Leveraging Artificial Intelligence for Sustainable Tutoring and Dropout Prevention in Higher Education: A Scoping Review on Digital Transformation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Contextualization

1.2. Conceptual Framework for AI in Higher Education

1.2.1. AI Techniques

1.2.2. Predictive Variables

1.2.3. Educational Contexts

1.3. Justification

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PCC Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Search Equation and Databases

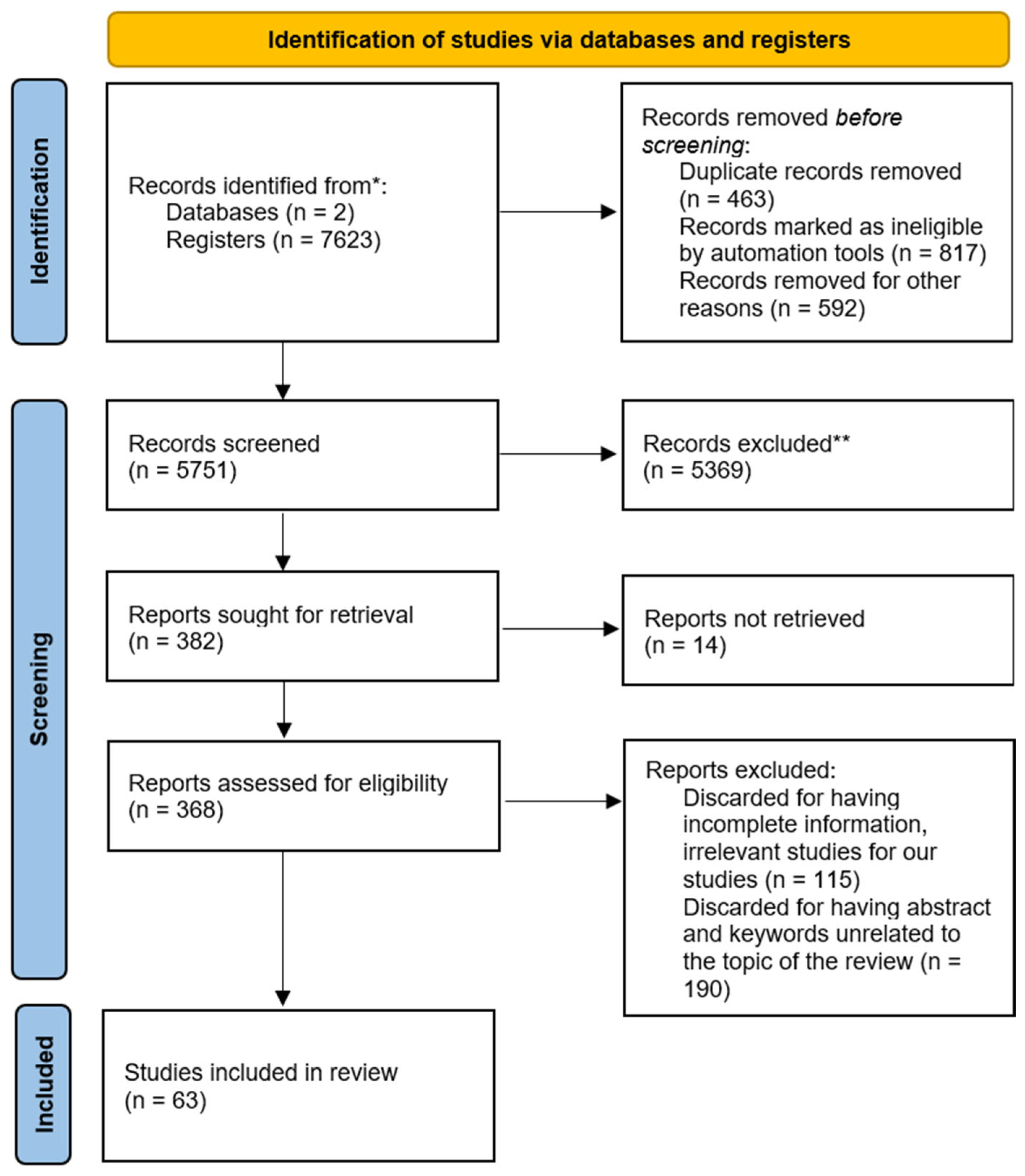

2.4. Article Extraction Using PRISMA

- Lack of empirical validation (n = 74): Studies that only presented theoretical debates, conceptual frameworks, or editorials without implemented models.

- Irrelevant focus (n = 63): Articles that addressed educational contexts unrelated to higher education, such as primary and secondary education and business training; in addition, unrelated topics, such as data science in general, with no application to academic performance.

- Methodological limitations (n = 32): Studies that did not apply predictive models, lacked sufficient methodological description, or provided incomplete data.

- Other criteria (n = 21): Inaccessible data, duplicate records not detected in previous phases, and even articles that did not conform to the PCC framework despite their initial inclusion.

3. Results

- AI techniques applied;

- Variables used;

- Educational context/level;

- Type of outcome addressed;

- Reported benefits or limitations.

