The Evolution of the “Three Dots of the Character Yi” in Mahāyāna Buddhism: With a Focus on Fang Yizhi’s “Perfect ∴” Theory

Abstract

1. Introduction

or

or  , later simplified into three dots distributed in a triangular pattern, “∴,” and was also transliterated as characters yi 伊/依/以 in Chinese scriptures.3 However, the precise and profound implications of the Buddhist “three dots of the character Yi” or the symbol ∴, which were integrated into Fang Yizhi’s Perfect ∴ theory, continue to elude clear understanding.

, later simplified into three dots distributed in a triangular pattern, “∴,” and was also transliterated as characters yi 伊/依/以 in Chinese scriptures.3 However, the precise and profound implications of the Buddhist “three dots of the character Yi” or the symbol ∴, which were integrated into Fang Yizhi’s Perfect ∴ theory, continue to elude clear understanding.2. The “Three Virtues of Nirvāṇa” as Described in the Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra

“Bhikṣus! Just as the earth, mountains, and medicinal herbs benefit sentient beings, so does my Dharma. It provides the wonderful nectar of the Dharma and serves as the excellent medicine for the afflictions and diseases of sentient beings. Today, I will enable all sentient beings and my fourfold assembly of disciples to dwell securely in the secret repository. I will also dwell therein and enter Nirvāṇa. What is called the secret repository? It resembles the three dots of the character Yi (伊字三點). If [the three dots] are horizontally arranged, they do not form Yi; nor does their vertical arrangement result in the formation of Yi. Similarly to the three eyes on the face of Mahêśvara5, it is capable of forming the Yi character. If the three points are separated, it cannot be accomplished either. I am also like this. The dharma of liberation is not Nirvāṇa, the body of the Tathāgata is not Nirvāṇa, the Great Wisdom (mahāprajñā) is also not Nirvāṇa, and the three dharmas, being distinct from one another, also do not equate to Nirvāṇa. I now abide in these three dharmas and for the sake of sentient beings, [I] call it ‘entering Nirvāṇa’, like the Yi character in the world.”

「諸比丘!譬如大地、諸山、藥草為眾生用,我法亦爾。出生妙善甘露法味,而為眾生種種煩惱病之良藥。我今當令一切眾生,及以我子四部之眾,悉皆安住祕密藏中,我亦復當安住是中,入於涅槃。何等名為祕密之藏?猶如伊字三點,若並則不成伊,縱亦不成;如摩醯首羅面上三目,乃得成伊。三點若別,亦不得成,我亦如是。解脫之法亦非涅槃,如來之身亦非涅槃,摩訶般若亦非涅槃,三法各異亦非涅槃。我今安住如是三法,為眾生故,名入涅槃,如世伊字。」6

3. The Perfect Interfusion of the “Triadic Dharmas” in Tiantai Buddhism

If one believes that the three virtues are neither vertical nor horizontal, neither conflated nor distinct—like the three dots or the three eyes—then one should also believe that the threefold cessation and threefold contemplation are likewise neither vertical nor horizontal, neither together nor separate. However, the scriptures, adapting to the capacities [of sentient beings], often one-sidedly emphasize one method to illustrate a particular doctrinal point. […] Just as cessation and contemplation encompass the three virtues in this manner, they similarly permeate all other [triadic] names—such as “staying away from conceptual knowledge”—and so on. Moreover, they extend to all triadic names, the so-called threefold enlightenment, the three Buddha-natures, the three treasures, and indeed all triadic dharmas in the same way.

若信三德不縱不橫、不並不別,如三點、三目者,亦信三止三觀不縱不橫,不並不別也。而諸經赴緣,偏舉一法,以示義端。……止觀通三德既爾,通諸異名,遠離知見等,亦如是。又通諸三名,所謂三菩提、三佛性、三寶等,一切三法,亦如是。12

4. The Huayan School’s Integration of “The Three Chan Lineages” and “The Three Doctrinal Teachings”

Thus, followers of the Sudden and Gradual approaches regard each other like sworn enemies; those within the Southern and Northern schools oppose each other like [the rival states of] Chu and Han. The admonition of [the Buddha] washing his feet [after being insulted by a Brahmin], and the parable of the blind men touching the elephant, are precisely validated by this situation. Now, the purpose of my writing is certainly not to create yet another separate collection, but rather to synthesize them. The essential task lies in [achieving the harmony of] the three dots of the character Yi. Just as the three dots, if kept separate, can no longer form the Yi-character, so too if the three lineages [of Chan] remain in conflict, how can one accomplish Buddhahood?

