Using Large Language Models to Simulate History Taking: Implications for Symptom-Based Medical Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

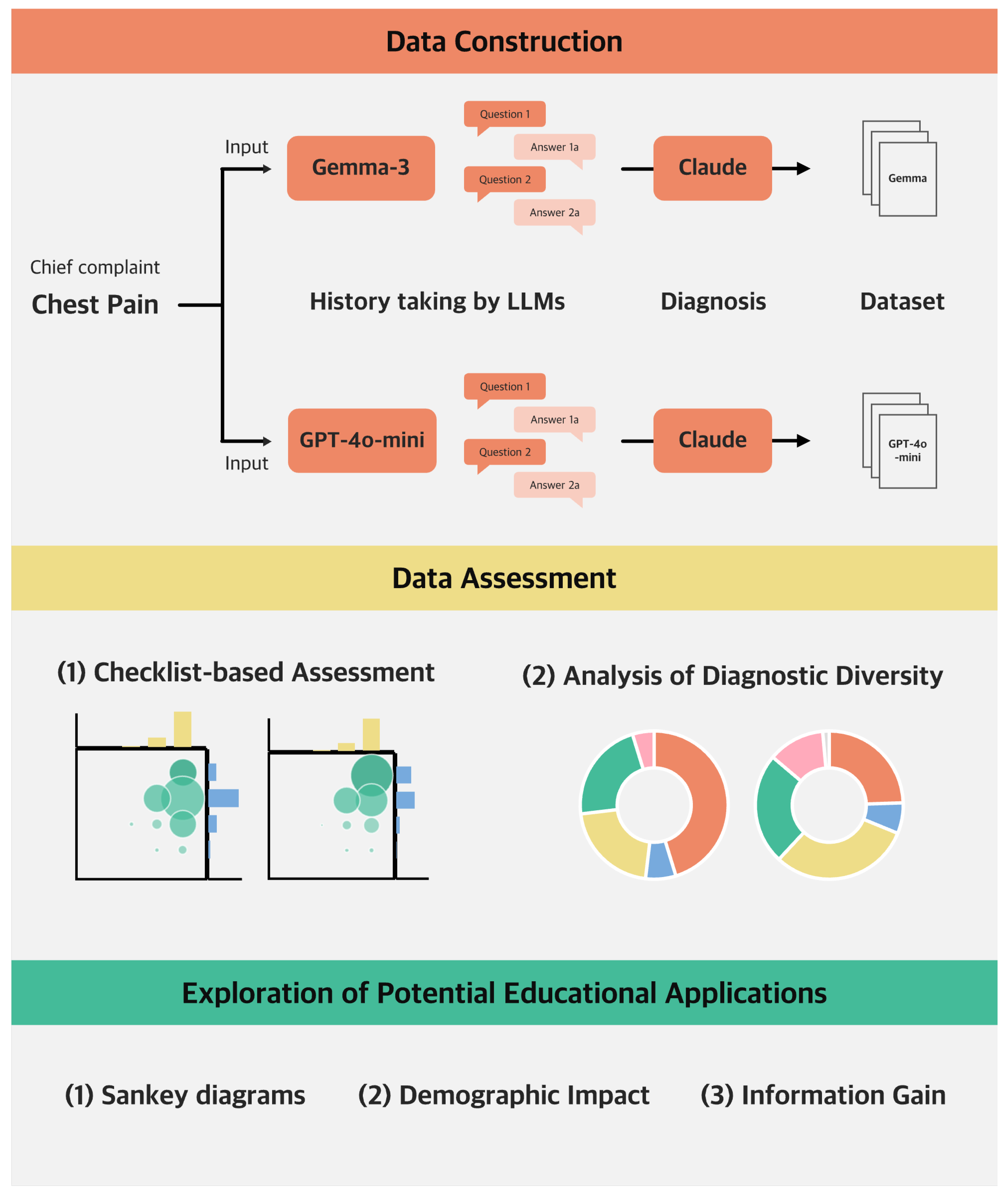

2. Materials and Methods

