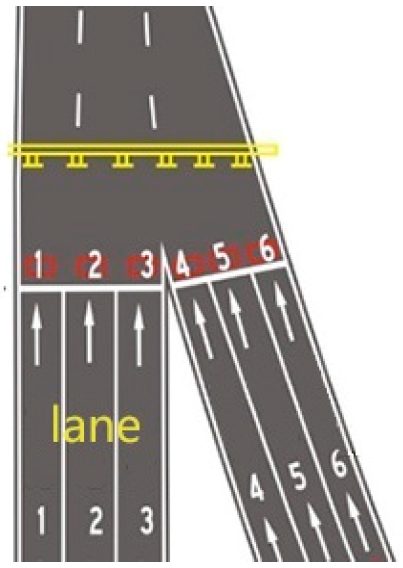

3.3. Local Routing Strategy

| Algorithm 2. Strategy Six ndomain Vs m (The Neighborhood Extremum Method). | |

| For a given convex polygon, there are: The starting point is: Start, and the end point is: End. FindNextTracePoint(TracePoints,Edges,End) Input:TracePoints,Edges,End Output:Path Select First P ⊂ TracePoints Make Line L_Start_To_End Find Nearest edgei If(L_Start_To_End intersect with edgei) { Calculate the intersection: cross_point_i; | For each point in {leftPointi, cross_point_i, rightPointi} End } Else { For each point in {leftPointi, rightPointi} End } If TracePoints !=Null Return Step:FindNextTracePoint Else Return Final Path End |