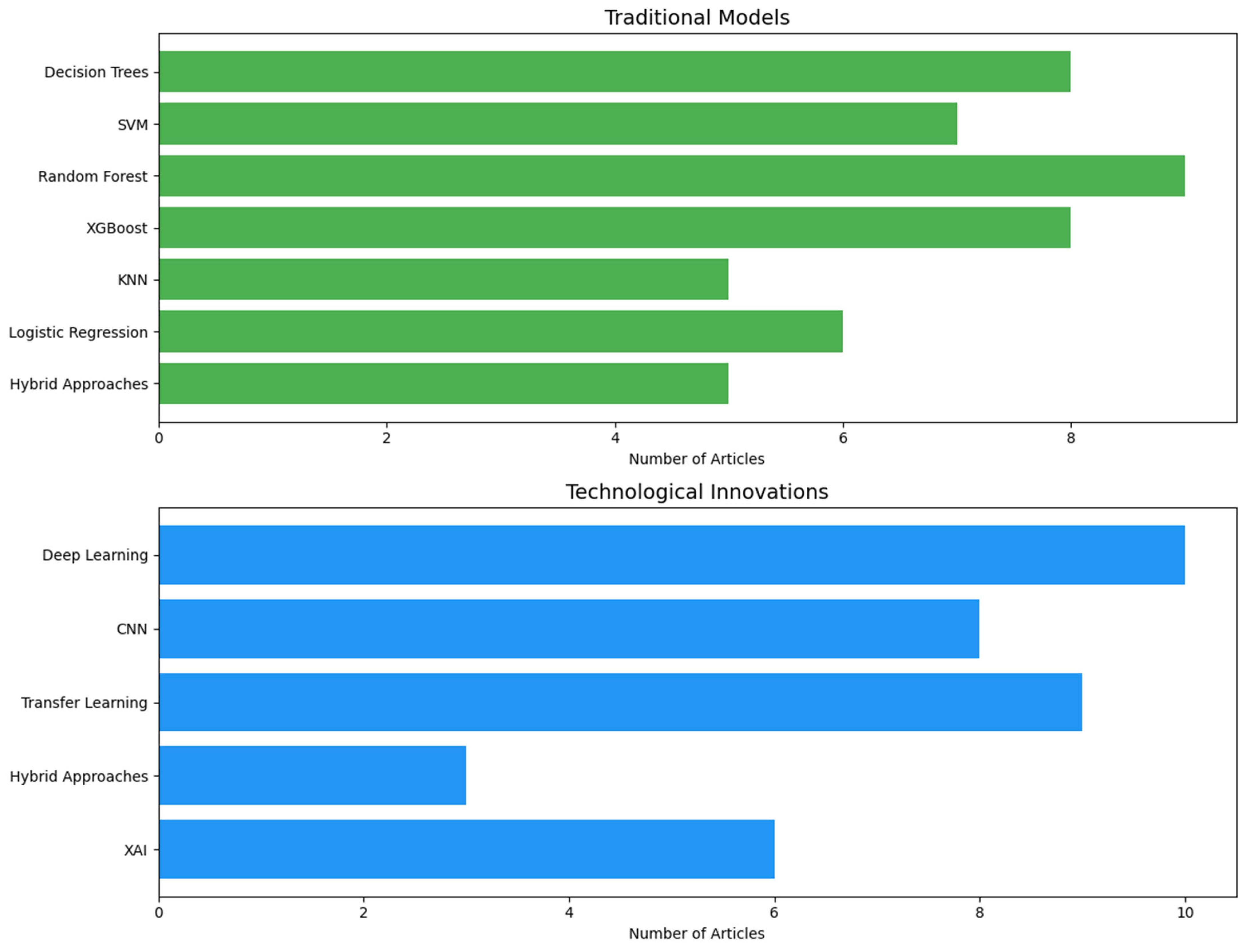

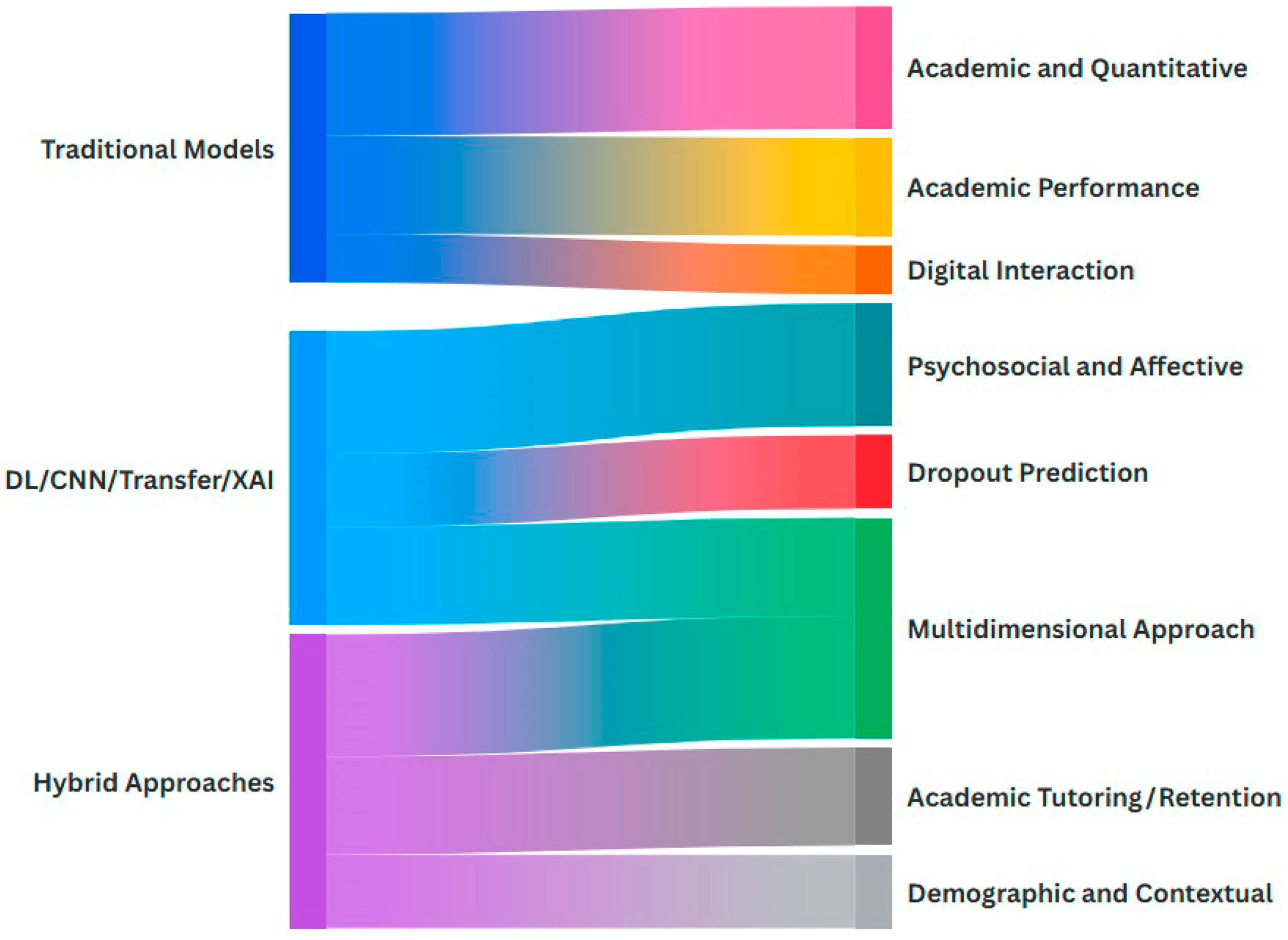

3.1. AI Techniques Applied

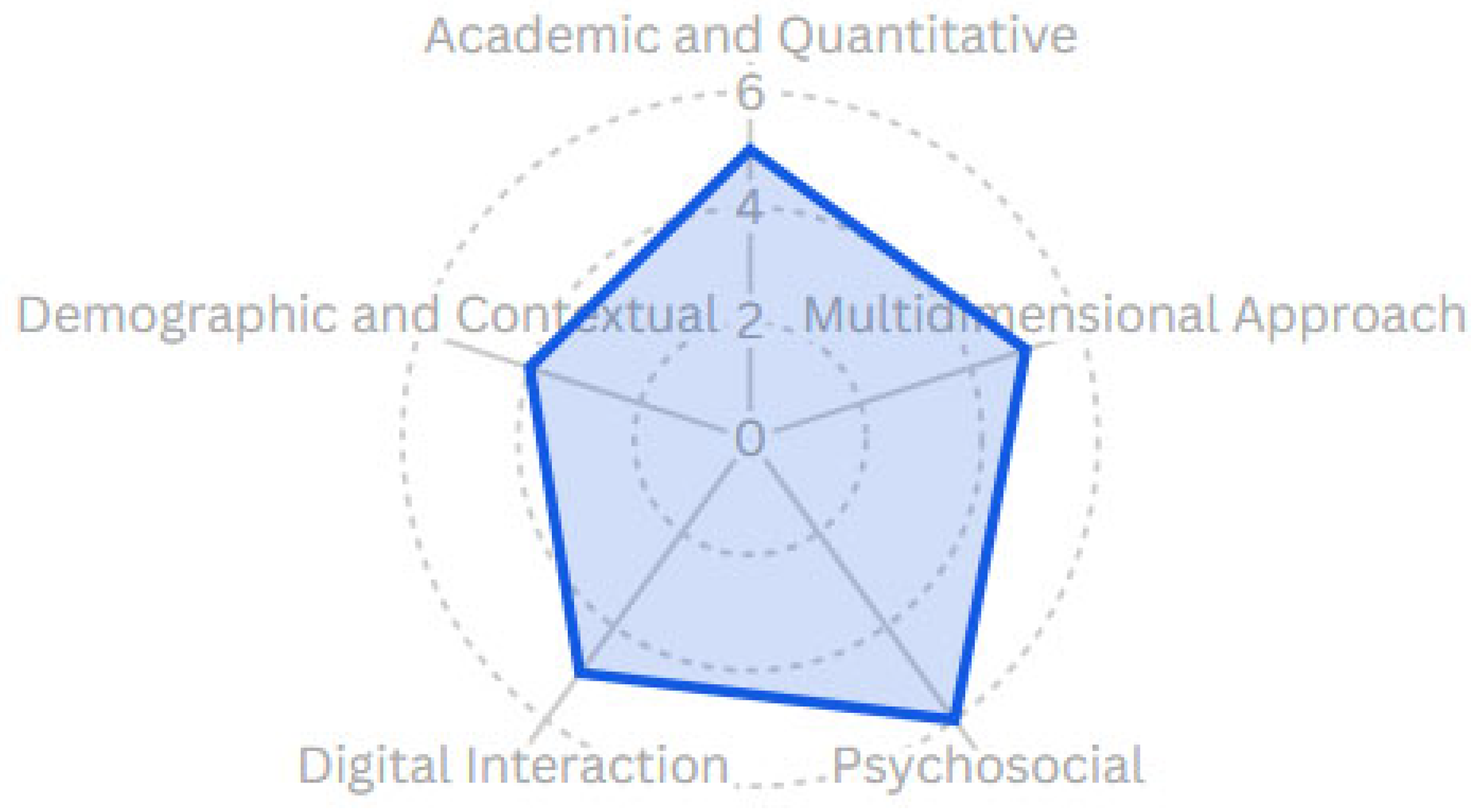

3.2. Variables Used

| Variable Type | Description | Examples | Articles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academic and Quantitative | Traditional variables related to academic performance, easily retrieved from institutional systems. | GPA, number of courses passed/failed, attendance, assignments, midterms/final exams. | [21,22,23,24,39] |

| Digital Interaction | Variables from student interaction with learning platforms (LMS), especially in remote learning. | Variables from student interaction with learning platforms (LMS), especially in remote learning. | [40,41,42,44,45] |

| Psychosocial and Affective | Variables related to emotional well-being, motivation, and psychological traits. | Academic motivation, anxiety, self-efficacy, personality profile, self-reported emotions, and general psychological state. | [46,47,48,49,50,51] |

| Demographic and Contextual | Variables describing sociodemographic background or environmental conditions. | Age, gender, socioeconomic level, residence, access to technology, institution type (whether public or private). | [43,49,52,53] |

| Multidimensional Approach | Integration of various variables to create more complex and accurate models. | Combination of academic, emotional, behavioral, and demographic variables. | [27,54,55,56,57] |