故頓漸門下相見如仇讎,南北宗中相敵如楚漢。洗足之誨,摸象之喻,驗於此矣。今之所述,豈欲別為一本?集而會之,務在伊圓三點。三點各別既不成伊,三宗若乖焉能作佛?18

5. The Early Caodong School: “The Three Dots of the Perfect Yi Distinguish Host and Guest”

The Precious Mirror responds freely, beyond secret transmission;

The slightest leakage [into conceptualization] falls into verbal explanation.

The three dots of the perfect Yi distinguish host and guest;

Subtly embracing dual illumination, it transcends correctness and deviation.

寶鏡當機不密傳,

纖毫滲漏墮言詮。

圓伊三點分賓主,

妙挾雙明絕正偏。20

Beware! Seek not from others,

Lest it distantly drift apart from me.

Now I journey alone,

Yet everywhere I encounter it.

It now is precisely me,

Yet I now am not it.

One must comprehend in this manner,

To finally accord with Suchness.

切忌從他覓,迢迢與我疎。

我今獨自往,處處得逢渠。

渠今正是我,我今不是渠。

應須恁麼會,方得契如如。21

6. Fang Yizhi’s Reform of the Three Dots of the Character Yi

6.1. The Central Five

6.2. The Great Ultimate—Two Modes

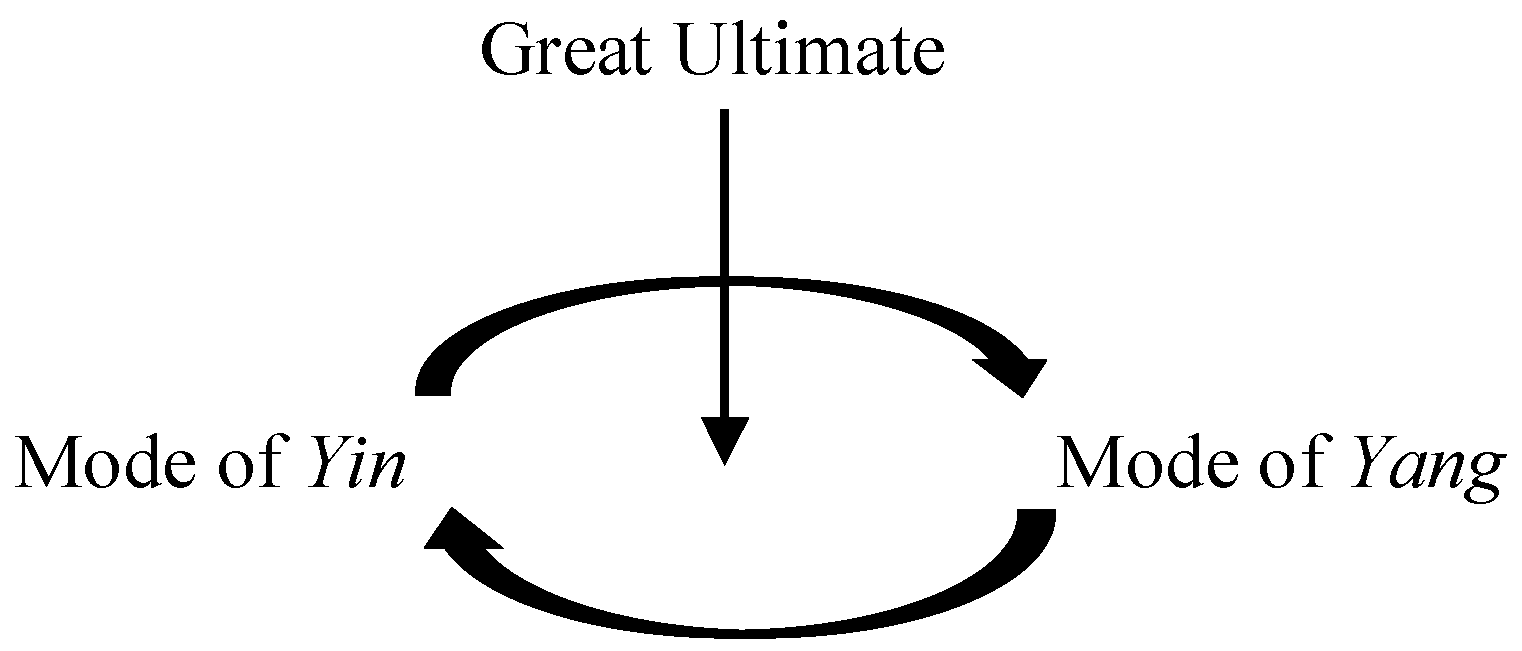

The three dots of the Perfect ∴ exemplify the principle of presenting one to illuminate three, which signifies employing the mean between two extremes and permeating all with a single unifying principle. Essentially, all phenomena arise from the duality of odd and even numbers, wherein the odd and the even constitute the foundation of the triadic and dyadic relationships. The upper dot represents the Great Ultimate, which transcends all dualities and eludes the four propositions of logical assertion. The lower two dots represent the Two Modes, which exist in mutual opposition and interact through alternating rotation within the Great Ultimate. […] The symbol is conceived in this way, with the upper dot actually penetrating the two lower dots like a circle, neither vertical nor horizontal, yet capable of being both vertical and horizontal.

圓∴三點,舉一明三,即是兩端用中,一以貫之。蓋千萬不出於奇偶之二者,而奇一偶二即參兩之原也。上一點為無對待、不落四句之太極,下二點為相對待、交輪太極之兩儀。……設象如此,而上一點實貫二者如環,非縱非橫而可縱可橫。32

6.3. The Three Ultimates and the Three Heavens

