Abstract

Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) are increasingly necessary in the educational context. Digital resources could support socio-educational practices to intervene with vulnerable groups, such as people with disabilities, and improve their accessibility and inclusion. This study aims to analyse educators’ perceptions of ICT resources for socio-educational intervention with people with disabilities, as well as to determine their training needs and the possibilities and risks derived from their use. A qualitative methodology has been used to analyse the content of 12 semi-structured interviews with social educators. All of them work with students with disabilities in the extracurricular field. Based on the results, the educators habitually use popular digital devices, such as computers. They regularly search for content on the internet to obtain and disseminate ideas, perceiving an adequate domain. However, there is a need for training on specific digital resources to intervene with students with disabilities. The study highlights the need to investigate the causes that may limit some ICT uses by educators and foster the design of specific training programmes to harness the potential of ICT in socio-educational intervention.

1. Introduction

Programmes and strategies in the international and European context addressing the needs of persons with disabilities recognise the need to provide accessible, inclusive, and quality education. The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union [1] recognised the right of persons with disabilities to receive measures that guarantee their autonomy and social participation. Subsequently, the International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [2] urged states to promote equality and encourage the inclusion of this vulnerable group, eliminating existing barriers and providing the necessary support. More recently, new strategies on the rights of persons with disabilities have been promoted, aimed at ensuring the full socio-educational and labour inclusion of persons with disabilities by creating accessible physical and digital environments [3,4]. However, these measures still present challenges for their implementation in educational practice [5].

People with disabilities require specialised attention, as they also sometimes have a high level of vulnerability that hinders their socio-educational inclusion process [6]. Their active participation in society can be effective if they receive the necessary support to develop their lives with autonomy and well-being [7]. To this end, educators must employ useful strategies and resources to address their needs through socio-educational intervention.

In the educational context, digital tools are integrated and have been widely used by educators in interventions targeted at people with disabilities. The applicability of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) is oriented towards the design, implementation, and evaluation of programmes or resources [8] or to obtain information [9]. Digital resources in education can also facilitate accessibility to information [10]. This approach is aligned with Sustainable Development Goal 4: Quality Education [11], considering the attention to diversity [12,13], which implies recognising the characteristics and individualities of each student to offer an intervention adapted to their needs, create new environments, and use strategies and resources to promote inclusion.

Computers or assistive technologies are ICT resources with potential for intervention with people with disabilities [14]. These tools can support interventions, simplify the design process, and improve the quality and efficiency of their implementation and evaluation. Smartphones and tablets improve student engagement, enhance communication skills, and provide entertainment [15], thereby promoting inclusion [16]. ICT tools in interventions with students with disabilities can help education professionals to personalise teaching and support accessibility, as well as to encourage innovation [17]. It is important to strengthen the design, implementation, and evaluation of experiences supported by digital tools in socio-educational practice. In this way, the process would be simplified, and the interventions would become more efficient and reach a higher quality.

Educators in extracurricular contexts have stated lower levels of digital competence compared to teachers in mainstream schools [18]. Therefore, ICT tools used by educators should be broad and not reduced to management tasks [19]. To harness digital resources for addressing the diversity of students, professionals need solid initial training and awareness of the importance of working with ICT tools. Furthermore, the literature calls for studies analysing the use of a specific technology in the context of people with disabilities [20]. This framework claims a need to investigate the use of ICT tools by educators working with vulnerable groups [21], particularly people with intellectual disabilities, to design training strategies that promote their use in extracurricular contexts.

The general objective of this study is to analyse educators’ perceptions of ICT resources for intervention with people with disabilities in the extracurricular field, as well as to determine their training needs and the possibilities and risks they associate with their use. To this end, the following specific objectives (SO) have been considered:

- To identify the ICT resources used by educators (SO 1).

- To detect the frequency of use of ICT resources by educators (SO 2).

- To determine the technical handling and training needs of educators regarding ICT (SO 3).

- To reveal the functions that educators attribute to ICT resources for intervention with people with disabilities (SO 4).

- To discover the advantages and disadvantages that educators attribute to the use of ICT with people with disabilities (SO 5).

2. Disability and ICT Resources for Addressing Diversity

The term disability is complex and multifaceted [22]. Historically, it has been associated with medical conditions that may impact physical, mental, sensory, or intellectual functioning, although it also involves contextual factors [23]. People with disabilities face inclusion and accessibility challenges [24,25]. They could encounter barriers to full and autonomous participation in activities of daily living in the educational, social, and employment spheres, which causes them vulnerability.

Disability depends on multiple causal factors, so the needs of each person are different. In the case of students with disabilities, their vulnerability is associated with the learning process, socio-emotional aspects, chronic illnesses, and physical, visual, auditory, speech, or intellectual development [26]. Therefore, socio-educational intervention programmes must offer specific alternatives for personalised attention to diversity adapted to their needs.

The use of ICT resources can offer multiple benefits for educators and students with intellectual disabilities. For education professionals, these resources can enhance innovation [27], communication, and collaboration, allowing them to improve and disseminate their interventions [28]. For students, digital tools can benefit their learning process [29] and general development. In addition, they will be able to access information more easily in different media, increasing their autonomy [30] and social participation [31]. ICT resources also have the potential to foster their autonomy [32] and motivation [33]. Thus, all these aspects would contribute to reducing their vulnerability.