3.3. Educational Context/Level

3.4. Outcomes Addressed

3.5. Benefits and Limitations Reported

4. Discussion

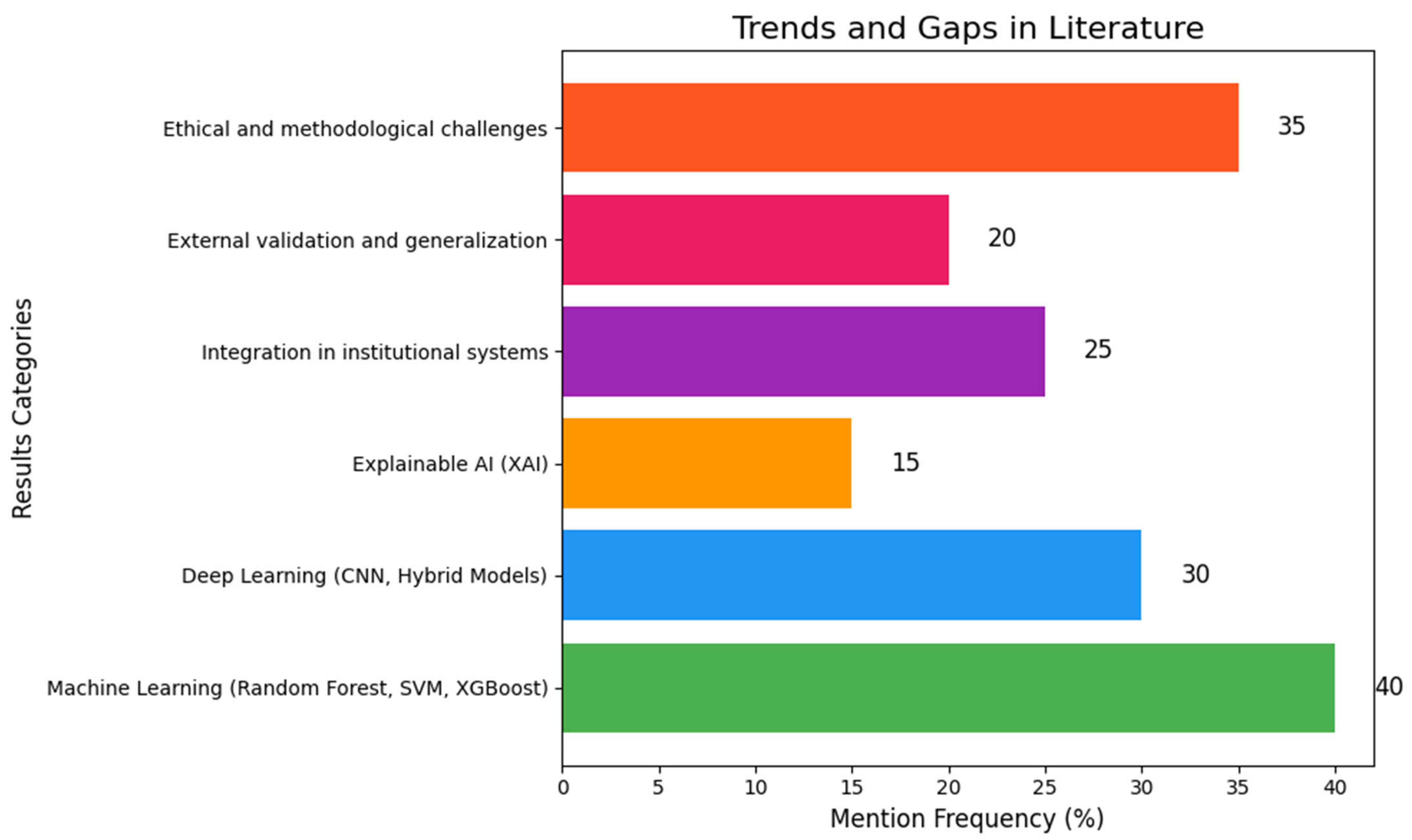

4.1. Identified Trends

4.2. Identified Gaps in the Literature

4.3. Practical Barriers and Comparative Analysis of AI Techniques

4.4. Limitations of the Scoping Review

5. Conclusions

Future Research Agenda

- AI techniques (from classical ML to advanced DL and XAI);

- Predictive variables (academic, behavioral, psychosocial, and contextual);

- Educational contexts (virtual, hybrid, and face-to-face with technological mediation).

- External validation of predictive models across diverse cultural and institutional contexts to ensure generalizability.

- Systematic study of ethical and governance frameworks to guarantee the responsible and equitable adoption of AI.

- Integration of multimodal and affective data (academic, behavioral, emotional, and contextual) to enhance personalization and inclusivity.

- Comparative analyses that evaluate trade-offs between interpretability, accuracy, and computational costs to inform decision-making in resource-constrained institutions.