The hexagrams and lines of the acquired realm are already fully manifested—this is called the Ultimate of Being. The hexagrams and lines of the innate realm have not yet been fully expressed—this is called the Ultimate of Non-being. These two Ultimates stand in opposition, while the absolute Great Ultimate, transcending opposition, is called the Central Heaven. The Central Heaven exists within both the innate and acquired realms, and the innate realm exists within the acquired realm—thus, the three are one.

後天卦爻已布,是曰有極;先天卦爻未闡,是曰無極。二極相待,而絕待之太極,是曰中天。中天即在先、後天中,而先天即在後天中,則三而一矣。36

7. Conclusions: The Perfect ∴ as the Conceptual Foundation for the Interconnectedness of the Three Teachings

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | For a comprehensive study of Fang Yizhi’s life and work, see (Yu 1972) and (Peterson 1979). |

| 2 | For instance, Zhou (2005, p. 94), who has long been dedicated to the research of Fang Yizhi’s philosophical thoughts, holds that “Perfect ∴ theory is an important aspect for understanding Fang Yizhi’s philosophical thoughts.” Liao (2016, p. 30) highlighted from the perspective of philosophy of the Book of Changes that “the Perfect ∴ pattern constitutes a pivotal concept in Fang Yizhi’s study of the Book of Changes and his entire intellectual system.” Jiang (2023, p. 49), a leading expert at the Fang Yizhi Research Center of Anhui University 安徽大學方以智研究中心, stated in a recent article that the “Perfect ∴ three dots” model elucidates the relationship between ‘common cause’ (gongyin 公因) and ‘opposite cause’ (fanyin 反因). Consequently, the “Perfect ∴” is considered “the foundational framework of Fang Yizhi’s philosophical thought, playing a crucial role in understanding the essence and features of Fang Yizhi’s philosophy.” Furthermore, Liu (2023, p. 148) posited that, “In Fang’s philosophy, the Perfect ∴ glyph and the theory of ti-yong 體用 (substance and function) it symbolizes occupy a central theoretical position.” (The English translations of the passages from the Chinese secondary literature are provided by the authors of this paper.) |