3.4. Related Algorithms

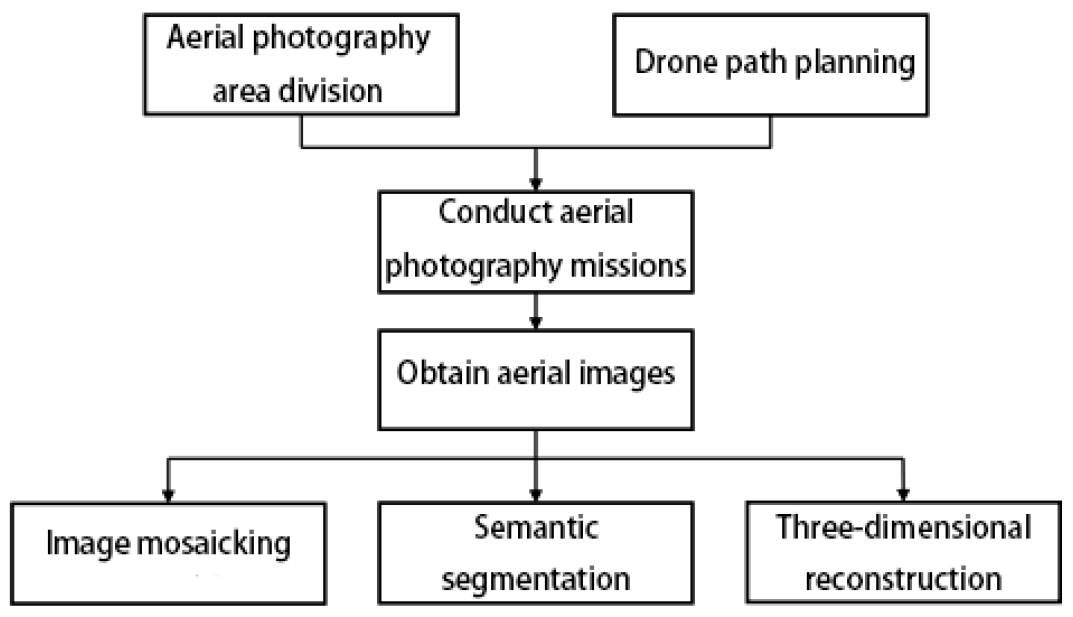

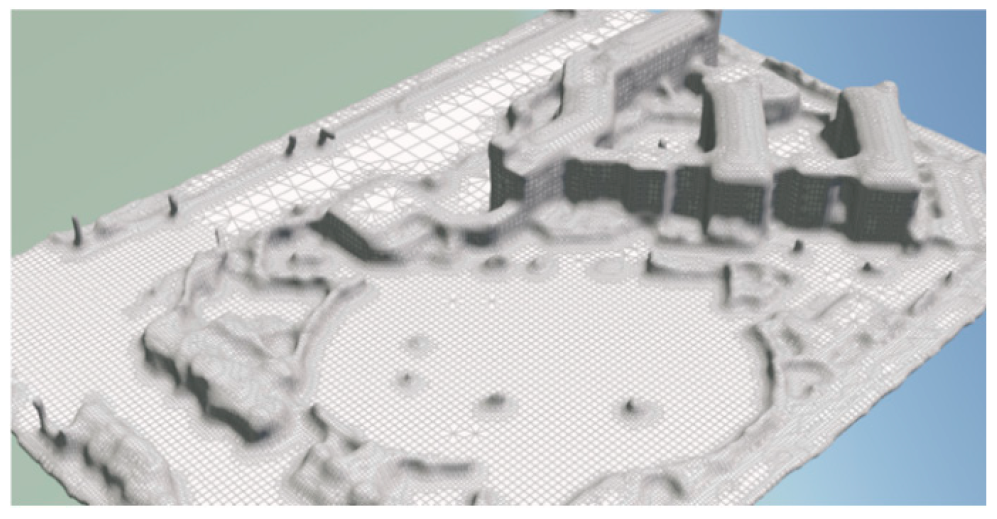

4. Implementation Details

5. Results

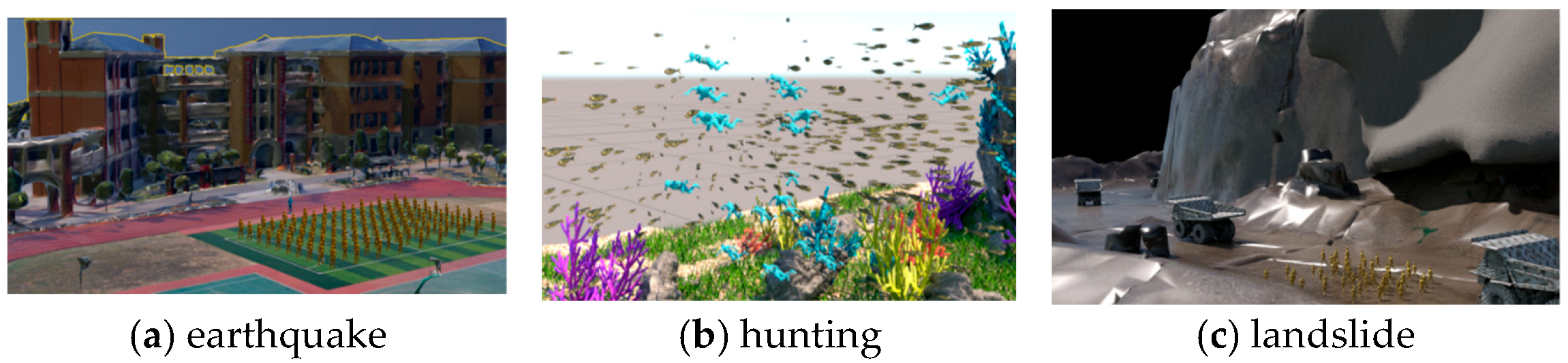

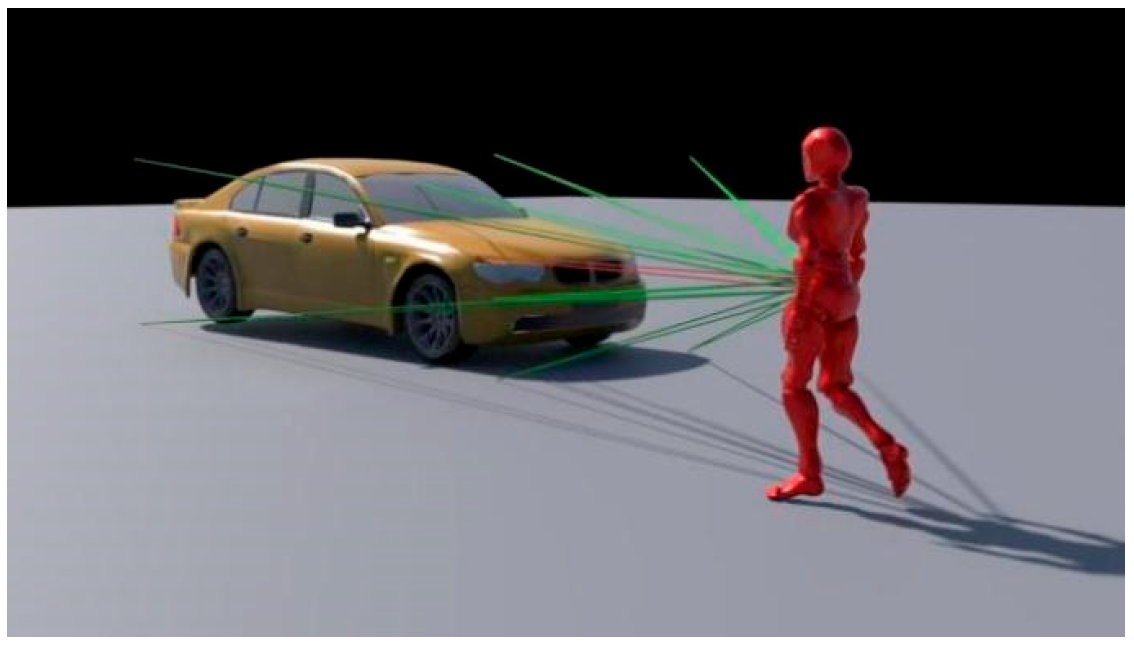

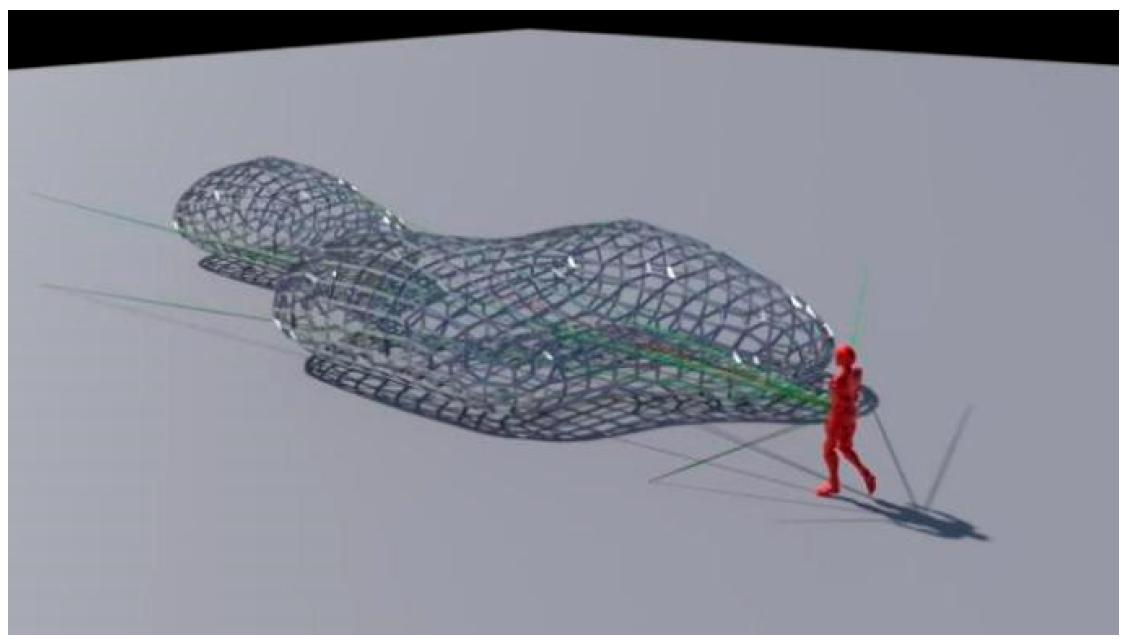

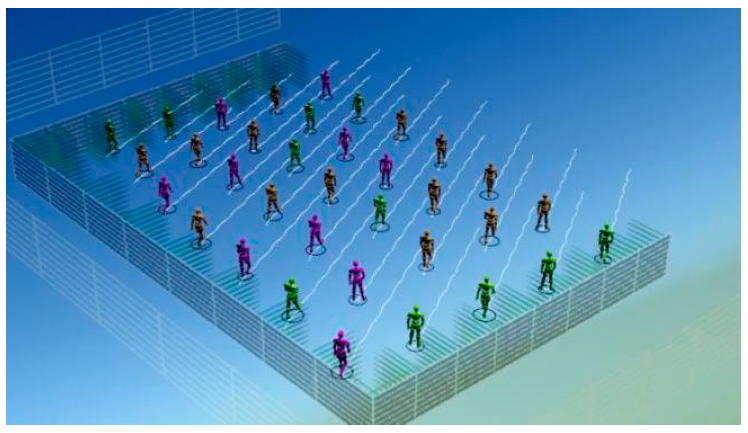

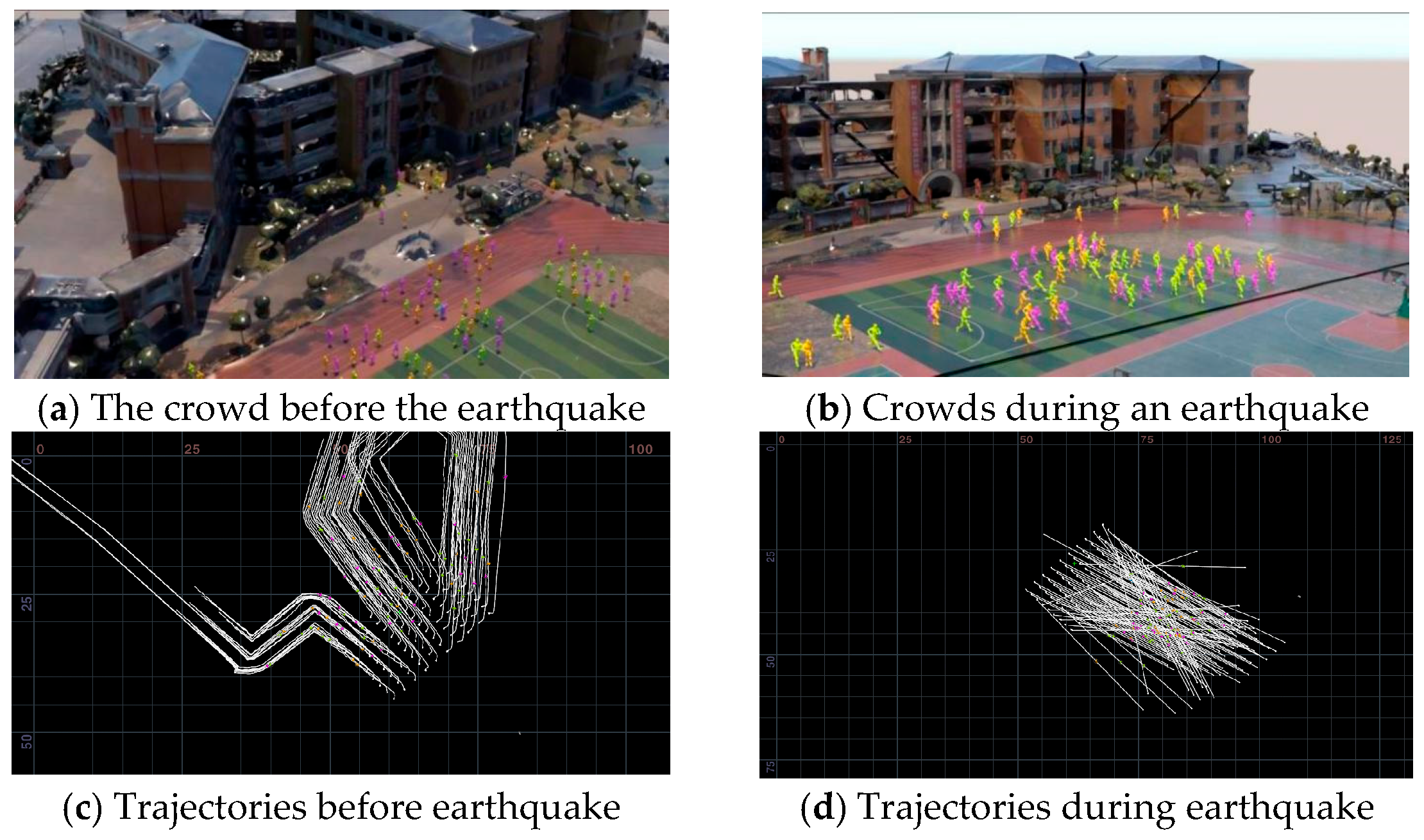

5.1. Outdoor Earthquake Evacuation

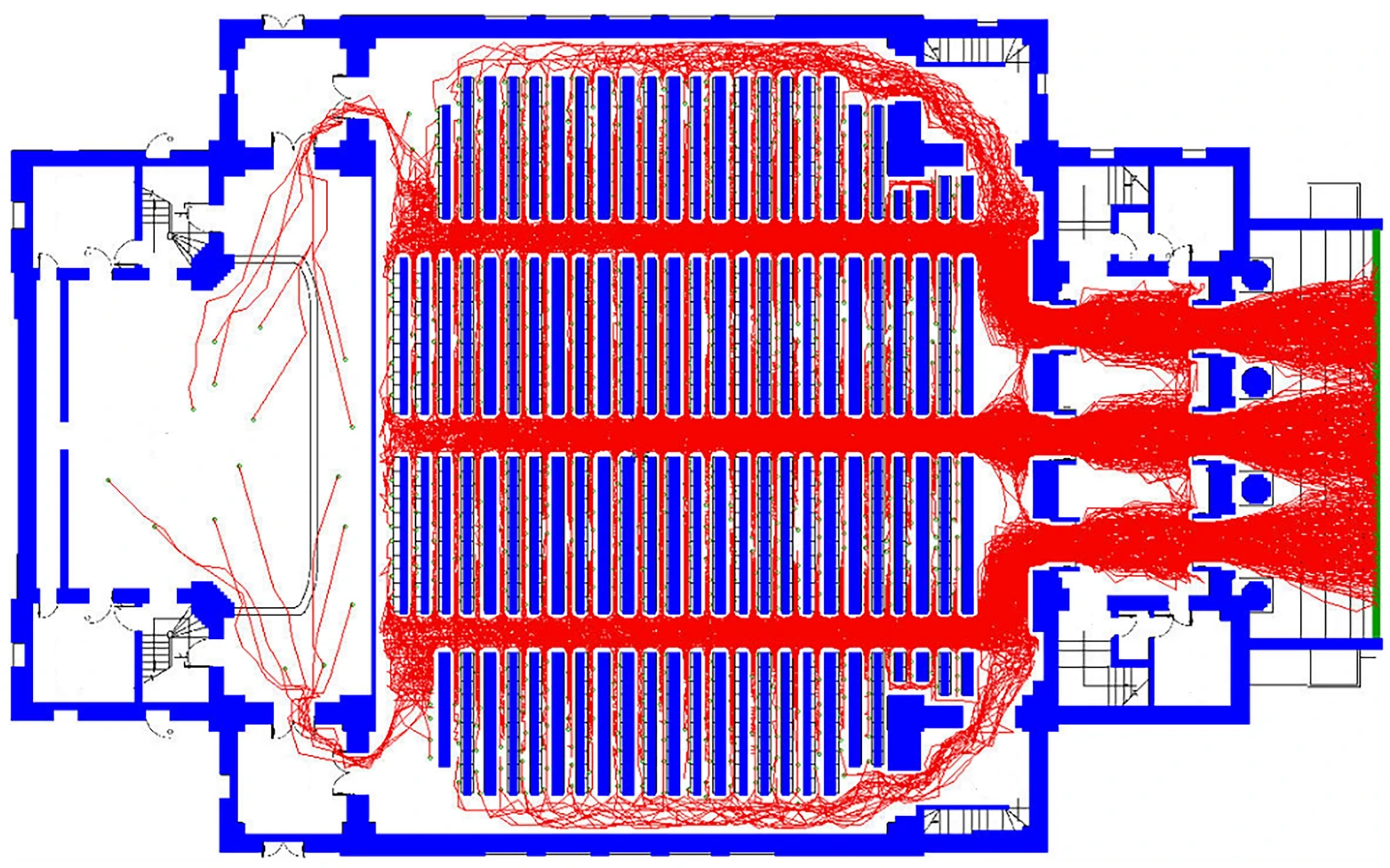

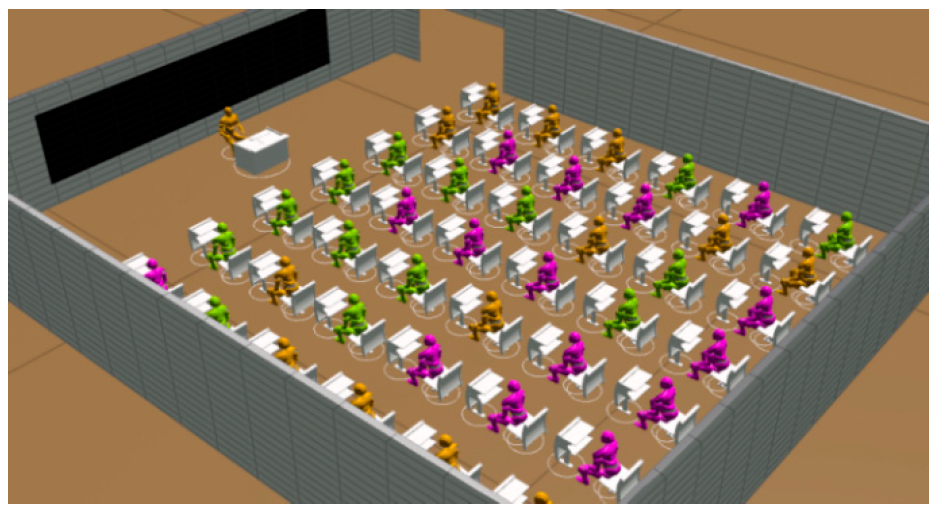

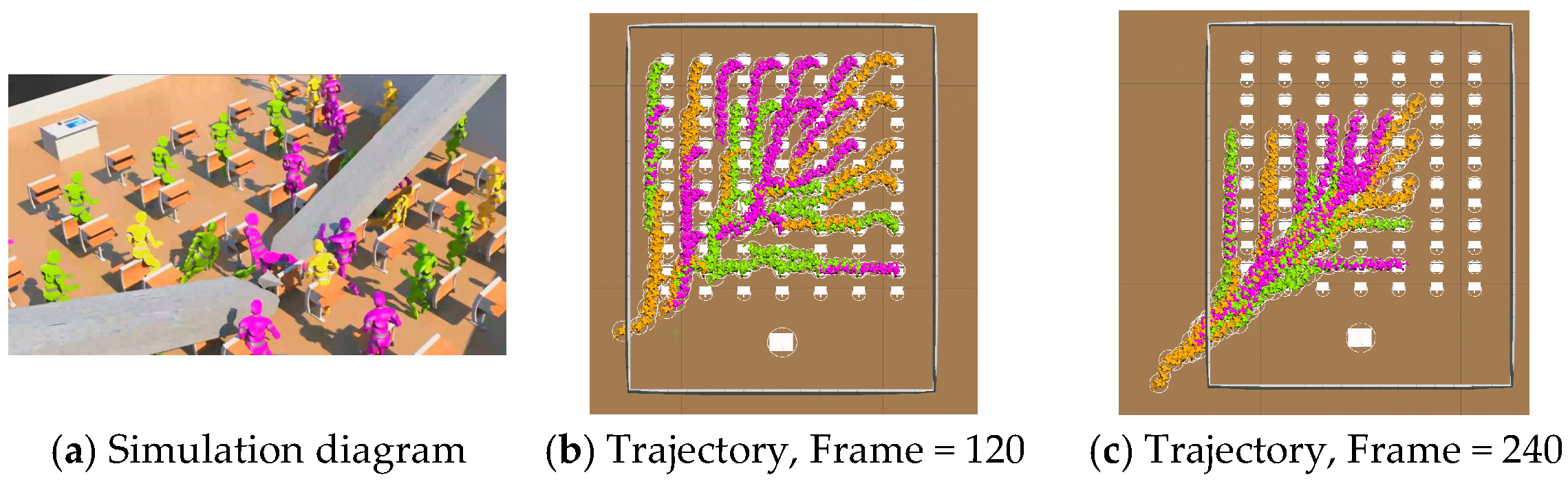

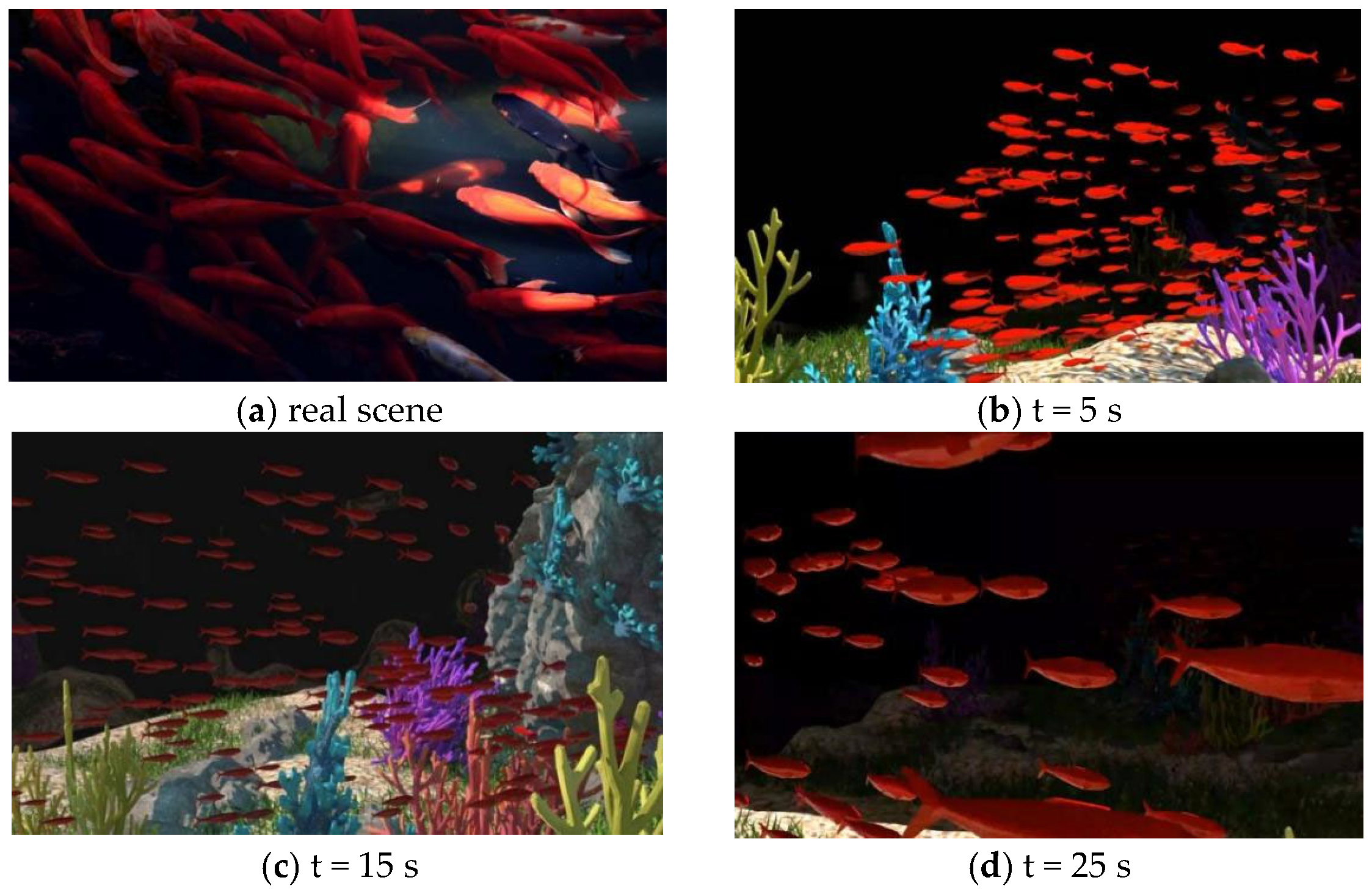

5.2. Indoor Earthquake Evacuation

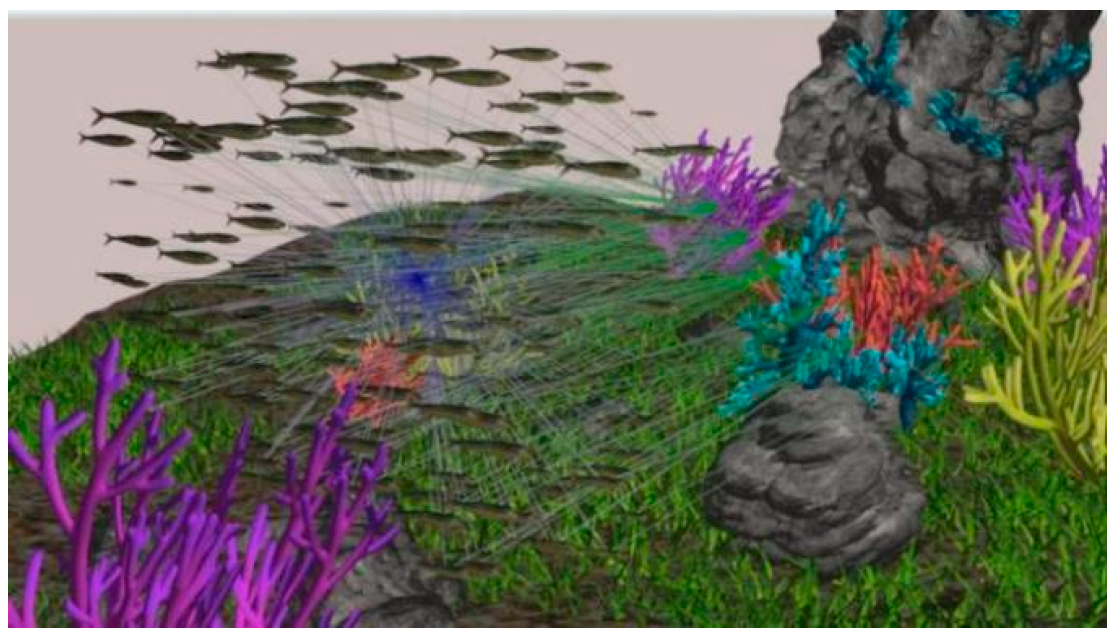

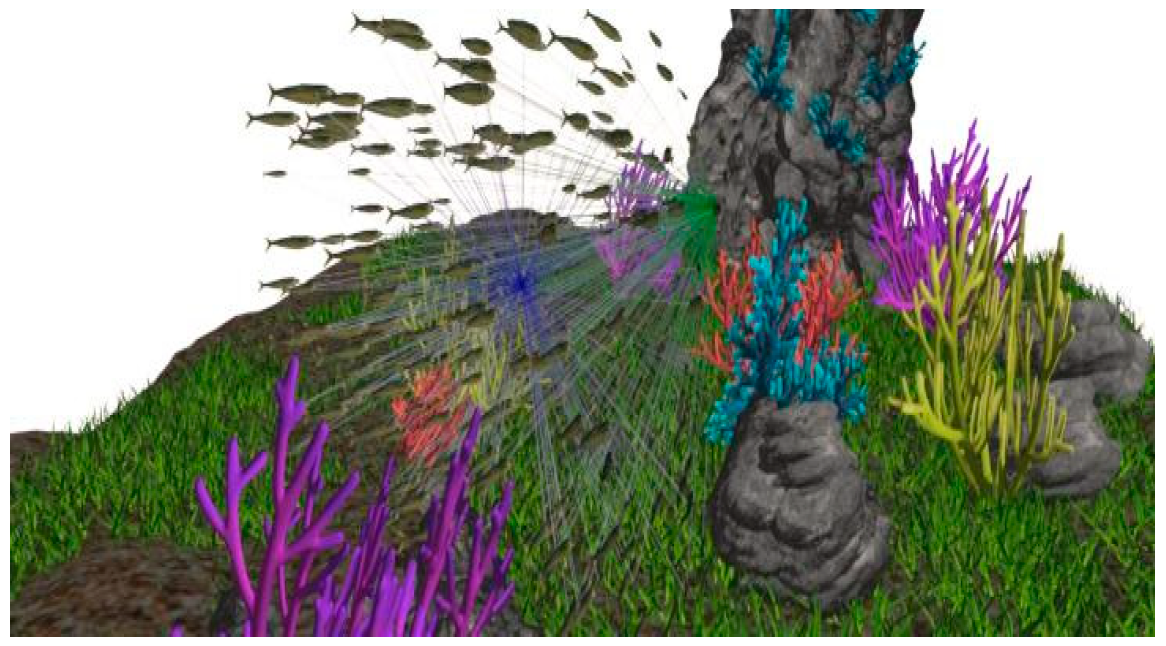

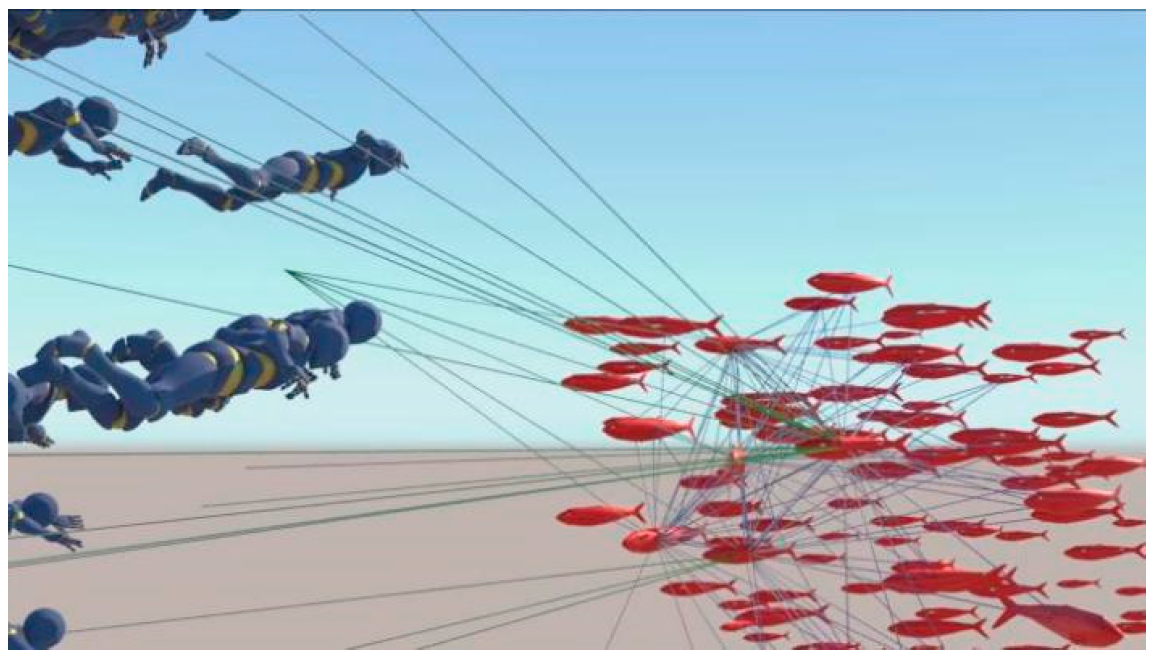

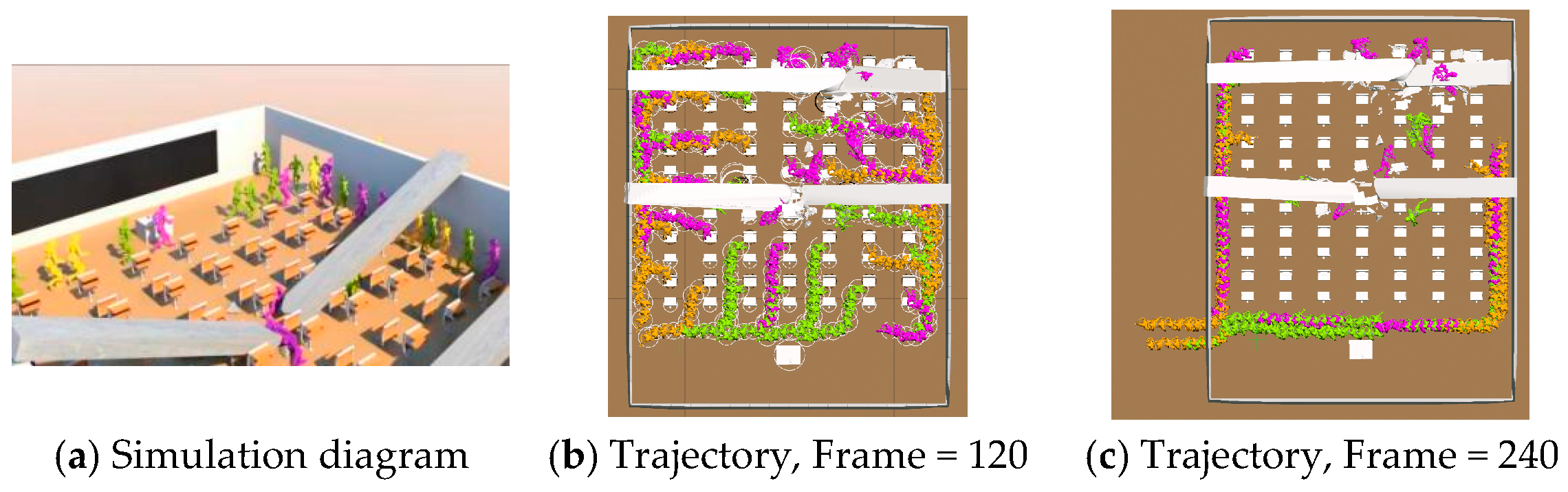

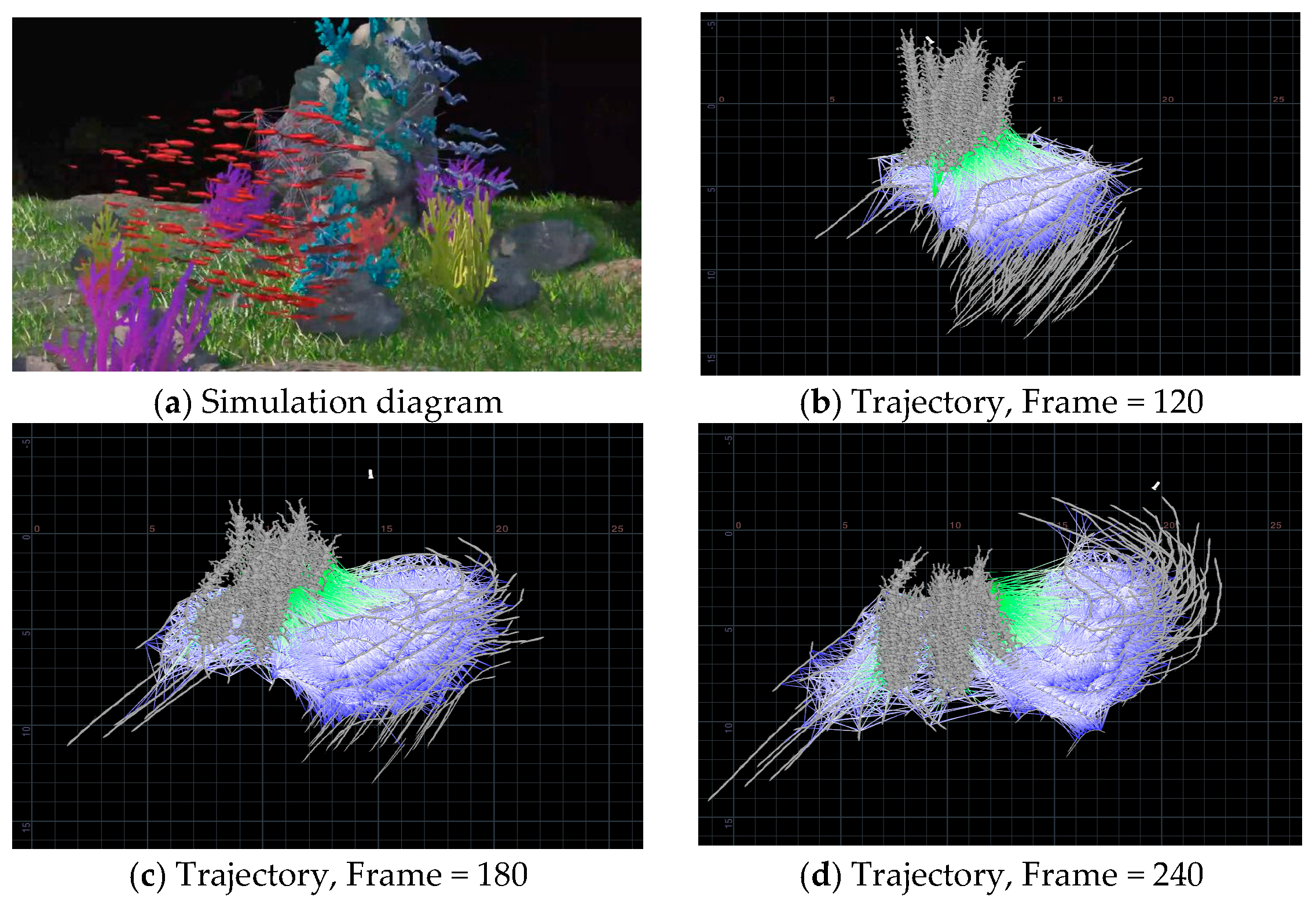

5.3. Fish Crowd Activity

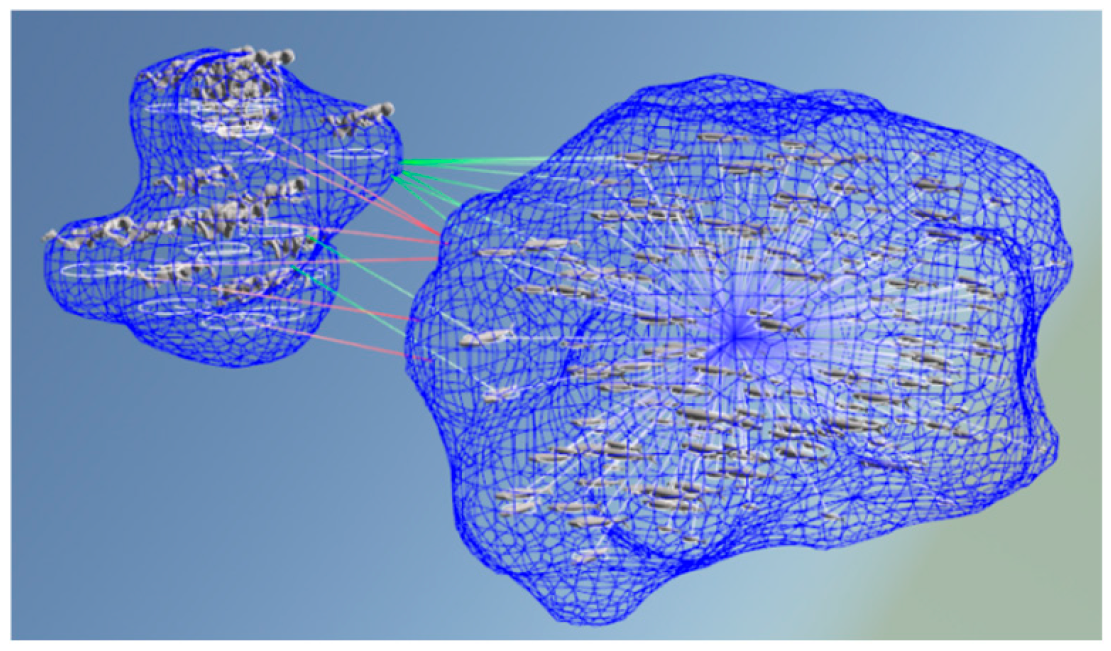

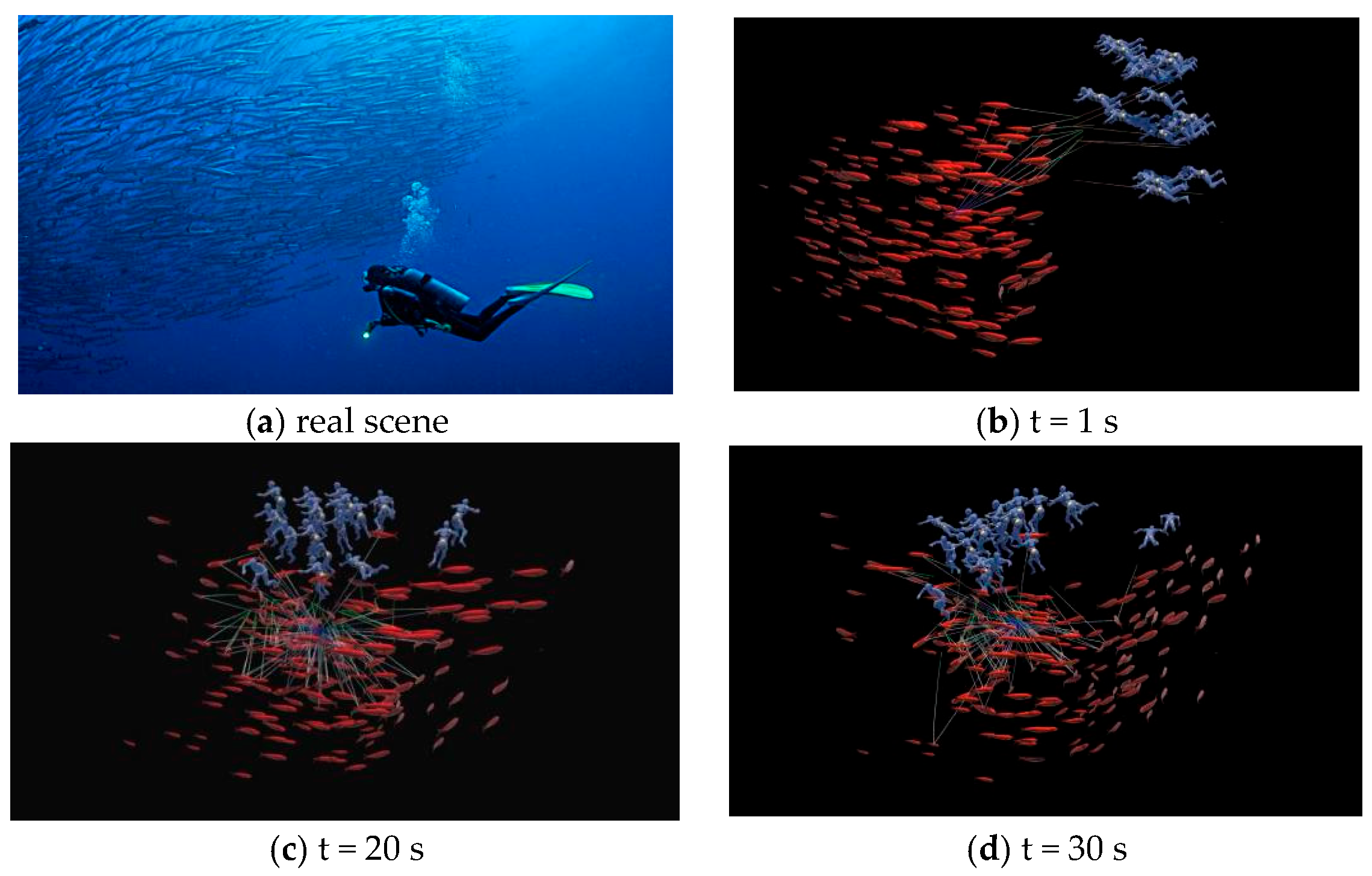

5.4. Underwater Fishing

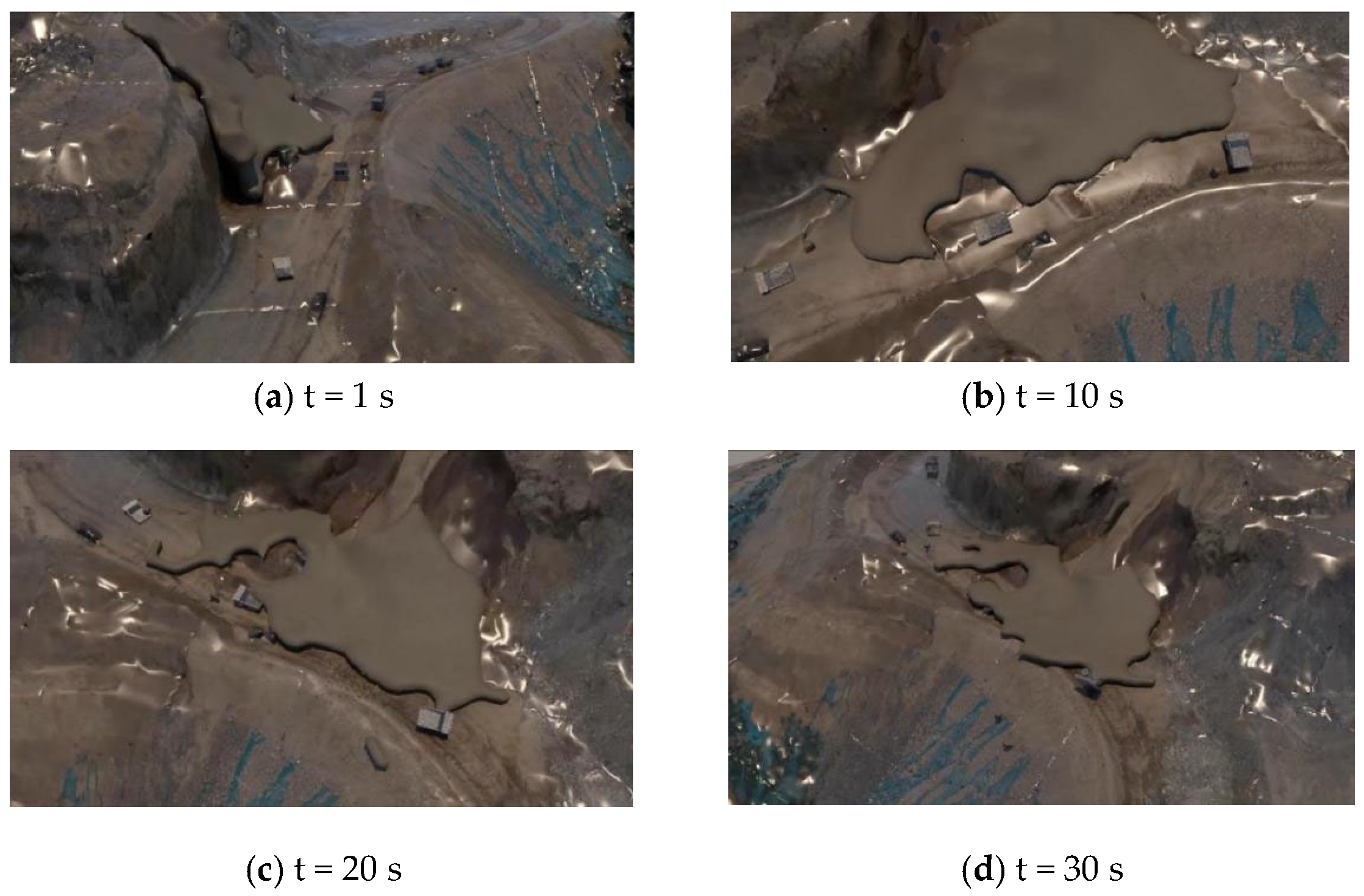

5.5. Mine Field Landslide

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dufour, O.; Dang, H.T.; Cordes, J.; Korbmacher, R.; Chraibi, M.; Gaudou, B.; Nicolas, A.; Tordeux, A. Dense Crowd Dynamics and Pedestrian Trajectories: A Multiscale Field Dataset from the Festival of Lights in Lyon. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Liu, T.; Liu, Z. Diverse Motions and Responses in Crowd Simulation. Comput. Animat. Virtual Worlds 2024, 35, e70002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.W. Steering behaviors for autonomous characters. In Proceedings of the Game Developers Conference, San Jose, CA, USA, 15–19 March 1999; Volume 1999, pp. 763–782. [Google Scholar]

- Helbing, D.; Molnar, P. Social force model for pedestrian dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 1995, 51, 4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Berg, J.; Lin, M.; Manocha, D. Reciprocal velocity obstacles for real-time multi-agent navigation. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Pasadena, CA, USA, 19–23 May 2008; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 1928–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondřej, J.; Pettré, J.; Olivier, A.H.; Donikian, S. A synthetic-vision based steering approach for crowd simulation. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2010, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Haworth, B.; Berseth, G.; Pavlovic, V.; Faloutsos, P.; Kapadia, M. Heterogeneous crowd simulation using parametric reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2021, 29, 2036–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funge, J.; Tu, X.; Terzopoulos, D. Cognitive modeling: Knowledge, reasoning and planning for intelligent characters. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 8–13 August 1999; pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Terzopoulos, D. Autonomous pedestrians. In Proceedings of the 2005 ACM SIGGRAPH/Eurographics Symposium on Computer Animation, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 29–31 July 2005; pp. 