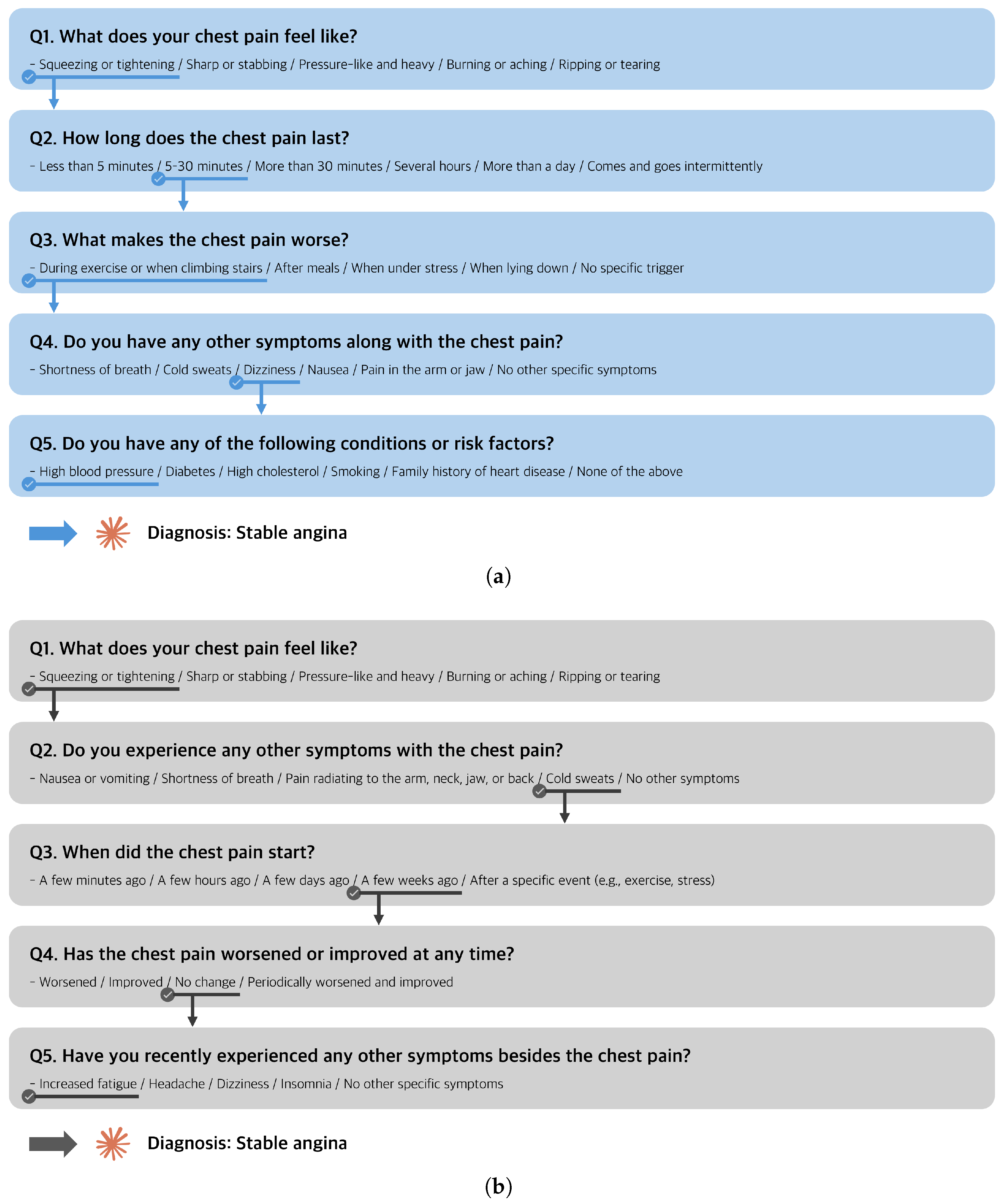

2.1. Dataset Construction and Assessment

- Question: What does your chest pain feel like?

- Response options: Squeezing or tightening/sharp or stabbing/pressure-like and heavy/burning or aching/tearing or ripping.