| 3 | The Middle Chinese pronunciation of the characters 伊/依/以 would have been closer to the Sanskrit akṣara “i.” For the sake of clarity and consistency in this paper, the term “伊字” found in the cited texts is uniformly translated as “character Yi” using Modern Mandarin Pinyin. However, it should be noted that the pronunciation of the character “伊” in Middle Chinese may have differed from its pronunciation in Modern Chinese. |

| 4 | Pang Pu 龐樸, the annotator of Fang Yizhi’s Dongxi jun 東西均, was one of the earlier modern scholars to propose this theory and his views have been widely acknowledged by Chinese academics. In other Buddhist scriptures introduced to China during the early period, there were also expressions similar to the “three dots of the character Yi”. For example, in the Chapter of Observing the Characteristics (Guanxiang pin 觀相品), from the Sūtra on the Ocean-Like Samādhi of the Visualization of the Buddha (Foshuo Guanfo sanmeihai jing 佛說觀佛三昧海經) translated in the Eastern Jin Dynasty, it is recorded that the Tathāgata “had distinct dot-like marks on the throat, resembling the Yi-character.” (咽喉上有點相分明,猶如伊字。; CBETA 2025.R1, T15, no. 643, p. 659b9-10.) This account differs slightly from the one in the Mahāparinirvāṇa sūtra. There is no doubt, however, that the Yi-character schema embedded within the “Three Virtues of Nirvāṇa” in the Mahāparinirvāṇa sūtra exerted the most significant influence on Chinese Buddhist tradition. |

| 5 | Mahêśvara is the god in Hindu mythology who creates and controls the world—also known as Śiva or as Īśvaradeva, king of the devas. Mahêśvara is represented with three eyes and eight arms, and riding on a white bull. Notably, the three eyes are arranged not horizontally nor vertically, but in a triangular configuration. |

| 6 | CBETA 2025. R2, T12, no. 374, p. 376c6-17. Translation by the authors. |

| 7 | The original scripture referred to the concept as the “Three Dharmas” (sanfa 三法), meaning the Buddha’s Three Teachings on Nirvāṇa or the three truths concerning Nirvāṇa in Buddhism. No later than the period following Zhiyi 智顗 of the Sui Dynasty, Buddhist scholars increasingly adopted the term “Three Virtues” (sande 三德) to denote these “Three Dharmas”, naming them the “Three Virtues of Nirvāṇa” (sande niepan 三德涅槃). The latter part of this text will examine how Zhiyi employed this terminology. Modern scholars of Chinese Buddhist thought also habitually use “Three Virtues” rather than “Three Dharmas” to summarize this passage of the scripture. This preference may stem from the perspective that, from the standpoint of the Buddha’s teachings, liberation, Dharma-body, and wisdom belong to the category of “dharmas” (fa 法); in contrast, from the perspective of Buddhists, these three are “qualities” cultivated through practical cultivation and internalized within the practitioner, hence the later prevalent use of “virtues” (de 德). Some modern scholars, based on the account found in the sixth chapter of the Mahāparinirvāṇa sūtra, also refer to the “Three Virtues” as the “Four Virtues”, as seen in Fang (2012, p. 123). |

| 8 | The study of Nirvāṇa reached its zenith during the approximately one hundred years from the late 5th century to the early 6th century. The school centered on the interpretation of the Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra was known as the “Nirvāṇa School” (niepan zong 涅槃宗). It is important to note that this “school” differed from the continuous lineage-based Buddhist sects that emerged later during the Sui Dynasty (581–618), as well as from the exclusive and organizational denominations seen in Japanese Buddhism. The Nirvāṇa School was scholarly in nature rather than organizational, and monks who engaged in the philosophical interpretation of the Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra were referred to as “Nirvāṇa masters” (niepan shi 涅槃師). Among the concepts explored in Nirvāṇa studies, “Buddha-nature” (foxing 佛性) and “Tathāgatagarbha” (rulaizang 如來藏) have had the most profound impact on later periods. See W. Zhang (2024, pp. 3–9). |