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Van Den Berg, J.; Curtis, S.; Lin, M.C.; Manocha, D. Directing crowd simulations using navigation fields. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2010, 17, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loscos, C.; Marchal, D.; Meyer, A. Intuitive crowd behavior in dense urban environments using local laws. In Proceedings of the Theory and Practice of Computer Graphics, Birmingham, UK, 5 June 2003; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 122–129. [Google Scholar]

- Best, A.; Narang, S.; Curtis, S.; Manocha, D. DenseSense: Interactive Crowd Simulation using Density-Dependent Filters. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Computer Animation, Copenhagen, Denmark, 21–23 July 2014; pp. 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heïgeas, L.; Luciani, A.; Thollot, J.; Castagné, N. A physically-based particle model of emergent crowd behaviors. arXiv 2010, arXiv:1005.4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golas, A.; Narain, R.; Lin, M. Hybrid long-range collision avoidance for crowd simulation. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGGRAPH Symposium on Interactive 3D Graphics and Games, Orlando, FL, USA, 21–23 March 2013; pp. 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirvani, M.; Kesserwani, G.; Richmond, P. Agent-based simulator of dynamic flood-people interactions. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2021, 14, e12695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirvani, M.; Kesserwani, G.; Richmond, P. Agent-based modelling of pedestrian responses during flood emergency: Mobility behavioural rules and implications for flood risk analysis. J. Hydroinform. 2020, 22, 1078–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, R.R.; Hughes, R.L. Mathematical modelling of a mediaeval battle: The battle of Agincourt, 1415. Math. Comput. Simul. 2004, 64, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treuille, A.; Cooper, S.; Popović, Z. Continuum crowds. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2006, 25, 1160–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narain, R.; Golas, A.; Curtis, S.; Lin, M.C. Aggregate dynamics for dense crowd simulation. In ACM SIGGRAPH Asia 2009 Papers; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Luo, G.; Tong, Y.; Jin, X.; Deng, Z. A linear wave propagation-based simulation model for dense and polarized crowds. Comput. Animat. Virtual Worlds 2021, 32, e1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Toll, W.; Chatagnon, T.; Braga, C.; Solenthaler, B.; Pettré, J. SPH crowds: Agent-based crowd simulation up to extreme densities using fluid dynamics. Comput. Graph. 