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alenezi, M. Digital Learning and Digital Institution in Higher Education. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevlin, M.; Banks, J. Inclusion at a crossroads: Dismantling ireland’s system of special education. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, E.F.; Andaluz, V.H. Autonomous Control of an Electric Vehicle by Computer Vision Applied to the Teaching–Learning Process. In Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, E.F.; Morales, E.E.; Florez, C.C.; Toasa, R.M. Development of an Augmented Reality System to Support the Teaching-Learning Process in Automotive Mechatronics. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreyra, M.M.; Avitabile, C.; Álvarez, J.B.; Paz, F.H.; Urzúa, S. At a Crossroads: Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Revisión del Panorama Educativo de América Latina y el Caribe: Avances y Desafíos; UNESCO: Santiago, Chile, 2022; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000381748 (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Acevedo, F. Concepts and measurement of dropout in higher education: A critical perspective from latin America. Issues Educ. Res. 2021, 31, 661–678. [Google Scholar]

- Da Re, L.; Bonelli, R.; Gerosa, A. Formative Tutoring: A Program for the Empowerment of Engineering Students. IEEE Trans. Educ. 2023, 66, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oqaidi, K.; Aouhassi, S.; Mansouri, K. Towards a Students’ Dropout Prediction Model in Higher Education Institutions Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2022, 17, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, T.; Sun, C.; Wu, Z.; Yang, J.; Wang, J. Deep Neural Network-Based Prediction and Early Warning of Student Grades and Recommendations for Similar Learning Approaches. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mughairi, H.; Bhaskar, P. Exploring the factors affecting the adoption AI techniques in higher education: Insights from teachers’ perspectives on ChatGPT. J. Res. Innov. Teach. Learn. 2024. Epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén-Gámez, F.D.; Mayorga-Fernández, M.J. Identification of variables that predict teachers’ attitudes toward ict in higher education for teaching and research: A study with regression. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Pilco, S.Z.; Yang, Y. Artificial intelligence applications in Latin American higher education: A systematic review. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2022, 19, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge-Vázquez, J.; Alonso, S.L.N.; Saltos, W.R.F.; Mendoza, S.P. Assessment of digital competencies of university faculty and their conditioning factors: Case study in a technological adoption context. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.; Mclnerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020version). In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, C.; Franchi, T.; Mathew, G.; Kerwan, A.; Nicola, M.; Griffin, M.; Agha, M.; Agha, R. PRISMA 2020 statement: What's new and the importance of reporting guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilić, M.; Keković, G.; Mikić, V.; Mangaroska, K.; Kopanja, L.; Vesin, B. Predicting Student Performance in a Programming Tutoring System Using AI and Filtering Techniques. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2024, 17, 1891–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Mendoza, S.; Guevara, C.; Mayorga-Albán, A.; Fernández-Escobar, J. Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education: A Predictive Model for Academic Performance. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wei, J.; Che, H. Student Performance Prediction in Mathematics Course Based on the Random Forest and Simulated Annealing. Sci. Program. 2022, 2022, 9340434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yağcı, M. Educational data mining: Prediction of students’ academic performance using machine learning algorithms. Smart Learn. Environ. 2022, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, G.; Alghazo, R.; Pilotti, M.A.E.; Ben Brahim, G. Identifying “At-Risk” Students: An AI-based Prediction Approach. Int. J. Comput. Digit. Syst. 2022, 11, 1051–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekeroglu, B.; Dimililer, K.; Tuncal, K. Student performance prediction and classification using machine learning algorithms. In Proceedings of the CEIT 2019: 2019 8th International Conference on Educational and Information Technology, Cambridge, UK, 2–4 March 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Nucamendi, A.; Noguez, J.; Neri, L.; Robledo-Rella, V.; García-Castelán, R.M.G. Predictive analytics study to determine undergraduate students at risk of dropout. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1244686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ka’BI, A. Proposed artificial intelligence algorithm and deep learning techniques for development of higher education. Int. J. Intell. Netw. 2023, 4, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, J.A.I.S.; Chakravarthy, N.S.K.; Asirvatham, D.; Marjani, M.; Shafiq, D.A.; Nidamanuri, S. A Hybrid Deep Learning Model to Predict High-Risk Students in Virtual Learning Environments. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 103687–103703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazil, M.; Rísquez, A.; Halpin, C. A Novel Deep Learning Model for Student Performance Prediction Using Engagement Data. J. Learn. Anal. 2024, 11, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, S.V.K.R.; Abarna, K.T.M. Enhancing Student Academic Performance Forecasting in Technical Education: A Cutting-edge Hybrid Fusion Method. Int. J. Electron. Commun. Eng. 2024, 11, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Wu, H.; Zhang, T.; Qiu, K.; Chen, T.; Qin, H. Multisource-domain regression transfer learning framework for predicting student academic performance considering balanced similarity. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 156, 111202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goran, R.; Jovanovic, L.; Bacanin, N.; Stanković, M.S.; Simic, V.; Antonijevic, M.; Zivkovic, M. Identifying and Understanding Student Dropouts Using Metaheuristic Optimized Classifiers and Explainable Artificial Intelligence Techniques. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 122377–122400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressane, A.; Spalding, M.; Zwirn, D.; Loureiro, A.I.S.; Bankole, A.O.; Negri, R.G.; Junior, I.d.B.; Formiga, J.K.S.; Medeiros, L.C.d.C.; Bortolozo, L.A.P.; et al. Fuzzy Artificial Intelligence—Based Model Proposal to Forecast Student Performance and Retention Risk in Engineering Education: An Alternative for Handling with Small Data. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lhafra, F.Z.; Abdoun, O. Integration of evolutionary algorithm in an agent-oriented approach for an adaptive e-learning. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2023, 13, 1964–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanellati, A.; Zingaro, S.P.; Gabbrielli, M. Balancing Performance and Explainability in Academic Dropout Prediction. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2024, 17, 2086–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, B.; Keller. Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Academic Performance Prediction. An Experimental Study on the Impact of Accuracy and Simplicity of Decision Trees on Causability and Fairness Perceptions. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3–6 June 2024; pp. 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, M.; Molontay, R. Interpretable Dropout Prediction: Towards XAI-Based Personalized Intervention. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2024, 34, 274–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwarthan, S.; Aslam, N.; Khan, I.U. An Explainable Model for Identifying At-Risk Student at Higher Education. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 107649–107668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raji, N.R.; Kumar, R.M.S.; Biji, C.L. Explainable Machine Learning Prediction for the Academic Performance of Deaf Scholars. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 23595–23612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.; Uddin, M.I.; Khan, E.; Alharithi, F.S.; Amin, S.; Alzahrani, A.A. Earliest Possible Global and Local Interpretation of Students’ Performance in Virtual Learning Environment by Leveraging Explainable AI. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 129843–129864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badal, Y.T.; Sungkur, R.K. Predictive modelling and analytics of students’ grades using machine learning algorithms. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 3027–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlache, H.A.M.; Ger, P.M.; Valentín, L.D.l.F. Towards the Grade’s Prediction. A Study of Different Machine Learning Approaches to Predict Grades from Student Interaction Data. Int. J. Interact. Multimedia Artif. Intell. 2022, 7, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borna, M.-R.; Saadat, H.; Hojjati, A.T.; Akbari, E. Analyzing click data with AI: Implications for student performance prediction and learning assessment. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1421479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahafdah, R.; Bouallegue, S.; Bouallegue, R. Enhancing e-learning through AI: Advanced techniques for optimizing student performance. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, K.T.; Caparachin, M.A.; Canturin, F.O.A.; Ninahuaman, J.U.; Avila, M.F.I.; Cangalaya, R.C. Artificial Intelligence Model for the Improvement of the Quality of Education at the National University of Central Peru, Huancayo 2024. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Symposium on Accreditation of Engineering and Computing Education (ICACIT), Bogota, Colombia, 3–4 October 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fan, S.; Xu, S.; Sajjanhar, A.; Yeom, S.; Wei, Y. Predicting Student Performance Using Clickstream Data and Machine Learning. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadneh, N.N.; Atawneh, S.; Khan, W.A.; Almejalli, K.A.; Alhomoud, A. Using Artificial Intelligence to Predict Students’ Academic Performance in Blended Learning. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharthi, H. Predicting the level of generalized anxiety disorder of the coronavirus pandemic among college age students using artificial intelligence technology. In Proceedings of the 2020 19th Distributed Computing and Applications for Business Engineering and Science, DCABES 2020, Xuzhou, China, 16–19 October 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, A.F.; Fernandes, O., Jr.; Liberal, S.P.; Pires, A.J.L.; Lage, L.A.; Grichtchouk, O.; Cardoso, A.R.; de Oliveira, L.; Pereira, M.G.; Lovisi, G.M.; et al. Academic-related stressors predict depressive symptoms in graduate students: A machine learning study. Behav. Brain Res. 2025, 478, 115328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, H. Psychological Analysis Using Artificial Intelligence Algorithms of Online Course Learning of College Students During COVID-19. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 16, 3996–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordbar, S.; Mirzaei, S.; Bahmaei, J.; Atashbahar, O.; Yusefi, A.R. Predicting students’ academic performance based on academic identity, academic excitement, and academic enthusiasm: Evidence from a cross-sectional study in a developing country. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhong, Z.; Mao, W.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z. A New Machine-Learning-Driven Grade-Point Average Prediction Approach for College Students Incorporating Psychological Evaluations in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Electronics 2024, 13, 1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.A.; Murtaza, F.; Haq, M.E.U.; Yasin, A.; Azam, M.A. A Human-Centered Approach to Academic Performance Prediction Using Personality Factors in Educational AI. Information 2024, 15, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokhan, A.; Chand, A.A.; Singh, V.; Mamun, K.A. Increased Digital Resource Consumption in Higher Educational Institutions and the Artificial Intelligence Role in Informing Decisions Related to Student Performance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arqawi, S.M.; Zitawi, E.A.; Rabaya, A.H.; Abunasser, B.S.; Abu-Naser, S.S. Predicting University Student Retention using Artificial Intelligence. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2022, 13, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhou, D.; Wang, H.; Chen, D.; Yu, L. Enhancing Student Academic Success Prediction Through Ensemble Learning and Image-Based Behavioral Data Transformation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.Y.Q.; Chang, J.W.; Yang, A.C.M.; Ogata, H.; Li, S.T.; Yen, R.X.; Yang, S.J.H. Personalized Intervention based on the Early Prediction of At-risk Students to Improve Their Learning Performance. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2023, 26, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.; Habib, A.; Ashraf, J.; Mussadiq, S.; Raza, A.A.; Abid, M.; Bashir, M.; Khan, S.U. Predicting at-Risk Students at Different Percentages of Course Length for Early Intervention Using Machine Learning Models. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 7519–7539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sun, Z.; Chen, Y. Effects of higher education institutes’ artificial intelligence capability on students’ self-efficacy, creativity and learning performance. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 4919–4939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemachandran, K.; Verma, P.; Pareek, P.; Arora, N.; Kumar, K.V.R.; Ahanger, T.A.; Pise, A.A.; Ratna, R. Artificial Intelligence: A Universal Virtual Tool to Augment Tutoring in Higher Education. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 1410448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, K.R.; Abarna, K.T.M.; Vairachilai, S. Open Issues, Research Challenges, and Survey on Education Sector in India and Exploring Machine Learning Algorithm to Mitigate These Challenges. Int. J. Recent Innov. Trends Comput. Commun. 2023, 11, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, F.; Wu, M.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, L.; Jiao, P. Integration of artificial intelligence performance prediction and learning analytics to improve student learning in online engineering course. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2023, 20, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, P.; Ouyang, F.; Zhang, Q.; Alavi, A.H. Artificial intelligence-enabled prediction model of student academic performance in online engineering education. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 6321–6344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarzuki, H.F.; Abu Samah, K.A.F.; Rahim, S.K.N.A.; Ibrahim, S.; Riza, L.S. Enhancement of Prediction Model for Students’ Performance in Intelligent Tutoring System. J. Artif. Intell. Technol. 2024, 4, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almiman, A.; Ben Othman, M.T. Predictive Analysis of Computer Science Student Performance: An ACM2013 Knowledge Area Approach. Ingénierie Systèmes D’information 2024, 29, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, M.; Sayed, N.; Singh, J.; Shafi, J.; Khan, S.; Ali, F. AI student success predictor: Enhancing personalized learning in campus management systems. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 158, 108301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzavela, V.; Alepis, E. Decision tree learning through a Predictive Model for Student Academic Performance in Intelligent M-Learning environments. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2021, 2, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooda, M.; Rana, C.; Dahiya, O.; Rizwan, A.; Hossain, S.; Kumar, V. Artificial Intelligence for Assessment and Feedback to Enhance Student Success in Higher Education. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 5215722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, K.N.A. Intelligent tutoring systems’ measurement and prediction of students’ performance using predictive function. Int. J. Emerg. Trends Eng. Res. 2020, 8, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramo, R.M.; Alshaher, A.A.; Al-Fakhry, N.A. The Effect of Using Artificial Intelligence on Learning Performance in Iraq: The Dual Factor Theory. Perspective 2022, 27, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barik, L.; Barukab, O.; Ahmed, A.A. Employing artificial intelligence techniques for student performance evaluation and teaching strategy enrichment: An innovative approach. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2020, 7, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Ahmad, A.R.; Jabeur, N.; Mahdi, M.N. An artificial intelligence approach to monitor student performance and devise preventive measures. Smart Learn. Environ. 2021, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albreiki, B.; Habuza, T.; Zaki, N. Framework for automatically suggesting remedial actions to help students at risk based on explainable ML and rule-based models. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2022, 19, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, A.; Lu, C.H.; Hoang, L.X.; Nguyen, P.M. The Effect of Investing into Distribution Information and Communication Technologies on Banking Performance the Empirical Evidence from an Emerging Country. J. Distrib. Sci. 2022, 20, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, J.F.; Garcia-Hernandez, R.; Llama, M.A.; Santibañez, V. A Comparative Study of Swarm Intelligence Metaheuristics in UKF-Based Neural Training Applied to the Identification and Control of Robotic Manipulator. Algorithms 2023, 16, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, R.A.P.; Flores, S.A.C.; Zuñiga, K.M. Brecha Digital Y Su Impacto En La Educación A Distancia. UNESUM Ciencias. Rev. Científica Multidiscip. 2021, 5, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specific Objective | Review Question | Population (P) | Concept (C) | Context (C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identify the most used artificial intelligence models in e-learning contexts to predict academic performance, the need for tutoring, or the risk of student dropout in higher education. | What algorithms or artificial intelligence techniques have been applied in e-learning or technology-mediated education settings to predict academic performance, the need for tutoring, or dropout among university students? | University students | Predictive AI models (ML, DL, neural networks) | Virtual, hybrid, or technology-mediated higher education |