| 9 | “面上三目者,般若居上,身及解脫,二無勝故,並列在下。” CBETA 2025.R2, T37, no. 1763, p. 401c22-24. |

| 10 | “寶亮曰:竝者,以一時俱有以為譬也。何者?昔以事斷無為為涅槃,而此無為與身智竝故,非今日伊字也。縱者,以前後為目,亦譬昔日無餘涅槃也,謂先有身、次有智、後有滅,故言非也。” CBETA 2025.R2, T37, no. 1763, p. 402a9-13. |

| 11 | Three commentaries on the Lotus Sūtra (Fahua jing 法華經) deemed most important by Tiantai. They are the Fahua xuanyi 法華玄義 (Profound Meaning of the Lotus Sūtra), the Fahua wenju 法華文句 (Textual Commentary on the Lotus Sūtra), and the Mohe zhiguan 摩訶止觀 (Great Cessation and Contemplation). All three were written by Zhiyi as commentaries on the Kumārajīva translation of the Lotus Sūtra. |

| 12 | CBETA 2025.R2, T46, no. 1911, p. 23a19-b1. |

| 13 | “三種解脫、三道、三識、三佛性、三般若、三種菩提、三大乘、三佛、三涅槃、三寶,亦復如是,皆不縱不橫,如世「伊」字。” CBETA 2025.R2, T38, no. 1777, p. 553c27-29. |

| 14 | CBETA 2025.R2, X20, no. 356, p. 27c2-3 // R30, p. 786a11-12 // Z 1:30, p. 393c11-12. |

| 15 | “謂以三點喻於三乘,以成一伊喻為一乘。別說三乘三皆是權,合三為一故得稱實,非三點外更有一點。” CBETA 2025.R2, T36, no. 1736, p. 47a28-b2. |

| 16 | “不得定一二上下,但取不可縱橫及並別耳。” CBETA 2025.R2, T36, no. 1736, p. 632a7-8. |

| 17 | |

| 18 | CBETA 2025.R2, T48, no. 2015, p. 402b2-7. |

| 19 | |

| 20 | CBETA 2025.R2, J23, no. B135, p. 628c22-25; It is noteworthy that within this poem, the “three dots of the character Yi” (yizi sandian 伊字三點) have already begun to be referred to as the “three dots of the perfect Yi” (yuanyi sandian 圓伊三點). This likely signifies that, due to the advocacy of the Tiantai and Huayan schools, the relationship of “perfect interfusion” (yuanrong 圓融) symbolized by the “∴” glyph had become common knowledge within Buddhism. Consequently, this paper argues that the character “圓” in the term “圓伊” and “圓∴” should be understood as an abbreviation for “perfect interfusion”. |

| 21 | CBETA 2025.R2, T47, no. 1986B, p. 520a20-23. |

| 22 | “兼帶者,冥應眾緣,不隨諸有。非染非淨,非正非偏。故曰虛玄大道,無著真宗。” CBETA 2025.R2, T48, no. 2006, p. 313c19-21. |

| 23 | “重離六爻,偏正回互。疊而為三,變盡成五。” CBETA 2025.R2, T47, no. 1986B, p. 526a4-5. |

| 24 | “兼中到者,重離也,正不必虛,偏不必實,無背無向。” CBETA 2025.R2, T47, no. 1987A, p. 533b23-24. |

| 25 | Regarding the detailed analysis of how the two founders of the Caodong school incorporated the Zhouyi, i.e., the Book of Changes, to expound Chan Buddhism, two significant academic articles are noteworthy. One is by a Mainland Chinese scholar, Chen (2015), and the other is by a Taiwanese scholar, Cai (2013), who is also an expert in the studies of Fang Yizhi. |