2021, 98, 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Freris, N.M. Multi-scale graph neural network for physics-informed fluid simulation. Vis. Comput. 2025, 41, 1171–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, H.; Takebayashi, H.; Fujita, M. Assessment of debris flow risk according to damage type. J. Disaster Sci. Manag. 2025, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, A.; Yasufuku, K. Evaluation of Tsunami Evacuation Plans for an Underground Mall Using an Agent-Based Model. J. Disaster Res. 2024, 19, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishino, K.; Ishida, T. Earthquake Virtual Reality Simulation System for Appropriate Evacuation Actions. In International Conference on P2P, Parallel, Grid, Cloud and Internet Computing; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Yang, S.; Kim, S. The smoke control system to improve the possibility of evacuation from fire disasters in high-rise buildings. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2025, 59, 103269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borralho, T.M.O.; Rodrigues, J.P.C.; dos Santos, C.C. Evacuation of Lisbon’s Baixa-Chiado subway station in case of fire. Archit. Struct. Constr. 2025, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.; Swami, K.; Gaddam, H.K. Simulation Based Passengers Emergency Evacuation Study for a Double Decker Train Coach. Transp. Res. Procedia 2025, 82, 1054–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, G.; Cantatore, E.; Fatiguso, F.; Quagliarini, E. User Behaviour in Terrorist Acts to Model the Evacuation in Outdoor Open Areas. In Terrorist Risk in Urban Outdoor Built Environment: Measuring and Mitigating via Behavioural Design Approach; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Ye, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, Q. Crowd evacuation simulation in flowing fluids. Comput. Animat. Virtual Worlds 2023, 34, e2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Y. Research on Microscopic Simulation Model of Crowd Dispersion. Doctoral Dissertation, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Demyen, D.; Buro, M. Efficient triangulation-based pathfinding. AAAI 2006, 6, 942–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, L. Human Dimensions of Chinese Adults Standard and Its Application. China Qual. Stand. Rev. 1994, 6, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, J. Multi-Agent System Simulation and Evaluation. Ph.D. Dissertation, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y. Study on the Model of Dense Population Flow and Evacuation Guidance Under Environmental Constraints. Ph.D. Dissertation, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Feature Model Name | Reynolds’ Boids Strategies | Reynolds’ Steering Behavior Strategies | The Equivalent Strategies of This Paper |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drive mode | Agent-based | Agent-based | Hybrid SPH and Agent |