Despite the multiple advantages derived from ICT resources for people with intellectual disabilities in the socio-educational field, there are different challenges that educators still must face. In this regard, the scientific literature highlights different training needs in educators when using ICT tools [34], which can hinder their interventions. Education professionals are receptive to expanding their knowledge of digital resources [35]. To promote the appropriate use of ICT tools for addressing diversity, professionals must receive solid initial training and develop awareness of the importance of working with these resources [36]. Therefore, it is necessary to implement personalised programmes according to their needs and characteristics [37]. The negative impact of the digital divide is also evident for educators. To mitigate this aspect, digital literacy should be improved [38], and greater protection and privacy of data posted on the Internet must be guaranteed [39].

There are different types of ICT tools for interventions with people with disabilities. A study [40] identified various hardware resources (tablet, smartphone, computer, etc.) and developed classification criteria (multi-functional technologies, technologies for communication, collaboration, and exploration, learning support technologies, etc.). This theoretical framework considers the characteristics of the target users, the technology itself, the contexts, and the learning activities for which the technology can be used with people with disabilities.

To explore existing studies on ICT resources and people with intellectual disabilities, a search was carried out in the Web of Science database (search in: Web of Science Core Collection, collection: Social Sciences Citation Index). The following terms were introduced under the option ‘Topic’: (ICT OR digital OR technolog*) AND (resourc* OR device* OR computer* OR tablet* OR smartphone*) AND (learning OR assistive OR communication OR collaboration OR exploration OR support OR multi-functional) AND (“intellectual disabilit*”). The initial search yielded 288 documents. Different document inclusion/exclusion filters were applied to refine the results: only articles were considered, and the Web of Science categories ‘Education Special’ and ‘Education Educational Research’ were selected. A total of 117 documents were obtained.

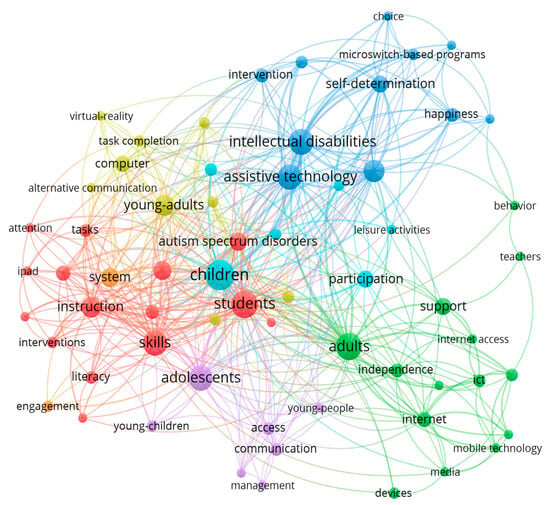

An analysis of the keywords of these papers shows that the most common digital resources are computers and assistive technologies. In general, ICT tools aim to improve the quality of life of the target individuals, as well as their social participation or independence (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

ICT use with people with intellectual disabilities. Note. Designed using VOSviewer software (version 1.6.20).

Various studies highlighted the potential of using ICT tools in interventions with people with intellectual disabilities to address their needs across different age groups. For example, robot programming improved language and spatial abilities in children [41]. Another study demonstrated the usefulness of ICT tools to promote social participation by enhancing communication and self-determination in young people with intellectual disabilities [42]. In the case of adults, the use of virtual reality applications with people with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) has proven beneficial [43].

Different case studies identified the use of ICT resources to support intervention strategies or resources for people with intellectual disabilities. For instance, art therapy enabled them to engage in creative activities [44]. Mobile devices have also been employed for activities such as dance [45]. Other studies have shown interest in digital games for enhancing learning [46], as well as the potential of interactive digital tools for mathematics learning [47]. These findings demonstrate the potential of ICT resources in both curricular and extracurricular interventions.

It is worth noting the growing interest in emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and people with disabilities. Specifically, AI-based interventions have been conducted with students with ASD, achieving high levels of participation [48]. AI tools have also been used to develop skills in students with mild intellectual disabilities, with implications for the educational inclusion process [49]. The use of these technologies by educators is expected to help personalise learning and the development of cognitive, social, and emotional skills of the people with intellectual disabilities.

3. Materials and Methods

The study employs qualitative methods. This type of research is characterised by focusing its methodological process on the texts and messages that emerge from discourses. The analyses can be presented in tables or figures to illustrate the socio-educational situation, offering a detailed and holistic view. The aim is to understand the qualities that characterise concrete situations through concept interrelations [50]. This modality provides insight into actions and contextual facts through in-depth analysis of information (in this case, it was collected through interviews). The study focused on educators’ perspectives on ICT resources in interventions with students with intellectual disabilities.

3.1. Context and Participants

In various countries, laws protecting the rights of people with disabilities promote their inclusion and social participation. Legislation emphasises the need to promote human rights and equal opportunities by providing the necessary support [51] to foster the development of personal autonomy and independent living [52].

In the Spanish context, regulations highlight the importance of promoting equal opportunities, non-discrimination, and cognitive accessibility for people with disabilities [53]. Furthermore, Spanish educational legislation [54] states the need to guarantee specific measures, resources, and supports to ensure the principle of equity and the right to education for students with disabilities. This law also indicates that the needs of students with intellectual disabilities can be addressed in mainstream schools or special education centres, particularly when more specialised attention is required. Digital resources are mentioned for addressing diversity.

In the extracurricular context, there are institutions or associations attended by students with disabilities of all ages who require external development and learning support [55]. These institutions focus on supporting and promoting personal, social, and/or vocational development by undertaking actions to foster the inclusion of people with disabilities within the community [56]. A variety of professional profiles work in these associations, such as social educators, social workers, or educational psychologists. In particular, the role of social educators is to plan interventions to stimulate different skills and improve performance in the daily activities of vulnerable groups [57].