| 26 | |

| 27 | |

| 28 | Zhouyi shilun hebian jiaozhu, p. 51. |

| 29 | “中五用三,藏一旋四,此「易」之准也。” Zhouyi shilun hebian jiaozhu, p. 27. |

| 30 | Zhouyi shilun hebian jiaozhu, p. 27. |

| 31 | Dongxi jun zhushi, p. 36. |

| 32 | Dongxi jun zhushi, p. 103. |

| 33 | “虛實也,動靜也,陰陽也,形氣也,道器也,晝夜也,幽明也,生死也,盡天地古今皆二也。” Dongxi jun zhushi, p. 67. |

| 34 | “無對待在對待中,然不可不親見此無對待者也。” Dongxi jun zhushi, p. 143. |

| 35 | “太極之前添無極,則不能顯不落有無之太極矣。故愚從而三之。” Dongxi jun zhushi, p. 81. |

| 36 | Dongxi jun zhushi, p. 78. |

| 37 | “禪者見諸儒汩沒世情之中,以為不礙,而禪遂為撥因果之禪。儒者借禪宗一切圓融之見,以為發前賢所未發,而儒遂為無忌憚之儒。” Yaodi paozhuang jiaozhu, p. 164. |

| 38 | Both the Tiantai and Huayan traditions developed profound conceptions of “perfect interfusion” (yuanrong 圓融). In Tiantai, the notion of yuanrong is centered on the “the perfect interfusion of the threefold truth”, as discussed earlier. Fang Yizhi’s understanding of yuanrong, however, aligns more closely with that of the Huayan school. In Huayan discourse, “perfect interfusion” is often discussed in correlation with “sequential deployment” (xingbu 行布), a pairing that can be traced to Chengguan’s interpretation of the Flower Ornament Sūtra. As Chengguan stated: “Perfect interfusion does not obstruct sequential deployment, thus the One becomes the innumerable; Sequential deployment does not obstruct perfect interfusion, thus the innumerable become the One. The innumerable becoming the One implies harmonious permeation and implicit containment; The One becoming the innumerable implies mutual entry and layers of interpenetration.” (圓融不礙行布,故一為無量;行布不礙圓融,故無量為一。無量為一,故融通隱隱;一為無量,故涉入重重。CBETA 2025.R2, T35, no. 1735, p. 504b25-27.) Here, xingbu emphasizes the distinctions, independence, and sequential order among elements within a holistic system, while yuanrong underscores how each element is embedded within the whole—enabling mutual penetration among all elements, with any single element capable of revealing the whole. |

| 39 | “人多不知圓∴之用代錯,所以不知無可無不可兼帶之妙。” Dongxi jun zhushi, p. 489. |

| 40 | “合看圓∴之舉一明三,即知兩端用中之一以貫之。” Dongxi jun zhushi, p. 435. |

| 41 | “老子曰:‘反者道之動。’非止訓複也。……當下知反因即正因矣。” Dongxi jun zhushi, p. 139. |

| 42 | Dongxi jun zhushi, p. 428. |

| 43 | Included in the Tianjie Juedang Daosheng chanshi yulu, CBETA 2025.R2, J34, no. B311, pp. 768b01-776a30. |

| 44 | According to this theory, Zhuangzi was in fact the true heir of Confucius, who was compelled by circumstance to “entrust his orphaned legacy” (tuogu 托孤) to the Laozi school. Yang Rubin’s monograph (Yang 2020) represents a further development of the “Zhuangzi emerged from the Confucian school” theory advanced by the master–disciple lineage of Daosheng and Fang Yizhi. |

| 45 | Edward T. Chien once categorized the Chinese tradition of synthesizing the Three Teachings into two types: “compartmentalization” and “non-compartmentalization”. Fang Yizhi’s approach belongs to neither; it can be described as using a “non-compartmentalization” mode (emphasizing the interconnectedness of the Three Teachings) to encompass “compartmentalization” (acknowledging their distinct identities). See Chien (1986, p. 15). |