| Key distinction | It focuses on the self-organizing (emergent) behaviors of the cluster. | Focus on individual navigation. | It aims to solve the self-organizing (emergent) behaviors of mixed clusters and the multi-level spatial navigation of individual. |

| Advantage | Easy to implement and the cluster behavior is realistic. | Supports 2D/3D models with plug-in behavior modules. | Individual strategies and group strategies are integrated. |

| Limitation | Cannot handle complex obstacles. | Single drive mode. | High computational overhead. |

| Application scenarios | Suitable for single cluster, such as bird or fish animations. | Suitable for simulating realistic movements of autonomous characters in game AI. | Suitable for mixed clusters and various natural environments (e.g., landslide, undersea, urban blocks, tunnels, multi-floor indoor spaces). |

| Data Operation | Points | Polygons | Vertices |

|---|---|---|---|

| Original data | 4,671,744 | 7,805,565 | 23,416,695 |

| Cropped data | 1,577,905 | 2,967,147 | 9,287,655 |

| After reduction | 142,857 | 296,307 | 980,027 |

| Scene | Type and Condition | Size (Num) | Scene Scale and Realism | Time Costs (Seconds/Frame) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crowd-1 | Crowd, virtual Scene | 8–148 | simple, low | [0.001, 0.005] |

| Crowd-2 | Crowd, virtual Scene | 100 | simple, low | [0.015, 0.029] |

| Traffic-1 | Crowd/traffic, virtual Scene | 30/35 | medium, medium | [0.033, 0.038] |

| Traffic-2 | People/bicycle/car, virtual Scene | 25/15/40 | medium, medium | [0.029, 0.034] |

| Ours | Crowd, real-scene 3D Variable-rotation Method with Strategies One and Two | 50~500 | complex, high | [0.026, 0.035] |

| Method | Dataset | Pathfinding Algorithm | TBR | BE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFM [4] | Real scene 3D data | Shortest path | [0.5%, 5%], non-linear | [7500,8500], non-linear |

| SPHM [30] | Real scene 3D data | Minimal-rotation | [0.5%, 5%], non-linear | [7500,8500], non-linear |

| CAM [35] | Real scene 3D data | Shortest path | [0.5%, 5%], non-linear | [7500,8500], non-linear |

| LBM [35] | [Images in real life, UCF] | Shortest path | [0.5%, 5%], non-linear | [7250,8200], non-linear |

| This article | Real scene 3D data | Variable-rotation | [1%, 25%], non-linear | [7500,8500], non-linear |

| Method | Agents (Number) | Obstacles (Number) | Egress Time (Second) | External Condition | Emergent Behavioral Condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAM [35] | 100 | [1,2] | [10,25] | 2D space, static environment, Shortest path | The evacuation time and density are negatively correlated (non-linear), and the steep slope inflection points exist at both ends of the evacuation relation curve. |

| CAM [35] | 500 | [1,2] | [25,30] | ||

| ACPM [25] | 100 | [1,2] | [10,25] | The evacuation time is negatively correlated (non-linear) with the number of static obstacles. | |

| ACPM [25] | 500 | [1,2] | [25,30] | ||

| APFM [31] | 100 | 500 | [20,40] | The evacuation time is positively correlated with the number and width of exits (non-linear), and the steep slope inflection points exist at both ends of the evacuation relation curve. | |

| APFM [31] | 500 | 500 | [80,120] | ||

| This article | 100 | 100 | [30,40] | 3D space, dynamic environment. Variable-rotation, Spatial-extrusion, Strategy One to Two | There is a strong correlation between evacuation time and external emergencies. The variable-rotation method can effectively adapt to changes in the external environment. |

| This article | 500 | 500 | [110,200] |

| Method | Number of Particles | Time Costs (Seconds/Frame) |

|---|---|---|

| BIM [34] | 100 | 0.032 |

| BIM [34] | 500 | 0.038 |

| This article: strategy three | 100 | 0.025 |

| This article: strategy three | 500 | 0.028 |

| This article: strategy four | 100 | 0.029 |

| This article: strategy four | 500 | 0.032 |

| Result Model Name | Reynolds’ Boids Strategies | Reynolds’ Steering Behaviors Strategies | The Equivalent Strategies of This Paper |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulated emergent behaviors of clusters | Separation | Inherit Boids model | Strategy One, Two |

| Alignment | Strategy Three | ||

| Cohesion | Strategy Five | ||

| / | Seek | Strategy Four | |

| Flee | Strategy Four | ||

| Arrive | Strategy Three | ||

| Wander | Strategy Three | ||

| Pursuit/Evade | Strategy Four, Five | ||

| Obstacle Avoidance | Strategy One, Two, Five | ||

| Does this mode support our Strategy Six? | No | No | Yes |

| Time cost (100 particles) | 0.029 | 0.038 | 0.028 |

| Time cost (500 particles) | 0.033 | 0.042 | 0.032 |

| Method | Particle Size | Scene Scale | Scene Realism | BE | TBR | Time Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAS [15], Multi-agent and Shortest path | 100 | 50,000 level | low | [0.5%, 5%], non-linear | [7500,8500], non-linear | 0.033 |

| 500 | 100,000 level | middle | [0.5%, 5%], non-linear | [7500,9000], non-linear | 0.058 | |

| 500 | 150,000 level | high | [0.5%, 5%], non-linear | [000,10,7500], non-linear | 0.092 | |

| This article, Multi-type particles fusion and Strategy six. | 100 | 50,000 level | low | [1%, 25%], non-linear | [7500,8500], non-linear | 0.021 |

| 500 | 100,000 level | middle | [1%, 30%], non-linear | [7500,9000], non-linear | 0.043 | |

| 500 | 150,000 level | high | [1%, 30%], non-linear | [000,10,7500], non-linear | 0.087 | |

| Unit (particle size: number, scene scale: number of vertices, time cost: seconds/frame) | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zou, X.; Ye, Y.; Feng, T.; Zhu, Z. A Crowd Simulation Framework in Special Natural Environments. Information 2026, 17, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010049

Zou X, Ye Y, Feng T, Zhu Z. A Crowd Simulation Framework in Special Natural Environments. Information. 2026; 17(1):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010049

Chicago/Turabian StyleZou, Xunjin, Yunqing Ye, Tianxia Feng, and Zhenming Zhu. 2026. "A Crowd Simulation Framework in Special Natural Environments" Information 17, no. 1: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010049

APA StyleZou, X., Ye, Y., Feng, T., & Zhu, Z. (2026). A Crowd Simulation Framework in Special Natural Environments. Information, 17(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010049