| Analyze the most frequently used student-related variables in e-learning environments as inputs for academic performance prediction models based on artificial intelligence. | What student variables—including grades, interaction in virtual platforms, participation, and digital study habits—are commonly used as inputs for predictive models in higher education? | University students | Predictive variables in AI models | Higher education is supported by digital platforms |

| Describe the educational contexts (face-to-face, hybrid, or virtual) where artificial intelligence models are implemented for tutoring and academic performance improvement. | In what educational settings (virtual, hybrid, or face-to-face with digital support) have artificial intelligence models been implemented to predict or intervene in tutoring, academic performance, or dropout processes? | University students | Contextual application of educational AI | Technology-mediated or e-learning environments |

| Explore the benefits and reported outcomes following the implementation of artificial intelligence models in improving tutoring, student retention, and personalized learning in virtual environments. | What positive impacts have been documented from the use of artificial intelligence models in academic tutoring, student retention, or personalized learning within e-learning contexts in higher education? | University students | Outcomes and impact of AI models | Digital or virtual higher education |

| Criterion | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Undergraduate or graduate university students | Primary, secondary, or non-formal education students |

| Concept | Use of AI models to predict performance, dropout, or tutoring needs | Studies that do not implement predictive models or only discuss theory without application |

| Context | Higher education environments, virtual, hybrid, or technology-mediated | Studies in corporate contexts, non-university technical education, or school settings |

| Publication type | Original articles with empirical validation (quantitative or mixed) | Systematic reviews, bibliometric studies, editorials, conference papers without data |

| Language | English | Languages other than English |

| Publication period | Years 2019 to 2025 | Publications prior to 2019 |

| Accessibility | Availability of full text | Restricted access or summary available only |

| Thematic relevance | Alignment with the research objectives and questions posed | Topics outside the educational scope or not related to academic prediction |

| Category | Connector | Search Terms |

|---|---|---|

| Population | (“academic performance” OR “student performance” OR “dropout” OR “academic failure” OR “tutoring” OR “academic advising” OR “retention”) | |

| Concept | AND | (“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “neural networks” OR “data mining” OR “learning analytics” OR “predictive model”) |

| Context | AND | (“higher education” OR “university” OR “college” OR “tertiary education” OR “e-learning” OR “online learning” OR “distance education” OR “hybrid education”) |

| Category | Applied AI Techniques | AI Architecture | Hybrid Approaches | Articles | Educational Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Models | Decision trees, SVM, random forest, XGBoost, KNN, logistic regression | Supervised models based on classification and regression | Model ensembles: random forest + XGBoost | [21,22,23,24,39] | Random forest used to predict dropout risk from LMS activity logs and attendance records; logistic regression applied to classify students into performance risk categories based on GPA and exam history. |