References

Primary Sources

Fang, Yizhi 方以智. 2016. Dongxi jun zhushi 東西均注釋 [Annotations on the Balance of East and West]. Annotated by Pang Pu 龐樸. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju.Fang, Kongzhao 方孔炤, Yizhi Fang 方以智. 2021. Zhouyi shilun hebian jiaozhu 周易時論合編校注 [Annotations on the Comprehensive Compilation on the Zhouyi’s Temporal Theories]. Annotated by Cai Zhenfeng 蔡振豐 etc. Taipei: Xinwenfeng Chuban Gongsi.Fang, Yizhi 方以智. 2017. Yaodi pao Zhuang jiaozhu 藥地炮莊校注 [Annotations on The Medicinal Herbs Master’s Stewing of the Zhuangzi]. Annotated by Cai Zhenfeng 蔡振豐 etc. Taipei: Guoli Taiwan Daxue Chuban Zhongxin.CBETA (Chinese Buddhist Electronic Text Association). Available online: https://www.cbeta.org/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).Chengguan 澄觀. Dafangguang fo Huayan jing shu 大方廣佛華嚴經疏. Available online: https://cbetaonline.cn/zh/T1735 (accessed on 5 September 2025).Chengguan 澄觀. Dafangguang fo Huayan jing suishu yanyichao 大方廣佛華嚴經隨疏演義鈔. Available online: https://cbetaonline.cn/zh/T1736 (accessed on 5 September 2025).Daban niepan jing 大般涅槃經. Available online: https://cbetaonline.cn/zh/T0374 (accessed on 5 September 2025).Dehong 德洪. Shimen wenzi Chan 石門文字禪. Available online: https://cbetaonline.cn/zh/JB135 (accessed on 5 September 2025).Foshuo Guanfo sanmeihai jing 佛說觀佛三昧海經. Available online: https://cbetaonline.cn/zh/T15n0643 (accessed on 5 September 2025).Ruizhou Dongshan Liangjie chanshi yulu 瑞州洞山良價禪師語錄. Available online: https://cbetaonline.cn/zh/T1986B (accessed on 5 September 2025).Rentian yanmu 人天眼目. Available online: https://cbetaonline.cn/zh/T2006 (accessed on 5 September 2025).Tianjie Juedang Daosheng chanshi yulu 天界覺浪道盛禪師語錄. Available online: https://cbetaonline.cn/zh/J34nB311 (accessed on 26 October 2025).Wuzhou Caoshan Yuanzheng chanshi yulu 撫州曹山元證禪師語錄. Available online: https://cbetaonline.cn/zh/T1987A (accessed on 5 September 2025).Zongmi 宗密. Chanyuan zhuquanji duxu 禪源諸詮集都序. Available online: https://cbetaonline.cn/zh/T2015 (accessed on 5 September 2025).Zhiyi 智顗. Mohe zhiguan 摩訶止觀. Available online: https://cbetaonline.cn/zh/T1911 (accessed on 5 September 2025).Zhiyi 智顗. Weimojing xuanshu 維摩經玄疏. Available online: https://cbetaonline.cn/zh/T1777 (accessed on 5 September 2025).Zhiyi 智顗. Jinguangmingjing xuanyi shiyiji huiben 金光明經玄義拾遺記會本. Available online: https://cbetaonline.cn/zh/X0356 (accessed on 5 September 2025).Secondary Sources