The associations involved in the study are non-profit and focus on developing extracurricular interventions with students with intellectual disabilities. Consequently, most students attend regularly (for 2 to 6 h per week) to reinforce or, in most cases, complete their academic training. Moreover, these institutions are generally equipped with different material resources, including ICT, to be applied in socio-educational interventions.

To access the participants, 4 associations aimed at socio-educational intervention with people with intellectual disabilities in the extracurricular context were contacted. The institutions are located in northwest Spain. Their actions are focused on improving the quality of life of students through early interventions, speech therapy, or educational and therapeutic support. These actions are oriented to improve, in the medium or long term, the inclusion of this group of vulnerable people in the socio-educational and socio-labour fields.

Initial contact with potential study participants was established through visits to the target institutions. Subsequently, the request for interviews was sent to the educators by email (as they are the professionals responsible for socio-educational interventions), informing them of the purpose of the research.

The study involved 12 social educators (10 women and 2 men) aged between 25 and 40 with 1 to 19 years of work experience (Table 1). The participants consented to the use of the information for research purposes. The researchers have been guaranteed confidentiality and anonymity to process the data for scientific purposes.

Table 1.

Profile data of the participants.

3.2. Instrument and Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews were used for data collection. This qualitative technique allowed the researchers to obtain valuable textual information from a structured script of questions and understand the participants’ perception of ICT resources [58]. The script of questions has been elaborated under the guidance of 2 expert researchers, who are specialists in ICT resources in socio-educational intervention and qualitative analysis techniques.

The interviews were conducted in November 2024. Participants were asked to provide informed consent for the use of the information for research purposes. In the interview protocol, it was established that recordings would be stored securely, personal data would be protected throughout the study, and participants could contact the study coordinators at any time to request information.

During the interviews, the profile data of each participant was registered (age, gender, qualifications, years of professional experience, and position held). Then, 9 questions linked to the specific objectives of the study were posed (Table 2). Each interview lasted approximately 30 min.

Table 2.

Question script associated with the specific objectives.

3.3. Data Analysis

Once the data collection was completed, the qualitative content analysis was conducted. The specific objectives of the study and the interview questions guided the determination of the main categorisation of the analysis (Table 3). To preserve the anonymity of the participants, the interviews were coded and numbered consecutively from 1 to 12. This ensured that the identity of the participants remained anonymous throughout the research process, and only authorised members of the research team had access to the data. The interviews were then transcribed verbatim into English (they were conducted in Spanish) to proceed with their analysis.

Table 3.

Main categories of analysis.

The data analysis was supported by MAXQDA software (version 24.8), which allowed for the coding of categories based on the information collected from each interview, following the previously established order (from interview no. 1 to interview no. 12). During the analysis process, main ideas were identified first, followed by secondary ones, leading to categorisation at different levels.

The coding procedure used was predominantly inductive, except for the categories related to ICT resources. This is because the inductive categorisation process provides a novel classification and is useful when existing deductive classifications derived from the scientific literature do not fit. Inductive categorisation will expand the information and theoretical corpus on the topic [60]. Given the specificity of the objectives in this study, a mixed inductive-deductive approach was employed [61]. Different classifications of ICT resources intended for people with disabilities were identified in the literature. They refer to hardware (computer, tablet, smartphone) [40] and software (web and specific applications) [59]. These classifications were complemented with subcategories that emerged from the raw data and were initially labelled as ‘Others’, both for hardware (projector, digital whiteboard, TV, printer, virtual reality, and camera) and for software in the case of ‘specific applications’ (pictograms, digital whiteboard software, training courses, and tests).

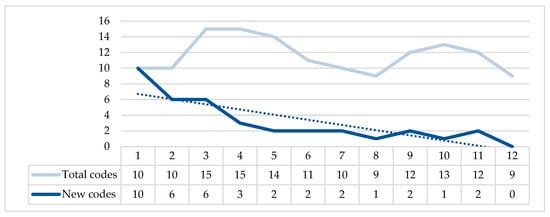

Thematic saturation of the codes (units of analysis) has been calculated, obtaining the point at which the most relevant information is reached in response to the established objectives [62]. This analysis was based on the process followed in another qualitative study [63]. For each interview, the appearance of new codes was compared with those of the previous interview. The number of interviews conducted (n = 12) was determined as the codes reached saturation. The thematic saturation of codes was reached in interview 11. In the final interview, nine codes were identified, all of which had appeared in previous interviews. Thus, categorical saturation was confirmed (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Categorical saturation of codes. Note. X-axis: Participants/interviews. Y-axis: Number of codes. Dotted line: Linear trendline of new codes.

4. Results

The results are presented according to the specific objectives (SO) established. Two subsections were established to present the findings. The first subsection focuses on the ICT resources (SO 1), the frequency of use (SO 2), and the technical handling and training (SO 3). The second subsection includes the functions (SO 4) and advantages and disadvantages (SO 5) derived from ICT to intervene with people with disabilities.

4.1. ICT Resources, Frequency of Use, Technical Handling, and Training (SO 1, 2, and 3)

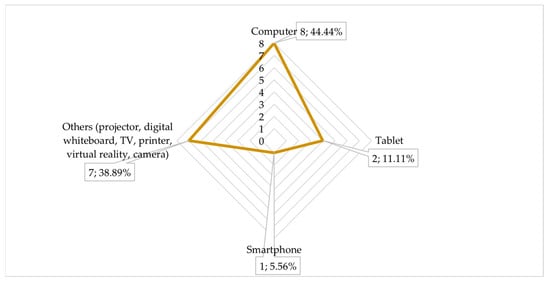

The educators highlight the use of different technological resources in socio-educational intervention with people with disabilities. There is agreement between the hardware devices available in the centres and those used by the educators, except for the digital camera and virtual reality glasses. These professionals mainly use computers and tablets, followed by projectors, digital whiteboards, smartphones, televisions, and printers (Figure 3). One of the educators stated, ‘We use computers, projectors and interactive whiteboards to work online and collaboratively with various digital applications, and to carry out activities adapted to each student’ (participant no. 11, 32-year-old woman).