2.1.1. Checklist-Based Assessment of Medical Appropriateness

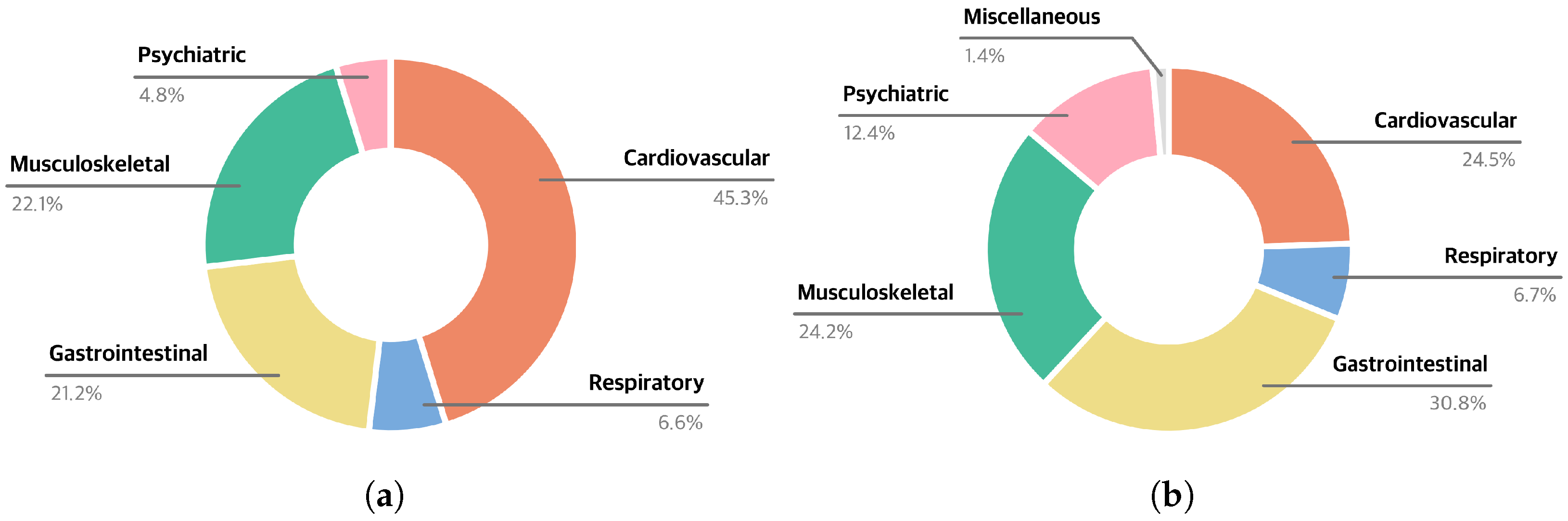

2.1.2. Analysis of Diagnostic Diversity

2.2. Exploration of Potential Educational Applications

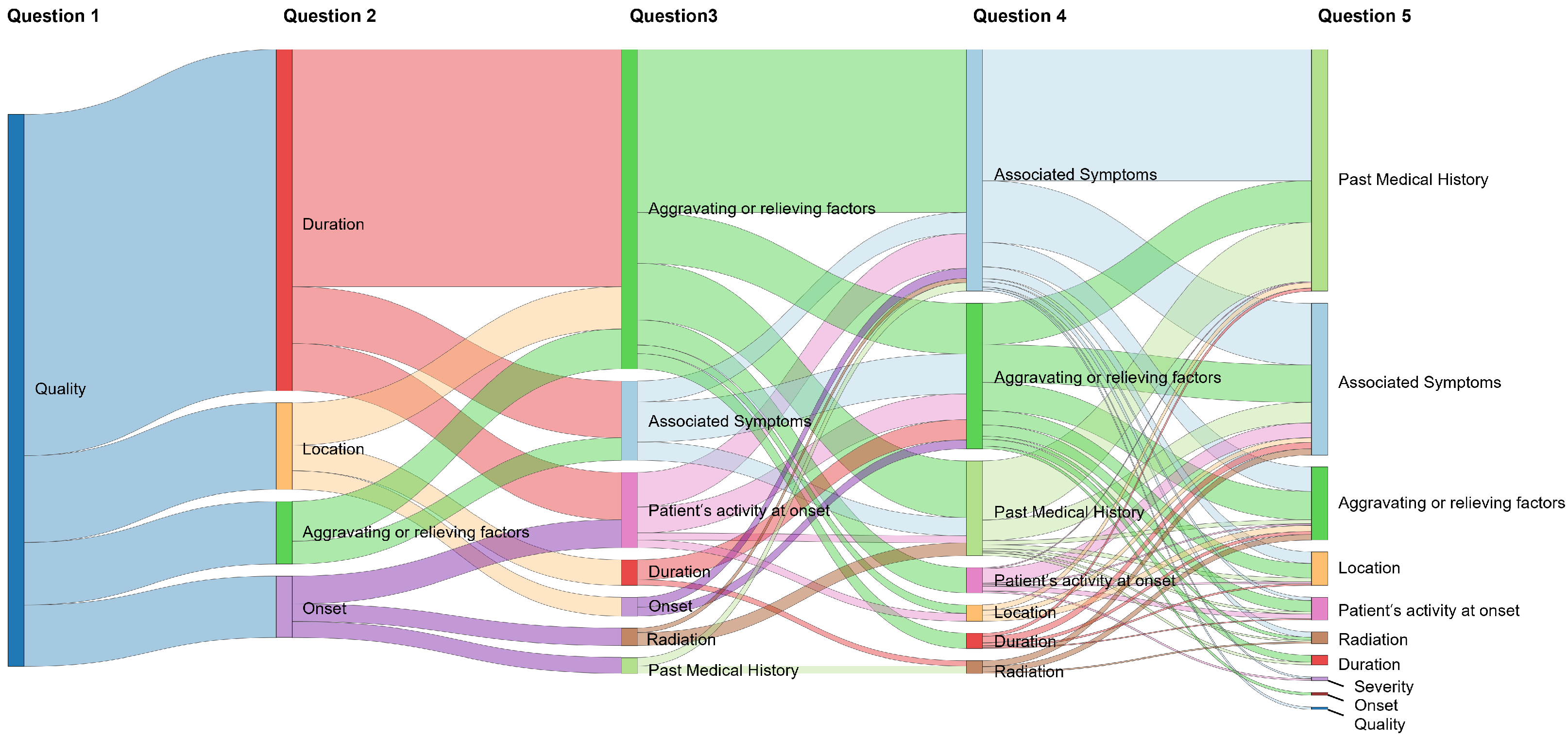

2.2.1. Visualization of Diagnostic Pathways

2.2.2. Analysis of Age-Specific and Sex-Specific Dialogue Patterns

2.2.3. Identifying High-Impact Questions for Diagnosis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of LLM-Generated History-Taking Dialogues