| Technological Innovations | DL, CNN, transfer learning, XAI | Deep neural networks, CNNs, recurrent network | DL + XAI, hybrid DL + transfer learning | [20,25,26,27,28,29] | CNN models analyzed time-series learning behaviors (clickstream, session duration) to predict early dropout; transfer learning applied to adapt models across institutions with different student datasets. |

| Hybrid/Bioinspired Approaches | Genetic algorithms, evolutionary optimization, ensembles | Combination of statistical, heuristic, and AI models | DL + bioinspired algorithms | [28,29,30] | Genetic algorithms optimized feature selection for predicting tutoring needs; hybrid ensembles combined decision trees and DL to identify at-risk students more accurately. |

| Explainable AI (XAI) | Interpretable decision trees, attribution methods, rule-based models | Explainable supervised models | Integration of XAI with DL | [31,32,33,34,35,36,37] | XAI applied to show which variables (e.g., attendance, forum participation) most influence predictions of academic failure, providing transparent insights for instructors. |

| Category | Description | Examples | Articles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Educational Level | Most studies focus on higher education, covering undergraduate and graduate programs. | Undergraduate programs in engineering, computer science, and technical university training [32,36] | [19,23,24,43,53,58] |

| Educational Modality | Studies predominantly take place in e-learning and hybrid environments, driven by the COVID-19 pandemic. | Distance education, virtual courses, LMS platforms, hybrid classes | [25,38,42,60,61] |

| Type of Institution | Studies include both public and private universities, mainly in Latin America, Asia, and Europe. | Higher education institutions in developing countries, prestigious universities | [29,43,49,53,59] |

| Specific Contexts | Some studies focus on specific academic disciplines like programming, mathematics, and science. | Courses in programming, mathematics, computer science, adaptive e-learning | [18,62,63] |

| Post-pandemic Education | The pandemic’s impact has driven digital transitions and AI adoption in education. | Predictive models adapted to remote modalities post-pandemic, online support | [46,47,48,51] |

| Category | Description | Examples | Articles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academic Performance | Prediction of students’ academic results based on grades, GPA, and evaluations | Final grade prediction, GPA estimation, subject-wise performance | [20,23,24,28,63,68] |

| Student Dropout | Early identification of students at risk of leaving or disengaging | Dropout prediction, attrition rates based on virtual platform interaction | [22,24,30,33,35,56] |

| Personalized Academic Tutoring | Use of AI to assign tutoring, interventions, or personalized academic support | Recommendation systems based on predictions of low performance or dropout | [55,57,58,69] |

| Retention Prediction | Estimation of the likelihood that a student continues in their academic program | Student retention prediction, risk analysis in long-term programs | [19,44,53,61] |

| Emotional and Psychological Well-being | Prediction of psychosocial variables such as anxiety or motivation and their effect on performance | Prediction of academic stress, anxiety, and motivation and their academic impact | [46,47,48,49,50,51] |

| AI Technique | Advantages | Limitations | Computational Costs | Data Requirements | AI Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical ML models (decision trees, logistic regression, random forest, SVM, KNN) | Moderate accuracy; easy to implement; scalable with institutional databases | Limited capacity to capture complex non-linear patterns | Low–Moderate | Structured academic data (grades, attendance, LMS logs) | [20,23,24,28,63,68] |

| Deep learning (ANN, CNN, RNN, transfer learning) | High predictive accuracy; ability to process large-scale and unstructured data (e.g., behavioral or emotional) | High demand for computing power; low interpretability (black-box risk) | High | Large datasets, often multimodal (academic + behavioral + affective) | [22,24,30,33,35,56] |

| Hybrid approaches (ensembles, DL + XAI, bioinspired) | Balance between accuracy and generalization; capacity to integrate multiple data sources | Higher implementation complexity; need for specialized expertise | High–Very High | Heterogeneous and multidimensional data (academic, psychosocial, contextual) | [55,57,58,69] |

| Explainable AI (interpretable trees, attribution methods, rule-based models) | Enhances transparency and trust; supports pedagogical adoption by educators | May reduce predictive accuracy compared to opaque models | Moderate–High | Structured and semi-structured data | [19,44,53,61] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fierro Saltos, W.R.; Fierro Saltos, F.E.; Elizabeth Alexandra, V.S.; Rivera Guzmán, E.F. Leveraging Artificial Intelligence for Sustainable Tutoring and Dropout Prevention in Higher Education: A Scoping Review on Digital Transformation. Information 2025, 16, 819. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16090819

Fierro Saltos WR, Fierro Saltos FE, Elizabeth Alexandra VS, Rivera Guzmán EF. Leveraging Artificial Intelligence for Sustainable Tutoring and Dropout Prevention in Higher Education: A Scoping Review on Digital Transformation. Information. 2025; 16(9):819. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16090819

Chicago/Turabian StyleFierro Saltos, Washington Raúl, Fabian Eduardo Fierro Saltos, Veloz Segura Elizabeth Alexandra, and Edgar Fabián Rivera Guzmán. 2025. "Leveraging Artificial Intelligence for Sustainable Tutoring and Dropout Prevention in Higher Education: A Scoping Review on Digital Transformation" Information 16, no. 9: 819. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16090819

APA StyleFierro Saltos, W. R., Fierro Saltos, F. E., Elizabeth Alexandra, V. S., & Rivera Guzmán, E. F. (2025). Leveraging Artificial Intelligence for Sustainable Tutoring and Dropout Prevention in Higher Education: A Scoping Review on Digital Transformation. Information, 16(9), 819. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16090819