- Araki, Kengo 荒木見悟. 2000. Yukoku Rekka Zen: Zenso Kakuro Dosei No Tatakai 憂國烈火禪—禪僧覺浪道盛のたたかい [Chan in the Fierce Flames of a Nation in Distress—The Struggle of the Monk Juelang Daosheng]. Tokyo: Kenbun shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Zhenfeng 蔡振豐. 2013. Caodong Zongzhi yu Yunyan Tansheng Baojing Sanmei Ge Zhong de Shiliu Zi Ji 曹洞宗旨與雲岩曇晟<寶鏡三昧歌>中的十六字偈 [The Caodong Principle and the Sixteen-Character Verse in Yunyan Tansheng’s Song of the Precious Mirror Samadhi]. Paper presented at the 7th Cross-Strait Academic Conference on the Zhouyi, Jinan, China, July 14–24; pp. 826–35. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Jian 陳堅. 2015. Chongli Liuyao, Pianzheng Huihu—Caodong Zong Chanxue de Yixue Jichu 重離六爻,偏正回互—曹洞宗禪學的易學基礎 [Six Lines of Chong Li, Interplay of Correctness and Deviation—Study of Zhouyi as the Foundation for Caodong Buddhism]. Zhouyi Yanjiu 1: 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, Edward T. 1986. Chiao Hung and the Restructuring of Neo-Confucianism in the Late Ming. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Litian 方立天. 2012. Zhongguo Fojiao Zhexue Yaoyi 中國佛教哲學要義 [Essentials of Chinese Buddhist Philosophy]. Beijing: Zhongguo Renmin Daxue chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, John B. 1994. Chinese Cosmographical Thought: The High Intellectual Tradition. In The History of Cartography, Volume 2, Book 2: Cartography in the Traditional East and Southeast Asian Societies. Edited by John Brian Harley and David Woodward. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 203–227. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Guobao 蔣國保. 2023. Fangyizhi Erxu Yishi shuo de xiandai quanshi 方以智“二虛一實”說的現代詮釋 [A Modern Interpretation of Fang Yizhi’s “Erxu and Yishi” Theory]. Xueshu Jie 12: 39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Qichao 梁啟超. 2015. Zhongguo jin sanbainian xueshu shi 中國近三百年學術史 [Intellectual History of China in the Past Three Hundred Years]. In Yinbing Shi Heji 飲冰室合集. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, vol. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Cancan 廖燦燦. 2016. Yixue zhexue shiye xia de Fangyizhi Yuan ∴ sixiang tanxi 易學哲學視野下的方以智圓∴思想探析 [An Analysis of Fang Yizhi’s Thought on the Perfect∴ from the Perspective of Zhouyi Philosophy]. Zhongguo Zhexue Shi 4: 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Yu 劉瑜. 2023. Fang Yizhi Wulun Yanjiu 方以智物論研究 [A Study of Fang Yizhi’s Theory of Things]. Xinbei: Huamulan Wenhua Shiye Youxian Gongsi. [Google Scholar]

- Mun, Chanju. 2005. The History of Doctrinal Classification in Chinese Buddhism: A Study of the Panjiao System. Lanham: University Press of America. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, Willard J. 1979. Bitter Gourd: Fang I-chih and the Impetus for Intellectual Change. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Rubin 楊儒賓. 2020. Rumen nei de Zhuangzi 儒門內的莊子 [Zhuangzi Within the Confucian School]. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Ying-shih. 1972. Fang Yizhi Wanjie Kao 方以智晚節考 [A Study of Fang Yizhi’s Later Years]. Hongkong: Xinya Yanjiusuo. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Liwen 張立文. 2023. Sanyi quan shu, yifa wubie—Zongmi yi Huayan jing wei jiujing de Huayan Chan panjiao sixiang 三義全殊,一法無別—宗密以華嚴經為究竟的華嚴禪判教思想 [Three Meanings Entirely Distinct, Yet the Dharma Is Without Difference—Zongmi’s Huayan-Chan Doctrinal Classification Regarding the Flower Ornament Sūtra as the Ultimate Teaching]. Chuanshan Journal 6: 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Wenliang 張文良. 2024. Niepanxue Yanjiu 涅槃學研究 [On the Nirvāṇa Study]. Beijing: Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Qinqin 周勤勤. 2005. Fang Yizhi Yuan ∴ shuo jiexi 方以智“圓∴”說解析 [An Analysis on Fang Yizhi “∴ Theory”]. Zhongguo Shehui Kexueyuan Yanjiusheng Yuan Xuebao 5: 94–102. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Anderl, C. The Evolution of the “Three Dots of the Character Yi” in Mahāyāna Buddhism: With a Focus on Fang Yizhi’s “Perfect ∴” Theory. Religions 2025, 16, 1544. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121544

Liu Y, Anderl C. The Evolution of the “Three Dots of the Character Yi” in Mahāyāna Buddhism: With a Focus on Fang Yizhi’s “Perfect ∴” Theory. Religions. 2025; 16(12):1544. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121544

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yu, and Christoph Anderl. 2025. "The Evolution of the “Three Dots of the Character Yi” in Mahāyāna Buddhism: With a Focus on Fang Yizhi’s “Perfect ∴” Theory" Religions 16, no. 12: 1544. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121544

APA StyleLiu, Y., & Anderl, C. (2025). The Evolution of the “Three Dots of the Character Yi” in Mahāyāna Buddhism: With a Focus on Fang Yizhi’s “Perfect ∴” Theory. Religions, 16(12), 1544. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16121544