3.2. Exploration of Potential Educational Applications

3.2.1. Sankey Diagram

3.2.2. Age-Specific and Sex-Specific Dialogues

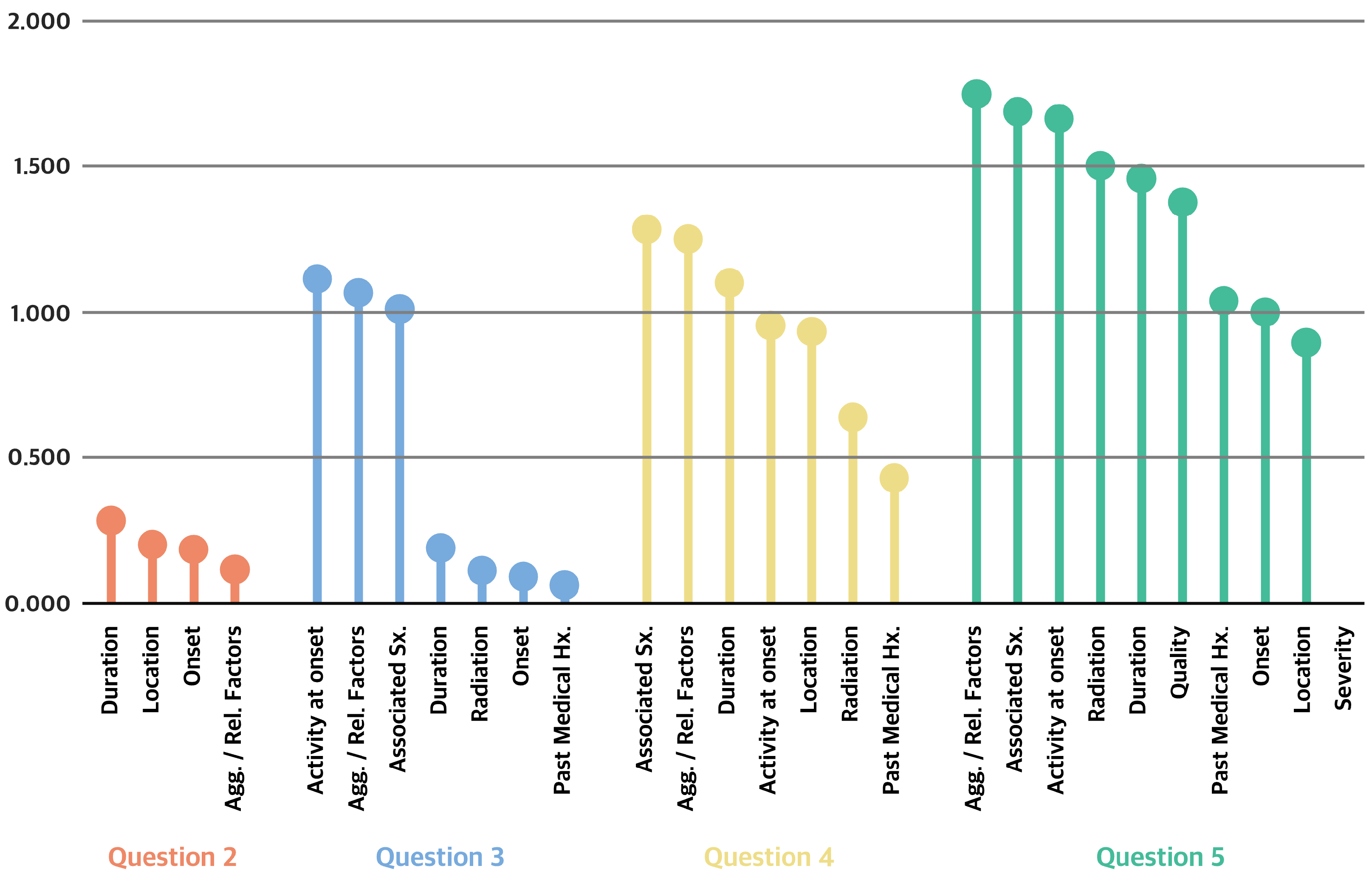

3.2.3. IG Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Can the Fine-Tuned Gemma-3-27B Perform Effective History Taking?

4.2. How Can LLM-Generated Dialogues Support Medical Students in Learning History Taking?

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LLMs | Large language models |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| CPC | Chest Pain Checklist |

| IG | Information gain |

References

- Peterson, P.; Baker, E.; McGaw, B. International Encyclopedia of Education; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bösner, S.; Pickert, J.; Stibane, T. Teaching differential diagnosis in primary care using an inverted classroom approach: Student satisfaction and gain in skills and knowledge. BMC Med. Educ. 2015, 15, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiesewetter, J.; Ebersbach, R.; Tsalas, N.; Holzer, M.; Schmidmaier, R.; Fischer, M.R. Knowledge is not enough to solve the problems–The role of diagnostic knowledge in clinical reasoning activities. BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faustinella, F.; Jacobs, R.J. The decline of clinical skills: A challenge for medical schools. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2018, 9, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schopper, H.; Rosenbaum, M.; Axelson, R. ‘I wish someone watched me interview:’ Medical student insight into observation and feedback as a method for teaching communication skills during the clinical years. BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrasheedi, A.A. Deficits in history taking skills among final year medical students in a family medicine course: A study from KSA. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2018, 13, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zeng, C.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, M.; Zou, L. Leveraging large language model as simulated patients for clinical education. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.13066. [Google Scholar]

- Holderried, F.; Stegemann-Philipps, C.; Herrmann-Werner, A.; Festl-Wietek, T.; Holderried, M.; Eickhoff, C.; Mahling, M. A language model–powered simulated patient with automated feedback for history taking: Prospective study. JMIR Med. Educ. 2024, 10, e59213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, C.; Kang, K. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2020 Emergency Department Summary Tables. 2022. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/121911 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Johri, S.; Jeong, J.; Tran, B.A.; Schlessinger, D.I.; Wongvibulsin, S.; Barnes, L.A.; Zhou, H.Y.; Cai, Z.R.; Van Allen, E.M.; Kim, D.; et al. An evaluation framework for clinical use of large language models in patient interaction tasks. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, R.; Hockberger, R.; Gausche-Hill, M.; Erickson, T.; Wilcox, S. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 202–210. [Google Scholar]

- Loscalzo, J.; Fauci, A.; Kasper, D.; Hauser, S.; Longo, D.; Jameson, J.L. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 21st ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, M.C.; Tierney, L.M., Jr.; Smetana, G.W. The Patient History: An Evidence-Based Approach to Differential Diagnosis, 2nd ed.; The McGraw-Hill Companies: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 261–272. [Google Scholar]