Figure 3.

Hardware devices available/used in the associations by educators.

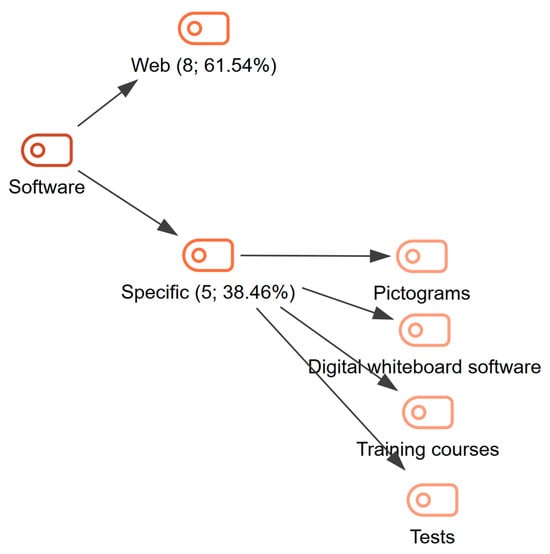

Education professionals make notable reference to websites, which they mainly use to extract ideas, materials, or resources for their interventions. They also highlight specific software for obtaining pictograms, attending online courses, and using digital whiteboard programs or platforms for designing tests (Figure 4). For example, one of the participants indicated, ‘The group we work with is the group of people with intellectual disabilities. An online course platform makes it easy for us to access courses adapted to our needs’ (participant no. 6, 38-year-old woman). In this case, the online platform mentioned for delivering open courses is MIRÍADAX.

Figure 4.

ICT resources to intervene with people with disabilities.

ICT resources are employed by most educators daily (9/12; 75%). Exceptionally, they indicated monthly (2/12; 16.67%) or weekly (1/12; 8.33%) use. In this sense, one of the participants pointed out, ‘At least once a week, I use digital resources to plan complementary activities for the students, such as the organisation of outings or activities for the sensory stimulation workshop. Also, if we have to create or design new materials, I use ICT more often’ (participant no. 10, 27-year-old woman).

Educators reported a technical domain for using ICT resources in their professional practice (9/12; 75%). Occasionally, the participants reported deficient employment (3/12; 25%). According to the training received in digital resources, the educators reported self-taught learning (9/12; 75%) or training promoted by the associations (8/12; 66.67%). The training needs identified led the educators to demand specialised courses on the use of ICT (6/12; 50%). In this regard, one of the participants states, ‘Specific training is necessary to be able to work day-to-day with people with disabilities. Furthermore, we must continue training ourselves because ICT is constantly evolving, and we need to adapt to the changes’ (participant no. 1, 26-year-old woman). In contrast, others (6/12; 50%) declare that they have no training deficiencies in using digital tools.

Exceptionally, educators’ interest in platforms for recording information (1/12; 8.33%). See the following excerpt: ‘I would like to have a platform where I could record and dump the students’ data during the interventions, as well as other information of interest from the sessions carried out. Also, these platforms could analyse the content and calculate statistical data’ (participant no. 11, 32-year-old woman).

4.2. ICT Functions, Advantages, and Disadvantages (SO 4 and 5)

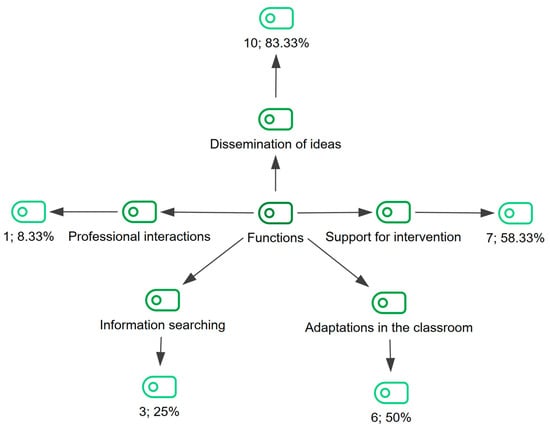

The participants highlighted different functions of ICT for obtaining and disseminating ideas through the internet, acquiring support for socio-educational interventions, adapting the classroom to implement activities, or promoting the interaction between professionals (Figure 5). For example, concerning adaptations during the interventions, a participant indicates that ‘ICT resources are very useful for people with disabilities to work with examples from everyday life. That is why we use them to simulate real situations’ (participant no. 9, 29-year-old woman). Another educator highlights a use of ICT for ‘Preparing materials and documentation, sending notifications, obtaining online training, or interacting with the people we work with’ (participant no. 4, 27-year-old woman).

Figure 5.

ICT functions from the perspective of the educators.

The educators identified different advantages of using ICT, mainly for access to information and the positive impact on the inclusion process or communicative relations, and disadvantages related to internet risks or the negative impact on some students’ skills (Table 4). These professionals associate ICT use with the immediacy of information or events in everyday life. In this sense, they value positively the instantaneous provision of information. They add that ICT resources can favour, in many situations, the inclusion of people with disabilities. Other advantages are associated with the increasing ease of ICT access, as well as the promotion of social interaction among students, by relying on these resources. Different examples of educators’ perceptions of the benefits of ICT can be seen in the following excerpts:

‘ICT use facilitates better inclusion of people with disabilities in society and their peer group’(participant no. 1, 26-year-old woman).