- Gulati, M.; Levy, P.D.; Mukherjee, D.; Amsterdam, E.; Bhatt, D.L.; Birtcher, K.K.; Blankstein, R.; Boyd, J.; Bullock-Palmer, R.P. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 78, e187–e285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, E.; Culakova, E.; Meng, S.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, H.; Mohile, S.; Flannery, M.A. Overview of Sankey flow diagrams: Focusing on symptom trajectories in older adults with advanced cancer. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2022, 13, 742–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsia, R.Y.; Hale, Z.; Tabas, J.A. A national study of the prevalence of life-threatening diagnoses in patients with chest pain. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 1029–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.S.; Han, H.S.; Kim, W.; Kim, C.; Jang, J.Y.; Kwon, W.; Heo, J.S.; Shin, S.H.; Hwang, H.K.; Park, J.S. Clinical implications of young-onset pancreatic cancer patients after curative resection in Korea: A Korea Tumor Registry System Biliary Pancreas database analysis. HPB 2023, 25, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, S.; Maoli, A.; Rauch, G.; Giacomini, M. Entropy-driven decision tree building for decision support in gastroenterology. In Data and Knowledge for Medical Decision Support; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 93–97. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, A.; Koda, M.; Ogawa, H.; Miyoshi, T.; Maeda, Y.; Otsuka, F.; Ino, H. Enhancing Medical Interview Skills Through AI-Simulated Patient Interactions: Nonrandomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Med. Educ. 2024, 10, e58753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, Y.; Kim, K.J. The feasibility of using generative artificial intelligence for history taking in virtual patients. BMC Res. Notes 2025, 18, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Luo, C.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Z. Conversational disease diagnosis via external planner-controlled large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.04292. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Z.; Zheng, L.; Hu, R.; Xu, Y.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Chen, W.; Wu, J.; Cai, H.; Ying, H. LLMs Can Simulate Standardized Patients via Agent Coevolution. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.11716. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, T.; Schaekermann, M.; Palepu, A.; Saab, K.; Freyberg, J.; Tanno, R.; Wang, A.; Li, B.; Amin, M.; Cheng, Y.; et al. Towards conversational diagnostic artificial intelligence. Nature 2025, 642, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bösner, S.; Haasenritter, J.; Hani, M.A.; Keller, H.; Sönnichsen, A.C.; Karatolios, K.; Schaefer, J.R.; Baum, E.; Donner-Banzhoff, N. Gender differences in presentation and diagnosis of chest pain in primary care. BMC Fam. Pract. 2009, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Item | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Quality | Character or nature of the chest pain (e.g., sharp, dull) |

| 2 | Location | Site of pain on the chest |

| 3 | Radiation | Site of radiated pain other than the chest (e.g., arm, jaw) |

| 4 | Onset | Timing of chest pain onset |

| 5 | Duration | How long a chest pain episode lasts |

| 6 | Aggravating or relieving factors | Factors that worsen or soothe the pain |

| 7 | Associated symptoms | Other symptoms present (e.g., shortness of breath, nausea) |

| 8 | Past medical history | Relevant pre-existing medical or surgical conditions |

| 9 | Patient’s activity at onset | What the patient was doing at the time of chest pain onset (e.g., exertion, fall on the chest) |

| 10 | Severity | Intensity of the pain |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huh, C.Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, G.; Jang, Y.; Ko, H.-s.; Suh, M.J.; Hwang, S.; Son, H.J.; Song, J.; Kim, S.-J.; et al. Using Large Language Models to Simulate History Taking: Implications for Symptom-Based Medical Education. Information 2025, 16, 653. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16080653

Huh CY, Lee J, Kim G, Jang Y, Ko H-s, Suh MJ, Hwang S, Son HJ, Song J, Kim S-J, et al. Using Large Language Models to Simulate History Taking: Implications for Symptom-Based Medical Education. Information. 2025; 16(8):653. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16080653

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuh, Cheong Yoon, Jongwon Lee, Gibaeg Kim, Yerin Jang, Hye-seung Ko, Min Jung Suh, Sumin Hwang, Ho Jin Son, Junha Song, Soo-Jeong Kim, and et al. 2025. "Using Large Language Models to Simulate History Taking: Implications for Symptom-Based Medical Education" Information 16, no. 8: 653. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16080653

APA StyleHuh, C. Y., Lee, J., Kim, G., Jang, Y., Ko, H.-s., Suh, M. J., Hwang, S., Son, H. J., Song, J., Kim, S.-J., Kim, K. J., Kim, S. I., Kim, C. O., & Ko, Y. G. (2025). Using Large Language Models to Simulate History Taking: Implications for Symptom-Based Medical Education. Information, 16(8), 653. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16080653