‘ICTs are open sources of information (…). They break down the barriers of space and time and allow instant communication with other people at any time and place’(participant no. 4, 27-year-old woman).

‘An advantage of these resources is that, besides capturing people’s interest, they reduce workload due to their speed and allow time to be devoted to preparing other types of activities’(participant no. 10, 27-year-old woman).

Table 4.

Advantages and disadvantages of using ICT.

Some educators find risks derived from the ICT use, such as internet dangers, such as misinformation, causing isolation in people when they misuse it. They also point out that inappropriate ICT use can hinder the stimulation of the imagination and lead to discrimination, because they are not available to the whole population. Some of the disadvantages perceived by educators can be seen in the following excerpts:

‘Ill-intentioned ICT of some people can be very harmful to others, especially because of their high vulnerability’(participant no. 3, 39-year-old man).

‘Excessive ICT use can lead to isolation when interacting with other people, distractions and saturation due to the number of alternatives they offer’(participant no. 4, 27-year-old woman).

5. Discussion

Computers are the primary devices used by the educators in this study. This situation may be due to the multiple functions or the versatility of this hardware for addressing the diversity of students with disabilities. They offer resources for assistance or educational applications adapted to the individual needs of students [64]. Tablets have demonstrated their potential in educational interventions [65]. The projector or the digital whiteboard can increase the functionalities of computers. In addition, other devices, such as virtual reality glasses, which are found in the associations, are not used by educators. However, despite the challenges posed by its use, it could hold great potential for socio-educational intervention to address relevant needs in students with intellectual disabilities, such as the simulation of real-life experiences and the improvement of social interaction and communication [66], as well as the development of other adaptive skills [43].

ICT resources used by the educators are associated with searching the internet for information and other resources for educational intervention. The use of the internet has the potential to facilitate access to information or enhance learning, participation, and inclusion of people with disabilities [31]. The predominant use of this multifunctional technology [40] may be attributed to its ease of technical use and its status as an established resource within society. The educators have also mentioned, among other specific applications, digital resources to design or obtain pictograms. These graphic representations, or visual symbols, intended to facilitate communication, demonstrate their interest in socio-educational intervention for people with ASD [67]. Thus, all these resources could offer possibilities to address various difficulties for people with disabilities, such as barriers to inclusion or accessibility [68]. However, a priori, they require more specialised training compared to that needed for browsing the internet.

The educators intervening with people with disabilities reflect a regular use and a certain technical handling of ICT resources. In contrast, some studies have found a scarce and basic use of these tools by professionals of education [36,69]. Another study [70] shows certain technical skills about digital resources, which are considered 21st-century competences, focusing on computer use. The frequency of use and technical handling of digital tools by educators could depend on aspects associated with years of professional experience, age, or gender of the professionals [29]. Thus, these aspects should be considered when designing training courses. Moreover, the use of ICT tools may be influenced by other external factors, such as the innovative climate within work institutions or the resources allocated to fostering educators’ digital competences [71].

The training regarding ICT tools stated by educators has been self-taught or taken through specialised courses. This has led some participants not to require instruction about digital tools. In this study, training needs are associated with an interest in being better prepared for the technical handling of specific ICT resources. In this sense, workshops or webinars are common course formats for improving the quality of interventions [72]. Educators could attend these types of training to improve their training to cover the needs of the individuals with intellectual disabilities they work with. Another study [73] on the training of educators who work with students with disabilities highlighted the need for competent professionals in educational technology for the full development of students, which could also have a positive impact on their participation and motivation.

ICT resources are mostly used to gain insights to support the design of interventions, assisting them or recreating real and meaningful environments for students with disabilities. In educational research, it is relevant to create and disseminate knowledge to obtain practical applications [74]. In addition, there should be concrete guidelines or protocols to help educators evaluate the adaptation of web-based educational materials [75]. ICT use can foster the creation of multimedia environments that facilitate the learning of everyday concepts [76]. This is expected to facilitate the socio-educational and occupational inclusion of students with disabilities.

Multiple benefits have been shown using ICT tools in socio-educational practice. On the one hand, the instant availability of information and the ease of access to it on the internet for educators. These benefits can lead to an increased use of digital resources during interventions. In addition, they can favour inclusive education, as well as the empowerment of people with disabilities, as highlighted in other studies [77,78]. On the other hand, educators highlight that ICT misuse can lead to disinformation, which harms quality education, and can lead to isolation or limit the development of creative skills. However, an appropriate employment of ICT tools can foster personal interactions [79] and originality [80]. Therefore, the way ICT resources are used is very relevant, as it can have a positive or negative impact. In this regard, it will be of vital importance for educators to be properly trained [21].

6. Conclusions

Digital tools are useful resources for socio-educational intervention with students with intellectual disabilities. Specifically, educators mainly use easily accessible and widely recognised resources, such as computers and tablets. However, within the associations where they work, they have access to other cutting-edge technology resources to which these professionals still show resistance.

In their professional practice, the educators use ICT tools habitually, in particular web software to search for information on the internet. In addition, other specific tools to support extracurricular socio-educational interventions were mentioned. They are intended to foster communication among students, use specialised software, create tests, or obtain training. The educators prioritise easily accessible ICT resources that can provide immediate support through multiple functionalities, rather than using resources specifically designed for addressing intellectual disabilities.

In general, the educators in the extracurricular field participating in this study are satisfied with the technical handling, they state, with the digital tools. This could contribute to an increase in the frequency of their use in the future. However, opinions are divided on the need for further professional development to complement the knowledge they acquired through self-teaching or training courses. Addressing these training needs could foster the adoption of new resources, considering that ICT resources are constantly evolving.

ICT tools facilitate immediate access to information and provide different resources. However, it is desirable that its benefits are not only directed towards educators but also promote a positive impact on the socio-educational inclusion of students with intellectual disabilities. Although educators are optimistic about the potential of these tools, they must consider their risks and utilise ICT tools in an informed and critical manner. It is crucial to avoid the generation of inequalities caused by digital resources, so they must overcome the barriers and favour the development of creative skills and peer interaction among students.

7. Limitations and Prospects

This study has some limitations. Considering that it is qualitative research, its purpose is not generalisation. Nonetheless, its results and conclusions may be transferable to similar situations when approached with a critical perspective [81]. Concerning the data collection instruments, the study could be expanded by incorporating quantitative data collection techniques. Regarding the role of the participants, the study analysed the views of educators working in associations, as they are the ones implementing the interventions. However, the perspectives of other professionals, as well as those of the students and their families, could also be valuable.

Considering that the study reveals the presence of cutting-edge technology in the associations, it would be interesting to explore in greater depth the reasons limiting its use by educators. This could help improve the design, implementation, and evaluation of socio-educational interventions with people with disabilities. Future research should also explore in greater depth the training needs expressed by educators regarding specific ICT resources.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.-C.R. and J.D.-P.; methodology, M.-C.R. and V.F.-P.; software, J.D.-P.; validation, M.-C.R. and J.D.-P.; formal analysis, V.F.-P., M.-C.R. and J.D.-P.; investigation, M.-C.R. and V.F.-P.; data curation, V.F.-P.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D.-P. and V.F.-P.; writing—review and editing, M.-C.R.; visualisation, M.-C.R., V.F.-P. and J.D.-P.; supervision, M.-C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Doctoral Program in Educational and Behavioural Sciences, Faculty of Education and Social Work, Universidade de Vigo, Spain (CE-DCEC-UVIGO2022-03-29-0901) dated 15 September 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the educators for their participation in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ICT | Information and Communication Technologies |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2000/C 364/01). Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/charter/pdf/text_en.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- International Convention of 13 December 2006 on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Available online: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/documents/tccconvs.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- European Disability Strategy 2010–2020: A Renewed Commitment to a Barrier-Free Europe. Available online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/news/european-disability-strategy-2010-2020-renewed-commitment-barrier-free-europe (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Union of Equality: Strategy for the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2021–2030. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0101 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Medina-García, M.; Doña-Toledo, L.; Higueras-Rodríguez, L. Equal opportunities in an inclusive and sustainable education system: An explanatory model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, A.; Yillah, R.M.; Bash-Taqi, A. A study of vulnerable student populations, exclusion and marginalization in Sierra Leonean secondary schools: A social justice theory analysis. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, M.; Suich, H. Measuring disability inclusion: Feasibility of using existing multidimensional poverty data in South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, C.; Costescu, C.; Roşan, A. A preliminary study of a Math digital based intervention in children with intellectual disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2025, 159, 104947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Carter, R.A., Jr.; Lim, S.N. Designing Intelligent Agents for Students with Disabilities: Promoting Inclusion and Equity Through the Lens of Cultural-Historical Activity Theory. J. Spec. Educ. Technol. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.; Al Mutawaa, A.; Al Tamimi, A.; Al Mansouri, M. Assessing the readiness of government and semi-Government institutions in Qatar for inclusive and sustainable ICT accessibility: Introducing the MARSAD Tool. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-García, M.; Higueras-Rodríguez, L.; García-Vita, M.D.M.; Dona-Toledo, L. ICT, disability, and motivation: Validation of a measurement scale and consequence model for inclusive digital knowledge. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colomo-Magaña, E.; Colomo-Magaña, A.; Basgall, L.; Cívico-Ariza, A. Pre-service teachers’ perceptions of the role of ICT in attending to students with functional diversity. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 9379–9395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, V.G.; Suelves, D.M.; Méndez, C.G.; Mas, J.A.R.L. Future teachers facing the use of technology for inclusion: A view from the digital competence. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 9305–9323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreuer, N.; Keter, A.; Sachs, D. Accessibility to information and communications technology for the social participation of youths with disabilities: A two-way street. Behav. Sci. Law 2014, 32, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaksson, C.; Björquist, E. Enhanced participation or just another activity? The social shaping of iPad use for youths with intellectual disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2021, 25, 619–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlott, T.; Aplin, T.; Catchpole, E.; Kranz, R.; Le Goullon, D.; Toivanen, A.; Hutchens, S. Connectedness and ICT: Opening the door to possibilities for people with intellectual disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2020, 24, 503–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreon, A.; Mosher, M.; Goldman, S.; Smith, S.; Smith, B. A Ten-Year Review of the Journal of Special Education Technology: Innovations and Trends for Individuals with Disabilities. J. Spec. Educ. Technol. 2025, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, L.; Vela, E.; Martín, L.; Rodríguez, C. Digital competence in the attention of students with special educational needs. An overview from the European framework for digital teaching competence “DigCompEdu”. Digit. Educ. Rev. 2022, 41, 284–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavié, A.H.; Fernández, A.I.L. New social intervention technologies as a challenge in social work: IFSW Europe perspective. Eur. J. Soc. Work 2018, 21, 824–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinquin, P.A.; Guitton, P.; Sauzéon, H. Online e-learning and cognitive disabilities: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. 2019, 130, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pérez, A.; Lezcano-Barbero, F.; Zabaleta-González, R.; Casado-Muñoz, R. Usage of ICT among Social Educators—An Analysis of Current Practice in Spain. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Dalmeda, M.E.; Chhabra, G. Theoretical models of disability: Tracing the historical development of disability concept in last five decades. Rev. Esp. Discapac. 2019, 7, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, M. Definition and assessment of disability in mental disorders under the perspective of the international classification of functioning disability and health (ICF). Behav. Sci. Law 2017, 35, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranieri, J.M.; Neil, N.; Sadowski, M.; Azzam, M. Supporting Inclusion in Informal Education Settings for Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Scoping Review. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2024, 36, 955–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, E.; van Der Heijden, I.; Dunkle, K. How people with disabilities experience programs to prevent intimate partner violence across four countries. Eval. Program Plann. 2020, 79, 101770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krämer, S.; Zimmermann, F. Teachers’ perceptions of students with different disabilities through the lens of the stereotype content model. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2025, 28, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y. Does information and communication technology (ICT) empower teacher innovativeness: A multilevel, multisite analysis. ETR&D-Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2021, 69, 3009–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santás García, J.I. Proyecto de apropiación de las TIC en servicios sociales de atención social primaria del Ayuntamiento de Madrid. Cuad. Trab. Soc. 2016, 29, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranmer, S. Disabled children’s evolving digital use practices to support formal learning. A missed opportunity for inclusion. Brit. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 51, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabero Almenara, J.; Valencia Ortiz, R. TIC para la inclusión: Una mirada desde Latinoamérica. Aula Abierta 2019, 48, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayor, A.A.; Brereton, M.; Sitbon, L.; Ploderer, B. ICT use and competencies of school children with intellectual disabilities in low-resource settings: The case of Ghana in sub-Saharan Africa. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2025, 24, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla, D.; Suso-Ribera, C.; Zaragoza, I.; Garcia-Palacios, A.; Botella, C. Designing ICTs for users with mild cognitive impairment: A usability study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vélez-Coto, M.; Rodríguez-Fórtiz, M.J.; Rodriguez-Almendros, M.L.; Cabrera-Cuevas, M.; Rodríguez-Domínguez, C.; Ruiz-López, T.; Burgos-Pulido, Á.; Garrido-Jiménez, I.; Martos-Pérez, J. SIGUEME: Technology-based intervention for low-functioning autism to train skills to work with visual signifiers and concepts. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 64, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, S.I.M.; de Andrade, A.M.V. ICT in Portuguese reference schools for the education of blind and partially sighted students. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2016, 21, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martín, J.; García-Sánchez, J.N. Pre-service teachers’ perceptions of the competence dimensions of digital literacy and of psychological and educational measures. Comput. Educ. 2017, 107, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pérez, A.; Lezcano-Barbero, F.; Casado-Muñoz, R.; Zabaleta-González, R. ICT training in Spanish non-formal education: A revolution in the making. Eur. J. Soc. Work 2024, 27, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Rodríguez, A.; Llorente-Cejudo, C.; Lucas, M.; Bem-haja, P. Macroassessment of teachers’ digital competence. DigCompEdu study in Spain and Portugal. RIED-Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Distancia 2025, 28, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F.; Macadar, M.A.; Pereira, G.V. The potential of eParticipation in enlarging individual capabilities: A conceptual framework. Inform. Technol. Dev. 2023, 29, 276–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, C.S.; Tahir, L.M.; Rosli, M.S.; Atan, N.A.; Ali, M.F. Challenges and barriers to e-leadership participation: Examining the perspectives of Malaysian secondary school teachers. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 10329–10367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersh, M. Classification framework for ICT-based learning technologies for disabled people. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2017, 48, 768–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brainin, E.; Shamir, A.; Eden, S. Promoting Spatial language and ability among SLD Children: Can robot programming make a difference? J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2022, 60, 1742–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björquist, E.; Tryggvason, N. When you are not here, I cannot do what I want on the tablet—The use of ICT to promote social participation of young people with intellectual disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2022, 27, 466–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.; Schmidt, C.; Glaser, N.; Beck, D.; Lim, M.; Palmer, H. Evaluation of a spherical video-based virtual reality intervention designed to teach adaptive skills for adults with autism: A preliminary report. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2021, 29, 345–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Chung, Y.J. A case study of group art therapy using digital media for adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1172079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matallana, J.F.V.; Paredes-Velasco, M. Teaching methodology for people with intellectual disabilities: A case study in learning ballet with mobile devices. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2025, 24, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, J. Evaluating performance on a bespoke maths game with children with Down syndrome. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2022, 38, 1394–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, M.; Akkan, Y.; Büyüksevindik, B.; Kaplan, A. Additional operation learning process to the mild intellectual disabilities students by means of virtual manipulatives: A multiple case study. Egit. Bilim 2016, 41, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A. EdQuest: An Iterative Approach to Creating AI-driven Learning and Therapeutic Interventions for Students with Autism. In Proceedings of EdMedia + Innovate Learning, Barcelona, Spain, 19–23 May 2025; Bastiaens, T., Ed.; Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE): Waynesville, NC, USA, 2025; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Alsolami, A.S. The effectiveness of using artificial intelligence in improving academic skills of school-aged students with mild intellectual disabilities in Saudi Arabia. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2025, 156, 104884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awasthy, R. Nature of qualitative research. In Methodological Issues in Management Research: Advances, Challenges, and the Way Ahead; Subudhi, R.N., Mishra, S., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2019; pp. 145–161. [Google Scholar]

- Disability Services and Inclusion Act 2023. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/C2023A00107/latest/text (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Estratégia Nacional para a Inclusão das Pessoas com Deficiência 2021–2025. Available online: https://files.diariodarepublica.pt/1s/2021/08/16900/0000300071.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Ley 6/2022, de 31 de Marzo, de Modificación del Texto Refundido de la Ley General de Derechos de las Personas con Discapacidad y de su Inclusión Social, Aprobado por el Real Decreto Legislativo 1/2013, de 29 de Noviembre, para Establecer y Regular la Accesibilidad Cognitiva y sus Condiciones de Exigencia y Aplicación. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/2022/03/31/6 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Ley Orgánica 3/2020, de 29 de Diciembre, por la que se Modifica la Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de Mayo, de Educación. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2020-17264 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Ojeda-Castelo, J.J.; Piedra-Fernandez, J.A.; Iribarne, L. A device-interaction model for users with special needs. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 6675–6710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Deng, G. Technology and scaling up: Evidence from an NGO for adolescents with intellectual disabilities in China. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 119, 105485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.H.; Chen, K.L.; Shieh, J.Y.; Lu, L.; Huang, C.Y. The determinants of daily function in children with cerebral palsy. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2011, 32, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reguant, M.; Martínez-Olmo, F.; Contreras-Higuera, W. Supervisors’ perceptions of research competencies in the final-year project. Educ. Res. 2018, 60, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirša, A.; Rokić, L.; Vdović, H.; Vertlberg, L.; Žilak, M.; Car, Ž.; Podobnik, V. Analysis of ICT-based assistive solutions for people with disabilities. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Telecommunications (ConTEL), Zagreb, Croatia, 28–30 June 2017; pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fife, S.T.; Gossner, J.D. Deductive qualitative analysis: Evaluating, expanding, and refining theory. Int. J. Qual. Meth. 2024, 23, 16094069241244856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proudfoot, K. Inductive/deductive hybrid thematic analysis in mixed methods research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2023, 17, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, A.; Norris, A.C.; Farris, A.J.; Babbage, D.R. Quantifying thematic saturation in qualitative data analysis. Field Methods 2018, 30, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M.B.; Charen, K.; Shubeck, L.; McConkie-Rosell, A.; Ali, N.; Bellcross, C.; Sherman, S.L. Men with an FMR1 premutation and their health education needs. J. Genet. Couns. 2021, 30, 1156–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yngve, M.; Lidström, H. Implementation of information and communication technology to facilitate participation in high school occupations for students with neurodevelopmental disorders. Disabil. Rehabil.-Assist. Technol. 2024, 19, 2017–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricoy, M.C.; Sánchez-Martínez, C. Raising ecological awareness and digital literacy in primary school children through gamification. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltiyeva, A.; Oliveira, W.; Alimanova, M.; Hamari, J.; Gulzhan Kansarovna, K.; Adilkhan, S.; Urmanov, M. Understanding experiences and interactions of children with asperger’s syndrome in virtual reality-based learning systems. Interact. Learn. Envir. 2025, 33, 1118–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovska, I.V.; Trajkovski, V. Effects of a computer-based intervention on emotion understanding in children with autism spectrum conditions. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 4244–4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lussier-Desrochers, D.; Normand, C.L.; Romero-Torres, A.; Lachapelle, Y.; Godin-Tremblay, V.; Dupont, M.È.; Roux, J.; Pépin-Beauchesne, L.; Bilodeau, P. Bridging the digital divide for people with intellectual disability. Cyberpsychology 2017, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paños-Castro, J.; Bilbao, E.; Arruti, A.; Carballedo, R. Autopercepción de la competencia digital del alumnado del grado en Educación Social con Ikanos. Campus Virtuales 2022, 11, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almerich, G.; Suárez-Rodríguez, J.; Díaz-García, I.; Orellana, N. Structure of 21st century competences in students in the sphere of education. Influential personal factors. Educ. XX1 2020, 23, 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Zhao, L.; Cao, E.Y. Revisiting factors influencing strategies for enhancing pre-service teachers’ digital competencies. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorghiu, G.; Sherborne, T.; Kowalski, R.; Vives-Adrián, L.; Ribeiro, S. Enhancing Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Supported by Coaching in the Content of Open Schooling for Sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Montes, C.d.P.; Caurcel Cara, M.J.; Rodríguez Fuentes, A.; Capperucci, D. Opinions, training and requirements regarding ICT of educators in Florence and Granada for students with functional diversity. Univ. Access Inf. Soc. 2024, 23, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenney, S.; Schunn, C.D. How can educational research support practice at scale? Attending to educational designer needs. Brit. Educ. Res. J. 2018, 44, 1084–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovan, M.; Perdih, M. Developing guidelines for evaluating the adaptation of accessible web-based learning materials. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2016, 17, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekin, C.Ç.; Çağiltay, K.; Karasu, N. Usability study of a smart toy on students with intellectual disabilities. J. Syst. Architect. 2018, 89, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunan, A.; Mudjiyanto, B.; Walujo, D. Unveiling Disability Empowerment: Evaluating ICT Skill Enhancement Initiatives in Indonesia. Media Commun. 2025, 13, 9078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wu, D. ICT-based assistive technology as the extension of human eyes: Technological empowerment and social inclusion of visually impaired people in China. Asian J. Commun. 2021, 31, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, G.F.; van Wingerden, E.; Sterkenburg, P.S. The effectiveness of the use of a technology toolkit on activities and mother-child interactions: Children with complex care needs. Disabil. Rehabil.-Assist. Technol. 2024, 19, 2545–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolaki, A.; Economides, A.A. The Creativity Challenge Game: An educational intervention for creativity enhancement with the integration of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs). Comput. Educ. 2018, 123, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drisko, J.W. Transferability and generalization in qualitative research. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2025, 35, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).